Abstract

Objective:

To survey amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) health care providers to determine attitudes regarding physician-assisted death (PAD) after the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) invalidated the Criminal Code provisions that prohibit PAD in February 2015.

Methods:

We conducted a Canada-wide survey of physicians and allied health professionals (AHP) involved in the care of patients with ALS on their opinions regarding (1) the SCC ruling, (2) their willingness to participate in PAD, and (3) the PAD implementation process for patients with ALS.

Results:

We received 231 responses from ALS health care providers representing all 15 academic ALS centers in Canada, with an overall response rate for invited participants of 74%. The majority of physicians and AHP agreed with the SCC ruling and believed that patients with moderate and severe stage ALS should have access to PAD; however, most physicians would not provide a lethal prescription or injection to an eligible patient. They preferred the patient obtain a second opinion to confirm eligibility, have a psychiatric assessment, and then be referred to a third party to administer PAD. The majority of respondents felt unprepared for the initiation of this program and favored the development of PAD training modules and guidelines.

Conclusions:

ALS health care providers support the SCC decision and the majority believe PAD should be available to patients with moderate to severe ALS with physical or emotional suffering. However, few clinicians are willing to directly provide PAD and additional training and guidelines are required before implementation in Canada.

Physician-assisted death (PAD) for patients with intolerable suffering and incurable medical conditions is currently available in a growing number of countries and regions of the United States.1,2 PAD includes both physician-assisted suicide, whereby the physician provides a prescription for a lethal medication to be taken by the requesting patient, and voluntary active euthanasia, whereby the physician administers a lethal medication for the sole purpose of ending the life of the requesting patient.3,4

On February 6, 2015, the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) invalidated the Criminal Code provisions that prohibit PAD for a “competent adult person who (1) clearly consents to the termination of life and (2) has a grievous and irremediable medical condition (including an illness, disease, or disability) that causes enduring suffering that is intolerable to the individual in the circumstances of his or her condition.”5 This ruling was suspended until June 2016 to provide the federal government and stakeholders with the opportunity to develop legislation, policies, and protocols for PAD, which will be legalized across all Canadian provinces and territories.6

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), a terminal motor neuron disease resulting in paralysis and respiratory failure, has been at the forefront of the PAD debate and the SCC ruling will affect ALS patient care. In fact, the proportion of patients receiving PAD is higher for ALS as compared to cancer in Oregon (1998–2007) and the Netherlands (1994–1998, 2000–2005, and 2003–2008).7–11

Although PAD will soon be legal in Canada, questions remain regarding eligibility and access that continue to divide the public and medical community.12–14 While most patients with advanced ALS would qualify for PAD according to the SCC criteria, additional insights from ALS health care providers are necessary to inform the implementation of this program. To help gain this perspective, we conducted a cross-Canada survey gauging the attitudes of front-line ALS health care providers on the SCC ruling. This included physicians and allied health professionals (AHP) involved in ALS patient care. Specifically, we sought to determine (1) their understanding of the SCC ruling, (2) the willingness of physicians to actively provide PAD at different stages of ALS disease severity, and (3) the processes required to implement PAD for patients with ALS.

METHODS

Standard protocol approval, registrations, and patient consents.

This study was approved by the Sunnybrook Health Sciences Research Ethics Board (260-2015). Implied consent was obtained from all survey participants.

Study design and participants.

We conducted a cross-sectional, anonymous, online survey via SurveyMonkey platform (www.surveymonkey.com) between October 2, 2015, and December 3, 2015. Physicians and AHP involved in the diagnosis and care of patients with ALS in Canada were invited to participate. Invitations were sent by e-mail with the assistance of the Canadian ALS Research Network, which includes all 15 Canadian academic ALS clinics (table e-1 at Neurology.org). The survey link was distributed by (1) direct invitation with a single-user link when the e-mail address was available or provided; and (2) by a multiple-user, open survey link sent to the ALS clinic leader to be forwarded to team members and to other physicians and AHP who participate in the diagnosis and care of ALS at their site. The second option was chosen by some ALS clinic leaders as they preferred not to distribute e-mail addresses. In addition, an open survey link was disseminated through the Canadian Society of Palliative Care Physicians e-mail list to assess the perspective of palliative care experts working with ALS.

Questionnaire.

We generated questionnaire items from relevant literature and expert opinion to address the 3 research questions previously indicated. Content validity was determined and redundant items were eliminated on the basis of expert consultation, and questions were framed in neutral, nonpejorative language with definitions provided (table e-2). Pilot testing and pretesting were conducted with a small group of ALS clinician experts (neurology, palliative care, physiatry, and respirology) and AHP (nursing, occupation therapy, speech language pathology, and dietician).

All survey participants expressed their opinions via a directed questionnaire with a commentary field where applicable. The only required demographic questions were sex, age group (by decade to maintain anonymity), and participant's duration and role in ALS patient care. All other demographic and survey questions were optional, including geographic location, in order to maintain anonymity given the small number of ALS clinics and experts in Canada.

The respondents indicating that PAD should be conditional and available only to a subgroup of patients with ALS were directed to 3 clinical scenarios describing patients with advancing ALS symptom severity and disabilities. The scenarios describe hypothetical, competent adult patients with ALS who meet SCC eligibility to request PAD. The first scenario (mild stage ALS) describes a patient with isolated mild distal leg weakness. This description is consistent with a revised ALS Functional Rating Scale (ALSFRS-R)15 score of 43–46 (individuals with no functional deficits score 48 on this ordinal scale, with lower scores indicating more severe deficits). The second scenario (moderate stage ALS) describes a patient with weakness in the arms and moderate to severe dysphagia (ALSFRS-R 27–36). The third scenario (severe stage ALS) involves a patient with severe weakness in all limbs and respiratory impairment (ALSFRS-R 5–15). See table e-3 for additional details.

Statistical analysis.

Proportions were calculated for categorical variables. Means and standard deviations were computed for continuous variables. Statistical significance was assessed using a χ2 test or Student t test as appropriate.

We evaluated the correlation of sex, age, duration of ALS care, province, role in ALS care (physician or AHP), depth of religiousness, and self-perception of spirituality to the agreement with the SCC ruling and the option for a patient with ALS to request PAD. A univariate logistic regression was initially performed and variables with p values ≤0.20 were selected for multivariate analysis; those with p value ≤0.10 were included in the final model.

All p values were 2-sided and considered significant if ≤0.05. Stata software (v12.0) was used for all statistical analyses.

RESULTS

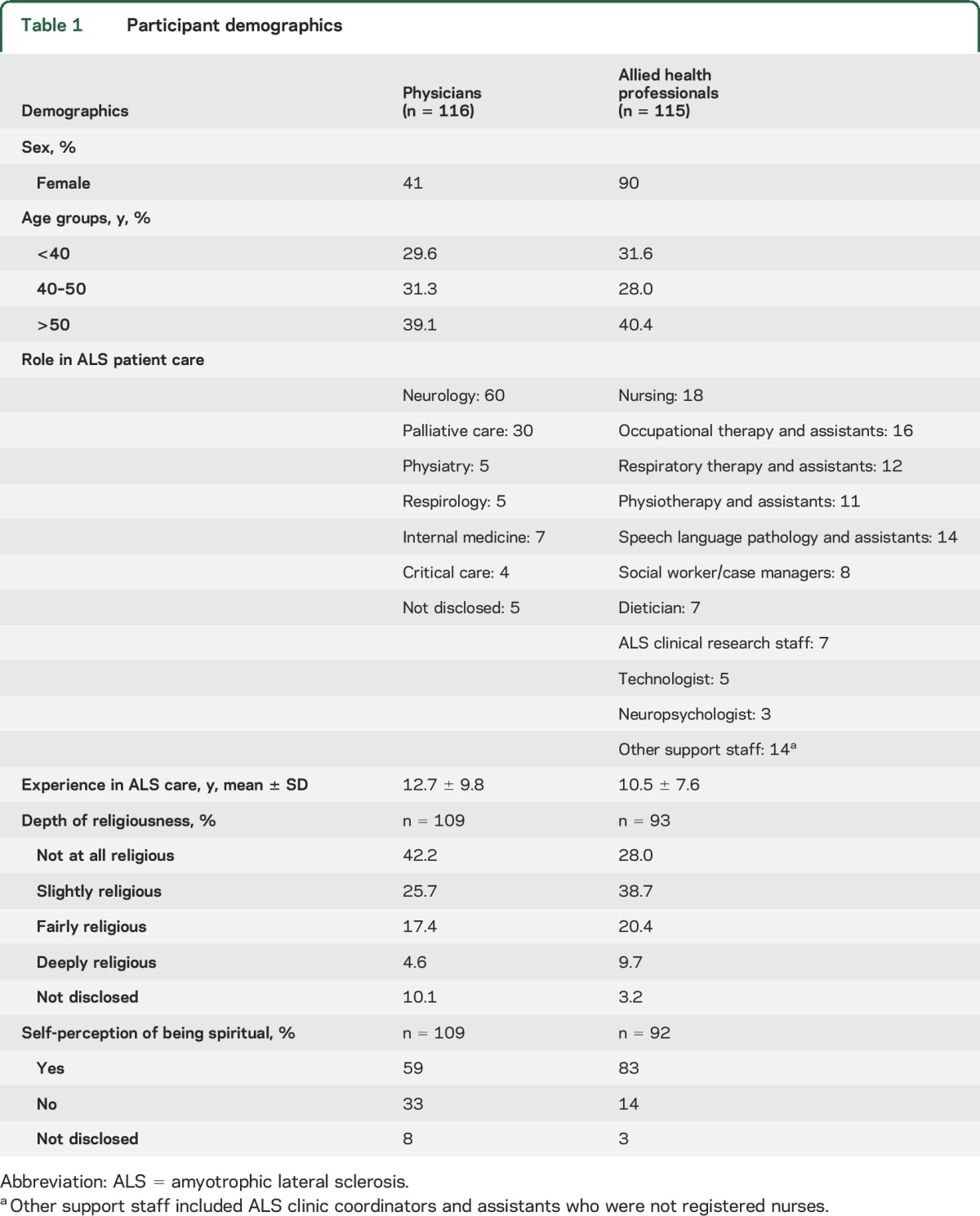

Responses were received from 116 physicians and 115 AHP (table 1) with experience in the care of patients with ALS representing all 15 Canadian academic ALS clinics. The direct invitation survey link was distributed to 113 physicians and 75 AHP and yielded 84 physician and 56 AHP participants for an overall response rate of 74%. In addition, ALS clinic leaders disseminated the open survey link to an estimated 108 individuals (the exact number could not be tracked for the forwarded open link). This open link collector yielded 62 responses (3 physicians and 59 AHP) and had an estimated response rate of 57%. The Canadian Society of Palliative Care Physicians forwarded the survey link to an e-mail list of 192 palliative care physicians inviting only those with experience managing patients with ALS to participate. This yielded 29 palliative care physician participants. The response rate could not be estimated as only those palliative care physicians with experience managing ALS were invited to participate. Mean number of years of experience in ALS patient care was 12.7 ± 9.8 years for physicians and 10.5 ± 7.6 years for the AHP. Demographic data are summarized in table 1.

Table 1.

Participant demographics

Attitudes toward the SCC ruling.

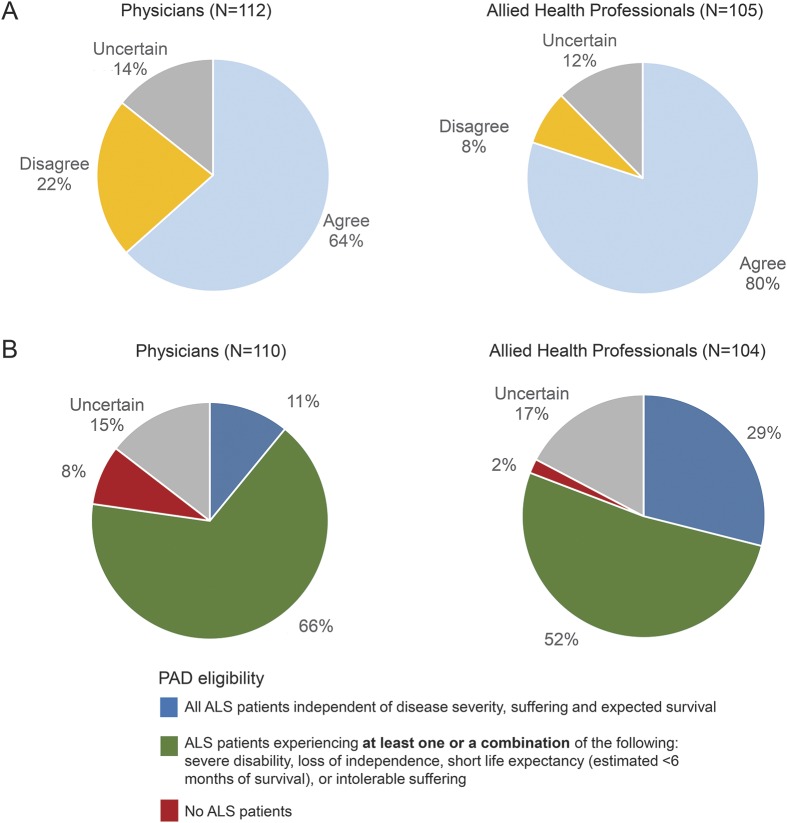

The majority of physicians (64%) and a higher proportion of AHP (80%, p < 0.01) agreed with the SCC ruling on PAD (figure 1A). Respondents' interpretation of the SCC language “enduring suffering that is intolerable to the individual in the circumstances of his or her condition”5 would include both intolerable physical suffering (95% of physicians and 97% of AHP) and emotional suffering (73% of physicians and 80% of AHP) that was not optimally controlled by palliative care. A minority of respondents interpreted the SCC ruling as legalizing PAD only for patients who have terminal medical conditions (29% of physicians and 38% of AHP) whereby patients with nonterminal but incurable conditions would not be eligible.

Figure 1. Attitudes toward the Supreme Court of Canada ruling on the legalization of physician-assisted death (PAD) and PAD eligibility for patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

(A) Attitudes of physicians and allied health professionals (AHP) toward the Supreme Court of Canada ruling on the legalization of PAD. A higher proportion of AHP agreed with the ruling (p < 0.01). (B) Attitudes of physicians and AHP toward PAD eligibility for patients with ALS based on the Supreme Court of Canada ruling. A higher proportion of AHP agreed with PAD eligibility independent of ALS disease severity (p < 0.005).

Attitudes toward PAD for patients with ALS.

The majority of respondents (77% of physicians and 81% of AHP, figure 1B: blue plus green portions of pie chart) believed that PAD should be eligible for patients with ALS under the interpretation of the SCC ruling. There was a lack of consensus regarding the circumstances in which PAD should be accessible and 8% of physicians believed that PAD should be ineligible to all patients with ALS (figure 1B).

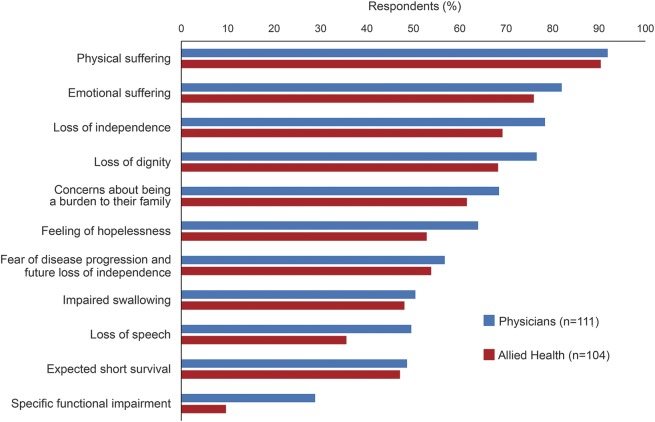

Most participants considered that physical suffering (92% of physicians and 90% of AHP), emotional suffering (82% of physicians and 76% AHP), and loss of independence (78% of physicians and 69% of AHP) would be the most common factors that would prompt patients with ALS to request PAD (figure 2), and that PAD should be an option only for patients presenting with at least one of the following: severe disability, loss of independence, expected survival less than 6 months, or intolerable suffering (figure 1B).

Figure 2. Physicians’ and allied health professionals’ opinions regarding amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) patients' motivating factors for requesting physician-assisted death (PAD).

Physical suffering, emotional suffering, and loss of independence were the most common factors that would drive patients with ALS to consider PAD in the opinions of physicians (blue) and allied health professionals (red).

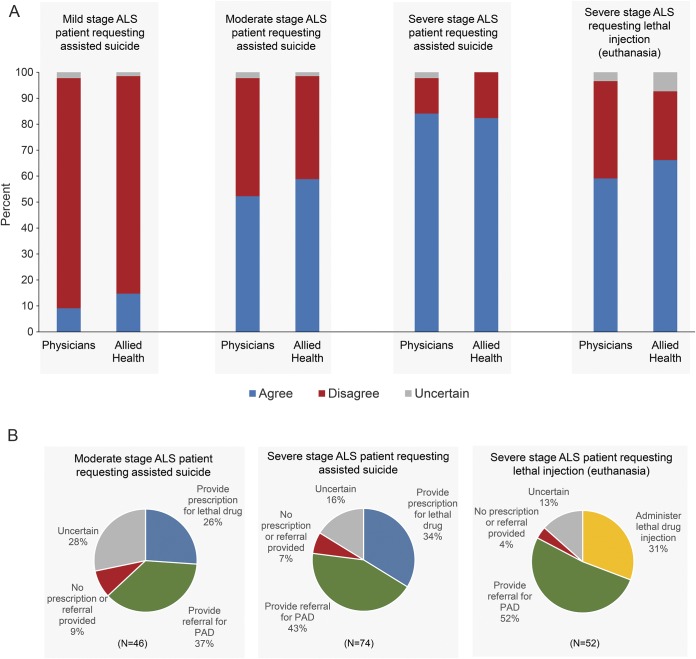

Based on respondents' interpretation of the SCC ruling, participants agreed that a patient with moderate stage ALS (52% of physicians and 59% of AHP) and severe stage ALS (84% of physicians and 82% of AHP) should be eligible for physician-assisted suicide. A lower proportion of respondents agreed with the option for physician-administered lethal injection (voluntary active euthanasia) for the patient with severe stage ALS (59% of physicians and 66% of AHP). Only 9% of physicians and 15% of AHP agreed with PAD eligibility for a patient with mild stage ALS (figure 3A). Eighty percent of physicians agreed that there was a distinction between palliative sedation and PAD and 60% believed that palliative sedation would be accessible to a patient with severe stage ALS at their centers. However, only 30% were aware of a palliative sedation protocol in place.

Figure 3. Physicians’ and allied health professionals’ attitudes toward physician-assisted death (PAD) for patients with advancing amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) severity.

(A) Attitudes of physicians (n = 88) and allied health professionals (n = 68) toward PAD requested by patients with ALS presenting in mild, moderate, and severe disease stages. No differences were found between physicians and allied health professionals (p > 0.05). (B) Physician-anticipated participation in PAD for advancing ALS disease (responses only from those physicians supporting PAD). PAD consists of physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia.

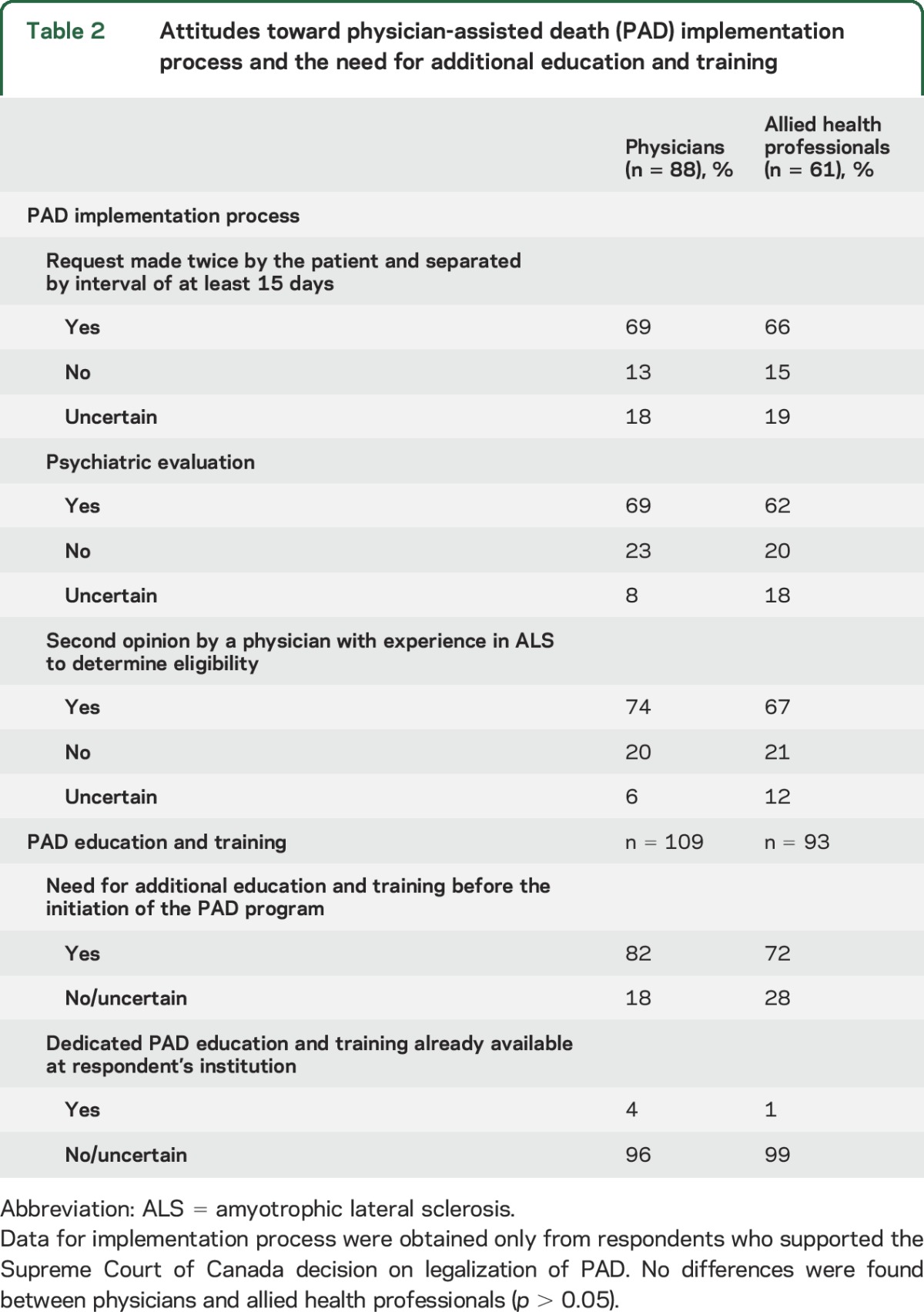

While the majority of physicians involved in the care of patients with ALS agreed with PAD eligibility for patients with more advanced disease under the SCC ruling, the majority (82% of physicians and 72% of AHP) also felt unprepared for the initiation of this program and favored the development of PAD training modules and guidelines (table 2). Only a minority of physicians who agreed with PAD eligibility in each scenario were willing to actively participate by providing a prescription for a lethal dose of an oral medication in the moderate (26%) and severe (34%) stage ALS scenarios, or administration of an IV lethal injection for active euthanasia in the severe stage ALS scenario (31%). Instead, most physicians preferred to refer the patient to a third party to provide PAD (figure 3B).

Table 2.

Attitudes toward physician-assisted death (PAD) implementation process and the need for additional education and training

The majority of respondents believed a second opinion by a clinician with ALS expertise was required to confirm PAD eligibility (74% of physicians and 67% of AHP, table 2) and an assessment by psychiatry was required to assess for a treatable psychiatric illness (69% of physicians and 62% of AHP, table 2). Sixty-nine percent of physicians and 66% of AHP believed that the request for PAD should be made more than once and separated by an interval of at least 15 days (table 2).

The depth of responder religiousness, but not spirituality, inversely influenced agreement with the SCC ruling and agreement with PAD for patients with ALS in a multivariate logistic regression. There were no age, sex, occupation, years of experience, or regional differences found across Canadian provinces regarding agreement with the SCC ruling and PAD for patients with ALS (data not shown).

Subgroup analysis was performed to determine if there were opinion differences between physicians involved in the diagnosis and primary management of ALS as compared to palliative care experts. Results demonstrated no differences in opinions regarding PAD, but palliative care experts who agreed with PAD in each scenario were less willing to provide lethal prescriptions and administer lethal injections to requesting patients (moderate stage ALS: 38% vs 10%, severe stage ALS: 36% vs 27%; p > 0.05).

DISCUSSION

As stakeholders begin to draft legislation, policies, and guidelines for PAD in Canada,16–20 it will be important to develop disease-specific approaches for unique conditions such as ALS. This study describes the results of a cross-Canada survey of ALS health care providers and palliative care experts gauging their perspectives on the recent SCC ruling to legalize PAD and their willingness to participate in PAD for patients with ALS. Overall, the majority of respondents agreed with the SCC ruling on PAD. The support was higher among AHP than physicians, which may reflect a less active role in the PAD process for nonphysicians. Agreement was lower among respondents who were more religious. Respondents generally believed that patients with moderate or severe ALS would meet the SCC's criteria for PAD, while those with mild ALS would not qualify. Also, the majority believed that patients with ALS requesting PAD require a second opinion by an ALS expert to determine eligibility, require assessment by a psychiatrist, and the request must be made twice separated by at least 15 days before proceeding with PAD. Despite the high levels of support for legalizing PAD, only a minority of physicians would be willing to directly provide a lethal prescription or injection to an eligible patient with ALS.

Canadian physicians with experience in the care of ALS appear to be more supportive of the SCC ruling than their colleagues. A Canadian Medical Association survey of all physician members in 2014 revealed only 45% support for the legalization of PAD21 and palliative care physician support for PAD may be as low as 30%.22 This study and previous surveys reveal that only a minority of physicians are prepared to directly participate in PAD, which indicates a need for a robust and easily accessible referring system to willing providers. It also highlights the need for additional education and training programs before PAD is initiated in Canada.

Despite high levels of support for PAD, the survey revealed a small number of respondents who remain strongly opposed. The right of conscientious objection is well-recognized in biomedical ethics, and there remains a struggle to find a balance between a physician's right not to participate in PAD and the patients' right for equal access to legal medical services.4 These opposing interests will continue to challenge society for controversial medical issues such as PAD and abortion, which is still disputed despite legalization in Canada for almost 3 decades.23

Only a minority of ALS health care providers believe PAD should be available to patients with ALS at all disease stages (11% of physicians and 29% of AHP), which is not unexpected given that ALS is a heterogeneous disease with variable progression and 10%–15% of patients have a prolonged survival.24 In addition, there remains no reliable diagnostic biomarker for ALS and diagnosis relies on clinical assessment, which is often more uncertain in early disease phases. This study will inform the process of developing PAD eligibility criteria that might include disease staging for ALS.

In severe stage ALS, there is an alternative to PAD. For patients with advanced disease, there exists an option for respiratory support/feeding tube withdrawal and palliative sedation, which would include the use of medications to relieve respiratory distress and suffering, but is not expected to hasten death.25 A majority of physicians agreed that there is a distinction between PAD and palliative sedation and most believed that palliative sedation was currently available at their centers.

Respondents believed that intolerable physical or emotional suffering were the most important driving factors for patients to choose PAD and believed that palliative care should be optimized before accessing PAD. Prior studies gauging patients' perspectives in Oregon showed that request for PAD was motivated by a desire to control the circumstances of death and avoid a state of dependence.26,27 Patients with ALS are less likely than patients with cancer or heart failure to request PAD because of refractory pain and emotional symptoms.28 Input from Canadian patients with ALS and caregivers will be essential to ascertain which factors they perceive as motivators for PAD to help improve care and for the determination of eligibility criteria.

Most ALS clinicians and AHP believed that a second opinion from an ALS expert to confirm eligibility and a psychiatric evaluation to assess for reversible mood disorders should be required for PAD eligibility. A prior study has shown that depression is rare in patients with ALS who receive PAD, but patients were not uniformly assessed by psychiatry.29 Other jurisdictions that have legalized PAD do not routinely require formal psychiatric assessment1 and the current proposed guidelines from the Canadian Medical Association16 likewise would not require psychiatric consultation. This is understandable given the logistical challenges and delays involved in providing a psychiatric evaluation to all patients requesting PAD, but it may be feasible for rare diseases like ALS.

The Canadian Medical Association interim guidelines proposed assessment of decision-making capacity by the patient's physician.16 Cognition in ALS is often affected and it is estimated that up to 50%–60% of patients with ALS have frontal lobe deficits30 that can impair judgment and decision-making. Therefore, patients with ALS with cognitive impairment should require a formal capacity assessment by psychiatry/neuropsychology before accessing PAD.

Strengths of this study include a robust survey response rate of 74% with participation from physicians and AHP at all academic ALS clinics in Canada spanning 8 provinces. The results of this study may have limited generalizability and results may not be applicable to other terminal diseases or jurisdictions. In addition, a survey response bias may exist whereby those individuals most opposed to PAD chose not to participate and their opinions were not captured.

Patient and caregiver input are essential in the PAD implementation process31,32 and additional surveys are required to capture their perspectives. Given the short timeframe mandated by the SCC's decision, it was important to disseminate ALS health care provider perspectives so that they may inform the policy debate at this critical stage.

Clinicians and health care providers managing ALS on the front lines support the SCC decision on the legalization of PAD and there is majority agreement that PAD should be available for patients with moderate to severe stages of ALS with physical or emotional suffering. However, most clinicians are unwilling to provide lethal prescriptions or injections to eligible patients and additional training and guidelines are required prior to the implementation of this program. Further studies are required to include the perspective of patients and caregivers who suffer from the everyday consequences of ALS in order to inform the urgent PAD policy debate.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Catarina Downey, Dr. Wendy Johnston, Dr. James Perry, and Dr. Larry Robinson for reviewing the questionnaire and providing feedback.

GLOSSARY

- AHP

allied health professionals

- ALS

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- ALSFRS-R

ALS Functional Rating Scale

- PAD

physician-assisted death

- SCC

Supreme Court of Canada

Footnotes

Editorial, page 1072

Supplemental data at Neurology.org

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Agessandro Abrahao made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work; the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data; and manuscript drafting and critical revision. Dr. Abrahao approved the final version of this manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. James Downar made substantial contributions to the design of the work, the acquisition and interpretation of data, and the manuscript drafting and critical revision. Dr. Downar approved the final version of this manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Hanika Pinto made substantial contributions to the design of the work, the acquisition and interpretation of data, and the manuscript drafting and critical revision. Dr. Pinto approved the final version of this manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Nicolas Dupré made substantial contributions to the design of the questionnaire, the acquisition of data, and the manuscript critical revision. Dr. Dupré approved the final version of this manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Aaron Izenberg made substantial contributions to the design of the questionnaire and the manuscript critical revision. Dr. Izenberg approved the final version of this manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. William Kingston made substantial contributions to the design of the questionnaire and the manuscript critical revision. Dr. Kingston approved the final version of this manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Lawrence Korngut made substantial contributions to the design of the questionnaire, the acquisition of data, and the manuscript critical revision. Dr. Korngut approved the final version of this manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Colleen O'Connell made substantial contributions to the design of the questionnaire, the acquisition of data, and the manuscript critical revision. Dr. O'Connell approved the final version of this manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Nicolae Petrescu made substantial contributions to the design of the questionnaire and the manuscript critical revision. Dr. Petrescu approved the final version of this manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Christen Shoesmith made substantial contributions to the design of the questionnaire, the acquisition of data, and the manuscript critical revision. Dr. Shoesmith approved the final version of this manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Anu Tandon made substantial contributions to the design of the questionnaire, the acquisition of data, and the manuscript critical revision. Dr. Tandon approved the final version of this manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Ana Beatriz Vargas-Santos made substantial contributions to the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data and the manuscript drafting and critical revision. Dr. Vargas-Santos approved the final version of this manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Lorne Zinman made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work; the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data; and the manuscript drafting and critical revision. Dr. Zinman approved the final version of this manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

STUDY FUNDING

Dr. Vargas-Santos received a fellowship funding from Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation of Brazil. Dr. Lorne Zinman is supported by the Temerty family foundation.

DISCLOSURE

A. Abrahao reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. J. Downar is the former co-chair of the Physicians' Advisory Council for Dying with Dignity Canada, a not-for-profit organization that advocated for the legalization of physician-assisted dying in Canada. H. Pinto, N. Dupré, A. Izenberg, W. Kingston, L. Korngut, C. O'Connell, N. Petrescu, C. Shoesmith, A. Tandon, A. Vargas-Santos, and L. Zinman report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schedule A: legal status of physician-assisted death (PAD) in jurisdictions with legislation. Available at: https://www.cma.ca/Assets/assets-library/document/en/advocacy/EOL/Legal-status-physician-assisted-death-jurisdictions-legislation.pdf#search=sche2dule%20a%3A%20legal%20status 2015. Accessed March 10, 2016.

- 2.Steck N, Egger M, Maessen M, Reisch T, Zwahlen M. Euthanasia and assisted suicide in selected European countries and US states: systematic literature review. Med Care 2013;51:938–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lavery JV, Dickens BM, Boyle JM, Singer PA. Bioethics for clinicians: 11: euthanasia and assisted suicide. CMAJ 1997;156:1405–1408. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Canadian Medical Association. CMA Policy: euthanasia and assisted death (update 2014). Available at: https://www.cma.ca/Assets/assets-library/document/en/advocacy/EOL/CMA_Policy_Euthanasia_Assisted%20Death_PD15-02-e.pdf. Accessed March 10, 2016.

- 5.Carter v Canada (attorney general), 2015 SCC 5. 2015.

- 6.Webster PC. Canada to legalise physician-assisted dying. Lancet 2015;385:678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Veldink JH, Wokke JHJ, van der Wal G, Vianney de Jong JMB, van den Berg LH. Euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide among patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in the Netherlands. N Engl J Med 2002;346:1638–1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maessen M, Veldink JH, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, et al. Euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a prospective study. J Neurol 2014;261:1894–1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Brinkman-Stoppelenburg A, Penning C, de Jong-Krul GJF, van Delden JJM, van der Heide A. Trends in end-of-life practices before and after the enactment of the euthanasia law in the Netherlands from 1990 to 2010: a repeated cross-sectional survey. Lancet 2012;380:908–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maessen M, Veldink JH, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, et al. Trends and determinants of end-of-life practices in ALS in the Netherlands. Neurology 2009;73:954–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hedberg K, Hopkins D, Leman R, Kohn M. The 10-year experience of Oregon's Death With Dignity Act: 1998–2007. J Clin Ethics 2009;20:124–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Downar J, Bailey TM, Kagan J, Librach SL. Physician-assisted death: time to move beyond yes or no. CMAJ 2014;186:567–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Downie J. Carter v. Canada: what's next for physicians? CMAJ 2015;187:481–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Attaran A. Unanimity on death with dignity: legalizing physician-assisted dying in Canada. N Engl J Med 2015;372:2080–2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cedarbaum JM, Stambler N, Malta E, et al. The ALSFRS-R: a revised ALS functional rating scale that incorporates assessments of respiratory function: BDNF ALS Study Group (Phase III). J Neurol Sci 1999;169:13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Canadian Medical Association. Principles-based recommendations for a Canadian approach to assisted dying. Available at: https://www.cma.ca/Assets/assets-library/document/en/advocacy/cma-framework_assisted-dying_final-dec-2015.pdf. Accessed March 10, 2016.

- 17.The College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario. CPSO interim guidance on physician-assisted death. Available at: http://www.cpso.on.ca/CPSO/media/documents/Policies/Policy-Items/Interim-Guidance-PAD.pdf?ext=.pdf. Accessed March 10, 2016.

- 18.College of Physicians and Surgeons of Alberta. Advice to the profession: physician-assisted death (PAD). Available at: http://www.cpsa.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/AP_PAD.pdf. Accessed March 10, 2016.

- 19.College of Physicians and Surgeons of British Columbia. Legislative guidance: physician-assisted dying. Available at: https://www.cpsbc.ca/files/pdf/Physician-assisted-Dying-DRAFT-2015-12-16.pdf. Accessed March 10, 2016.

- 20.College of Physicians and Surgeons of Manitoba. Standard of practice for physician assisted death (PAD). Available at: http://cpsm.mb.ca/cjj39alckF30a/wp-content/uploads/PAD/PADSchM.pdf. Accessed March 10, 2016.

- 21.Canadian Medical Association. A Canadian approach to assisted dying: CMA member dialogue. Available at: https://www.cma.ca/Assets/assets-library/document/en/advocacy/Canadian-Approach-Assisted-Dying-e.pdf. Accessed March 10, 2016.

- 22.Canadian Society of Palliative Care Physicians. Position on euthanasia and assisted suicide. Available at: http://www.cspcp.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/CSPCP-Position-on-Euthanasia-and-Assisted-Suicide-Feb-6-2015.pdf. Accessed March 10, 2016.

- 23.Shaw J, Downie J. Welcome to the wild, wild north: conscientious objection policies governing Canada's medical, nursing, pharmacy, and dental professions. Bioethics 2014;28:33–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Swinnen B, Robberecht W. The phenotypic variability of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat Rev Neurol 2014;10:661–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitsumoto H, Rabkin JG. Palliative care for patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: “prepare for the worst and hope for the best.” JAMA 2007;298:207–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ganzini L, Goy ER, Dobscha SK. Why Oregon patients request assisted death: family members' views. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23:154–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loggers ET, Starks H, Shannon-Dudley M, Back AL, Appelbaum FR, Stewart FM. Implementing a death with dignity program at a comprehensive cancer center. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1417–1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maessen M, Veldink JH, van den Berg LH, Schouten HJ, van der Wal G, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD. Requests for euthanasia: origin of suffering in ALS, heart failure, and cancer patients. J Neurol 2010;257:1192–1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ganzini L, Goy ER, Dobscha SK. Prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients requesting physicians' aid in dying: cross sectional survey. BMJ 2008;337:a1682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Woolley SC, Strong MJ. Frontotemporal dysfunction and dementia in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurol Clin 2015;33:787–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stutzki R, Weber M, Reiter-Theil S, Simmen U, Borasio GD, Jox RJ. Attitudes towards hastened death in ALS: a prospective study of patients and family caregivers. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener 2014;15:68–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ganzini L, Johnston WS, McFarland BH, Tolle SW, Lee MA. Attitudes of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and their care givers toward assisted suicide. N Engl J Med 1998;339:967–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.