Abstract

Objective:

Our aim was to evaluate the diagnostic yield of transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) in consecutive patients with ischemic stroke (IS) fulfilling the diagnostic criteria of embolic strokes of undetermined source (ESUS).

Methods:

We prospectively evaluated consecutive patients with acute IS satisfying ESUS criteria who underwent in-hospital TEE examination in 3 tertiary care stroke centers during a 12-month period. We also performed a systematic review and meta-analysis estimating the cumulative effect of TEE findings on therapeutic management for secondary stroke prevention among different IS subgroups.

Results:

We identified 61 patients with ESUS who underwent investigation with TEE (mean age 44 ± 12 years, 49% men, median NIH Stroke Scale score = 5 points [interquartile range: 3–8]). TEE revealed additional findings in 52% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 40%–65%) of the study population. TEE findings changed management (initiation of anticoagulation therapy, administration of IV antibiotic therapy, and patent foramen ovale closure) in 10 (16% [95% CI: 9%–28%]) patients. The pooled rate of reported anticoagulation therapy attributed to abnormal TEE findings among 3,562 acute IS patients included in the meta-analysis (12 studies) was 8.7% (95% CI: 7.3%–10.4%). In subgroup analysis, the rates of initiation of anticoagulation therapy on the basis of TEE investigation did not differ (p = 0.315) among patients with cryptogenic stroke (6.9% [95% CI: 4.9%–9.6%]), ESUS (8.1% [95% CI: 3.4%–18.1%]), and IS (9.4% [95% CI: 7.5%–11.8%]).

Conclusions:

Abnormal TEE findings may decisively affect the selection of appropriate therapeutic strategy in approximately 1 of 7 patients with ESUS.

The skepticism toward the diagnostic utility of transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) in patients with cryptogenic stroke (CS) is increasing because of relatively high intrarater variability and the low prevalence of identified cardiac conditions causally associated with the ischemic event.1,2 This controversy led to the currently proposed criteria for the definition of embolic strokes of undetermined source (ESUS) that do not include TEE among the mandatory diagnostic workup of ESUS clinical entity.3 However, TEE is widely available1 and most primary stroke centers may have access to it while all comprehensive stroke centers are required to have it.4

We sought to evaluate both the diagnostic yield of TEE and the effect of TEE findings on therapeutic management in consecutive patients with ischemic stroke (IS) fulfilling the diagnostic criteria of ESUS. In addition, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to estimate the cumulative effect of TEE findings on secondary stroke prevention management among different IS subgroups.

METHODS

Prospective cohort.

We prospectively evaluated consecutive patients with IS satisfying ESUS diagnostic criteria from 3 tertiary care stroke centers (Attikon University Hospital, Athens, and University Hospital of Ioannina, Greece; University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis) during a 12-month period (January 2014 to December 2014). We prospectively recorded baseline characteristics and outcome measures for all acute IS (AIS) patients and further classified them according to the Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST)5 and ESUS criteria,3 as described in detail in the e-Methods at Neurology.org.

The patients with IS who fulfilled ESUS diagnostic criteria were scheduled to undergo additional diagnostic workup with TEE to estimate both the diagnostic yield and the effect of TEE findings in the therapeutic management of patients with ESUS. All TEE examinations were performed by experienced cardiologists in each participating institution who were blinded to patients' clinical and imaging data. TEE findings were further classified as major or minor/unclear risk cardioembolic sources, according to the recommendations published by the European Association of Echocardiography.6

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

The study was approved by the ethics committees of the participating institutions, and informed consent was obtained from all patients (or guardians of patients).

Systematic review and meta-analysis.

We additionally performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of available observational studies reporting changes in management of IS patients after TEE examination. The methodology of the meta-analysis and further information on statistical analyses are available in the e-Methods.

RESULTS

Prospective cohort.

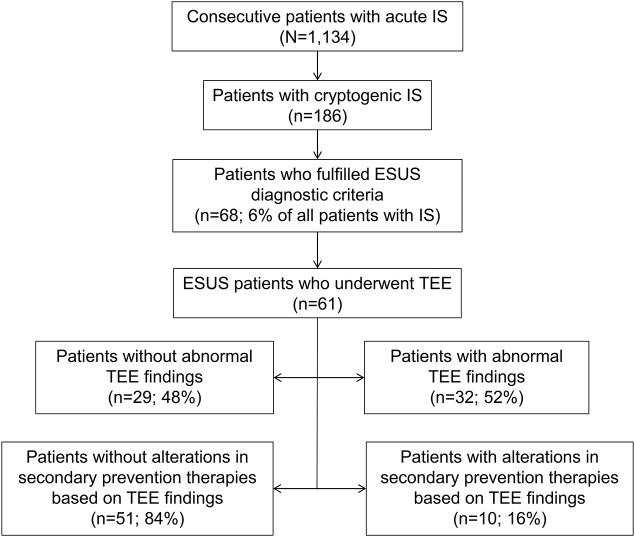

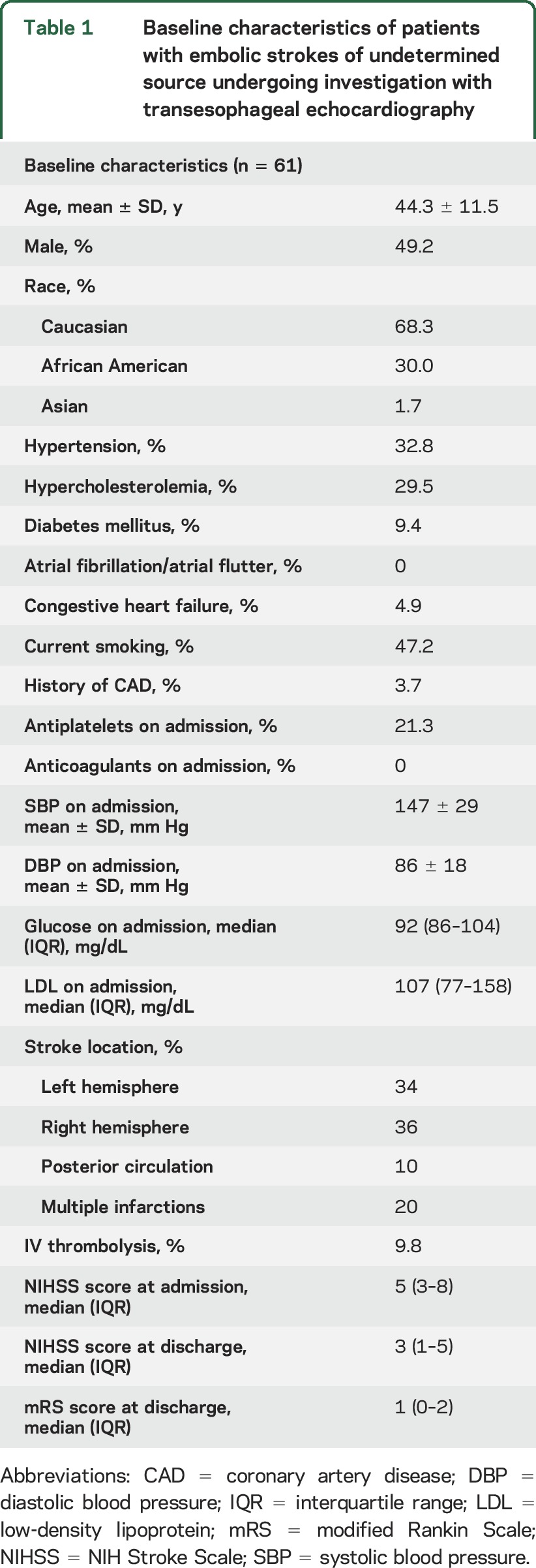

A total of 1,134 IS patients were admitted during the study period in the 3 participating centers. We identified 186 patients (16%) with CS, while the diagnosis of ESUS was confirmed in 68 cases (6% of IS patients and 37% of patients with CS; figure 1). A total of 61 patients with ESUS underwent investigation with TEE (90%), while in the remaining 7 patients we were unable to perform TEE during hospitalization because of early death (n = 1), patient noncompliance (n = 4), and patient denial to undergo this invasive examination (n = 2). The baseline characteristics of our study population are presented in table 1.

Figure 1. Study flowchart diagram.

The flowchart presents the selection of included patients and the changes in therapeutic management after examination with TEE. ESUS = embolic stroke of undetermined source; IS = ischemic stroke; TEE = transesophageal echocardiography.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with embolic strokes of undetermined source undergoing investigation with transesophageal echocardiography

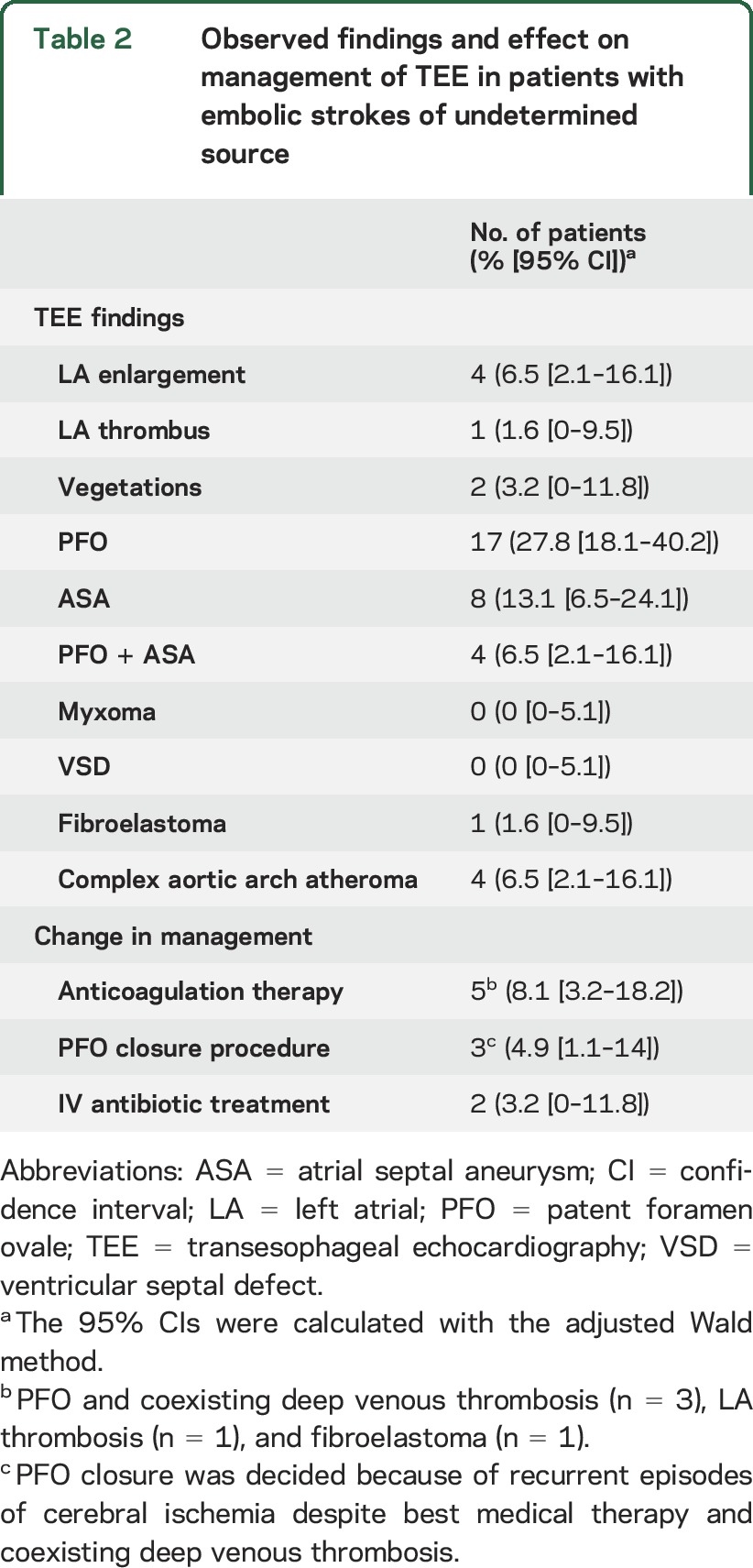

TEE revealed abnormal findings in 52% (95% confidence interval [CI] by the adjusted Wald method: 40%–65%) of the study population (table 2). The presence of valvular vegetations was documented in 2 cases (3% [95% CI: 0%–12%]), while left atrial thrombosis was detected in one patient (2% [95% CI: 0%–9%]). Paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in this patient was detected after TEE examination in the iterative 24-hour Holter examination. Neither myxomas nor ventricular septal defects were detected in any of the TEE examinations. TEE findings affected therapeutic management in 10 (16% [95% CI: 9%–28%]) patients with ESUS. More specifically, anticoagulation therapy was initiated in 5 patients, while the diagnosis of endocarditis, except for the clinical presentation, was confirmed by TEE in 2 patients who received treatment with IV antibiotics. Finally, 3 other patients underwent a patent foramen ovale (PFO) closure procedure because of the presence of large shunt on TEE and the history of multiple recurrent episodes of cryptogenic cerebrovascular ischemia despite medical treatment (figure 1), because they also had a history of deep venous thrombosis.

Table 2.

Observed findings and effect on management of TEE in patients with embolic strokes of undetermined source

Systematic review and meta-analysis.

The study selection process is described in detail in the e-Methods and presented in figure e-1, excluded studies with reasons for exclusion are presented in table e-1, and baseline characteristics and outcomes of included studies7–17 are summarized in table e-2.

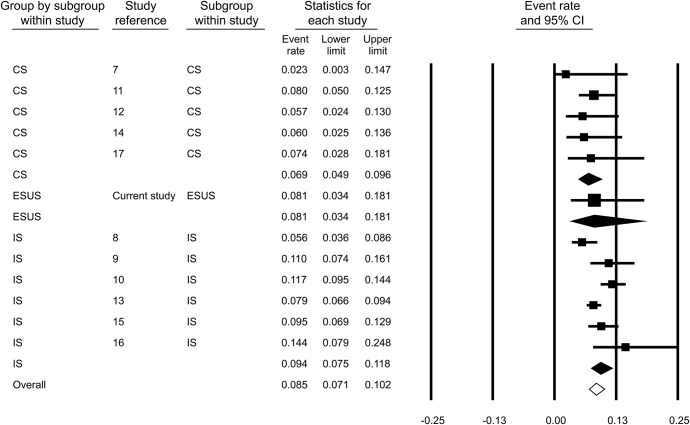

The pooled rate of reported changes to anticoagulation treatment among 3,562 total AIS patients after TEE investigation was 8.7% (95% CI: 7.3%–10.4%; figure e-2). Publication bias was not evident in either the funnel plot inspection (figure e-3) or in the Egger statistical test for funnel plot asymmetry (p = 0.361). Substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 46.8%, p = 0.037 for Cochran Q test) was identified between studies. In subgroup analysis, the prevalence rates of changes to anticoagulation after TEE examination was not found to be significantly different (p = 0.315) among patients with CS (6.9% [95% CI: 4.9%–9.6%]; figure 2), ESUS (8.1% [95% CI: 3.4%–18.1%]), and IS (9.4% [95% CI: 7.5%–11.8%]; figure 2). Among the 3 subgroups, evidence of heterogeneity was found only in the IS subgroup (I2 = 68.8%, p = 0.007 for Cochran Q).

Figure 2. Pooled prevalence rates of reported anticoagulation initiation after investigation with transesophageal echocardiography among stroke subgroups.

CI = confidence interval; CS = cryptogenic stroke; ESUS = embolic stroke of undetermined source; IS = ischemic stroke.

We also estimated the percentage of patients who were started on treatment with anticoagulants after TEE according to current stroke guidelines18 in each included study protocol (table e-2). The overall pooled rate was 4.1% (95% CI: 2.8%–6.1%; figure e-4) with substantial heterogeneity among studies (I2 = 74.3%, p < 0.001 for Cochran Q). In subgroup analysis, the prevalence rates were not found to differ significantly among patients with CS (5.3% [95% CI: 3.5%–7.8%]; figure e-5), ESUS (8.1% [95% CI: 3.4%–18.1%]), and IS (3.7% [95% CI: 2.1%–6.4%]; figure e-5). Among the 3 subgroups, evidence of heterogeneity was found only in the IS subgroup (I2 = 85.7%, p < 0.001 for Cochran Q). However, it should be noted that in most study protocols, only the presence of intracavitary thrombus was considered as a clear indication for anticoagulation initiation, as the concurrence of deep venous thrombosis in patients with PFO was not reported.

DISCUSSION

Our findings indicate that approximately half of the patients with ESUS have abnormal findings on TEE examination. These sources of potential aortogenic/cardiogenic embolism had been missed by the initial transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) screening and were consequently identified during the TEE investigation. Of note, our data highlight that these abnormal TEE findings may have a decisive effect on the selection of appropriate therapeutic strategy in 1 of 7 ESUS patients. Moreover, the results of our meta-analysis indicate that our strategy for anticoagulant initiation in ESUS patients is generally in line with those previously reported for IS/CS patients.

PFO and atrial septal aneurysm (ASA) are the most common findings that were found in our cohort of ESUS patients undergoing TEE. These findings were missed by the initial evaluation with TTE, as it is known that TTE has a very poor sensitivity in the diagnosis of PFO (46% [95% CI: 41%–52%]) compared to the gold standard TEE.19 The need of TEE for detection of PFO is under debate because most findings lack evidence-based treatment recommendations. In a recently published meta-analysis from our study group, we found that medically treated patients with PFO do not have a higher risk of recurrent cryptogenic cerebrovascular events compared with those without PFO, while we documented no relation between the degree of PFO and the risk of future cerebrovascular events.20 According to the current American Heart Association/American Stroke Association guidelines,18 all ESUS patients with PFO were treated with antiplatelets, except for 3 patients with coexisting deep venous thrombosis who were treated with anticoagulation therapy according to current recommendations.

Even though most of the alternate therapies that have been implemented in IS patients with PFO mentioned above lack evidence-based recommendations—except for the administration of anticoagulants in case of concomitant deep venous thrombosis—we consider that PFO detection in young patients with embolic stroke patterns on neuroimaging and no traditional vascular risk factors not only can reveal the probable underlying mechanism of cerebral ischemia via paradoxical embolism21 but also may have a crucial role on secondary stroke prevention strategies. We decided to refer 3 patients from our study cohort to a PFO closure procedure because these patients had only large shunts and experienced recurrent ischemic events, despite the absence of conventional risk factors and while on medical treatment with antiplatelets or anticoagulants. The superiority of percutaneous PFO closure compared to medical treatment in the prevention of recurrent stroke in patients with cryptogenic IS and presence of “high risk” PFO (PFO size ≥2 mm or ASA presence or hyperactivity of septal aneurysm in TEE examination) is under evaluation in an ongoing randomized clinical trial (DEFENSE-PFO, NCT01550588), the first results of which are expected to be announced in 2017. Until the results of the aforementioned trial become available and according to current guidelines,18 PFO closure should be regarded as an expensive, invasive procedure of unclear benefit for patients with cerebral ischemia and PFO, and thus might only be considered for very particular cases.

Endocarditis is usually not diagnosed solely on routine TEE because clinical signs, laboratory examinations, and patient history usually point to the diagnosis. Nevertheless, TEE is considered the gold standard examination for the diagnosis of endocarditis and its complications, while it is particularly useful for excluding endocarditis in patients with negative cultures and atypical clinical presentation.22,23 The sensitivity and specificity of TTE in finding vegetations was reported to be 28% and 90%, respectively, while the corresponding values for TEE are 78% and 100%.23 In addition, TEE is superior to TTE for detecting abscesses, a complication of endocarditis usually accompanied by a more unfavorable clinical course.22,23 It should also be acknowledged that many stroke patients present with fever and increased inflammatory markers because of respiratory or urinary tract infections. Therefore, because of the low diagnostic yield of TTE, we consider that an endocarditis with atypical clinical findings and negative blood cultures could be undetected if TEE is not performed in the absence of a definite cause for the cerebral ischemic event. The 2 patients with valvular vegetations on TEE received IV antibiotic treatment in a timely manner and had a favorable functional outcome at discharge.

Spontaneous echo contrast is defined as the turbulent-like “smoke” pattern visible during echocardiography, which is considered to represent an interaction between erythrocytes and plasma proteins, and in particular fibrinogen.24 Its presence is considered to be suggestive of blood stasis in the left atrium, and thus closely related to atrial fibrillation and thromboembolism.25–28 Even though both spontaneous echo contrast and thrombus in the left atrium can present in some patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing TEE, it should be noted that the more prudent way to diagnose an underlying atrial fibrillation is prolonged rhythm monitoring. Finally, the presence of complex plaques in the aorta could be considered as a marker of generalized atherosclerosis and high vascular risk,29 while their presence in the aortic arch/ascending aorta is known to be associated with an increased risk of recurrent stroke and death.30

Finally, our systematic review and meta-analysis are in line with previous reports underscoring the substantial effect of TEE in initiating anticoagulation therapy in patients with IS or CS. More specifically, 8.1% (95% CI: 3.4%–18.1%) of our patients and 8.9% (95% CI: 7.4%–10.6%) of all patients included in the meta-analysis were started on anticoagulants after TEE examination. Oral anticoagulation was initiated in our cohort for the following indications: left atrial thrombosis (n = 1), fibroelastoma (n = 1), and PFO with coexisting deep venous thrombosis (n = 3).18 Earlier studies have also reported administration of anticoagulation therapy on the basis of abnormal TEE findings in CS patients for similar and additional indications: left atrial thrombus (n = 42),7–17 left ventricular thrombus (n = 3),13,15 spontaneous echo contrast (n = 9),9,11,14 PFO with coexisting deep venous thrombosis (n = 2),8,9 PFO and ASA concurrence (n = 51),11,14,15 PFO at rest with a history of stroke (n = 18),11 presence of thrombus or ulceration in the aorta (n = 45),9–15 and left ventricular dysfunction (n = 10).15,16 The initiation of anticoagulation was also reported in an additional 76 patients, without providing further clinical details or rationale for the change in management.9,13,16,17

Our study has limitations including the relatively limited sample size, the lack of central adjudication of abnormal TEE findings, and lack of standardization of TEE across participating centers. Our study population consisted of 61 ESUS patients with a mean age of 44 ± 12 years and a median NIH Stroke Scale score at hospital admission of 5 points. The small number and the relatively young age of our population could be partially attributed to the comprehensive diagnostic workup that all patients received in all institutions, as mentioned in the methods section, which revealed the underlying causes of cerebrovascular ischemia in a large proportion of the initial IS population (83.6% of the total 1,134 IS patients). Older patients are known to have more prevalent vascular risk factors but younger patients are more likely have a negative stroke workup and thus be categorized as CS.31 Moreover, all participating tertiary care stroke centers are referral centers for young patients (aged 45 years or younger) with cerebrovascular diseases and this may also have contributed in the lower mean age of our study population.32 However, it should be noted that the mean NIH Stroke Scale score of our ESUS patients (median 5 [3–8]) was very similar to the one previously reported from another single center stroke registry (median 5 [2–14]).33 No age or stroke severity criterion was used for the referral of patients to TEE examination, while in all cases, TEE was performed by specialized echocardiographers with substantial experience in the cardiac workup of CS blinded to both the clinical and imaging data.

Moreover, it should be noted that in 7 of the ESUS patients (10%), examination with TEE was not performed because of early death, patient noncompliance, or denial to undergo this invasive examination. Because TEE is an invasive examination, with some IS patients having relative or absolute contraindications, there is growing interest in the establishment of cardiovascular CT and MRI in the evaluation of stroke.34 Even though cardiac MRI can detect possible cardioembolic sources in CS patients,35 its diagnostic yield remains lower than that of TEE, thus verifying that up-to-date TEE remains the gold standard diagnostic modality in the evaluation of possible cardioembolic sources in the setting of cerebral ischemia.36,37 Nevertheless, these imaging modalities may provide crucial diagnostic information guiding therapeutic decisions in a minority of IS patients who cannot undergo TEE.

Finally, in the initial classification of the AIS patients, we used the TOAST classification system, which is regarded as the most widely used and approved form for etiologic stroke subtyping.5 Even though TOAST classification is thought to have a generally good concordance with the ASCO classification,38 the comprehensive character of ASCO classification allows the recording of important additional information, and may result in the classification of a lower proportion of TIA and minor stroke patients as CS.39 However, for the classification of AIS patients as ESUS, we used the sole and currently proposed criteria for this clinical entity,3 which are independent from the classification systems mentioned above.

The main limitation of our meta-analysis is associated with the detection of heterogeneity regarding the rate of initiation of anticoagulation therapy attributed to the TEE examination among the included 12 studies. Of note, our sensitivity analyses indicated that there was no heterogeneity in the pooled reported rates in the ESUS and CS subgroups. Moreover, the effect of TEE on initiation of anticoagulation therapy for secondary stroke prevention was practically identical in CS (1 of 14 patients) and ESUS (1 of 12 patients). This observation may be relevant to the expected results of ongoing phase III trials evaluating the safety and efficacy of rivaroxaban (NAVIGATE-ESUS, NCT02313909) or dabigatran (RE-SPECT ESUS, NCT02239120) in comparison to aspirin in patients with ESUS, in view of the findings of WARSS (Warfarin-Aspirin Recurrent Stroke Study Group) that failed to demonstrate the superiority of warfarin over aspirin for secondary stroke prevention in patients with CS.40 Another important limitation of our meta-analysis that should be considered is that neither the change in management nor the initiation of anticoagulation strategies was consistent among the studies included in the meta-analysis. Many of the reported procedures (percutaneous or surgical PFO closure) or anticoagulant administration indications (PFO with/without ASA, spontaneous echo contrast) are not in accordance with current American Heart Association/American Stroke Association stroke guidelines.18 However, it should be noted that most of the study protocols included in the meta-analysis were conducted before the publication of the aforementioned guidelines (May 2014), when there was still uncertainty and discrepancies in the literature about the optimal management for many TEE findings in patients with CS. Apart from the diagnostic management strategies, the extent of diagnostic workup was also not consistent across included study protocols suggesting an overrepresentation of the CS population in studies with a limited diagnostic workup according to current standards.7

It thus seems that TEE examination may be a useful addition in the diagnostic workup of ESUS, since it can reveal potential sources of cardiogenic/aortic embolism that may have originally been missed by TTE. Consequently, therapeutic decision-making may be modified in terms of secondary prevention in ESUS patients with abnormal TEE findings, while anticoagulation therapy may be offered instead of antiplatelets in 1 of 12 ESUS patients if TEE is added in their diagnostic workup. Even though the original ESUS criteria do not specify duration of cardiac monitoring, ongoing trials suggest that 24-hour ECG monitoring as the lowest common denominator that should be a bare minimum across the stroke centers. We therefore consider that there is a high risk of underinvestigated and highly heterogeneous patients being enrolled in the ongoing trials, as they serve to the bare minimum set of tests as opposed to a more proactive approach suggested by the inclusion of TEE in our study protocol. In view of the former considerations and if our findings are reproduced by independent investigations, further refinement of the ESUS definition may be required.

Supplementary Material

GLOSSARY

- AIS

acute ischemic stroke

- ASA

atrial septal aneurysm

- CI

confidence interval

- CS

cryptogenic stroke

- ESUS

embolic stroke of undetermined source

- IS

ischemic stroke

- PFO

patent foramen ovale

- TEE

transesophageal echocardiography

- TOAST

Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment

- TTE

transthoracic echocardiography

Footnotes

Supplemental data at Neurology.org

Editorial, page 972

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr. Katsanos: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Dr. Bhole: acquisition of data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Dr. Frogoudaki: acquisition of data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Dr. Giannopoulos: critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Dr. Goyal: critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Dr. Vrettou: acquisition of data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Dr. Ikonomidis: critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Dr. Paraskevaidis: critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Dr. Pappas: acquisition of data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Dr. Parissis: critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Prof. Kyritsis: critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Prof. A.W. Alexandrov: critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Dr. Triantafyllou: critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Prof. Malkoff: critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Dr. Voumvourakis: critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Prof. A.V. Alexandrov: critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Dr. Tsivgoulis: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, study supervision.

STUDY FUNDING

Dr. Georgios Tsivgoulis has been supported by the European Regional Development Fund–Project St. Anne's University Hospital, Brno–International Clinical Research Center (FNUSA-ICRC) (CZ.1.05/1.1.00/02.0123).

DISCLOSURE

The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Manning WJ. Role of transesophageal echocardiography in the management of thromboembolic stroke. Am J Cardiol 1997;80:19D–28D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katsanos AH, Giannopoulos S, Frogoudaki A, et al. The diagnostic yield of transesophageal echocardiography in patients with cryptogenic cerebral ischaemia: a meta-analysis. Eur J Neurol 2016;23:569–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hart RG, Diener HC, Coutts SB, et al. Embolic strokes of undetermined source: the case for a new clinical construct. Lancet Neurol 2014;13:429–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alberts MJ, Latchaw RE, Selman WR, et al. Recommendations for comprehensive stroke centers: a consensus statement from the Brain Attack Coalition. Stroke 2005;36:1597–1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adams HP Jr, Bendixen BH, Kappelle LJ, et al. Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. TOAST. Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment. Stroke 1993;24:35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pepi M, Evangelista A, Nihoyannopoulos P, et al. Recommendations for echocardiography use in the diagnosis and management of cardiac sources of embolism: European Association of Echocardiography (EAE) (a registered branch of the ESC). Eur J Echocardiogr 2010;11:461–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Censori B, Colombo F, Valsecchi MG, et al. Early transoesophageal echocardiography in cryptogenic and lacunar stroke and transient ischaemic attack. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1998;64:624–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charbonnel C, Fanon L, Georges JL, et al. Usefulness of transesophageal echocardiography to optimize treatment after ischemic stroke. Ann Cardiol Angeiol 2014;63:300–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dawn B, Hasnie AM, Calzada N, et al. Transesophageal echocardiography impacts management and evaluation of patients with stroke, transient ischemic attack, or peripheral embolism. Echocardiography 2006;23:202–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Castro S, Papetti F, Di Angelantonio E, et al. Feasibility and clinical utility of transesophageal echocardiography in the acute phase of cerebral ischemia. Am J Cardiol 2010;106:1339–1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harloff A, Handke M, Reinhard M, et al. Therapeutic strategies after examination by transesophageal echocardiography in 503 patients with ischemic stroke. Stroke 2006;37:859–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katsanos AH, Patsouras D, Tsivgoulis G, et al. The value of transesophageal echocardiography in the investigation and management of cryptogenic cerebral ischemia: a single-center experience. Neurol Sci 2015;37:629–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khariton Y, House JA, Comer L, et al. Impact of transesophageal echocardiography on management in patients with suspected cardioembolic stroke. Am J Cardiol 2014;114:1912–1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rettig TC, Bouma BJ, van den Brink RB. Influence of transoesophageal echocardiography on therapy and prognosis in young patients with TIA or ischaemic stroke. Neth Heart J 2009;17:373–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strandberg M, Marttila RJ, Helenius H, et al. Transoesophageal echocardiography should be considered in patients with ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging 2008;28:156–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tatani SB, Fukujima MM, Lima JA, et al. Clinical impact of transesophageal echocardiography in patients with stroke without clinical evidence of cardiovascular sources of emboli. Arq Bras Cardiol 2001;76:453–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walpot J, Pasteuning WH, Hoevenaar M, et al. Transesophageal echocardiography in patients with cryptogenic stroke: does it alter their management? A 3-year retrospective study in a single non-referral centre. Acta Clin Belg 2006;61:243–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2014;45:2160–2236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katsanos AH, Psaltopoulou T, Sergentanis TN, et al. Transcranial Doppler versus transthoracic echocardiography for the detection of patent foramen ovale in patients with cryptogenic cerebral ischemia: a systematic review and diagnostic test accuracy meta-analysis. Ann Neurol 2016;79:625–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katsanos AH, Spence JD, Bogiatzi C, et al. Recurrent stroke and patent foramen ovale: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke 2014;45:3352–3359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kent DM, Ruthazer R, Weimar C, et al. An index to identify stroke-related vs incidental patent foramen ovale in cryptogenic stroke. Neurology 2013;81:619–625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kini V, Logani S, Ky B, et al. Transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography for the indication of suspected infective endocarditis: vegetations, blood cultures and imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2010;23:396–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leitman M, Peleg E, Rosenblat S, et al. Transesophageal echocardiography: an overview. Isr Med Assoc J 2001;3:198–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Merino A, Hauptman P, Badimon L, et al. Echocardiographic “smoke” is produced by an interaction of erythrocytes and plasma proteins modulated by shear forces. J Am Coll Cardiol 1992;20:1661–1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Black IW, Hopkins AP, Lee LC, Walsh WF. Left atrial spontaneous echo contrast: a clinical and echocardiographic analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 1991;18:398–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okura H, Inoue H, Tomon M, Nishiyama S, Yoshikawa T, Yoshida K. Transesophageal echocardiographic detection of cardiac sources of embolism in elderly patients with ischemic stroke. Intern Med 1999;38:766–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leung DY, Black IW, Cranney GB, Hopkins AP, Walsh WF. Prognostic implications of left atrial spontaneous echo contrast in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 1994;24:755–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kupczynska K, Kasprzak JD, Michalski B, Lipiec P. Prognostic significance of spontaneous echocardiographic contrast detected by transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography in the era of harmonic imaging. Arch Med Sci 2013;9:808–814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Katsanos AH, Giannopoulos S, Kosmidou M, et al. Complex atheromatous plaques in the descending aorta and the risk of stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke 2014;45:1764–1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Di Tullio MR, Russo C, Jin Z, et al. Aortic arch plaques and risk of recurrent stroke and death. Circulation 2009;119:2376–2382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nacu A, Fromm A, Sand KM, Waje-Andreassen U, Thomassen L, Naess H. Age dependency of ischaemic stroke subtypes and vascular risk factors in western Norway: the Bergen Norwegian Stroke Cooperation Study. Acta Neurol Scand 2016;133:202–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsivgoulis G, Putaala J, Sharma VK, et al. Racial disparities in early mortality in 1,134 young patients with acute stroke. Neurol Sci 2014;35:1041–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ntaios G, Papavasileiou V, Milionis H, et al. Embolic strokes of undetermined source in the Athens Stroke Registry: a descriptive analysis. Stroke 2015;46:176–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pagán RJ, Parikh PP, Mergo PJ, et al. Emerging role of cardiovascular CT and MRI in the evaluation of stroke. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2015;204:269–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baher A, Mowla A, Kodali S, et al. Cardiac MRI improves identification of etiology of acute ischemic stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis 2014;37:277–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zahuranec DB, Mueller GC, Bach DS, et al. Pilot study of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging for detection of embolic source after ischemic stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2012;21:794–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hamilton-Craig C, Sestito A, Natale L, et al. Contrast transoesophageal echocardiography remains superior to contrast-enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of patent foramen ovale. Eur J Echocardiogr 2011;12:222–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wolf ME, Sauer T, Alonso A, Hennerici MG. Comparison of the new ASCO classification with the TOAST classification in a population with acute ischemic stroke. J Neurol 2012;259:1284–1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Desai JA, Abuzinadah AR, Imoukhuede O, et al. Etiologic classification of TIA and minor stroke by A-S-C-O and causative classification system as compared to TOAST reduces the proportion of patients categorized as cause undetermined. Cerebrovasc Dis 2014;38:121–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mohr JP, Thompson JL, Lazar RM, et al. A comparison of warfarin and aspirin for the prevention of recurrent ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 2001;345:1444–1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.