Abstract

Purpose

To determine the ability of the Vulnerable Elders Survey (VES-13) to predict the composite outcome of functional decline and death within 12 months of breast cancer treatment among women ≥ 65 years with newly diagnosed stage I–III breast cancer.

Patients and Methods

We recruited 206 participants from ambulatory oncology clinics at an academic center between April 2008 and April 2013. Participants competed the VES-13 at baseline, just prior to neoadjuvant/adjuvant treatment. Our primary outcome, functional decline/death, was defined as a decrease in at least one point on the Activities of Daily Living (ADL) and/or Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) Scales, or death, from baseline to 12 months, Yes or No.

Results

184 (89%) participants completed 12 months of follow-up. Twenty-two percent developed functional decline (N=34) or died (N= 7). Univariately, with increasing VES-13 scores, the estimated risk of functional decline/death rose from 23% for subjects with VES=3 to 76% for subjects with VES =10. In multivariable logistic regression, VES-13 scores (Adjusted odds ratio (AOR) = 1.37, 95% confidence interval (CI) =1.18–1.57) and having ≤ high school education (AOR = 2.47, CI=1.08–5.65)) were independent predictors of functional decline/death (area under the receiver operator curve = 0.79).

Conclusion

Among older women with newly diagnosed non-metastatic breast cancer, one in five developed functional decline and/or death within 12 months of breast cancer treatment initiation. Women with ≤ high school education were disproportionately affected. The VES-13 is a useful instrument for early identification of those at risk for functional decline and/or death.

Keywords: Functional, Decline, Older, Women, Breast, Cancer, Low, Socioeconomic, Status

CONDENSED ABSTRACT

Among older women with newly diagnosed non-metastatic breast cancer, functional decline within 12 months of breast cancer treatment was highly prevalent and women of lower educational status were disproportionately affected. The vulnerable Elders Survey was a useful tool for early identification of those at risk for functional decline.

INTRODUCTION

Compared with Non-Hispanic Whites (NHW), African-Americans (AA) are over-burdened with many chronic diseases including functional disability.1–3 Functional disability is the inability to independently complete activities of daily living. Furthermore, functional decline, defined as the transition over time to a more functionally dependent state, disproportionately affects AA and persons of lower socioeconomic status (SES).4, 5

Functional status is a key summary measure of health.6 Functional status predicts many outcomes in older persons, including total mortality,7 mortality among hospitalized patients,8 recovery from intensive care9, and tolerance to cancer treatment.10 Functional disability and decline result in a huge financial burden on the individual and society at large. The added costs of healthcare for the subset of older adults who develop functional decline is estimated at $26 billion per year in the US, just under one tenth of the total cost of healthcare for all persons aged 65 years and older.11, 12 Therefore, the prevention of functional disability and decline could be significant with potential benefits at both the individual and societal level, and could potentially improve overall survival for those particularly at risk.

The Vulnerable Elders Survey is a 13-item self-administered tool that has been validated in community dwelling elders to predict functional decline or death at 12 months.13–15 Using the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey, Saliba, et al14 found that community dwelling elders with a VES-13 score of 3 were four times more likely to develop functional decline and death at 2 years compared to their counterparts who scored <3. These findings were subsequently validated in prospective cohort studies.13, 16 Patients with cancer who were undergoing treatment were excluded from these studies. Therefore it remains unclear if the VES-13 will be useful for predicting functional decline among cancer patients undergoing active treatment and during the early survivorship period where opportunity exists to intervene before functional disability/decline become firmly established.

In light of this existing gap we sought to examine the utility of the VES-13 in predicting functional decline among older women with newly diagnosed non-metastatic breast cancer. This information is clinically relevant for cancer treatment-decision making and for informing interventions aimed at preventing functional decline among older breast cancer survivors.

PATIENTS and METHODS

Study Design and Patient Population

This is a longitudinal study of patients ≥ 65 years with newly diagnosed histologically confirmed stage I–III breast cancer who were recruited from ambulatory oncology clinics at an academic center between April 1, 2008 and April 31, 2013. Exclusionary criteria included receipt of chemotherapy, hormonal or targeted therapy or breast irradiation prior to enrollment for the current diagnosis of breast cancer. Receipt of breast surgery before enrollment was allowed. AA were over sampled. Our rationale for oversampling AA was based on existing literature from the general population showing that AA were more likely to suffer from many chronic diseases including functional disability. We had to oversample and enroll an adequate number of AA to allow us to examine for racial differences in functional outcomes. For that reason we decided a priori to enroll at least 30% AA, and therefore enrolled one AA for every two NHWs. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Study Procedures and Data Collection

Potentially eligible patients were identified from weekly multi-disciplinary breast cancer conferences and then approached for informed consent by a trained research assistant during patients’ initial visit with a medical or radiation oncologist. A Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) which included a functional assessment was completed by consenting patients at baseline, six and 12 months from study enrollment.

Measures

Functional Assessment

The VES-13 asks older patients to report their age by three categories (65–74, 75–84, ≥ 85years); self-rated health (excellent, very good, good, fair, poor); functional limitations (1. stooping, crouching or kneeling; 2. lifting or carrying heavy objects; 3. writing or grasping small objects; 4. walking a quarter of a mile; 5. doing heavy housework); and functional disabilities (1. shopping for personal items; 2. managing money; 3. walking across a room; 4. doing light housework; 5. bathing or showering).13–15 The maximum score is 10 and increasing scores denote increasing risk of functional decline.

The Katz Activities of Daily Living (ADLs), and the Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADLs) were used to evaluate self-reported functional status at baseline, 6 and 12 months. ADLs are skills necessary to live independently at home such as bathing, transferring, and dressing17 and IADLs are skills required for living independently in the community such as using the telephone, managing medications, housekeeping, transportation, ability to manage finances, and preparing meals.18 The maximum score for ADLs and IADLs is 6 and 8 respectively, with increasing scores denoting better functional status.

Comorbidities

Medical records were abstracted to obtain data on comorbidities at baseline. This data was supplemented with self-report of medical problems by participants. Using the list of comorbidities we derived the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI)19 score, based on the presence of eighteen medical conditions.

Socio-demographic and Other Variables

Socio-demographic variables were captured at baseline using a self-administered questionnaire. Data on median household income was obtained from United States Census Bureau website20 using participants’ zip codes from their place of residence at the time of enrollment. Height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm and weight measured to the nearest 0.01kg to compute Body Mass Index (BMI). Medical records were abstracted to obtain data on tumor characteristics and cancer treatments received.

Analytic Variables

Primary outcome variable

The primary outcome was a composite outcome of functional decline and death within 12 months of study enrollment. Functional decline was defined as a decrease in at least one point on the ADL and/or IADL scales from baseline to 12 months, Yes or No.21, 22 Death was considered the most extreme manifestation of functional decline and hence the rational for its inclusion in the outcome.22 Death status was determined using institution tumor registry records.

Functional status, which is measured by an individual’s ability to perform ADL/IADLs, is a key summary measure of the health status of individuals.6 A deterioration in functional status (a decrease in ADLs and/or IADLs score) is a well-established approach for capturing and defining functional decline and hence the rationale for our approach.

Independent variable

The independent variable was VES-13 scores at baseline analyzed as a continuous variable.

Explanatory variables

Explanatory variables included age (65–74, ≥ 75 years); race (AA, NHW); marital status (married, other); educational status (≤ high school, > high school); median household income dichotomized as <$35,000 (lowest quartile) vs. ≥$35,000; living situation (alone, other); health insurance carrier (Medicare, other); body mass index [BMI] (<25kg/m2, ≥ 25kg/m2); stage (I–II, III); receipt of chemotherapy (Yes or No); receipt of hormone therapy (Yes or No); and comorbidity [CCI score (0–1, ≥ 2)].

Data Analysis

We excluded from the analyses participants who did not complete follow-up despite the fact that they had not died (N=22). We compared participants’ baseline characteristics between the two groups (functional decline/death vs. no functional decline/death) using independent t-tests for continuous variables and Chi-square/Fisher exact tests for categorical variables. We also examined differences in VES-13, ADL/IADL scores between groups using Kruskal-Wallis test. Using univariate logistic regression with functional decline/death (Yes vs. No) as an outcome variable we identified explanatory variables that had univariate associations with functional decline/death (p < 0.10). Our final model used a backward multiple logistic regression method using the same outcome variable and explanatory variables from the univariate logistic regression analysis that were associated with functional decline/death, Because of co-linearity between baseline VES-13 scores and ADL/IADL scores, we did not include baseline ADL/IADL scores in regression models. Interaction between variables in the final model were examined. We conducted the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) for the final model using the estimated area under the ROC curve (AUC). Ordinal logistic regression was used to obtain the probabilities of death, and of death or functional decline according to VES-13 scores.

Sensitivity analysis were conducted with functional decline only as an outcome. We did not examine death only as an outcome because the number of deaths was only seven.

All P values presented are two-sided. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

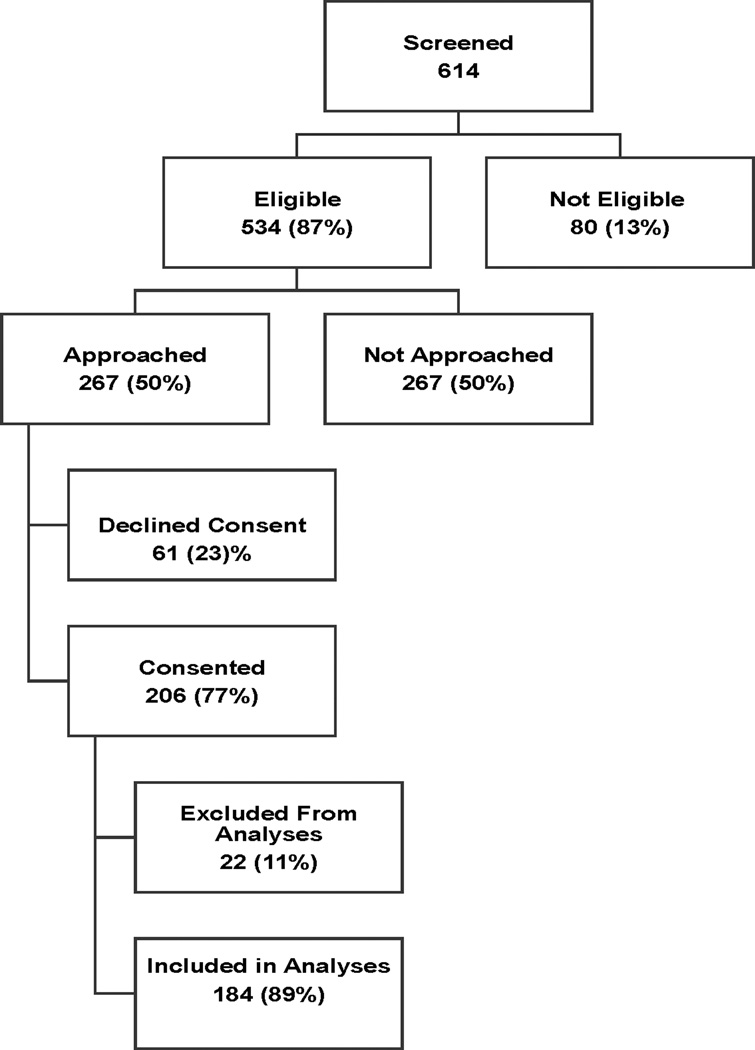

The study flow chart is depicted in Figure 1. Of 614 patients ≥ 65 years, who were screened for study participation, we identified 534 (87%) as being potentially eligible and approached 267 (50%) for informed consent. Of those approached, 206 (77%) agreed to study participation and 61 (23%) declined study participation. The only patient factor that was significantly different between those who were approached for consent and those who were not was race, with AA being more likely to be approached for consent compared with NHW, (65% vs. 44%, p=0.0005). This is because our strategy was to oversample AA. Among patients who were approached, there was no statistical significant difference between consenters and non-consenters by race [AAs vs. NHW, (27% vs. 33%, p=0.40)] or by age group [<75 vs. ≥ 75 years, (28% vs. 34%, p=0.40).

Figure 1.

Patient Flow Chart

Reasons why approximately 50% of potentially eligible patients were not approached included; ineligibility (39%), inability to reach patient due to location of ambulatory clinic being more than a twenty mile radius from the main academic center and/or occurrence of simultaneous office visits by multiple patients at same time at different location (42%), physician request not to approach patient (3%), medical illnesses precluding study participation (6%) and failure to follow-up with medical or radiation oncologist after primary breast surgery (10%).

Of 206 patients enrolled, 22 patients (11%) did not complete follow-up assessments at 12 months, (withdrew N=7 and lost to follow-up N=15), and were excluded from these analyses. Compared to participants with no loss to follow-up, participants with loss to follow-up were less likely to be married (14% vs. 38%, p=0.05) and to have received chemotherapy (5% vs. 26%, p=0.05).

Participants’ Baseline Characteristics

The median duration from diagnosis to baseline assessment was 2.1 months (interquartile range (1.2–3.0 months). The median duration of follow-up was 12.1 months (interquartile range (11.6–12.7 months). The cohort had a mean age of 74.9 years (range 65–93 years), mean baseline VES-13 score of 2.3, SD 2.7, 25% had ADL disability, 31% had IADL disability, 33% were AA, and 44% had ≤ high school education.

Participants’ Baseline Characteristics According to Functional Decline/Death Status

Table 1 displays baseline characteristics by functional decline/death. Twenty-two percent of participants (41) developed functional decline (34) or died (7) and 143 subjects had no functional decline/death. With regards to the trajectory of functional status 19%, 67% and 14% of participants declined, remained stable or improved in functional status, respectively, from baseline to 12 months. The mean baseline VES-13 scores for participants who developed versus those who did not develop functional decline/death was 4.4 (SD 3.2) vs. 1.7 (SD 2.1), p<0.0001, respectively. Additionally, in comparison with participants who did not develop functional decline/death, participants who did were more likely have lower baseline ADL scores (5.0 vs. 5.8, p <0.0001), lower IADL scores (5.8 vs. 7.6, p <0.0001); to be AA (49% vs. 29%, p=0.02); and to have ≤ high school education (71% vs. 36%, p=0.0001).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics by Functional Decline/Death

| Functional Decline/Death | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | No | Yes | p-value* |

| N (%) | (N (%) | ||

| 143 (78) | 41(22) | ||

| Age Group | |||

| 65 – 74 | 85 (59.4) | 14 (34.1) | 0.0047 |

| ≥ 75 | 58 (40.6) | 27 (65.9) | |

| Race | |||

| White | 102 (71.3) | 21 (51.2) | 0.0232 |

| Other | 41 (28.7) | 20 (48.8) | |

| Educational Status | |||

| ≤ High School | 51 (36.2) | 29 (70.7) | 0.0001 |

| > High School | 90 (63.8) | 12 (29.2) | |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married | 60 (42.3) | 9 (21.9) | 0.0184 |

| Other | 82 (57.8) | 32 (78.1) | |

| MH Income | |||

| < 35,000 | 28 (20.1) | 15 (36.6) | 0.0377 |

| ≥ 35,000 | 111 (79.9) | 26 (63.4) | |

| Health Insurance | |||

| Medicare | 125 (88.7) | 35 (85.4) | 0.5894 |

| Other | 16 (11.3) | 6 (14.6) | |

| Living Situation | |||

| Lives Alone | 56 (39.7) | 20 (48.8) | 0.3687 |

| Other | 85 (60.3) | 21 (51.2) | |

| Employment | |||

| Employed | 14 (9.9) | 3 (7.3) | 0.7666 |

| Other | 127 (90.1) | 38 (92.7) | |

| Weight | |||

| Under/Normal Weight | 40 (28.0) | 7 (17.1) | 0.2224 |

| Over weight/Obese | 103 (72.0) | 34 (82.9) | |

| Charlson’s Comorbidity Index | |||

| 0 – 1 | 113 (79.0) | 26 (63.4) | 0.0620 |

| ≥ 2 | 30 (21.0) | 15 (36.6) | |

| Stage at Diagnosis | |||

| I–II | 128 (90.8) | 30 (73.2) | 0.0070 |

| III | 13 (9.2) | 11 (26.8) | |

| Receipt of Chemotherapy | |||

| No | 99 (71.7) | 33 (82.5) | 0.2196 |

| Yes | 39 (28.3) | 7 (17.5) | |

| Receipt of Hormonal Therapy | |||

| No | 23 (17.0) | 9 (22.5) | 0.4858 |

| Yes | 112 (83.0) | 31 (77.5) | |

| Type of Surgery | |||

| Mastectomy | 42 (30.43) | 14 (35.90) | 0.0258 |

| Lumpectomy | 92 (66.67) | 20 (51.28) | |

| None | 4 (2.90) | 5 (12.82) | |

| Lymph Node Dissection | |||

| No | 19 (13.57) | 9 (23.08) | 0.2102 |

| Yes | 121 (86.43) | 30 (76.92) | |

| Receipt of Radiation Therapy | |||

| No | 65 (48.87) | 24 (61.54) | 0.2028 |

| Yes | 68 (51.13) | 15 (38.46) | |

| Receipt Biological Therapy | |||

| No | 116 (84.06) | 32 (80.00) | 0.6315 |

| Yes | 22 (15.94) | 8 (20.00) | |

| Receipt of Neoadjuvant Therapy | |||

| No | 110 (78.57) | 29 (70.73) | 0.2996 |

| Yes | 30 (21.43) | 12 (29.27) | |

Predictors of Functional Decline or Death at 12 months

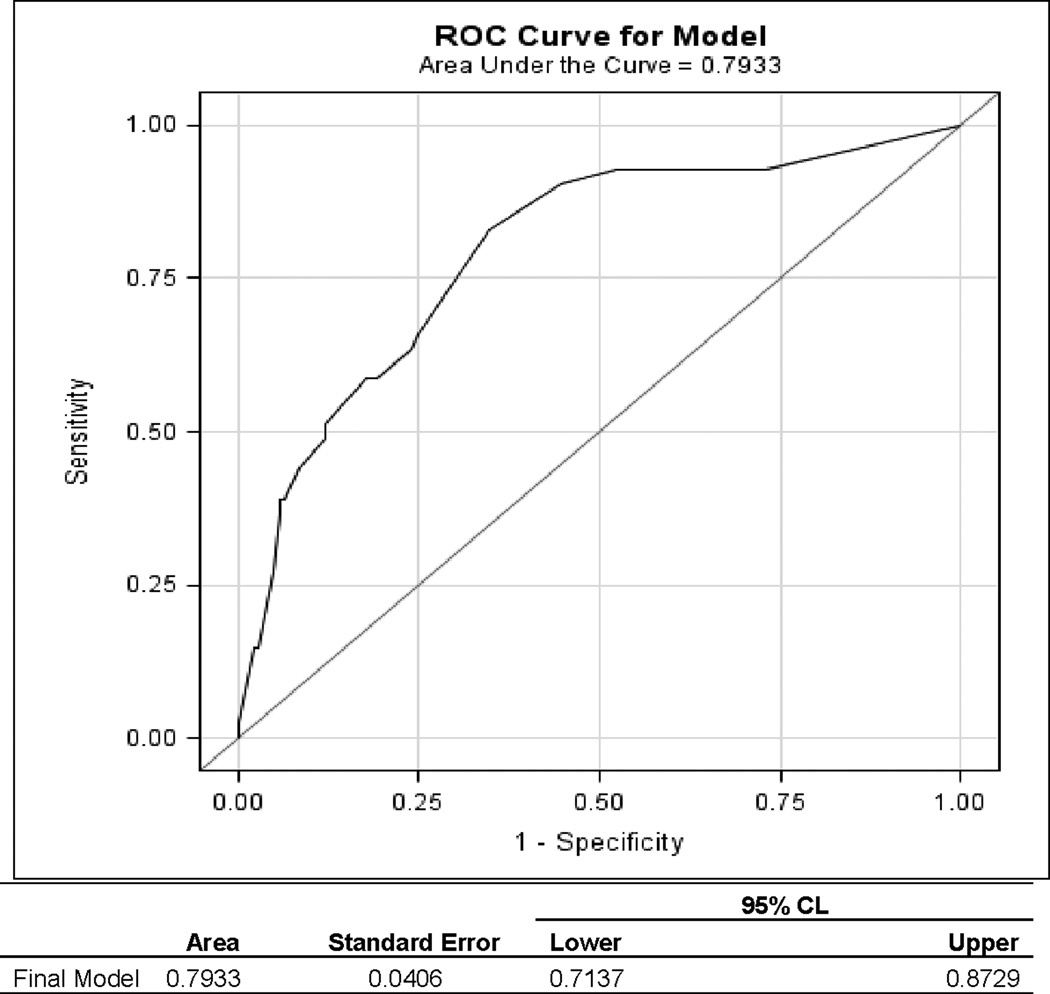

Using univariate logistic regression with functional decline/death (Yes vs. No) as an outcome variable, we found that nine explanatory variables (baseline VES-13, age, race, education, marital status, median household income, Charlson Comorbidity Index, stage and surgery) had univariate associations with the functional decline/death (p < 0.10), see Table 2. Using backward multiple logistic regression with the same outcome and the eight explanatory variables from the univariate logistic regression analysis, we found that baseline VES-13 and educational status were the only significant independent predictors of functional decline/death at 12 months, (Table 3). The odds of functional decline/death were multiplied by 1.37 for each one-point increase in VES-13 score, (AOR = 1.37, 95% CI=1.18–1.57), and participants with ≤ high school education vs. those with > high school education had 2.5 times higher odds of developing functional decline/death, (AOR = 2.47, 95% CI=1.08–5.65). The area under the ROC was 0.79, 95% CI=0.71–0.87, see Figure 2.

Table 2.

Univariate Logistic Regression with 12-Month Functional Decline/Death

| Variable | Reference Group | Odds (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| VES Scores at baseline | 1.433 (1.252, 1.641) | <.0001 | |

| Age | 1.130 (1.069, 1.194) | <.0001 | |

| Race: African-American | White | 2.369 (1.163, 4.827) | 0.0175 |

| Education: ≤ High school | > High school | 4.265 (2.004, 9.077) | 0.0002 |

| Marital Status: Other | Married | 2.602 (1.156, 5.854) | 0.0209 |

| Median Household Income (per 1000) | 0.979 (0.961, 0.997) | 0.0199 | |

| Living Situation: Alone | Other | 1.446 (0.718, 2.909) | 0.3015 |

| Employment: Employed | Other | 0.753 (0.207, 2.735) | 0.6661 |

| Health Insurance: Medicare | Other | 0.747 (0.272, 2.051) | 0.5708 |

| Weight: Overweight/Obese | Underweight/Normal | 1.886 (0.773, 4.601) | 0.1631 |

| Charlson’s Comorbidity Index: ≥ 2 | < 2 | 2.173 (1.024, 4.611) | 0.0432 |

| Stage: III | I – II | 3.609 (1.473, 8.842) | 0.0050 |

| Chemotherapy: Yes | No | 0.538 (0.220, 1.319) | 0.1756 |

| Hormonal Therapy: Yes | No | 0.707 (0.297, 1.683) | 0.4338 |

| Type of Surgery: Lumpectomy | Mastectomy | 0.652 (0.301, 1.415) | 0.2793 |

| None | Mastectomy | 3.750 (0.882, 15.942) | 0.0735 |

| Lymph Node Dissection: Yes | No | 0.523 (0.215, 1.272) | 0.1531 |

| Radiation Therapy: Yes | No | 0.597 (0.288, 1.239) | 0.1663 |

| Biological Therapy: Yes | No | 1.318 (0.537, 3.239) | 0.5469 |

| Neoadjuvant Therapy: Yes | No | 1.517 (0.692, 3.325) | 0.2975 |

Table 3.

Results of Multiple Logistic Regression with Backward Selection Method Showing Independent Predictors of Functional Decline/Death

| Variable | Estimate | OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| VES-13 | 0.311 | 1.365 (1.184, 1.573) | <.0001 |

| Education: ≤ High school | 0.4513 | 2.466 (1.077, 5.648) | 0.0328 |

Figure 2.

Receiver Operator Operating Characteristic Curve (ROC) for functional decline using the estimated area under the ROC curve (AUC).

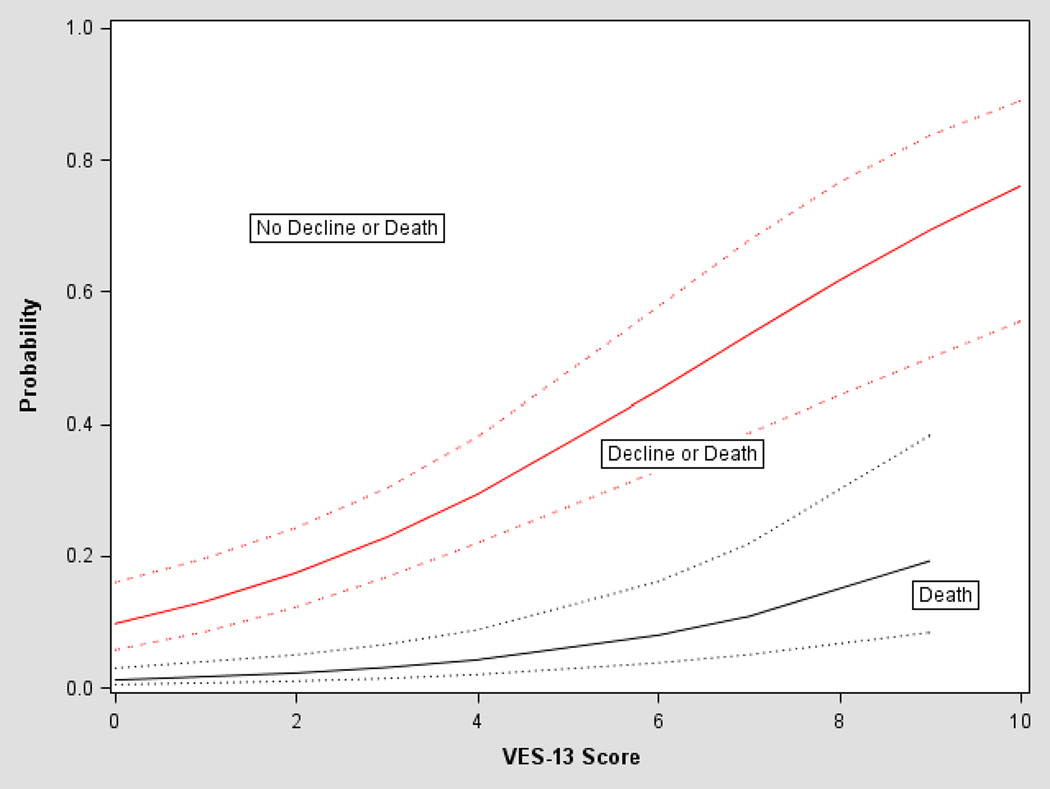

The univariate association between VES-13 scores and predicted probability of death, and of death or functional decline over the 12 month follow-up period, estimated from the ordinal logistic regression, are depicted in Figure 3. For participants with a VES-13 score of 3 the predicted probabilities of death, and of death or functional decline in the next 12 months were 0.04 and 0.23, respectively. With increasing scores, probabilities increased such that at a VES score of 10, the predicted probabilities of death, and of functional decline or death in the next 12 months were 0.24 and 0.76, respectively.

Figure 3.

Probabilities of death, and of death or functional decline according to VES-13 scores

Multivariable analyses with functional decline only as the outcome of interest showed similar results, data not shown. The odds of functional decline versus none were multiplied by 1.43 for each one-point increase in VES-13 score, (OR = 1.43, 95% CI=1.24–1.64). The area under the ROC was 0.75, 95% CI=0.65–0.85. Educational status was no longer significantly associated with functional decline at 12 months (p=0.10) and VES-13 remained the only independent significant predictor of functional decline.

DISCUSSION

Among older women with stage I–III newly diagnosed breast cancer one in five developed functional decline/death within 12 months of initiating treatment for breast cancer. The VES-13 was a useful instrument for predicting functional decline. Notably, the study identified VES-13 scores and educational status as the only independent predictive factors associated with functional decline/death within 12 months of treatment initiation.

The VES-13 is a well-established instrument and has been validated among older adults in general as a useful instrument for predicting functional decline and death. Our study extends the utility of the VES-13 survey to newly diagnosed older breast cancer patients undergoing active treatment for cancer, a population that was excluded in prior validation studies. It is remarkable that the magnitude of the predictive properties of the VES-13 found in our study were nearly identical to results found by Min et al13, 16 in their validation studies among the general older adult population. This attests to the validity of the VES-13 in predicting functional decline irrespective of the patient population. Several small studies and a few large studies have also examined the utility of the VES-13 in the geriatric oncology population for its utility to screen and identify patients who will benefit from a full CGA, or to completely replace the need for a CGA.23–25 Consistently, these studies have demonstrated that the VES-13 is not a perfect screening instrument nor can it substitute for the CGA. This is not surprising given that the VES-13 was never developed nor was it validated to replace the CGA. Used as intended and developed, it is a robust and consistent instrument for predicting functional decline and death, irrespective of patient population. Given the importance of functional status in predicting cancer treatment tolerance, and based on results from emerging studies26, it is conceivable that the VES-13 might serve as a useful instrument for predicting chemotherapy toxicity and tolerance to cancer treatment.

The significant association between SES and functional decline found in our study deserves comment. This finding is consistent with existing literature which has demonstrated racial and SES-related disparities in functional and health status in the United States with racial minorities and persons with lower SES persistently exhibiting poorer health status, and higher rates of functional disability/decline, and mortality.1, 4, 5 Our recent work which evaluated the baseline cross-sectional relationship between patient characteristics and functional status in older women with breast cancer and published in Cancer in 201327, demonstrated that compared with NHW, AA were four times more likely to have functional disability at initial diagnosis of breast cancer. Lower SES explained 59 percent of the racial disparity in functional disability at diagnosis. Specifically in that study, older women with newly diagnosed non-metastatic breast cancer who had ≤ high school education or had a median household income of <$35,000.00 were 3.5 and 2.5 times more likely, respectively, to have functional disability at initial diagnosis of breast cancer. In the current study we extend our findings by demonstrating that SES-related disparities in functional status persist with longitudinal follow-up and that once again socioeconomic differences account for disparities in functional decline.

Breast cancer survival rates among older AA women continue to lag behind that of older NHW.28 A recent SEER-Medicare database analysis of >28,000 older women with breast cancer suggests that the racial disparity in breast cancer survival among older women is partly due to the poorer health status of older AA (vs. NHW) at breast cancer diagnosis.29 This poorer health status is hypothesized to blunt the long-term survival benefit derived from cancer treatment.29 It is unfortunate but not surprising that once again older AA and women of lower SES are disproportionately affected by functional disability and decline, a key summary measure of health.6 This speaks to the general poor health of these two patient populations and may partly explain the poorer breast cancer outcomes experienced by AA and women of lower SES. It is therefore imperative for efforts to be developed and focused on improving the functional health of at risk populations, otherwise racial and SES-related disparities will only widen. Such efforts in the long-term may improve treatment tolerance, functional and overall health, ultimately translating to improved breast cancer survival for older AA and women of lower SES.

Many studies have demonstrated the benefits of increased physical activity. Specifically, older adults engaged in 150 minutes of moderate intensity aerobic exercise per week, as recommended by the US Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS),30 can reduce the risk of functional limitations by up to 50%.31 In addition, regular physical activity after breast cancer diagnosis is associated with improved breast cancer-specific and overall survival32, 33. A meta-analysis of more than 12,000 women with breast cancer showed that post-diagnosis physical activity reduced breast cancer mortality by 34% and all-cause mortality by 41%.34 Despite these and many other health benefits, only about 50% of Americans engage in the recommended amount of physical activity.35 Rates of physical inactivity are particularly high among older AA breast cancer survivors36, 37, the very population disproportionately affected by obesity, functional disability/decline. Promotion of healthy behaviors is therefore critical to addressing health disparities among these populations.38 Physical activity studies involving older AA and lower SES breast cancer survivors, two groups that are particularly vulnerable to functional disability/decline39, 40 are lacking, have been identified as a critical research need,41 and are therefore warranted.

Our study had several limitations. The cohort was enrolled from a single academic institution. Therefore results may not be generalizable. However, the consistency of our results with the original VES-13 validation studies suggests otherwise. Deaths were ascertained from tumor registry rather than from a more centralized database such as the National Death Index. However, because this was a single institution study we were able to rely on tumor registry results. Duration of treatment and recurrences though rare in the first year of diagnosis, could have an impact on functional status. However, our study did not accounted for treatment duration or recurrences in our analysis. Despite these limitations, are results are consistent with existing literature suggesting that our results are robust.

In conclusion, among older women with newly diagnosed stage I–III breast cancer, one in five developed functional decline/death within 12 months of treatment initiation. Women with ≤ high school education were disproportionately affected. The VES-13 is a useful instrument for early identification of those at risk for functional decline/death among older women with breast cancer. Use of the VES-13, a patient self-administered instrument that takes only 4 minutes to complete should be encouraged for early identification of those at risk. Behavioral research and efforts to ameliorate functional disability and decline among older women with breast cancer are warranted for all but in particularly for older African-American and women of lower socio-economic status. Such efforts may in the long-term translate to improved treatment tolerance and better breast cancer outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by a Susan Komen Breast Cancer Foundation Career Catalyst in Disparities Research Grant (KG100319) and 1R01MD009699-01 to Cynthia Owusu, M.D.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception/Design: Cynthia Owusu, Mark Schluchter

Provision of study material or patients: Cynthia Owusu

Collection and/or assembly of data: Cynthia Owusu

Data analysis and interpretation: Cynthia Owusu, Seunghee Margevicius, Mark Schluchter, Siran M. Koroukian, Kathryn H. Schmitz, Nathan A. Berger

Manuscript writing: Cynthia Owusu, Seunghee Margevicius, Mark Schluchter, Siran M. Koroukian, Kathryn H. Schmitz, Nathan A. Berger

Final approval of manuscript: Cynthia Owusu, Seunghee Margevicius, Mark Schluchter, Siran M. Koroukian, Kathryn H. Schmitz, Nathan A. Berger

None of the authors have any financial disclosures or conflicts of interests to report.

References

- 1.Hummer R, Benjamin M, Rogers R. Race/ethnic disparities in health and mortality among the elderly: A documentation and examination of social factors. In: Anderson N, Bulato B, Cohen B, editors. Critical perspectives on racial and ethnic differences in health in later life. Washington DC: National Research Council; 2004. pp. 53–94. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thorpe RJ, Jr, Kasper JD, Szanton SL, Frick KD, Fried LP, Simonsick EM. Relationship of race and poverty to lower extremity function and decline: findings from the Women's Health and Aging Study. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66:811–821. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thorpe RJ, Jr, Koster A, Bosma H, et al. Racial differences in mortality in older adults: factors beyond socioeconomic status. Ann Behav Med. 43:29–38. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9335-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller DK, Wolinsky FD, Malmstrom TK, Andresen EM, Miller JP. Inner city, middle-aged African Americans have excess frank and subclinical disability. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:207–212. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coppin AK, Ferrucci L, Lauretani F, et al. Low socioeconomic status and disability in old age: evidence from the InChianti study for the mediating role of physiological impairments. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61:86–91. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fried TR, Bradley EH, Williams CS, Tinetti ME. Functional disability and health care expenditures for older persons. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:2602–2607. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.21.2602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolinsky FD, Callahan CM, Fitzgerald JF, Johnson RJ. Changes in functional status and the risks of subsequent nursing home placement and death. J Gerontol. 1993;48:S94–S101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inouye SK, Peduzzi PN, Robison JT, Hughes JS, Horwitz RI, Concato J. Importance of functional measures in predicting mortality among older hospitalized patients. Jama. 1998;279:1187–1193. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.15.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mayer-Oakes SA, Oye RK, Leake B. Predictors of mortality in older patients following medical intensive care: the importance of functional status. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39:862–868. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb04452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buccheri G, Ferrigno D, Tamburini M. Karnofsky and ECOG performance status scoring in lung cancer: a prospective, longitudinal study of 536 patients from a single institution. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A:1135–1141. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(95)00664-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guralnik JM, Alecxih L, Branch LG, Wiener JM. Medical and long-term care costs when older persons become more dependent. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1244–1245. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.8.1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reuben DB, Seeman TE, Keeler E, et al. The effect of self-reported and performance-based functional impairment on future hospital costs of community-dwelling older persons. Gerontologist. 2004;44:401–407. doi: 10.1093/geront/44.3.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Min LC, Elliott MN, Wenger NS, Saliba D. Higher vulnerable elders survey scores predict death and functional decline in vulnerable older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:507–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saliba D, Orlando M, Wenger NS, Hays RD, Rubenstein LZ. Identifying a short functional disability screen for older persons. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55:M750–M756. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.12.m750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higashi T, Shekelle PG, Adams JL, et al. Quality of care is associated with survival in vulnerable older patients. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:274–281. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-4-200508160-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Min L, Yoon W, Mariano J, et al. The Vulnerable Elders-13 Survey Predicts 5-Year Functional Decline and Mortality Outcomes in Older Ambulatory Care Patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02497.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies Of Illness In The Aged. The Index Of Adl: A Standardized Measure Of Biological And Psychosocial Function. Jama. 1963;185:914–919. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lawton MP. Scales to measure competence in everyday activities. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1988;24:609–614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.U.S Census Bureau. State and national population projections. [Accessed February 2013]; http://www.census.gov/population/projections/data/national/2012.html.

- 21.Min LC, Wenger NS, Reuben DB, Saliba D. A short functional survey is responsive to changes in functional status in vulnerable older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1932–1936. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01921.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suijker JJ, Buurman BM, van Rijn M, et al. A simple validated questionnaire predicted functional decline in community-dwelling older persons: prospective cohort studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:1121–1130. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luciani A, Ascione G, Bertuzzi C, et al. Detecting Disabilities in Older Patients With Cancer: Comparison Between Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment and Vulnerable Elders Survey-13. J Clin Oncol. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.9978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Owusu C, Koroukian SM, Schluchter M, Bakaki P, Berger NA. Screening older cancer patients for a Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment: A comparison of three instruments. J Geriatr Oncol. 2011;2:121–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Decoster L, Van Puyvelde K, Mohile S, et al. Screening tools for multidimensional health problems warranting a geriatric assessment in older cancer patients: an update on SIOG recommendations dagger. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:288–300. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luciani A, Biganzoli L, Colloca G, et al. Estimating the risk of chemotherapy toxicity in older patients with cancer: The role of the Vulnerable Elders Survey-13 (VES-13) J Geriatr Oncol. 2015;6:272–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Owusu C, Schluchrer MD, Kouroukian SM, Mazhuvancherry S, Berger NA. Racial Disparities in Functional Disability among Older Women with Newly Diagnosed Non-metastatic Breast Cancer. Cancer. 2013 doi: 10.1002/cncr.28232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith BD, Jiang J, McLaughlin SS, et al. Improvement in breast cancer outcomes over time: are older women missing out? J Clin Oncol. 29:4647–4653. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.8408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silber JH, Rosenbaum PR, Clark AS, et al. Characteristics associated with differences in survival among black and white women with breast cancer. Jama. 310:389–397. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.8272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Visser M, Simonsick EM, Colbert LH, et al. Type and intensity of activity and risk of mobility limitation: the mediating role of muscle parameters. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:762–770. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ballard-Barbash R, Friedenreich CM, Courneya KS, Siddiqi SM, McTiernan A, Alfano CM. Physical activity, biomarkers, and disease outcomes in cancer survivors: a systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 104:815–840. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Irwin ML, McTiernan A, Manson JE, et al. Physical activity and survival in postmenopausal women with breast cancer: results from the women's health initiative. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2011;4:522–529. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ibrahim EM, Al-Homaidh A. Physical activity and survival after breast cancer diagnosis: meta-analysis of published studies. Med Oncol. 28:753–765. doi: 10.1007/s12032-010-9536-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adult participation in aerobic and muscle-strengthening physical activities--United States, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 62:326–330. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Last accessed 09/23/2013]; http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/PASurveillance/DemoCompareResultV.asp#result.

- 37.Hair BY, Hayes S, Tse CK, Bell MB, Olshan AF. Racial differences in physical activity among breast cancer survivors: Implications for breast cancer care. Cancer. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Satcher DM. The Covenant with Black America. Chicago: The Third World Press; 2006. Securing the Right to Healthcare and Well-Being. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fuller-Thomson E, Nuru-Jeter A, Minkler M, Guralnik JM. Black-White disparities in disability among older Americans: further untangling the role of race and socioeconomic status. J Aging Health. 2009;21:677–698. doi: 10.1177/0898264309338296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Minkler M, Fuller-Thomson E, Guralnik JM. Gradient of disability across the socioeconomic spectrum in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:695–703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa044316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schmitz KH, Courneya KS, Matthews C, et al. American College of Sports Medicine roundtable on exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 42:1409–1426. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181e0c112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]