Abstract

Patient: Female, 74

Final Diagnosis: Toxic epidermal necrolysis

Symptoms: Bullous hemorrhagic lesions

Medication: Levoflaxosine

Clinical Procedure: Omalizumab therapy

Specialty: Allergology

Objective:

Rare disease

Background:

Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) is characterized by widespread erythematous and bullous lesions on the skin. Nowadays, considerable progress has been made in the understanding of its pathogenesis. Immunologically it is similar to graft-versus-host disease. Therefore, we may propose that TEN is a disorder of cell-mediated immunity.

Case Report:

Our patient was a 74-year-old white female who had pneumonia and was positive for hepatitis C virus (HCV), and who had been on levofloxacin therapy. After the first levofloxacin dose, erythematous dusky red macules occurred on her extremities and trunk, and on the following day, confluent purpuric lesions tended to run together over 85% of her body. Her biopsy results indicated TEN. Laboratory testing for serum ECP (eosinophil cationic peptide) and serum immunoglobulin (Ig) levels were performed, and blister fluid was investigated. The patient responded positively to omalizumab treatment and after treatment laboratory tests revealed decreased high sensitive CRP, ECP, IgG1, IgG2, IgG3, IgG4, IgA, and IgM levels.

Conclusions:

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of a patient with HCV who developed cutaneous adverse drug reaction on levofloxacin medication and recovered with omalizumab treatment. This is the first documentation of omalizumab treatment of a TEN patient.

MeSH Keywords: Bronchopneumonia, Levofloxacin, Stevens-Johnson Syndrome

Background

Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) are severe, although uncommon, cutaneous reactions that are usually related to the use of medication. They are associated with significant morbidity and mortality. TEN and SJS differ in the proportion of the body surface area involved. SCORTEN is a scoring system used to predict mortality in TEN patients. If the SCORTEN index is 5 or more, the mortality rate is expected to be more than 90%. The pathogenic process of TEN mostly involves apoptosis [1,2] with some necrosis [3]. Nowadays, considerable progress has been made in the understanding of the pathogenesis of TEN. Its immunological characteristics are similar to graft versus host disease. It is therefore possible to say that TEN is a disorder of cell-mediated immunity [4,5].

The clinical benefits of omalizumab against urticaria and asthma have been established in several large clinical trials [6–9]. The last two decades have provided interesting and conceptually new therapies for allergic asthma and idiopathic urticaria, among them, anti-IgE therapies such as omalizumab have been identified as important treatment options. It has been suggested that mast cells residing in the mucosal membranes like nasal mucosa and mast cells residing in the skin are different in terms of tryptase and chymase content, sensitivity to stimuli, receptor regulation, and cell life span [10,11]. A better understanding of this process is needed. Here, we report the treatment of a patient with toxic skin necrolysis or TEN, which occurred after one dose of levofloxacin, which was then successfully treated with pulse prednisolone and an anti-IgE monoclonal antibody omalizumab. In this case study, we examined the immunoglobulin (Ig) levels of serum in our patient before and after treated with omalizumab, to explore their relationship with disease activity and the impact of omalizumab therapy on Ig levels. We report here, for the first time, the clinical and laboratory results of a TEN patient who was treated with omalizumab successfully. The study was approved by the ethical committee at Antalya Training and Research Hospital. The patient gave informed consent.

Case Report

A 74-year-old white female patient was diagnosed with pneumonia and hospitalized. Her prior medical history was noteworthy for diabetes mellitus and HCV(+). Upon physical examination, her body temperature was 37.8°C, heart rate was 112 beats/minute, arterial blood pressure was 135/85 mm Hg, and body mass index (BMI) was 35.65 kg/m2. Her pupillary light reflex was +/+, +/+ and she was disoriented. Levofloxacin treatment of 750 mg/day was administered. Soon after her first levofloxacin dose (at the sixth hour), erythematous dusky red macules occurred on her extremities and trunk. On the following day, confluent purpuric severe lesions appeared over 85% of her body (Figure 1A–1C). Then she developed bilateral palpebral edema with hyperemic conjunctivae. Levofloxacin treatment was stopped and clarithromycin 1 gr/day was initiated. Skin assessment found Nikolsky sign was positive. A skin biopsy was performed and revealed complete necrotic epidermis that was detached from the underlying dermis, which was consistent with TEN (Figure 2). A 5 mL fasting venous blood sample was collected in the morning between 7 and 9 am, centrifuged at 4°C for 20 minutes at 3,000 rpm and subsequently stored at −80°C until analysis of ECP and immunoglobulins was performed. The results are reported as means of duplicate measurements. In the necrotic epidermis, necrotic keratinocytes were seen (Figure 3A, arrow). Direct immunofluorescence testing with IgG, IgA, IgM, and complement 3(C3) revealed only weak granular C3 deposition along the bullous roof as well as the base of the bullae (Figure 3B, arrow). The Severity Score for TEN (SCORTEN) was calculated as 6.

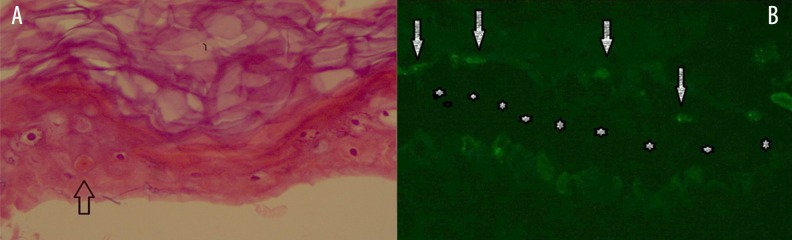

Figure 1.

Erythematous dusky red macules on admission (A, B), flaccid bullae developed on fourth day (C).

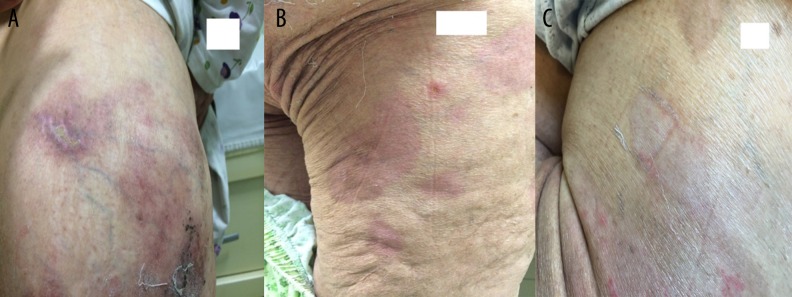

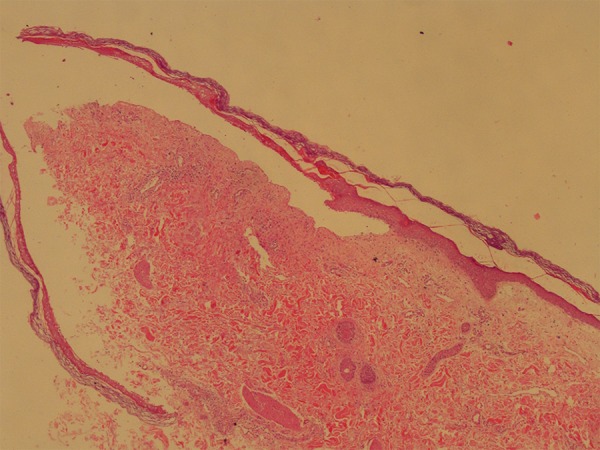

Figure 2.

Completely necrotic epidermis is detached from underlying dermis. Note that bullae cavity is clear, without any inflammatory cells (H&E, ×4).

Figure 3.

In the necrotic epidermis, silhouette of the cells are easily outlined. Note that there is also one necrotic keratinocyte (A, arrow). Direct immunoflouresence testing revealed C3 deposited on the roof and on the dermal base (B, arrow). Stars indicate bullae cavity (A: H&E, ×40 and B: anti-human C3, ×40).

Results

The patient’s biochemical test results on the second day of hospitalization are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical and laboratory findings of the patient.

| Marker | Serum level/(First day of hospitalization) | Second day/pulse steroid | Serum level/ pre-omalizumab | Serum level/post omalizumab 2nd day | Serum level/post omalizumab 2nd week | Normal range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hb (g/dL) | 12.3 | 14.7 | 11.6 | 11.3 | 11.1 | 13.6–17.2 |

| WBC (mm3) | 9000 | 18700 | 13.4 | 10.7 | 9.6 | 4.5–10.3 |

| Blood glucose level (mg/dL) | 348 | 415 | 262 | 121 | 346 | 74–106 |

| Blood urine nitrogen(BUN) (mg/dL) | 21 | 20 | 24 | 21 | 23 | 8–20 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.71 | 0.58 | 0.77 | 0.66–1.09 |

| Serum Ca (mg/dL) | 7.4 | 7.5 | 7.6 | 7.6 | 8.8 | 8.8–10.6 |

| Serum Na (mmol/L) | 128 | 131 | 142 | 142 | 140 | 136–146 |

| ALT (U/L) | 22 | 28 | 38 | 39 | 32 | <50 |

| AST (U/L) | 26 | 32 | 41 | 46 | 39 | <50 |

| GGT (U/L) | 78 | 210 | 289 | 207 | 152 | <38 |

| LDH (U/L) | 204 | 220 | 242 | 280 | 257 | <248 |

| Total protein (g/dL) | 5 | 5.1 | 5.1 | 5.2 | 6.5 | 6.4–8.3 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 2.3 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.6 | 3.4 | 3.5–5.2 |

| High sensitive CRP (mg/L) | 250 | 18 | 12 | 9 | 5 | 0–5 |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (mm/h) | 80 | 54 | 11 | 27 | 30 | 0–20 |

| IgA (mg/dL) | 274 | 296 | 321 | 352 | 380 | 70–400 |

| IgG (mg/dL) | 850 | 856 | 752 | 885 | 1100 | 700–1600 |

| IgM (mg/dL) | 134 | 132 | 129 | 120 | 162 | 40–230 |

| D-Dimer (ng/ml) | 742 | 765 | 546 | 963 | 390 | 0–243 |

| Fibrinojen(mg/dL) | 214 | 375 | 417 | 923 | 368 | 200–393 |

| C3c (g/L) | 0.85 | 0.88 | 0.83 | 1.27 | 1.13 | 0.9–1.8 |

| C4c (g/L) | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.21 | 0.31 | 0.24 | 0.1–0.4 |

| ECP (ng/ml) | 25 | 23 | 21.5 | 14 | 15.7 | 0–24 |

| IgG1 (mg/dL) | 745 | 733 | 630 | 661 | 712 | 528–1384 |

| IgG2 (mg/dL) | 201 | 193 | 158 | 142 | 178 | 147–610 |

| IgG3 (mg/dL) | 74 | 70.8 | 72.8 | 71.4 | 79.1 | 21–152 |

| IgG4 (mg/dL) | 12.4 | 11.6 | 8.24 | 8.24 | 12.2 | 15–202 |

| Marker | Blister fluid level |

|---|---|

| IgE (IU/ml) | 17.8 |

| IgA (mg/dL) | 45.9 |

| IgM (mg/dL) | 16.8 |

| C3c (g/L) | 0.18 |

| C4c (g/L) | 0.06 |

| IgG1 (mg/dL) | 130 |

| IgG2 (mg/dL) | 38.8 |

| IgG3 (mg/dL) | 10.2 |

| IgG4 (mg/dL) | 7.06 |

| ECP (ng/ml) | 195 |

ECP – eosinophilic cationic peptid.

IgG: 856 mg/dL (normal range: 700–1600 mg/dL); IgA: 296 mg/dL (normal range: 70–400 mg/dL); IgM: 132 mg/dL (normal range: 40–230 mg/dL); complement 4: 0.18 g/L (normal range: 0.1–0.4 g/L); IgE: 55.1 IU/L (normal range: 0–100 IU/L); complement 3: 0.88 g/L (normal range: 0.9–1.8 g/L). ANA and RF were negative and hepatitis C markers were positive. Blister fluid and blood sample were tested at the same time for ECP. We found, interestingly, that the ECP level was 8 times higher in the blister fluid than in the blood sample in the pre-omalizumab period.

As part of treatment, fluid and electrolyte homeostasis and skin lesions were managed. Human albumin and methylprednisolone were added to therapy as a 500 mg pulse therapy for three days. On the fifth day, bullous lesions occurred (Figure 1C). Laboratory results are shown in Table 1.

On the sixth day of treatment, omalizumab 300 mg was given. Laboratory results before and after omalizumab treatment are shown in Table 1.

Because of the clinical and symptomatic improvement, antibiotic treatment was stopped on the seventh day of treatment. On the seventeenth day of treatment, the patient was discharged from the hospital (Figure 4A–4C).

Figure 4. (A–C).

Re-epithelialization and pigmentation after omalizumab therapy.

Discussion

Patients with epidermal detachment involving <10% of their body surface area are classified as having SJS, whereas patients with >30% of body surface area affected are classified as having TEN. Both disorders are frequently related to adverse drug reactions (e.g., aminopenicillins, tenoxicam, cephalosporins, quinolones, phenobarbital, phenytoin, cotrimoxazole, carbamazepine, valproic acid), but may occasionally occur after infections (e.g., hepatitis, Yersinia, mycoplasma pneumonia, rubella, herpes simplex, herpes zoster, Escherichia coli) or in association with acute graft-versus-host disease [4,5]. We hypothesized that hepatitis C infection facilitated a drug adverse reaction in our patient and the 8-fold higher ECP level in the blister fluid before omalizumab treatment proved that ECP was related to pathogenesis and the severity of the disease. Higher D-dimer and fibrinogen levels in the active disease period indicated that the coagulation system synchronously was affected as well. This affect has been reported in previous reports [10–13]. For TEN patients with SCORTEN index of 5 or more, the mortality rate is more than 90% [1]. The SCORTEN index of our patient was calculated as 6. In our patient case, there were several important risk factors; advanced age, HCV positive, diabetes, high BMI, increased serum bicarbonate level, increased heart rate, a major surgical intervention which may have impaired the immune system, and widespread skin lesions.

To our knowledge, this case presents the first case of a TEN patient who was successfully treated with omalizumab; it also is the first documentation of the association between anti-IgE therapy and TEN. Our patient responded to omalizumab treatment on the second day; she had decreased high sensitive CRP, ECP, IgA, IgM, IgG1, IgG2, IgG3, IgG4, IgA, and IgM levels.

Conclusions

Optimal treatment modalities need to be clarified for patient scenarios such the one presented here. As a drug therapy protocol, pulse steroid treatment for three days and omalizumab treatment for one day were successfully administered to our patient. Human albumin was used twice to replace lost fluid and to help restore the serum albumin level in our patient. Our successful treatment with omalizumab and prednisolone suggests that combination therapies may be of value. We would like to state that this is the first case to assess ECP in a TEN patient and to evaluate the protein’s relationship with high sensitive CRP, ECP, IgA, IgM, IgG1, IgG2, IgG3, IgG4, and C. We detected a number of significant changes in our case; allergic skin symptoms (erythema and edema) and mucosal symptoms were decreased. We believe that ECP may also have an important role to play in the relationship between TEN and immunologic reactions. Further studies are needed to investigate whether the Th2-mediated inflammation system has a role and an effect of cytokines as markers in TEN.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patient.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest

References:

- 1.Yalcin AD, Karakas AA, Soykam G, et al. A case of toxic epidermal necrolysis with diverse etiologies: successful treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin and pulse prednisolone and effects on sTRAIL and sCD200 levels. Clin Lab. 2013;59(5–6):681–85. doi: 10.7754/clin.lab.2012.120814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yarbrough DR. Experience with toxic epidermal necrolysis treated in a burn center. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1996;17:30–33. doi: 10.1097/00004630-199601000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paquet P, Pierard GE. Toxic epidermal necrolysis: revisiting the tentative link between early apoptosis and late necrosis. Int J Mol Med. 2007;19:3–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roujeau JC, Kelly JP, Naldi L, et al. Medication use and the risk of Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1600–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512143332404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van der Meer JB, Schuttelaar ML, Toth GG, et al. Successful dexamethasone pulse therapy in a toxic epidermal necrolysis(TEN) patient featuring recurrent TEN to oxepam. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26(8):654–56. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2001.00910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yalcin AD. Advances in anti-IgE therapy. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:317465. doi: 10.1155/2015/317465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Normansell R, Walker S, Milan SJ, et al. Omalizumab for asthma in adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(1):CD003559. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003559.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanania NA, Alpan O, Hamilos DL, et al. Omalizumab in severe allergicasthmainadequatelycontrolledwithstandardtherapy: A randomizedtrial. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:573–82. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-9-201105030-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Korn S, Thielen A, Seyfried S, et al. Omalizumab in patientswith severe persistentallergicasthma in a real-life setting in Germany. Respir Med. 2009;103:1725–31. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yalcin AD. A case of netherton syndrome: successful treatment with omalizumab and pulse prednisolone and its effects on cytokines and immunoglobulin levels. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2016;38(2):162–66. doi: 10.3109/08923973.2015.1115518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yalcin AD. An overview of the effects of anti-IgE therapies. Med Sci Monit. 2014;20:1691–99. doi: 10.12659/MSM.890137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yalcin AD, Genc GE, Celik B, Gumuslu S. Anti-IgE monoclonal antibody (omalizumab) is effective in treating bullous pemphigoid and its effects on soluble CD200. Clin Lab. 2014;60(3):523–24. doi: 10.7754/clin.lab.2013.130642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yalcin AD, Celik B, Gumuslu S. D-dimer levels decreased in severe allergic asthma and chronic urticaria patients with the omalizumab treatment. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2014;14(3):283–86. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2014.875525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]