Abstract

Context

Sentinel lymph node biopsy has been established as the new standard of care for axillary staging in most patients with invasive breast carcinoma. Historically, all patients with a positive sentinel lymph node biopsy result underwent axillary lymph node dissection. Recent trials show that axillary lymph node dissection can be safely omitted in women with clinically node negative, T1 or T2 invasive breast cancer treated with breast-conserving surgery and whole-breast radiotherapy. This change in practice also has implications on the pathologic examination and reporting of sentinel lymph nodes.

Objective

To review recent clinical and pathologic studies of sentinel lymph nodes and explore how these findings influence the pathologic evaluation of sentinel lymph nodes.

Data Sources

Sources were published articles from peer-reviewed journals in PubMed (US National Library of Medicine) and published guidelines from the American Joint Committee on Cancer, the Union for International Cancer Control, the American Society of Clinical Oncology, and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

Conclusions

The main goal of sentinel lymph node examination should be to detect all macrometastases (>2 mm). Grossly sectioning sentinel lymph nodes at 2-mm intervals and evaluation of one hematoxylin-eosin–stained section from each block is the preferred method of pathologic evaluation. Axillary lymph node dissection can be safely omitted in clinically node-negative patients with negative sentinel lymph nodes, as well as in a selected group of patients with limited sentinel lymph node involvement. The pathologic features of the primary carcinoma and its sentinel lymph node metastases contribute to estimate the extent of non–sentinel lymph node involvement. This information is important to decide on further axillary treatment.

Axillary lymph node (ALN) status is an important prognostic factor and determinant of treatment for patients with breast carcinoma. For decades, ALN dissection (ALND) was the only procedure used for staging ALNs in women with invasive breast carcinoma.1 Axillary lymph node dissection, however, is associated with significant morbidity, including long-term complications such as limitation of shoulder movements, paresthesias and arm numbness, and lymphedema, which can have a significant impact on the patient's quality of life.2–5 Management of the axilla in patients with breast carcinoma has evolved rapidly in recent years, and an increasingly conservative approach to axillary staging has been developed. Sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy was implemented as an alternative procedure in order to minimize the negative impact of axillary surgery. An SLN is the first lymph node draining a tumor bed, and as such it constitutes the first site of lymph node (LN) involvement. Today, patients with breast carcinoma have smaller tumors and lower nodal disease burden compared with historical series, and most are treated with adjuvant systemic therapy, which is now recognized as improving local as well as systemic control.6 Clinical trials have proven that SLN is equivalent to staging of the axilla in patients with clinically node-negative (cN0) disease.7–12 In addition, recent trials show that ALND may be safely omitted in selected cN0 patients with metastatic carcinomas limited to one or two SLNs,13,14 and have significantly changed clinical practice, with implications for how pathologists examine and report on SLNs.

ALN Staging

The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) and the Union for International Cancer Control TNM staging systems classify nodal metastases based on size.15,16 Macrometastases are tumor deposits greater than 2 mm (pN1); micrometastases range in size from greater than 0.2 mm to less or equal to 2 mm or consist of more than 200 carcinoma cells in a single LN section (pN1mi). Isolated tumor cells are single cells or cell clusters each spanning less than 0.2 mm in size and amounting to fewer than 200 carcinoma cells in one LN section [pN0(i+)], regardless of method of detection. If metastatic carcinoma is detected by molecular testing, the pN0 (mol+) designation is used. Of note, the current AJCC staging manual states that sacrificing LN tissue for molecular analysis that would otherwise be available for histologic evaluation and staging is not recommended, particularly when the size of the sacrificed tissue is large enough to contain a macrometastasis.15

SLN is A Safe and Accurate Method of Staging the Axilla in cN0 Patients: NSABP B-32 Clinical Trial

The National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) B-32 randomized prospective clinical trial established SLN biopsy as a safe and effective method for staging the axilla, demonstrating that SLN biopsy is equivalent to ALND in patients with T1 to T2, cN0 invasive breast carcinoma (Table).7 Patients enrolled in the study were staged and treated based on the information obtained on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)–stained sections only (no routine levels, no cytokeratin stains). With a mean follow-up of 96 months, no significant differences in overall survival (OS), disease-free survival (DFS), and locoregional control were reported. A 10-year update of follow-up confirmed these results.17

Table. Summary of Major Sentinel Lymph Node (SLN) Trials.

| Trial | SLN Status | Comparison | No. of Patients Evaluated | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSABP B-327 | Negative | SLNB alone versus SLNB + ALND in T1 to T2, cN0 patients undergoing mastectomy or BCS | SLNB alone, n = 2011 SLNB + ALND, n = 1975 | |

| IBCSG 23-0167 | Positive 1 or more micrometastases | SLNB alone versus SLNB + ALND in T1 to T2 patients undergoing mastectomy or BCS | SLNB alone, n = 467 SLNB + ALND, n = 464 | |

| ACOSOG Z001113,14 | Positive 1 or 2 positive SLNs | SLNB alone versus SLNB + ALND in T1 to T2, cN0 patients undergoing BCS and whole-breast RT | SLNB alone, n = 436 SLNB + ALND, n = 420 | |

| AMAROS76 | Positive 1 or 2 positive SLNs | ALND versus axillary RT in T1 to T2, cN0 patients treated with BCS or mastectomy | ALND, n = 744 Axillary RT, n = 681 | |

|

| ||||

| Extended | ||||

|

| ||||

| Follow-up | Metastatic Non-SLNs in ALND, % | Axillary Recurrence, % | Overall Survival, % | Disease-Free Survival, % |

|

| ||||

| 95.6 mo (mean) | SLNB alone, 0.7 SLNB + ALND, 0.4 (P = .22) | SLNB alone, 90.3a SLNB + ALND, 91.8a (P = .12) | SLNB alone, 81.5a SLNB + ALND, 82.4a (P = .54) | |

| 5 y (median) | 13 | SLNB alone, 0.86 SLNB + ALND, 0.22 | SLNB alone, 97.5 SLNB + ALND, 97.6 (P = .73) | SLNB alone, 87.8 SLNB + ALND, 84.4 (P = .16) |

| 6.3 y (median) | 27 | SLNB alone, 0.9 SLNB + ALND, 0.5 (P = .45) | SLNB alone, 91.8 SLNB + ALND, 92.5 (P = .25) | SLNB alone, 83.8 SLNB + ALND, 82.2 (P = .14) |

| 6.1 y (median) | 33 | ALND, 0.43 Axillary RT, 1.19 | ALND, 93.3 Axillary RT, 92.5 (P = .34) | ALND, 86.9 Axillary RT, 82.7 (P = .18) |

Abbreviations: ACOSOG, American College of Surgeons Oncology Group; ALND, axillary lymph node dissection; AMAROS, After Mapping of the Axilla: Radiotherapy or Surgery?; BCS, breast-conserving surgery; cN0, clinically node negative; IBCSG, International Breast Carcinoma Study Group; NSABP, National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project; RT, radiotherapy; SLNB, sentinel lymph node biopsy.

8-year Kaplan-Meier estimates.

Even in the most experienced hands, SLN biopsy is associated with a false-negative rate. An overview of 69 published studies of SLN biopsy validated with concurrent ALND confirms that SLNs were identified in 7765 of 8059 cases (96%), with an average false-negative rate of 7.3%.18 Wei and colleagues19 identified 63 false-negative cases in a series of 2043 successful SLN mapping procedures (false-negative rate of 3.1%) at their institution. They evaluated the clinicopathologic characteristics of the 63 patients with false-negative SLN biopsy results during a 12-year period and found a higher proportion of lobular or poorly differentiated ductal histology and/or partial or complete replacement of nodes in patients with false-negative SLN biopsies.19

Biologic and Clinical Significance of Occult Metastases

An “occult” metastasis is defined as any metastasis that is missed or not identified on initial examination using a “ standard” evaluation protocol.20 After the introduction of SLN biopsy, many clinicians and pathologists pursued more extensive evaluation of SLN(s), henceforth referred to as “enhanced pathology,” to identify occult metastases, in the belief that this information would be important in predicting patient outcome. Enhanced pathology methods typically involve obtaining additional H&E step-level sections and/or immunohistochemical stains for cytokeratins (CK-IHC) on blocks of SLN that show no evidence of carcinoma in the initial H&E-stained section. The NSABP B-32 study provides information regarding the clinical significance of occult metastases in patients managed with modern treatment modalities.21 Participating sites were instructed to slice SLNs at 2-mm intervals, embed all tissue slices in paraffin blocks, and examine one H&E-stained slide only from each block. This approach aimed to identify all macrometastases (>2 mm). The SLN blocks of patients with no evidence of SLN involvement in the initial H&E-stained section were then submitted to a central laboratory for additional evaluation using the “experimental B-32 protocol,” which consisted of H&E- and CK-IHC–stained sections at depths of 0.5 mm and 1.0 mm into the paraffin block, designed to detect metastases larger than 1.0 mm in size.22 Occult metastases were identified in 616 of 3887 patients (15.9%; 11.1% isolated tumor cells, 4.4% micrometastases, and 0.4% macrometastases).21 Occult metastases were significantly associated with an age of less than 50 years, tumor size larger than 2.0 cm, and planned mastectomy. It is notable that patients in the NSABP B-32 study received systemic therapy (hormonal therapy and/or chemotherapy) based on clinical and pathologic features assessed at the participating institution by the treating physicians. Patients with occult SLN metastases were significantly more likely to receive chemotherapy (P < .001) and/or endocrine therapy (P < .001). At 5-year follow-up, the differences in outcomes for patients with and without occult metastases were found to be statistically significant but amounted to a minimal percent increase with respect to OS (94.6% versus 95.8%), DFS (86.4% versus 89.2%), and distant disease-free interval (89.7% versus 92.5%). Subgroup analysis indicated that smaller metastases had less effect on outcome than larger metastases.

Occult metastases were not discriminatory predictors of cancer recurrence. A total of 138 of 3884 patients (3.6%) had regional or distant recurrences as first events and only 30 of these events (21.7%) (in 0.8% of all patients) occurred in patients with occult metastases. Conversely, 496 of 616 patients with occult metastases (80.5%) were alive and free of disease.21

A companion quality assurance pilot study examined 176 SLN blocks from 54 patients with no evidence of SLN involvement in the initial H&E-stained section using a “comprehensive protocol.” This protocol involved obtaining additional CK-IHC sections at 0.18-mm intervals through the entire block and was designed to detect tumor deposits spanning at least 0.2 mm in size. Occult metastases were detected in 20 of the 176 blocks (11.4%).

As expected, more exhaustive evaluation of SLNs detects a greater number of tumor deposits of smaller size. The use of enhanced pathology techniques to identify occult metastases in initially negative SLNs does not appear to translate into additional clinical benefit, because not all of the patients with occult metastases will necessarily develop recurrent disease, and most of the patients with occult metastases are already treated using available treatment modalities. The current guidelines for staging of patients with breast carcinoma by the AJCC, the College of American Pathologists (CAP), and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) do not recommend the use of routine step-level sections and/or CK-IHC in the evaluation of SLNs. Staging of SLNs (and of ALNs in general) should rest solely on the evaluation of one H&E-stained section of the LNs.23

Clinical Significance of Micrometastases

Micrometastatic breast carcinoma was first defined in 1971 by Huvos et al24 as metastases not greater than 2 mm in size. Women with micrometastases were found to have significantly better 8-year OS compared with women with macrometastases (>2 mm; 17 of 18 patients [94%] versus 28 of 45 patients [62%]).24 A systematic review of 58 studies, many from the pre-SLN era, found that the presence of micrometastases is associated with decreased OS, even after adjustment for other prognostic factors.25 More recent studies have confirmed significant differences in outcome for patients with macrometastases versus micrometastases. A study based on Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data from 209 720 patients who underwent LN staging for breast carcinoma between 1992 and 2003 found that the prognosis of patients with micrometastatic carcinoma, albeit worse than for patients with no evidence of metastatic disease (hazard ratio, 1.35), is significantly better than for patients with macrometastatic disease (hazard ratio, 0.82).26

Prediction of Additional Nodal Burden in Patients with A Positive SLN

Studies have shown that most patients (approximately 60%) with a positive SLN have no residual disease in the axilla3,27–35 and derive no benefit from ALND, whereas they are exposed to its complications. In a bid to estimate the likelihood of additional ALN involvement in patients with limited SLN involvement, investigators have evaluated various clinicopathologic parameters and developed mathematic predictive tools, also known as nomograms, for estimating the risk of additional LN metastases.36–46 Van Zee et al41 developed a nomogram based on multivariable logistic regression analysis on data from 702 patients with a positive SLN who underwent completion ALND at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) in New York, New York. The MSKCC nomogram uses multiple parameters, including tumor size, tumor type, nuclear grade, lymphovascular invasion, multifocality, estrogen receptor (ER) status, method of detection of tumor deposits in the SLN (intraoperative detection, routine H&E-stained slides, serial H&E-stained level sections, or IHC), and number of positive and negative SLNs, to estimate the likelihood of residual disease in the remaining ALNs. When used in a validation cohort of patients who underwent SLN and completion ALND, the MSKCC nomogram was found to be accurate and discriminating, with an area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of 0.76. When prospectively applied in a cohort of 373 patients, the nomogram accurately predicted the likelihood of non-SLN metastases (ROC, 0.77). The MSKCC nomogram calculator is freely accessible online (http://www.mskcc.org/applications/nomograms/breast; accessed May 5, 2015) and provides an estimation of the percentage probability of involvement of additional ALNs given a certain combination of histologic and clinical parameters. This nomogram has been independently validated in cohorts from other institutions in North America, Europe, and Asia, and showed good discriminative power (ROC values between 0.71 and 0.82) in most studies,45,47–56 albeit not in all (ROC, 0.58–0.68).42,57–62

Questioning The Benefit of Completion ALND In All SLN-Positive Patients

In the first decade since the introduction of SLN biopsy most surgeons performed completion ALND in all patients with evidence of SLN involvement. Over time many surgeons modified their practice and did not always perform ALND in cases with limited SLN involvement. Most surgeons using the MSKCC nomogram were opting for no ALND in patients, yielding a nomogram score of 10% or less.63 A declining rate of completion ALND for patients with micrometastatic disease was documented nationwide by analysis of 1998–2005 data collected in the National Cancer Data Base.64 Interestingly, analysis of the data showed no significant differences in the rates of axillary recurrence and 5-year relative survival of patients with either micrometastatic or macrometastatic disease limited to SLNs whether ALND had been performed or not.

A meta-analysis including data from 69 trials reported that in 47% of 3132 cases carcinoma was present only in the SLN.18 Few retrospective studies and small prospective series reported low rates of locoregional recurrence in patients with positive LNs who did not undergo complete ALND in the setting of adjuvant systemic therapy and radiotherapy.10,65,66 The International Breast Cancer Study Group (IBCSG) 23-01 trial found no significant difference in DFS between patients with T1 to T2 cN0 breast carcinoma and SLN micrometastases, with and without ALND (Table).67 Based on this accumulating evidence, questions were raised regarding the need for completion ALND in cN0 patients with limited involvement of SLNs.

ACOSOG Z0011 Trial

The American College of Surgeons Oncology Group (ACOSOG) Z0011 prospective randomized trial assessed the benefit of ALND in patients with 1 or 2 positive SLNs (Table).13,14 Study eligibility criteria included invasive breast carcinoma less than 5 cm with no clinically palpable axillary adenopathy (T1–T2 cN0), H&E-detected metastases in 1 or 2 SLNs, and treatment with breast-conserving surgery to negative margins followed by whole-breast irradiation. Exclusion criteria included 3 or more H&E-positive SLNs, matted LNs or gross extracapsular extension (ECE), CK-IHC–detected SLN metastases, and mastectomy. Radiotherapy to the axilla was also a study exclusion criterion. Adjuvant systemic therapy was as prescribed by the treating physician. At 6.3 years' median follow-up, there were no significant differences in regional LN recurrence, DFS, or OS between patients who underwent ALND and those who did not (Table). The results of the Z0011 study show that patients with T1 to T2 tumors with 2 or fewer positive SLNs, who are treated with breast-conserving surgery and whole-breast irradiation do not benefit from ALND. These results have been practice-changing.68–72 In 2014 the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) published guidelines advising omission of completion ALND for patients with fewer than 3 positive SLNs if there is no evidence of bulky metastatic disease or gross ECE and the patient is treated with whole-breast irradiation.73 The NCCN guidelines recommend considering levels I and II ALND or no further axillary surgery for the patients who fulfill the aforementioned criteria.23

Even though the results of the Z0011 study are widely accepted and have been rapidly adopted at many centers, the trial has been criticized because of the lack of details regarding radiation therapy. The Z0011 protocol stated that all women enrolled in the study were to receive tangential field whole-breast irradiation. The protocol specified that no directed nodal treatment using an additional (third) field should be used.13,14 There was speculation that radiation oncologists, who could not be blinded to patients' axillary surgery assignment, may have adjusted the breast irradiation tangents to include part of the level I/II ALNs more often in the SLN-only arm.74

Jagsi et al75 analyzed radiation therapy records of 605 Z0011 patients and found that 89 patients (15%) had also received treatment to the supraclavicular region. Most of these patients received tangential field radiation therapy alone, with no significant differences in tangential field height between the two study arms. However, 43 of 228 patients (18.9%) in this subgroup received directed nodal irradiation via a third field, in violation of protocol. The highest rates of directed nodal irradiation were among patients with multiple involved LNs. Although this protocol violation occurred with comparable frequency in both cohorts of patients, it is not possible to determine whether the additional irradiation was beneficial, and how it might have influenced the rate of axillary recurrence in the SLN-only group.

ALND or Radiotherapy for Patients With Positive SLNs: AMAROS Trial

The AMAROS (After Mapping of the Axilla: Radiotherapy or Surgery?) prospective randomized clinical trial also addresses the management of the axilla in T1 to T2 cN0 patients with a positive SLN (Table).76 Patients were randomized to ALND or axillary radiotherapy. There were no significant differences in axillary recurrence, DFS, or OS between the two groups. Patients who underwent ALND had a significantly higher incidence of lymphedema at 5 years than patients treated with regional radiotherapy (76 of 328 [23%] versus 31 of 286 [11%] patients), but quality of life was not significantly different in the two groups. The investigators concluded that both treatment strategies provide excellent and comparable axillary control. Overall, the patient population was quite similar to that studied in Z0011, with 609 of 744 patients (82%) in the ALND arm and 557 of 681 patients (82%) in the axillary radiotherapy arm having breast-conserving surgery. However, it has been postulated that most of the patients enrolled in the AMAROS study were not at high risk of axillary recurrence and could be treated without ALND or radiotherapy according to Z0011.77 The AMAROS study does not indicate that all patients with a positive SLN need axillary radiotherapy, and it does not provide an answer to the question of which SLN-positive patients need further axillary treatment. The AMAROS study also includes a subset of patients who underwent mastectomy and were not studied in the Z0011 study. It has been suggested that subgroup analysis of mastectomy patients in the AMAROS trial would be of value.78

Extracapsular Extension

Metastatic carcinoma can invade through the LN capsule into the surrounding axillary fibroadipose tissue. According to CAP, the presence of ECE should be reported and the area of invasion outside of the LN capsule should be included when measuring the largest span of the LN metastasis.79 Studies have shown that focal ECE is present in the SLNs of 19% to 30% of cN0 patients with early-stage breast carcinoma.80–83 To date, the significance of microscopic ECE in SLNs in the selection of patients for ALND or axillary radiotherapy has not been thoroughly assessed. ACOSOG Z0011 excluded patients with matted nodes and gross ECE but had no specific policy regarding microscopic ECE. Extracapsular extension was not documented in the AMAROS trial. Retrospective single-institution studies have shown that ECE in the SLN is significantly associated with non-SLN metastases.81–89 A meta-analysis that included data from 56 studies also found ECE in SLN metastasis to be predictive of non-SLN metastases.90 Furthermore, ECE is recognized as an indicator of poor prognosis82,88,91 and is significantly associated with other negative prognostic factors, such as lymphovascular invasion and SLN macrometastases.83,90,92

The CAP guidelines recommend reporting ECE as present, not identified, or indeterminate.79 At MSKCC the extent of ECE is also routinely included in the pathology report. A retrospective study of a prospectively maintained database of all patients undergoing SLN biopsy at MSKCC investigated the relationship between ECE in the SLN and disease burden in the axilla. The study evaluated 331 patients with microscopic ECE who would have fulfilled the Z0011 study criteria and who underwent ALND between 2006 and 2013.83 Patients with ECE tended to be older, with larger, multifocal, ER-positive tumors, with lymphovascular invasion. Patients with ECE greater than 2 mm were significantly more likely than those with ECE 2 mm or less to have additional positive nodes (80 of 151 patients [66.1%] versus 55 of 180 patients [42.9%]) and 4 or more positive LNs at completion ALND (40 of 151 patients [33.1%] versus 11 of 180 patients [8.6%]). These findings suggest that ECE greater than 2 mm may be an indication for further axillary treatment in patients who otherwise meet Z0011 criteria.

IOE of SLNS

Intraoperative detection of metastatic carcinoma in SLNs leads to immediate ALND, avoiding the need for a delayed second surgical procedure. The disadvantages of intraoperative evaluation (IOE) of SLNs include increase in operation time and possible false-positive results. Frozen section (FS), imprint cytology/touch preparation, or cytologic smear can be used for IOE of SLNs. Cytologic techniques are faster than FS and do not cause significant loss of nodal tissue. The main disadvantage of cytologic techniques rests on the difficulty in validating findings limited to cytology material but not present in H&E-stained sections. Frozen section is time-consuming; freezing introduces artifactual tissue distortion; sectioning of the frozen tissue block could potentially lead to loss of critical tissue. Despite these disadvantages, FS is often the preferred method of IOE by most surgical pathologists. A meta-analysis, including 47 FS studies, reported a mean sensitivity of 73%, with higher sensitivity for macrometastases than micrometastases (94% versus 40%).93 A meta-analysis of 31 studies of imprint cytology/touch preparation identified an overall sensitivity of 63%, and, similar to FS, the sensitivity for detection of macrometastases was higher than for micrometastases (81% versus 22%).94 At our institution, a study of 305 SLNs from 133 patients showed that touch preparation, cytologic smear, and FS had comparable sensitivities (59%, 57%, and 59%, respectively),95 and each method was more sensitive in detecting macrometastases (96%, 93%, and 93%, respectively) than micrometastases (27%, 27%, and 30%, respectively). One-step nucleic acid amplification is a molecular technique that measures CK19 mRNA in homogenized SLN and is used for IOE. One-step nucleic acid amplification shows high sensitivity with increased identification of low-volume nodal disease. Concerns about this technique relate to the fact that one-step nucleic acid amplification–based staging is not a recognized prognosticator, and homogenization of tissue required for analysis precludes assessment of important morphologic features, such as size of the tumor deposit and ECE.96 A recent meta-analysis identified a pooled positive predictive value for detecting macrometastases of 0.79, suggesting that up to 21% of patients found to have macrometastases using one-step nucleic acid amplification would have an axillary clearance when histology would have classified the deposits as non-macrometastases.97

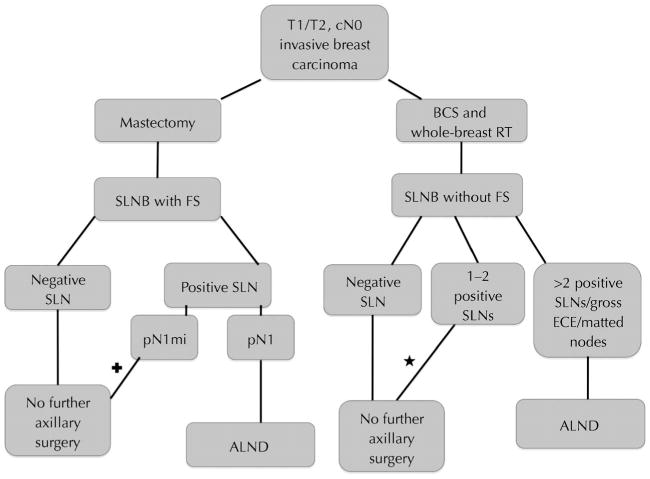

The publication of the results of Z0011 has reduced the use of IOE. A review of practice patterns at the MD Anderson Cancer Center found that surgeons were less likely to request IOE of SLNs in post-Z0011 patients (84 of 323 post-Z0011 patients [26%] versus 230 of 335 pre-Z0011 patients [69%]).68 Currently, IOE of SLNs of clinically “Z0011 eligible” patients is not routinely performed at most centers, including our own, and the decision to proceed to ALND is made at a later time when all of the clinical and definitive pathologic information is available. The IOE of SLNs continues to be performed routinely at many centers, including MSKCC, for cN0 patients undergoing mastectomy. The role of SLN-FS has been incorporated into our proposed SLN algorithm for T1 to T2 cN0 patients (Figure). Despite its many disadvantages, FS is often the preferred method of IOE by most surgical pathologists. Pathologists should use the IOE method they are most comfortable with and work with their multidisciplinary teams to devise protocols suitable to the needs of local practice.

Figure.

Proposed management algorithm for patients with T1/T2 clinically node-negative (cN0; ie, no palpable axillary adenopathy on clinical examination) invasive breast carcinoma. Abbreviations: ALND, axillary lymph node dissection; BCS, breast-conserving surgery; ECE, extracapsular extension; FS, frozen section; pN1, macrometastatic disease; pN1mi, micrometastatic disease; RT, radiotherapy; SLN, sentinel lymph node; SLNB, sentinel lymph node biopsy. + and ★: Avoidance of axillary lymph node dissection may be considered. Some cases may require multidisciplinary team discussion.

Recommended Protocol for Histologic Evaluation of SLN

A standardized SLN evaluation protocol combines careful gross and histologic evaluation.98 The number of SLNs involved by metastatic carcinoma dictates whether a patient with T1 to T2 cN0 meets Z0011 eligibility criteria. Careful gross examination of the SLN sample involves removal of excess adipose tissue and accurate count of the number of SLNs. As per CAP and ASCO guidelines,73,79 each SLN is sectioned into 2-mm–thick slices parallel to the long axis of the LN. Care should be taken into placing nonadjacent cut surfaces face down in the cassette to maximize LN evaluation for SLNs that are sectioned into more than 2 slices. Size permitting, each SLN is submitted in one cassette. If 2 (or more) SLNs are submitted in the same cassette, each SLN needs to be marked with a different color ink, and this information needs to be incorporated in the gross description, to allow an accurate count of the number of SLNs involved by metastatic carcinoma whenever the latter is present. One H&E-stained section per block is evaluated. The H&E-stained section should provide a full cross section of each SLN slice, including subcapsular space and SLN capsule. Immunohistochemical stains for cytokeratins and sections from additional levels are obtained in selected cases to further investigate uncertain morphologic findings but are not performed routinely. The final report should include the total number of SLNs examined, the number of SLNs with metastatic carcinoma, the span of the largest metastatic focus,73,79 and information on ECE (present, absent, or indeterminate).79 At our institution we also comment on the largest extent of ECE (<2 mm, 2 mm, or >2 mm).

Summary

Recent clinical trials have shown that ALND provides no outcome benefit to cN0 patients with limited SLN involvement who are treated with a combination of breast-conserving surgery, whole-breast irradiation, and systemic therapy. This has changed the clinical management of the axilla, resulting in fewer ALNDs in selected SLN-positive patients. This is reflected in our proposed management algorithm for patients with T1/T2 cN0 invasive breast carcinoma, which is largely based on current clinical practice at MSKCC (Figure). The identification of occult metastases does not appear to be of clinical benefit in contemporary T1 to T2 cN0 patients, who are receiving adjuvant systemic therapy in most cases. The main goal of SLN examination should be to detect all macrometastases (>2 mm) and the use of deeper-level sections and CK-IHC is not warranted in routine practice. Further studies are needed to refine the management of the axilla in SLN-positive patients who were not included, underrepresented, or unspecified in the aforementioned clinical trials, such as patients undergoing mastectomy, HER2-positive patients, and patients with microscopic ECE.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms Angelica Martin (pathologist office assistant, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center), for her assistance with editing of the manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors have no relevant financial interest in the products or companies described in this article.

Presented in part at the 2nd Princeton Integrated Pathology Symposium: Breast Pathology; February 8, 2015; Plainsboro, New Jersey.

References

- 1.Early stage breast cancer: consensus statement: NIH consensus development conference, June 18-21, 1990. Cancer Treat Res. 1992;60:383–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borup Christensen S, Lundgren E. Sequelae of axillary dissection vs. axillary sampling with or without irradiation for breast cancer: a randomized trial. Acta Chirurgica Scand. 1989;155(10):515–519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giuliano AE, Jones RC, Brennan M, Statman R. Sentinel lymphadenectomy in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(6):2345–2350. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.6.2345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roses DF, Brooks AD, Harris MN, Shapiro RL, Mitnick J. Complications of level I and II axillary dissection in the treatment of carcinoma of the breast. Ann Surg. 1999;230(2):194–201. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199908000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kell MR, Burke JP, Barry M, Morrow M. Outcome of axillary staging in early breast cancer: a meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;120(2):441–447. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0705-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson SJ, Wapnir I, Dignam JJ, et al. Prognosis after ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence and locoregional recurrences in patients treated by breast-conserving therapy in five National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project protocols of node-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(15):2466–2473. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.8424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krag DN, Anderson SJ, Julian TB, et al. Sentinel-lymph-node resection compared with conventional axillary-lymph-node dissection in clinically node-negative patients with breast cancer: overall survival findings from the NSABP B-32 randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(10):927–933. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70207-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Canavese G, Catturich A, Vecchio C, et al. Sentinel node biopsy compared with complete axillary dissection for staging early breast cancer with clinically negative lymph nodes: results of randomized trial. Ann Oncol. 2009;20(6):1001–1007. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mansel RE, Fallowfield L, Kissin M, et al. Randomized multicenter trial of sentinel node biopsy versus standard axillary treatment in operable breast cancer: the ALMANAC Trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(9):599–609. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Veronesi U, Paganelli G, Viale G, et al. A randomized comparison of sentinel-node biopsy with routine axillary dissection in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(6):546–553. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Veronesi U, Viale G, Paganelli G, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in breast cancer: ten-year results of a randomized controlled study. Ann Surg. 2010;251(4):595–600. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181c0e92a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zavagno G, De Salvo GL, Scalco G, et al. A randomized clinical trial on sentinel lymph node biopsy versus axillary lymph node dissection in breast cancer: results of the Sentinella/GIVOM trial. Ann Surg. 2008;247(2):207–213. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31812e6a73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giuliano AE, Hunt KK, Ballman KV, et al. Axillary dissection vs no axillary dissection in women with invasive breast cancer and sentinel node metastasis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2011;305(6):569–575. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giuliano AE, McCall L, Beitsch P, et al. Locoregional recurrence after sentinel lymph node dissection with or without axillary dissection in patients with sentinel lymph node metastases: the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Z0011 randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2010;252(3):426–432. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181f08f32. discussion 432–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edge S, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th. New York, NY: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sobin LHGM, Wittekind C, editors. eds UICC TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours. 7th. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Julian T, Anderson SJ, Krag DN, et al. 10-yr follow-up results of NSABP B-32, a randomized phase III clinical trial to compare sentinel node resection (SNR) to conventional axillary dissection (AD) in clinically node-negative breast cancer patients. Paper presented at: 2013 ASCO Annual Meeting; May 31–June 4, 2013; Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim T, Giuliano AE, Lyman GH. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymph node biopsy in early-stage breast carcinoma: a metaanalysis. Cancer. 2006;106(1):4–16. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wei S, Bleiweiss IJ, Nagi C, Jaffer S. Characteristics of breast carcinoma cases with false-negative sentinel lymph nodes. Clin Breast Cancer. 2014;14(4):280–284. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2013.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weaver D. Sentinel lymph nodes and breast cancer. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:842–847. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200306000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weaver DL, Ashikaga T, Krag DN, et al. Effect of occult metastases on survival in node-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(5):412–421. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1008108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weaver DL, Le UP, Dupuis SL, et al. Metastasis detection in sentinel lymph nodes: comparison of a limited widely spaced (NSABP protocol B-32) and a comprehensive narrowly spaced paraffin block sectioning strategy. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33(11):1583–1589. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181b274e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. [Accessed February 25, 2015];Breast Cancer Version 1.2015. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast.pdf.

- 24.Huvos AG, Hutter RV, Berg JW. Significance of axillary macrometastases and micrometastases in mammary cancer. Ann Surg. 1971;173(1):44–46. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197101000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Boer M, van Dijck JA, Bult P, Borm GF, Tjan-Heijnen VC. Breast cancer prognosis and occult lymph node metastases, isolated tumor cells, and micrometastases. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102(6):410–425. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen SL, Hoehne FM, Giuliano AE. The prognostic significance of micrometastases in breast cancer: a SEER population-based analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14(12):3378–3384. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9513-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Albertini JJ, Lyman GH, Cox C, et al. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel node biopsy in the patient with breast cancer. JAMA. 1996;276(22):1818–1822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Borgstein PJ, Pijpers R, Comans EF, van Diest PJ, Boom RP, Meijer S. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in breast cancer: guidelines and pitfalls of lymphoscintigraphy and gamma probe detection. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;186(3):275–283. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(98)00011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Giuliano AE, Kirgan DM, Guenther JM, Morton DL. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymphadenectomy for breast cancer. Ann Surg. 1994;220(3):391–398. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199409000-00015. discussion 398–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krag D, Weaver D, Ashikaga T, et al. The sentinel node in breast cancer–a multicenter validation study. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(14):941–946. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199810013391401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krag DN, Anderson SJ, Julian TB, et al. Technical outcomes of sentinel-lymph-node resection and conventional axillary-lymph-node dissection in patients with clinically node-negative breast cancer: results from the NSABP B-32 randomised phase III trial. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8(10):881–888. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70278-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krag DN, Weaver DL, Alex JC, Fairbank JT. Surgical resection and radiolocalization of the sentinel lymph node in breast cancer using a gamma probe. Surg Oncol. 1993;2(6):335–339. doi: 10.1016/0960-7404(93)90064-6. discussion 340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lyman GH, Giuliano AE, Somerfield MR, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology guideline recommendations for sentinel lymph node biopsy in early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(30):7703–7720. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Turner RR, Chu KU, Qi K, et al. Pathologic features associated with nonsentinel lymph node metastases in patients with metastatic breast carcinoma in a sentinel lymph node. Cancer. 2000;89(3):574–581. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000801)89:3<574::aid-cncr12>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Veronesi U, Paganelli G, Galimberti V, et al. Sentinel-node biopsy to avoid axillary dissection in breast cancer with clinically negative lymph-nodes. Lancet. 1997;349(9069):1864–1867. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)01004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Houvenaeghel G, Nos C, Giard S, et al. A nomogram predictive of non-sentinel lymph node involvement in breast cancer patients with a sentinel lymph node micrometastasis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2009;35(7):690–695. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Katz A, Niemierko A, Gage I, et al. Can axillary dissection be avoided in patients with sentinel lymph node metastasis? J Surg Oncol. 2006;93(7):550–558. doi: 10.1002/jso.20514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Katz A, Smith BL, Golshan M, et al. Nomogram for the prediction of having four or more involved nodes for sentinel lymph node-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(13):2093–2098. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.9479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mittendorf EA, Hunt KK, Boughey JC, et al. Incorporation of sentinel lymph node metastasis size into a nomogram predicting nonsentinel lymph node involvement in breast cancer patients with a positive sentinel lymph node. Ann Surg. 2012;255(1):109–115. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318238f461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rubio IT, Espinosa-Bravo M, Rodrigo M, et al. Nomogram including the total tumoral load in the sentinel nodes assessed by one-step nucleic acid amplification as a new factor for predicting nonsentinel lymph node metastasis in breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;147(2):371–380. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-3108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Van Zee KJ, Manasseh DM, Bevilacqua JL, et al. A nomogram for predicting the likelihood of additional nodal metastases in breast cancer patients with a positive sentinel node biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10(10):1140–1151. doi: 10.1245/aso.2003.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pal A, Provenzano E, Duffy SW, Pinder SE, Purushotham AD. A model for predicting non-sentinel lymph node metastatic disease when the sentinel lymph node is positive. Br J Surg. 2008;95(3):302–309. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Degnim AC, Reynolds C, Pantvaidya G, et al. Nonsentinel node metastasis in breast cancer patients: assessment of an existing and a new predictive nomogram. Am J Surg. 2005;190(4):543–550. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hwang RF, Krishnamurthy S, Hunt KK, et al. Clinicopathologic factors predicting involvement of nonsentinel axillary nodes in women with breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10(3):248–254. doi: 10.1245/aso.2003.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kohrt HE, Olshen RA, Bermas HR, et al. New models and online calculator for predicting non-sentinel lymph node status in sentinel lymph node positive breast cancer patients. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:66. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barranger E, Coutant C, Flahault A, Delpech Y, Darai E, Uzan S. An axilla scoring system to predict non-sentinel lymph node status in breast cancer patients with sentinel lymph node involvement. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005;91(2):113–119. doi: 10.1007/s10549-004-5781-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smidt ML, Kuster DM, van der Wilt GJ, Thunnissen FB, Van Zee KJ, Strobbe LJ. Can the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center nomogram predict the likelihood of nonsentinel lymph node metastases in breast cancer patients in the Netherlands? Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12(12):1066–1072. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2005.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ponzone R, Maggiorotto F, Mariani L, et al. Comparison of two models for the prediction of nonsentinel node metastases in breast cancer. Am J Surg. 2007;193(6):686–692. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Specht MC, Kattan MW, Gonen M, Fey J, Van Zee KJ. Predicting nonsentinel node status after positive sentinel lymph biopsy for breast cancer: clinicians versus nomogram. Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12(8):654–659. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2005.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lambert LA, Ayers GD, Meric-Bernstam F. Validation of a breast cancer nomogram for predicting nonsentinel lymph node metastases after a positive sentinel node biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14(8):2422–2423. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9419-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cripe MH, Beran LC, Liang WC, Sickle-Santanello BJ. The likelihood of additional nodal disease following a positive sentinel lymph node biopsy in breast cancer patients: validation of a nomogram. Am J Surg. 2006;192(4):484–487. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Soni NK, Carmalt HL, Gillett DJ, Spillane AJ. Evaluation of a breast cancer nomogram for prediction of non-sentinel lymph node positivity. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2005;31(9):958–964. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2005.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hessman CJ, Naik AM, Kearney NM, et al. Comparative validation of online nomograms for predicting nonsentinel lymph node status in sentinel lymph node-positive breast cancer. Arch Surg. 2011;146(9):1035–1040. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chue KM, Yong WS, Thike AA, et al. Predicting the likelihood of additional lymph node metastasis in sentinel lymph node positive breast cancer: validation of the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Centre (MSKCC) nomogram. J Clin Pathol. 2014;67(2):112–119. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2013-201524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sasada T, Kataoka T, Shigematsu H, et al. Three models for predicting the risk of non-sentinel lymph node metastasis in Japanese breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer. 2014;21(5):571–575. doi: 10.1007/s12282-012-0435-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sasada T, Murakami S, Kataoka T, et al. Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center Nomogram to predict the risk of non-sentinel lymph node metastasis in Japanese breast cancer patients. Surg Today. 2012;42(3):245–249. doi: 10.1007/s00595-011-0088-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van den Hoven I, Kuijt GP, Voogd AC, van Beek MW, Roumen RM. Value of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center nomogram in clinical decision making for sentinel lymph node-positive breast cancer. Br J Surg. 2010;97(11):1653–1658. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dauphine CE, Haukoos JS, Vargas MP, Isaac NM, Khalkhali I, Vargas HI. Evaluation of three scoring systems predicting non sentinel node metastasis in breast cancer patients with a positive sentinel node biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14(3):1014–1019. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9223-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Poirier E, Sideris L, Dube P, Drolet P, Meterissian SH. Analysis of clinical applicability of the breast cancer nomogram for positive sentinel lymph node: the Canadian experience. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(9):2562–2567. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0033-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Klar M, Foeldi M, Markert S, Gitsch G, Stickeler E, Watermann D. Good prediction of the likelihood for sentinel lymph node metastasis by using the MSKCC nomogram in a German breast cancer population. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(5):1136–1142. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0399-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Coufal O, Pavlik T, Fabian P, et al. Predicting non-sentinel lymph node status after positive sentinel biopsy in breast cancer: what model performs the best in a Czech population? Pathol Oncol Res. 2009;15(4):733–740. doi: 10.1007/s12253-009-9177-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nadeem RM, Gudur LD, Saidan ZA. An independent assessment of the 7 nomograms for predicting the probability of additional axillary nodal metastases after positive sentinel lymph node biopsy in a cohort of British patients with breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer. 2014;14(4):272–279. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Park J, Fey JV, Naik AM, Borgen PI, Van Zee KJ, Cody HS., III A declining rate of completion axillary dissection in sentinel lymph node-positive breast cancer patients is associated with the use of a multivariate nomogram. Ann Surg. 2007;245(3):462–468. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000250439.86020.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bilimoria KY, Bentrem DJ, Hansen NM, et al. Comparison of sentinel lymph node biopsy alone and completion axillary lymph node dissection for node-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(18):2946–2953. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.5750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Giuliano AE, Haigh PI, Brennan MB, et al. Prospective observational study of sentinel lymphadenectomy without further axillary dissection in patients with sentinel node-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(13):2553–2559. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.13.2553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bergkvist L, de Boniface J, Jonsson PE, et al. Axillary recurrence rate after negative sentinel node biopsy in breast cancer: three-year follow-up of the Swedish Multicenter Cohort Study. Ann Surg. 2008;247(1):150–156. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318153ff40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Galimberti V, Cole BF, Zurrida S, et al. Axillary dissection versus no axillary dissection in patients with sentinel-node micrometastases (IBCSG 23-01): a phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(4):297–305. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70035-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Caudle AS, Hunt KK, Tucker SL, et al. American College of Surgeons Oncology Group (ACOSOG) Z0011: impact on surgeon practice patterns. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(10):3144–3151. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2531-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gainer SM, Hunt KK, Beitsch P, Caudle AS, Mittendorf EA, Lucci A. Changing behavior in clinical practice in response to the ACOSOG Z0011 trial: a survey of the American Society of Breast Surgeons. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(10):3152–3158. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2523-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Massimino KP, Hessman CJ, Ellis MC, Naik AM, Vetto JT. Impact of American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Z0011 and National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-32 trial results on surgeon practice in the Pacific Northwest. Am J Surg. 2012;203(5):618–622. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yi M, Kuerer HM, Mittendorf EA, et al. Impact of the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Z0011 criteria applied to a contemporary patient population. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216(1):105–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wright GP, Mater ME, Sobel HL, et al. Measuring the impact of the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Z0011 trial on breast cancer surgery in a community health system. Am J Surg. 2015;209(2):240–245. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lyman GH, Temin S, Edge SB, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for patients with early-stage breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(13):1365–1383. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zellars RC. New information prompts old question: is sentinel lymph node sampling equivalent to axillary lymph node dissection? J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(32):3583–3585. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.9946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jagsi R, Chadha M, Moni J, et al. Radiation field design in the ACOSOG Z0011 (Alliance) Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(32):3600–3606. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.5838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Donker M, van Tienhoven G, Straver ME, et al. Radiotherapy or surgery of the axilla after a positive sentinel node in breast cancer (EORTC 10981-22023 AMAROS): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(12):1303–1310. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70460-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Boughey JC. How do the AMAROS trial results change practice? Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(12):1280–1281. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71018-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pilewskie ML, Morrow M. Management of the clinically node-negative axilla: what have we learned from the clinical trials? Oncology. 2014;28(5):371–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lester SC, Bose S, Chen YY, et al. Protocol for the examination of specimens from patients with invasive carcinoma of the breast. Coll Am Pathol. 2013 doi: 10.5858/133.10.1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Goyal A, Douglas-Jones A, Newcombe RG, Mansel RE, Group AT. Predictors of non-sentinel lymph node metastasis in breast cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40(11):1731–1737. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Stitzenberg KB, Meyer AA, Stern SL, et al. Extracapsular extension of the sentinel lymph node metastasis: a predictor of nonsentinel node tumor burden. Ann Surg. 2003;237(5):607–612. doi: 10.1097/01.SLA.0000064361.12265.9A. discussion 612–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Choi AH, Surrusco M, Rodriguez S, et al. Extranodal extension on sentinel lymph node dissection: why should we treat it differently? Am Surg. 2014;80(10):932–935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gooch J, King TA, Eaton A, et al. The extent of extracapsular extension may influence the need for axillary lymph node dissection in patients with T1-T2 breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(9):2897–2903. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3752-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kapur U, Rubinas T, Ghai R, Sinacore J, Yao K, Rajan PB. Prediction of nonsentinel lymph node metastasis in sentinel node-positive breast carcinoma. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2007;11(1):10–12. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2006.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Boler DE, Uras C, Ince U, Cabioglu N. Factors predicting the non-sentinel lymph node involvement in breast cancer patients with sentinel lymph node metastases. Breast. 2012;21(4):518–523. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2012.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Beriwal S, Soran A, Kocer B, Wilson JW, Ahrendt GM, Johnson R. Factors that predict the burden of axillary disease in breast cancer patients with a positive sentinel node. Am J Clin Oncol. 2008;31(1):34–38. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e318068419b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fujii T, Yanagita Y, Fujisawa T, Hirakata T, Iijima M, Kuwano H. Implication of extracapsular invasion of sentinel lymph nodes in breast cancer: prediction of nonsentinel lymph node metastasis. World J Surg. 2010;34(3):544–548. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0389-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Shigematsu H, Taguchi K, Koui H, Ohno S. Clinical significance of extracapsular invasion at sentinel lymph nodes in breast cancer patients with sentinel lymph node involvement. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(7):2365–2371. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-4269-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dengel LT, Van Zee KJ, King TA, et al. Axillary dissection can be avoided in the majority of clinically node-negative patients undergoing breast-conserving therapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(1):22–27. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3200-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.van la Parra RF, Peer PG, Ernst MF, Bosscha K. Meta-analysis of predictive factors for non-sentinel lymph node metastases in breast cancer patients with a positive SLN. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2011;37(4):290–299. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bucci JA, Kennedy CW, Burn J, et al. Implications of extranodal spread in node positive breast cancer: a review of survival and local recurrence. Breast. 2001;10(3):213–219. doi: 10.1054/brst.2000.0233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Altinyollar H, Berberoglu U, Gulben K, Irkin F. The correlation of extranodal invasion with other prognostic parameters in lymph node positive breast cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2007;95(7):567–571. doi: 10.1002/jso.20758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Liu LC, Lang JE, Lu Y, et al. Intraoperative frozen section analysis of sentinel lymph nodes in breast cancer patients: a meta-analysis and single-institution experience. Cancer. 2011;117(2):250–258. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tew K, Irwig L, Matthews A, Crowe P, Macaskill P. Meta-analysis of sentinel node imprint cytology in breast cancer. Br J Surg. 2005;92(9):1068–1080. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Brogi E, Torres-Matundan E, Tan LK, Cody HS., III The results of frozen section, touch preparation, and cytological smear are comparable for intraoperative examination of sentinel lymph nodes: a study in 133 breast cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12(2):173–180. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2005.03.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Cserni G. Intraoperative analysis of sentinel lymph nodes in breast cancer by one-step nucleic acid amplification. J Clin Pathol. 2012;65(3):193–199. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2011-200301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Tiernan JP, Verghese ET, Nair A, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of cytokeratin 19-based one-step nucleic acid amplification versus histopathology for sentinel lymph node assessment in breast cancer. Br J Surg. 2014;101(4):298–306. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Weaver DL. Pathology evaluation of sentinel lymph nodes in breast cancer: protocol recommendations and rationale. Mod Pathol. 2010;23(suppl 2):S26–S32. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]