Abstract

Mammalian cytochrome P450 2B4 (CYP2B4) is a phenobarbital-inducible rabbit hepatic monooxygenase that catalyzes the N-demethylation of benzphetamine and metabolism of numerous other compounds. To probe the interactions of the heme environment and bound benzphetamine with the dioxygen (O2) complex of CYP2B4, homogeneous O2 complexes of the wild-type enzyme and three mutants at sites of conserved amino acids, two on the heme distal side (T302A and E301Q) and one on the proximal side (F429H), have been prepared and stabilized at ~−50 °C in mixed solvents (60–70% v/v glycerol). We report that the magnetic circular dichroism and electronic absorption spectra of wild-type oxyferrous CYP2B4, in the presence and absence of substrate, are quite similar to those of the dioxygen complex of bacterial cytochrome P450-CAM (CYP101). However, the oxyferrous complexes of the T302A and E301Q CYP2B4 mutants have significantly perturbed electronic structure (~4 nm and ~3 nm red-shifted Soret features, respectively) compared to that of the wild-type oxyferrous complex. On the other hand, the heme proximal side mutant, CYP2B4 F429H, undergoes relatively facile conversion to a partially (~50%) denatured (P420) form upon reduction. The structural changes in the heme pocket environments of the CYP2B4 mutants that lead to the spectroscopic distinctions reported herein can be related to the differences in oxidation activities of wild-type CYP2B4 and its E301Q, T302A and F429H mutants.

Keywords: CYP2B4, Oxyferrous complex, CYP2B4 T302A mutant, CYP2B4 E301Q mutant, CYP2B4 F429H mutant, Magnetic circular dichroism (MCD)

1. Introduction

The cytochrome P450s are a large family of monooxygenase enzymes that play a central role in drug metabolism in humans [1–5]. Understanding the structure, function and redox reactions of these enzymes is essential to the full elucidation of their mechanisms of action [2]. The main P450 reaction involves oxidation of unactivated C–H bonds in organic substrates (RH) to yield oxygenated products (ROH) (Eq. (1)).

| (1) |

Substrate binding to the ferric enzyme initiates catalysis by facilitating the first electron transfer to yield the ferrous state which then binds dioxygen. The P450 heme iron-dioxygen complex [6–9] autoxidizes to iron(III) and superoxide anion with a rate constant for P450-CAM (CYP101) of 0.01 s−1 at room temperature [10]. Substrate oxygenation is completed following the second electron transfer, addition of two protons leading to release of a water molecule and formation of an “activated oxygen complex” generally thought to be responsible for oxygen atom insertion [1].

Investigations of the effect of replacing the highly conserved distal pocket threonine in CYP2B4 with alanine support the concept that there are three distinct oxidants in the reaction cycle, namely: the nucleophilic peroxo–iron state, the nucleophilic/electrophilic hydroperoxo–iron intermediate and the electrophilic oxo–iron (compound I) adduct [11,12]. This conclusion is based on results obtained from studies of the Thr to Ala mutants where changes in rates of several P450 reactions were observed. This mutation is believed to disrupt the proton delivery system to the heme iron center [13–15].

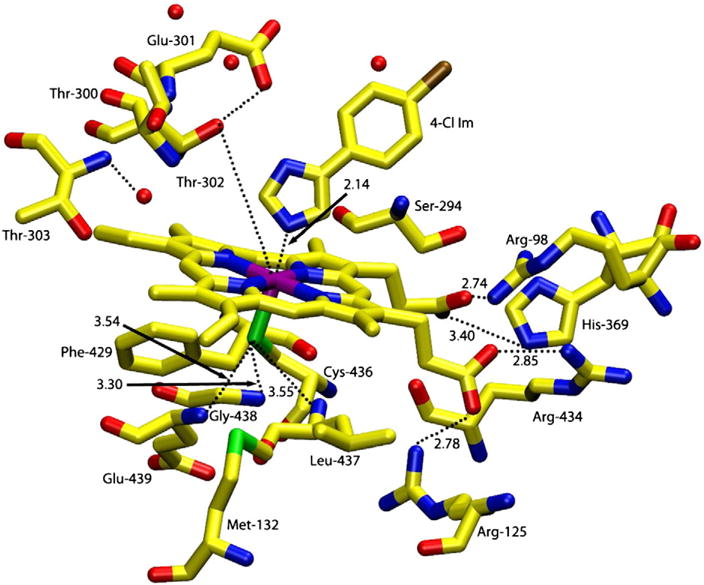

The active site of rabbit phenobarbital-inducible hepatic CYP2B4 contains an iron protoporphyrin IX, heme b, coordinated axially by a cysteine thiolate (Cys-436) [16] as shown in Fig. 1. Many factors affect the electronic nature of the active heme center including vinyl substituent conjugation with the porphyrin π-system, propionate group hydrogen bonding, the proximal thiolate push [1,2] and the distal pocket hydrogen bonding network [12]. Binding of sterically varied substrates to the hydrophobic cavity of CYP2B4 perturbs the heme environment and has been investigated using surface enhanced resonance Raman scattering (SERRS) [17]. The donor properties of the active site proximal thiolate are strongly influenced by the presence of three peptide amide nitrogen to sulfur hydrogen bonds (NH⋯S).2 The calculated redox potential shift for each NH⋯S hydrogen bond is roughly +35 to +45 mV [18]. This proximal push effect has been probed extensively using site directed mutagenesis in CYP101 [18,19], which also has three NH⋯S hydrogen bonds.2 Further, analysis of distal pocket shows a network for proton delivery based on the hydrogen bonding involving Thr302, Glu301 and two adjacent water molecules as shown in Fig. 1. Structural alterations of the heme iron environment are thus intrinsically linked to the enzymatic activity of the enzyme [13,20].

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the active site structure of ferric wild-type cytochrome CYP2B4 with 4-(4-chlorophenyl)imidazole bound [16]. Prepared using pdb file 1SUO.

Investigations of the dioxygen bound complex of many P450s have been hampered by their high rate of autoxidation [6–9]. The anionic cysteinate proximal ligand in P450 increases the autoxidation rate relative to histidine-ligated globins [10]. The same “push” effect has been proposed to play a key role in the heterolytic O–O bond cleavage in the ferric-hydroperoxo complex leading to the high valent iron-oxo species [1,2]. For example, the Cys357His mutant of CYP101 has lower proximal push effect and less facile O–O bond cleavage of the iron-peroxo intermediate [19,21]. Substrate modulation of the properties and reaction of the hydroperoxo-ferric cytochrome CYP101 as shown by cryoreduction electron spin resonance/electron-nuclear double resonance (EPR/ENDOR) spectroscopy have indicated that the substrate can play a key role in determining the enzyme’s ‘choice’ of reactive intermediate for its ‘induced reactivity’ [22].

In the present study, we have investigated the relationship between substrate (benzphetamine) and small ligand (O2, NO and CO) binding in the distal heme cavity for wild-type CYP2B4 and its T302A, F429H and E301Q mutants. Preparation of unstable ferrous-oxy complexes has been achieved with a cryo solvent mixture (70% glycerol: buffer) at temperatures as low as −50 to −60 °C. We have shown that trans axial ligand coordination (O2, NO and CO) introduces spectral shifts which illustrate how altered polarity of the distal pocket can affect the axial ‘push’ effect. The results described herein indicate that magnetic circular dichroism (MCD) and electronic absorption spectra can provide valuable information on the oxidation, spin state, nature of axial ligation and are sensitive to subtle changes in the heme pocket environment.

2. Experimental procedures

2.1. Materials

O2 and CO gases were obtained from Matheson Co. Sodium dithionite, glycerol and all other chemicals were purchased from Aldrich or Sigma and used as received. Sodium dithionite was kept in a desiccator under N2 to maintain its effectiveness as a reductant. Benzphetamine hydrochloride was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich.

2.2. Wild Type CYP2B4 and its E301Q, T302A and F429H mutants

Wild-type cytochrome P450-CYP2B4 and its E301Q, T302A and F429H mutants were expressed in Escherichia coli, purified [13] and stored at −80 °C in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) containing 10% glycerol. Concentrations of the ferric enzymes (the wild-type and the three mutants) were determined by the method of Omura and Sato [23] both in aqueous buffer and in 70% glycerol at 4 °C.

2.3. Spectroscopic techniques

Electronic absorption spectra were recorded with a Varian-Cary 400 spectrophotometer (at 4 or ~25 °C) or a JASCO J600A spectropolarimeter (at ~−50 °C). Magnetic circular dichroism (MCD) spectra were measured in 0.2- or 0.5-cm cuvettes at a magnetic field of 1.41T with the JASCO J600A spectropolarimeter as described [24]. The JASCO J600 spectropolarimeter is equipped for the simultaneous recording of both MCD (or CD) and electronic absorption (as transmission) spectra. MCD data manipulations were carried out as previously reported [24] using JASCO software.

2.4. Sample preparations

To substrate-free ferric wild-type and mutant CYP2B4 enzyme solutions (~50 μM) in 60 or 70% glycerol (40 or 30% 0.1 or 0.3 M potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.7–8.1), up to ~5 mM benzphetamine was added at 4 °C. The samples started becoming turbid at and above ~3 mM benzphetamine because of its relatively poor solubility in the glycerol/aqueous buffer solvents. For O2 complex preparations, the ferric substrate-bound enzyme was degassed in a rubber septum-sealed cuvette with a stream of nitrogen gas through syringe needles for >2.5 h on ice and then reduced by micro-liter additions of near-minimal amounts of Na2S2O4 (up to 0.5 mM from a 20 mg/mL anaerobic stock solution) under N2 at ~25 °C to generate deoxyferrous CYP2B4. Complete reduction (final Soret peaks at 414 to 415 nm except for the F429H mutant, see Results and discussion) took 2 to 4 h under these conditions. The sample was then cooled down to about −50 °C. CYP2B4-O2 complexes were prepared at ~−50 °C in a chest freezer by thorough bubbling with pre-cooled O2 that was passed through a liquid nitrogen-immersed coiled copper tubing [25]. At ~−50 °C, the mixed solvent becomes a viscous glassy-like state and the bubbling O2 through such a state is not as effective as through an ordinary solution. After O2 bubbling for 2–5 min through a syringe needle, the sample was transferred to the pre-cooled cuvette holder of the Jasco J600 for MCD recording. This O2 addition process was repeated several times until an MCD signal of the deoxyferrous enzyme species completely disappeared. Nitric oxide (NO) complexes of the ferric and ferrous CYP2B4 enzymes (wild-type and mutants) were prepared according to the procedures described elsewhere [26].

2.5. Determination of dissociation constants (Kd values) and estimation of the spin states of the ferric complexes in the mixed solvents

Kd values were determined by spectrophotometric titrations and spin states of the complex of ferric CYP2B4 with the substrate (benzphetamine) were estimated as described previously for the case of CYP101 [27]. Since ferric CYP2B4 does not form a ~100% high spin complex upon binding of its substrates, the spectrum of camphor-bound CYP101 was used as a 100% high spin spectrum for the spin state estimation for the benzphetamine–ferric CYP2B4 complexes.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Spectral properties of ferric and ferrous wild-type and mutant CYP2B4s in 60–70% (v/v) glycerol

The electronic absorption spectral properties of ferric wild-type CYP2B4 and the three mutants, E301Q, T302A and F429H in 60–70% glycerol have been carefully investigated (Fig. S1). Addition of the substrate, benzphetamine, to the ferric proteins causes the usual partial spin state change with the T302A mutant undergoing the largest low- to high-spin conversion and the F429H mutant displaying the smallest shift. The spin shift was much smaller at 4 °C and −50 °C than at 25 °C. The electronic absorption and magnetic circular dichroism (MCD) spectral properties of the deoxyferrous proteins (Figs. S2 and S3) are characteristic of ferrous P450 [28]. A second, minor spectral species is found in differing amounts in all ferrous samples, most evident, especially at lower temperatures, as a sharp derivative-shaped MCD feature centered at ~556 nm (“the 556-nm ferrous species”). As previously reported for substrate-free oxy-CYP101 [27], this species is most likely a six-coordinate ferrous center of undetermined ligation.

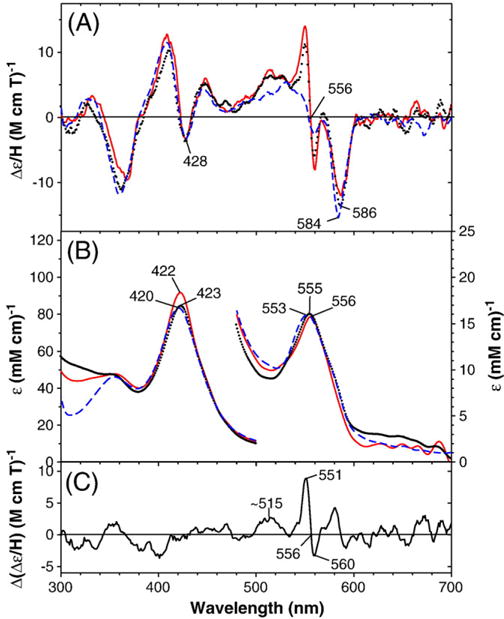

3.2. Substrate-free vs. benzphetamine-bound wild-type oxyferrous CYP2B4

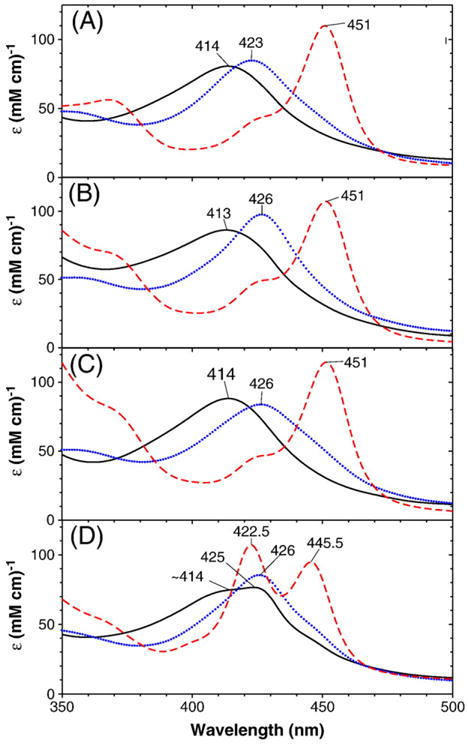

Both substrate-free and benzphetamine-bound deoxyferrous CYP2B4 bind O2 to form stable oxyferrous complexes at ~−50 °C that exhibit Soret absorption peaks at 422–423 nm (Fig. S4), similar to the oxygenase domain of CYP102 (P450 BM3) (with or without arachidonic acid) [25]. However, the substrate-free CYP2B4 oxyferrous complex thus prepared was not quite homogeneous. A close spectral examination shows that the O2 complex of the substrate-free enzyme (Fig. S4, dashed line) contains ~15% ferric enzyme (Fig. S4, dot-dashed line), as judged by the presence of a shoulder (at ~575 nm) next to the visible region MCD trough (at ~586 nm). The shoulder position corresponds to that of a trough (at 573 nm) of the substrate-free ferric enzyme. Calculated electronic absorption and MCD spectra for substrate-free oxy-CYP2B4 corrected for the minor presence of ferric protein are plotted in Fig. S4 (solid line) as well as in Fig. 2 (solid line). Fig. 2A and B also displays the electronic absorption (middle) and MCD (top) spectra of wild-type oxy-CYP2B4 in the presence (dotted line) of 2.5 mM benzphetamine. The benzphetamine-bound oxy-complex is essentially free of the ferric state. Fig. 2 additionally includes corresponding spectra (dashed line) of the oxygen complex of the bacterial enzyme CYP101 [27,29] for comparison.

Fig. 2.

MCD (top) and electronic absorption (bottom) spectra of substrate-free oxy-CYP2B4 (solid red line) (after subtraction of 15% ferric enzyme spectra) and benzphetamine-bound oxy-CYP2B4 (dotted black line) compared with the spectra of camphor-bound oxy-CYP101 (taken from Fig. 2 in Ref. [29]) (dashed blue line). The spectra for P450 CYP2B4 were recorded at −50 °C in a 60/40 (v/v) mixture of glycerol and 0.3 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.7) in the absence and in the presence of 2.5 mM benzphetamine. The difference MCD spectrum of benzphetamine-bound wild-type oxyferrous CYP2B4 minus camphor-bound oxy-CYP101 is shown in (C).

The electronic absorption spectrum of the benzphetamine-bound oxy-CYP2B4 is similar to that of the same complex previously recorded by one of our labs at 15 °C in 15% glycerol-containing aqueous buffer using a stopped-flow rapid scan spectrometer [30]. The MCD spectra of wild-type oxyferrous CYP2B4 in the absence and presence of benzphetamine (2.5 mM) (Fig. 2B, solid and dotted lines, respectively) are almost superimposable. This indicates that the substrate (benzphetamine) has little effect on the MCD and electronic absorption spectra of the oxyferrous complex of the enzyme. Furthermore, the MCD spectrum of the oxy-CYP2B4 enzyme is nearly identical to that of oxy-CYP101 except for a main difference in the region between 500 and 560 nm. In this region, a sharp signal from “the ferrous 556-nm species” appears for the CYP2B4 samples. Apparently the oxy-CYP2B4 samples (with and without the substrate, benzphetamine, bound) contain small amount of six-coordinate ferrous species that does not bind dioxygen. The difference MCD spectrum of benzphetamine-bound wild-type oxyferrous CYP2B4 minus camphor-bound oxy-CYP101 (Fig. 2C) reveals that the only significant difference between the two spectra is in the 540–570 nm region, where six-coordinate ferrous heme complexes exhibit features of such intensity [27] that the presence of well less than 10% of such a component would account for the spectral differences in this region. Difference MCD spectra for the oxy-T302A, E301Q and F429H mutants (see Figs. 3–5) vs. oxy-CYP101 have also been calculated (Fig. S5).

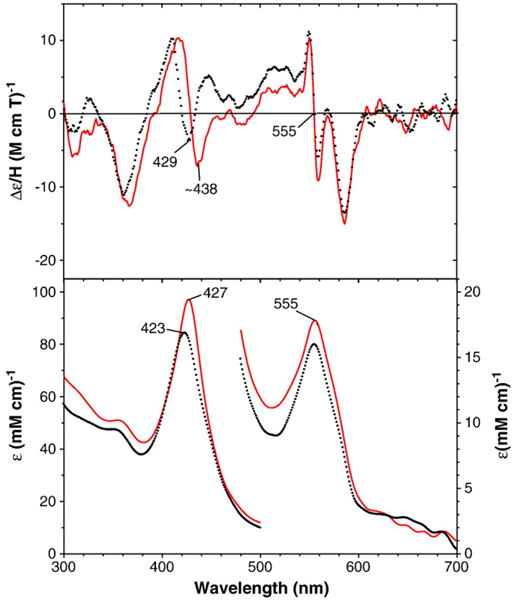

Fig. 3.

MCD (top) and electronic absorption (bottom) spectra of benzphetamine-bound oxy-T302A CYP2B4: T302A mutant (solid red line) and wild-type enzyme (dotted black line) (replotted from Fig. 2). The spectra were recorded at −50 °C in a 60/40 (v/v) mixture of glycerol and 0.3 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.7) in the presence of 2.5 (wild-type) and 4.4 mM (T302A) benzphetamine.

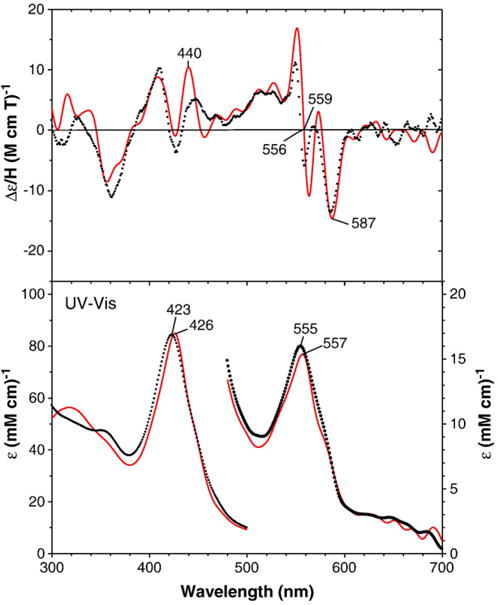

Fig. 5.

MCD (top) and electronic absorption (bottom) spectra of benzphetamine-bound oxy-F429H CYP2B4: F429H mutant (solid red line) and wild-type enzyme (dotted black line) (replotted from Fig. 2). The spectra for the F429H mutant were recorded at −50 °C in a 70/30 (v/v) mixture of glycerol and 0.3 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 8.0) in the presence of 3.0 mM benzphetamine.

3.3. Oxyferrous-T302A, -E301Q and -F29H CYP2B4 mutants

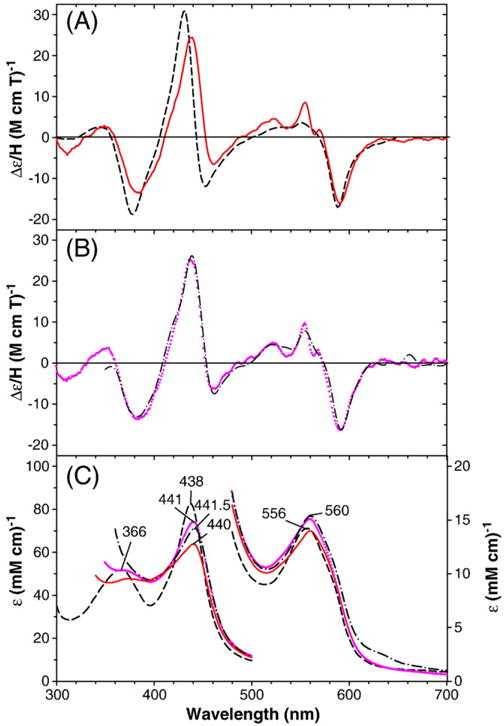

MCD and electronic absorption spectra of the benzphetamine-bound oxy-CYP2B4 T302A, E301Qand F29H mutants are shown in Figs. 3–5, respectively. The corresponding spectra of wild-type CYP2B4 (replotted from Fig. 2) are also overlaid for comparison. The Soret absorption peaks of the T302A (427 nm) and E301Q (426 nm) mutants are red-shifted by 3–4 nm from the corresponding peak position (423 nm) of the wild-type enzyme. The MCD spectrum of the T302A mutant in the Soret region is also red-shifted and has a deeper (by ~2-fold) trough at ~438 nm compared with that (at 428 nm) for the wild-type enzyme (Fig. 2). Furthermore, the positive MCD feature around 445 nm in the wild-type oxyferrous CYP2B4 is missing for the spectrum of oxy-T302A CYP2B4. On the other hand, the overall MCD spectrum of the E301Q mutant in the Soret region is broadly similar to that for the wild-type enzyme except for the enhanced intensity for the 445-nm peak and the less negative value (i.e., an upward-shifted position) for the trough (~422 nm) for the mutant (Fig. 3). In the visible region, the absorption peak position (555–557 nm) and MCD line shape and trough position (587 nm) are similar for the T302A and E301Q mutants as well as the wild-type oxy-ferrous enzyme, although the 587-nm trough is more intense for the E301Q mutant than for the others.

Ferrous low-spin complexes of heme and heme proteins are diamagnetic and expected to exhibit Faraday A term (i.e., symmetric derivative-shaped) MCD spectra that arise from D4h symmetry of the heme iron electronic structure as are the cases of O2 and CO-bound Hb and myoglobin, His-ligated heme proteins [31,32]. However, ferrous low-spin states of thiolate sulfur-ligated heme proteins such as P450s do not provide simple MCD A terms in both the Soret and visible regions (see Fig. 2) [33–35]. And thus it is not easy to interpret the Soret MCD spectral difference between the oxy complexes of wild-type and T302A CYP2B4 (Fig. 3). Nevertheless, based on the present result, we can speculate that the distal Thr302Ala mutation may have caused some significant changes in the electronic structure of the O2-bound heme iron (see below for structural comparison between oxy-T302A CYP2B4 and oxy-T252A CYP101).

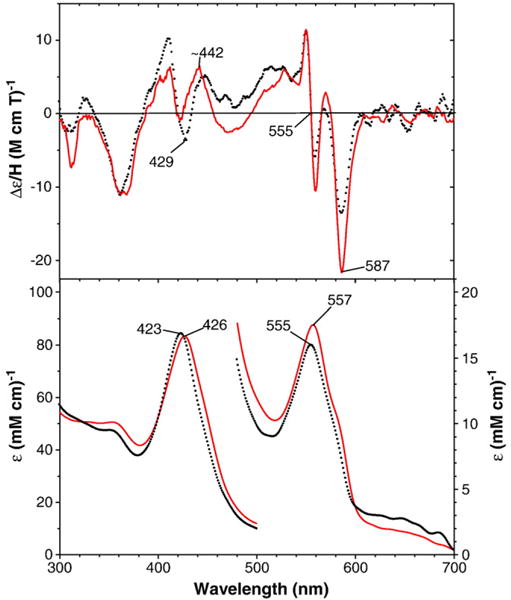

The red-shifted Soret absorption peaks for the T302A and E301Q CYP2B4 mutants are not due to either incomplete O2 binding to the deoxyferrous enzymes or partial autoxidation of the O2 complexes of these mutants since blue shifts rather than red shifts for the Soret absorption peaks would be expected if the O2 complex of the two mutants contained partial deoxyferrous or ferric forms. To examine the possibility that the red-shifted Soret absorption peaks for the oxy-CYP2B4 T302A and oxy-E301Q mutants might have been caused by a loss of protein integrity in the mutant enzymes, we generated ferrous–CO complexes using the same samples as used for the oxy-complex formation. The resulting samples for both the wild-type and for the T302A and E301Q mutants exhibited typical ferrous–CO P450 absorption spectra having Soret peaks at 451 nm. In contrast, the Soret peak for the ferrous–CO F429H mutant is blue-shifted to 446 nm. This spectral shift for the F429H mutant may result from modifications in hydrogen bonding to the proximal Cys436 sulfur such as formation of a new hydrogen bond between the His429 side chain NH group and the axial sulfur as suggested for the corresponding F439H CYP102 (P450 BM3) mutant [36].2 Absorption spectra (350–500 nm) for the wild-type and the three mutants in their deoxyferrous at 4 °C, oxyferrous at −50 °C and CO-bound (25 °C) forms are shown in Fig. 6. These results indicate that the observed spectral differences between the oxyferrous complexes of the wild-type and the two distal side mutants are intrinsic and not caused by loss of protein integrity for the mutants. The spectral properties of the proximal F429H mutant will be discussed separately below.

Fig. 6.

Electronic absorption spectra of deoxyferrous (solid black line) oxyferrous (dotted blue line) and ferrous–CO (dashed red line) forms of P450 CYP2B4 wild-type and three mutants in the presence of benzphetamine. (A) wild-type, (B) T302A, (C) E301Q and (D) F429H. The spectra for the ferrous–CO and deoxyferrous forms were recorded at 4 and 25 °C, respectively, and for the oxyferrous complexes at −50 °C in a 60/40 (v/v) mixture of glycerol and 0.3 M potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.7 in the presence of 2.5 mM(wild-type), 4.4 mM(T302), 3.1 mM(E301Q) and 1.5 mM(F429H). The ferrous–CO complexes were generated by warming up the oxyferrous enzymes to ~25 °C, bubbling with CO gas, and then adding small volume (1–2 μL) of dithionite stock solution. A gradual absorption increase toward the shorter wavelength (300 nm) for the T302A and E301Q mutants that was observed at ambient temperatures due to the slight turbidity caused by benzphetamine (>3 mM) were corrected by subtracting a linear base line with a negative slope from the actually recorded spectra.

The T302A mutant lacks the Thr side chain hydroxyl group that likely participates in hydrogen bonding with the distal (outer) oxygen of the dioxygen bound in the oxy-CYP2B4 complex. The absence of the Thr hydroxyl group hydrogen bond might affect the orientation of the Fe(II)–O–O unit in the T302A mutant as has been postulated for the reduced oxyferrous complexes (i.e., ferric–peroxo and ferric–hydroperoxo species) of CYP2B4 [20,37] and CYP101 [38]. However, it should be noted that in the case of CYP101, the analogous oxy-T252A mutant complex exhibits nearly identical MCD and electronic absorption spectra to those of the oxyferrous wild-type CYP101 [27]. In fact, the orientation and hydrogen bond formation (with water for the mutant and with the Thr hydroxyl group and water for the wild-type enzyme) have been shown by crystal structure analysis to be very similar [39]. Thus the results presented here suggest that unlike the case of CYP101, the interaction of the Fe(II)–O–O unit with its surroundings in the oxyferrous CYP2B4 complex may be somewhat different between the T302A mutant and wild-type enzymes. In both P450 enzymes, these two conserved distal side residues (Thr and Glu/Asp) are thought to control the positioning of water molecules in the active site and thereby manage the critical flow of the two protons needed during catalysis [40,41]. Both mutations also yield more hydrophobic distal heme pocket environments. These factors in combination likely are responsible for the spectral differences seen for the oxyferrous derivatives of these two mutants relative to those of the respective wild-type proteins and, in further combination with the interruption of the proton delivery system, are almost certainly responsible for the major changes in catalytic properties of the two mutants [13].

Electronic absorption and MCD spectra of the benzphetamine-bound oxyferrous F429H mutant are displayed in Fig. 5. Corresponding spectra of wild-type CYP2B4 are included for comparison. Interestingly, this proximal side mutant also exhibits a red-shifted Soret absorption peak at 426 nm in its oxyferrous state (cf. 423 nm for wild-type CYP2B4). In the visible region, oxy-F429H mutant has a slightly red-shifted absorption peak at 557 nm (vs. 555 nm for the wild-type enzyme). The MCD spectrum of the oxyferrous F429H mutant thus generated is quite similar to that of wild-type oxyferrous CYP2B4 and oxy-E301Q CYP2B4 except for more intense peak at ~440 nm and an enhanced derivative-shaped spectral signal centered at ~558 nm for the mutant. However, the oxy-F429H CYP2B4 complex was not as stable as the other two mutants even at −50 °C and the Soret absorption peak shifted from 426 nm to 422 nm in ~1 h although the spectral change was not indicative of autoxidation. Furthermore, the ferrous–CO complex of the F429H mutant sample shows two Soret absorption peaks at ~446 nm and at ~423 nm (Fig. 6D) indicating that the sample contained significant amount (~50%) of a P420 inactive form. Under steady state conditions F429H is only 5% active compared with the wild-type enzyme and P450 not P420 is present at the end of the reaction [37]. Thus, the P420 was likely generated during sample handling.

3.4. Ferric–NO and ferrous–NO complexes of wild-type and mutants of CYP2B4

To investigate whether the spectral shifts observed for the MCD and electronic absorption spectra of the dioxygen complexes of the distal (T302A and E301Q) and proximal side (F429H) CYP2B4 mutants relative to the wild-type enzyme are also seen with another diatomic gas ligand, nitric oxide (NO), we have examined spectroscopic properties of the ferric– and ferrous–NO complexes. As described above, the ferrous–CO complexes of the wild-type enzyme and the two distal side mutants T302A and E301Q do not exhibit any detectable spectral differences except for the proximal side mutant F429H. A ferrous–NO heme complex is known to be more similar to a ferrous–O2 than ferrous–CO complex in the Fe–X–O bonding geometry, i.e., an intrinsically bent (X N or O) vs. linear (X C) bonding mode. On the other hand, a ferric–NO heme complex has a linear structure similar to a ferrous–CO heme species [26].

Results of electronic absorption and MCD spectral examinations show that no significant differences exist among the wild-type and the two distal side mutants, T302A and E301Q in either the ferric– (Fig. S6) or ferrous–NO states (Fig. 7). Both the ferric– and ferrous–NO complexes have Soret and visible absorption peaks that are slightly red-shifted from the corresponding peak positions for ferric– and ferrous–NO CYP101. The electronic absorption and MCD spectra of both the ferric– and ferrous–NO adducts of the F429H CYP2B4 mutant are very similar to the respective forms of the wild-type CYP2B4 enzyme (Fig. S7), except for some blue shifts in the Soret absorption peak positions for the ferric–NO (by 4 nm, 428 vs. 432 nm) and ferrous–NO (by 6 nm, 434 vs. 440 nm) F429HCYP2B4 complexes. These blue shifts may be caused by formation of a new proximal side hydrogen bond as mentioned above for the ferrous–CO F429H CYP2B4 complex case. For the ferrous–NO complexes of both the wild-type and the mutant CYP2B4 enzymes, we again notice that a relatively small extra derivative-shaped MCD feature appears around 560 nm. This feature is similar to that seen in their oxy-complexes (Figs. 2–4) as well as in their dithionite-reduced forms (Fig. S3), but the MCD signal intensities of the feature are considerably smaller for the ferrous–NO complexes than for the other forms. It appears that even the NO ligand, which has much higher affinities than O2 for ferrous heme proteins, cannot completely replace the unknown sixth ligand in the minority six-coordinate ferrous P450 CYP2B4 species. The overall lack of spectral differences between the ferric– and ferrous–NO adduct of the distal side mutants relative to the wild-type enzyme indicates that the electronic structure of the O2 complex is much more sensitive to changes in heme distal pocket polarity and hydrogen bonding than that of the corresponding NO adducts.

Fig. 7.

MCD (A and B) and electronic absorption (C) spectra of benzphetamine-bound ferrous–NO CYP2B4 in comparison to those of camphor-bound ferrous–NO CYP101: (A and C) wild-type CYP2B4 (solid red line) and CYP101 (dashed black line); (B and C) T302A (dash dot black line) and E301Q (purple dotted line) CYP2B4 mutants. The spectra were recorded in 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0 (CYP101) or 7.5 (CYP2B4) at 4 °C in the presence of 1 mM benzphetamine (for CYP2B4). The spectra for CYP101 were taken from Fig. 1A in Ref. [29].

Fig. 4.

MCD (top) and electronic absorption (bottom) spectra of benzphetamine-bound oxy-E301Q CYP2B4: E301Q mutant (solid red) and wild-type enzyme (dotted black line) (replotted from Fig. 2). The spectra were recorded at −50 °C in a 60/40 (v/v) mixture of glycerol and 0.3 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.7) in the presence of 2.5 (wild-type) and 3.1 mM (E301Q) benzphetamine.

4. Conclusions

In this study, we have prepared stable oxyferrous complexes at subzero temperatures (−50 °C or below) for CYP2B4 and its distal and proximal side mutants in the presence and absence of substrate and have extensively characterized their O2, NO and CO adducts using MCD and electronic absorption spectroscopy. As the Fe(II)-dioxygen complex is the last stable intermediate in the P450 reaction cycle, analysis of the sensitivity of its spectroscopic properties to variations in heme pocket polarity and hydrogen bonding may lead to a better understanding of the nature of the subsequent ferric peroxo and ferryl intermediates that are hard to characterize due to their instability. The present results indicate that the active site structural mutations that lead to alterations in the polarity, proton delivery and the positioning of substrate in the distal pocket can sensitively influence the spectroscopic properties (as well as catalytic activities) of the P450 dioxygen complex. The T302A CYP2B4 mutant shows a 1.6 to 2.5-fold increase in peroxide formation (i.e., uncoupling) in the presence of substrate [20]. Furthermore, product formation decreased by 9-fold for benzphetamine [13]. The ability of this mutation to modulate the reactivity of P450 intermediates indicates the involvement of this residue in catalysis. In addition, these spectral changes observed show how these mutations reflect structural variations in dioxygen-bound heme complexes. Mutations such as T302A and E301Qin CYP2B4 that destabilize the distal proton delivery network reveal information about the “pull effect” while the proximal side F429H mutant probes the influence of the “push effect” on spectral and catalytic properties.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Support from the NIH GM 26730 and Research Corp. (to J.H.D.) and from NIH GM 35533 and a V.A. Merit Review (to LW).

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.07.012.

Footnotes

Dedicated to Dr. Klaus Ruckpaul in recognition of his contributions to our knowledge of cytochrome P450 and on the occasion of his 80th birthday.

Because of steric restrictions, up to two or at most three hydrogen-bonds may be feasible involving the P450 heme iron-ligated cysteinate sulfur atom for its sp3 or sp3d hybrid orbital structures, respectively. We have used in this paper the term “hydrogen bond(s)” referring to inter-heteroatom (NH⋯S) interactions within a hydrogen bond distance (~3.5 Å) regardless of the nature (true hydrogen bond or not) of the interactions.

Contributor Information

Roshan Perera, Email: perera@uta.edu.

Masanori Sono, Email: sono@mail.chem.sc.edu.

John H. Dawson, Email: dawson@sc.edu.

References

- 1.Sono M, Roach MP, Coulter ED, Dawson JH. Heme-containing oxygenases. Chem Rev. 1996;96:2841–2887. doi: 10.1021/cr9500500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dawson JH. Probing structure function relations in heme-containing oxygenases and peroxidases. Science. 1988;240:433–439. doi: 10.1126/science.3358128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ortiz de Montellano PR, De Voss JJ. Oxidizing species in the mechanism of cytochrome P450. Nat Prod Rep. 2002;19:477–493. doi: 10.1039/b101297p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guengerich FP. Common and uncommon cytochrome P450 reaction related to metabolism and chemical toxicity. Chem Res Toxicol. 2001;14:611–650. doi: 10.1021/tx0002583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meunier B, de Visser SP, Shaik S. Mechanism of oxidation reactions catalyzed by cytochrome P450 enzymes. Chem Rev. 2004;104:3947–3980. doi: 10.1021/cr020443g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lipscomb JD, Sligar SG, Namtvedt MJ, Gunsalus IC. Autooxidation and hydroxylation reactions of oxygenated cytochrome P-450cam. J Biol Chem. 1976;251:1116–1124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ishimura Y, Ullrich V, Peterson JA. Oxygenated cytochrome-P-450 and its possible role in enzymic hydroxylation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1971;42:140–146. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(71)90373-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Estabrook RW, Hildebrandt AG, Baron CJ, Netter KCJ, Leihman K. A new spectral intermediate associated with cytochrome P-450 function in liver microsomes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1971;42:132–139. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(71)90372-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oprian DD, Gorsky LD, Coon MJ. Properties of the oxygenated form of liver microsomal cytochrome P-450. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:8684–8691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loida PJ, Sligar SG. Molecular recognition in cytochrome P450: mechanism for the control of uncoupling reactions. Biochemistry. 1993;32:11530–11538. doi: 10.1021/bi00094a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Newcomb M, Aebisher D, Shen R, Esala P, Chandrasena R, Hollenberg PE, Coon MJ. Kinetic isotope effects implicate two electrophilic oxidants in cytochrome P450-catalyzed hydroxylations. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:6064–6065. doi: 10.1021/ja0343858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perera R, Jin S, Sono M, Dawson JH. Cytochrome P450-catalyzed hydroxylations and epoxidations. Met Ions Life Sci. 2007;3:319–359. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sheng X, Tarasev M, Im SC, Horner JH, Waskell L, Newcomb M. Kinetics of oxidation of benzphetamine by compounds I of cytochrome P450 2B4 and its mutants. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:2971–2976. doi: 10.1021/ja808982g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Imai M, Shimada H, Watanabe Y, Matsushima-Hibiya Y, Makino R, Koga H, Horiuchi T, Ishimura Y. Uncoupling of the cytochrome CYP101 monooxygenase reaction by a single mutation, threonine-252 to alanine or valine — a possible role of the hydroxyl amino-acid in oxygen activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:7823–7827. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.20.7823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martinis SA, Atkins WM, Stayton PS, Sligar SG. A conserved residue of cytochrome P450 is involved in heme oxygen stability and activation. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:9252–9253. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scott EE, White MA, He YA, Johnson EF, Stout CD, Halpert JR. Structure of mammalian cytochrome P450 2B4 complexed with 4-(4-chlorophenyl)imidazole at 1.9-Å resolution. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:27294–27301. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403349200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Macdonald ID, Smith GC, Wolf CR, Smith WE. Observation of structural variation and spin state conversion of cytochrome P450 CYP2B4 on binding of sterically different substrates. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;226:51–58. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoshioka S, Tosha T, Takahashi S, Ishimori K, Hori H, Morishima I. Roles of the proximal hydrogen bonding network in cytochrome P450cam-catalyzed oxygenation. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:14571–14579. doi: 10.1021/ja0265409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Auclair K, Moenne-Loccoz P, Ortiz de Montellano P. Roles of the proximal heme thiolate ligand in cytochrome P450(cam) J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:4877–4885. doi: 10.1021/ja0040262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vaz AD, Pernecky SJ, Raner GM, Coon MJ. Peroxo–iron and oxenoid–iron species as alternative oxygenating agents in cytochrome P450-catalyzed reactions: switching by threonine-302 to alanine mutagenesis of cytochrome P450 2B4. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:4644–4648. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.10.4644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Macdonald IDG, Sligar SG, Christian JF, Unno M, Champion PM. Identification of the Fe–O–O bending mode in oxycytochrome P450cam by resonance Raman spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:376–380. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davydov R, Perera R, Jin S, Yang TC, Bryson TA, Sono M, Dawson JH, Hoffman BM. Substrate modulation of the properties and reactivity of the oxy-ferrous and hydroperoxo–ferric intermediates of cytochrome P450cam as shown by cryoreduction-EPR/ENDOR spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:1403–1413. doi: 10.1021/ja045351i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Omura T, Sato R. The carbon monoxide-binding pigment of liver microsomes. 1. Evidence for its hemoprotein nature. J Biol Chem. 1964;239:2370–2378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huff AM, Chang CK, Cooper DK, Smith KM, Dawson JH. Imidazole- and alkylamine-ligated iron (II, III) chlorin complexes as models for histidine and lysine coordination to the iron in dihydroporphyrin-containing proteins: characterization with magnetic circular dichroism spectroscopy. Inorg Chem. 1993;32:1460–1466. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perera R, Sono M, Raner GM, Dawson JH. Subzero-temperature stabilization and spectroscopic characterization of homogeneous oxyferrous complexes of the cytochrome P450 BM3 (CYP102) oxygenase domain and holoenzyme. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;338:365–371. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.08.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Voegtle HL, Sono M, Adak S, Pond AE, Tomita T, Perera R, Goodin DB, Ikeda-Saito M, Stuehr DJ, Dawson JH. Spectroscopic characterization of five- and six-coordinate ferrous–NO heme complexes. Evidence for heme Fe-proximal cysteinate bond cleavage in the ferrous–NO adducts of the Trp-409Tyr/Phe proximal environment mutants of neuronal NOS. Biochemistry. 2003;42:2475–2484. doi: 10.1021/bi0271502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sono M, Perera R, Jin S, Makris TM, Sligar SG, Bryson TA, Dawson JH. The influence of substrate on the spectral properties of oxyferrous wild-type and T252A cytochrome P450-CAM. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2005;436:40–49. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dawson JH, Sono M. Cytochrome P450 and chloroperoxidase: thiolate-ligand heme enzymes. Spectroscopic determination of their active site structures and mechanistic implications of thiolate ligation. Chem Rev. 1987;87:1255–1276. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sono M, Eble KS, Dawson JH, Hager LP. Preparation and properties of ferrous chloroperoxidase complexes with dioxygen, nitric oxide, and an alkyl isocyanide. Spectroscopic dissimilarities between the oxygenated forms of chloroperoxidase and cytochrome P-450. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:15530–15535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang H, Gruenke L, Arscott D, Shen A, Kasper C, Harris DL, Glavanovich M, Johnson R, Waskell L. Determination of the rate of reduction of oxyferrous cytochrome P450 2B4 by 5-deazariboflavin adenine dinucleotide T491V cytochrome P450 reductase. Biochemistry. 2003;42:1594–11603. doi: 10.1021/bi034968u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vickery L, Nozawa T, Sauer K. Magnetic circular dichroism studies of myoglobin complexes. Correlations with heme spin state and axial ligation. J Am Chem Soc. 1976;98:343–350. doi: 10.1021/ja00418a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamamoto T, Nozawa T, Kato A, Hatano M. Experimental and calculated magnetic circular dichroism spectra of iron(II) low spin hemoglobin and myoglobin with CO, NO, and O2. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 1982;55:2021–2025. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dawson JH, Cramer SP. Oxygenated cytochrome P-450CAM — evidence against axial histidine ligation of iron. FEBS Lett. 1978;88:127–130. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(78)80623-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dawson JH, Andersson LA, Sono M. The diverse spectroscopic properties of ferrous cytochrome-P-450-CAM ligand complexes. J Biol Chem. 1981;258:3637–3645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shimizu T, Iizuka T, Shimada H, Ishimura Y, Nozawa T, Hatano M. Magnetic circular-dichroism studies of cytochrome P-450cam. Characterization of axial ligands of ferric and ferrous low-spin complexes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1981;670:341–354. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(81)90106-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ost TWB, Clark J, Mowat CG, Miles CS, Walkinshaw M, Reid GA, Chapman SK, Daff S. Oxygen activation and electron transfer in flavocytochrome P450 BM3. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:15010–15020. doi: 10.1021/ja035731o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Davydov R, Razeghifard R, Im SC, Waskell L, Hoffman BM. Characterization of the microsomal cytochrome P4502B4 O2 activation intermediates by cryoreduction and electron paramagnetic resonance. Biochemistry. 2008;36:9661–9666. doi: 10.1021/bi800926x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davydov R, Makris TM, Kofman V, Werst DE, Sligar SG, Hoffman BM. Hydroxylation of camphor by reduced oxy-cytochrome P450cam: mechanistic implications of EPR and ENDOR studies of catalytic intermediates in native and mutant enzymes. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;13:1403–1415. doi: 10.1021/ja003583l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nagano S, Poulos TL. Crystallographic study on the dioxygen complex of wild-type and mutant cytochrome P450cam. Implications for the dioxygen activation mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:31659–31663. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505261200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harris DL, Jin-Young P, Gruenke L, Waskell L. Theoretical study of the ligand-CYP2B4 complexes: effect of structure on binding free energies and heme spin state. Proteins Struct Funct Bioinf. 2004;55:895–914. doi: 10.1002/prot.20062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schlichting I, Berendzen J, Chu K, Stock AM, Maves SA, Benson DE, Sweet RM, Ringe D, Petsko GA, Sligar SG. The catalytic pathway of cytochrome P450cam at atomic resolution. Science. 2000;287:1615–1622. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5458.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.