Abstract

The population health impact and cost-effectiveness of implementing intensive blood pressure blood pressure goals in high cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk adults have not been described.

Using the CVD Policy Model, CVD events, treatment costs, quality adjusted life years (QALYs), and drug and monitoring costs were simulated over 2016 to 2026 for hypertensive patients aged 35 to 74 years. We projected the effectiveness and costs of hypertension treatment according to the 2003 Joint National Committee (JNC)-7 or 2014 JNC8 guidelines, and then for adults ≥50 years, we assessed the cost-effectiveness of adding an intensive goal of systolic blood pressure <120 mmHg for patients with CVD, chronic kidney disease, or 10-year CVD risk ≥15%. Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios <$50,000 per quality-adjusted life years gained were considered cost-effective.

JNC7 strategies treat more patients and are more costly to implement compared with JNC8 strategies. Adding intensive systolic blood pressure goals for high-risk patients prevents an estimated 43,000 and 35,000 annual CVD events incremental to JNC8 and JNC7, respectively. Intensive strategies save costs in men and are cost-effective in women compared with JNC8 alone. At a willingness-to- pay threshold of $50,000 per quality-adjusted life years gained, JNC8+intensive had the highest probability of cost-effectiveness in women (82%), and JNC7+intensive the highest probability of cost-effectiveness in men (100%). Assuming higher drug and monitoring costs, adding intensive goals for high-risk patients remained consistently cost-effective compared in men, but not always in women.

Amongst patients aged 35 to 74 year olds, adding intensive blood pressure goals for high-risk groups to current national hypertension treatment guidelines prevents additional CVD deaths while saving costs, provided that medication costs are controlled.

Keywords: cardiovascular diseases, cost-benefit analysis, hypertension, guideline, policy

Introduction

For ≈four decades, the Joint National Committee (JNC) on the Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (BP) supported formulation of US hypertension treatment guidelines. From 1977 to 2003 (JNC1 to JNC7), the guidelines progressively lowered diagnostic thresholds and treatment targets, effectively expanding the treatment-eligible population. The 2014 hypertension guidelines (referred to here as JNC8) recommended higher BP goals compared with JNC7, so that ≈5.8 million fewer adults were eligible for antihypertensive medication treatment. JNC8’s less intensive BP goal recommendations for patients ≥60 years and those with diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney disease (CKD) provoked controversy and uncertainty. More recently, the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) found that targeting an intensive systolic BP (SBP) goal of 120 mm Hg in patients with high cardiovascular disease CVD risk and baseline SBP ≥130 mmHg reduced CVD events by 25% and all-cause mortality by 27%, compared with a 140 mm Hg goal.

The objective of this study was to project the potential value of adding intensive systolic BP goals in high-risk patients to the JNC7 or JNC8 guidelines in a contemporary population of untreated hypertensive individuals aged 35 to 74 years. We also assessed if the incremental cost-effectiveness of intensive SBP goals remained sensitive to the costs of more frequent monitoring or high medication prices. Patients aged ≥75 years were excluded from this analysis because of uncertainty about the trade-off of risks and benefits of antihypertensive therapy in that population.

Methods

CVD Policy Model

The CVD Policy Model is a computer-simulation, state-transition (Markov cohort) model of incidence, prevalence, mortality, and costs of CVD in US adults (Methods section in the online-only Data Supplement). Means or proportions and joint distributions of risk factors, including BP, cholesterol, hypertension medication use, smoking, diabetes mellitus, and CKD status, were estimated from pooled National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) 2007 to 2010. Default multivariate stroke and coronary heart disease incidence functions were estimated in original Framingham Heart Study analyses.

The CVD Policy Model predicts life years, CVD events (myocardial infarction and stroke), coronary revascularization procedures, CVD mortality (stroke [International Classification of Diseases-10 codes I60-I69], coronary heart disease [I20-I25 and two-thirds of I49, I50, and I51], hypertensive heart disease deaths [I11.0, I11.9], and non- CVD deaths (remainder of International Classification of Diseases codes). Reductions in heart failure deaths because of hypertension treatment were calculated by adding prevented ischemic heart failure deaths (I50 with coronary heart disease) and hypertensive heart disease deaths (I11.0, I11.9; Methods section in the online-only Data Supplement).

Model Calibration and Validation

Default model input parameters were calibrated, so that 2010 coronary heart disease and stroke incidence predictions matched hospitalized myocardial infarction and stroke rates observed in the 2010 National Hospital Discharge Survey, and mortality predictions were within 1% of age-specific 2010 CVD vital statistics mortality rates. Age- and sex-specific systolic SBP and diastolic BP β-coefficients from the Prospective Studies Collaboration were calibrated so that CVD Policy Model age-weighted relative risks with BP reduction fell within the 95% confidence interval of the overall relative risk estimates for the same BP reduction observed in a large meta-analysis of randomized controlled hypertension treatment trials (Methods section in the online-only Data Supplement; Tables S1-S3 in the online-only Data Supplement). To test predictive validity, we populated the model with the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP) trial cohort and simulated the BP reduction achieved in the active treatment arm of the trial for 5-years of follow up. Our estimates accurately reproduced the risk reduction observed in the original trial (Table 1; Methods section in the online-only Data Supplement; Table S4).

Table 1.

Main assumptions for the comparative effectiveness analysis of adding intensive blood pressure goals for high risk patients to current U.S. hypertension treatment guidelines

| Variable | Estimate (range in main estimate if a variation assumed according to age and/or sex) | Sources | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main | Lower | Upper | ||

| Effectiveness | ||||

| Average RR per 5 mmHg reduction in DBP or 10 mmHg reduction in SBP, ages 35-59 years* | Law meta-analysis8 | |||

| CHD | 0.74 (0.71—0.77) | 0.71 (0.66—0.75) | 0.78 (0.76—0.79) | |

| Stroke | 0.66 (0.62—0.70) | 0.61 (0.56—0.67) | 0.71 (0.69—0.73) | |

| All-cause mortality | 0.89 (0.83—0.89) | 0.78 | 0.95 | |

| Average RR per 10 mmHg reduction in SBP or 5 mmHg reduction in DBP, ages 60-74 years* | Law meta-analysis8,10 | |||

| CHD | 0.78 (0.76—0.81) | 0.76 (0.74—0.78) | 0.80 (0.79—0.83) | |

| Stroke | 0.71 (0.69—0.77) | 0.68 (0.66—0.70) | 0.77 (0.73—0.84) | |

| All-cause mortality | 0.92 | 0.81 | 1.02 | |

| Average SBP lowering effect (mmHg) † | Law meta-analysis8,10 | |||

| Stage 2 hypertension | ||||

| Pretreatment ≥ 160 mmHg, JNC7 diabetes and/or CKD target 130 mmHg or Intensive Intervention in Age ≥ 50 years with existing CVD, CKD and/or CVD risk ≥15% target 120 mmHg (4-5 standard dose medications) | 38.4—42.3 | 32.8—42.3 | 44.0—48.3 | |

| JNC8 Age <60 years or JNC7 no risk factors, pretreatment ≥ 160 mmHg target 140 mmHg, 3-4 standard dose medications | 31.0—34.7 | 26.0—29.4 | 36.0—39.9 | |

| JNC8 Age ≥60 years, pretreatment ≥ 160 mmHg target 150 mmHg, 2-3 standard dose medications | 22.1—24.2 | 18.1—18.9 | 27.2—29.2 | |

| Stage 1 hypertension | ||||

| JNC7 diabetes and/or CKD, pretreatment 140-159 mmHg target 130 mmHg, 2-3 standard dose medications | 16.1—19.2 | 11.7—15.2 | 19.3-25.1 | |

| JNC8 Age <60 years or JNC7 no risk factors, pretreatment 140-159 mmHg target 140 mmHg, 0.5-2.0 standard dose medications | 7.9—10.9 | 5.9—8.3 | 9.9—13.4 | |

| Age ≥60 years, pretreatment 150-159 mmHg target 150 mmHg, 0.5 standard dose medications | 7.1 | 3.2 | 11.0 | |

| Intensive Intervention in age ≥ 50 years with existing CVD, CKD and/or Framingham risk ≥15% Pretreatment ≥ 130 mmHg, target 120 mmHg | 25.5-29.0 | 22.6-25.8 | 28.3-32.1 | |

| Pre-Hypertension | ||||

| JNC7 diabetes and/or CKD, pretreatment 130-139 mmHg target 130 mmHg, 0.5 standard dose medications | 6.7 | 4.7 | 8.7 | |

| DBP lowering effect (mmHg)b | Law meta-analysis8 | |||

| Stage 2 hypertension | ||||

| JNC7 diabetes and/or CKD, pretreatment ≥ 100 mmHg target 80 mmHg, 3 standard dose medications | 19.2—21.2 | 16.2-17.9 | 22.2-24.4 | |

| JNC8 all ages, JNC7 no risk factors, stage 2 hypertension (≥ 100 mmHg), target 90 mmHg, 1-2 standard dose medications | 15.5—17.4 | 12.9-14.6 | 18.1-20.2 | |

| Stage 1 hypertension | ||||

| JNC7 diabetes and/or CKD, pretreatment ≥ 90 mmHg target 80 mmHg, 1-2 standard dose medications | 8.0—9.6 | 6.4-7.7 | 9.7-11.5 | |

| JNC8 all ages, JNC7 no risk factors, stage 1 hypertension (90-99 mmHg), target 90 mmHg, 1 standard dose medications | 4.5—5.9 | 3.3-4.5 | 5.7-7.4 | |

| Pre-hypertension | ||||

| JNC7 diabetes and/or CKD, pre-hypertension (80-89 mmHg), target 80 mmHg, 0.5 standard dose medications | 3.4 | 2.3 | 4.4 | |

| JNC7 diabetes and/or CKD target 130 mmHg or Intensive Intervention in Age ≥ 50 years with existing CVD, CKD and/or CVD risk ≥15% target 120 mmHg | 13.7 | 9.6 | 17.8 | |

| Annual costs per person treated (2010 costs; inflated to 2014 costs in all results) | ALLHAT trial;29 JNC7 recommendation | |||

| MD office visit | ||||

| Treatment monitoring visits (number) | ||||

| Stage 2 hypertension | 4 | 3 | 5 | Outpatient visit, Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (code 99213, non-facility limiting charge)30 |

| Stage 1 hypertension | 3 | 2 | 4 | |

| Cost per routine monitoring visit | $71 | Not modeled | Not modeled | |

| Hospitalization | ||||

| Average cost (used for infrequent hospitalized drug-related adverse events) | $11,994 | Not modeled | Not modeled | National Inpatient Sample survey |

| High cost (used for rare hospitalized drug-related adverse events) | $20,680 | |||

| Laboratory test (electrolytes monitoring on treatment) | JNC7 | |||

| Number of tests | 1 | 1 | 2 | Centers for Medicare and Medicaid laboratory fee schedule31 |

| Cost per test | $15 | Not modeled | Not modeled | |

| Antihypertensive drug costs (total daily doses)‡ | Average wholesale prices reported by manufacturers (“Red Book”; 2010)32 | |||

| 0.5 standard doses | $120 | Not modeled | $287 | |

| 1.0 standard dose | $161 | $351 | ||

| 1.5 standard doses | $208 | $4395 | ||

| 2.0 standard doses | $231 | $5548 | ||

| 3.0 standard doses | $346 | $822 | ||

| 3.5 standard doses | $418 | $1,268 | ||

| 4.0 standard doses | $481$27 | $1,329 | ||

| Pharmacy dispensing fees | $33 | |||

| Acute and chronic CVD treatment costs | California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPD) hospital data, 2008.33 | |||

| Myocardial infarction hospitalization | ||||

| Nonfatal | $33,000 | |||

| Fatal | $46,000 | |||

| Coronary revascularization procedures | ||||

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | $21,000--$23,000 | |||

| Coronary artery bypass graft surgery | $57,000--$59,000 | |||

| Stroke | ||||

| Fatal | $21,000--$26,000 | U.S. Medical Expenditure Panel (MEPS) 1998-200834 | ||

| Nonfatal | $15,000--$21,000 | |||

| Chronic CHD costs | ||||

| First year | $11,000 | |||

| Subsequent years | $2,000 | |||

| Chronic post-stroke costs | ||||

| First year | $16,000 | |||

| Subsequent years | $5,000 | |||

| Inflation from 2010 to 2014 costs | 9% | Main = change in general U.S. consumer price index | ||

| Serious adverse effects of medications (incidence per 100,000 person-years) | ||||

| Common, outpatient management | Law 20038,10 | |||

| Three-standard doses | 10,039.20 | 6,950.21 | 12,742.06 | |

| Two-standard doses | 7,572.41 | 5,242.43 | 9,611.13 | |

| One-standard dose | 5,200.00 | 3,600.06 | 6,600.00 | |

| One-half dose | 2,600.00 | 1,800.00 | 3,300.00 | |

| Infrequent, hospitalized | Trials, medication labels, post-marketing reports | |||

| Three-standard doses | 193.06 | 19.31 | 965.31 | |

| Two-standard doses | 145.62 | 14.56 | 728.12 | |

| One-standard dose | 100.00 | 10.00 | 500.00 | |

| One-half-standard dose | 50.00 | 5.00 | 250.00 | |

| Rare, hospitalized/severe | ||||

| three-standard doses | 1.93 | 0.0193 | 19.31 | |

| two-standard doses | 1.46 | 0.0146 | 14.56 | |

| one-standard dose | 1.00 | 0.0100 | 10.00 | |

| one-half-standard dose | 0.50 | 0.0050 | 5.00 | |

| Death | ||||

| three-standard doses | 0.0193 | 0.0002 | 0.1931 | |

| two-standard doses | 0.0146 | 0.0001 | 0.1456 | |

| one-standard dose | 0.0100 | 0.0001 | 0.1000 | |

| one-half-standard dose | 0.0050 | 0.0001 | 0.0500 | |

| Utility [QALY weight penalty (where 1.00=perfect health), duration] | ||||

| Drug side effects managed as outpatient (1d) | 0.23 | Montgomery35 | ||

| Drug side effect requiring hospitalization (1d) | 0.50 | Clinical judgment | ||

| Acute stroke (1 m) | 0.86 | GBD 2010 Study36 | ||

| Chronic stroke survivors (12 m) | 0.85—0.88 | |||

| Acute myocardial Infarction (1 m) | 0.91 | |||

| Acute unstable angina (1 m) | 0.95 | |||

| Chronic CHD (12 m) | 0.91—0.98 | |||

| Death | 1.00 | |||

| Adherence to medications (percent of patients continuing prescribed treatment) | 75% | 25% or 50% lower than observed in trials | Not modeled | Law meta-analysis for main estimate8,10 |

RR reductions vary by age and sex category, see Methods and Appendix for details

BP Change dependent on age- and sex-specific distribution of baseline blood pressures within stage 1 or stage 2 category and number of standard dose antihypertensive medications

Standard dose medications used to estimate costs: captopril 25 mg twice daily, nifedipine 30 mg daily, amlodipine 5 mg daily, hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg daily, and atenolol 50 mg daily.

Abbreviations: CVD Cardiovascular Disease; Coronary Heart disease (CHD); Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD); DBP Diastolic Blood Pressure; JNC Joint National Committee; RR Relative Risk; SBP Systolic Blood Pressure

Model Inputs

JNC7 recommended a goal BP <130/80 mmHg for diabetes mellitus or CKD; BP <140/90 mm Hg for all others. JNC8 recommended a goal <140/90 mmHg for diabetes mellitus or CKD, diastolic BP <90 mmHg if is age <60 years, and BP <150/90 mmHg if age is ≥ 60 years and without diabetes mellitus or CKD. On the basis of SPRINT, intensive interventions were applied to adults aged 50 years with pretreatment SBP ≥130 mm Hg and either existing CVD, CKD, or 2013 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Pooled Cohorts 10-year CVD risk ≥15%. Using these categories and BP and treatment status information from NHANES, we estimated the number of currently untreated U.S. adults eligible for treatment under JNC7 and JNC8 with and without the intensive intervention in selected high CVD risk individuals (Table S5).

BP change caused by antihypertensive medications was determined by pre-treatment BP and the number of standard doses of medications needed to reach the guideline BP goal, according to a trials-based formula. BP changes were calculated based on pre-treatment BP, age, and sex. We assumed the same BP reduction per standard dose of the main drug classes and did not include non-BP lowering benefits of specific agents (Table 1; Methods section in the online-only Data Supplement; Table S5).

We expected that CVD risk is reduced log-linearly in relation to BP reduction (mm Hg) down to SBP 120 mm Hg in high-CVD risk patients in intensive strategies, 130/80 mm Hg in select JNC7 groups (diabetes mellitus or CKD), and SBP 140 mm Hg in those aged 60 to 74 years but without diabetes mellitus or CKD. Hypertension treatment costs included monitoring, side effect, and averaged wholesale drug costs. Quality of life penalties were applied for side effects. A medication adherence rate of 75% estimated in a meta-analysis of clinical trials was assumed because it corresponded to risk reduction associated with treatment estimated in the same meta-analysis (Table 1).

A status quo simulation projected CVD events, CVD deaths, heart failure deaths, costs, and quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) for adults aged 35 to 74 years with untreated hypertension from 2016 to 2026. Adults aged ≥75 years were excluded from this analysis because of variable medication related adverse event risk in this group. Guideline simulations modeled treatment according to JNC7 or JNC8. Incremental to JNC7 or JNC8, intensive strategies targeted an SBP 120 mm Hg goal in high CVD risk patients, limiting to 5 antihypertensive drugs maximum. Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) were calculated as change in costs divided by incremental change in QALYs. ICERs < $50 000 per QALY gained were considered cost-effective, ≥ $50 000 and < $150 000 of intermediate value, and ≥ $150 000 of low value. All analyses were approached from a payer’s perspective. Future costs and QALYs were discounted at 3% per year.

Subgroup and sensitivity analyses

JNC7 and JNC8 with and without intensive treatment in selected high-CVD risk individuals were compared within age groups. One-way sensitivity analyses assessed cost-effectiveness assuming lower and upper uncertainty boundaries of the main inputs, including increased monitoring costs for the intensified treatment strategies (Table 1). We also modeled medication adherence as low as 40%. Main analyses did not include patients with treated but uncontrolled hypertension, because it was not clear what proportion of poor control was because of under-use of combination therapy, poor adherence, or resistant hypertension.6 Nonetheless, we repeated the analyses in the entire population with uncontrolled hypertension, including previously treated and uncontrolled hypertension.

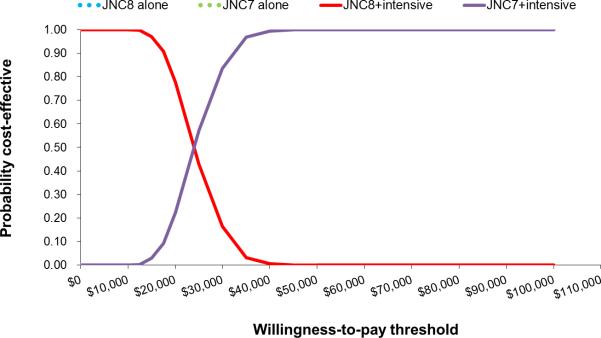

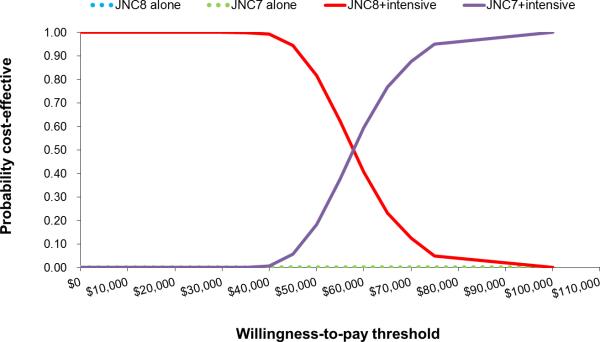

Probabilistic Analyses

Probabilistic (Monte Carlo) simulation sampled across uncertainty distributions of antihypertensive drug BP-lowering effectiveness, CVD relative risk reduction with treatment, quality of life penalties and costs related to side effects, and drug and monitoring costs. Uncertainty distributions were randomly sampled 1,000x, and 95% uncertainty intervals were calculated for all model outputs. Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves were constructed in order to illustrate the probability that each hypertension treatment strategy would be cost-effective at different willingness-to-pay thresholds.

Results

Main and probabilistic results

Compared with no treatment, JNC8 would increase the annual number of newly treated adults aged 35 to 64 years by ≈ 12 million and would avert ≈ 65 000 CVD events and 17 000 CVD deaths annually. Compared with JNC 8, JNC7 would recommend treatment for nearly twice the number of untreated patients (21 million) and add substantial treatment costs, but would avert 24 000 additional CVD events and 5000 additional CVD deaths annually (Table 2). Incremental to JNC8, JNC8 plus intensive treatment in selected high-risk groups (JNC8+intensive) would prevent 43 000 additional annual CVD events and 15 000 CVD deaths. Incremental to JNC7, JNC7+intensive would lead to 35 000 fewer annual CVD events and 14 000 fewer CVD deaths. Total annual heart failure deaths avoided ranged from ≈2,000 under JNC8 alone to t ≈4000 under JNC7+intensive (Table S6 in the online-only Data Supplement). In men, implementing JNC7 in addition to JNC8 would be cost-effective (ICER ≈$7,000 per QALY gained; Table 2). Incremental to JNC8, JNC8 plus intensive treatment. In selected high-risk groups (JNC8+intensive) would prevent 43 000 additional annual CVD events and 15 000 CVD deaths. Incremental to JNC7, JNC7+intensive would lead to 35 000 fewer annual CVD events and 14 000 fewer CVD deaths. Total annual heart failure deaths avoided ranged from ≈2000 under JNC8 alone to ≈4000 under JNC7+intensive (Table S6 in the online-only Data Supplement).

Table 2.

Annual population and cost-effectiveness of implementing national hypertension guidelines with and without intensive treatment of high CVD risk individuals: deterministic analysis results.

| Strategy | Annual Number eligible for treatment (millions) | Annual CVD events averted (vs. JNC8) (95% UI) | Annual CVD deaths averted (vs. JNC8) (95% UI)† | Annual QALYs Gained (vs. JNC8) (95% UI) | Annual costs (millions of $US) (vs. JNC8) (95% UI) | ICER (vs. JNC8) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males Age 35-74 years | ||||||

| JNC 7 | 13.3 | −15,000 (−4,000 to −27,000) | −3,000 (−400 to −6,000) | 28,400 (11,000 to 47,000) | +$190 (−$1000 to +$1300) | $7,000/QALY gained |

| JNC 8+ intensive treatment in high CVD risk* | 11.2 | −29,000 (−17,000 to −47,000) | −11,000 (−2,000 to −18,000) | 40,100 (23,000 to 47,000) | −$1240 (−$3,000 to −$200) | cost-saving |

| JNC 7 + intensive treatment in high CVD risk* | 16.2 | −39,000 (−23,000 to −55,000) | −13,000 (−7,000 to −16,000) | 59,500 (36,000 to 85,000) | −$1030 (−$3000 to +$300) | cost-saving |

| Females Age 35 -74 years | ||||||

| JNC 7 | 9.5 | −9,000 (−2,000 to −17,000) | −2,000 (−4,000 to +76) | 17,500 (7,000 to 30,000) | +$920 (+$200 to +$1500) | $52,000/QALY gained |

| JNC 8 + intensive treatment in high CVD risk* | 6.3 | −14,000 (−5,000 to −23,000) | −4,000 (−2000 to −6000) | 14,500 (4,000 to 28,000) | −$290 (−$1400 to +$200) | cost-saving |

| JNC 7 + intensive treatment in high CVD risk* | 13.5 | −20,000 (−11,000 to −31,000) | −6,000 (−3,000 to −8,000) | 29,200 (16,000 to 44,000) | +$600 (−$500 to +$1300) | $21,000/QALY gained |

Intensive treatment is defined as an SBP goal of <120 mmHg in adults aged 50 years and older with SBP ≥ 130 mmHg and existing CVD, chronic kidney disease and/or 2013 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Pooled Cohorts 10-year CVD risk ≥15%.

Overall CVD death includes heart failure deaths. As heart failure deaths were estimated not simulated, 95% UI do not account for heart failure deaths.

CS cost saving; CVD Cardiovascular Disease; ICER Incremental Cost-Effectiveness Ratio; JNC Joint National Committee; QALY Quality adjusted life years; ICER <$50,000 per QALY gained is considered cost-effective; SBP Systolic Blood Pressure

In men, implementing JNC7 in addition to JNC8 would be cost-effective (ICER, ≈$7000 per QALY gained; Table 2). Incremental to JNC8, JNC7+intensive and JNC8+instensive strategies would be cost saving in men aged 35 to 74 years. At a willingness to pay threshold of $50 000 per QALY gained, the probability JNC7+intensive was more cost-effective than any other strategy in men was 100% (Figure 1, cost-effectiveness acceptability curve). At a lower willingness to pay threshold of <$25 000, JNC8+intensive was more likely to be cost-effective than the JNC7+instensive strategy (>50%, probability more cost-effective). In women, JNC7 was borderline cost-effective compared with JNC8 (≈$52 000 per QALY gained). Adding intensive treatment of high-risk patients was cost-effective in women in women incremental to JNC8. At a willingness-to-pay threshold of $50 000 per QALY gained, the probability that JNC8+intensive was the most cost-effective strategy for women was 81.7%, whereas the probability that the JNC7+intensive strategy most cost-effective was 18.3% (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves for the probability of selecting JNC7 over JNC8+intensive treatment in high risk males age 35-74 years ( ≥50 years old with one of the following: existing cardiovascular disease (CVD), 2013 AHA/ACC Pooled Cohorts 10-year CVD risk ≥15% or chronic kidney disease)

Figure 2.

Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves for the probability of selecting JNC7 over JNC8+intensive treatment in high risk females age 35-74 years ( ≥50 years old with one of the following: existing cardiovascular disease (CVD), 2013 AHA/ACC Pooled Cohorts 10-year CVD risk ≥15% or chronic kidney disease)

Subgroup Analyses

Incremental to JNC8, JNC7 would be cost-saving in men aged 60 to 74 years, cost-effective in men aged 45 to 59 years (ICER, ≈15 000 per QALY gained) and in women aged 60 to 74 years (ICER, ≈ 30 000 per QALY gained), but of intermediate and low value in men and women aged 35 to 44 years old, respectively. Incremental to JNC8 alone, JNC8+intensive would be cost saving in all age groups, whereas JNC7+intensive would be cost-saving in all men and women aged 60 to 74 years old, but cost-effective in women aged 45 to 59 years old (ICER, 44 000 per QALY gained; Table S7).

Sensitivity Analyses

Assuming 20% less CVD risk reduction per BP change (in mm HG), more frequent monitoring plus double the drug costs, or 40% medication adherence, adding JNC 8+ intensive or JNC7+intensive remained cost-saving or cost-effective in most instances (ICERs ,$50 000; Table S8). High drug costs plus higher monitoring frequency or 40% adherence made JNC7+intensive of intermediate or low value in women. JNC7 alone was sensitive to high drug costs incremental to JNC8. Adding treatment of treated but uncontrolled hypertension would double the population eligible for treatment to BP control under all strategies and lead to 60 000 to 91 000 fewer CVD events with intensive strategies compared to JNC8 alone. ICERs for the comparison of JNC7 versus JNC8 with and without intensive strategies remained similar when the previously treated and uncontrolled group was added (Table S9).

Discussion

We projected that adding intensive strategies to JNC hypertension treatment guidelines would be cost-saving in men and cost-effective in women aged 35 to 74 years, which held true even in the event of higher monitoring costs. From a payer’s perspective, JNC8+intensive would most likely be the highest value strategy in women, whereas JNC7+intensive would most likely be the highest value strategy for men.

The committee appointed by the JNC8 recommended an SBP target of 150 mmHg amongst individuals aged 60 years and older and a target of 140 mm Hg for patients with diabetes mellitus or CKD, based on selected hypertension medication treatment trials. SPRINT results were released after the JNC8 published its recommendations, and suggested greater CVD benefit from SBP goal of 120 mmHg, as opposed to 140 mmHg in patients at high CVD risk. SPRINT reinforced evidence favoring a lower BP goal in selected high-risk patients. Concerns about the risks of intensive treatment persist. The bulk of randomized trial evidence demonstrates reduction in major CVD events, renal outcomes, and retinopathy from BP lowering well below the 140/90 mm Hg threshold without clear effects on CVD or non-cardiovascular death, and the size of these benefits is consistent with epidemiological associations. The more recent Heart Outcomes Prevention Trial (HOPE)-3 trial found that BP lowering conferred no appreciable benefit in intermediate risk patients (mean 10-year CVD risk ≈ 10%), except for those with pretreatment systolic BP >144 mmHg. Therefore, treatment of patients with pretreatment systolic BP 130 to 139 mmHg and 10-year CVD risk <15% according to JNC7 remains controversial.

Our study had several limitations. Hypertension treatment guideline effectiveness and cost-effectiveness may vary among specific population groups with higher hypertension prevalence, such as blacks and subgroups at high-risk for CVD, in whom greater benefits may derive from hypertension treatment. Although we estimated the effect of hypertension treatment on ischemic heart failure hospitalizations and deaths, coronary heart disease hospitalizations and deaths involving heart failure are difficult to accurately measure based on International Classification of Diseases-coded data. We projected heart failure deaths prevented because of hypertension treatment, but we did not simulate heart failure incidence or capture heart failure states directly, and we may have under-estimated reduced heart failure burden attributable with hypertension treatment. We did not account for non-blood pressure-lowering benefits of certain antihypertensive drug classes, such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, in patients with heart failure or past myocardial infarction. We did assume that most CVD patients would require >1 medication to reach the BP goal, one of those being an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor. We may also have underestimated monitoring costs, including personnel, technology or additional office visits needed to achieve intensive goals.

We followed the decision of the SPRINT trial and did not target an SBP 120 mmHg goal in patients with diabetes mellitus. Uncertainty persists about benefits and risks of intensive BP lowering in these patients. Intensive BP lowering consistently lowered stroke risk in trials enrolling older patients with diabetes, but results for coronary heart disease were variable. Patients with stroke were excluded from SPRINT; our decision to target intensive BP goals in stroke patients is supported by suggestion of a benefit from intensive treatment in patients with stroke enrolled in the Secondary Prevention of Small Subcortical Strokes (SPS3) trial. SPRINT included participants aged ≥75 years of age, but we excluded elderly patients from our analysis because of uncertainty about of risks and benefits of intensive BP lowering in the frail elderly.

JNC recommendations have increased hypertension awareness, treatment, and control in the US population and likely contributed to the decline in CVD mortality during the past four decades. Our results suggest that targeting an intensive goal of 120 mm Hg in selected high-CVD risk patients in addition to the standard JNC guidelines would be cost-saving if high drug costs can be controlled.

Perspectives

Hypertension treatment is inexpensive, safe, and effective. Guidelines should not be applied blindly, without considering the balance between benefits and harms in individual patients. However, in robust otherwise healthy patients aged <75 years targeting more intensive blood pressure treatment goals in high CVD risk patients would be cost saving if monitoring and drug costs could be contained.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Significance.

What's is New?

This is the first study to compare the cost-effectiveness of implementing 2003 JNC7 guidelines for primary prevention and an intensive intervention systolic BP goal of 120 mmHg in high CVD risk hypertensive patients with implementing 2014 JNC8 guidelines.

What is relevant?

Changes in national hypertension treatment guidelines led to uncertainty about the safest, most effective approach to achieving hypertension control.

More recent evidence suggests that more intensive BP lowering leads to net health gains compared to more conservative goals.

Summary:

Adding intensive BP goals for high-risk groups to current national hypertension treatment guidelines prevents additional CVD deaths while saving costs, provided that medication costs are controlled.

Acknowledgements

N. Moise and A.E. Moran had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. L. Goldman, N. Moise, A.E. Moran contributed to the study concept and design; A.E. Moran, C. Huang, P.G. Coxson, and N. Moise contributed to acquisition of data. N. Moise, A.E. Moran, C. Huang, C.N. Kohli-Lynch, and A. Rodgers contributed to analysis and interpretation of data. N. Moise, A.E. Moran, and A. Rodgers contributed to drafting of the article. N. Moise, A.E. Moran, P.G. Coxson, K. Bibbins-Domingo, A. Rodgers, and L. Goldman contributed to critical revision of manuscript for important intellectual content. N. Moise, A.E. Moran, P.G. Coxson, and C. Huang contributed to Statistical analysis. A.E. Moran obtained funding and supervised the study.

Sources of Funding This work was supported by funds from Health Resources and Services Administration (T32HP10260), National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (R01 HL107475-01), and the American Heart Association Founder’s Affiliate (10CRP4140089).

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Drs. Nathalie Moise and Andrew Moran had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Disclosures This manuscript was prepared using Framingham Cohort and Framingham Offspring Research Materials obtained from the U.S. National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Biological Specimen and Data Repository Information Coordinating Center and does not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of the Framingham Cohort, Framingham Offspring, or the NHLBI. Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo is a member of the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and current co-Vice Chair. This work does not necessarily represent the views and policies of the USPSTF.

Financial Disclosures: None

References

- 1.James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: Report from the panel members appointed to the eighth joint national committee (jnc 8). JAMA. 2014;311:507–520. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Navar-Boggan AM, Pencina MJ, Williams K, Sniderman AD, Peterson ED. Proportion of us adults potentially affected by the 2014 hypertension guideline. JAMA. 2014;311:1424–1429. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.2531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wright JJT, Fine LJ, Lackland DT, Ogedegbe G, Dennison Himmelfarb CR. Evidence supporting a systolic blood pressure goal of less than 150 mm hg in patients aged 60 years or older: The minority viewsystolic blood pressure goal for patients aged 60 years or older. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2014;160:499–503. doi: 10.7326/M13-2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The sprint research group A randomized trial of intensive versus standard bloodpressure control. New England Journal of Medicine. 0:doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1511939. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weinstein MC, Coxson PG, Williams LW, Pass TM, Stason WB, Goldman L. Forecasting coronary heart disease incidence, mortality, and cost: The coronary heart disease policy model. American Journal of Public Health. 1987;77:1417–1426. doi: 10.2105/ajph.77.11.1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moran AE, Odden MC, Thanataveerat A, Tzong KY, Rasmussen PW, Guzman D, Williams L, Bibbins-Domingo K, Coxson PG, Goldman L. Cost-effectiveness of hypertension therapy according to 2014 guidelines. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;372:447–455. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1406751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prospective Studies Collaboration Collaborative overview ('meta-analysis') of prospective observational studies of the associations of usual blood pressure and usual cholesterol levels with common causes of death: Protocol for the second cycle of the Prospective Studies Collaboration. Journal of Cardiovascular Risk. 1999;6:315–320. doi: 10.1177/204748739900600508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Law MR, Morris JK, Wald NJ. Use of blood pressure lowering drugs in the prevention of cardiovascular disease: Meta-analysis of 147 randomised trials in the context of expectations from prospective epidemiological studies. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2009;338:b1665. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prevention of stroke by antihypertensive drug treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension. Final results of the systolic hypertension in the elderly program (shep). Shep cooperative research group. JAMA. 1991;265:3255–3264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Law MR, Wald NJ, Morris JK, Jordan RE. Value of low dose combination treatment with blood pressure lowering drugs: Analysis of 354 randomised trials. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2003;326:1427. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7404.1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sundstrom J, Arima H, Woodward M, Jackson R, Karmali K, Lloyd-Jones D, Baigent C, Emberson J, Rahimi K, MacMahon S, Patel A, Perkovic V, Turnbull F, Neal B. The Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists Collboration. Blood pressure-lowering treatment based on cardiovascular risk: A meta-analysis of individual patient data. Lancet. 2014;384:591–598. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61212-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Odden MC, Peralta CA, Haan MN, Covinsky KE. Rethinking the association of high blood pressure with mortality in elderly adults: the impact of frailty. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2012;172:1162–1168. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.2555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson JL, Heidenreich PA, Barnett PG, Creager MA, Fonarow GC, Gibbons RJ, Halperin JL, Hlatky MA, Jacobs AK, Mark DB, Masoudi FA, Peterson ED, Shaw LJ. Acc/aha statement on cost/value methodology in clinical practice guidelines and performance measures: A report of the american college of cardiology/american heart association task force on performance measures and task force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:2304–2322. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vrijens B, Vincze G, Kristanto P, Urquhart J, Burnier M. Adherence to prescribed antihypertensive drug treatments: Longitudinal study of electronically compiled dosing histories. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2008;336:1114–1117. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39553.670231.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brugts JJ, Ninomiya T, Boersma E, Remme WJ, Bertrand M, Ferrari R, Fox K, MacMahon S, Chalmers J, Simoons ML. The consistency of the treatment effect of an ace-inhibitor based treatment regimen in patients with vascular disease or high risk of vascular disease: A combined analysis of individual data of advance, europa, and progress trials. European Heart Journal. 2009;30:1385–1394. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sleight P, Yusuf S, Pogue J, Tsuyuki R, Diaz R, Probstfield J. Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation S. Blood-pressure reduction and cardiovascular risk in hope study. Lancet. 2001;358:2130–2131. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)07186-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Svensson P, de Faire U, Sleight P, Yusuf S, Ostergren J. Comparative effects of ramipril on ambulatory and office blood pressures: A hope substudy. Hypertension. 2001;38:E28–32. doi: 10.1161/hy1101.099502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yusuf S, Sleight P, Pogue J, Bosch J, Davies R, Dagenais G. Effects of an angiotensinconverting- enzyme inhibitor, ramipril, on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients. The heart outcomes prevention evaluation study investigators. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;342:145–153. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001203420301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaplan NM. The diastolic j curve: Alive and threatening. Hypertension. 2011;58:751–753. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.177741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Connor PJ, Narayan KM, Anderson R, Feeney P, Fine L, Ali MK, Simmons DL, Hire DG, Sperl-Hillen JM, Katz LA, Margolis KL, Sullivan MD. Effect of intensive versus standard blood pressure control on depression and health-related quality of life in type 2 diabetes: The ACCORD trial. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:1479–1481. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R. Prospective Studies Collaboration. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: A meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360:1903–1913. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11911-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lv J, Neal B, Ehteshami P, Ninomiya T, Woodward M, Rodgers A, Wang H, MacMahon S, Turnbull F, Hillis G, Chalmers J, Perkovic V. Effects of intensive blood pressure lowering on cardiovascular and renal outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Medicine. 2012;9:e1001293. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lonn E, Bosch J, Lopez-Jaramillo P, et al. Blood-pressure lowering in intermediate risk persons without cardiovascular disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1600175. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1600175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Emdin CA, Rahimi K, Neal B, Callender T, Perkovic V, Patel A. Blood pressure lowering in type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;313:603–615. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.18574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cushman WC, Evans GW, Byington RP, et al. the ACCORD Study Group. Effects of intensive blood-pressure control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;362:1575–1585. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benavente OR, Coffey CS, Conwit R, Hart RG, McClure LA, Pearce LA, Pergola PE, Szychowski JM, the SPS3 Study Group Blood-pressure targets in patients with recent lacunar stroke: The SPS3 randomised trial. Lancet. 2013;382:507–515. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60852-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Odden MC, Pletcher MJ, Coxson PG, Thekkethala D, Guzman D, Heller D, Goldman L, Bibbins-Domingo K. Cost-effectiveness and population impact of statins for primary prevention in adults aged 75 years or older in the United States. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2015;162:533–541. doi: 10.7326/M14-1430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cutler DM, Long G, Berndt ER, Royer J, Fournier AA, Sasser A, Cremieux P. The value of antihypertensive drugs: A perspective on medical innovation. Health Affairs. 2007;26:97–110. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heidenreich PA, Davis BR, Cutler JA, Furberg CD, Lairson DR, Shlipak MG, Pressel SL, Nwachuku C, Goldman L. Cost-effectiveness of chlorthalidone, amlodipine, and lisinopril as first-step treatment for patients with hypertension: An analysis of the antihypertensive and lipid-lowering treatment to prevent heart attack trial (ALLHAT). Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2008;23:509–516. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0515-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lazar LD, Pletcher MJ, Coxson PG, Bibbins-Domingo K, Goldman L. Cost-effectiveness of statin therapy for primary prevention in a low-cost statin era. Circulation. 2011;124:146–153. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.986349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Greving JP, Visseren FL, de Wit GA, Algra A. Statin treatment for primary prevention of vascular disease: Whom to treat? Cost-effectiveness analysis. BMJ (Clinical research Ed.) 2011;342:d1672. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. [December 2, 2014];Red Book Drug References. 2014 http://redbook.com/redbook/awp/.

- 33.California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development Hospital Discharge Survey. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 34. [December 1, 2014];U.S. Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. http://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/.

- 35.Montgomery AA, Harding J, Fahey T. Shared decision making in hypertension: The impact of patient preferences on treatment choice. Family Practice. 2001;18:309–313. doi: 10.1093/fampra/18.3.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and 33 injuries in 21 regions, 1990-2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2197–2223. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.