Abstract

Erectile dysfunction is a multidimensional but common male sexual dysfunction that involves an alteration in any of the components of the erectile response, including organic, relational and psychological. Roles for nonendocrine (neurogenic, vasculogenic and iatrogenic) and endocrine pathways have been proposed. Owing to its strong association with metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease, cardiac assessment may be warranted in men with symptoms of erectile dysfunction. Minimally invasive interventions to relieve the symptoms of erectile dysfunction include lifestyle modifications, oral drugs, injected vasodilator agents and vacuum erection devices. Surgical therapies are reserved for the subset of patients who have contraindications to these nonsurgical interventions, those who experience adverse effects from (or are refractory to) medical therapy and those who also have penile fibrosis or penile vascular insufficiency. Erectile dysfunction can have deleterious effects on a man’s quality of life; most patients have symptoms of depression and anxiety related to sexual performance. These symptoms, in turn, affect his partner’s sexual experience and the couple’s quality of life. This Primer highlights numerous aspects of erectile dysfunction, summarizes new treatment targets and ongoing preclinical studies that evaluate new pharmacotherapies, and covers the topic of regenerative medicine, which represents the future of sexual medicine.

The erect penis has always been a symbol of a man’s virility and sexual prowess. Although it is not a lethal condition, the interest surrounding erectile dysfunction and its remedies has been constant throughout the ages1–5 (FIG. 1). Erectile dysfunction is the inability to achieve or maintain an erection that is sufficient for satisfactory sexual performance, and affects a considerable proportion of men at least occasionally1. Two major aspects of the male erection, the reflex erection and psychogenic erection, can be involved in the dysfunction and are subject to therapeutic intervention: the reflex erection is achieved by directly touching the penile shaft and is under the control of the peripheral nerves and the lower parts of the spinal cord; and the psychogenic erection is achieved by erotic or emotional stimuli, and uses the limbic system of the brain. The severity of erectile dysfunction is often described as mild, moderate or severe according to the five-item International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) questionnaire, with a score of 1–7 indicating severe, 8–11 moderate, 12–16 mild–moderate, 17–21 mild and 22–25 no erectile dysfunction.

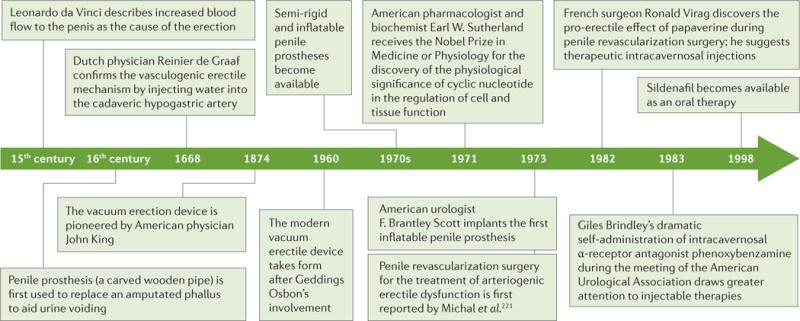

Figure 1. Timeline of the understanding and treatment of erectile dysfunction.

As it became understood that an erection is a predominantly vasculogenic process, filling the cavernosal bodies with blood became one of the key features of different modalities of treatment of erectile dysfunction. For example, the vacuum erection device of today took form when tyre technician Geddings Osbon invented the youth equivalency device in 1960, which combines the effect of a vacuum that draws blood into the penis and the penile ring placed at the base of the penis to occlude venous return. Injectable therapies became prominent following the infamous Brindley lecture ‘Cavernosal α-blockade: a technique for treating erectile impotence’ at the American Urological Association Meeting in Las Vegas, Nevada, USA, in 1983 (REF. 222).

In the past, erectile dysfunction was considered, in most cases, to be a purely psychogenic disorder, but current evidence suggests that more than 80% of cases have an organic aetiology. Causes of organic erectile dysfunction can now be broadly divided into nonendocrine and endocrine. Of the nonendocrine aetiologies, vasculogenic (affecting blood supply) is the most common and can involve arterial inflow disorders and abnormalities of venous outflow (corporeal veno-occlusion); there are also neurogenic (affecting innervation and nervous function) and iatrogenic (relating to a medical or surgical treatment) aetiologies. In terms of endocrine factors leading to erectile dysfunction, reduced serum testosterone levels have been implicated, but the exact mechanism has not been fully elucidated. Often, organic erectile dysfunction involves a psychological component; that is, regardless of the precipitating event, erectile dysfunction imposes negative effects on interpersonal relationships, mood and quality of life.

Importantly, erectile dysfunction is no longer simply confined to sexual activities but acts as an indicator of systemic endothelial dysfunction1. From a clinical standpoint, erectile dysfunction often precedes cardiovascular events and can be used as an early marker to identify men at high risk of major cardiovascular disease6. In this Primer, we describe the different aetiologies of erectile dysfunction and the currently available treatments.

Epidemiology

Several studies have explored the epidemiology of erectile dysfunction by considering different settings and populations. Given that erectile dysfunction is regarded as a condition that is more prevalent in older men, two milestone studies have provided valuable results in this setting: the Massachusetts Male Ageing Study (MMAS) and the European Male Ageing Study (EMAS)7,8. The MMAS showed a combined prevalence of mild to moderate erectile dysfunction of 52% in men aged 40–70 years; erectile dysfunction was strongly related to age, health status and emotional function7. Conversely, the EMAS, the largest European multicentre population-based study of ageing men (40–79 years), reported a prevalence of erectile dysfunction ranging from 6% to 64% depending on different age subgroups and increasing with age, with an average prevalence of 30% (REF. 8) (FIG. 2). Few studies have evaluated erectile dysfunction prevalence worldwide9–12. What emerges from these studies is a systematically higher prevalence of erectile dysfunction in the United States and eastern and southeastern Asian countries than in Europe or South America. Several factors can account for these differences, including cultural or socioeconomic variables; however, further studies are required to identify and discriminate possible genetic influences from environmental impact. Data on erectile dysfunction incidence are less abundant; new cases range from 19 to 66 per 1,000 men every year in studies in the United States, Brazil and the Netherlands13–15. However, these results are not robust owing to short follow-up duration, as well as heterogeneity of the ages and limited geographical locations of the participants.

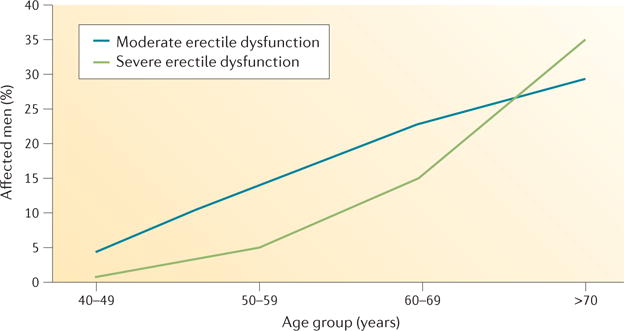

Figure 2. Increasing prevalence of erectile dysfunction with age.

Data from the European Male Ageing Study show that erectile dysfunction increases with age. Importantly, the prevalence of severe erectile dysfunction (defined as an international index of erectile function score of 1–7) increases at a steeper rate than that of moderate erectile dysfunction (score of 8–11) in men over 60 years of age.

Epidemiological data have indicated a strong association between erectile dysfunction and lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH); LUTS are associated with urinary obstruction caused by benign enlargement of the prostate. This association is maintained even after adjusting for potential confounding factors, such as age and comorbid conditions9,15,16. Both erectile dysfunction and LUTS in those with BPH have a high prevalence in ageing men and have common risk factors, such as hypertension and cardiovascular disorders, cigarette smoking, obesity, dyslipidaemia, diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, stress, anxiety and depression17.

Despite being studied thoroughly in men over 40 years of age18, the prevalence of erectile dysfunction in younger men is rarely regarded as interesting19,20. In this context, a recent naturalistic study (a study in which the participant is observed without any manipulation by the researcher) reported that one man out of four seeking medical help for erectile dysfunction in the real-life setting is <40 years of age21. Moreover, another study showed that 22.1% of men <40 years of age had low (<21) Sexual Health Inventory for Men (SHIM) scores22. Studies evaluating erectile dysfunction epidemiology in a younger population will help to clarify the prevalence and incidence in this age group. Although the data are mainly focused on real-life experiences of clinicians, and not supported by population-based studies, it is likely that most cases of erectile dysfunction in younger men have a psychogenic basis. In this context, clues to suggest a psychogenic aetiology usually include sudden onset, good quality spontaneous or self-stimulated erections, major life events or previous psychological problems. However, these factors should not disregard the importance of the components of distress and discomfort that are brought by the onset and persistence of erectile dysfunction and by problems related to sexuality. Such components include anxiety and alexithymia (lack of emotional awareness) and even the possibility that, perhaps especially in younger patients, erectile dysfunction can be both a symptom and a sentinel marker of serious organic problems20,23–26.

Mechanisms/pathophysiology

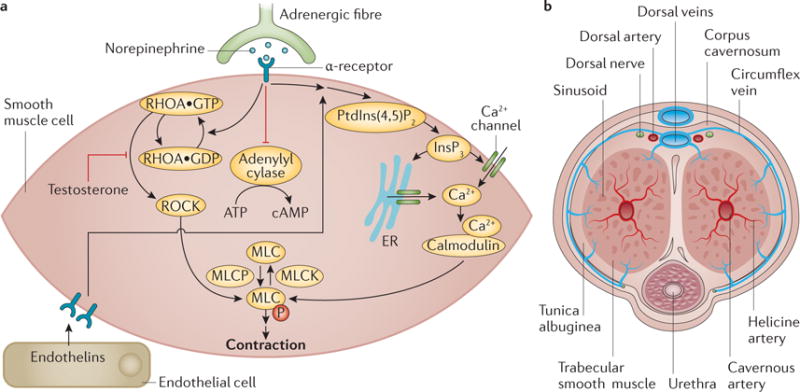

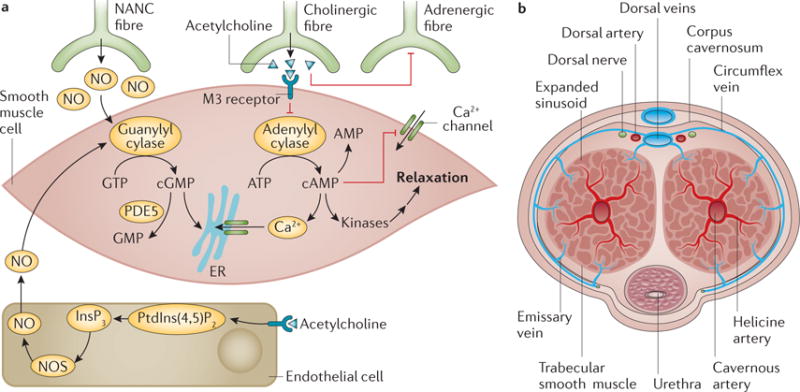

The penis remains in its flaccid state when the smooth muscle is contracted. The smooth muscle contraction is regulated by a combination of adrenergic (noradrenaline) control, intrinsic myogenic control and endothelium-derived contracting factors (prostaglandin and endothelins; FIG. 3)27–29. Upon sexual stimulation, erection occurs after nitric oxide (NO) is released from non-adrenergic noncholinergic (NANC) nerve fibres and acetylcholine is released from parasympathetic cholinergic nerve fibres (FIG. 4); the result of the ensuing signalling pathways is increased cyclic GMP (cGMP) concentrations, decreased intracellular Ca2+ levels and smooth muscle cell relaxation29,30. As the smooth muscle relaxes, blood is able to fill the lacunar spaces in the corpora cavernosa, leading to compression of the subtunical venules, thereby blocking the venous outflow (veno-occlusion). The process is reversed as cGMP is hydrolysed by phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5)29,30. Erectile dysfunction can occur when any of these processes is interrupted.

Figure 3. Penile smooth muscle contraction — the flaccid state.

a | Ca2+ influx into cells is regulated by noradrenaline signalling and levels of inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate (Ins(1,4,5)P3, which is produced from phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PtdIns(4,5)P2) by phospholipase C) in the cells; increased intracellular Ca2+ binds to calmodulin, facilitating the formation of the calmodulin–myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) complex. This leads to the phosphorylation of MLC, resulting in smooth muscle contraction and a flaccid penis. Noradrenaline signalling also inhibits adenylyl cyclase and modulates the RHO-associated protein kinase (ROCK) pathway, which increases the sensitivity of MLC to Ca2+, a process negatively regulated by testosterone. Endothelins and prostaglandins from the endothelium also trigger an increase in intracellular Ca2+ to promote smooth muscle contraction. b | When the smooth muscle is contracted, inflow of blood through the cavernous artery is minimal, and blood outflows freely through the subtunical venular plexus. ER, endoplasmic reticulum; MLCP, myosin light chain phosphatase.

Figure 4. Penile smooth muscle relaxation — the erect state.

a | Upon sexual stimulation, normal erection occurs after nitric oxide (NO) release from non-adrenergic non-cholinergic (NANC) nerve fibres causes the activation of guanylyl cyclase, which raises the concentration of cyclic GMP, and after parasympathetic cholinergic nerve fibres release acetylcholine, which activates adenylyl cyclase to increase the levels of cyclic AMP. Signalling pathways that are triggered decrease intracellular Ca2+ levels and lead to smooth muscle cell relaxation. b | As the smooth muscle relaxes, blood is able to fill the lacunar spaces in the cavernosa, leading to compression of the subtunical venules, thereby blocking the venous outflow. The process is reversed as cGMP is hydrolysed by phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5). ER, endoplasmic reticulum; InsP3, inositol trisphosphate; NOS, NO synthase; PtdIns(4,5)P2, phosphatidylinositol 4,5 bisphosphate.

Psychogenic erectile dysfunction

Non-organic erectile dysfunction is also known as psychogenic or adrenaline-mediated erectile dysfunction (noradrenaline-mediated or sympathetic-mediated erectile dysfunction). It has not been well studied but is an important factor to consider when evaluating and managing men with this condition. Stress, depression and anxiety are generally defined as heightened anxiety related to the inability to achieve and maintain an erection before or during sexual relations, and are commonly associated with psychogenic erectile dysfunction (BOX 1). This association is unsurprising, given that noradrenaline is the primary erectolytic (anti-erectile) neurotransmitter31 (FIG. 3).

Box 1. Symptoms of erectile dysfunction.

Psychogenic

Sudden onset

Intermittent function (variability, situational)

Loss of sustaining capability

Excellent nocturnal erection

Response to phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors is likely to be excellent

Organic

Gradual onset

Often progressive

Consistently poor response

Erection better in standing position than lying down (in the presence of venous leak)

Nonendocrine causes

Neurogenic

Neurogenic erectile dysfunction is caused by a deficit in nerve signalling to the corpora cavernosa. Such deficits can be secondary to, for example, spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson disease, lumbar disc disease, traumatic brain injury, radical pelvic surgery (radical prostatectomy, radical cystectomy, abdominoperineal resection) and diabetes. Upper motor neuron lesions (above spinal nerve T10) do not result in local changes in the penis but can inhibit the central nervous system (CNS)-mediated control of the erection. By contrast, sacral lesions (S2–S4 are typically responsible for reflexogenic erections) cause functional and structural alterations owing to the decreased innervation32. The functional change resulting from such injuries is the reduction in NO load that is available to the smooth muscle. The structural changes centre on apoptosis of the smooth muscle and endothelial cells of the blood vessels, as well as upregulation of fibrogenetic cytokines that lead to collagenization of the smooth muscle. These changes result in veno-occlusive dysfunction (venous leak)33–37.

Vasculogenic

Vascular disease and endothelial dysfunction lead to erectile dysfunction through reduced blood inflow, arterial insufficiency or arterial stenosis. Vasculogenic erectile dysfunction is by far the most common aetiology of organic erectile dysfunction. Indeed, erectile dysfunction can be a manifestation of an underlying vascular disorder. The risk of developing vasculogenic erectile dysfunction is increased in men with hypertension (odds ratio (OR) of 3.04 for those on anti-hypertensive medication, and 1.35 for those not on medication), diabetes (OR 2.57) and dyslipidaemia (OR 1.83)38–41. Cigarette smoking has also been shown to increase the risk of erectile dysfunction (OR 1.4)39,40,42, although smoking cessation can reduce the risk32. Vasculogenic erectile dysfunction does not develop from high blood pressure itself but is secondary to the arterial wall changes (decreased elasticity) in response to the increase in blood pressure. In addition, atherosclerosis related to diabetes, dyslipidaemia and/or cigarette smoking can lead to arterial stenosis and compound the vascular injury.

Hypoxia from decreased corpora cavernosal oxygenation can cause a decrease in prostaglandin E1 levels, which normally inhibit pro-fibrotic cytokines, such as transforming growth factor β1 (TGFβ1)43. These pro-fibrotic cytokines promote collagen deposition, replacing the smooth muscle and resulting in decreased elasticity of the penis, as has been shown in several rat models44. As the smooth muscle to collagen ratio decreases and collagen content increases, the ability of the cavernosa to compress the subtunical veins decreases, leading to corporal veno-occlusive dysfunction45.

Iatrogenic

The most common iatrogenic cause of erectile dysfunction is radical pelvic surgery. Generally, the damage that occurs during these procedures is primarily neurogenic in nature (cavernous nerve injury) but accessory pudendal artery injury can also contribute46. Pelvic fractures can also cause erectile dysfunction in a similar manner, owing to nerve distraction injury and arterial trauma.

Various medications have also been shown to be associated with the development of erectile dysfunction40 (BOX 2). Medications that are used to treat hypertension (thiazide diuretics and β-blockers) are most commonly associated with erectile dysfunction, but others, including psychotherapeutics, anti-androgens, anti-ulcer drugs, opiates and digoxin, have also been linked with the condition40. However, whether the erectile dysfunction results directly from the medication itself or the underlying disease — for example, hypertension — is difficult to define. The Treatment of Mild Hypertension Study (TOMHS) compared five anti-hypertensive drugs with a placebo for changes in quality of life (sexual function was ascertained by physician interviews)47. Chlorthalidone (a diuretic drug used to treat hypertension) had the greatest effect on sexual function at 2 years after treatment, but the placebo achieved almost the same level at 4 years. Accordingly, chlorthalidone may potentiate erectile dysfunction earlier in those who are likely to develop the condition later in life.

Box 2. Medications associated with erectile dysfunction.

Thiazide diuretics, β-blockers and spironolactone used to treat hypertension

Digoxin used to treat atrial fibrillation

5α-reductase inhibitors used to treat benign prostatic hyperplasia

Anti-androgens used to treat prostate cancer

Luteinizing hormone-releasing agonists and antagonists used to treat prostate cancer

Tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, benzodiazepines, antipsychotics and phenytoin used to treat depression and other psychiatric conditions

H2 blockers used to treat ulcers

Opiates used to treat pain

Endocrine causes

Androgens are considered the major hormonal regulator of penile development and physiology48,49; however, the role of testosterone replacement therapy in erectile dysfunction is controversial because of discrepancies in the findings from clinical trials, and the fact that both hypogonadism and erectile dysfunction are common in ageing. The increasing association of erectile dysfunction and the progressive decline of androgen levels with ageing does not necessarily imply a causal link.

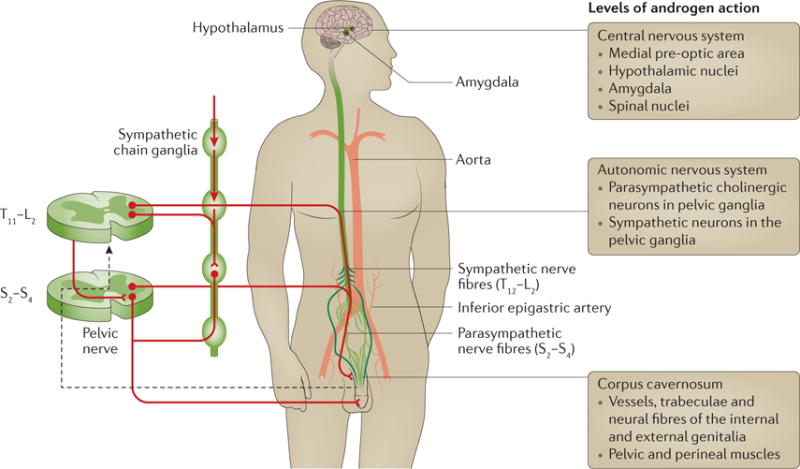

Most early studies aiming to understand the role of reduced testosterone on erectile function focused on androgen ablation — a model that cannot be easily translated to erectile dysfunction in humans50,51. From these studies and metabolic models, three sites of action for androgens have been described: the nuclei in the CNS52, the spinal neurons and pelvic ganglia, and the genital tissues53 (FIG. 5). Part of the erectile response to testosterone is mediated through sexual desire (the male sex drive depends on testosterone), but mechanistic studies have documented a direct role of testosterone on cavernous smooth muscle cells, involving NO, RHO-associated protein kinase (ROCK), PDE5 and the adrenergic response.

Figure 5. Levels of androgen action in the control of sexual response.

Physiological effects of testosterone have been described in the regions of the brain that control sexual arousal at the spinal cord level (affecting neuronal firing from the pelvic ganglia) and within the penis (regulating endothelial and smooth muscle cell function). Testosterone has been shown to modulate the release of nitric oxide from non-adrenergic non-cholinergic fibres, and the functioning of nitric oxide synthase in endothelial cells. In the smooth muscle, testosterone modulates the activity of phosphodiesterase type 5, the kinase that regulates Ca2+ and K+ levels, and adrenergic receptor sensitivity. Figure modified with permission from REF. 53, Elsevier.

Effects on smooth muscle cells

All animal studies support the idea that castration (reduction in testosterone levels) causes a rapid drop in intracavernous pressure, owing to both reduced arterial inflow and altered veno-occlusion during stimulated erections54 — castration is associated with a rapid reduction in neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS)55 and pelvic ganglion activity56. However, in models of hypogonadism or in castration, the effects of testosterone replacement on nNOS have been variable, with some studies revealing increased expression but unaltered activity, and other studies showing no effect55,57. Studies carried out in animals treated with l-NG-nitroargininemethyl ester (l-NAME, a NOS inhibitor) revealed that androgens trigger additional, NO-independent mechanisms that still require intact cGMP generation to control veno-occlusion58. That is, androgens require cGMP to produce an erection, which suggests that androgens modulate the erectile response through redundant mechanisms that involve cGMP generation.

Among these NO-independent targets is the ROCK pathway59, which contributes to tonic smooth muscle cell contraction via calcium sensitization (FIG. 3a). Hypogonadism has been shown to induce activation of ROCK1 (REF. 51), which counteracts smooth muscle cell relaxation. However, hypogonadism does not activate ROCK2, which is increased in response to testosterone in endothelial cells60. Additional studies are necessary to understand the role of androgens in ROCK-dependent modulation of erection.

NO-independent, pro-erectile mechanisms of androgens also include regulation of expression of smooth muscle myosin isoforms61 and sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P)62,63 binding to its natural receptors: a family of G protein-coupled receptors that are widely expressed in the cardiovascular system. S1P receptor activation sustains constriction of smooth muscle cells via phospholipase C (which cleaves phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PtdIns(4,5)P2) into inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate (Ins(1,4,5)P3), leading to increased Ca2+) and the ROCK pathways. In endothelial cells, SIP receptor activation triggers the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)–AKT pathway, enabling crosstalk between the ROCK and the endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) pathways61. The latter findings reinforce a beneficial role of androgens on several overlapping NO-independent pathways (SIP, PI3K–AKT and ROCK) favouring erectile response.

Several in vitro studies using animal and human tissues have shown that PDE5 expression is upregulated by androgens57,64,65. However, recent studies have questioned this evidence, suggesting that low PDE5 in hypogonadism simply reflects the overall reduction in smooth muscle cell content66. Indeed, androgen deprivation triggers apoptosis of smooth muscle cells, extracellular matrix deposition57 and accumulation of lipid droplets in mesenchymeal cells (especially in the subtunical region) contributing to impaired veno-occlusion67. In general, cGMP levels, regulated by the activity of PDE5 (the primary enzyme involved in cGMP degradation), seem crucial for any direct57,64,65 or indirect68 androgenic regulation within the penis58.

A recognized mechanism of action of testosterone in particular is the regulation of α1-adrenergic responsiveness of smooth muscle cells57,69. Castration in animals has also been shown to be associated with a decreased density of NANC innervating fibres and reduced NANC-mediated relaxation in isolated corpora cavernosa strips57. These data suggest an effect of testosterone on the postganglionic parasympathetic neurons, or even further upstream within the autonomic nervous system53. In line with this hypothesis, the effects of castration on penile haemodynamics, including NOS activity, can be transiently reversed in vivo by short-term electrical stimulation of the cavernosal nerve55. Accordingly, androgens might be necessary to support adequate neuronal stimulation to the corpora cavernosa, maintaining tissue structural integrity; denervation, as can occur following prostate surgery, and castration share some histological similarities53.

Hypogonadism and erectile dysfunction

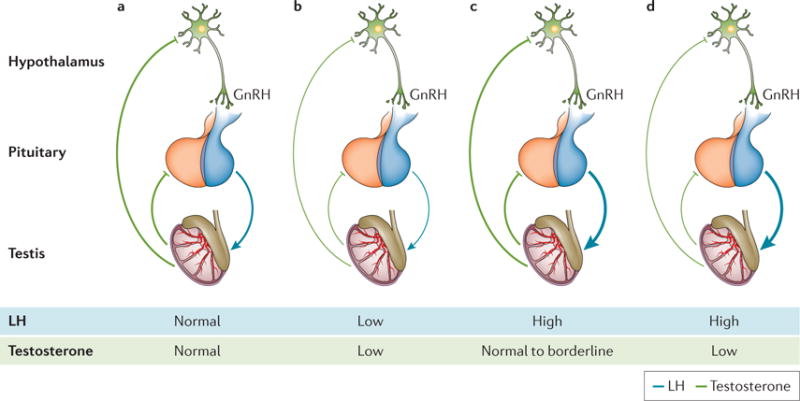

Further evidence for the role of androgens in erectile dysfunction comes from clinical studies. In the 1980s, Bancroft performed pivotal studies to discriminate central effects from peripheral effects of testosterone replacement therapy. He showed that in acute settings, erectile capacity in response to visual stimulation is less sensitive to androgen than sexual interest, fantasies and cognitive sexual activities70. That is, androgen enhances the sexual response to sexual fantasy more than it enhances the response to visual stimuli, which has implications for the kind of sexual activity measured in the research setting. Experimental endogenous hypogonadism induced by gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists71 in supraphysiological-dose studies72 generated the threshold hypothesis, confirmed by epidemiological data, that at least 8 nmol l−1 of testosterone in sera is required for erectile function. However, some hypogonadal men retain near-normal sexual activity despite very low testosterone levels73. In young adults, the androgen dependency of erectile function is maintained at threshold values that are far below those required to maintain the function of other target organs (that is, <8 nmol l−1 or 230 ng dl−1). However, erectile function despite low androgen levels may not apply to elderly men who have comorbidities, possibly owing to changes in androgen receptor expression and activity. To match testosterone levels to an individual’s own requirement, the concept of compensated or subclinical hypogonadism74 has been introduced (FIG. 6). In this setting, it is suggested that when testosterone declines from a previously higher level, a rise in the levels of luteinizing hormone might be a biomarker for insufficient androgenization74,75.

Figure 6. Schematic representation of different types of hypogonadism.

a| The normal pituitary–testicular axis. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) stimulates the release of luteinizing hormone (LH). This triggers the testes to respond by producing adequate levels of testosterone, which, in turn, exerts negative feedback control on the hypothalamus and pituitary gland. Both circulating LH and testosterone are in the normal range. b | Secondary hypogonadism. The pituitary release of LH is impaired, the testes are no longer stimulated and testosterone production drops; both circulating LH and testosterone are reduced. c | Subclinical or compensated hypogonadism. The testicular responsiveness to LH is impaired, testosterone production is maintained owing to overstimulation by LH; circulating testosterone is normal or borderline, whereas LH is increased. In this case, the system is driven to its maximal capacity and no further adjustment can be achieved. d | Primary hypogonadism. In testicular failure, increases in LH can no longer sustain testosterone levels: circulating testosterone is low and LH is high.

Other evidence for a role of testosterone in erectile dysfunction comes from clinical trial data on testosterone replacement therapy. The few available randomized clinical trials addressing the roles of treatment with testosterone in erectile dysfunction have been extensively reviewed, with the largest and most updated meta-analysis confirming significant beneficial effects on various domains of erectile function, but only in men with testosterone levels of less than 12 nmol l−1 (345 ng dl−1) at baseline76. Regression and subgroup analyses emphasized a role of ageing as a possible moderator of responsiveness to testosterone in those with erectile dysfunction76. Another relevant emerging aspect is the time course of testosterone effects (that is, the length of treatment necessary to achieve the maximum result). A recent systematic review77 and randomized clinical trials78–80 revealed that although the effects on libido, ejaculation and sexual activity were apparent within just 2–3 weeks of commencing treatment, the effects on erectile function may take up to 6–12 months to be evident. Recently, the largest and longest trial addressing the effects of testosterone replacement therapy on subclinical atherosclerosis progression in older men showed no significant difference in IIEF score compared with the placebo at 18 months or 36 months after the start of treatment. However, erectile dysfunction was not an inclusion criterion for the trial, and the relatively high baseline total IIEF score suggests that only some of the participants had erectile dysfunction at enrolment81.

Several studies have recently reported growing concerns regarding the safety of sex steroid replacement therapy (in men and women). These studies questioned the physiological roles of the various hormones, and purposefully sought to amplify some sort of ‘hormonophobia’ by exaggerating or misrepresenting safety concerns82. However, leaving aside the controversies surrounding both the alarming83 and reassuring studies84 — contrasts that impose a risk–benefit evaluation before any treatment — it seems clear that these considerations neither apply to young adults with hypogonadism80 nor question the physiological role of testosterone in erectile function.

Finally, little data have addressed the roles of other hormones in erectile dysfunction85. Indeed, possible roles have been documented for thyroid hormones, prolactin, growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor 1, dehydroepiandrosterone and oxytocin. Although these hormones play a part in the pathophysiology of erection, their epidemiological impact is likely to be small and is awaiting confirmation. After testosterone, prolactin is the most commonly altered hormone in men with sexual dysfunction; its main effect is to inhibit gonadotropin secretion to induce hypogonadism. Thus, prolactin should be considered for screening, together with testosterone and luteinizing hormone (FIG. 6), in men with erectile dysfunction.

Diagnosis, screening and prevention

Risk factors

The identification of the pathogenetic factors involved in erectile dysfunction is the cornerstone of an accurate diagnosis and successful treatment.

Lifestyle factors and diabetes

Alcohol and smoking habits have consistently been shown to affect erectile function. Evidence from observational studies suggests a positive dose–response association between quantity and duration of smoking and the risk of erectile dysfunction86,87. Similar results have been documented for alcohol abuse88. In addition, diets that are low in whole-grain foods, legumes, vegetables and fruits, and high in red meat, full-fat dairy products, and sugary foods and beverages are all associated with an increased risk of erectile dysfunction89. Finally, meta-analysis of available evidence demonstrates that moderate and more frequent physical activity are associated with reduced risk of erectile dysfunction90. Accordingly, both cross-sectional and prospective epidemiological studies suggest that obesity and metabolic syndrome are associated with an increased risk of erectile dysfunction91. It is conceivable that obesity-associated hypogonadism and increased cardiovascular risk are correlated with the higher prevalence of erectile dysfunction in overweight and obese men (see below). However, recent clinical and experimental studies suggest that the association between erectile dysfunction and central obesity is independent from obesity-associated comorbidities and hypogonadism91. Although increased levels of tumour necrosis factor (TNF; also known as TNFα) — a cytokine involved in systemic inflammation — could be a mediator of these conditions92, further studies are needed to confirm this. Sexual health is impaired by type 1 and type 2 diabetes and even by a pre-diabetic status93–95. Peripheral neuropathy, atherosclerosis of large blood vessels, endothelial dysfunction of arterioles and the associated hypogonadism all contribute to diabetes-related sexual dysfunction93–95.

Cardiovascular disease

Arteriogenic erectile dysfunction and cardiovascular disease are considered different manifestations of a common underlying vascular disorder. Three independent meta-analyses have documented that erectile dysfunction needs to be considered the harbinger of coronary heart disease96–98 and as a predictor of future silent cardiac events99. This association is particularly important in younger men (<55 years of age) and those with erectile dysfunction and no other comorbidites98, emphasizing the importance of early diagnosis and correct management of erectile dysfunction-associated morbidities. Accordingly, the Princeton III Consensus Recommendations for the management of erectile dysfunction and cardiovascular disease indicate that incident erectile dysfunction has a similar, or even greater, predictive value for cardiovascular disease than traditional risk factors such as diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidaemia or smoking100.

BPH and LUTS

The presence of LUTS alongside BPH represents another important issue in men with erectile dysfunction. The Multinational Survey of The Ageing Male (MSAM-7) study — a multinational survey conducted in the United States and six European countries — demonstrated that the presence of LUTS is an independent risk factor for erectile dysfunction, although the pathological reason for this association is unclear9. Common alterations in the NO–cGMP pathway, enhancement of RHOA–ROCK signalling and pelvic atherosclerosis are often considered the most important mechanisms involved in determining the two conditions.

Psychogenic and relationship factors

Aside from organic factors, psychogenic and relationship domains need to be evaluated in men with symptoms of erectile dysfunction. All sexual dysfunctions, even the most documented organic types (such as diabetes-associated erectile dysfunction), are stressful and can lead to psychological disturbances101. Performance anxiety is a common issue in men with sexual dysfunction, often leading to avoidance of sex, loss of self-esteem and depression101. Psychiatric symptoms are often comorbid in patients with erectile dysfunction101. In addition, many psychotropic drugs can induce erectile and other sexual problems101.

Although considered less often, the quality of a relationship represents an essential determinant of successful sexual activity. In fact, any sexual dysfunction in one member of the couple will affect the couple as a whole, causing distress, partner issues and further exacerbation of the original sexual problem (see below)102. Interestingly, a patient’s perception of reduced partner interest represents an independent predictor of incident cardiovascular events103. Hence, the physical relationship between partners should be considered not only as enjoyable, but also as a strategy for improving overall health and life expectancy.

Diagnostic work-up

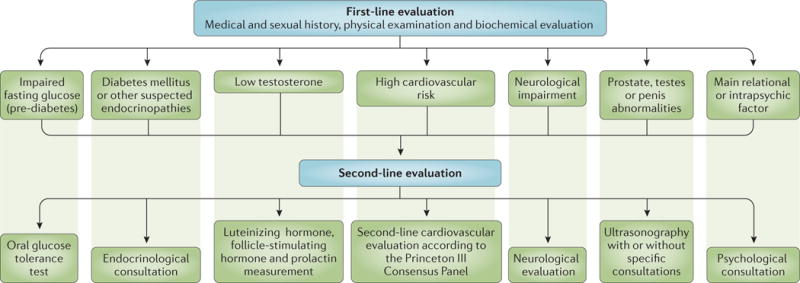

The basic work-up of patients seeking medical care for erectile dysfunction needs to include an evaluation of all the aforementioned factors, including: establishing an accurate medical and sexual history; a careful general and focused genitourinary examination; and a minimum number of hormonal and routine biochemical tests (FIG. 7). Other optional tests can be considered in specific situations (see below).

Figure 7. Suggested diagnostic work-up for patients with erectile dysfunction.

The basic work-up of patients seeking medical care for erectile dysfunction should include an accurate medical and sexual history, a careful general and andrological physical examination, hormonal evaluation (total testosterone and sex hormone-binding globulin in all men, prolactin and thyroid hormone evaluation in some men) and routine biochemical exams (total and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides, fasting glucose and glycosylated haemoglobin). Second-line evaluation should be limited to those with abnormal first-line results.

Given the personal, interpersonal, social and occupational implications of sexual dysfunction, assessing sexual history is not an easy task. Finding the correct way to ask questions and ‘decode’ answers on sexual health and illnesses is necessary to avoid embarrassing the patient. Hence, expert-guided, validated and standardized sexual inventories — structured interviews and self-reported questionnaires (SRQs) — can help both inexperienced and seasoned clinicians to address sexual health and related conditions104. Both structured interviews and SRQs are composed of a set of standardized questions requiring a finite response. Several SRQs have been published, mainly focusing on evaluating erectile dysfunction severity (for example, the IIEF) or erectile dysfunction treatment outcomes (for example, the Erectile Dysfunction Inventory for Treatment Satisfaction (EDITS))104. Structured interviews are generally considered a more reliable instrument than SRQs in evaluating sexual history and causes of erectile dysfunction, as they tend to achieve a closer patient– physician relationship and reduce the risk of misunderstanding. So far, the only validated structured interview on erectile dysfunction that has demonstrated sufficient utility in several clinical studies is the Structured Interview on Erectile Dysfunction (SIEDY)104. SIEDY is a 13-item interview composed of three scales that identify and quantify important domains in men with erectile dysfunction (organic, scale 1; marital, scale 2; and intrapsychic, scale 3).

The physical examination of patients includes evaluation of the chest (including heart rhythm, breathing and signs of gynaecomastia (enlargement of the breasts)), penis, prostate and testes, and of the distribution of body hair105. Small testes and/or small prostate volume, according to the patient’s age, might imply underlying hypogonadism. Similarly, other possible signs of hypogonadism include gynaecomastia as well as a decrease in beard and body hair growth. Assessment of the peripheral vascular system is also important to determine the characteristics of the pulse, to ascertain the presence of an arterial bruit (a vascular sound that is associated with turbulent blood flow). Increased pulse rate (tachycardia) might suggest hyperthyroidism, whereas reduced pulse rate (bradycardia) might be evident in men with heart block (arrhythmia), hypothyroidism or in those who use certain drugs (for example, β-blockers). Diminished or absent pulses in the various arteries examined could be indicative of impaired blood flow caused by atherosclerosis. The evaluation of the penis in the flaccid condition might show the presence of Peyronie disease (involving palpable fibrous plaques), phimosis (congenital narrowing of the opening of the foreskin) or frenulum breve (whereby the tissue under the glans penis that connects to the foreskin is too short and restricts the movement of the foreskin), which can all contribute to erectile dysfunction. Measurement of blood pressure, waist circumference and body mass index is also performed105.

A few biochemical and hormonal parameters are of value in patients with erectile dysfunction. However, levels of cholesterol, triglycerides, fasting glucose and glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) are important determinants of cardiovascular and metabolic risk stratification105,106. Total testosterone and sex hormone-binding globulin for the evaluation of calculated free testosterone105,106 are sufficient parameters to rule out hypogonadism. Prolactin and thyroid hormone evaluation are limited to a subset of patients105,106.

The vast majority of men with erectile dysfunction are managed within the primary care setting. However, in the presence of abnormal biochemical or hormonal values, further diagnostic tests are advisable (second-line evaluation). If the fasting plasma glucose level is 100–126 mg dl−1, or HbA1c is >5.7%, an oral glucose tolerance test can be used to exclude overt type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus. The necessity of performing further cardiovascular evaluation should be based on the criteria of the Princeton III Consensus Panel100 (TABLE 1). In the presence of reduced total testosterone and/or calculated free testosterone, obtaining prolactin and gonadotropin levels will determine the source (central or peripheral) of the problem.

Table 1.

Princeton III Consensus recommendations

| Profile | Description | Sexual activity and PDE5 inhibitor use |

|---|---|---|

| Low |

|

|

| Intermediate |

|

|

| High |

|

Sexual activity delayed until cardiac condition stabilized |

Princeton III Consensus recommendations for risk stratification and cardiovascular evaluation for sexual activity100. PDE5, phosphodiesterase type 5.

Major cardiovascular risk factors include age, male gender, hypertension, type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus, smoking, dyslipidaemia, a sedentary lifestyle and a family history of premature cardiovascular disease.

Defined by the Canadian Cardiovascular Society (see REF. 223).

Recent data have documented that penile duplex Doppler ultrasound (PDDU) can be performed in both flaccid (before vasodilator stimulation) and dynamic states (after vasodilator stimulation) to further improve the stratification of cardiovascular risk in men with erectile dysfunction103,107,108. Nocturnal penile tumescence and rigidity testing using the RigiScan device (GOTOP Medical, St Paul, Minnesota, USA) is currently rarely carried out109; its use is limited to testing the presence of nocturnal spontaneous erectile activity for medico-legal purposes when the presence of naturally occurring erections needs to be demonstrated. Arteriography and dynamic infusion cavernosometry (measuring cavernosal blood pressure) and cavernosography (to assess venous leak) are carried out only in young men who are potential candidates for vascular reconstructive surgery109.

Management

In the absence of a specific correctable aetiology, the management of erectile dysfunction is largely empirical and performed in a step-wise manner. That is, initial treatment is based on lifestyle modification followed by first-line therapies using PDE5 inhibitors and vacuum erection devices (VEDs). Second-line therapies consist of an intraurethral suppository (IUS) of prostaglandin E1 (alprostadil) and intracavernosal injection (ICI) with vasoactive substances. Surgical intervention is reserved as the final option after conservative options have been discussed or attempted.

Lifestyle modification

Lifestyle modifications can have a major role in managing erectile dysfunction, especially in the younger patient. The physician can identify reversible risk factors that contribute to the patient’s erectile dysfunction, such as medications, poor diet, low exercise, endocrinopathies and anxiety. Although epidemiological evidence seems to support a role for lifestyle factors in erectile dysfunction, limited data are available, suggesting that the treatment of underlying risk factors and coexisting illnesses will ultimately improve erectile dysfunction110. The major limitation remains the paucity of interventional studies assessing the effect of lifestyle changes on erectile function.

The available data support the recommendation that adults should do 30 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity most days of the week110. Weight loss in obese men, and switching from a Western diet to a Mediterranean diet, plus exercise, has been shown to improve erectile dysfunction outcomes111–113. It has also been shown that, in a group of patients with congestive heart failure, short-term moderate exercise training can improve sexual function114. A review of the patient’s medications might reveal some drugs that are well known to have erectile dysfunction as an adverse effect (BOX 2). However, much of the data on iatrogenic erectile dysfunction are based on observational studies, with severe limitations.

Smoking has been shown to have a direct relationship with erectile dysfunction, and a dose response relationship has been suggested because men have increased erectile difficulties with greater numbers of packets of cigarettes smoked or more years of smoking38,115,116. One study suggested that cessation of cigarette smoking can improve erectile function117. Mild alcohol consumption might improve erectile function by reducing anxiety; however, chronic use or alcohol abuse can have lasting effects on the liver, leading to low levels of testosterone and increased levels of oestrogen, both of which can contribute to erectile dysfunction118,119. Patients with psychological stressors (such as performance anxiety, relationship issues and current life stress)120 may benefit from confidence restoration with erectogenic medications and/or counselling with a psychologist or other health care professional specializing in sexual dysfunction121. Accordingly, the European Association of Urology states that “lifestyle changes and risk factor modification must precede or accompany any [erectile dysfunction] treatment”, and classifies the level of evidence for lifestyle modification as 1b with a grade A recommendation122.

Nonsurgical interventions

PDE5 inhibitors

Oral phosphodiesterase inhibitors (initially sildenafil, and later, vardenafil, tadalafil, avanafil, and others available outside of the United States (TABLE 2)) have changed the management of erectile dysfunction and created a sexual revolution123,124.

Table 2.

Properties of available phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors

| Drug name | Trade name (company) | Peak absorption post ingestion (hours) | Serum half-life (hours) | Take on empty stomach? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sildenafil* | Viagra (Pfizer) | 1–2 | 3–5 | Yes |

| Vardenafil* | Levitra (GlaxoSmithKline) | 1–2 | 3–5 | Yes |

| Tadalafil | Cialis (Lilly) | 2–4 | 18 | No |

| Avanafil | Stendra (Mitsubishi Tanabe) | 0.5 | 6 | No |

Consider taking 1–2 hours prior to a meal.

Mechanistically, these drugs competitively inhibit PDE5, leading to a build-up of cGMP upon NO release, initiating a cascade of events that lead to smooth muscle relaxation and promotion of an erection29,125 (FIG. 4). Sildenafil and vardenafil reach their median Cmax (maximum observed plasma concentration) values 1 hour after administration and have a half-life of 3–5 hours126–128 (TABLE 2). The medications should be administered with adequate time before sexual intercourse to allow peak absorption of the drug. Patients must be instructed on optimal conditions for the medications to work effectively. Sildenafil and vardenafil should be taken on an empty stomach because lipids in foods can decrease and delay absorption126; tadalafil and avanafil are not as strongly affected by food127,128. Patients should be reminded that PDE5 inhibitors still require sexual stimulation, both physical and mental, to create arousal and initially raise the available levels of NO in an effort to generate cGMP production129.

PDE5 inhibitors have been beneficial in correcting erectile dysfunction in a wide range of patients with varying aetiologies of sexual dysfunction. Sildenafil has been shown to improve erections, leading to successful intercourse in 63% of men with general erectile dysfunction compared with 29% of men using a placebo130. A study in 2001 showed that 59% of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus were able to have successful intercourse while taking sildenafil compared with only 14% of those using a placebo131. In hypogonadal patients who have not responded to treatment with PDE5 inhibitors alone, recent studies have suggested that combination of testosterone supplementation and a PDE5 inhibitor can improve erectogenic outcomes132.

In men with prostate cancer who have undergone nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy, erectile function declines while the cavernous nerves recover from the surgical trauma. Although data regarding the efficacy of penile rehabilitation in radical prostatectomy patients are mixed, the design of studies outside of the Pfizer-sponsored sildenafil study133 are fraught with significant methodological limitations. Thus, so far no study has defined the exact role of PDE5 inhibitors in penile rehabilitation in this patient population. Of note, one randomized placebo-controlled trial in men who have undergone radiotherapy for prostate cancer has demonstrated greater preservation of sexual function in those treated with PDE5 inhibitors versus a placebo134.

Patients should be counselled on the possible adverse events of these drugs, which may include headache, heartburn, facial flushing, nasal congestion and visual disturbances (owing to cross-reactivity with PDE6)124. Myalgia (muscle pain) is more common with tadalafil than the other PDE5 inhibitors. The use of a PDE5 inhibitor with nitrate-containing medications (for example, those used to treat angina) can result in a dangerously low blood pressure135. Also, PDE5 inhibitors and α-adrenergic receptor blockers, often used for treatment of BPH, need to be taken at least 4 hours apart. Priapism (prolonged erection of >4 hours) is a concern, but is a rare occurrence with PDE5 inhibitor therapy (approximately <0.1% of patients)136. Some vision-related conditions are cause for increased precautions, including macular degeneration, retinitis pigmentosa and nonarteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy (NAION). Although no definitive data show causality in NAION, PDE5 inhibitors are contraindicated in patients with vision loss owing to NAION136 (the drugs exert mild inhibitory action against PDE6, which is present exclusively in rod and cone receptors). Concerns have also been raised regarding PDE5 inhibitor use and auditory changes (hearing loss and tinnitus); however, limited data support this link134. Patients who are concerned or who have hearing loss need to be warned about this risk, and may consider other options for erectile dysfunction treatment.

Vacuum erection devices

A VED is a cylindrical mechanical device placed over the penis and then pumped, which creates a negative pressure vacuum to draw blood into the penis137. The blood fills the lacunar spaces within the corpora cavernosa, causing tumescence. Devices are often used in conjunction with a constriction band that is placed at the base of the penis after tumescence is achieved, to prevent the backflow of blood. A study in 1991showed that 75% of diabetic men were able to have sexual intercourse when using a VED to achieve tumescence138. However, discontinuation rates of up to 30% were also reported owing to bruising on the penis, pivoting at the base of the penis, coldness and/or numbness of the penis, pain related to the constriction band and/or decreased ability to achieve orgasm139. Patients benefit from a training session to help optimize their understanding of proper use of VED. Obtaining a tight seal of the cylinder against the body using lubricant and/or trimming the pubic hair is important for success with the VED. Men with large pubic fat pads and/or a buried penis may have difficulty placing the device because they have a less usable penile shaft140.

Several adverse reactions have been noted with VEDs use that should be pointed out to patients. These adverse effects include petechiae (capillary bleeding) and haematoma (a swelling of clotted blood)141. Patients need to be warned that constriction band use to maintain tumescence can give a grey-blue colour to the penis, and that the penis can become cool to the touch, owing to obstructed venous outflow. Few data exist on the use of VEDs for rehabilitation after prostatectomy; however, one randomized prospective study showed that daily VED use can preserve penile length after radical prostatectomy142.

Intraurethral suppository

The use of IUS involves the placement of a prostaglandin E1-loaded pellet within the urethra before sexual intercourse. After insertion of the pellet, the patient should massage that area of the penis to help disperse the medication. The drug is absorbed through the urethra into the corpora cavernosa and increases the intracellular levels of cyclic AMP (cAMP), leading to decreased intracellular Ca2+ levels, increased smooth muscle relaxation and tumescence143.

As a second-line treatment to PDE5 inhibitors, one study showed IUS efficacy in 56% of patients; those with organic erectile dysfunction were more likely to respond144. Another study showed that, across all patients, 65% of men were able to have sexual intercourse, including patients with diabetes144, but a second study found that only 46% of patients with diabetes could have intercourse145.

After radical prostatectomy, one study showed that IUS use for penile rehabilitation was not significantly different to sildenafil. However, the IUS group had a significant dropout rate and lower compliance rate compared with the sildenafil group146.

Patients need to be trained on the technique of the IUS before use and should be advised that pain or burning may occur with use of this medication. The painful sensation can be intolerable for some patients: one study showed that 39% of patients discontinued use owing to pain147.

Priapism is a risk in patients using IUS, but the actual rate of occurrence is low. Other adverse effects include penile pain, urethral pain and dizziness148. Patients need to be cautioned before using IUS if they have any diseases of the urethra, such as urethral stricture. Furthermore, there can also be transference of prostaglandin E1 to the partner, and condoms should be used if the partner is pregnant to avoid premature labour.

Intracavernosal injection

ICI involves the use of vasoactive substances injected directly into the corpora cavernosa via a small needle. These vasoactive agents include prostaglandin E1, papaverine and phentolamine (and sometimes atropine), which work alone or in combination to elicit an erection. Prostaglandin E1 has been approved by the FDA as a single-agent ICI for erectile dysfunction and increases cAMP levels. Papaverine is a nonspecific phosphodiesterase inhibitor that leads to increased levels of cAMP and cGMP. Phentolamine is an α1-adrenergic receptor inhibitor that helps to prevent vasoconstriction to maintain tumescence149.

These vasoactive drugs are available in varying strengths and combinations made by pharmacies: monotherapy with prostaglandin E1; bi-mixture of papaverine and phentolamine; and tri-mixture of prostaglandin E1, papaverine and phentolamine. Patients require training on how to prepare the medications with syringes for home use; an in-office test dose can be useful to characterize the patient’s response. The dose can then be titrated up or down under supervision to one that is satisfactory to the patient. Many patients have an understandable fear of injecting the penis, and overcoming this is the first step to successful treatment150.

Initial satisfaction rates are high, with up to 94% of patients achieving a satisfactory erection with in-office titration151. However, dropout rates with ICI are also high, with 46–80% abandoning treatment in the first year152,153. Reasons for dropouts included lack of partner, high cost, problems with the concept of penile injection and a desire for a permanent solution154.

A major concern with ICI use is priapism. If priapism occurs, the patient will need to seek urgent medical attention, which might require aspiration of blood, surgical shunt formation or ICI of phenylephrine to cause cavernosal vasoconstriction155. Pain has also been frequently described in up to 50% of patients and is usually attributed to prostaglandin E1, but often attenuates over time. Bruising can also be observed, as might be expected with any injected medication.

Injections are useful for patients after radical prostatectomy, if they fail to respond to PDE5 inhibitor therapy. Penile injections have been used frequently in the penile rehabilitation setting based on survey data156, but its acceptance is not widespread.

Surgical interventions

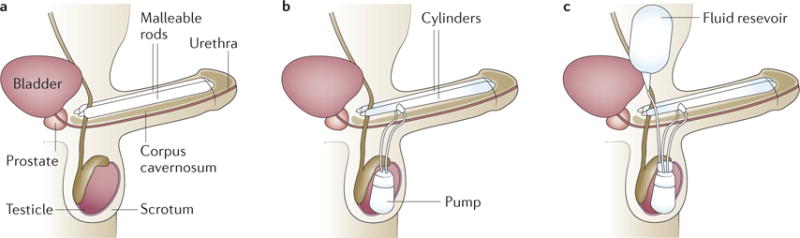

Penile implants

Although oral and vacuum erection therapies are effective first-line and second-line management options for most men with erectile dysfunction, surgical interventions remain an important modality in certain situations. Indeed, surgery might be suited for patients who have contraindications, experience adverse effects or are refractory to medical therapy; patients with erectile dysfunction and penile fibrosis secondary to Peyronie disease, prolonged priapism or severe infections; and patients with structural and/or vascular penile defects from genital or pelvic trauma. The current surgical armamentarium includes insertion of a penile prosthesis and vascular reconstructive surgery.

Penile implants include malleable and inflatable devices157 (FIG. 8). Malleable prostheses consist of semi rigid cylinders that can be bent upwards for sexual intercourse and downwards to conceal when not in use. These devices are easy to handle, have low mechanical failure rates and are optimal for patients who have diminished manual dexterity. Unfortunately, owing to their constant rigidity, they can be uncomfortable, can cause social embarrassment and are at a higher risk of erosion158. Two-piece inflatable penile prostheses (IPPs) consist of two cylinders with a scrotal pump, which enables transfer of fluid to the cylinder chambers when an erection is desired. Although it provides similar rigidity to a malleable device, it also enables better flaccidity when deflated159. Its main indication is in patients in whom placement of an abdominal fluid reservoir is contraindicated or not feasible. For all remaining patients, implantation of a three-piece IPP is considered the gold standard in North America. This system consists of paired corporal cylinders, a scrotal pump and an abdominal reservoir filled with saline. This device provides the greatest degree of girth expansion and penile rigidity (owing to its larger fluid reservoir) when an erection is desired, and the most flaccidity when deflated157. Prosthesis implantation can be performed using infrapubic, penoscrotal or subcoronal approaches.

Figure 8. Penile prostheses.

a | The malleable penile prosthesis involves two semi-rigid rods that are placed in the corpora cavernosa. The implant does change in size; it is bent upwards before intercourse. b | The two-piece inflatable penile prosthesis (IPP) involves placement of two inflatable cylinders in the corpora cavernosa and a pump in the scrotum. As the pump is used, fluid is transferred between the pump and the cylinders. c | The three-piece IPP involves the placement of two inflatable cylinders (in the corpora cavernosa), a pump in the scrotum and a fluid reservoir in the lower abdomen alongside the bladder. Pressure applied to the pump causes a transfer of fluid from the reservoir to the cylinders, leading to penile rigidity. The pump has a release valve or button to transfer the fluid back from the cylinders to the reservoir at the end of intercourse.

One subset of patients who benefit from implantation of an IPP is men with Peyronie disease and concomitant erectile dysfunction. Although penile plication or incision and grafting procedures are options to correct the penile curvature in men with good erections, insertion of a prosthesis is the recommended approach for those with poor erections, often due to vascular insufficiency160. For these men, owing to higher patient and partner satisfaction rates, a three-piece IPP is preferred over a malleable device161. IPP placement alone can often correct the penile deformity, but it is sometimes necessary to use adjunctive straightening manoeuvres — such as penile modelling (manual straightening), plication, incision of plaque and grafting — to optimize results162.

Corporal fibrosis is another circumstance in which penile prosthesis implantation is indicated. Such fibrosis usually occurs secondary to priapism, previous prosthesis infection or trauma. Surgical techniques include excision or incision of the scar, corporal excavation, corporotomies with or without grafting, use of cavernotomes (to scrape the fibrotic areas), implant downsizing and transcorporal resection163.

Contemporary data using newer devices (for example, devices made with sturdier materials or antibiotic-coated devices) demonstrate improved results with rates of overall freedom from reoperation and mechanical failure at 10 years of 74.9% and 81.3%, respectively164. Reported complications following IPP implantation include infection, distal cylinder erosion, auto-inflation, pump migration and reservoir displacement165. Overall, IPP placement is associated with excellent patient (92–100%) and partner (91–95%) satisfaction rates, significantly higher than satisfaction rates reported for oral, intraurethral and intracavernosal medical therapies166,167. However, because of its associated high cost, potential complications and invasiveness of the procedure, IPP implantation should only be offered to patients who fail more conservative measures (such as those described above).

Penile revascularization

Building on the same principles as bypass surgery for coronary artery disease, penile revascularization surgery techniques were developed to anastomose the inferior epigastric artery to either the dorsal artery or deep dorsal vein (arterialization), with or without venous ligation165, to improve penile vascular inflow while reducing venous outflow. However, multicentre studies have revealed that arteriogenic erectile dysfunction is not common, and is more often associated with systemic multifactorial disease, possibly caused by a combination of endothelial and corporal smooth muscle dysfunction, leading to a drop in penile revascularization procedures performed clinically165. A review of the published literature shows that the overall sexual satisfaction rate following penile revascularization (12%) is lower than that following placement of an IPP (93%)165. Currently, penile revascularization is recommended for younger men (<55 years) who are not diabetic, non-smokers and have a documented isolated stenotic segment of the internal pudendal artery without concomitant venous leak. The success rates are reported to be as high as 80% in some populations168,169. Potential complications of penile revascularization include glans hyperaemia, shunt thrombosis and inguinal hernias170.

Currently, no standardized method is available to accurately and systematically diagnose corporal veno-occlusive dysfunction independently of general arterial insufficiency171. Most medical experts and organizations think that venous leak is a consequence rather than an isolated aetiology of erectile dysfunction. As such, both the American Urological Association and the International Society for Sexual Medicine concur that “surgeries performed with the intent to limit the venous outflow of the penis are not recommended” (REFS 171,172).

Quality of life

Impact on the patient

Erectile dysfunction can have a substantial negative effect on a man’s quality of life (BOX 3). Many men with erectile dysfunction experience depressive symptoms and anxiety related to sexual performance and avoid engaging in sexual relations. Many men also avoid seeking treatment for their sexual dysfunction173–176. The association between the condition and depression is considered to be bidirectional, with the two conditions reinforcing each other in a downward spiral173. Importantly, men with depression and erectile dysfunction have lower libidos than men with erectile dysfunction alone, and are less likely to discuss their erectile dysfunction with their partners175,177.

Box 3. Impact of erectile dysfunction on the patient, partner and couple.

Intimate relationships and health have a dynamic nature over time

Involvement of both partners’ health in joint overall ‘health’ means that the illnesses of one partner affect the health of the other

Rates of depression in men with erectile dysfunction are reported to be as high as 56%

Anxiety in a sexual situation is prevalent and can trigger a loss in sexual confidence

As a result of this psychological burden, many men with erectile dysfunction avoid sexual situations and use erectogenic medications

Erectile dysfunction negatively affects a man’s quality of life and satisfaction in his relationship

Erectile dysfunction is associated with female partner sexual dysfunction

Female sexual function improves with treatment of erectile dysfunction in her partner with phosophodiesterase type 5 inhibitors and nerve-sparing surgery (in men with prostate cancer)

The proportion of men with erectile dysfunction has been reported to be as high as 50%, and data from many well designed population-based studies have demonstrated a significant relationship between erectile dysfunction and depressive symptoms (OR 1.7, P < 0.05)174,175. These studies were conducted in men aged 40–70 years in the United States, Finland, Brazil, Japan and Malaysia.

Anxiety is also a concern, and it can lead to the inability to maintain an erection (psychogenic erectile dysfunction)178. This anxiety increases a man’s focus on the firmness of his erection, leading to self-consciousness and cognitive distractions that interfere with arousal and contribute to poor performance179,180. Men who cannot achieve or maintain an erection as a result of anxiety lose sexual confidence and generally develop greater fears leading up to the next sexual encounter, which increases the likelihood of failure and reinforces the pressure to perform during future encounters178.

Given the psychological consequences of erectile dysfunction, it is not surprising that many men have difficulty accepting their condition and avoid treatment. Research indicates that as many as 69% of men deny the existence of their erectile dysfunction, and the median time to pursue treatment for erectile dysfunction is >2 years181. Men report that they experience significant disappointment and shame related to erectile dysfunction; and even when using erectile dysfunction treatments, men report a fear of failure and a tendency to avoid sexual situations as a result of this fear182. In fact, data indicate that 50–80% of men discontinue use of medical interventions (oral medications, ICIs or VEDs) for erectile dysfunction within 1 year183,184, and dropout rates related to PDE5 inhibitor use are estimated to be 30–50%185–187. Although men discontinue erectile dysfunction treatment for a number of reasons, avoidance of sexual activity might be a primary cause182. This avoidance leads to continued distress, anxiety and potential relationship difficulties.

Considering the potential psychological effect of erectile dysfunction, appropriate psychological evaluation, in addition to appropriate medical treatment, is important. This biopsychosocial perspective implies that physical treatments, as well as psychological interventions, are needed to ensure that men pursue and continue to use appropriate erectile dysfunction treatments.

Impact on the partner

Health and sexuality have a bidirectional relationship, and both partners of a couple contribute assets and/or liabilities to the health endowment. In this context, health is defined as jointly produced by a man and his intimate partner188. Joint production of health means that the illnesses of one partner affect the health of the other; in addition, there is a dynamic aspect in both intimate relationships and health over time. For example, if a man has erectile dysfunction, his partner might report decreased libido because he or she is anticipating a negative sexual experience rather than a positive one. Similarly, an endometrial cancer survivor with stenosis and dyspareunia can have a partner who experiences sexual aversion because he or she fears intimacy will cause her pain189. Likewise, if a man has premature ejaculation, his partner may be unable to experience orgasm, which causes distress about sexual satisfaction190. However, this distress may be reversed when the partner’s sexual dysfunction is treated.

The Female Experience of Men’s Attitudes to Life Events and Sexuality (FEMALES) study characterized the sexual experience of female partners of men with erectile dysfunction through surveys performed before and after the development of their partner’s erectile dysfunction and in relation to his use of PDE5 inhibitors191. The study showed that after men develop erectile dysfunction, their partners engage in significantly less sexual activity than before (P < 0.001). Women with partners taking PDE5 inhibitors reported that they experienced more frequent sexual desire, arousal and orgasm (P < 0.05) than women with partners not receiving treatment. A study carried out in Taiwan evaluated the association of erectile dysfunction with female sexual function and corroborated the results from the FEMALES study192. It demonstrated that female partners of men with erectile dysfunction had significantly (P < 0.001) lower overall and individual domain scores on the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) than women whose partners did not have erectile dysfunction. After adjusting for other risk factors, the women’s sexual function was worse in terms of arousal, orgasm, sexual satisfaction and sexual pain.

Impact on the couple

Sexual dysfunction is not only an issue for the individual but also for the couple. In one trial, on-demand oral vardenafil improved erectile function as measured by males’ responses to the Sexual Encounter Profile question 3 (P < 0.0001), and the sexual quality of life of the couple as measured by the female partners’ responses to the quality of life domain of the modified Sexual Life Quality Questionnaire at last observation carried forward (P < 0.0001)193. Another vardenafil treatment study showed similar efficacy for erectile dysfunction and also improved the sexual satisfaction of the female partners who had not themselves received specific interventions for sexual function194. The female partners’ total FSFI score and scores for sexual desire, subjective arousal, lubrication, orgasm and satisfaction increased. This study also showed that the female partner’s sexual function improvements significantly related to treatment responses in her partner.

A study assessing the impact of prostate cancer treatment on couples’ sexual function during the initiation phase of treatment found that the couples’ ‘complicity’ remained intact despite decline in the male’s sexual function195. Global marital adjustment was measured by the marital adjustment test (MAT), a self-reported 15-item questionnaire that successfully differentiates between distressed and non-distressed couples; couples’ MAT scores were unchanged before and after robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy. However, postoperative decreases in IIEF scores and the female partners’ FSFI scores were significantly associated within couples. Interestingly, when strategies were used to prevent or limit erectile dysfunction, sexual function of women improved; bilateral nerve-sparing surgery preserved not only male but also female sexual function195.

These various interventions demonstrate the interrelationship of partners’ sexuality and the concept of a sexual unit in long-term relationships. Thus, couple sexuality is a dynamic process, which adapts and responds to the sexual states of each partner and can be enhanced by interventions directed at improving one partner’s sexual functioning.

Outlook

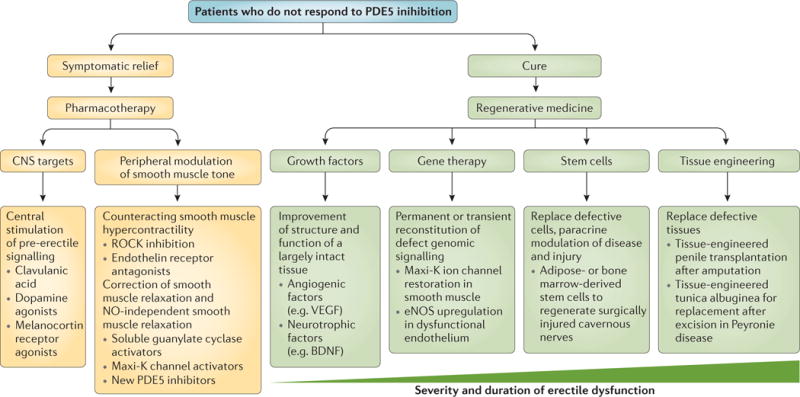

Although the clinical management of erectile dysfunction has been rather static since the advent of PDE5 inhibitors, basic and translational research has continued to progress and deliver new therapeutic targets that are in various stages of development. A crude division can be made between pharmacotherapeutic compounds196 on the one hand, and regenerative medicine197 on the other (FIG. 9).

Figure 9. Potential future treatment options for erectile dysfunction.

Current treatments provide temporary symptomatic relief, but do not interfere with the progress of the disease itself. The first-line treatment of phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) inhibition depends on bioavailable nitric oxide (NO) to exert any effect. Accordingly, future pharmacological therapies will need to be efficacious in patients who do not respond to PDE5 inhibition (thereby providing treatment to men with neurogenic erectile dysfunction) and provide temporary relief or ‘erections on demand’. The site of action may be the central nervous system (CNS), or a variety of peripheral pathways that control the balance between vasoconstriction and vasorelaxation. By contrast, the aim of regenerative medicine is definitive symptomatic relief (cure) by reversing or halting the progression of degeneration in erectile dysfunction. Regenerative medicine intends to change the course of the disease and in many instances will regenerate failing cells, tissues or whole organ systems. Depending on the severity of tissue damage or the severity of the clinical presentation, various tools, such as growth factors, gene transfer, (stem) cells and tissue engineering could be used to achieve this goal. eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; Maxi-K channel, calcium-activated potassium channels; ROCK, RHO-associated protein kinase.

Pharmacotherapeutics

A considerable proportion of men do not respond to oral PDE5 inhibitors and have to resort to ICI therapy or penile prosthesis implantation to be able to have intercourse198. Refractoriness to PDE5 inhibitors stems from the need for endogenous NO release from the NANC fibres and for the endothelium to be able to accumulate cGMP to cause smooth muscle relaxation during sexual stimulation196. Thus, there is a clear medical need for compounds (preferentially orally administered ones) that cause smooth muscle relaxation in the absence of NO. Although both centrally and peripherally acting compounds are being preclinically investigated, ROCK inhibitors and soluble guanylyl cyclase activators are of particular interest because they can be beneficial to patients who do not respond to PDE5 inhibitors. Detailed reviews of the pharmacotherapeutic pipeline in erectile dysfunction are available elsewhere196–199.

ROCK inhibitors

The ROCK pathway plays an important part in maintaining the flaccid state of the penis (FIG. 3a). ROCK phosphorylates and inactivates myosin light chain phosphatase, allowing the myosin light chain to stay phosphorylated and, therefore, bound to smooth muscle actin200. That is, inhibition of ROCK provides a mechanism of smooth muscle relaxation that is independent of NO. In various animal models of erectile dysfunction (diabetes, ageing and cavernous nerve injury), ROCK was found to be upregulated, which makes it an attractive target for the future treatment of erectile dysfunction201–203. In animal studies, acute administration of the ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 was shown to induce relaxation of rat corpus cavernosum strips in vitro and to cause an increase in intracavernous pressure in rat models of erectile dysfunction. The inhibition of ROCK elicited an erectile response by a process that was not mediated by NO or cGMP, and resulted in better erectile responses than in sham-treated animals201–203. Recently, it was shown that ROCK2 is upregulated in the corpora cavernosa of men with erectile dysfunction, corroborating earlier results in animal studies204. This indicates that ROCK2 may be an important target, especially as targeting an upregulated isoform of ROCK specifically addresses the altered physiology in the diseased smooth muscle. Furthermore, animal studies have shown that chronic ROCK inhibition can lead to sustained improvement of erectile function201–203.

Although Y-27632 is still in a preclinical phase, SAR-407899 (another ROCK inhibitor under development) has advanced to clinical trial. However, although a randomized double-blind Phase II trial in 20 patients with erectile dysfunction (NCT00914277)196 was conducted, the results, for unknown reasons, were never made public. Other ROCK inhibitors, such as cethrin, are currently under clinical investigation for related conditions such as spinal cord injury, and successful outcomes of these studies might bring promise for erectile dysfunction following cavernous nerve injury.

Soluble guanylyl cyclase activators

Another class of molecules under consideration is the activators of soluble guanylyl cyclase. In the healthy state, this enzyme is activated by NO to generate cGMP from GTP196. However, when endogenous NO production is limited, direct activation of soluble guanylyl cyclase can result in smooth muscle relaxation. Activators of soluble guanylyl cyclase have been shown to induce smooth muscle relaxation in vitro and penile erection in vivo in animal models. One activator, BAY60-4552, was investigated in a rat model of erectile dysfunction following cavernous nerve injury in combination with vardenafil; the combination therapy resulted in improved erectile function compared with non-injured sham-treated animals205. A subsequent clinical study showed that BAY60-4552 and vardenafil had synergistic effects on smooth muscle relaxation in corpus cavernosum strips from patients who did not respond to PDE5 inhibitors206.

The safety of BAY60-4552 has been tested in a Phase I trial (NCT01110590). When given in combination with vardenafil, no major adverse effects were reported in men with erectile dysfunction according to company data207. However, a Phase II study (NCT01168817)208 study failed to demonstrate superior efficacy of the combination treatment of BAY60-4552 plus vardenafil versus vardenafil alone, although both active treatments showed superior efficacy versus a placebo. The drug is apparently not being investigated further for erectile dysfunction because it was not shown to be superior to vardenafil monotherapy. Aspects of the study design merit further examination of this compound as a treatment for erectile dysfunction by either pharmaceutical companies or academia. Further research is also warranted in the specific population of patients who do not respond to PDE5 inhibitors.

Regenerative medicine