Abstract

Objective

To investigate the heterogeneity of temporal patterns of vasomotor symptoms (VMS) over the menopausal transition and to identify factors associated with these patterns in a diverse sample of women.

Methods

The Study of Women's Health Across the Nation is a multi-site longitudinal study of women from five racial/ethnic groups transitioning through the menopause. The analytic sample included 1455 women with non-surgical menopause and a median follow-up of 15.4 years. Temporal patterns of VMS and associations with serum estradiol and follicle stimulation hormone, race/ethnicity, body mass index (BMI), and demographic and psychosocial factors were examined using group-based trajectory modeling.

Results

Four distinct trajectories of VMS were found: onset early (11 years prior to the final menstrual period (FMP)) with decline after menopause (Early onset, 18.4%); onset near the FMP with later decline (Late onset, 29.0%), onset early with persistently high frequency (High, 25.6%); and persistently low frequency (Low, 27.0%). Relative to women with persistently Low frequency of VMS, women with persistently High and Early onset VMS had a more adverse psychosocial and health profile. Black women were overrepresented in the Late onset and High VMS subgroups relative to white women. Obese women were underrepresented in the Late onset subgroup. In multivariable models, the pattern of estradiol over the menopause was significantly associated with the VMS trajectory.

Conclusions

These data demonstrate distinctly heterogeneous patterns of menopausal symptoms which are associated with race/ethnicity, reproductive hormones, pre-menopause BMI and psychosocial characteristics. Early targeted intervention may have a meaningful impact on long-term VMS.

Keywords: Vasomotor symptoms, Menopause, Estradiol, Follicle Stimulating Hormone, Race/ethnicity, Psychosocial factors

Introduction

Vasomotor symptoms (VMS: hot flushes and night sweats), are the “classic” menopausal symptom. VMS are experienced by up to 80% of women 1, 2 and have a negative impact on women's quality of life during the menopause transition (MT).3 More than half of the women with VMS seek medical treatment for their symptoms.4

While prevalence of VMS is high during and after the MT, individual women have significant heterogeneity in the timing of onset and course of VMS,5 but variations across women in the patterns and time course of VMS over the MT have not been well characterized. Most studies investigating the time course of VMS have focused on the population average and have not considered the magnitude of the variation or attempted to identify risk factors that distinguish those women who experience various patterns of VMS. A study of 695 white women classified VMS severity into four profiles and identified self-reported risk factors that related to the different profiles.6 Whether the variation exists among other racial/ethnic groups and with longer observation time is unknown.

Several hormonal, psychosocial, lifestyle, health and biological factors have been associated with occurrence of VMS. The occurrence of VMS coincides in most women with the decline of endogenous estrogen, most notably estradiol (E2), and a rise in follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) during midlife.7.8 Race/ethnicity, obesity, negative affect, socioeconomic status, and health status,5,6,9 are associated with the likelihood of reporting VMS. Whether these factor predict a particular trajectory pattern of VMS is not well investigated. The current study aimed to characterize the trajectories of VMS occurrence in a racially/ethnically diverse cohort and identify individual factors related to variations in these trajectories. Such information will provide insight into the heterogeneous patterns of these highly prevalent and often bothersome menopausal symptoms and may help clinicians counsel women about their expected course and enhance women's ability to make informed decisions about their treatment.

Materials and Methods

Sample and Procedures

The Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN) is a multi-site longitudinal community-based study of women transitioning through the menopause from February 1996 through April 2013. SWAN enrolled 3,302 women belonging to one of five predetermined racial/ethnic groups: White (n=1550), Black (n=935), Japanese (n=281), Chinese (n=250), and Hispanic (n=286). At the time of enrollment, women were aged 42-52 years, had their uterus and at least one ovary, were not using medications known to affect ovarian function, were not pregnant or lactating, and had at least one menstrual period in the 3 months prior to study entry. The SWAN cohort was recruited from seven clinical sites.10 Each site recruited non-Hispanic white women and one other racial/ethnic group. Black women were enrolled in Pittsburgh, Boston, Detroit, and Chicago, Japanese women in Los Angeles, Chinese women in Oakland, CA, and Hispanic women in Newark, NJ. Institutional review board approval for the study protocol was obtained at each clinical site; signed, written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

At the baseline visit and at thirteen follow-up visits, SWAN participants completed a standard protocol that included questionnaires, physical measures, and provision of blood samples. To characterize the trajectory of VMS relative to menopause stage, the current study was restricted to women who had an observable final menstrual period (FMP) (n=1790). The FMP was identified at the first visit when a woman had no menses for at least 12 months, and the date of FMP was the date of the last reported menstrual period. Natural menopause was defined for women who did not have a hysterectomy and/or oophorectomy and did not report any use of exogenous hormones 12 months before the FMP. The analysis included women who experienced natural menopause (n=1589) and women who stopped hormone use and had menstrual bleeding after a 6-month washout period and then at least 12 consecutive months of amenorrhea (n=201).

Observations when participants were using hormone therapy over the MT were excluded from the analysis to avoid ambiguity in VMS reporting. Time was evaluated relative to the date of the FMP; observations ranged from 13 years before the FMP to 17 years after FMP. We excluded the extreme years with <100 observations to avoid small cell problems. Thus, the analysis period encompassed 12 years before to 15 years after the FMP. Finally, we excluded women who had missing baseline values for covariates: body mass index (BMI, n=22), educational attainment (n=14), alcohol use (n=88), smoking (n=36), general health status (n=120), menopause status (n=37), depressive symptoms (n=2), difficulty paying for basics (n=10) and symptom sensitivity (n=127). Our final analytic sample included 1455 women with 17,814 observations, an average 12.2 observations per woman.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Vasomotor Symptoms (VMS)

Women self-reported their VMS in two questions querying the presence and the frequency of hot flashes and night sweats over the prior two weeks. Women reporting any hot flashes or night sweats in the prior two weeks were considered as having VMS.

Covariates

E2 and FSH

Women provided fasting blood samples during the early follicular phase (days 2-5 of the menstrual cycle) at each visit. For women who were unable to provide an early follicular phase sample or had ceased menstruating, a random fasting sample was obtained within 90 days of the recruitment anniversary date. Blood was prepared and serum shipped to the Clinical Ligand Assay Satellite Services (CLASS) Central Laboratory at the University of Michigan. E2 assays were conducted in duplicate and FSH assays in singlicate using an ACS-180 automated analyzer (Bayer Diagnostics Corporation, Norwood, MA). E2 concentrations were measured with a modified, off-line ACS-180 (E2-6) immunoassay.11 FSH concentrations were measured with a two-site chemiluminometric immunoassay.

Based on prior work,12 the dynamic change of E2 levels declining over the MT was characterized using group-based trajectory modeling (GBTM). Four E2 trajectory patterns were identified: 1) low level and slow declining (Low, slow decline, 15.1%); 2) low level with relatively flat decline (Low, flat, 40.5%); 3) high level and steep decline about 3 years before the FMP (High, early decline, 14.3%); and 4) high level and high peak then sharp decline before the FMP (High, high peak, 30.1%) (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 1). The likelihood of experiencing a specific E2 trajectory was estimated for each woman; and the trajectory with the highest likelihood was identified as the most probable pattern for the woman. The trajectories of FSH over the MT in the current analyses showed FSH starting low and rising to different levels:12 1) low (9.4%), 2) medium (47.2%), and high (43.5%) (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 2).

Baseline measures

At baseline, all participants were either pre- or early peri- menopausal. Pre-menopause was defined as bleeding in the 3 months before interview with no change in variability in the past year, and early perimenopause as bleeding in the past 3 months with increased variability in the past year. Height and weight were measured using a stadiometer and calibrated scales, respectively. BMI was calculated as weight (kg)/height (m2). Body size at baseline was categorized as normal/underweight, overweight, or obese based on racial/ethnic-specific BMI cutpoints:13 BMI <25, 25-29.9, and ≥30 for white, black, and Hispanic women, BMI <23, 23-24.9, ≥25 for Japanese women,14,15 and BMI <24, 24-27.9, ≥28 for Chinese women.16

Smoking history was adapted from the American Thoracic Society standard questions17 and analyzed as current vs. past/never smoking. Alcohol use was defined based on self-reported average alcohol consumption during the past year and categorized as none, light (<1 serving per week), moderate (1-7 servings per week), or heavy (>7 servings per week). Physical activity was measured as a continuous score adapted from the Kaiser Permanente Health Plan Activity Survey.18 Difficulty paying for basics (food, housing, and heat) was recorded as not hard, somewhat hard, or very hard and used to assess functional economic status.

Anxiety symptoms were assessed using four items19 to rate the frequency (0 (none) to 4 (daily)) of anxiety-related symptoms (irritability, feeling tense or nervous, heart pounding or racing, or feeling fearful) in the past two weeks. The summed score ranged from 0 – 16, and scores in the highest quintile (score of ≥ 4) were defined as having anxiety.20 The four items in the anxiety score have been shown to be internally consistent (Cronbach α=0.77), and there was a strong association (Spearman r=0.71) between the anxiety score and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7). Depressive symptoms were measured based on a 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D) which has well-established reliability and validity.21 Symptom sensitivity was a continuous measure of somatosensory amplification22 with higher scores indicating greater tendency to report somatic symptoms. The coefficient of reproducibility for this scale was reported to be 0.85.22

Statistical Analysis

Following the group-based trajectory modeling approach,23,24,25 the trajectory of the longitudinal binary VMS outcomes was modeled as a function of time relative to FMP based on a logit distribution. The number of groups and corresponding shapes were determined by fit statistics (Bayesian Information Criterion) and reasonable scientific plausibility. Model fit was also checked graphically, comparing observed and estimated trajectory of outcome measures. The probability of belonging to each VMS trajectory group was estimated for each woman; the subgroup with the highest estimated probability was assigned to the woman.

Using multinomial logistic regression, the relationship of baseline covariates, age at FMP, and hormone trajectory indicators, to VMS trajectory group membership was investigated for E2 and FSH separately. All covariates as time-stable factors were included in the model. Adjusted odds ratios were reported to describe the association between belonging to a particular VMS trajectory group and participant characteristics. Analyses were conducted using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary NC). SAS Proc Tra j24,25 was used for the modeling.

Results

The median follow-up time of the study sample of 1455 women was 15.4 years and the median age of menopause was 52.2 years. Almost half the women (47.3%) were non-Hispanic white, 25.8% black, 11.5% Japanese, 9.8% Chinese, and 5.6% Hispanic. At baseline, 43.6% of the women were early peri-menopausal, 40.5% were obese, and 14.4% were current smokers. While half of the women did not drink alcohol, 12.6% were heavy drinkers (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN) Participants in the Analysis of Trajectories of VMS during Menopausal Transition (n=1455)

| Characteristicsa | Participants (n=1455) |

|---|---|

| Race/Ethnicity, No. (%) | |

| White | 688 (47.3) |

| Black | 376 (25.8) |

| Chinese | 142 (9.8) |

| Japanese | 167 (11.5) |

| Hispanic | 82 (5.6) |

| Enrollment site, No. (%) | |

| Detroit | 216 (14.8) |

| Boston | 209 (14.4) |

| Chicago | 212 (14.6) |

| Pittsburgh | 193 (13.3) |

| Oakland | 243 (16.7) |

| Los Angeles | 260 (17.9) |

| Newark | 122 (8.4) |

| BMI category, No. (%) | |

| Normal weight | 590 (40.5) |

| Overweight | 276 (19.0) |

| Obese | 589 (40.5) |

| Age at FMP, median (IQR) | 52.2 (50.2, 53.8) |

| Menopause status, No. (%) | |

| Premenopause | 820 (56.4) |

| Early perimenopause | 635 (43.6) |

| Physical activity score (per point) | 7.7 (1.8) |

| Smoking status, No. (%) | |

| Never | 890 (61.2) |

| Past | 210 (14.4) |

| Current | 355 (24.4) |

| Alcohol servings per week use, No. (%) | |

| None | 741 (50.9) |

| ≤1 | 146 (10.0) |

| 1-7 | 385 (26.5) |

| >7 | 183 (12.6) |

| General health status, No. (%) | |

| Excellent | 261 (17.9) |

| Very good | 589 (40.5) |

| Good | 433 (29.8) |

| Fair/Poor | 172 (11.8) |

| Difficulty paying for basics, No. (%) | |

| Not hard | 917 (63.0) |

| Very/somewhat hard | 538 (37.0) |

| Educational attainment, No. (%) | |

| ≥College | 779 (53.3) |

| <College | 679 (46.7) |

| Depressive symptoms scores on the CES-D Scale (per point) | 9.9 (9.1) |

| Anxiety ≥4 symptoms (vs. 0-3) , No. (%) | 280 (19.2) |

| Symptom sensitivity (per point) | 10.1 (3.5) |

| Hormone therapy before FMP (vs. no), No. (%) | 179 (12.3) |

FMP, final menstrual period; BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression.

Except age at FMP and general health status all other covariates represented baseline values.

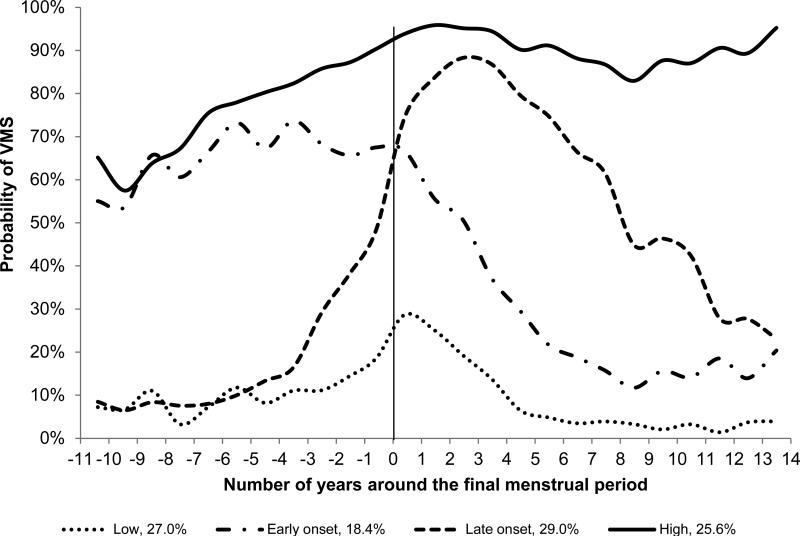

Four distinct trajectory patterns for the occurrence of VMS were identified (Figure 1): 27.0% of women had consistently low probability of VMS occurrence with a slight increase around the FMP (Low), and 25.6% had a persistently high probability of VMS throughout the MT (High). The other two VMS trajectories were distinguished as Early onset (18.4%), with the probability of VMS occurring well before FMP but decreasing immediately after the FMP, and Late onset (29.0%) for whom the probability of VMS sharply increased just after the FMP and decreased later.

Figure 1.

Trajectories of Vasomotor Symptoms over the Menopause Transition VMS indicates vasomotor symptoms. Probability of VMS represents the average observed probability of VMS at each time point within each trajectory subgroup. No factors were included in the model.

Participant characteristics differed across VMS trajectory subgroups (Table 2). A number of sociodemographic, reproductive hormone, and psychosocial factors were significantly and independently associated with the VMS trajectories in multivariable models (Table 3). Relative to women in the low VMS group, women experiencing VMS early (Early onset VMS) were at a more advanced menopause stage at baseline, were older age at the time of FMP, had poorer health, and had higher baseline anxiety and depressive symptom scores; women experiencing VMS late (Late onset VMS) were more likely to be black, were less likely to have a flat E2 trajectory, were more likely to be current smokers, and were less likely to be obese. Women in the persistently High VMS group were characterized by less education, greater alcohol use, poorer health, higher depressive and anxiety symptoms, higher symptom sensitivity, more likely to be black and less likely to be Chinese, and a trend of having low levels of E2 before the FMP with gradual and slow decline over the MT. No adjusted associations were evident between VMS trajectory group and hormone use before the FMP, physical activity and financial strain.

Table 2.

Profile of VMS Trajectory Subgroups Based on the Unadjusted Model (n=1455)

| Characteristics | Low (n=400) | Early onset (n=247) | Late onset (n=435) | High (n=373) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E2 trajectory, No. (%)a | 0.10 | ||||

| High, high peak | 107 (26.7) | 60 (24.3) | 146 (33.6) | 101 (27.1) | |

| High, early decline | 57 (14.2) | 33 (13.4) | 57 (13.1) | 37 (9.9) | |

| Medium, flat | 193 (48.3) | 127 (51.4) | 182 (41.8) | 185 (49.6) | |

| Low, slow decline | 43 (10.8) | 33 (13.4) | 50 (11.5) | 50 (13.4) | |

| FSH trajectory, No. (%)a | 0.02 | ||||

| High rise | 171 (42.7) | 94 (38.0) | 197 (45.3) | 169 (45.3) | |

| Moderate rise | 199 (49.8) | 120 (48.6) | 212 (48.7) | 165 (44.2) | |

| Low rise | 30 (7.5) | 33 (13.4) | 26 (6.0) | 39 (10.5) | |

| Race/Ethnicity, No. (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| White | 191 (47.7) | 129 (52.2) | 215 (49.4) | 153 (41.2) | |

| Black | 64 (16.0) | 57 (23.1) | 106 (24.4) | 149 (40.0) | |

| Chinese | 58 (14.5) | 18 (7.3) | 41 (9.4) | 25 (6.7) | |

| Japanese | 59 (14.8) | 27 (10.9) | 50 (11.5) | 31 (8.3) | |

| Hispanic | 28 (7.0) | 16 (6.5) | 23 (5.3) | 15 (4.0) | |

| BMI category, No. (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| Normal weight | 176 (44.0) | 78 (31.6) | 201 (46.2) | 135 (36.2) | |

| Overweight | 78 (19.5) | 41 (16.6) | 88 (20.2) | 69 (18.5) | |

| Obese | 146 (36.5) | 128 (51.8) | 146 (33.6) | 169 (45.3) | |

| Age at FMP, median (IQR) | 52.3 (50.1, 54.0) | 52.7 (50.3, 54.2) | 51.8 (50.1, 53.6) | 52.1 (50.3, 54.1) | 0.02 |

| Menopause status, No. (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| Premenopause | 258 (64.5) | 118 (47.8) | 250 (57.5) | 194 (52.0) | |

| Early perimenopause | 142 (35.5) | 129 (52.2) | 185 (42.5) | 179 (48.0) | |

| Physical activity score, mean (SD) | 7.9 (1.8) | 7.5 (1.7) | 7.8 (1.7) | 7.5 (1.7) | 0.02 |

| Smoking status, No. (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| Never | 278 (69.5) | 147 (59.5) | 254 (58.4) | 211 (56.6) | |

| Past | 33 (8.3) | 40 (16.2) | 69 (15.9) | 68 (18.2) | |

| Current | 89 (22.3) | 60 (24.3) | 112 (25.7) | 94 (25.2) | |

| Alcohol servings per week use, No. (%) | 0.68 | ||||

| None | 217 (54.2) | 131 (53.0) | 214 (49.2) | 179 (48.0) | |

| ≤1 | 38 (9.5) | 27 (10.9) | 45 (10.3) | 36 (9.7) | |

| 1-7 | 103 (25.8) | 56 (22.7) | 120 (27.6) | 106 (28.4) | |

| >7 | 42 (10.5) | 33 (13.4) | 56 (12.9) | 52 (13.9) | |

| General health status, No. (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| Excellent | 103 (25.8) | 24 (9.7) | 89 (20.5) | 45 (12.1) | |

| Very good | 153 (26.3) | 96 (38.9) | 199 (45.7) | 141 (37.8) | |

| Good | 105 (26.3) | 92 (37.2) | 109 (25.1) | 127 (34.0) | |

| Fair/Poor | 39 (9.8) | 35 (14.2) | 38 (8.7) | 60 (16.1) | |

| Difficulty paying for basics, No. (%) | 0.02 | ||||

| Not hard | 267 (66.8) | 144 (58.3) | 288 (66.2) | 218 (58.4) | |

| Very/somewhat hard | 133 (33.2) | 103 (41.7) | 147 (33.8) | 155 (41.6) | |

| Educational attainment, No. (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| ≥College | 218 (54.5) | 105 (42.5) | 207 (47.6) | 149 (40.0) | |

| <College | 182 (45.5) | 142 (57.5) | 228 (52.4) | 224 (60.0) | |

| Depressive symptoms scores on the CES-D Scale, mean (SD) | 7.6 (7.7) | 11.7 (9.1) | 8.7 (8.2) | 12.7 (10.4) | <0.001 |

| Anxiety ≥4 symptoms, No. (%) | 44 (11.0) | 66 (26.7) | 54 (12.4) | 116 (31.1) | <0.001 |

| Symptom sensitivity, mean (SD) | 9.5 (3.6) | 10.3 (3.5) | 9.9 (3.4) | 10.9 (3.3) | <0.001 |

| Hormone use before FMP, No. (%) | 43 (10.8) | 37 (15.0) | 44 (10.1) | 55 (14.8) | 0.09 |

VMS, Vasomotor symptoms; E2, Estradiol; FMP, FSH, follicle stimulating hormone; BMI: body mass index (final menstrual period; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression.

Trajectory subgroups over the menopause transition

Table 3.

Adjusted Odds Ratios of Belonging to a VMS Trajectory Relative to a Low VMS Trajectory Subgroupa (n=1455)

| Predictors | Early onset VMS (n=243) | Late onset VMS (n=424) | High VMS (n=383) |

|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI)b | OR (95% CI)b | OR (95% CI)b | |

| E2 trajectory | |||

| High, high peak | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| High, early rise | 0.92 (0.39, 2.16) | 0.71 (0.42,1.21) | 0.77 (0.42, 1.40) |

| Medium, flat | 1.15 (0.67, 1.98) | 0.65 (0.43, 0.97) | 0.86 (0.56, 1.32) |

| Low, slow decline | 1.59 (0.73, 3.47) | 1.01 (0.56, 1.82) | 1.71 (0.94, 3.14) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| White | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Black | 0.98 (0.50, 1.90) | 1.93 (1.13, 3.28) | 3.25 (1.95, 5.43) |

| Chinese | 0.65 (0.20, 2.11) | 0.50 (0.22, 1.14) | 0.39 (0.16, 0.96) |

| Japanese | 0.68 (0.23, 1.98) | 0.99 (0.44, 2.19) | 0.58 (0.25, 1.33) |

| Hispanic | 1.10 (0.20, 5.89) | 1.01 (0.29, 3.56) | 1.69 (0.35, 8.14) |

| BMI | |||

| Normal | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Overweight | 1.02 (0.53, 1.96) | 0.85 (0.54, 1.34) | 0.96 (0.60, 1.56) |

| Obese | 1.29 (0.72, 2.29) | 0.56 (0.36, 0.87) | 0.66 (0.42, 1.03) |

| Age at FMP (per yr) | 1.19 (1.08, 132) | 0.97 (0.91, 1.03) | 1.02(0.96, 1.10) |

| Menopause status | |||

| Premenopause | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Early perimenopause | 2.19 (1.37, 3.52) | 1.24 (0.87, 1.77) | 1.33 (0.93, 1.91) |

| Physical activity score (per point) | 1.00 (0.86, 1.15) | 0.96 (0.86, 1.06) | 0.95 (0.86, 1.06) |

| Smoking status | |||

| Never | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Past | 1.31 (0.77, 2.23) | 1.20 (0.79, 1.83) | 1.17 (0.76, 1.80) |

| Current | 1.90 (0.90, 4.03) | 1.81 (1.01, 3.25) | 1.29 (0.71, 2.34) |

| Alcohol servings per week use | |||

| None | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| ≤1 | 1.30 (0.64, 2.67) | 1.43 (0.81, 2.53) | 1.17 (0.62, 2.20) |

| 1-7 | 1.14 (0.64, 2.03) | 1.35 (0.89, 2.06) | 1.74 (1.13, 2.67) |

| >7 | 1.87 (0.88, 4.02) | 1.43 (0.79, 2.57) | 1.94 (1.06, 3.53) |

| General health status | |||

| Excellent | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Very good | 2.29 (1.12, 4.69) | 1.64 (1.06, 2.53) | 1.75 (1.07, 2.86) |

| Good | 3.44 (1.59, 7.48) | 1.15 (0.68, 1.95) | 1.74 (0.99, 3.05) |

| Fair/Poor | 2.89 (1.07, 7.83) | 0.82 (0.38, 1.76) | 2.10 (1.03, 427) |

| Difficulty paying for basics | |||

| Not hard | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Very/somewhat hard | 0.83 (0.49, 1.42) | 0.95 (0.65, 1.41) | 0.89 (0.60, 1.32) |

| Educational attainment | |||

| ≥College | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| <College | 1.49 (0.92, 2.42) | 1.29 (0.98, 1.89) | 1.81 (1.23, 2.64) |

| Depressive symptoms scores on the CES-D Scale (per point) | 1.05 (1.02, 1.08) | 1.02 (1.00, 1.05) | 1.05 (1.02, 1.08) |

| Anxiety symptoms score | |||

| 0-3 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| ≥4 | 2.26 (1.21, 4.22) | 0.83 (0.44, 1.54) | 2.37 (1.39, 4.05) |

| Symptom sensitivity (per point) | 1.03 (0.97, 1.10) | 1.01 (0.96, 1.06) | 1.10 (1.05, 1.16) |

| Hormone use before FMP | |||

| No | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 1.80 (0.94, 3.58) | 0.96 (0.53, 1.74) | 1.44 (0.82, 2.53) |

OR, Odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; VMS, menopausal vasomotor symptoms; BMI, body mass index; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression, FMP, final menstrual period.

All listed predictors and site were adjusted in the model as time-stable covariates.

An OR exceeding 1.0 indicates greater likelihood of belonging to the respective VMS trajectory subgroup rather than the Low VMS trajectory subgroup (n=405) compared to the reference group or per unit increase, an OR less than 1.0 indicates decreased likelihood of belonging to the respective VMS trajectory group than the Low VMS trajectory subgroup. Bold font indicates P value <.05.

When we included FSH trajectories in the group-based VMS trajectory model instead of E2 trajectories, similar associations between participant characteristics and VMS trajectory subgroups were found (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 3). FSH levels did not distinguish VMS subgroups with the exception of the High VMS subgroup being more likely to have high FSH levels (relative to the Low VMS group).

Discussion

In this large longitudinal observational study of a multi-racial/ethnic cohort of women transitioning through menopause, we identified four distinct patterns of VMS: women with a consistently low probability of having VMS throughout the MT, women with a consistently high probability of having VMS, women with early onset of VMS in the decade prior to the FMP with cessation thereafter, and women with late onset of VMS after the FMP with VMS gradually declining over most of the decade following the FMP. Relatively equal proportions of women exhibited the four distinct patterns of VMS. This work challenges the long held assumption that most women experience VMS for the few years around the FMP and then cease thereafter. Conversely, it shows that VMS patterns are heterogeneous and consistent with prior work,5 VMS typically last for a decade or longer.

Women's characteristics distinguished their likelihood of exhibiting specific VMS trajectories. Women with Late onset VMS were less likely to have a medium level and relatively flat E2 trajectory across the MT, suggesting that dynamic fluctuations in E2 may be relevant to the occurrence of VMS occurring directly around and following the FMP. There was a trend that consistently High VMS groups were more likely to have low levels of E2 across the MT, supporting the hypothesis that low levels of E2 are important for VMS occurrence, particularly VMS that occur early and persistently. Further, similar to prior reports, a greater rise in FSH levels was associated with a greater likelihood of experiencing VMS.7 The dynamics of E2 and VMS were correlated but not perfectly, consistent with clinical observations that women respond to different exogenous doses of E2 for VMS management and indicating E2 alone is not the complete mechanistic explanation for VMS symptoms.26,27 Changes in other reproductive hormone levels and/or intracellular and central nervous system processes that may be variably triggered by the hormone dynamics warrant further investigation to elucidate the biological basis of VMS.

In addition to hormonal factors, other factors distinguished the VMS trajectories. Women with Early onset VMS were more likely to have elevated baseline depressive symptoms and anxiety, poorer health and older age at menopause. This may reflect in part the heightened vulnerability to, perception of, and reporting of symptoms related to negative affect.28,29,30,31,32 In contrast, lower BMI, black race/ethnicity, and current smoking distinguished women in the Late onset VMS subgroup. Prior work has indicated that women with a higher BMI were more likely to report VMS,1,8 particularly in the pre- and early peri-menopause, and that body fat may in fact be protective with respect to VMS later in the transition.13 Consistent with this notion, obese women were prevalent among the women experiencing VMS early (51.8%) or persistently highly throughout the MT (45.3%). Notably, women with the onset of their VMS late in the transition (Late onset subgroup) were significantly less likely to be obese (relative to the Low VMS subgroup). Smoking was important in Late onset VMS subgroup. Smoking has been reported to increase hot flashes probably by direct effect of nicotine binding to nicotinic receptors in the hypothalamus.33 Notably, the women in the Late onset VMS group were both more often smokers and experienced a dramatic E2 decline immediately around the FMP.

Women in the consistently High VMS group were characterized by lower education and more moderate and heavy alcohol use, refining the understanding of previously noted educational gradients in VMS.1,28,34 Increased moderate and heavy alcohol use in this subgroup is consistent with observations that past alcohol consumption is associated with ever having VMS,35 which may result from thermoregulatory mechanisms that trigger hot flashes and sweating.36

Black women were over-represented in the persistently High VMS subgroup and the Late onset subgroups and Chinese women in the low VMS subgroup. The reason for these racial/ethnic differences is not fully understood. Black women have reported more persistent5 and more bothersome VMS.37 Many potential explanatory factors were controlled, including BMI, hormones, psychosocial factors, and socioeconomic factors. While BMI was controlled, body fat distribution was not considered, which vary by racial/ethnic group and are linked to VMS.38

These identified trajectories of VMS have been shown to be associated with subclinical cardiovascular disease.39 In other studies, the pattern of VMS has been shown to be associated with the risk of cardiovascular events in post-menopausal women.40 VMS patterns may be related to a variety of relevant clinical outcomes. Further investigation to clarify the potential impact of menopausal symptom presentation on subsequent morbidity and mortality is needed. Genetic factors may be involved and should be considered in future work, which may in turn inform development of novel pharmacogenetic regimens.

SWAN is one of the largest and longest racially/ethnically diverse prospective longitudinal studies of the MT, and our study sample had more than 12 annual observations per woman. The community-based study sample allows generalizability, and the use of standard instruments increases the validity of the study results. Group-based trajectory modeling took into account the heterogeneity of the study population and allowed us to identify statistically sound and scientifically plausible groupings. The availability of pre- and post-menopausal observations and within-woman duration allowed us to evaluate trajectories of VMS across the MT. Our consideration of racial/ethnic-specific definitions of overweight and obesity allowed us greater accuracy in the evaluation of BMI and its associations with VMS.

The study had limitations, including the annual serum blood draw that may have increased potential measurement error, especially when serum was obtained outside the early follicular phase. VMS were reported annually, which is a strength, but were recalled over the prior two weeks. While often used in epidemiologic studies, questionnaire measures of VMS are less desirable than diary or physiologic measures.41 Together, imprecision and underreporting of symptoms may have occurred.28 Women with surgical menopause were excluded from the analysis which precludes our findings’ application in these women. Finally, the relatively small numbers of women in certain racial/ethnic groups may limit the generalizability of findings in these groups and may have resulted in inadequate statistical power to detect some associations as statistically significant.

Conclusions

These results demonstrate that the occurrence in VMS has distinct temporal patterns that are not predicted by hormone use, physical activity, or financial hardship. However, hormones, race/ethnicity, BMI, education, smoking, drinking alcohol, general health status, anxiety and depression appear to have a strong relation to both the timing and the persistence of VMS in a diverse population of mid-aged women. Interventions to reduce VMS can both be tailored to address those specific factors contributing to her VMS and be targeted to women who are most affected by persistent and burdensome VMS across the MT. Information about a woman's race/ethnicity, hormonal status, overall health status, and psychosocial profile can help a woman predict what course her VMS may follow. Additional investigation into genetic, lifestyle and symptom characteristics that define subgroups of women with different vasomotor trajectories may allow for the development of new and effective behavioral and pharmacologic treatments tailored to these trajectories.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

Funding/Support: The Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN) has grant support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), DHHS, through the National Institute on Aging (NIA), the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) and the NIH Office of Research on Women's Health (ORWH) (Grants U01NR004061; U01AG012505, U01AG012535, U01AG012531, U01AG012539, U01AG012546, U01AG012553, U01AG012554, U01AG012495). The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIA, NINR, ORWH or the NIH.

Dr. Brooks reported receiving grant support from Gilead Sciences, Inc.; Dr. Joffe reported receiving grant support from Teva/Cephalon, Merck and serving as an advisory/consultant to Merck, Noven, Mitsubishi, Tanabe. Dr. Tepper reported receiving grant support from Pfizer.

Footnotes

Clinical Centers: University of Michigan, Ann Arbor – Siobán Harlow, PI 2011 – present, MaryFran Sowers, PI 1994-2011; Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA – Joel Finkelstein, PI 1999 – present; Robert Neer, PI 1994 – 1999; Rush University, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL – Howard Kravitz, PI 2009 – present; Lynda Powell, PI 1994 – 2009; University of California, Davis/Kaiser – Ellen Gold, PI; University of California, Los Angeles – Gail Greendale, PI; Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY – Carol Derby, PI 2011 – present, Rachel Wildman, PI 2010 – 2011; Nanette Santoro, PI 2004 – 2010; University of Medicine and Dentistry – New Jersey Medical School, Newark – Gerson Weiss, PI 1994 – 2004; and the University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA – Karen Matthews, PI.

NIH Program Office: National Institute on Aging, Bethesda, MD – Winifred Rossi 2012 - present; Sherry Sherman 1994 – 2012; Marcia Ory 1994 – 2001; National Institute of Nursing Research, Bethesda, MD – Program Officers.

Central Laboratory: University of Michigan, Ann Arbor – Daniel McConnell (Central Ligand Assay Satellite Services).

Coordinating Center: University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA – Maria Mori Brooks, PI 2012 - present; Kim Sutton-Tyrrell, PI 2001 – 2012; New England Research Institutes, Watertown, MA - Sonja McKinlay, PI 1995 – 2001.

Steering Committee: Susan Johnson, Current Chair; Chris Gallagher, Former Chair

Additional Contributions: We thank the study staff at each site and all the women who participated in SWAN.

Disclosure Statement:

No other disclosures were reported.

References

- 1.Gold EB, Colvin A, Avis N, et al. Longitudinal analysis of the association between vasomotor symptoms and race/ethnicity across the menopausal transition: Study of women's health across the nation. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(7):1226–1235. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woods NF, Mitchell ES. Symptoms during the perimenopause: Prevalence, severity, trajectory, and significance in women's lives. Am J Med. 2005;118(Suppl 12B):14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avis NE, Colvin A, Bromberger JT, et al. Change in health-related quality of life over the menopausal transition in a multiethnic cohort of middle-aged women: Study of women's health across the nation. Menopause. 2009;16(5):860–869. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181a3cdaf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams RE, Kalilani L, DiBenedetti DB, Zhou X, Fehnel SE, Clark RV. Healthcare seeking and treatment for menopausal symptoms in the united states. Maturitas. 2007;58(4):348–358. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Avis NE, Crawford SL, Greendale G, et al. Duration of menopausal vasomotor symptoms over the menopause transition. JAMA Intern Med. 2015 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.8063. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.8063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mishra GD, Dobson AJ. Using longitudinal profiles to characterize women's symptoms through midlife: Results from a large prospective study. Menopause. 2012;19(5):549–555. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3182358d7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hutton JD, Jacobs HS, James VH. Steroid endocrinology after the menopause: A review. J R Soc Med. 1979;72(11):835–841. doi: 10.1177/014107687907201109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Randolph JF, Jr., Sowers M, Bondarenko I, et al. The relationship of longitudinal change in reproductive hormones and vasomotor symptoms during the menopausal transition. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(11):6106–6112. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thurston RC, Chang Y, Mancuso P, Matthews KA. Adipokines, adiposity, and vasomotor symptoms during the menopause transition: Findings from the study of women's health across the nation. Fertil and Steri. 2013;100(3):793–800. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sowers MF, Crawford SL, Sternfeld B, et al. SWAN: a multi- center, multi-ethnic, community-based cohort study of women and the menopausal transition. In: Lobo RA, Kelsey J, Marcus R, editors. Menopause: Biology and Pathobiology. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 2000. pp. 175–188. [Google Scholar]

- 11.van den Beld AW, de Jong FH, Grobbee DE, Pols HA, Lamberts SW. Measures of bioavailable serum testosterone and estradiol and their relationships with muscle strength, bone density, and body composition in elderly men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85(9):3276–3282. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.9.6825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tepper PG, Randolph JF, Jr., McConnell DS, et al. Trajectory clustering of estradiol and follicle-stimulating hormone during the menopausal transition among women in the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN). J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(8):2872–2880. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Low S, Chin MC, Ma S, Heng D, Deurenberg-Yap M. Rationale for redefining obesity in asians. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2009;38(1):66–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shiwaku K, Anurad E, Enkhmaa B, et al. Overweight japanese with body mass indexes of 23.0-24.9 have higher risks for obesity-associated disorders: A comparison of Japanese and Mongolians. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28(1):152–158. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Funatogawa I, Funatogawa T, Nakao M, Karita K, Yano E. Changes in body mass index by birth cohort in Japanese adults: Results from the national nutrition survey of Japan 1956-2005. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38(1):83–92. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pan WH, Lee MS, Chuang SY, Lin YC, Fu ML. Obesity pandemic, correlated factors and guidelines to define, screen and manage obesity in Taiwan. Obes Rev. 2008;9(Suppl 1):22–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferris BG. Epidemiology standardization project (american thoracic society). Am Rev Respir Dis. 1978;118(6 Pt 2):1–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sternfeld B, Ainsworth BE, Quesenberry CP. Physical activity patterns in a diverse population of women. Prev Med. 1999;28(3):313–323. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neugarten BL, Kraines RJ. “Menopausal symptoms” in women of various ages. Psychosom Med. 1965;27:266–273. doi: 10.1097/00006842-196505000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bromberger JT, Kravitz HM, Chang Y, et al. Does risk for anxiety increase during the menopausal transition? Study of women's health across the nation. Menopause. 2013;20(5):488–495. doi: 10.1097/GME.0b013e3182730599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psych Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barsky AJ, Goodson JD, Lane RS, Cleary PD. The amplification of somatic symptoms. Psychosom Med. 1988;50(5):510–519. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198809000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nagin DS. Group-based modeling of development. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones BL, Nagin DS, Roeder K. A SAS procedure based on mixture models for estimating developmental trajectories. Social Methods Res. 2001;29(3):374–393. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones BL, Nagin DS. Advances in group-based trajectory modeling and an SAS procedure for estimating them. Social Methods Res. 2007;35(4):542–571. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lasley BL, Santoro N, Randolph JF, et al. The relationship of circulating dehydroepiandrosterone, testosterone, and estradiol to stages of the menopausal transition and ethnicity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(8):3760–3767. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.8.8741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lasley BL, Chen J, Stanczyk FZ, et al. Androstenediol complements estrogenic bioactivity during the menopausal transition. Menopause. 2012;19(6):650–657. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31823df577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thurston RC, Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, Sherwood A. Emotional antecedents of hot flashes during daily life. Psychosom Med. 2005;67(1):137–146. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000149255.04806.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hanisch LJ, Hantsoo L, Freeman EW, Sullivan GM, Coyne JC. Hot flashes and panic attacks: A comparison of symptomatology, neurobiology, treatment, and a role for cognition. Psychol Bull. 2008;134(2):247–269. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berendsen HH. The role of serotonin in hot flushes. Maturitas. 2000;36(3):155–164. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(00)00151-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deecher D, Andree TH, Sloan D, Schechter LE. From menarche to menopause: Exploring the underlying biology of depression in women experiencing hormonal changes. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33(1):3–17. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thurston RC, Christie IC, Matthews KA. Hot flashes and cardiac vagal control: A link to cardiovascular risk? Menopause. 2010;17(3):456–461. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181c7dea7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cochran CJ, Gallicchio L, Miller SR, Zacur H, Flaws JA. Cigarette smoking, androgen levels, and hot flushes in midlife women. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(5):1037–1044. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318189a8e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thurston RC, Bromberger JT, Joffe H, et al. Beyond frequency: Who is most bothered by vasomotor symptoms? Menopause. 2008;15(5):841–847. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e318168f09b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hunter MS, Gentry-Maharaj A, Ryan A, et al. Prevalence, frequency and problem rating of hot flushes persist in older postmenopausal women: Impact of age, body mass index, hysterectomy, hormone therapy use, lifestyle and mood in a cross-sectional cohort study of 10,418 British women aged 54-65. BJOG. 2012;119(1):40–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.03166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Deecher DC, Dorries K. Understanding the pathophysiology of vasomotor symptoms (hot flushes and night sweats) that occur in perimenopause, menopause, and postmenopause life stages. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2007;10(6):247–257. doi: 10.1007/s00737-007-0209-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thurston RC, Sowers MR, Sutton-Tyrrell K, et al. Abdominal adiposity and hot flashes among midlife women. Menopause. 2008;15(3):429–434. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31815879cf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thurston RC, Sowers MR, Chang Y, et al. Adiposity and reporting of vasomotor symptoms among midlife women: The study of women's health across the nation. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(1):78–85. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thurston RC, ElKhoudary SR, Tepper PG, Jackson EA, Joffer H, Chen HY, Matthews KA. Trajectories of vasomotor symptoms and carotid intima media thickness in the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation. Stroke. 2016;47(1):12–7. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.010600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Szmuilowicz ED, Manson JE, Rossouw JE, et al. Vasomotor symptoms and cardiovascular events in postmenopausal women. Menopause (New York, NY) 2011;18(6):603–610. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3182014849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fu P, Matthews KA, Thurston RC. How well do different measurement modalities estimate the number of vasomotor symptoms? Findings from the study of women's health across the nation flashes study. Menopause. 2014;21(2):124–13. doi: 10.1097/GME.0b013e318295a3b9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.