Abstract

Purpose

To describe and assess an automated, normalization method for identifying sentinel (septal) regions of myocardial dysfunction in non-ischemic, non-valvular dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) using an unprecedented combination of the Navigator-gated 3D Spiral Displacement Encoding with Stimulated Echoes (DENSE) MRI, Radial Point Interpolation (RPIM) and Multiparametric Strain Z-Score (MPZS).

Materials and Methods

Navigator-gated 3D Spiral DENSE, in a 1.5 Tesla MRI machine, was used for acquiring the displacement encoded complex images, MR Analytical Software System (MASS) for automated boundary detection and automated meshfree RPIM for left-ventricular (LV) myocardial strain computation to analyze MPZS in 36 subjects (with N=17 DCM patients). Pearson’s r correlation established relations between global/sentinel MPZS and EF. The time taken for combined RPIM-MPZS computations was recorded.

Results

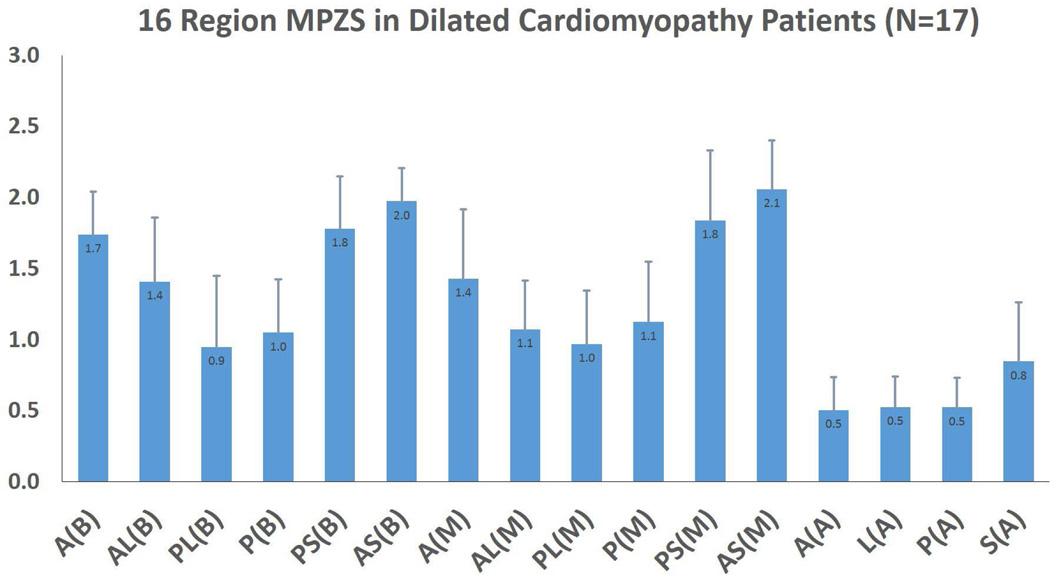

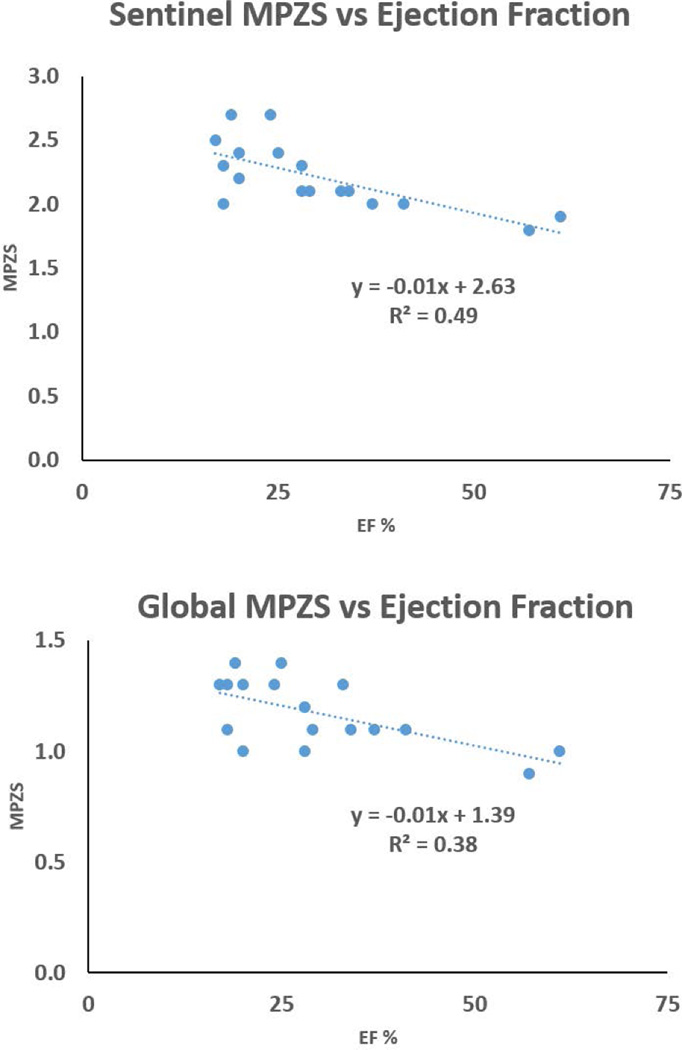

Maximum MPZS differences were seen between anteroseptal and posterolateral regions in the base (2.0 ± 0.3 versus 0.9 ± 0.5) and the mid-wall (2.1 ± 0.4 versus 1.0 ± 0.4). These regional differences were found to be consistent with historically documented septal injury in non-ischemic DCM. Correlations were 0.6 between global MPZS and EF, and 0.7 between sentinel MPZS and EF. The time taken for combined RPIM-MPZS computations per subject was 18.9 ± 5.9 seconds.

Conclusions

Heterogeneous contractility found in the sentinel regions with the current automated MPZS computation scheme and the correlation found between MPZS and EF may lead to the creation of a new clinical metric in LV DCM surveillance.

Keywords: cardiac mechanics, contractile dysfunction, dilated cardiomyopathy, DENSE, MPZS, RPIM

Current task-force statistics from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) and others show that the prevalence of dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) in the United States is approximately 36 people per 100,000, causing numerous hospitalizations for heart failure and deaths each year [1–3]. DCM is one of the most common causes of heart failure (HF) [1, 4]. Patients diagnosed with DCM in clinical HF have dilated, impaired left-ventricles (LV), ejection fractions (EF) less than 40%, all of which is generally accompanied by sentinel region (implying the septum) myocardial dysfunction [5, 6]. Hence, we endeavored to develop an appropriate metric, the automated Multiparametric Strain Z-Score (MPZS), for tracking the ventricular remodeling that may be related to adverse outcomes such as surgical intervention, end-organ failure or even sudden death in DCM [1, 5, 6].

The primary objective of this study was to formulate an automated metric for identifying sentinel (septal) regions of myocardial dysfunction that could be used for indexing the severity of disease in non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. There are three important steps undertaken in assignment of this metric and brief descriptions of these steps are given in the following. The first step involves image acquisition where Displacement Encoding with Stimulated Echoes (DENSE) is a higher resolution MR imaging sequence which measures tissue displacement from a fixed encoding point at end-diastole [7–9]. Tissue displacements at the fixed spatial locations were obtained using fast automated unwrapping of the phases, where phase shifts occur between initial position encoding and readout [8–10]. The greatest advantage of DENSE is the automated phase unwrapping in complex images that enables rapid 3D displacement analysis [8, 9, 11–13]. The second step involved automated image-based boundary detection using the MR Analytical Software System (MASS) (Leiden University, Leiden, NL) and 3D reconstruction using an in-house C++ algorithm [14–18]. The third and last step was the development of an automated, high resolution LV myocardial function-based metric, the MRI-based Multiparametric Strain Z-Score (MPZS) [14, 19–21]. While a number of well-validated scoring methods for assessing clinical HF risks exist [22–28], a validated model of risk assessment based on an individual patient’s LV biomechanics is yet to become mainstream in clinical HF diagnosis [5, 14, 20, 21]. Hence, we proposed to develop the MPZS metric based on normalization of several individual strain components computed with the meshfree Radial Point Interpolation Method (RPIM) and combined into a single multiparametric composite index. As RPIM is relatively new in numerical analysis techniques, we endeavored to quickly compare the strains generated to a more traditional finite element analysis (FEA) method known as Measurement Analysis (MEA). MEA, which has been previously used for MPZS analysis, is based on higher order polynomial interpolation of spatial variables, also commonly known as the p-version in FEA [5, 14, 16, 20, 29–31].

Materials and Methods

Human Subject Recruitments

A total of 36 subjects (normals = 19, DCM patients = 17) were imaged in a 1.5 Tesla Avanto (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) MRI scanner using the 3D Navigator-gated Spiral DENSE sequence [10]. All subjects signed informed consents in accordance with the university’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) guidelines. MRI data from the normal volunteer data formed the healthy subjects’ database for normalizing patient strains and computing MPZS [7, 14, 20]. The normal subjects filled out a questionnaire approved by the IRB that established absence of any form of cardiac disease.

DENSE Acquisition and Protocols

Navigator-gated 3D DENSE data was acquired with displacement encoding applied in two orthogonal in-plane directions and one through plane direction. A flexible, anterior 6-channel body matrix RF coil (Siemens Healthcare, Erlanger, Germany) was used for receiving signals [7–9]. Typical imaging parameters included FOV of 380 × 380 mm2, TE of 1.04 ms, TR of 15 ms, matrix size of 128 × 128 pixels, 2.97 × 2.97 × 5 mm3 voxel spacing, 6 mm slice thickness, 21 cardiac phases, encoding frequency of 0.6 cycles/cm, simple 4-points encoding [32], 3-points phase cycling for artifact suppression [10, 12]. The acquisition time was about 10 minutes, depending on the heart rate and navigator acceptance rate of individual subject.

Continuous monitoring of heart rates (HR) and blood pressures (BP) were conducted during the scans for both patients and healthy subjects. Additionally patients underwent Doppler echocardiography tests for heart failure analysis and were assigned an NYHA class by their physicians. The time taken for scanning each subject was recorded.

Segmentation

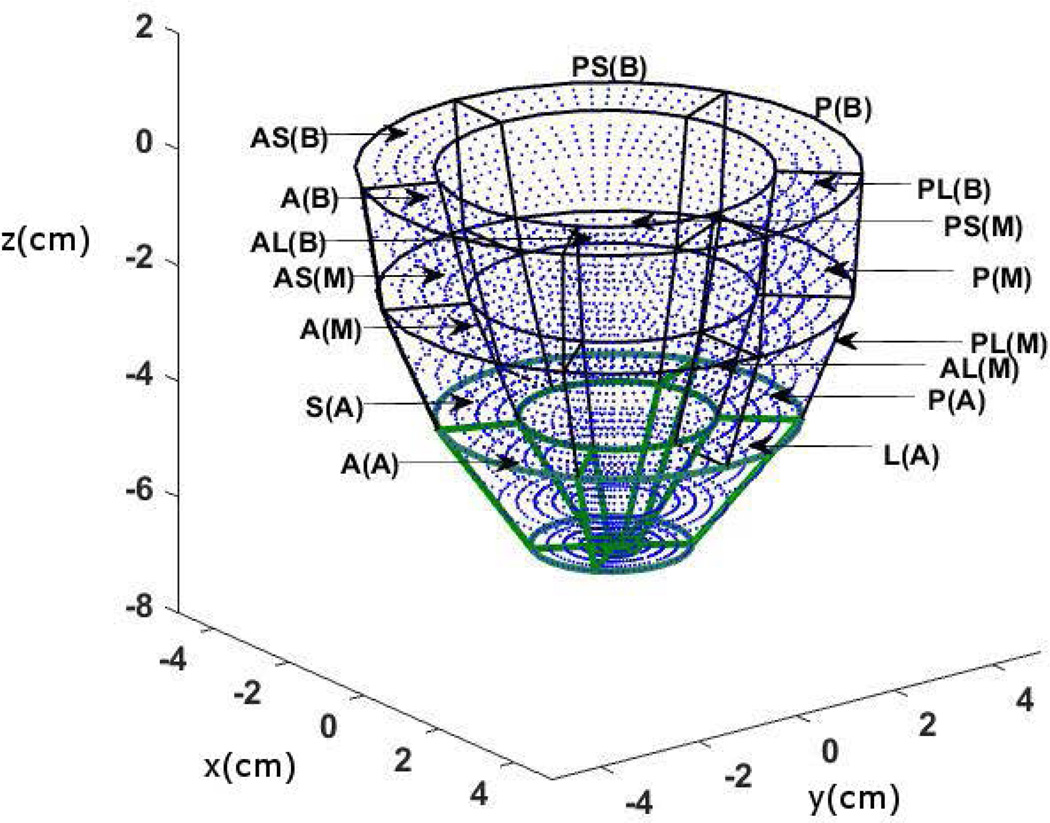

Offline automated segmentation of the myocardium was facilitated using MASS [17, 18] and automated phase unwrapping in DENSE and reconstruction of 3D volume splines and surfaces for 3D geometry accomplished with a C++ in-house application [7, 14, 19, 31]. The automated MASS detection of endocardial and epicardial boundaries is based on an Active Appearance Motion Model (AAMM). Manual contours were first defined at end-diastole and end-systole in multiple slices from base to apex and the AAMMs created using a leave-one-out procedure [17, 18]. What follows is iteratively deforming the AAMM within statistical limits until an optimal match is found between the deformed AAMM and the underlying image (leave-out) data. The only manual intervention required for 3D reconstruction was identifying the anterior and posterior septal points at the RV boundary. This was followed by segmenting the LV plane into six regions and creating the 3D epicardial and endocardial wire frame meshes [14–16, 20]. The LV volume was then segmented into 16 AHA recommended segments for strain analysis with equally spaced intramural grid points as shown in Fig. 1 [33]. Ejection volume (EV), end-diastole volume (EDV), end-systole volume (ESV), EF and mass for all subjects (N=36) were computed using MASS [14–16, 20]. Computation of patient EF was also facilitated by clinical echocardiography tests and the results from MASS verified to lie within 10% variation of the echocardiography tests [34]. The approximate time (in minutes) for segmentation was recorded.

Meshfree Strain Analysis

Strain parameters in 3D (radial, circumferential and longitudinal) were computed using RPIM at each voxel in patient-specific DENSE magnitude image-based reconstructed 3D grid geometries. RPIM is a meshfree numerical analysis technique that facilitates fast multidimensional computation of Lagrangian strains [7, 31, 35–37]. DENSE-based RPIM computation was primarily designed as a model-based approach involving 4D analysis of motion with deformations and strains readily computed at a given point in the three spatial dimensions and the dimension of time [9, 12, 38]. Similar model-based and pointwise cardiac strain computation techniques have been used in previous DENSE studies [9, 10, 12]. Furthermore, the RPIM strains were computed at 16 circumferentially arranged cardiac segments in accordance with AHA segmentation guidelines [33]. The greatest advantage of RPIM lies in eluding intensive computational techniques like remeshing which can be the most time-consuming component of conventional finite element analysis (FEA). Thus, the combination of fully automated 3D tissue displacement and strain computation using meshfree RPIM was undertaken to delivers high-resolution MPZS analysis with minimum operator time and interaction. A brief description of RPIM is given next.

The core of the RPIM methodology involves a continuous displacement field function, u(x), passing through a group of scattered nodes, x, within a domain [7, 35, 36],

| (1) |

where p(x) is the matrix of monomial bases and b is vector of coefficients to which radial basis functions (RBF), B(x), with a as the coefficient vector, are added. It is the existence of B−1 for arbitrary scattered nodes that is considered a major advantage of RBFs [7]. The RBFs added were of the Multiquadrics (MQ) type [35–37]. Following developments of the deformation gradient tensor, F, and Lagrangian strain tensor, E, with RPIM are outlined extensively in previous literature [7, 31, 35–37].

Multiparametric Strain Z-Score Analysis

The computation scheme for MPZS is based on the normalization of individual strain components (circumferential, radial and longitudinal) combined into a single composite index. Each LV was segmented into 16 sub-regions with three levels and six annular divisions (anteroseptal, anterior, anterolateral, posterolateral, posterior and posteroseptal) per level (Fig. 1). The apex had four sub-regions (septal, anterior, lateral, and posterior) as outlined by the AHA guidelines on segmentation and shown in Fig. 1 [33]. The strain components were averaged and standard deviations computed for each of the 16 sub-regions for both healthy subjects and patients. The formula for computing sub-regional MPZS is given by,

| (2) |

where εr, εc and εl represents the patient-specific average strains, μn,r, μn,c and μn,l are the average strains and σn,r, σn,c and σn,c are standard deviations in healthy subjects at a given myocardial point in the radial, circumferential and longitudinal directions, respectively. It is noted that the εr, εc and εl strains have much lower magnitudes in dysfunction in comparison to those found in healthier populations [5, 6, 20, 39]. The terms εc-μn,c and εl-μn,l yield positive values and the negative of εr-μn,r yields a positive value. Ultimately, a computed z-score greater than zero implies a dysfunctional sub-region where it would be less than or equal to zero in a normally performing region [5, 14, 19–21]. MPZS therefore compares contractility to an established normal in the same myocardial sub-region in a database of healthy subjects.

Figure 1.

It is noted that two of the shear strain-based components, circumferential-longitudinal and longitudinal-radial, were not included in the MPZS composition due to issues of confounding and/or collinearity which can arise in a formula with multiple parameters [40, 41]. Multi-collinearity between the six independent strain components which were the three normal: circumferential, radial and longitudinal and the three shear: circumferential-longitudinal, longitudinal-radial and circumferential-radial strains were examined using Matlab (MathWorks, Natick, MA). The choice of adding the shear strain-based z-score components in the composite MPZS (Eqn. 2) was determined by the significance of correlation with the three normal strain z-scores. Additionally the circumferential-radial shear was unused due to abnormally high variations in inter-subject values. Previous studies have reported this variability where the likely cause is the inclusion of patients with high torsions between the endocardium and epicardium [38, 39, 42, 43].

The time taken for the combined computation of RPIM strains and final MPZS for each patient was recorded to show that strains and z-scores’ computation using our current methodology is much quicker than using traditional methods. The sentinel region of myocardial dysfunction was determined by the highest MPZS value among the 16 regions.

Rendering 3D MPZS Contour Maps

Along with automated RPIM and MPZS computations, rapid and automated rendering of MPZS surface maps with 3D visual formatting via Matlab were conducted [7, 8, 31]. Briefly, strains at the grid points shown in Fig. 1 were generated by interpolating the original voxel-based strain data, in DCM patients and normal subjects, and their composite MPZS computed (Eqn. 2). Local 3D epicardium and endocardium patches were then rendered using the four nearest grid point MPZS values to display myocardial surfaces segments. Such MPZS surface contour maps can be generated for both healthy and patient populations.

Statistical Analysis

Pearson’s r correlation was computed between patient global/sentinel MPZS and EF in an effort to show that MPZS is a metric of significance in DCM. Appendix A shows the means and standard deviations of normal strains computed with RPIM, compared to those computed with the more traditional MEA. It is noted that MPZS computed with MEA has traditionally included the circumferential and longitudinal strains, exclusive of radial strains [16, 29].

Results

Patient Details

Details of HR, BP and other demographic are given in Table 1. Specific details on DCM patients such as physician assigned NYHA classes are given in Table 1. Table 1 also shows the global/sentinel z-scores assigned to the N=17 DCM patients using the DENSE-RPIM-MPZS framework. The time taken for each scan was 15 ± 9 minutes.

Table I.

Demographic and Clinical Details of DCM Patient and Normal Subjects Summary

| ID | GN | Age years |

Weight lbs |

BPS mmHg |

BPD mmHg |

HR bpm |

EDV ml |

ESV ml |

EF % |

Mass gm |

NYHA Class |

Max MPZS |

Avg. MPZS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 70 | 180 | 65 | 102 | 67 | 332.1 | 235.8 | 29 | 205.7 | 2 | 2.1 | 1.1 |

| 2 | M | 70 | 177 | 67 | 106 | 73 | 203.5 | 147.3 | 28 | 173.9 | 2 | 2.1 | 1.2 |

| 3 | F | 54 | 162 | 62 | 106 | 90 | 254.8 | 191.9 | 25 | 154.0 | 3 | 2.4 | 1.4 |

| 4 | M | 46 | 202 | 66 | 111 | 64 | 237.3 | 156.6 | 34 | 196.5 | 3 | 2.1 | 1.1 |

| 5 | M | 59 | 163 | 78 | 115 | 80 | 231.5 | 167.3 | 28 | 201.9 | 2 | 2.3 | 1.0 |

| 6 | M | 59 | 167 | 75 | 104 | 82 | 301.8 | 228.4 | 24 | 175.7 | 2 | 2.7 | 1.3 |

| 7 | M | 42 | 210 | 60 | 104 | 52 | 260.4 | 213.2 | 18 | 215.0 | 2 | 2.3 | 1.3 |

| 8 | M | 61 | 157 | 90 | 130 | 74 | 384.9 | 318.6 | 17 | 229.0 | 2 | 2.5 | 1.3 |

| 9 | M | 61 | 157 | 82 | 118 | 70 | 392.7 | 315.2 | 20 | 254.7 | 2 | 2.2 | 1.3 |

| 10 | F | 40 | 115 | 60 | 100 | 80 | 324.3 | 261.4 | 19 | 185.3 | 2 | 2.7 | 1.4 |

| 11 | F | 67 | 265 | 75 | 125 | 67 | 277.1 | 162.5 | 41 | 202.4 | 2 | 2.0 | 1.1 |

| 12 | M | 59 | 230 | 70 | 125 | 66 | 288.1 | 181.7 | 37 | 248.2 | 2 | 2.0 | 1.1 |

| 13 | M | 42 | 256 | 65 | 117 | 80 | 572.3 | 524.2 | 18 | 299.0 | 3 | 2.0 | 1.1 |

| 14 | M | 49 | 237 | 80 | 125 | 83 | 139.0 | 52.5 | 57 | 133.5 | 2 | 1.8 | 0.9 |

| 15 | F | 53 | 180 | 84 | 145 | 95 | 124.1 | 82.7 | 33 | 149.5 | 3 | 2.1 | 1.3 |

| 16 | M | 59 | 256 | 72 | 121 | 63 | 97.1 | 36.3 | 61 | 187.5 | 2 | 1.9 | 1.0 |

| 17 | F | 37 | 152 | 63 | 110 | 72 | 126.7 | 73.2 | 20 | 124.4 | 3 | 2.4 | 1.0 |

| HF Avg. | 1:3 | 54.6 | 192.1 | 71.4 | 115.5 | 74.0 | 267.5 | 197.0 | 30.1 | 196.2 | 2.3 | 2.2 | 1.2 |

| SD | 10.4 | 43.5 | 9.1 | 12.0 | 10.7 | 118.3 | 118.4 | 13.3 | 45.0 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.3 | |

| HV Avg. | 1:0.7 | 46.1 | 164.2 | 75.0 | 121.8 | 70.0 | 147.0 | 52.1 | 64.7 | 124.9 | - | 0 | 0 |

| SD | 11.5 | 21.7 | 8.1 | 11.4 | 6.5 | 34.3 | 15.6 | 5.7 | 24.8 | - | 0 | 0 | |

Abbreviations: HF: heart failure, HV: healthy volunteer, GN: gender, BPS: blood pressure at end-diastole, BPS: blood pressure at end-systole, HR: heart rate, EDV: end-systole volume, EDV: end-diastole volume, EF: ejection fraction, MPZS: Multiparametric strain Z-Score, NYHA: New York Heart Association, Max MPZS: highest region MPZS, Avg. MPZS: averaged (16-region) MPZS.

Statistical Results

The correlation between all three normal global MPZS components were found not to be significant (p=0.1). However, significant correlation were found between circumferential and circumferential-longitudinal shear (r=0.7, p=0.007) and the longitudinal and longitudinal-radial shear (r=0.6, p=0.009) z-score components. Time taken for 3D automated myocardial segmentation was typically 15 minutes per patient. Time taken for phase unwrapping (displacement analysis) was 3.65 ± 1.95 minutes and depended on the short-axis stack size, where processing configuration included a 3.4 GHz Intel Core processor, 16 GB of RAM and a 64-bit operating system. Average MPZS were calculated for each of the 16 LV regions where the septal sub-regions were found to be the most consistently and heavily injured of all (Fig. 2). Some of the highest contrast in average MPZS was found between the basal anteroseptal and posterolateral sub-regions (2.0 ± 0.3 versus 0.9 ± 0.5, p=0.001), and between the mid-wall anteroseptal and posterolateral sub-regions (2.1 ± 0.4 versus 1.0 ± 0.4, p=0.001) as shown in Fig. 2. The time taken for combined computations of RPIM strains and MPZS was 18.9 ± 5.9 seconds per patient. In comparison, tissue tagging and strain analysis in tagged-MRI can take approximately 6–8 hours of processing time as reported in earlier studies [14, 20, 21]. Fig. 3 shows the relationship between global/sentinel MPZS and EF. A Pearson’s r correlation equal to 0.6 was obtained between global MPZS and EF and 0.7 was obtained between sentinel MPZS and EF. Appendix A shows the comparison of strains between the RPIM and MEA techniques.

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

Three-Dimensional Contouring

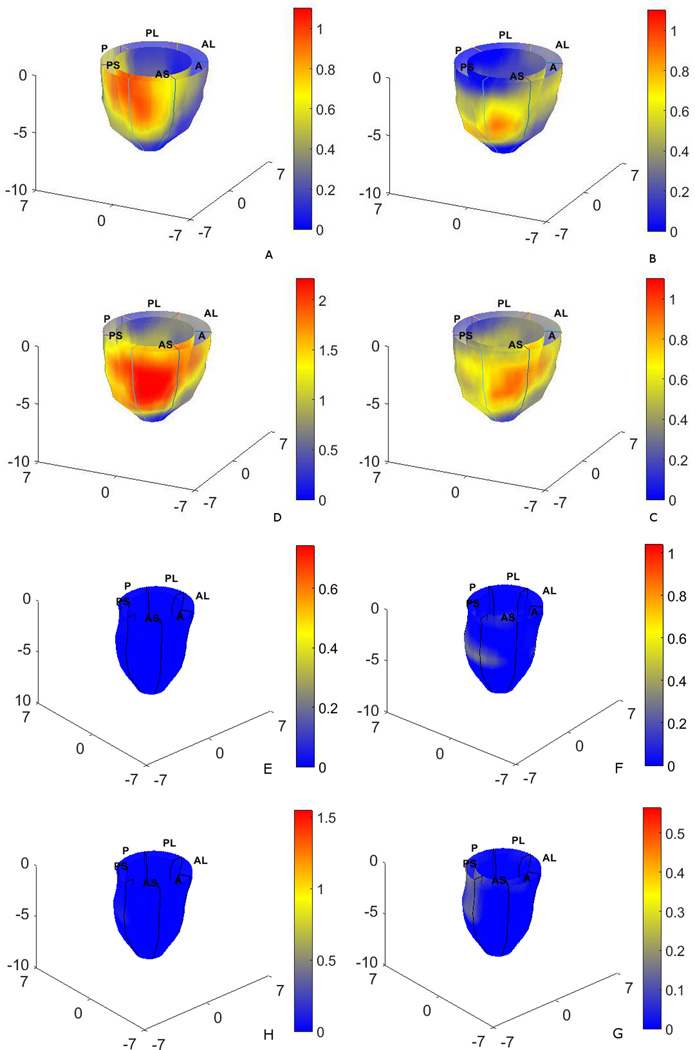

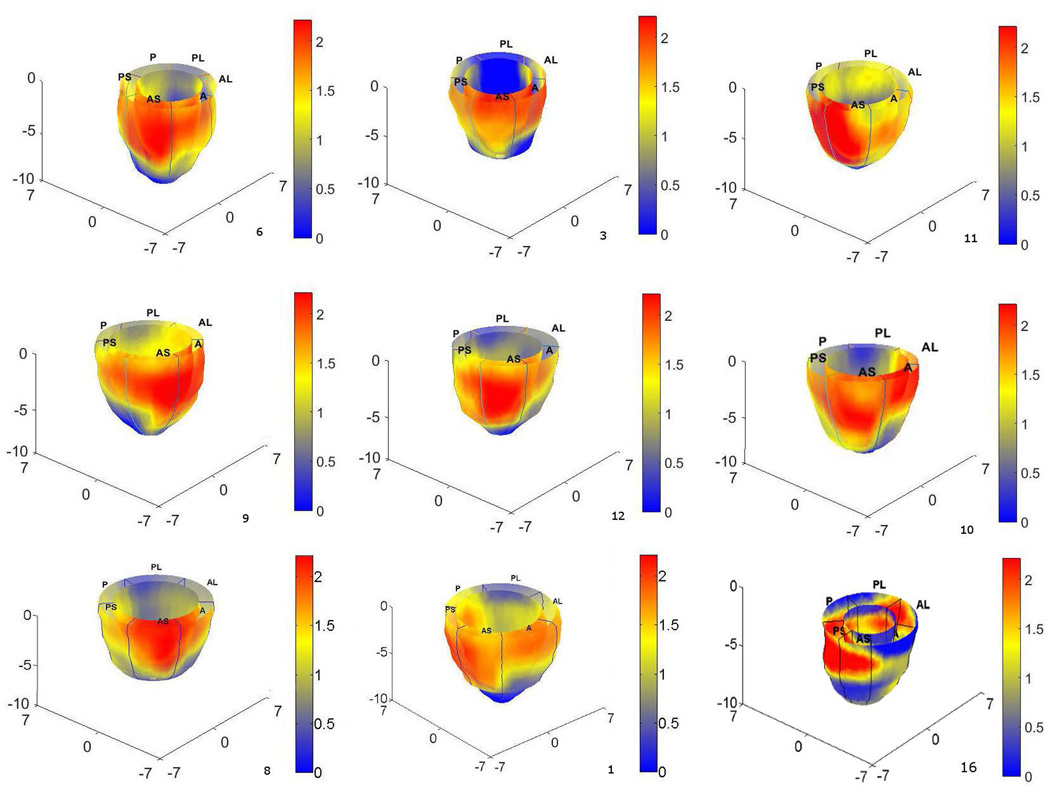

Fig. 4A–C shows contour maps of left-ventricular circumferential, longitudinal and radial strain-based MPZS on the epicardium and endocardium surfaces prior to summing for the final MPZS. Each strain-based z-score map individually reflects sentinel regions of dysfunction in a total of 16 regions. Fig. 4D shows the composite MPZS contours generated from summing the individual z-scores in the same patient. It is noted here that Fig. 4 shows the sum of normalized strains in one single patient. While Fig. 4 is indicative of how the normalized strains are summed to compute MPZS, the contributions of the three normalized strains may vary from case to case. The red and yellow zones in Fig. 4D indicate contractile dysfunction (MPZS > 0) and the zones in blue indicate normally functioning myocardium (MPZS ≤ 0). Similarly, Fig. 4E–G shows contour maps of the three normal strain-based MPZS and Fig. 4H shows the combined MPZS in a healthy subject. Shown in Fig. 5 are MPZS computed with the three normalized strains in nine patients with a consistent pattern of sentinel dysfunction. The last contour (bottom-right) in Fig. 5 is an interesting case where the patient was diagnosed with hypertrophy, as well. Indeed, the spread of heterogeneous dysfunction can be seen throughout the myocardium along with a thickening of the wall and a smaller endocardium.

Figure 4.

Figure 5.

Discussion

The foremost objective of this study was to conduct MPZS computations for identifying sentinel regions of dysfunction in DCM, by constructing patient-specific 3D DENSE-based grids, computing point-wise Lagrangian strains and combining multi-strain parameters into z-scores. Where MPZS might ultimately distinguish abnormal myocardial contractile patterns in comparison to normal ones in healthy subjects [5, 14, 19–21]. The primary finding of this study is the differences in regional MPZS values (between septal and lateral sub-regions) in HF patients established with the DENSE-RPIM-MPZS framework as shown in our artwork. A similar pattern was shown with a previous tagged-MRI study which showed similarly high septal MPZS compared to the lateral myocardial wall [5]. However, it is noted that MPZS strain parameters used in the previous study were different from the current, thus making trends in regional MPZS comparable between the studies rather than magnitude [14, 20, 35–37]. The Pearson’s correlation values between global/sentinel MPZS and EF show that strong relationships exists between the two metrics. However, the table does show a patient with normal ejection fraction. In this context, the role of diastolic dysfunction is likely to have played a role in producing symptomatic heart failure. Also, as mentioned in the results, this patient was diagnosed with hypertrophy and a general lack of contractile abilities in the entire myocardium. In relation to this diastolic dysfunction/hypertrophy that was seen, the AHA/ACCF task force does report that in patients with clinical HF, the estimated prevalence of preserved EF is approximately 50% (range of 40–71%) [1]. Current literature also suggests that a high magnitude of hypertrophy or abnormal increases in myocardial stiffness due to collagen restructuring could be the cause of cardiomyopathy [44, 45]. Future efforts will closely examine the cause of cardiomyopathy as well as the relationship between the metrics. The difference in MPZS distribution between a DCM patient and normal subject is illustrated which reinforces our goal to visually identify heterogeneous injury in DCM in the clinical setting. It can be seen from inter-patient similarities that the predominant sentinel region of injury (region of heterogeneity) is the basal-to-mid-ventricular septum.

This study in particular shows that high resolution, detailed 3D strain maps can be generated with DENSE motion tracking and meshfree RPIM numerical analysis and modeling [5, 7, 9, 10, 15]. As evidenced in literature, MRI DENSE can accurately characterize regional LV functionality and have numerous advantages over modalities such as echocardiography [6, 7, 10, 14, 46, 47]. We also mentioned in Materials and Methods that the DENSE-RPIM (displacement-strain) analysis is essentially a model-based technique involving 4D spatio-temporal motion tracking and subsequent strain analysis with RPIM; a technique applicable for large deformation analysis in an arbitrary nonlinear material [35–37]. Traditional FEA requires mapping of field variables between elements and meshes and computationally expensive node generations for shape functions in a pre-defined element. In contrast, meshfree RPIM requires node generation for directly solving the local discretized system of equations. One of the disadvantages in traditional FEA is the higher continuity requirement on the shape functions, which can limit their usage. In comparison, meshfree methods can easily be constructed to have any desired order of continuity. Additionally, there is no requirement for a-priori information on the relationship between nodes which enables more accurate intra and inter-subject comparisons [14, 20, 35–37]. Hence, improving the speed and efficiency of 3D strain parameter computations for combining them into point-wise, regional and global composite indices. Finally, in regards to adapting a meshfree method, it was shown that RPIM strains computed for MPZS are indeed comparable to traditional FEA (MEA) techniques for strain analysis.

The first limitation of this study was not comparing the DENSE based MPZS to that computed from a more established sequence such as tagged-MRI. In past studies we have used the Bland-Altman methodology for assessing agreement between methods [48]. Although, we have conducted direct validations between DENSE and tagged-MRI strains (not MPZS) in previous studies [7, 31]. A second limitation was processing time for left-ventricular segmentation. Despite automated procedures, some manual intervention is still required for accurate boundary detection and reconstructions of LV geometry [17, 49]. A third limitation was the operator selected end-systole timeframes for generating z-scores and not identifying it by peak strains as done in echocardiography studies [50]. The nine years plus age difference between DCM patients and healthy subjects can be considered a fourth limitation. However, previous echocardiography based analysis show that no significant errors occur when this range of age-related differences exist between patients and healthy volunteers during strain normalization [38, 51, 52].

The current study shows how the fast and automated DENSE-RPIM-MPZS paradigm can be used for uniquely indexing sentinel ventricular injury. Additionally, the MPZS metric was shown to correlate well with an important cardiovascular marker, the EF. We also demonstrated how heterogeneous distribution of LV regional dysfunction can be illustrated with 3D surface rendering of MPZS. With extensive validations, the MPZS metric can become an automated, computationally inexpensive and visual tool that helps the clinician diagnose the severity of DCM.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Center for Clinical Imaging Research at the Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology, School of Medicine, Washington University in St. Louis. We also thank Heidi Craddock, RN and Susan Joseph, MD for their valuable insight and their help with patient recruitment. Grant sources include NIH R01 grant HL112804 and The BJH Foundation at Washington University School of Medicine, St Louis, Missouri.

References

- 1.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE, Jr, Drazner MH, Fonarow GC, Geraci SA, Horwich T, Januzzi JL, Johnson MR, Kasper EK, Levy WC, Masoudi FA, McBride PE, McMurray JJ, Mitchell JE, Peterson PN, Riegel B, Sam F, Stevenson LW, Tang WH, Tsai EJ, Wilkoff BL. F. American College of Cardiology, G. American Heart Association Task Force on Practice, 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:e147–e239. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richardson P, McKenna W, Bristow M, Maisch B, Mautner B, O'Connell J, Olsen E, Thiene G, Goodwin J, Gyarfas I, Martin I, Nordet P. Report of the 1995 World Health Organization/International Society and Federation of Cardiology Task Force on the Definition and Classification of cardiomyopathies. Circulation. 1996;93:841–842. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.5.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manolio TA, Baughman KL, Rodeheffer R, Pearson TA, Bristow JD, Michels VV, Abelmann WH, Harlan WR. Prevalence and etiology of idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy (summary of a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute workshop. Am J Cardiol. 1992;69:1458–1466. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(92)90901-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hazebroek M, Dennert R, Heymans S. Idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy: possible triggers and treatment strategies. Netherlands heart journal : monthly journal of the Netherlands Society of Cardiology and the Netherlands Heart Foundation. 2012;20:332–335. doi: 10.1007/s12471-012-0285-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joseph S, Moazami N, Cupps BP, Howells A, Craddock H, Ewald G, Rogers J, Pasque MK. Magnetic resonance imaging-based multiparametric systolic strain analysis and regional contractile heterogeneity in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. The Journal of heart and lung transplantation : the official publication of the International Society for Heart Transplantation. 2009;28:388–394. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2008.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Young AA, Dokos S, Powell KA, Sturm B, McCulloch AD, Starling RC, McCarthy PM, White RD. Regional heterogeneity of function in nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Cardiovascular research. 2001;49:308–318. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00248-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kar J, Knutsen AK, Cupps BP, Zhong X, Pasque MK. Three-dimensional regional strain computation method with displacement encoding with stimulated echoes (DENSE) in non-ischemic, non-valvular dilated cardiomyopathy patients and healthy subjects validated by tagged MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2015;41:386–396. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim D, Gilson WD, Kramer CM, Epstein FH. Myocardial tissue tracking with two-dimensional cine displacement-encoded MR imaging: development and initial evaluation. Radiology. 2004;230:862–871. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2303021213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spottiswoode BS, Zhong X, Hess AT, Kramer CM, Meintjes EM, Mayosi BM, Epstein FH. Tracking myocardial motion from cine DENSE images using spatiotemporal phase unwrapping and temporal fitting. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2007;26:15–30. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2006.884215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhong X, Spottiswoode BS, Meyer CH, Kramer CM, Epstein FH. Imaging three-dimensional myocardial mechanics using navigator-gated volumetric spiral cine DENSE MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2010;64:1089–1097. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Osman NF, Prince JL. Regenerating MR tagged images using harmonic phase (HARP) methods. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2004;51:1428–1433. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2004.827932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhong X, Gibberman LB, Spottiswoode BS, Gilliam AD, Meyer CH, French BA, Epstein FH. Comprehensive cardiovascular magnetic resonance of myocardial mechanics in mice using three-dimensional cine DENSE. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2011;13:83. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-13-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sampath S, Derbyshire JA, Atalar E, Osman NF, Prince JL. Real-time imaging of two-dimensional cardiac strain using a harmonic phase magnetic resonance imaging (HARP-MRI) pulse sequence. Magn Reson Med. 2003;50:154–163. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cupps BP, Bree DR, Wollmuth JR, Howells AC, Voeller RK, Rogers JG, Pasque MK. Myocardial viability mapping by magnetic resonance-based multiparametric systolic strain analysis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86:1546–1553. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.06.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moulton MJ, Creswell LL, Downing SW, Actis RL, Szabo BA, Pasque MK. Myocardial material property determination in the in vivo heart using magnetic resonance imaging. International journal of cardiac imaging. 1996;12:153–167. doi: 10.1007/BF01806218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moulton MJ, Creswell LL, Downing SW, Actis RL, Szabo BA, Vannier MW, Pasque MK. Spline surface interpolation for calculating 3-D ventricular strains from MRI tissue tagging. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:H281–H297. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.270.1.H281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van der Geest RJ, Lelieveldt BP, Angelie E, Danilouchkine M, Swingen C, Sonka M, Reiber JH. Evaluation of a new method for automated detection of left ventricular boundaries in time series of magnetic resonance images using an Active Appearance Motion Model. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2004;6:609–617. doi: 10.1081/jcmr-120038082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van der Geest RJ, Reiber JH. Quantification in cardiac MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1999;10:602–608. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2586(199911)10:5<602::aid-jmri3>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brady BD, Knutsen AK, Ma N, Gardner R, Taggar AK, Cupps BP, Kouchoukos NT, Pasque MK. MRI-based multiparametric strain analysis predicts contractile recovery after aortic valve replacement for aortic insufficiency. J Card Surg. 2012;27:415–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8191.2012.01477.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cupps BP, Taggar AK, Reynolds LM, Lawton JS, Pasque MK. Regional myocardial contractile function: multiparametric strain mapping. Interactive cardiovascular and thoracic surgery. 2010;10:953–957. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2009.220384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maniar HS, Brady BD, Lee U, Cupps BP, Kar J, Wallace KM, Pasque MK. Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction is not Sensitive Enough to Accurately Determine Timing of Surgical Referral for Asymptomatic Patients with Chronic Mitral Regurgitation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;148 doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.05.088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Costello-Boerrigter LC, Boerrigter G, Redfield MM, Rodeheffer RJ, Urban LH, Mahoney DW, Jacobsen SJ, Heublein DM, Burnett JC., Jr Amino-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide and B-type natriuretic peptide in the general community: determinants and detection of left ventricular dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:345–353. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Lemos JA, McGuire DK, Khera A, Das SR, Murphy SA, Omland T, Drazner MH. Screening the population for left ventricular hypertrophy and left ventricular systolic dysfunction using natriuretic peptides: results from the Dallas Heart Study. Am Heart J. 2009;157:746–753. e742. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dao Q, Krishnaswamy P, Kazanegra R, Harrison A, Amirnovin R, Lenert L, Clopton P, Alberto J, Hlavin P, Maisel AS. Utility of B-type natriuretic peptide in the diagnosis of congestive heart failure in an urgent-care setting. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:379–385. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)01156-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fonarow GC, Adams KF, Jr, Abraham WT, Yancy CW, Boscardin WJ. S.G. Adhere Scientific Advisory Committee, Investigators, Risk stratification for in-hospital mortality in acutely decompensated heart failure: classification and regression tree analysis. Jama. 2005;293:572–580. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.5.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levy WC, Mozaffarian D, Linker DT, Sutradhar SC, Anker SD, Cropp AB, Anand I, Maggioni A, Burton P, Sullivan MD, Pitt B, Poole-Wilson PA, Mann DL, Packer M. The Seattle Heart Failure Model: prediction of survival in heart failure. Circulation. 2006;113:1424–1433. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.584102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peterson PN, Rumsfeld JS, Liang L, Albert NM, Hernandez AF, Peterson ED, Fonarow GC, Masoudi FA. P. American Heart Association Get With the Guidelines-Heart Failure, A validated risk score for in-hospital mortality in patients with heart failure from the American Heart Association get with the guidelines program. Circulation. Cardiovascular quality and outcomes. 2010;3:25–32. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.854877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pocock SJ, Wang D, Pfeffer MA, Yusuf S, McMurray JJ, Swedberg KB, Ostergren J, Michelson EL, Pieper KS, Granger CB. Predictors of mortality and morbidity in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:65–75. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Babushka I, Guo BQ. The h, p and h-p version of the finite element method; basis theory and applications. Adv. Eng. Softw. 1992;15:159–174. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moustakidis P, Cupps BP, Pomerantz BJ, Scheri RP, Maniar HS, Kates AM, Gropler RJ, Pasque MK, Sundt TM. Noninvasive, quantitative assessment of left ventricular function in ischemic cardiomyopathy. J Surg Res. 2004;116:187–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2003.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kar J, Knutsen AK, Cupps BP, Pasque MK. A validation of two-dimensional in vivo regional strain computed from displacement encoding with stimulated echoes (DENSE), in reference to tagged magnetic resonance imaging and studies in repeatability. Ann Biomed Eng. 2014;42:541–554. doi: 10.1007/s10439-013-0931-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spottiswoode BS, Zhong X, Lorenz CH, Mayosi BM, Meintjes EM, Epstein FH. Motion-guided segmentation for cine DENSE MRI. Med Image Anal. 2009;13:105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2008.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cerqueira MD, Weissman NJ, Dilsizian V, Jacobs AK, Kaul S, Laskey WK, Pennell DJ, Rumberger JA, Ryan T, Verani MS. S. American Heart Association Writing Group on Myocardial, I. Registration for Cardiac, Standardized myocardial segmentation and nomenclature for tomographic imaging of the heart. A statement for healthcare professionals from the Cardiac Imaging Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology of the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2002;105:539–542. doi: 10.1161/hc0402.102975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.F. American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task, E. American Society of, A. American Heart, C. American Society of Nuclear, A. Heart Failure Society of, S. Heart Rhythm, A. Society for Cardiovascular, Interventions, M. Society of Critical Care, T. Society of Cardiovascular Computed, R. Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic. Douglas PS, Garcia MJ, Haines DE, Lai WW, Manning WJ, Patel AR, Picard MH, Polk DM, Ragosta M, Ward RP, Weiner RB. ACCF/ASE/AHA/ASNC/HFSA/HRS/SCAI/SCCM/SCCT/SCMR 2011 Appropriate Use Criteria for Echocardiography. A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, American Society of Echocardiography, American Heart Association, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Failure Society of America, Heart Rhythm Society, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Critical Care Medicine, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, and Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Endorsed by the American College of Chest Physicians. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:1126–1166. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu GR. Meshfree Methods: Moving Beyond the Finite Element Method. 2. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang JG, Liu GR. A point interpolation meshless method based on radial basis functions. Int J Numer Methods Eng. 2002;54:1623–1648. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang JG, Liu GR. On the optimal shape parameters of radial basis functions used for 2-D meshlesss methods. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng. 2002;191:2611–2630. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Young AA, Axel L. Three-dimensional motion and deformation of the heart wall: estimation with spatial modulation of magnetization--a model-based approach. Radiology. 1992;185:241–247. doi: 10.1148/radiology.185.1.1523316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Young AA, Kramer CM, Ferrari VA, Axel L, Reichek N. Three-dimensional left ventricular deformation in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1994;90:854–867. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.2.854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pourhoseingholi MA, Baghestani AR, Vahedi M. How to control confounding effects by statistical analysis. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2012;5:79–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buring JE. Epidemiology in Medicine. reprint. New York: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bovendeerd PH, Kroon W, Delhaas T. Determinants of left ventricular shear strain. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297:H1058–H1068. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01334.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rezai MR, Balakrishnan Nair S, Cowan B, Young A, Sattar N, Finn JD, Wu FC, Cruickshank JK. Low vitamin D levels are related to left ventricular concentric remodelling in men of different ethnic groups with varying cardiovascular risk. Int J Cardiol. 2012;158:444–447. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.04.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Little WC. Heart failure with a normal left ventricular ejection fraction: diastolic heart failure. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2008;119:93–99. discussion 99-102. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lorell BH, Carabello BA. Left ventricular hypertrophy: pathogenesis, detection, and prognosis. Circulation. 2000;102:470–479. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.4.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Osman NF, Kerwin WS, McVeigh ER, Prince JL. Cardiac motion tracking using CINE harmonic phase (HARP) magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1999;42:1048–1060. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(199912)42:6<1048::aid-mrm9>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Pellikka PA, Picard MH, Roman MJ, Seward J, Shanewise JS, Solomon SD, Spencer KT, Sutton MS, Stewart WJ. G. Chamber Quantification Writing, G. American Society of Echocardiography's, C. Standards, E. European Association of, Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography's Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18:1440–1463. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1:307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Angelie E, de Koning PJ, Danilouchkine MG, van Assen HC, Koning G, van der Geest RJ, Reiber JH. Optimizing the automatic segmentation of the left ventricle in magnetic resonance images. Med Phys. 2005;32:369–375. doi: 10.1118/1.1842912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ingul CB, Stoylen A, Slordahl SA, Wiseth R, Burgess M, Marwick TH. Automated analysis of myocardial deformation at dobutamine stress echocardiography: an angiographic validation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:1651–1659. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kaku K, Takeuchi M, Tsang W, Takigiku K, Yasukochi S, Patel AR, Mor-Avi V, Lang RM, Otsuji Y. Age-related normal range of left ventricular strain and torsion using three-dimensional speckle-tracking echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2014;27:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pan L, Stuber M, Kraitchman DL, Fritzges DL, Gilson WD, Osman NF. Real-time imaging of regional myocardial function using fast-SENC. Magn Reson Med. 2006;55:386–395. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.