Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is an age-related, neurodegenerative disorder characterized by cognitive impairment with memory loss, extracellular amyloid beta (Aβ) peptides aggregation, and intracellular hyper-phosphorylated tau neurofibrillary tangles (NFT) accumulation. Although the 5-lipoxygenase (5LO) protein enzyme is well known as an important modulators of oxidation and inflammation, recent work has highlighted the potential role that this pathway may play a direct role in AD pathogenesis. In this review article, we will discuss how the 5LO via the γ-secretase influences Aβ peptides formation, and other molecular pathologies including neuroinflammation, synaptic integrity, and cognitive functions, and provide an assessment of how targeting this protein could lead to novel therapeutics for AD and other related neurodegenerative disorders.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, 5-lipoxygenase, amyloid beta, γ-secretase, γ-secretase activating protein

Alzheimer’s disease: the neuropathology

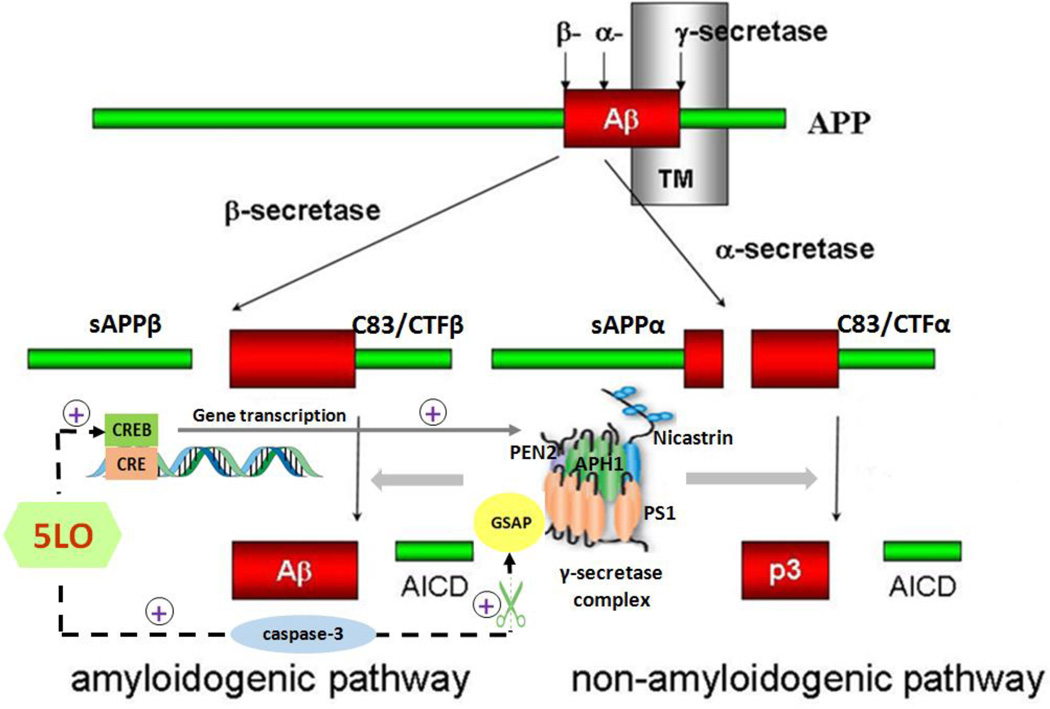

Through extensive clinical and molecular work over the past several decades, the biochemical pathways that lead to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathology have been well characterized. The cardinal pathologies observed in AD are the extracellular deposits of amyloid-β protein (Aβ) known as Aβ plaques, and intracellular accumulations of the hyper-phosphorylated microtubule-associated tau protein known as neurofibrillary tangles [1, 2]. Current dogma presumes Aβ as the upstream molecular initiator in AD based on the evidence that mutations in the Aβ precursor protein (APP) and presenilins, main components of the protease complex that cleaves it to produce Aβ peptides, are found in early-onset, familial variants of AD. Additionally, patients with Down’s syndrome, in which there is an additional chromosome 21, the locus of the APP gene, have significantly increased rates of AD when compared with the general population [3]. However, some recent clinical data have also found mutations in the APP gene that are protective and reduce the risk to develop the disease [4]. The Aβ peptides are formed by the sequential cleavage of APP by the β-secretase (β APP cleavage enzyme, BACE 1) and the γ-secretase complex (composed of the nicastrin, presenilin (PS1), anterior-pharynx defective-1 protein (APH-1), and presenilin enhancer protein (PEN2 or Pen-2), as shown in Figure 1. While APP may be cleaved by α-secretase and then γ-secretase to produce non-amyloidogenic products, this Aβ producing pathway is thought to be privileged in AD. Generation of higher amounts and subsequent aggregation of Aβ peptides through the sequential β- and γ-secretase cleavages is thought to lead to soluble oligomers, followed by longer fibrils, and finally insoluble plaques, which are found abundantly in the vast majority of AD patients on autopsy. Although insoluble plaques have been found in the brains of patients without AD, current thinking is that Aβ oligomers perpetuate the brunt of molecular insults in AD rather than insoluble plaques [5].

Figure 1. APP metabolism in Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

Amyloid β precursor protein (APP) is synthesized in the endoplasmic reticulum and transported to the cell surface through endosomes via the trans-Golgi network. At the cell membranc, APP may undergo either non-amyloidogenic or amyloidgenic processing. APP is cleaved by β-, and then γ-secretase (compose of presenilin1 [PS1], Nicastrin, anterior pharynx defective-1 protein [APH1], and presenilin enhancer 2 [PEN2]) and produced Aβ through amyloidogenic pathway. Aβ peptides form oligomers and eventually accumulated into Aβ plaques.

The 5-lipoxygenase pathway

The 5-lipoxygenase (5LO) is an enzyme that inserts molecular oxygen into the carbon in position 5 of free or esterified fatty acids, most notably arachidonic acid. However, in order to carry out the reaction, 5LO also requires the action of the 5LO activating protein, FLAP, which presents the substrate for the enzymatic oxygenation [6].

Immediate products of 5LO include unstable 5-hydroperoxyeicosatetraenoic acid which is either reduced to 5-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid or leukotriene A4 (LTA4). Depending on the cellular milieu, LTA4 can be metabolized either to leukotriene B4 (LTB4) or C4 (LTC4), with LTC4 further being metabolized to LTD4 and LTE4 [7], as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. The 5-lipoxygenase pathway.

The 5-lipoxygenase protein (5LO) inserts molecular oxygen into free and esterified fatty acids with the aid of 5-lipoxygenase activating protein (FLAP). 5LO acts on arachidonic acid to produce 5-HPETE, which is metabolized into 5-HETE or leukotriene A4. Leukotriene A4 is then either acted on by LTA4 hydrolase to produce LTB4 or by LTC4 synthase to produce LTC4. Leukotriene B4 may then act on leukotriene B4 receptors (BLT1, BLT2) which are G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) to initiate second messenger systems. Leukotriene C4 may be acted on by γ-glutamyltransferase 1 to produce LTD4, which may be acted on by LTD4 dipeptidase to yield LTE4. Collectively LTC4, LTD4, and LTE4 are known as the cysteinyl leukotriene. These cysteinyl leukotrienes all may act on cysteinyl leukotriene receptors (CysLT1, CysLT2) which are also GPCRs to exert downstream effects.

These 5LO final products have potent biological actions mediated by binding to their respective G protein-coupled receptors, such as BLT1 and BLT2 for LTB4 [8–10], and CysLT1 and CysLT2 for LTC4 and LTD4 [11, 12]. LTB4 is a key mediator of inflammatory processes, immune responses, and host defense against infection [13, 14] and is known to stimulate chemotaxis, degranulation, release of lysosomal enzymes, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation [15, 16].

5-lipoxygenase pathway in brain aging and Alzheimer’s disease

5LO is found throughout the central nervous system, in both neuron and glia cells [17]. However, its expression levels are highest in the cortex and hippocampus areas, two regions that are particularly vulnerable to neurodegenerative insults [18, 19].

Interestingly, it has been shown by different groups that in the brain 5LO and its metabolites manifest an age-dependent increase [20, 21]. Since aging is one of the strongest risk factors for developing AD [17], initially it was proposed that this pathway could potentially be involved in brain aging and events germaine to the pathogenesis of AD [22]. Post-mortem studies have shown that compared with healthy controls, post-mortem AD brains had higher 5LO protein levels in cortex and hippocampus. By contrast, no significant differences were detected between the two groups when the cerebellum, an area typically devoid of AD pathology, was assayed [23, 24].

A small pilot study in humans has linked 5LO gene polymorphisms to early- and late-onset AD, although large-scale population studies are yet to confirm these findings [25].

Another study investigated the epigenetic regulation of 5LO in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of subjects with late-onset AD and age-matched controls showed a significant increase in 5LO gene expression in AD subjects compared to healthy controls, which paralleled with increased 5LO protein and leukotriene B4 levels.

Recently, it was reported that CysLT1 receptor is involved in Aβ1–42-induced neurotoxicity, and that its pharmacological blockade by a receptor antagonist could ameliorate Aβ1–42 induced impairments of cognitive function and hippocampal LTP [26–28].

5-lipoxygenase as a modulator of Aβ formation: in vivo and in vitro evidence

Taken together the data presented above supported for the first time the novel hypothesis that 5LO could play a functional role in neurodegeneration and AD pathogenesis in particular.

To address this question we utilized Tg2576 mice, a transgenic mouse model that expresses the K670N/M671L APP mutation found in a Swedish family with early-onset AD, which develop age-dependent brain amyloidosis. We crossed the Tg2576 with mice genetically deficient for 5LO (i.e., homozygous knockout of 5LO) and compared them with regular Tg2576 animals to see how brain amyloidosis was affected when 5LO was not genetically available. We found that both soluble and insoluble Aβ peptides were significantly reduced in the brains of Tg2576 animals lacking 5LO, and that this reduction was even more apparent as the animals aged from middle- to late-life. On immunohistochemical analyses, this reduction in Aβ peptides translated to fewer amyloid β plaques and reduced total amyloid burden [23]. What was singular about this initial work was that Aβ reduction caused by 5LO knockout did not seem to change steady state levels of APP or increase several proteins thought to participate in Aβ clearance in the brain.

Genetic and pharmacological methods were used next to further support the concept that 5LO may act as an endogenous modulator of Aβ formation in vivo and in vitro. In N2A (neuro-2 A neuroblastoma) cells stably expressing Swedish mutant of human APP (APP swe), over-expression of 5LO results in an elevation of Aβ formation, which associates with increased protein levels of the four components of the γ-secretase complex PS1, nicastrin, APH-1, and Pen-2 [29]. The regulation of 5LO on Aβ formation was induced by the activation of the cAMP-response element binding protein (CREB), which in turn increased transcription of the four components of the γ-secretase complex. Neuronal cells exposed to the main 5LO metabolic product, 5-HETE, produced more Aβ, had and elevation of the γ-secretase complex, and CREB levels and activity. The effect was prevented by blocking CREB activation via a pharmacologic inhibition or dominant negative mutants [29].

In vivo experiments confirmed these observations. An adeno-associated viral (AAV)-mediated 5LO gene transfer in the brain of Tg2576 resulted in 5LO over-expression and a significant increase in the amount of Aβ formed and deposited in their brains. Biochemical analysis in the brains of these animals showed a significant increase in the levels of the transcription factor CREB, and a significant elevation of the mRNA and protein levels of the γ-secretase complex [30].

5LO and the γ-secretase complex

The inhibition of γ-secretase in AD has been, and continues to be a highly desirable mode of reducing Aβ production. However, full blockade of γ-secretase has deleterious effect because this enzyme is also an active player in the proteolytic processing of other substrates besides APP such as Notch-1 and cadherins, both of which are important in transducing biologically relevant intracellular signals.

Supporting this concept, during a recent trial testing the γ-secretase inhibitor semagacestat (LY 450139), AD patients actually experienced a functional decline compared to patients who took a placebo in addition to several other significant adverse effects [16]. Thus, development of compounds able to selectively inhibit Aβ production without affecting the cleavage of other substrates is the most desirable approach for AD therapy to minimize the toxic effects. Therefore, to see if Notch was also affected in our system, we assayed whether its signaling pathway was altered in both our cellular and animal models. To our surprise, we found that 5LO-dependent modulation of γ-secretase is completely independent of Notch processing. While at the present time it is not known why a reduction in steady-state levels of γ-secretase induced by knockout or inhibition of 5LO reduces amyloid levels without altering Notch, our findings are in line with the novel concept of “modulatory action” of 5LO towards this secretase. Thus, recently a new class of drug has emerged as modulators and not direct inhibitors of the γ-secretase which would reduce Aβ formation without interfering with the processing of other biologically important substrates such as Notch [20]. We speculate that 5LO activation may somehow alter membrane dynamics allowing greater access to APP than Notch processing, although this area 5LO neurobiology biology remains completely unexplored.

This fact makes any potential therapeutic application of 5LO inhibitors, which could act as γ-secretase modulators, in AD-like amyloidosis, as a feasible one without the potential toxicity of the classical inhibitors of the complex. Since newer generations of γ-secretase inhibitors are being screened specifically for Notch-sparing properties, this discovery places further importance on pharmacologic targeting of 5LO in AD.

5-lipoxygenase modulation of the AD-like phenotype

Abeta and tau

So far we have provided evidence in support for a specific role of 5LO on Aβ production via the modulation of the γ-secretase complex without any significant effect on the Notch processing. However, the AD models used so far are characterized mainly by over-production and accumulation of Aβ peptides which mimick more an AD-like amyloidosis. Considering that besides Aβ, tau neuropathology is the second most important feature of AD, they ultimately represent a limited version of the disease phenotype.

With this in mind we set up a series of pre-clinical studies implementing a transgenic mouse model which develop all 3 characteristics of the AD phenotype: Aβ deposition, tau hyper-phosphorylation, and memory impairments, the triple transgenic mouse (3xTg).

Initially, we over-express 5LO by employing an AAV vector system in the brains of 3xTg mice. The results showed that compared with controls, 3xTg mice over-expressing 5LO manifested an exacerbation of memory deficits, Aβ plaques and tau tangles pathologies. The elevation in Aβ was secondary to an up-regulation of γ-secretase pathway, whereas tau hyperphosphorylation resulted from an activation of the Cdk5 kinase pathway. In vitro study confirmed the involvement of this kinase in the 5LO-dependent tau phosphorylation, which was independent of the effect on Aβ [31].

Next we used a pharmacologic approach in which we administered a specific and selective 5LO inhibitor, zileuton, to 3xTg mice, and a genetic approach by generating 3xTg mice deficient for 5LO (3xTg-5LOKO). Compared with controls, we found that even before the development of overt neuropathology, 3xTg-5LOKO mice and 3xTg mice receiving zileuton manifested a significant improvement in cognition and memory, which was associated with a rescue of their synaptic dysfunctions and amelioration of synaptic integrity. In addition, later in life these mice had a significant reduction of their Aβ and tau pathology.

Taken together, these data establish the 5LO as a pleiotropic contributor to the development of the full spectrum of the AD phenotype, making it a viable therapeutic target for the treatment of AD [29, 32, 33].

Neuroinflammation

Altered inflammatory reactions are strongly associated with AD pathology and cognitive dysfunction. The dysregulation of inflammatory cytokines as well as immune cells (i.e., microglia and astrocytes) activation in AD brains has been well-documented [34–36]. Disruption of the 5LO pathway, either genetically or pharmacologically, reduces not only microglia, but also astrocytosis in the brains of AD transgenic mice [27, 30, 34], which associated with a reduction in pro-inflammatory cytokine levels. An argument can be made that reduction in Aβ and tau pathology caused by 5LO inhibition independently predisposes AD transgenic animals to have reduced neuroinflammation at baseline. While this may be true to some extent, chronic lipopolysaccharide administration in AD animals lacking 5LO increases tau phosphorylation despite the fact that no γ-secretase elevation was observed, Aβ was reduced, microgliosis and astrocytosis, or brain levels of inflammatory cytokines were reduced to baseline [37]. These data suggest that the contribution of 5LO to the neuroinflammation does not depend exclusively on Aβ or tau.

5LO and AD synaptic function and memory impairment

Data from transgenic mouse models of the disease as well as brains of AD patients have strongly suggested that the Aβ and tau neuropathologies compromise synaptic function, with such impairment occurring well before symptoms of the disease manifest [22]. This dysfunction is characterized by alteration in markers of presynaptic integrity, such as synaptophysin, as well as markers of post-synaptic integrity, such as post-synaptic density protein 95 (PSD-95), eventually leading to impairments in long-term potentiation (LTP), which is considered a marker of synaptic function. Presumably, if 5LO modulates Aβ and tau pathology, it would also alter synaptic integrity and LTP in AD animals. To see if this was the case, we continued our investigation of 5LO in the same AD animal models, focusing on these important aspects of the neurobiology of AD.

First, we observed that overexpression of 5LO resulted in reduced synaptophysin and PSD-95, while inhibition and knockout of 5LO increased levels of these proteins in the brains of Tg2576 as well as 3xTg mice. To investigate whether this had functional relevance, we utilized an electrophysiological approach to see whether 5LO affected hippocampal LTP. While we confirmed previous reports showing that 3xTg animals have significant impairment in LTP when compared to wild-type control mice, next we showed that genetic absence of 5LO or its pharmacological blockade were both able to rescue this dysfunction, restoring LTP to the same levels of the wild-type mice [22].

However, for a molecular target to be useful in AD, it must rescue behavioral as well as biochemical insults. In humans, AD memory impairments typically declare themselves initially as disruption of episodic memory and consolidation of new memories, eventually progressing to global cognitive decline. Methods to assess analogous domains in rodent models are numerous, but to assess whether 5LO rescued the altered behavioral phenotype in AD mouse models, we selected the Y-maze exploratory behavior, and 24-hour fear-conditioned memory recall. Aberration in Y-maze exploratory behavior represents impairment in short-term working memory while fear-conditioned memory impairment assesses hippocampal-dependent and hippocampal-independent memory building processes. In line with our data on synaptic integrity and LTP, 5LO inhibition and knockout restored learning and memory impairments in the transgenic mice as assessed by these paradigms to a level indistinguishable from their wild-type controls [10, 12, 22].

Interestingly, a recent paper showed that a 6-week treatment of young (4 months) and old (20 months) rats with montelukast, a marketed anti-asthmatic drug antagonizing leukotriene receptors, reduces neuroinflammation, elevates hippocampal neurogenesis and improves learning and memory in old animals. By using gene knockdown and knockout approaches, the authors demonstrate that the effect is mediated through inhibition of the leukotriene receptor GPR17. This work illustrates that inhibition of 5LO pathway signaling might represent a safe and druggable target to restore cognitive functions in old individuals and paves the way for future clinical translation opportunities of inhibitor of this pathway for the treatment of dementias [38].

5LO and GSAP

The recent discovery of a γ-secretase activating protein (GSAP) which interacts with γ-secretase complex to facilitate Aβ formation without affecting Notch has established it as a new relevant target for a viable and safer in vivo anti-Aβ therapy [39, 40]. GSAP is increased in post-mortem brain tissues of AD patients, and its pharmacological or genetic inhibition results in an amelioration of the AD-like amyloidotic phenotype in transgenic mouse models of the disease [41, 42]. The active form of GSAP is a 16kDa protein deriving from a C-terminal fragment of a larger precursor protein of 110kDa via a caspase-3 mediated cleavage [43]. Recent experimental evidence suggested for the first time that 5LO besides acting as a modulator of Aβ formation by regulating the transcription of the γ-secretase complex, it also behaves as an endogenous regulator of levels and availability of the GSAP 16kDa. In particular it was demonstrated that 5LO by activating caspase 3 regulates the proteolytic processing of precursor form of GSAP (110kDa) with the final formation of its active fragment (Figure 3). These results were confirmed in vivo by using transgenic mouse models of AD in which 5LO level and activity were modulated genetically or pharmacologically [44].

Figure 3. Interaction between APP metabolism and the 5Lipoxygenase (5LO).

The regulation of 5LO on the formation of Aβ was induced by activating the cAMP-response element binding protein (CREB), which in turn increases transcription of the four components of the γ-secretase complex. 5LO was also reported recently as an endogenous regulator for the proteolytic formation of γ-secretase activating protein (GSAP) by directly and specifically activating caspase-3.

Implications of lipoxygenases as therapeutic targets for Alzheimer’s disease

AD is an irreversible age-associated neurodegenerative condition characterized by progressive memory loss and cognitive decline. In its most common form, sporadic AD risk is considered to stem from interactions between multiple environmental risk factors and different genetic vulnerabilities making intervention rather challenging. As result, recent research in AD has shifted towards prevention and away from symptomatic treatment, leaving at least five million AD patients in the US and 30 million worldwide with little hope for new, effective drugs.

We have discovered that the 5LO pathway plays a crucial role in the development of the full pathologic phenotype of AD which includes aberrant Aβ production and deposition, altered tau phosphorylation, synaptic pathology and dysfunction, and ultimately behavioral impairments. Therefore, 5LO-targeted therapeutics have the potential to bridge the current AD treatment gap by being both therapeutic as well as preventative. While further characterization of 5LO inhibition is required before clinical trials are initiated in AD, in general this approach has a favorable, and well characterized, adverse effect profile that may obviate concerns that other AD-directed therapeutics may have.

Based on the knowledge accumulated so far and these considerations, we believe that 5LO inhibitors hold significant promise as attractive disease-modifying agents in AD.

Highlights.

5Lipoxygenase is upregulated in brain aging and Alzheimer’s disease.

5Lipoxygenase acts as an endogenous modulator of Aβ formation in vitro and in vivo.

5Lipoxygenase modulates the four components of the γ-secretase complex at the transcription levels without affecting Notch signaling.

5Lipoxygenase has a pleiotropic effect on the entire spectrum of the Alzheimer’s disease phenotype.

5Lipoxygenase is a viable therapeutic target for Alzheimer’s disease.

Acknowledgments

The work from the author’s lab described in this article was supported in part by grants from the National Institute of Health, the Alzheimer’s Association and the Alzheimer’s Art Quilt Initiative.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Iqbal K, Liu F, Gong CX, Grundke-Iqbal I. Tau in Alzheimer disease and related tauopathies. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2010;7:656–664. doi: 10.2174/156720510793611592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holtzman DM, Morris JC, Goate AM. Alzheimer’s disease: the challenge of the second century. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011;3(77):77sr1. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilcock DM, Griffin WS. Down’s syndrome, neuroinflammation and Alzheimer neuropathogenesis. J. Neuroinflammation. 2013;10:84. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-10-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jonsson T, Atwal JK, Steinberg S, Snaedal J, Jonsson PV. Bjornsson S., A mutation in APP protects against Alzheimer’s disease and age-related cognitive decline. Nature. 2012;488:96–99. doi: 10.1038/nature11283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ono K, Yamada M. Low-n oligomers as therapeutic targets of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurochem. 2011;117:19–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rådmark O, Samuelsson B. Regulation of 5-lipoxygenase, a key enzyme in leukotriene biosynthesis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010;396:105–110. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.02.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bishayee K, Khuda-Bukhsh AR. 5-lipoxygenase antagonist therapy: a new approach towards targeted cancer chemotherapy. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. (Shanghai) 2013;45:709–719. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmt064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yokomizo T, Kato K, Terawaki T, Izumi T, Shimizu T. A second leukotriene B4 receptor, BLT2: a new therapeutic target in inflammation and immulogical disorders. J. Exp. Med. 2001;192:421. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.3.421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yokomizo T, Izumi T, Chang K, Takuwa Y, Shimizu T. A G protein-coupled receptor for leukotriene B4 that mediates chemotaxis. Nature. 1997;387:620. doi: 10.1038/42506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yokomizo T, Kato K, Hagiya H, Izumi T, Shimizu T. Hydroxyeicosanoids bind to and activate the low affinity leukotriene B4 receptor, BLT2. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;276:12454. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011361200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Norel X, Brink C. The quest for new cysteinyl-leukotriene and lipoxin receptors: recent clues. Pharmacol Ther. 2004;103:81–94. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh RK, Gupta S, Dastidar S, Ray A. Cysteinyl lukotrienes and their receptors: molecular and functional characteristics. Pharmacology. 2010;85:336–349. doi: 10.1159/000312669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brock TG, McNish RW, Peters-Golden M. Translocation and leukotriene synthetic capacity of nuclear 5-lipoxygenase in rat basophilic leukemia cells and alveolar macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:21652. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.37.21652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yokomizo T, Izumi T, Shimizu T. Leukotriene B4: metabolism and signal transduction. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2001;385:231. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palmer RM, Stepney RJ, Higgs GA, Eakins KE. Chemokinetic activity of arachidonic and lipoxygenase products on leukocytes of different species. Prostaglandins. 1980;20:411. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(80)80058-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Busse WW. Leukotrienes and inflammation. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care. Med. 1998;157:S210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chu J, Praticò D. The 5-lipoxygenase pathway as a common pathway for pathological brain and vascular aging. Cardiovasc. Psychiatry Neurol. 2009;2009:174657. doi: 10.1155/2009/174657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lammers CH, Schweitzer P, Facchinetti P, Arrang JM, Madamba SG. Siggins G. R., Arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase and its activating protein: prominent hippocampal expression and role in somatostatin signaling. J. Neurochem. 1996;66:147–152. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.66010147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chinnici CM, Yao Y, Pratico D. The 5-lipoxygenase enzymatic pathway in the mouse brain: young versus old. Neurobiol. Aging. 2007;28:1457–1462. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paris D, Town T, Parker TA, Tan J, Humphrey J, Crawford F. Inhibition of Alzheimer’s betaamyloid induced vasoactivity and proinflammatory response in microglia by a cGMP-dependent mechanism. Exp Neurol. 1999;157(1):211–221. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Di Francesco A1, Arosio B, Gussago C, Dainese E, Mari D, D'Addario C, Maccarrone M. Involvement of 5-lipoxygenase in Alzheimer's disease: a role for DNA methylation. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;37(1):3–8. doi: 10.3233/JAD-130506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Praticò D. Oxidative stress hypothesis in Alzheimer's disease: a reappraisal. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2008;29:609–615. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Firuzi O, Zhuo J, Chinnici CM, Wisniewski T, Praticò D. 5-lipoxygenase gene disruption reduces amyloid-beta pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. FASEB J. 2008;22:1169–1178. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-9131.com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ikonomovic MD, Abrahamson EE, Uz T, Manev H, Dekosky ST. Increased 5-lipoxygenase immunoreactivity in the hippocampus of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2008;56:1065–1073. doi: 10.1369/jhc.2008.951855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qu T, Manev R, Manev H. 5-lipoxygenase (5-LOX) promoter polymorphisms in patients with early-onset and late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2001;13:304–305. doi: 10.1176/jnp.13.2.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang SS, Hong H, Chen L, Mei ZL, Ji MJ, Xiang GQ, Li N, Ji H. Involvement of cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 1 in Aβ1–42-induced neurotoxicity in vitro and in vivo. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35(3):590–599. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lai J, Hu M, Wang H, Hu M, Long Y, Miao MX, Li JC, Wang XB, Kong LY, Hong H. Montelukast targeting the cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 1 ameliorates Aβ1–42-induced memory impairment and neuroinflammatory and apoptotic responses in mice. Neuropharmacology. 2014;79:707–714. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tang SS, Ji MJ, Chen L, Hu M, Long Y, Li YQ, Miao MX, Li JC, Li N, Ji H, Chen XJ, Hong H. Protective effect of pranlukast on Aβ1–42-induced cognitive deficits associated with downregulation of cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 1. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;17(4):581–592. doi: 10.1017/S1461145713001314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chu J, Praticò D. 5-lipoxygenase as an endogenous modulator of amyloid beta formation in vivo. Ann. Neurol. 2011;69:34–46. doi: 10.1002/ana.22234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chu J, Giannopoulos PF. Ceballos-Diaz C., Golde T. E., Pratico D., Adeno-associated virus mediated brain delivery of 5-lipoxygenase modulates the AD-like phenotype of APP mice. Mol. Neurodegener. 2012;7:1. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-7-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chu J, Giannopoulos PF, Ceballos-Diaz C, Golde TE, Praticò D. 5-lipoxygenase gene transfer worsens memory, amyloid and tau brain pathologies in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Ann. Neurol. 72(2012):442–454. doi: 10.1002/ana.23642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 32.Chu J, Praticò D. Pharmacological blockade of 5-lipoxygenase improves the amyloidotic phenotype of an Alzheimer’s disease transgenic mouse model involvement of gamma-secretase. Am. J. Pathol. 2011;178:1762–1769. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 33.Giannopoulos PF, Chu J, Joshi YB, Sperow M, Li JG, Kirby LG. Gene knockout of 5-lipoxygenase rescues synaptic dysfunction and improves memory in the triple-transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Psychiatry. 2014;19:511–518. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 34.Morales I, Jiménez JM, Mancilla M, Maccioni RB. Tau oligomers and fibrils induce activation of microglial cells. J. Alzheimer Dis. 2013;37:849–856. doi: 10.3233/JAD-131843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jo WK, Law AC, Chung SK. The neglected co-starin the dementia drama: the putative roles of astrocytes in the pathogenesis of major neurocognitive disorders. Mol. Psychiatry. 2014;19:159–167. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wright AL, Zinn R, Hohensinn B, Konen LM, Beynon SB, Tan RP. Neuroinflammation a neuronal loss precede Abeta plaque deposition in the hAPP-J20 mousemodel of Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e59586. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yash B. Joshi, Phillip F, Giannopoulos Jin Chu, Domenico Praticò. Modulation of LPS-induced memory insult, γ-secretase and neuroinflammation in 3xTg mice by 5-Lipoxygenase. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35(5):1024–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marschallinger J, Schäffner I, Klein B, Gelfert R. Structural and functional rejuvenation of the aged brain by an approved anti-asthmatic drug. Nat Commun. 2015;27(6):8466. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.He G, Luo W, Li P, Remmers C, Netzer WJ, Hendrick J, Bettayeb K, Flajolet M, Gorelick F, Wennogle LP, Greengard P. Gamma-secretase activating protein is a therapeutic target for Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 2010;467(7311):95–98. doi: 10.1038/nature09325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Deatherage CL, Hadziselimovic A, Sanders CR. Purification and characterization of human γ-secretase activating protein. Biochemistry. 2012;51:5153–5159. doi: 10.1021/bi300605u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Satoh J, Tabunoki H, Ishida T, Saito Y, Arima K. Immunohistochemical characterization of γ-secretase activating protein expression in Alzheimer’s disease brain. Neuropathol. App. Neurobiol. 2012;38:132–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2011.01206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chu J, Lauretti E, Craige CP, Praticò D. Pharmacological modulation of GSAP reduces amyloid-β levels and tau phosphorylation in mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease with plaques and tangles. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;41(3):729–737. doi: 10.3233/JAD-140105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chu J, Li JG, Joshi YB, Giannopoulos PF, Hoffman NE, Madesh M, Praticò D. Gamma secretase-activating protein is a substrate for caspase-3: implications for Alzheimer's disease. Biol Psychiatry. 2014;77(8):720–728. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chu J, Li JG, Hoffman NE, Stough AM, Madesh M, Praticò D. Regulation of gamma-secretase activating protein by the 5Lipoxygenase: in vitro and in vivo evidence. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11086. doi: 10.1038/srep11086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]