Abstract

BACKGROUND & AIMS

Delays in diagnostic testing after a positive result from a screening test can undermine the benefits of colorectal cancer (CRC) screening, but there are few empirical data on the effects of such delays. We used microsimulation modeling to estimate the consequences of time to colonoscopy following a positive result from a fecal immunochemical test (FIT).

METHODS

We used an established microsimulation model to simulate an average-risk United States population cohort that underwent annual FIT screening (from ages 50 to 75 years), with follow-up colonoscopy examinations for individuals with positive results (cutoff, 20 μg/g) at different time points in the following 12 months. Main evaluated outcomes were CRC incidence and mortality; additional outcomes were total life-years lost and net costs of screening.

RESULTS

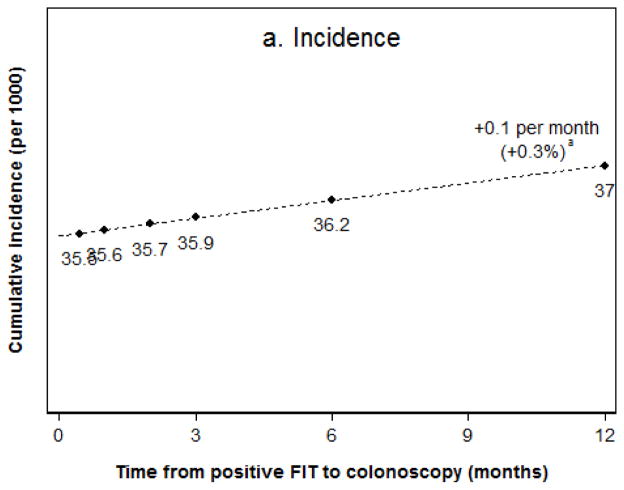

For individuals who underwent diagnostic colonoscopy within 2 weeks of a positive result from a FIT, the estimated lifetime risk of CRC incidence was 35.5/1000 persons and mortality was 7.8/1000 persons. Every month added until colonoscopy was associated with a 0.1/1000 person increase in cancer incidence risk (an increase of 0.3%/month, compared with individuals who received colonoscopies within 2 weeks) and mortality risk (increase of 1.4%/month). Among individuals who received colonoscopy examinations 12 months after a positive result from a FIT, the incidence of CRC was 27.0/1000 persons (increase of 4%, compared with 2 weeks) and mortality was 9.1/1000 persons (increase of 16%). Total years of life gained for the entire screening cohort decreased from an estimated 93.7/1000 persons with an almost immediate follow-up colonoscopy (cost savings of $208 per patient, compared with no colonoscopy), to 84.8/1000 persons with follow-up colonoscopies at 12 months (decrease of 9%; cost savings of $100/patient, compared with no colonoscopy).

CONCLUSION

Using a microsimulation model of an average-risk US screening cohort, we estimated that delays of up to 12 months after a positive result from a FIT can produce proportional losses of up to nearly 10% in overall screening benefits. These findings indicate the importance of timely follow-up colonoscopy examinations of patients with positive results from FITs.

Keywords: Colorectal Neoplasms, Screening and Early Detection, Occult Blood, Time Factors

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer is the second leading cause of cancer deaths in the United States.1 Multiple trials have shown that frequent fecal occult blood testing can reduce the risk of colorectal cancer mortality.2–4 As a two-stage screening strategy, the effectiveness of fecal occult blood testing depends on receiving adequate follow-up testing for positive results, generally with colonoscopy. There are no clear guidelines, however, for the appropriate time interval to follow-up colonoscopy. Some studies suggest that intervals of 6 months or longer are common in actual clinical practice.5, 6 United States national patient safety goals emphasize the importance of prompt clinical evaluation of abnormal laboratory test results, but in the case of fecal colorectal cancer testing, the relationship between the time interval from the date of a positive result to diagnostic colonoscopy and colorectal cancer outcomes is not well known. A recent literature review identified two small studies on the subject,7 the largest of which suggested that longer intervals to receipt of colonoscopy may be associated with higher likelihood of advanced-stage colorectal cancer.8 However, the study was underpowered to detect statistical differences.

To inform patients, policy, and clinical decision-making on colorectal cancer screening, we used a microsimulation model approach to evaluate the effect of different lengths of time from a positive fecal immunochemical test (FIT) result to receipt of colonoscopy on colorectal cancer incidence, stage distribution, mortality, and the cost-effectiveness of screening programs. In sensitivity analyses we also evaluated other fecal colorectal cancer tests.

METHODS

For this study, we simulated an average-risk United States population cohort who received annual FIT screening between ages 50–75 years. The analyses used the Microsimulation Screening Analysis-Colon (MISCAN-Colon) model developed by the Department of Public Health within Erasmus MC University Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands. MISCAN-Colon is part of the United States National Cancer Institute’s (NCI’s) Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network (CISNET).9 It has been used to inform screening recommendations of the United States Preventive Services Task Force.10 The model generates, with random variation, the individual life histories for a large population, similar to the United States population in terms of the life expectancy and cancer risk, to evaluate how screening strategies may alter these life histories. The effectiveness of a screening strategy is modeled through a test’s ability to detect adenomas or preclinical cancer (Supplementary Table 1). The effects of time to diagnostic testing follow from the model’s assumptions on adenoma and cancer progression.

There is good concordance between the modeled effects of screening and trial results for screening with guaiac fecal occult blood tests (gFOBT),2, 4, 11 and colonoscopy surveillance in adenoma patients.12 For FIT screening, the simulated stage distribution of screen-detected cancers and the simulated mortality effects were consistent with data from population-based studies,13–15 supporting the use of this approach for assessing the effect of lag in diagnostic testing after a positive fecal test result.

Further details about the model and its assumptions are included in the Supplementary Material.

Outcomes

Outcomes evaluated were lifetime colorectal cancer incidence, stage and mortality in FIT positive patients for different time intervals to follow-up colonoscopy, as well as the benefits and cost of the FIT screening program as a whole. We also estimated the continuous outcome differences associated with each additional month to colonoscopy using linear regression. Life-years and costs were discounted at the conventional 3% per year.16

Analysis

We simulated 10 million men and women born January 1st, 1960. All patients without diagnosed colorectal cancer participated in and complied with annual FIT screening.17 We considered seven scenarios for the average time from positive FIT (OC Sensor, cutoff level for a positive result is 20 μg/g [100 ng/ml]) to follow-up colonoscopy: 2 weeks, 1 months, 2 months, 3 months, 6 months, 12 months and no follow-up colonoscopy. These lag-times were applied to each simulated patient and at every occurrence of a positive result. Patients with adenomas detected at colonoscopy received surveillance colonoscopy per guidelines after 3 – 5 years, depending on the size and multiplicity of adenomas detected.18

Sensitivity analysis

In the sensitivity analysis, we evaluated two alternative colorectal cancer screening tests, including the gFOBT (Hemoccult II) and the multi-target stool DNA test (Cologuard) (Supplementary Table 1). We further evaluated several alternative model scenarios, including: biennial FIT screening, 50% longer or shorter average duration of the preclinical cancer phase (sojourn time); 5–15 percentage-point lower or higher sensitivity of colonoscopy depending on the lesion size (Supplementary Table 1) (to account for variation in adenoma detection);19 5–15 percentage-point lower or higher sensitivity of FIT (Supplementary Table 1); 50% lower or higher FIT false-positive rates (1-specificity); and randomly distributed rather than deterministic time to diagnostic follow-up (Gamma[μ,1]; μ = 2 weeks or 1/2/3/6/12 months).

Role of the funding source

This study was conducted within the Population-Based Research Optimizing Screening Through Personalized Regimens (PROSPR) consortium, which aims to conduct multisite, coordinated, trans-disciplinary research to evaluate and improve screening and is funded by the NCI. This work is also supported partly by resources from the Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs. The funders played no role for this report.

RESULTS

Colorectal cancer outcomes in FIT positive patients

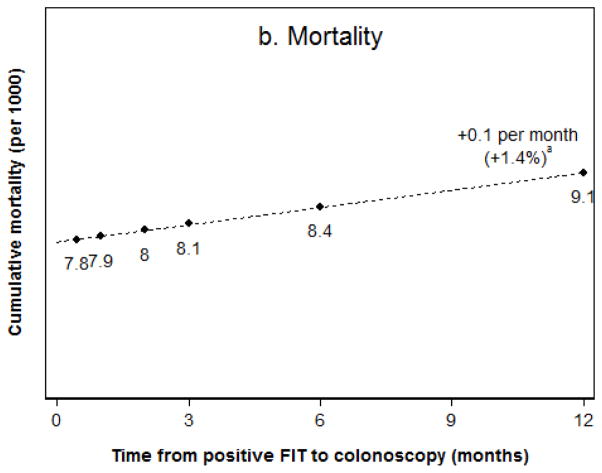

Among FIT screening participants with a positive test result, the lifetime risks of colorectal cancer incidence and mortality without any diagnostic follow-up were estimated as 82.8 and 34.4 per 1000 patients, respectively. Among patients who had diagnostic colonoscopy within two weeks, the risk of colorectal cancer was reduced to 35.5 per 1000 (Figure 1a) and the risk of death from colorectal cancer was reduced to 7.8 per 1000 (Figure 1b). Of the diagnosed cancers, 57% were stage I, 24% stage II, 12% stage III, and 7% stage IV (Figure 2). For every additional month to diagnostic colonoscopy, estimated colorectal cancer incidence was higher by 0.1 per 1000 (or a 0.3% relative difference) compared to diagnostic colonoscopy within two weeks, as was cancer-related mortality (1.4% relative difference). For the scenario of diagnostic follow-up at 12 months from a positive FIT, colorectal cancer incidence was 37.0 per 1000, which was about 1.4 cases per 1000 (4%) higher than for almost immediate follow-up, and cancer-related mortality was higher by 1.3 deaths per 1000 (16%). Diagnosed cancers shifted towards more advanced stages, with 50% diagnosed in stage I, 28% stage II, 14% stage III, and 8% stage IV, which is an absolute 7% lower share of stage I cancers.

Figure 1.

Figure 1a,b. Lifetime colorectal cancer incidence (a) and mortality (b) in FIT positive patients.

aRelative to the scenario of follow-up within two weeks from a positive result.

Figure 2.

Stages of newly diagnosed colorectal cancer cases in FIT positive patients according to time to diagnostic colonoscopy.

Total benefits and cost of FIT screening for the entire screening cohort

Among all FIT screening participants, the lifetime risks of colorectal cancer incidence and mortality without any diagnostic follow-up of positive test results - the equivalent of no screening - were 64.8 and 26.8 per 1000, respectively, and 133.5 years of life were lost per 1000 patients due to colorectal cancer (Table 1). An annual FIT screening program in which diagnostic follow-up of positive tests occurred within two weeks averted 29.2 colorectal cancer cases, 19.4 colorectal cancer deaths and the loss of 93.7 life-years to the disease per 1000 patients. Screening with diagnostic follow-up within 2 weeks of positive results was cost-saving compared to no screening, with a net cost-saving of US $208 per screened patient. With follow-up at 12 months, the number of prevented colorectal cancer cases and deaths decreased to 27.8 and 18.5 per 1000 patients, respectively. Years-of-life saved were 8.9 (9%) lower than with almost immediate follow-up, and at 84.8 per 1000 patients; screening remained cost-saving, but net cost-savings decreased to US $100 per screened patient.

Table 1.

Simulated cost-effectiveness of FIT screening for the entire screening cohort.

| Lifetime outcomes per 1000 patients | Screening

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | Average time from positive FIT to colonoscopy (months)

|

||||||

| 0 (2 weeks) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 12 | ||

| Colorectal cancer outcomes | |||||||

| Cancer cases | 64.8 | 35.5 | 35.6 | 35.7 | 35.9 | 36.2 | 37.0 |

| Advanced cancer cases a | 53.4 | 17.1 | 17.2 | 17.5 | 17.7 | 18.5 | 19.9 |

| Cancer deaths | 26.8 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 7.5 | 7.6 | 7.8 | 8.3 |

| Years of life lost b | 133.5 | 39.9 | 39.9 | 39.9 | 42.0 | 44.4 | 48.7 |

| Effectiveness of screening | |||||||

| Cases prevented | 29.2 | 29.2 | 29.0 | 28.9 | 28.5 | 27.8 | |

| Advanced cases prevented a | 36.3 | 36.2 | 35.9 | 35.7 | 34.9 | 33.5 | |

| Deaths prevented | 19.4 | 19.4 | 19.3 | 19.2 | 19.0 | 18.5 | |

| Years of life saved b | 93.7 | 93.7 | 93.7 | 91.5 | 89.1 | 84.8 | |

| Healthcare costs, US $1000 b | |||||||

| Total costs of screening and treatment | 5612 | 5404 | 5411 | 5420 | 5430 | 5459 | 5512 |

| Incremental costs to no screening | −208 | −201 | −193 | −182 | −153 | −100 | |

| Cost-effectiveness ratio | c.s. | c.s. | c.s. | c.s. | c.s. | c.s. | |

Abbreviations: c.s. = cost-saving.

Advanced-stage cancer cases are stage II–IV according to the 5th edition Cancer Staging Manual from the American Joint Committee on Cancer.

Life-years and costs were discounted at the conventional 3% per year.

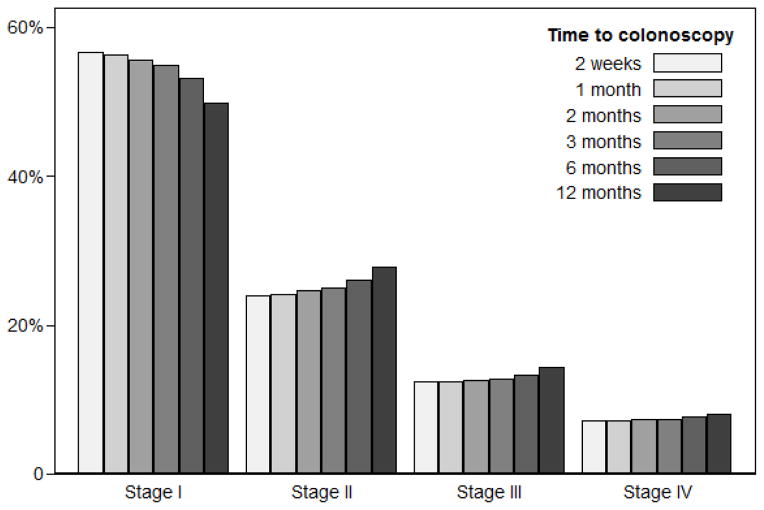

Sensitivity analyses

The influence of time to diagnostic testing, per additional month to colonoscopy, was approximately twice as high for gFOBT as for FIT, but was similar for annual FIT versus stool DNA testing every three years (Figure 3). The results were stable to assumptions on FIT sensitivity and follow-up exam sensitivity for small adenomas, but sensitive to assumptions on test specificity, the length of screening intervals and cancer progression rates. With lower false positive rates or wider screening intervals the effects of time to diagnostic colonoscopy were more than 50% larger than the base-case. A random distribution of time to colonoscopy rather than a deterministic value made hardly any difference for our main outcomes.

Figure 3.

Estimated mortality increase per additional month to diagnostic colonoscopy in patients with a positive fecal test, under various scenarios.

Abbreviation: CRC = colorectal cancer; pp = percentage point.

aEffects relative to the scenario of follow-up within two weeks from a positive result are presented within parentheses.

bSee Supplementary Table 1 for the assumed test characteristics.

cSee Supplementary Table 1 for assumed uncertainty in FIT and colonoscopy sensitivity according to lesion size or stage.

DISCUSSION

In the absence of high-quality observational data, we used an established microsimulation model to estimate the consequences of different times to colonoscopy following a positive FIT for the benefit and cost of colorectal cancer screening. Our results suggest that longer time to follow-up might lead to clinically relevant increases in the risks of colorectal cancer, advanced-stage colorectal cancer and colorectal cancer mortality. Although FIT screening remained cost-saving even with 12 months to follow-up, cancer-related mortality in patients with a positive test increased more than 15% relatively, and overall life-years gained from screening decreased nearly 10% relatively.

In our analyses, longer time to diagnostic colonoscopy slightly increased the total number of cancers diagnosed due to progression of adenomas to new cancers during that time interval. However, the relative increase in cancer-related mortality was more than three times larger than the relative increase in incidence. This difference stemmed from the relatively slow progression rate of adenomas compared to the more rapid rate of carcinomas progressing from early to more advanced stage disease. Therefore, later follow-up of positive FIT during the year after a positive test influenced the stage of diagnosis more than development of new disease. In our model, the shift to more advanced-stage of diagnosis was the primary driver for the relatively large mortality effect.

Our model results were robust using alternative assumptions regarding the sensitivity of the fecal tests and follow-up exam, but sensitive to assumptions on test specificity, the length of screening intervals and cancer progression rates (Figure 3). For patients with a positive gFOBT, longer time to follow-up resulted in larger estimated risk increases than the base case with FIT. This mainly reflects the differences in test specificity: using more specific screening tests resulted in a smaller cumulative number of false positive patients without a higher risk of cancer, and consequently, larger, less diluted effects of longer follow-up intervals for the true positive patients. Although we did not evaluate FIT with other-than-standard cutoff levels for positivity (>20 μg/g), by analogy to gFOBT, we would expect larger resulting effects with higher cutoffs, and smaller effects with lower cutoffs. Despite a lower test specificity, stool DNA testing every three years did not result in smaller mortality effects of time to follow-up than annual FIT due to the wider recommended screening intervals.20 Because of the wider intervals there were fewer total screenings and false positive patients, which offset the effects of lower test specificity. Finally, the duration of the preclinical cancer phase is uncertain,21, 22 and shorter durations increased the likelihood of disease progression and mortality in case of longer time to follow-up.

Some small prior observational studies have estimated the association of time to colonoscopy after positive gFOBT with cancer stage, however, gFOBT has different test characteristics than FIT. One study in 231 subjects found a large, but insignificant relative increase of 7% in the odds of advanced neoplasia (10 mm or more, >25% villous architecture, high-grade dysplasia or intramucosal carcinoma) per additional month to colonoscopy.8 Although this is larger than the effect we estimated for cancer, the relatively small size of the above study prohibits any meaningful conclusions from such a comparison. Another study in 100 patients found no significant association between time to follow-up and colorectal cancer incidence and mortality.23 Clearly, both studies were underpowered to detect small-to-moderate effects on incidence and mortality. In a statistical power analysis we estimated that a case-control design would require at least 3000 cases of advanced-stage colorectal cancer and a history of preceding positive FIT, to demonstrate our model’s projected 2.7% estimated relative increase in stage II–IV disease per additional month to colonoscopy, or the corresponding mortality effect (Supplementary Material, Statistical Power Analysis). Other studies have estimated the influence of time to diagnosis for any endoscopy (e.g. for symptoms), and have suggested no, or even inverse, associations,24–26 but these studies of symptomatic conditions may not be valid for inference of screening tests. In symptomatic patients, disease stage may influence the severity of symptoms, and thereby also the priority for follow-up.

In our analyses, FIT screening was suggested to be highly cost-effective (cost-saving) compared to no screening, similar to other cost-effectiveness studies.27–29 This was mainly due to averted treatment of (advanced-stage) colorectal cancer and the high associated costs. With only one gFOBT trial reporting significant effects on incidence,30 the effectiveness of FIT for cancer prevention, through the detection and removal of adenomas, is not well established. Superior performance characteristics of FIT to gFOBT-Hemoccult II and less demanding sample collection requirements suggest that FIT could be at least as effective,17 but no trial data exist.31 Our approach to estimating FIT efficacy is well-established, and has been used before in the decision analysis to inform the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.10 The simulated stage-distribution for screen-detected cancers was consistent with observed data from population-based FIT screening programs,14, 15 as were the estimated mortality effects.13

The present study has some limitations. First, in contrast with our assumptions, longer times to colonoscopy may not occur randomly, for example, they may be more common in elderly patients or in patients with comorbid conditions.6 These patients generally benefit less from screening,32 and may therefore also have smaller adverse consequences from longer times to examination after a positive FIT. Further, we assumed that false-positive results from asymptomatic benign bleeding occur randomly over individuals and that adenomas are missed randomly, while in reality, false-positive and false-negative results may cluster in specific patients or lesions, e.g. serrated polyps.33 Because FIT positive patients undergoing a diagnostic examination generally do not return to FIT screening for years, our assumptions may have understated the unknown long-term diagnostic performance of FIT, and therefore the effect of time to diagnostic colonoscopy (Figure 3).

The findings of this study are applicable primarily to patients who use fecal-based testing methods for colorectal cancer screening. Consequences of time to diagnostic colonoscopy may differ for patients who use a mix of tests for screening, including colonoscopy. Further, we focused our analysis on the effects of time to diagnostic testing after a positive test result. However, time to therapy in patients with diagnosed cancer may also vary in practice. Thus, future studies are needed to assess the interrelatedness and joint effects of the lag both in diagnostic testing and receipt of treatment on the outcomes of stool-based CRC screening.

To conclude, using modeling we found that deferring diagnostic evaluation may lead to substantial increases in mortality in FIT positive patients. Although the differences between an almost immediate evaluation and an evaluation at up to three months of a positive FIT are small, longer delays in follow-up of up to 12 months may result in more substantial losses, over time, in the overall benefits of screening.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

GRANT SUPPORT: The study was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute at the United States National Institutes of Health (# U54 CA163262, and also U01 CA152959, U01 CA151736, U24 CA171524, and P30 CA008748). This material is the result of work supported in part by resources from the VA Puget Sound Health Care System. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Cancer Institute or of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CRC

Colorectal Cancer

- FIT

Fecal Immunochemical Test

- MISCAN-Colon

Microsimulation Screening Analysis-Colon model

- NCI

National Cancer Institute

- gFOBT

guaiac Fecal Occult Blood Test

- SEER

Surveillance Epidemiology - and End Results program

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES: The authors have nothing to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS: Reinier Meester, Ann Zauber, Iris Lansdorp-Vogelaar, Jason Dominitz were involved in the study design; Reinier Meester, Iris Lansdorp-Vogelaar, were involved in the acquisition of the data; Reinier Meester, Chyke Doubeni, Ann Zauber, Douglas Corley, Iris Lansdorp-Vogelaar were involved in the interpretation of the data, and the drafting of the manuscript; Christopher Jensen, Virginia Quinn, Mark Helfand, Jason Dominitz, and Theodore Levin reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content; Reinier Meester was involved in the statistical (power) analysis.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, et al. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(1):9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. Epub 2014/01/09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hardcastle JD, Chamberlain JO, Robinson MH, et al. Randomised controlled trial of faecal-occult-blood screening for colorectal cancer. Lancet. 1996;348(9040):1472–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)03386-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kronborg O, Fenger C, Olsen J, et al. Randomised study of screening for colorectal cancer with faecal-occult-blood test. Lancet. 1996;348(9040):1467–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)03430-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mandel JS, Church TR, Ederer F, et al. Colorectal cancer mortality: effectiveness of biennial screening for fecal occult blood. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91(5):434–7. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.5.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Partin MR, Burgess DJ, Burgess JF, Jr, et al. Organizational predictors of colonoscopy follow-up for positive fecal occult blood test results: an observational study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24(2):422–34. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-1170. Epub 2014/12/05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chubak J, Garcia MP, Burnett-Hartman AN, et al. Time to Colonoscopy after Positive Fecal Blood Test in Four U.S. Health Care Systems. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25(2):344–50. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0470. Epub 2016/02/05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peterson K, Carson S, Humphrey L, et al. Patients with Positive Screening Fecal Occult Blood Tests: Evidence Brief on the Relationship Between Time Delay to Colonoscopy and Colorectal Cancer Outcomes. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gellad ZF, Almirall D, Provenzale D, et al. Time from positive screening fecal occult blood test to colonoscopy and risk of neoplasia. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54(11):2497–502. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0653-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network (CISNET) Colorectal Cancer Model Profiles. National Cancer Institute; 2013. [January 1, 2013]. Available from: http://cisnet.cancer.gov/colorectal/profiles.html/ [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zauber AG, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Knudsen AB, et al. Evaluating test strategies for colorectal cancer screening: a decision analysis for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(9):659–69. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-9-200811040-00244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jorgensen OD, Kronborg O, Fenger C. A randomised study of screening for colorectal cancer using faecal occult blood testing: results after 13 years and seven biennial screening rounds. Gut. 2002;50(1):29–32. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.1.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, O’Brien MJ, et al. Randomized comparison of surveillance intervals after colonoscopic removal of newly diagnosed adenomatous polyps. The National Polyp Study Workgroup. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(13):901–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304013281301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiu HM, Chen SL, Yen AM, et al. Effectiveness of fecal immunochemical testing in reducing colorectal cancer mortality from the One Million Taiwanese Screening Program. Cancer. 2015;121(18):3221–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29462. Epub 2015/05/23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parente F, Marino B, DeVecchi N, et al. Faecal occult blood test-based screening programme with high compliance for colonoscopy has a strong clinical impact on colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2009;96(5):533–40. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6568. Epub 2009/04/10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parente F, Vailati C, Boemo C, et al. Improved 5-year survival of patients with immunochemical faecal blood test-screen-detected colorectal cancer versus non-screening cancers in northern Italy. Dig Liver Dis. 2015;47(1):68–72. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2014.09.015. Epub 2014/10/13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weinstein MC, Siegel JE, Gold MR, et al. Recommendations of the Panel on Cost-effectiveness in Health and Medicine. Jama. 1996;276(15):1253–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, et al. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58(3):130–60. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lieberman DA, Rex DK, Winawer SJ, et al. Guidelines for colonoscopy surveillance after screening and polypectomy: a consensus update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(3):844–57. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meester RG, Doubeni CA, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, et al. Variation in Adenoma Detection Rate and the Lifetime Benefits and Cost of Colorectal Cancer Screening: A Microsimulation Model. Jama. 2015;313(23):2349–58. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.6251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rex DK, Johnson DA, Anderson JC, et al. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines for colorectal cancer screening 2009 [corrected] Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(3):739–50. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuntz KM, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Rutter CM, et al. A systematic comparison of microsimulation models of colorectal cancer: the role of assumptions about adenoma progression. Med Decis Making. 2011;31(4):530–9. doi: 10.1177/0272989X11408730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brenner H, Altenhofen L, Katalinic A, et al. Sojourn time of preclinical colorectal cancer by sex and age: estimates from the German national screening colonoscopy database. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174(10):1140–6. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wattacheril J, Kramer JR, Richardson P, et al. Lagtimes in diagnosis and treatment of colorectal cancer: determinants and association with cancer stage and survival. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28(9):1166–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03826.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramos M, Esteva M, Cabeza E, et al. Lack of association between diagnostic and therapeutic delay and stage of colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(4):510–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Korsgaard M, Pedersen L, Sorensen HT, et al. Delay of treatment is associated with advanced stage of rectal cancer but not of colon cancer. Cancer Detect Prev. 2006;30(4):341–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murchie P, Raja EA, Brewster DH, et al. Time from first presentation in primary care to treatment of symptomatic colorectal cancer: effect on disease stage and survival. Br J Cancer. 2014;111(3):461–9. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Kuntz KM, Knudsen AB, et al. Stool DNA testing to screen for colorectal cancer in the Medicare population: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(6):368–77. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-153-6-201009210-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knudsen AB, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Rutter CM, et al. Cost-effectiveness of computed tomographic colonography screening for colorectal cancer in the medicare population. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102(16):1238–52. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu GH, Wang YM, Yen AM, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of colorectal cancer screening with stool DNA testing in intermediate-incidence countries. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:136. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-136. Epub 2006/05/26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mandel JS, Church TR, Bond JH, et al. The effect of fecal occult-blood screening on the incidence of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(22):1603–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011303432203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quintero E, Castells A, Bujanda L, et al. Colonoscopy versus fecal immunochemical testing in colorectal-cancer screening. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(8):697–706. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Gulati R, Mariotto AB, et al. Personalizing age of cancer screening cessation based on comorbid conditions: model estimates of harms and benefits. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(2):104–12. doi: 10.7326/M13-2867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rex DK, Ahnen DJ, Baron JA, et al. Serrated lesions of the colorectum: review and recommendations from an expert panel. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(9):1315–29. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.161. quiz 4, 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.