Approximately half of pregnancies occurring each year in the United States are unintended: They either occurred too soon or were not intended at any time.1 This commonly cited statistic is testament to the dominance of unintended pregnancy as a public health benchmark for measuring and improving women's reproductive health.2 In addition to its use as a public health metric, this timing-based definition of unintended pregnancy is reflected in pregnancy planning paradigms in clinical practice. According to these paradigms, women are expected to map out their intentions regarding whether and when to conceive, and to formulate specific plans to follow through on their intentions.3

CURRENT PLANNING PARADIGM

While there is no evidence that planning benefits all women, it has been widely promoted as a universal ideal. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends reproductive life planning for women and assigns to health care providers the role and responsibility of helping women to define and implement pregnancy plans.3 We propose, however, that public health and clinical efforts focused on reducing unintended pregnancy and improving pregnancy outcomes solely by promoting planning are subject to several important limitations.

First, implicit in the planning ideal is the assumption that all women hold clear and unequivocal timing-based intentions. Yet rather than evoking a binary distinction between whether a pregnancy was “intended” or “unintended” at a certain time, women often describe their pregnancies as falling on a continuum between the two.4 This characterization reflects an important conceptual facet of women's pregnancy preferences beyond intentions: desire to achieve or to avoid pregnancy. While some women hold strong desires either to achieve or to avoid pregnancy, others are ambivalent or indifferent, holding either some degree of desire to both achieve and avoid pregnancy or no strong desire either way.5 Moreover, the strength and polarity of women's desires may fluctuate.6 Current preventive strategies based on structured planning lack the flexibility to accommodate women with ambivalent, indifferent or fluctuating desires. Recommending effective contraceptive use as a means of avoiding pregnancy for a certain period of time does not fully address the complexity of these women's thoughts about conception and implies that their ambivalence or indifference can or must be resolved. In fact, only women with the strongest and most consistent desire to avoid pregnancy are likely to use contraceptives correctly and consistently over time.6 For women with ambivalent, indifferent or fluctuating desires, highly effective contraceptives may be unappealing precisely because they negate the possibility of an unplanned (but welcome) conception.7

Second, planning paradigms may overlook another important facet of women's pregnancy preferences: emotional orientations. Paradoxically, some women have highly positive emotional responses to the prospect of pregnancy even when they express an immediate, unambivalent desire to avoid conception or a clear intention not to have any more children.8,9 Moreover, these emotional responses often provide an indication of the anticipated balance both of immediate consequences of pregnancy (positive and negative) and of future life impacts of childbearing.8 For example, on the one hand, having a child might be difficult economically, and thus delaying or ending childbearing may be viewed as prudent. On the other hand, a child might bring many rewards, including personal fulfillment, feelings of closeness to a partner, or a sense of progress or purpose in life. If the positives outweigh the negatives, or if economic or other circumstances seem unlikely to improve over time anyway, women might have favorable emotional orientations toward pregnancy and childbearing despite expressing intentions or desires to delay or avoid conception. For these women, standard timing-based definitions of unintended pregnancy fail to capture the trade-offs of a possible pregnancy, which, in turn, may not be well represented by the language of planning.

Third, conventional planning paradigms are imbued with the normative belief that unintended pregnancies are uniformly negative events that necessarily result in adverse consequences. Yet the complexity of women's prospective pregnancy desires and emotional orientations toward pregnancy demonstrates clearly that while some unintended pregnancies would indeed be undesired, others would be welcome.10,11 Still others would not be entirely unanticipated, and these may also be viewed positively.12 Emotional orientations toward pregnancy seem to offer an indication of the psychosocial stress that would likely arise should a pregnancy occur, and some studies have suggested that such orientations may be more important than timing-based intentions in predicting negative outcomes.13,14 Moreover, other studies have shown that women's preconception desires and emotional orientations toward pregnancy may evolve after conception has occurred.15–17 Thus, a pregnancy that was not explicitly desired or whose possibility was viewed negatively before conception may become a welcome or wanted one.

A final limitation of current pregnancy planning approaches is the widespread assumption that they are applicable to all women. Research has revealed a tension between the ideal of planning and the reality that for many women, planning may be irrelevant or unattainable. Such irrelevance may stem from a belief in the power of fate or from values surrounding the desirability of planning.18 These values may reflect a general life perspective or may be specific to the context of fertility, in that reproduction is viewed as a process that cannot or should not be overly constrained. For these women, preventive efforts focused on eliciting timing-based pregnancy intentions and formulating plans to implement them may simply fail to be meaningful. For other women, planning a pregnancy may be out of reach because of social norms regarding the circumstances in which it is considered acceptable (e.g. after one has married and achieved financial security).12,19 These women often conceive in nonnormative circumstances and may experience considerable stigma for having unplanned pregnancies.12,20 Yet if they do articulate a desire to plan, they may also experience stigma from providers or their peers precisely because they express a desire to plan a pregnancy outside the expected ideals regarding social and economic readiness.19

A NEW CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

What can researchers, public health practitioners and clinicians engaged in efforts to reduce unintended pregnancy and improve pregnancy outcomes do in response to these limitations? As a first step, we propose a conceptual model that integrates insights from recent research and provides a framework for informing women-centered approaches to preventing undesired pregnancies and improving outcomes.

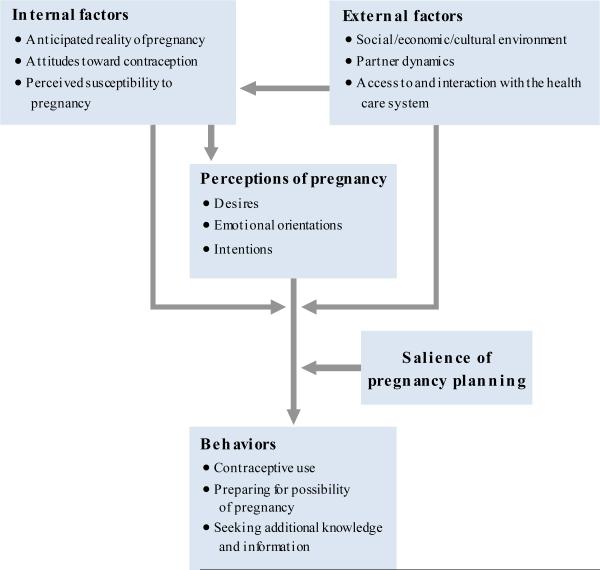

Our model has two aims: to accommodate the complexity of women's thoughts about future pregnancy, or what we term “perceptions of pregnancy”; and to offer an alternative to viewing all unintended pregnancies as negative events, the notion of “pregnancy acceptability” (Figure 1). At the center of the model are women's perceptions of pregnancy, which we propose as an umbrella term to capture not only pregnancy intentions, but also more immediate desires to achieve and to avoid pregnancy, as well as emotional orientations toward pregnancy. Theoretically, these perceptions can be influenced by myriad internal factors, including the anticipated reality of a pregnancy in the context of a woman's life, attitudes toward contraception and perceived susceptibility to pregnancy. Perhaps the most important of these is women's anticipated realities of pregnancy, including the expected positive and negative social and economic impacts, as well as how the pregnancy might be valued in the context of internalized social and cultural norms regarding pregnancy, childbearing, motherhood and abortion.8,12,21

FIGURE 1.

Conceptual model of a framework for informing women-centered approaches to preventing undesired pregnancies and helping women achieve their reproductive goals

Attitudes toward contraception are also an important influence on these perceptions. For example, a woman who believes that there is no contraceptive method she would be comfortable using may have difficulty forming timing-based pregnancy intentions because she feels unable to exert reliable control over her fertility. Similarly, for a woman who believes that contraceptive use is a sin because it is against her religious beliefs and that whether she gets pregnant is up to God, timing-based intentions and desires to achieve or avoid pregnancy may be irrelevant.22

Personal beliefs regarding the ability to conceive may also play a role. For example, a woman who believes she is not able to get pregnant may be ambivalent about pregnancy because she may want to test her fecundity, but at the same time may not actually desire a child.23,24 All of these internal factors are in turn shaped by external factors, such as the wider sociocultural and policy environment; the dynamics of intimate and social relationships, including reproductive coercion and intimate partner violence; and access to and interactions with the health care system, as well as financial and logistical barriers to care.

The translation of women's perceptions of pregnancy into behaviors may also be strongly influenced by both the internal and the external factors described above. For example, negative attitudes toward contraception and mistrust of contraceptive technologies may mean that even women with clear intentions or desires to delay or avoid pregnancy may not engage in behaviors that are consistent with preventing pregnancy.25 Furthermore, even if a woman who wishes to avoid pregnancy has a particular method in mind, lack of access to contraceptives or her male partner's insistence on not using contraceptives may affect the translation of perceptions of pregnancy into behaviors by rendering use of the method unrealistic or impossible.26

The translation of perceptions into behaviors is also affected by the salience of pregnancy planning. In our model, the applicability and meaningfulness of planning, rather than the presence of plans per se, are key antecedents of the translation of perceptions into behaviors. Following this model, providers and public health practitioners would begin by assessing the meaningfulness of planning to women, rather than assuming that all women embrace the concept. To help women translate their perceptions of pregnancy into behaviors, providers would then draw upon a wider range of possible approaches than simply suggesting that women either plan to use contraceptives or receive preconception counseling. For example, pregnancy planning is unlikely to resonate with women who are ambivalent about conceiving; providers would encourage such women to discuss the possibility of conception and would help them to take steps to prepare for a healthy pregnancy. Women who might desire to avoid pregnancy, but who view themselves as unlikely to get pregnant or perceive no good contraceptive options, would be guided to seek additional information about their fecundity or to request personalized discussions about their ideal contraceptive.

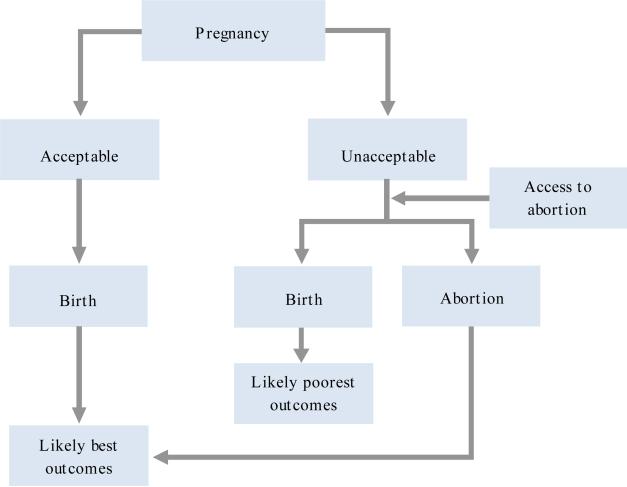

Traditionally, pregnancies that women retrospectively report as intended “later” or “not at all” according to timing-based definitions would be assumed to have an elevated likelihood of resulting in adverse outcomes. Our model departs substantially from this paradigm (Figure 2). Instead, we suggest that the most important element in determining whether a pregnancy will result in adverse outcomes is the extent to which a woman judges it to be acceptable once it has occurred. The concept of acceptability builds on the long-standing concept of wantedness, adding several important aspects: personal life circumstances, including financial means and relationship quality; internalized social and cultural norms pertaining to childbearing; and personal beliefs regarding pregnancy, motherhood and abortion. For example, after conceiving, a woman may decide that her pregnancy is wanted, but may feel compelled to end it because of a relationship or financial situation she finds unsuitable. Or a woman may decide that her pregnancy is unwanted, but may feel, for religious reasons, that she cannot have an abortion and that continuing the pregnancy is the most acceptable option.

FIGURE 2.

Conceptual model of how the acceptability of a pregnancy to a woman may be related to pregnancy outcomes

The relationship between acceptability and measurable outcomes will vary depending on whether the pregnancy results in birth or abortion, which in turn depends on individual preferences and available options.* We hypothesize that a woman who judges her pregnancy to be acceptable, regardless of whether it was planned, and goes on to give birth is more likely to experience positive personal and social outcomes than a woman who judges her pregnancy to be unacceptable. Our model also accommodates the fact that women who find having an ongoing pregnancy unacceptable and are able to choose abortion may experience more positive outcomes than those whose unacceptable pregnancy results in birth.27,28

WOMEN-CENTERED STRATEGIES

In proposing this model, we hope to pave the way for the development of strategies to help women achieve their reproductive goals. At the clinical level, approaching the possibility of pregnancy in terms of women's own perceptions about the acceptability and anticipated reality of a pregnancy allows them to freely communicate their perspectives and avoids the need to impose a planning structure that may be inappropriate or irrelevant. This approach will better equip providers to link women's perceptions of pregnancy to tailored counseling, which may range from helping women integrate their pregnancy preferences into contraceptive decision making to considering the appropriateness of steps to prepare for a potential pregnancy, or may include a combination of strategies.

At the population health level, the incorporation into surveys of questions about desires to achieve or avoid pregnancy, emotional orientations toward pregnancy, and anticipated positive and negative life impacts of pregnancy could help researchers prospectively distinguish pregnancies that would be unexpected and welcome from those that would be undesired or unwelcome. Despite the diversity in women's perceptions of pregnancy, most public and academic discourse still portrays unintended pregnancies as simple errors of timing that could have been prevented by planning and that will necessarily result in poor outcomes. In fact, there is little robust evidence that unintended pregnancy is an independent risk factor for poor maternal or neonatal outcomes.29 Many studies suggesting such a link are problematic in terms of their ability to control for potentially confounding influences.29 Given prior conceptual limitations, this lack of evidence is perhaps not surprising for another reason: None of these studies distinguished between unintended pregnancies that women found acceptable and ones that women found unacceptable. Investigating the elements that make pregnancies unacceptable to women, determining whether these pregnancies are more likely than others to have adverse health and social consequences, and identifying women at particular risk are important targets for future public health research.

We emphasize that the prevention of adverse health outcomes is not the only motivation for taking a holistic approach to women's perceptions of pregnancy. From a reproductive rights perspective, ensuring that individuals can make decisions about reproduction is a critical goal in its own right. Public health preventive strategies tend to focus on increasing the use of highly effective contraceptives and on emphasizing the negative consequences of unintended pregnancy. But these strategies could be better informed using a reproductive justice approach, which places individuals at the forefront and prioritizes the complexity and diversity in women's perceptions of pregnancy. Unintended pregnancies, as defined by their timing, are disproportionately common among low-income women and women of color.1 Broadening the current planning paradigm––with its attendant normative guidelines regarding the conditions under which a pregnancy should or should not occur––also has the important advantages of disengaging from a cultural viewpoint in which reproduction is differentially valued on the basis of race or ethnicity, class or socioeconomic status, and of reducing associated stigma. Being conscious of our own normative beliefs and allowing women to decide for themselves whether a pregnancy, when it occurs, is acceptable in the context of their lives are key steps toward empowering all women to build the lives and families they desire.

Acknowledgments

Support for this research was provided in part by grants P2C HD047879 and 1R21HD076327–01A1 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Veterans Administration Health Services Research and Development Career Development Award CDA 14–412, and grant P60MD006902 from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. The authors thank Whitney Wilson for expert assistance in the preparation of the figures.

Biography

Abigail R.A. Aiken is assistant professor, LBJ School of Public Affairs; and faculty associate, Population Research Center, University of Texas at Austin. Sonya Borrero is associate professor, Center for Research on Health Care, Department of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh; and codirector, VA Advanced Fellowship Program in Women's Health, VA Center for Health Equity Research and Promotion, VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System. Lisa S. Callegari is assistant professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle; and advanced research fellow, Health Services Research and Development, Puget Sound Health Care System, Department of Veterans Affairs, Seattle. Christine Dehlendorf is associate professor, Departments of Family and Community Medicine; Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Sciences; and Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of California, San Francisco.

Footnotes

Pregnancies may of course also end in miscarriage, but this outcome is not discussed here because it does not depend on an individual's perceptions or behaviors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Finer LB, Zolna MR. Declines in unintended pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;374:843–852. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1506575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Healthy People 2020. 2010 https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/family-planning/objectives.

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention My reproductive life plan. 2016 http://www.cdc.gov/preconception/reproductiveplan.html.

- 4.Bachrach CA, Newcomer S. Intended pregnancies and unintended pregnancies: distinct categories or opposite ends of a continuum? Family Planning Perspectives. 1999;31(5):251–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller WB, Barber JS, Gatny HH. The effects of ambivalent fertility desires on pregnancy risk in young women in the USA. Population Studies. 2013;67(1):25–38. doi: 10.1080/00324728.2012.738823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones RK, et al. Using longitudinal data to understand changes in consistent contraceptive use. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2015;47(3):131–139. doi: 10.1363/47e4615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Higgins JA, Popkin RA, Santelli JS. Pregnancy ambivalence and contraceptive use among young adults in the United States. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2012;44(4):236–243. doi: 10.1363/4423612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aiken AR, Dillaway C, Mevs-Korff N. A blessing I can't afford: factors underlying the paradox of happiness about unintended pregnancy. Social Science & Medicine. 2015;132:149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.03.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aiken AR. Happiness about unintended pregnancy and its relationship to contraceptive desires among a predominantly Latina cohort. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2015;47(2):99–106. doi: 10.1363/47e2215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aiken AR, Potter JE. Are Latina women ambivalent about pregnancies they are trying to prevent? Evidence from the Border Contraceptive Access Study. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2013;45(4):196–203. doi: 10.1363/4519613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoo SH, Guzzo KB, Hayford SR. Understanding the complexity of ambivalence toward pregnancy: Does it predict inconsistent use of contraception? Biodemography and Social Biology. 2014;60(1):49–66. doi: 10.1080/19485565.2014.905193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edin K, Kefalas M. Promises I Can Keep: Why Poor Women Put Motherhood Before Marriage. University of California Press; Berkeley: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blake SM, et al. Pregnancy intentions and happiness among pregnant black women at high risk for adverse infant health outcomes. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2007;39(4):194–205. doi: 10.1363/3919407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sable MR, et al. Pregnancy wantedness and adverse pregnancy outcomes: differences by race and Medicaid status. Family Planning Perspectives. 1997;29(2):76–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hass PH. Wanted and unwanted pregnancies: a fertility decision-making model. Journal of Social Issues. 1974;30(4):125–165. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller WB. Relationships between the intendedness of conception and the wantedness of pregnancy. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1974;159(6):396–406. doi: 10.1097/00005053-197412000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stanford JB, et al. Defining dimensions of pregnancy intendedness. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2000;4(3):183–189. doi: 10.1023/a:1009575514205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zabin LS. Ambivalent feelings about parenthood may lead to inconsistent contraceptive use—and pregnancy. Family Planning Perspectives. 1999;31(5):250–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borrero S, et al. “It just happens”: a qualitative study exploring low-income women's perspectives on pregnancy intention and planning. Contraception. 2015;91(2):150–156. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geronimus AT. Damned if you do: culture, identity, privilege, and teenage childbearing in the United States. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;57(5):881–893. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00456-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kendall C, et al. Understanding pregnancy in a population of inner-city women in New Orleans—results of qualitative research. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;60(2):297–311. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Casterline JB, El-Zeini LO. The estimation of unwanted fertility. Demography. 2007;44(4):729–745. doi: 10.1353/dem.2007.0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Polis CB, Zabin LS. Missed conceptions or misconceptions: perceived infertility among unmarried young adults in the United States. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2012;44(1):30–38. doi: 10.1363/4403012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McQuillan J, Greil AL, Shreffler KM. Pregnancy intentions among women who do not try: focusing on women who are okay either way. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2011;15(2):178–187. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0604-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frost JJ, Lindberg LD, Finer LB. Young adults’ contraceptive knowledge, norms and attitudes: associations with risk of unintended pregnancy. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2012;44(2):107–116. doi: 10.1363/4410712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Potter JE, et al. Unmet demand for highly effective postpartum contraception in Texas. Contraception. 2014;90(5):488–495. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.06.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Upadhyay UD, Biggs MA, Foster DG. The effect of abortion on having and achieving aspirational one-year plans. BMC Women's Health. 2015;15:102. doi: 10.1186/s12905-015-0259-1. doi:10.1186/s12905-015-0259-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herd P, et al. The implications of unintended pregnancies for mental health in later life. American Journal of Public Health. 2016;106(3):421–429. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gipson JD, Koenig MA, Hindin MJ. The effects of unintended pregnancy on infant, child, and parental health: a review of the literature. Studies in Family Planning. 2008;39(1):18–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2008.00148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]