Abstract

Chronic Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is associated with increased incidence of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Several studies have demonstrated regression of indolent lymphoma with antiviral therapy (AVT) alone. However, the role of AVT in HCV-infected patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is unclear. We therefore analyzed AVT’s impact on oncologic outcomes of HCV-infected patients (cases) who developed DLBCL. Cases seen at our institution (June 2004-May 2014) were matched with uninfected counterparts (controls) and then divided according to prior AVT consisting of interferon-based regimens. We studied 304 patients (76 cases and 228 controls). More cases than controls had extranodal (79% v 72%; p=0.07) and upper gastrointestinal (GI; 42% v 24%; p=0.004) involvement. Cases never given AVT had DLBCL more refractory to first-line chemotherapy than that in the controls (33% v 17%; p=0.05) and exhibited a trend toward more progressive lymphoma at last examination compared to controls (50% v 32%; p=0.09) or cases given AVT (50% v 27%; p=0.06). Cases never given AVT had worse 5-year overall survival (OS) rates than did the controls (HR, 2.3 [95% CI, 1.01-5.3]; p=0.04). Furthermore, AVT improved 5-year OS rates among cases in both univariate (median [Interquartile range]: 39 [26-56] v 16 [6-41] months, p=0.02) and multivariate analyses (HR=0.21 [95% CI, 0.06-0.69]; p=0.01). This study highlights the negative impact of chronic HCV on survival of DLBCL patients and shows that treatment of HCV infection is associated with a better cancer response to chemotherapy and improves 5-year OS.

Keywords: hepatitis C virus, diffuse large b-cell lymphoma, antiviral therapy, overall survival

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a known hepatotropic virus associated with development of hepatocellular carcinoma.1,2 In addition, researchers have found evidence of its lymphotropism in epidemiologic, laboratory, and clinical studies.3 For instance, epidemiologic data demonstrated a close association between chronic HCV infection and development of B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs), particularly marginal zone lymphoma, lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma and diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL).4-8 Authors reported also the presence of HCV genomic material and alteration of gene expression in lymphocytes of infected patients,9,10 with persistence of inflammatory responses in these cells long after clearance of the virus by antiviral therapy (AVT).11 However, the strongest evidence of this association is the clinical regression of indolent lymphoma with AVT administered without chemotherapy (CT).12-14

Unfortunately, determining the impact of HCV infection on DLBCL prognosis and the role of AVT in HCV-infected DLBCL patients has been difficult, likely because of the more aggressive nature of this NHL subtype than that of indolent lymphomas, preventing the use of AVT without CT. In two recent review articles,3,15 the authors concluded that AVT does not play a significant role in DLBCL management in view of contradictory results in a few case series studying the effect of AVT given after CT.16-19 It should be noted that interferon (IFN) was the main antiviral used in these reports. Importantly, when IFN-based therapy is given after DLBCL diagnosis, the effect of viral suppression on oncologic outcomes is confounded by the direct anti-lymphoma activity of IFN.20

To overcome these knowledge gaps, we analyzed herein the effect of AVT on the oncologic outcomes in HCV-infected patients who were given IFN-based therapy before DLBCL diagnosis.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

In this retrospective cohort study, the medical records of patients with HCV infection who developed DLBCL and seen at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center from June 2004 to May 2014 were reviewed. We only analyzed patients who had a proven infection (detectable HCV RNA in serum and/or a history of AVT). Human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients and those who underwent follow-up for less than 6 months were excluded.

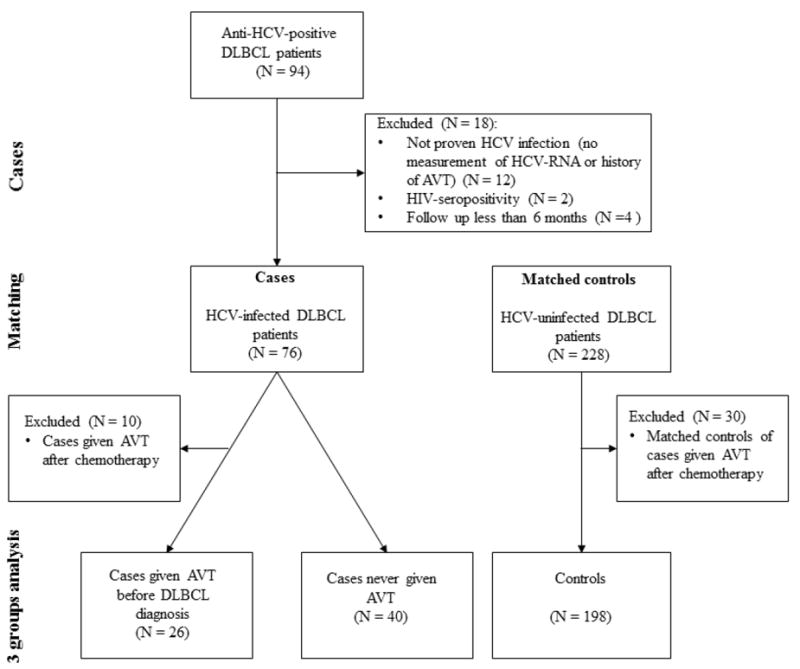

Subsequently, HCV-infected DLBCL patients (cases) were matched with uninfected controls (HCV antibody-negative DLBCL patients) at a ratio of 1:3 (Fig. 1). The matching variables were the year of DLBCL diagnosis, sex, age (±5 years), and Ann Arbor stage (1-2 or 3-4). This study was approved by the MD Anderson Institutional Review Board.

Figure 1. Flow diagram.

AVT indicates antiviral therapy; CT, chemotherapy; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

Oncologic parameters

Data on DLBCL characteristics extracted from the patient records at the time of diagnosis consisted of: Ann Arbor Stage, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance score, presence of B symptoms, International Prognostic Index (IPI) score, site of extra nodal involvement, bone marrow involvement, and onset of DLBCL (de novo or transformed). Pathology reports were reviewed by a pathologist at MD Anderson to further classify DLBCL according to immunohistochemistry as germinal center B cell (GCB) or non-GCB. Information on all treatment modalities performed, including CT, radiotherapy, and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HCT) as well as AVT and its timing relative to DLBCL diagnosis, was collected.

Transformed DLBCL was defined as either a previous history of indolent lymphoma before DLBCL diagnosis or concomitant mixed/discordant biopsies demonstrating indolent and aggressive lymphoma simultaneously. Based on radiologic findings, the patients with liver, stomach, pancreatic, and/or splenic involvement of DLBCL were combined in the upper gastrointestinal (GI) involvement group. A good performance status was defined as an ECOG score of 0-1, whereas a poor performance status was defined as an ECOG score of 2-4. The low, intermediate and high-risk IPI scores were 0-1, 2-3 and 4-5, respectively. The revised 2007 Cheson criteria were applied to defining response of DLBCL to CT, distinguishing complete response (CR), partial response (PR), and progressive disease (PD). Overall survival (OS) was measured from the start date for CT to the date of the last follow-up examination or death resulting from any cause.21 Progression-free survival (PFS) was measured from the start date for CT to the date of DLBCL progression or relapse.21 Disease-free survival (DFS) was applied only to patients who had CR after first-line CT and was measured from the end date for CT to the date of DLBCL relapse.21

Infectious parameters

Data on HCV infection characteristics, such as date of HCV infection diagnosis, time from first documented HCV risk exposure to DLBCL diagnosis, HCV RNA viral load and genotype, rs12979860 genotype (previously known as interleukin-28B), prior AVT, and virologic response, were collected.

Sustained virologic response (SVR) was defined as an undetectable HCV RNA viral load at 24 weeks after AVT completion, the virologic endpoint used for patients treated with IFN-containing regimens.22

Hepatic parameters

Liver fibrosis status at DLBCL diagnosis and after completion of CT was reviewed. Cirrhosis was identified in the patients using either a liver biopsy or a combination of analysis of clinical manifestations of cirrhosis, radiologic findings, and noninvasive fibrosis markers (FIBROSpect II test; Prometheus Laboratories, San Diego, CA). Portal hypertension was defined according to a combination of clinical and radiologic signs suggestive of this condition. Progression of cirrhosis was indicated by worsening of the Child-Pugh score from baseline parameters. Acute-on-chronic liver failure was defined as previously reported.23

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the study population. The endpoints were oncologic (response to first-line CT, relapse or progression, oncologic response at the last follow-up examination, 5-year OS rate, and 3-year PFS/DFS rates), virologic (SVR), and hepatic (worsening of cirrhosis after CT, and hepatic failure).

To determine the effect of HCV infection on the clinical presentation of DLBCL, we compared the characteristics of categorical variables among cases and controls using generalized estimating equations and the logit link function to account for correlations in the matched groups.

To determine the effect of HCV infection on survival and oncologic outcomes, the patients were further separated into three groups: cases never given AVT, cases given AVT before DLBCL diagnosis, and uninfected controls (Fig 1). We first compared oncologic outcomes between the three groups, and then conducted a two-by-two comparison between each case group and controls, and between the two case groups. The 5-year OS, 3-year PFS, and 3-year DFS rates in these three groups were compared, with the differences evaluated using a stratified log-rank test. Finally, a multivariable stratified Cox regression model was used to determine the association between HCV infection and OS after adjusting for potential confounders.

Furthermore, to determine whether AVT affects the risk of death and adverse oncologic outcomes in HCV-infected patients, the cases given AVT were compared with those never given AVT. Categorical variables were compared using a chi-square test or the Fisher exact test. Survival rates were plotted on Kaplan-Meier curves and compared with the log-rank test. A multivariable Cox regression model was used to determine the effect of AVT on the risk of death after adjusting for potential confounders.

Final results were presented as hazard ratios (HRs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and P values. All statistical tests were two-sided and conducted using the SAS software program (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

We identified 94 HCV-infected patients with DLBCL during the study period. We excluded 18 patients for different reasons (Fig 1). We considered the remaining 76 patients to be the cases and included them in our analysis. Most of them were male (70%), white (68%), and had a median age of 59 years (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics, DLBCL Characteristics, and Oncologic Treatment in the HCV-Infected Cases and Uninfected Controls

| Characteristic | Cases (N=76) No. of Patients (%) |

Controls (N=228) No. of Patients (%) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years [median (IQR)] | 59 (53-63) | 59 (53-64) | Matched |

| Sex | N = 76 | N = 228 | Matched |

| Male | 53 (70) | 159 (70) | |

| Female | 23 (30) | 69 (30) | |

| Race | N = 75 | N = 225 | 0.01 |

| White | 51 (68) | 175 (78) | |

| Black | 14 (19) | 9 (4) | |

| Hispanic | 6 (8) | 33 (15) | |

| Other* | 4 (5) | 8 (3) | |

| Transformation of DLBCL | N = 76 | N = 228 | 0.28 |

| De novo DLBCL | 55 (72) | 178 (78) | |

| Transformed DLBCL† | 21 (28) | 50 (22) | |

| DLBCL subtype | N = 54 | N = 198 | 0.39 |

| GCB | 30 (56) | 123 (62) | |

| Non-GCB | 24 (44) | 75 (38) | |

| Ann Arbor stage | N = 75 | N = 228 | Matched |

| 1-2 | 15 (20) | 45 (20) | |

| 3-4 | 60 (80) | 183 (80) | |

| ECOG score | N = 62 | N = 207 | 0.13 |

| 0-1 | 44 (71) | 165 (80) | |

| 2-4 | 18 (29) | 42 (20) | |

| IPI score | N = 58 | N = 205 | 0.37 |

| Low risk (0-1) | 21(36) | 63 (31) | |

| Intermediate risk (2-3) | 24 (41) | 106 (51) | |

| High risk (4-5) | 13 (23) | 36 (18) | |

| Presence of B symptoms | 24/73 (33) | 82/219 (38) | 0.47 |

| Extra nodal involvement | 60/76 (79) | 164/228 (72) | 0.07 |

| Upper GI‡ and splenic involvement | 32/76 (42) | 54/228 (24) | 0.004 |

| Para-aortic lymph node involvement | 44/76 (58) | 110/218 (50) | 0.24 |

| Bone marrow involvement | 27/74 (36) | 61/228 (27) | 0.08 |

| Cirrhosis at DLBCL diagnosis | 18/76 (24) | 4/220 (2) | <0.0001 |

| First-line CT | N = 75 | N = 228 | 0.91 |

| R-CHOP | 54 (72) | 165 (72) | |

| Other§ | 21 (28) | 63 (28) | |

| Second-line CT | N = 33 | N = 105 | 0.55 |

| R-ICE | 19 (58) | 64 (61) | |

| Other║ | 14 (42) | 41 (39) | |

| Radiotherapy | 18/74 (24) | 62/228 (27) | 0.55 |

| HCT | 16/74 (22) | 66/228 (29) | 0.15 |

| Mortality/survival | N = 76 | N = 228 | 0.79 |

| Dead | 30 (39) | 94 (41) | |

| Cause of death | N = 26 | N = 71 | -- |

| Refractory DLBCL | 15 (58) | 45 (63) | |

| Liver failure | 2 (8) ¶ | 0 | |

| Infections other than HCV | 4 (15) | 9 (13) | |

| Others# | 5 (19) | 17 (24) |

DLBCL indicates diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; GCB, germinal center B-cell; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; IPI, International Prognostic Index; GI, gastrointestinal; CT, chemotherapy; R-CHOP, rituximab-cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone; R-ICE, rituximab-ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide; HCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; HCV, hepatitis C virus.

Asian or Pacific Islander.

According to composite or discordant biopsy results (lymph node and bone marrow biopsies) or a previous history of indolent lymphoma.

Stomach, liver, and/or pancreas.

Rituximab-etoposide, prednisone, Oncovin (vincristine), cyclophosphamide, and hydroxydaunorubicin (doxorubicin) (R-EPOCH); rituximab-cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin (Adriamycin), and dexamethasone (R-hyper-CVAD); or CHOP. Only three patients did not receive rituximab.

Rituximab-etoposide, methylprednisolone, cytarabine, and cisplatin (R-ESHAP); rituximab-gemcitabine and oxaliplatin (R-GEMOX); rituximab-dexamethasone, cytarabine, and cisplatin (R-DHAP); or rituximab-mesna, ifosfamide, novantrone, and etoposide (R-MINE).

Bulky disease at the level of hepatic hilum (n=1), septic shock with multiorgan failure (n=1).

Myocardial infarction, tamponade, or other cancers.

DLBCL characteristics

The majority of the cases had de novo DLBCL (72%) and GCB as the cell of origin (56%). Also, most of the cases had Ann Arbor stage 3-4 disease (80%), no B symptoms (67%), a good performance statuses (71%), intermediate to high-risk IPI scores (64%), para-aortic lymph node involvement (58%), and extranodal involvement (79%), with the upper GI tract as the region the most often involved (42%).

Most cases were given rituximab-cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) as first-line CT (72%) and rituximab-ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide (R-ICE) as second-line CT (58%). Twenty two percent of the cases underwent HCT, and 24% received radiotherapy (Table 1).

Infectious characteristics

Forty-eight cases (63%) were known to have chronic HCV infection before onset of DLBCL, whereas 28 cases (37%) had HCV infection diagnosed at the same time or after cancer was diagnosed. Among patients with available data, most of the cases (77%) were infected for more than 30 years, and half of them (50%) had baseline HCV RNA loads ≥6 million IU/ml. The majority had HCV genotype 1 (73%) and rs12979860 genotype CT (63%).

Only 34% of the cases received AVT before DLBCL diagnosis, 38% of whom had an SVR. The only treatment regimens used before DLBCL diagnosis were IFN-based due to the more recent availability of IFN-sparing regimens. Ten cases (13%) received AVT after DLBCL diagnosis. Six of these patients received IFN-free regimens, and all of them had SVRs (suppl table 1).

Hepatic characteristics

Almost one fourth of the cases (24%) had cirrhosis at the time of DLBCL diagnosis, 72% of whom also had portal hypertension. Only 42% of the cases who underwent liver biopsy had advanced liver disease (METAVIR stages 3-4). Among those who did not have cirrhosis, only 2% developed cirrhosis after starting CT, whereas 56% of the cases with baseline cirrhosis had decompensation of their liver disease after CT (suppl table 1). Only five cases (7%) experienced progression to hepatic failure, all of whom were cirrhotic. Causes of hepatic failure were septic shock with multiorgan failure (n=2), portal vein thrombosis (n=1), stricture of a common bile duct caused by DLBCL (n=1), and hepatotoxicity of CT (n=1).

Effect of HCV infection on DLBCL presentation

After matching the 76 cases with the 228 controls (DLBCL patients not infected with HCV), we did not find significant differences in the two groups regarding lymphoma cell of origin, transformation from a previous indolent subtype, ECOG score, IPI score, presence of B symptoms, regional lymph node involvement, use of R-CHOP as first-line CT, use of adjunct radiotherapy, or frequency of HCT (Table 1).

Although we matched the cases and controls according to stage of DLBCL, more cases than controls had extranodal (79% v 72%; p = 0.07), bone marrow (36% v 27%; p = 0.08), and upper GI (42% v 24%; p = 0.004) involvement. The cases also had a higher rate of cirrhosis at DLBCL diagnosis (24% v 2%; p < 0.0001) (Table 1). More cases were seropositive for hepatitis B virus core antibodies (HBcAb) (41% v 5%; p < 0.0001) but without any difference in detectable levels of hepatitis B virus DNA between the cases and controls (18% v 11%; p = > 0.99).

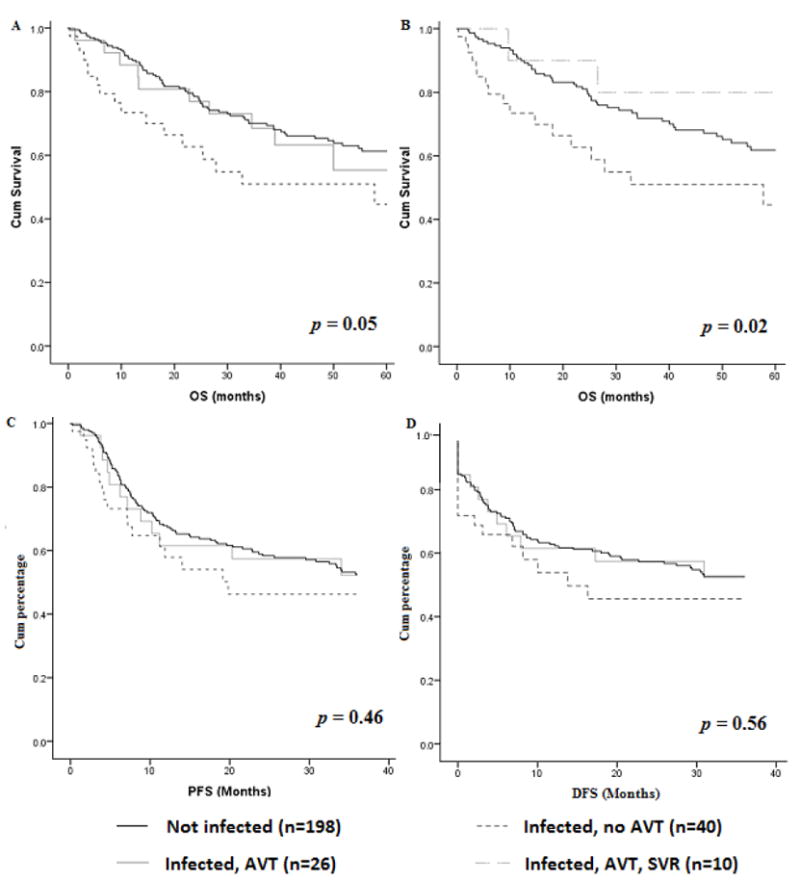

Comparison of the oncologic outcomes of three DLBCL groups

After further dividing the cases based on their AVT exposure, we analyzed three groups of patients (Figure 1): cases never given AVT (N = 40), cases given AVT before DLBCL diagnosis (N = 26), and uninfected controls (N = 198). Cases never given AVT were more likely than the controls to experience failure of first-line CT (33% v 17%; p = 0.05). Similarly, cases never given AVT exhibited a trend toward more progressive disease at the last follow-up examination compared with the controls (50% v 31%; p = 0.09) or cases treated with antivirals (50% v 27%; p = 0.06). We did not find significant differences in the rate of DLBCL relapse related to AVT exposure after first complete or partial remission (46% in the untreated group, 41% in the AVT group, and 40% in the controls; p = 0.88) (Table 2). In terms of 5-year OS, the controls had a better survival than did cases who did and did not receive AVT (65%, 61%, and 57%, respectively; p = 0.05) (Fig 2A). The cases given successful AVT (those with SVRs) before DLBCL diagnosis had a better 5-year OS rate than did the untreated cases and controls (80%, 57%, and 67%, respectively; p = 0.02) (Fig. 2B). Cases given AVT (irrespective of SVR achievement) and controls did not have significantly better 3-year PFS or DFS rates than did the untreated cases (Figures 2C and 2D).

Table 2.

Response to CT and Relapse Rates in the Three DLBCL Patient Groups

| Variable | No. of Patients (%)

|

p

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases Given AVT (A) | Cases Never Given AVT (B) | Controls (C) | All Three Groups* | (A v B)† | (B v C)* | |

| Response to first-line CT‡ | N = 26 | N = 36 | N = 198 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.05 |

| CR or PR | 22 (85) | 24 (67) | 165 (83) | |||

| Progressive disease | 4 (15) | 12 (33) | 33 (17) | |||

| Relapse after first CR, PR‡ | N = 22 | N = 24 | N = 163 | 0.88 | 0.73 | 0.66 |

| Yes | 9 (41) | 11 (46) | 66 (40) | |||

| No | 13 (59) | 13 (54) | 97 (60) | |||

| Oncologic outcome at last follow-up‡ | N = 26 | N = 36 | N = 197 | 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.09 |

| CR or PR | 19 (73) | 18 (50) | 135 (69) | |||

| Progressive disease | 7 (27) | 18 (50) | 62 (31) | |||

AVT indicates antiviral therapy; CT, chemotherapy; CR, complete response; and PR, partial response.

Generalized estimating equations and logit link function.

Pearson chi-square test.

Ten patients who received AVT after CT were not included.

Figure 2. Comparison of the 5-year OS, 3-year PFS and DFS rates in the uninfected controls, HCV-infected cases never given AVT, and HCV-infected cases given AVT before DLBCL diagnosis.

(A) Five-year OS rate. (B) Five-year OS rate including only patients achieving SVR. (C) Three-year PFS rate. (D) Three-year DFS rate.

AVT indicates antiviral therapy; DFS, disease free survival; HCV, hepatitis C virus; PFS, progression free survival; OS, overall survival; SVR, sustained virologic response.

Comparison of the characteristics of the two case groups

While comparing the cases given AVT (n=26) and cases never given AVT (n=40), both groups had similar infectious, oncologic and hepatic characteristics. Cases given AVT had a trend of higher risk IPI score (37% v 16%, p = 0.17) and METAVIR stages 3-4 on liver biopsy (56% v 20%, p = 0.1). In addition, both groups underwent similar oncologic treatment: they were given R-CHOP as first line CT (77% v 86% respectively, p = 0.27), underwent further CT after oncologic relapse (46% v 43%, p = 0.81) and R-ICE was the main regimen used as second line CT (62% v 67%, p > 0.99). (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of Cases Given AVT and Cases Never Given AVT.

| Cases given AVT No. of patients (%) |

Cases never given No. of patients (%) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of patients | N=26 | N=40 | |

| Demographics | |||

| Age, years [median (IQR)] | 58 (54 - 65) | 59 (53 - 63) | 0.89 |

| Gender, male | 21/26 (81) | 26/40 (65) | 0.16 |

| Race, white | 19/26 (73) | 25/39 (64) | 0.44 |

| DLBCL characteristics | |||

| De novo DLBCL | 21/26 (81) | 28/40 (70) | 0.32 |

| Immunohistochemistry, GCB | 11/19 (58) | 16/29 (55) | 0.85 |

| Ann Arbor, stage 3-4 | 19/25 (76) | 33/40 (83) | 0.52 |

| Extranodal involvement | 20/26 (77) | 31/40 (78) | 0.95 |

| Presence of B symptoms | 8/26 (31) | 12/37 (32) | 0.88 |

| ECOG score, 2-4 | 7/23 (30) | 10/32 (31) | 0.94 |

| IPI score, high risk | 7/19 (37) | 5/31 (16) | 0.17 |

| Bone marrow biopsy, positive | 8/26 (31) | 15/38 (40) | 0.47 |

| LDH level, U/L [median (IQR)] | 631 (522 - 943) | 657 (499 - 1075) | 0.66 |

| Infectious characteristics | |||

| HCV genotype 1 | 13/21 (62) | 27/34 (79) | 0.15 |

| HbsAg, positive | 0 | 2/40 (3) | 0.51 |

| HbcAb, positive | 12/26 (46) | 18/40 (45) | 0.92 |

| HBV DNA, detected | 2/10 (20) | 2/17 (12) | 0.61 |

| Hepatic characteristics | |||

| Cirrhosis | 5/26 (19) | 10/40 (25) | 0.58 |

| Child Pugh score A | 3/5 (60) | 4/10 (40) | 0.61 |

| Portal hypertension | 4/5 (80) | 9/10 (90) | 0.90 |

| METAVIR, stage 3-4 | 9/16 (56) | 2/10 (20) | 0.10 |

| Oncologic treatment | |||

| First line chemotherapy, RCHOP | 20/26 (77) | 25/29 (86) | 0.27 |

| HCT | 6/26 (23) | 7/38 (18) | 0.64 |

| Radiotherapy | 8/26 (31) | 11/38 (29) | 0.87 |

| Received further chemotherapy | 12/26 (46) | 16/37 (43) | 0.81 |

| Second line chemotherapy, RICE | 8/13 (62) | 10/15 (67) | >0.99 |

| Oncologic outcomes | |||

| PFS, months [median (IQR)] | 27 (7 - 45) | 10 (4 - 42) | 0.18 |

| DFS, months [median (IQR)] | 24 (3 - 41) | 6 (0 - 34) | 0.10 |

| OS, months [median (IQR)] | 39 (26 - 56) | 16 (6 - 41) | 0.02 |

AVT indicates antiviral therapy; IQR, interquartile range; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; GCB, germinal center B-cell; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; IPI, International Prognostic Index; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HbsAg, hepatitis b surface antigen; HbcAb, hepatitis b core antibody; HBV, hepatitis B virus; R-CHOP, rituximab-cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone; HCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; R-ICE, rituximab-ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide; PFS, progression free survival; DFS, disease free survival; and OS, overall survival.

Effect of HCV infection on OS

To determine the effect of HCV infection on 5-year OS of DLBCL patients, we compared cases never given any AVT (n=40) and their matched controls (n=120). The results of a 5-year multivariable cox regression analysis showed that HCV infection increased twofold the risk of death at 5 years in the cases never given AVT when compared to controls (HR, 2.31 [95% CI, 1.01-5.30]; p = 0.04) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Multivariable cox regression analyses

| Controls (N = 120) v Cases Never Given AVT (N = 40)* |

Cases Given AVT (N = 26) v Cases Never Given AVT (N = 40)† |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Parameter | HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p |

| HCV (infected without AVT v uninfected) | 2.31 | 1.01 -5.30 | 0.04 | -- | -- | -- |

| Race (white v non-white) | 1.20 | 0.52 – 2.76 | 0.65 | -- | -- | -- |

| Immunohistochemistry (GCB v non- GCB) | 1.6 | 0.78 – 3.41 | 0.18 | -- | -- | -- |

| IPI score (moderate v low risk) | 2.42 | 0.96 – 6.09 | 0.05 | 1.45 | 0.47 – 4.34 | 0.50 |

| IPI score (high v low risk) | 4.66 | 1.47 – 14.79 | 0.008 | 2.68 | 0.7 – 9.7 | 0.13 |

| Cirrhosis (yes v no) | 5.66 | 1.82 – 17.60 | 0.002 | 11.56 | 3.92 - 34.04 | <0.001 |

| AVT (yes v no) | -- | -- | -- | 0.21 | 0.06 - 0.69 | 0.01 |

AVT indicates antiviral therapy; HCV, hepatitis C virus; GCB, germinal center B-cell; and IPI, International Prognostic Index

Model analyzing the effect of active HCV infection on 5-year mortality rate after adjustment for race, immunohistochemistry, cirrhosis and IPI score (based on age, Ann Arbor stage, ECOG score, number of involved extranodal sites and LDH that are the oncologic prognostic factors of DLBCL).

Model analyzing the effect of AVT on 5-year mortality rate after adjustment for cirrhosis and IPI score (based on age, Ann Arbor stage, ECOG score, number of involved extranodal sites and LDH that are the oncologic prognostic factors of DLBCL).

Note: Confounders that changed the estimate by ≥ 10% or are clinically significant were selected. The proportional hazards assumption was tested with Schoenfeld residuals and by introducing an interaction term between the covariate and the follow-up time in the model.

Effect of AVT on OS

Compared to cases never given AVT, cases treated with AVT before DLBCL diagnosis had a significantly better OS in univariate analysis (median, 39 months; [interquartile range, 26 56] compared to 16 months, [interquartile range, 6–41], p = 0.02) (Table 3) and multivariable cox regression analysis (HR, 0.21 [95% CI, 0.06-0.69]; p = 0.01) (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the largest study to support the negative impact of chronic HCV infection on the survival of DLBCL patients. This analysis is also the first to demonstrate the oncologic benefits of AVT in HCV-infected patients who developed DLBCL, including an association with a better response to CT and improved 5-year OS rates.

In view of the potential risk of the use of rituximab in HCV-infected patients, many research studies were conducted to investigate the impact of HCV infection on the survival of DLBCL patients in the rituximab era, though with contradictory results. For instance, four previous studies24-27 concluded that HCV infection has no effect on survival of DLCBL patients and only two groups28,29 found worse OS rates in HCV-infected DLBCL patients (26 and 22 cases respectively) when compared to uninfected controls. Our findings indicate that HCV has a negative impact on the survival of DLBCL patients in the rituximab era. In addition, this study is the largest to demonstrate the significant difference in OS rates caused by HCV infection with adjustment for hepatic (cirrhosis) and oncologic risk factors (IPI score, oncologic cell of origin) for mortality.

Previous reports have studied the effect of AVT on survival in HCV-infected DLBCL patients. Michot and colleagues found a trend toward an association between AVT and improved OS rate in 17 out of 45 DLBCL patients (HR: 0.29 [0.08–1.06], p= 0.06).17 Similarly, Merli and colleagues showed improved OS in 23 out of 581 patients receiving AVT, in a univariate analysis only.16 However, both groups studied the impact of AVT given after CT and after DLBCL remission, using IFN as the mainstay of AVT. This approach was limited by selecting DLBCL survivors and responders to CT before the use of AVT. Another weakness of this approach was the confounding effect of treatment with IFN, a potent anti-lymphoma agent when combined with rituximab.20 To eliminate these confounders, we analyzed the effect of AVT on survival only when given before DLBCL diagnosis. Future analyses including HCV-infected patients treated with AVT during or after CT with agents that do not have antineoplastic activity may provide more information on the oncologic benefit of AVT.

Primary refractory DLBCL constitutes 15-20% of DLBCL cases in the rituximab era.30,31 In the present study, we showed that 33% of the DLBCL cases never given AVT had primary disease refractory to CT in contrast with 15% of the cases given AVT and 17% of the controls. This result demonstrates for the first time that DLBCL in HCV-infected patients is more refractory to CT than the uninfected patients but the use of AVT can reverse this refractoriness. This finding may be explained, at least in part, by sustained B-cell activation and B-cell apoptosis inhibition by HCV core proteins in untreated patients.32-34 On the other hand, patients with untreated HCV may have abnormal hepatic laboratory parameters that affect the dosing of CT. Abnormal hepatic function may also affect the clearance of some CT agents. Future studies including CT dose intensity analyses will clarify if the refractoriness of HCV-infected patients is attributable to differences in CT or to a sustained lymphomagenic effect of HCV.

Our study emphasizes the importance of HCV screening in cancer centers, as more than one-third of cases were newly diagnosed with active infection at the time of DLBCL diagnosis. We showed previously that 79% of patients with hematologic malignancies and only 7% of those with solid tumors were screened for HCV before CT.35 Screening more patients will lead to early detection of HCV infection with prompt initiation of AVT to prevent its hepatic and extra-hepatic manifestations.

The major strength of our study was the use of two different strategies to control confounding: matching of cases and controls according to variables influencing survival and adjustment for others, especially cirrhosis, in a multivariate analysis. By matching the cases and controls according to Ann Arbor stage and year of DLBCL diagnosis, the two groups received comparable first line CT and thus we controlled to some extent the confounding effect of CT.

Our study had some limitations. First, as in every retrospective cohort study, it had a mixture of biases, such as selection, and confounding biases, that we overcame by analyzing patients who were given AVT before DLBCL diagnosis only. Second, by studying patients given AVT before DLBCL diagnosis, we may have distorted the association between HCV infection and DLBCL. However, the discovery of persistent inflammatory changes in lymphocytes long after successful IFN-based treatment of HCV infection in addition to alteration of genes expression may explain the presence of lymphomagenesis in patients with apparently undetectable HCV RNA.11,36,37 Third, we could not analyze the effect of the newer IFN-free regimens mainly because of their recent use, small number of patients, and short duration of follow up to detect survival benefits. In addition, these new drugs were given to few of our patients after DLBCL remission, hence if included we will have an erroneous better survival, biased by an incorrect selection of patients. Finally, observed higher rates of HBV co-infection manifested by higher percentage of HBV core antibody in the HCV-infected group than in the uninfected group. This finding may have impacted the survival of the cases. However, no difference in active HBV viremia was found in both groups.

In conclusion, chronic HCV infection has a negative impact on survival of DLBCL patients. In contrast, AVT is associated with a better response to first-line CT and improves 5-year OS. Our findings support systematic screening and early administration of AVT to any HCV-infected patient. This would not only improve hepatic outcomes as previously shown,38,39 but also favorably impact patients in whom DLBCL may develop. Larger studies using new direct-acting antiviral agents are needed to validate the survival benefit of AVT in HCV-infected DLBCL patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr. Don Norwood, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, for editorial assistance.

Funding: This study was supported by the NIH/NCI under award number P30CA016672.

Abbreviations

- HCV

Hepatitis C virus

- NHLs

non-Hodgkin lymphomas

- DLBCL

diffuse large B cell lymphoma

- AVT

antiviral therapy

- CT

chemotherapy

- IFN

interferon

- ECOG

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

- IPI

International Prognostic Index

- GCB

germinal center B cell

- HCT

hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

- GI

gastrointestinal

- CR

complete response

- PR

partial response

- PD

progressive disease

- OS

overall survival

- PFS

progression-free survival

- DFS

disease-free survival

- SVR

sustained virologic response

- HRs

hazard ratios

- CIs

confidence intervals

- R-CHOP

rituximab-cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone

- R-ICE

rituximab-ifosfamide, carboplatin, etoposide

- HBcAb

hepatitis B virus core antibodies

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Contribution: J.H., P.M. and H.A.T. designed the study; H.A.T. and F.T. treated and observed the patients; R.N.M reviewed the pathology reports; J.H., P.M. and M.P.E. collected and analyzed the data; J.H., P.M., F.T., R.N.M., M.P.E., B.P.G., and H.A.T. provided expert opinion; J.H. and H.A.T. wrote the paper.

This study was presented in part in the 2016 Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, June 3-7, Chicago, IL, and was the recipient of the 2016 Conquer Cancer Foundation of American Society of Clinical Oncology Merit Award.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: H.A.T. is or has been the principal investigator for research grants from Gilead Sciences, Merck & Co., Inc., and Vertex Pharmaceuticals with all funds paid to the MD Anderson Cancer Center. H.A.T. is or has been a paid scientific advisor for the Gilead Sciences, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Merck & Co., Inc., Vertex Pharmaceuticals, Genentech, Novartis, Astellas Pharma, Pfizer Inc., and Theravance Biopharma, Inc.; the terms of these arrangements are being managed by the MD Anderson Cancer Center in accordance with its conflict of interest policies. B.P.G. has research grants from Gilead Sciences, and Merck & Co., Inc. All the other authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Simonetti RG, Camma C, Fiorello F, Cottone M, Rapicetta M, Marino L, Fiorentino G, Craxi A, Ciccaglione A, Giuseppetti R, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection as a risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis. A case-control study. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:97–102. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-116-2-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fattovich G, Giustina G, Degos F, Tremolada F, Diodati G, Almasio P, Nevens F, Solinas A, Mura D, Brouwer JT, Thomas H, Njapoum C, Casarin C, Bonetti P, Fuschi P, Basho J, Tocco A, Bhalla A, Galassini R, Noventa F, Schalm SW, Realdi G. Morbidity and mortality in compensated cirrhosis type C: a retrospective follow-up study of 384 patients. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:463–472. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.pm9024300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peveling-Oberhag J, Arcaini L, Hansmann ML, Zeuzem S. Hepatitis C-associated B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Epidemiology, molecular signature and clinical management. J Hepatol. 2013;59:169–177. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zuckerman E, Zuckerman T, Levine AM, Douer D, Gutekunst K, Mizokami M, Qian DG, Velankar M, Nathwani BN, Fong TL. Hepatitis C virus infection in patients with B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:423–428. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-6-199709150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mele A, Pulsoni A, Bianco E, Musto P, Szklo A, Sanpaolo MG, Iannitto E, De Renzo A, Martino B, Liso V, Andrizzi C, Pusterla S, Dore F, Maresca M, Rapicetta M, Marcucci F, Mandelli F, Franceschi S. Hepatitis C virus and B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas: an Italian multicenter case-control study. Blood. 2003;102:996–999. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-10-3230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silvestri F, Pipan C, Barillari G, Zaja F, Fanin R, Infanti L, Russo D, Falasca E, Botta GA, Baccarani M. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in patients with lymphoproliferative disorders. Blood. 1996;87:4296–4301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Sanjose S, Benavente Y, Vajdic CM, Engels EA, Morton LM, Bracci PM, Spinelli JJ, Zheng T, Zhang Y, Franceschi S, Talamini R, Holly EA, Grulich AE, Cerhan JR, Hartge P, Cozen W, Boffetta P, Brennan P, Maynadie M, Cocco P, Bosch R, Foretova L, Staines A, Becker N, Nieters A. Hepatitis C and non-Hodgkin lymphoma among 4784 cases and 6269 controls from the International Lymphoma Epidemiology Consortium. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:451–458. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iqbal T, Mahale P, Turturro F, Kyvernitakis A, Torres HA. Prevalence and association of hepatitis C virus infection with different types of lymphoma. Int J Cancer. 2016;138:1035–1037. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Durand T, Di Liberto G, Colman H, Cammas A, Boni S, Marcellin P, Cahour A, Vagner S, Feray C. Occult infection of peripheral B cells by hepatitis C variants which have low translational efficiency in cultured hepatocytes. Gut. 2010;59:934–942. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.192088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferri C, Monti M, La Civita L, Longombardo G, Greco F, Pasero G, Gentilini P, Bombardieri S, Zignego AL. Infection of peripheral blood mononuclear cells by hepatitis C virus in mixed cryoglobulinemia. Blood. 1993;82:3701–3704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Waldron PR, Holodniy M. Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cell Gene Expression Remains Broadly Altered Years after Successful Interferon-Based Hepatitis C Virus Treatment. J Immunol Res. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/958231. 958231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vallisa D, Bernuzzi P, Arcaini L, Sacchi S, Callea V, Marasca R, Lazzaro A, Trabacchi E, Anselmi E, Arcari AL, Moroni C, Berte R, Lazzarino M, Cavanna L. Role of anti-hepatitis C virus (HCV) treatment in HCV-related, low-grade, B-cell, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a multicenter Italian experience. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:468–473. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hermine O, Lefrere F, Bronowicki JP, Mariette X, Jondeau K, Eclache-Saudreau V, Delmas B, Valensi F, Cacoub P, Brechot C, Varet B, Troussard X. Regression of splenic lymphoma with villous lymphocytes after treatment of hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:89–94. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arcaini L, Vallisa D, Rattotti S, Ferretti VV, Ferreri AJ, Bernuzzi P, Merli M, Varettoni M, Chiappella A, Ambrosetti A, Tucci A, Rusconi C, Visco C, Spina M, Cabras G, Luminari S, Tucci M, Musto P, Ladetto M, Merli F, Stelitano C, d’Arco A, Rigacci L, Levis A, Rossi D, Spedini P, Mancuso S, Marino D, Bruno R, Baldini L, Pulsoni A. Antiviral treatment in patients with indolent B-cell lymphomas associated with HCV infection: a study of the Fondazione Italiana Linfomi. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:1404–1410. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Visco C, Finotto S. Hepatitis C virus and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: Pathogenesis, behavior and treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:11054–11061. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i32.11054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Merli M, Visco C, Spina M, Luminari S, Ferretti VV, Gotti M, Rattotti S, Fiaccadori V, Rusconi C, Targhetta C, Stelitano C, Levis A, Ambrosetti A, Rossi D, Rigacci L, D’Arco AM, Musto P, Chiappella A, Baldini L, Bonfichi M, Arcaini L. Outcome prediction of diffuse large B-cell lymphomas associated with hepatitis C virus infection: a study on behalf of the Fondazione Italiana Linfomi. Haematologica. 2014;99:489–496. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2013.094318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Michot JM, Canioni D, Driss H, Alric L, Cacoub P, Suarez F, Sibon D, Thieblemont C, Dupuis J, Terrier B, Feray C, Tilly H, Pol S, Leblond V, Settegrana C, Rabiega P, Barthe Y, Hendel-Chavez H, Nguyen-Khac F, Merle-Beral H, Berger F, Molina T, Charlotte F, Carrat F, Davi F, Hermine O, Besson C. Antiviral therapy is associated with a better survival in patients with hepatitis C virus and B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas, ANRS HC-13 lympho-C study. Am J Hematol. 2015;90:197–203. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iannitto E, Ammatuna E, Tripodo C, Marino C, Calvaruso G, Florena AM, Montalto G, Franco V. Long-lasting remission of primary hepatic lymphoma and hepatitis C virus infection achieved by the alpha-interferon treatment. Hematol J. 2004;5:530–533. doi: 10.1038/sj.thj.6200408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pellicelli AM, Marignani M, Zoli V, Romano M, Morrone A, Nosotti L, Barbaro G, Picardi A, Gentilucci UV, Remotti D, D’Ambrosio C, Furlan C, Mecenate F, Mazzoni E, Majolino I, Villani R, Andreoli A, Barbarini G. Hepatitis C virus-related B cell subtypes in non Hodgkin’s lymphoma. World J Hepatol. 2011;3:278–284. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v3.i11.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xuan C, Steward KK, Timmerman JM, Morrison SL. Targeted delivery of interferon-alpha via fusion to anti-CD20 results in potent antitumor activity against B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2010;115:2864–2871. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-250555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheson BD, Horning SJ, Coiffier B, Shipp MA, Fisher RI, Connors JM, Lister TA, Vose J, Grillo-Lopez A, Hagenbeek A, Cabanillas F, Klippensten D, Hiddemann W, Castellino R, Harris NL, Armitage JO, Carter W, Hoppe R, Canellos GP. Report of an international workshop to standardize response criteria for non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. NCI Sponsored International Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1244. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.4.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghany MG, Strader DB, Thomas DL, Seeff LB. Diagnosis, management, and treatment of hepatitis C: an update. Hepatology. 2009;49:1335–1374. doi: 10.1002/hep.22759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sarin SK, Kedarisetty CK, Abbas Z, Amarapurkar D, Bihari C, Chan AC, Chawla YK, Dokmeci AK, Garg H, Ghazinyan H, Hamid S, Kim DJ, Komolmit P, Lata S, Lee GH, Lesmana LA, Mahtab M, Maiwall R, Moreau R, Ning Q, Pamecha V, Payawal DA, Rastogi A, Rahman S, Rela M, Saraya A, Samuel D, Saraswat V, Shah S, Shiha G, Sharma BC, Sharma MK, Sharma K, Butt AS, Tan SS, Vashishtha C, Wani ZA, Yuen MF, Yokosuka O. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: consensus recommendations of the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver (APASL) 2014. Hepatol Int. 2014;8:453–471. doi: 10.1007/s12072-014-9580-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ennishi D, Maeda Y, Niitsu N, Kojima M, Izutsu K, Takizawa J, Kusumoto S, Okamoto M, Yokoyama M, Takamatsu Y, Sunami K, Miyata A, Murayama K, Sakai A, Matsumoto M, Shinagawa K, Takaki A, Matsuo K, Kinoshita T, Tanimoto M. Hepatic toxicity and prognosis in hepatitis C virus-infected patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with rituximab-containing chemotherapy regimens: a Japanese multicenter analysis. Blood. 2010;116:5119–25. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-06-289231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nishikawa H, Tsudo M, Osaki Y. Clinical outcome in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with hepatitis C virus infection in the rituximab era: a single center experience. Oncol Rep. 2012;28:835–840. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rubio J, Franco F, Sanchez A, Cantos B, Mendez M, Calvo V, Maximiano C, Perez D, Millan I, Sanchez-Beato M, Provencio M. Does the presence of hepatitis virus B and C influence the evolution of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma? Leuk Lymphoma. 2015;56:1686–1690. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2014.963576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen TT, Chiu CF, Yang TY, Lin CC, Sargeant AM, Yeh SP, Liao YM, Bai LY. Hepatitis C infection is associated with hepatic toxicity but does not compromise the survival of patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma treated with rituximab-based chemotherapy. Leuk Res. 2015;39:151–156. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2014.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Besson C, Canioni D, Lepage E, Pol S, Morel P, Lederlin P, Van Hoof A, Tilly H, Gaulard P, Coiffier B, Gisselbrecht C, Brousse N, Reyes F, Hermine O. Characteristics and outcome of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in hepatitis C virus-positive patients in LNH 93 and LNH 98 Groupe d’Etude des Lymphomes de l’Adulte programs. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:953–960. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.5016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen YY, Huang CE, Liang FW, Lu CH, Chen PT, Lee KD, Chen CC. Prognostic impact of hepatitis C virus infection in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with immunochemotherapy in the context of a novel prognostic index. Cancer Epidemiol. 2015;39:382–387. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sarkozy C, Coiffier B. Primary refractory diffuse large B cell lymphoma in the rituximab era. Curr Opin Oncol. 2015;27:377–383. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0000000000000209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hitz F, Connors JM, Gascoyne RD, Hoskins P, Moccia A, Savage KJ, Sehn LH, Shenkier T, Villa D, Klasa R. Outcome of patients with primary refractory diffuse large B cell lymphoma after R-CHOP treatment. Ann Hematol. 2015;94:1839–1843. doi: 10.1007/s00277-015-2467-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zignego AL, Giannini C, Gragnani L. HCV and Lymphoproliferation. Clinical and Developmental Immunology. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/980942. 980942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alisi A, Giannini C, Spaziani A, Caini P, Zignego AL, Balsano C. Involvement of PI3K in HCV-related lymphoproliferative disorders. J Cell Physiol. 2008;214:396–404. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.White MK, Pagano JS, Khalili K. Viruses and human cancers: a long road of discovery of molecular paradigms. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;27:463–481. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00124-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hwang JP, Suarez-Almazor ME, Torres HA, Palla SL, Huang DS, Fisch MJ, Lok AS. Hepatitis C virus screening in patients with cancer receiving chemotherapy. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:e167–174. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2013.001215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Conca P, Tarantino G. Hepatitis C virus lymphotropism and peculiar immunological phenotype: effects on natural history and antiviral therapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:2305–2308. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.2305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zignego AL, Giannini C, Monti M, Gragnani L. Hepatitis C virus lymphotropism: lessons from a decade of studies. Dig Liver Dis. 2007;39(Suppl 1):S38–45. doi: 10.1016/s1590-8658(07)80009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Torres HA, Mahale P, Blechacz B, Miller E, Kaseb A, Herlong HF, Fowler N, Jiang Y, Raad II, Kontoyiannis DP. Effect of hepatitis C virus infection in patients with cancer: addressing a neglected population. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2015;13:41–50. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2015.0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Torres HA, Mahale P. Most patients with HCV-associated lymphoma present with mild liver disease: a call to revise antiviral treatment prioritization. Liver Int. 2015;35:1661–1664. doi: 10.1111/liv.12825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.