Abstract

Background

Several inflammatory response biomarkers, including lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio (LMR), neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) have been reported to predict survival in various cancers. The aim of this study is to evaluate the clinical value of these biomarkers in patients undergoing curative resection for esophageal cancer.

Methods

The LMR, NLR and PLR were calculated in 147 consecutive patients who underwent esophagectomy between January 2006 and February 2015. We examined the prognostic significance of the LMR, NLR, and PLR in both elderly and non-elderly patients. We evaluated the cancer-specific survival (CSS), with the cause of death determined from the case notes or computerized records.

Results

Univariate analyses demonstrated that TNM pStage (p < 0.0001), tumor size (p = 0.0014), operation time (p = 0.0209), low LMR (p = 0.0008), and high PLR (p = 0.0232) were significant risk factors for poor prognosis. Meanwhile, TNM pStage (p < 0.0001) and low LMR (p = 0.0129) were found to be independently associated with poor prognosis via multivariate analysis.

In non-elderly patients, univariate analyses demonstrated that TNM pStage (p < 0.0001), tumor size (p = 0.0001), operation time (p = 0.0374), LMR (p < 0.0001), and PLR (p = 0.0189) were significantly associated with a poorer prognosis. Multivariate analysis demonstrated that TNM pStage (p = 0.001) and LMR (p = 0.0007) were independent risk factors for a poorer prognosis.

In elderly patients, univariate analysis demonstrated that that TNM pStage (p = 0.0023) was the only significant risk factor for a poor prognosis.

Conclusions

LMR was associated with cancer-specific survival (CSS) of esophageal cancer patients after curative esophagectomy. In particular, a low LMR was a significant and independent predictor of poor survival in non-elderly patients. The LMR was convenient, cost effective, and readily available, and could thus act as markers of survival in esophageal cancer.

Keywords: Esophageal cancer, Lymphocyte to monocyte ratio (LMR), Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR), Platelet lymphocyte ratio (PLR), Prognostic predictor

Background

It is now widely recognized that host-related factors, such as performance status, weight loss, smoking, and comorbidity, as well as the biological properties of individual tumors, play an important role in cancer outcomes [1]. Recent studies have shown that preoperative inflammation-based prognostic scores have a significant predictive and prognostic value in various types of cancers [2–4]. A systemic inflammatory response has been reported to be associated with tumor development, apoptosis inhibition, and angiogenesis promotion, thus resulting in tumor progression and metastasis [5, 6]. Furthermore, significant relationships between patient survival and the lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio (LMR), neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) have been documented in various cancers [7–9]. However, only a few studies have evaluated the utility of inflammation-based scores for assessing the prognosis of patients with esophageal cancer.

The aim of the present study was to evaluate whether the LMR, NLR, and PLR have prognostic values independent of conventional clinicopathological features in patients undergoing a potentially curative resection for esophageal cancer. Additionally, this study stratified patients into two age groups, elderly patients aged 70 years or older and patients aged under 70 years, because esophageal cancer occurs predominantly in elderly people and age-specific prognostic factors in patients with esophageal cancer have not yet been identified.

Methods

Patients

We retrospectively reviewed a database of medical records from 147 consecutive patients who underwent curative esophagectomy with R0 resection for histologically verified esophageal squamous cell carcinoma between January 2006 and February 2015 at Shimane University Faculty of Medicine. R0 resection was defined as a complete resection without any microscopic resection margin involvement. Video-assisted or thoracoscopic subtotal esophagectomy with three-field lymph node dissection was performed in all patients, followed by laparoscopic gastric surgery with an elevation of the gastric conduit to the neck via the posterior mediastinal or a retrosternal approach with an end-to-end anastomosis of the remnant cervical esophagus and fundus of the gastric conduit. The patients’ clinical characteristics, laboratory data, treatment, and pathological data were obtained from medical records. Preoperatively, no patients had clinical signs of infection or other systemic inflammatory conditions. Based on the age distribution of the patients, they were subdivided into two groups in this study: patients <70 years (non-elderly group) and patients ≥70 years (elderly group). We evaluated cancer-specific survival (CSS), with the cause of death determined from case notes or computerized records.

This retrospective study was approved with the ethical board of Shimane University Faculty of Medicine, and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Blood sample analysis

Data on preoperative complete blood cell (CBC) counts were retrospectively extracted from patient medical records. Only patients with available preoperative CBC count and blood differential data were included in the study. All white blood cell and differential counts were obtained within 1 week prior to surgery. CBC was measured using ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid-treated blood, and analyzed using an automated hematology analyzer XE-5000 (SYSMEX K1000 hematology analyzer; Medical Electronics, Kobe, Japan). Absolute counts of lymphocytes, monocytes, and platelets were obtained from CBC tests.

LMR, NLR, and PLR evaluations

The LMR was calculated from a routinely performed preoperative blood cell count as the absolute lymphocyte count divided by the absolute monocyte count. White blood cell count data were analyzed in the general routine laboratory of our hospital. The NLR was calculated as a simple ratio between the absolute neutrophil and absolute lymphocyte counts, as provided by the differential white blood cell count. The PLR was calculated from the differential count by dividing the absolute platelet count by the absolute lymphocyte count.

TNM stage

The pathological classification of the primary tumor, degree of lymph node involvement, and presence of organ metastasis were determined according to the TNM classification system [10].

Statistical analysis

Means and standard deviations were calculated, and differences between groups were evaluated using a Student’s t-test. Differences between categories of each clinicopathological feature were analyzed using a Chi-square (χ2) test.

We determined the optimal cut-off levels of the LMR, NLR, and PLR by applying receiver operating curve (ROC) analysis. Regarding LMR, the area under curve (AUC) was 0.69 for CSS. A value of 4.0 was chosen as the cut-off level for LMR for CSS as associated with a high sensitivity and specificity for CSS (62.5 and 71.3 %, respectively). Regarding NLR, the AUC was 0.58 for CSS. A value of 1.6 was chosen as the cut-off level for NLR for CSS as associated with a sensitivity and specificity for CSS (57.5 and 66.3 %, respectively). Regarding PLR, the AUC was 0.65 for CSS. A value of 147 was chosen as the cut-off level for PLR for CSS as associated with a high sensitivity and specificity for CSS (59.6 and 68.4 %, respectively). The patients with LMR, NLR, and PLR greater than these cutoff values were considered to have high LMR, NLR, and PLR, respectively; the remaining patients were considered to have low LMR, low NLR, and low PLR. CSS was calculated using Kaplan–Meier analysis, and differences between the groups were assessed by a log-rank test. Additionally, prognostic factors associated with decreased survival rates were determined using Cox regression analysis.

Univariate analyses were performed to determine which variables were associated with CSS. Variables with a p-value <0.05 in univariate analysis were subjected to multivariate logistic regression analysis. The potential prognostic factors for esophageal cancer were as follows: age (<70 vs. ≥70 years); sex (female vs. male); pStage (I, II vs. III); tumor size (<3 cm vs. ≥3 cm); operation time (<600 vs. ≥600 min); intraoperative blood loss (<5 00 mL vs. ≥500 mL); LMR (≥4 vs. <4); NLR (≥1.6 vs. <1.6); PLR (<147 vs. ≥147); weight loss (No vs. Yes: Weight loss was defined as more than 5 % decreasing in the body weight in the last 3 months preceding operation); and serum squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) antigen value (<1.5 vs. ≥1.5). Medical records were retrospectively reviewed to examine these factors.

All statistical analyses were performed using the statistical software JMP (version 11 for Windows; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA), and p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Relationships between LMR, NLR, PLR, and clinicopathological features in patients with esophageal cancer

The relationships between LMR, NLR, PLR, and clinicopathological features in 147 patients with esophageal cancer are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Relationships between LMR, NLR, PLR and clinicopathologic features of 147 all patients

| Characteristics | Total patients | LMR | NLR | PLR | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <4 (n = 64) |

≥4 (n = 83) |

p value | 1.6< (n = 37) |

≥1.6 (n = 110) |

p value | 147< (n = 79) |

≥147 (n = 68) |

p value | ||

| Age (years) | 65.8 ± 7.4 | 65.7 ± 8.2 | 0.934 | 65.4 ± 8.0 | 65.9 ± 7.9 | 0.72 | 66.8 ± 8.1 | 64.6 ± 7.6 | 0.097 | |

| Gender | 0.052 | 0.163 | 0.562 | |||||||

| Male | 132 | 61 | 71 | 31 | 101 | 72 | 60 | |||

| Female | 15 | 3 | 12 | 6 | 9 | 7 | 8 | |||

| WBC | 6082.2 ± 2153.2 | 5844.3 ± 1788.2 | 0.466 | 5284.1 ± 1667.3 | 6171.2 ± 1996.5 | 0.016 | 6190.9 ± 1723.0 | 5665.6 ± 2167.2 | 0.104 | |

| Neutrophil | 3944.7 ± 1804.6 | 3412.8 ± 1470.4 | 0.051 | 2491.0 ± 948.3 | 4032.3 ± 1643.7 | <0.0001 | 3509.3 ± 1300.5 | 3801.3 ± 1960.9 | 0.283 | |

| Lymphocyte | 1322.0 ± 546.4 | 1942.5 ± 584.5 | <0.0001 | 2187.6 ± 658.6 | 1499.0 ± 541.8 | <0.0001 | 2029.2 ± 586.3 | 1257.7 ± 426.2 | <0.0001 | |

| Monocyte | 546.8 ± 211.3 | 328.7 ± 111.1 | <0.0001 | 379.0 ± 161.3 | 438.7 ± 203.3 | 0.1074 | 418.2 ± 171.3 | 430.0 ± 220.2 | 0.714 | |

| Platelet | 236.6 ± 79.2 | 226.9 ± 66.2 | 0.42 | 231.0 ± 76.9 | 231.2 ± 70.7 | 0.987 | 203.5 ± 49.2 | 263.2 ± 80.9 | <0.0001 | |

| Location of tumor | 0.09 | 0.313 | 0.042 | |||||||

| Ce | 6 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 6 | |||

| Ut | 8 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 8 | 5 | 3 | |||

| Mt | 65 | 29 | 36 | 20 | 45 | 32 | 33 | |||

| Lt | 52 | 23 | 29 | 11 | 41 | 31 | 21 | |||

| Ae | 16 | 3 | 13 | 5 | 11 | 11 | 5 | |||

| Tumor size (mm) | 4.9 ± 1.9 | 3.9 ± 2.7 | 0.014 | 3.8 ± 2.8 | 4.5 ± 2.3 | 0.134 | 4.0 ± 2.5 | 4.8 ± 2.3 | 0.056 | |

| Depth of tumor | 0.0007 | 0.002 | 0.06 | |||||||

| T1a-1b | 66 | 20 | 46 | 18 | 48 | 40 | 26 | |||

| 2 | 12 | 2 | 10 | 8 | 4 | 9 | 3 | |||

| 3 | 56 | 33 | 23 | 8 | 48 | 26 | 30 | |||

| 4a-4b | 13 | 9 | 4 | 3 | 10 | 4 | 9 | |||

| Lymph node metastasis | 0.2732 | 0.1532 | 0.0639 | |||||||

| N0 | 79 | 30 | 49 | 22 | 57 | 43 | 36 | |||

| N1 | 42 | 19 | 23 | 12 | 30 | 25 | 17 | |||

| N2 | 12 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 9 | 8 | 4 | |||

| N3 | 14 | 7 | 7 | 0 | 14 | 3 | 11 | |||

| Pathological stage | 0.0002 | 0.1338 | 0.3497 | |||||||

| 1a-1b | 59 | 14 | 45 | 20 | 39 | 36 | 23 | |||

| 2a-2b | 33 | 21 | 12 | 6 | 27 | 16 | 17 | |||

| 3a-3c | 55 | 29 | 26 | 11 | 44 | 27 | 28 | |||

| Operation time (min) | 644.8 ± 162.2 | 663.5 ± 159.2 | 0.4843 | 655.9 ± 177.2 | 655.2 ± 155.0 | 0.9798 | 676.5 ± 149.0 | 630.8 ± 170.2 | 0.0845 | |

| Intraoperative blood loss (ml) | 751.8 ± 622.8 | 581.6 ± 633.4 | 0.1059 | 568.8 ± 511.1 | 684.9 ± 667.8 | 0.3359 | 598.5 ± 633.1 | 722.2 ± 629.7 | 0.2384 | |

| SCC antigen | 1.19 ± 1.06 | 1.12 ± 1.12 | 0.7208 | 1.04 ± 1.12 | 1.19 ± 1.08 | 0.7643 | 1.05 ± 0.91 | 1.27 ± 1.26 | 0.8858 | |

LMR lymphocyte to monocyte ratio, NLR neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio, PLR platelet lymphocyte ratio

Significant correlations were observed between the LMR and factors such as lymphocyte count (p < 0.0001), monocyte count (p < 0.0001), tumor size (p = 0.014), tumor depth (p = 0.0007), and TNM pStage (p = 0.0002). The NLR was significantly correlated with neutrophil count (p < 0.0001), lymphocyte count (p < 0.0001), and tumor depth (p = 0.002). Furthermore, significant correlations were observed between the PLR and lymphocyte count (p < 0.0001), platelet count (p < 0.0001), and tumor location (p = 0.042). It is notable that a low LMR was significantly correlated with more advanced TNM pStage, while the NLR and PLR showed no significant associations with TNM pStage.

Prognostic factors for CSS in overall patients with esophageal cancer

Univariate analyses demonstrated that TNM pStage (p < 0.0001), tumor size (p = 0.0014), operation time (p = 0.0209), low LMR (p = 0.0008), and high PLR (p = 0.0232) were significant risk factors for poor prognosis (Table 2).

Table 2.

Prognostic factors for cancer-specific survival in 147 patients with esophageal cancer

| Variables | Patients (n = 147) | Category or characteristics | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95 % CI | p value | HR | 95 % CI | p value | |||

| Gender | 15/132 | (female/male) | 0.942 | 0.406–2.740 | 0.9007 | |||

| Age | 46/101 | (70</≥70) | 1.427 | 0.742–2.639 | 0.2771 | |||

| pStage | 92/55 | (1,2/3) | 4.876 | 2.625–9.420 | <0.0001 | 4.19 | 2.146–8.562 | <0.0001 |

| Tumor size | 45/102 | (3</≥3) | 3.405 | 1.548–8.981 | 0.0014 | 1.433 | 0.580–4.056 | 0.4493 |

| Operation time | 99/48 | (600</≥600) | 2.041 | 1.116–3.741 | 0.0209 | 1.425 | 0.757–2.681 | 0.2699 |

| Intraoperative blood loss | 72/75 | (500</≥500) | 1.321 | 0.723–2.463 | 0.3663 | |||

| LMR | 83/64 | (≥4.0/4.0<) | 2.829 | 1.537–5.378 | 0.0008 | 2.372 | 1.198–4.840 | 0.0129 |

| NLR | 37/110 | (≥1.6/1.6<) | 1.469 | 0.753–2.734 | 0.2494 | |||

| PLR | 79/68 | (147</≥147) | 2.013 | 1.100–3.783 | 0.0232 | 1.12 | 0.611–2.404 | 0.5999 |

| SCC antigen | 109/38 | (1.5</≥1.5) | 1.3 | 0.603–2.564 | 0.4842 | |||

LMR lymphocyte to monocyte ratio, NLR neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio, PLR platelet lymphocyte ratio, SCC squamous cell carcinoma, HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval

TNM pStage (HR, 4.190; 95 % CI, 2.146–8.562; p < 0.0001) and low LMR (HR, 2.372; 95 % CI, 1.198–4.840; p = 0.0129) were found to be independently associated with poor prognosis via multivariate analysis (Table 2).

Relationships between LMR, NLR, PLR, and clinicopathological features in non-elderly patients with esophageal cancer

The relationships between LMR, NLR, PLR, and clinicopathological features in non-elderly patients (younger than 70 years) are shown in Table 3. Significant correlations were observed between the LMR and such factors as lymphocyte count (p < 0.0001), monocyte count (p < 0.0001), tumor location (p = 0.0169), tumor size (p = 0.0309), tumor depth (p = 0.0093), and TNM pStage (p = 0.0003). The NLR was significantly correlated with neutrophil count (p < 0.0001), lymphocyte count (p < 0.0001), tumor size (p = 0.0452), tumor depth (p = 0.0018), and TNM pStage (p = 0.0032). Furthermore, significant correlations were observed between the PLR and lymphocyte count (p < 0.0001) as well as platelet count (p < 0.0001).

Table 3.

Relationships between LMR, NLR, PLR and clinicopathologic features of 101 nonelderly patients

| Characteristics | Total patients | LMR | NLR | PLR | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <4 (n = 43) |

≥4 (n = 58) |

p value | 1.6< (n = 25) |

≥1.6 (n = 76) |

p value | 147< (n = 54) |

≥147 (n = 47) |

p value | ||

| Age (years) | 61.9 ± 5.2 | 61.6 ± 5.6 | 0.7778 | 61.1 ± 5.8 | 61.9 ± 5.3 | 0.7249 | 62.4 ± 5.2 | 60.8 ± 5.5 | 0.1294 | |

| Gender | 0.1283 | 0.2392 | 0.1171 | |||||||

| Male | 91 | 41 | 50 | 21 | 70 | 51 | 40 | |||

| Female | 10 | 2 | 8 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 7 | |||

| WBC | 6261.2 ± 2234.8 | 5951.4 ± 1747.8 | 0.7819 | 5654.4 ± 1725.4 | 6224.3 ± 2028.8 | 0.2101 | 6242.2 ± 1660.6 | 5900.6 ± 287.0 | 0.3863 | |

| Neutrophil | 4020.2 ± 1757.4 | 3506.3 ± 1522.4 | 0.9402 | 2645.3 ± 978.7 | 4080.3 ± 1659.8 | <0.0001 | 3481.2 ± 1252.0 | 4005.4 ± 1969.1 | 0.109 | |

| Lymphocyte | 1352.8 ± 621.1 | 1964.2 ± 584.6 | <0.0001 | 2362.7 ± 651.4 | 1487.2 ± 520.4 | <0.0001 | 2068.7 ± 601.1 | 1284.7 ± 473.7 | <0.0001 | |

| Monocyte | 574.3 ± 223.8 | 336.1 ± 109.6 | <0.0001 | 395.8 ± 163.2 | 451.3 ± 215.8 | 0.2417 | 438.1 ± 172.2 | 436.9 ± 238.6 | 0.9756 | |

| Platelet | 230.1 ± 76.1 | 233.0 ± 70.2 | 0.8422 | 215.2 ± 64.4 | 237.2 ± 74.5 | 0.9051 | 205.7 ± 47.3 | 261.7 ± 84.3 | <0.0001 | |

| Location of tumor | 0.0169 | 0.5489 | 0.1445 | |||||||

| Ce | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 | |||

| Ut | 4 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 1 | |||

| Mt | 49 | 23 | 26 | 14 | 35 | 24 | 25 | |||

| Lt | 31 | 11 | 20 | 8 | 23 | 19 | 12 | |||

| Ae | 13 | 2 | 11 | 3 | 10 | 8 | 5 | |||

| Tumor size (mm) | 4.9 ± 2.1 | 3.9 ± 2.8 | 0.0309 | 3.4 ± 2.7 | 4.6 ± 2.5 | 0.0452 | 4.0 ± 2.8 | 4.7 ± 2.2 | 0.2116 | |

| Depth of tumor | 0.0093 | 0.0018 | 0.0943 | |||||||

| T1a-1b | 44 | 12 | 32 | 13 | 31 | 29 | 15 | |||

| 2 | 6 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 2 | |||

| 3 | 40 | 23 | 17 | 5 | 35 | 17 | 23 | |||

| 4a-4b | 11 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 9 | 4 | 7 | |||

| Lymph node metastasis | 0.5691 | 0.1307 | 0.3183 | |||||||

| N0 | 56 | 22 | 34 | 18 | 38 | 32 | 24 | |||

| N1 | 28 | 13 | 15 | 6 | 22 | 16 | 12 | |||

| N2 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 3 | |||

| N3 | 11 | 4 | 7 | 0 | 11 | 3 | 8 | |||

| Pathological stage | 0.0003 | 0.0032 | 0.1024 | |||||||

| 1a-1b | 41 | 9 | 32 | 17 | 24 | 27 | 14 | |||

| 2a-2b | 20 | 15 | 5 | 1 | 19 | 8 | 12 | |||

| 3a-3c | 40 | 19 | 21 | 7 | 33 | 19 | 21 | |||

| Operation time (min) | 617.8 ± 142.7 | 666.4 ± 148.0 | 0.101 | 643.33 ± 151.1 | 646.5 ± 146.8 | 0.9246 | 680.2 ± 147.9 | 606.0 ± 137.2 | 0.107 | |

| Intraoperative blood loss (ml) | 727.9 ± 578.1 | 538.5 ± 523.1 | 0.0543 | 616.4 ± 567.6 | 620.1 ± 551.2 | 0.9772 | 563.0 ± 531.4 | 683.7 ± 574.5 | 0.2753 | |

| SCC antigen | 1.01 ± 0.76 | 1.20 ± 1.26 | 0.3828 | 1.11 ± 1.26 | 1.11 ± 1.02 | 0.9667 | 1.04 ± 0.97 | 1.20 ± 1.19 | 0.465 | |

LMR lymphocyte to monocyte ratio, NLR neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio, PLR platelet lymphocyte ratio

Prognostic factors for CSS in non-elderly patients with esophageal cancer

In non-elderly patients, univariate analyses demonstrated that TNM pStage (p < 0.0001), tumor size (p = 0.0001), operation time (p = 0.0374), LMR (p < 0.0001), and PLR (p = 0.0189) were significantly associated with a poorer prognosis. Multivariate analysis demonstrated that TNM pStage (HR, 4.009; 95 % CI, 1.731–10.162; p = 0.001) and LMR (HR, 4.553; 95 % CI, 1.856–12.516; p = 0.0007) were independent risk factors for a poorer prognosis (Table 4).

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of prognostic factors in 101 non-elderly patients with esophageal cancer

| Variables | Patients (n = 101) | Category or characteristics | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95 % CI | p value | HR | 95 % CI | p value | |||

| Gender | 10/91 | (female/male) | 0.608 | 0.233–20.78 | 0.388 | |||

| pStage | 61/40 | (1,2/3) | 5.022 | 2.321–11.715 | <0.0001 | 4.009 | 1.731–10.162 | 0.001 |

| Tumor size | 34/67 | (3</≥3) | 8.34 | 2.491–51.782 | 0.0001 | 3.115 | 0.788–20.674 | 0.1114 |

| Operation time | 67/34 | (600</≥600) | 2.219 | 1.048–4.752 | 0.0374 | 1.109 | 0.490–2.540 | 0.803 |

| Intraoperative blood loss | 49/52 | (500</≥500) | 1.53 | 0.723–3.373 | 0.2679 | |||

| LMR | 58/43 | (≥4/4<) | 5.076 | 2.259–12.909 | <0.0001 | 4.553 | 1.856–12.516 | 0.0007 |

| NLR | 25/76 | (≥1.6/1.6<) | 1.593 | 0.656–4.750 | 0.322 | |||

| PLR | 54/47 | (147</≥147) | 2.475 | 1.160–5.592 | 0.0189 | 1.163 | 0.499–2.845 | 0.5999 |

| SCC antigen | 76/25 | (1.5</≥1.5) | 0.915 | 0.305–2.244 | 0.857 | |||

LMR lymphocyte to monocyte ratio, NLR neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio, PLR platelet lymphocyte ratio, SCC squamous cell carcinoma, HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval

Relationships between LMR, NLR, PLR, and clinicopathological features in elderly patients with esophageal cancer

The relationships between LMR, NLR, PLR, and clinicopathological features in elderly patients (70 years or older) are shown in Tables 5. Significant correlations were observed between the LMR and such factors as lymphocyte count (p < 0.0001), monocyte count (p = 0.0001), and serum SCC antigen (p = 0.0342). The NLR was significantly correlated with factors such as WBC (p = 0.0146), age (p = 0.012), lymphocyte count (p < 0.0001), and neutrophil count (p = 0.0009). Furthermore, significant correlations were observed between the PLR and lymphocyte count (p < 0.0001) as well as platelet count (p = 0.0009).

Table 5.

Relationships between LMR, NLR, PLR and clinicopathologic features of 46 elderly patients

| Characteristics | Total patients | LMR | NLR | PLR | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <4 (n = 21) |

≥4 (n = 25) |

p value | 1.6< (n = 12) |

≥1.6 (n = 34) |

p value | 147< (n = 25) |

≥147 (n = 21) |

p value | ||

| Age (years) | 74.0 ± 3.8 | 75.4 ± 4.4 | 0.8781 | 74.3 ± 3.0 | 75.0 ± 4.5 | 0.6094 | 76.2 ± 4.3 | 73.1 ± 3.3 | 0.012 | |

| Gender | 0.2226 | 0.453 | 0.2226 | |||||||

| Male | 41 | 20 | 21 | 10 | 31 | 21 | 20 | |||

| Female | 5 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | |||

| WBC | 5715.7 ± 1976.4 | 5596.0 ± 1891.6 | 0.835 | 4512.5 ± 1281.2 | 6052.4 ± 1946.8 | 0.0146 | 6080.0 ± 1881.6 | 5139.5 ± 1858.8 | 0.0966 | |

| Neutrophil | 3790.0 ± 1932.6 | 3195.8 ± 1346.0 | 0.2271 | 2169.4 ± 828.4 | 3925.1 ± 1626.7 | 0.0009 | 3570.0 ± 1424.7 | 3344.5 ± 1909.4 | 0.649 | |

| Lymphocyte | 1258.9 ± 352.0 | 1892.1 ± 593.0 | <0.0001 | 1822.8 ± 528.1 | 1525.4 ± 594.0 | 0.1327 | 1943.9 ± 555.2 | 1197.2 ± 294.4 | <0.0001 | |

| Monocyte | 490.2 ± 174.3 | 311.6 ± 115.0 | 0.0001 | 344.1 ± 158.3 | 410.5 ± 171.8 | 0.2469 | 375.1 ± 164.4 | 414.7 ± 176.4 | 0.4351 | |

| Platelet | 250.0 ± 85.7 | 212.8 ± 54.3 | 0.0805 | 263.8 ± 92.6 | 217.8 ± 60.4 | 0.0563 | 198.8 ± 53.8 | 266.6 ± 74.7 | 0.0009 | |

| Location of tumor | 0.6568 | 0.1274 | 0.2753 | |||||||

| Ce | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | |||

| Ut | 4 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 2 | |||

| Mt | 16 | 6 | 10 | 6 | 10 | 8 | 8 | |||

| Lt | 21 | 12 | 9 | 3 | 18 | 12 | 9 | |||

| Ae | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 0 | |||

| Tumor size (mm) | 4.9 ± 1.5 | 3.9 ± 2.5 | 0.0987 | 4.6 ± 3.2 | 4.3 ± 1.7 | 0.6459 | 3.9 ± 1.8 | 4.9 ± 2.4 | 0.0987 | |

| Depth of tumor | 0.0716 | 0.3997 | 0.2032 | |||||||

| T1a-1b | 22 | 8 | 14 | 5 | 17 | 11 | 11 | |||

| 2 | 6 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 1 | |||

| 3 | 16 | 10 | 6 | 3 | 13 | 9 | 7 | |||

| 4a-4b | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | |||

| Lymph node metastasis | 0.1229 | 0.2441 | 0.0875 | |||||||

| N0 | 23 | 8 | 15 | 4 | 19 | 11 | 12 | |||

| N1 | 14 | 6 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 5 | |||

| N2 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 1 | |||

| N3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | |||

| Pathological stage | 0.0825 | 0.3939 | 0.8129 | |||||||

| 1a-1b | 18 | 5 | 13 | 3 | 15 | 9 | 9 | |||

| 2a-2b | 13 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 5 | |||

| 3a-3c | 15 | 10 | 5 | 4 | 11 | 8 | 7 | |||

| Operation time (min) | 700.0 ± 187.8 | 656.8 ± 185.7 | 0.4385 | 682.3 ± 227.8 | 674.5 ± 172.6 | 0.9021 | 668.5 ± 154.0 | 686.2 ± 221.6 | 0.7515 | |

| Intraoperative blood loss (ml) | 800.7 ± 718.7 | 681.5 ± 840.3 | 0.3057 | 469.8 ± 368.8 | 829.9 ± 866.8 | 0.1723 | 675.2 ± 818.5 | 808.2 ± 746.9 | 0.2854 | |

| SCC antigen | 1.56 ± 1.44 | 0.96 ± 0.68 | 0.0342 | 0.90 ± 0.80 | 1.35 ± 1.21 | 0.2379 | 1.07 ± 0.78 | 1.42 ± 1.43 | 0.2961 | |

LMR lymphocyte to monocyte ratio, NLR neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio, PLR platelet lymphocyte ratio

Prognostic factors for CSS in elderly patients with esophageal cancer

In elderly patients, univariate analysis demonstrated that that TNM pStage (p = 0.0023) was the only significant risk factor for a poor prognosis (Table 6).

Table 6.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of prognostic factors in 46 elderly patients with esophageal cancer

| Variables | Patients (n = 46) | Category or characteristics | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95 % CI | p value | HR | 95 % CI | p value | |||

| Gender | 5/41 | (female/male) | 3.114 | 0.611–56.892 | 0.201 | |||

| pStage | 31/15 | (1,2/3) | 5.22 | 1.824–16.080 | 0.0023 | 5.22 | 1.824–16.080 | 0.0023 |

| Tumor size | 11/35 | (3</≥3) | 0.976 | 0.333–3.529 | 0.9666 | |||

| Operation time | 32/14 | (600</≥600) | 1.761 | 0.615–4.929 | 0.2822 | |||

| Intraoperative blood loss | 23/23 | (500</≥500) | 0.981 | 0.349–2.820 | 0.9707 | |||

| LMR | 25/21 | (≥4/4<) | 1.118 | 0.368–3.175 | 0.837 | |||

| NLR | 12/34 | (≥1.6/1.6<) | 0.853 | 0.464–1.535 | 0.718 | |||

| PLR | 25/21 | (147</≥147) | 1.3 | 0.464–3.712 | 0.616 | |||

| SCC antigen | 33/13 | (1.5</≥1.5) | 2.261 | 0.689–6.565 | 0.167 | |||

LMR lymphocyte to monocyte ratio, NLR neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio, PLR platelet lymphocyte ratio, SCC squamous cell carcinoma, HR hazard ratio, CI, confidence interval

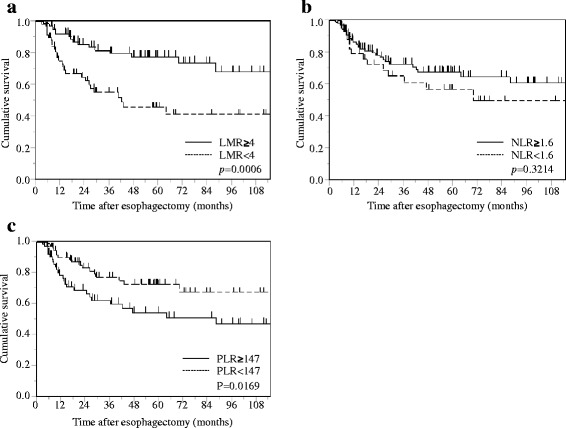

Postoperative CSS based on LMR, NLR, and PLR in all patients with esophageal cancer

Patients with a low LMR had a significantly poorer prognosis in terms of CSS than those with a high LMR (p = 0.0006). In contrast, patients with a high PLR had a significantly poorer prognosis than those with a low PLR (p = 0.0169), whereas no significant differences in CSS were observed between patients with a low or high NLR (p = 0.3214; Fig. 1a-c).

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves showing CSS after curative esophagectomy in overall patients with esophageal cancer. a LMR. b NLR. c PLR

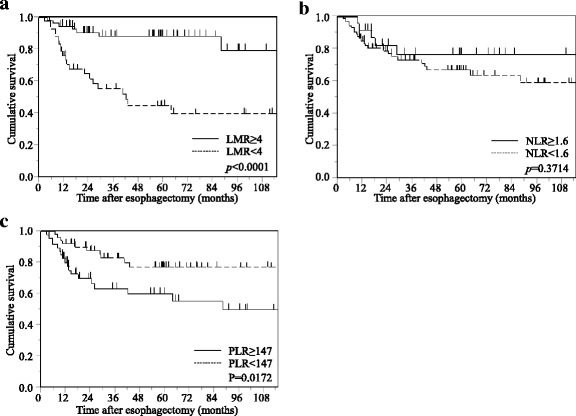

Postoperative CSS based on LMR, NLR, and PLR in non-elderly patients with esophageal cancer

Patients with a low LMR had a significantly poorer prognosis in terms of CSS than those with a high LMR (p < 0.0001). In contrast, patients with a high PLR had a significantly poorer prognosis than those with a low PLR (p = 0.0172), whereas no significant differences in CSS were observed between patients with a low or high NLR (p = 0.3714; Fig. 2a-c).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves showing CSS after curative esophagectomy in non-elderly patients with esophageal cancer. a LMR. b NLR. c PLR

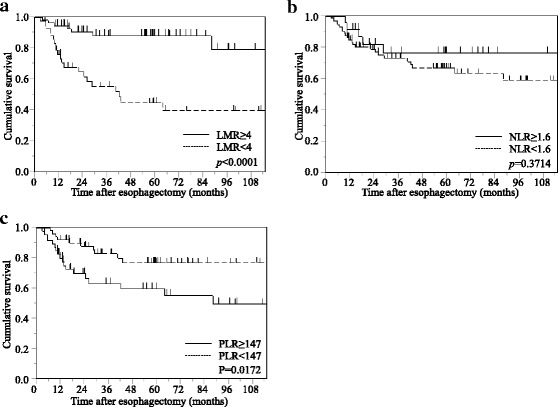

Postoperative CSS based on LMR, NLR, and PLR in elderly patients with esophageal cancer

In the elderly group, no significant differences in CSS were observed between patients with either low or high LMR (p = 0.4700), NLR (p = 0.9698), or PLR (p = 0.5386; Fig. 3a-c).

Fig. 3.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves showing CSS after curative esophagectomy in elderly patients with esophageal cancer. a LMR. b NLR. c PLR

Discussion

Pathological features, including tumor stage, nodal status, and resection margin, are considered important in determining cancer patient survival [11]. However, it is now clear that cancer survival is not solely determined by tumor pathology; indeed, recent studies have shown that preoperative inflammation-based prognostic scores can predict the overall survival of patients with various types of cancers [2–4]. In the present study, we retrospectively analyzed the clinical data of patients undergoing a potentially curative resection for esophageal cancer to determine whether the LMR, NLR, and PLR have prognostic values according to each TNM pStage. The results demonstrated that the LMR can be used as a novel predictor of postoperative CSS in patients with esophageal cancer after curative esophagectomy. Additionally, univariate analyses revealed that a low LMR was a significant risk factor for poor prognosis in stage III patients, whereas no prognostic factor was detected in patients with stage I or II cancer.

Interleukin-6 (IL-6) is a multifunctional inflammatory cytokine that triggers the proliferation and differentiation of a variety of cell types, including immune competent cells and hematopoietic cells. IL-6 induces not only neutrophil proliferation, but also the differentiation of megakaryocytes to platelets, and these events are similar to those underlying the systemic inflammatory response (SIR) [12, 13]. Theoretically, dynamic changes in the SIR resulting from tumor-host interactions are best estimated by directly measuring the serum IL-6 level. However, routine measurement of IL-6 in cancer patients in the clinical setting is expensive and inconvenient. On the other hand, the LMR, NLR, and PLR are based on blood cell components whose levels are regulated by cytokines, most notably, IL-6; these blood cell components proliferate and differentiate immediately after inflammatory cytokine release [14]. Moreover, measurement of the LMR, NLR, and PLR is easy, convenient, and cost-effective and therefore can be performed routinely.

In this study, we examined the prognostic significance of the LMR, NLR, and PLR in both elderly and non-elderly patients undergoing thoracoscopic esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. Esophageal cancer is the eighth most common cancer and the sixth most common cause of cancer deaths worldwide [15]. It occurs predominantly in elderly people, and the average age at the time of diagnosis continues to rise, with a peak incidence between 70 and 75 years of age [16]. Because age-specific prognostic factors in patients with esophageal cancer have not yet been described, we divided patients into two age groups in order to determine the age-specific prognostic values of the LMR, NLR, and PLR. The reason we chose a cut-off value of 70 years is because “elderly” is typically defined as a patient aged over 70 years in a plurality of studies on elderly patients with esophageal cancer [17–19].

Platelets are a key element linking the processes of hemostasis, inflammation, and tissue repair. Previous studies have shown that proinflammatory mediators stimulate megakaryocyte proliferation and are responsible for platelet production [20, 21]. Consequently, platelet activation causes angiogenic growth factor release as well as platelet adherence to tumor microvessels and extravasation via increased vascular permeability; this process leads to platelet activation [22, 23]. Lymphocytes can cause systemic inflammation by releasing numerous inhibitory immunologic mediators, particularly interleukin-10 and transforming growth factor-ß, which may consequently cause suppression of antitumor immunity via decreased regulatory T cell levels [6]. Accordingly, there is increasing evidence that lymphocytes are essential for antitumor immune reactions owing to several mechanisms, including the ability to enhance tumor cell apoptosis, inhibition of tumor cell proliferation, and promotion of metastasis [24]. Neutrophils are known to not only produce angiogenic cytokines, but have also been shown to generate matrix metalloproteinase-9, which induces an angiogenic state in cancer cells [25].

Based on such inflammatory responses, systemic inflammatory markers such as the LMR, NLR, and PLR have been shown to predict mortality and recurrence in a variety of cancers, but their role in esophageal cancer remains controversial [7, 20, 26].

We revealed that a low LMR in patients with esophageal cancer was significantly correlated with more advanced TNM pStage (p = 0.0002), but a low LMR was found to be independently associated with poor prognosis via multivariate analysis (HR, 2.372; p = 0.0129), as determined by Kaplan-Meier analysis and a log-rank test (p = 0.0006). A definitive explanation for our findings remains speculative. Monocytes are known to promote tumorigenesis and angiogenesis through local immune suppression and stimulation of tumor neovasculogenesis [25]. Moreover, tumor-associated macrophages developing from mononuclear cell lineages have been demonstrated to be able to inhibit cancer progression and spread of metastatic tumors [27, 28]. This could explain why an elevated monocyte count confers poor clinical outcomes in various types of cancers [29]. A poor prognosis was observed in patients with a low LMR in this study, which is reasonable because both lymphopenia and monocytosis induce immune suppression, as mentioned above. Moreover, the results of subgroup analysis revealed that the preoperative LMR was the most significant prognostic factor in non-elderly patients (HR, 4.553; p = 0.0007), as determined by Kaplan-Meier analysis and a log-rank test (p < 0.0001), but not in elderly patients. The present study may have failed to demonstrate a prognostic significance of the LMR in elderly patients because these patients were more likely to have advanced age-related conditions that cause immune suppression. Further investigations are required to elucidate the precise mechanisms that affect the prognosis of esophageal cancer patients.

Changes in platelet count and platelet function have been identified as part of a paraneoplastic syndrome in many cancers [30], and a high platelet count was found to be closely associated with TNM pStage, metastasis, as well as a high risk of recurrence in many types of cancer [31, 32]. Consequently, the PLR may act as a marker of the balance between host inflammatory and immune responses. However, to the best of our knowledge, the relationship between the PLR and esophageal cancer has not yet been described. We therefore focused on the PLR and CSS in esophageal cancer patients. Although univariate analysis demonstrated that the PLR was a significant risk factor for poorer CSS, as determined by Kaplan-Meier analysis and a log-rank test (p = 0.0169), multivariate analysis failed to confirm that the PLR was a significant predictor of CSS. Similarly, in non-elderly patients, univariate analysis demonstrated that the PLR was a significant risk factor for poorer CSS (p = 0.0172), but this significance was lost when analysis was confined to elderly patients. Recent studies have demonstrated that termed combination of platelet count and mean platelet volume is a predictor for postoperative survival in esophageal cancer patients [33]. Further studies are necessary to examine the role of these inflammatory biomarkers in various types of cancers.

The NLR has been reported to be highly promising in stratifying the outcome in large cohorts of patients with cancer [34, 35]. The relationship between the NLR and prognosis is probably complex and remains unclear. Recently, many studies have shown that a high NLR may indicate an impaired host immune response to the tumor [36]. In this study, the NLR did not affect the prognosis of esophageal cancer patients following curative resection, which may be due to the small retrospective sample size and short follow-up duration of the study. However, other components of the systemic inflammatory response, including cytokines and chemokines, have proven prognostically important in some studies [37].

There were several potential limitations that warrant consideration in our study, which include single-institution retrospective analysis, short follow-up periods, and a small sample size, especially elderly patients. Furthermore, we excluded patients who had received adjuvant chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy, which may have influenced our analysis. Thus, large, prospective, randomized controlled trials are needed to confirm these preliminary results. In addition, the amount of weight loss are well-known prognostic factors for various types of cancers. Minimal weight loss and a good performance status are considered favorable prognostic factors. Needless to say significant weight loss may impact bone marrow function as well as the patient’s ability to mount a host-tumor response. But we could not reveal that weight loss were proven to be independent prognostic factors in esophageal cancer, because our study is retrospective analysis, and data about the weight loss are insufficient.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that the LMR and PLR were associated with CSS of esophageal cancer patients after curative esophagectomy. Moreover, the results of subgroup analysis revealed that the preoperative LMR and PLR were the most significant prognostic factors in non-elderly patients, as determined by Kaplan-Meier analyses and log-rank tests. In particular, a low LMR was a significant and independent predictor of poor survival. In non-elderly patients, a low LMR was also an independent risk factor for a poorer prognosis. The LMR and PLR are convenient, cost effective, and readily available as a part of routine complete blood counts, and could thus act as markers of survival in this malignancy.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.

Authors’ contributions

NH was the lead author, and conceived this study. TM, DK, YM, and SI collected data, performed analysis, and drafted the manuscript. YT reviewed paper and technique of surgery. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This retrospective study was approved with the ethical board of Shimane University Faculty of Medicine, and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Abbreviations

- AUC

Area under curve

- CBC

Complete blood cell

- CSS

Cancer-specific survival

- LMR

Lymphocyte to monocyte ratio

- NLR

Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio

- PLR

Platelet lymphocyte ratio

- ROC

Receiver operating curve

- SCC

Squamous cell carcinoma

Contributor Information

Noriyuki Hirahara, Phone: +81-853-20-2232, Email: norinorihirahara@yahoo.co.jp.

Takeshi Matsubara, Email: nanadai@med.shimane-u.ac.jp.

Yoko Mizota, Email: sebastan@live.jp.

Shuichi Ishibashi, Email: shuichi@med.shimane-u.ac.jp.

Yoshitsugu Tajima, Email: ytajima@med.shimane-u.ac.jp.

References

- 1.Roxburgh CS, McMillan DC. Role of systemic inflammatory response in predicting survival in patients with primary operable cancer. Future Oncol. 2010;6:149–163. doi: 10.2217/fon.09.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Porrata LF, Ristow K, Colgan JP, Habermann TM, Witzig TE, Inwards DJ, Ansell SM, Micallef IN, Johnston PB, Nowakowski GS, Thompson C, Markovic SN. Peripheral blood lymphocyte/monocyte ratio at diagnosis and survival in classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Haematologica. 2012;97:262–269. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.050138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Szkandera J, Gerger A, Liegl-Atzwanger B, Absenger G, Stotz M, Friesenbichler J, Trajanoski S, Stojakovic T, Eberhard K, Leithner A, Pichler M. The lymphocyte/monocyte ratio predicts poor clinical outcome and improves the predictive accuracy in patients with soft tissue sarcomas. Int J Cancer. 2014;135:362–370. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hirahara N, Matsubara T, Hayashi H, Takai K, Fujii Y, Yajima Y. Impact of inflammation-based prognostic score on survival after curative thoracoscopic esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. Euro J Surg Oncol. 2015;41:1308–1315. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2015.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dunn GP, Old LJ, Schreiber RD. The immunobiology of cancer immunosurveillance and immunoediting. Immunity. 2004;21:137–148. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoffmann TK, Dworacki G, Tsukihiro T, Meidenbauer N, Gooding W, Johnson JT, Whiteside TL. Spontaneous apoptosis of circulating T lymphocytes in patients with head and neck cancer and its clinical importance. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:2553–2562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deng Q, He B, Liu X, Yue J, Ying H, Pan Y, Sun H, Chen J, Wang F, Gao T, Zhang L, Wang S. Prognostic value of pre-operative inflammatory response biomarkers in gastric cancer patients and the construction of a predictive model. J Transl Med. 2015;13:66. doi: 10.1186/s12967-015-0409-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li ZM, Huang JJ, Xia Y, Sun J, Huang Y, Wang Y, Zhu YJ, Li YJ, Zhao W, Wei WX, Lin TY, Huang HQ, Jiang WQ. Blood lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio identifies high-risk patients in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP. PLoS One. 2012;7:e41658. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neofytou K, Smyth EC, Giakoustidis A, Khan AZ, Williams R, Cunningham D, Mudan S. The preoperative lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio is prognostic of clinical outcomes for patients with liver-only colorectal metastases in the neoadjuvant setting. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:4353–4362. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4481-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sobin LH, Gospodarowicz MK, Wittekind C. TNM classification of malignant tumors. 7. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu YP, Ma L, Wang SJ, Chen YN, Wu GX, Han M, Wang XL. Prognostic value of lymph node metastases and lymph node ratio in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2010;36:155–159. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Imai T, Koike K, Kubo T, Kikuchi T, Amano Y, Takagi M, Okumura N, Nakahata T. Interleukin-6 supports human megakaryocytic proliferation and differentiation in vitro. Blood. 1991;78:1969–1974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruscetti FW. Hematologic effects of interleukin-1 and interleukin-6. Curr Opin Hematol. 1994;1:210–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ohsugi Y. Recent advances in immunopathophysiology of interleukin-6: an innovative therapeutic drug, tocilizumab (recombinant humanized anti-human interleukin-6 receptor antibody), unveils the mysterious etiology of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Biol Pharm Bull. 2007;30:2001–2006. doi: 10.1248/bpb.30.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamamoto M, Weber JM, Karl RC, Meredith KL. Minimally invasive surgery for esophageal cancer: review of the literature and institutional experience. Cancer Control. 2013;20:130–137. doi: 10.1177/107327481302000206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma JY, Wu Z, Wang Y, Zhao YF, Liu LX, Kou YL, Zhou QH. Clinicopathologic characteristics of esophagectomy for esophageal carcinoma in elderly patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:1296–1299. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i8.1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poon RT, Law SY, Chu KM, Branicki FJ, Wong J. Esophagectomy for carcinoma of the esophagus in the elderly: results of current surgical management. Ann Surg. 1998;227:357–364. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199803000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sabel MS, Smith JL, Nava HR, Mollen K, Douglass HO, Gibbs JF. Esophageal resection for carcinoma in patients older than 70 years. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:210–214. doi: 10.1007/BF02557376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Asher V, Lee J, Innamaa A, Bali A. Preoperative platelet lymphocyte ratio as an independent prognostic marker in ovarian cancer. Clin Transl Oncol. 2011;13:499–503. doi: 10.1007/s12094-011-0687-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cooper ZA, Frederick DT, Juneja VR, Sullivan RJ, Lawrence DP, Piris A, Sharpe AH, Fisher DE, Flaherty KT, Wargo JA. BRAF inhibition is associated with increased clonality in tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. Oncoimmunology 2013;2:e26615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Bergers G, Brekken R, McMahon G, Vu TH, Itoh T, Tamaki K, Tanzawa K, Thorpe P, Itohara S, Werb Z, Hanahan D. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 triggers the angiogenic switch during carcinogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:737–744. doi: 10.1038/35036374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kono SA, Heasley LE, Doebele RC, Camidge DR. Adding to the mix: fibroblast growth factor and platelet-derived growth factor receptor pathways as targets in non-small cell lung cancer. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2012;12:107–123. doi: 10.2174/156800912799095144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fridman WH, Pagès F, Sautès-Fridman C, Galon J. The immune contexture in human tumours: impact on clinical outcome. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:298–306. doi: 10.1038/nrc3245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koh YW, Kang HJ, Park C, Yoon DH, Kim S, Suh C, Go H, Kim JE, Kim CW, Huh J. The ratio of the absolute lymphocyte count to the absolute monocyte count is associated with prognosis in Hodgkin’s lymphoma: correlation with tumor-associated macrophages. Oncologist. 2012;17:871–880. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ying HQ, Deng QW, He BS, Pan YQ, Wang F, Sun HL, Chen J, Liu X, Wang SK. The prognostic value of preoperative NLR, d-NLR, PLR and LMR for predicting clinical outcome in surgical colorectal cancer patients. Med Oncol. 2014;31:305. doi: 10.1007/s12032-014-0305-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Condeelis J, Pollard JW. Macrophages: obligate partners for tumor cell migration, invasion, and metastasis. Cell. 2006;124:263–266. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pollard JW. Tumour-educated macrophages promote tumour progression and metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:71–78. doi: 10.1038/nrc1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Donskov F, von der Maase H. Impact of immune parameters on long-term survival in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1997–2005. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.9594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stone RL, Nick AM, McNeish IA, Balkwill F, Han HD, Bottsford-Miller J, Rupairmoole R, Armaiz-Pena GN, Pecot CV, Coward J, Deavers MT, Vasquez HG, Urbauer D, Landen CN, Hu W, Gershenson H, Matsuo K, Shahzad MM, King ER, Tekedereli I, Ozpolat B, Ahn EH, Bond VK, Wang R, Drew AF, Gushiken F, Lamkin D, Collins K, DeGeest K, Lutgendorf SK, Chiu W, Lopez-Berestein G, Afshar-Kharghan V, Sood AK. Paraneoplastic thrombocytosis in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:610–618. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li FX, Wei LJ, Zhang H, Li SX, Liu JT. Signifcance of thrombocytosis in clinicopathologic characteristics of prognosis of gastric cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:6511–6517. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.16.6511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Unal D, Eroglu C, Kurtul N, Oguz A, Tasdemir A. Are neutrophil/lymphocyte and platelrt/lymphocyte rates in patients with non-small cell lung cancer associated with treatment response and prognosis? Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:5237–5242. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2013.14.9.5237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zang F, Chen C, Wang P, Hu X, Gao Y, He J. Combination of platelet count and mean platelet volume (COP-MPV) predicts postoperative prognosis in both resectable early and advanced stage esophageal squamous cell cancer patients. Tumor Biol. doi:10.1007/s13277-015-4774-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Proctor MJ, Morrison DS, Talwar D, Balmer SM, Fletcher CD, O’Reilly DS, Foulis AK, Horgan PG, McMillan DC. A comparison of inflammation-based prognostic scores in patients with cancer. A Glasgow Inflammation Outcome Study. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:2633–2641. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Proctor MJ, McMillan DC, Morrison DS, Fletcher CD, Horgan PG, Clarke SJ. A derived neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio predicts survival in patients with cancer. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:695–699. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walsh SR, Cook EJ, Goulder F, Justin TA, Keeling NJ. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic factor in colorectal cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2005;91:181–184. doi: 10.1002/jso.20329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Proctor MJ, Horgan PG, Talwar D, Fletcher CD, Morrison DS, McMillan DC. Optimization of the systemic inflammation-based Glasgow prognostic score: a Glasgow Inflammation Outcome Study. Cancer. 2013;119:2325–2332. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.