Abstract

Background:

Traditional cigarette advertising has existed in the US for over 200 years. Studies suggest that advertising has an impact on the initiation and maintenance of smoking behaviors. In recent years, electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) emerged on the market as an alternative to the traditional tobacco cigarette. The purpose of this study was to describe advertisements in popular US magazines marketed to women for cigarettes and e-cigarettes.

Methods:

This study involved analyzing 99 issues of 14 popular US magazines marketed to women.

Results:

Compared to advertisements for traditional cigarettes, advertisements for e-cigarettes were more often found in magazines geared toward the 31–40-year-old audience (76.5% vs. 53.1%, P = 0.011) whereas traditional cigarette advertisements were nearly equally distributed among women 31–40 and ≥40 years. More than three-quarters of the e-cigarette advertisements presented in magazines aimed at the higher median income households compared to a balanced distribution by income for traditional cigarettes (P = 0.033).

Conclusions:

Future studies should focus on specific marketing tactics used to promote e-cigarette use as this product increases in popularity, especially among young women smokers.

Keywords: Advertising, cigarette, electronic cigarette, magazines, women

INTRODUCTION

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 250 million women worldwide smoke daily.[1] The prevalence of female smokers has been increasing annually, with overall prevalence estimated to increase to 25% in 2025.[2] The WHO suggests that among the reasons for maintaining this level of women who smoke is the fact that cigarettes are promoted as “sexual allure.”[1]

Traditional cigarette advertising has existed in the US for over 200 years.[3] Studies suggest that advertising has an impact on the initiation and maintenance of smoking behaviors.[4] In recent years, electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) emerged on the market as an alternative to the traditional tobacco cigarette. This device is battery-operated and has a similar appearance to the traditional cigarette.[5] The e-cigarette involves heating a liquid, usually containing nicotine, and converts this liquid into vapor.[5] The inhalation and release of this vapor through the mouth are commonly referred to as “vaping.”[5] There is no tobacco inhalation involved in smoking e-cigarettes as there is with tobacco cigarettes.[5]

Despite it being a relatively new phenomenon, the use of e-cigarettes has quickly gained popularity.[6] While the safety of e-cigarettes is being studied, marketing tactics include highlighting the unsubstantiated claim that e-cigarettes are a safer product.[7] The purpose of this study was to describe advertisements in popular US magazines marketed to women for cigarettes and e-cigarettes.

METHODS

Study design

This study involved analyzing 99 issues of 14 popular US magazines marketed to women: Allure, Cosmopolitan, Cosmopolitan for Latinas, Ebony, Elle, Essence, Girl's Life, Glamour, Jet, Latina, Marie Claire, Seventeen, Teen Vogue, Vogue. All issues were from January 2014 to August 2014, and 12 were seasonal issues (constituting more than 1 month). These magazines were selected as they fit the genre of focusing on beauty and fashion, as well as their wide-ranging reach and high level of readership.

Characteristics of the readership of each magazine were obtained from online media kits containing annual readership statistics and demographics, including median age and median household income, and are described in detail elsewhere.[8] Median age was grouped as ≤21, 22–30, 31–40, and ≥40 years to correspond with standardized age groupings for young adolescent, young adult, adult, and middle-aged adult, respectively. Using the national median for annual household income, median household income of the readership was dichotomized at or below and greater than the national median of $51,939. Three magazines targeted to Black women (Ebony, Essence, Jet) and two magazines targeted to Latina women (Cosmopolitan Latina, Latina) were coded as “marketed to a Black or Latina audience.”

Study instruments and variables assessment

Using a coding sheet adapted from the previous studies of magazine analysis,[8] the characteristics of advertisements in this sample of magazines were gathered. Magazines were purchased and advertisements were enumerated and categorized based on the product or service highlighted. The inclusion criteria for advertisements in this sample were all paid advertisements that were permanent parts of the magazine. Any product that was featured in a photo or highlighted as a favorite item was not included in the sample unless it was clearly a paid advertisement. Front covers were not included as advertisements, but back covers were. When advertisements related to cigarettes and e-cigarettes were identified, a further content analysis was conducted. The presence of warnings in the cigarette advertisement was assessed. Each advertisement was reviewed for: (1) Partying, (2) fun with friends, (3) being “cool,” (4) enjoyment, (5) happiness, and (6) having a free spirit in addition to the presence of models. The appearance of models was limited to healthy or unhealthy, and this was defined in the following way: Healthy was defined as appearing to be vigorous and free of disease. A sample of 10% of the magazines was recoded to establish intra-rater reliability as measured by Cohen's kappa. Intra-rater reliability was found to be 0.96 (range 0.89–1.00).

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis included deriving descriptive statistics. Analyses were performed using Statistics for Windows Version 22.0 Armonk, NY (version 22). Associations between magazine and advertisement and type of cigarette advertisement (traditional cigarette vs. e-cigarette) were determined using Chi-square analysis. The Institutional Review Boards at William Paterson University and Lehman College do not review studies that do not include human subjects.

RESULTS

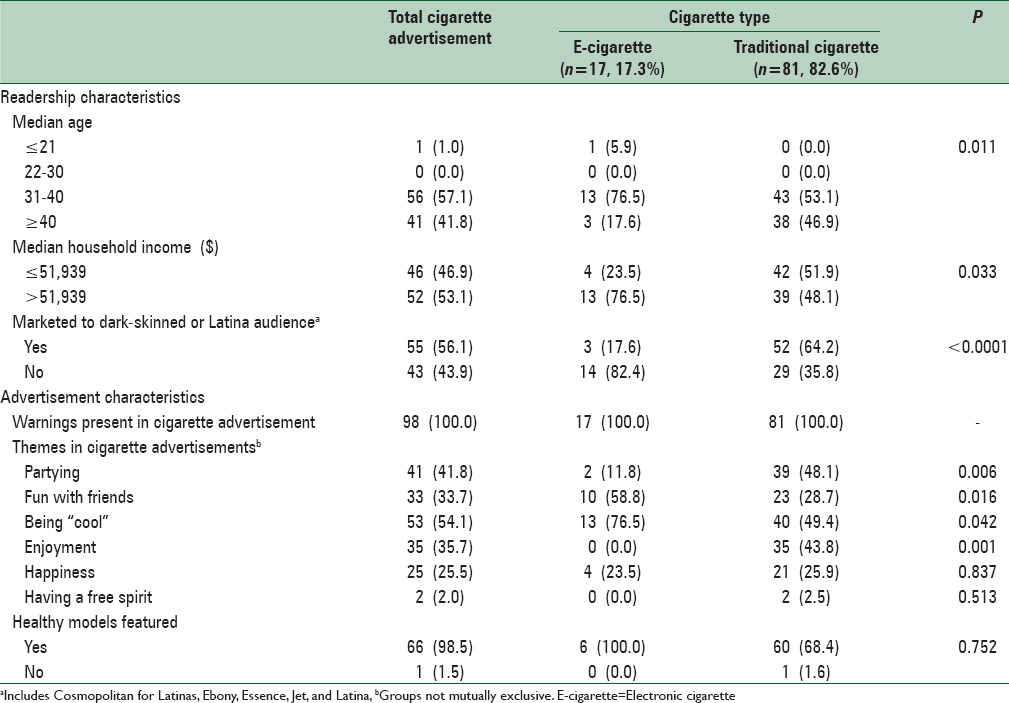

The combined readership of the magazines included in this sample was 78,598,357. A total of 98 advertisements for cigarettes were found, and of these, 17 (17.3%) were for e-cigarettes [Table 1]. The majority of cigarette advertisements (57.1%) was found in magazines whose readership was 31–40 years of age and had a median household income greater than the national average (53.1%). More than half of the cigarette advertisements were found in magazines targeting dark-skinned or Latina audiences. Warnings were present in all cigarette advertisements and the most common theme in the cigarette advertisements was “being cool” (54.1%), followed by “partying” (41.8%). Nearly every cigarette advertisement that featured models (98.5%) presented images of healthy individuals.

Table 1.

Characteristics of magazine readership and cigarette advertisements by type of cigarette (n=98)

Compared to advertisements for traditional cigarettes, advertisements for e-cigarettes were more often found in magazines geared toward the 31–40-year-old audience (76.5% vs. 53.1%, P = 0.011) whereas traditional cigarette advertisements were nearly equally distributed among women 31–40 and ≥40 years [Table 1]. More than three-quarters of the e-cigarette advertisements presented in magazines aimed at the higher median income households compared to a balanced distribution by income for traditional cigarettes (P = 0.033). Themes of the cigarette advertisements also differed by the type of cigarette featured with “being cool” (76.5%) and “fun with friends” (58.8%) predominating in the e-cigarette advertisements compared to “partying” (48.1%), “being cool” (49.4%), and “enjoyment” (43.8%) for traditional cigarettes (P < 0.0001).

DISCUSSION

This study is noteworthy for several reasons. Of particular interest is that only e-cigarette advertisement was found in the youngest age group (≤21). Magazines with this youngest median readership age contained no advertisements for traditional cigarettes. According to the American Lung Association, the overwhelming majority of adults who smoke initiated smoking at age 21 or younger.[9] A study by the United States Department of Health and Human Services indicated that in 2008, 58.8% of new cigarette smokers were under the age of 18 at initiation.[10] A Cochrane review concluded that longitudinal studies are consistent in indicating that exposure to advertising and promotional tactics for tobacco products increases the chances that adolescents will initiate smoking.[11]

The results indicated that these advertisements convey a delusional message that smoking can be healthy, fun, and enjoyable. One study of advertisements for tobacco appearing in print magazines found that themes related to eliciting an emotional response were most common in conventional cigarette advertising while themes related to using factual information were most common in e-cigarette advertising.[12] The difference in frequency of the specified themes between an e-cigarette and traditional cigarette advertisements suggests a targeting to different audiences. E-cigarette advertisements, which were found in magazines with a lower median readership age, portrayed fun with friends and being “cool,” which has been determined to be important to this younger group, especially among women.[13] E-cigarette advertisements were found in magazines with a younger, wealthier, and less ethnic audience.

Research has proven that the tobacco industry has employed marketing strategies specifically to entice women of lower socioeconomic status.[14] More advertisements for traditional cigarettes than e-cigarettes were found in magazines with median readership household income below the national average. Advertisements featuring traditional cigarettes showed more themes of partying, enjoyment, and having a free spirit. The minimum median readership age for these advertisements was 32 years. Traditional cigarette advertisements were found in magazines with and older, financially diverse, and more ethnic audience.

CONCLUSIONS

The limitations of this study include the cross-sectional design and relatively small sample size. Continuing research could be enhanced by analyzing more issues of each magazine. Despite these limitations, these magazines have a collective readership of over 78 million. Given this expansive reach and the complex messages contained in these advertisements, there is an opportunity to use similar marketing tactics for the purpose of being a nonsmoker in mainstream women's magazines. Advertising of conventional cigarettes in women's magazines has been prevalent for decades[15] and suggests a tactical approach to recruiting new smokers which was engineered strategically,[16] yet there is a paucity of research on this topic from a public health standpoint. With 96 advertisements and 99 magazines, we found an average of 1 advertisement per magazine for either e-cigarettes or traditional cigarettes (mostly traditional). Although there is not an overabundance of advertisements for these products, their presence and influence cannot be ignored. Advertising of e-cigarettes in women's magazines is low at this point. This is a field for future research as spending for e-cigarette advertising has tripled from 2011 ($6.4 million) to 2012 ($18.3 million).[17] Future studies should focus on specific marketing tactics used to promote e-cigarette use as this product increases in popularity, especially among young women smokers.[18]

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

A preliminary version of this data was presented at the Annual Health Disparities Conference at Teachers College, Columbia University in March 2015.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Female Smoking. [Last accessed 2016 Jul 27]. Available from: http://www.who.int/tobacco/en/atlas6.pdf .

- 2.Mackay J, Amos A. Women and tobacco Respirology. 2003;8:123–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1843.2003.00464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pritcher L. Emergence of Advertising in America. 1850-1920. [Last accessed 2016 Jul 27]. Available from: http://www.library.duke.edu/rubenstein/scriptorium/eaa/tobacco.html .

- 4.Botvin GJ, Goldberg CJ, Botvin EM, Dusenbury L. Smoking behavior of adolescents exposed to cigarette advertising. Public Health Rep. 1993;108:217–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Institute on Drug Abuse. Drug Facts: Electronic Cigarettes (e-Cigarettes) [[Last updated on 2016 May] [Last accessed on 2015 Aug 11]]. Available from: http://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/electronic-cigarettes-e-cigarettes .

- 6.Etter JF, Bullen C. Electronic cigarette: Users profile, utilization, satisfaction and perceived efficacy. Addiction. 2011;106:2017–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.United States Food and Drug Administration. News and Events-electronic Cigarettes (e-cigarettes) Silver Spring, Maryland: US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration; 2014. [Last updated on 2015 Jul 07]. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/PublicHealthFocus/ucm172906.htm . [Google Scholar]

- 8.Basch CH, Mongiovi J, Hillyer GC, Fullwood MD, Ethan D, Hammond R. An Advertisement and Article Analysis of Skin Products and Topics in Popular Women's Magazines: Implications for Skin Cancer Prevention. Health Promot Perspect. 2015;5:261–8. doi: 10.15171/hpp.2015.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Lung Association. Smoking. [Last accessed 2016 Jul 27]. Available from: http://www.lung.org/stop-smoking/about-smoking/health-effects/smoking.html .

- 10.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2008 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. [Last accessed 2016 Jul 27]. Available from: http://www.oas.samhsa.gov/nsduh/2k8nsduh/2k8Results.cfm#5.10 .

- 11.Lovato C, Watts A, Stead LF. Impact of tobacco advertising and promotion on increasing adolescent smoking behaviours. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;10:CD003439. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003439.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Banerjee S, Shuk E, Greene K, Ostroff J. Content analysis of trends in print magazine tobacco advertisements. Tob Regul Sci. 2015;1:103–120. doi: 10.18001/TRS.1.2.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gendall P, Hoek J, Thomson G, Edwards R, Pene G, Gifford H, et al. Young adults’ interpretations of tobacco brands: Implications for tobacco control. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13:911–8. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown-Johnson CG, England LJ, Glantz SA, Ling PM. Tobacco industry marketing to low socioeconomic status women in the U.S.A. Tob Control. 2014;23:e139–46. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Highlights: Marketing Cigarettes to Women. [Last updated on 2015 July 37]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/sgr/2001/highlights/marketing/

- 16.Albright CL, Altman DG, Slater MD, Maccoby N. Cigarette advertisements in magazines: Evidence for a differential focus on women's and youth magazines. Health Educ Q. 1988;15:225–33. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim AE, Arnold KY, Makarenko O. E-cigarette advertising expenditures in the U.S 2011-2012. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46:409–12. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brandt AM. Recruiting women smokers: The engineering of consent. J Am Med Womens Assoc. 1996;51:63–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]