Abstract

Background:

The incidence of recurrent tinea infections after oral terbinafine therapy is on the rise.

Aim:

This study aims to identify the appearance of incomplete cure and relapse after 2-week oral terbinafine therapy in tinea corporis and/or tinea cruris.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 100 consecutive patients clinically and mycologically diagnosed to have tinea corporis and/or tinea cruris were included in the study. The enrolled patients were administered oral terbinafine 250 mg once daily for 2 weeks. All clinically cured patients were then followed up for 12 weeks to look for any relapse/cure.

Results:

The common dermatophytes grown on culture were Trichophyton rubrum and Trichophyton tonsurans in 55% and 20% patients, respectively. At the end of 2-week oral terbinafine therapy, 30% patients showed a persistent disease on clinical examination while 35% patients showed a persistent positive fungal culture (persisters) at this time. These culture positive patients included all the clinically positive cases. Rest of the patients (65/100) demonstrated both clinical and mycological cure at this time (cured). Over the 12-week follow-up, clinical relapse was seen in 22 more patients (relapse) among those who had shown clinical and mycological cure at the end of terbinafine therapy. Thus, only 43% patients could achieve a long-term clinical and mycological cure after 2 weeks of oral terbinafine treatment. Majority of the relapses (16/22) were seen after 8 weeks of completion of treatment. There was no statistically significant difference in the body surface area involvement or the causative organism involved between the cured, persister, or relapse groups.

Conclusions:

Incomplete mycological cure as well as relapse is very common after standard (2-week) terbinafine therapy in our patients of tinea cruris/corporis.

Keywords: Dermatophytosis, terbinafine resistance, tinea infections

Introduction

What was known?

Terbinafine is considered to have good potency against tinea, but resistance to terbinafine in dermatophytosis has been reported previously.

Superficial mycosis is a major skin disease affecting more than 20–25% of world population.[1] It is an infection caused by various fungal species of Trichophyton, Epidermophyton, and Microsporum genera, together known as dermatophytes belonging to order onygenales. Various oral antifungals have shown efficacy against dermatophyte infections. Terbinafine was added to this list of antifungals in the early 1990s and has since then shown good efficacy in widespread tinea infections. It is the only orally available allylamine antifungal. With a favorable mycological and pharmacokinetic profile, terbinafine is considered to be a first-line drug for the treatment of tinea corporis and cruris.[2] Terbinafine acts by inhibiting the enzyme squalene epoxidase in fungi. Squalene epoxidase is an enzyme responsible for synthesis of ergosterol, an important component of fungal cell membrane.[3] This ultimately results in fungal cell wall disintegration allowing terbinafine to exert its fungicidal action. The side effects include gastrointestinal side effects such as nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. In addition, skin eruptions, headaches, and vertigo have also been reported. Rare side effects include hepatotoxicity and blood dyscrasia. The drug has shown consistent efficacy against dermatophytes achieving more than 90% cure rates at a dose of 250 mg/day when administered for 2 weeks.[3]

However, recently, we have observed decreased efficacy terbinafine in patients with tinea infections. This study is aimed at documenting these cases of terbinafine therapy failure in patients of tinea corporis and/or tinea cruris. We also tried to see the correlation of this resistance with the species involved as well as the percentage of body surface area involved.

Materials and Methods

The study was carried out in Northern part of India during spring and summer season with an average humidity of 70% and an average temperature of 28°C. Patients diagnosed to have tinea corporis and/or tinea cruris on clinical examination and involving more than 1% body surface area were taken up for the study. The diagnosis was made by clinical examination followed by 10% KOH smear and culture in all the patients. Only culture positive patients were included in the study and culture negative patients were excluded from the study. Patients who had taken any treatment, had any previous history of intolerance to the drug under study, had any abnormality in the laboratory investigation or who were immune compromised, pregnant or lactating, were excluded from the study. Moreover, patients with a history of tinea infections in family, friends, or close contacts were also excluded from the study. A total of 100 patients satisfying all the inclusion criteria were included in the study. KOH smear was positive in only 69% of these patients.

Culture was performed simultaneously on Sabouraud's Dextrose Agar (SDA) medium with chloramphenicol and SDA with chloramphenicol and cycloheximide. Samples were incubated at 25°C and 30°C separately. Identification was primarily done by phenotypic method. Biochemical tests were employed wherever felt necessary.

All the enrolled patients were put on oral terbinafine 250 mg once daily for 2 weeks. No antacids or antihistamines were prescribed, and the patients were advised to take the medication at bedtime. No topical antifungals or antifungal steroid combination agents were allowed during the study. Clinical examination and fungal culture were repeated at the end of treatment period to document clinical and mycological cure, respectively. Clinical cure was taken as the absence of any visible erythema or scaling. Residual pigmentation was present in some cases but was not taken as suggestive of incomplete cure. Patients who had a persistent clinical disease on clinical examination were given alternate oral treatments and were excluded from further analysis. Cases, in whom the disease was seen to be cured clinically, were advised to go for repeat cultures from the initial involved sites only. In addition, these clinically cured patients were asked to come for follow-up every 2 weeks. These cases were thus followed for 12 weeks to look for any relapses clinically. Relapse was defined as the appearance of lesions seen clinically and confirmed on culture subsequently.

Results

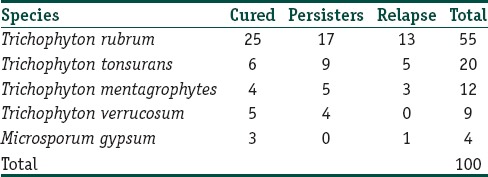

In this study, a total of 100 culture positive patients of tinea corporis and/or tinea cruris in age group of 16–62 years were included in this study. The disease was found to be more common in males, the male:female ratio being 1.63:1 (62 males and 38 females). The mean age of the patients was 29.06 ± 10.76 years. The majority of patients, i.e., 63% were in the age group 20–30 years. The most common causative organisms grown on culture were Trichophyton rubrum and Trichophyton tonsurans [Table 1].

Table 1.

The percentage distribution of various causative organisms involved

At the end of oral terbinafine therapy, only 70 cases out of 100 were clinically cured while the rest (30/100) had signs of persistent infection at the treated site (persisters). On repeat fungal culture, five cases out of the seventy clinically cured patients had a positive culture with the same organism that was grown initially. Thus, out of a total of 100 cases enrolled, only 65% could achieve both clinical and mycological cure after 2-week terbinafine therapy (cured).

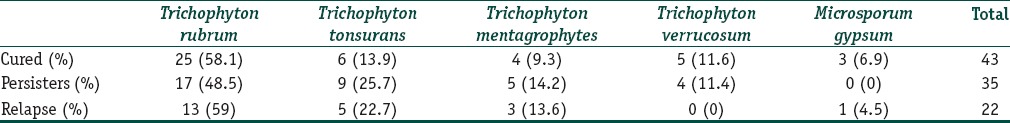

Over the 12-week follow-up, clinical relapse was seen in 22 of the 65 clinico-mycologically cured patients (relapse). Relapse was confirmed on culture as the repeat cultures grew primary pretreatment isolates in all cases. Thus, at the end of 12 weeks, there were only 43 cases out of the total 100 cases enrolled who were able to maintain a long-term clinical and mycological cure after 2 weeks of oral terbinafine treatment [Table 2].

Table 2.

Percentage of causative organisms viz-a-viz the cured, persisters and relapse groups

Majority of the relapses (16/22) were seen after 8 weeks of completion of treatment. The first patient relapsed at 3 weeks after treatment. This was followed by 3 more cases at the end of 4-week while further 2, 6, 3, and 7 patients relapsed at 6, 8, 10, and 12 weeks, respectively.

The mean percentage body surface area involvement in the cured, persistent, and relapse groups was 3.23 ± 1.2%, 3.65 ± 1.73%, and 3.182 ± 1.46%, respectively. Thus, there was no significant difference in the body surface area involvement when compared with the cured and the persistent disease groups (Mann–Whitney U-test, P: 0.3908). Furthermore, there was no significant difference between the cured and the relapse group as far as the body surface area involvement is concerned (Mann–Whitney U-test, P: 0.5952).

Discussion

Dermatophytosis, being among the most common dermatologic conditions,[4] does not spare people of any race or age.[5] According to the World Health Organization, about 20% of the world population are affected by cutaneous dermatophytic infections.[4] Dermatophytes are related fungi[6,7] capable of causing skin infection of the type known as ringworm or dermatophytosis. The ringworm species belong to three asexual genera: Microsporum, Trichophyton, and Epidermophyton, which attack the keratinized tissue and cause a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations,[8,9] of which the most predominant type of infection is tinea corporis followed by tinea cruris, tinea pedis, and onychomycosis. Tinea corporis accounts for about 70% of the dermatophytic infection.[5] In this study, which was limited to cases with tinea corporis and/or tinea cruris we found tinea cruris with corporis was the predominant type seen in 52% of cases followed by tinea corporis only (28%) and tinea cruris only (20%).

In this study, a male predominance was seen with a male:female ratio of 1.63:1. Acharya et al.[10] and Kumar et al.[11] reported male:female ratio 1.86:1 and 1.36:1, respectively, in patients with tinea infection. The predominance of males is usually thought to be a result of increased physical activity and thus increased perspiration.[12]

The patients belonged to the age group of 14–62 years, with the mean age being 29.06 ± 10.76 years. The maximum number of patients, i.e., 63% was in the age group 20–30 years. In a recent study by Surendran et al. from South India, a similar age statistics was seen.[12] Moreover, multiple authors from various parts of India have reported comparable data on age distribution.[13,14,15]

Tinea corporis and tinea cruris are most commonly caused by Trichophyton species of which T. rubrum is most common infectious agent in the world accounting for around 50% of tinea corporis cases.[16] In this study, the most common causative organism isolated after culture was T. rubrum, followed by T. tonsurans, Trichophyton mentagrophytes, Trichophyton verrucosum, and Microsporum gypseum in that order. Within the genus Trichophyton, T. rubrum is the predominant etiological agent.[17,18,19] However, a recent review has highlighted the shifting epidemiology of dermatophytosis worldwide.[20] Even one study from Northeast India reported T. tonsurans as the most common etiological agent in dermatophytosis.[21] Diagnosis of tinea corporis and/or tinea cruris is mostly done clinically. To avoid a misdiagnosis, important for successful treatment, identification of dermatophyte requires both a fungal culture on Sabouraud's Agar media and a mycological examination, consisting of a 10–15% KOH preparation, from skin scrapings. In our patients, KOH slide test was positive in 94% of cases. Culture was positive in 76% of our cases. However, much lower percentages of culture positivity in dermatophytosis have been reported by some authors.[22,23]

The treatment is based on the infection site, an area involved etiological agent, and penetration ability of the drug. Although topical antifungals may be sufficient for treatment of tinea corporis and/or tinea cruris, lesions which are widespread or fail to respond to topical therapy need systemic therapy.[24] Among the several systemic antifungal drugs used to treat dermatophytosis, terbinafine's fungicidal action, combined with its excellent pharmacokinetic properties, makes it an ideal systemic drug for the purpose.[25,26]

Terbinafine, an oral allylamine, was discovered as early as 1983. It exhibits its action on fungi by inhibiting the enzyme squalene epoxidase, thus causing an ergosterol deficiency which is important for fungal cell wall integrity.[27] Terbinafine is particularly effective against the species in Trichophyton, Microsporum, and epidermophyton genera, which in fact are the most common causative agents for tinea infections.[2] Historically griseofulvin was considered the drug of choice for tinea infections for a pretty long time. The mycological and clinical cure rates with terbinafine were not significantly different from griseofulvin.[28] However, reports of higher relapse rates with griseofulvin pushed terbinafine to the forefront in treatment of tineacorporis and cruris.[29,30] Over the years terbinafine slowly gained a first line drug status in the treatment of tinea infections particularly tineacorporis and cruris where clinical and mycological cure rates were reported to be around 90%.[3,31] Even with an intermittent pulse dose therapy cure rates of around 90% have been reported with terbinafine.[32] Even recent in vitro studies demonstrate excellent susceptibility of dermatophytes to terbinafine.[33] However, these results are in contrast to what we experienced in our patients of tinea cruris and corporis treated with oral terbinafine. We found a clinical efficacy of only 43% in our patients followed for a 12-week. Such a low clinical efficacy might be a result of the appearance of resistant strains of dermatophytes. Although resistance to terbinafine in dermatophytosis is very uncommon in clinical practice, it has been reported in clinical isolates which result from sequence variation in the gene for squalene epoxidase.[34,35] These mutations ultimately decrease the affinity of the terbinafine binding domain resulting in decreased susceptibility to the drug.[36]

The low clinical efficacy as observed in this study could not be attributed to extensive body surface area involvement as there was no statistically significant difference between the cured, persistent and the relapsed cases. Again numerous authors have reported excellent results with oral terbinafine therapy in immunocompromised individuals who interestingly have extensive area involvement.[37] Even 1 week short course oral therapy with terbinafine has shown good results in such individuals with extensive skin area involvement.[38] However, primary resistance to terbinafine in clinical T. rubrum strains has been reported long back.[39] Thus, we need to seriously consider the appearance of resistance to terbinafine in dermatophytes as an upcoming challenge in dermatological practice. Our results demand further studies to characterize the resistant strains isolated, at a molecular and biochemical level and further test the susceptibility to various antifungals so that an alternate treatment could be proposed. The main limitation of the study was the absence of calculation of MIC in cases with failed cure and relapse.

Conclusions

Incomplete cure is very common after a 2-week course of oral terbinafine therapy and recommendations about the daily dose and duration of oral therapy need to be changed and updated accordingly.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

What is new?

This article highlights the presence of resistance to terbinafine in our cases of tinea infections. This article makes the dermatologists aware of the growing resistance to terbinafine and stimulates further microbiological studies in this respect.

References

- 1.Havlickova B, Czaika VA, Friedrich M. Epidemiological trends in skin mycoses worldwide. Mycoses. 2008;51(Suppl 4):2–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newland JG, Abdel-Rahman SM. Update on terbinafine with a focus on dermatophytoses. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2009;2:49–63. doi: 10.2147/ccid.s3690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McClellan KJ, Wiseman LR, Markham A. Terbinafine. An update of its use in superficial mycoses. Drugs. 1999;58:179–202. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199958010-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta AK, Chaudhry M, Elewski B. Tinea corporis, tinea cruris, tinea nigra, and piedra. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:395–400, v. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8635(03)00031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vander Straten MR, Hossain MA, Ghannoum MA. Cutaneous infections dermatophytosis, onychomycosis, and tinea versicolor. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2003;17:87–112. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(02)00065-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marques SA, Robles AM, Tortorano AM, Tuculet MA, Negroni R, Mendes RP. Mycoses associated with AIDS in the third world. Med Mycol. 2000;38(Suppl 1):269–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Makimura K, Tamura Y, Mochizuki T, Hasegawa A, Tajiri Y, Hanazawa R, et al. Phylogenetic classification and species identification of dermatophyte strains based on DNA sequences of nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer 1 regions. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:920–4. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.4.920-924.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu D, Coloe S, Baird R, Pedersen J. Application of PCR to the identification of dermatophyte fungi. J Med Microbiol. 2000;49:493–7. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-49-6-493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Emmons CW, Bindford CH, Utz JP, Kwon-Chung KL. Dermatophytoses. Medical Mycology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger; 1977. pp. 117–67. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Acharya KM, Mukhopadhyay A, Thakur RK, Mehta T, Bhuptani N, Patel R. Itraconazole versus griseofulvine in the treatment of tinea corporis and tinea cruris. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1995;61:209–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar A, Navin B, Priyamvada S, Monika S. A comparative study of mycological efficacy of terbinafine and fluconazole in patients of tinea corporis. Int J Biomed Res. 2013;4:603–7. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Surendran K, Bhat RM, Boloor R, Nandakishore B, Sukumar D. A clinical and mycological study of dermatophytic infections. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:262–7. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.131391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sentamilselvi G, Kamalam A, Ajithadas K, Janaki C, Thambiah AS. Scenario of chronic dermatophytosis: An Indian study. Mycopathologia. 1997;140:129–35. doi: 10.1023/a:1006843418759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peerapur BV, Inamdar AC, Pushpa PV, Srikant B. Clinicomycological study of dermatophytosis in Bijapur. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2004;22:273–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh S, Beena PM. Profile of dermatophyte infections in Baroda. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2003;69:281–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foster KW, Ghannoum MA, Elewski BE. Epidemiologic surveillance of cutaneous fungal infection in the United States from 1999 to 2002. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:748–52. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(03)02117-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen BK, Friedlander SF. Tinea capitis update: A continuing conflict with an old adversary. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2001;13:331–5. doi: 10.1097/00008480-200108000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ciavaglia Mdo C, de Carvalho TU, de Souza W. Interaction of Trypanosoma cruzi with cells with altered glycosylation patterns. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;193:718–21. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coloe SV, Baird RW. Dermatophyte infections in Melbourne: Trends from 1961/64 to 1995/96. Pathology. 1999;31:395–7. doi: 10.1080/003130299104792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Borman AM, Campbell CK, Fraser M, Johnson EM. Analysis of the dermatophyte species isolated in the British Isles between 1980 and 2005 and review of worldwide dermatophyte trends over the last three decades. Med Mycol. 2007;45:131–41. doi: 10.1080/13693780601070107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grover SC, Roy PC. Clinico mycological profile of superficial mycosis in a hospital in North East India. Med J Armed Forces India. 2003;59:114–6. doi: 10.1016/S0377-1237(03)80053-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bindu V, Pavithran K. Clinico-mycological study of dermatophytosis in Calicut. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2002;68:259–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patwardhan N, Dave R. Dermatomycosis in and around Aurangabad. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 1999;42:455–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rand S. Overview: The treatment of dermatophytosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(5 Suppl):S104–12. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2000.110380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Finlay AY. Global overview of Lamisil. Br J Dermatol. 1994;130(Suppl 43):1–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1994.tb06082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Narain U, Bajaj AK, Misra K. Onychomycosis. Indian J Dermatol. 2002;47:68–75. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ryder NS. Terbinafine: Mode of action and properties of the squalene epoxidase inhibition. Br J Dermatol. 1992;126(Suppl 39):2–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1992.tb00001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cole GW, Stricklin G. A comparison of a new oral antifungal, terbinafine, with griseofulvin as therapy for tinea corporis. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:1537–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.del Palacio Hernandez A, López Gómez S, González Lastra F, Moreno Palancar P, Iglesias Díez L. A comparative double-blind study of terbinafine (Lamisil) and griseofulvin in tinea corporis and tinea cruris. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1990;15:210–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1990.tb02074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Voravutinon V. Oral treatment of tinea corporis and tinea cruris with terbinafine and griseofulvin: A randomized double blind comparative study. J Med Assoc Thai. 1993;76:388–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Farag A, Taha M, Halim S. One-week therapy with oral terbinafine in cases of tinea cruris/corporis. Br J Dermatol. 1994;131:684–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1994.tb04983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shivakumar V, Okade R, Rajkumar V, Sajitha K, Prasad SR. Intermittent pulse-dosed terbinafine in the treatment of tinea corporis and/or tinea cruris. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:121–2. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.77579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adimi P, Hashemi SJ, Mahmoudi M, Mirhendi H, Shidfar MR, Emmami M, et al. In-vitro activity of 10 antifungal agents against 320 dermatophyte strains using microdilution method in Tehran. Iran J Pharm Res. 2013;12:537–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Osborne CS, Leitner I, Favre B, Ryder NS. Amino acid substitution in Trichophyton rubrum squalene epoxidase associated with resistance to terbinafine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:2840–4. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.7.2840-2844.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Osborne CS, Leitner I, Hofbauer B, Fielding CA, Favre B, Ryder NS. Biological, biochemical, and molecular characterization of a new clinical Trichophyton rubrum isolate resistant to terbinafine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:2234–6. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01600-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martinez-Rossi NM, Peres NT, Rossi A. Antifungal resistance mechanisms in dermatophytes. Mycopathologia. 2008;166:369–83. doi: 10.1007/s11046-008-9110-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Elewski B, Smith S. The safety and efficacy of terbinafine in patients with diabetes and patients who are HIV positive. Cutis. 2001;68(1 Suppl):23–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rich P, Houpt KR, LaMarca A, Loven KH, Marbury TC, Matheson R, et al. Safety and efficacy of short-duration oral terbinafine for the treatment of tinea corporis or tinea cruris in subjects with HIV infection or diabetes. Cutis. 2001;68(1 Suppl):15–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mukherjee PK, Leidich SD, Isham N, Leitner I, Ryder NS, Ghannoum MA. Clinical Trichophyton rubrum strain exhibiting primary resistance to terbinafine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:82–6. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.1.82-86.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]