Abstract

The use of lasers in skin diseases is quite common. In contrast to other laser types, medical literature about 980 nm ultrapulsed diode laser is sparse in dermatology. Herein, we report the use of ultrapulsed diode 980 nm laser in 300 patients with vascular lesions, cysts and pseudocysts, infectious disease, and malignant tumors. This laser is a versatile tool with excellent safety and efficacy in the hands of the experienced user.

Keywords: 980 nm diode laser, benign tumors, cutaneous metastases, plantar warts, ultrapulsed laser, vascular lesions

Introduction

What was known?

Diode lasers are among the most efficient converters of electrical energy into laser light. Diode lasers can be used for coagulation, vaporization, and welding. Ultrapulsed diode lasers have been employed in dentistry, urology, gynecology, and vascular medicine. The 980 nm diode laser is under-recognized in dermatology.

Diode lasers are among the most efficient converters of electrical energy into laser light. Various tissue reactions can be induced this was such as coagulation, vaporization, or welding.[1]

The 980 nm diode laser is widely used in dentistry, urology, gynecology, and vascular medicine.[2,3,4,5] Surprisingly, the literature about 980 nm diode laser use in dermatology is very sparse. Ultrapulsed 980 nm diode laser offers some advantages. Choosing very short exposure times, heat that is generated into the tissue cannot diffuse in the adjacent parts and local overheating occurs. This will result in vaporization at temperatures >300°C. The pulse duration of microseconds will ablate tissue into fragments.[6]

Here, we wish to report on experience with an ultrapulsed 980 nm diode laser in 300 patients with various dermatologic complaints.

Patients and Methods

The ultrapulsed 980 nm diode laser Ceralas HPD (Biolitec, Jena, Germany) with focus diameter between 0.6 and 1.6 mm has been used. The maximum power of this laser is 120 W. Laser treatment was individually tailored by power, pulse duration, and pulse pause. Pretreatment by either topical or local anesthesia was used ad libitum. We prefer a eutectic mixture of local anesthetic cream (AstraZeneca, Wedel, Germany) that is a topical anesthetic cream base containing lidocaine (2.5%) and prilocaine (2.5%). Local anesthesia was done by injection of 1.0% prilocaine (Xylonest; AstraZeneca, Wedel, Germany). In other cases, no anesthesia was used. During the procedure, patients and medical staff yielded protective goggles.

We report on the first 300 patients treated by ultrapulsed 980 nm diode laser, comprising 206 females and 84 males. The age range was 6–84 years, with mean 53 ± 22 years. In the following section, we will report on treatment of various skin diseases. Since some patients were treated for more than one indication, the number of dermatoses exceeds the number of patients.

Vascular lesions

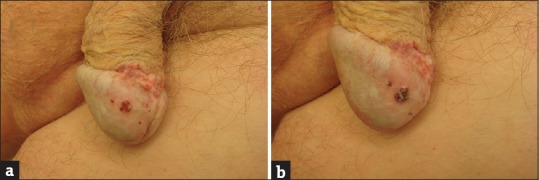

For vascular lesions, pulse duration was ≤0.01 s and pulse pause was 0.3–0.5 s. The power varied between 25 and 40 W. Cherry angioma (n = 42), venous lake of the lip (18), angiokeratoma (5), spider nevus (48), and granuloma telangiectaticum (18) responded very well to a single laser treatment. Healing was without scars [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Ultrapulsed 980 nm diode laser for multiple Fordyce angiokeratomas of the scrotum

One penile hemangioma in a child was treated in one session under general anesthesia with complete remission and without scar formation [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Angiomas of the penis. (a) Before treatment. (b) Immediately after ultrapulsed 980 nm diode laser with eschar formation

For cavernous lip angiomas (5), forced dehydration technique with short pulse pauses was employed successfully. In all patients, ≤2 laser sessions were sufficient for complete remission. There was no scar development and no texture or color change [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

(a) Lip hemangioma. (b) Immediately after ultrapulsed 980 nm diode laser application the lesion was shrinked and blanched

Capillary malformations (port wine stains; n = 9) needed a series of treatments. It was taken care not to overlap laser shots to avoid pigmentary changes and ulcerations. The time interval between laser sessions was ≥2 weeks. The aim was a significant bleaching effect [Figure 4]. However, a complete disappearance of these lesions is impossible. Again, no scars were observed. Extrafacial lesions in adults did not need anesthesia in most cases.

Figure 4.

Port wine stain on the back. (a) The scars resulted from a neodymium-yttrium aluminum garnet laser treatment several years ago. (b) During the first session with ultrapulsed 980 nm diode laser with blanching effect

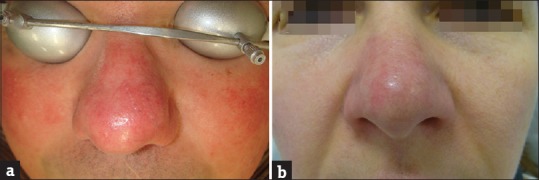

Facial telangiectasias (63) and couperose (31) can also be treated with the 980 nm diode laser. Nasal telangiectasias are particularly painful. The pulse duration should be at least three times shorter than pulse pause to avoid ulcerations. Couperose needs a series of treatments to obtain good results. This should be accompanied by sun protection and rosacea treatment with topical metronidazole [Figure 5].

Figure 5.

Severe couperose. (a) Before treatment. (b) After four sessions with ultrapulsed 980 nm diode laser with a marked reduction of cheek redness and improvement of the redness of the nose

Spider leg veins not responding to sclerosing therapy may be treated by diode laser (54). The red spiders are responding better than the blue ones. Spider leg veins may develop again after a certain period of time.

Cysts and pseudocysts

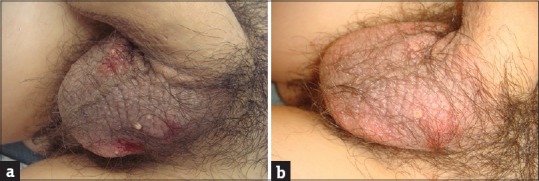

Scrotal cysts (4) and mucoid pseudocysts of fingers and toes (11) can be treated in a single session. The same is true for hidrocystoma (3), syringoma (4), and mucocele (3). Pulse duration is up to 0.1 s for larger cysts [Figure 6].

Figure 6.

Multiple scrotal cysts. (a) Before treatment. (b) Immediately after 980 nm diode laser application

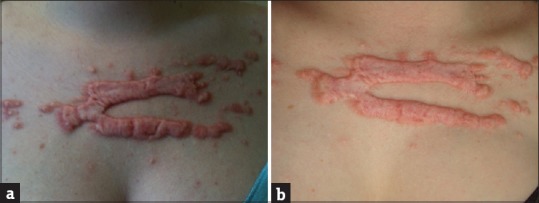

Keloids

Keloids can be treated by laser during the phase of redness (7). Here, the target of laser therapy would be sprouting vessels. Diode laser can reduce the redness. There is no effect on width and height of keloids. For this purpose, the treatment has to be combined with ablative lasers and/or intralesional corticosteroids. No induction of further growth of keloids has been observed after exposure to diode laser [Figure 7].

Figure 7.

Spontaneous keloids of the décolleté. (a) Before treatment. (b) After four sessions with ultrapulsed 980 nm diode laser with significant reduction of redness and partial decrease in height

Plantar warts

Plantar warts are particular treatment resistant (n = 95). Here, pulse duration of 0.1–0.2 s was used with an equally long pulse pause. Power was between 40 and 100 W. This leads to thermal coagulation without plum formation in contrast to erbium-yttrium aluminum garnet (YAG) or CO2 laser. Laser treatment for larger plantar warts needs general anesthesia. The relapse rate of 7.4% is less than that for erbium-YAG laser, but reinfection cannot be prevented.

Cutaneous satellite melanoma metastases

Melanomas tend to develop sometimes multiple small-sized satellite metastases. We have treated six patients with numerous lesions on the scalp or the extremities. Pulse pause was reduced to 0.1–0.2 s with pulse duration of 0.1 s. The power was adjusted to the individual needs (30–90 W). Healing was fast and scar-less.

Adverse effects

Diode laser treatment is painful. Pain depends on laser parameters, body region, and individual factors. Therefore, topical or local anesthesia may be used. Minor bleeding was noted for cavernous hemangioma and granuloma telangiectaticum.

Care has to be taken to avoid scars and hypopigmentation by adaption of power, pulse duration, and pulse pause. Protective goggles are indispensable to avoid accidental injury to the eyes.

Discussion

The 980 nm diode laser is a versatile tool in dermatology. In this paper, we reported on transcutaneous laser application only, but it has also been applied subcutaneously or intravascular to induce laser lipolysis,[7,8] to assist liposuction,[9,10] or to coagulate varicose leg veins.[11,12]

Diode lasers offer a rather deep tissue penetration. By changing laser parameters, different tissue effects can be generated. This opens a broad range of possible indications. Surprisingly, the literature on transcutaneous use of ultrapulsed 980 nm diode laser in skin disease is sparse.

Here, we report on 300 patients treated by this technique. The first important indication is vascular lesions. Benign capillary or venous lesions such as cherry angioma, venous lake of the lip, angiokeratoma, spider nevus, and granuloma telangiectaticum, and penile hemangioma respond in 100% with a complete remission after a single treatment.[13,14,15] For superficial cavernous hemangiomas, a forced dehydration technique was used successfully.[16]

Capillary malformations, facial telangiectasias, and couperose warrant several sessions to obtain satisfying results. Capillary malformations (port wine stains) are genetically heterogeneous. Nonsyndromic variants are due to mutations in GNAQ gene.[17] Capillary malformations of the face respond better than those of the trunk; smaller lesions gain a better outcome than larger ones. Since capillary malformations are composed of vessels of various calibers and depth, their treatment remains a challenge and complete response is rare.[18,19]

Spider leg veins are a common esthetic problem. Treatment of choice is sclerotherapy.[20] Those veins not responding can be treated by various lasers.[21,22] Pulsed diode lasers obtain good clinical results, but scarring is a possible adverse effect.[23] With ultrapulsed 980 nm diode laser, no scarring was observed. Red spider leg veins responded better than blue ones.

Mucocutaneous cysts and pseudocysts such as benign adnexal tumors, mucocele, and mucoid pseudocyst can easily be treated by 980 nm diode laser.[24] For larger lesions, we prefer the forced dehydration technique with longer pulse duration but shorter pulse pauses. In contrast to erbium-YAG laser, the relapse rate is lower.[25]

Keloids are benign connective tissue tumors with increased blood perfusion in the early stage. This is the target for vascular lasers in keloid treatment.[26] Good clinical results have been obtained in earlobe keloids.[27] We obtained blanching effect. For optimal outcome, treatment must combine anti-inflammatory and ablative approaches.

Plantar warts are common lesions induced by infection with human papillomavirus types. Plantar warts tend to be treatment-resistant. That may lead to large and deep penetrating plantar lesions. Ablative CO2 lasers are effective but produce plum that is potentially infectious. The erbium-YAG laser offers the advantage of noninfectious plum, but penetration is limited.[28] In an open trial, 13.5% of plantar warts did not respond in contrast to 5.9% of periungual warts.[29] The combination of erbium-YAG laser with podophyllotoxin achieved a response rate of 88.6% versus 72.5% with laser alone.[29,30] Ultrapulsed 980 nm diode laser treatment obtained a relapse rate of 7.4% within 3 months after clearance compared to 24.0% with the erbium-YAG laser.[29]

In a palliative setting, malignant tumors and metastases may be treated with laser. In dermatology, cutaneous satellite metastases of melanoma are of particular importance. Bulky metastases should be treated surgically. If patients develop multiple minute metastases, laser therapy is an option. Surprisingly, there is an absence of recurrences at treated sites which cannot completely be explained. Probably, changes in tumor microenvironment by laser therapy are responsible.[31,32] Ultrapulsed 980 nm diode laser is as effective as CO2 laser in this indication. It is patient friendly, of low-cost and simple.

Conclusion

Transcutaneous laser therapy with ultrapulsed 980 nm diode laser is a versatile tool for a large variety of skin diseases. Due to deep penetration and very short pulses, texture and color of skin are protected and nonscarring healing is possible.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

What is new?

The 980 nm ultrapulsed diode laser is a versatile tool for various disorders in dermatology. This laser type offers coagulation for vascular lesions with a low risk of scarring. It can vaporize cysts, warts, and cutaneous metastases. The 980 nm ultrapulsed laser can be used subcutaneously, intravascular, and transepidermal.

References

- 1.Gulsoy M, Dereli Z, Tabakoglu HO, Bozkulak O. Closure of skin incisions by 980-nm diode laser welding. Lasers Med Sci. 2006;21:5–10. doi: 10.1007/s10103-006-0375-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aktas AR, Celik O, Ozkan U, Cetin M, Koroglu M, Yilmaz S, et al. Comparing 1470- and 980-nm diode lasers for endovenous ablation treatments. Lasers Med Sci. 2015;30:1583–7. doi: 10.1007/s10103-015-1768-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azma E, Safavi N. Diode laser application in soft tissue oral surgery. J Lasers Med Sci. 2013;4:206–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cetinkaya M, Onem K, Rifaioglu MM, Yalcin V. 980-nm diode laser vaporization versus transurethral resection of the prostate for benign prostatic hyperplasia: Randomized controlled study. Urol J. 2015;12:2355–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qadri T, Javed F, Johannsen G, Gustafsson A. Role of diode lasers (800-980 nm) as adjuncts to scaling and root planing in the treatment of chronic periodontitis: A systematic review. Photomed Laser Surg. 2015;33:568–75. doi: 10.1089/pho.2015.3914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berlien HP, Müller GJ, editors. Applied Laser Medicine. Berlin: Springer; pp. 101–6. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valizadeh N, Jalaly NY, Zarghampour M, Barikbin B, Haghighatkhah HR. Evaluation of safety and efficacy of 980-nm diode laser-assisted lipolysis versus traditional liposuction for submental rejuvenation: A randomized clinical trial. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2016;18:41–5. doi: 10.3109/14764172.2015.1039041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leclère FM, Moreno-Moraga J, Alcolea JM, Casoli V, Mordon SR, Vogt PM, et al. Laser assisted lipolysis for neck and submental remodeling in Rohrich type I to III aging neck: A prospective study in 30 patients. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2014;16:284–9. doi: 10.3109/14764172.2014.946053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wollina U, Heinig B. Tumescent microcannular (laser-assisted) liposuction in painful lipedema. Eur J Aesthetic Med Dermatol. 2012;2:56–69. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wollina U, Goldman A, Heinig B. Microcannular tumescent liposuction in advanced lipedema and Dercum's disease. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2010;145:151–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beyazal M, Avcu S, Özen Ö, Yavuz A, Bora A, Ünal Ö. Endovenous laser ablation treatment with 980 nm diode laser for saphenous vein insufficiency: 6 months follow up results. JBR BTR. 2014;97:336–40. doi: 10.5334/jbr-btr.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murli NL, Lee TC, Beh ML. Holistic management of venous ulcers especially with endovenous laser treatment using 980 nm laser in an ethnically diverse society. Med J Malaysia. 2013;68:453–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mlacker S, Shah VV, Aldahan AS, McNamara CA, Kamath P, Nouri K. Laser and light-based treatments of venous lakes: A literature review. Lasers Med Sci. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s10103-016-1934-7. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wollina U. Treatment of genital angiokeratomas and related vascular lesions by ultrapulsed 980 nm diode laser. J Bras Laser. 2011;3:16–8. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wollina U. Scrotal angiokeratoma of Fordyce – New approach with ultrapulsed 980 nm diode laser. Kosmet Med. 2010;31:204–5. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jasper J, Camilotti RS, Pagnoncelli RM, Poli VD, da Silveira Gerzson A, Gavin Zakszeski AM. Treatment of lip hemangioma using forced dehydration with induced photocoagulation via diode laser: Report of three cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2015;119:e89–94. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frigerio A, Wright K, Wooderchak-Donahue W, Tan OT, Margraf R, Stevenson DA, et al. Genetic variants associated with port-wine stains. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0133158. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Astafyeva LG, Gade R, Schmidt WD, Ledneva GP, Wollina U, Fassler D. Laser heating of biological tissue with blood vessels: Modeling and clinical trials. Opt Spectrosc. 2006;100:789–96. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klein A, Hohenleutner U. Potential and limitations of dye laser therapy for capillary malformations. HNO. 2014;62:25–9. doi: 10.1007/s00106-013-2804-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vitale-Lewis VA. Aesthetic treatment of leg veins. Aesthet Surg J. 2008;28:573–83. doi: 10.1016/j.asj.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wollina U, Schmidt WD, Hercogova J, Fassler D. Laser therapy of spider leg veins. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2003;2:166–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-2130.2004.00087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meesters AA, Pitassi LH, Campos V, Wolkerstorfer A, Dierickx CC. Transcutaneous laser treatment of leg veins. Lasers Med Sci. 2014;29:481–92. doi: 10.1007/s10103-013-1483-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wollina U, Konrad H, Schmidt WD, Haroske G, Astafeva LG, Fassler D. Response of spider leg veins to pulsed diode laser (810 nm): A clinical, histological and remission spectroscopy study. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2003;5:154–62. doi: 10.1080/14764170310017071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wollina U. Treatment of multiple scrotal cysts with a 910-nm short-pulsed diode laser. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2012;14:159–60. doi: 10.3109/14764172.2012.687111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wollina U. Techniques in dermatologic surgery: Digital mucoid pseudocyst. Hell Dermatosurgery. 2010;7:32–5. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mamalis AD, Lev-Tov H, Nguyen DH, Jagdeo JR. Laser and light-based treatment of Keloids – A review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:689–99. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kassab AN, El Kharbotly A. Management of ear lobule keloids using 980-nm diode laser. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2012;269:419–23. doi: 10.1007/s00405-011-1632-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wollina U. Erbium-YAG laser therapy – Analysis of more than 1,200 treatments. J Glob Dermatol. 2016;3:268–72. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wollina U, Konrad H, Karamfilov T. Treatment of common warts and actinic keratoses by Er:YAG laser. J Cutan Laser Ther. 2001;3:63–6. doi: 10.1080/146288301753377852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wollina U. Er: YAG laser followed by topical podophyllotoxin for hard-to-treat palmoplantar warts. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2003;5:35–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Jarwaarde JA, Wessels R, Nieweg OE, Wouters MW, van der Hage JA. CO2 laser treatment for regional cutaneous malignant melanoma metastases. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:78–82. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.John HE, Mahaffey PJ. Laser ablation and cryotherapy of melanoma metastases. J Surg Oncol. 2014;109:296–300. doi: 10.1002/jso.23488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]