Abstract

Objective

To compare the prevalence of comorbidities, health care utilization, and costs between moderate‐to‐severe psoriasis (PsO) patients with comorbid psoriatic arthritis (PsA) and matched controls.

Methods

Adults ages 18–64 years with concomitant diagnoses of PsO and PsA (PsO+PsA) were identified in the OptumHealth Reporting and Insights claims database between January 2007 and March 2012. Moderate‐to‐severe PsO was defined based on the use of at least one systemic or phototherapy during the 12‐month study period after the index date (randomly selected date after the first PsO diagnosis). Control patients without PsO and PsA were demographically matched 1:1 with PsO+PsA patients. Multivariate regressions were employed to examine PsO/PsA‐related comorbidities, medications, health care utilization, and costs between PsO+PsA patients and controls, adjusting for demographics, index year, insurance type, and non–PsO/PsA‐related comorbidities.

Results

Among 1,230 matched pairs of PsO+PsA patients and controls, PsO+PsA patients had significantly more PsO/PsA‐related comorbidities, with the top 3 most common in both groups being hypertension (35.8% versus 23.5%), hyperlipidemia (34.6% versus 28.5%), and diabetes mellitus (15.9% versus 10.0%). Compared with controls, PsO+PsA patients had a higher number of distinct prescriptions filled (incidence rate ratio 2.3, P < 0.05); were more likely to have inpatient admissions (odds ratio [OR] 1.6), emergency room visits (OR 1.3), and outpatient visits (OR 62.7) (all P < 0.05); and incurred significantly higher total, pharmacy, and medical costs (adjusted annual cost differences per patient $23,160, $17,696, and $5,077, respectively; all P < 0.01).

Conclusion

Compared with matched PsO‐ and PsA‐free controls, moderate‐to‐severe PsO patients with comorbid PsA had higher comorbidity and health care utilization and costs.

INTRODUCTION

Psoriasis (PsO) is a chronic, inflammatory, immune‐mediated disease characterized by scaling and erythematous plaques in skin. Approximately 7.5 million individuals (2.2%) in the US have PsO 1. PsO patients commonly develop psoriatic arthritis (PsA), an inflammatory arthritis associated with pain and swelling that could lead to joint damage and long‐term disability 2. The estimated prevalence of PsA among PsO patients varies widely, from 6–42% 3, 4, 5, due to variation in study methods and the lack of widely accepted classification or diagnosis criteria 6. A majority (84%) of PsA patients have cutaneous manifestations before onset of arthritic symptoms 7. Due to the dual skin and joint involvement, patients with both PsO and PsA experience further impairment and consequently lower quality of life compared with patients with PsO alone 8.

Besides skin and joint involvement, PsO and PsA are associated with multiple systemic comorbidities, including metabolic syndrome (e.g., hyperlipidemia, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and obesity), other autoimmune diseases (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease), and lymphoma 9, 10, 11, 12, 13. Moreover, compared with the general population, patients with PsO/PsA face an elevated burden of cardiovascular diseases due to a higher prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors such as metabolic syndrome and chronic inflammation in PsO/PsA 14, 15, 16. Due to the multisystem involvement of PsO and PsA, a new terminology, psoriatic disease, has been suggested that encompasses a wide array of musculoskeletal manifestations and extraarticular features 17. In addition, the burden of physical comorbidities increases with PsO severity 18, and the presence of severe PsO or PsA increases mortality 19, 20.

PsO and PsA impose considerable economic burdens. The annual direct cost for PsO is estimated to be $5.17 billion (in 2006 dollars) in the US 21. With additional involvement in the joints, PsO patients with comorbid PsA incurred greater health care utilization and costs than patients with PsO alone. In a large claims database analysis using data from 1999 to 2004, patients with both PsO and PsA had more inpatient admissions and outpatient visits, and incurred on average $2,800 (in 2007 dollars) incremental health care costs over a 6‐month period, compared with patients with PsO alone 22.

Systemic therapies are required for more severe PsO or PsA. For decades, immunosuppressants were the primary pharmacologic treatments for moderate‐to‐severe PsO or PsA 7, 23. The advent of biologic agents in recent years has significantly changed the treatment paradigms. Biologic agents are cost effective in improving clinical outcomes, quality of life, and work productivity, compared with conventional therapies for PsO/PsA 24, 25. In addition, PsO shares similar pathophysiologic pathways with other immunologic and inflammatory diseases; therefore, biologic agents may also improve PsO/PsA‐related comorbid conditions such as cardiovascular diseases 26.

Although the burdens of PsO and PsA during the pre–biologic agents era have been studied previously 22, 27, 28, 29, a study based on more recent data is warranted to examine the economic consequences of PsO and PsA since the introduction of biologic agents. We conducted a retrospective study to compare comorbidities, health care utilization, and costs between moderate‐to‐severe PsO patients with comorbid PsA and a demographically matched cohort free of PsO and PsA. Specifically, our hypothesis was that moderate‐to‐severe PsO patients with comorbid PsA had higher PsO‐ and PsA‐related comorbidity burden and also higher economic burdens compared to the matched controls free of both conditions.

Box 1. Significance & Innovations.

Moderate‐to‐severe psoriasis (PsO) patients with comorbid psoriatic arthritis (PsA) are subject to extensive skin inflammation, joint damage, longterm disability, impaired health‐related quality of life, and increased mortality.

This study updated the current literature about the comorbidity and economic burdens among moderate‐to‐severe PsO patients with comorbid PsA using a recent large claims database.

There remains a substantial burden among moderate‐to‐severe PsO patients with comorbid PsA with the availability of biologic agents.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Data source

This retrospective study used data from the OptumHealth Reporting and Insights claims database (January 1, 2007 to March 31, 2012), which represents approximately 15.5 million privately insured individuals from 69 companies in a wide range of industries and occupations across the US. Medical (including inpatient and outpatient services) and pharmacy claims, as well as health plan enrollment data, are available for all beneficiaries (including employees, spouses, and dependents) for services provided. Medical claims capture information on inpatient and outpatient care, including the date, type, and place of service; provider type; and payment information. International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD‐9‐CM) diagnosis codes, ICD‐9‐CM procedure codes, and the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes are provided for each medical claim. Pharmacy claims files capture the National Drug Code, dispensing date, quantity of drug, number of days supplied, and payment information. Enrollment/eligibility records contain enrollment information as well as demographics (i.e., age, sex, and census region).

Sample selection

Patients in the PsO cohort had at least 2 diagnoses of PsO (ICD‐9‐CM code 696.1) on different dates between January 1, 2007 and March 31, 2012. For these patients, an index date was randomly selected from the potential index dates that met the following criteria: 1) patients had at least one PsO diagnosis before a potential index date (a calendar date after the first PsO diagnosis between January 2007 and March 2012), 2) patients were continuously enrolled for 12 months (study period) after a potential index date, and 3) patients were ages 18–64 years as of a potential index date. Patient health plan enrollment periods covered by health maintenance organizations (HMOs) were excluded due to incomplete information on health care costs in the database. Moderate‐to‐severe PsO patients were further identified, defined as patients who received at least one nontopical systemic therapy (for Generic Product Identifier [GPI] codes, see Supplementary Appendix A, available in the online version of this article at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr.22492/abstract) or phototherapy during the study period (for CPT codes, see Supplementary Appendix B, available in the online version of this article at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr.22492/abstract). Moderate‐to‐severe PsO patients who were comorbid with PsA (PsO+PsA cohort) were further selected as those with at least 2 distinct PsA diagnoses from January 1, 2007 to the end of the 12‐month study period.

Control patients were selected from the same OptumHealth database. Patients free of PsO (ICD‐9‐CM code 696.1) and PsA (ICD‐9‐CM code 696.0) over the entire claims history (January 1, 1999 to March 31, 2012) were identified as control candidates. The control candidates were assigned the same index dates as the selected moderate‐to‐severe PsO patients. Furthermore, control candidates were required to be continuously enrolled in health plans for 12 months following the index date and age 18–64 years as of the index date. Patient health plan enrollment periods covered by HMOs were excluded. Control candidates were matched to PsO+PsA patients on a 1:1 ratio using the exact matching technique based on demographic characteristics (age as of the index date, sex, and geographic region). The matching method ensured that PsO+PsA patients and controls were comparable in demographic characteristics. However, the 2 groups may be different in the comorbidity profile, which was further assessed in the analysis.

Patient characteristics and outcomes

Patient characteristics were measured as of the index date, including demographics (age, sex, and geographic region), insurance type, and calendar year of index date. Non–PsO/PsA‐related comorbidities were measured during the 12‐month study period and consisted of components of the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) that are not related to PsO/PsA, including lung disease, renal disease, liver disease, peptic ulcer disease, dementia, rheumatic disease unrelated to PsO/PsA (excluding the following diseases that are identified as PsO/PsA‐related comorbidities: rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, systemic sclerosis, and Sjögren's syndrome), hemiplegia, and acquired immune deficiency syndrome (for ICD‐9‐CM codes, see Supplementary Appendix C, available in the online version of this article at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr.22492/abstract). A modified CCI was calculated on non–PsO/PsA‐related comorbidities 30.

Study outcomes included PsO/PsA‐related comorbidities, medication use, health care utilization, and costs measured during the 12‐month study period. PsO/PsA‐related comorbidities included hyperlipidemia, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obesity, coronary heart disease, acute myocardial infarction, stroke, peripheral vascular disease, depression, anxiety, rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis, other autoimmune disorders (including alopecia areata, celiac disease, systemic sclerosis, Sjögren's syndrome, vitiligo, chronic urticaria, systemic lupus erythematosus, Addison's disease, giant cell arteritis, pulmonary fibrosis, and chronic glomerulonephritis), multiple sclerosis, skin cancer, lymphoma, and other malignancies (including cancers of the lung, pharynx, liver, pancreas, breast, vulva, penis, bladder, and kidney) 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 (for ICD‐9‐CM codes, see Supplementary Appendix D, available in the online version of this article at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr.22492/abstract).

The use of all‐cause and selected comorbidity‐related medications (including antidepressants, antidiabetic drugs, and cardiovascular drugs, identified based on GPI codes) (see Supplementary Appendix E, available in the online version of this article at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr.22492/abstract) was measured by any prescription filled and the number of distinct medications filled. All‐cause health care utilization (including inpatient visit, emergency room [ER] visit, and outpatient visit) was measured by any visit, number of visits, and length of inpatient stay. All‐cause health care costs captured the reimbursement amounts from payers to health care providers and were adjusted to 2012 US dollars using the medical care component of the consumer price index 31. Total costs, pharmacy costs, and medical costs, including inpatient, ER, outpatient, and other costs, were analyzed in the study.

Statistical analyses

All patient characteristics and outcomes were examined descriptively using means and SDs for continuous variables, and frequency counts and percentages for categorical variables. Unadjusted values were compared between the matched PsO+PsA and control cohorts using Wilcoxon's signed rank tests for continuous variables and McNemar's tests for binary variables.

Multivariate regressions were performed to assess the impact of PsO+PsA on comorbidities, medication use, health care utilization, and costs, adjusting for between‐group differences in demographics, index year, insurance type as of the index date, non–PsO/PsA‐related comorbidities, and modified CCI (based on non–PsO/PsA‐related comorbidities measured during the 12‐month study period). Binary variables (including occurrence of comorbidities, any medication use, and any medical services utilization) were analyzed with conditional logistic regression models. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were estimated. Count variables (including the number of distinct medications filled and the number of medical service visits) were analyzed with negative binomial regression models, using generalized estimating equation, to account for correlation between matched pairs. Incidence rate ratios (IRRs) and 95% CIs were estimated. To estimate the adjusted cost differences between matched cohorts, multivariate 2‐part regression models with the bootstrap resampling method were used. Specifically, the estimated cost was calculated by multiplying the probability of having a nonzero cost (first part of the model) by the predicted nonzero cost values (second part of the model). The conditional logistic regression models were evaluated for goodness of fit using the likelihood‐based pseudo R2 measure and its rescaled measure provided in SAS; the negative binomial regression models and the gamma regression models were evaluated for goodness of fit using the deviance and Pearson's chi‐square statistics provided in SAS. SAS, version 9.2 was used to perform the data analyses. The significance level was set at a 2‐tailed alpha value of 0.05.

RESULTS

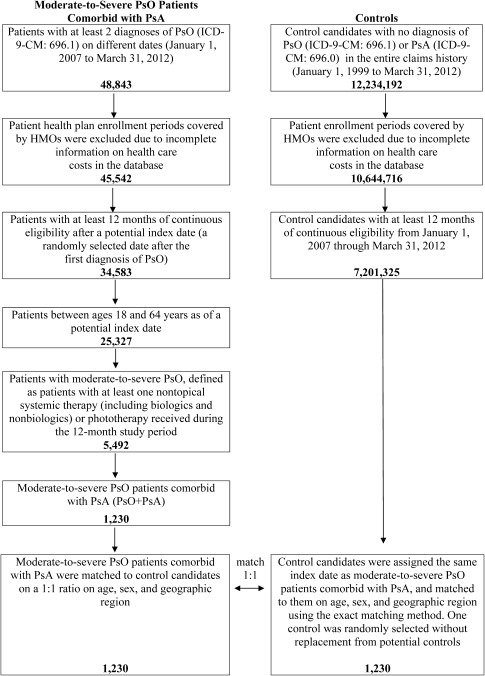

A total of 48,843 patients with at least 2 distinct diagnoses of PsO between January 1, 2007 and March 31, 2012 were identified from the database (Figure 1). Among them, 5,492 moderate‐to‐severe PsO patients met all inclusion and exclusion criteria. We further identified 1,230 moderate‐to‐severe PsO patients with comorbid PsA (PsO+PsA). Per the study design, all PsO+PsA patients had at least 2 distinct PsO diagnoses between January 1, 2007 and March 31, 2012 with at least 1 PsO diagnosis prior to the index date, as well as at least 2 distinct PsA diagnoses from January 1, 2007 to the end of the 12‐month study period. The majority (85%) of the PsO+PsA patients examined in this study had a PsA diagnosis during the pre–index period, while 15% had a PsA diagnosis only during the 12‐month study period. Approximately 12 million patients were free of PsO and PsA in the database, and 1,230 were matched to the PsO+PsA sample based on age, sex, and geographic region.

Figure 1.

Selection of the study cohorts. PsO = psoriasis; PsA = psoriatic arthritis; ICD‐9‐CM = International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification; HMOs = health maintenance organizations.

Patient characteristics

Both cohorts had a mean age of 48.5 years and 47.9% were women (Table 1). More than 30% of the sample lived in the South, followed by the Midwest and Northeast regions. Approximately two‐thirds of the matched pairs had insurance coverage from a preferred provider organization. Compared with matched controls, PsO+PsA patients had a higher mean modified CCI score (0.23 versus 0.12; P < 0.0001), and a greater proportion of them had non–PsO/PsA‐related comorbidities. Specifically, the PsO+PsA group had a significantly higher prevalence of lung disease (9.5% versus 6.1%), liver disease (3.4% versus 1.0%), and rheumatic disease unrelated to PsO/PsA (1.1% versus 0.2%) (all P < 0.05).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and non–PsO/PsA‐related comorbidities in moderate‐to‐severe PsO+PsA patients and matched controlsa

| Moderate‐to‐severe PsO+PsA patients (n = 1,230) | Controls (n = 1,230) | Unadjusted P (patients vs. controls)b | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, mean ± SD years | 48.46 ± 10.75 | 48.46 ± 10.75 | – |

| Age group, years | |||

| 18–29 | 72 (5.9) | 72 (5.9) | – |

| 30–39 | 192 (15.6) | 192 (15.6) | – |

| 40–49 | 330 (26.8) | 330 (26.8) | – |

| 50–59 | 417 (33.9) | 417 (33.9) | – |

| 60–64 | 219 (17.8) | 219 (17.8) | – |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 641 (52.1) | 641 (52.1) | – |

| Female | 589 (47.9) | 589 (47.9) | – |

| Geographic region | |||

| Northeast | 260 (21.1) | 260 (21.1) | – |

| Midwest | 302 (24.6) | 302 (24.6) | – |

| South | 410 (33.3) | 410 (33.3) | – |

| West | 156 (12.7) | 156 (12.7) | – |

| Unknown | 102 (8.3) | 102 (8.3) | – |

| Health insurance type | 0.4075 | ||

| Preferred provider organization | 817 (66.4) | 788 (64.1) | |

| Point of service | 183 (14.9) | 198 (16.1) | |

| Indemnity | 191 (15.5) | 212 (17.2) | |

| Other | 39 (3.2) | 32 (2.6) | |

| Index year | |||

| 2007 | 134 (10.9) | 134 (10.9) | – |

| 2008 | 197 (16.0) | 197 (16.0) | – |

| 2009 | 288 (23.4) | 288 (23.4) | – |

| 2010 | 428 (34.8) | 428 (34.8) | – |

| 2011 | 183 (14.9) | 183 (14.9) | – |

| Modified CCI, mean ± SDc | 0.23 ± 0.81 | 0.12 ± 0.46 | < 0.0001d |

| Non–PsO/PsA‐related comorbidities | |||

| Dementia | 1 (0.1) | 3 (0.2) | 0.6250 |

| Lung diseasee | 117 (9.5) | 75 (6.1) | 0.0015d |

| Liver disease | 42 (3.4) | 12 (1.0) | < 0.0001d |

| Renal disease | 24 (2.0) | 16 (1.3) | 0.1944 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 12 (1.0) | 4 (0.3) | 0.0768 |

| Rheumatic disease unrelated to PsO/PsAf | 14 (1.1) | 3 (0.2) | 0.0127g |

| Hemiplegia | 4 (0.3) | 2 (0.2) | 0.6875 |

| AIDS | 6 (0.5) | 2 (0.2) | 0.2891 |

Values are the number (percentage) unless indicated otherwise. Demographics were measured as of the index date; non–PsO/PsA‐related comorbidities were measured during the 12‐month study period. PsO = psoriasis; PsA = psoriatic arthritis; CCI = Charlson Comorbidity Index; AIDS = acquired immune deficiency syndrome.

Univariate comparison was made using Wilcoxon's signed rank tests for modified CCI, McNemar's tests for non–PsO/PsA‐related comorbidities (exact binomial distribution was used if the number of discordant pairs was ≤25), and chi‐square tests for health insurance type.

Calculated based on non–PsO/PsA‐related comorbidities using the methodology described by Romano et al 30.

Significance at 0.01 level.

Including cor pulmonale, pulmonary heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and asthma.

Excluding rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, systemic sclerosis, and Sjögren's syndrome.

Significance at 0.05 level.

PsO/PsA‐related comorbidities

The prevalence of most PsO/PsA‐related comorbidities assessed was higher among PsO+PsA patients than the controls during the 12‐month study period (Table 2). Results from the conditional logistic regression, controlling for insurance type, individual non–PsO/PsA‐related comorbidities, and modified CCI, also confirmed the finding that PsO+PsA patients had significantly higher odds for the majority of PsO/PsA‐related comorbidities investigated. The most common comorbidities in the PsO+PsA cohort included components of metabolic syndrome such as hypertension (35.8% versus 23.5%; adjusted OR [aOR] 1.9), hyperlipidemia (34.6% versus 28.5%; aOR 1.3), and diabetes mellitus (15.9% versus 10.0%; aOR 1.6) (all P < 0.01). However, obesity was not significantly different between cohorts (4.3% versus 3.3%; aOR 1.4). PsO+PsA patients were more likely to have coronary heart disease (6.6% versus 4.1%; aOR 1.7, P < 0.05) and depression (9.1% versus 5.0%; aOR 2.1, P < 0.0001), rheumatoid arthritis (16.6% versus 0.7%; aOR 48.8, P < 0.01), and other autoimmune diseases (3.2% versus 1.5%; aOR 2.2, P < 0.05). Although the prevalence of Crohn's disease/ulcerative colitis (1.3% versus 0.5%; aOR 1.6), cerebrovascular disease (2.4% versus 1.6%; aOR 1.5), peripheral vascular disease (2.4% versus 1.6%; aOR 1.4), all skin cancer (2.2% versus 1.3%; aOR 1.5), nonmelanoma skin cancer (2.2% versus 1.2%; aOR 1.5), and lymphoma (0.2% versus 0%) was higher among the PsO+PsA patients, the between‐group difference was not statistically significant based on the logistic regression results.

Table 2.

PsO/PsA‐related comorbidities in moderate‐to‐severe PsO+PsA patients and matched controlsa

| Moderate‐to‐severe PsO+PsA patients (n = 1,230) | Controls (n = 1,230) | Unadjusted P (patients vs. controls)b | OR (95% CI) (patients/controls)c | Adjusted P (patients vs. controls)c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertension | 440 (35.8) | 289 (23.5) | < 0.0001d | 1.9 (1.6–2.4) | < 0.0001d |

| Hyperlipidemia | 425 (34.6) | 351 (28.5) | 0.0006d | 1.3 (1.1–1.6) | 0.0035d |

| Rheumatoid arthritise | 204 (16.6) | 9 (0.7) | < 0.0001d | 48.8 (17.0–139.9) | < 0.0001d |

| Diabetes mellitus | 196 (15.9) | 123 (10.0) | < 0.0001d | 1.6 (1.2–2.2) | 0.0008d |

| Depression | 112 (9.1) | 61 (5.0) | < 0.0001d | 2.1 (1.5–3.0) | < 0.0001d |

| Coronary heart disease | 81 (6.6) | 51 (4.1) | 0.0062d | 1.7 (1.1–2.5) | 0.0203f |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 7 (0.6) | 8 (0.7) | 1.0000 | 0.5 (0.1–3.0) | 0.4477 |

| Anxiety | 73 (5.9) | 49 (4.0) | 0.0233f | 1.4 (0.9–2.1) | 0.1207 |

| Obesity | 53 (4.3) | 40 (3.3) | 0.1634 | 1.4 (0.8–2.3) | 0.1922 |

| Other autoimmune disordersg | 39 (3.2) | 18 (1.5) | 0.0054d | 2.2 (1.1–4.3) | 0.0194f |

| Cerebrovascular disease (stroke) | 30 (2.4) | 20 (1.6) | 0.1404 | 1.5 (0.7–3.6) | 0.3154 |

| Occlusion and stenosis of precerebral arteries | 10 (0.8) | 11 (0.9) | 1.0000 | 0.7 (0.2–2.5) | 0.5883 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 29 (2.4) | 20 (1.6) | 0.1985 | 1.4 (0.7–2.8) | 0.3083 |

| Skin cancer | 27 (2.2) | 16 (1.3) | 0.0934 | 1.5 (0.7–3.1) | 0.2670 |

| Nonmelanoma | 27 (2.2) | 15 (1.2) | 0.0641 | 1.5 (0.7–3.1) | 0.2670 |

| Other malignanciesh | 25 (2.0) | 23 (1.9) | 0.7630 | 0.8 (0.4–1.7) | 0.5423 |

| Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitise | 16 (1.3) | 6 (0.5) | 0.0525 | 1.6 (0.4–6.8) | 0.5359 |

| Multiple sclerosise | 3 (0.2) | 3 (0.2) | 1.0000 | 1.0 (0.1–16.0) | 1.0000 |

| Lymphoma | 3 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0.2500 | N/A | N/A |

Values are the number (percentage) unless indicated otherwise. PsO/PsA‐related comorbidities were measured during the 12‐month study period. PsO = psoriasis; PsA = psoriatic arthritis; OR = odds ratio; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval; N/A = not applicable.

Univariate comparison was made using McNemar's tests (exact binomial distribution was used if the number of discordant pairs was ≤25).

ORs and P values were estimated using conditional logistic regression, controlling for insurance type, individual non–PsO/PsA‐related comorbidities, and modified Charlson Comorbidity Index calculated based on non–PsO/PsA‐related comorbidities. ORs >1 indicate increased risk for PsO+PsA patients compared with controls.

Significance at 0.01 level.

Classified as autoimmune diseases.

Significance at 0.05 level.

Other autoimmune disorders included alopecia areata, celiac disease, systemic sclerosis, Sjögren's syndrome, vitiligo, chronic urticaria, systemic lupus erythematosus, Addison's disease, giant cell arteritis, pulmonary fibrosis, and chronic glomerulonephritis.

Other malignancies included cancers of the lung, pharynx, liver, pancreas, breast, vulva, penis, bladder, and kidney.

Medication use

During the 12‐month study period, almost all PsO+PsA patients had at least one medication filled (99.9%) compared with 76.3% of controls (Table 3). PsO+PsA patients were more likely than controls to fill prescriptions for the treatment of selected comorbidities (63.5% versus 42.9%; aOR 2.5, P < 0.0001), including antidepressants (28.6% versus 15.4%; aOR 2.1, P < 0.0001), antidiabetic drugs (11.9% versus 7.4%; aOR 1.7, P = 0.0019), and cardiovascular drugs/antihypertensives (52.4% versus 36.1%; aOR 2.2, P < 0.0001). The mean numbers of prescriptions for antidepressants (0.55 versus 0.30; adjusted IRR [aIRR] 1.9, P < 0.0001), antidiabetic drugs (0.29 versus 0.20; aIRR 1.5, P = 0.0164), and cardiovascular drugs (2.36 versus 1.61; aIRR 1.4, P < 0.0001) filled by PsO+PsA patients were also significantly higher than those filled by the controls.

Table 3.

Medication use in moderate‐to‐severe PsO+PsA patients and matched controlsa

| Moderate‐to‐severe PsO+PsA patients (n = 1,230) | Controls (n = 1,230) | Unadjusted P (patients vs. controls)b | OR/IRR (95% CI) (patients/controls)c | Adjusted P (patients vs. controls)c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All‐cause medication | |||||

| Any medication filled, no. (%) | 1,229 (99.9) | 939 (76.3) | < 0.0001d | N/A | N/A |

| No. of distinct medications filled, mean ± SD | 12.77 ± 8.69 | 5.61 ± 6.45 | < 0.0001d | 2.3 (2.1–2.4) | < 0.0001d |

| Selected comorbidity‐related medication | |||||

| Any prescription filled, no. (%) | 781 (63.5) | 528 (42.9) | < 0.0001d | 2.5 (2.1–3.0) | < 0.0001d |

| No. of distinct medications filled, mean ± SD | 1.52 ± 2.11 | 1.11 ± 2.06 | < 0.0001d | 1.5 (1.3–1.7) | < 0.0001d |

| Antidepressants | |||||

| Any prescription filled, no. (%) | 352 (28.6) | 190 (15.4) | < 0.0001d | 2.1 (1.7–2.7) | < 0.0001d |

| No. of distinct medications filled, mean ± SD | 0.55 ± 1.07 | 0.30 ± 0.86 | < 0.0001d | 1.9 (1.5–2.3) | < 0.0001d |

| Antidiabetic drugs | |||||

| Any prescription filled, no. (%) | 146 (11.9) | 91 (7.4) | 0.0001d | 1.7 (1.2–2.4) | 0.0019d |

| No. of distinct medications filled, mean ± SD | 0.29 ± 0.93 | 0.20 ± 0.86 | 0.0062d | 1.5 (1.1–2.1) | 0.0164e |

| Cardiovascular drugs | |||||

| Any prescription filled, no. (%) | 645 (52.4) | 444 (36.1) | < 0.0001d | 2.2 (1.8–2.6) | < 0.0001d |

| No. of distinct medications filled, mean ± SD | 2.36 ± 2.91 | 1.61 ± 2.76 | < 0.0001d | 1.4 (1.2–1.6) | < 0.0001d |

Medication use was measured during the 12‐month study period. PsO = psoriasis; PsA = psoriatic arthritis; OR = odds ratio; IRR = incidence rate ratio; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval; N/A = not applicable.

Univariate comparison was made using McNemar's tests for ≥1 medication filled and Wilcoxon's signed rank tests for number of distinct medications filled.

ORs and P values were calculated for any medication filled from conditional logistic regression. IRRs and P values were calculated for number of distinct medications filled from negative binomial model with generalized estimating equation. All models controlled for age, sex, geographic region, index year, insurance type, individual non–PsO/PsA‐related comorbidities, and modified Charlson Comorbidity Index calculated based on non–PsO/PsA‐related comorbidities. ORs >1 and IRRs >1 indicate an increased risk and incidence rate, respectively, for PsO+PsA patients compared with controls.

Significance at 0.01 level.

Significance at 0.05 level.

All‐cause medical service utilization

PsO+PsA patients were more likely to use medical services, including inpatient admissions (10.8% versus 7.0%; aOR 1.6, P = 0.0102), ER visits (21.5% versus 17.2%; aOR 1.3, P = 0.0322), and outpatient visits (99.3% versus 85.4%; aOR 62.7, P < 0.0001), than controls over the 12‐month study period (Table 4). On average, PsO+PsA patients had more mean inpatient admissions (0.17 visits versus 0.10 visits; aIRR 1.5, P = 0.0093), ER visits (0.38 versus 0.28; aIRR 1.3, P = 0.0478), and outpatient visits (19.31 versus 8.73; aIRR 2.2, P < 0.0001), and had a significantly longer hospital stay (1.06 days versus 0.70 days; aIRR 2.0, P = 0.0222), than controls.

Table 4.

All‐cause medical service utilization in moderate‐to‐severe PsO+PsA patients and matched controlsa

| Moderate‐to‐severe PsO+PsA patients (n = 1,230) | Controls (n = 1,230) | Unadjusted P (patients vs. controls)b | OR/IRR (95% CI) (patients/controls)c | Adjusted P (patients vs. controls)c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inpatient admissions | |||||

| Any admission, no. (%) | 133 (10.8) | 86 (7.0) | 0.0005d | 1.6 (1.1–2.2) | 0.0102e |

| No. of admissions, mean ± SD | 0.17 ± 0.64 | 0.10 ± 0.43 | 0.0008d | 1.5 (1.1–2.1) | 0.0093d |

| Total length of stay, mean ± SD days | 1.06 ± 5.93 | 0.70 ± 7.08 | 0.0015d | 2.0 (1.3–3.2) | 0.0222e |

| Emergency room visits | |||||

| Any visit, no. (%) | 264 (21.5) | 212 (17.2) | 0.0086d | 1.3 (1.0–1.6) | 0.0322e |

| No. of visits, mean ± SD | 0.38 ± 1.05 | 0.28 ± 0.92 | 0.0038d | 1.3 (1.0–1.6) | 0.0478e |

| Outpatient visits | |||||

| Any visit, no. (%) | 1,221 (99.3) | 1,050 (85.4) | < 0.0001d | 62.7 (15.6–252.2) | < 0.0001d |

| No. of visits, mean ± SD | 19.31 ± 17.82 | 8.73 ± 11.16 | < 0.0001d | 2.2 (2.0–2.4) | < 0.0001d |

Medical service utilization was measured during the 12‐month study period. PsO = psoriasis; PsA = psoriatic arthritis; OR = odds ratio; IRR = incidence rate ratio; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval.

Univariate comparison was made using McNemar's tests for any visit and Wilcoxon's signed rank tests for number of visits or total length of stay.

ORs and P values were calculated for any visit from conditional logistic regression. IRRs and P values were calculated for number of visits or total length of stay from negative binomial model with generalized estimating equation. All models controlled for age, sex, geographic region, index year, insurance type, individual non–PsO/PsA‐related comorbidities, and modified Charlson Comorbidity Index calculated based on non–PsO/PsA‐related comorbidities. ORs >1 and IRRs >1 indicate an increased risk and incidence rate, respectively, for PsO+PsA patients compared with controls.

Significance at 0.01 level.

Significance at 0.05 level.

All‐cause health care costs

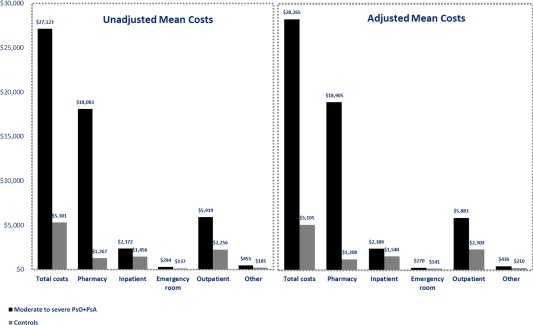

Compared with controls, PsO+PsA patients incurred significantly higher annual total health care costs ($27,123 versus $5,301; adjusted cost difference [ACD] $23,160), with most of the cost difference driven by pharmacy costs ($18,083 versus $1,267; ACD $17,696), followed by medical costs ($9,040 versus $4,035; ACD $5,077) (all P < 0.0001) (Figure 2). In addition, all medical cost components were higher in PsO+PsA patients, including inpatient services ($2,372 versus $1,456; ACD $849), ER ($294 versus $137; ACD $129), outpatient services ($5,919 versus $2,256; ACD $3,574), and other medical costs ($455 versus $185; ACD $225) (all P < 0.05).

Figure 2.

All‐cause health care costs in moderate‐to‐severe PsO+PsA patients and matched controls during the 12‐month study period (univariate and multivariate analyses). Adjusted mean costs were estimated from 2‐part regression models adjusting for age, sex, geographic region, index year, insurance type, and modified Charlson Comorbidity Index calculated based on non–PsO/PsA‐related comorbidities. All P < 0.05 for the comparison of unadjusted and adjusted mean costs between PsO+PsA patients and controls. All costs were adjusted to 2012 US dollars using the medical care component of the consumer price index. PsO = psoriasis; PsA = psoriatic arthritis.

DISCUSSION

This retrospective study used a large, recent, US administrative claims database to compare the comorbidities and health care utilization and costs between PsO patients with comorbid PsA and PsO‐ and PsA‐free controls in the era of biologic agents. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to estimate the disease burden associated with PsO+PsA compared to controls free of the two conditions. The study results demonstrated that moderate‐to‐severe PsO patients with comorbid PsA had a higher prevalence of comorbidities and greater health care resource utilization, including medication use, medical service utilization, and health care costs, compared with controls without PsO and PsA.

Our analysis demonstrated an elevated risk of comorbidities among moderate‐to‐severe PsO patients with comorbid PsA, particularly cardiometabolic diseases. Overall, the prevalence of comorbidities found in our study was consistent with existing literature. The risks of having comorbidities in our PsO+PsA sample are generally higher than those reported for the overall PsO sample in the literature, which could be explained by the positive relationship between severity of PsO and comorbidity burden.

Our study found that PsO+PsA patients had an elevated risk for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, obesity, diabetes mellitus, and coronary heart disease versus PsO‐ and PsA‐free controls, with aORs ranging from 1.3–1.9, which are higher than that reported for patients with mild PsO versus PsO‐free controls, but comparable to patients with more severe PsO versus PsO‐free controls 14, 32. Apart from cardiometabolic diseases, our analysis revealed significant associations between PsO/PsA and other comorbidities. Due to similar genetic, pathogenetic, and clinical features, moderate‐to‐severe PsO patients with comorbid PsA were more likely to have rheumatoid arthritis. This was consistent with findings in a previous US retrospective cohort study (aOR 3.6) comparing the general PsO patients with controls 33; however, the association was much stronger in the current study (aOR 49). Depression is another common comorbidity among PsO/PsA patients, and was associated with a 110% increased risk in our study, higher than the 49% increased risk reported for the general PsO patients 34. Our study did not find a significant association between PsO/PsA and cancer. Although a positive association was found between lymphomas and other nonmelanoma cancers in PsO patients 35, 36, there is no consistent conclusion on the association between PsA and cancer 37, 38. Further research is needed in this respect.

Given the chronic nature and heavy burden of comorbidities imposed by the disease, it is not surprising that PsO+PsA patients consume many health care resources. Results of utilization found among our PsO+PsA patients were consistent with existing literature 39. The incremental utilization of PsO and PsA relative to controls may be partially attributed to comorbidities associated with PsO and PsA. In our study, PsO+PsA patients used more than twice as many distinct medications, 1.5 times as many hospitalization admissions, 1.3 times as many ER visits, and 2.2 times as many outpatient visits as matched controls. Higher utilization leads to higher direct health care costs. Our PsO+PsA sample had an annual $23,000 incremental total health care cost, of which $18,000 was attributed to incremental pharmacy costs and $5,000 to incremental medical service costs. There is a lack of estimates of incremental costs associated with PsA compared with the general population in the literature. However, Yu et al found moderate‐to‐severe PsO patients had an annual incremental total health care cost of $7,084 in 2003 ($3,167 from medical services and $3,917 from drug costs in 2007 dollars), compared with controls without PsO or PsA 28.

Many existing biologic agents are indicated to treat PsO and PsA. Because the results of this study showed PsO+PsA patients had an increased risk of developing comorbidities, especially cardiovascular diseases (with an elevated risk for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and coronary heart disease versus PsO‐ and PsA‐free controls), an appropriate therapy in the early stage of PsO/PsA could be taken into consideration not only for its positive effect on articular and cutaneous symptoms, but also for its effect on the various aspects of this complex picture 40, 41, 42. However, therapies that are effective for PsO may not share similar effectiveness for PsA and vice versa. As demonstrated in this study, patients with concurrent PsO and PsA have high comorbidity and economic burden, and therefore warrant greater attention and more careful consideration when it comes to choosing appropriate treatment. This highlights the need for treatments that are cost effective for both conditions.

This study is subject to several limitations. First, it is an observational study that could be affected by unobserved differences between comparison cohorts. Second, classification biases may exist, since PsO/PsA‐related comorbidities could be underestimated because their identification is based on ICD‐9‐CM codes. Another classification bias may arise from the identification of moderate‐to‐severe PsO patients using treatment claims. Due to the lack of clinical measures of PsO severity in the claims data sets, a treatment type was used as a proxy for disease severity, which is a method commonly used in commercial claims database analyses for PsO studies 22, 43. Third, this study was from a third‐party payer perspective and did not include patient out‐of‐pocket costs or indirect costs. The economic burden from a societal perspective could be even higher. Future studies are also needed to quantify indirect costs, because PsO and PsA are associated with productivity loss and work absenteeism 44, 45. Lastly, generalization of findings to populations beyond the commercially insured patients (e.g., Medicaid or Medicare patients) or adults ages 18–64 years should be made with caution.

This study demonstrated substantial economic and comorbidity burdens among moderate‐to‐severe PsO patients with comorbid PsA, even with the availability of biologic treatments. Effective control of PsO and PsA, as well as the comorbidities, might be critical for this population.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all authors approved the final version to be submitted for publication. Drs. Zhao and Shi had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study conception and design. Feldman, Zhao, Shi, Tran.

Acquisition of data. Shi.

Analysis and interpretation of data. Feldman, Zhao, Shi, Tran, Lu.

ROLE OF THE STUDY SPONSOR

Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation reviewed and approved the study design, study protocol, and approved the manuscript for publication.

Supporting information

Supporting Information Appendix

REFERENCES

- 1. National Psoriasis Foundation. URL: https://www.psoriasis.org/learn_statistics.

- 2. Moll JM, Wright V. Psoriatic arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1973;3:55–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zachariae H. Prevalence of joint disease in patients with psoriasis: implications for therapy. Am J Clin Dermatol 2003;4:441–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Myers WA, Gottlieb AB, Mease P. Psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: clinical features and disease mechanisms. Clin Dermatol 2006;24:438–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gladman DD, Antoni C, Mease P, Clegg DO, Nash P. Psoriatic arthritis: epidemiology, clinical features, course, and outcome. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64:ii14–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Helliwell PS, Taylor WJ. Classification and diagnostic criteria for psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64:ii3–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gottlieb A, Korman NJ, Gordon KB, Feldman SR, Lebwohl M, Koo JY, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 2. Psoriatic arthritis: overview and guidelines of care for treatment with an emphasis on the biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008;58:851–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rosen CF, Mussani F, Chandran V, Eder L, Thavaneswaran A, Gladman DD. Patients with psoriatic arthritis have worse quality of life than those with psoriasis alone. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2012;51:571–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Armstrong AW, Harskamp CT, Armstrong EJ. The association between psoriasis and obesity: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of observational studies. Nutr Diabetes 2012;3:e54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gottlieb AB, Dann F. Comorbidities in patients with psoriasis [review]. Am J Med 2009;122:1150.e1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cohen AD, Weitzman D, Dreiher J. Psoriasis and hypertension: a case‐control study. Acta Derm Venereol 2010;90:23–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Love TJ, Qureshi AA, Karlson EW, Gelfand JM, Choi HK. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in psoriasis: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003–2006. Arch Dermatol 2011;147:419–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schatteman L, Mielants H, Veys EM, Cuvelier C, De Vos M, Gyselbrecht L, et al. Gut inflammation in psoriatic arthritis: a prospective ileocolonoscopic study. J Rheumatol 1995;22:680–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Costa L, Caso F, D'Elia L, Atteno M, Peluso R, Del Puente A, et al. Psoriatic arthritis is associated with increased arterial stiffness in the absence of known cardiovascular risk factors: a case control study. Clin Rheumatol 2012;31:711–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Neimann AL, Shin DB, Wang X, Margolis DJ, Troxel AB, Gelfand JM. Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in patients with psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006;55:829–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tobin AM, Veale DJ, Fitzgerald O, Rogers S, Collins P, O'Shea D, et al. Cardiovascular disease and risk factors in patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol 2010;37:1386–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ritchlin C. Psoriatic disease: from skin to bone. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol 2007;3:698–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yeung H, Takeshita J, Mehta NN, Kimmel SE, Ogdie A, Margolis DJ, et al. Psoriasis severity and the prevalence of major medical comorbidity: a population‐based study. JAMA Dermatol 2013;149:1173–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gelfand JM, Troxel AB, Lewis JD, Kurd SK, Shin DB, Wang X, et al. The risk of mortality in patients with psoriasis: results from a population‐based study. Arch Dermatol 2007;143:1493–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wong K, Gladman DD, Husted J, Long JA, Farewell VT. Mortality studies in psoriatic arthritis: results from a single outpatient clinic. I: causes and risk of death. Arthritis Rheum 1997;40:1868–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gunnarsson C, Chen J, Rizzo JA, Ladapo JA, Naim A, Lofland JH. The direct healthcare insurer and out‐of‐pocket expenditures of psoriasis: evidence from a United States national survey. J Dermatolog Treat 2012;23:240–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kimball AB, Guerin A, Tsaneva M, Yu AP, Wu EQ, Gupta SR, et al. Economic burden of comorbidities in patients with psoriasis is substantial. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2011;25:157–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Menter A, Gottlieb A, Feldman SR, Van Voorhees AS, Leonardi CL, Gordon KB, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 1. Overview of psoriasis and guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008;58:826–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ahn CS, Gustafson CJ, Sandoval LF, Davis SA, Feldman SR. Cost effectiveness of biologic therapies for plaque psoriasis. Am J Clin Dermatol 2013;14:315–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Anis AH, Bansback N, Sizto S, Gupta SR, Willian MK, Feldman SR. Economic evaluation of biologic therapies for the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis in the United States. J Dermatolog Treat 2011;22:65–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vena GA, Vestita M, Cassano N. Can early treatment with biologicals modify the natural history of comorbidities? Dermatol Ther 2010;23:181–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fowler JF, Duh MS, Rovba L, Buteau S, Pinheiro L, Lobo F, et al. The impact of psoriasis on health care costs and patient work loss. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008;59:772–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yu AP, Tang J, Xie J, Wu EQ, Gupta SR, Bao Y, et al. Economic burden of psoriasis compared to the general population and stratified by disease severity. Curr Med Res Opin 2009;25:2429–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Javitz HS, Ward MM, Farber E, Nail L, Vallow SG. The direct cost of care for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002;46:850–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Romano PS, Roos LL, Jollis JG. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD‐9‐CM administrative data: differing perspectives. J Clin Epidemiol 1993;46:1075–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bureau of Labor Statistics . Consumer price index: CPI databases. URL: http://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm.

- 32. Gladman DD, Ang M, Su L, Tom BD, Schentag CT, Farewell VT. Cardiovascular morbidity in psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:1131–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wu JJ, Nguyen TU, Poon KY, Herrinton LJ. The association of psoriasis with autoimmune diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol 2012;67:924–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schmitt J, Ford DE. Psoriasis is independently associated with psychiatric morbidity and adverse cardiovascular risk factors, but not with cardiovascular events in a population‐based sample. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2010;24:885–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gelfand JM, Shin DB, Neimann AL, Xingmei W, Margolis DJ, Troxel AB. The risk of lymphoma in patients with psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol 2006;126:2194–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Stern RS, Scotto J, Fears TR. Psoriasis and susceptibility to nonmelanoma skin cancer. J Am Acad Dermatol 1985;12:67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rohekar S, Tom BD, Hassa A, Schentag CT, Farewell VT, Gladman DD. Prevalence of malignancy in psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:82–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nannini C, Cantini F, Niccoli L, Cassara E, Salvarani C, Olivieri I, et al. Single‐center series and systematic review of randomized controlled trials of malignancies in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis receiving anti‐tumor necrosis factor alpha therapy: is there a need for more comprehensive screening procedures? Arthritis Rheum 2009;61:801–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zink A, Thiele K, Huscher D, Listing J, Sieper J, Krause A, et al. Healthcare and burden of disease in psoriatic arthritis: a comparison with rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol 2006;33:86–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Saraceno R, Schipani C, Mazzotta A, Esposito M, Di Renzo L, De Lorenzo A, et al. Effect of anti‐tumor necrosis factor‐alpha therapies on body mass index in patients with psoriasis. Pharmacol Res 2008;57:290–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Costa L, Caso F, Atteno M, Del Puente A, Darda MA, Caso P, et al. Impact of 24‐month treatment with etanercept, adalimumab, or methotrexate on metabolic syndrome components in a cohort of 210 psoriatic arthritis patients. Clin Rheumatol 2014;33:833–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Martinez‐Abundis E, Reynoso‐von Drateln C, Hernandez‐Salazar E, Gonzalez‐Ortiz M. Effect of etanercept on insulin secretion and insulin sensitivity in a randomized trial with psoriatic patients at risk for developing type 2 diabetes mellitus. Arch Dermatol Res 2007;299:461–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Crown WH, Bresnahan BW, Orsini LS, Kennedy S, Leonardi C. The burden of illness associated with psoriasis: cost of treatment with systemic therapy and phototherapy in the US. Curr Med Res Opin 2004;20:1929–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ciocon DH, Horn EJ, Kimball AB. Quality of life and treatment satisfaction among patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis and patients with psoriasis only: results of the 2005 Spring US National Psoriasis Foundation Survey. Am J Clin Dermatol 2008;9:111–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Puig L, Strohal R, Husni ME, Tsai TF, Noppakun N, Szumski A, et al. Cardiometabolic profile, clinical features, quality of life and treatment outcomes in patients with moderate‐to‐severe psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. J Dermatolog Treat 2013. E‐pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information Appendix