Abstract

Analysis of molecules by ion mobility spectrometry coupled with mass spectrometry (IMS-MS) provides chemical information on the three dimensional structure and mass of the molecules. The coupling of ion mobility to trapping mass spectrometers has historically been challenging due to the large differences in analysis time between the two devices. In this paper we present a modification of the trapped ion mobility (TIMS) analysis scheme termed “Gated TIMS” that allows efficient coupling to a Fourier Transform Ion Cyclotron Resonance (FT-ICR) analyzer. Analyses of standard compounds and the influence of source conditions on the TIMS distributions produced by ion mobility spectra of labile ubiquitin protein ions are presented. Ion mobility resolving powers up to 100 are observed. Measured collisional cross sections of ubiquitin ions are in excellent qualitative and quantitative agreement to previous measurements. Gated TIMS FT-ICR produces results comparable to those acquired using TIMS/time-of-flight MS instrument platforms as well as numerous drift tube IMS-MS studies published in the literature.

Introduction

When ion mobility spectrometry (IMS) was developed in the 1960s [1], it was first used to study gas phase ion chemistry. Whereas standalone IMS systems have been used primarily as a chemical sensors in homeland security applications [2], the coupling of IMS to mass spectrometry (MS) creates a versatile instrument that provides information on both the size and the molecular weight of the analyzed species [3]. Accordingly, IMS-MS has been more recently used in a wide variety of chemical [4–9], physical [10–14], and biological applications [15–33].

Ion mobility spectrometry was initially performed in a drift tube. As a dispersive ion mobility technique, ion separation in drift tube IMS involves guiding ions with a weak electric field through a tube filled with neutral buffer gas where separation is based on both size and charge. Though drift tubes have the advantage that they can be used to determine mobility based on first principles, drift tubes suffer from radial ion losses due to the thermal diffusion and Coulomb repulsion. This principally limits IMS sensitivity when coupled to MS.

The ion funnel was developed in the 1990s [34] to improve the transfer of ions generated from soft ionization sources, such as electrospray ionization (ESI), as they passed from high- to low-pressure regions, and ultimately into the vacuum of the mass analyzer. Ion funnels operate by focusing ions through a series of stacked ring electrodes of decreasing inner diameter. A radiofrequency potential is applied 180 degrees out of phase to adjacent electrodes, thus creating a radially confining pseudopotential [34]. The focusing ability of the ion funnel has been successfully implemented in drift tube instruments, to recapture radially diffuse ion clouds after mobility separation, for efficient transfer into the mass spectrometer. Placement of an ion funnel between the drift tube and the mass spectrometer significantly improves the sensitivity of the hybrid technique by focusing the radially diffuse ion packets through conductance limiting apertures [35, 36].

Recently, the technique of Trapped Ion Mobility Spectrometry (TIMS) was developed by Park and coworkers [37], wherein ion mobility separation is performed entirely inside an ion funnel. Inverse to drift tube IMS, TIMS operates by passing gas through swarms of stationary ions that are repelled by a repulsive electric field gradient. Advantages of TIMS include: (1) high transmission efficiencies in MS and IMS-MS modes, (2) compact design allowing integration into many instrument platforms, (3) determination of reduced mobility or collisional cross section from a simple calibration [38, 39], (4) low operating potentials, (5) flexibility to alter ion mobility resolving power and duty cycle, and (6) superior mobility resolving power that can exceed 250 [37, 39, 40]. Recently, TIMS has been shown to produce mobility distributions for proteins and peptides (whose conformations are known to depend on a number of physicochemical parameters) that are virtually identical to those measured by drift tube IMS operating below the low field limit where ion temperatures are known to be near thermal [39, 40].

One of the challenges in coupling dispersive IMS to MS is the need for a mass analyzer with a spectral acquisition rate sufficiently fast to sample the mobility distribution. Typically, time-of-flight (TOF) mass analyzers are employed, owing to their ability to efficiently sample mobility-separated ions on the millisecond timescale. However, a few IMS-MS instruments have dispersive IMS techniques coupled to a trapping mass analyzer [41–43]. Alternatively, approaches have been designed to decrease the dispersive IMS timescale, but none of these experimental techniques have been applied to hybridization with trapping MS analyzers [44, 45]. IMS coupling to Fourier Transform Ion Cyclotron Resonance mass spectrometry (FT-ICR MS) is particularly challenging due to its relatively slow spectral acquisition rate (~1 s per spectrum).

To overcome this principal limitation, TIMS was first coupled to an FT-ICR analyzer using a modified electric field gradient that allowed for increased ion accumulation times. This embodiment, termed Selective Accumulation-TIMS (SA-TIMS), has been successfully used to analyze complex mixtures. The combination of ion mobility and accurate mass measurement has been used to identify compounds from complex mixtures, in applications ranging from hydrocarbon analysis in petroleum to the identification of endocrine disrupters from complex environmental matrices [46, 47].

Since the inception of TIMS, a number of significant improvements have been recently implemented. The application of “parallel accumulation” allows a near 100% duty cycle [48], modification of the field curvature of the TIMS trapping field allows for improved ion storage capacity and resolving power [49], and a fundamental theory for TIMS operation has been developed and validated by simulations and experiments [50, 51]. These improvements cannot be directly applied to SA-TIMS due to differences in the experimental method, and results produced by SA-TIMS cannot be easily compared with results produced by TIMS-TOF MS. With these recent advancements in TIMS and with the desire to align TIMS analyzers across all MS platforms, we evaluate here a new operational scheme for TIMS, termed Gated TIMS, as an alternative method for coupling to FT-ICR MS.

Materials and Methods

Ubiquitin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was diluted to a concentration of 1 µM in 70:30:0.1 water:acetonitrile:formic acid. Low concentration Tune Mix (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA), a series of perfluoroalkylphosphazenes, was used without dilution. Samples were ionized via static nanospray using a glass capillary pulled in-house. The acquisition parameters for the TIMS and FTMS instruments described below are listed in the appendix.

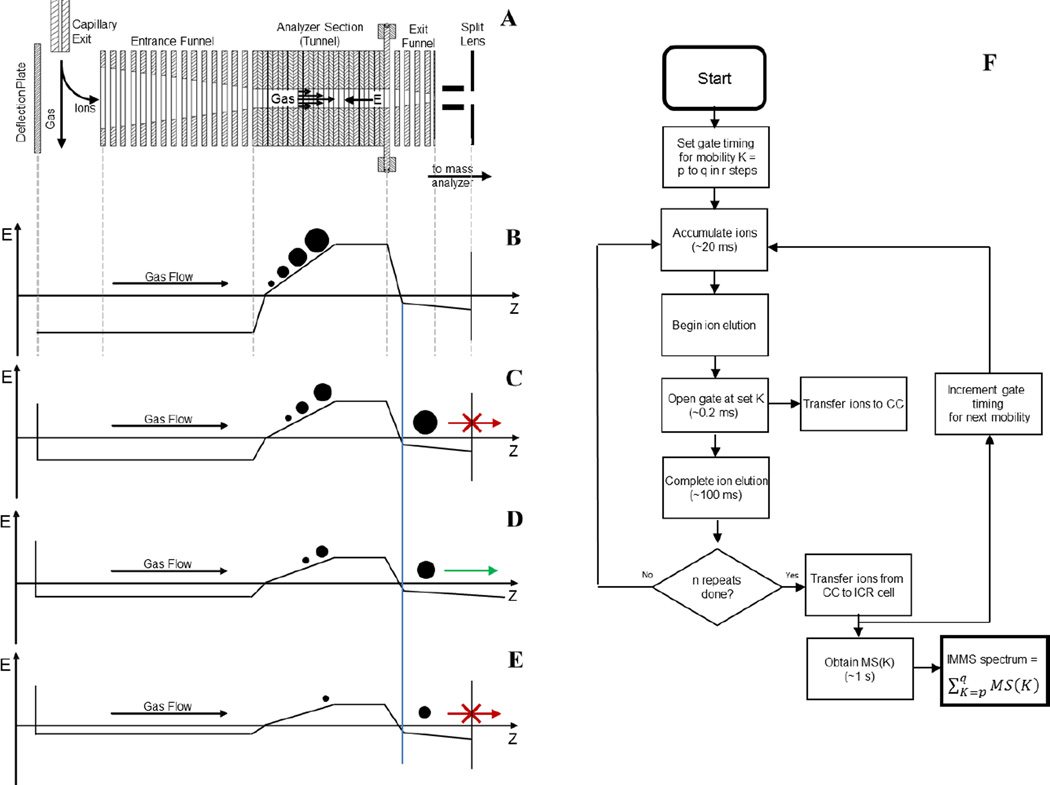

Experiments were performed on a modified 12 T FT-ICR MS (solariX, Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany). The production level ion funnel that conventionally occupies the first pumping region of the instrument vacuum system was replaced with a TIMS funnel. This design incorporates an entrance funnel, a tunnel, and an exit funnel. A schematic of the relevant parts of the experimental setup and the various steps in its operation are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the TIMS device and experiment timing, with ion motion moving left to right along the z-axis. A: Cross section of the TIMS analyzer with relevant ion optics labeled. B: Beginning of a TIMS experiment where ions are accumulated in the TIMS analyzer and undergo mobility separation. C: Beginning of ion elution out of the TIMS analyzer, ions cannot pass to the collision cell due to blocking by the gate lens. D: Ions continue to elute, ions with the desired mobility are allowed to pass the gate lens. E: Ions continue to elute and are blocked from entering the collision cell by the gate lens. F: Timing flow chart of the Gated TIMS experiment.

Figure 1A is a cross-sectional view of the TIMS funnel. Ions are produced in the ESI source via static nanospray. Ions entrained in nitrogen gas are introduced into the first pumping region via the capillary exit. As shown in Figure 1A, the gas flow is directed across the inlet of the entrance funnel. Application of a repulsive potential to the deflection plate deflects ions out of the gas stream, into the entrance funnel, and ultimately into the TIMS tunnel. In MS-only operation, ions are allowed to pass through the TIMS tunnel and are simply transmitted downstream to the mass analyzer.

However, for TIMS-MS experiments, ions are accumulated in the TIMS tunnel. Application of an RF potential (~250 Vpp, 900 kHz) to the TIMS funnel electrodes confines the ions radially throughout the TIMS funnel. DC potentials applied to the funnel and tunnel electrodes generate the field that pushes ions along the funnel-tunnel axis. The strength of this DC electric field as a function of position in the TIMS funnel at various points in the Gated TIMS FT-ICR MS experiment is depicted in Figures 1B – 1E. In these plots, a negative value indicates the field is pushing ions downstream, towards the mass analyzer, whereas a positive value indicates it is pushing the ions upstream.

To perform a TIMS experiment, some of the nitrogen from the capillary exit is diverted to flow through the TIMS tunnel and is then pumped away laterally in the exit funnel region. The gas flow pushes ions in the tunnel downstream. To accumulate ions in the tunnel, the DC electric field is set as depicted in Figure 1B. In such a case, ions are deflected into the entrance funnel. The ions are directed further through the entrance funnel and into the TIMS tunnel by the DC field. Finally, the ions are trapped in the tunnel radially by the confining RF field, and axially by the balancing forces exerted by the gas flow and the DC field.

As shown in Figure 1B, the axial electric field in the tunnel increases in strength with position, with the slope of the electric field set by a resistor-divider chain on the ion funnel. This allows for accumulation of ions having a range of mobilities. Ions of low mobility, depicted as a large circle, are pushed downstream more strongly by the gas and therefore accumulate at a position where the retarding DC field is greater. On the other hand, ions of high mobility, depicted as a small circle, come to rest at a position where the retarding DC field is weaker.

Once a group of ions has been accumulated, the potential on the deflection plate is set to an attractive potential, as indicated in Figures 1C – E, such that no additional ions from the ESI source can enter the TIMS analyzer. The group of ions that are trapped in the TIMS tunnel can then be eluted. As depicted in Figures 1B – E, this is done by decreasing the strength of the electric field gradient profile over time. Because the low mobility ions are pushed most strongly by the gas flow, these ions will be the first to overcome the electric field barrier represented by the plateau (Figure 1C). As the amplitude of the electric field gradient profile continues to be lowered, moderate (Figure 1D) and then high mobility ions (Figure 1E) will overcome the barrier and elute.

Unlike previous TIMS analyzers and methods, the experimental setup in the present work includes an ion gate downstream of the TIMS tunnel (see Figure 1A). This allows for the elimination/selection of ions, based on mobility, as they elute from the TIMS analyzer. All ions outside a selected range or ranges of mobility are eliminated by deflection, followed by collision with the gate electrodes. The gate is comprised of a metal plate that has been split into two halves – i.e. a “split lens”. To transmit ions, the two halves are biased to the same DC potential such that ions are focused into the downstream optics (Figure 1D). To block the transmission of ions, the two halves are biased at opposite polarities such that the ions are deflected orthogonal to the ion optical beam path resulting in their collision with the split lens elements (Figures 1C and 1E). Tests of the split lens gate showed that it can select/deselect ions with a time resolution of better than 0.2 ms.

The incorporation of an ion gate as described above allows for the hybridization of the TIMS analyzer with slower mass analyzers – i.e. mass analyzers that otherwise would not be able to keep up with the rapid elution of ions from the TIMS analyzer. The method associated with the hybridization of gated TIMS with an FT-ICR mass analyzer is further detailed in Figure 1F. In the experiment exemplified here, the sample is analyzed over the mobility range from mobility p to mobility q in r steps. The result is a set of r FT-ICR mass spectra, each of which corresponds to a segment of the mobility range p to q. These mass spectra, when taken together, constitute a multidimensional IMMS spectrum of the original sample.

As discussed above, the individual gated TIMS experiment consists of the steps of ion “accumulation” (Figure 1B), and “elution” (Figures 1C – E) with gating of the ions. The ions selected in the elution/gating step are transmitted to, and collected in, a collision cell (an RF driven hexapole, operated at a pressure of about 10−3 mbar of N2. As indicated in Figure 1F, an individual gated TIMS cycle lasts on the order of 100 ms, however, the FT-ICR mass analysis may require as long as one second. This allows for the performance of several gated TIMS cycles per mass analysis. Thus, as indicated in Figure 1F, the gated TIMS cycle is repeated n times, with the resultant ions of selected mobility/mobilities accumulated all together in the collision cell. In the experiments performed here, all of the ions accumulated in the collision cell via n experiments are of the same mobility, K.

At the end of n gated TIMS cycles, the contents of the collision cell are transferred to the ICR cell for m/z analysis. While the FT-ICR mass analyzer is producing a mass spectrum of these ions, the timing of the gated TIMS is incremented to the next mobility in the range and the next group of ions is accumulated in the collision cell. In this manner the TIMS gate and associated timing are incremented through the mobility range – from p to q – in r steps producing a FT-ICR mass spectrum at each step. All the resulting mass spectra are combined to from the multidimensional IMMS spectrum.

Results and Discussion

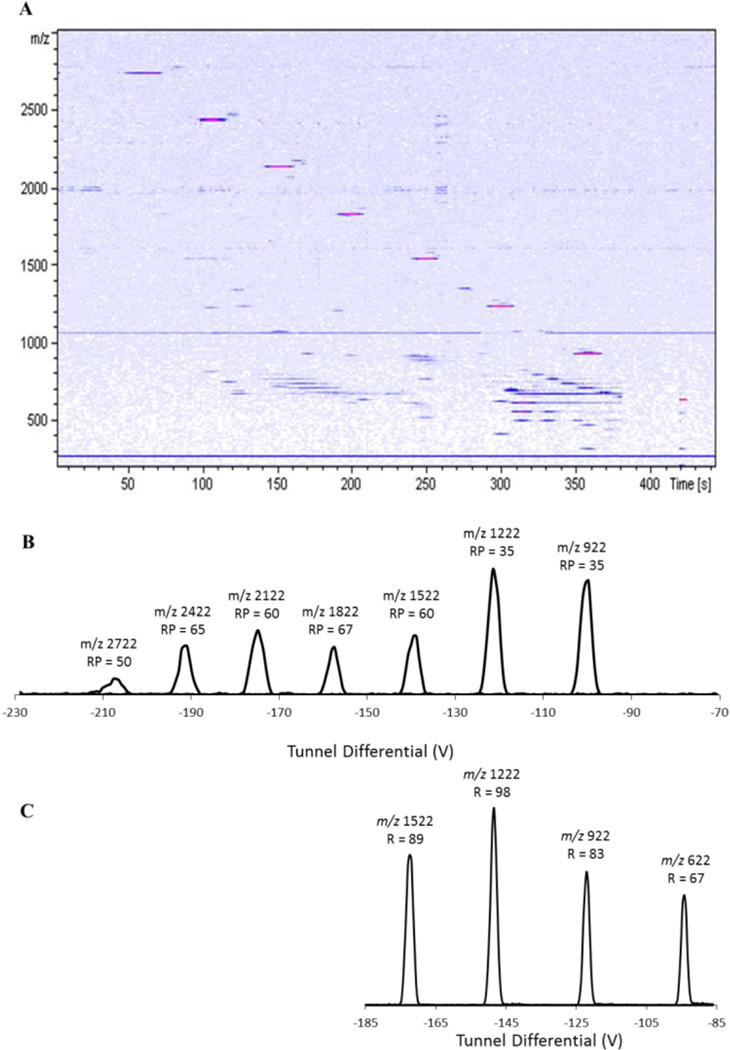

The Gated TIMS device was initially characterized by performing ion mobility separations on Agilent tune mix, as shown in Figure 2. The heatmap (Figure 2 A) shows baseline separation in both m/z space (y-axis) and mobility space (x-axis) for ions m/z 922 – m/z 2722. Extracted ion “mobiligrams” for the tune mix ions are shown in Figure 2B. Resolving powers around 60 are observed for ions over much of this mobility range, as shown above each peak in the figure.

Figure 2.

A. Heatmap of m/z vs. elution time from a low ion mobility resolution analysis of Agilent Tune Mix. B. Extracted ion mobiligrams of each component of tune mix with their m/z and resolving power. C. High resolution extracted ion mobiligrams from the high ion mobility resolution analysis of the Agilent Tune Mix.

Unique to the TIMS method is the flexibility to adjust mobility resolving power, mobility range, and the speed of the experiment, according to the application. This is done, in part, by controlling the potential range over which the tunnel DC is scanned and the rate at which it is scanned. For the data presented in Figures 2A and B, the potential on the tunnel was scanned quickly (3 V/ms) over a broad range of mobilities, producing a spectrum having a relatively modest resolving power. In contrast, the spectrum shown in Figure 2C was produced by scanning the tunnel voltage more slowly (0.96 V/ms) and over a narrower voltage range. As a result, the observed resolving powers were significantly higher: 80 to near 100 for ions with m/z 622 – 1522. Achieving higher mobility resolution ion mobility spectra requires not only slow elution from the TIMS analyzer but also narrower mobility steps – i.e., more “r” – in a given range (see Figure 1F) – and therefore a longer time spent acquiring the IMMS spectrum. This is exemplified in the experiment of Figure 2, where the low resolving power data in Figure 2B were acquired in approximately 450 seconds whereas the higher resolving power data in Figure 2 C were acquired in approximately 1650 seconds.

As described previously with respect to TIMS-TOF MS results [40], data like those in Figure 2 can be used to calibrate the TIMS analyzer via the simple relation – K α 1/V. Using the known mobility for each component of tune mix and the data in Figure 2B, one can calibrate the analyzer for reduced mobility. As with previous TIMS-TOF MS results, a plot of the reduced mobilities of the tune mix species vs. the inverse of their elution voltages revealed a highly linear relationship (R2 = 0.9999, data not shown). The resultant calibration was subsequently used as an external calibration for the ubiquitin analysis (below). The mobilities measured for ubiquitin ions were then readily converted to collisional cross sections, resulting in the values reported in Figures 3 and 4.

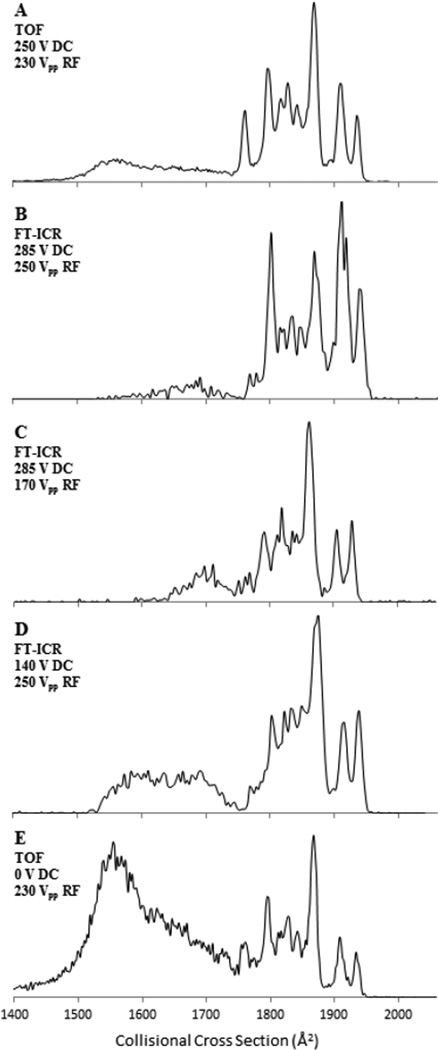

Figure 3.

Conformational distribution of the 7+ charge state of ubiquitin showing, partially folded, and elongated structures as a function of voltage applied across the entrance funnel and the funnel RF amplitude. Plots A and E were generated on a TIMS-TOF MS and reproduced with permission by the Royal Society of Chemistry from [40], plots B – D were generated with Gated TIMS-FT-ICR MS.

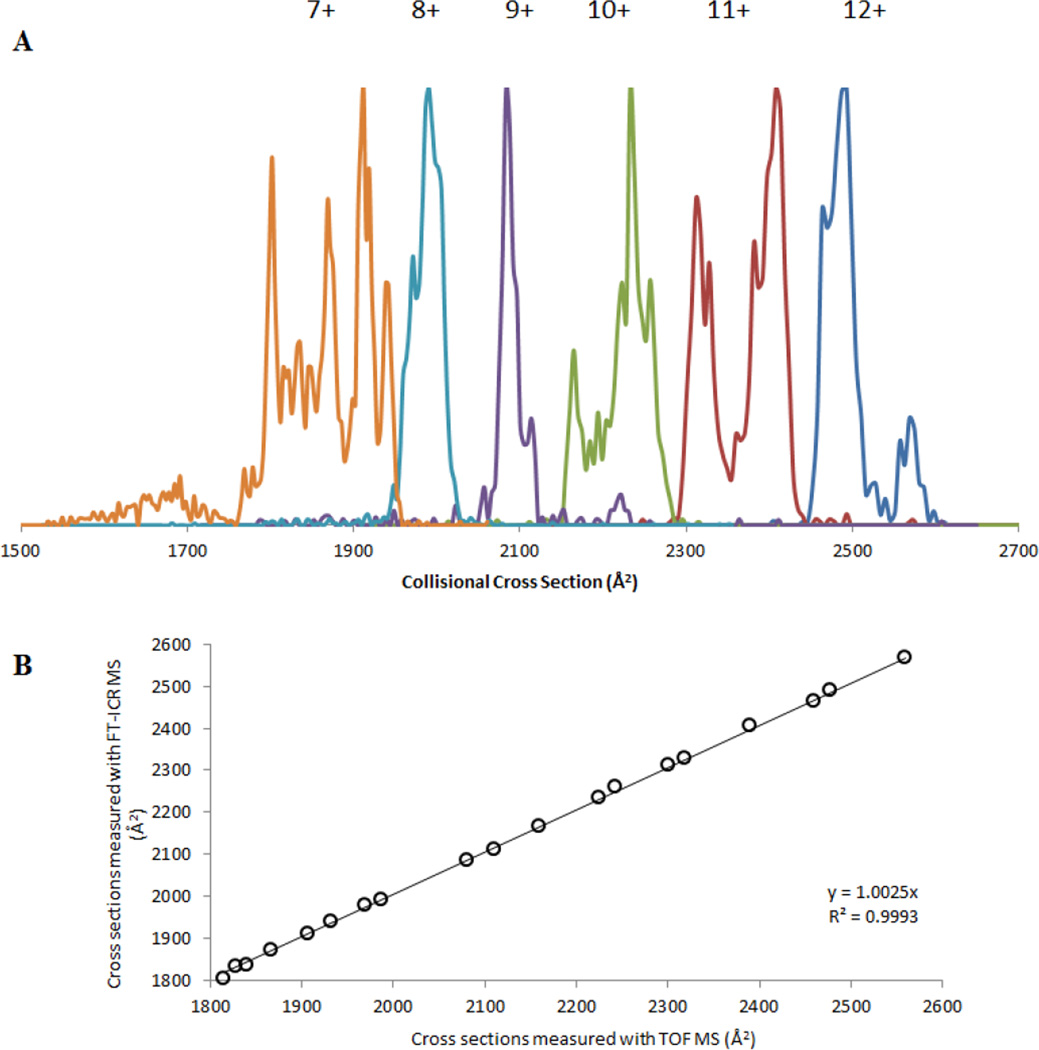

Figure 4.

A. TIMS distributions for selected m/z values in the ESI mass spectra of ubiquitin. Patterns are the same for FT-ICR MS and TOF MS. B. Comparison of measured collisional cross sections of the most abundant peaks for all charge states in the ubiquitin mass spectra generated by Gated TIMS-FT-ICR MS and TIMS-TOF MS measurements.

Ions of the 7+ charge state of ubiquitin display (m/z 1224) a number of different conformers (compact, partially folded, and elongated) that have been extensively studied by ion mobility [52, 53]. In the present work, mobiligrams of the 7+ charge state were acquired under varying experimental conditions using Gated TIMS. These results were then compared to data previously acquired by TIMS-TOF MS (Figure 3). The mobility spectra shown in Figures 3A and 3E were obtained from a prototype TIMS-TOF MS instrument whereas the data in Figures 3B – 3D were obtained using the Gated TIMS FT-ICR instrument described above. The plots in Figure 3 are shown with the x-axis in Å2 and the cross-section values were calculated from the tune mix calibration.

Mobiligrams acquired using similar TIMS conditions with m/z analysis by TOF [40] and FT-ICR MS analysis of the 7+ charge state are shown in Figures 3A and B, respectively. Not surprisingly, these two data sets exhibit similar features. For example, little or no compact conformers, a small amount of partially folded species, and abundant elongated forms are observed in all cases. Also, three abundant peaks corresponding to elongated forms are observed between 1880 Å2 and 1950 Å2, and an abundant peak is observed at 1800 Å2. The elongated form appears more abundant in the Gated TIMS data than in the TIMS-TOF MS data, but this may be due to an increase in the Funnel 1 DC gradient (discussed below). Overall, very similar mobiligrams were generated from two different mass spectrometers equipped with the same TIMS analyzer, demonstrating the cross-platform capabilities of the TIMS analyzer.

The 7+ charge state of ubiquitin is also ideal for studying the influence of source conditions on the observed conformations, as it is sensitive to heating and will undergo conformational changes from compact to elongated forms if the source or analyzer is too energetic [54, 55]. For example, ion mobility devices employing RF have the potential to heat ions due to energetic collisions with the background gas, causing annealing of protein ions to gas phase structures[40, 56]. To explore the influence of the RF and DC potentials of Gated TIMS on the conformers of the 7+ charge state, mobiligrams were acquired as the RF amplitudes on the tunnel and funnel and the DC potential difference between the ion funnel 1 entrance and exit lenses were varied, as shown in Figure 3B – D. The potentials of these two components of the TIMS analyzer have been shown to greatly influence the measured mobilogram [40].

Figure 3 is plotted with conditions being most energetic at Figure 3A and least energetic at Figure 3E. Figures 3B and C show the conformational distribution of the 7+ ions of ubiquitin measured with Gated TIMS with the peak-to-peak RF on the ion funnel set at 250 Vpp and 170 Vpp, respectively. As shown, decreasing the RF has some small influence on the conformations. For example, the signal height in the partially folded region (1650 Å2 – 1750 Å2) is greater and the signal height in the elongated region (1800 Å2 – 1950 Å2) is reduced with lower RF (Figure 3C), suggesting slight heating effects due to the applied RF.

Comparing Figures 3B and D, the DC potential difference across ion funnel 1 has a more significant influence on the observed gas phase structures. For example, when low DC potentials are placed across ion funnel 1 (Figure 3D), an abundant partially folded state of the 7+ ions is observed around 1500 – 1700 Å2. As the voltage gradient across ion funnel 1 is increased (Figure 3B), evidence for a significant conversion of partially folded to elongated conformations is observed as a decrease in abundance in the 1500 – 1700 Å2 region, suggesting heating of the ions through collisions with the background gas as they pass through ion funnel 1 and enter the tunnel. Similar behavior is observed in TIMS-TOF measurements, as exemplified in Figures 3A and E. Decreasing the voltage gradient across ion funnel 1, from 250 V to 0 V causes an increase of the partially folded form (1500 – 1700 Å2) relative to the elongated form (1750 – 1950 Å2). Overall, similar behaviors with respect to both the RF and DC potentials have been observed in the TIMS-TOF MS and Gated TIMS FT-ICR MS analyses of the 7+ ions of ubiquitin [40], demonstrating the tuning capabilities and performance similarities of these TIMS analyzers.

A compilation of the m/z selected Gated TIMS mobiligrams of the observed charge states of ubiquitin is shown in Figure 4 A. Baseline separation of nearly all the charge states is observed, and the data show a direct correlation between the ion charge state and its collisional cross section. Specifically, the collisional cross section increases as the charge state increases, suggesting the preference for the formation of elongated structures [57]. These extracted ion mobiligrams are comparable to what has been previously measured by TIMS-TOF MS. Largely the same number of conformations, as well as the same cross sections, are observed for any given ion charge state by Gated TIMS FT-ICR as by TIMS-TOF MS.

A comparison of the abundant peaks observed in TIMS-TOF [40] to the Gated TIMS FT-ICR data is made in the form of a plot in Figure 4 B. Here the measured collisional cross sections of the most abundant peaks for each charge state generated from TIMS-TOF MS are plotted on the x-axis, and the corresponding results from cross section measurements generated by Gated TIMS FT-ICR MS are plotted on the y-axis. A perfect match between these data sets would generate a line with a slope of one. The data of Figure 4 form a line with a slope of 1.0025 and an R2 value of 0.9993, showing excellent correlation between the two sets of data. On average, the mobility cross sections measured by Gated TIMS FT-ICR MS differ from those measured by TIMS-TOF MS by 7 Å2 (about 0.3%). The average error between Gated TIMS-FT ICR and TIMS-TOF collision cross sections is 0.3% (about 7 Å2) which is similar in magnitude to the error associated with day-to-day stability of TIMS-TOF instrument platforms (0.6 %, data not shown).

Conclusions

In the present work we have detailed and demonstrated the experimental setup and operation of Gated TIMS in conjunction with an FT-ICR mass analyzer. Overall, the results are consistent with the expectation that Gated TIMS operates on the same principles as TIMS without a gate. In particular with Gated TIMS FT-ICR, we observed a linear relationship between mobility and 1/V (R2 = 0.9999). This relationship was used to calibrate the Gated TIMS analyzer and then to determine collisional cross sections of ubiquitin ions. Importantly, the observed mobility resolutions (up to about 100) and their dependence on various instrument parameters, for example the scan speed, are also consistent with basic TIMS theory. The measurement of ubiquitin conformers and their cross sections show excellent agreement with previous results (R2 = 0.9993). Gated TIMS with FT-ICR MS produced spectra showing ubiquitin conformations with cross sections within about 0.3% on average to those measured by TIMS-TOF MS. The combination of high mobility resolution Gated TIMS and high mass resolution FT-ICR MS offers exceptional prospects for the analysis of complex mixtures such as petroleum, carbohydrates, lipids, and a variety of other biological samples.

Acknowledgments

CEC and CL acknowledge financial support from the National Institutes of Health via grants P41 GM104603 and S10 RR025082.

Appendix

Acquisition Parameters:

| Low Resolution Tune Mix |

High Resolution Tune Mix |

High Resolution Ubiquitin |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Pressure at Funnel Entrance | 2.6 mbar | 3.1 mbar | 3.1 mbar |

| Pressure in P2 | 1.4 mbar | 1.4 mbar | 1.4 mbar |

| TIMS Start Voltage (V) | −200 | −195 | −160 |

| TIMS End Voltage (V) | −50 | −75 | −80 |

| TIMS Ramp Time (ms) | 50 | 125 | 125 |

| TIMS Ramp Speed (V/ms) | 3 | 0.96 | 0.64 |

| TIMS ion accumulation time | 10 | 25 | 50 |

| Number of TIMS accumulations in collision cell | 20 | 40 | 40 |

| TIMS Gate Width (ms) | 0.5 | 1 | 1 |

| TIMS Gate Shift (ms) | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Number of Averaged Mass Spectra | 250 | 250 | 250 |

| Total Experiment Time (s) | 450 | 1650 | 1900 |

References

- 1.McDaniel E, Martin D, Barnes W. Drift tube-mass spectrometer for studies of low-energy ion-molecule reactions. Rev Sci Instrum. 1962;33:2. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ewing RG, Atkinson DA, Eiceman G, Ewing G. A critical review of ion mobility spectrometry for the detection of explosives and explosive related compounds. Talanta. 2001;54:515. doi: 10.1016/s0039-9140(00)00565-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McAfee KBJ, Edelson D. Identification and Mobility of Ions in a Townsend Discharge by Time-resolved Mass Spectrometry. Proceedings of the Physical Society. 1963;81:382. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brocker ER, Anderson SE, Northrop BH, Stang PJ, Bowers MT. Structures of Metallosupramolecular Coordination Assemblies Can Be Obtained by Ion Mobility Spectrometry- Mass Spectrometry. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:13486. doi: 10.1021/ja105702y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forsythe JG, Stow SM, Nefzger H, Kwiecien NW, May JC, McLean JA, Hercules DM. Structural characterization of methylenedianiline regioisomers by ion mobility-mass spectrometry, tandem mass spectrometry, and computational strategies: I. Electrospray spectra of 2-ring isomers. Anal Chem. 2014;86:4362. doi: 10.1021/ac5001652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gidden J, Bowers MT, Jackson AT, Scrivens JH. Gas-phase conformations of cationized poly (styrene) oligomers. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2002;13:499. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(02)00367-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoskins JN, Trimpin S, Grayson SM. Architectural differentiation of linear and cyclic polymeric isomers by ion mobility spectrometry-mass spectrometry. Macromolecules. 2011;44:6915. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trimpin S, Clemmer DE. Ion mobility spectrometry/mass spectrometry snapshots for assessing the molecular compositions of complex polymeric systems. Anal Chem. 2008;80:9073. doi: 10.1021/ac801573n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fernandez-Lima FA, Becker C, McKenna AM, Rodgers RP, Marshall AG, Russell DH. Petroleum crude oil characterization by IMS-MS and FTICR MS. Anal Chem. 2009;81:9941. doi: 10.1021/ac901594f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clemmer DE, Shelimov KB, Jarrold MF. Gas-phase self-assembly of endohedral metallofullerenes. 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hunter J, Fye J, Jarrold M, Bower J. Structural transitions in size-selected germanium cluster ions. Phys Rev Lett. 1994;73:2063. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.73.2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Servage KA, Silveira JA, Fort KL, Russell DH. Evolution of Hydrogen-Bond Networks in Protonated Water Clusters H+ (H2O) n (n= 1 to 120) Studied by Cryogenic Ion Mobility-Mass Spectrometry. The journal of physical chemistry letters. 2014;5:1825. doi: 10.1021/jz500693k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Von Helden G, Gotts NG, Bowers MT. Experimental evidence for the formation of fullerenes by collisional heating of carbon rings in the gas phase. Nature. 1993;363:60. [Google Scholar]

- 14.von Helden G, Wyttenbach T, Bowers MT. Conformation of macromolecules in the gas phase: use of matrix-assisted laser desorption methods in ion chromatography. Science. 1995;267:1483. doi: 10.1126/science.267.5203.1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allen SJ, Schwartz AM, Bush MF. Effects of polarity on the structures and charge states of native-like proteins and protein complexes in the gas phase. Anal Chem. 2013;85:12055. doi: 10.1021/ac403139d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bernstein SL, Dupuis NF, Lazo ND, Wyttenbach T, Condron MM, Bitan G, Teplow DB, Shea J-E, Ruotolo BT, Robinson CV. Amyloid-β protein oligomerization and the importance of tetramers and dodecamers in the aetiology of Alzheimer's disease. Nature Chemistry. 2009;1:326. doi: 10.1038/nchem.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bleiholder C, Do TD, Wu C, Economou NJ, Bernstein SS, Buratto SK, Shea J-E, Bowers MT. Ion mobility spectrometry reveals the mechanism of amyloid formation of Aβ (25–35) and its modulation by inhibitors at the molecular level: epigallocatechin gallate and scyllo-inositol. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:16926. doi: 10.1021/ja406197f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bleiholder C, Dupuis NF, Wyttenbach T, Bowers MT. Ion mobility–mass spectrometry reveals a conformational conversion from random assembly to β-sheet in amyloid fibril formation. Nature chemistry. 2011;3:172. doi: 10.1038/nchem.945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen L, Chen S-H, Russell DH. An experimental study of the solvent-dependent self-assembly/disassembly and conformer preferences of gramicidin A. Anal Chem. 2013;85:7826. doi: 10.1021/ac401370t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clemmer DE, Hudgins RR, Jarrold MF. Naked protein conformations: cytochrome c in the gas phase. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:10141. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dwivedi P, Wu P, Klopsch SJ, Puzon GJ, Xun L, Hill HH., Jr Metabolic profiling by ion mobility mass spectrometry (IMMS) Metabolomics. 2008;4:63. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hall Z, Politis A, Bush MF, Smith LJ, Robinson CV. Charge-state dependent compaction and dissociation of protein complexes: insights from ion mobility and molecular dynamics. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:3429. doi: 10.1021/ja2096859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hines KM, Ashfaq S, Davidson JM, Opalenik SR, Wikswo JP, McLean JA. Biomolecular signatures of diabetic wound healing by structural mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2013;85:3651. doi: 10.1021/ac303594m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu X, Valentine SJ, Plasencia MD, Trimpin S, Naylor S, Clemmer DE. Mapping the human plasma proteome by SCX-LC-IMS-MS. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2007;18:1249. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2007.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McLean JA, Ruotolo BT, Gillig KJ, Russell DH. Ion mobility–mass spectrometry: a new paradigm for proteomics. Int J Mass spectrom. 2005;240:301. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Papadopoulos G, Svendsen A, Boyarkin OV, Rizzo TR. Conformational Distribution of Bradykinin [bk+ 2 H] 2+ Revealed by Cold Ion Spectroscopy Coupled with FAIMS. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2012;23:1173. doi: 10.1007/s13361-012-0384-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pierson NA, Chen L, Russell DH, Clemmer DE. Cis–trans isomerizations of proline residues are key to bradykinin conformations. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:3186. doi: 10.1021/ja3114505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pierson NA, Chen L, Valentine SJ, Russell DH, Clemmer DE. Number of solution states of bradykinin from ion mobility and mass spectrometry measurements. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:13810. doi: 10.1021/ja203895j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Politis A, Park AY, Hall Z, Ruotolo BT, Robinson CV. Integrative modelling coupled with ion mobility mass spectrometry reveals structural features of the clamp loader in complex with single-stranded DNA binding protein. J Mol Biol. 2013;425:4790. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ruotolo BT, Giles K, Campuzano I, Sandercock AM, Bateman RH, Robinson CV. Evidence for macromolecular protein rings in the absence of bulk water. Science. 2005;310:1658. doi: 10.1126/science.1120177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schenk ER, Mendez V, Landrum JT, Ridgeway ME, Park MA, Fernandez-Lima F. Direct observation of differences of carotenoid polyene chain cis/trans isomers resulting from structural topology. Anal Chem. 2014;86:2019. doi: 10.1021/ac403153m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Silveira JA, Fort KL, Kim D, Servage KA, Pierson NA, Clemmer DE, Russell DH. From solution to the gas phase: stepwise dehydration and kinetic trapping of Substance P reveals the origin of peptide conformations. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:19147. doi: 10.1021/ja4114193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Uetrecht C, Barbu IM, Shoemaker GK, van Duijn E, Heck AJ. Interrogating viral capsid assembly with ion mobility–mass spectrometry. Nature chemistry. 2011;3:126. doi: 10.1038/nchem.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shaffer SA, Tang K, Anderson GA, Prior DC, Udseth HR, Smith RD. A novel ion funnel for focusing ions at elevated pressure using electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 1997;11:1813. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang K, Shvartsburg AA, Lee H-N, Prior DC, Buschbach MA, Li F, Tolmachev AV, Anderson GA, Smith RD. High-sensitivity ion mobility spectrometry/mass spectrometry using electrodynamic ion funnel interfaces. Anal Chem. 2005;77:3330. doi: 10.1021/ac048315a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wyttenbach T, Kemper PR, Bowers MT. Design of a new electrospray ion mobility mass spectrometer. Int J Mass spectrom. 2001;212:13. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fernandez-Lima F, Kaplan DA, Suetering J, Park MA. Gas-phase separation using a trapped ion mobility spectrometer. Int J Ion Mobil Spectrom. 2011;14:93. doi: 10.1007/s12127-011-0067-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hernandez DR, DeBord JD, Ridgeway ME, Kaplan DA, Park MA, Fernandez-Lima F. Ion dynamics in a trapped ion mobility spectrometer. Analyst. 2014;139:1913. doi: 10.1039/c3an02174b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Silveira JA, Ridgeway ME, Park MA. High resolution trapped ion mobility spectrometery of peptides. Anal Chem. 2014;86:5624. doi: 10.1021/ac501261h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ridgeway ME, Silveira JA, Meier JE, Park MA. Microheterogeneity within conformational states of ubiquitin revealed by high resolution trapped ion mobility spectrometry. The Analyst. 2015;140:6964. doi: 10.1039/c5an00841g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Donohoe GC, Maleki H, Arndt JR, Khakinejad M, Yi J, McBride C, Nurkiewicz TR, Valentine SJ. A New Ion Mobility–Linear Ion Trap Instrument for Complex Mixture Analysis. Anal Chem. 2014;86:8121. doi: 10.1021/ac501527y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tang X, Bruce JE, Hill HH. Design and performance of an atmospheric pressure ion mobility Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometer. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2007;21:1115. doi: 10.1002/rcm.2928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zucker SM, Lee S, Webber N, Valentine SJ, Reilly JP, Clemmer DE. An ion mobility/ion trap/photodissociation instrument for characterization of ion structure. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2011;22:1477. doi: 10.1007/s13361-011-0179-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Clowers BH, Siems WF, Yu Z, Davis AL. A two-phase approach to fourier transform ion mobility time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Analyst. 2015;140:6862. doi: 10.1039/c5an00941c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Prost SA, Crowell KL, Baker ES, Ibrahim YM, Clowers BH, Monroe ME, Anderson GA, Smith RD, Payne SH. Detecting and removing data artifacts in hadamard transform ion mobility-mass spectrometry measurements. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2014;25:2020. doi: 10.1007/s13361-014-0895-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Benigni P, Marin R, Fernandez-Lima F. Towards unsupervised polyaromatic hydrocarbons structural assignment from SA-TIMS –FTMS data. Int J Ion Mobil Spectrom. 2015;18:151. doi: 10.1007/s12127-015-0175-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Benigni P, Thompson CJ, Ridgeway ME, Park MA, Fernandez-Lima F. Targeted high-resolution ion mobility separation coupled to ultrahigh-resolution mass spectrometry of endocrine disruptors in complex mixtures. Anal Chem. 2015;87:4321. doi: 10.1021/ac504866v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meier F, Beck S, Grassl N, Lubeck M, Park MA, Raether O, Mann M. Parallel accumulation–serial fragmentation (PASEF): Multiplying sequencing speed and sensitivity by synchronized scans in a trapped ion mobility device. Journal of proteome research. 2015;14:5378. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b00932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Park MA, Park N, Meier J, Ridgeway ME, Silveira JA. Opportunity Ion Storage: Electric Field Gradient Optimization for Complex Mixture Analysis by Trapped Ion Mobility Spectrometry. in American Society of Mass Spectrometry. Missouri: St. Louis; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Michelmann K, Silveira JA, Ridgeway ME, Park MA. Fundamentals of trapped ion mobility spectrometry. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2014;26:14. doi: 10.1007/s13361-014-0999-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Silveira JA, Michelmann K, Ridgeway ME, Park MA. Fundamentals of Trapped Ion Mobility Spectrometry Part II: Fluid Dynamics. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2016:1. doi: 10.1007/s13361-015-1310-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Merenbloom SI, Flick TG, Williams ER. How hot are your ions in TWAVE ion mobility spectrometry? J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2012;23:553. doi: 10.1007/s13361-011-0313-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Purves RW, Barnett DA, Ells B, Guevremont R. Investigation of bovine ubiquitin conformers separated by high-field asymmetric waveform ion mobility spectrometry: cross section measurements using energy-loss experiments with a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2000;11:738. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(00)00136-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li J, Taraszka JA, Counterman AE, Clemmer DE. Influence of solvent composition and capillary temperature on the conformations of electrosprayed ions: unfolding of compact ubiquitin conformers from pseudonative and denatured solutions. Int J Mass spectrom. 1999;185:37. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Myung S, Badman ER, Lee YJ, Clemmer DE. Structural transitions of electrosprayed ubiquitin ions stored in an ion trap over~ 10 ms to 30 s. The Journal of Physical Chemistry A. 2002;106:9976. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu FC, Kirk SR, Bleiholder C. On the Structural Denaturation of Biological Analytes in Trapped Ion Mobility Spectrometry - Mass Spectrometry. Analyst. 2016 doi: 10.1039/c5an02399h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wyttenbach T and Bowers MT. Structural Stability from Solution to the Gas Phase: Native Solution Structure of Ubiquitin Survives Analysis in a Solvent-Free Ion Mobility–Mass Spectrometry Environment. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2011;115:12266. doi: 10.1021/jp206867a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]