Case Presentation

A 79 year-old gentleman with a new diagnosis of locally advanced prostate cancer is referred to the Cardio-Oncology clinic for optimization of his cardiovascular (CV) health after treatment with degarelix, a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) receptor antagonist, for his prostate cancer. Two years ago, he had a myocardial infarction resulting in placement of a drug eluting stent in his proximal left anterior descending artery. He has had no recurrent symptoms, but lives a sedentary lifestyle. Electrocardiogram (EKG) showed normal sinus rhythm. His most recent echocardiogram demonstrated a structurally normal heart with normal left ventricular ejection fraction. He takes aspirin 81 mg daily. He has hypertension, with the last recorded blood pressure of 160/90 mmHg, and is currently treated with metoprolol 25 mg twice daily and lisinopril 40 mg daily. He has diabetes treated with glipizide 10 mg daily and his last HbA1c level was 7.4 mg/dl. He is also treated with pravastatin 40 mg daily and low density lipoprotein (LDL) was 120 mg/dl at his most recent clinic visit. He continues to smoke one pack of cigarettes daily, and his body mass index (BMI) is 30 kg/m2.

Overview

Prostate cancer is the most common non-cutaneous cancer diagnosed in men in the United States, and is the second leading cause of cancer death1. In 2015, there are an estimated three million prostate cancer survivors in the United States; this number will reach four million in the next decade1. Due to the indolent, slowly progressive disease course of prostate cancer, and advances in early detection and effective treatment, non-cancer related deaths are the most common causes of mortality2. In particular, given the prevalence of pre-existing and new cardiovascular disease (CVD), ischemic heart disease is the most common non-cancer cause of death in prostate cancer patients2.

Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) is the primary systemic therapy for locally advanced and metastatic prostate cancer, with as many as 50% of patients receiving ADT at some point during their disease course3. Several observational studies suggest a link between ADT and increased risk of CV events4. In 2010, the American Heart Association released a statement acknowledging the possible association between ADT and adverse CV events.5 More recently, the Prostate Cancer Survivorship Care Guidelines by American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) endorsed evaluation and screening of CV risk factors in men receiving ADT6. Given the growing population of prostate cancer patients and survivors receiving ADT, it is crucial for practicing physicians to better understand ADT and the possible association with CVD.

Mechanisms of ADT

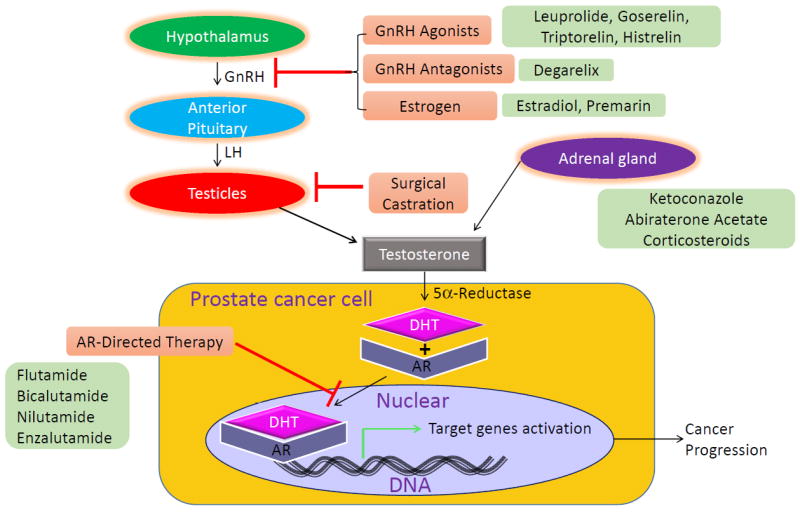

After synthesis in the testes, androgens (primarily testosterone) circulate in the serum and activate androgen receptor (AR) in target tissues including muscle, adipose tissue and prostate cancer cells. After activation by its ligand, AR induces a number of genes that are collectively referred to as the “androgen response”, driving prostate cancer growth, among other things (Figure 1). Thus, the major goal of ADT in the treatment of prostate cancer is to reduce serum testosterone levels to < 50 ng/dl, with many men achieving levels < 20 ng/dl3.

Figure 1.

Schematic of hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis and sites of action of anti-androgen therapies. AR: Androgen receptor, DHT: Dihydrotestosterone, GnRH: Gonadotropin releasing hormone, LH: Luteinizing hormone.

ADT can be achieved by surgical or pharmacologic castration, via bilateral orchiectomies or GnRH agonist or antagonist treatment (Table 1). GnRH agonists ultimately down-regulate luteinizing hormone (LH) secretion from anterior pituitary after causing an initial surge of LH levels in the first weeks of treatment (Figure 1). In contrast, GnRH antagonists bind GnRH receptors on the anterior pituitary gland and inhibit LH release, avoiding a surge in LH and potential associated complications. Diminished LH levels suppress androgen synthesis by the testes (Figure 1). Anti-androgens work at the level of the prostate cancer cells to directly block activation of the androgen receptor, and can be used to augment the effectiveness of GnRH agonist or antagonist suppression of AR activation (Figure 1).

Table 1.

List of anti-androgen drugs. GnRH: Gonadotropin releasing hormone.

| GnRH Agonists | GnRH Antagonists | Anti-Androgens | Adrenal Androgen Inhibitors | Estrogens |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leuprolide | Degarelix | Flutamide | Ketoconazole | |

| Goserelin | Bicalutamide | Corticosteroids | Estradiol | |

| Triptorelin | Nilutamide | |||

| Histrelin | Enzalutamide | Premarin | ||

| Abiraterone Acetate |

Effects and Pathophysiology of ADT on the CV System

The effects of ADT on the CV system are largely driven by indirect modifications of CV risk factors. Most data, derived predominantly from GnRH agonists (eg. leuprolide, goserelin) demonstrate an association between ADT and increased LDL and triglyceride levels, increased fat and decreased lean body mass, increased insulin resistance and decreased glucose tolerance, and a general metabolic state similar to the metabolic syndrome (though with heightened high density lipoprotein (HDL) levels). These changes can accelerate systemic atherosclerosis and predispose to coronary artery disease (CAD). ADT has also been associated with both arterial and venous thromboembolic events, including deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary emboli, arterial thrombosis and stroke3, 4. No clear effect of ADT on blood pressure has been delineated. Indeed, counterintuitively, ADT improved vascular endothelial function leaving the mechanism of atherogenesis unclear7. The effects of ADT on various CV risk parameters are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Pathophysiology of Adverse Cardiovascular Effects of Gonadotropic Releasing Hormone Agonists. LDL: Low density lipoprotein, HDL: High density lipoprotein.

| Indirect Effects | Direct Effects | Low Testosterone |

|---|---|---|

| ↑ Fat mass | ? ↓ Cardiac contractility | ↓ Vasodilation |

| ↓ Lean body mass | ↑ T-Cell activation and destabilization of fibrous cap/plaque rupture | ↓ HDL |

| ↑ Insulin resistance / Hyperinsulinemia | ↑ Visceral Obesity | |

| ↑ LDL, ↑ HDL and ↑ Triglycerides | ↑ Prothrombotic state | |

| ↑ Diabetes mellitus | ||

| ↑ Metabolic syndrome | ||

| ↑ Endothelial dysfunction | ||

| ↑ Arterial wall thickness |

Interestingly, there may be differences between GnRH agonists and antagonists regarding CV risk. GnRH antagonists suppress both luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) as opposed to GnRH agonists, which primarily suppress LH. This might influence how these molecules affect endothelial function, lipid metabolism, and fat accumulation. Interestingly, a recent pooled analysis of six randomized controlled trials found that among men with pre-existing CVD, the risk of cardiac events was twice as high among men treated with a GnRH agonist as among men treated with GnRH antagonists8. Although hypothesis generating, prospective studies are necessary to provide more definitive data regarding the type of ADT to use or to avoid for men with the highest CV risk.

Despite well-known adverse effects on CV risk factors, and a possible association between ADT exposure and increased CV morbidity, no single prospective study has definitively established that ADT exposure increases the risk of CVD or CV mortality. However, a preponderance of the evidence suggests that men with pre-existing CVD including a history of congestive heart failure or myocardial infarction, are at the highest risk of CV events with ADT exposure, especially during the first 6 months of ADT initiation, and close follow-up is warranted4.

Management

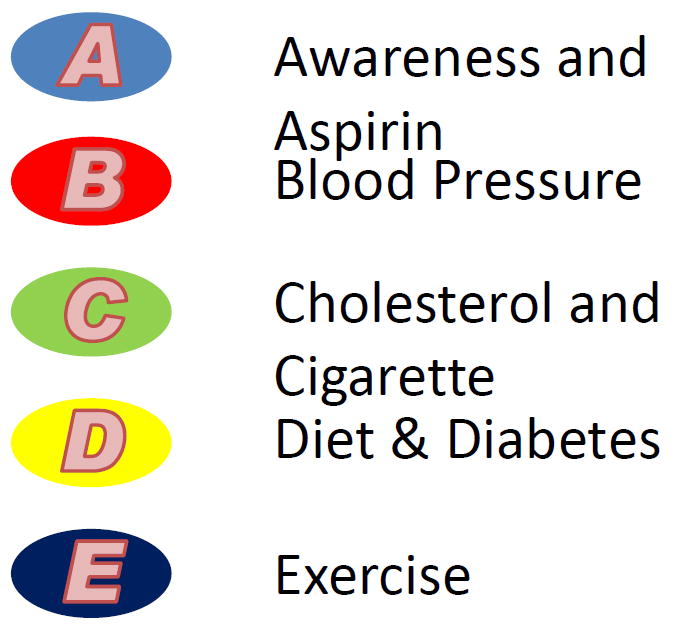

We have developed the “ABCDE” (Table 2, Figure 2) paradigm to control CV risk factors in cancer survivors9. Here, we have adapted this for prostate cancer survivors in the absence of formal guidelines specifically for the prevention and management of CVD in patients on ADT.

Figure 2.

“ABCDE” algorithm for prostate cancer survivors.

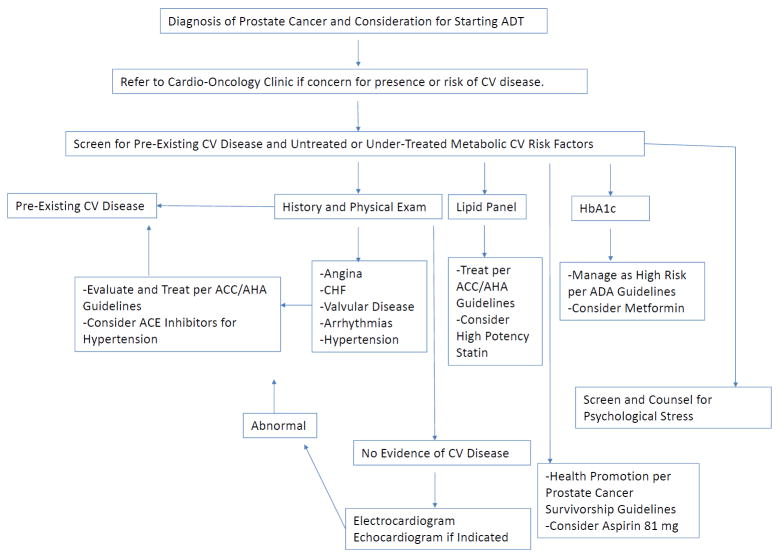

Awareness and Aspirin

Increasing awareness of patients about signs and symptoms of CVD, and screening for undiagnosed metabolic and CV risk factors, is essential during an initial clinic visit with a primary care provider or cardio-oncologist (Figure 3). Evidence suggests that in patients diagnosed with high-risk prostate cancer, aspirin may be associated with lower prostate cancer specific mortality (HR=0.60; 95% CI, 0.37 to 0.97)10. Though this has yet to be validated in other populations, it is possible that select patients may benefit from aspirin for primary and secondary prevention of CVD, and possibly through reduced cancer related mortality.

Figure 3.

Algorithm to manage patients on androgen deprivation therapy in the Cardio-Oncology clinic. ADT: Androgen Deprivation Therapy, CV: Cardiovascular, ACC/AHA: American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association, CHF:Congestive Heart Failure, ACE: Angiotensin Converting Enzyme, ADA: American Diabetes Association.

Blood Pressure

Hypertension is a known CV risk factor, and a treatment goal is attaining BP <140/90. We recommend angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors as first choice agents due to the mortality benefit in patients with diabetes and CVD, as well as possibly improved outcomes in cancer patients, including those with prostate cancer (delayed prostate specific antigen failure)11.

Cholesterol and Cigarettes

Hyperlipidemia should be treated with high intensity statin therapy independent of goal LDL levels, especially in the presence of diabetes or CVD. Tobacco products should be completely avoided, especially since smoking is associated as an independent and negative prognostic factor for both prostate cancer specific and all-cause mortality in prostate cancer patients12.

Diabetes, Diet and Exercise

As glycemic control can worsen with ADT, frequent monitoring of blood glucose and appropriate adjustment of diabetes therapy is recommended. Metformin is the preferred agent for treatment of diabetes in this population due to its favorable effects on metabolic syndrome. The Prostate Cancer Survivorship Guidelines from ASCO6 recommend health promotion by encouraging maintenance of a healthy weight through caloric restriction and regular physical activity. In terms of the latter, there is growing evidence base supporting the efficacy of structured exercise training (i.e., endurance training, resistance training, or the combination) as an effective strategy to off-set and/or attenuate some of the common side-effects of ADT13. National guidelines recommend that patients with cancer should participate in at least 150 min of moderate exercise (eg, brisk walking, light swimming) or 75 min per week of vigorous exercise (eg, jogging, running, hard swimming)13. American College of Sports Medicine guidelines recommend that patients with cancer should participate in at least 150 min of moderate exercise (eg, brisk walking, light swimming) or 75 min per week of vigorous exercise (eg, jogging, running, hard swimming)13. However, this recommendation is a long-term goal and is not advised as an initial prescription for most sedentary patients either during or immediately after ADT. A generalized approach to individualized exercise prescription is available14. Dietary goals include increasing fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, decreasing saturated fats, and consuming adequate vitamin D (≥ 600 IU/day) and calcium (not exceeding 1200 mg/day). Alcohol should be limited to ≤ two drinks/day. We recommend lifestyle modification counseling at follow-up clinic visits. In addition, as cancer diagnosis and treatment is a significant source of psychological stress, a factor independently associated with adverse CV events, screening and counseling to manage stress may also be helpful15(Figure 3).

ADT may prolong QTc, and a baseline EKG should be obtained. If initial screening reveals evidence of congestive heart failure, valvular or other structural heart disease, an echocardiogram should be obtained.

The physician’s focus should be to optimize the CV and metabolic risk profile as much as feasible over the course of survivorship. Once ADT is initiated, we recommend close follow-up of at least every three months during the first year of therapy.

Case Conclusion

A detailed discussion about CV risks of ADT was undertaken. Our patient was counseled to quit smoking, adopt the above recommended diet and exercise regimen. An EKG was obtained which revealed normal sinus rhythm. His statin was changed to atorvastatin 80 mg daily, and metformin 500 mg twice daily was substituted for glipizide for his diabetes. The dose of metoprolol was increased to 50 mg BID and he was advised to maintain a blood pressure diary at home. He was screened for stress and offered counseling. He was scheduled for a follow-up visit in one month and handed a pamphlet with the new modified “ABCDE” algorithm (Figure 2).

Table 3.

ABCDE algorithm for prostate cancer survivors. CV: Cardiovascular.

| A | Awareness and Aspirin |

|

| B | Blood Pressure | Goal blood pressure < 140/90 mmHg |

| C | Cholesterol and Cigarettes |

|

| D | Diet and Diabetes |

|

| E | Exercise | 150 minutes per week of moderate intensity physical activity or 75 minutes per week of vigorous exercise. |

Footnotes

Disclosures

Dr. Lee Jones is the Cofounder of Exercise by Science, Inc and receives research grants from the National Cancer Institute and AKTIV Against Cancer. Dr. Josh Beckman is a consultant for Merck, Novartis, BMS (Bristol-Myers Squibb) and AstraZeneca. He receives grant support from BMS. Dr, David Penson receives research support from Medivation/Astellas. Dr. Alicia Morgans is a consultant for Dendreon and Myriad. Dr. Javid Moslehi is a consultant for Novartis, Pfizer, Takeda, ARIAD, BMS and Acceleron.

References

- 1.DeSantis CE, Lin CC, Mariotto AB, Siegel RL, Stein KD, Kramer JL, Alteri R, Robbins AS, Jemal A. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:252–71. doi: 10.3322/caac.21235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Epstein MM, Edgren G, Rider JR, Mucci LA, Adami HO. Temporal trends in cause of death among Swedish and US men with prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:1335–42. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conteduca V, Di Lorenzo G, Tartarone A, Aieta M. The cardiovascular risk of gonadotropin releasing hormone agonists in men with prostate cancer: an unresolved controversy. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013;86:42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nguyen PL, Alibhai SM, Basaria S, D’Amico AV, Kantoff PW, Keating NL, Penson DF, Rosario DJ, Tombal B, Smith MR. Adverse Effects of Androgen Deprivation Therapy and Strategies to Mitigate Them. Eur Urol. 2015;67:825–836. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levine GN, D’Amico AV, Berger P, Clark PE, Eckel RH, Keating NL, Milani RV, Sagalowsky AI, Smith MR, Zakai N American Heart Association Council on Clinical C, Council on E, Prevention tACS and the American Urological A. Androgen-deprivation therapy in prostate cancer and cardiovascular risk: a science advisory from the American Heart Association, American Cancer Society, and American Urological Association: endorsed by the American Society for Radiation Oncology. Circulation. 2010;121:833–40. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Resnick MJ, Lacchetti C, Bergman J, Hauke RJ, Hoffman KE, Kungel TM, Morgans AK, Penson DF. Prostate cancer survivorship care guideline: american society of clinical oncology clinical practice guideline endorsement. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1078–85. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.60.2557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nguyen PL, Jarolim P, Basaria S, Zuflacht JP, Milian J, Kadivar S, Graham PL, Hyatt A, Kantoff PW, Beckman JA. Androgen deprivation therapy reversibly increases endothelium-dependent vasodilation in men with prostate cancer. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.001914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Albertsen PC, Klotz L, Tombal B, Grady J, Olesen TK, Nilsson J. Cardiovascular morbidity associated with gonadotropin releasing hormone agonists and an antagonist. Eur Urol. 2014;65:565–73. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Montazeri K, Unitt C, Foody JM, Harris JR, Partridge AH, Moslehi J. ABCDE steps to prevent heart disease in breast cancer survivors. Circulation. 2014;130:e157–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.008820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobs EJ, Newton CC, Stevens VL, Campbell PT, Freedland SJ, Gapstur SM. Daily aspirin use and prostate cancer-specific mortality in a large cohort of men with nonmetastatic prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3716–22. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.8875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mc Menamin UC, Murray LJ, Cantwell MM, Hughes CM. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers in cancer progression and survival: a systematic review. Cancer Causes Control. 2012;23:221–30. doi: 10.1007/s10552-011-9881-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murta-Nascimento C, Romero AI, Sala M, Lorente JA, Bellmunt J, Rodero NJ, Lloreta J, Hospital A, Buron A, Castells X, Macia F. The effect of smoking on prostate cancer survival: a cohort analysis in Barcelona. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2015;24:335–9. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harrison MR, Jones LW. Exercise as treatment for androgen deprivation therapy-associated physical dysfunction: ready for prime time? Eur Urol. 2014;65:873–4. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones LW, Eves ND, Peppercorn J. Pre-exercise screening and prescription guidelines for cancer patients. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:914–6. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70184-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen BE, Edmondson D, Kronish IM. State of the Art Review: Depression, Stress, Anxiety, and Cardiovascular Disease. Am J Hypertens. 2015 doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpv047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]