Abstract

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is mainly associated with myosin, heavy chain 7 (MYH7) and myosin binding protein C, cardiac (MYBPC3) mutations. In order to better explain the clinical and genetic heterogeneity in HCM patients, in this study, we implemented a target-next generation sequencing (NGS) assay. An Ion AmpliSeq™ Custom Panel for the enrichment of 19 genes, of which 9 of these did not encode thick/intermediate and thin myofilament (TTm) proteins and, among them, 3 responsible of HCM phenocopy, was created. Ninety-two DNA samples were analyzed by the Ion Personal Genome Machine: 73 DNA samples (training set), previously genotyped in some of the genes by Sanger sequencing, were used to optimize the NGS strategy, whereas 19 DNA samples (discovery set) allowed the evaluation of NGS performance. In the training set, we identified 72 out of 73 expected mutations and 15 additional mutations: the molecular diagnosis was achieved in one patient with a previously wild-type status and the pre-excitation syndrome was explained in another. In the discovery set, we identified 20 mutations, 5 of which were in genes encoding non-TTm proteins, increasing the diagnostic yield by approximately 20%: a single mutation in genes encoding non-TTm proteins was identified in 2 out of 3 borderline HCM patients, whereas co-occuring mutations in genes encoding TTm and galactosidase alpha (GLA) altered proteins were characterized in a male with HCM and multiorgan dysfunction. Our combined targeted NGS-Sanger sequencing-based strategy allowed the molecular diagnosis of HCM with greater efficiency than using the conventional (Sanger) sequencing alone. Mutant alleles encoding non-TTm proteins may aid in the complete understanding of the genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity of HCM: co-occuring mutations of genes encoding TTm and non-TTm proteins could explain the wide variability of the HCM phenotype, whereas mutations in genes encoding only the non-TTm proteins are identifiable in patients with a milder HCM status.

Keywords: Ion Torrent Personal Genome Machine, borderline HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, next-generation sequencing, thick/intermediate and thin myofilament proteins, non-sarcomeric genes, genetic heterogeneity, phenotypic heterogeneity

Introduction

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), classically defined as the presence of idiopathic left ventricular hypertrophy, is the most common heritable cardiovascular disease (affecting at least 1 in 500 individuals); it is typically transmitted in an autosomal dominant pattern (1–3); however, sporadic cases associated with de novo mutations (1,4) and patients with maternally-inherited HCM (5,6) have also been reported. HCM is recognized as an important cause of sudden cardiac death (SCD), heart failure and embolic stroke secondary to atrial fibrillation (2).

At present, Online Mendelian Inherithance in Man (OMIM) classifies 25 different HCM phenotypes (http://omim.org/phenotypicSeries/PS192600) that are associated with as many different mutant genes, mostly encoding thick/intermediate and thin myofilament (TTm) proteins of the sarcomere. Disease-causing mutations in myosin, heavy chain 7 (MYH7) and myosin binding protein C, cardiac (MYBPC3) genes, encoding myofilament proteins, represent approximately 70% of >1,400 pathogenic alleles that have been characterized in HCM patients by using Sanger sequencing (2). Pathogenic alleles that do not encode for TTm proteins have also been identified in some HCM patients (7–12). Mutations in the genes, galactosidase alpha (GLA), lysosome-associated membrane protein 2 (LAMP2), and protein kinase AMP-activated non-catalytic subunit gamma 2 (PRKAG2), are responsible for distinct metabolic storage disorders with a clinical presentation and pattern of left-ventricular hypertrophy similar to HCM (1,3,13).

However, pathogenic alleles are not identified in 28–40% of HCM patients with a family history of HCM and 50–90% of sporadic HCM cases (13,14). On the other hand, 5–10% of HCM patients carry more than one mutation affecting one or more different genes (15); these complex genotypes are usually identified in patients with severe left ventricular hypertrophy (16), or with end-stage HCM (17) and in patients with severe manifestations of the disease, including advanced heart failure symptoms and sudden death (1,14).

In addition, the broad genetic and allelic heterogeneity can also be associated with a highly variable clinical phenotype, ranging from asymptomatic forms to sudden cardiac death (1,13), even within the same family and amongst family members that share the same pathogenic allele (18,19).

The conventional Sanger sequencing of single amplicons of sarcomeric genes is labor intensive, time consuming and expensive, showing in a large number of patients a negative test or a positive test, but associated with a low predictive clinical outcome. In consideration of these limitations, it is reasonable to adopt the massively parallel sequencing ability of the Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) technologies to decrease run times, lower the costs, use smaller amounts of genomic DNA (20) and, analyzing a larger number of genes, better decipher the relationship between genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity (21,22). In this context, the NGS methodology is replacing the conventional technology, in particular for the diagnosis of genetic disorders with high genetic heterogeneity that involve the screening of several genes or few genes with large coding region (23,24).

In this study, we used the NGS methodology, applied to the molecular characterization of HCM patients, to determine whether the screening of additional genes encoding non-TTm proteins may contribute to the better clarification of the relationship between the phenotypic and genotypic heterogeneity of HCM.

Patients and methods

Patients

All patients [n=92; mean age, 44.5 (±18.7) years; age range, 2–78 years] gave their informed consent to the study that was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. The subjects were recruited between 2007 and 2015 from Italian Cardiology Units and addressed to our Human Genetics Laboratory for molecular diagnosis of HCM. The clinical diagnosis of primary HCM was based on medical history, a physical examination and on the echocardiographic demonstration of a hypertrophied left ventricle (LV) that could not be explained by another cardiac or systemic disease. In adults, a maximal LV wall thickness (LVWT) ≥15 mm, or the equivalent relative to the body surface area in children, was considered the determining criterion for HCM; the maximal LVWT between 10 and 14 mm, in conjunction with other features (i.e., family history, electrocardiogram abnormalities) prompted the diagnosis of borderline HCM (25,26).

The phenocopy of HCM was suspected in the presence of multiorgan involvement. In these cases, a multidisciplinary clinical approach was adopted for the final diagnosis (27).

The genomic DNA of each patient was extracted from peripheral leukocytes, using QIAsymphony S (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Among the 92 DNA samples, 73 were used as a training set to optimize the performance of NGS technology; these DNA samples were already genotyped by the Sanger sequencing of 6 genes encoding TTm proteins [MYH7, MYBPC3, troponin T2, cardiac type (TNNT2), actin, alpha, cardiac muscle 1 (ACTC1), tropomyosin 1 (alpha) (TPM1) and troponin I3, cardiac type (TNNI3)] (1,3) and, where appropriate, another 2 genes encoding myofilament proteins [myosin light chain (MYL)2 and MYL3] (1,3), or 3 genes (GLA, LAMP2 and PRKAG2) responsible for rare metabolic disorders (1,3,13), were analyzed. This series has 63 DNA samples with mutant genotypes and 10 DNA samples with no previously identified mutations.

Another group of 19 DNA samples was adopted as the discovery set to evaluate the performance of NGS methodology in clinical routine HCM testing.

The clinical parameters (age at onset of HCM, LVWT, automatic implantable cardioverter defibrillator, family history of HCM/sudden cardiac death, left ventricular ejection fraction and other medical issues) were carefully reviewed for patients belonging at the discovery set and for those of the training set that, after NGS analysis, showed additional mutations in genes originally not analyzed by Sanger sequencing. Among these patients, of which 14 were males and 12 were female, the mean age at onset was 33.6 (±19.0) years, with an age range of 1–72 years; the mean LVWT was 18.7 (±6.6) mm and ranged from 10 to 34 mm; the mean LVEF (%) was 59.8 (±10.4).

Gene panel design

To implement the diagnostic genetic testing for HCM patients using NGS technology, in addition to the 11 genes previously screened, after analyzing the literature, we included additional 8 genes deemed most plausibly involved in the HCM phenotype. Among these, 2 genes encode myofilament proteins [thin: troponin C1, slows skeletal and cardiac type (TNNC1); and thick: myosin, heavy chain 6 (MYH6)]; one encodes a protein located in the M-band [myomesin 1 (MYOM 1)] (7); two encode Z-disk constituents [myozenin 2 (MYOZ2) and ankyrin repeat domain 1 (ANKRD1)] (8,9); vinculin (VCL) encodes the main costameric protein (10), calreticulin 3 (CALR3) encodes a Ca2+ sensitive/handling protein (11) and caveolin 3 (CAV3) encodes the major membrane protein of caveolae (12).

An Ion AmpliSeq™ Custom Panel (IACP) for the mutation screening of these 19 genes was designed using the Ion AmpliSeq Designer (IAD) software v.2.0.3. The design included all the coding exons with additional 10 bp of adjacent intronic regions. Overall, it represented approximately 42 kb of the target DNA sequence, i.e., 284 exons and 452 amplicons divided into 2 pools of primers for multiplex PCR.

Library preparation and NGS

DNA libraries were prepared using the Ion Ampliseq™ Library kit 2.0 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA, USA) following the manufacturer's instructions.

Briefly, following quantification with a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 10 ng of genomic DNA was used in the multiplex PCR amplification of each of the 2 primer pools. For each sample, the 2 sets of multiplexed amplicons were subjected to following steps: partial digestion of the primers and amplicon phosphorylation with FuPa reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific), ligation of the barcode adapters and purification by Agencourt® AMPure® XP Reagent (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA).

All the DNA libraries were quantified by the Agilent High Sensitivity DNA kit on a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Milan, Italy) and a Qubit® 2.0 Fluorometer using the dsDNA High Sensitivity assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) before being diluted to a final concentration of 100 pmol/l in low TE; subsequently, 3 µl of each sample were pooled to a final concentration of 100 pmol/l. The final pool was further diluted to a concentration of 12 pmol/l in water and subjected to emulsion PCR and enrichment of Ion Sphere Particles (ISPs) using the Ion Torrent OneTouch™ 2 system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer's instructions; confirmation of template-positive ISPs and validation of enrichment were performed on Qubit® 2.0 Fluorometer using Ion sphere quality control kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific), according to the manufacturer's protocol. Enriched ISPs were loaded on Ion 314 or 316 chips and sequenced on the Ion Torrent Personal Genome Machine (PGM) (both from Thermo Fisher Scientific); the sequencing was performed using the PGM 200 Sequencing kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Bioinformatics analysis

Raw data from PGM sequencing runs were processed using 2 software pipelines, Ion Reporter 4.0 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and the CLC Genomics Workbench software version 6.5 (CLC Bio, Aarhus, Denmark). Sequencing reads were filtered for low-quality reads, trimmed for adapter sequences and tagged as belonging to the specific patient according to the barcode.

Using the spectrum of the expected mutations in the training set, the parameters for variant calling were established to minimize the number of false-positive results and guarantee the characterization of all the true-positive calls; the following filter thresholds were considered: minimum allele frequency for single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) and indel (SNP% ≥20), phred-like quality score of the called variant (Qcall ≥20) and depth of coverage (Depth ≥20).

Coverage assessment was carried out by the Ion Coverage Analysis plug-in v4.0-r77897 and CLC Bio Coverage statistics module. Moreover, alignments were visually inspected with Integrative Genome Viewer (28) to know the depth of analysis of each single nucleotide of the target region and the information concerning the read of the fragments with forward or reverse primer only.

We considered correctly covered, and hence suitable for mutations analysis, only exons (and their adjacent boundary sequences) with a read depth >20 reads (20X) for each targeted nucleotide; in detail, this parameter of coverage was requested for i) the 99% of the target region with respect to 11 genes previously screened in routine molecular diagnosis by Sanger sequencing; ii) the 95% of the target region for the remaining 8 genes.

Filtering approach and putative mutations assignment

To distinguish potential disease-causing mutations from common variants with a minor allele frequency (MAF) ≥1%, the nucleotide alterations were initially filtered against the variations reported in dbSNP138 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/), the HapMap v3.3, the Exome Variant Server (EVS; http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/), the 1000 Genomes Project (www.1000genomes.org) hg19 (patch9) and the Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC; exac.broadinstitute.org).

Nonsense, frameshift, canonical splice site (±2 bp) mutations, together with missense mutations already unequivocally described as associated with the HCM phenotype (or with other forms of cardiomyopathies), and reported in the Human Genome Mutation Database (29) (HGMD, http://www.hgmd.org/; release 2015.4) as disease-causing mutations (DM), were considered as 'pathogenic variants'.

To evaluate the effect on protein function of the missense mutations not described in the literature or annotated in HGMD as DM? (DM of questionable pathological relevance), the in silico prediction of pathogenicity was established by Polyphen2 (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/), Mutation Taster (http://www.mutationtaster.org/) and SIFT human protein (http://sift.jcvi.org/) algorithms. Afterward, we classified these missense mutations either as 'pathogenic variants' when the pathogenic impact was predicted by all algorithms or as 'likely pathogenic variants' when the pathogenic impact was predicted by 2 out of 3 algorithms.

Taking into account the stringent above-mentioned criteria, we evaluated that, in the training set, 67 out of 73 expected mutations were classifiable as 'pathogenic variants', while the remaining 6 were predicted as 'likely pathogenic variants'; of these, 52 mutations were annotated in HGMD.

Sanger sequencing of uncovered regions and validations of putative variants

Using Sanger sequencing, we analyzed the exons classified as uncovered in order to reach the percentage of target region correctly covered; moreover, the new non-synonymous nucleotide variants identified were also confirmed by Sanger sequencing.

In brief, exons containing the nucleotide variants were amplified using Taq Platinum (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) with specific flanking primers and sequenced using Big Dye v3.1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific); fragments of PCR and products of sequencing were purified by Agencourt AMPure XP and CleanSEQ, respectively, on automated station Biomek FX (Beckman Coulter). Sequencing was carried out on 3130 and 3730 ×l automated sequencers (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Data analysis was performed using SeqScape v2.5 software (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

The history of atrial fibrillation between the different groups of patients was compared using Fisher's exact test. A p-value <0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

IACP performance

To verify the theoretical coverage of the 19 genes, all 284 coding exons were analyzed with IAD software: 259 (91.2%) were ascribed to theoretical covered exons. The NGS analysis of the 73 samples (the training set) showed a coverage >20X for each target nucleotide into 253 exons (97.7%) (Table I). The remaining exons were classifiable with unsuitable coverage and therefore were screened by conventional (Sanger) sequencing.

Table I.

List of HCM genes included in the NGS panel and percentage of investigated exons that are correctly profiled.

| Gene | Total | MYH7 | MYBPC3 | TNNT2 | ACTC1 | TPM1 | TNNI3 | MYL2 | MYL3 | GLA | LAMP2 | PRKAG2 | MYH6 | TNNC1 | ANKRD1 | MYOM1 | MYOZ2 | CAV3 | CALR3 | VCL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of exons submitted into 'Ion AmpliSeq Designer' (IAD) | 284 | 38 | 34 | 16 | 6 | 10 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 9 | 16 | 37 | 6 | 9 | 37 | 5 | 2 | 9 | 22 |

| No. of theoretical exons correctly covered by IAD | 259 | 37 | 31 | 16 | 6 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 11 | 29 | 5 | 9 | 36 | 5 | 2 | 7 | 20 |

| Total theoretical exons correctly covered by IAD/total exons submitted into IAD | 259/284 (91.2%) | |||||||||||||||||||

| No. of exons successfully sequenced with coverage >20X for each targeted nucleotide | 253 | 35 | 29 | 15 | 6 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 27 | 6 | 9 | 36 | 5 | 2 | 9 | 21 |

| Total exons successfully sequenced/total exons correctly covered by IAD | 253/259 (97.7%) | |||||||||||||||||||

NGS. next generation sequencing; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; IAD, Ion AmpliSeq Designer.

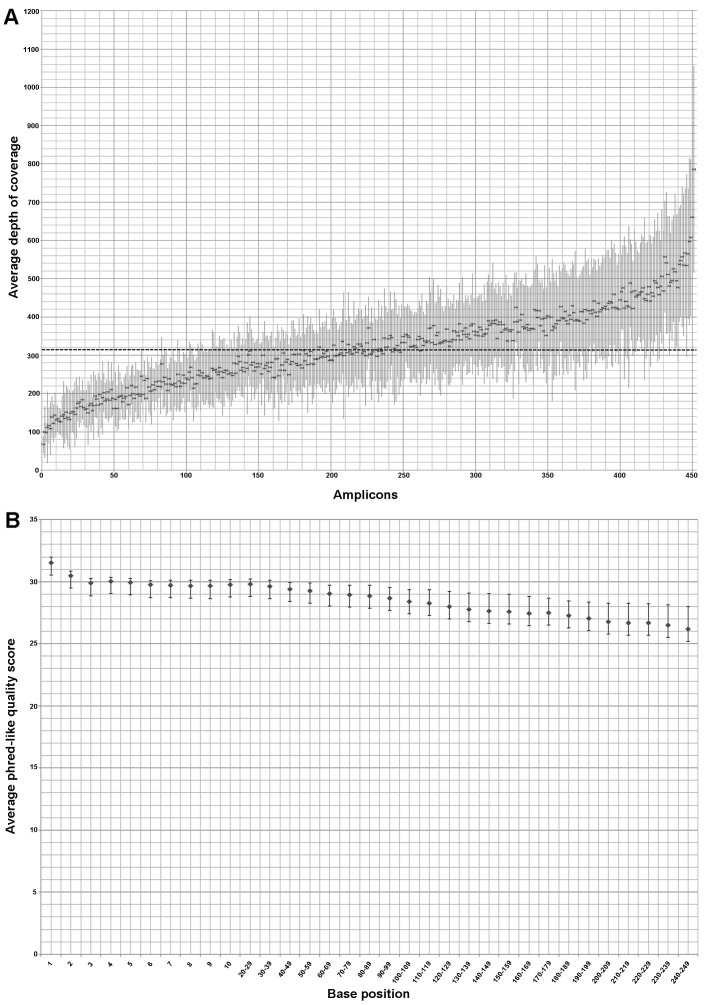

The mean depth of coverage per amplicon in the 73 samples of the training set was 318X and only 21 (4.6%) out of 452 amplicons showed a mean depth <150 reads (Fig. 1A). Six out of the 73 samples had an average read depth <150X and, among these, only 2 samples had an average read depth <100X.

Figure 1.

Depth of coverage and phred-like quality score of 73 samples belonging to training set; the dots and the bars represent the mean values and standard deviation, respectively. (A) Distribution of the average depth of coverage of all 452 amplicons (ordered according to the mean coverage, from the least to the most represented in the mean depth of coverage per-amplicon); the dashed line indicates the mean coverage (318X) concerning the 452 enriched amplicons of all patients. (B) Distribution of the average phred-like quality score related to each base of every amplicon that composes the alignment: the values are included between 26,2 and 31,5.

The average phred-like quality score respect at each base position of the training set ranged between 26.2 and 31.5, with the minimum and maximum value of the standard deviation equal to 0.41 and 1.79, respectively (Fig. 1B).

The training set: 'PGM™ Runs' evaluation in covered regions shows expected and additional mutations

The IACP sequencing of the training set confirmed the presence of 72 out of 73 expected mutations (detection rate of approximately 99%) with the known allelic status (Table II). In one sample we missed the deletion of the nucleotide at the position 2610 into MYBPC3 that is located within a homopolymer of 6 cytosines; in addition, in all samples, we observed the false-positive call MYH7:c.136T>C.

Table II.

Pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants identified by Ion AmpliSeq™ Custom Panel (IACP) sequencing into the training set following Runs evaluation for expected and additional mutations of 73 HCM patients.

| Gene | Nucleotide change | Effect on protein | Annotationb (HGMD or NCBI) | Predicted impact on protein | Variant frequency | Coverage | Q score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACTC1 | c.707C>T | p.(Ser236Phe) | KU324679 (present study) | Pathogenicd | 0.48 | 348 | 31.81 |

| ACTC1 | c.992T>A | p.(Ile331Asn) | KU324680 (present study) | Pathogenicd | 0.48 | 41 | 29.5 |

| GLA | c.514T>C | p.(Cys172Arg) | CM003746 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.5 | 1116 | 31.87 |

| GLA | c.1146C>A | p.(Cys382*) | KU508439 (present study) | Pathogenicc | 0.32 | 671 | 25.31 |

| LAMP2 | c.239G>T | p.(Gly80Val) | KU508440 (present study) | Likely pathogenicd | 0.49 | 271 | 28.6 |

| LAMP2 | c.741+1G>T | Mis-splicing | KU557502 (present study) | Pathogenicc | 0.5 | 177 | 29.23 |

| MYBPC3 | c.223G>A | p.(Asp75Asn) | HM090070 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.46 | 173 | 30.15 |

| MYBPC3 | c.506-2A>C | Mis-splicing | CS109051 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.43 | 191 | 28.22 |

| MYBPC3 | c.557C>T | p.(Pro186Leu) | CM106110 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.42 | 45 | 29.47 |

| MYBPC3 | c.649A>G | p.(Ser217Gly) | CM109108 [DM?] | Pathogenicd | 0.48 | 295 | 26.67 |

| MYBPC3 | c.772G>A | p.(Glu258Lys) | CM981322 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.5 | 526 | 30.12 |

| MYBPC3 | c.913_914delTT | p.(Phe305ProfsX27) | CD086092 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.45 | 410 | 27.48 |

| MYBPC3 | c.977G>A | p.(Arg326Gln) | CM020155 [DM?] | Likely pathogenicd | 0.45 | 451 | 27.1 |

| MYBPC3 | c.1003C>T | p.(Arg335Cys) | KU508441 (present study) | Pathogenicd | 0.5 | 288 | 31.23 |

| MYBPC3 | c.1090G>A | p.(Ala364Thr) | CM152770 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.53 | 232 | 27.45 |

| MYBPC3 | c.1112C>G | p.(Pro371Arg) | CM102043 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.47 | 355 | 28.62 |

| MYBPC3 | c.1174delG | p.(Ala392Leufs*14) | CD086093 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.51 | 183 | 26.15 |

| MYBPC3 | c.1458-1G>A | Mis-splicing | rs397515903 (dbSNP) | Pathogenicc | 0.61 | 241 | 29.65 |

| MYBPC3 | c.1505G>A | p.(Arg502Gln) | CM981325 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.43 | 521 | 30 |

| MYBPC3 | c.1564G>A | p.(Ala522Thr) | CM057197 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.55 | 182 | 29.82 |

| MYBPC3 | c.1591G>C | p.(Gly531Arg) | CM068013 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.57 | 142 | 26.98 |

| MYBPC3 | c.1615A>G | p.(Ile539Val) | CM1412245 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.51 | 215 | 29.22 |

| MYBPC3 | c.1624G>C | p.(Glu542Gln) | CM971007 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.5 | 176 | 32.78 |

| MYBPC3 | c.1670dup | p.(Ala558Argfs*10) | KU508442 (present study) | Pathogenicc | 0.54 | 396 | 29.51 |

| MYBPC3 | c.1696T>A | p.(Cys566Ser) | KU508443 (present study) | Pathogenicd | 0.35 | 440 | 28.53 |

| MYBPC3 | c.1790G>A | p.(Arg597Gln) | CM122972 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.51 | 635 | 31.83 |

| MYBPC3 | c.2198G>A | p.(Arg733His) | CM092564 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.44 | 159 | 29.97 |

| MYBPC3 | c.2258dupT | p.(Lys754Glufs*79) | CI063699 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.56 | 167 | 29.6 |

| MYBPC3 | c.2309-2A>G | Mis-splicing | CS043648 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.48 | 126 | 29.91 |

| MYBPC3 | c.2311G>A | p.(Val771Met) | CM056362 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.52 | 246 | 31.59 |

| MYBPC3 | c.2429G>A | p.(Arg810His) | CM034546 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.26 | 528 | 31.23 |

| MYBPC3 | c.2449C>G | p.(Arg817Gly) | KU508444 (present study) | Pathogenicd | 0.42 | 105 | 22.86 |

| MYBPC3 | c.2610delCa | p.(Ser871Alafs*8) | CD0910615 [DM] | Pathogenicc | – | – | – |

| MYBPC3 | c.2618C>T | p.(Pro873Leu) | CM116747 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.75 | 106 | 24 |

| MYBPC3 | c.2864_2865delCT | p.(Pro955Argfs*95) | CD982813 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.5 | 599 | 28.31 |

| MYBPC3 | c.2906-2A>G | Mis-splicing | KU508445 (present study) | Pathogenicc | 0.46 | 233 | 22.6 |

| MYBPC3 | c.2992C>G | p.(Gln998Glu) | CM043548 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.48 | 120 | 28.12 |

| MYBPC3 | c.3065G>C | p.(Arg1022Pro) | CM058261 [DM?] | Pathogenicd | 0.42 | 223 | 27.13 |

| MYBPC3 | c.3103G>A | p.(Ala1035Thr) | rs552505566 (present study) | Likely pathogenicd | 0.39 | 46 | 31 |

| MYBPC3 | c.3192dupC | p.(Lys1065Glnfs*12) | CI068119 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.51 | 95 | 28.26 |

| MYBPC3 | c.3331-1G>A | Mis-splicing | KU508446 (present study) | Pathogenicc | 0.45 | 78 | 30.25 |

| MYBPC3 | c.3364A>T | p.(Thr1122Ser) | KU508447 (present study) | Pathogenicd | 0.6 | 102 | 30.52 |

| MYBPC3 | c.3370T>C | p.(Cys1124Arg) | CM119645 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.55 | 137 | 28.65 |

| MYBPC3 | c.3551C>A | p.(Thr1184Asn) | CM086857 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.51 | 184 | 29.78 |

| MYBPC3 | c.3560T>G | p.(Leu1187Arg) | CM086863 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.48 | 198 | 29.1 |

| MYBPC3 | c.3697C>T | p.(Gln1233*) | CM014069 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.48 | 422 | 30.3 |

| MYBPC3 | c.3775C>T | p.(Gln1259*) | KU508448 (present study) | Pathogenicc | 0.5 | 263 | 23.1 |

| MYH7 | c.676G>A | p.(Ala226Thr) | KU319883 (present study) | Likely pathogenicd | 0.54 | 120 | 26.77 |

| MYH7 | c.1208G>A | p.(Arg403Gln) | CM900168 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.5 | 418 | 31.68 |

| MYH7 | c.1549C>A | p.(Leu517Met) | CM034554 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.49 | 201 | 26.95 |

| MYH7 | c.1988G>A | p.(Arg663His) | CM993620 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.49 | 247 | 28.56 |

| MYH7 | c.2102G>A | p.(Gly701Asp) | KU508453 (present study) | Pathogenicd | 0.51 | 431 | 32.93 |

| MYH7 | c.2804A>T | p.(Glu935Val) | KU508449 (present study) | Pathogenicd | 0.62 | 174 | 32.51 |

| MYH7 | c.2890G>C | p.(Val964Leu) | CM087588 [DM?] | Pathogenicd | 0.42 | 179 | 27.32 |

| MYH7 | c.3113T>C | p.(Leu1038Pro) | CM095777 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.5 | 194 | 28.45 |

| MYH7 | c.3133C>T | p.(Arg1045Cys) | CM086874 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.48 | 159 | 27.57 |

| MYH7 | c.3236G>A | p.(Arg1079Gln) | CM102044 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.51 | 129 | 31.65 |

| MYH7 | c.4040A>G | p.(Tyr1347Cys) | KU508450 (present study) | Pathogenicd | 0.5 | 202 | 29.54 |

| MYH7 | c.4348G>A | p.(Asp1450Asn) | CM122821 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.41 | 51 | 27.85 |

| MYH7 | c.4472C>G | p.(Ser1491Cys) | CM050712 [DM?] | Likely pathogenicd | 0.52 | 522 | 28.63 |

| MYH7 | c.4690G>A | p.(Glu1564Lys) | KU508451 (present study) | Likely pathogenicd | 0.25 | 522 | 28.46 |

| MYH7 | c.5287G>A | p.(Ala1763Thr) | CM1411014 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.49 | 348 | 30.56 |

| PRKAG2 | c.905G>A | p.(Arg302Gln) | CM011949 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.51 | 438 | 22.13 |

| TNNI3 | c.220C>G | p.(Arg74Gly) | KU508452 (present study) | Pathogenicd | 0.22 | 362 | 26.83 |

| TNNI3 | c.439G>C | p.(Val147Leu) | CM1411021 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.99 | 538 | 26.04 |

| TNNI3 | c.485G>A | p.(Arg162Gln) | CM034575 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.57 | 234 | 28.55 |

| TNNI3 | c.581A>G | p.(Asn194Ser) | CM1414551 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.56 | 178 | 27.41 |

| TNNT2 | c.83C>T | p.(Ala28Val) | CM063210 [DM] | pathogenicc | 0.52 | 174 | 26.89 |

| TNNT2 | c.247G>A | p.(Glu83Lys) | CM034581 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.46 | 307 | 32.69 |

| TNNT2 | c.275G>A | p.(Arg92Gln) | CM951218 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.46 | 897 | 25.98 |

| TNNT2 | c.536C>T | p.(Ser179Phe) | CM002871 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.5 | 699 | 26.38 |

| TNNT2 | c.832C>T | p.(Arg278Cys) | CM951222 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.6 | 126 | 29.11 |

| TPM1 | c.644C>T | p.(Ser215Leu) | CM087722 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.46 | 669 | 26.13 |

| MYOM1 | c.139A>G | p.(Ser47Gly) | rs202145133 (dbSNP) | Likely pathogenicd | 0.37 | 50 | 25.25 |

| MYOM1 | c.1514A>C | p.(Glu505Ala) | KU508437 (present study) | Likely pathogenicd | 0.58 | 68 | 27.97 |

| MYOM1 | c.2087G>A | p.(Arg696His) | KU508438 (present study) | Pathogenicd | 0.51 | 662 | 31.44 |

| MYOM1 | c.2110G>A | p.(Glu704Lys) | rs149528866 (dbSNP) | Likely pathogenicd | 0.47 | 258 | 27.57 |

| MYH6 | c.3883G>C | p.(Glu1295Gln) | rs34935550 (dbSNP) | Pathogenicd | 0.46 | 74 | 28.3 |

| MYH6 | 5476_5477delGGinsAA | p.(Gly1826Asn) | CX103031 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.3 | 361 | 23.38 |

| MYH6 | c.5797-2A>G | Mis-splicing | KU508454 (present study) | Pathogenicc | 0.49 | 424 | 19.97 |

| MYOZ2 | c.36A>C | p.(Lys12Asn) | KU508455 (present study) | Pathogenicd | 0.5 | 350 | 30.44 |

| LAMP2 | c.928G>A | p.(Val310Ile) | CM057189 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.49 | 103 | 31.68 |

| CAV3 | c.216C>G | p.(Cys72Trp) | CM980306 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.31 | 393 | 27.2 |

| CAV3 | c.233C>T | p.(Thr78Met) | CM065052 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.49 | 712 | 31.89 |

| ANKRD1 | c.827C>T | p.(Ala276Val) | CM095438 [DM?] | Likely pathogenicd | 0.51 | 330 | 30 |

| MYL2 | c.206T>C | p.(Met69Thr) | KU319885 (present study) | Pathogenicd | 0.46 | 315 | 31.78 |

| MYL2 | c.401A>C | p.(Glu134Ala) | CM086879 [DM] | Pathogenicc | 0.51 | 438 | 22.13 |

| GLA | c.937G>T | p.(Asp313Tyr) | CM930335 [DM?] | Likely pathogenicd | 1 | 517 | 25.61 |

Undetected mutation after NGS analysis.

Reference nucleotide data: starting with CM/CX/CI/CD/CS/HM for variants annotated in HGMD; starting with KU/rs for variants annotated in NCBI (GenBank, accession no./dbSNP).

Mutations annotated in Human Genome Mutation Database (HGMD, http://www.hgmd.org/; release 2015.4) as DM (disease-causing mutations) and nonsense, frameshift, canonical splice site (±2 bp) mutations identified in this study (or annotated only in dbSNP) were classified as 'pathogenic'.

The missense mutations not annotated in HGMD and those described as 'DM of questionable pathological relevance' (DM?) were classified as i) 'pathogenic variants' if the pathogenic impact was predicted by all algorithms; ii) 'likely pathogenic variants' if the pathogenic impact was predicted by two out of three algorithms. Bold font indicates the additional mutations identified only by NGS analysis. NGS, next generation sequencing; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

Furthermore, following 'PGM Runs' evaluation of the genes not previously investigated by Sanger sequencing, we identified 15 additional mutations (Table II) of which 10 were in genes encoding proteins different from (TTms) (4 were in genes encoding a protein located in the M-band, 2 were in encoding Z-disk constituents genes, 2 were in metabolic genes and 2 were in the CAV3 gene). Taking into account the stringent criteria established in the 'Patients and methods' section, 10 out of 15 additional mutations could be ascribed to the category 'pathogenic variants', while the remaining 5 were classified as 'likely pathogenic variants' (Table II).

The training set: the additional mutations are identified in HCM subjects with arrhythmias or with pre-excitation syndrome

The 15 additional mutations belong to 11 out of 73 patients (15%) (Table III). In 2 patients, we identified only mutations of genes encoding TTm proteins, while in the remaining 9 patients, we characterized co-occurring mutations of genes encoding TTm/non-TTm proteins. Three out of 9 subjects with mutations of genes encoding TTm and non-TTm proteins had a personal history characterized by atrial fibrillation and non-sustained ventricular tachycardia episodes. Additionally, the NGS re-analysis permitted the identification of: i) two mutations in the MYL2 gene in one teenager affected by hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy that initially, following Sanger analysis, was classified as wild-type; ii) the missense mutation LAMP2:p.(Val310Ile), already described as causative of Danon disease, in a young female affected by HCM and with the typical Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) electrocardiographic pattern (shortened PR interval and delta wave).

Table III.

HCM patients belonging at training set that, after NGS analysis, show pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants in genes originally not analyzed using Sanger sequencing.

| No. of patient (gender) | Age at onset (years) | LVWT (mm) | AICD (yes, no) | Family history of HCM/SCD (yes, no/yes, no) | Other medical (recurrent or episodic) issues | LVEF (%) | Mutations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #94 (F) | 30 | 24 | No | No/no | None | 65 |

MYBPC3: c.1174delG p.(Ala392fsX405) MYH7: c.161G>T p.(Arg54Leu)a TNNT2: c.832C>T p.(Arg278Cys) MYOM1: c.2087G>A p.(Arg696His) |

| #241 (F) | 17 | <15b | No | No/no | H-tx | 44 |

TNNT2: c.83C>T p.(Ala28Val) LAMP2: c.741+1G>T MYOM1: c.1514A>C p.(Glu505Ala) |

| #314 (M) | 48 | 21 | No | Yes/no | History of hypertension | 62 |

MYBPC3: c.1458-1G>A MYOM1: c.139A>G p.(Ser47Gly) MYOM1: c.2110G>A p.(Glu704Lys) MYH6: c.3883G>C p.(Glu1295Gln) |

| #656 (M) | 56 | 15 | No | No/no | AF, NSVT | 65 |

MYBPC3: c.2610del p.(Ser871AlafsX8) GLA: c.937G>T p.(Asp313Tyr) |

| #692 (F) | 65 | 22 | No | Yes/no | History of hypertension | 65 |

MYBPC3: c.1624G>C p.(Glu542Gln) MYOZ2: c.36A>C p.(Lys12Asn) |

| #748 (F) | 16 | 17 | Yes | Yes/yes | NSVT, AF, WPW syndrome | 60 |

MYH7: c.5287G>A p.(Ala1763Thr) LAMP2: c.928G>A p.(Val310Ile) |

| #787 (M) | 45 | 32 | Yes | Yes/no | Dyslipidemia, nodular thyroid disease, NSVT, AF, AFL | 60 |

MYBPC3: c.2429G>A p.(Arg810His) MYBPC3: c.3370T>C p.(Cys1124Arg) CAV3: c.216C>G p.(Cys72Trp) |

| #800 (F) | 25 | 16 | No | Yes/yes | None | 50 |

TNNT2: c.536C>T p.(Ser179Phe) MYH6: c.5797-2A>G MYH6: c.5476_5477delinsAA p.(Gly1826Asn) |

| #834 (F) | 14 | 24 | Yes | Yes/yes | LGE at CMR imaging | 68 |

TNNT2: c.275G>A p.(Arg92Gln) CAV3: c.233C>T p.(Thr78Met) |

| #854 (M) | 46 | 19 | No | Yes/no | None | 60 |

MYBPC3: c.506-2A>C ANKRD1: c.827C>T p.(Ala276Val) |

| #865 (M) | 14 | 28 | Yes | Yes/no | HOCM, myocardial bridge on AIA, v-fib | 60 |

MYL2: c.401A>C p.(Glu134Ala) MYL2: c.206T>C p.(Met69Thr) |

Bold font indicates additional mutations in MYH6, MYL2 or in genes encoding non-TTm proteins identified only by NGS analysis.

Uncovered regions: mutation identified only by Sanger sequencing;

Original borderline diagnosis of HCM has been modified in dilated cardiomyopathy. WPW, Wolff-Parkinson-White; AICD, automatic implantable cardioverter defibrillator; H-tx, heart transplantation; LVWT, left ventricular wall thickness; AF, atrial fibrillation; NSVT, non-sustained ventricular tachycardia; AFL, atrial flutter; LGE, late gadolinium enhancement; AIA, anterior interventricular artery; CMR, cardiac magnetic risonance; v-fib, ventricular fibrillation; HOCM, hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; SCD, sudden cardiac death; NGS, next generation sequencing; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

The discovery set: PGM ™ Runs evaluation for 19 HCM-related genes in 19 patients

The IACP sequencing of 19 DNA samples, and the following PGM Runs evaluation for all genes of the panel, allowed the identification of 20 mutations in 7 genes (Table IV).

Table IV.

Pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants identified by Ion AmpliSeq™ Custom Panel (IACP) sequencing into the discovery set consisting of 19 HCM DNA samples.

| Gene | Nucleotide change | Effect on protein | Annotation (HGMD or NCBI) | Predicted impact on protein | Variant frequency | Coverage | Q score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13 mutations in two major sarcomeric genes | MYBPC3 | c.506-2A>C | Mis-splicing | CS152769 [DM] | Pathogenica | 0.45 | 273 | 30.76 |

| MYBPC3 | c.639C>A | p.(Tyr213*) | KU319882 (present study) | Pathogenica | 0.52 | 385 | 32.15 | |

| MYBPC3 | c.649A>G | p.(Ser217Gly) | CM109108 [DM] | Pathogenica | 0.52 | 428 | 31.85 | |

| MYBPC3 | c.1409G>A | p.(Arg470Gln) | CM116865 [DM] | Pathogenica | 0.42 | 469 | 28.16 | |

| MYBPC3 | c.1505G>A | p.(Arg502Gln) | CM981325 [DM] | Pathogenica | 0.47 | 191 | 28.72 | |

| MYBPC3 | c.1564G>A | p.(Ala522Thr) | CM057197 [DM] | Pathogenica | 0.49 | 122 | 29.78 | |

| MYBPC3 | c.2309-2A>G | Mis-splicing | CS043648 [DM] | Pathogenica | 0.5 | 176 | 29.58 | |

| MYBPC3 | c.2311G>A | p.(Val771Met) | CM056362 [DM] | Pathogenica | 0.56 | 128 | 31.5 | |

| MYBPC3 | c.2429G>A | p.(Arg810His) | CM034546 [DM] | Pathogenica | 0.24 | 412 | 33.22 | |

| MYBPC3 | c.3617G>A | p.(Gly1206Asp) | CM057198 [DM] | Pathogenica | 0.5 | 649 | 30.63 | |

| MYH7 | c.2302G>C | p.(Gly768Arg) | CM109192 [DM] | Pathogenica | 0.42 | 271 | 29.17 | |

| MYH7 | c.2507T>C | p.(Ile836Thr) | KU319884 (present study) | Pathogenicb | 0.5 | 303 | 31.87 | |

| MYH7 | c.5302G>A | p.(Glu1768Lys) | CM042429 [DM] | Pathogenica | 0.57 | 326 | 32.63 | |

| 7 mutations in other genes | MYH6 | c.3883G>C | p.(Glu1295Gln) | rs34935550 (dbSNP) | Pathogenicb | 0.41 | 86 | 27.89 |

| MYH6 | c.5111C>T | p.(Ala1704Val) | KU508434 (present study) | Likely pathogenicb | 0.47 | 553 | 32.91 | |

| MYOM1 | c.432-1G>T | Mis-splicing | KU508435 (present study) | Pathogenica | 0.51 | 773 | 30.67 | |

| MYOM1 | c.1655G>A | p.(Gly552Asp) | KU508436 (present study) | Likely pathogenicb | 0.44 | 265 | 32.35 | |

| GLA | c.718_719delAA | p.(Lys240Glufs*9) | CD941686 [DM] | Pathogenica | 1 | 270 | 32.53 | |

| LAMP2 | c.661G>A | p.(Gly221Arg) | CM137777 [DM?] | pathogenicb | 0.55 | 115 | 30.42 | |

| MYOZ2 | c.488T>C | p.(Leu163Ser) | rs143345726 (dbSNP) | Likely pathogenicb | 0.45 | 319 | 32.86 |

Reference nucleotide data: starting with CM/CD/CS for variants annotated in HGMD; starting with KU/rs for variants annotated in NCBI (GenBank, accession number/dbSNP).

Mutations annotated in Human Genome Mutation Database (HGMD, http://www.hgmd.org/; release 2015.4) as DM (disease-causing mutations) and nonsense, frameshift or canonical splice site (±2 bp) mutations identified in this study (or annotated only in dbSNP) were classified as 'pathogenic'.

The missense mutations not annotated in HGMD and those described as 'DM of questionable pathological relevance' (DM?) were classified as i) 'pathogenic variants' if the pathogenic impact was predicted by all algorithms; ii) 'likely pathogenic variants' if the pathogenic impact was predicted by two out of three algorithms. HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

Thirteen mutations were identified in 2 major sarcomeric genes, MYBPC3 and MYH7; all 13 mutations were classified as 'pathogenic variants'.

The remaining 7 mutations were identified in the following genes: i) MYH6 (2 mutations in thick filament); ii) MYOM1 (2 mutations in M-band protein); iii) MYOZ2 (one mutation in Z-disk constituent); iv) GLA and LAMP2 (one mutation each in metabolic genes). Four mutations were classified as 'pathogenic variants' and the remaining 3 were considered as 'likely pathogenic variants'. No false-positive result was identified in our discovery set.

The discovery set: mutations in genes encoding non-TTm proteins are identified in borderline HCM status and in an HCM subject with an extremely complex phenotype

The 20 mutations were identified in 15 out of 19 patients (Table V). A single mutant allele in genes encoding non-TTm proteins was identified in 3 patients without a family history of HCM; by contrast, the 5 patients that had a family history of HCM carried a single mutant allele in genes encoding TTm proteins. Two out of 3 patients with only a single mutant allele in genes (LAMP2 for female patient, MYOM1) encoding non-TTm proteins had a diagnosis of borderline HCM, while the male patient with co-occuring mutations in genes encoding TTm proteins (MYBPC3 and MYH6) and in the GLA gene showed the diagnostic parameter of HCM (LVWT, 19 mm) together with a history of atrial fibrillation and multiorgan involvement (skin, eyes, ears and thyroid), typical of Fabry disease of male patients.

Table V.

HCM patients belonging at discovery set that, after NGS analysis, show pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants.

| No. of patient (gender) | Age at onset (years) | LVWT (mm) | AICD (yes, no) | Family history of HCM/SCD (yes, no/yes, no) | Other medical (recurrent or episodic) issues | LVEF (%) | Mutations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #890 (F) | 72 | <15a | No | No/no | Aortic root enlargement History of hypertension; Intermittent LBBB | ~50 | LAMP2: c.661G>A p.(Gly221Arg) |

| #892 (F) | 30 | 19 | No | No/no | LGE at CMR imaging; hypercholesterolemia; NSVT | 61 |

MYBPC3: c.1505G>A p.(Arg502Gln) MYBPC3: c.1564G>A p.(Ala522Thr) MYBPC3: c.2311G>A p.(Val771Met) |

| #894 (M) | 6 | 24 | No | No/no | T2DM | 60 | MYBPC3: c.2429G>A p.(Arg810His) |

| #895 (M) | 58 | <15b | Yes | Yes/no | None | 26 | MYBPC3: c.2309-2A>G |

| #898 (F) | 1 | 11 | No | Yes/no | None | 70 | MYH7: c.5302G>A p.(Glu1768Lys) |

| #902 (F) | 25 | 19 | Yes | No/no | Hypothyroidism PVC, NSVT | 64 | MYH7: c.2507T>C p.(Ile836Thr) |

| #903 (F) | 52 | 18 | Yes | No/no | Myasthenia gravis, T2DM, HepC, PVC, PACs, PSVT, SND | 59 | MYOZ2: c.488T>C p.(Leu163Ser) |

| #905 (M) | 30 | NA | Yes | Yes/no | H-tx | NA |

MYH7: c.2302G>C p.(Gly768Arg) MYOM1: c.1655G>A p.(Gly552Asp) |

| #906 (F) | 58 | 15 | No | No/no | None | NA | MYBPC3: c.3617G>A p.(Gly1206Asp) |

| #907 (M) | 37 | <15a | No | No/no | ECG abnormalities | 60 | MYOM1: c.432-1G>T |

| #908 (M) | 20 | <15b | No | Yes/no | H-tx, T2DM | 50 | MYH6: c.5111C>T p.(Ala1704Val) |

| #909 (M) | 31 | <15a | No | Yes/no | None | 75 | MYBPC3: c.1409G>A p.(Arg470Gln) |

| #910 (F) | 17 | 23 | No | No/no | None | 76 | MYBPC3: c.639C>A p.(Tyr213*) |

| #913 (M) | 12 | 19 | No | No/no | Angiokeratomas right ear hearing loss Visual impairment hypothyroidism, AF, NSVT |

60 |

MYBPC3: c.649A>G p.(Ser217Gly) GLA: c.718_719delAA p.(Lys240Glufs*9) MYH6: c.3883G>C p.(Glu1295Gln) |

| 914 (M) | 22 | 34 | Yes | No/no | HOCM, LGE at CMR imaging, NSVT | 65 | MYBPC3: c.506-2A>C |

Bold font indicates mutations in MYH6 and in genes encoding non-TTm proteins that would not been identified without NGS analysis.

Diagnosis of borderline HCM;

original diagnosis of borderline HCM has been modified in dilated cardiomyopathy. PAC, premature atrial contractions; H-tx, heart transplantation; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; LVWT, left ventricular wall thickness; SND, sinus node dysfunction; AF, atrial fibrillation; hep C, hepatitis C; LBBB, left bundle branch block; AICD, automatic implantable cardioverter defibrillator; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; SCD, sudden cardiac death; LGE, late gadolinium enhancement; CMR, cardiac magnetic risonance; NSVT, non-sustained ventricular tachycardia; PVC, premature ventricular contractions; HOCM, hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy; PSVT, paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia; NA, not available; NGS, next generation sequencing; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

Discussion

Hereditary HCM is historically known as an autosomal dominant disease and is associated mainly with mutations in the MYBPC3 and MYH7 genes. Over the past years, it has become increasingly evident that the same pathogenic mutation, even within the same family, shows a highly variable presentation and clinical course in different individuals (18,19). Contextually, it has been shown that hereditary HCM can also be associated with mutations of genes that do not encode TTm proteins (7–12) and, in some patients, more than one pathogenic mutation has been identified (22). In consideration of this complexity, as well as the possibility of shedding new light on the relationship between the genetic and the phenotypic heterogeneity, in this study, we designed a target NGS panel, using the Ion Torrent PGM system, in order to simultaneously analyze a total of 19 genes encoding not only TTm proteins, but also other sarcomeric proteins and some non-sarcomeric proteins that cause HCM phenocopies (1,3,13).

Our training set allowed us to calibrate the NGS methodology (enrichment, library preparation and bioinformatics analysis parameters). With respect to all 284 coding exons, the coverage at >20X depth for each target nucleotide (see Patients and methods) includes 253 out of 259 exons correctly profiled by IAD. This not uniform coverage of our design, as previously reported, could be linked to aspects concerning the target gene enrichment strategy and at the efficiencies of PCR amplification during library preparation (30). It has been reported that regions with high a GC content are more difficult to amplify and, also, the PGM system has showed a poor coverage within AT-rich exonic segments of P. falciparum (31). Additionally, in our NGS gene panel, specific genomic regions, such as those with a high homology of the MYH6 and MYH7 genes, contribute greatly to this inadequate coverage.

With respect to the target NGS study by Gómez et al (32), our diagnostic HCM workflow provides the analysis of a larger number of genes, including some which encode for proteins different from myofilaments of the sarcomere and 3 genes responsible for the HCM phenocopy. Moreover, through a combined strategy with Sanger sequencing, we ensured a depth of coverage >20X for each target nucleotide; other studies (15,33) have reported a higher coverage depth, but only as a general mean coverage.

According to the training set analysis, we observed only one false-negative: our non-identified mutation is located into a short homopolymer region that, as has already been reported (31), represents a DNA motif particularly prone to this error, as in these regions, there is not a linear correlation of pH between signal-generated and the number of nucleotides incorporated; the only false-positive call MYH7:c.136T>C was already reported in another study (32) and it is located in the first coding exon that had inappropriate coverage and hence, was necessarily analyzed by Sanger sequencing.

Our target NGS panel, applied to the training set encompassing 73 patients, allowed the identification of 15 additional mutations in 11 patients (Table III); these mutations were characterized in genes originally not analyzed by Sanger sequencing: 10 belong to genes encoding proteins of the sarcomere different from (TTms) and, of these, 4 are mutant alleles of the MYOM1 gene that have previously been associated with HCM in a single study (7). One out of 10 patients, that originally showed wild-type status after Sanger analysis, carried 2 pathogenic alleles in the MYL2 gene that could support the molecular diagnosis of hereditary HCM, whereas for the remaining 10 out of 63 patients, the newly identified mutation (that represents the co-occuring mutation together with other already described as causative of HCM) could contribute as a modifier of the clinical picture in the affected patients of each HCM family (3,16,22,33); for example, the WPW electrocardiographic pattern of patient #748 (female), that carries a mutant allele in the genes LAMP2 (X-linked) and MYH7, has already been documented by Cheng et al (34) in some patients with Danon disease and mutation in the LAMP2 gene.

Our target NGS panel, applied to the discovery set, allowed the identification of 20 mutations in 15 patients (Table V). If the molecular characterization of these patients was performed with the older diagnostic workflow, a mutant allele would have been identified only in 11 patients, as the analysis of LAMP2 and GLA genes would have had to be specifically requested and the Sanger assay did not include the screening of the MYOM1, MYOZ2 and MYH6 genes.

The evaluation of the discovery set, even though it is represented by only 15 patients with mutations, seems to suggest that the presence of only one mutant allele in genes encoding non-TTm proteins (LAMP2, MYOM1 and MYOZ2) is associated with a milder HCM status: 2 out of 3 patients had a diagnosis of borderline HCM and none of these 3 patients had a family history of HCM or SCD; at the same time, mutations in genes encoding TTm proteins have been identified in all patients that had a family history of HCM and in only one patient with a diagnosis of borderline HCM. Consistent with the findings of larger studies on genotype-phenotype correlations (35,36), although this study did not have this objective, we found that patients without myofilament mutations, encompassing a female subject with single mutant allele in the LAMP2 (X-linked) gene, show a less severe phenotype.

Interestingly, among the 26 patients of which we report the clinical data, 4 out of 10 HCM subjects with concomitant mutations in genes encoding TTm and non-TTm proteins have also had a history of atrial fibrillation; although, this small sample can only suggest a trend, when the arrhythmia was compared between this subset of patients and the remaining 16 subjects carrying mutations in genes encoding TTm (13 patients) or non-TTm proteins (3 patients) only, the distribution was significantly different (Fisher's exact test, p<0.05).

Our data suggest that the screening of new genes using the NGS methodology increases the number of identified mutations. In particular, the discovery set has allowed us to increase the diagnostic yield from 58 to 79%. Additionally, with respect to the Sanger sequencing, the genotyping of the discovery set with NGS methodology has allowed a reduction in turnaround-time for HCM of approximately 75%.

Therefore, in our new diagnostic workflow, including the screening of genes encoding non-TTm proteins, despite the drawback represented by the need to combine targeted NGS and Sanger sequencing in order to obtain a depth of coverage >20X for each target nucleotide, the use of the Ion PGM system has showed the following advantages: i) an important decrease in the turn-around-time; ii) an increase in the diagnostic yield; iii) the detection of multiple mutations, or single mutant alleles in genes encoding non-TTm proteins, that contribute to better defining the genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity of HCM: mutations in genes encoding only non-TTm proteins seem to show a milder HCM status, whereas co-occuring mutations of genes encoding TTm and non-TTm proteins could explain the wide variability of the HCM phenotype.

Given the complexity of target NGS methodology, and as previously suggested by the guidelines of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (37), when the genetic test is requested for clinical diagnostic purposes, this technique should be performed by highly specialized laboratories, i.e., laboratories with ISO9001 certification and possibly with the professional accreditation (in Italy SIGU-CERT, Italian Society of Human Genetics certification program).

The target NGS methodology, by permitting a more rapid analysis of a large number of causative genes, may prove to be useful in unveiling the significant genetic heterogeneity of this complex disease that, conjugated with the broad phenotypic heterogeneity, may improve genetic counselling and the clinical management of patients.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the patients for their participation in this study. We would like to thank Dr Elena Gennaro, Dr Angela Robbiano and Dr Federico Zara for their contributing to the evaluation of the parameters concerning the NGS data analysis that were applied to the training set. We would also like to thank the Galliera Genetic Bank (Dr Chiara Baldo) [Network of Telethon Genetic Biobanks (supported by the Italian Telethon project no. GTB12001)] for providing us with parts of the specimens.

Appendix

Members of the Collaborative Working Group that contributed to the study as co-authors: Paolo Di Donna (Cardiology Division, Cardinal G. Massaia Hospital, Asti, Italy); Alessandra Franzoni (Dipartimento di Medicina di Laboratorio, Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria S. Maria della Misericordia, Udine, Italy); Teresa Mattina (Department of Pediatrics, Medical Genetics University of Catania, Catania, Italy); Sebastiano Bianca and Chiara Barone (Centro di Consulenza Genetica e Teratologia della Riproduzione, Dipartimento Materno Infantile, ARNAS Garibaldi Nesima, Catania, Italy); Dora Fabbro (Department of Medical and Biological Sciences, University of Udine, Udine, Italy); Stefano Caselli (Institute of Sports Medicine and Science, Rome, Italy); Cesare Renzelli (U.O. Pediatria, Presidio Ospedaliero di Ravenna, Italy); Enrico Grosso (Medical Genetics Unit, 'Città della Salute e della Scienza' University Hospital, Torino, Italy); Patrizio Sarto (UOC of Sport Medicine, ULSS Company 9, Treviso, Italy); Concetta Simona Perrotta (Ambulatorio Genetica Medica, P.O. 'V. Emanuele', Gela, Italy); Carmelo Spadaro (UOC Cardiologia, P.O. 'V. Emanuele', Gela, Italy); Giuseppe Leonardi (UOS Scompenso Cardiaco, Azienda Ospedaliero, Universitaria 'Policlinico-V. Emanuele', Catania, Italy); Demetrio Baldo (Unit of Medical Genetics, ULSS 9 Treviso Hospital, Treviso, Italy); Yana Bettinetti (SSD Cardiologia dipartimento emergenza, Ospedale di Albenga, Italy); Alessandro Nicoletti (UO Pediatria, Ospedale di Bussolengo, Italy); Maria Teresa Ricci (SSD Genetica Medica, AOU San Luigi Gonzaga, Orbassano, Italy); Lucia Baruzzo (ASL2 Savonese, Ospedale San Paolo, Savona, Italy); Alessandro Rimini (Cardiology Unit, IRCCS 'Istituto Giannina Gaslini' Children's Hospital, Genova, Italy); Huei-sheng Vincent Chen (Sanford-Burnham-Prebys Medical Discovery Institute and University of California-San Diego, Departments of Medicine/Cardiology, La Jolla, CA, USA); Conte Maria Rosa (Department of Public Health and Pediatrics, University of Turin, Turin, Italy; Department of Cardiology, Mauriziano Hospital, Turin, Italy).

References

- 1.Maron BJ, Maron MS, Semsarian C. Genetics of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy after 20 years: Clinical perspectives. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:705–715. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.02.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maron BJ, Maron MS. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Lancet. 2013;381:242–255. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60397-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ho CY, Charron P, Richard P, Girolami F, Van Spaendonck-Zwarts KY, Pinto Y. Genetic advances in sarcomeric cardio-myopathies: State of the art. Cardiovasc Res. 2015;105:397–408. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvv025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watkins H, Anan R, Coviello DA, Spirito P, Seidman JG, Seidman CE. A de novo mutation in alpha-tropomyosin that causes hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1995;91:2302–2305. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.91.9.2302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casali C, d'Amati G, Bernucci P, DeBiase L, Autore C, Santorelli FM, Coviello D, Gallo P. Maternally inherited cardiomyopathy: Clinical and molecular characterization of a large kindred harboring the A4300G point mutation in mitochondrial deoxyribonucleic acid. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:1584–1589. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(99)00079-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hagen CM, Aidt FH, Havndrup O, Hedley PL, Jensen MK, Kanters JK, Pham TT, Bundgaard H, Christiansen M. Private mitochondrial DNA variants in danish patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0124540. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siegert R, Perrot A, Keller S, Behlke J, Michalewska-Włudarczyk A, Wycisk A, Tendera M, Morano I, Ozcelik C. A myomesin mutation associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy deteriorates dimerisation properties. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;405:473–479. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.01.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Osio A, Tan L, Chen SN, Lombardi R, Nagueh SF, Shete S, Roberts R, Willerson JT, Marian AJ. Myozenin 2 is a novel gene for human hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 2007;100:766–768. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000263008.66799.aa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arimura T, Bos JM, Sato A, Kubo T, Okamoto H, Nishi H, Harada H, Koga Y, Moulik M, Doi YL, et al. Cardiac ankyrin repeat protein gene (ANKRD1) mutations in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:334–342. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vasile VC, Ommen SR, Edwards WD, Ackerman MJ. A missense mutation in a ubiquitously expressed protein, vinculin, confers susceptibility to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;345:998–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.04.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiu C, Tebo M, Ingles J, Yeates L, Arthur JW, Lind JM, Semsarian C. Genetic screening of calcium regulation genes in familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;43:337–343. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayashi T, Arimura T, Ueda K, Shibata H, Hohda S, Takahashi M, Hori H, Koga Y, Oka N, Imaizumi T, et al. Identification and functional analysis of a caveolin-3 mutation associated with familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;313:178–184. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.11.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gersh BJ, Maron BJ, Bonow RO, Dearani JA, Fifer MA, Link MS, Naidu SS, Nishimura RA, Ommen SR, Rakowski H, et al. American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. American Association for Thoracic Surgery. American Society of Echocardiography. American Society of Nuclear Cardiology. Heart Failure Society of America. Heart Rhythm Society. Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. Society of Thoracic Surgeons 2011 ACCF/AHA guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2011;124:2761–2796. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318223e230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ingles J, Sarina T, Yeates L, Hunt L, Macciocca I, McCormack L, Winship I, McGaughran J, Atherton J, Semsarian C. Clinical predictors of genetic testing outcomes in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Genet Med. 2013;15:972–977. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meder B, Haas J, Keller A, Heid C, Just S, Borries A, Boisguerin V, Scharfenberger-Schmeer M, Stähler P, Beier M, et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing for the molecular genetic diagnostics of cardiomyopathies. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2011;4:110–122. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.110.958322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zou Y, Wang J, Liu X, Wang Y, Chen Y, Sun K, Gao S, Zhang C, Wang Z, Zhang Y, et al. Multiple gene mutations, not the type of mutation, are the modifier of left ventricle hypertrophy in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Mol Biol Rep. 2013;40:3969–3976. doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-2474-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Biagini E, Olivotto I, Iascone M, Parodi MI, Girolami F, Frisso G, Autore C, Limongelli G, Cecconi M, Maron BJ, et al. Significance of sarcomere gene mutations analysis in the end-stage phase of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2014;114:769–776. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.05.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roberts WC, Roberts CC, Ko JM, Grayburn PA, Tandon A, Kuiper JJ, Capehart JE, Hall SA. Dramatically different phenotypic expressions of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in male cousins undergoing cardiac transplantation with identical disease-causing gene mutation. Am J Cardiol. 2013;111:1818–1822. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Landstrom AP, Ackerman MJ. Mutation type is not clinically useful in predicting prognosis in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2010;122:2441–2450. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.954446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.von Bubnoff A. Next-generation sequencing: The race is on. Cell. 2008;132:721–723. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Churko JM, Mantalas GL, Snyder MP, Wu JC. Overview of high throughput sequencing technologies to elucidate molecular pathways in cardiovascular diseases. Circ Res. 2013;112:1613–1623. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.300939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lopes LR, Syrris P, Guttmann OP, O'Mahony C, Tang HC, Dalageorgou C, Jenkins S, Hubank M, Monserrat L, McKenna WJ, et al. Novel genotype-phenotype associations demonstrated by high-throughput sequencing in patients with hypertrophic cardio-myopathy. Heart. 2015;101:294–301. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-306387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morinière V, Dahan K, Hilbert P, Lison M, Lebbah S, Topa A, Bole-Feysot C, Pruvost S, Nitschke P, Plaisier E, et al. Improving mutation screening in familial hematuric nephropathies through next generation sequencing. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:2740–2751. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013080912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pasmant E, Parfait B, Luscan A, Goussard P, Briand-Suleau A, Laurendeau I, Fouveaut C, Leroy C, Montadert A, Wolkenstein P, et al. Neurofibromatosis type 1 molecular diagnosis: What can NGS do for you when you have a large gene with loss of function mutations? Eur J Hum Genet. 2015;23:596–601. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2014.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spirito P, Autore C, Rapezzi C, Bernabò P, Badagliacca R, Maron MS, Bongioanni S, Coccolo F, Estes NA, Barillà CS, et al. Syncope and risk of sudden death in hypertrophic cardio-myopathy. Circulation. 2009;119:1703–1710. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.798314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Authors/Task Force members. Elliott PM, Anastasakis A, Borger MA, Borggrefe M, Cecchi F, Charron P, Hagege AA, Lafont A, Limongelli G, Mahrholdt H, et al. 2014 ESC Guidelines on diagnosis and management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2733–2779. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rapezzi C, Arbustini E, Caforio AL, Charron P, Gimeno-Blanes J, Heliö T, Linhart A, Mogensen J, Pinto Y, Ristic A, et al. Diagnostic work-up in cardiomyopathies: Bridging the gap between clinical phenotypes and final diagnosis. A position statement from the ESC Working Group on Myocardial and Pericardial Diseases. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:1448–1458. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thorvaldsdóttir H, Robinson JT, Mesirov JP. Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV): High-performance genomics data visualization and exploration. Brief Bioinform. 2013;14:178–192. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbs017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stenson PD, Mort M, Ball EV, Shaw K, Phillips A, Cooper DN. The Human Gene Mutation Database: Building a comprehensive mutation repository for clinical and molecular genetics, diagnostic testing and personalized genomic medicine. Hum Genet. 2014;133:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s00439-013-1358-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Voelkerding KV, Dames S, Durtschi JD. Next generation sequencing for clinical diagnostics-principles and application to targeted resequencing for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: A paper from the 2009 William Beaumont Hospital Symposium on Molecular Pathology. J Mol Diagn. 2010;12:539–551. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2010.100043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quail MA, Smith M, Coupland P, Otto TD, Harris SR, Connor TR, Bertoni A, Swerdlow HP, Gu Y. A tale of three next generation sequencing platforms: Comparison of Ion Torrent, Pacific Biosciences and Illumina MiSeq sequencers. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:341. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gómez J, Reguero JR, Morís C, Martín M, Alvarez V, Alonso B, Iglesias S, Coto E. Mutation analysis of the main hypertrophic cardiomyopathy genes using multiplex amplification and semiconductor next-generation sequencing. Circ J. 2014;78:2963–2971. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-14-0628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lopes LR, Zekavati A, Syrris P, Hubank M, Giambartolomei C, Dalageorgou C, Jenkins S, McKenna W, Plagnol V, Elliott PM, Uk10k Consortium Genetic complexity in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy revealed by high-throughput sequencing. J Med Genet. 2013;50:228–239. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-101270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheng Z, Cui Q, Tian Z, Xie H, Chen L, Fang L, Zhu K, Fang Q. Danon disease as a cause of concentric left ventricular hypertrophy in patients who underwent endomyocardial biopsy. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:649–656. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bos JM, Will ML, Gersh BJ, Kruisselbrink TM, Ommen SR, Ackerman MJ. Characterization of a phenotype-based genetic test prediction score for unrelated patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89:727–737. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Olivotto I, Girolami F, Ackerman MJ, Nistri S, Bos JM, Zachara E, Ommen SR, Theis JL, Vaubel RA, Re F, et al. Myofilament protein gene mutation screening and outcome of patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:630–638. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)60890-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rehm HL, Bale SJ, Bayrak-Toydemir P, Berg JS, Brown KK, Deignan JL, Friez MJ, Funke BH, Hegde MR, Lyon E, Working Group of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics Laboratory Quality Assurance Commitee ACMG clinical laboratory standards for next-generation sequencing. Genet Med. 2013;15:733–747. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]