Abstract

Multi-protein complexes organized by cytoskeletal proteins are essential for cell wall biogenesis in most bacteria. Current models of the wall assembly mechanism assume class A penicillin-binding proteins (aPBPs), the targets of penicillin-like drugs, function as the primary cell wall polymerases within these machineries. Here, we use an in vivo cell wall polymerase assay in Escherichia coli combined with measurements of the localization dynamics of synthesis proteins to investigate this hypothesis. We find that aPBP activity is not necessary for glycan polymerization by the cell elongation machinery as is commonly believed. Instead, our results indicate that cell wall synthesis is mediated by two distinct polymerase systems, SEDS-family proteins working within the cytoskeletal machines and aPBP enzymes functioning outside of these complexes. These findings thus necessitate a fundamental change in our conception of the cell wall assembly process in bacteria.

Text

An essential cell wall surrounds most bacteria protecting their cytoplasmic membrane from osmotic rupture 1. This structure is built from the heteropolymer peptidoglycan (PG), which consists of glycan chains with attached peptides used to form inter-strand crosslinks that generate a matrix-like shell. PG biogenesis is disrupted by many of our most effective antibiotics and remains an attractive target for the development of new therapies to counter the growing problem of drug-resistant infections 2.

Rod-shaped bacteria typically use two essential cell wall biogenesis machines to grow and divide 1. Cell elongation is promoted by the Rod system, which consists of several integral membrane proteins, including RodA, a SEDS-family protein, and PBP2, a class B penicillin-binding protein (bPBP) with transpeptidase (TP) activity that forms cell wall crosslinks. The Rod system is organized by dynamic filaments of the actin homolog MreB that are thought to direct new cell wall synthesis to establish and maintain rod shape 1,3–7 (Fig. 1A). Cell division is mediated by a different multi-protein machine, the divisome, organized by the tubulin homolog FtsZ 1,8. The proteins composing the divisome are largely distinct from that of the Rod system, but it contains homologous factors for PG synthesis like the SEDS-family protein FtsW and PBP3, a bPBP related to PBP2 1.

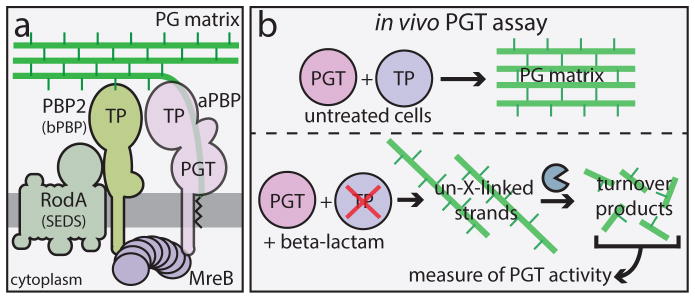

Fig. 1. The Rod system and an in vivo assay of peptidoglycan (PG) polymerase activity.

A. Diagram of the currently accepted model for PG biogenesis by the Rod system. Polymers of the actin-like MreB protein organize a complex of membrane proteins including RodA, PBP2, and an aPBP. Glycan polymerization and crosslinking by this complex is thought to be promoted primarily by the peptidoglycan glycosyltransferase (PGT) and transpeptidase (TP) activities of aPBPs with additional TP activity provided by PBP2. B. In untreated cells, PG polymerization and crosslinking by PGT and TP enzymes, respectively are tightly coupled to form the PG matrix (upper panel). When TP activity is inhibited by a beta-lactam, the polymerase working with the blocked TP continues to produce uncrosslinked glycans that are rapidly degraded into fragments that can be isolated and quantified as a measure of polymerase activity (lower panel).

Due to the lack of specific in vivo assays, the enzymes that synthesize PG glycans within the MreB- and FtsZ-directed machines have not been clearly defined. The generally accepted model is that glycan polymerization by these systems is mediated by the class A PBPs (aPBPs), which are bifunctional enzymes possessing both PG glycosyltransferase (PGT/polymerase) and TP (crosslinking) activity 1. In support of this idea, aPBP activity is indispensable for growth in many organisms 9–11. Additionally, aPBP-like PGT domains have been the only factors known to possess PG polymerase activity 12. However, this functional assignment fails to account for the observation that certain gram-positive bacteria, including Bacillus subtilis and some species of Enterococcus, are viable and continue producing PG in the absence of identifiable aPBP-like domains 13,14. Moreover, it has remained unclear whether this unidentified polymerase activity is unique to certain gram-positive species or broadly distributed in bacteria.

A novel in vivo assay for PG polymerase activity

To determine if PG synthesis by the Rod system is dependent on aPBP function, we developed an in vivo assay to monitor PG polymerase activity. The assay is based on our observation that TP inactivation by beta-lactams in E. coli leads to the formation of uncrosslinked PG glycans that are rapidly degraded into turnover products, which can then be quantified as an indirect measure of PG polymerase activity 15,16 (Fig 1B). Because it specifically targets PBP2, the beta-lactam mecillinam facilitates the measurement of polymerase activity within the Rod system 15. In this assay, cells are first blocked for divisome function, thus eliminating its contribution to synthesis and focusing the measurement on Rod system activity. Under these conditions, mecillinam treatment reduces the ability of cells to incorporate the radiolabeled PG precursor [3H]-diaminopimelic acid ([3H]-DAP) into the PG matrix. Instead, a dramatic increase in labeled turnover products is observed, which reflects PG polymerization by the Rod system 15 (Fig. 2A–B, samples 1 and 2). Consistent with this interpretation, simultaneous mecillinam treatment and inactivation of the Rod system with A22, an MreB polymerization antagonist, dramatically reduces both synthesis and turnover (Fig. 2A–B, samples 1 and 6) 15.

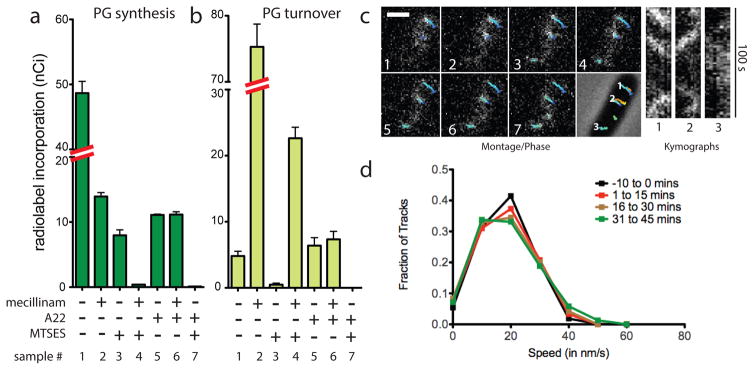

Fig. 2. PG polymerization by the Rod complex does not require aPBP activity.

A–B. Cells of HC533(attλC739) [ΔlysA ΔampD ΔponA ΔpbpC ΔmtgA MSponB (Ptac::sulA)] producing SulA to block cell division were pulse labeled with [3H]-mDAP following treatment with the indicated compound(s). Turnover products were extracted with hot water and quantified by HPLC and in-line radiodetection. PG incorporation was determined by digesting the pellets resulting from the hot water extraction with lysozyme and quantifying the amount of label released into the supernatant by scintillation counting. Compound concentrations used were: mecillinam (10 μg/ml), A22 (10 μg/ml), MTSES (1 mM). Results are the average of three independent experiments with the error bars representing the standard error of the mean (SEM). C. Left: Montage with overlaid tracks highlighting MreB movement in HC546(attλHC897) [ΔponA ΔpbpC ΔmtgA MSponB (Plac::mreB-SWmNeon)] after 30 min MTSES inactivation of PBP1b showing continuing MreB motion. Frames 2 s apart, scale bar = 1 μm. Original time-lapse movies are 1 sec/frame. Right top: Kymographs drawn along trajectories indicated on phase contrast image (1, 2, 3, left to right). Each tracked particle is highlighted with a colored trajectory with the color of the track (blue to red) indicating the passage of time. D. Distribution of velocities of MreB motion taken at different points after aPBP inhibition with MTSES (1 mM). For the tracks that we can accurately calculate a particle’s velocity, the fraction of moving particles only declines slightly (from 76% to 66%) during the time course following MTSES treatment. Microscopy results are representative of at least two independent experiments.

PG polymerization by the Rod system does not require aPBP activity

The effect of aPBP inactivation on Rod system activity was investigated using an E. coli strain (HC533) producing a modified PBP1b as its only aPBP. This variant of PBP1b, referred to as MSPBP1b, harbors a Ser247Cys substitution in its PGT domain allowing specific inhibition of its polymerase activity using the cysteine-reactive reagent MTSES (2-sulfonatoethyl methanethiosulfonate) 17. In the absence of MTSES, HC533 cell growth and morphology were indistinguishable from WT cells, and PG biogenesis activity was similar to cells producing an unaltered copy of PBP1b (Fig. S1A–C). Treatment of [3H]-DAP labeled, division-inhibited HC533 cells with MTSES reduced PG synthesis without stimulating turnover (Fig. 2A–B, sample 3). This level of PG synthesis inhibition was similar to that observed upon treatment of an outer-membrane defective strain with the canonical PGT inhibitor moenomycin (Fig. S1D). Surprisingly, however, these MTSES-treated cells retained significant (~20%) PG synthetic activity (Fig. 2A–B, sample 3). This synthesis was not due to residual MSPBP1b activity as analysis by mass spectrometry indicated that the protein was fully modified by MTSES (Table S1 and Fig. S2), and experiments with the beta-lactam cefsulodin (described below) show that this treatment completely disrupts aPBP-mediated PG polymerization. Thus, the observed MTSES-resistant synthesis suggests that, like gram-positive bacteria, E. coli also encodes a non-aPBP-mediated PGT activity. This MTSES-resistant synthesis was inhibited by co-treatment with A22 and fully converted to PG turnover products with mecillinam co-treatment (Fig. 2A–B, samples 4 and 7), indicating that the non-aPBP PGT enzyme resides in the Rod system.

Fluorescently-tagged MreB displays a dynamic subcellular localization with many discrete foci rotating around the circumference of the cell cylinder 4–6. As MreB rotation is halted by beta-lactams and other PG synthesis inhibitors, this motion is thought to reflect new cell wall synthesis 4–6. To monitor the effect of aPBP inactivation on MreB dynamics, we followed the motion of a functional mNeonGreen-MreB sandwich fusion (MreB-SWmNeon) (Fig. S3) in cells possessing MSPBP1b as the sole aPBP. MreB-SWmNeon foci continued rotating following aPBP inhibition by MTSES at a speed undifferentiable from untreated cells (20 nm/s) until the lack of aPBP activity caused cell lysis (Fig. 2C–D, Supplemental Video S1). Thus, both radiolabeling and imaging indicate that aPBPs are not required for PG polymerization by the Rod system in gram-negative bacteria as is widely believed.

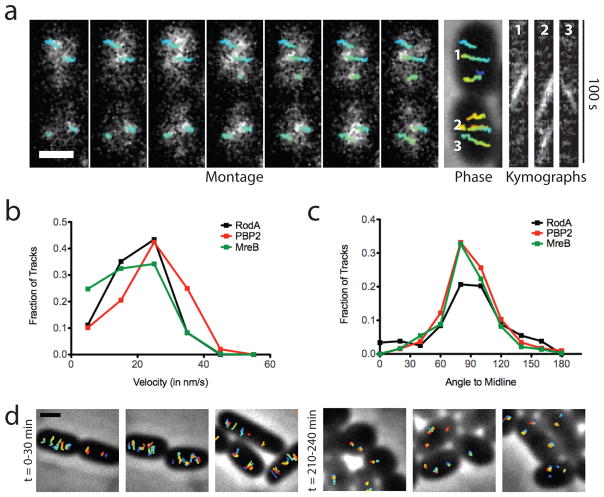

RodA and PBP2 display MreB-like circumferential motion in E. coli

Results from a parallel B. subtilis study indicate that RodA functions as a PG polymerase 18. We therefore hypothesized that RodA might also be responsible for the aPBP-independent PG synthesis we observed in E. coli. If true, we reasoned that E. coli RodA should display MreB-like circumferential motion as has been observed in B. subtilis 5. Imaging of a mostly functional sfGFP-RodA fusion (Fig. S4 A and B) revealed both fast, non-directionally moving particles consistent with molecules diffusing in the membrane, and particles moving slowly and directionally at the same rate and angle as MreB (Fig. 3 and S5, and Supplemental Video S2). SEDS-family proteins form complexes with partner bPBPs 1,19,20, suggesting that RodA is likely to function in conjunction with PBP2. We therefore also investigated PBP2 dynamics using a functional msfGFP-PBP2 fusion (Fig. S4A, C, and D, and Supplemental Video S3). Imaging at fast acquisition rates (50 or 100 msec/frame) showed what appeared to be particles rapidly diffusing within the membrane as reported previously 21 (Supplemental Video S4). However, imaging with longer acquisition times (1 sec/frame), which blurs the motion of rapidly diffusing particles across many pixels, revealed a subpopulation of PBP2 foci moving slowly and directionally around the cell circumference at the same rate and angle as MreB and RodA (Fig. 3 and S6, Supplemental Video S4). These two types of PBP2 motions are analogous to what has been observed in B. subtilis for PBP2a 4. Similarly, we interpret the slow, rotating particles of RodA and PBP2 as those engaged in active, MreB-associated PG synthesis. To investigate whether RodA PGT activity is required for MreB motion, we monitored the effect of a dominant-negative RodA variant (D262N) (Fig. S7) on MreB-SWmNeon dynamics. This RodA derivative contains an amino acid change in a periplasmic loop residue critical for PGT activity 18. Strikingly, production of RodA(D262N) but not RodA(WT) led to a gradual, filament by filament cessation of MreB-SWmNeon motion (Fig. 3D, and Supplemental Video S5). We therefore infer that RodA and PBP2 function as the core PGT/TP pair of the Rod system in both E. coli and B. subtilis 18.

Fig. 3. PBP2 and RodA display directed, circumferential motions similar to MreB.

A. Left to right: Montage of PBP2 movement with overlaid tracks in HC596(attHKHC943) [ΔponA ΔpbpC ΔmtgA ΔpbpA (Plac::msfgfp-pbpA)]. Frames 2 s apart. Each tracked particle is highlighted with a colored trajectory as in Figure 2C. Trajectories 1, 2, and 3 in kymographs are in order left to right. B. Distribution of velocities of tracked particles of MreB (n = 807), PBP2 (n=1234) and RodA (n=243). C. Distribution of angles of PBP2 and RodA trajectories relative to the cell midline. D. Tracked particles of MreB-SWmNeon at 0–30 or 210–240 min after induction of RodA(D262N) from strain TB28(attHKHC929)/pHC938 [WT(PtetA::mreB-SWmNeon)/Plac::pbpA-rodA(D262N)]. Each tracked particle is highlighted with a different color trajectory overlaid on a phase contrast image. All scale bars are 1 μm. In all cases, original time-lapse movies are 1 sec/frame. Microscopy results are representative of at least two independent experiments.

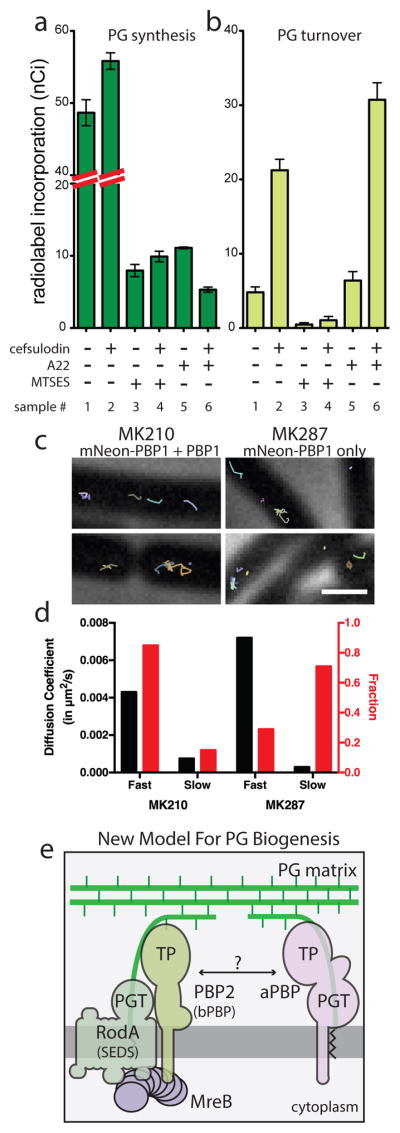

aPBPs function outside of cytoskeletal complexes in E. coli and B. subtilis

In current models of PG biogenesis, aPBPs are associated with either the MreB- or FtsZ-directed synthetic machineries 1, implying that they function primarily within these complexes and may require cytoskeletal association for activity. However, cell growth and cell wall synthesis by an uncharacterized activity was previously observed in cells blocked for both FtsZ and MreB function 22,23, suggesting a possible cytoskeleton-independent mode of PG synthesis. Indeed, when PG synthesis and turnover were measured in HC533 cells blocked for both FtsZ and MreB activity by SulA and A22, respectively, significant PGT activity was still detected (Fig. 2A, sample 5). This activity was completely inhibited upon MTSES treatment to inactivate MSPBP1b, indicating that cytoskeleton-independent synthesis is mediated by aPBPs (Fig. 2A, sample 7). To further test the dependence of aPBP polymerase activity on cytoskeletal function, we employed the aPBP-specific beta-lactam cefsulodin 24, which induces increased glycan degradation similar to mecillinam 15. This turnover likely reflects PGT activity promoted by aPBP molecules with a drug-inactivated TP active sites (Fig. 1B). Consistent with this interpretation, treatment of MSPBP1b-producing (HC533) cells with MTSES completely blocked cefsulodin-induced glycan degradation (Fig. 4A–B, samples 1 vs. 3, and 2 vs. 4). This result also supports the conclusion that MSPBP1b PGT activity is completely inactivated upon MTSES treatment. In contrast to MTSES addition, cefsulodin-induced turnover was stimulated by MreB depolymerization with A22 in cells already blocked for FtsZ activity by SulA (Fig. 4A–B, sample 5–6). Thus, glycan synthesis by PBP1b proceeds robustly in cells lacking all functional cytoskeletal filaments. Similarly, PG synthesis and turnover assays using cefsulodin and a strain where PBP1a was the sole remaining aPBP also detected cytoskeleton-independent glycan polymerization by PBP1a (Fig. S8). The functionality of aPBPs in the absence of cytoskeletal filaments suggests that aPBPs may operate in a spatially distinct manner from the MreB- and FtsZ-directed machineries. To investigate this possibility, we followed aPBP subcellular dynamics in both E. coli and B. subtiils. In E. coli, a functional msfGFP-PBP1b (Fig. S9) was produced as the sole aPBP. At the lowest induction level capable of supporting growth (13 μM), imaging at both long (1 sec) and short (100 msec) acquisition times like those used for PBP2 and RodA did not reveal any directional motion (Supplemental Video S6A). We verified this result using single-molecule imaging of a functional Halo-tagged PBP1b fusion (Halo-PBP1b) labeled with low concentrations of JF-549 {Grimm:2015cx} (Supplemental Video S6B). Only motion consistent with membrane diffusion was observed. Likewise, imaging msfGFP-PBP1b motion during its depletion also did not reveal any MreB-like directional motion even under conditions where depletion resulted in cell lysis. Furthermore, an msfGFP-PBP1a fusion produced as the sole aPBP in the cell also did not display MreB-like dynamics (Supplemental Video S7).

Fig. 4. aPBPs can function independently from the cytoskeletal machinery.

A–B. PG matrix assembly and turnover were measured as in Figure 2 using strain HC533(attλC739) [ΔlysA ΔampD ΔponA ΔpbpC ΔmtgA MSponB (Ptac::sulA)]. Cefsulodin was used at 100 μg/ml. Results are the average of three independent experiments with the error bars representing the SEM. C. Tracks of mNeon-PBP1 expressed as (right) the only copy or (left) in addition to native untagged protein in B. subtilis. Each continuously tracked particle is highlighted with a different color trajectory. Note that although no MreB-like directional motion was observed, particles occasionally travel rapidly in one direction for a few frames as expected for membrane diffusion. D. Graph showing diffusion constants, and fraction of particles tracked in each diffusion state as determined by CDF analysis. Microscopy results are representative of at least two independent experiments. E. Schematic view of a new model for PG biogenesis involving two different classes of PG polymerases working semi-autonomously. SEDS PGTs and partner bPBPs perform PG polymerization and crosslinking in the context of the Rod system and divisome (not shown) while aPBPs function outside of these complexes. Collaboration between the synthases likely occurs but the mechanism remains to be defined.

To determine if aPBPs also display dynamics distinct from the Rod system in gram-positive bacteria, we imaged a functional mNeon-PBP1 fusion (Fig. S10) produced in B. subtilis as the sole copy of PBP1 or alongside the native protein. No directional motion was observed either when the fusion was produced from its native promoter or at low levels that allowed single molecule tracking (Fig. 4C–D, S11, Supplemental Videos S8–10). Rather, analysis of single-molecule trajectories using cumulative distribution functions (CDF) 25,26 indicated that PBP1 exists in two states: diffusive (D = 0.004–0.007 μm2/s) and immobile (D = 0.0003–0.0007 μm2/s) (Fig. 4C–D, S11, Supplemental Videos S8–10). The slow, immobile particles predominated in cells producing mNeon-PBP1 as the sole source of PBP1 (Supplemental Video S9). When the fusion was expressed in addition to native PBP1, the fraction of faster diffusing molecules increased (Supplemental Video S10). This observation suggests a saturable number of available sites for the immobile particles that may reflect a functional state of PBP1. We conclude that aPBP polymerases from two different and evolutionarily distant model organisms display in vivo dynamics distinct from the circumferential motions observed for Rod system components.

A new view of PG biogenesis in bacteria

Overall, our results indicate that the aPBPs are not essential components of the Rod system in E. coli and suggest that these enzymes are performing significant roles in PG biogenesis apart from the complex. Instead of the aPBPs, the SEDS-protein RodA appears to supply the PG polymerase activity crucial for Rod system function 18. The RodA polymerase, in turn, likely works in complex with PBP2, which provides crosslinking activity. By extension, the SEDS-family FtsW protein and its partner PBP3 are likely providing PG polymerase and crosslinking activity within the divisome. These findings necessitate a fundamental change in our view of the mechanism of cell wall assembly in bacteria and furthermore raise intriguing questions about the relative roles of the different types of PG polymerases in the process (Fig. 4E).

Inactivation of aPBP activity reduces total cell wall synthesis to approximately 20% normal levels, indicating that these enzymes play major roles in PG biogenesis. The same is true when the cytoskeletal systems are inactivated and aPBPs remain functional; only about 20–30% of normal PG synthesis activity is detected. Thus, even though the aPBPs and Rod system components show distinct subcellular dynamics and are unlikely to be working stably together within the same complex, full cell wall synthesis efficiency requires that both systems be functional. Therefore, although our data support the idea that there is a division of labor between the aPBPs and the cytoskeleton-directed SEDS/bPBP systems, they appear to be only semi-autonomous and are likely collaborating with each other at some level. This partial interdependence may indicate that the two systems specialize in distinct but related aspects of the wall biogenesis process similar to how different DNA polymerases work together to properly complete chromosome replication. For example, the more broadly conserved SEDS/bPBP systems 18 may build the primary structural foundation for the PG matrix while the aPBPs support this foundation by adding to it and filling in gaps that arise during normal expansion and/or as the result of damage. Testing this and other possibilities in the context of the new framework provided in this and our companion report 18 will pave the way for a better mechanistic understanding of bacterial cell wall assembly and the discovery of novel ways to disrupt this process for antibiotic development.

Methods

Media, bacterial strains, plasmids, and culture conditions for E. coli strains

Cells were grown in LB (1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, 0.5% NaCl) or minimal M9 medium supplemented with 0.2% casamino acids (CAA) and carbon source (0.4% glycerol or 0.2% glucose or maltose) as indicated. The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Tables S2 and S3, respectively, and a description of their construction or isolation in the genetic selection is given below.

Construction of E. coli strains with multiple deletions

E. coli strains with multiple deletion mutations were made by sequential introduction of each deletion from the Keio mutant collection 27 via P1 transduction followed by removal of the aph cassette using FLP expressed from pCP20, leaving a frt scar sequence at each deletion locus. Correct orientation of the DNA flanking frt sequences in multiple deletion mutants was confirmed for all the deletions in each mutant.

Construction of an MTSES-sensitive E. coli PBP1b variant

To test the effect of aPBP inhibition on cell wall synthesis and turnover, we sought a way to rapidly block the PGT activity of aPBPs. Moenomycin, a known inhibitor of the PGT activity of aPBPs, is not ideal for aPBP inhibition in WT E. coli because it cannot cross the outer membrane layer to access aPBPs. Instead, it was recently shown that a small cysteine-reactive molecule, MTSES [sodium (2-sulfonatoethyl)methanethiosulfonate], can be used in conjunction with a cysteine-substitution mutant to specifically block the activity of a surface exposed enzyme 17. PBP1B was chosen for the development of a MTSES-blockable aPBP system because it is the major aPBP in E. coli and a structural information was also available for this protein 28. Thirteen cysteine substitution variants of PBP1b were constructed with changes mapping within the moenomycin binding surface of PBP1B 28. Alleles encoding each variant were cloned under control of the lac promoter in the CRIM plasmid pHC872 backbone (attHK022, Plac::ponB) and the resulting plasmids were integrated into HC518 [ΔponA::frt Para::ponB]. The functionality of each ponB allele was assessed by testing their ability to correct the PBP1a- PBP1b- synthetic lethality of HC518 grown on M9 glucose minimal medium supplemented with 100 μM IPTG.

Cysteine substitution mutants that were functional were further screened for the loss of activity upon MTSES treatment. This screen utilized the rapid lysis phenotype manifested in cells inhibited for aPBP activity in combination with 10 μg/mL cephalexin. Treatment of WT E. coli with 10 μg/mL cephalexin causes continued growth as cell filaments. However, lysis is observed in 20 min when aPBPs are also inhibited. We therefore screened the functional PBP1b cysteine substitution mutants for their response to treatment with 10 μg/mL cephalexin with or without 1 mM MTSES using a VersaMax microplate reader (Molecular Devices). PBP1b(S247C) was identified as a variant that supports the growth similar to WT PBP1b but specifically leads to rapid lysis when cells producing the variant as the main aPBP are treated with 10 μg/mL cephalexin and 1 mM MTSES.

Introducing ponB(S247C) mutation at the native E. coli locus

Allele exchange of ponB(247C) at the native locus was performed by using a temperature-sensitive plasmid pMAK700 as described 29. Eighteen hundred bases of DNA flanking the ponB(S247C) mutation were PCR amplified from pHC873 using primers 5′-GCTAATCGATGAAAATCGGGCTTTTGCGCCTGAATATTGC-3′ and 5′-GCTAGCTAGCAGATTTACCGTCGGCACGTTCATCG-3′. The resulting PCR product was digested with NheI and ClaI and ligated with pMAK700 digested with the same enzymes to generate pHC878. Plasmid integration and excision events at the ponB locus were selected utilizing the temperature-sensitive replication initiation of pHC878 to obtain strains with ponB(S247C) mutation at the native chromosomal locus.

Introduction of the imp4213 allele

The imp4213 allele was introduced into recipient strains by P1 transduction using its genetic linkage to leu marker. First, a leu::Tn10 marker was introduced into the recipient strains by selecting for tetracycline resistance. Then, imp4213 was introduced into the leu auxotrophs by P1 transduction followed by selection for leucine prototrophy on M9-glucose agar plates. For efficient P1 lysate preparation from an imp4213 strain, a strain that has a suppressor mutation at the bamA locus in addition to imp4213 (JAB027) was used. The resulting P1 transductants were screened for the sensitivity to 10 μg/mL erythromycin to identify isolates that acquired imp4213 allele along with the WT leu locus.

Generation of mreB sandwich fusions at the native E. coli mre locus

Sandwich fluorescent protein fusions of mreB were introduced at the native locus using the recombineering strain CH138/pCX16, which harbors a defective lambda prophage as a temperature-inducible source of the recombination genes 30. CH138/pCX16 is also deleted for native galK and has a galK cassette inserted in the middle of mreB (replacing the codon for G228). The strain is viable due to suppression of the Rod system defect by elevated FtsZ levels promoted by sdiA on pCX16. Fragments with one kb of sequence flanking mNeonGreen or mCherry in plasmid-borne mreB-fluorescent protein sandwich fusions were amplified with the primers 5′-AACGGTGTGGTTTACTCCTCTTCTGTG-3′ and 5′-TTCCAGTGCAACCATTACCGCGCTCAC-3′ using pFB262 or pHC892 as templates. After the recombineering with the resulting PCR products, cells that replaced galK with fluorescent protein fusions at the mreB locus were selected on M9 minimal agar containing 0.2% 2-deoxy-galactose, which is converted to toxic 2-deoxy-galactose-1-phosphate if cells remain GalK+.

Generation of E. coli ΔrodA::aph

A rodA deletion was constructed similar to deletions in the Keio collection 27 using a TB10(attHKCS8) recombineering strain that expresses rodA under control of the lac promoter. A PCR product for ΔrodA::aph construction was amplified using pKD13 31 as a template with the primers 5′-AAAATCCAGCGGTTGCCGCAGCGGAGGACCATTAATCATGATTCCGGGGATCCGTCGACC-3′ and 5′-CTTACGCATTGCGCACCTCTTACACGCTTTTCGACAACATTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTCG-3′ and recombineering was performed as described previously 32.

E. coli plasmid construction

pHC872 and pHC873

The ponB gene was amplified with primers 5′-GTCATCTAGAGAAAATCGGGCTTTTGCGCCTG-3′ and 5′-GTCACTCGAGATGGGATGTTATTTTACCGGATGGC-3′. The resulting fragment was digested with XbaI and XhoI and ligated to pTB183 digested with XbaI and SalI to generate pMM15. The bla antibiotic resistance cassette of pMM15 was replaced with a cat cassette from pHC514 by replacing the NotI-XbaI fragment to generate pHC872. The ponB(S247C) mutation was introduced in pHC872 using QuikChange mutagenesis with the primer 5′-CATGATGGAATCAGTCTCTACTGCATCGGACGTGCGGTGCTGGCA-3′ to generate pHC873.

pHC897

The mCherry sequence of pFB262 was replaced with E. coli codon-optimized mNeonGreen (IDT synthesis) using XhoI and AscI to generate pHC892. The mreB-SWmNeon fragment of pHC892 was removed with XbaI and HindIII and cloned under control of the lac promoter of a pHC514 derivative to generate pHC897.

pHC929

The mreB-SWmNeon fragment was liberated from pHC892 by digestion with XbaI and HindIII and tetR-PtetA (IDT synthesis) digested with BglI and XbaI were assembled in a pTB183 derivative using BglII and HindIII to generate pHC929.

pHC938

pHC938 was generated by introducing the rodA(D262N) mutation into pHC857 using an overlap extension mutagenesis protocol. rodA(D262N) was amplified using primers 5′-AAATCCGGTACCGCTCAGGTC-3′ and 5′-GTATCGGTGATAAGCTTCTGC-3′ and a mutagenizing primer set 5′-CCGAACGCCATACTAACTTTATCTTCGCGGTACTGG-3′ and 5′-GCGAAGATAAAGTTAGTATGGCGTTCGGGGAGAAATTC-3′. The mutated base is indicated in bold. The resulting PCR product for rodA(D262N) was digested with KpnI and HindIII and ligated to pHC857 digested with the same enzymes to generate pHC938.

pHC933

The sfgfp fragment was liberated from pTB230 with XbaI and BamHI digestion and rodA amplified with 5′-GTCAGGATCCGAGGCCATTACGGCCATGACGGATAATCCGAATAAAAAAACATTCTGGG-3′ and 5′-GTCAGTCGACTTATTATTGGCCGAGGCGGCCTTACACGCTTTTC-3′ and digested with BamHI and SalI. The fragments were assembled in pNP20 using XbaI and SalI to generate pHC933.

pHC942, pHC943, and pPR104

E. coli codon-optimized msfgfp (IDT synthesis) digested with XbaI and BamHI, and the ponB sequence amplified with 5′-GTACGGATCCCCGCGCAAAGGTAAGGG-3′ and 5′-GTCACTCGAGATGGGATGTTATTTTACCGGATGGC-3′ and digested with BamHI and XhoI were assembled in pNP20 by using XbaI and SalI to generate pHC942. The ponB of pHC942 was then replaced with pbpA sequence amplified with 5′-GCTAGGATCCAAACTACAGAACTCTTTTCGCGACTATACG-3′ and 5′-CTTCACGTTCGCTCGCGTATCGGTG-3′ using BamHI and HindIII to generate pHC943. pPR104 was constructed by replacing ponB of pHC942 with ponA sequence amplified with 5′-GCTAGGATCCAAGTTCGTAAAGTATTTTTTGATCC-3′ and 5′-GCTAAAGCTTAGAACAATTCCTGTGCCTCGCCAT-3′ using BamHI and HindIII.

pHC949

HaloTag sequence was amplified by using pDHL940 as a template with 5′-GCTATCTAGATTTAAGAAGGAGATATACATATGGCAGAAATCGGTACTGGCTTTCCATTC-3′ and 5′-GCTAGGATCCGGAAATCTCCAGAGTAGACAGC-3′. The resulting PCR product was digested with XbaI and BamHI, and ligated to pHC942 digested with the same enzymes to replace msfgfp sequence with HaloTag sequence.

Measurement of PG synthesis and turnover

The effect of blocking aPBP activity with MTSES on PG synthesis and turnover in beta-lactam-treated E. coli cells was examined essentially as described previously 15. HC533(attλHC739), a ΔlysA ΔampD strain which expresses PBP1b(S247C) as a sole aPBP, was grown overnight in M9-glycerol medium supplemented with 0.2% casamino acids. The overnight culture was diluted to an OD600 = 0.04 in the same medium and grown to an OD600 between 0.26 – 0.3. Then, divisome formation was blocked by inducing sulA expression for 30 min from a chromosomally integrated Ptac::sulA construct (pHC739) by adding IPTG to 1 mM. After adjusting the culture OD600 to 0.3, MTSES (1 mM), A22 (10 μg/mL), mecillinam (10 μg/mL), and/or cefsulodin (100 μg/mL) were added to the final concentrations indicated and cells were incubated for 5 min. Following drug treatment, 1 μCi of [3H]-meso-2,6-Diaminopimelic acid (mDAP) was added to 1 mL of each drug-treated culture and incubated for 10 min to label the newly synthesized PG and its turnover products. After the labeling, cells were pelleted, resuspended in 0.7 ml water, and heated at 90°C for 30 min to extract water-soluble compounds. After the hot water extraction, insoluble material was pelleted by ultracentrifugation (200,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C). The resulting supernatant was then removed, lyophilized, and resuspended in 0.1% formic acid for HPLC analysis and quantification of turnover products as described previously 15. To determine [3H]-mDAP incorporated into the PG matrix, the pellet fraction was washed with 0.7 mL buffer A (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 25 mM NaCl) and resuspended in 0.5 mL buffer A containing 0.25 mg lysozyme. The suspensions were incubated overnight at 37°C. Insoluble material was then pelleted by centrifugation (21,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C), and the resulting supernatant was mixed with 10 mL EcoLite (MP biomedicals) scintillation fluid and quantified in Microbeta Trilux 1450 liquid scintillation counter (Perkin-Elmer).

Quantification of MTSES labeling of PBP1b(S247C)

To quantify the efficiency of MTSES binding to PBP1b(S247C) under experimental growth conditions, a culture of HC533(attλHC739) (100 mL) was grown to OD600 = 0.3 in M9-glycerol medium supplemented with 0.2 % casamino acids at 30°C with sulA induction for 30 minutes. Then, the culture was split into two 50 mL portions and treated with either 1 mM MTSES or DMSO for 5 min. Immediately after MTSES/DMSO treatment, cultures were cooled on ice and cells pelleted at 4,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C. The cell pellets were washed once with 1X ice-cold PBS, resuspended in 500 μL 1X PBS containing 10 mM EDTA and 20 mM 2-iodoacetamide, and incubated for 20 min at room temperature to alkylate the cysteine residues not modified by MTSES. After the 20 min incubation, 20 kU of Ready-lyse lysozyme (Epicentre) was added to each cell suspension and incubation was continued for a further 10 min at room temperature. Cells were disrupted by sonication and membrane fractions were pelleted by ultracentrifugation at 200,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C. The membrane fractions were then washed with 1X PBS once and resuspended in 1 mL immunoprecipitation (IP) buffer (100 mM Tris, pH7.4, 300 mM NaCl, 2% Triton X-100). Ten micrometers of anti-PBP1b antiserum was added to the resuspension and the resuspension was incubated overnight in the cold room with gentle agitation. The samples were then mixed with 50 μL of IP buffer-equilibrated protein A/G magnetic beads (Millipore) and incubated for further 4 hrs in the cold room with gentle agitation. Then, the beads were washed three times with IP buffer and then three times with a buffer containing 100 mM Tris, pH7.4 and 300 mM NaCl.

Proteins bound on the beads were fragmented by on-bead digestion with 0.1μg trypsin (#V511C, Promega) in 300μl buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH8, 150 mM NaCl) overnight at 37°C with gentle agitation. After digestion, peptide samples were acidified with 10% TFA to a pH between 1–2, desalted using a 96-well plate embedded with C18 resin (Thermo Scientific) and dried by vacuum centrifugation. Samples were resolubilized in 20 μl of 0.1% TFA and 5 μl of each sample was analyzed by nanoLC-MS/MS 33 with a HPLC gradient (NanoAcquity UPLC system, Waters; 5%–35% B in 110 min; A=0.1% formic acid in water, B=0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile). Peptides were resolved on a self-packed analytical column (50 cm Monitor C18, Column Engineering) and introduced to the mass spectrometer (Q Exactive HF) at a flow rate of 30 nl/min (ESI spray voltage=3.5 kV). The mass spectrometer was programmed to operate in data dependent mode such that the ten most abundant precursors in each full MS scan (resolution=120 K; target=5e5; maximum injection time=500 ms; scan range= 300 to 2,000 m/z) were subjected to HCD (resolution=15 K; target=5e4; maximum injection time=200 ms; isolation window=1.6 m/z; NCE=27, 30; dynamic exclusion=15 seconds). MS/MS spectra were matched to peptide sequences using Mascot (version 2.2.1) after conversion of raw data to .mgf using multiplierz scripts 34. Search parameters specified trypsin digestion with up to two missed cleavages, as well as variable oxidation of methionine and carbamidomethylation of cysteine residues. Precursor and product ion tolerances were 10 ppm and 25 mmu, respectively. Targeted scan experiments were performed in a similar fashion while dynamic exclusion was disabled and inclusion was enabled for the following peptides: HFYEHDGISLYCIGR (carbamidomethyl cysteine: z=4, m/z=467.4703; z=3, m/z=622.9579; z=2, m/z=933.9332), HFYEHDGISLYCIGR (MTSES-cysteine: z=4, m/z=488.2050; z=3, m/z=650.6042; z=2, m/z=975.4026), VWQLPAAVYGR (z=2, m/z=630.3484), LLEATQYR (z=2, m/z=497.2718), QFGFFR (z=2, m/z=401.2058), DSDGVAGWIK (z=2, m/z=524.2589). Peak area integration was carried out using the Thermo Xcalibur Qual Browser (version 3.0.63, Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Bocillin-binding assays

Cultures of HC545, HC596(attHKHC943), and HC576(attHKHC942) were grown overnight at 37°C in M9-glucose medium supplemented with 0.2% casamino acids, with induction of msfgfp-pbpA or msfgfp-ponB with 25 μM IPTG. Cells in the overnight cultures were washed to remove IPTG and diluted to an OD600 = 0.001 in 15 ml of M9-glucose medium supplemented with 0.2% casamino acids and the indicated concentrations of IPTG. The cultures were then incubated at 37°C until the OD600 reached 0.4 to 0.5. A subset of cultures were treated with 10 μg/mL mecillinam (specific for PBP2) or 100 μg/mL cefsulodin (specific for PBP1b) for 5 min prior to harvesting. Cells were then harvested by centrifugation at 4°C, washed with ice-cold 1X phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) twice, resuspended in 500 μL 1X PBS containing 10 mM EDTA and 15 μM Bocillin (Invitrogen), and incubated at room temperature for 15 min. After the incubation, the cell suspensions were washed with 1X PBS once, resuspended in 500 μL 1X PBS, and disrupted by sonication. After a brief spin for 1 min at 4,000 × g to remove undisrupted cells, membrane fractions were pelleted by ultracentrifugation at 200,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C. The membrane fractions were then washed with 1X PBS and resuspended in 50 μL 1X PBS. Resuspended samples were mixed with 50 μL 2X Laemmli sample buffer and boiled for 10 min at 95°C. After measuring the total protein concentrations of each sample with NI-protein assay (G-Biosciences), 25 μg of total protein for each sample was then separated on a 10% SDS-PAGE gels and the labeled proteins were visualized using a Typhoon 9500 fluorescence imager (GE Healthcare) with excitation at 488 nm and emission at 530 nm.

Bocillin-binding assays for Bacillus subtilis strains were performed basically in the same way as in E. coli strains. Overnight cultures grown in CH medium at room temperature were diluted to OD600 = 0.04 – 0.07 in 5 mL fresh CH medium containing the indicated concentrations of IPTG and incubated at 37°C. When the cultures reached exponential phase, cells were pelleted, washed with ice-cold 1X PBS, and resuspended with 100 μL 1X PBS containing 15 μM Bocillin (Invitrogen), and incubated for 15 min at room temperature. Then, cells were washed in 1X PBS, resuspended 0.5 mL 1X PBS containing 20 kU Ready-lyse lysozyme (Epicentre), and incubated for 15 min at room temperature. The cells were disrupted by sonication and the membrane fraction was isolated by ultracentrifugation. A total of 16 μg of protein for each sample was separated on a 10% SDS-PAGE gels and visualized as described above for E. coli.

Microscopy of E. coli cells

Overnight cultures with strain-specific inducer levels were diluted in fresh culture medium and grown for at least 3 hours at 37 °C to an OD600 below 0.6. Cells were concentrated by centrifugation at 7,200 × g for 3 min and applied to No. 1.5 cover glass under 5 % agarose pads with culture medium, except for microscopy with MTSES, which was performed using the CellASIC ONIX microfluidic platform from EMD Millipore.

For msfGFP-PBP2 tracking, M9-glucose-CAA medium was used with 25 μM IPTG. For sfGFP-RodA tracking, M9-maltose-CAA medium was used with 80 μM IPTG. For msfGFP-PBP1b imaging, M9-glucose-CAA medium was used with a beginning concentration of 20 μM IPTG, diluted to 13 μM final IPTG before expansion at 37 °C. For MreB-SWNeon tracking with MTSES treated cells, M9-glucose-CAA medium was used with 100 μM.

For MreB-SWNeon tracking following RodA(WT) or RodA(D262N) overproduction, M9-maltose-CAA medium was used with the addition of 0.8 ng/μL anhydrotetracycline before growth at 37 °C. For experiments following the effect of RodA variant production after 210 min induction, cells were first grown in liquid culture for 120 min under inducing conditions (1 mM IPTG) before concentration and imaging. IPTG (1 mM) was included in the agarose pads used for imaging.

Microscopy of B. subtilis cells

Overnight cultures grown in CH medium were diluted in fresh medium and grown for at least 3 hours at 37 °C to an OD600 below 0.3. Cells were concentrated by centrifugation at 6000 × g for 30 seconds and applied to No. 1.5 cover glass under 2 % agarose pads with CH medium. For PBP1 imaging, no inducer was added to the cultures; leaky expression of mNeonGreen-PBP1 was sufficient for particle tracking experiments. All cells were imaged at 37 °C under an agar pad with the top surface exposed to air.

For measurements of growth rate, overnight cultures grown in LB medium were diluted in fresh medium and grown for at least 3 hours at 37 °C and to an OD600 below 0.3. The culture was diluted to an OD600 of 0.07, and its growth curve was measured in a Growth Curves USA Bioscreen-C Automated Growth Curve Analysis System.

For measurements of cell widths, overnight cultures grown in CH medium were diluted in fresh medium (with addition of 10 μM IPTG where indicated) for at least 3 hours at 37 °C and to an OD600 below 0.3. Cells were stained with FM 5–95 (ThermoFisher Scientific) and imaged under agarose pads as described above.

Particle Tracking Microscopy

Total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy (TIRF-M) and phase contrast microscopy were performed using a Nikon Eclipse Ti equipped with a Nikon Plan Apo λ 100X 1.45 objective and a Hamamatsu ORCA-Flash4.0 V2 (C11440-22CU) sCMOS camera. Except where specified, fluorescence time-lapse images were collected by continuous acquisition with 1,000 ms exposures. Microscopy was performed in a chamber heated to 37 °C.

Widefield Epifluorescence Microscopy

Widefield epifluorescence microscopy was performed on the instrument described above, and for some samples, on a DeltaVision Elite Microscope equipped with an Olympus 60x Plan Apo 60x 1.42 NA objective and a PCO.edge sCMOS camera. Cell contours and dimensions were calculated using the Morphometrics software package {Ursell:vg}.

Particle tracking

Particle tracking was performed using the software package FIJI 35,36 and the TrackMate plugin. For calculation of particle velocity, the scaling exponent α, and track orientations relative to the midline of the cell, only tracks persisting for 7 frames or longer were used. Particle velocity for each track was calculated from nonlinear least squares fitting using the equation MSD(t) = 4Dt + (vt)2,

where MSD is mean squared displacement, t is time interval, D is the diffusion coefficient, and v is speed. The maximum time interval used was 80 % of the track length. Tracks were excluded from further evaluation if the contribution of directional motion to the MSD was less than 0.01 nm/s. Tracks were also excluded if R2 for log MSD versus log t was less than 0.9, indicating a poor ability to fit the MSD curve. For PBP2, R2 and speed filtering together resulted in the exclusion of ~50 % of detected tracks. Track overlays in figures include all tracks 7 frames or longer to illustrate the performance of the track detection algorithms.

Track angles relative to the cell axis were taken to be the direction of the line produced by orthogonal least squares regression using all of the points in each track; cell axis angles were determined by finding cell outlines and axes using the Morphometrics software package {Ursell:vg}.

Analysis of PBP1 diffusion

Tracking of B. subtilis mNeon-PBP1 in strains MK210 and MK287 was performed using the u-track 2.0 software package 23. Resulting trajectories were then manually filtered to minimize particle detection and linking errors. The frame-to-frame vector displacements along these trajectories were then calculated. The magnitude of each of the displacements was taken, and the cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the pool of displacements across all movies in a condition was calculated. The CDF of the displacement magnitudes was then fit to an analytical function describing a diffusion process whereby one or more unique states of diffusion were occurring. The analytical form of the two-state model used in the results is:

where P(r, Δt) is the cumulative probability of a displacement of magnitude r given the observation period Δt, diffusion coefficients D1, D2 and the relative fractions between those two states w. For a simpler, one-state model, w = 1.

The fitting was performed in MATLAB using a nonlinear least-squares algorithm with 500 restarts to the initial parameters so as to find a close approximation to the true parameters of the model. Residuals of the model fit were calculated and used in the determination of the number of distinct diffusive species present within the dataset.

B. subtilis strain construction

For MK005 [ΔponA] construction, the homology region upstream of ponA was amplified from Py79 DNA using oligos oMK001 and oMK002. The cat cassette was amplified from pGL79 using oligos oJM28 and oJM29. The homology region downstream of ponA was amplified from Py79 DNA using oligos oMK006 and oMK013. The three fragments were fused using isothermal assembly 38 and transformed into Py79 to give MK005 by selecting on chloramphenicol agar.

For MK095, a native functional fusion of mNeonGreen to PBP1 was constructed by isothermal assembly 38 and was recombined into the chromosome of Py79 using counterselection to produce a marker-less strain without any remaining scars. The homology region upstream of ponA, fused to the first 30 bases of the coding sequence of mNeonGreen, was amplified from Py79 DNA using oMK001 and oMK027. The cat cassette, the Pxyl promoter sequence, and the mazF coding sequence were amplified as a fused fragment from template DNA using primers oMK047 and oMK086. The coding sequence of mNeonGreen was amplified from a gBlock using primers oMK078 and oMK087. The downstream homology region encoding a portion of the PBP1 (ponA) coding sequence was amplified from Py79 DNA using oMK009 and oMK050. These fragments were fused using isothermal assembly and transformed into Py79 to give MK093 upon selection for chloramphenicol resistance. Since the primers oMK078 and oMK009 contained the sequence for a 15-amino acid flexible linker, the fused product encoded an mNeonGreen-PBP1 fusion protein. The presence of a fragment of the mNeonGreen coding region upstream of cat provided a direct repeat to allow for spontaneous removal of the cat-mazF sequence by recombination. MK093 was grown in LB medium for 4 hours to allow time for recombination, and 200 μl cells were plated on a LB plate containing 30 mM xylose. This selected for cells in which removed the cat-mazF, yielding a scar-less functional fusion protein under the control of the native PBP1 promoter.

Strains MK210 and MK287 encoding an inducible version of the mNeonGreen-PBP1 fusion protein were constructed by isothermal assembly. The homology region upstream of amyE, the erm cassette, and the LacI-Phyperspank promoter construct were amplified as a fused fragment from template DNA using primers oMD191 and oMD232. The mNeonGreen-PBP1 coding sequence was amplified from MK095 DNA using primers oMK100 and oMK138. The homology region downstream of amyE was amplified from Py79 DNA using oMD196 and oMD197. The fragments were fused using isothermal assembly and transformed into Py79 to give MK210. Genomic DNA from MK005 (ΔponA::cat) was transformed into MK210 to give MK287, a strain in which the mNeonGreen-PBP1 fusion protein was the only copy of PBP1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all members of the Bernhardt, Rudner, and Garner labs for helpful advice and discussions. We also thank Piet de Boer and Cynthia Hale for the gift of the mreB::galK strain for constructing sandwich fusions. We thank Luke Lavis for his generous gift of JF dyes. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01AI083365 to TGB, AI099144 to TGB, CETR U19 AI109764 to TGB, and DP2AI117923 to ECG). ECG was also supported by a Smith Family Award and a Searle Scholar Fellowship. PDAR was supported in part by a pre-doctoral fellowship from CHIR. JAM was supported by Dana-Farber Strategic Research Initiative.

Footnotes

Author Contributions:

TGB, ECG, HC, CNW, MK, ZB, PDAR, and HS designed the experiments and wrote/edited the manuscript. HC performed the radiolabeling studies and constructed E. coli strains for physiological labeling and imaging studies. CNW and MK performed imaging studies and analysis. ZB performed CDF analysis. HC and HS performed LCMS study of MSPBP1b modification. MK constructed B. subtilis strains. PDAR constructed and characterized the dominant-negative RodA variants and made E. coli PBP1a fusion strains for imaging.

References

- 1.Typas A, Banzhaf M, Gross CA, Vollmer W. From the regulation of peptidoglycan synthesis to bacterial growth and morphology. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2012;10:123–136. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKenna M. Antibiotic resistance: The last resort. Nature. 2013;499:394–396. doi: 10.1038/499394a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones LJ, Carballido-López R, Errington J. Control of cell shape in bacteria: helical, actin-like filaments in Bacillus subtilis. Cell. 2001;104:913–922. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00287-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garner EC, et al. Coupled, circumferential motions of the cell wall synthesis machinery and MreB filaments in B. subtilis. Science. 2011;333:222–225. doi: 10.1126/science.1203285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Domínguez-Escobar J, et al. Processive movement of MreB-associated cell wall biosynthetic complexes in bacteria. Science. 2011;333:225–228. doi: 10.1126/science.1203466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Teeffelen S, et al. The bacterial actin MreB rotates, and rotation depends on cell-wall assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:15822–15827. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108999108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ursell TS, et al. Rod-like bacterial shape is maintained by feedback between cell curvature and cytoskeletal localization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:E1025–34. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1317174111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bi EF, Lutkenhaus J. FtsZ ring structure associated with division in Escherichia coli. Nature. 1991;354:161–164. doi: 10.1038/354161a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yousif SY, Broome-Smith JK, Spratt BG. Lysis of Escherichia coli by beta-lactam antibiotics: deletion analysis of the role of penicillin-binding proteins 1A and 1B. J Gen Microbiol. 1985;131:2839–2845. doi: 10.1099/00221287-131-10-2839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoskins J, et al. Gene disruption studies of penicillin-binding proteins 1a, 1b, and 2a in Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:6552–6555. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.20.6552-6555.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paik J, Kern I, Lurz R, Hakenbeck R. Mutational analysis of the Streptococcus pneumoniae bimodular class A penicillin-binding proteins. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:3852–3856. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.12.3852-3856.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sauvage E, Kerff F, Terrak M, Ayala JA, Charlier P. The penicillin-binding proteins: structure and role in peptidoglycan biosynthesis. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2008;32:234–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McPherson DC, Popham DL. Peptidoglycan synthesis in the absence of class A penicillin-binding proteins in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:1423–1431. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.4.1423-1431.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rice LB, et al. Role of class A penicillin-binding proteins in the expression of beta-lactam resistance in Enterococcus faecium. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:3649–3656. doi: 10.1128/JB.01834-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cho H, Uehara T, Bernhardt TG. Beta-lactam antibiotics induce a lethal malfunctioning of the bacterial cell wall synthesis machinery. Cell. 2014;159:1300–1311. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uehara T, Park JT. Growth of Escherichia coli: significance of peptidoglycan degradation during elongation and septation. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:3914–3922. doi: 10.1128/JB.00207-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sham LT, et al. Bacterial cell wall. MurJ is the flippase of lipid-linked precursors for peptidoglycan biogenesis. Science. 2014;345:220–222. doi: 10.1126/science.1254522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meeske AJ, et al. SEDS proteins are a widespread family of bacterial cell wall polymerases. Nature. 2016 doi: 10.1038/nature19331. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fay A, Meyer P, Dworkin J. Interactions between late-acting proteins required for peptidoglycan synthesis during sporulation. J Mol Biol. 2010;399:547–561. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.04.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fraipont C, et al. The integral membrane FtsW protein and peptidoglycan synthase PBP3 form a subcomplex in Escherichia coli. Microbiology. 2011;157:251–259. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.040071-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee TK, et al. A dynamically assembled cell wall synthesis machinery buffers cell growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:4554–4559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1313826111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Varma A, de Pedro MA, Young KD. FtsZ directs a second mode of peptidoglycan synthesis in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:5692–5704. doi: 10.1128/JB.00455-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tan Q, Awano N, Inouye M. YeeV is an Escherichia coli toxin that inhibits cell division by targeting the cytoskeleton proteins, FtsZ and MreB. Molecular Microbiology. 2011;79:109–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07433.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Curtis NA, Orr D, Ross GW, Boulton MG. Affinities of penicillins and cephalosporins for the penicillin-binding proteins of Escherichia coli K-12 and their antibacterial activity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1979;16:533–539. doi: 10.1128/aac.16.5.533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vrljic M, Nishimura SY, Brasselet S, Moerner WE, McConnell HM. Translational diffusion of individual class II MHC membrane proteins in cells. Biophys J. 2002;83:2681–2692. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75277-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schütz GJ, Schindler H, Schmidt T. Single-molecule microscopy on model membranes reveals anomalous diffusion. Biophys J. 1997;73:1073–1080. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78139-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baba T, et al. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol Syst Biol. 2006;2 doi: 10.1038/msb4100050. 2006.0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sung MT, et al. Crystal structure of the membrane-bound bifunctional transglycosylase PBP1b from Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:8824–8829. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904030106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cho H, McManus HR, Dove SL, Bernhardt TG. Nucleoid occlusion factor SlmA is a DNA-activated FtsZ polymerization antagonist. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:3773–3778. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018674108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Warming S, Costantino N, Court DL, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG. Simple and highly efficient BAC recombineering using galK selection. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:e36–e36. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu D, et al. An efficient recombination system for chromosome engineering in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:5978–5983. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100127597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ficarro SB, et al. Improved electrospray ionization efficiency compensates for diminished chromatographic resolution and enables proteomics analysis of tyrosine signaling in embryonic stem cells. Anal Chem. 2009;81:3440–3447. doi: 10.1021/ac802720e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Askenazi M, Parikh JR, Marto JA. mzAPI: a new strategy for efficiently sharing mass spectrometry data. Nat Methods. 2009;6:240–241. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0409-240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schindelin J, et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jaqaman K, et al. Robust single-particle tracking in live-cell time-lapse sequences. Nat Methods. 2008;5:695–702. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gibson DG, et al. Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nat Methods. 2009;6:343–345. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.