Abstract

Background

Significant disruption in caregiving is associated with both increased internalizing symptoms, most notably during childhood heightened separation anxiety symptoms, and altered functional development of the amygdala, a neurobiological correlate of anxious behavior. However, much less is known about how functional alterations of amygdala predict individual differences in anxiety. Here, we probed amygdala function following institutional caregiving using very subtle social-affective stimuli (trustworthy and untrustworthy faces), which typically result in large differences in amygdala signal, and change in separation anxiety behaviors over a two-year period. We hypothesized that the degree of differentiation of amygdala signal to trustworthy versus untrustworthy face stimuli would predict separation anxiety symptoms.

Methods

Seventy-four youths (mean (SD) age=9.7 years (2.64) with and without previous institutional care, who were all living in families at the time of testing, participated in an fMRI task designed to examine differential amygdala response to trustworthy versus untrustworthy faces. Parents reported on their children’s separation anxiety symptoms at the time of scan and again two years later.

Results

Previous institutional care was associated with diminished amygdala signal differences and behavioral differences to the contrast of untrustworthy and trustworthy faces. Diminished differentiation of these stimuli types predicted more severe separation anxiety symptoms two years later. Older age at adoption was associated with diminished differentiation of amygdala responses.

Conclusions

A history of institutional care is associated with reduced differential amygdala responses to social-affective cues of trustworthiness that are typically exhibited by comparison samples. Individual differences in the degree of amygdala differential responding to theses cues predict the severity of separation anxiety symptoms over a two-year period. These findings provide a biological mechanism to explain the associations between early caregiving adversity and individual differences in internalizing symptomology during development, thereby contributing to individualized predictions of future clinical outcomes.

Keywords: Amygdala development, parents, stress, institutional rearing, separation anxiety, social

Introduction

Unstable caregiving early in life, a significant source of adversity for the infant, has profound effects on emotional development. For example, extreme neglect during early institutional care significantly increases the risk for internalizing problems (Humphreys, Gleason, et al., 2015; Slopen, McLaughlin, Fox, Zeanah, & Nelson, 2012; Zeanah et al., 2009), In childhood, these problems often manifest as separation anxiety symptoms (Cicchetti, Rogosch, & Toth, 1994; Wiik et al., 2011). Separation anxiety is a particular concern for youth with a history of institutional care (Elliott & McMahon, 2011; Humphreys, Lee, et al., 2015; Tottenham et al., 2011), who lack a stable caregiver during infancy. At the neural level, this extreme form of neglect is associated with alterations in amygdala function (Gee, Humphreys, et al., 2013; Maheu et al., 2010; Tottenham et al., 2011) a primary mediator of threat processes (Davis & Whalen, 2001). The amygdala, because of its rapid growth during the postnatal period (Gilmore et al., 2012) and its stress hormone receptor abundance (Avishai-Eliner, Yi, & Baram, 1996), is highly vulnerable to early adversity. These factors, combined with its associations with anxiety-related behaviors (Indovina, Robbins, Núñez-Elizalde, Dunn, & Bishop, 2011), suggest the amygdala is a prime substrate for linking the well-characterized associations between caregiving adversity and heightened anxiety.

Despite exposure to adverse caregiving, there is nonetheless significant heterogeneity in internalizing outcomes, like separation anxiety, for previously institutionalized (PI) youth, which can be better understood by examining amygdala function. Cross-sectional studies have shown individual differences in separation anxiety in PI youth are associated with amygdala circuitry (Gee, Gabard-Durnam, et al., 2013). However, longitudinal designs permit for examination of the course of emotional difficulties, which have been shown to exacerbate with increasing age in PI youth (Castle et al., 2009; Colvert et al., 2008; Wiik et al., 2011), although in some cases the quality of the post-adoptive home may buffer against some of these outcomes (Humphreys, Gleason, et al., 2015). The present study used a prospective design to assess whether amygdala function predicts increases in separation anxiety within PI youth.

Typically, the amygdala is highly sensitive to the safety/danger value of social-affective cues (Adolphs, 2010), and has been shown to be involved in the subtlest discriminations of facial cues, such as trustworthiness (Todorov & Engell, 2008), which both adults and children (Cogsdill & Banaji, 2015; Ewing, Caulfield, Read, & Rhodes, 2015) rapidly discriminate. However, for individuals with a history of adversity, this ability to reliably discriminate between cues of safety and danger can be compromised (reviewed in Christianson et al., 2012), and failure to exhibit discrimination either behaviorally or at the level of the amygdala has been associated with increased risk for internalizing psychopathology (Britton, Lissek, Grillon, Norcross, & Pine, 2011; Straube, Mentzel, & Miltner, 2005). Discrimination of the amygdala response to such cues may be predictive of anxiety outcomes for PI youth, as anxiety is associated with difficulty discriminating threat and safety cues (Lissek et al., 2009; Mohlman, Carmin, & Price, 2007), including very subtle discriminations based on trustworthiness (Meconi, Luria, & Sessa, 2014). In PI youth, amygdala function has typically been assessed by examining general reactivity to facial expressions (e.g., fear (Gee, Gabard-Durnam, et al., 2013). Although this is a powerful probe of amygdala reactivity, these imaging studies have not tested discrimination ability. Indeed, other studies have shown that PI children have little difficulty behaviorally discriminating clear exemplars of facial expressions (Jeon, Moulson, Fox, Zeanah, & Nelson, 2010; Nelson, Parker, & Guthrie, 2006); however, signal detection methods have revealed a decreased sensitivity for subtler discriminations of facial differences in PI children (Fries & Pollak, 2004; Pollak, Cicchetti, Hornung, & Reed, 2000). These findings suggest that early deprivation might interfere with discriminating between subtle socio-affective cues. Thus, the first aim of this study was to examine the ability of PI youth to discriminate between subtle social-affective cues (i.e., facial trustworthiness) both at the level of behavior and the amygdala.

We tested the hypothesis that the extent to which the amygdala exhibits a differential response to facial trustworthiness would predict age-related increases in separation anxiety. We examined separation anxiety symptoms because during childhood, internalizing problems commonly manifest as separation anxiety (Cartwright-Hatton, McNicol, & Doubleday, 2006) particularly in those who experience adverse caregiving (Cicchetti et al., 1994; Schimmenti & Bifulco, 2015) and because PI youth typically exhibit very high separation anxiety symptoms (Elliott & McMahon, 2011; Humphreys, Lee, et al., 2015; Tottenham et al., 2011). Separation anxiety has been shown to be associated with amygdala alterations (Redlich et al., 2014) and weak regulatory connections between amygdala and prefrontal cortex (Carpenter et al., 2015; Gee, Gabard-Durnam, et al., 2013), but the prospective role of amygdala function in child separation anxiety is still not well understood. Thus, we hypothesized that in contrast to youth with a typical caregiving history, on average PI youth would not exhibit differential amygdala responses to trustworthy and untrustworthy faces. However, the extent of differential amygdala response would predict the course of separation anxiety, informing a mechanistic understanding through which early caregiving adversity results in future elevations in separation anxiety.

Methods

Participants

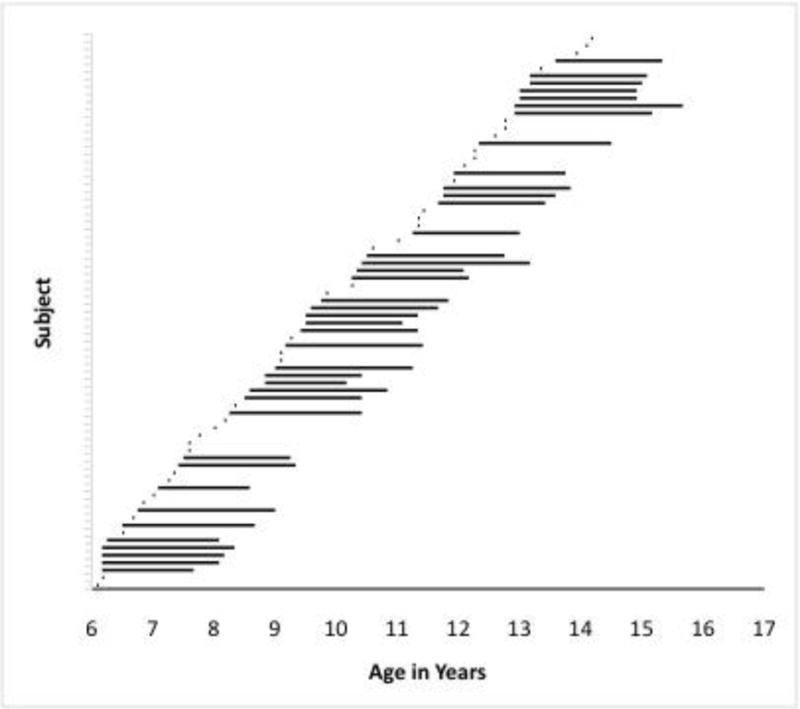

Behavioral data (81 PI, 97 comparison) were collected from youth between 6–14 years-old at Time 1, and 8–16 years-old at Time 2 (see Fig 1)m and functional MRI data were collected from a subset of these participants (39 PI, 66 comparison). Table 1 shows demographic data and group differences. PI youth had a history of institutional rearing and were adopted by families in the United States via international adoption (see online Appendix). Fifteen participants (4 PI; 11 comp) were excluded from the fMRI study due to excessive motion (>2.5 mm). Six participants (2 PI; 4 comp) were excluded due to amygdala parameter estimates more than 3 SD away the group mean, leaving a total fMRI sample of 33 PI and 41 comparison youth. Youth included in the behavioral study had reaction times of less than 1000 msec and a false alarm rate of less than 50%, as well as reaction time data within 2 SD of the mean; the final sample included 42 PI and 45 comparison youth. Youth with a history of head trauma, seizure disorder, or IQ<70 were excluded. All participants were right-handed. Families had incomes above the US median annual household income ($48,451; US Census Bureau, 2006). This study was approved by the UCLA Institutional Review Board, and informed consent and assent were obtained.

Figure 1.

Ages of participants at Time 1 and Time 2. Participants with one point had data from the first scan but no follow-up information on anxiety

Table 1.

Demographics and between-group differences

| fMRI data | Behavioral data | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| PI percentage or mean (SD) | Comparison percentage or mean (SD) | χ2(df) or t(df) | PI percentage or mean (SD) | Comparison percentage or mean (SD) | χ2(df) or t(df) | |

| Child Gender (% male) | 24.2% | 43.9% | 3.10+ (1) | 29% | 40% | 1.26 (1) |

| Age (Years) | 10.26 (2.5) | 9.43 (2.4) | 1.46 (72) | 10.6 (2.3) | 10.51 (2.7) | 0.16 (85) |

| Full-Scale IQ | 108.42 (13.9) | 114.51 (16.3) | 1.70+ (72) | 105.21 (15.7) | 110.89 (16.2) | 1.66 (85) |

| Age (Mo) at Adoption | 25.86 (20.9) | – | – | 20.43 (19.8) | – | – |

| Range | 3–84 | – | – | 2.5–84 | – | – |

| Age (Mo) Orphaned | 4.64 (8.6) | – | – | 3.99 (8.71) | – | – |

| Range | 0–36 | – | – | 0–36 | – | – |

| RCADS Separation Anxiety Time 1 (Tscore) | 49.60 (7.8) | 43.35 (7.0) | 2.65* (37) | 49.82 (11.7) | 41.59 (5.0) | 2.78** (34) |

| RCADS Separation Anxiety Time 2 (Tscore) | 50.77 (11.4) | 41.39 (5.0) | 3.35** (37) | 47.88 (9.0) | 41.94(5.2) | 2.46* (34) |

| % clinically elevated RCADS Time 1 | 0% | 0% | N/A | 12% | 0% | 2.36 (1) |

| % clinically elevated RCADS Time 2 | 15.8% | 0% | 3.42+ (1) | 6% | 0% | 1.15 (1) |

p<.10

p<.05

p<.001

Evaluation of anxiety (Time 1, Time 2)

Parents completed the Revised Children’s Anxiety and Depression Scale (Chorpita, Yim, Moffitt, Umemoto, & Francis, 2000) at Time 1 and again at Time 2 (2 years later). Parents rated 47 items describing their child’s mood and anxiety symptoms (from ‘Never’ to ‘Always’). The separation anxiety scale was used in this study, e.g., ‘My child doesn’t like to be away from his/her family,’ ‘My child gets scared if he/she sleeps away from home.’ For ease of interpretation, T scores and percent clinically elevated (T-score ≥ 65) are presented in Table 1; raw scores were used for analyses. Parents rated their own anxiety using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Spielberger, 1970; see online Appendix).

Stimuli

During fMRI, participants completed two runs of a face-processing task. Face stimuli were color images of four female faces (Lundqvist, Flykt, & Öhman, 1998). Overtly, subjects performed a facial expression identification task (i.e., identify neutral target expressions amongst a continuous sequence of neutral (target), happy, and fear faces. However, face stimuli were selected from those models whose neutral faces have been identified as highly trustworthy (TrustA) or highly untrustworthy (UntrustA) by adult samples (Oosterhof & Todorov, 2008). Thus, the stimulus set consisted of 12 unique stimuli (4 models (two TrustA and two UntrustA) × 3 expressions (neutral, happy, fear). The neutral faces were the stimuli of interest in the current study for examination of TrustA vs. UntrustA responses. Analyses did not include happy and fear since emotional expressions can override trustworthiness qualities of faces (Caulfield, Ewing, Bank, & Rhodes, 2015).

To ensure that children and adolescents could differentiate the trustworthiness of the faces similarly to adults, participants rated the trustworthiness of the faces on a 1–9 Likert scale (1=not at all, 9=extremely). For young participants, a developmentally appropriate description of trustworthiness was provided (e.g., friendly, nice, safe; Cogsdill & Banaji, 2015). A repeated-measures ANOVA showed a main effect of face type (F(1,81)=12.59, p=.001) such that all participants rated TrustA faces as being more trustworthy than UntrustA faces. There was no significant effect of Group or Age, or Group×FaceType interaction.

fMRI task

We have reported on this task in previous publications (e.g., (Gee, Gabard-Durnam, et al., 2013) with a focus on passive viewing of emotion (i.e., fear), but the effect of face type (i.e., neutral TrustA vs. neutral UntrustA) has not yet been examined. The task consisted of two counterbalanced runs: neutral in the context of fear and neutral in the context of happy (with an equal number of TrustA vs. UntrustA neutral faces in each run). Stimulus order within each run was randomized and fixed. Participants were instructed to press a button with their index finger for each neutral face as quickly as they could. Faces were presented for 500 msec. The probability of a TrustA or UntrustA face was 50% on any given trial. Stimuli were jittered (average 5000 msec inter-trial interval, 3000–9000 msec) and randomized (Wager & Nichols, 2003). Each run contained 48 trials (24 neutral target faces, 24 fearful or happy non-target faces). This task was administered both in and out of the scanner since in-scanner behavior is not always a reliable index performance. Therefore, analyses focused on the behavioral data from the out-of-scanner administration and amygdala responses from the scanning session. The out-of-scanner task was identical to the scanner task except that neutral faces were presented in the context of happy non-target faces only, and stimulus duration was 500 msec with 1000 msec intertrial intervals. Practice trials were administered prior to both administrations of the task.

General procedure

Time 1 data collection involved two sessions. In the first, behavioral measures including RCADS and the out-of-scanner face-processing task. Participants were acclimated to the scanner environment with an MRI replica. At the second session (occurring within a mean of 3.6 months (range=0–16 months, SD=3.6, 70% of subjects with data from both sessions had the second session within 4 months of the first), participants completed the fMRI face-processing task. Time 2 collection of the RCADS occurred two years later (mean=23.6 months, SD=3.4).

fMRI data acquisition

Scanning was performed on a Siemens Trio 3.0 Tesla MRI scanner, with a 12-channel radiofrequency head coil. For each participant, an initial 2D spin-echo image (TR=2000ms, TE=40ms, matrix size 256×256, 4mm thick, 0mm gap) in the oblique plane was acquired. A whole-brain high-resolution, T1*weighted anatomical scan (MPRAGE; 256 × 256 in-plane resolution, 256 mm field of view [FOV]; 192 mm × 1 mm sagittal slices) was acquired for registration and localization of functional data to Talairach space (Talairach & Tournoux, 1988). The faces task was presented on a computer screen through MR-compatible goggles during two functional scans. T2*weighted echoplanar images were collected at an oblique angle of approximately 30 degrees (130 volumes/run, TR=2000, TE=30ms, flip angle=90 degrees, matrix size 64×64, FOV=192, 34 slices, 4mm slice thickness, skip 0mm, 24 observations per event type).

Behavioral data analysis

Accuracy was calculated as total correct presses to neutral faces minus total errors (commission to happy or fear faces and omission to neutral faces) for the two face types (TrustA, UntrustA) separately. We calculated mean reaction time for correct hits to TrustA and UntrustA neutral target faces and normed within-subject to account for age differences with the calculation (TrustA −UntrustA)/(TrustA+UntrustA). Accuracy and reaction time were calculated for the task both in and out of the scanner, and tested for interactions with age and FaceType (TrustA, UntrustA). IQ and sex were tested as potential covariates but were nonsignificant so were removed from final models.

fMRI data analysis

fMRI data were preprocessed and analyzed using Analysis of Functional NeuroImages (AFNI; Cox, 1996). Preprocessing of each individual’s images included slice time correction, spatial realignment to correct for head motion, registration to the first volume of each run, spatial smoothing using a 6-mm Gaussian kernel (FWHM), and transformation into standard space (Talairach & Tournoux, 1988) using parameters obtained from each individual’s high-resolution anatomical scan. Volumes with motion greater than 2.5mm in any direction were excluded (via censoring); two participants had volumes censored (one had 15%, one .05% censored). Talairached transformed images had a resampled resolution of 3 mm3. Timeseries were normalized to percent signal change to allow for comparisons across runs and individuals. Functional runs were concatenated prior to creating two individual-level models for each participant to model activation. At the single-subject level, each participant’s individual-level model included 6 task regressors (2 FaceType × 3 expressions), accuracy, and six motion parameters. The two regressors of interest for all analyses were neutral TrustA and neutral UntrustA.

ROI analysis

The right and left anatomical amygdala, as defined by AFNI’s Talairach & Tournoux Atlas, were selected as regions of interest (ROIs). Beta weights were extracted for the right and left amygdala for each participant for the TrustA and UntrustA neutral face conditions, and were analyzed in SPSS with age, IQ, and normed reaction time tested as covariates. Only IQ was significant and thus included in the final model.

Whole brain analysis

To supplement the ROI analysis, a whole-brain analysis was conducted to examine FaceType×Group differences. At the group level, a linear mixed effect whole-brain analysis was conducted with within-subjects factor of face type and between-subjects factor of group, with age and IQ as covariates. This analysis was corrected for multiple comparisons at p<.01, using 3dClustSim, with a voxel size of 3 mm3, 2-sided, 3rd nearest neighbor, and a blur estimate (fwhm=6).

Results

Behavioral task performance (out of scanner)

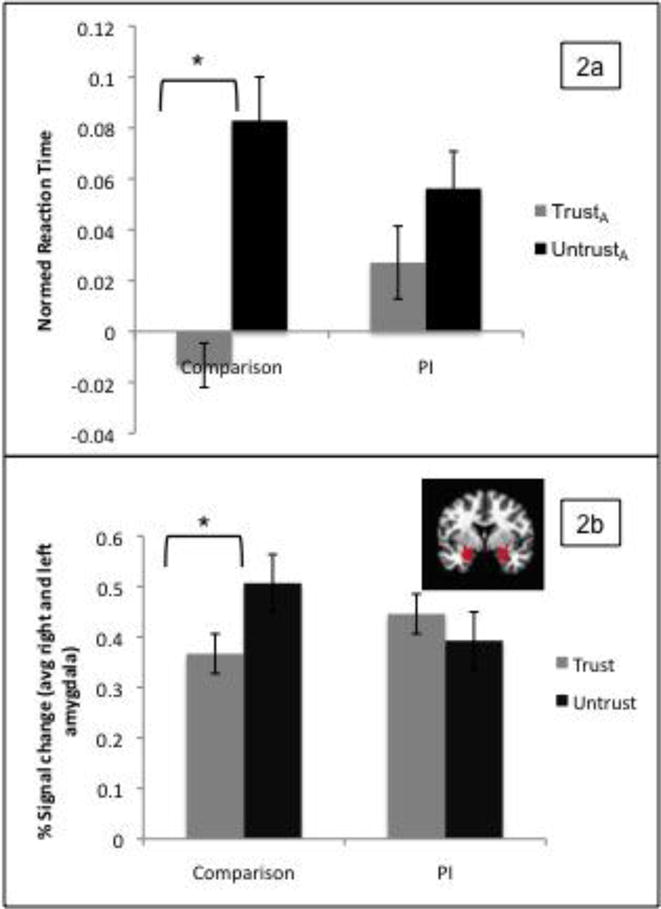

Two separate repeated measures ANOVA were performed with the within-subjects factor of FaceType (TrustA, UntrustA) and the between-subjects factor of group (PI, comparison) on the dependent measures of normed reaction time and accuracy. Age was entered as a covariate. There was a main effect of FaceType (F(1,87)=5.88, p=.017), and a significant FaceType×Group interaction (F(1,87)=4.02, p=.048). Comparison participants had differential reaction times for the UntrustA versus TrustA faces, but the PI participants did not, due to slower reaction times to the TrustA faces (Figure 2a). There were no other main effects or interactions. There was only a Group×Age interaction indicating that for the comparison group, accuracy increased with age (F(1,81)=8.48, p=.005). Accuracy was not significantly correlated with reaction time in either group.

Figure 2.

Group differences in reaction time (a) and amygdala response (b) to UntrustA versus TrustA faces

fMRI task

In-scanner behavioral data. Reaction time and accuracy data collected in the scanner were used to ensure on-task performance. Overall, subjects showed good accuracy and there were no significant Group×FaceType interactions for accuracy (F=.59, p=.44; Mean for TrustA: CompAcc=81%; PIAcc=90%, and UntrustA: CompAcc=75%; PIAcc=76%;) or reaction time (F=.17,p=.68; Mean (SD) for TrustA: CompRT=682.15 (169.17) msec ; PIRT=694.07 (196.63) msec, and UntrustA: CompRT=733.83 (205.93) msec ; PIRT=723.17 (179.0) msec).

Amygdala ROI. To examine group differences in amygdala responses, FaceType (TrustA, UntrustA)_and hemisphere (left, right) were entered as within-subject factors in a repeated-measures ANOVA, with group (PI, comparison) entered as a between-subjects factor, and IQ as a covariate. Child sex was also tested as a covariate in this and subsequent models, but was non-significant in all analyses and thus removed from final models. There was a significant FaceType×Group interaction (F(1,71)=4.04, p=.048) such that amygdala reactivity differentiated UntrustA versus TrustA faces for the comparison participants, but not for the PI participants (Figure 2b). This was due to the PI participants having increased amygdala response to the TrustA faces. There were no other significant main effects or interactions.

Whole brain analysis. AFNI’s 3dttest++ revealed significant FaceType×Group interactions in the left fusiform gyrus and right inferior parietal lobule (see online supplemental Table S2 and Supplemental Figure 1). Post-hoc examination showed that the PI group showed greater differentiation of UntrustA and TrustA faces, although the strength of these differentiations was not significantly associated with reaction time, adoption age, or trust ratings (ps>.05).

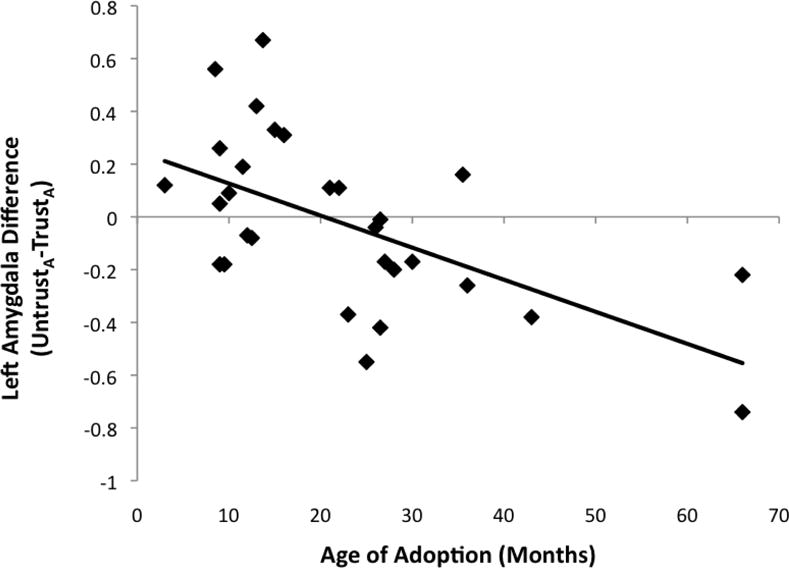

Age of adoption and amygdala response

To examine age of adoption associations, an UntrustA−TrustA difference score (hereafter referred to as DifferenceA) for beta weights was calculated so that a greater score indicated greater discrimination. Three youth placed in institutions after 24 months were excluded from this analysis because for this analysis, age of institutionalization serves as a proxy of ‘dose’ of institutional care, and children placed at later ages were outliers placed much later than other participants. A partial correlation (controlling for age) showed that left amygdala DifferenceA was significantly correlated with age of adoption (r(27)=−.76, p<.001), with youth adopted at early ages having greater DifferenceA (Figure 3). There was a similar trend for the right amygdala (r(27)=−.35, p=.06). There was no significant correlation between DifferenceA and time with adopted family (left amygdala: r(30)=.24, p=.21; right amygdala: r(30)=.10, p=.61), or between age of adoption and reaction time difference scores (r(35)=.10, p=.53).

Figure 3.

Association between age of adoption and amygdala difference score (UntrustA versus TrustA faces)

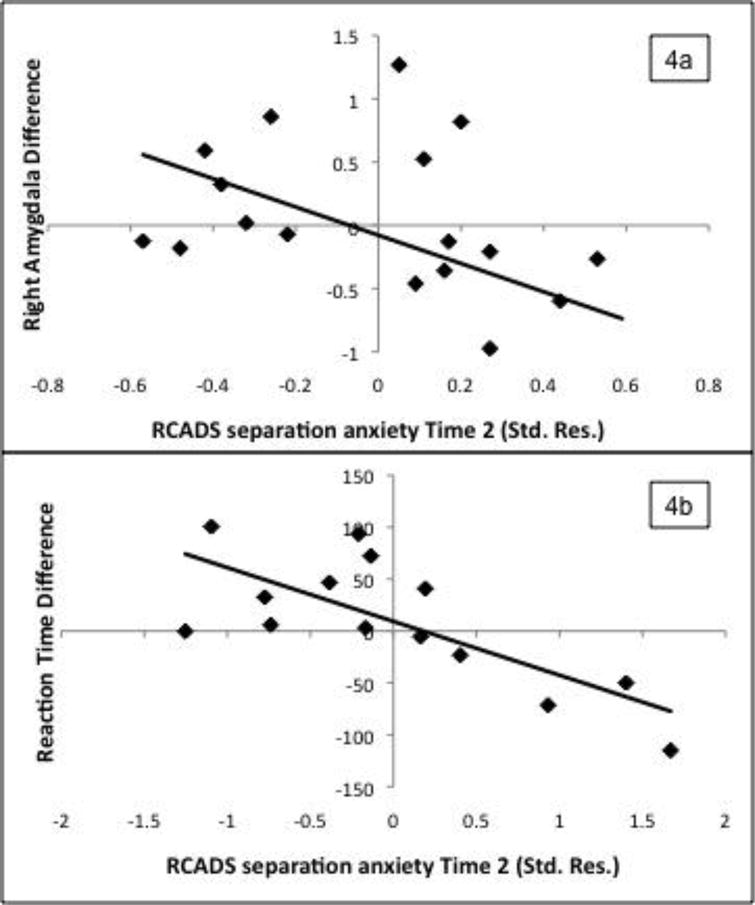

Prediction of Time 2 separation anxiety

To test prospective associations between amygdala response and separation anxiety (SAD), a hierarchical regression was performed with Time 2 SAD score as the dependent variable and with Time 1 SAD score, child age at Time 1, IQ, Group (PI or comparison), DifferenceA, and a Group×DifferenceA interaction term entered as predictors (see Table 2) for those participants with follow-up data (19 PI, 20 comparison). Parent anxiety was initially tested as a covariate but was insignificant so removed from the final model. There were no significant differences in Time 1 SAD for participants who did versus did not return for follow-up. Right and left DifferenceA scores were highly correlated in both the comparison and PI groups (r=.92 and .73, respectively, p<.001). To prevent collinearity problems, only right DifferenceA was entered into the regression (results from a separate regression including the left amygdala are provided in Table 2). Time 1 SAD significantly predicted Time 2 SAD. There was a Group×DifferenceA interaction indicating that in the PI group only, differential amygdala responses predicted Time 2 SAD over and above Time 1 SAD, such that youth with less discrimination between UntrustA−TrustA had greater increases over the two years in SAD (Figure 4a). Functionally-defined ROIs from the whole brain analysis (fusiform gyrus and inferior parietal lobule) did not significantly predict SAD.

Table 2.

Regression predicting change in separation anxiety from amygdala discrimination (DifferenceA; UntrustA−TrustA)

| (a) Left Amygdala | (b) Right Amygdala | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| ßa | ΔR2 | ßa | ΔR2 | ||

| Step 1: SAD Time 1 | .37* | .41*** | .33* | .41*** | |

| Step 2: Demographics | .04 | .04 | |||

| Time 1 age | −.05 | −.05 | |||

| IQ | −.23 | −.25+ | |||

| Step 3: Group | .37* | .07* | .43** | .07* | |

| Step 4: DifferenceA | .25+ | .01 | .25+ | .00 | |

| Step 5: Group×DifferenceA | −.32* | .07* | −.40** | .10** | |

Standardized Betas in the final model.

p<.10

p < .05

p < .01

p<.001.

Figure 4.

Relationship between right amygdala (a) and reaction time (b) difference scores (UntrustA−TrustA) with Time 2 separation anxiety (standardized residual after removing variance due to Time 1 separation anxiety, age, and IQ) in the PI group

A similar regression was conducted with normed reaction time difference score (DifferenceRT) predicting Time 2 SAD after controlling for Time 1 SAD, age, and IQ (n=17 PI; 19 comparison). In both groups, youth with lower DifferenceRT (indicating more similar reaction times to each face type) had greater increases in SAD (see Figure 4b and Table 3). The Group×DifferenceRT interaction term was not significant.

Table 3.

Regression predicting change in separation anxiety from reaction time discrimination (DifferenceRT; UntrustA−TrustA)

| ßa | ΔR2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Step 1: SAD Time 1 | .44** | .29** |

| Step 2: Demographics | .04 | |

| Time 1 age | −.22 | |

| IQ | −.02 | |

| Step 4: Group | .001 | .01 |

| Step 3: DifferenceRT | −.44* | .22*** |

| Step 5: Group×DifferenceRT | −.09 | .003 |

Standardized Betas in the final model.

p<.10

p < .05.

p < .01

Discussion

This study examined differential amygdala responses to social-affective cues (i.e., trustworthiness) as a predictor of future separation anxiety in PI youth. We focused on amygdala function because of its demonstrated atypical development in PI populations (e.g., Tottenham et al., 2011), its role in discriminating trustworthiness (Todorov & Engell, 2008), and in separation anxiety (Redlich et al., 2014). While comparison youth exhibited differential amygdala responses to untrustworthy versus trustworthy faces (similar to adult samples (Oosterhof & Todorov, 2008), on average PI youth exhibited similar amygdala responses to both face types. This lack of discrimination was associated with older age at adoption. Behavioral data were consistent, showing that PI youth did not differentiate in reaction times. This lack of differentiation was striking given that both groups verbally indicated a difference in trustworthiness. Thus, while PI youth are able explicitly identify social-affective cues, they may be less likely to discriminate in terms of their rapid behavioral and amygdala responses (e.g., Olsavsky et al., 2013). Taken together, these findings suggest that the nature of affect confusion following early adversity derives from an implicit level, and may be due to amygdala over-reactivity rather than an explicit misunderstanding of the difference between two stimuli.

Discrimination of social-affective cues like trustworthiness may be a useful index of the extent of amygdala alterations following early life adversity and predictive of future amygdala-related mental health difficulties such as separation anxiety. Discrimination of the right amygdala response and reaction times to trustworthiness predicted increases in future (but not current) separation anxiety symptoms for PI youth, consistent with other findings that internalizing problems of PI youth may exacerbate as they enter adolescence (e.g., Colvert et al., 2008). The current findings provide a possible mechanism for the association between early caregiving adversity and later emergence of internalizing problems.

Across several species, the amygdala seems particularly sensitive to early life caregiving adversity (reviewed in Tottenham & Sheridan, 2010). However, findings on amygdala structure have been mixed, with amygdala volume exhibiting atypically larger or smaller volumes (Hanson et al., 2015; Mehta et al., 2009; Tottenham et al., 2010), or no differences (Sheridan, Fox, Zeanah, McLaughlin, & Nelson, 2012) in PI youth. The findings from functional MRI studies are more consistent, evidencing amygdala hyperreactivity (Gee, Humphreys, et al., 2013; Maheu et al., 2010) associated with affective dysregulation (Gee, Gabard-Durnam, et al., 2013; Tottenham et al., 2011), a significant risk factor for anxiety (Redlich et al., 2014; Stein, Simmons, Feinstein, & Paulus, 2007). Results of this study advance this line of inquiry by showing that early caregiving adversity interferes with discriminating subtle face differences and underlying amygdala function.

These discriminations were predictive of future separation anxiety, underscoring their importance as a marker of amygdala alteration. Lack of discrimination appeared to be due to a greater avoidance-type reaction (i.e. slowed reaction time, greater amygdala response) to trustworthy faces in the PI group, which could indicate hypervigilance and difficulty determining safety. It is also important to consider the potentially adaptive nature of indiscriminate social appraisals in PI youth (Chisholm, 1998). Future work may show that this framework is useful for understanding other atypical caregiver relationship patterns in PI youth beyond separation anxiety, including indiscriminate friendliness and/or disorganized attachment (e.g., Bos et al., 2011; Gleason et al., 2014).

A whole-brain analysis showed that the PI group had greater differential responses in higher-level face processing cortical areas, unlike in the amygdala, possibly reflecting a greater reliance on top-down face processing to differentiate the faces explicitly. Notably, these brain areas did not relate to age of adoption, anxiety, reaction time, or verbal trustworthiness ratings, suggesting that amygdala function is more directly linked with early adversity and likely to be a better predictor of future separation anxiety.

Study limitations include lack of information on specific pre-adoption adverse events (e.g., prenatal factors, multiple placements). However, the associations with age of adoption suggest that atypical discrimination is influenced by institutional care. The PI group differs on many levels from the comparison group, thus future studies should compare institutionalization with other forms of adversity. Additionally, the trustworthiness judgments in this study were implicit; possibly, PI children were less ‘tuned in’ to the trustworthiness aspect of the faces, perhaps because the overt task demanded more cognitive resources. However, this still suggests that PI youth have difficulty with implicit social-affective judgments, which is likely to affect their mental health outcomes (as shown here by their increases in separation anxiety). While the PI group showed less differentiated reaction time out of the scanner, both groups had similar differentiations of in-scanner reaction time. It is difficult to generalize in-scanner behavior as the scanner environment is highly novel, but further research is needed to understand reaction time differences in these two environments. Laterality of effects might have been under-powered (i.e., most effects showed similar trends in both hemispheres), and therefore conclusions about laterality should be tempered until further research is performed. Finally, our measure of separation anxiety is based on parent report, and should be considered a continuous measure of anxiety rather than a diagnostic measure.

Taken together, results of this study demonstrate that PI youth show reduced affective discrimination, both on a behavioral and neural level. Reduced discrimination was related to later age of adoption and also increases in separation anxiety over time. At the same time, these results are consistent in suggesting that some children, especially those adopted at earlier ages, show resiliency in internalizing problems. These results suggest a possible mechanism for increases in mental health difficulties often seen in youth with histories of early adversity, as well as a marker and predictor of variability and potential resiliency. While functional imaging is unlikely to be used for diagnostic purposes in the near future, these data can inform individualized predictors of the development of anxiety (e.g., lack of affective discrimination, social difficulties), which can be used to target early intervention and prevention of future clinical problems.

Supplementary Material

Appendix S1. Supplementary methods.

Table S1. Country of origin for PI group.

Table S2. MNI coordinates for areas of significant between-group differences in response to UntrustA versus TrustA faces (FaceType×Group interaction).

Figure S1. Significant clusters for whole-brain FaceType×Group interaction. Blue indicates regions where the PI group had greater UntrustA versus TrustA discrimination (PI>Comp; UntrustA >TrustA).

Key points.

-

-

Early caregiving adversity is associated with increased anxiety symptoms and atypical amygdala function, which contributes to differentiating threat from safety in socio-affective cues.

-

-

Although caregiving adversity increases the risk for separation anxiety, many children show resilience, but the mechanisms of these individual differences are not well-understood.

-

-

This study examined amygdala function by focusing on discrimination of social-affective cues and tested the hypothesis that the degree to which the amygdala displays a typical differential response to social-affective cues will predict future increases in separation anxiety for previously institutionalized (PI) youth.

-

-

For PI youth, the extent of differential amygdala response to social-affective cues longitudinally predicted future separation anxiety symptoms (across 2 years). Degree of amygdala differential response correlated with age of adoption.

-

-

These results suggest a possible mechanism for future increases in internalizing problems often seen in youth with histories of early adversity. We discuss these results in terms of individualized early intervention and prevention for this group of youth at risk for internalizing problems.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by R01MH091864 (National Institute of Mental Health), the Dana Foundation, and Postdoctoral NRSA 1 F32MH105167-01.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

The authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Adolphs R. What does the amygdala contribute to social cognition? Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2010;1191(1):42–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05445.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avishai-Eliner S, Yi SJ, Baram TZ. Developmental profile of messenger RNA for the corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor in the rat limbic system. Developmental Brain Research. 1996;91(2):159–163. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(95)00158-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos K, Zeanah CH, Fox NA, Drury SS, McLaughlin KA, Nelson CA. Psychiatric Outcomes in Young Children with a History of Institutionalization. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 2011;19(1):15–24. doi: 10.3109/10673229.2011.549773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton JC, Lissek S, Grillon C, Norcross MA, Pine DS. Development of anxiety: the role of threat appraisal and fear learning. Depression and Anxiety. 2011;28(1):5–17. doi: 10.1002/da.20733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter KH, Angold A, Chen NK, Copeland WE, Gaur P, Pelphrey K, Egger HL. Preschool Anxiety Disorders Predict Different Patterns of Amygdala-Prefrontal Connectivity at School-Age. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(1):e0116854. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright-Hatton S, McNicol K, Doubleday E. Anxiety in a neglected population: Prevalence of anxiety disorders in pre-adolescent children. Clinical Psychology Review. 2006;26(7):817–833. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castle J, Groothues C, Colvert E, Hawkins A, Kreppner J, Sonuga-Barke E, Rutter M. Parents’ Evaluation of Adoption Success: A Follow-Up Study of Intercountry and Domestic Adoptions. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2009;79(4):522–531. doi: 10.1037/a0017262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caulfield F, Ewing L, Bank S, Rhodes G. Judging trustworthiness from faces: Emotion cues modulate trustworthiness judgments in young children. British Journal of Psychology. 2015 doi: 10.1111/bjop.12156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm K. A Three Year Follow-up of Attachment and Indiscriminate Friendliness in Children Adopted from Romanian Orphanages. Child Development. 1998;69(4):1092–1106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Yim L, Moffitt C, Umemoto LA, Francis SE. Assessment of symptoms of DSM-IV anxiety and depression in children: a revised child anxiety and depression scale. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2000;38(8):835–855. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00130-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christianson JP, Fernando ABP, Kazama AM, Jovanovic T, Ostroff LE, Sangha S. Inhibition of Fear by Learned Safety Signals: A Mini-Symposium Review. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2012;32(41):14118–14124. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3340-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA, Toth SL. A Developmental Psychopathology Perspective on Depression in Children and Adolescents. In: Reynolds WM, Johnston HF, editors. Handbook of Depression in Children and Adolescents. Springer US; 1994. pp. 123–141. [Google Scholar]

- Cogsdill EJ, Banaji MR. Face-trait inferences show robust child–adult agreement: Evidence from three types of faces. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2015;60 [Google Scholar]

- Colvert E, Rutter M, Beckett C, Castle J, Groothues C, Hawkins A, Sonuga-Barke EJS. Emotional difficulties in early adolescence following severe early deprivation: Findings from the English and Romanian adoptees study. Development and Psychopathology. 2008;20(02):547–567. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox RW. AFNI: Software for Analysis and Visualization of Functional Magnetic Resonance Neuroimages. Computers and Biomedical Research. 1996;29(3):162–173. doi: 10.1006/cbmr.1996.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M, Whalen PJ. The amygdala: vigilance and emotion. Molecular Psychiatry. 2001;6(1):13–34. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott A, McMahon C. Anxiety Among an Australian Sample of Young Girls Adopted From China. Adoption Quarterly. 2011;14(3):161–180. [Google Scholar]

- Ewing L, Caulfield F, Read A, Rhodes G. Perceived trustworthiness of faces drives trust behaviour in children. Developmental Science. 2015;18(2):327–334. doi: 10.1111/desc.12218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fries ABW, Pollak SD. Emotion understanding in postinstitutionalized Eastern European children. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;(02):355–369. doi: 10.1017/S0954579404044554. null. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee DG, Gabard-Durnam LJ, Flannery J, Goff B, Humphreys KL, Telzer EH, Tottenham N. Early developmental emergence of human amygdala–prefrontal connectivity after maternal deprivation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2013;110(39):15638–15643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307893110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee DG, Humphreys KL, Flannery J, Goff B, Telzer EH, Shapiro M, Tottenham N. A Developmental Shift from Positive to Negative Connectivity in Human Amygdala–Prefrontal Circuitry. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2013;33(10):4584–4593. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3446-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore JH, Shi F, Woolson SL, Knickmeyer RC, Short SJ, Lin W, Shen D. Longitudinal Development of Cortical and Subcortical Gray Matter from Birth to 2 Years. Cerebral Cortex. 2012;22(11):2478–2485. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleason MM, Fox NA, Drury SS, Smyke AT, Nelson CA, Zeanah CH. Indiscriminate Behaviors in Previously Institutionalized Young Children. Pediatrics. 2014;133(3) doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson JL, Nacewicz BM, Sutterer MJ, Cayo AA, Schaefer SM, Rudolph KD, Davidson RJ. Behavioral Problems After Early Life Stress: Contributions of the Hippocampus and Amygdala. Biological Psychiatry. 2015;77(4):314–323. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys KL, Gleason MM, Drury SS, Miron D, Nelson CA, 3rd, Fox NA, Zeanah CH. Effects of institutional rearing and foster care on psychopathology at age 12 years in Romania: follow-up of an open, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(7):625–634. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00095-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys KL, Lee SS, Telzer EH, Gabard-Durnam LJ, Goff B, Flannery J, Tottenham N. Exploration—exploitation strategy is dependent on early experience. Developmental Psychobiology. 2015;57(3):313–321. doi: 10.1002/dev.21293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indovina I, Robbins TW, Núñez-Elizalde AO, Dunn BD, Bishop SJ. Fear-Conditioning Mechanisms Associated with Trait Vulnerability to Anxiety in Humans. Neuron. 2011;69(3):563–571. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon H, Moulson MC, Fox N, Zeanah C, Nelson CA. The Effects of Early Institutionalization on the Discrimination of Facial Expressions of Emotion in Young Children. Infancy. 2010;15(2):209–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7078.2009.00007.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lissek S, Rabin SJ, McDowell DJ, Dvir S, Bradford DE, Geraci M, Grillon C. Impaired discriminative fear-conditioning resulting from elevated fear responding to learned safety cues among individuals with panic disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2009;47(2):111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundqvist D, Flykt A, Öhman A. Hospital DoNK. Stockholm: 1998. The Karolinska Directed Emotional Faces (KDEF) [Google Scholar]

- Maheu F, Dozier M, Guyer A, Mandell D, Peloso E, Poeth K, Ernst M. A preliminary study of medial temporal lobe function in youths with a history of caregiver deprivation and emotional neglect. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience. 2010;10(1):34–49. doi: 10.3758/CABN.10.1.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meconi F, Luria R, Sessa P. Individual differences in anxiety predict neural measures of visual working memory for untrustworthy faces. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2014:nst189. doi: 10.1093/scan/nst189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta MA, Golembo NI, Nosarti C, Colvert E, Mota A, Williams SCR, Sonuga-Barke EJS. Amygdala, hippocampal and corpus callosum size following severe early institutional deprivation: The English and Romanian Adoptees Study Pilot. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50(8):943–951. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohlman J, Carmin CN, Price RB. Jumping to interpretations: Social anxiety disorder and the identification of emotional facial expressions. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45(3):591–599. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CA, Parker SW, Guthrie D. The discrimination of facial expressions by typically developing infants and toddlers and those experiencing early institutional care. Infant Behavior and Development. 2006;29(2):210–219. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsavsky AK, Telzer EH, Shapiro M, Humphreys KL, Flannery J, Goff B, Tottenham N. Indiscriminate Amygdala Response to Mothers and Strangers After Early Maternal Deprivation. Biological Psychiatry. 2013;74(11):853–860. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oosterhof NN, Todorov A. The functional basis of face evaluation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2008;105(32):11087–11092. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805664105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak SD, Cicchetti D, Hornung K, Reed A. Recognizing emotion in faces: Developmental effects of child abuse and neglect. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36(5):679–688. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.36.5.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redlich R, Grotegerd D, Opel N, Kaufmann C, Zwitserlood P, Kugel H, Dannlowski U. Are you gonna leave me? Separation Anxiety is associated with increased amygdala responsiveness and volume. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2014:nsu055. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsu055. http://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsu055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Schimmenti A, Bifulco A. Toward a Better Understanding of the Relationship between Childhood Trauma and Psychiatric Disorders: Measurement and Impact on Addictive Behaviors. Psychiatry Investigation. 2015;12(3):415–416. doi: 10.4306/pi.2015.12.3.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan MA, Fox NA, Zeanah CH, McLaughlin KA, Nelson CA. Variation in neural development as a result of exposure to institutionalization early in childhood. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109(32):12927–12932. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200041109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slopen N, McLaughlin K, Fox N, Zeanah C, Nelson C. ALterations in neural processing and psychopathology in children raised in institutions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012;69(10):1022–1030. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger C. Manual for the State-trait anxiety inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, MD, MPH Murray, Simmons, PD Alan, Feinstein, BS Justin, Paulus, MD Martin. Increased Amygdala and Insula Activation During Emotion Processing in Anxiety-Prone Subjects. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164(2):318–327. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.2.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straube T, Mentzel HJ, Miltner WHR. Common and Distinct Brain Activation to Threat and Safety Signals in Social Phobia. Neuropsychobiology. 2005;52(3):163–168. doi: 10.1159/000087987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talairach J, Tournoux P. Co-planar stereotaxic atlas of the human brain: 3-dimensional proportional system: an approach to cerebral imaging. Thieme; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Todorov A, Engell AD. The role of the amygdala in implicit evaluation of emotionally neutral faces. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2008:nsn033. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsn033. http://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsn033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Tottenham N, Hare TA, Millner A, Gilhooly T, Zevin JD, Casey BJ. Elevated amygdala response to faces following early deprivation. Developmental Science. 2011;14(2):190–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2010.00971.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tottenham N, Hare TA, Quinn BT, McCarry TW, Nurse M, Gilhooly T, Casey BJ. Prolonged institutional rearing is associated with atypically large amygdala volume and difficulties in emotion regulation. Developmental Science. 2010;13(1):46–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2009.00852.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wager T, Nichols T. Optimization of experimental design in fMRI: a general framework using a genetic algorithm. Neuroimage. 2003;18:293–309. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(02)00046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiik KL, Loman MM, Van Ryzin MJ, Armstrong JM, Essex MJ, Pollak SD, Gunnar MR. Behavioral and emotional symptoms of post-institutionalized children in middle childhood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2011;52(1):56–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02294.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeanah CH, Egger HL, Smyke AT, Nelson CA, Fox NA, Marshall PJ, Guthrie D. Institutional Rearing and Psychiatric Disorders in Romanian Preschool Children. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166(7):777–785. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08091438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1. Supplementary methods.

Table S1. Country of origin for PI group.

Table S2. MNI coordinates for areas of significant between-group differences in response to UntrustA versus TrustA faces (FaceType×Group interaction).

Figure S1. Significant clusters for whole-brain FaceType×Group interaction. Blue indicates regions where the PI group had greater UntrustA versus TrustA discrimination (PI>Comp; UntrustA >TrustA).