Abstract

We report a detailed study for a point mutation of the crucial binding site residue, D128, in the biotin-streptavidin complex. The conservative substitution, D128N, preserves the detailed structure observed for the wild type complex but has only minimal impact on biotin binding, even though previous experimental and computational studies suggested that a charged D128 residues was crucial for high-affinity binding. These results show clearly that the fundamental basis for streptavidin’s extremely strong biotin binding affinity is more complex than assumed, and illustrate some of the challenges that may arise when analyzing extremely strong ligand-protein binding interactions.

Graphical Abstract

We have long used the biotin-streptavidin complex as a model system to study the molecular origins of high-affinity ligand binding to a protein target, because this complex is quite amenable to detailed structural and thermodynamic measurements and can be manipulated easily to generate a variety of interesting mutants that impact ligand binding, often in rather subtle ways.1,2,8,9 In this current study, we have generated a point mutation for a crucial streptavidin binding site residue, D128, and characterized the mutant’s three-dimensional structure and ligand binding. We have shown previously with detailed structural, thermodynamic, and computational studies that D128 does indeed play an essential role in the high-affinity binding of biotin.2 The conservative substitution we have introduced, D128N, does not perturb equilibrium structure. Our crystallographic results show that N128 effectively substitutes for D128 to accept a hydrogen bond from the biotin ureido N-H, and all other biotin-streptavidin interactions are perfectly preserved as well, when compared to the wild-type complex.3 However, we were quite surprised to discover that this mutation has minimal impact on biotin binding affinity. We have shown previously that the extensive hydrogen bonding network present in the biotin binding pocket is highly cooperative and makes a major contribution to the exceptionally strong biotin binding interaction4–6, and earlier computational studies for streptavidin suggested that an ionized aspartate residue at position 128 plays a crucial role in polarizing this hydrogen bonding network.7,8 However, our preliminary biotin binding assays reveal that the mutation has only a small impact on binding affinity, far less than we had anticipated, based on the presumed crucial contributions that a charged D128 residue makes in the complex. Molecular dynamics simulations also reveal no observable destabilization of any protein-ligand interactions, consistent with the crystallographic results. These combined structural, biophysical and computational studies suggest that an ionized D128 residue is not crucial for high-affinity biotin binding, and that we need to reconsider the exact nature and origin of the cooperative hydrogen bonding contributions to biotin binding affinity. These results also raise a cautionary note for analysis of ligand binding reactions: the detailed explanation for high-affinity ligand binding may be more complicated than initial experimental and computational studies might suggest.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

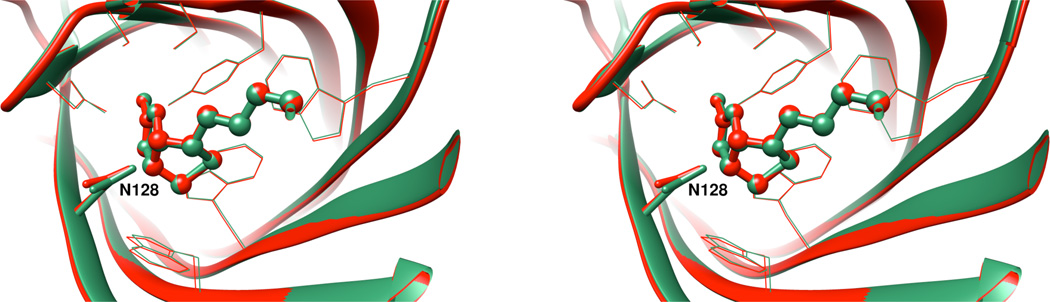

Diffraction data and refinement statistics for the crystal structure of the D128N mutant (PDB identification code 4yvb), complexed with biotin, are given in Table S1 in the Supporting Information. The binding pocket structure for the D128N mutant and the wild type complex (PDB identification code 3ry2) are nearly identical (Figure 1), and indeed the entire structures are strikingly similar, except for some conformational variation at the immediate amino and carboxy termini.

Figure 1.

Stereoplot of the biotin binding site for wild-type streptavidin (PDB code 3ry2) in green and the D128N mutant (PDB code 4yvb) in red. Biotin is rendered as a ball-and-stick image, D128/N128 is shown as a tube and other binding site residues are displayed in wireframe for perspective.

The D128N mutation does not alter the equilibrium positions of the atoms interacting with biotin from their positions observed in the wild type protein (Figures 2A and 2B). When the wild type and mutant structures are superposed on the basis of the biotin ligand, the positions of side chain atoms in the first shell of residues around the biotin are virtually identical for the wild type and mutant complexes. The hydrogen bond between the side chain of residue 128 and N1 of biotin is unchanged. The interatomic distances for the mutant and wild type structures do not differ significantly (D128N OD1-N1 = 2.87 Å (A chain), 2.88 Å (B chain), 2.85 Å (C chain) and 2.84 Å (D chain); wild type OD2-N1 = 2.81 (A chain) and 2.82 Å (B chain)).

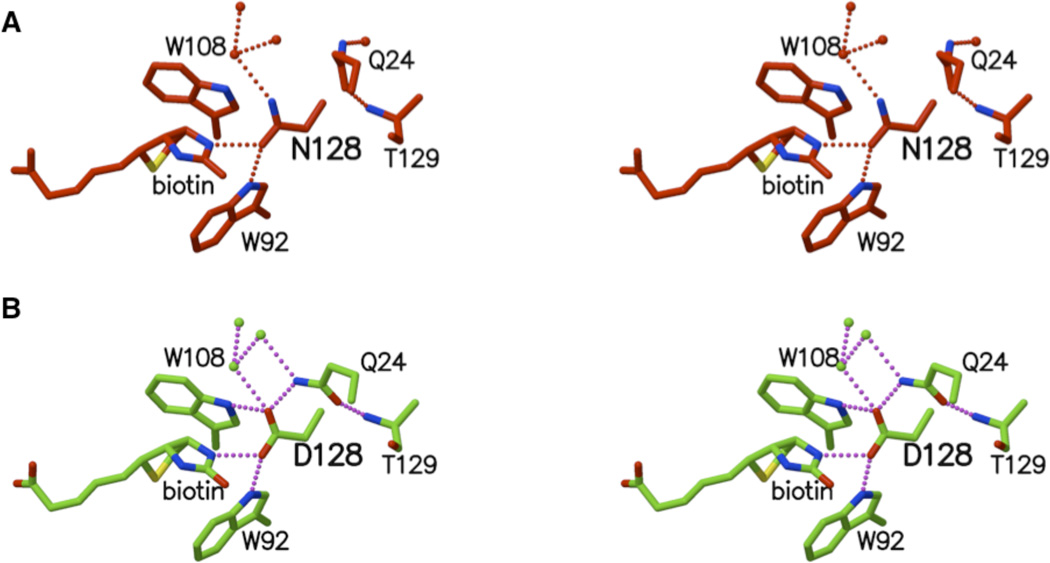

Figure 2.

Stereoplots of (A) D128N mutant and (B) wild type binding sites. Hydrogen bonding interactions with donor-acceptor distances less than 3.0 Å shown as dashed lines and water molecules are displayed as small spheres.

Although the D128N mutation does not alter the first shell residue interactions with biotin, it does cause a change in the structure of the water network bound to the protein, as well as the side chain conformation of Q24 (Figures 2A and 2B). Replacing a carboxylate oxygen with an NH2 group increase the volume occupied by the N128 side chain and changes the pattern of hydrogen bond donor and acceptor atoms involved in protein-protein and protein-water interactions. The two additional hydrogen atoms crowd the neighboring water molecule and the amino group of the Q24 side chain, resulting in a rotation of the Q24 side chain away from N128. This opens the space near the N128 side chain and is associated with binding of a water molecule in a position different from that in the wild type complex.

Atom OE1 of Q24 interacts with the backbone amide of T129, and this interaction is retained in both the mutant and wild type structures. Accordingly, the motion of the Q24 side chain is not simply rotation about one of the three χ angles. Instead, χ1 changes by −9°, χ2 by −16°, and χ3 by +74°. This combination of bond rotations leaves the backbone atoms as well as the OE1 side chain atom positioned exactly as they are in the wild type structure. The differences between the wild type and D128N structures are thus limited primarily to the water molecules in the immediate proximity of residue Q24 (Figure 2).

We performed a 500 nanosecond molecular dynamics simulation to probe the impact of the D128N point mutation on biotin binding site structure and protein-ligand interactions. Our simulation yields an average structure that is nearly identical to the crystal structure. The backbone RMSD fluctuation for all core residues (all residues except those in the three large surface loops) relative to the crystal structure over the final 400 nanoseconds of simulation is ~0.7 Å, and all core residue side chain positions are maintained relative to the crystal structure. All protein-biotin hydrogen bonds are also well maintained and the side chain amide carbonyl oxygen of N128 effectively “substitutes” for the D128 side chain carbonyl oxygen as a hydrogen bond acceptor. The biotin N-H hydrogen bond with the N128 side chain superimposes almost perfectly onto the corresponding biotin-D128 hydrogen bond in the wild-type structure.

We do observe markedly increased mobility for the Q24 side chain that yields a time-averaged structure in which the Q24 backbone positions are preserved relative to the wild-type structure, but the side chain generally adopts conformations that displace it from N128, consistent with the crystal structure results. Otherwise, there are no significant structural variations in the D128N mutant relative to our earlier simulation results for wild-type protein.

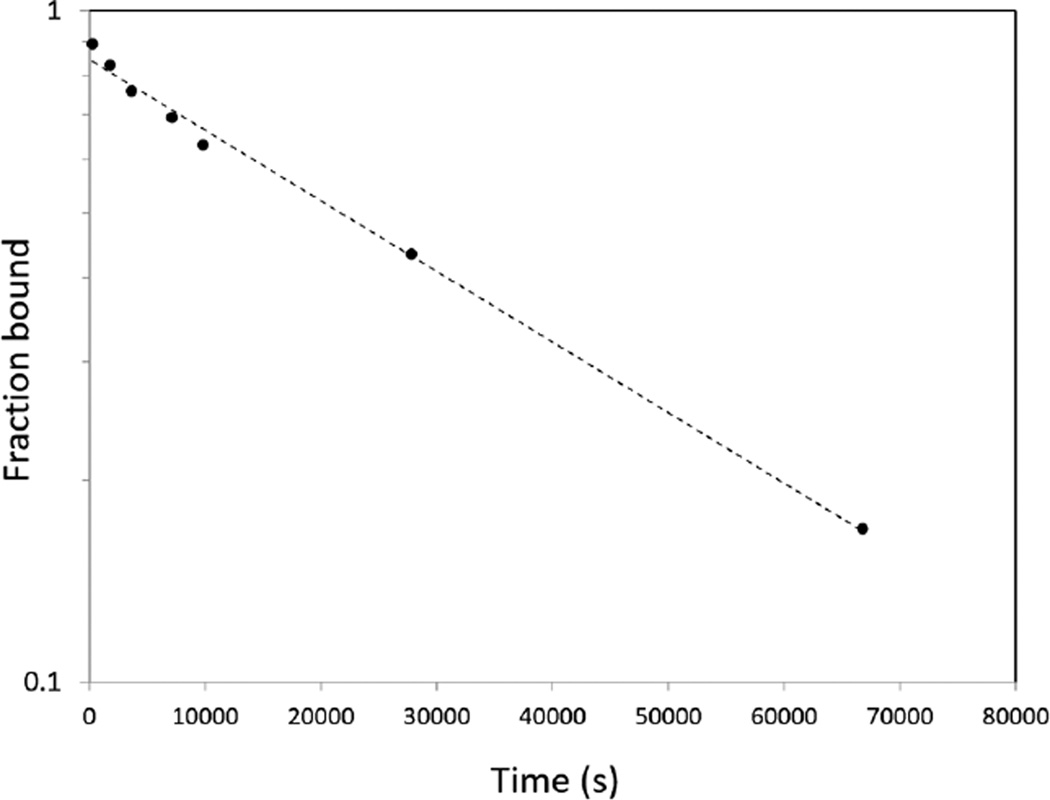

We used a cold-chase radiometric method described previously4 to measure the biotin dissociation rate koff from the D128N mutant. We have observed nearly perfect correlation between biotin koff and the equilibrium constant for biotin-streptavidin complex formation in all previous studies of conservative point mutants that retain wild-type structure, as shown in Figure S1 in Supporting Information. Since koff is an excellent indicator for equilibrium biotin binding affinity, we use this measurement routinely for initial biotin binding assessment. The koff (25°C) for D128N, 2.42×10−5 s−1 (Figure 3), is only 6.3-fold faster than that for wild-type streptavidin at 25°C (3.85×10−6 s−1), indicating that the D128N mutation causes only minimal loss in binding affinity versus wild-type (<10-fold reduction in Ka).

Figure 3.

Plot of 3H-biotin release from the D128N streptavidin complex as a function of time in competition binding assay with excess (50 µM) unlabeled biotin.

Both the crystallographic data and the equilibrium molecular dynamics simulation results suggest that the D128N mutant should bind biotin approximately as well as wild-type streptavidin, so in some sense, the biophysical data obtained in this study are not surprising. However, our results challenge existing hypotheses to explain the basis of biotin’s extremely tight binding. These current results clearly suggest that the extremely strong biotin binding interaction observed for the streptavidin complex does not require an ionized aspartate residue at position 128. We know from our previous experimental studies that a highly cooperative hydrogen bonding network in the ligand binding pocket makes a major contribution to biotin binding affinity in WT streptavidin3–5, and we have shown that D128 has a significant impact on biotin binding thermodynamics.2 As discussed above, earlier computational studies for model streptavidin binding site systems suggested that an ionized aspartate residue played a major role in creating this highly cooperative hydrogen bonding network7, 8, but our current experimental results indicate that this is not the case.

It is logical to ask why there is such dramatic disagreement between the earlier computational studies and our current experimental results, and a related project currently underway in our laboratory suggests a likely explanation. We are presently using detailed QM/MM calculations to better understand how various mutations to second-shell residues (I.e., residues that are immediately adjacent to binding site residues) impact biotin binding energetics in cases where the mutations introduce no detectable structural perturbations, as documented by high-resolution crystal structures for each streptavidin mutant.9, 10 Our preliminary results indicate that we can reasonably reproduce binding free energy changes as a function of second-shell residue mutations only when we include the entire streptavidin protein environment in the molecular mechanics zone of the QM/MM calculations. The molecular mechanics zone exerts a significant influence on the quantum mechanical zone, which encompasses the complete biotin binding site, due to the electric field generated by partial charges assigned to the atoms in the molecular mechanics zone. If we attempt to use reduced-site models for the QM/MM calculations that include only binding site residues or even a larger subset of residues from a streptavidin monomer, we cannot even reproduce the qualitative trends observed for biotin binding thermodynamics for wild-type versus second-shell streptavidin mutants.

Our current results suggest that the origin of hydrogen bonding cooperativity in the biotin-streptavidin system is more complex than we had assumed, and it is clear that more extensive study is needed to better understand the detailed molecular basis for the strong streptavidin-biotin binding interaction. Our results also suggest that caution should be exercised when utilizing simplified model systems to investigate detailed energetics of ligand-protein complexes in general, as simplified models may inadvertently omit important contributions of the full protein.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM080214 (T.P.L.).

We thank Richard To for help with mutagenesis. Use of the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Contract No. DE-AC02-76SF00515. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences (including P41GM103393). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIGMS or NIH.

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: ??????

One figure, one table, and experimental methods (PDF)

REFERENCES

- 1.Stayton PS, Freitag S, Klumb LA, Chilkoti A, Chu V, Penzotti JE, To R, Hyre D, ILeTrong I, Lybrand TP, Stenkamp RE. Biomol. Eng. 1999;16:39–44. doi: 10.1016/s1050-3862(99)00042-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freitag S, Chu V, Penzotti J, Klumb L, To R, Hyre D, Le Trong I, Lybrand TP, Stenkamp RE, Stayton PS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1999;96:8384–8389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Le Trong I, Wang Z, Hyre DE, Lybrand TP, Stayton PS, Stenkamp RE. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2011;67:813–821. doi: 10.1107/S0907444911027806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klumb L, Chu V, Stayton PS. Biochemistry. 1998;37:7657–7663. doi: 10.1021/bi9803123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Le Trong I, Freitag S, Klumb L, Chu V, Stayton PS, Stenkamp RE. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2003;59:1567–1573. doi: 10.1107/s0907444903014562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hyre D, Le Trong I, Merritt E, Eccleston J, Green N, Stenkamp RE, Stayton PS. Protein Sci. 2006;15:459–467. doi: 10.1110/ps.051970306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeChancie J, Houk K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:5419–5429. doi: 10.1021/ja066950n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tong Y, Mei Y, Li Y, Ji C, Zhang J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:5137–5142. doi: 10.1021/ja909575j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baugh L, Le Trong I, Cerutti DS, Gülich S, Stayton PS, Stenkamp RE, Lybrand TP. Biochemistry. 2010;49:4568–4570. doi: 10.1021/bi1005392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baugh L, Le Trong I, Cerutti DS, Mehta N, Gülich S, Stayton PS, Stenkamp RE, Lybrand TP. Biochemistry. 2012;51:597–607. doi: 10.1021/bi201221j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.