Abstract

Purpose

This study was aimed to develop a novel Histidine-Leucine-Lopinavir (His-Leu-LPV) dipeptide prodrug and evaluate its potential for circumvention of P-gp and MRP2-mediated efflux of lopinavir (LPV) indicated for HIV-1 infection.

Methods

His-Leu-LPV was synthesized following esterification of hydroxyl group of LPV and was identified by 1H-NMR and LCMS/MS techniques. Aqueous solubility, stability and cell cytotoxicity of prodrug was determined. Uptake and permeability studies were carried out using P-gp (MDCK-MDR1) and MRP2 (MDCK-MRP2) transfected cell lines. To further delineate prodrug uptake, prodrug interaction with influx transporters (PepT1 and PHT1) was determined. Enzymatic hydrolysis and reconversion of His-Leu-LPV to LPV was examined using Caco-2 cell homogenates.

Results

Aqueous solubility generated by the prodrug was markedly higher relative to unmodified LPV. Importantly, His-Leu-LPV displayed significantly lower affinity towards P-gp and MRP2 as evident from higher uptake and transport rates. [3H]-GlySar and [3H]-L-His uptake receded to approximately 30% in the presence of His-Leu-LPV supporting the PepT1/PHT1 mediated uptake process. A steady regeneration of LPV and Leu-LPV in Caco-2 cell homogenates indicated His-Leu-LPV undergoes both esterase and peptidase-mediated hydrolysis.

Conclusion

Histidine based dipeptide prodrug approach can be an alternative strategy to improve LPV absorption across poorly permeable intestinal barrier.

Keywords: uptake, transport, protease inhibitor, HIV-1, P-gp, MRP2, PHT1, PepT1

Graphical Abstract

1. INTRODUCTION

Lopinavir (LPV) is currently indicated in highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in combination with ritonavir (Hughes et al., 2011). Despite potent efficacy against HIV-1, oral administration results in poor intestinal absorption and negligible LPV levels in the body. One of the major factors that potentially limit intestinal absorption is the high substrate affinity of LPV towards P-gp and MRP2 (Kis et al., 2010). P-gp and MRP2 are extensively expressed on the villus tip of enterocytes, the primary absorption site for orally administered drugs (Christians, 2004). These efflux pumps, on its way of limiting the entry of other harmful substances and xenobiotics, prevents LPV from getting transported across the intestinal epithelium thus secreting it back into the intestinal lumen. Hence, to overcome these efflux pumps, a significantly higher dose of LPV needs to be administered. Although high doses of LPV has made it possible to achieve therapeutic plasma concentrations, at the same time it has resulted in severe cellular and/or systemic toxicities (Cvetkovic and Goa, 2003).

Combination strategies capable of modulating the expression and functional activity of efflux pumps present a unique approach to improve absorption and efficacy of LPV. However, such strategies may pose a risk of generating serious systemic adverse events (Chandwani and Shuter, 2008; Senise et al., 2011). For instance, Bertrand et al. reported an excessive increase in vincristine neuropathy when administered along with cyclosporine to modulate MDR (Bertrand et al., 1992). Similarly, Kerr et al. demonstrated an unassuming pharmacokinetic interaction between verapamil (efflux pump inhibitor) and doxorubicin in humans. Although, oral verapamil was being able increase the AUC, terminal t1/2 and volume of distribution of verapamil, the plasma drug clearance significantly dropped due to inhibition of efflux pumps leading to various side effects (Kerr et al., 1986). In the past few decades, prodrug based approaches have garnered considerable interest to improve pharmacokinetic as well as pharmacological profiles of poorly permeable therapeutic agents (Mandal et al., 2015; Rautio et al., 2008). Interestingly, prodrugs have been designed such that various endogenous transporters, co-expressed with efflux pumps, are targeted to improve drug absorption. In this regard, peptide transporters have been extensively utilized in our laboratory to improve cellular permeability of various antiviral agents such as saquinavir (Wang et al., 2012), lopinavir (Agarwal et al., 2008), acyclovir (Talluri et al., 2009) and ganciclovir (Kansara et al., 2007). The peptide prodrug conjugates may extend an additional advantage of generating non-toxic nutrient byproducts at the target site where prodrugs are getting converted to the parent drug and pro-moieties. The binding of a target agent to an influx transporter confers a structural change to the transporter leading to the translocation of molecule across membrane and thus its subsequent release into the cytoplasm. Moreover, suitable combinations of amino acids in dipeptide prodrugs, can modulate physicochemical properties of the parent drug.

Recently, brain and intestinal expression of a peptide/histidine transporter (PHT1, SLC15A4) has been reported (Bhardwaj et al., 2006; Herrera-Ruiz et al., 2001; Hu et al., 2014; Zwarycz and Wong, 2013). Such unique expression renders PHT1 a potential target to improve delivery of P-gp and MRP2 substrates such as LPV. Exploiting the role of peptide/histidine transporter in transporting various P-gp and MRP2 substrates still remain to be discussed in detail. Considering previous results all together, these findings led to the development of histidine based dipeptide prodrug. Here we disclose a study where, the histidine based dipeptide prodrug, His-Leu-LPV, has been synthesized and evaluated. The presence of histidine as a terminal targeting moiety is hypothesized to improve recognition of the prodrug by PHT1 (Mahato et al., 2011). Furthermore, His-Leu-LPV being a dipeptide prodrug is also anticipated to be transported by peptide transporters (PepT1 and PepT2). Such dual recognition of His-Leu-LPV might significantly improve absorption of His-Leu-LPV across poorly permeable membranes. Nevertheless, the physicochemical properties and affinity of His-Leu-LPV towards major drug efflux pumps have been first investigated in the present study. Aqueous solubility and buffer stability of His-Leu-LPV at various pH values have been examined. Uptake and transport studies have been carried out in Madin-Darby canine kidney cells type II (MDCKII) cell lines overexpressing P-gp (MDCKII-MDR1) and MRP2 (MDCKII-MRP2) to determine the affinity of His-Leu-LPV towards these efflux transporters.

2. EXPERIMENTAL

2.1 Materials

Unlabeled LPV and P-gp inhibitor, GF120918 were generous gift from Abbott Laboratories Inc. (North Chicago, IL, USA). [3H]-LPV (0.5 Ci/mmol), [3H]-glycylsarcosine (3H-GlySar) (29.4 Ci/mmol) and [3H]-Histidine (3H-His) (47.7 Ci/mmol) were purchased from Moravek Biochemicals (Brea, CA, USA). Streptomycin, penicillin, HEPES (4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid), triton X-100, D-glucose, sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3), MK571, Boc-histidine, Boc-leucine, ethyl acetate, dichloromethane (DCM), dicyclohexylcarbodimide (DCC), 4-(N,N-dimethylamino)pyridine (DMAP), glucose, sodium chloride (NaCl), potassium chloride (KCl), calcium chloride (CaCl2), sodium phosphate (Na2 HPO4), potassium phosphate (KH2PO4), magnesium sulfate (MgSO4) and Amberlyst® A21 resin were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). HPLC grade methanol and DMSO were purchased from Fisher Scientific Co. (Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Trypsin-EDTA solution, Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was obtained from Atlanta Biologics (Lawrenceville, GA, USA). Premium siliconized microcentrifuge tubes were procured from MIDSCI (St. Louis, MO, USA). Uptake plates and Transwell® inserts were obtained from Corning Costar Corp. (Cambridge, MA, USA). All other chemicals were of analytical reagent grade procured from Thermo Fischer Scientific or Sigma Aldrich and were utilized without any further purification.

2.1.1. Synthesis of His-Leu-LPV

2.1.1.1. Synthesis

His-Leu-LPV was synthesized according to a protocol previously published from our laboratory with minor modifications (Agarwal et al., 2008). His-Leu-LPV synthesis included two steps (a) coupling of leucine to LPV through an ester bond to produce Leu-LPV (b) coupling of histidine to Leu-LPV intermediate via an amide bond to generate His-Leu-LPV. Leu-LPV was synthesized using a procedure published from our laboratory. To synthesize His-Leu-LPV, commercially available Boc-His-OH (341mg, 1.35mmol) and DCC (420 mg, 2.025 mmol) were dissolved in DCM (6 mL) in a round bottom flask. The mixture was stirred for 1h at 0°C in an ice bath (mixture 1). In a separate round bottom flask, Leu-LPV (500 mg, 0.067mmol) was dissolved in DCM and triethylamine (2 mL) was added to the resulting solution (mixture 2). Mixture 2 was stirred for 30 min at room temperature (RT) under nitrogen atmosphere and added dropwise to the mixture 1. The reaction mixture was stirred for 24h at RT while monitoring every 6h with TLC and LCMS/MS. The reaction mixture was filtered and DCM was evaporated at RT under reduced pressure to obtain crude product. The product Boc-His-Leu-LPV was purified using silica column chromatography with 5% methanol/dichloromethane (MeOH/DCM) as an eluent.

2.1.1.2. Deprotection of the N-Boc group

Boc-His-Leu-LPV was dissolved in 60% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in DCM and stirred at 0°C for 1h in order to remove the N-Boc protecting group. The mixture was evaporated to obtain a solid form of TFA salt of His-Leu-LPV. The TFA salt was further dissolved in anhydrous DCM and mixed with Amberlyst® A21 resin (weakly basic resin) for 15–30 min. The mixture was filtered and quickly evaporated under reduced pressure and the final product was obtained following recrystallization in cold diethyl ether. The final product was stored in −20°C until any further use. Reaction scheme for synthesis of Leu-LPV and His-Leu-LPV has been depicted in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

(A) Synthesis of Leu-LPV: (i) Boc-Leucine, DCC in DCM: 1h at 0°C; LPV, DMAP in DCM: 15min at RT and mixture stirred for 48h at RT. (ii) 60% TFA in DCM: 1 h at 0°C (B) Synthesis of His-Leu-LPV : (i) Boc-Histidine-Leucine, DCC in DCM: 1h at 0°C; LPV, DMAP in DCM: 15min at RT and mixture stirred for 48h at RT. (ii) 60% TFA in DCM: 1 h at 0°C

2.1.2. Identification of the prodrugs

Leu-LPV and His-Leu-LPV were characterized by 1 H-NMR analysis. Spectra was recorded on Varian Mercury 400 Plus spectrometer using tetra methyl silane. Chemical shifts (δ) are reported in parts per million relative to the NMR solvent signal (CD3OD, 3.31ppm for proton and 49.15ppm for carbon NMR spectra). Mass analysis was carried out using LCMS/MS spectrometer with electron-spray ionization (ESI) as an ion source in positive mode.

Leu-LPV: Low melting point solid; LC/MS (m/z): 742.6; 1 H NMR (400 MHz, chloroform-d) δ ppm 0.78 (br. s., 3 H) 0.93 (br. s., 5 H) 1.22 (br. s., 5 H) 1.95 (br. s., 2 H) 2.09 (d, J=10.54 Hz, 4 H) 2.57 – 2.75 (m, 12 H) 2.80 (br. s., 2 H) 3.17 (br. s., 1 H) 3.31 (br. s., 1 H) 4.05 (d, J=12.10 Hz, 1 H) 4.17 (d, J=15.23 Hz, 1 H) 4.26 – 4.70 (m, 7 H) 4.81 (br. s., 1 H) 5.01 – 5.14 (m, 1 H) 6.93 (d, J=10.54 Hz, 2 H) 7.04 – 7.30 (m, 7 H).

His-Leu-LPV: Low melting point solid; LC/M S (m/z): 879.7; 1H NMR (400 MHz, chloroform-d) δ ppm 0.65 – 0.96 (m, 5 H) 1.06 – 1.40 (m, 11 H) 1.51 – 1.61 (m, 2 H) 1.70 (br. s., 2 H) 1.77 – 1.95 (m, 3 H) 2.12 (s, 2 H) 2.56 – 2.76 (m, 21 H) 3.12 – 3.28 (m, 8 H) 4.82 (br. s., 11 H) 6.71 (d, J=7.03 Hz, 3 H) 7.15 – 7.29 (m, 3 H) 8.18 (d, J=6.25 Hz, 3 H).

2.2 METHODS

2.2.1 Cell culture

Human P-gp/MDR1 cDNA transfected MDCKII cells (MDCKII-MDR1; passages 5–25) and human MRP2 cells (MDCKII-MRP2; passages 5–25), wild-type MDCKII cells (MDCK WT; passages 50–53) were generously provided by Drs. A. Schinkel and P. Borst (Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). Human derived colon carcinoma cells (Caco-2; passages 20–30) were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA). All these cell lines were cultured in T75 flasks in DMEM containing high glucose and glutamine concentrations. The culture medium contained 10% FBS (heat-inactivated), 1% nonessential amino acids, 100 IU/ml streptomycin and 100 IU/ml penicillin. The pH of the medium was maintained at 7.4. Cells were maintained at 37°C in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2 and 90% relative humidity. The medium was replaced every alternate day until cells reached 80–90% confluency (5–7 days for MDCKII and 19–21 days for Caco-2 cells).

2.2.2. Solubility studies in distilled deionized water (DDI)

Aqueous solubility studies of LPV, Leu-LPV and His-Leu-LPV was performed according to a previously published protocol from our laboratory (Agarwal et al., 2008). Briefly, saturated solutions of LPV, Leu-LPV and His-Leu-LPV were freshly prepared in DDI in siliconized tubes and placed in a shaker bath for 24h at RT. At the end of 24h, tubes were centrifuged for 10min at 10,000 rpm to separate the undissolved drug. Supernatants were carefully separated and filtered through 0.45 µm membrane filter (Nalgene syringe filter). Samples were further diluted appropriately and analyzed by HPLC.

2.2.3. Buffer stability studies

The extent of chemical hydrolysis of Leu-LPV and His-Leu-LPV was assessed according to a previously published protocol from our laboratory (Luo et al., 2011). Degradation rate constants (k × 10−4) and half-life (t1/2) values were determined at pH 4, 5.5 and 7.4. Leu-LPV (50 µM) and His-Leu-LPV (50 µM) were dissolved in 1.5 mL DPBS in siliconized tubes and placed in a shaker bath maintained at 60 rpm at 37°C. Aliquots (100µL) were withdrawn at predetermined time points for 24hr and stored at −80°C until further analysis by HPLC. Prodrug concentrations were plotted against time to determine degradation rate constants at different pH values.

2.2.4. Cytotoxicity studies

Cytotoxicity of LPV, Leu-LPV and His-Leu-LPV was determined in MDCKII-WT cells (passage 52) with MTS based cytotoxicity assay kit (Promega Co., Madison, WI). Briefly, cells were seeded in 96 well tissue culture plates at a density of 20,000 cells per well and maintained overnight at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 90% relative humidity. The medium was aspirated following day and replaced with 100 µL of serum free medium containing various concentrations of LPV, Leu-LPV and His-Leu-LPV (6.25–200 µM). After 4hr incubation at 37°C, 20 µL of MTS stock solution was added to each well. Cells were kept for incubation for 4h at 37°C. Cell viability was assessed by measuring absorbance at 485 nm with a microplate reader (BioRad Hercules, CA, USA).

2.2.5. Uptake studies

For cellular uptake studies, cells were seeded at a density of 3 × 106 cells in 12 well culture plates and maintained until they achieved 80–90% confluency (6–7 days). The uptake assay was carried out according to previously published protocol from our laboratory (Patel et al., 2012). Briefly, medium was aspirated and cell monolayers were washed three times with 2 mL of DPBS (pH 7.4) at 37°C (each wash of 10 min). Studies were initiated by incubating cells with radioactive solutions in DPBS at 37°C for 30min. Following incubations, radioactive solutions were immediately aspirated and plates were washed with ice-cold stop solution to arrest the uptake process. Lysis buffer (1mL, 0.1% Triton-X solution in 0.3% NaOH) was added to each well and plates were stored overnight at RT. Following day, 500 µL solution from each well were transferred to scintillation vials containing 3 mL of scintillation cocktail and assayed with a scintillation counter (Beckman Instruments Inc., Model LS-6500; Fullerton, CA, USA). The uptake rate was normalized to protein count, which was further quantified using a BioRad protein estimation kit (BioRad protein; Hercules, CA). For studies involving efflux inhibitors, cells were pre-incubated with 2µM GF 120918 (MDCK-MDR1) or 75µM MK 571 (MDCK-MRP2) at 37°C for 30 min prior to imitation of uptake studies.

2.2.6. Transport studies

Transepithelial transport studies were performed according to protocol published previously from our laboratory with minor modifications (Luo et al., 2011). Briefly, Transwell® inserts (0.4 µm pore size, 12 mm) were coated with type 1 rat tail collagen (100 µg/cm2) and placed inside a vessel under ammonia vapor for 45 min to promote binding of collagen to the polyester membrane. Cells were seeded at a density of 250,000 cells per insert. Following confluency, medium was removed and cell monolayers were washed three times with DPBS at 37 °C (each wash of 10 min). Cell monolayer integrity was evaluated by measuring transepithelial electric resistance (TEER) using EVOM (epithelial volt ohmmeter from World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL, USA), prior to initiation of transport studies. Cell monolayers exhibiting TEER values >250 Ω*cm2 were utilized for the transport studies. For A–B (absorptive direction) permeability studies, 0.5 mL of test solution (25 µM) was added to the apical membrane of 12-well Transwell® plates. At predetermined time points, 100 µL sample from basolateral chamber of each well was withdrawn and replaced with fresh DPBS in order to maintain sink conditions. Studies were carried out for a period of 3 h at 37°C. Samples were stored at −80 °C until further analysis using LCMS/MS. For studies involving efflux inhibitors, cells were pre-incubated with 2µM GF 120918 (MDCK-MDR1) or 75µM MK 571 (MDCK-MRP2) at 37°C for 30 min prior to initiation of transport studies.

2.2.7. Caco-2 cell homogenate studies

Cell homogenate studies were carried out according to protocol previously published from our laboratory. Briefly, confluent Caco-2 cells (passage 25) were washed three times with DPBS. Then cells were collected with a mechanical scrapper in two volumes of DPBS. Multipro variable speed homogenizer (DREMEL, Racine, WI) was used for cell homogenization. The homogenate was centrifuged at 12,500 rpm for 10min. The supernatant was collected and protein content was assessed using BioRad protein estimation kit. Suitable dilutions were made in DPBS (pH 7.4) to achieve a final protein concentration of 0.5 mg/mL. Aliquot (1 mL) of cell homogenate was incubated with His-Leu-LPV at 37°C in a shaker bath (60 rpm) to achieve a final concentration of 40 ug/mL. At predetermined time points, 100 µL samples were collected and equal volumes of ice-cold acetonitrile:methanol (5:4) mixture was added to terminate enzymatic hydrolysis. Studies were carried out at pH 7.4 for a period of 4 h. Samples were then stored at −80 °C until further analysis by LCMS/MS.

3. Sample and data analysis

3.1. Sample preparation for HPLC analysis

Aqueous solubility and buffer stability studies were analyzed by a HPLC technique. Briefly, samples were freshly prepared in DDI or buffer with pH 4, 5.5 and 7.4 in siliconized tubes and placed in a shaker bath maintained at 60rpm for 24 h at 37°C. Tubes were centrifuged for 10 min at 10,000 rpm. The supernatants were carefully separated and filtered through 0.45µm membrane filter (Nalgene syringe filter). Further appropriate dilutions of the filtrate were made in acetonitrile (50%) and water (50%) containing 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid. Samples (20µL) were injected into HPLC for analysis.

3.2. HPLC analysis

Reverse phase HPLC was employed to analyze aqueous solubility and buffer stability samples. The system comprised of Waters 515 pump (Waters, Milford, MA, USA) with a C (18) Kinetex column (100 mm × 4.6 mm, 2.6 m; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA) and a UV detector (Absorbance Detector Model UV-C, RAININ, Dynamax, Palo Alto, CA, USA, wavelength 210 nm). Acetonitrile:water (1:1) with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid was selected as a mobile phase with 0.4 mL/min as flow rate. LPV, Leu-LPV and His-Leu-LPV eluted approximately at 13.62, 8.14 and 6.79 min respectively.

3.3. Sample preparation for LCMS/MS analysis

Transport and cell homogenate samples were analyzed utilizing a sensitive LCMS/MS technique according to a method previously published by our laboratory (Agarwal et al., 2008). Briefly, samples were subjected to liquid-liquid extraction with water saturated ethyl acetate (10% water) as extracting solvent. About 50 µL of amprenavir (2.5µM) was employed as internal standard (I.S.). Samples were extracted with 800 µL water saturated ethyl acetate by vigorously vortexing for 2.5 min. Samples were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 7min and aliquots (600µL) were collected and dried under reduced pressure for 45 min. Samples were reconstituted in 100 µL of acetonitrile (70%) and water (30%) containing 0.1% formic acid. The reconstituted samples (20µL) were injected into LCMS/MS for analysis.

3.4. LCMS/MS analysis

QTrap® 3200 LCMS/MS mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) connected to Agilent 1100 Series quaternary pump (Agilent G1311A), vacuum degasser (Agilent G1379A) and autosampler (Agilent G1367A, Agilent Technology Inc. Palo Alto, CA, USA) was employed for sample analysis. Acetonitrile (70%) and water (30%) containing 0.1% formic acid was used as mobile phase at 0.3 mL/min. XTerra1MS C18 column (50 mm × 4.6 mm, 5.0 mm, Waters, Milford, MA, USA) was employed for analyte separation. Chromatograms were obtained over 5 min. LPV and amprenavir eluted at 3.05 and 2.28 min respectively. Leu–LPV and His-Leu-LPV eluted at 1.60 and 1.18 min respectively.

Positive mode of electro spray ionization was employed and analytes of interest were detected in multiple-reaction monitoring (MRM) mode. Precursor and product ions generated for LPV and amprenavir were +629.30/155.10 and +506.20/245.20 respectively. Precursor/product ions for Leu-LPV and His-Leu-LPV were obtained at +742.30/155.10 and +879.40/155.10 respectively. Turbo ion spray setting and collision gas pressure were also optimized (IS Voltage: 5500V, temperature: 500 °C, nebulizer gas: 60 psi, curtain gas: 60 psi). Other ion source parameters employed were declustering potential 66V, collision energy 60V, entrance potential 8V, and collision cell exit potential 4V. The peak areas for all components were integrated automatically using Analyst™ software. The lower limits of quantification were found to be 5 ng/mL for LPV and 15 ng/ml for Leu-LPV and His-Leu-LPV.

3.5. Permeability analysis

Cumulative amounts of LPV, Leu-LPV and His-Leu-LPV generated during transport were plotted against time. Linear regression of the amount transported as a function of time generated the rate of transport (dM/dt). Ratio of transport rate to the cross sectional area (A) further yielded the steady state flux as shown in Eq. (1).

| Eq. (1) |

Transepithelial permeabilities were calculated by normalizing the steady state flux to the donor concentration (Cd) of the drug or prodrugs as shown in Eq. (2).

| Eq. (2) |

3.6. Statistical analysis

All experiments including uptake, transport, buffer and enzymatic stability were conducted at least in triplicate and results were expressed as mean ± S.D. Student t-test was employed to determine statistical significance among groups. A value of p ≤ 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

4. Results

4.1. Solubility studies in distilled deionized water

Aqueous solubility values of Leu-LPV and His-Leu-LPV were found to be 600 ± 42 and 481 ± 82 µg/mL relative to 49 ± 3 µg/mL for LPV. The solubilities of Leu-LPV and His-Leu-LPV were respectively 12 and 9.8 times higher relative to LPV.

4.2. Buffer stability studies

Chemical hydrolysis of Leu-LPV and His-Leu-LPV was determined in DPBS adjusted to varied pH values i.e., 4, 5.5 and 7.4. Degradation rate constants and half-lives of prodrugs at pH 4, 5.5 and 7.4 values are reported in Table 1. Degradation half-lives exhibited by Leu-LPV and His-Leu-LPV at pH 4 were approximately 1.9 and 8.7 fold higher relative to pH 7.4.

Table 1.

Leu-LPV and His-Leu-LPV degradation rate constants and half-lives at various pH values.

| Prodrug | pH 4 | pH 5.5 | pH 7.4 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k × 10−4 (min) |

t1/2 (h) | k × 10−4 (min) |

t1/2 (h) | k × 10−4 (min) |

t1/2 (h) | |

| Leu-LPV | 3.90±0.06 | 29.6±0.4 | 5.78±0.09 | 20.0±0.3 | 7.53±0.14 | 15.4±0.3 |

| His-Leu-LPV | 2.92±0.03 | 39.6±0.5 | 6.21±0.15 | 18.6±0.5 | 25.5±2.4 | 4.6±0.5 |

4.3. Cytotoxicity studies

Cytotoxicity profiles of LPV, Leu-LPV and His-Leu-LPV were assessed in MDCK-WT cells using MTT assay, prior to initiation of uptake and transport studies. Serum free medium was employed to avoid interference of proteins with MTT reagents. Medium containing no test compounds and 0.1% Triton-X were selected as a negative and positive control, respectively. Medium containing 2% and 10% methanol was also examined for cytotoxic effects. As depicted in Fig. 2, medium containing 2% methanol did not exhibit any cytotoxicity effects while medium with 10% methanol showed significant cytotoxicity. Triton-X resulted in about 70% decrease in absorbance compared to negative control. LPV produced no cytotoxic effects in the range of 5–50 µM however, was cytotoxic at 100 and 200 µM. Approximately 13 and 36% reduction in number of viable cells were observed at 100 and 200 µM LPV concentration. Similarly, the prodrugs (Leu-LPV and His-Leu-LPV) were non-toxic in the concentration range of 5–50 µM. Both prodrugs generated significant cytotoxicity at much higher concentrations. Leu-LPV and His-Leu-LPV reduced cell viability by 37% and 33% at 200 µM concentrations.

Fig. 2.

Cellular cytotoxicity studies of LPV, Leu-LPV and His-Leu-LPV in MDCK-WT cells after incubation for 4h. The standard deviation for each data point was averaged over eight samples (n=8). **P<0.05 compared with the control group.

4.4. Cellular uptake studies

To study the interaction of LPV with P-gp and MRP2, [3H]-LPV uptake was carried out in MDCK-MDR1 and MDCK-MRP2 cells in presence of efflux inhibtors. As depicted in Figs. 3 A and B, approximately 4.5 and 2.9-fold rise in LPV uptake was observed in the presence of GF 120918 (2µM) and MK-571(75 µM).

Fig. 3.

Cellular uptake studies of [3H]-LPV (A) in absence and presence of GF 120918 (2 µM) in MDCK-MDR1 cells and (B) in absence and presence of MK 571 (75 µM) in MDCK-MRP2 cells. The standard deviation for each data point was averaged over four samples (n=4). **P<0.05 compared with the control group.

To further confirm the extent of interaction and affinity of LPV, Leu-LPV and His-Leu-LPV with P-gp and MRP-2, concentration dependent uptake studies were performed in MDCK-MDR1 and MDCK-MRP2 cells. Uptake of [3H]-LPV (0.5 µCi/mmol) was carried out in presence of increasing concentrations of unlabelled LPV, Leu-LPV and His-Leu-LPV. [3H]-LPV uptake dramatically elevated with rise in unlabelled LPV concentrations in both MDCK-MDR1 and MDCK-MRP2 cell lines. However, [3H]-LPV uptake remained unaltered with increasing Leu-LPV and His-Leu-LPV concentrations (Figs. 4 A, B and C).

Fig. 4.

Cellular uptake studies of [3H]-LPV in presence of increasing concentrations of (A) cold LPV, (B) cold Leu-LPV and (C) cold His-Leu-LPV in MDCK-MDR1 and MDCK-MRP2 cells. The standard deviation for each data point was averaged over four samples (n=4). **P<0.05 compared with the control group.

4.5. Transepithelial transport studies

Transpeithelial studies of LPV, Leu-LPV and His-Leu-LPV were carried out in absorptive direction (A–B) in MDCK-MDR1 and MDCK-MRP2 cells. Results obtained from these studies are presented in Fig. 5. A–B permeability rate of LPV drastically elevated in both MDCK-MDR1 and MDCK-MRP2 cell lines in the presence of efflux inhibitors. A–B permeability rates generated by LPV in the presence of GF120918 and MK571 were 3.4 ± 0.3 × 10−6 cm/s and 3.1 ± 0.2 × 10−6 cm/s, respectively. Leu-LPV generated A–B permeability rates of 3.5 ± 0.4 × 10−6 cm/s and 3.3 ± 0.7 × 10−6 cm/s, a 2.3 and 2.2-fold increase. A–B permeability rates displayed by His-Leu-LPV in MDCK-MDR1 and MDCK-MRP2 were 6.72 ± 0.67 × 10−6 cm/s and 6.10 ± 0.45 × 10−6 cm/s. Approximately 4.3 and 4.1-fold enhancement in the A–B permeability rates were observed for His-Leu-LPV relative to LPV in MDCK-MDR1 and MDCK-MRP2 cells respectively.

Fig. 5.

A–B permeability of LPV, Leu-LPV, His-Leu-LPV and LPV in presence of GF120918 and MK571 across MDCK-MDR1 and MDCK-MRP2 cells repsectively. The standard deviation for each data point was averaged over four samples (n=4). **P<0.05 compared with the control group.

4.6. Interaction with peptide/histidine transporter (PepT1 and PHT1)

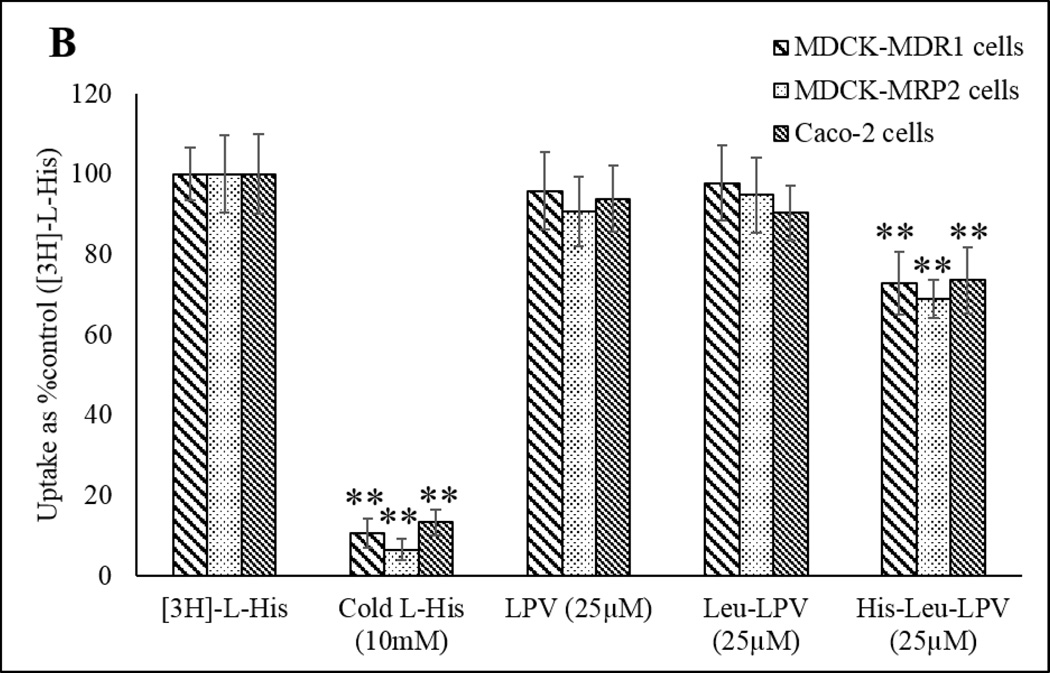

To study the interaction of LPV, Leu-LPV and His-Leu-LPV with PepT1 and PHT1 influx transporters, uptake studies were performed in MDCK-MDR, MDCK-MRP2 and Caco-2 cell lines. Glycylsarcosine (GlySar) and Histidine (His) were used as model substrates for peptide (PepT1) and histidine transporters (PHT1) respectively. Uptake of [3H]-GlySar (0.5 µCi/mmol) was performed in presence of cold GlySar, LPV, Leu-LPV and His-Leu-LPV to determine extent of prodrug interaction with peptide transporters (PepT1). Results obtained from this study demonstrating [3H]-GlySar uptake are depicted in Fig. 6 A. Approximately 35% reduction was observed in uptake of His-Leu-LPV in all the cell lines in contrast to 75% reduction in presence of cold GlySar. Furthermore, [3H]-His uptake (0.5 µCi/mmol) was performed in presence of cold His, LPV, Leu-LPV and His-Leu-LPV in MDCK--MDR, MDCK-MRP2 and Caco-2 cell lines to determine prodrug interaction with peptide/histidine transporter (PHT1). [3H]-His uptake results have been demonstrated in Fig. 6 B. Approximately 30% reduction was observed in uptake of His-Leu-LPV in all the cell lines in contrast to 90% reduction in presence of cold His.

Fig. 6.

Cellular uptake studies of [3H]-GlySar (A) and [3H]-L-His (B) in presence of cold GlySar/ cold L-His (10mM), LPV, Leu-LPV and His-Leu-LPV (25µM) in MDCK-MDR1, MDCK-MRP2 and Caco-2 cells. The standard deviation for each data point was averaged over four samples (n=4). **P<0.05 compared with the control group.

4.7. Caco-2 cell homogenate studies

Enzymatic hydrolysis of prodrugs were also determined in Caco-2 cell homogenate at pH 7.4 for a period of 4h. As depicted in Fig. 8, intact His-Leu-LPV, both intermediate amino acid prodrug (Leu-LPV) and regenerated parent drug (LPV) from His-Leu-LPV were detected in homogenate samples. The degradation of His-Leu-LPV was found to be rapid in cell homogenates. At the end of 4h, approximately 6% of His-Leu-LPV was detected. Degradation rate constant and half-life of His-Leu-LPV were found to be 5.38 ± 0.13 × 10−3 min−1 and 2.15 ± 0.06 h, respectively. Fig. 7 depicts concentrations of regenerated LPV and Leu-LPV from His-Leu-LPV in Caco2 cell homogenates. Leu-LPV degradation rate constant and half-life values were also determined and observed to be 1.37 ± 0.07 × 10−3 min−1 and 8.5 ± 0.4h, respectively (figure not shown).

Fig. 8.

LCMS/MS (MRM mode) spectra of His-Leu-LPV in Caco-2 cell homogenate at various time points as indicated in the figure.

Fig. 7.

Degradation profile (nmol/ml of drug vs time) for His-Leu-LPV in Caco-2 cell homogenate. The standard deviation for each data point was averaged over four samples (n=4).

5. Discussion

LPV, a powerful HIV-1 protease inhibitor, is commonly indicated in combinations with other antiretroviral agents for the treatment of HIV-1 infections. Despite its high antiviral efficacy, poor oral bioavailability poses a major challenge. The major reasons attributing to low oral absorption are poor aqueous solubility and significant efflux mediated by P-gp and MRP2 at the intestinal epithelium. In the present study, histidine peptide prodrug approach has been employed to overcome these challenges since PHT1 influx transporter is reported to be expressed on the apical surface of intestinal epithelial cells (Bhardwaj et al., 2006). It is anticipated that His-Leu-LPV prodrug might be recognized by both PHT1 and peptide (PepT1 and PepT2) transporters while simultaneously evading P-gp and MRP2 efflux pumps. Therefore, the physicochemical and affinity profiles of His-Leu-LPV towards P-gp and MRP2 have been determined and reported in this study. To synthesize His-Leu-LPV, Leu-LPV intermediate was first produced by esterifying the hydroxyl group of LPV with carboxylic group of leucine. Then, the amine group of intermediate Leu-LPV was coupled with carboxylic group of histidine to generate His-Leu LPV. Both intermediate Leu-LPV and His-Leu-LPV have been identified and characterized by LCMS and NMR techniques. Furthermore, both His-Leu-LPV and intermediate Leu-LPV have been characterized for physicochemical and substrate affinity profiles.

Aqueous solubilities of Leu-LPV and His-Leu-LPV were first determined. Both compounds exhibited markedly higher saturated aqueous solubility relative to LPV, which is poorly soluble. Such enhancement in aqueous solubility profiles might offer potential opportunities for the development of superior oral formulations. However, lower aqueous solubility of His-Leu-LPV in comparison to Leu-LPV could be attributed to its neutrally charged histidine moiety at pH 7.4. In fact, histidine carry a net positive charge resulting in higher solubility at lower pHs which was well demonstrated with the solubility profiles of these prodrugs. Notably, due to poor aqueous solubility, LPV is often administered to HIV-1 patients in the form of 40% v/v alcoholic solution which significantly increases the risk of developing toxicities in pediatric patients. Hence, significant rise in aqueous solubility by prodrugs may offer tremendous benefits for both delivery and formulation perspective. For oral administrations, an ideal prodrug should be stable at acidic pH (stomach) and be readily available at higher concentrations for intestinal absorption. Hence, it is extremely crucial to ascertain the chemical hydrolytic rate of Leu-LPV and His-Leu-LPV under acidic and mild basic conditions (Table 1). Both Leu-LPV and His-Leu-LPV were found to be more stable at lower pHs. However, both compounds hydrolyzed rapidly at pH 7.4 relative to pH 4. These results indicate that prodrugs would be stable under acidic pH conditions and degrade rapidly with rise in pH (stomach to colon). Interestingly, the intermediate Leu-LPV was found to be more stable relative to His-Leu-LPV at pH 7.4.

Cytotoxicity studies were conducted prior to avoid use of cytotoxic concentrations in uptake and transport studies (Fig. 2). LPV and prodrugs were found to be non-toxic to cells in the concentration range of 5–50 µM. However, these compounds exhibited significant cytotoxicity at higher concentrations such as 100 and 200 µM. Based on these results, all uptake and transport studies were performed at concentrations ≤ 50 µM. Drug efflux pumps such as P-gp and MRP2, highly expressed on the human epithelial and brain capillary endothelial cells, have played a significant role in the disposition of a wide range of therapeutic agents (Amin, 2013; Murakami and Takano, 2008; Takano et al., 2006). Previously, several reports have demonstrated the substrate affinity of LPV towards P-gp and MRP2 (Agarwal et al., 2008). Hence, it is very important that the synthesized prodrugs in the present study are efficient in circumventing these efflux pumps. The interaction of LPV and prodrugs with P-gp and MRP2 have been studied in MDCK-MDR1 and MDCK-MRP2 cells. These cell lines were selected since they serve as an excellent in vitro cell culture models in substrate affinity studies (Agarwal et al., 2008). The functional activities of P-gp and MRP2 in MDCK-MDR1 and MDCK-MRP2 cells were assessed. Then LPV uptake and transport studies were carried out in the presence and absence of P-gp (GF 120918), and MRP2 (MK 571) inhibitors in ambient conditions. Cellular uptake and transport rates of LPV were drastically elevated in the presence of P-gp and MRP2 inhibitors in MDCK-MDR1 and MDCK-MRP2 cells, respectively (Figs. 3, 5). Based on these results, it is apparent that P-gp and MRP2 are highly functional in the selected cell lines.

Prodrugs were then examined for their efficacy in overcoming efflux processes through a series of concentration dependent uptake studies of LPV, Leu-LPV and His-Leu-LPV. Cellular uptake of [3H]-LPV rapidly increased with rise in concentrations of unlabelled LPV (5, 10 and 25 µM) in both cell lines (Fig. 4). This result further supports the substrate affinity of LPV towards P-gp and MRP2. Interestingly, [3H]-LPV uptake didn’t alter significantly with increasing concentrations of Leu-LPV and His-Leu-LPV in both cell lines. Hence, it appears that these compounds have lower substrate affinity towards P-gp and MRP2. Based on these results, it may be anticipated that these compounds will efficiently circumvent efflux pumps and thereby generate higher absorption across intestinal epithelial cells. However, it is very crucial that prodrugs generate higher permeability rates across polarized membranes to improve net LPV absorption. Therefore, transport rates of Leu-LPV and His-Leu-LPV were determined across MDCK-MDR1 and MDCK-MRP2 cells. Previously, P-gp and MRP2 have been demonstrated to be functionally active on the apical surface of MDCK-transfected cell lines. Moreover, these efflux pumps have been reported to play a prominent role in diminishing transport rates of LPV in the absorptive direction (A–B). Hence, the efficacy of Leu-LPV and His-Leu-LPV to circumvent efflux pumps and generate higher permeability rates relative to LPV was assessed by conducting A–B transepithelial transport studies. As observed in Fig. 5, Leu-LPV generated about 2-fold higher A–B permeability rates across MDCK-MDR1 and MDCK-MRP2 cells relative to LPV. Under physiological conditions, His-Leu-LPV may degrade chemically or enzymatically to produce Leu-LPV in the gastrointestinal tract or systemic circulation post oral dosing. Since Leu-LPV can efficiently bypass efflux pumps, application of His-Leu-LPV in improving oral and brain absorption of LPV offers additional advantages. Importantly, A-B permeability of His-Leu-LPV was highly superior relative to LPV, a 4.3-fold increase. These results suggest that His-Leu-LPV possesses lower affinity towards P-gp and MRP2 relative to LPV. Such higher permeability rates may possibly be due to interaction with peptide influx transporters, highly expressed in MDCK transfected cells (Wang et al., 2013), with simultaneous circumvention of efflux pumps. Based on these observations, His-Leu-LPV is anticipated to generate higher transport across poorly permeable intestinal epithelium barrier.

Further to confirm the affinity of these prodrugs towards peptide (PepT1) and histidine (PHT1) transporters, uptake studies were carried out in presence of [3H]-GlySar and [3H]-His in MDCK-MDR1, MDCK-MRP2 and Caco-2 cell lines. [3H]-GlySar and [3H]-L-His uptake reduced significantly in presence of cold GlySar and cold L-His respectively indicating expression of functionally active peptide/histidine transporters in all the cell lines. As observed in Fig. 6 A, [3H]-GlySar uptake receded to approximately 30% in the presence of His-Leu-LPV. Similar results were obtained for [3H]-L-His uptake in presence of His-Leu-LPV (Fig. 6 B). However, no such variation in the uptake was observed in presence of LPV and Leu-LPV. These results suggested the competence of His-Leu-LPV over Leu-LPV and LPV to serve as a substantial substrate of peptide/histidine transporters thus proving our hypothesis for dual targeted approach.

In addition, enzymatic hydrolysis was studied in Caco2 cells to examine the reconversion of His-Leu-LPV to LPV. The prodrug degraded rapidly to regenerate Leu-LPV and LPV over a period of 4h. A steady regeneration of LPV and Leu-LPV was observed which suggests that His-Leu-LPV undergoes both esterase and peptidase-mediated hydrolysis. Esterase-mediated degradation of His-Leu-LPV will yield LPV whereas peptidase-mediated hydrolysis will generate Leu-LPV. Based on the amounts of LPV regenerated in the cell homogenates samples, it is quite evident that enzymatic cleavage of prodrugs is dominated by esterases class of enzymes in comparison to peptidases (Fig. 7). However, the extent of contribution of esterase and peptidase enzymes in His-Leu-LPV hydrolysis remains to be determined. Additionally, as observed in Fig. 8, the elevated peak of LPV in comparison to His-Leu-LPV at time 0 could be attributed to high sensitivity of LC-MS/MS method for LPV. Nevertheless, it is apparent that His-Leu-LPV potentially undergoes enzymatic hydrolysis to produce LPV.

Previously our laboratory has demonstrated stability studies of such dipeptide based prodrugs (Val-Ile-LPV) after single oral dose administration in Sprague Dawley rats. Area under the curve (AUC) of Val-Ile-LPV was observed to be 1439 ± 296 min*umol/L which is about 8-fold higher compared to LPV (177 ± 5 min*umol/L). AUC of regenerated Ile-LPV and LPV were found to be 432 ± 86 and 179 ± 25 min*umol/L respectively. Consequently, the half-life generated by regenerated LPV was 6-fold higher compared to LPV itself. Interestingly, regenerated LPV (604 min) displayed 3-fold higher mean residential time (MRT) compared to LPV (188 min). Such higher half-life and MRT of regenerated LPV compared to LPV itself could be due to slower (a) regeneration from Val-Ile-LPV and/or Ile-LPV and (b) elimination from systemic circulation (Patel, 2014). We anticipate the dual targeting ability of His-Leu-LPV will concede much better pharmacokinetic profile in vivo in comparison to previously synthesized prodrugs of LPV.

6. Conclusion

Poor aqueous solubility and higher affinity towards drug efflux pumps and metabolizing enzymes (CYP3A4) pose a major challenge to LPV delivery. The present study demonstrates the potential of a prodrug approach to improve LPV absorption across P-gp and MRP2 overexpressing polarized membranes. Prodrugs, Leu-LPV and His-Leu-LPV, developed in this study were more water soluble relative to LPV. Moreover, these compounds possessed lower affinity towards P-gp and MRP2 relative to LPV. His-Leu-LPV exhibited both PepT1 and PHT1 transporters mediated cellular uptake. In future studies, prodrug (a) competitive bidirectional transport in presence of PepT, and/or PHT substrates across blood-brain barrier (BBB), (b) metabolism in presence of esterase and protease inhibitor cocktails and human microsomes, (c) quantification of known CYP3A4 LPV metabolites, (d) plasma protein binding, (e) chemical stability studies in buffers with adequate buffer capacity at different pHs and (f) oral absorption studies in rats will be reported.

Acknowledgments

This work was mainly supported by NIH grants R01AI071199. Authors would like to extend their sincerest appreciation to Abbott Laboratories Inc. for providing with unlabeled LPV and GF120918. We would also like to thank Dr. Ankit Shah and Dr. Mitesh Patel for their valuable help and guidance.

ABBREVIATIONS

- HAART

Highly active antiretroviral therapy

- HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus

- LPV

Lopinavir

- PHT1

Peptide/histidine transporter

- PepT1/PepT2

Peptide transporters

- TEER

Transepithelial electric resistance

- GlySar

Glycylsarcosine

- His

Histidine

- Leu

Leucine

- P-gp

Permeability glycoprotein

- MRP2

Multidrug resistance-associated protein 2

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Agarwal S, Boddu SH, Jain R, Samanta S, Pal D, Mitra AK. Peptide prodrugs: improved oral absorption of lopinavir, a HIV protease inhibitor. International journal of pharmaceutics. 2008;359:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2008.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin ML. P-glycoprotein Inhibition for Optimal Drug Delivery. Drug target insights. 2013;7:27–34. doi: 10.4137/DTI.S12519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand Y, Capdeville R, Balduck N, Philippe N. Cyclosporin A used to reverse drug resistance increases vincristine neurotoxicity. American journal of hematology. 1992;40:158–159. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830400222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhardwaj RK, Herrera-Ruiz D, Eltoukhy N, Saad M, Knipp GT. The functional evaluation of human peptide/histidine transporter 1 (hPHT1) in transiently transfected COS-7 cells. European journal of pharmaceutical sciences : official journal of the European Federation for Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2006;27:533–542. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2005.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandwani A, Shuter J. Lopinavir/ritonavir in the treatment of HIV-1 infection: a review. Therapeutics and clinical risk management. 2008;4:1023–1033. doi: 10.2147/tcrm.s3285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christians U. Transport proteins and intestinal metabolism: P-glycoprotein and cytochrome P4503A. Therapeutic drug monitoring. 2004;26:104–106. doi: 10.1097/00007691-200404000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cvetkovic RS, Goa KL. Lopinavir/ritonavir: a review of its use in the management of HIV infection. Drugs. 2003;63:769–802. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200363080-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera-Ruiz D, Wang Q, Gudmundsson OS, Cook TJ, Smith RL, Faria TN, Knipp GT. Spatial expression patterns of peptide transporters in the human and rat gastrointestinal tracts, Caco-2 in vitro cell culture model, and multiple human tissues. AAPS pharmSci. 2001;3:E9. doi: 10.1208/ps030109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Xie Y, Keep RF, Smith DE. Divergent developmental expression and function of the proton-coupled oligopeptide transporters PepT2 and PhT1 in regional brain slices of mouse and rat. Journal of neurochemistry. 2014;129:955–965. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes PJ, Cretton-Scott E, Teague A, Wensel TM. Protease Inhibitors for Patients With HIV-1 Infection: A Comparative Overview. P & T : a peer-reviewed journal for formulary management. 2011;36:332–345. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kansara V, Hao Y, Mitra AK. Dipeptide monoester ganciclovir prodrugs for transscleral drug delivery: targeting the oligopeptide transporter on rabbit retina. Journal of ocular pharmacology and therapeutics : the official journal of the Association for Ocular Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2007;23:321–334. doi: 10.1089/jop.2006.0150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr DJ, Graham J, Cummings J, Morrison JG, Thompson GG, Brodie MJ, Kaye SB. The effect of verapamil on the pharmacokinetics of adriamycin. Cancer chemotherapy and pharmacology. 1986;18:239–242. doi: 10.1007/BF00273394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kis O, Robillard K, Chan GN, Bendayan R. The complexities of antiretroviral drug-drug interactions: role of ABC and SLC transporters. Trends in pharmacological sciences. 2010;31:22–35. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo S, Wang Z, Patel M, Khurana V, Zhu X, Pal D, Mitra AK. Targeting SVCT for enhanced drug absorption: synthesis and in vitro evaluation of a novel vitamin C conjugated prodrug of saquinavir. International journal of pharmaceutics. 2011;414:77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahato R, Tai W, Cheng K. Prodrugs for improving tumor targetability and efficiency. Advanced drug delivery reviews. 2011;63:659–670. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal A, Patel M, Sheng Y, Mitra AK. Design of lipophilic prodrugs to improve drug delivery and efficacy. Current drug targets. 2015 doi: 10.2174/1389450117666151209115431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami T, Takano M. Intestinal efflux transporters and drug absorption. Expert opinion on drug metabolism & toxicology. 2008;4:923–939. doi: 10.1517/17425255.4.7.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel M. Ph.D. Dissertation. Kansas City, MO: University of Missouri-Kansas City; 2014. title. [Google Scholar]

- Patel M, Vadlapatla RK, Shah S, Mitra AK. Molecular expression and functional activity of sodium dependent multivitamin transporter in human prostate cancer cells. International journal of pharmaceutics. 2012;436:324–331. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rautio J, Kumpulainen H, Heimbach T, Oliyai R, Oh D, Jarvinen T, Savolainen J. Prodrugs: design and clinical applications. Nature reviews. Drug discovery. 2008;7:255–270. doi: 10.1038/nrd2468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senise JF, Castelo A, Martinez M. Current treatment strategies, complications and considerations for the use of HIV antiretroviral therapy during pregnancy. AIDS reviews. 2011;13:198–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano M, Yumoto R, Murakami T. Expression and function of efflux drug transporters in the intestine. Pharmacology & therapeutics. 2006;109:137–161. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talluri RS, Gaudana R, Hariharan S, Mitra AK. Pharmacokinetics of Stereoisomeric Dipeptide Prodrugs of Acyclovir Following Intravenous and Oral Administrations in Rats: A Study Involving In vivo Corneal Uptake of Acyclovir Following Oral Dosing. Ophthalmology and eye diseases. 2009;1:21–31. doi: 10.4137/oed.s2857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Pal D, Mitra AK. Stereoselective evasion of P-glycoprotein, cytochrome P450 3A, and hydrolases by peptide prodrug modification of saquinavir. Journal of pharmaceutical sciences. 2012;101:3199–3213. doi: 10.1002/jps.23193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Pal D, Patel A, Kwatra D, Mitra AK. Influence of overexpression of efflux proteins on the function and gene expression of endogenous peptide transporters in MDR-transfected MDCKII cell lines. International journal of pharmaceutics. 2013;441:40–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2012.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwarycz B, Wong EA. Expression of the peptide transporters PepT1, PepT2, and PHT1 in the embryonic and posthatch chick. Poultry science. 2013;92:1314–1321. doi: 10.3382/ps.2012-02826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]