Routine quantification of myocardial blood flow (MBF) in absolute units of mL/min/g has long been one of the technical milestones expected to enable the widespread clinical application of cardiac positron emission tomography (PET). The recent study by Germino et al. [1] contributes significantly to the increasing body of literature supporting the potential for rubidium-82 (82Rb) PET to become the de facto clinical standard method for non-invasive quantification of MBF and myocardial flow reserve (MFR) in the routine diagnosis and management of patients with ischemic heart disease. The authors are commended for completing a very technically challenging study, including three-dimensional PET parametric imaging and arterial blood sampling validation with the ultra-short-lived tracers 82Rb and 15O-water.

82Rb is currently the most widely used tracer for PET myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI) in North America, and its use is increasing in Europe and in other parts of the world. While the diagnostic accuracy of 82Rb PET for routine MPI is accepted to be slightly higher than 201Tl or 99mTc-based SPECT methods [2] and is recommended over SPECT in certain patient sub-groups [3], the full added value of PET for MBF quantification has yet to be realized in improving patient management to reduce adverse cardiac outcomes such as myocardial infarction and death. In the present issue, Germino and co-authors have solidified the foundation upon which future clinical trials can be performed to help achieve this long-term goal. To have full confidence in MBF PET imaging results sufficient to direct optimal therapies in the clinical routine, the following criteria should be demonstrated.

Rigorous validation (accuracy)

The tracer kinetics of 82Rb were first shown in rabbits to follow a two-compartment model [4], but a simpler one-tissue-compartment model (1TCM) has been shown to be adequate to describe the typical kinetic profiles in human and animal model studies [5]. This 1TCM has only three parameters, which Germino et al. used successfully for the estimation of parametric images showing the influx-rate (K1 uptake), efflux-rate (k2 washout), and fractional blood volume (VA spillover). MBF values are derived from the uptake-rate K1, using a tracer extraction function E(MBF) calibrated to an accepted gold-standard. In experimental animal studies, ex vivo quantification of radioisotope- or fluorescent-labeled microspheres has been used to validate dynamic PET MBF measurements using 15O-water and 13N-ammonia, both of which are (nearly) freely diffusible across capillary and cell membranes [6, 7]. Because the microsphere technique cannot be used in humans, the 1TCM method for 82Rb MBF was validated originally against 13N-ammonia in healthy normal subjects and heart disease patients using 3D dynamic PET and filtered-back-projection analytic reconstruction [8]. The estimated extraction function was then confirmed with 15O-water measurements using 2D dynamic PET and iterative reconstruction [9]. These findings are now re-confirmed by Germino et al. using state-of-the-art 3D PET-CT parametric imaging with iterative time-of-flight reconstruction and detector response modeling. There are several important findings in their study that highlight the need for attention to the methodological details, in comparing or standardizing 82Rb MBF measurements between different imaging laboratories.

As in a previous study by Weinberg [10] 82Rb arterial blood samples were compared to the PET image-derived blood input functions (IDIF). In the present study, Germino et al. found a small under-estimation (−3 and −8 %) in the 15O-water and 82Rb IDIF values, that was not time-dependent, and could therefore be corrected by simple scaling. The authors propose that the source of this small bias may be related to technical factors, e.g., positron range or other resolution effects, but may also be attributed to physiological factors, e.g., red blood cell uptake which has been demonstrated with other potassium analogs such as 201Tl [11]. Similar to 15O-water, 82Rb does not bind to plasma proteins nor does it have any radioactive metabolites in arterial blood or myocardial tissue, which can complicate the tracer kinetic analysis of other MBF tracers such as 13N-ammonia [12].

As the source of the reported IDIF bias was not confirmed, the authors explain that the derived scale-factor may be “scan dependent, conditional on variations in VOI size and placement, heart size, breathing pattern, and subject motion. Further investigation is required to assess generalizability to other scanners and reconstruction algorithms.” However, it is important to note that regardless of the cause of the apparent bias, when the measured 82Rb IDIF values were used without the scaling correction, the corresponding extraction fraction parameters were very similar to those reported by Lortie [8, 9].

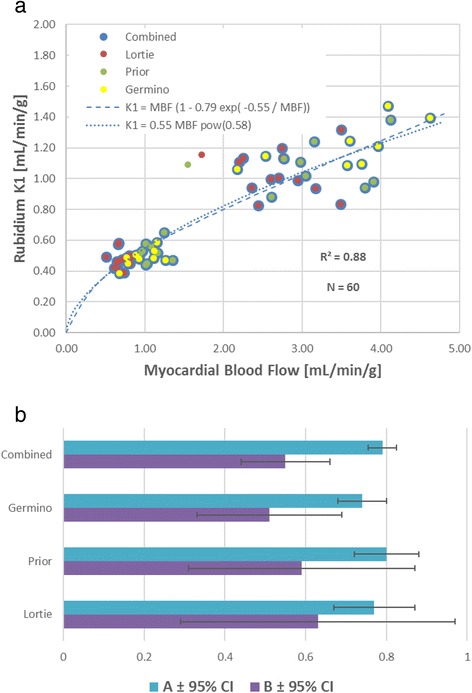

By combining the new data from Germino et al. together with these two previous studies, which all used comparable implementations of the 1TCM (without any blood input function correction), we can improve the estimation of the 82Rb extraction function parameters (Fig. 1a), which in turn should improve the precision of the derived MBF estimates [13, 14]. Contrary to previous reports [15], these data clearly demonstrate that there is no “roll-off” of tracer uptake-rate using the 1TCM, as the K1 values continue to increase with MBF over the range of physiological values measured in these human studies. Interestingly, an empirical power function appears to describe the rubidium K1 vs. MBF relationship as well as the more physiological Renkin-Crone tracer extraction formulation. Recognizing that the fitted functions shown in Fig. 1a are intended primarily to “calibrate” the 82Rb uptake rates (K1) for accurate estimation of MBF, a strict physiological interpretation is not required. Therefore, it would seem appropriate to use a function similar to one that fits the “combined” data of these three validation studies. It is encouraging that these combined results seem to be relatively independent of the particular scanning hardware, acquisition protocol, image reconstruction, and software analysis methods used in the respective studies individually.

Fig. 1.

a Combined estimation (N = 60) of 82Rb extraction function parameters from three validation studies performed in humans using the one-tissue-compartment model, without correction (spillover or scaling) of the arterial blood input function. b Combined estimates of the 82Rb extraction parameters: A (0.79 ± 0.035) and B (0.55 ± 0.11) demonstrate improved precision vs. individual studies (Germino, Prior, Lortie). Confidence interval (CI) values derived from Table 3 in Germino et al. [1]

Repeatability (test-retest and operator variability)

Several studies have demonstrated very good repeatability of measured MBF values using 82Rb dynamic PET, on the order of ±5 % limits-of-agreement when compared within or between operators Klein et al. [16] and ±20 % between sequential imaging sessions under both rest and hyperemic stress conditions [17–19]. Test-retest repeatability of 82Rb MBF was substantially higher (±35–40 %) when measured on separate days, and analyzed using a tracer retention model [20], which is a further simplification of the 1TCM that measures the net effects of tracer uptake and washout. MBF test-retest repeatability can be improved to ±10–15 % by using a standardized “square-wave” tracer infusion profile, available with the latest 82Rb generator system [21].

Reproducibility (multi-center standardization)

The commonly applied 1TCM for 82Rb [8] does not require any a priori assumed methodological constants (e.g., tissue distribution volume, blood integration interval, myocardial wall-thickness, or partial-volume recovery coefficient) or physiological constants (except the ubiquitous extraction function), making the model widely applicable and reproducible despite local variations in PET scanner technology (e.g., 2D vs. 3D), dynamic sampling (2 to 10 min), image reconstruction (analytic vs. iterative ± time-of-flight or detector response modeling), and computer software implementations [22–25].

The three human 82Rb validation studies using the same 1TCM have produced consistent estimates of the extraction function parameters (Fig. 1b) with overlapping 95 % confidence intervals (CI). Murthy et al. [26] have also demonstrated similar prognostic value between 1TCM variant methods when stress/rest myocardial flow reserve (MFR) was used to predict patient adverse outcomes. Despite these significant advances, some challenges remain in terms of weight-based dosing to maintain MBF accuracy with early-generation 3D PET technologies [27, 28] and standardization of hyperemic stress response when using different pharmacologic stressors such as dobutamine, adenosine, adenosine triphosphate, dipyridamole, or regadenoson [29].

Revascularization vs. medical therapy decisions (clinical and cost effectiveness)

As the availability of 82Rb continues to increase and standardization of PET MBF methods improves between imaging laboratories, the ability to conduct multi-center trials demonstrating the clinical value to direct effective therapies will improve accordingly. The cardiac PET community could strive to produce non-invasive imaging evidence similar to the pivotal FAME trial [30] which used invasive measurements of fractional flow reserve (FFR) to identify flow-limiting stenoses associated with myocardial ischemia, direct effective therapy, improve patient outcomes, and reduce treatment costs, leading to revised European Society of Cardiology guidelines for myocardial revascularization in patients with ischemic heart disease [31].

Johnson et al. [32] have proposed a stress PET MBF threshold ~0.9 mL/min/g to identify definite myocardial ischemia; however, the relative value of stress MBF vs. stress/rest MFR remains to be elucidated for the optimal detection of disease and management of therapy decisions [33]. In this regard, it is critical to understand the differences between the measurement of epicardial FFR vs. epicardial + microvascular MFR, as elegantly described by Johnson and Gould [34, 35]. The addition of CT coronary angiography or microvascular-specific tests of endothelial function may have a role to play in the differential diagnosis of macro- (CTA) vs. micro-vascular (PET) disease, which should be amenable to revascularization vs. medical therapies respectively [36]. Prospective studies are needed to evaluate the role of PET MBF and MFR to direct therapies such as revascularization. In the meantime current clinical trials such as the DEFINE-FLOW study which is using invasive measures of fractional and coronary flow reserve will help to define the potential clinical role of non-invasive PET MFR to complement invasive FFR measurements of the physiologic consequences of coronary atherosclerosis [37]. Limited US data available supports the cost effectiveness of 82Rb PET MPI when used consistently in patients with intermediate pre-test likelihood of disease [38]; comparable studies are still needed in the European setting, to establish the financial value or impact of 82Rb for conventional MPI and the potential added value of routine quantification of MBF.

References

- 1.Germino M, Ropchan J, Mulnix T, Fontaine K, Nabulsi N, Ackah E, Feringa H, Sinusas AJ, Liu C, Carson RE. Quantification of myocardial blood flow with 82Rb: validation with 15Owater using time-of-flight and point-spread-function modeling. Eur J Nucl Med Res. 2016 [in press] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Mc Ardle BA, Dowsley TF, deKemp RA, Wells GA, Beanlands RS. Does rubidium-82 PET have superior accuracy to SPECT perfusion imaging for the diagnosis of obstructive coronary disease?: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(18):1828–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Timothy M. Bateman (Co-Chair), Vasken Dilsizian (Co-Chair), Rob S. Beanlands, E. Gordon DePuey, Gary V. Heller, David A. Wolinsky. American Society of Nuclear Cardiology and Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging Joint Position Statement on the Clinical Indications for Myocardial Perfusion PET. J Nucl Cardiol. 2016. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Huang SC, Williams BA, Krivokapich J, Araujo L, Phelps ME, Schelbert HR. Rabbit myocardial 82Rb kinetics and a compartmental model for blood flow estimation. Am J Physiol. 1989;256(4 Pt 2):H1156–64. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.256.4.H1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coxson PG, Huesman RH, Borland L. Consequences of using a simplified kinetic model for dynamic PET data. J Nucl Med. 1997;38(4):660–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bergmann SR, Fox KA, Rand AL, McElvany KD, Welch MJ, Markham J, Sobel BE. Quantification of regional myocardial blood flow in vivo with H215O. Circulation. 1984;70(4):724–33. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.70.4.724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schelbert HR, Phelps ME, Huang SC, MacDonald NS, Hansen H, Selin C, Kuhl DE. N-13 ammonia as an indicator of myocardial blood flow. Circulation. 1981;63(6):1259–72. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.63.6.1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lortie M, Beanlands RS, Yoshinaga K, Klein R, Dasilva JN, DeKemp RA. Quantification of myocardial blood flow with 82Rb dynamic PET imaging. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2007;34(11):1765–74. doi: 10.1007/s00259-007-0478-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prior JO, Allenbach G, Valenta I, Kosinski M, Burger C, Verdun FR, Bischof Delaloye A, Kaufmann PA. Quantification of myocardial blood flow with 82Rb positron emission tomography: clinical validation with 15O-water. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2012;39(6):1037–47. doi: 10.1007/s00259-012-2082-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weinberg IN, Huang SC, Hoffman EJ, Araujo L, Nienaber C, Grover-McKay M, Dahlbom M, Schelbert H. Validation of PET-acquired input functions for cardiac studies. J Nucl Med. 1988;29(2):241–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cavieres JD, Ellory JC. Thallium and the sodium pump in human red cells. J Physiol. 1974;243(1):243–66. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1974.sp010752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosenspire KC, Schwaiger M, Mangner TJ, Hutchins GD, Sutorik A, Kuhl DE. Metabolic fate of [13 N]ammonia in human and canine blood. J Nucl Med. 1990;31(2):163–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moody JB, Murthy VL, Lee BC, Corbett JR, Ficaro EP. Variance estimation for myocardial blood flow by dynamic PET. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2015;34(11):2343–53. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2015.2432678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moody JB, Lee BC, Corbett JR, Ficaro EP, Murthy VL. Precision and accuracy of clinical quantification of myocardial blood flow by dynamic PET: a technical perspective. J Nucl Cardiol. 2015;22(5):935–51. doi: 10.1007/s12350-015-0100-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herrero P, Markham J, Shelton ME, Weinheimer CJ, Bergmann SR. Noninvasive quantification of regional myocardial perfusion with rubidium-82 and positron emission tomography. Exploration of a mathematical model. Circulation. 1990;82(4):1377–86. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.82.4.1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klein R, Renaud JM, Ziadi MC, Thorn SL, Adler A, Beanlands RS, deKemp RA. Intra- and inter-operator repeatability of myocardial blood flow and myocardial flow reserve measurements using rubidium-82 pet and a highly automated analysis program. J Nucl Cardiol. 2010;17(4):600–16. doi: 10.1007/s12350-010-9225-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.El Fakhri G, Kardan A, Sitek A, Dorbala S, Abi-Hatem N, Lahoud Y, Fischman A, Coughlan M, Yasuda T, Di Carli MF. Reproducibility and accuracy of quantitative myocardial blood flow assessment with (82)Rb PET: comparison with (13)N-ammonia PET. J Nucl Med. 2009;50(7):1062–71. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.104.007831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manabe O, Yoshinaga K, Katoh C, Naya M, deKemp RA, Tamaki N. Repeatability of rest and hyperemic myocardial blood flow measurements with 82Rb dynamic PET. J Nucl Med. 2009;50(1):68–71. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.055673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Efseaff M, Klein R, Ziadi MC, Beanlands RS, deKemp RA. Short-term repeatability of resting myocardial blood flow measurements using rubidium-82 PET imaging. J Nucl Cardiol. 2012;19(5):997–1006. doi: 10.1007/s12350-012-9600-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sdringola S, Johnson NP, Kirkeeide RL, Cid E, Gould KL. Impact of unexpected factors on quantitative myocardial perfusion and coronary flow reserve in young, asymptomatic volunteers. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011;4(4):402–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klein R, Ocneanu A, Renaud JM, Ziadi MC, Beanlands RSB, deKemp RA. Consistent tracer administration profile improves test-retest repeatability of myocardial blood flow quantification with 82Rb dynamic PET imaging. J Nucl Cardiol. 2016 [in press]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.deKemp RA, Declerck J, Klein R, Pan XB, Nakazato R, Tonge C, Arumugam P, Berman DS, Germano G, Beanlands RS, Slomka PJ. Multisoftware reproducibility study of stress and rest myocardial blood flow assessed with 3D dynamic PET/CT and a 1-tissue-compartment model of 82Rb kinetics. J Nucl Med. 2013;54(4):571–7. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.112219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tahari AK, Lee A, Rajaram M, Fukushima K, Lodge MA, Lee BC, Ficaro EP, Nekolla S, Klein R, deKemp RA, Wahl RL, Bengel FM, Bravo PE. Absolute myocardial flow quantification with (82)Rb PET/CT: comparison of different software packages and methods. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2014;41(1):126–35. doi: 10.1007/s00259-013-2537-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nesterov SV, Deshayes E, Sciagrà R, Settimo L, Declerck JM, Pan XB, Yoshinaga K, Katoh C, Slomka PJ, Germano G, Han C, Aalto V, Alessio AM, Ficaro EP, Lee BC, Nekolla SG, Gwet KL, deKemp RA, Klein R, Dickson J, Case JA, Bateman T, Prior JO, Knuuti JM. Quantification of myocardial blood flow in absolute terms using (82)Rb PET imaging: the RUBY-10 Study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;7(11):1119–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dunet V, Klein R, Allenbach G, Renaud J, deKemp RA, Prior JO. Myocardial blood flow quantification by Rb-82 cardiac PET/CT: a detailed reproducibility study between two semi-automatic analysis programs. J Nucl Cardiol. 2016;23(3):499–510. doi: 10.1007/s12350-015-0151-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murthy VL, Lee BC, Sitek A, Naya M, Moody J, Polavarapu V, Ficaro EP, Di Carli MF. Comparison and prognostic validation of multiple methods of quantification of myocardial blood flow with 82Rb PET. J Nucl Med. 2014;55(12):1952–8. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.114.145342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moody JB, Hiller KM, Lee BC, Corbett JR, Ficaro EP, Murthy VL. Limitations of Rb-82 weight-adjusted dosing accuracy at low doses. J Nucl Cardiol. 2016. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Renaud JM, Yip K, Guimond J, Trottier M, Pibarot P, Turcotte E, Maguire C, Lalonde L, Gulenchyn KY, Farncombe TH, Wisenberg G, Moody JB, Lee BC, Port SC, Turkington T, Beanlands RS, deKemp R. Characterization of 3D PET systems for accurate quantification of myocardial blood flow. J Nucl Med. 2016. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Johnson NP, Gould KL. Regadenoson versus dipyridamole hyperemia for cardiac PET imaging. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8(4):438–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2014.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tonino PA, De Bruyne B, Pijls NH, Siebert U, Ikeno F, van’t Veer M, Klauss V, Manoharan G, Engstrøm T, Oldroyd KG, Ver Lee PN, MacCarthy PA, Fearon WF, FAME Study Investigators Fractional flow reserve versus angiography for guiding percutaneous coronary intervention. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(3):213–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Windecker S, Kolh P, Alfonso F, et al. 2014 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization: the Task Force on Myocardial Revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) developed with the special contribution of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI) Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2541–619. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson NP, Kirkeeide RL, Gould KL. Is discordance of coronary flow reserve and fractional flow reserve due to methodology or clinically relevant coronary pathophysiology? JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5(2):193–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2011.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Joutsiniemi E, Saraste A, Pietilä M, Mäki M, Kajander S, Ukkonen H, Airaksinen J, Knuuti J. Absolute flow or myocardial flow reserve for the detection of significant coronary artery disease? Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;15(6):659–65. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jet274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson NP, Gould KL. Physiological basis for angina and ST-segment change PET-verified thresholds of quantitative stress myocardial perfusion and coronary flow reserve. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011;4(9):990–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2011.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson NP, Gould KL. Integrating noninvasive absolute flow, coronary flow reserve, and ischemic thresholds into a comprehensive map of physiological severity. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5(4):430–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2011.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gould KL, Johnson NP, Bateman TM, Beanlands RS, Bengel FM, Bober R, Camici PG, Cerqueira MD, Chow BJ, Di Carli MF, Dorbala S, Gewirtz H, Gropler RJ, Kaufmann PA, Knaapen P, Knuuti J, Merhige ME, Rentrop KP, Ruddy TD, Schelbert HR, Schindler TH, Schwaiger M, Sdringola S, Vitarello J, Williams KA, Sr, Gordon D, Dilsizian V, Narula J. Anatomic versus physiologic assessment of coronary artery disease. Role of coronary flow reserve, fractional flow reserve, and positron emission tomography imaging in revascularization decision-making. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(18):1639–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.07.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnson N, Piek JJ. Combined pressure and flow measurements to guide treatment of coronary stenoses (DEFINE-FLOW). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02328820 [accessed 22 Aug 2016]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Merhige ME, Breen WJ, Shelton V, Houston T, D’Arcy BJ, Perna AF. Impact of myocardial perfusion imaging with PET and (82)Rb on downstream invasive procedure utilization, costs, and outcomes in coronary disease management. J Nucl Med. 2007;48(7):1069–76. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.106.038323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]