Abstract

Wolfiporia cocos is an edible and medicinal fungus that grows in association with pine trees, and its dried sclerotium, known as Fuling in China, has been used as a traditional medicine in East Asian countries for centuries. Nearly 10% of the traditional Chinese medicinal preparations contain W. cocos. Currently, the commercial production of Fuling is limited because of the lack of pine-based substrate and paucity of knowledge about the sclerotial development of the fungus. Since protein kinase (PKs) play significant roles in the regulation of growth, development, reproduction, and environmental responses in filamentous fungi, the kinome of W. cocos was analyzed by identifying the PKs genes, studying transcript profiles and assigning PKs to orthologous groups. Of the 10 putative PKs, 11 encode atypical PKs, and 13, 10, 2, 22, and 11 could encoded PKs from the AGC, CAMK, CK, CMGC, STE, and TLK Groups, respectively. The level of transcripts from PK genes associated with sclerotia formation in the mycelium and sclerotium stages were analyzed by qRT-PCR. Based on the functions of the orthologs in Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (a sclerotia-formation fungus) and Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the potential roles of these W. cocos PKs were assigned. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first identification and functional discussion of the kinome in the edible and medicinal fungus W. cocos. Our study systematically suggests potential roles of W. cocos PKs and provide comprehensive and novel insights into W. cocos sclerotial development and other economically important traits. Additionally, based on our result, genetic engineering can be employed for over expression or interference of some significant PKs genes to promote sclerotial growth and the accumulation of active compounds.

Keywords: Wolfiporia cocos, edible and medicinal fungus, sclerotial development, protein kinase (PKs), kinome

Introduction

Wolfiporia cocos (Schwein.) Ryvarden et Gilb. (Basidiomycota, Polyporaceae) is an edible fungus, and its sclerotia, known as Fuling in China, have been reported to possess important medicinal value (Dai et al., 2009; Esteban, 2009; Lin et al., 2009; Kobira et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2013). Pharmacological research pertaining to the two major active compounds from W. cocos sclerotia, polysaccharides and triterpenes, has demonstrated their multiple immune stimulatory and pharmacological activities (Rios, 2011; Feng et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2013, 2015a,b; Zhao et al., 2013; Tang et al., 2014; Gao et al., 2016).

Sclerotial formation of W. cocos is dependent on colonization of Pinus species (Wang et al., 2002; Kubo et al., 2006; Xiong et al., 2006; Xu et al., 2014). Therefore, commercial production of W. cocos sclerotia consumes a significant amounts of Pinus wood each year (Wang et al., 2012). In order to support efforts to improve the yield and efficiency of W. cocos sclerotia, the present study aimed to further knowledge of the regulatory mechanisms operating in the fungus.

In eukaryotic organisms, especially fungi, protein kinases (PKs) catalyze reversible phosphorylation of serine, threonine or tyrosine residues to control the activity of functional proteins, and they play significant roles in regulating growth, reproduction, developmental processes, and environmental stress responses (Cohen, 2000; Turrà et al., 2014). For example, in Sclerotinia sclerotiorum, a plant pathogenic fungus, silencing the mitogen-activated PK (MAPK) gene SMK1 resulted in impaired sclerotial formation (Chen et al., 2004). Sclerotia development of S. sclerotiorum is also associated with increased cAMP-dependent PK A (PKA) levels (Rollins and Dickman, 1998; Harel et al., 2005; Jurick and Rollins, 2007), indicating that the cAMP-PKA signaling pathway is important in the regulation of sclerotial development. In Botrytis cinerea, another plant pathogenic fungus, the HOG1-type MAPK BcSAK1 is involved not only in the response to osmotic stress but also in sclerotial development (Segmüller et al., 2007) and deletion of its bmp3 gene encoding a homolog of the yeast MAPK Slt2 results in the loss of sclerotial formation (Rui and Hahn, 2007).

In the present study, 103 putative PK genes were putatively identified in the W. cocos genome based on homologous sequences searching by using BLASTx program against the Saccharomyces cerevisiae and S. sclerotiorum databases. Based on known and presumed functions of the orthologs of these PK genes found in other fungi, the putative roles of these W. cocos PKs in colonization, mycelial growth, development and response to environmental stress were assigned. The data from our study contribute to a better understanding of the potential roles of PKs in various processes of W. cocos and will help to illuminate the mechanisms of sclerotial formation.

Materials and Methods

Strains and Culture Conditions

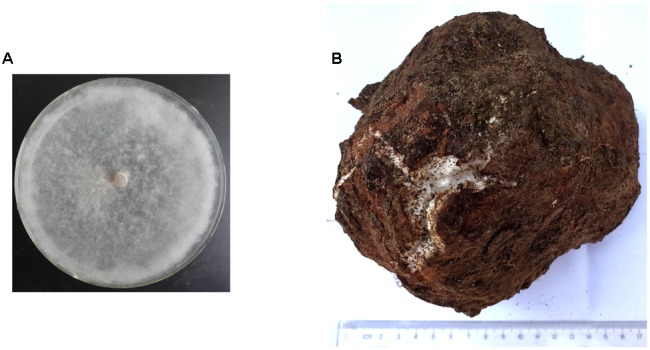

Sclerotium and mycelium of W. cocos (Figure 1) collected from Yingshan county, Hubei province, China (Shu et al., 2013) were kindly donated by Dr. Shaohua Shu at the Huazhong Agricultural University. W. cocos mycelium was grown on a cellophane membrane place on the surface of potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium at 28°C for 7 days. Both the mycelium and sclerotium were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C for total RNA extraction.

FIGURE 1.

The mycelium and sclerotia of Wolfiporia cocos used in this study. (A) Colony morphology W. cocos mycelium grown on PDA for 7 days at 25°C. (B) W. cocos mature sclerotium (6-months-old).

Identification of PKs

RNA-seq data from two samples of mycelium and sclerotium was from a previous study (Shu et al., 2013) and is accessible under accession number SRP018935 at NCBI1. Genome data was retrieved from the JGI database2.

Homologous sequence searches were performed with BLASTx against the S. cerevisiae database 3 and S. sclerotiorum database4 (≥e-5) as described (Hegedus et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2016).

To identify and classify the PKs, the protein sequences from W. cocos were searched against the Kinomer v.1.0 HMM library by the using of HMMSCAN program from the HMM software suite HMMer, and the cut off value was set to 20 as previously described (Miranda-Saavedra and Barton, 2007; Kosti et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2016).

Differential Expression Analysis

The RPKM method (Reads per kb per Million reads) was used to calculate RNA levels as previously described (Zhang et al., 2016; Mortazavi et al., 2008; Shu et al., 2013). To identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in mycelium and sclerotium, the statistical method of false discovery rate (FDR) was employed to correct the threshold of P-value in multiple tests. Those DEGs with a ratio ≥ 2 and an FDR ≤ 0.001 were chosen for this study. As previously described, the DEGs were analyzed with DEGSeq (Wang et al., 2010).

RNA Extraction and qRT-PCR Confirmation of PKs Gene Transcription

Total RNA of mycelium and sclerotium were extracted with TriZOL reagent (InvitrogenTM, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and treated with RNase-free DNase I (Qiagen Inc, Duesseldorf, Germany) to remove residual DNA according to manufacturer’s protocols. The High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied BiosystemsTM, Foster, CA, USA) was used to generate the first strand cDNA according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Gene expression was analyzed by qRT-PCR using a Bio-Rad CFX96 Real Time System (Bio-Rad, America) and SYBR Premix Ex Taq II (TAKARA, Dalian, China), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The PCR conditions were as follows: denaturation at 95°C for 3 min; 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 55°C for 15 s and 72°C for 30 s; final step of 72°C for 10 min. The primers for qRT-PCR are listed in Table 1. The mRNA levels of the W. cocos alpha-tubulin gene (Shu et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2016) were used to normalize the data for each qRT-PCR run. For each gene, qRT-PCR assays were repeated at least three times, with each repetition having three technical replicas.

Table 1.

Primers used for qRT-PCR.

| Primers used for qRT-PCR | |

|---|---|

| TPK2 (Wolco1| 107737) | TPK2 F: 5′ TCGTCAAAATGAAGCAGGTCT 3′ |

| TPK2 R: 5′ CGAAGAAGAGTGAATAGCTCCC 3′ | |

| HOG1(Wolco1| 95503) | HOG1 F: 5′ CAAACCGAGCAATATCCTAATC 3′ |

| HOG1 R: 5′ TGATCTCGGGCGCGCGGTAG 3′ | |

| FUS3 (Wolco1| 107181) | FUS3 F: 5′ ATGCTCAATACTTCATCTACCAAAC 3′ |

| FUS3 R: 5′ GACCGAGCGTGCGAGACCG 3′ | |

| SLT2 (Wolco1| 92114) | SLT2 F: 5′ GTGTGGTCCGTCGGATGCATT 3′ |

| SLT2 R: 5′ CGATGGCGTACCGAGGTAGT 3′ | |

| CLA4 (Wolco1| 121529) | CLA4 F: 5′ CGCCCGAGTCGTTGCGTC 3′ |

| CLA4 R: 5′ CATGATGGTCGCAGGCATCAC 3′ | |

| STE20 (Wolco1| 166770) | STE20 F: 5′ CGTACCAGCTCGGGACGAAC 3′ |

| STE20 R: 5′ CGAGTCGATGTAGTTTACGATGTTG 3′ | |

| STE11(Wolco1| 43954) | STE11 F: 5′ GGATGGACGCTTCAACGGGCTT 3′ |

| STE11 R: 5′ TCGTCAATGCATGAAGAGAGATACT 3′ | |

| STE7 (Wolco1| 150169) | STE7 F: 5′ ACGTCCCGACGGGCACGAT 3′ |

| STE7 R: 5′ TTGTCCATGAACTCCATGCAGATAC 3′ | |

| MKK2 (Wolco1| 75024) | MKK2 F: 5′ GCCGTCCAGCAGCGAGGT 3′ |

| MKK2 R: 5′ GAATGGTCTTCATCTTGTGGAGGT 3′ | |

| Alpha-tubulin | Alpha-tubulin F: 5′ ACTCCAGCTTGGACTTCTTG 3′ |

| Alpha-tubulin R: 5′ TCTTCGTCTTCCACTCCTTTG 3′ | |

Results

Predicted PKs in W. cocos

Our search of the W. cocos genome sequence identified a total of 103 putative PKs, 87 of them with significant similarity (≥e-5) to one or more of the 92 S. sclerotiorum and/or 115 S. cerevisiae PKs (Supplementary Table S1) (Hunter and Plowman, 1997; Hegedus et al., 2016). On the basis of conserved residues, 11 candidates belonged to the atypical PKs, 13 to the AGC Group, 10 to the CAMK Group, 2 candidates to the CK Group, 22 candidates to the CMGC Group, 11 to the STE Group, 10 to the TLK Group, and 24 to the Other Group (Supplementary Table S1). Compared with S. cerevisiae, W. cocos is predicted to have fewer PKs genes. It lacks orthologs of 30 S. sclerotiorum and/or S. cerevisiae PKs, including DBF2/4, ELM1, ALK1/2, PTK1/2, NPR1, HSL1, ISR1, YGR052W, YLR253W, YMR291W, HAL5, KKQ8, NNK1, PRR1/2, YPL150W, KCC4, MEK1, DUN1, KSP1, CAK1, SRB10, SSK2/SSK22, MPS1, PSK1/2, BUD32, TOS3, SAK1, SCY1, IKS1/2, and RAD53 (Supplementary Table S1). Moreover, W. cocos has two orthologs of CBK1 (Wolco1| 74908 and Wolco1| 70675), COQ8 (Wolco1| 138133 and Wolco1| 144299), PKP1 (Wolco1| 110818 and Wolco1| 92641), TEL1 (Wolco1| 108405 and Wolco1| 91919), VHS1 (Wolco1| 106038 and Wolco1| 155089), CDC28 (Wolco1| 91184 and Wolco1| 93694), SAT4 (Wolco1| 159823 and Wolco1| 134885), EVN7 (Wolco1| 137941 and Wolco1| 132412), ATG1 (Wolco1| 20796 and Wolco1| 109315), SPS1 (Wolco1| 95124 and Wolco1| 111584) and three orthologs of YAK1 (Wolco1| 64270, Wolco1| 97250 and Wolco1| 75698), SKY1 (Wolco1| 159141, Wolco1| 92467 and Wolco1| 95712), Pan3p (Wolco1| 164201, Wolco1| 138179 and Wolco1| 73826) (Supplementary Table S1). W. cocos also contains 16 putative PKs that have no distinct orthologs in S. cerevisiae and/or S. sclerotiorum.

AGC Group

The W. cocos AGC Group has 13 members. The PKs from the AGC Group are important in the regulation of signaling pathways in response to cell wall or membrane stress and limited nutrients. In S. cerevisiae, in response to limited nutrients and other stresses, the activity of YPK1/2, SCH9, RIM15, DBF2/20, TPK1/2 (PKA catalytic subunit) and PKC1 are directly or indirectly regulated by the atypical PKs TOR1 and TOR2 (the target of rapamycin; Jacinto and Lorberg, 2008; Turrà et al., 2014).

Like many other filamentous fungi, W. cocos contains two genes, Wolco1| 115209 and Wolco1| 107737, that encode the catalytic subunits of PKA, similar to S. cerevisiae TPK1 and TPK2, and S. sclerotiorum SS1G_03171 and SS1G_13577, respectively. In Fusarium graminearum, deletion of the PKA-encoding gene cpk1 causes significantly decreased vegetative growth, conidiation and deoxynivalenol production. Furthermore, the cpk1 mutant was also defective in ascospore maturation and releasing. In contrast, the mutant of another PKA-encoding gene, cpk2, had no detectable phenotypes (Hu et al., 2014). In S. cerevisiae, given elevated glucose levels, the activated PKA regulates SNF1 (Wolco1| 160811) activity, thereby regulating downstream signaling pathways (Barrett et al., 2012). In S. sclerotiorum, deletion of SS1G_03171 did not result in an altered phenotype (Jurick et al., 2004), indicating the functional redundancy of the PKA. In the present study, mRNA levels originating from W. cocos PKA Wolco1| 107737, which is homologous to S. cerevisiae TPK2 (NP_015121.1) and S. sclerotiorum SS1G_13577, increased at the sclerotia stage. However, the mRNA level of the other PKA, Wolco1| 115209, which is homologous to S. cerevisiae TPK1 (NP_012371.2) and S. sclerotiorum SS1G_03171, did not change (Supplementary Table S1), indicating that Wolco1| 107737, but not Wolco1| 115209, may play a major role in the sclerotial development of W. cocos. The aurora kinase IPL1 (NP_015115.1) of S. cerevisiae and Fg06959 of F. graminearum are essential; their deletion is lethal (Wang et al., 2011). However, in W. cocos, there was no difference in mRNA levels for this kinase between the mycelium and sclerotia stages (Supplementary Table S1), indicating that W. cocos IPL1 may not be involved in sclerotial formation.

Wolfiporia cocos Wolco1| 71589 and Wolco1| 24527 encode PKs orthologous to S. cerevisiae SCH9 and RIM15, respectively. SCH9 is structurally related to PKA and works with PKA to negatively control RIM15 activity, thereby regulating the response to nutrient starvation or stress in yeast (Roosen et al., 2005). In F. graminearum, Fgsch9 (Fg00472) is involved in both deoxynivalenol (DON) production and growth, and Fgrim15 (Fg01312) plays important roles in DON production and conidiation (Wang et al., 2011). In the current study, W. cocos SCH9 (Wolco1| 71589) demonstrated higher mRNA levels in the sclerotial than the mycelial stage. In contrast, mRNA levels for W. cocos RIM15 (Wolco1| 24527) decreased at the sclerotial stage (Supplementary Table S1).

Several AGC Group PKs, including YPK1/YPK2, PKC1 and SCH9, are phosphorylated and activated by PHK1/PHK2 (Roelants et al., 2004). In S. cerevisiae, YPK1/YPK2 are involved in cell-wall integrity (Roelants et al., 2002), and YPK1 also phosphorylates and down regulates Fpk1 kinase activity (Roelants et al., 2010). In F. graminearum, deletion of Fgfpk1 (Fg04382) results in a reduced growth rate and increased sensitivity to osmotic and oxidative stress (Wang et al., 2011). PKC1 (PKC) targets BCK1 and regulates cell-wall integrity SLT2 MAPK (Reinoso-Martín et al., 2003; Turrà et al., 2014), and PKC1 is an essential gene in both F. graminearum and yeast. CBK1 is essential in wild-type S. cerevisiae strains and is involved in the regulation of polarized growth and cell-wall integrity by regulating the activity of SDP1 (Kurischko et al., 2005; Kuravi et al., 2011). In F. graminearum, the growth rate of CBK1 (Fg01188) mutants decreased by more than 90% and mutant strain formed compact colonies (Wang et al., 2011) (Table 2). In W. cocos, there are two PKs; one of them (Wolco1| 70675) is highly similar to the yeast CBK1 (NP_014238.3, E-value: 0.00E), indicating their potential roles in growth and cell-wall integrity (Table 2).

Table 2.

Potential functions of AGC Group PKs.

| Protein ID | Orthologs | Potential functions |

|---|---|---|

| Wolco1| 115209 | TPK1 | Growth, conidiation, deoxynivalenol (DON) production, ascospore maturation and releasing |

| Wolco1| 107737 | TPK2 | Sclerotial development |

| Wolco1| 88682 | IPL1 | Essential gene |

| Wolco1| 71589 | SCH9 | Response to nutrient starvation or stress, growth and DON production |

| Wolco1| 24527 | RIM15 | DON production and conidiation |

| Wolco1| 29283 | YPK1 | Cell-wall integrity, growth and response to osmotic and oxidative stresses |

| Wolco1| 97232 | YPK2 | Cell-wall integrity |

| Wolco1| 16337 | PKC1 | Cell-wall integrity and essential gene |

| Wolco1| 74908 | CBK1 | Growth, cell-wall integrity and essential gene |

| Wolco1| 70675 | CBK1 | Growth, cell-wall integrity and essential gene |

CAMK Group

The W. cocos CAMK Group has 10 members, eight of which are similar to S. cerevisiae CAMK-like (CAMKL) kinases (Supplementary Table S1; Table 3). Wolco1| 160811 encodes sucrose non-fermenting (SNF1) kinase, and its homolog in S. sclerotiorum and S. cerevisiae are involved in carbon catabolite repression (Sanz, 2003; Vacher et al., 2003). In the plant pathogenic fungus Gibberella zeae, GzSNF1 is important for vegetative growth, sexual reproduction and pathogenesis (Lee et al., 2009). Wolco1| 19611 is most similar to S. cerevisiae KIN1, which regulates exocytosis (Elbert et al., 2005). The homolog of Wolco1| 153019 in F. graminearum Fgkin4 is involved in growth, septum formation, conidiation and sexual reproduction (Wang et al., 2011), and its homolog in S. cerevisiae KIN4 plays a key role in the regulation of the spindle position checkpoint of cells exiting mitosis (Caydasi et al., 2010). Kinase Chk1 functions in DNA damage checkpoint in eukaryotes (Sanchez et al., 1999). In F. graminearum, FgChk1 (Fg01506) is important for DNA damage repair but not necessary for pathogenesis deletion (Wang et al., 2011). Wolco1| 137455 encodes kinase similar to S. sclerotiorum SS1G_06203, and S. cerevisiae RCK2. RCK2 is targeted by HOG1 and links to the pheromone response and hyperosmotic stress via MAPK pathways (Nagiec and Dohlman, 2012).

Table 3.

Potential functions of CAMK Group PKs.

| Protein ID | Orthologs | Potential functions |

|---|---|---|

| Wolco1| 160811 | SNF1 | Carbon catabolite repression, growth, sexual reproduction and pathogenesis |

| Wolco1| 19611 | KIN1 | Exocytosis |

| Wolco1| 153019 | KIN4 | Cells mitosis |

| Wolco1| 92282 | CHK1 | DNA damage repair |

| Wolco1| 137455 | RCK2 | Pheromone response and hyperosmotic stress |

CMGC Group

The W. cocos CMGC Group has 22 members, including the homolog of MAPKs (Supplementary Table S1; Table 4). MAPK cascades and MAPK signaling pathways are known to be involved in many major cell processes in fungi (Turrà et al., 2014). We found three MAPKs in W. cocos. Wolco1| 95503 orthologous to the HOG1-style MAPK in S. sclerotiorum (SS1G_07590) and S. cerevisiae (NP_013214.1) with high similarity. In B. cinerea, the closely related phytopathogen of S. sclerotiorum, the HOG1 ortholog is involved in osmotic stress, oxidative stress, conidia formation and sclerotial development (Segmüller et al., 2007). Wolco1| 107181 is orthologous to the FUS3-style MAPK SMK1 (SS1G_11866) in S. sclerotiorum. Silencing of SMK1 in S. sclerotiorum results in impaired sclerotial formation (Chen et al., 2004). Wolco1| 92114 encodes a kinase similar to S. sclerotiorum SMK3 (SS1G_06203) and S. cerevisiae SLT2-style MAPK (NP_011895.1). Deletion of SMK3 in S. sclerotiorum inhibits the production of sclerotia (Bashi et al., 2010). Deletion of the B. cinerea bmp3 gene encoding a homolog of the yeast MAPK Slt2 also results in the loss of sclerotial formation (Rui and Hahn, 2007).

Table 4.

Potential functions of CMGC Group PKs.

| Protein ID | Orthologs | Potential functions |

|---|---|---|

| Wolco1| 95503 | HOG1 | Osmotic stress, oxidative stress, conidia formation and sclerotial development |

| Wolco1| 107181 | FUS3 | Sclerotial formation |

| Wolco1| 92114 | SLT2 | Sclerotial formation |

| Wolco1| 91184 | CDC28 | Cell division |

| Wolco1| 93694 | CDC28 | Cell division |

| Wolco1| 99718 | CTK1 | Growth, conidiation, sexual reproduction and infection |

| Wolco1| 93172 | PHO85 | Cell division, response to nutrient levels and environmental stresses, cell cycle control and morphogenesis |

| Wolco1| 64270 | YAK1 | Cell proliferation, differentiation, homeostasis, and response to H2O2 |

| Wolco1| 97250 | YAK1 | Cell proliferation, differentiation, homeostasis, and response to H2O2 |

| Wolco1| 75698 | YAK1 | Cell proliferation, differentiation, homeostasis and response to H2O2 |

| Wolco1| 64147 | IME2 | Meiosis initiation and spore formation |

| Wolco1| 159141 | SKY1 | Metabolic signaling, cell-cycle regulation, and chromatin reorganization |

| Wolco1| 92467 | SKY1 | Metabolic signaling, cell-cycle regulation, and chromatin reorganization |

| Wolco1| 95712 | SKY1 | Metabolic signaling, cell-cycle regulation, and chromatin reorganization |

Besides MAPKs, other members of CMGC Group kinases also play important roles in many major cell processes. Wolco1| 91184 and Wolco1| 93694 are the orthologs of yeast CDC28 (NP_009718.3) that regulate cell division in eukaryotes (Malumbres, 2014). Wolco1| 99718 is the ortholog of yeast CTK1(NP_012783.1) that is involved in sexual reproduction in yeast. In F. graminearum, orthologs of CTK1 Fgctk1 are involved in growth, conidiation, sexual reproduction and infection (Wang et al., 2011). W. cocos Wolco1| 93172 encodes PKs orthologous to S. cerevisiae PHO85. Deletion of PHO85 is not lethal in S. cerevisiae, whereas its ortholog is essential in Ustilago maydis and Cryptococcus neoformans (Castillo-Lluva et al., 2007; Virtudazo et al., 2010). In yeast, PHO85 is involved in the regulation of cell division in response to nutrient levels and environmental stresses (Nishizawa, 2015). In Aspergillus nidulans, the homologs of PHO85 play an essential role in cell cycle control and morphogenesis (Dou et al., 2003).

Wolfiporia cocos has three orthologs of YAK1 (Wolco1| 64270, Wolco1| 97250 and Wolco1| 75698). The YAK1 members control cell proliferation, differentiation and homeostasis (Aranda et al., 2011). In F. graminearum, the yak1 mutant is more sensitive to H2O2 than the wild type strain (Wang et al., 2011). Wolco1| 64147 is an ortholog of yeast IME2 (NP_012429.1), which is essential for meiosis initiation (Honigberg, 2004). It also regulates spore formation in response to nutrient levels and cAMP (McDonald et al., 2009). W. cocos has three orthologs of SKY1 (Wolco1| 159141, Wolco1| 92467 and Wolco1| 95712). SKY1 is a serine-arginine PK that is involved in metabolic signaling, cell-cycle regulation and chromatin reorganization (Giannakouros et al., 2011). In F. graminearum, the sky1 mutant was reduced in hyphal branching and produced fewer aerial hyphae (Wang et al., 2011).

STE Group

The W. cocos STE Group contains 11 members (Supplementary Table S1; Table 5). Wolco1| 166770, Wolco1| 43954 and Wolco1| 150169 are the orthologs of yeast STE20, STE11, and STE7, respectively. In the MAPK cascade, MAPKKs (STE7) phosphorylate MAPKs, MAPKKKs (STE11) phosphorylate MAPKKs (STE7) and STE20 is the upstream kinase (Gustin et al., 1998; Chen and Thorner, 2007). Deletion of STE7 and STE11 orthologs in B. cinerea results in reduced growth and virulence (Schamber et al., 2010). The BMP1 MAPK mutant of B. cinerea was unable to form sclerotia and exhibited decreased virulence (Doehlemann et al., 2006). Wolco1| 75024 is orthologous to S. cerevisiae MKK2 MAPKKs, which act in the upstream SLT2-style MAPK pathway and activate this signaling pathway. Wolco1| 144702 is orthologous to S. cerevisiae PBS2 MAPKKs, which act upstream of the HOG1-style MAPK pathway. Wolco1| 135363 is orthologous to S. cerevisiae BCK1, which acts upstream of the SLT2-style MAPK pathway (Turrà et al., 2014). Finally, the CLA4 orthologs in M. grisea and Claviceps purpurea are involved in pathogenicity, mycelial growth and conidial morphology (Li et al., 2004; Rolke and Tudzynski, 2008).

Table 5.

Potential functions of STE Group PKs.

| Protein ID | Orthologs | Potential functions |

|---|---|---|

| Wolco1| 166770 | STE20 | Growth, virulence, and sclerotial formation |

| Wolco1| 43954 | STE11 | Growth, virulence, and sclerotial formation |

| Wolco1| 150169 | STE7 | Growth, virulence, and sclerotial formation |

| Wolco1| 75024 | MKK2 | Regulate MAPK signaling pathway |

| Wolco1| 144702 | PBS2 | Regulate MAPK signaling pathway |

| Wolco1| 135363 | BCK1 | Regulate MAPK signaling pathway |

| Wolco1| 121529 | CLA4 | Pathogenicity, mycelial growth and conidial morphology |

CK Group

There are only two members of the W. cocos CK Group (Supplementary Table S1; Table 6). Wolco1| 22440 is orthologous to S. cerevisiae HRR25. HRR25 is a multifunctional kinase that is involved in autophagy and endocytosis (Tanaka et al., 2014; Peng et al., 2015). The other CK member, Wolco1| 152548, encodes a PK similar to the S. cerevisiae PKs YCK1/YCK2. YCK1/YCK2 are membrane-localized kinases that phosphorylate another membrane anchor protein OPY2 and active the HOG1 signaling pathway in response to high-glucose conditions (Yamamoto et al., 2010).

Table 6.

Potential functions of CK Group PKs.

| Protein ID | Orthologs | Potential functions |

|---|---|---|

| Wolco1| 22440 | HRR25 | Autophagy and endocytosis |

| Wolco1| 152548 | YCK1/YCK2 | Response to high-glucose conditions |

TKL Group

There are 10 members in the W. cocos TKL Group. However, their homologous PKs are not typically found in S. sclerotiorum and S. cerevisiae, indicating that the TKL Group may only exist in higher fungi and eukaryotes.

Other Group

There are 24 PKs members in Other Group that do not cluster into the major groups described above (Supplementary Table S1; Table 7). Wolco1| 159823 and Wolco1| 134885 are orthologous to S. cerevisiae SAT4, which is involved in regulating permeases activity and salt tolerance (Mulet et al., 1999; Pérez-Valle et al., 2010). In F. graminearum, the Fgsat4 mutant was more sensitive to 0.7 M NaCl but more tolerant to 0.7 M KCl (Wang et al., 2011). HRK1 (Wolco1| 142396) contributes to regulating membrane ATPase activity, which is important for glucose uptake (Goossens et al., 2000). Wolco1| 19350 is orthologous to SKS1, which is involved in the response to glucose and hyphal development (Johnson et al., 2014). BUB1 (Wolco1| 144048) and ARK1 (Wolco1| 130299) are involved in the formation of the mitotic spindle pole, cytokinesis, chromosome orientation and separation (Leverson et al., 2002; Storchová et al., 2011). There are six members in this group; however, their homologous PKs are not typically found in S. sclerotiorum and S. cerevisiae.

Table 7.

Potential functions of other group PKs.

| Protein ID | Orthologs | Potential functions |

|---|---|---|

| Wolco1| 159823 | SAT4 | Permeases activity and salt tolerance |

| Wolco1| 134885 | SAT4 | Permeases activity and salt tolerance |

| Wolco1| 142396 | HRK1 | Regulation of membrane ATPase activity |

| Wolco1| 19350 | SKS1 | Response to glucose and hyphal development |

| Wolco1| 144048 | BUB1 | Regulate the formation of mitotic spindle pole, cytokinesis, chromosome orientation and separation |

| Wolco1| 130299 | ARK1 | Regulate the formation of mitotic spindle pole, cytokinesis, chromosome orientation and separation |

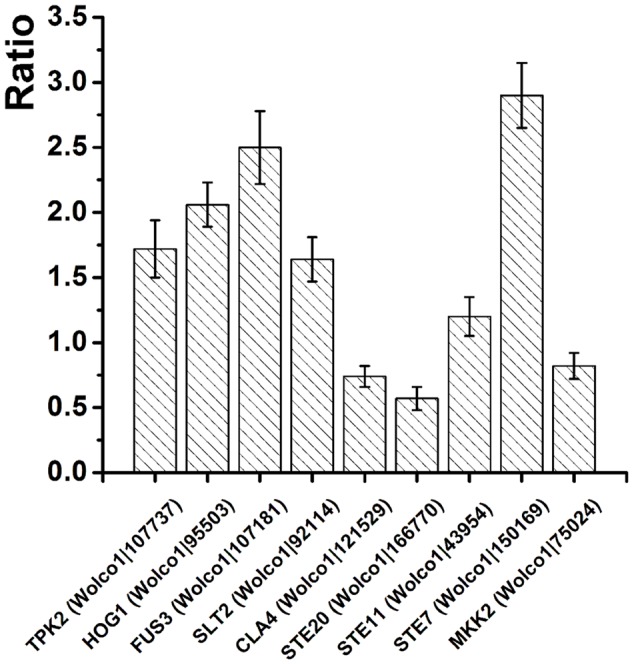

qRT-PCR of mRNA from Genes Involved in Sclerotia Formation

Nine W. cocos PKs whose orthologs in other fungi are involved in sclerotial formation were chosen for a validation procedure of their RNA levels were determined via qRT-PCR. The results revealed that mRNAs from genes encoding TPK2 (Wolco1| 107737), HOG1 (Wolco1| 95503), FUS3 (Wolco1| 107181), SLT2 (Wolco1| 92114), STE11 (Wolco1| 43954) and STE7 (Wolco1| 150169) were present in higher amounts during the sclerotial stage; CLA4 (Wolco1| 121529), STE20 (Wolco1| 166770), and MKK2 (Wolco1| 75024) mRNAs were present in lower amounts (Figure 2). These results are consistent with the de novo transcriptome sequencing data (Supplementary Table S1), indicating that W. cocos PKs regulate sclerotial formation in both positive and negative ways.

FIGURE 2.

qRT-PCR validation of sclerotia-formation associated genes. The relative expression of target genes in mycelium stage was set as level 1. Expression levels of W. cocos alpha-tubulin gene was used to normalize different samples. Bars represent means and standard deviations (three replications). Y-axis represent the ratio of genes expression in sclerotial stage to mycelium stage.

Discussion

Since shortages in pine wood resources currently limit the commercial production of W. cocos sclerotia, it is important to find ways to improve the sclerotial yield and their content of pharmacologically active components. We hypothesize that better knowledge of the kinome of the fungus can point to ways of achieving this goal.

In S. sclerotiorum, sclerotial formation is dependent on mycelial differentiation and the response to stress, nutrient and environmental changes via PK signaling pathways (Erental et al., 2008). Silencing of the FUS3-style MAPKs gene SMK1 results in impaired sclerotial formation (Chen et al., 2004). In W. cocos, Wolco1| 107181 is orthologous to SMK1, and its expression level is upregulated at the sclerotial stage (Figure 2; Supplementary Table S1). Besides SMK1, Wolco1| 92114, which is orthologous to SLT2-style MAPKs, is also upregulated in the sclerotial stage (Figure 2; Supplementary Table S1), indicating that MAPKs also potentially positively regulate sclerotial formation in W. cocos. In B. cinerea, deletion of the bmp3 gene encoding a homolog of the yeast SLT2-style MAPKs results in the loss of sclerotial formation (Rui and Hahn, 2007). Additionally, like FUS3-style and SLT2-style MAPKs, the HOG1-type MAPK BcSAK1 is also involved in sclerotial development (Segmüller et al., 2007), and the homolog of HOG1-type MAPK in W. cocos is also upregulated (Figure 2; Supplementary Table S1), suggesting that MAPKs play significant roles in the sclerotial formation of multiple fungi. In addition, sclerotial development of S. sclerotiorum is also associated with the cAMP-PKA signaling pathway in a complicated way (Rollins and Dickman, 1998; Harel et al., 2005; Jurick and Rollins, 2007). W. cocos contains two genes, Wolco1| 115209 and Wolco1| 107737, that encode the catalytic subunits of PKA, similar to S. sclerotiorum SS1G_03171 and SS1G_13577, respectively. In S. sclerotiorum, deletion of SS1G_03171 does not result in an altered phenotype (Jurick et al., 2004). In the current study, the expression level of W. cocos Wolco1| 107737 was upregulated at the sclerotia stage, and the expression level of the other PKA Wolco1| 115209 did not change significantly (Supplementary Table S1), indicating that Wolco1| 107737, but not Wolco1| 115209, potentially plays the major role in sclerotial development in W. cocos.

Although sclerotial development has recently been studied (Wu et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2016), the mechanisms of sclerotial development and W. cocos-pine wood interactions remain largely unknown. This paucity of knowledge is also the case particularly for sclerotogenesis, which is regulated via PK signaling pathways. In addition, since W. cocos is only able to form sclerotia after colonization of pine wood, we hypothesize that some components from pine woods may induce mycelial differentiation and sclerotial development via PK signaling pathways. Since multiple PK genes whose homologs regulate sclerotial formation in other fungi were upregulated in mature sclerotia of W. cocos, it is likely that sclerotogenesis and sclerotial development occur in response to stress and/or nutrient and environmental change via PK signaling pathways.

Because PK pathways integrate multiple external and internal signals to co-regulate the key processes of the fungal life cycle, such as growth, infection, nutrient or stress responses, metabolism and sclerotial development (Erental et al., 2008; Turrà et al., 2014), over-expression of key PK genes or interference in their expression will change physiological processes and traits. In Ganoderma lucidum, another traditional Chinese medicinal mushroom, over-expression of the 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase gene by using Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation method led to a two fold increase in ganoderic acid content, increased accumulation of intermediates and the up-regulation of downstream genes (Xu et al., 2012), indicating that genetic engineering is an efficient approach to manipulate the economic traits of fungi. Furthermore, an efficient and stable genetic transformation system for W. cocos has been developed (Sun et al., 2015), and the genes and pathways involved in triterpenoids (the main active compound in W. cocos) biosynthesis are known (Shu et al., 2013). Based on our analysis, the orthologs of TPK2, HOG1, FUS3, SLT2, STE11, and STE7 in other fungi play significant roles in sclerotial development, and they are upregulated during the sclerotial stage (Figure 2; Supplementary Table S1), indicating that these PKs potentially positively regulate sclerotial formation in W. cocos. Therefore, we have selected these six PKs as the target genes for eventual over-expression in W. cocos by genetic engineering to improve the sclerotial yield.

In summary, we have identified and discussed the potential roles of W. cocos PK genes in growth, sclerotial developmental, morphological changes and environmental stress responses. Characterization of these PK genes will help illuminate the underlying mechanisms of sclerotogenesis and improve the sclerotial yield.

Conclusion

This study firstly contributes to an understanding of putative functions of PKs in W. cocos sclerotial development and other important physiological processes. And it also provides a valuable data for illuminating the mechanisms of W. cocos sclerotial development and promoting commercial cultivation of W. cocos sclerotia.

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: WZ and WW. Performed the experiments: WW, SS, and WZ. Analyzed the transcription data: WW, WZ, and YX. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: WW, SS, WZ, YX, and FP. Wrote the paper: WZ and WW. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The research was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31501587), Scientific Research Foundation Granted From Wuhan Polytechnic University and Hubei Provincial Department of Education Scientific Research Plan Guidance Project (B2016297). We thank anonymous reviewers for their kind suggestions.

Footnotes

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2016.01495

Protein kinase genes in Wolfiporia cocos.

References

- Aranda S., Laguna A., de la Luna S. (2011). DYRK family of protein kinases: evolutionary relationships, biochemical properties, and functional roles. FASEB. J. 25 449–462. 10.1096/fj.10-165837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett L., Orlova M., Maziarz M., Kuchin S. (2012). Protein kinase A contributes to the negative control of Snf1 protein kinase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eukaryotic Cell 11 119–128. 10.1128/EC.05061-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashi Z. D., Khachatourians G. G., Hegedus D. D. (2010). Isolation of fungal homokaryotic lines from heterokaryotic transformants by sonic disruption of mycelia. Biotechniques 48 351–354. 10.2144/000113243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo-Lluva S., Alvarez-Tabares I., Weber I., Steinberg G., Perez-Martin J. (2007). Sustained cell polarity and virulence in the phytopathogenic fungus Ustilago maydis depends on an essential cyclin-dependent kinase from the Cdk5/Pho85 family. J. Cell Sci. 120 1584–1595. 10.1242/jcs.005314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caydasi A. K., Kurtulmus B., Orrico M. I., Hofmann A., Ibrahim B., Pereira G. (2010). Elm1 kinase activates the spindle position checkpoint kinase Kin4. J. Cell Biol. 190 975–989. 10.1083/jcb.201006151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., Harel A., Gorovoits R., Yarden O., Dickman M. B. (2004). MAPK regulation of sclerotial development in Sclerotinia sclerotiorum is linked with pH and cAMP sensing. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact 17 404–413. 10.1094/MPMI.2004.17.4.404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R. E., Thorner J. (2007). Function and regulation in MAPK signaling pathways. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1773 1311–1340. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2007.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P. (2000). The regulation of protein function by multisite phosphorylation-a 25 year update. Trends. Bioch. Sci. 25 596–601. 10.1016/S0968-0004(00)01712-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Y. C., Yang Z. L., Cui B. K., Yu C. J., Zhou L. W. (2009). Species diversity and utilization of medicinal mushrooms and fungi in China. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 11 287–302. 10.1615/IntJMedMushr.v11.i3.80 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doehlemann G., Berndt P., Hahn M. (2006). Different signalling pathways involving a Gα protein, cAMP and a MAP kinase control germination of Botrytis cinerea conidia. Mol. Microbiol. 59 821–835. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04991.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dou X. W., Wu D. L., An W. L., Davies J., Hashmi S. B., Ukil L., et al. (2003). The PHOA and PHOB cyclin-dependent kinases perform an essential function in Aspergillus nidulans. Genetics 165 1105–1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbert M., Rossi G., Brennwald P. (2005). The yeast par-1 homologs kin1 and kin2 show genetic and physical interactions with components of the exocytic machinery. Mol. Biol. Cell 16 532–549. 10.1091/mbc.E04-07-0549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erental A., Dickman M. B., Yarden O. (2008). Sclerotial development in Sclerotinia sclerotiorum: awakening molecular analysis of a ‘Dormant’ structure. Fungal. Biol. Rev. 22 6–16. 10.1016/j.fbr.2007.10.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Esteban C. I. (2009). Medicinal interest of Poria cocos (= Wolfiporia extensa). Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 26 103–107. 10.1016/S1130-1406(09)70019-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y. L., Lei P., Tian T., Yin L., Chen D. Q., Chen H., et al. (2013). Diuretic activity of some fractions of the epidermis of Poria cocos. J. Ethnopharmacol. 150 1114–1118. 10.1016/j.jep.2013.10.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y., Yan H., Jin R., Lei P. (2016). Antiepileptic activity of total triterpenes isolated from Poria cocos is mediated by suppression of aspartic and glutamic acids in the brain. Pharm. Biol. 9 1–8. 10.3109/13880209.2016.1168853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannakouros T., Nikolakaki E., Mylonis I., Georgatsou E. (2011). Serine–arginine protein kinases: a small protein kinase family with a large cellular presence. FEBS. J. 278 570–586. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07987.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goossens A., de La Fuente N., Forment J., Serrano R., Portillo F. (2000). Regulation of yeast H(+)-ATPase by protein kinases belonging to a family dedicated to activation of plasma membrane transporters. Mol. Cell Biol. 20 7654–7661. 10.1128/MCB.20.20.7654-7661.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustin M. C., Alertyn J., Alexander M., Davenport K. (1998). MAP kinase pathways in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62 1264–1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harel A., Rorovitis R., Yarden O. (2005). Changes in protein kinase A activity accompany sclerotial development in Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Phytopathology 95 397–404. 10.1094/PHYTO-95-0397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegedus D. D., Gerbrandt K., Coutu C. (2016). The eukaryotic protein kinase superfamily of the necrotrophic fungal plant pathogen, Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Mol. Plant Pathol. 17 634–647. 10.1111/mpp.12321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honigberg S. M. (2004). Ime2p and Cdc28p: co-pilots driving meiotic development. J. Cell. Biochem. 92 1025–1033. 10.1002/jcb.20131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu S., Zhou X., Gu X., Cao S., Wang C., Xu J. R. (2014). The cAMP-PKA pathway regulates growth, sexual and asexual differentiation, and pathogenesis in Fusarium graminearum. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 27 557–566. 10.1094/MPMI-10-13-0306-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter T., Plowman G. D. (1997). The protein kinases of budding yeast: six score and more. Trends Biochem. Sci. 22 18–22. 10.1016/S0968-0004(96)10068-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacinto E., Lorberg A. (2008). TOR regulation of AGC kinases in yeast and mammals. Biochem. J. 418 19–37. 10.1042/BJ20071518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson C., Kweon H. K., Sheidy D., Shively C. A., Mellacheruvu D., Nesvizhskii A. I., et al. (2014). The yeast Sks1p kinase signaling network regulates pseudohyphal growth and glucose response. PLoS Genet. 10:e1004183 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurick W. M., Dickman M. B., Rollins J. A. (2004). Characterization and functional analysis of a cAMP-dependent protein kinase A catalytic subunit gene (pka1) in Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 64 155–163. 10.1016/j.pmpp.2004.07.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jurick W. M., Rollins J. A. (2007). Deletion of the adenylate cyclase (sac1) gene affects multiple developmental pathways and pathogenicity in Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Fungal. Genet. Biol. 44 521–530. 10.1016/j.fgb.2006.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobira S., Atsumi T., Kakiuchi N., Mikage M. (2012). Difference in cultivation characteristics and genetic polymorphism between Chinese and Japanese strains of Wolfiporia cocos Ryvarden et Gilbertson (Poria cocos Wolf). J. Nat. Med. 66 493–499. 10.1007/s11418-011-0612-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosti I., Mandel-Gutfreund Y., Glaser F., Horwitz B. A. (2010). Comparative analysis of fungal protein kinases and associated domains. BMC Genomics 11:133 10.1186/1471-2164-11-133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo T., Terabayashi S., Takeda S., Sasaki H., Aburada M., Miyamoto K. (2006). Indoor cultivation and cultural characteristics of Wolfiporia cocos sclerotia using mushroom culture bottles. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 29 1191–1196. 10.1248/bpb.29.1191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuravi V. K., Kurischko C., Puri M., Luca F. C. (2011). Cbk1 kinase and Bck2 control MAP kinase activation and inactivation during heat shock. Mol. Biol. Cell 22 4892–4907. 10.1091/mbc.E11-04-0371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurischko C., Weiss G., Ottey N., Luca F. C. (2005). A role for the Saccharomyces cerevisiae regulation of Ace2 and polarized morphogenesis signaling network in cell integrity. Genetics 171 443–455. 10.1534/genetics.105.042101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. H., Lee J., Lee S., Park E. H., Kim K. W., Kim M. D., et al. (2009). GzSNF1 is required for normal sexual and asexual development in the ascomycete Gibberella zeae. Eukaryot. Cell 8 116–127. 10.1128/EC.00176-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leverson J. D., Huang H.-K., Forsburg S. L., Hunter T. (2002). The Schizosaccharomyces pombe Aurora-related Kinase Ark1 interacts with the inner centromere protein Pic1 and mediates chromosome segregation and cytokinesis. Mol. Biol. Cell 13 1132–1143. 10.1091/mbc.01-07-0330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Xue C., Bruno K., Nishimura M., Xu J. R. (2004). Two PAK kinase genes, CHM1 and MST20, have distinct functions in Magnaporthe grisea. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 17 547–556. 10.1094/MPMI.2004.17.5.547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Z. H., Xiao Z. B., Zhu D. N., Yan Y. Q., Yu B. Y., Wang Q. J. (2009). Aqueous extracts of FBD, a Chinese herb formula composed of Poria cocos, Atractylodes macrocephala, and Angelica sinensis reverse scopolamine induced memory deficit in ICR mice. Pharm. Biol. 47 396–401. 10.1080/13880200902758816 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malumbres M. (2014). Cyclin-dependent kinases. Genome Biol. 15 122 10.1186/gb4184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald C. M., Wagner M., Dunham M. J., Shin M. E., Ahmed N. T., Winter E. (2009). The Ras/cAMP pathway and the CDK-like kinase Ime2 regulate the MAPK Smk1 and spore morphogenesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 181 511–523. 10.1534/genetics.108.098434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda-Saavedra D., Barton G. J. (2007). Classification and functional annotation of eukaryotic protein kinases. Proteins Struct. Func. Bioinformat. 68 893–914. 10.1002/prot.21444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortazavi A., Williams B. A., McCue K., Schaeffer L., Wold B. (2008). Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA–Seq. Nat. Methods 5 621–628. 10.1038/nmeth.1226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulet J. M., Leube M. P., Kron S. J., Rios G., Fink G. R., Serrano R. (1999). A novel mechanism of ion homeostasis and salt tolerance in yeast: the Hal4 and Hal5 protein kinases modulate the Trk1-Trk2 potassium transporter. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19 3328–3337. 10.1128/MCB.19.5.3328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagiec M. J., Dohlman H. G. (2012). Checkpoints in a yeast differentiation pathway coordinate signaling during hyperosmotic stress. PLoS. Genet. 8:e1002437 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishizawa M. (2015). The regulators of yeast PHO system participate in the transcriptional regulation of G1 cyclin under alkaline stress conditions. Yeast 32 367–378. 10.1002/yea.3064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Y., Grassart A., Lu R., Wong C. C., Yates J., Barnes G., et al. (2015). Casein kinase 1 promotes initiation of clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Dev. Cell 32 231–240. 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.11.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Valle J., Rothe J., Primo C., Martínez-Pastor M., Ariño J., Pascual-Ahuir A., et al. (2010). Hal4 and Hal5 protein kinases are required for general control of carbon and nitrogen uptake and metabolism. Eukaryot. Cell 9 1881–1890. 10.1128/EC.00184-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinoso-Martín C., Schüller C., Schuetzer-Muehlbauer M., Kuchler K. (2003). The yeast protein kinase C cell integrity pathway mediates tolerance to the antifungal drug caspofungin through activation of Slt2p mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling. Eukaryot. Cell 2 1200–1210. 10.1128/EC.2.6.1200-1210.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rios J. L. (2011). Chemical constituents and pharmacological properties of Poria cocos. Planta Med. 77 681–691. 10.1055/s-0030-1270823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roelants F. M., Baltz A. G., Trott A. E., Fereres S., Thorner J. (2010). A protein kinase network regulates the function of aminophospholipid flippases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 34–39. 10.1073/pnas.0912497106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roelants F. M., Torrance P. D., Bezman N., Thorner J. (2002). Pkh1 and Pkh2 differentially phosphorylate and activate Ypk1 and Ykr2 and define protein kinase modules required for maintenance of cell wall integrity. Mol. Biol. Cell. 13 3005–3028. 10.1091/mbc.E02-04-0201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roelants F. M., Torrance P. D., Thorner J. (2004). Differential roles of PDK1- and PDK2-phosphorylation sites in the yeast AGC kinases Ypk1, Pkc1 and Sch9. Microbiology 150 3289–3304. 10.1099/mic.0.27286-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolke Y., Tudzynski P. (2008). The small GTPase Rac and the p21-activated kinase Cla4 in Claviceps purpurea: interaction and impact on polarity, development and pathogenicity. Mol. Microbiol. 68 405–423. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06159.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollins J. A., Dickman M. B. (1998). Increase in endogenous and exogenous cyclic AMP levels inhibits sclerotial development in Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64 2539–2544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roosen J., Engelen K., Marchal K., Mathys J., Griffioen G., Cameroni E., et al. (2005). PKA and Sch9 control a molecular switch important for the proper adaptation to nutrient availability. Mol. Microbiol. 55 862–880. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04429.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rui O., Hahn M. (2007). The Slt2-type MAP kinase Bmp3 of Botrytis cinerea is required for normal saprotrophic growth, conidiation, plant surface sensing and host tissue colonization. Mol. Plant Pathol. 8 173–184. 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2007.00383.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez Y., Bachant J., Wang H., Hu F. H., Liu D., Tetzlaff M., et al. (1999). Control of the DNA damage checkpoint by Chk1 and Rad53 protein kinases through distinct mechanisms. Science 286 1166–1171. 10.1126/science.286.5442.1166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz P. (2003). Snf1 protein kinase: a key player in the response to cellular stress in yeast. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 31 178–181. 10.1042/bst0310178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schamber A., Leroch M., Diwo J., Mendgen K., Hahn M. (2010). The role of mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase signalling components and the Ste12 transcription factor in germination and pathogenicity of Botrytis cinerea. Mol. Plant Pathol. 11 105–119. 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2009.00579.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segmüller N., Ellendorf U., Tudzynski B., Tudzynski P. (2007). BcSAK1, a stress-activated MAP kinase is involved in vegetative differentiation and pathogenicity in Botrytis cinerea. Eukaryot. Cell 6 211–221. 10.1128/EC.00153-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu S., Chen B., Zhou M., Zhao X., Xia H., Wang M., et al. (2013). De novo sequencing and transcriptome analysis of Wolfiporia cocos to reveal genes related to biosynthesis of triterpenoids. PLoS ONE 8:e71350 10.1371/journal.pone.0071350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storchová Z., Becker J. S., Talarek N., Kögelsberger S., Pellman D. (2011). Bub1, Sgo1, and Mps1 mediate a distinct pathway for chromosome biorientation in budding yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell. 22 1473–1485. 10.1091/mbc.E10-08-0673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Q., Wei W., Zhao J., Song J., Peng F., Zhang S., et al. (2015). An efficient PEG/CaCl2-mediated transformation approach for the medicinal fungus Wolfiporia cocos. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 25 1528–1531. 10.4014/jmb.1501.01053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka C., Tan L. J., Mochida K., Kirisako H., Koizumi M., Asai E., et al. (2014). Hrr25 triggers selective autophagy-related pathways by phosphorylating receptor proteins. J. Cell. Biol. 207 91–105. 10.1083/jcb.201402128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang J., Nie J., Li D., Zhu W., Zhang S., Ma F., et al. (2014). Characterization and antioxidant activities of degraded polysaccharides from Poria cocos sclerotium. Carbohydr. Polym. 105 121–126. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2014.01.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrà D., Segorbe D., Di Pietro A. (2014). Protein kinases in plant-pathogenic fungi: conserved regulators of infection. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 52 267–288. 10.1146/annurev-phyto-102313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vacher S., Cotton R., Fevre M. (2003). Characterization of a SNF1 homologue from the phytopathogenic fungus Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Gene 310 113–121. 10.1016/S0378-1119(03)00525-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virtudazo E. V., Kawamoto S., Ohkusu M., Aoki S., Sipiczki M., Takeo K. (2010). The single Cdk1-G1 cyclin of Cryptococcus neoformans is not essential for cell cycle progression, but plays important roles in the proper commitment to DNA synthesis and bud emergence in this yeast. FEMS. Yeast Res. 10 605–618. 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2010.00633.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Zhang S., Hou R., Zhao Z., Zheng Q., Xu Q., et al. (2011). Functional analysis of the kinome of the wheat scab fungus Fusarium graminearum. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002460 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Mukerabigwi J. F., Zhang Y., Han L., Jiayinaguli T., Wang Q., et al. (2015a). In vivo immunological activity of carboxymethylated-sulfated (1→3)-β-d-glucan from sclerotium of Poria cocos. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 79 511–517. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.05.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Dong H., Yan R., Li H., Li P., Chen P., et al. (2015b). Comparative study of lanostane-type triterpene acids in different parts of Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf by UHPLC–Fourier transform MS and UHPLC-triple quadruple MS. J. Pharmaceut. Biomed. 102 203–214. 10.1016/j.jpba.2014.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K. Q., Fu J., Shu W., Fang H., Deng F. (2002). Review of Chinese traditional medicinal fungus: Wolfiporia cocos. Res. Inf. Tradit. Chin. Med. 4 16–17. 10.1016/j.jep.2013.03.027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K. Q., Yin X. R., Huang H., Fu J., Feng H. G., Wang Q., et al. (2012). Production status and industrialization development countermeasures of Poria in Hubei Province. Mod. Chin. Med. 14 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Feng Z., Wang X., Wang X., Zhang X. (2010). DEGseq: an R package for identifying differentially expressed genes from RNA-seq data. Bioinformatics 26 136–138. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. Z., Zhang J., Zhao Y. L., Li T., Shen T., Li J. Q., et al. (2013). Mycology, cultivation, traditional uses, phytochemistry and pharmacology of Wolfiporia cocos (Schwein.) Ryvarden et Gilb.: a review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 147 265–276. 10.1016/j.jep.2013.03.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y., Zhu W., Wei W., Zhao X., Wang Q., Zeng W., et al. (2016). De novo assembly and transcriptome analysis of sclerotial development in Wolfiporia cocos. Gene 588 149–155. 10.1016/j.gene.2016.05.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong J., Lin F. C., Wang K. Q., Su W., Fu J. (2006). Studies on basic biological characters of Wolfiporia cocos. Mycosystema 25 446–453. [Google Scholar]

- Xu J. W., Xu Y. N., Zhong J. J. (2012). Enhancement of ganoderic acid accumulation by overexpression of an N-terminally truncated 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase gene in the basidiomycete Ganoderma lucidum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78 7968–7976. 10.1128/AEM.01263-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z., Tang W., Xiong B., Wang K., Bian Y. (2014). Effect of revulsive cultivation on the yield and quality of newly formed sclerotia in medicinal Wolfiporia cocos. J. Nat. Med. 68 576–585. 10.1007/s11418-014-0842-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto K., Tatebayashi K., Tanaka K., Saito H. (2010). Dynamic control of yeast MAP kinase network by induced association and dissociation between the Ste50 scaffold and the Opy2 membrane anchor. Mol. Cell 40 87–98. 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S., Hu B., Wei W., Xiong Y., Zhu W., Peng F., et al. (2016). De novo analysis of Wolfiporia cocos transcriptome to reveal the differentially expressed carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes) genes during the early stage of sclerotial growth. Front. Microbiol. 7:83 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y. Y., Feng Y. L., Bai X., Tan X. J., Lin R. C., Mei Q. (2013). Ultra performance liquid chromatography-based metabonomic study of therapeutic effect of the surface layer of Poria cocos on adenine-induced chronic kidney disease provides new insight into anti-fibrosis mechanism. PLoS ONE 8:e59617 10.1371/journal.pone.0059617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Protein kinase genes in Wolfiporia cocos.