Abstract

Objectives

The British HIV Association's (BHIVA) testing guidelines recommend men who have sex with men (MSM) test annually or more frequently if ongoing risk is present. We identify which groups of MSM in England are less likely to have tested for HIV and their preferences for future tests by testing model, in order to inform health promotion programmes.

Methods

Data come from the Gay Men's Sex Survey 2014, a cross-sectional survey of MSM, aged 16 years or older and living in the UK. Only men who did not have diagnosed HIV and were living in England were included in this analysis. We used logistic regression models to understand how social determinants of health were associated with not testing for HIV in the past 12 months, and never having tested. We then cross-tabulated preferred testing location by demographic characteristics.

Results

Younger men, older men and men who were not gay identified were least likely to have tested for HIV. Higher educational attainment, migrancy, Black ethnicity and being at higher of risk were associated with greater levels of HIV testing. Men who were less likely to have tested for HIV preferred a wider range of options for future HIV testing.

Conclusions

If the BHIVA's HIV testing policy of 2008 was used to guide testing priorities among MSM focus would be on increasing the rate of annual testing among MSM at less risk of HIV (ie, younger men, older men and non-gay identified MSM). Instead the promotion of more frequent testing among the groups most at risk of infection should be prioritised in order to reduce the time between infection and diagnosis.

Keywords: HIV testing, MSM, England

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study identifies which groups of men who have sex with men (MSM) in England are less likely to have tested for HIV ever and in the preceding 12 months and their service preferences for future tests.

This study provides a robust critique of The British HIV Association's (BHIVA) 2008 HIV testing guidelines which recommend annual or more frequent testing for all MSM.

While the gay identified men in our study are broadly representative of probability-based samples of MSM in the UK, there is a greater divergence in the non-gay identified MSM, which may lead us to overestimate testing among these men.

HIV self-testing was not available at the time of this research was conducted, and HIV self-sampling was often advertised as self-testing in England. Participants may therefore have been confused by the difference between these options.

Background

Both globally and in the UK, HIV prevention is moving towards a test and treat model. This approach evolved from the recognition that the majority of new HIV infections among men who have sex with men (MSM) are passed from those who are unaware of their infection, and that treating HIV-positive individuals early drastically reduces their infectivity.1 2 Sexual health promotion now has a major focus on reducing the time between infection and diagnosis through increasing rates of testing, as well as providing earlier HIV treatment to those found to be positive.1 2 Essentially this approach emphasises reducing the amount of undiagnosed HIV within the population in order to reduce community viral load (and therefore onward transmission) while also preventing illness in individuals who have HIV.3 The British HIV Association (BHIVA) and Public Health England (PHE) now recommend that all MSM in the UK test for HIV at least annually and ‘and every 3 months if having unprotected sex with new or casual partners’.4 While rates of HIV testing among this group have increased dramatically in the last decade, PHE estimates that currently 14% of UK MSM with HIV infection have yet to be diagnosed.4

Factors mediating MSM's decisions to test are complex and varied. Significant barriers to encouraging MSM to test for HIV exist, particularly in relation to psychosocial needs and negative emotional responses to testing.5 In the UK, policymakers have focused on creating demand for testing services through demand side interventions including policy and health promotion interventions addressing some of these factors, and by encouraging regular testing through national campaigns.6 Efforts to boost supply have also been central in attempts to increase the rate and frequency of testing among MSM. Models of delivery for HIV testing have also evolved with a key aim of reducing barriers to testing among most at-risk populations (for a comprehensive discussion on barriers to HIV testing, see ref. 7). While hospital-based outpatient HIV testing remains the norm, public health provision has focused increasingly on providing a wider range of settings for HIV testing. Initial expansion focused on opt-out as opposed to opt-in protocols in clinics, and providing HIV testing services within the community8 9 and, more recently, providing opportunities for self-administered testing methods including self-sampling and self-testing.10

It is unclear however which groups of MSM are most likely to access HIV testing and why. In addition, it is not known which groups favour which types of testing and what mix of testing services might achieve higher rates of HIV testing.

In this paper, we present analyses of the Gay Men's Sex Survey (GMSS) 2014, the 17th in a series of national sexual health needs assessments for gay, bisexual and other MSM. Our aim is to identify which groups of MSM in England are less likely to have tested for HIV and their preferred model for future tests. We do this by identifying demographic and behavioural characteristics associated with never having tested for HIV and not testing in the preceding 12 months, and by identifying preferences for future HIV testing among respondents based on demographic and behavioural characteristics. We focus on English MSM only as England has a separate health infrastructure to the rest of the UK leading to a restriction of interventions by region.11

Methods

GMSS received a favourable ethical opinion from the Observational Research Ethics Committee at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (reference number 7658) on 17 June 2014.

The survey recruited men who reported attraction to other men who were aged 16 or older and living in England between August and November of 2014. Recruitment occurred through advertising on internet dating services (websites and geolocation social networking apps), social media and, to a lesser extent, voluntary sector organisations. The survey could only be completed online in English.

Demographic and behavioural characteristics treated as independent variables included age, sexual identity, ethnicity, highest educational qualification, migrancy and having had two or more non-steady sexual partners with whom a condom was not used for anal sex (2+NSSPNC). Age was recorded as a continuous variable and then recoded into 10-year bands beginning at under 20 and ending at 60 or over. Sexual identity was categorised as gay or homosexual, bisexual, straight or heterosexual, queer, ‘any other term’, and ‘I don't usually use a term’. Ethnicity was recoded from standard UK ethnicity codes into four categories to avoid issues with having many categories with small numbers of observations: respondents were classified as Black, White, Asian and other. Responses to highest educational qualification were stratified into ‘high’, ‘medium’ and ‘low’. Those with no qualifications or those with no post-16 education were classed as having low educational qualifications, while those educated to degree level were classified as having high educational qualification. The remaining men were classified as having a medium level of education (including men with A levels or equivalent and the majority of those with vocational or trade qualifications). A migrancy variable was created using responses to a question asking if the respondent was born in the UK. Those who indicated that they were not were classed as migrants. We created the variable 2+NSSPNC by stacking a variable indicating any casual partners into one where men identified the number of non-steady sex partners they had condomless anal sex with.

Respondents were asked if they had ever received an HIV test result. The options were ‘no, I have never received and HIV test result’, ‘yes, I've tested positive’ and ‘yes, my last test was negative’. Respondents that had ever received an HIV test result were asked when they received their last negative HIV test, divided into time bands ranging from within the past 24 hours to more than 5 years ago. These data were recoded to ‘tested for HIV in the last year’ and ‘not tested for HIV in the last year’. For our variable reporting having tested in the preceding 6 months, the data were recoded as appropriate following the same method.

Respondents were also asked where they would most like to test for HIV in the future. This dependent variable was recoded from initial values into general practitioner/family doctor, a doctor in a private practice, at a hospital or genitourinary medicine (GUM) clinic, at a community HIV testing service (including in a bar/pub, club or sauna, or mobile medical unit), self-sampling kit (taking own sample and sending off for result), self-testing kit (taking a sample and finding out a result on the spot), other and ‘I will not want to test for HIV in the future’.

Analysis

First, we examined associations between demographic characteristics and HIV testing history. We used logistic regression models to understand how demographic and behavioural variables were associated with the dependent variables of not having tested for HIV in the past 12 months and never having tested for HIV. We regressed both of our dependent variables on each of age, sexual orientation, ethnicity, highest educational attainment, migrancy and 2+NSSPNC. We chose reference categories with the aim of understanding key equity dimensions of access to healthcare, particularly in relation to men with lower educational qualifications and barriers to accessibility which may vary across cultural groups.4 7 Our risk variable was chosen as we theorised that having two of more non-steady sexual partners with whom condoms are not used for anal sex was indicative of likelihood of ongoing risk. After entering each demographic characteristic into a bivariate logistic regression, we included all characteristics in one model for each dependent variable using block entry. For each logistic regression model, we report ORs (unadjusted or adjusted) and Wald tests for overall model significance.

Second, we calculated χ2 tests on 2+NSSPNC and testing in the preceding 6 months.

Third, we calculated χ2 tests on preferred testing location by comparing MSM who had last tested negative with MSM who had never received an HIV test.

Fourth, we cross-tabulated preferred testing location by demographic characteristics. We did not use inferential testing because of the multiplicity of categories.

Missing data across all variables was <5% of observations. We decided this level of missing data was acceptable for a community-based cross-sectional survey and did not make attempts to use corrective statistical mechanisms.

All analyses were undertaken in Statacorp Stata V.13.

Results

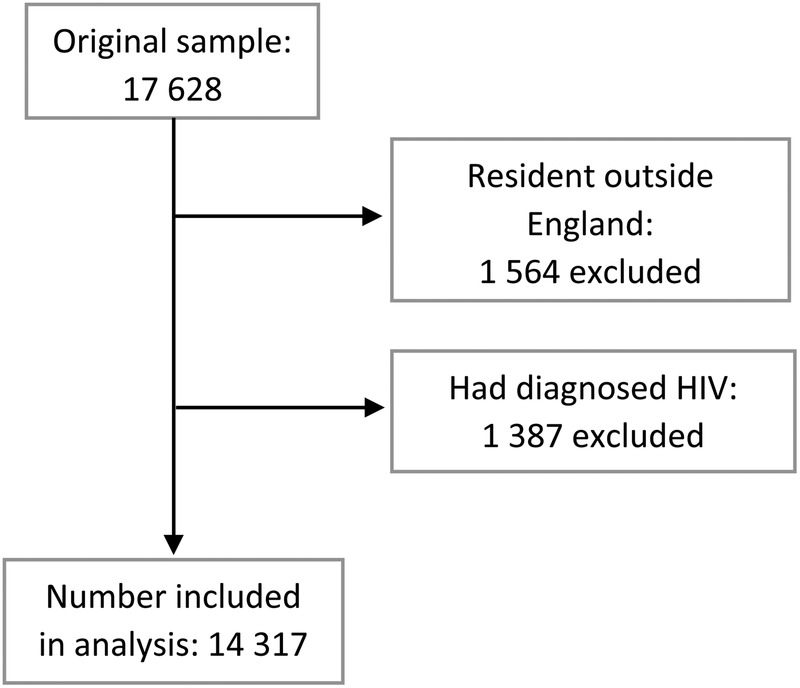

The survey recruited 15 704 MSM in England of whom 14 317 (86%) had not been diagnosed with HIV. Of these, 14 235 (99%) had indicated whether or not they had received a previous HIV-negative test result and data on whether or not they had tested in the past 12 months were available for 14 194 (99%) men. See figure 1 for exclusion flow chart.

Figure 1.

Participant exclusion flow chart.

Having never tested

In the sample of men who had not received a positive HIV test, 73.9% had received a negative HIV test, while 26.1% had never tested for HIV.

Findings from univariate models are in table 1. Compared with men in their 20s, men below the age of 20 were more likely to have never tested for HIV whereas men in their 30s and 40s were significantly less likely to have never tested for HIV. Men in their 50s were not significantly different from men in their 20s, whereas men in their 60s were more likely to not have received an HIV test. Men who identified as queer were not statistically different from men who identified as gay in odds of never having tested for HIV, but compared with men who identified as gay, men in every other sexual orientation category were significantly more likely to have never received an HIV test. White men were most likely to not have received an HIV test, though Asian men were not significantly different. Compared with men with high levels of education, men with low and medium levels were more likely to have never received an HIV test. Men born in the UK were more likely to have never received an HIV test compared with migrants. Other than migrants, men who reported condomless anal intercourse with two or more casual partners were least likely to have never tested for HIV.

Table 1.

Not ever testing and not testing in the preceding 12 months by demographic variables: univariate analyses

| Variable | Percent of sample (n) | Never tested for HIV |

Not tested in the past 12 months |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent | OR (95% CI) | Percent | OR (95% CI) | ||

| Age | |||||

| Under 20 | 8.4 (1181) | 65.4 | 5.16 (4.52 to 5.91) | 67.5 | 2.91 (2.55 to 3.32) |

| 20s | 37.6 (5314) | 25.7 | Ref | 41.6 | Ref |

| 30s | 22.4 (3169) | 15.6 | 0.50 (0.45 to 0.56) | 39.9 | 0.91 (0.85 to 1.02) |

| 40s | 16.8 (2368) | 18.1 | 0.61 (0.54 to 0.68) | 47.5 | 1.27 (1.15 to 1.40) |

| 50s | 9.8 (1383) | 25.6 | 0.94 (0.82 to 1.07) | 52.9 | 1.57 (1.40 to 1.77) |

| 60+ | 5.0 (710) | 30.4 | 1.19 (1.01 to 1.42) | 57.6 | 1.90 (1.62 to 2.23) |

| Wald test (χ2, df, p value) | 1098.37, 5, p<0.001 | 376.81, 5, p<0.001 | |||

| Orientation | |||||

| Gay | 83.7 (11 738) | 23.2 | Ref | 44.2 | Ref |

| Bisexual | 10.6 (1483) | 44.2 | 2.62 (2.35 to 2.93) | 59.1 | 1.83 (1.64 to 2.04) |

| Straight | 0.4 (59) | 69.5 | 7.55 (4.33 to 13.16) | 83.1 | 6.20 (3.14 to 12.24) |

| Queer | 1.4 (189) | 18.5 | 0.75 (0.52 to 1.09) | 38.1 | 0.78 (0.58 to 1.05) |

| Any other term | 0.4 (60) | 40.0 | 2.21 (1.32 to 3.71) | 51.7 | 1.35 (0.81 to 2.25) |

| Don't use a term | 3.5 (495) | 37.6 | 1.99 (1.65 to 2.4) | 55.6 | 1.58 (1.32 to 1.90) |

| Wald test (χ2, df, p value) | 370.98, 5, p<0.001 | 175.91, 5, p<0.001 | |||

| Ethnicity | |||||

| White | 92.6 (13 117) | 26.6 | Ref | 47.2 | Ref |

| Black | 2.1 (295) | 20.3 | 0.70 (0.53 to 0.94) | 31.5 | 0.51 (0.40 to 0.66) |

| Asian | 3.6 (513) | 24.1 | 0.88 (0.72 to 1.08) | 37.8 | 0.68 (0.57 to 0.81) |

| Other | 1.7 (234) | 16.2 | 0.54 (0.35 to 0.38) | 29.9 | 0.48 (0.36 to 0.63) |

| Wald test (χ2, df, p value) | 20.79, 3, p<0.001 | 72.49, 3, p<0.0001 | |||

| Education | |||||

| Low | 18.0 (2509) | 35.2 | 2.51 (2.27 to 2.78) | 55.6 | 1.86 (1.70 to 2.04) |

| Medium | 34.0 (4728) | 32.0 | 2.11 (1.93 to 2.3) | 49.4 | 1.45 (1.34 to 1.56) |

| High | 48.0 (6691) | 18.3 | Ref | 40.3 | Ref |

| Wald test (χ2, df, p value) | 431.19, 2, p<0.001 | 204.34, 2, p<0.001 | |||

| Migrancy | |||||

| Yes | 19.5 (2713) | 15.8 | 0.47 (0.42 to 0.52) | 35.1 | 0.57 (0.52 to 0.62) |

| No | 80.5 (11 201) | 28.7 | Ref | 48.9 | Ref |

| Wald test (χ2, df, p value) | 186.07, 1, p<0.0001 | 170.00, 1, p<0.001 | |||

| 2+NSSPNC | |||||

| Yes | 17.4 (2415) | 16.3 | 0.50 (0.44 to 0.56) | 27.3 | 0.37 (0.33 to 0.40) |

| No | 82.6 (11 462) | 28.2 | Ref | 50.4 | Ref |

| Wald test (χ2, df, p value) | 155.02, 1, p<0.001 | 442.08, 1, p<0.001 | |||

Findings from multivariate models (table 2) were similar in magnitude, direction and significance to findings in univariate models. However, men in their 50s were now less likely to have received an HIV test, and men aged 60 and above were not significantly different, as compared with men in their 20s. Finally, in multivariate models, men reporting condomless anal intercourse with two or more casual partners were least likely to have never tested for HIV.

Table 2.

Not ever testing and not testing in the preceding 12 months by demographic variables: multivariate analyses

| Variable | Adjusted OR (never tested) | Adjusted OR (12 months) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| Under 20 | 4.15 (3.59 to 4.80) | 2.47 (2.13 to 2.85) |

| 20s | Ref | Ref |

| 30s | 0.55 (0.49 to 0.62) | 1.02 (0.93 to 1.12) |

| 40s | 0.56 (0.49 to 0.62) | 1.26 (1.13 to 1.40) |

| 50s | 0.79 (0.68 to 0.91) | 1.46 (1.29 to 1.67) |

| 60+ | 0.91 (0.75 to 1.11) | 1.67 (1.40 to 1.99) |

| Orientation | ||

| Gay | Ref | Ref |

| Bisexual | 2.72 (2.40 to 3.08) | 1.73 (1.54 to 1.95) |

| Straight | 8.82 (4.81 to 16.20) | 6.18 (2.98 to 12.83) |

| Queer | 0.78 (0.52 to 1.19) | 0.87 (0.64 to 1.19) |

| Any other term | 2.25 (1.26 to 4.04) | 1.55 (0.88 to 2.72) |

| Don't use a term | 1.98 (1.61 to 2.42) | 1.55 (1.28 to 1.89) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | Ref | Ref |

| Black | 0.61 (0.43 to 0.85) | 0.48 (0.36 to 0.64) |

| Asian | 1.16 (0.92 to 1.07) | 0.78 (0.63 to 0.96) |

| Other | 0.72 (0.48 to 1.08) | 0.58 (0.42 to 0.79) |

| Education | ||

| Low | 1.92 (1.72 to 2.17) | 1.53 (1.38 to 1.70) |

| Medium | 1.48 (1.34 to 1.63) | 1.26 (1.16 to 1.37) |

| High | Ref | Ref |

| Migrancy | ||

| Yes | 0.62 (0.54 to 0.71)0 | 0.65 (0.59 to 0.72) |

| No | Ref | Ref |

| 2+NSSPNC | ||

| Yes | 0.47 (0.42 to 0.53) | 0.36 (0.32 to 0.40) |

| No | Ref | Ref |

| Wald test (χ2, df, p value) | 1716.89, 17, p<0.001 | 1105.27, 17,p<0.001 |

Testing in the past 12 months

Of the analysis sample, 53.7% of men had received a negative HIV test result in the 12 months prior to completing the survey.

Findings from univariate models are in table 1. Compared with men in their 20s, men in their 30s were not significantly different in their odds of having tested in the past 12 months; however, men both younger than 20 and aged 40 and above were more likely to not have received an HIV test in the past 12 months. Compared with men who identified as gay, men who described their orientation as bisexual or straight or who described not using a term were significantly more likely to have not tested in the past 12 months, but men who identified as queer or with any other term were not significantly different from gay men. All groups of non-white men were less likely to not have tested in the past 12 months, and all groups of men who did not have high education qualifications were more likely to not have tested in the past 12 months. Men who had migrated to the UK were less likely to have not received an HIV test in the past 12 months. Men who reported 2+NSSPNC in the preceding 12 months were least likely to have not tested for HIV in that time period. Findings from multivariate models (see table 2) were similar to findings from univariate models.

Higher risk men and testing recency

Men who reported 2+NSSPNC in the preceding 12 months reported testing more frequently than those who did not. Of these men, 59.5% had tested in the preceding 6 months, compared with 33.8% of men who reported lower risk. The OR reporting the likelihood of men at higher risk having not tested in the preceding 6 months was 0.35 and was statistically significant (table 3 for results).

Table 3.

Men reporting 2+NSSPNC testing in the preceding 6 months

| Six months | 2+NSSPNC | <2NSSPNC |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | 59.5% (1425) | 33.8% (3851) |

| No | 40.5% (972) | 66.2% (7536) |

| OR 0.35 (0.32 to 0.38) | χ2=535.46 | p<0.001 |

Preferences for future tests

Men who had never tested had significantly divergent preferences for future tests when compared with men who had received a negative test result (table 4). For this group, self-administered testing options (HIV self-testing and HIV self-sampling combined) were the most popular, followed by GUM and testing in general practice. These men had the lowest reported interest in testing in GUM settings of all groups included in this analysis. This is in contrast with the preferred testing locations of men who had previously tested with the majority preferring GUM clinics, followed by self-administered testing options and then preferring community-based testing services. Very few men stated that they had no intention of testing for HIV in the future indicating that even among those who have never done so, testing for HIV is acceptable.

Table 4.

Preferences for future HIV test by HIV testing history

| Most preferred next test | Percent of those who have never tested (n=3723) | Percent of those who have ever tested (n=10 512) | χ2, p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| General practice | 21.6 (803) | 8.8 (920) | 424.50, 0.001 |

| Private practice | 5.9 (220) | 2.4 (254) | 104.20, 0.001 |

| GUM clinic | 30.7 (1143) | 56.3 (5915) | 718.00, 0.001 |

| Community test | 7.8 (292) | 10.3 (1086) | 19.47, 0.001 |

| HIV self-sample | 12.0 (446) | 8.1 (856) | 48.70, 0.001 |

| HIV self-test | 20.2 (750) | 12.7 (1332) | 123.00, 0.001 |

| Other means to test | 0.9 (32) | 1.2 (125) | 2.74, 0.098 |

| Will not test | 1.0 (37) | 0.2 (24) | 37.76, 0.001 |

DF = 1 for all models.

When examining testing preferences by demographic and behavioural characteristics (table 5), these general patterns continued, with groups associated with lower levels of testing reporting preference for a greater diversity of testing services outside of GUM than groups who were more likely to have tested who tended to report a greater preference for GUM. The exception to this is community-based testing, which was more popular among groups more likely to have tested previously.

Table 5.

Demographic details and preferred setting for next HIV test in proportions (in percentages)

| Subgroups | GP | PP | GUM | Com test | HIVSS | HIVST | Other | Will not |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All men | 12.1 | 3.3 | 49.6 | 9.7 | 9.2 | 14.6 | 1.1 | 0.4 |

| Age | ||||||||

| <20s | 17.1 | 7.4 | 42.9 | 6.1 | 9.8 | 15.4 | 0.9 | 0.4 |

| 20s | 13.1 | 3.5 | 49.7 | 6.3 | 10.6 | 15.8 | 0.8 | 0.2 |

| 30s | 10.2 | 2.4 | 51.8 | 10.3 | 8.9 | 15.0 | 1.2 | 0.3 |

| 40s | 10.4 | 2.9 | 50.3 | 12.5 | 7.5 | 14.8 | 1.2 | 0.6 |

| 50s | 11.8 | 2.4 | 47.9 | 17.5 | 6.9 | 10.8 | 1.9 | 0.9 |

| 60+ | 11.4 | 2.5 | 51.4 | 14.1 | 8.2 | 9.3 | 1.8 | 1.3 |

| Orientation | ||||||||

| Gay | 11.9 | 3.0 | 51.0 | 9.5 | 8.8 | 14.4 | 1.1 | 0.4 |

| Bisexual | 14.2 | 4.9 | 43.3 | 9.6 | 10.6 | 15.8 | 1.2 | 0.4 |

| Straight | 13.6 | 6.8 | 39.0 | 10.2 | 3.4 | 23.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 |

| Queer | 10.6 | 1.6 | 48.7 | 21.7 | 7.4 | 9.5 | 0.5 | 0.0 |

| Any other term | 20.0 | 0 | 35.0 | 13.3 | 16.7 | 11.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 |

| Don't define | 11.5 | 4.9 | 41.4 | 8.5 | 12.3 | 19.8 | 0.6 | 1.0 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||

| White | 12.5 | 3.2 | 49.2 | 9.6 | 9.2 | 14.8 | 1.0 | 0.4 |

| Black | 6.1 | 4.7 | 51.0 | 7.4 | 12.8 | 14.5 | 2.7 | 0.7 |

| Asian | 7.8 | 5.0 | 52.7 | 13.0 | 6.8 | 12.8 | 1.4 | 0.4 |

| Other | 5.1 | 4.2 | 61.1 | 11.5 | 6.4 | 10.3 | 1.3 | 0.0 |

| Education | ||||||||

| Low | 15.8 | 4.6 | 47.0 | 8.3 | 9.0 | 13.4 | 1.4 | 0.5 |

| Medium | 14.3 | 3.2 | 47.1 | 8.5 | 10.4 | 15.4 | 0.7 | 0.4 |

| High | 9.0 | 3.0 | 52.3 | 11.1 | 8.4 | 14.6 | 1.2 | 0.4 |

| Migrancy | ||||||||

| Yes | 8.9 | 3.7 | 54.8 | 11.0 | 7.1 | 12.9 | 1.4 | 0.3 |

| No | 12.8 | 3.2 | 48.4 | 9.4 | 9.6 | 15.1 | 1.0 | 0.5 |

| 2+NSSPNC | ||||||||

| Yes | 7.6 | 2.7 | 55.4 | 10.1 | 7.3 | 15.8 | 0.9 | 0.3 |

| No | 13.1 | 3.4 | 48.5 | 9.4 | 9.6 | 14.4 | 1.0 | 0.5 |

GP, general practitioner; PP, private practice, GUM, genitourinary medicine centre; Com test, community testing; HIVSS, HIV self-sampling; HIVST, HIV self-testing.

Discussion

The BHIVA testing guidelines for the UK state that all MSM should test at least annually or more frequently if there is ongoing risk.12 Our results clearly demonstrate that UK testing guidelines are not being uniformly followed by men in different life stages. These findings report levels of HIV testing broadly congruent with the similarly opportunistically recruited Scottish Bar Survey,13 and substantially higher rates than among MSM in the third National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles, a general population probability survey in which 51.6% of MSM reported ever testing for HIV.14

Our results describe which groups of MSM in the England are less likely to be following the BHIVA guidelines. In multivariate models, we found that men under the age of 20 were less likely than men between the ages of 20 and 30 to have tested in the preceding 12 months. As age increased the number of men who had never tested declined, but so too did testing frequency after a peak when men were in their 20s and 30s. This suggests a strong age trend whereby men are, in part, aware of their own HIV testing needs and responding to them by testing more frequently when most sexually active (between the ages of 20 and 40) with frequency declining later. This is congruent with other evidence which suggests strong age trends in HIV testing patterns among MSM in Europe, North America and Australia.13 15–18 However, despite regular testing fitting into the life courses of many MSM, a significant proportion (over 25%) of MSM over the age of 50 have never tested for HIV, indicating that throughout life many MSM are choosing not to ever test for HIV.

Bisexual men were significantly less likely than gay men to have tested. Straight identified MSM were the least likely to test. In total 83% of MSM who identified as straight (n=59) had not tested for HIV in the past 12 months and nearly 70% had never received an HIV test result. There are therefore clear associations between sexual identity and rates of HIV testing within this sample, and our results indicate that either these men (correctly or incorrectly) do not believe themselves to be at risk of HIV infection, or that their needs are not being adequately addressed through existing service provision. These patterns have been observed in several other European countries.14–17 19

Also consistent with existing evidence15 16 is our finding that men with lower levels of education were less likely to test for HIV. As this association weakened in adjusted ORs, these data are suggestive of a clustering of other demographic influences on likelihood to test around men with medium and low levels of education. These results did however retain significance indicating that there is an important educational component to decision-making around HIV testing and perhaps in access to services. This underscores the importance of psychosocial barriers to testing among this population, barriers on which expansion of testing in itself cannot overcome.20

The men in our sample who were most likely to have tested for HIV were men who reported having two non-steady partners with whom they did not use condoms for anal sex in the preceding 12 months. In this group, only 16.2% had never received a test result, the lowest proportion bar migrants and men of ‘other’ ethnicity. Only 27.3% had not tested in the preceding 12 months, the lowest of any group in our sample. However, 40.5% had not tested in the preceding 6 months, indicating that a significant proportion of these men are likely falling short of BHIVA guidelines to test every 3 months in the presence of ongoing risk.

GUM settings remain the most popular future testing setting for MSM in England, for all groups except those who had never tested. Those who have never tested have a preference for a wider range of testing options than those who had tested before. However, regardless of testing history, men valued a range of settings indicating that while expanding access through providing a wider variety of ways to test is worthwhile, no one testing method is likely to lead to a surge in uptake of HIV testing.

Importantly, community-based rapid HIV testing services were most popular with the demographic groups who were most likely to have ever tested (and to a lesser degree among men reporting higher risk), indicating that expanding access to these services is unlikely to be efficient if policy goals include meeting the testing needs of men that would not otherwise be testing.

Sale of HIV self-testing kits was made legal in the UK from 1 April 2014 but no CE-marked product was available in the market when this survey took place. Despite this, and the relatively widespread availability of HIV self-sampling, self-testing was more popular than self-sampling across all subgroups, with more pronounced preferences for self-testing in those who had not tested in the last year. Further research is required as to whether self-sampling will maintain a position in the HIV testing landscape when self-testing becomes more widespread.

In light of our findings, the value of the current HIV testing guidelines can be called into question, particularly the guidance to test annually. If commissioners, clinicians and providers are to use these guidelines alone to inform testing interventions, the priority will be to raise the proportion of gay men, bisexual men and other MSM that have ever tested and encourage them to test at least annually. Focus will fall on the relatively young and old; men with lower levels of educational attainment; and those who are not gay identified. This goal could be achieved by increasing focus on providing a wide range of testing opportunities to better meet the diverse preferences of this population. This however could only have limited impact on the more intractable psychosocial barriers to testing, including stigma and fear of a positive result.5 20

Further, the groups who would likely be targeted by this strategy are not reflective of those most likely to have undiagnosed HIV, and this focus would therefore deliver significant diminishing returns per infection detected from a resources perspective. A perhaps more impactful approach would instead focus on the behavioural element of the policy and prioritise reducing the average time between HIV infection and diagnosis with an aim to reduce community viral load. This is congruent with modelling evidence suggesting testing high activity MSM once or twice per year would yield similar results to testing all MSM with the same frequency.21 This approach would require increasingly targeted interventions and more nuanced information around testing in response to risk, while simultaneously maintaining and expanding the services these groups most value. This would instead direct focus to increasing the frequency of testing among men at higher risk through ongoing condomless anal intercourse with multiple partners, while simultaneously raising the rate of annual testing among both Black and White identified men22 and men between the ages of 20 and 44.4 These groups of MSM are most likely to have HIV in England, and are also among the most likely to test.4 22 In this scenario, GUM would remain a crucial piece of this service mix, with increases in investment in self-administered testing methods, which may also serve to triage lower risk MSM to less expensive (per unit cost) testing options. These approaches will likely require more focus on the psychosocial barriers to testing and a greater degree of individual engagement in the provision of nuanced and in-depth interventions that acknowledge men's own values and aspirations around sex and understand the social contexts in which testing decisions are made.

Limitations

Our results should be interpreted with some caution. For one, while our participants who are gay identified are largely representative of the gay population in the UK, there is greater divergence between convenience and probability samples of other non-gay identified MSM in our sample and others (see ref. 23 for a full discussion). Furthermore, in convenience samples of MSM in the UK reported HIV testing tends to be higher than in probability-based samples, indicating that we may overestimate the level of testing in the population as a whole but in particular among non-gay identified MSM. This indicates that the true differences in testing between gay and non-gay identified MSM may be more pronounced than the ones we present.

Another limitation is that for most men, HIV self-testing was an entirely hypothetical testing option at the time of this research. This is in contrast to the many other options for HIV testing which men could (and did) use. HIV self-sampling is also often advertised as ‘HIV self-testing’ in England, so it is possible that some of our respondents were confused about the difference between these two options.

Finally, because we had low levels of missing data, we did not make attempts to control it. It is possible that those with the highest barriers to testing could be less likely to answer questions relating to HIV testing in research such as GMSS.

Conclusions

HIV testing policy in England is guided by BHIVA testing guidelines from 2008 which emphasises annual testing for all MSM (regardless of sexual behaviour) and more frequently for those at increased risk. Our results indicate that younger men, older men and those who are not gay identified were the least likely to test for HIV. If we were to use these policies to guide service development, our focus would be on increasing the proportion of MSM who had had an HIV test every year, irrespective of their sexual risk and precautionary behaviours. This however would not focus on the MSM most at risk of HIV and could potentially lead to increasing screening costs per infection detected. Instead, we feel the promotion of more frequent testing among the groups most at risk of infection should be prioritised, effectively reducing the time interval between tests to reduce the time between infection and diagnosis.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Sigma Research @SigmaResearch1

Contributors: FH and PW were responsible for the design and execution of the data collection, while TCW and GJM-T were responsible for the analysis and interpretation of findings. TCW was responsible for initial drafting with revisions and critical input from all other authors. All authors have agreed the final manuscript.

Funding: This research was funded by Terrence Higgins Trust as part of the HIV Prevention England programme (2012–2016).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: For information about Gay Men's Sex Survey (GMSS) including the survey text, please visit sigmaresearch.org.uk.

References

- 1.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M et al. , HPTN 052 Study Team. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med 2011;365:493–505. 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Granich RM, Gilks CF, Dye C et al. Universal voluntary HIV testing with immediate antiretroviral therapy as a strategy for elimination of HIV transmission: a mathematical model. Lancet 2009;373:48–57. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61697-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gupta S, Granich R, Suthar AB et al. Global policy review of antiretroviral therapy eligibility criteria for treatment and prevention of HIV and tuberculosis in adults, pregnant women, and discordant couples. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013;62:e87–97. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31827e4992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skingsley A, Yin Z, Kirwan P et al. HIV in the UK—situation report 2015: data to end 2014. London: Public Health England, November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lorenc T, Marrero-Guillamón I, Llewellyn A et al. HIV testing among men who have sex with men (MSM): systematic review of qualitative evidence. Health Educ Res 2011;26:834–46. 10.1093/her/cyr064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Witzel TC, Guise A, Nutland W et al. It starts with me: privacy concerns and stigma in the evaluation of a Facebook health promotion intervention. Sex Health 2016;13:228–33. 10.1071/SH15231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deblonde J, De Koker R, Hamers FF et al. Barriers to HIV testing in Europe: a systematic review. Eur J Public Health 2010;20:422–32. 10.1093/eurpub/ckp231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bailey AC, Roberts J, Weatherburn P et al. Community HIV testing for men who have sex with men: results of a pilot project and comparison of service users with those testing in genitourinary medicine clinics. Sex Transm Infect 2009;85:145–7. 10.1136/sti.2008.032359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suthar AB, Ford N, Bachanas PJ et al. Towards universal voluntary HIV testing and counselling: a systematic review and meta-analysis of community-based approached. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001496 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Figueroa C, Johnson C, Verster A et al. Attitudes and acceptability on HIV self-testing among key populations: a literature review. AIDS Behav 2015;19:1949–65 10.1007/s10461-015-1097-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Department of Health. The Government's mandate to NHS England for 2016–17. Published online only [gov.uk].

- 12.British HIV Association. UK National Guidelines for HIV Testing. London, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knussen C, Flowers P, McDaid LM. Factors associated with recency of HIV testing amongst men residing in Scotland who have sex with men. AIDS Care 2014;26:297–303. 10.1080/09540121.2013.824543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sonnenberg P, Clifton S, Beddows S et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and uptake of interventions for sexually transmitted infections in Britain: findings from the National Surveys of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal). Lancet 2013;382:1795–806. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61947-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zablotska I, Holt M, de Wit J et al. Gay men who are not getting tested for HIV. AIDS Behav 2012;16:1887–94. 10.1007/s10461-012-0184-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fernández-Dávila P, Folch C, Ferrer L et al. Who are the men who have sex with men in Spain that have never been tested for HIV? HIV Med 2013;14:44–8. 10.1111/hiv.12060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carvalho C, Fuertes R, Lucas R et al. HIV testing among Portuguese men who have sex with men—results from the European MSM Internet Survey (EMIS). HIV Med 2013;14:15–18. 10.1111/hiv.12058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Margolis AD, Joseph H, Belcher L et al. ‘Never testing for HIV’ among men who have sex with men recruited from a social networking website, United States. AIDS Behav 2012;16:23–9. 10.1007/s10461-011-9883-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berg RC. Predictors of never testing for HIV among a national online sample of men who have sex with men in Norway. Scand J Public Health 2013;41:398–404. 10.1177/1403494813483216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flowers P, Knussen C, McDaid L et al. Has testing been normalised? An analysis of changes in barriers to HIV testing among men who have sex with men between 2000 and 2010 in Scotland, UK. HIV Med 2013;14:92–8. 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2012.01041.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Punyacharoensin N, Edmunds WJ, De Angelis D. Effects of pre-exposure prophylaxis and combination HIV prevention for men who have sex with men in the UK: a mathematical modelling study. Lancet HIV 2016;3:e94–e104. 10.1016/S2352-3018(15)00056-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Millett GA, Peterson JL, Flores SA et al. Comparisons of disparities and risks of HIV infection in black and other men who have sex with men in Canada, UK and USA: a meta-analysis. Lancet 2012;380:341–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60899-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prah P, Hickson F, Bonell C et al. Men who have sex with men in Britain: comparison of estimates from a probability sample and community-based surveys. Sex Transm Infect 2016;92:455–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]