Abstract

Background

The UK Department of Health recommends annual influenza vaccination for healthcare workers, but uptake remains low. For staff, there is uncertainty about the rationale for vaccination and evidence underpinning the recommendation.

Objectives

To clarify the rationale, and evidence base, for influenza vaccination of healthcare workers from the occupational health, employer and patient safety perspectives.

Design

Systematic appraisal of published systematic reviews.

Results

The quality of the 11 included reviews was variable; some included exactly the same trials but made conflicting recommendations. 3 reviews assessed vaccine effects in healthcare workers and found 1 trial reporting a vaccine efficacy (VE) of 88%. 6 reviews assessed vaccine effects in healthy adults, and VE was consistent with a median of 62% (95% CI 56 to 67). 2 reviews assessed effects on working days lost in healthcare workers (3 trials), and 3 reported effects in healthy adults (4 trials). The meta-analyses presented by the most recent reviews do not reach standard levels of statistical significance, but may be misleading as individual trials suggest benefit with wide variation in size of effect. The 2013 Cochrane review reported absolute effects close to 0 for laboratory-confirmed influenza, and hospitalisation for patients, but excluded data on clinically suspected influenza and all-cause mortality, which had shown potentially important effects in previous editions. A more recent systematic review reports these effects as a 42% reduction in clinically suspected influenza (95% CI 27 to 54) and a 29% reduction in all-cause mortality (95% CI 15 to 41).

Conclusions

The evidence for employer and patient safety benefits of influenza vaccination is not straightforward and has been interpreted differently by different systematic review authors. Future uptake of influenza vaccination among healthcare workers may benefit from a fully transparent guideline process by a panel representing all relevant stakeholders, which clearly communicates the underlying rationale, evidence base and judgements made.

Keywords: influenza vaccination, flu vaccination, healthcare workers, NHS

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study unpicks the three main perspectives justifying health workers being vaccinated against influenza and the evidence of an effect for each. This includes the occupational perspective, examining the effect on illness; the employer perspective, examining working days lost and the patient safety perspective, examining the effect on transmission to patients.

The analysis draws on published systematic reviews, which draw on a similar population of trials, and summaries the results and the consistency of their conclusions.

We conclude from an occupational health perspective, there is consistency in the effect of the vaccine in preventing illness; for the employer perspective, some meta-analyses are misleading and the individual trials all seem to show a reduction in days lost and for an effect on patient safety, the results are conflicting and unclear.

The study does not aim to provide recommendations but suggests a conceptual framework and evidence summaries that may help frame a guideline development process to provide clear messages to help health workers make informed decisions.

Background

The UK Department of Health (DH) currently recommends that all healthcare workers (HCWs) in direct contact with patients or clients are vaccinated against influenza each year.1 2 Although this policy is not enforced, an aspirational target of 75% vaccination coverage has been set for all hospital and community services and has recently been linked to additional funding known as ‘winter pressure funds’.3

Despite this target, vaccination coverage among HCWs remains low, at 50.6% during the 2015–2016 season and 54.9% during the 2014–2015 season.4 5 A systematic review on self-reported reasons for non-uptake of influenza vaccine by HCWs identified two major factors: a wide range of misconceptions or lack of knowledge about influenza infection and lack of convenient access to vaccine.6 On the reasons for accepting influenza vaccine, self-protection was the most important reason. We were interested in the degree of misconceptions by health workers in the literature. We noted that systematic reviews and related papers often draw on the same body of evidence, reached different conclusions and wondered whether this may perhaps contribute to the muddle, rather than helping.7–9

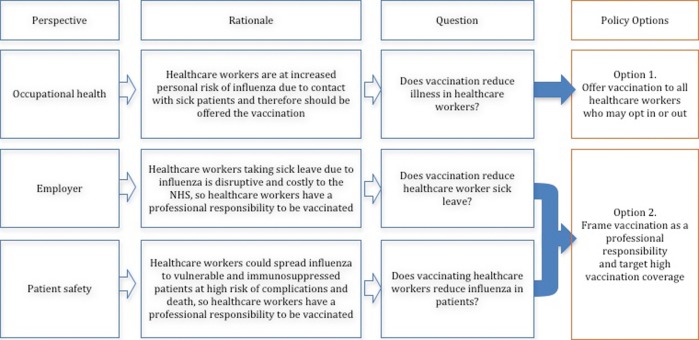

In this paper, we sought to unpick the different rationales for vaccination and summarise the evidence base for each through a critical appraisal and summary of all available relevant systematic reviews. To do this, we developed a conceptual framework (figure 1). This presents the two main policy options available to the UK DH and the rationale and evidence requirements for each:

Offer vaccination to all HCWs—This policy takes an occupational health perspective, which could be justified by evidence of increased risk of influenza among staff. Healthcare workers would require reliable evidence on the efficacy and safety of the vaccine and could opt in or out of vaccination.

Frame vaccination as a ‘professional responsibility’ and target high vaccination coverage—This policy could be justified from either an employer perspective: if vaccination reduced sick leave and service disruption, or a patient safety perspective: if there were evidence that vaccination of HCWs reduced influenza in vulnerable patients.

Figure 1.

Perspectives for benefit of influenza vaccination of health workers, evidence required and policy framing for each.

The current policy as stated in the 2015–2016 Influenza Plan and Annual Influenza Letter refers to the occupational health and patient safety perspectives: to protect HCWs themselves from influenza and to reduce the risk of passing the virus on to vulnerable patients.5 10

Methods

The protocol for this evidence appraisal is included in online supplementary appendix 1. We aimed to include all systematic reviews, published in English language journals, which evaluate the effects of influenza vaccination in either healthy adults (over 18 years old) or HCWs (nurses, doctors, nursing and medical students, other health professionals including ancillary staff) of all ages. We sought evidence of effects on laboratory-confirmed influenza and clinically suspected influenza (the occupational health perspective), working days lost (the employer perspective) and laboratory-confirmed influenza, clinically suspected influenza, death or hospitalisation of patients (the patient safety perspective).

bmjopen-2016-012149supp_appendices.pdf (758.2KB, pdf)

Search methods for identification of systematic reviews

Two authors (MK and AK) independently searched MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, AMED and HMIC for all systematic reviews from January 1990 to December 2015. Search terms were ‘influenza vaccine’, ‘adult’, ‘healthcare worker’, ‘doctor’, ‘nurse’, ‘effectiveness’, ‘efficacy’, ‘absence’, ‘systematic review’ and ‘meta-analysis’ (see online supplementary appendix 2). Bibliographies of retrieved articles were also searched to identify additional reviews.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors (MK and AK) independently reviewed titles and abstracts for inclusion in the review, applied the inclusion criteria and extracted data onto a standardised form. For each included review, we extracted information on the review objectives, perspective, search strategy, inclusion criteria, outcome measures, included studies, risk of bias of included studies, results and conclusions.

Where possible, we only extracted data for inactivated parenteral vaccines, as per the current UK influenza vaccination programme. Where this distinction was not clear, we extracted data for all vaccines. In addition, where possible, we only extracted data for seasonal influenza vaccination. Where this distinction was not clear, we extracted data for all vaccine schedules. Two reviewers (MK and AK) independently checked data extraction for agreement. A third reviewer (DS) was consulted to resolve disagreements.

Two authors (MK and AK) independently appraised the methodological quality of each review using the AMSTAR tool for appraising systematic reviews.11 Disagreements were resolved through discussion and, where necessary, through appraisal by a third author (DS). The AMSTAR tool required us to make judgements about how well the systematic review authors applied 11 methodological techniques to reduce bias and error in their reviews. While these criteria are likely to identify reviews with major flaws, they are less effective at detecting errors in interpretation.

Where possible, outcome data are presented as vaccine efficacy (VE) expressed as a percentage using the formula: VE=1−relative risk (RR), with 95% CIs. Where RR was not presented, data are presented as reported in the source systematic review. The number needed to vaccinate (NNV) to prevent one case of influenza in healthy adults and HCWs was calculated using the formula: NNV=1/absolute risk reduction, with 95% CIs. To estimate the impact from an economic perspective, the number of prevented working days lost was calculated per 100 HCWs.

We also extracted the authors' inferences or recommendations.

Results

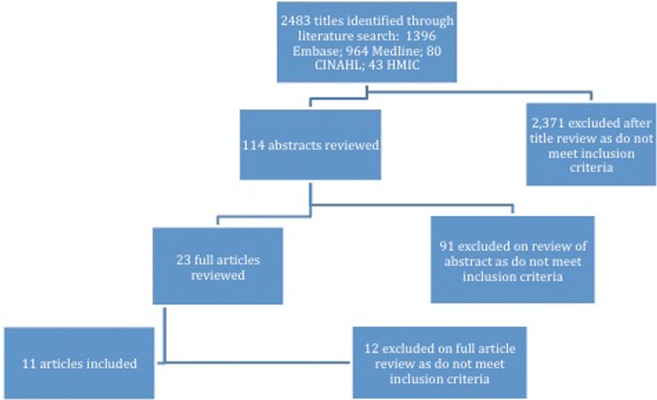

The search identified 2483 unique citations of which 2371 were excluded after screening the title, and a further 91 were excluded after screening the abstract. The full inclusion criteria were applied to 23 full text articles, of which 11 were included. Of the 12 excluded papers, 10 were excluded as they were not systematic reviews, 1 was a previous version of a review already included and 1 did not include data on HCWs or healthy adults (figure 2, see online supplementary appendix 3). One review was supported by an influenza vaccine manufacturer12 and the rest by public bodies or agencies (table 1).

Figure 2.

Flow chart of search process.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included systematic reviews

| Review ID | Funding source | Search period/end date | Perspective reported |

Populations of interest | Included vaccines | Included study designs | No. of relevant studies | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Occupational health | Employer | Patient safety | |||||||

| Burls et al13 | European Scientific Working Group on Influenza | Until June 2004 | Yes (HCWs) | Yes | Yes | HCW; patients (high risk) | Any | All | 5 |

| Michiels et al14 | National Institute for Health and Disability Insurance in Belgium | January 2006 to March 2011 | Yes (HCWs and healthy adults) | Yes | Yes | HCW; healthy adults (16–65 years); patients (no further definition) | Trivalent inactivated | RCTs and non-RCT | 10 |

| Ng and Lai12 | None stated | Date of launch to March 2011 | Yes (HCWs) | Yes | No | HCW | Any | RCTs and non-RCTs | 3 |

| Demicheli et al19 | None stated | Date of launch to May 2013 | Yes (healthy adults) | Yes | No | Healthy adults (16–65 years) | Inactivated parenteral | RCTs and quasi-RCTs | 20 |

| DiazGranados et al15 | Authors employees of Sanofi Pasteur | Until October 2011 | Yes (healthy adults) | No | No | Healthy adults (non-elderly) | Inactivated parent, live attenuated intranasal, adjuvant or recombinant | RCTs and quasi-RCTs | 20 |

| Ferroni and Jefferson16 | None stated | Date of launch to March 2011 | Yes (healthy adults) | Yes | Yes | Patients (no further definition); healthy adults | Any | SRs and RCTs | 6 |

| Osterholm et al17 | Alfred P Sloan Foundation | January 1967 to February 2011 | Yes (healthy adults) | No | No | Healthy adults (18–46 years) | Any | RCTs and observational studies | 7 |

| Villari et al18 | Italian Ministry of Health and the Emilia Romagna Regional Health Agency | January 1966 December 2002 | Yes (healthy adults) | No | No | Healthy adults (mainly 16–65 years) | Any | RCTs and quasi-RCTs | 26 |

| Ahmed et al22 | None stated | January 1948 to June 2012 | No | No | Yes | Patients in healthcare facilities | Inactivated or live attenuated | RCTs, cohort, case–control studies | 6 |

| Dolan et al23 | WHO Global Influenza Programme | Not stated | No | No | Yes | Patients (at high risk of respiratory infection) | Any | RCTs and observational studies (cross sectional/cohort) | 16 |

| Thomas et al21 | None stated | Date of launch to March 2013 | No | No | Yes | Patients (aged >60 years living in institutions) | Any | RCTs and non-RCTs | 3 |

HCWs, healthcare workers; RCTs, randomised controlled trials; SRs, systematic reviews.

Of the 11 included systematic reviews, three evaluated the effects of influenza vaccination in HCWs12–14 and six in healthy adults;14–19 five evaluated the effects in patients13 14 20–22 and five evaluated the effects of vaccination on days off work12–14 16 19 (table 1, see online supplementary appendices 4 and 5). Two Cochrane reviews were included; the main analysis includes only the most recent version of the review, but where necessary we refer back to the earlier editions.

Occupational health perspective: effect on illness

In healthcare workers

Three reviews directly evaluate VE among HCWs12–14 (table 2; see online supplementary appendix 6).

Table 2.

Vaccination effects in healthcare workers (the occupational health perspective)

| Review ID | Population | Laboratory-confirmed influenza |

Clinically suspected influenza |

SR authors’ conclusions |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of studies (participants) | Efficacy (95% CI) | No. of studies (participants) | Efficacy (95% CI) | On efficacy | For policy | ||

| Ng and Lai12 | HCW | 1 RCT (359) | 88% (59 to 96) | 2 RCTs (606) | No significant effect in either study | ‘No definitive conclusion on the effectiveness of influenza vaccinations in HCWs’ | ‘Further research is necessary to evaluate whether annual vaccination is a key measure to protect HCWs’ |

| Burls et al13 | HCW | 1 RCT (361) | 88% (47 to 97) Inf. A 89% (14 to 99) Inf. B |

2 RCTs (606) | No significant effect in either study | ‘Vaccination was highly effective’ | ‘Effective implementation should be a priority’* |

| Michiels et al14 | HCW | 1 non-RCT (262) | 90% (25 to 99) | 1 RCT (346) | 53% (NS) p=0.002 | None stated | None stated |

| Demicheli et al19 | Healthy adults | 22 RCTs (51 724) | 62% (56 to 67) | 16 (25 795) | 17% (13 to 22) | ‘Influenza vaccines have a very modest effect in reducing influenza symptoms’ | ‘Results seem to discourage the usage of vaccination against influenza in healthy adults as a routine public health measure.’† |

| DiazGranados et al15 | Healthy adults | Not stated | 59% (50 to 66) | – | – | ‘Influenza vaccines are efficacious’ | None stated |

| Osterholm et al17 | Healthy adults | 6 (31 892) | 59% (51 to 67) | – | – | ‘Influenza vaccines provide moderate protection against confirmed influenza’ | None stated |

| Villari et al18 | Healthy adults | 25 (18 920) | 63% (53 to 71) | 49 (46 022) | 22% (16 to 28) | ‘Estimates (of effect) vary substantially’ | ‘Further trials…are needed to provide definitive answers for policymakers’ |

| Michiels et al14 | Healthy adults | 14 (21 616) | 44% to 73% (range) | 19 (19 046) | No significant effect | ‘Inactivated influenza vaccine shows efficacy in healthy adults’ | None stated |

| Ferroni and Jefferson16 | Healthy adults | 5 (43 830) | 44% to 77% (range) | 18 (19 046) | 7% to 30% (range) | ‘Inactivated vaccines are effective at reducing infection’ | None stated |

*This conclusion may be influenced by the reported effects on protecting patients and days off work in tables 3 and 4, respectively.13

†This conclusion is influenced by the additional findings of no demonstrable effect on complications such as pneumonia or transmission.19

HCW, healthcare worker; RCTs, randomised controlled trials; SR, systematic review.

Methodological quality of reviews: Ng and Lai12 was the most up-to-date review and was judged to be a high-quality review against the AMSTAR criteria, with only minor limitations (table 3). Burls et al13 and Michiels et al14 have major limitations (table 3).

Table 3.

AMSTAR assessments of methodological quality

| AMSTAR criteria | Burls et al13 | Michiels et al14* | Ng and Lai12 | Demicheli et al19 | Diaz Granados et al15 | Ferroni and Jefferson16* | Osterholm et al17 | Villari et al18 | Ahmed et al22 | Dolan 2012 | Thomas et al21 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. ‘A priori’ design? | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| 2. Duplicate study selection and extraction? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 3. Comprehensive literature search? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 4. Did they attempt to find unpublished studies and grey literature? | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| 5. List of studies (included and excluded) provided? | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| 6. Characteristics of included studies provided? | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 7. Scientific quality of included studies assessed and documented? | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 8. Scientific quality of included studies used appropriately in formulating conclusions? | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| 9. Appropriate methods used to combine the findings of studies? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 10. Likelihood of publication bias assessed? | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| 11. Conflict of interest stated? | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Total risk score* | 5 | 6 | 9 | 10 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 9 | 7 | 7 | 11 |

Included studies: Ng and Lai12 and Burls et al13 included the same three randomised controlled trials (RCTs) enrolling 967 participants. Michiels et al14 included two trials, both different to those included by Ng and Lai12 and Burls et al,13 and describe both as RCTs although one is clearly non-randomised.23 Neither of these trials is mentioned in the list of excluded studies presented by Ng and Lai.12

Results: Ng and Lai12 and Burls et al13 report a VE of 88% against laboratory-confirmed influenza, based on a single trial among 264 hospital HCWs, although Burls et al13 presents the result stratified by influenza virus type.25 Ng and Lai12 and Burls et al13 report that the effects on clinically suspected influenza were not statistically significant across two trials.26 27 In an additional RCT among 356 dental students reported by Michiels et al,14 28 VE against clinically suspected influenza was 53% (p=0.03; table 2).

Consistency of conclusions: Although they evaluated exactly the same three trials and present similar summaries, Ng and Lai12 and Burls et al13 made very different inferences: Burls et al13 recommended health worker vaccination ‘as a priority’, whereas Ng and Lai12 stated that ‘no definitive conclusion’ could be made (table 2). The strong recommendation by Burls et al13 may be influenced by their additional findings related to protecting patients and reducing days off work described below.

In healthy adults

In addition, six reviews report VE in healthy adults, which may reasonably be extrapolated to HCWs12 13 16–18 (table 2, see online supplementary appendix 7).

Methodological quality of reviews: Of the most recent reviews, Demicheli et al19 was a high-quality review with only minor limitations, whereas DiazGranados et al,15 Osterholm et al,17 Michiels et al14 and Ferroni and Jefferson16 had some or major limitations (table 3).

Included studies: Demicheli et al19 included 20 trials of inactivated parenteral vaccines. The other reviews included between 6 and 26 studies, influenced by different inclusion criteria and search dates. Michiels et al14 only included studies of trivalent inactivated vaccines, Osterholm et al17 only included studies in people aged 18–46 years and Ferroni and Jefferson16 and Michiels et al14 summarise the results of the previous version of the Demicheli Cochrane review,19 29 plus a few additional trials.

Results: Demicheli et al,19 DiazGranados et al,15 Osterholm et al17 and Villari et al18 report very similar VE against laboratory-confirmed influenza despite differences in the number of included trials (62%, 59%, 59% and 63%, respectively). Of these only Demicheli et al19 and Villari et al18 report VE against clinically suspected influenza, which is much lower (17% and 22%, respectively). The remaining two reviews rely largely on the results of Jefferson et al29 but only report the range of effects across trials.

Consistency of conclusions: All six reviews conclude that the vaccine is effective at preventing laboratory-confirmed influenza. However, Demicheli et al19 states that “the results of this review provide no evidence for the utilisation of vaccination against influenza in healthy adults as a routine public health measure”, perhaps basing this on their judgement that this efficacy was too low or on their additional findings that vaccination did not reduce complications of influenza. The oldest review18 called for more trials, and the remaining four reviews did not make any policy recommendations.

Employer perspective: effect on working days lost

In healthcare workers

Two reviews described above12 13 include the same three trials and report the impact of vaccinating HCW on working days lost.

Methodological quality: see above.

Results: Ng and Lai12 reports a meta-analysis of two of these trials, which does not reach standard levels of statistical significance (mean difference (MD) −0.08 days, 95% CI −0.19 to 0.02, I2=0%, two trials, 540 participants) and states that the third trial could not be included in the meta-analysis due to the way the data were presented. However, Burls et al13 reports that the third trial found a statistically significant reduction in working days lost of 0.4 (p=0.02) (table 4).

Table 4.

Vaccination effects on the health system (the employer perspective)

| Review ID | Population | Days off work |

Review authors’ conclusions |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of studies (participants) | Mean difference (days) | On efficacy | For policy | ||

| Ng and Lai12 | HCW | 2 (540) | –0.08 (95% CI –0.19 to 0.02) (third study not included in meta-analysis) | ‘No definitive conclusion on the effectiveness of influenza vaccinations in HCWs’ | ‘Further research is necessary to evaluate whether annual vaccination is a key measure to protect HCWs’ |

| Burls et al13 | HCW | 3 (967) | Statistically significant difference in only one of the three studies (MD 0.4 days, p=0.02) | ‘Vaccination was highly effective’ | ‘Effective implementation should be a priority’* |

| Demicheli et al19 | Healthy adults | 4 (3726) | Good match—three studies (2596), MD=−0.09 (−0.19 to 0.02) Matching absent/unknown—one study (1130), MD=0.09 (0.00 to 0.18) |

‘A modest effect on time off work’ | ‘No evidence for the usage of vaccination against influenza in healthy adults as a routine public health measure’† |

| Michiels et al14 | Healthy adults | Not stated | Not stated (refers to Jefferson 2010) | None stated | None stated |

| Ferroni and Jefferson16 | Healthy adults | 1 meta-analysis including 5 studies (5393) | Good match—0.21 Matching absent/unknown—0.09 (refers to Jefferson 2010) |

‘May be marginally more effective than placebo’ | None stated |

*This conclusion may be influenced by the reported effects on vaccine efficacy and protecting patients in tables 2 and 3, respectively.13

†This conclusion is influenced by the additional findings of no demonstrable effect on complications such as pneumonia or transmission.19

HCW, healthcare worker; MD, mean difference.

In healthy adults

One Cochrane review reports effects on working days lost in healthy adults,19 and two other systematic reviews14 16 simply present the results from an earlier version of Demicheli et al19 (ref. 28) (table 4).

Methodological quality: see above.

Results: The 2010 version of the Cochrane review29 reported statistically significant effects on working days lost, but the 2014 version19 did not, even though there were no additional trials.

In the study of Jefferson et al,29 the authors combined studies where the vaccine was a good match with the circulating virus (MD −0.21 working days lost, 95% CI −0.36 to −0.05; 4 trials, 4263 participants) and a poor match (MD 0.09, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.18, one trial, 1130 participants) and present an overall mean reduction of 0.13 working days lost.29 In the updated version,19 the authors removed one study conducted during the 1960s pandemic, which had a large effect on working days lost, and present an overall mean reduction of 0.04 working days lost. This result does not reach standard levels of statistical significance when using a random effects model (95% CI −0.14 to 0.06) but becomes statistically significant when a fixed effects model is used (95% CI −0.06 to −0.01). This difference occurs due to the large variation in the size of the effect in individual trials, and consideration of the trials individually is probably more informative than the meta-analysis: of the four studies where the vaccine was a good match with the circulating virus, two reported large effects (MD −0.44 and −0.74, respectively) and two reported more modest effects (MD −0.08 and −0.04, respectively). All four results reached standard levels of statistical significance.

Patient safety perspective: effects on patients and clients

Six reviews report the impact of vaccinating HCWs on their patients or clients13 14 16 20–22 (table 5, see online supplementary appendix 8).

Table 5.

Vaccination effects in patients or clients of HCW (the patient safety perspective)

| Review ID | Patient group | Laboratory-confirmed influenza |

Clinically suspected influenza |

Other statistically significant effects | Review authors’ conclusions |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of studies (participants) | Efficacy (95% CI) | No. of studies (participants) | Efficacy | On efficacy | For policy | |||

| Burls et al13 | Those at risk. No further definition | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Deaths from all-cause mortality, OR=0.56, p=0.0013 | ‘Vaccination was highly effective’* | ‘Effective implementation should be a priority’† |

| Michiels et al14 | No further definition | Refers to 2010 version of Thomas et al21 | No statistically significant effect | Refers to 2010 version of Thomas et al21 | No statistically significant effect | Deaths from all-cause mortality Effectiveness=34% (95% CI 21 to 45) |

‘There is little evidence that immunisation is effective in protecting patients’ | ‘Should not be mandatory at present’ |

| Ferroni and Jefferson16 | People aged at least 60 years in long-term care facilities | Two RCTs Refers to 2011 version of Thomas et al21 |

No statistically significant effects | Refers to 2011 version of Thomas et al21 | 86% where some patients vaccinated to no significant effect where patients unvaccinated | Deaths from all-cause mortality, RR=0.66 (95% CI 0.55 to 0.79) (unadjusted) | ‘Influenza vaccination of healthcare workers and the older people in their care may be more effective at reducing influenza-like illness in older people living in institutions, although vaccination of healthcare workers alone may be no more effective’ | None stated |

| Ahmed et al22 | Patients in healthcare facilities. No further definition | Two RCTs (752) One observational study |

RCTs—No statistically significant effects Observational study (≥35% vs <35% vaccinated HCWs)—adjusted OR=0.07 (0.01 to 0.98) |

Three RCTs (7031) One observational study |

RCTs—42% (95% CI 27 to 54) Observational study—no significant effect |

Deaths from all-cause mortality, RR=0.71 (95% CI 0.59 to 0.85) | ‘Healthcare professional influenza vaccination can enhance patient safety’ | None stated |

| Dolan et al20 | At high risk of respiratory infection | Two RCTs (752), two observational studies (not stated) | RD 0.00 (−0.03 to 0.03) Observational studies found statistically significant effects |

Three RCTs (not stated) Two observational studies (not stated) |

RCTs and observational studies: statistically significant effects | Deaths from all-cause mortality, OR=0.68 (95% CI 0.55 to 0.84) (adjusted) | ‘A likely protective effect for patients’‡ | ‘The existing evidence base is sufficient to sustain current recommendations for vaccinating HCWs’ |

| Thomas et al21 | Aged >60 years living in institutions) | Two RCTs (752) | RD 0.00 (−0.03 to 0.03) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | ‘Did not identify a benefit of healthcare worker vaccination’† | ‘Does not provide reasonable evidence to support the vaccination of healthcare workers’ |

*Burns et al13 only present data on all-cause mortality from two cluster-RCTs. It reports that both trials found statistically significant effects but notes problems with the analysis in both trials.

†Thomas et al21 also report no statistically significant effects on hospitalisation or deaths due to lower respiratory tract infection. The authors chose not to present data on clinically suspected influenza or all-cause mortality as they doubt the validity of these measures when there is no effect on influenza.

‡This conclusion is based on statistically significant findings on clinically suspected influenza and all-cause mortality reported in an early version of Thomas et al21 but excluded from the most recent version of the review.20

HCW, healthcare worker; RCTs, randomised controlled trials; RD, risk difference; RR, relative risk.

Methodological quality of reviews: One of the two most recent reviews21 was of high methodological quality and had only minor limitations (table 3). The remaining reviews all have some major limitations.

Included studies: Thomas et al21 evaluated the effects of vaccinating HCW on people aged over 60 years living in residential care settings or hospitals and included four cluster-RCTs (7558 participants) and one cohort study (12 742 participants). Ahmed et al22 and Dolan et al23 evaluate the same four cluster-RCTs plus some additional observational studies. Burls et al13 only includes two of the cluster-RCTs included in Thomas et al,21 and Michiels et al14 and Ferroni and Jefferson16 summarise the findings of an earlier version of Thomas et al21 30

Results: Thomas et al21 reports absolute effect estimates close to zero for laboratory-confirmed influenza (risk difference (RD) 0.00, 95% CI −0.03 to 0.03; two trials, 752 participants), hospitalisation (RD 0.00, 95% CI −0.02 to 0.02; 1 trial, 3400 participants) and death due to lower respiratory tract infection (RD −0.02, 95% CI −0.06 to 0.02; 2 trials, 4459 participants). Thomas et al21 state that they chose not to present results on clinically suspected influenza and all-cause mortality because ‘these are not the effects the vaccines were produced to address' and give further reasons why they believe this is important in appendices. They did, however, include these outcomes in their previous version,30 and three of the other reviews simply refer to the results for these outcomes reported in the Cochrane review (Dolan 2012).14 16 Dolan et al23 also presents the results of three observational studies, which report statistically significant effects on clinically suspected influenza. Ahmed et al22 analyses the same four RCTs but includes the two additional outcomes with statistically significant and quantitatively important effects: a reduction in clinically suspected influenza of 42% (95% CI 27 to 54, 3 trials, 7031 participants) and a reduction in all-cause mortality of 29% (95% CI 15 to 41, 4 trials, 8468 participants).

Conclusions: Thomas et al21 and the earlier version of this Cochrane review concluded that they ‘did not identify a benefit of healthcare worker vaccination’. Dolan et al20 concludes a ‘likely protective effect for patients’ (based mainly on the outcomes of the earlier edition of the Cochrane review) and that the evidence base is ‘sufficient to sustain current policy’. Ahmed et al22 concludes vaccinating healthcare professionals ‘can enhance patient safety’.

Discussion

Occupational health perspective

The efficacy of influenza vaccination against laboratory-confirmed influenza is remarkably consistent across reviews, at around 60% in healthy adults. It seems reasonable to extrapolate this effect to HCWs (who are themselves often ‘healthy adults’), and indeed the single trial directly assessing efficacy in HCWs is consistent with this. Using the median efficacy of 62%, and the median risk of influenza in the control groups of 4%, vaccination would prevent ∼2.5 episodes of influenza per 100 HCW vaccinated (a NNV to prevent one case of influenza of around 40 (95% CI 36 to 52)). The decision about whether to offer vaccination to HCWs (figure 1; vaccine policy one) would then depend on a value judgement as to whether this effect was considered worthwhile and further evidence that the vaccine was safe, acceptable to HCWs and affordable to the health service.

Employer perspective

The most recent reviews in HCWs and all healthy adults present meta-analyses, which do not reach standard levels of statistical significance. However, these may be misleading due to either failure to include all the trials or the wide variation in effect size seen in the individual trials. While even the conservative estimate of four working days saved per 100 people vaccinated (taken from the latest Cochrane review) would inevitably reduce some disruption to the health workforce, estimates of how much this would save or cost the National Health Service are needed and are beyond the scope of this review.

Patient safety perspective

It is not unreasonable to postulate that vaccinating HCWs with an effective vaccine will reduce transmission of influenza to patients. However, the data available from trials, the data presented in reviews and the conclusions reached by authors are somewhat confusing. The best supportive evidence seems to come from analyses of VE against clinically suspected influenza and all-cause mortality, which were present in Ahmed et al22 and the 2010 version of the Cochrane review, although discounted in the conclusions reached and then removed from the latest version of the Cochrane review despite showing important effects. Although we accept that these outcomes have limitations, we are unsure if excluding them was the right decision, especially if trials are adequately blinded, and the data on laboratory-confirmed influenza are insufficient to exclude effects. In a fully transparent process, these data would be clearly presented alongside an evaluation of the certainty of the evidence (assessed by GRADE) for consideration by the reader or the guideline panel, rather than the authors simply deciding to exclude it.

The direct evidence (from systematic reviews of RCTs), for employer or patient safety effects which would lead to policy option two (framing high vaccination coverage as a professional responsibility), is nuanced and has suffered from being the subject of multiple systematic review teams, making different inferences from the same data. Occasionally, these authors have stepped beyond the brief of systematic reviews to make recommendations based on author judgements,31 which have only served to muddy the waters and add to the confusion surrounding vaccination. Evidence of effects from systematic reviews is only one component of evidence-informed policymaking, and judgements about the relative importance of different outcomes, or the clinical importance of estimated effects, are best made by a panel who adequately represent all important stakeholder groups, including patients, carers and HCWs, such as Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI).

Strengths and limitations of this paper

This paper did not aim to undertake an appraisal of the quality of evidence for each of the policy-relevant outcomes. This would have comprised doing our own systematic review, and clearly there are already enough of these. Rather we have concentrated on appraising the existing systematic reviews and unpicking the reasons for the inconsistencies between their conclusions. We also did not aim to make judgements or recommendations of our own, as we are not the right people to do so, and this would simply add to the confusion around vaccination. We would, however, encourage dialogue between the Cochrane review teams and the relevant policymakers to ensure that future editions include all the outcomes relevant to decision-making and a transparent appraisal of the quality of evidence using the GRADE approach.

We chose to include only systematic reviews in English, as these are most likely to have influenced HCWs and policymakers in the UK, although further reviews in other languages may exist and be important to policies elsewhere. We chose to restrict our analysis to inactivated parenteral vaccines where possible as this is what is recommended in the UK.

Conclusions

HCWs are increasingly used to seeing, and demanding to see, the evidence base for the healthcare interventions they are asked to provide or make themselves subject to. Consequently, influenza vaccination uptake may benefit from a fully transparent guideline process, which makes explicit the underlying rationale, evidence base, values, preferences and judgements, which inform the current or future policy. This process would draw on all available direct evidence from systematic reviews and the most up-to-date research but may also use indirect evidence such as health system data on working days lost due to influenza.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Merav Kliner at @meravkliner

Contributors: SG initiated the development of this paper. All authors had substantial contributions to conception and design of the paper and interpretation of the data. MK and AK collected and analysed the data. PG proposed the appraisal structure, and DS developed the conceptual framework. MK drafted the manuscript, and all authors contributed to developing the manuscript. All authors have given final approval of the version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. MK is responsible for the overall content as guarantor. MK affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained. All authors, external and internal, had full access to all of the data (including statistical reports and tables) in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding: PG and DS are partly supported by the Effective Health Care Research Consortium. This Consortium is funded by UK aid from the UK Government for the benefit of developing countries (grant: 5242). The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect UK government policy. Public Health England paid the open access fees for publication.

Competing interests: MK, AK and SG are employed by Public Health England; PG has an honorary contract with Public Health England and PG and DS are employed by a grant that supports Cochrane.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Department of Health, Public Health England, NHS England. The national flu immunisation programme 2014/15 (updated 28 April 2014; cited 3 December 2014). https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/316007/FluImmunisationLetter2014_accessible.pdf

- 2.Public Health England, NHS England. Seasonal flu vaccine uptake in healthcare workers: 1 September 2015 to 31 January 2016 (published 18 February 2016). https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/seasonal-flu-vaccine-uptake-in-healthcare-workers-1-september-2015-to-31-january-2016 (accessed 25 May 2016).

- 3.British Medical Association. BMA criticises staff flu-jab funding link (updated 9 October 2014; cited 18 May 2016). http://www.bma.org.uk/news-views-analysis/news/2014/october/bma-criticises-staff-flu-jab-funding-link

- 4.Public Health England. Seasonal influenza vaccine uptake amongst frontline healthcare workers (HCWs) in England Winter season 2015 to 2016 (updated May 2016; cited 26 May 2016). https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/526041/Seasonal_influenza_vaccine_uptake_HCWs_2015_16_Annual_Report.pdf

- 5.Public Health England, NHS England. Flu plan: winter 2015 to 2016. (updated March 2015; cited 17 September 2015). https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/418038/Flu_Plan_Winter_2015_to_2016.pdf

- 6.Hollmeyer HG, Hayden F, Poland G et al. . Influenza vaccination of health care workers in hospitals—a review of studies on attitudes and predictors. Vaccine 2009;27:3935–44. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.03.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCartney M. Show us the evidence for the flu jab. Pulse Today. 19 October 2011 (cited 7 August 2014). http://www.pulsetoday.co.uk/show-us-the-evidence-for-the-flu-jab/12911759.article.

- 8.McCartney M. What use is mass flu vaccination? BMJ 2014;349:g6182 10.1136/bmj.g6182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doshi P. Influenza: marketing vaccine by marketing disease. BMJ 2013;346:f3037 10.1136/bmj.f3037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Department of Health, Public Health England, NHS England. The national flu immunisation programme 2015 to 2016: supporting letter (updated 27 March 2015, cited 17 September 2015). https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/418428/Annual_flu_letter_24_03_15__FINALv3_para9.pdf

- 11.Shea B, Bouter L, Peterson J et al. . External validation of a measurement tool to assess systematic Reviews (AMSTAR). PLoS One 2007;2:e1350 10.1371/journal.pone.0001350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ng AN, Lai CK. Effectiveness of seasonal influenza vaccination in healthcare workers: a systematic review. J Hosp Infect 2011;79:279–86. 10.1016/j.jhin.2011.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burls A, Jordan R, Barton P et al. . Vaccinating healthcare workers against influenza to protect the vulnerable—is it a good use of healthcare resources? A systematic review of the evidence and an economic evaluation. Vaccine 2006;24:4212–21. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.12.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Michiels B, Govaerts F, Remmen R et al. . A systematic review of the evidence on the effectiveness and risks of inactivated influenza vaccines in different target groups. Vaccine 2011;29:9159–70. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DiazGranados CA, Denis M, Plotkin S. Seasonal influenza vaccine efficacy and its determinants in children and non-elderly adults: a systematic review with meta-analyses of controlled trials. Vaccine 2012;31:49–57. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.10.084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferroni E, Jefferson T. Influenza. Clin Evid (Online) 2011:pii 0911. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Osterholm MT, Kelley NS, Sommer A et al. . Efficacy and effectiveness of influenza vaccines: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2012;12:36–44. 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70295-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Villari P, Manzoli L, Boccia A. Methodological quality of studies and patient age as major sources of variation in efficacy estimates of influenza vaccination in healthy adults: a meta-analysis. Vaccine 2004;22:3475–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Demicheli V, Jefferson T, Al-Ansary L et al. . Vaccines for preventing influenza in healthy adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;(3):CD001269 10.1002/14651858.CD001269.pub5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dolan GP, Harris RC, Clarkson M et al. . Vaccination of healthcare workers to protect patients at increased risk of acute respiratory disease: summary of a systematic review. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2013;7(Suppl 2):93–6. 10.1111/irv.12087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomas RE, Jefferson T, Lasserson TJ. Influenza vaccination for healthcare workers who care for people aged 60 or older living in long-term care institutions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;(7):CD005187 10.1002/14651858.CD005187.pub4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahmed F, Lindley MC, Allred N et al. . Effect of influenza vaccination of healthcare personnel on morbidity and mortality among patients: systematic review and grading of evidence. Clin Infect Dis 2014;58:50–7. 10.1093/cid/cit580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dolan GP, Harris RC, Clarkson M et al. . Vaccination of health care workers to protect patients at increased risk for acute respiratory disease. Emerg Infect Dis 2012;18:1225–34. 10.1071/HI08003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Michiels B, Philips H, Coenen S et al. . The effect of giving influenza vaccination to general practitioners: a controlled trial. BMC Med 2006;4:17 10.1186/1741-7015-4-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilde J, McMillan J, Serwint J et al. . Effectiveness of influenza vaccine in health care professionals: a randomized trial. JAMA 1999;281:908–13. 10.1001/jama.281.10.908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weingarten S, Staniloff H, Ault M et al. . Do hospital employees benefit from the influenza vaccine? A placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Gen Intern Med 1988;3:32–7. 10.1007/BF02595754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saxén H, Virtanen M. Randomized, placebo-controlled double blind study on the efficacy of influenza immunization on absenteeism of health care workers. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1999;18:779–83. 10.1097/00006454-199909000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hui L, Rashwan H, bin Jaafar M et al. . Effectiveness of influenza vaccine in preventing influenza-like illness among Faculty of Dentistry staff and students in University Kebangsaan Malaysia. Healthc Infect 2008;13:4–9. 10.1071/HI08003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jefferson T, Di Pietrantonj C, Rivetti A et al. . Vaccines for preventing influenza in healthy adults. Cochrane Database Sys Rev 2010;(7):CD001269 10.1002/14651858.CD001269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomas R, Jefferson T, Lasserson T. Influenza vaccination for healthcare workers who work with the elderly. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;(2):CD005187 10.1002/14651858.CD005187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cochrane Handbook. Chapter 12: Interpreting results and drawing conclusions (cited 8 October 2014). http://handbook.cochrane.org/v5.0.0/chapter_12/12_interpreting_results_and_drawing_conclusions.htm.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-012149supp_appendices.pdf (758.2KB, pdf)