Abstract

Objective

To investigate whether the circadian rhythm disruption following the transition into and out of daylight saving time (DST) is associated with an increased risk of spontaneous delivery.

Design

We compared the number of spontaneous deliveries in the Swedish Medical Birth Register during the week after the change to and the week after the change from DST (exposure periods) with the average number of spontaneous deliveries in the control period, defined as the week before and the week after each exposure period.

Setting

Sweden, 1993–2006.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The primary outcomes were the weekly and the daily number of spontaneous deliveries in the exposure and the control periods. In secondary analyses we also compared the mean length of pregnancy of the women with spontaneous deliveries in the exposure and control periods.

Results

The number of deliveries during the week after the transition into or out of DST was similar to that in the comparison period (18 519 observed vs 18 434 expected in case of the spring shift and 19 073 observed vs 19 122 expected in case of the autumn shift); the corresponding incidence ratio and 95% CIs were 1.005 (0.990 to 1.019) and 0.997 (0.983 to 1.012), respectively. There were no differences in the length of gestation of the deliveries in the exposure and the control periods.

Conclusions

Our results do not support the hypothesis that a minor circadian rhythm disruption is associated with an increased short-term risk of spontaneous delivery.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY, PUBLIC HEALTH

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The transitions into and out of daylight saving time (DST) disrupt the circadian rhythm and may be regarded as natural experiments that allow studying the effect of externally induced minor sleep disturbances on the cascade of events that may lead to spontaneous delivery.

This was the first study to investigate whether the risk of spontaneous delivery increases in the days following the change to and from DST.

The coverage of our study population, the Swedish Medical Birth Register, is virtually complete, statistical power is enormous and we had the possibility to separate spontaneous from medically indicated deliveries.

Since information on sleep quantity and quality prior to delivery is not recorded, we do not know to what extent each studied woman was actually affected by the DST transition.

Our findings may be generalised only to populations living at similar latitudes and with comparable sleep habits to those of the women included in our study.

Introduction

What initiates human parturition remains one of the important and unanswered questions of reproductive epidemiology.1 Emerging, though not consistent, evidence suggests a role for stress hormones, placental corticotrophin releasing hormone in particular, in the initiation of human parturition.2 3 Sleep deprivation and circadian disruption may elevate stress hormone levels4 5 and may induce proinflammatory activity,6–8 which—through a feedforward mechanism—potentiate the effect of prostaglandins and oxytocin on uterine contractions,2 3 rupture of membranes and the onset of spontaneous labour. We are only aware of one study that investigated whether disturbed sleep may trigger spontaneous delivery.9 It reported a 4.5-fold increased risk of disturbed sleep in the 24 hours before the onset of spontaneous preterm delivery compared to the control period 48–72 hours earlier.9 To what extent the association between sleep disturbance and the acute increased risk of preterm delivery was due to reverse causation—that is, that prodromal symptoms of delivery impaired sleep—could not be determined.9

The transitions into and out of daylight saving time (DST), that is, the switch of the clocks forward by 1 hour in the spring and backward by 1 hour in the autumn, may be regarded as natural experiments that allow studying the effect of externally induced minor sleep disturbances on health.10 11 These transitions disrupt the circadian rhythm and may induce adverse changes in sleep quality and quantity that persist for several days;10 12–18 for most individuals the alignment to the new time takes up to 5–7 days,10 12 13 though there is some individual variation in adjustment.10 16 Several studies suggest that DST transitions may impair mood19 and may increase the short-term risk of acute myocardial infarction,11 20–23 accidents and injuries.17 24–28 However, other investigations found no effect of DST shifts on seeking care for psychiatric conditions,29 30 risks of accidents or injuries.30–33

It has been hypothesised that the transition into DST is more disruptive on the circadian rhythm than the transition out of DST.16 18 The turn of the clocks forward in the spring results in a shortening of the day with 1 hour and may result in reduced sleep.14 17 The turn of the clocks backward during the autumn increases the length of the day and may be accompanied by longer sleep, though empirical evidence suggests that this does not necessarily happen.10 A misalignment between the individual's biological clock and the social clock (a delay in the biological clock after the spring transition and a phase advance after the autumn shift) may be present following both shifts.12 16 18 In line with this hypothesis regarding dose–response effects, several studies found stronger effects of the DST shift on sleep quality,16 18 acute myocardial infarction11 20 22 or accidents and injuries17 26 28 in spring than in autumn. Nevertheless, other studies, the majority investigating risk of injuries or accidents following DST transitions, found no effects23 28 31–33 or no difference in effects between shifts.21 25 34

To the best of our knowledge, the effect of the DST shifts on the onset of spontaneous delivery has not been investigated. We used information from the Swedish Medical Birth Register to analyse whether the risk of spontaneous delivery increases in the days following the change to and from DST.

Methods

Data source

We used information on births recorded in the Swedish Medical Birth Register during 1993–2006 (n=1 350 229). The register contains information on almost 99% of all deliveries in the country since 1973.35 Mode of delivery onset is recorded in checkboxes since 1990 as (1) caesarean section before onset of labour, (2) induced labour because of maternal or fetal concerns or (3) spontaneous onset of labour. Deliveries with spontaneous onset of labour or with a diagnosis of preterm premature rupture of membranes were considered spontaneous; diagnoses of preterm premature rupture of membranes were identified using the International Classification of Diseases 9th revision code 658B and 10th revision code O42, respectively. The completeness of the information on mode of delivery onset increased gradually; information on mode of delivery onset was available in 45% of births in 1990, 88.8% in 1991, 92.9% in 1992 and between 96.5% and 99.5% during 1993–2006. Analyses were therefore restricted to deliveries during 1993–2006.

Exposure

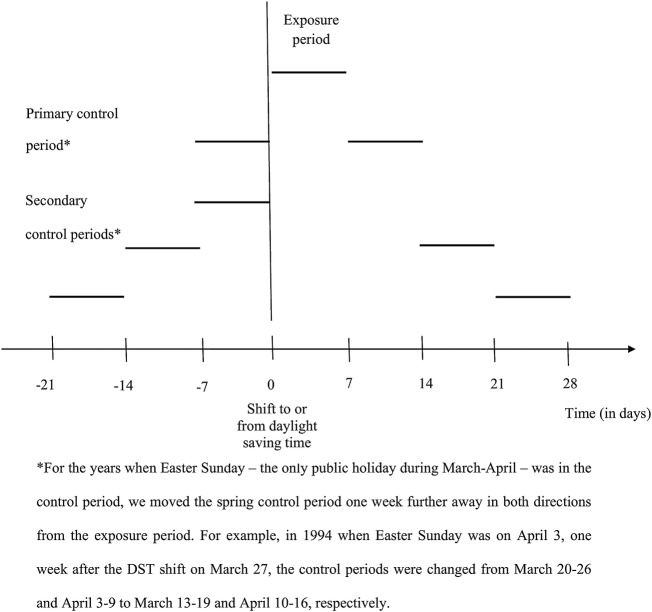

Spring shift: We defined the spring exposure period as the first 7 days after the turn of the clocks 1 hour forward, which occurred on the last Sunday of March during all studied years. Our choice for 1 week length was based on the findings from earlier studies suggesting that for most individuals the adjustment to the new social time takes up to 5–7 days.10 12 13 A larger proportion of pregnancies are likely to be conceived during vacation time than during non-vacation time.36 To consider the possibility that differences between the number of deliveries in the exposure and in the control periods may be due to differences in vacation status at the time of conception (ie, summer vacation at the time of conception in case of deliveries around the spring shift, and winter vacation at the time of conception for those with deliveries around the end of September), we defined the primary control period as the week before and the week after the exposure period; the symmetric design increased comparability between the exposure and the control period also with respect to temperature and weather conditions. Nevertheless, to consider the possibility that the adjustment period takes more than 1 week, we also defined three secondary control periods: (1) the week that was 2 weeks before and the week that was 2 weeks after the exposure period, (2) the week that was 3 weeks before and the week that was 3 weeks after the exposure period and (3) the week that proceeded the exposure period (figure 1). For the years when the Easter Sunday—the only public holiday during March–April—was in the control period, we moved the control period 1 week further away in both directions from the exposure period (figure 1). The proportion of deliveries with missing information on the mode of delivery onset was 2.3% in the spring exposure period and 2.1% in the corresponding primary control period.

Figure 1.

Definition of the exposure and control periods.

Autumn shift: The autumn exposure period was defined as the 7 days after the turn of the clocks 1 hour backward; this occurred on the last Sunday of September during 1993–1995 and on the last Sunday of October during 1996–2006. The primary and the secondary autumn control periods were defined as in case of the spring shift (figure 1). The proportion of deliveries with missing information on the mode of delivery onset was 1.7% in the autumn exposure period and 1.9% in the corresponding primary control period.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes were the weekly and the daily number of spontaneous deliveries in the exposure and the control periods. To further consider the possibility that differences between the number of deliveries in the exposure and in the control periods may be due to differences in vacation at the time of conception, we also compared the mean length of pregnancy of the women who delivered during the control and the exposure periods.

Gestational age was generally estimated using ultrasound scans performed early in the second trimester.37 All pregnant women in Sweden are invited to attend this examination free of charge and ∼95% accept this offer.38 When data from the ultrasound examination were not available, gestational age was estimated based on the last menstrual period.37 Deliveries occurring before the completion of the 37th week of gestation were considered preterm.

Other variables

Information on parity, maternal age at delivery and the number of fetuses at delivery was obtained from the Medical Birth Register.

Statistical analyses

To obtain incidence ratios (IRs), we divided the observed number of spontaneous deliveries after the DST shifts with their expected number. The expected number was the mean number of deliveries during the control periods before and after the shifts. The method suggested by Sun et al39 was used to calculate 95% CIs for IRs. As the Sunday of the transition into DST is only 23 hours, we multiplied the observed number of deliveries for this day by 1.043 (ie, 24/23). Accordingly, we divided the number of deliveries on the Sunday of transition out of DST by 1.042 (ie, 25/24). In the primary analyses concerning the spring change we excluded the 3 years when the DST spring shift coincided with Easter Sunday (1997, 2002 and 2005). However, we performed secondary analyses when deliveries during the years when the post-transition Sunday was on Easter Sunday were not excluded.

We conducted several stratified analyses to examine effect modification by (1) maternal age at delivery (<35 vs ≥35 years), (2) parity (primiparous vs multiparous), (3) the number of fetuses in the pregnancy (singleton or twin delivery) and (4) in case of the autumn shift by year (1993–95, ie, when the shift was on the last Sunday in September vs 1996–2006, ie, when the shift was on the last Sunday of October). In addition, we performed analysis restricted to spontaneous preterm deliveries.

Mean gestational age for deliveries during the weeks after the transitions and during control periods were compared using independent sample t-tests.

Results

Spring shift

The number of deliveries during the week after the transition into DST was similar to the mean number of deliveries in the week before and the week after this week (18 519.2 observed vs 18 433.5 expected; table 1). The corresponding IR and 95% CIs was 1.005 (0.990 to 1.019). The mean number of deliveries on specific days of the week did not substantially differ between the exposure and the primary control periods.

Table 1.

Risk ratios comparing the number of spontaneous deliveries in the week after the transition into daylight saving time (spring) with the mean number of spontaneous deliveries in the week before and the week after this period

| Number of spontaneous deliveries |

RR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Comparison unit | Observed* | Expected† | |

| Whole week | 18 519.2 | 18 433.5 | 1.005 (0.990 to 1.019) |

| Sunday‡ | 2549.2 | 2563.5 | 0.994 (0.956 to 1.034) |

| Monday | 2774.0 | 2733.0 | 1.015 (0.978 to 1.053) |

| Tuesday | 2716.0 | 2700.0 | 1.006 (0.968 to 1.044) |

| Wednesday | 2739.0 | 2693.5 | 1.017 (0.979 to 1.056) |

| Thursday | 2621.0 | 2658.0 | 0.986 (0.949 to 1.025) |

| Friday | 2609.0 | 2604.5 | 1.002 (0.964 to 1.041) |

| Saturday | 2511.0 | 2481.0 | 1.012 (0.973 to 1.052) |

*Observed is the number of spontaneous deliveries during the week following the spring transition.

†Expected is the number of spontaneous deliveries during the week before and the week after the week following the spring transition divided by two.

‡The number of deliveries on the Sunday following the transition into daylight saving time was adjusted for the shorter day length (23 instead of 24 hours).

CI, confidence interval; RR, risk ratio.

Gestational age of the deliveries in the exposure and control period was also similar (table 2).

Table 2.

Mean gestational age for women with spontaneous deliveries in the spring exposure and primary control periods*

| Comparison unit | Exposure period |

Comparison period |

p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of deliveries | Mean gestational age (SD) in days | Number of deliveries | Mean gestational age (SD) in days | ||

| Whole week | 18 387 | 279.0 (12.1) | 36 835 | 278.9 (12.4) | 0.48 |

| Sunday | 2441 | 279.0 (12.3) | 5125 | 278.8 (12.6) | 0.72 |

| Monday | 2772 | 279.0 (12.2) | 5460 | 279.0 (12.4) | 0.99 |

| Tuesday | 2715 | 278.7 (12.6) | 5396 | 278.6 (13.1) | 0.78 |

| Wednesday | 2735 | 279.0 (11.8) | 5381 | 279.2 (11.7) | 0.60 |

| Thursday | 2616 | 278.8 (12.9) | 5311 | 278.9 (12.2) | 0.69 |

| Friday | 2600 | 279.2 (11.4) | 5201 | 278.8 (12.2) | 0.16 |

| Saturday | 2508 | 279.1 (11.3) | 4961 | 278.8 (12.3) | 0.37 |

*Only deliveries with data on gestational age are included.

Results were not substantially different (1) when deliveries during the years when the post-transition Sunday was on Easter Sunday were not excluded (data not shown), (2) when comparing the numbers (see online supplementary table 1) and the mean gestational age (data not shown) of the spontaneous deliveries in the exposure and the three secondary control periods. We found no evidence for effect modification by maternal age at delivery (<35 vs ≥35 years), parity (primiparous vs multiparous) or the number of fetuses in the pregnancy (singleton vs multiple pregnancy) when comparing the number of deliveries in the exposure and the primary control period. When restricting analyses to spontaneous preterm deliveries, we observed no substantial difference in the number of deliveries in the exposure and the primary control period (see online supplementary table 2).

bmjopen-2015-010925supp_tables.pdf (187.7KB, pdf)

Autumn shift

The number of deliveries in the week following the transition out of DST was similar to the mean number of deliveries in the week before and the week after this week (19 072.9 observed vs 19 122.0 expected; table 3). The corresponding IR (95% CI) was 0.997 (0.983 to 1.012). We observed no consistent trend when looking separately at the different days after the shift.

Table 3.

Risk ratios comparing the number of spontaneous deliveries in the weeks after the transition out of daylight saving time (autumn) with the mean number of spontaneous deliveries in the week before and the week after this period

| Comparison unit | Number of spontaneous deliveries |

RR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Observed* | Expected† | ||

| Whole week | 19 072.9 | 19 122.0 | 0.997 (0.983 to 1.012) |

| Sunday‡ | 2617.9 | 2703.5 | 0.968 (0.932 to 1.006) |

| Monday | 2841.0 | 2862.0 | 0.993 (0.956 to 1.030) |

| Tuesday | 2720.0 | 2782.5 | 0.978 (0.941 to 1.015) |

| Wednesday | 2708.0 | 2770.0 | 0.978 (0.941 to 1.015) |

| Thursday | 2812.0 | 2685.0 | 1.047 (1.009 to 1.087) |

| Friday | 2690.0 | 2755.5 | 0.976 (0.940 to 1.014) |

| Saturday | 2684.0 | 2563.5 | 1.047 (1.008 to 1.087) |

*Observed is the number of spontaneous deliveries during the week following the autumn transition.

†Expected is the number of spontaneous deliveries during the week before and the week after the week following the spring transition divided by two.

‡The number of deliveries on the Sunday following the transition out of daylight saving time was adjusted for the longer day length (25 instead of 24 hours).

CI, confidence interval; RR, risk ratio.

The mean length of gestation of the deliveries was also similar with that of the deliveries on the corresponding weekdays in the control period (table 4).

Table 4.

Mean gestational age for women with spontaneous deliveries in the autumn exposure and primary control periods*

| Comparison unit | Exposure period |

Comparison period |

p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of deliveries | Mean gestational age (SD) in days | Number of deliveries | Mean gestational age (SD) in days | ||

| Whole week | 19 149 | 279.1 (12.5) | 38 214 | 279.0 (12.6) | 0.59 |

| Sunday | 2722 | 279.0 (12.3) | 5404 | 279.0 (12.1) | 0.96 |

| Monday | 2835 | 279.2 (12.4) | 5721 | 279.1 (12.3) | 0.65 |

| Tuesday | 2715 | 279.0 (12.8) | 5558 | 279.2 (12.3) | 0.65 |

| Wednesday | 2703 | 279.3 (12.2) | 5536 | 279.1 (12.9) | 0.49 |

| Thursday | 2804 | 279.1 (12.5) | 5365 | 279.0 (13.4) | 0.67 |

| Friday | 2687 | 278.8 (13.0) | 5508 | 279.0 (13.0) | 0.51 |

| Saturday | 2683 | 279.3 (12.5) | 5122 | 279.0 (12.5) | 0.33 |

*Only deliveries with data on gestational age are included.

Results were similar to those from the primary analyses when comparing the number (see online supplementary table 3) and the mean gestational age (data not shown) of the spontaneous deliveries in the exposure period to that in the three secondary control periods. We found no evidence for effect modification by maternal age at delivery (<35 vs ≥35 years), parity (primiparous vs multiparous) or the number of fetuses in the pregnancy (singleton vs multiple pregnancy) when comparing the number of deliveries in the exposure and the primary control period. Similarly, results from the main analysis were essentially the same when we compared the years when the autumn shift was on the last Sunday in September (1993–1995) with the years when the autumn shift was on the last Sunday in October (1996–2006). When restricting analyses to spontaneous preterm deliveries, we observed no substantial difference in the number of deliveries in the exposure and the primary control period (see online supplementary table 4).

Discussion

We found no differences in the number of spontaneous deliveries in the week following the transition into or out of DST compared to the mean number of spontaneous deliveries in the corresponding control periods. The mean gestational age for spontaneous deliveries during the exposure week was largely similar to those from the control period.

We are not aware of any previous study analysing whether sleep disturbance may increase the short-term risk of spontaneous term delivery. In a case-crossover study, Hernández-Díaz et al9 reported that disturbed sleep was 4.5-fold more common in the 24 hours before the onset of spontaneous preterm delivery than in the control period 48–72 hours earlier. One of the possible explanations for the discrepancy between the findings from our study and the earlier study is that sleep disruption was externally imposed in our study, while in the other investigation the sleep disturbance is likely to have been induced—at least for some women—by the symptoms of imminent preterm delivery. Second, the sleep disruptions the pregnant women involved in our study are likely to have experienced subsequent to the DST transitions are likely to have been milder than the sleep disturbance women reported in the study of Hernández-Díaz et al.9 Although several investigations in predominantly non-pregnant samples suggest that the transition into and out of DST may disrupt the circadian rhythm for several days,12 14–16 18 it is unclear whether these findings may be generalised to women in late pregnancy, a period characterised by important alterations in sleep patterns and neuroendocrine activity. Women's perception of stress40 41 and their physiological reactivity to stress42 may decrease with advancing pregnancy.43 Furthermore, some women in our study may have already been on parental leave at the time of the studied transition and thus may have been less connected to social time and less affected by the DST shift than working individuals.19 The possibility that there may be a threshold effect between the activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA)-axis and the acute risk of spontaneous delivery44–46 and that a more severe chronobiological disruption than what we investigated may be important for triggering the onset of spontaneous delivery cannot be excluded.

The main strengths of our investigation are related to the design of the study and to the high quality of the data recorded in the Swedish Medical Birth Register. The shifts to and from DST may be regarded as natural experiments that allow investigating the acute effects of externally imposed modest circadian rhythm disruptions10 11 on the cascade of events that may lead to the onset of spontaneous delivery. This design excludes the possibility of reverse causation, a potential problem in the only previous study investigating sleep disturbance as a trigger of spontaneous preterm birth.9 Since the whole population was exposed at a certain timepoint, confounding by personal characteristics is not likely. Differences in weather conditions between exposure and control periods are likely to even out during the 14 years of the study period. The only factor—besides the disruption of the chronobiological rhythm—we could hypothesise to consistently affect the probability of delivery onset in the control week and exposure week is vacation status at the time of conception. Many Swedes start summer vacation in late June or early July, that is, ∼9 months prior the spring DST shift; conceptions are more likely to occur during the summer vacation than in other periods, as the highest number of children in Sweden are born during March, April and May.36 Taking vacation in late December and early January, that is, 9 months before the clock shift in September, is also common in Sweden. Our primary analysis with the control weeks chosen symmetrically as close as possible to the exposure week suggested no consistent effect of DST on the number of spontaneous deliveries; furthermore, the length of gestation was not shorter for deliveries in the exposure week compared to any of the control weeks, that is, DST did not seem to bring the time of some deliveries forward. A second strength of our study is that the coverage of the Swedish Medical Birth Register is virtually complete, statistical power is enormous and we had the possibility to separate spontaneous from medically indicated deliveries.

Our study also has limitations. First, since information on sleep quantity and quality prior to delivery is not recorded, we do not know to what extent each studied woman was actually affected by the DST transition. Previous studies suggest that, though there is individual variation in the adaptation to DST shifts (depending on eg, age and chronotype),10 16 the circadian rhythm adjustment to the new social time takes usually up to 5–7 days.10 12 13 Second, we did not have information on circadian parameters related to the initiation of spontaneous delivery and duration of labour, thus we could not study whether DST shifts induced changes in the light–dark cycle may affect the circadian phasing and length of parturition.47 Third, as we did not have information on the date of delivery onset, we used data on the date of delivery. We expect that the vast majority of women gave birth within 1 or 2 days from the onset of spontaneous labour or the rupture of membranes. This could have led to a potential delay and dilution of the observed effect of DST. Fourth, our findings may be generalised only to populations living at similar latitudes and with comparable sleep habits to those of the women included in our study. Some earlier investigations regarding the effect of DST shifts on for example, acute myocardial infarction suggest milder effects in Sweden than in countries at lower geographical latitudes.11 20–22 Further studies are needed to investigate whether the effect of DST shifts on the risk of spontaneous delivery may vary by geographical latitude.

In conclusion, our findings do not support the hypothesis that a minor circadian rhythm disruption increases the short-term risk of spontaneous delivery. Further studies are needed to investigate whether more severe disturbances of the circadian rhythm may trigger spontaneous delivery.

Footnotes

Contributors: KDL contributed to the conception and the design of the study, to the analysis and the interpretation of data and to the writing of the manuscript. SC contributed to data acquisition, to the design of the study, to interpretation of the results and revised the paper. IJ contributed to the conception and the design of the study, to analysis and interpretation of data and to the writing of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Karolinska Institutet Research Foundation grant number 2014p4re42944 and the Rut and Arvid Wolff Memorial Foundation for Insomnia Research, Sweden grant number 2-1196/2015.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee at Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Wilcox AJ. Fertility and pregnancy. An epidemiologic perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.McLean M, Bisits A, Davies J et al. . A placental clock controlling the length of human pregnancy. Nat Med 1995;1:460–3. 10.1038/nm0595-460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith R. Parturition. N Engl J Med 2007;356:271–83. 10.1056/NEJMra061360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spiegel K, Leproult R, Van Cauter E. Impact of sleep debt on metabolic and endocrine function. Lancet 1999;354:1435–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01376-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhong X, Hilton HJ, Gates GJ et al. . Increased sympathetic and decreased parasympathetic cardiovascular modulation in normal humans with acute sleep deprivation. J Appl Physiol 2005;98:2024–32. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00620.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meier-Ewert HK, Ridker PM, Rifai N et al. . Effect of sleep loss on C-reactive protein, an inflammatory marker of cardiovascular risk. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;43:678–83. 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.07.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vgontzas AN, Zoumakis E, Bixler EO et al. . Adverse effects of modest sleep restriction on sleepiness, performance, and inflammatory cytokines. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004;89:2119–26. 10.1210/jc.2003-031562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laugsand LE, Vatten LJ, Bjørngaard JH et al. . Insomnia and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein: the HUNT study, Norway. Psychosom Med 2012;74:543–53. 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31825904eb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hernández-Díaz S, Boeke CE, Romans AT et al. . Triggers of spontaneous preterm delivery--why today? Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2014;28:79–87. 10.1111/ppe.12105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harrison Y. The impact of daylight saving time on sleep and related bahaviours. Sleep Med Rev 2013;17:285–92. 10.1016/j.smrv.2012.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Janszky I, Ahnve S, Ljung R et al. . Daylight saving time shifts and incidence of acute myocardial infarction--Swedish Register of Information and Knowledge About Swedish Heart Intensive Care Admissions (RIKS-HIA). Sleep Med 2012;13:237–42. 10.1016/j.sleep.2011.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monk TH, Folkard S. Adjusting to the changes to and from daylight saving time. Nature 1976;261:688–9. 10.1038/261688a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Monk TH, Aplin LC. Spring and autumn daylight saving time changes: studies of adjustment in sleep timings, mood, and efficiency. Ergonomics 1980;23:167–78. 10.1080/00140138008924730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lahti TA, Leppämäki S, Lönnqvist J et al. . Transition to daylight saving time reduces sleep duration plus sleep efficiency of the deprived sleep. Neurosci Lett 2006;406:174–7. 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.07.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lahti TA, Leppämäki S, Lönnqvist J et al. . Transitions into and out of daylight saving time compromise sleep and the rest-activity cycles. BMC Physiol 2008;8:3 10.1186/1472-6793-8-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kantermann T, Juda M, Merrow M et al. . The human circadian clock's seasonal adjustment is disrupted by daylight saving time. Curr Biol 2007;17:1996–2000. 10.1016/j.cub.2007.10.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barnes CM, Wagner DT. Changing to daylight saving time cuts into sleep and increases workplace injuries. J Appl Psychol 2009;94:1305–17. 10.1037/a0015320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tonetti L, Erbacci A, Fabbri M et al. . Effects of transitions into and out of daylight saving time on the quality of the sleep/wake cycle: an actigraphic study in healthy university students. Chronobiol Int 2013;30:1218–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kountouris Y, Remoundou K. About time: daylight saving time transition and individual well-being. Econ Lett 2014;122:100–3. 10.1016/j.econlet.2013.10.032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Janszky I, Ljung R. Shifts to and from daylight saving time and incidence of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1966–8. 10.1056/NEJMc0807104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Čulić V. Daylight saving time transitions and acute myocardial infarction. Chronobiol Int 2013;30:662–8. 10.3109/07420528.2013.775144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiddou MR, Pica M, Boura J et al. . Incidence of myocardial infarction with shifts to and from daylight savings time. Am J Cardiol 2013;111:631–5. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kirchberger I, Wolf K, Heier M et al. . Are daylight saving time transitions associated with changes in myocardial infarction incidence? Results from the German MONICA/KORA Myocardial Infarction Registry. BMC Public Health 2015;15:778 10.1186/s12889-015-2124-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Monk TH. Traffic accident increases as a possible indicant of desynchronosis. Chronobiologia 1980;7:527–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hicks RA, Lindseth K, Hawkins J. Daylight saving-time changes increase traffic accidents. Percept Mot Skills 1983;56:64–6. 10.2466/pms.1983.56.1.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coren S. Daylight savings time and traffic accidents. N Engl J Med 1996;334:924 10.1056/NEJM199604043341416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coren S. Accidental death and the shift to daylight savings time. Percept Mot Skills 1996;83:921–2. 10.2466/pms.1996.83.3.921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morassaei S, Smith PM. Switching to daylight saving time and work injuries in Ontario, Canada: 1993–2007. Occup Environ Med 2010;67:878–80. 10.1136/oem.2010.056127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shapiro CM, Blake F, Fossey E et al. . Daylight saving time in psychiatric illness. J Affect Disord 1990;19:177–81. 10.1016/0165-0327(90)90089-Q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lahti TA, Haukka J, Lönnqvist J et al. . Daylight saving time transitions and hospital treatments due to accidents or manic episodes. BMC Public Health 2008b;8:74 10.1186/1471-2458-8-74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lambe M, Cummings P. The shift to and from daylight savings time and motor vehicle crashes. Accid Anal Prev 2000;32:609–11. 10.1016/S0001-4575(99)00088-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lahti T, Nysten E, Haukka J et al. . Daylight saving time transitions and road traffic accidents. J Environ Public Health 2010;2010:657167 10.1155/2010/657167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lahti T, Sysi-Aho J, Haukka J et al. . Work-related accidents and daylight saving time in Finland. Occup Med (Lond) 2011;61:26–8. 10.1093/occmed/kqq167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hicks GJ, Davis JW, Hicks RA. Fatal alcohol-related traffic crashes increase subsequent to changes to and from daylight savings time. Percept Mot Skills 1998;86:879–82. 10.2466/pms.1998.86.3.879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.National Board of Health and Welfare. The Swedish Medical Birth Register. A summary of content and quality 2003. http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/Lists/Artikelkatalog/Attachments/10655/2003-112-3_20031123.pdf (accessed 5 May 2014).

- 36.http://data.un.org/Data.aspx?d=POP&f=tableCode:55 (accessed 27 Nov 2015).

- 37.National Board of Health and Welfare. Graviditeter, förlossningar och nyfödda barn. Medicinska födelseregistret 1973–2008. Assisterad befruktning 1991–2007 2009. http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/Lists/Artikelkatalog/Attachments/17862/2009-12-11.pdf (accessed 10 Dec 2014).

- 38.Høgberg U, Larsson N. Early dating by ultrasound and perinatal outcome. A cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1997;76:907–12. 10.3109/00016349709034900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun T, Ono Y, Takeuchi Y. A simple method for calculating the exact confidence interval of the standardized mortality ratio with an SAS function. J Occup Health 1996;38:196–7. 10.1539/joh.38.196 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Glynn LM, Wadhwa PD, Dunkel-Schetter C et al. . When stress happens matters: effects of earthquake timing on stress responsivity in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2001;184:637–42. 10.1067/mob.2001.111066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Glynn LM, Schetter CD, Wadhwa PD et al. . Pregnancy affects appraisal of negative life events. J Psychosom Res 2004;56:47–52. 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00133-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Entringer S, Buss C, Shirtcliff EA et al. . Attenuation of maternal psychophysiological stress responses and the maternal cortisol awakening response over the course of human pregnancy. Stress 2010;13:258–68. 10.3109/10253890903349501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.László KD, Ananth CV, Wikström AK et al. . Loss of a close family member the year before or during pregnancy and the risk of placental abruption: a cohort study from Denmark and Sweden. Psychol Med 2014;44:1855–66. 10.1017/S0033291713002353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Salinas C, Salinas C, Kurata J. The effects of the Northridge earthquake on the pattern of emergency department care. Am J Emerg Med 1998;16:254–6. 10.1016/S0735-6757(98)90095-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eskenazi B, Marks AR, Catalano R et al. . Low birthweight in New York City and upstate New York following the events of September 11th. Hum Reprod 2007;22:3013–20. 10.1093/humrep/dem301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Strand LB, Mukamal KJ, Halasz J et al. . Short-term public health impact of the July 22, 2011, terrorist attacks in Norway: a nationwide register-based study. Psychosom Med 2016;78:525–31. 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Olcese J, Beesley S. Clinical significance of melatonin receptors in the human myometrium. Fertil Steril 2014;102:329–35. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2015-010925supp_tables.pdf (187.7KB, pdf)