Abstract

Objective

To develop an active behavioural physiotherapy intervention (ABPI) for managing acute whiplash-associated disorder (WAD) II using a modified Delphi method to develop consensus for the basic features of the ABPI.

Design

Modified Delphi study. Our systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating conservative management for acute WADII found that a combined ABPI may be a useful intervention to prevent patients progressing to chronicity. No previous research has considered a combined behavioural approach and active physiotherapy in the management of acute WADII patients. The ABPI was therefore developed using a rigorous consensus method using international research and local clinical whiplash experts. Descriptive statistics were used to assess consensus in each round.

Setting

Online international survey.

Participants

A purposive sample of 97 potential participants (aiming to recruit n=30) consisting of international research whiplash experts, UK private physiotherapists and UK postgraduate musculoskeletal physiotherapy students were invited to participate via electronic mail with an attached participant information sheet and consent form.

Results

36 individuals signed and returned the consent form. In round 1, 32/36 participants (response rate=89%, mean age±SD=36.03±13.22 years) across 8 countries (Australia, Finland, Greece, India, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and UK) contributed to round 1 questionnaire. Response rates were 78% and 75% for rounds 2 and 3, respectively. Following round 3, 12 underlying principles (eg, return to normal function as soon as possible, pain management, encouragement of self-management, reduce fear avoidance and anxiety) achieved consensus. The treatment components reaching consensus included behavioural (eg, education, reassurance, self-management) and physiotherapy components (eg, exercises for stability and mobility). No passive intervention achieved consensus.

Conclusions

Experts suggested and agreed the underlying principles and treatment components of the ABPI for the management of acute WADII. The ABPI was underpinned by social cognitive theory focusing on self-efficacy enhancement prior to conducting a phase II trial.

Keywords: whiplash associated disorder, active behavioural physiotherapy intervention, modified Delphi, acute whiplash, whiplash, Self efficacy

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the provision of the principles and treatment components of an active behavioural physiotherapy intervention (ABPI) for acute whiplash-associated disorder II (WADII) management.

The principles and treatment components were developed using a rigorous method of fixed choice and open questions through an online survey to increase validity and reliability.

The intervention was developed using critical judgements of international research and local clinical whiplash experts.

A low recruitment rate with only ∼37% agreeing to participate from the sample of invited experts (36 respondents with invitation/97 potential participants) is a key limitation.

Lack of interaction and discussion among panellists due to the nature of the Delphi study is a limitation. However, the three rounds provided an opportunity for panellists to make further clarifications and in essence, see the findings based on the respondents from the total sample of participants.

Background

Whiplash-associated disorder (WAD) describes the variety of symptoms experienced after a whiplash injury, caused by rapid acceleration–deceleration mechanism of the head and neck, most commonly following road traffic accidents.1 Up to 60% of WAD patients progress to chronicity and experience moderate-to-severe pain and disability.1 2 Management of acute and chronic WAD is reported of limited success.3–5 An effective intervention is required, especially for whiplash-associated disorder II (WADII) classified patients (neck complaint and musculoskeletal sign(s))6 which reflects ∼93% of patients.7 It is a considerable challenge to develop an effective intervention for WADII management in the acute stage in order to prevent chronicity.

WAD is a substantial cause of economic burden at the individual, national and international level. WAD is associated with an increase in healthcare costs, reduced work productivity, lost earning capacity, socioeconomic costs and time contributed by caregivers.8 9 For example, within the first 2 years after a whiplash injury, employment propensity declined by 20–25%.8 The estimated annual economic cost related to WAD is US$3.9 billion in the USA10 and €10 billion in Europe.11 In the UK, it is estimated that the cost of claims for personal injury have risen from £7 billion to £14 billion over the last decade.12

Findings of our systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating conservative management of acute WADII13 demonstrated that active physiotherapy (activities from health professional suggestion to improve symptoms or reduce suffering from illness) was more effective for pain reduction than passive intervention (any intervention which use other people, equipment or other things to reduce symptoms or illness) at 6 months (95% CI −17.19 to −3.23, p=0.004) and 1–3 years (−26.39 to −10.08, p<0.001). Furthermore, behavioural intervention (strategies to promote useful behaviour to improve symptoms and reduce illness) was more effective for pain reduction at 6 months (−15.37 to −1.55, p=0.016) and improvement in cervical movement in the frontal (0.93 to 4.38, p=0.003) and transverse planes (0.43 to 5.46, p=0.027) at 3–6 months compared with standard/control intervention. The combination of an active physiotherapy and a behavioural intervention, herein termed the active behavioural physiotherapy intervention (ABPI), may therefore be an optimised and effective intervention for managing acute WADII and preventing chronicity.13 Unfortunately, the existing evidence was inadequate to enable delivery of an ABPI as no previous research has considered a combined behavioural approach and active physiotherapy in the management of acute WADII patients (four trials in our systematic review evaluated a behavioural but not combined intervention). The ABPI was therefore developed using a rigorous consensus method (namely, a modified Delphi study).

Methodology

Objectives

To develop an ABPI for managing acute WADII.

Design

Delphi method is a standard, common and simple method of developing interventions in healthcare.14 It has been defined as a “method for the systematic collection and aggregation of informed judgement from a group of experts on specific questions or issues” (ref. 15, p. 131). It is a low-cost, flexible and simple procedure to gain information independently and privately from a large number of people.14 There are further several advantages of the Delphi method such as anonymity, no sociopsychological pressure on the panellists and higher response rate.16 In order to create an intervention for WADII management, a modified Delphi study was therefore performed according to a prespecified protocol. Prior to conducting a phase II trial, existing evidence and the views of research and clinical whiplash experts were considered to define and provide the underlying principles and the treatment components for the management of patients with acute WADII.

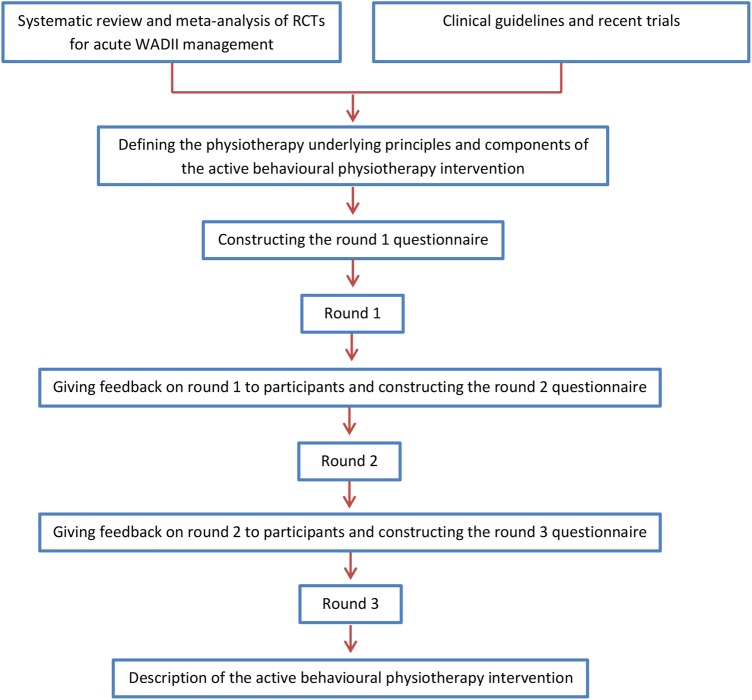

It was anticipated that this study would consist of three rounds.17–19 The LimeSurvey was used to collect data to enable the convenience of researchers and participants. A five-point Likert scale evaluated level of agreement throughout. Any underlying principles and treatment components which did not achieve the consensus criteria were removed. The process of intervention development is summarised in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Diagram for the method of intervention development. RCTs, randomised controlled trials; WADII, whiplash-associated disorder II.

Purposive sample

In order to secure a diverse group of whiplash experts (ie, those working in this area from a research, private physiotherapy or postgraduate clinical (predominantly UK National Health Service (NHS)) perspective), 97 potential participants were targeted for recruitment from 3 groups:

International research whiplash experts who had published at least two articles in a peer-reviewed journal regarding WAD within the last 10 years.

UK private physiotherapists from the West Midlands region in the UK, who had experience in treating WAD for at least 2 years. In the UK context, insurance companies frequently refer WADII patients to private physiotherapy clinics. Therefore, it was important to include physiotherapists working in the private sector.

Postgraduate musculoskeletal physiotherapy students studying at the University of Birmingham in the UK, who had experience in treating WAD for at least 2 years. Additionally, they must have completed the cervical management component of their programme. Most of the recruited students worked for the NHS.

All groups of participants can be considered to be experts informing the management of WAD from their different experiences. The eligible experts were invited to participate via electronic mail (email) that included a participant information sheet and consent form. They were requested to sign and send back the consent form via post or scanned email, depending on their preference, within 4 weeks. It was intended to recruit 10 participants in each group to enable equal representation of the three groups and a feasible number of participants. Past work has suggested that ∼30 participants are appropriate in a Delphi study to enable consensus.20–22

The ABPI consisted of two main sections.

Underlying principles of the ABPI

The potential underlying principles were derived from the systematic review, clinical guidelines and recent trials. The proposed underlying principles of the ABPI included return to normal function as soon as possible, return to normal movement as soon as possible, pain management, reduce post-traumatic stress, reduce fear avoidance and anxiety, increase confidence for exercises of the neck and shoulders, prevent future recurrent symptoms, encouragement of self-management, return to work and social activities as soon as possible, return to quality of life before preinjury and facilitate personal motivation for healthy lifestyle.

Treatment components of the ABPI

The potential treatment components were derived from the systematic review, clinical guidelines and examination of recent trials. Components were then grouped according to their focus/emphasis.

Behavioural components

The proposed behavioural components of the ABPI comprised cognitive–behavioural therapy, whiplash education, act-as-usual advice, reassurance, postural control and education, introduction of relaxation techniques and promotion of self-management.

Physiotherapy components

The proposed physiotherapy components of the ABPI comprised active mobilisation exercises, stabilisation exercises including deep neck flexor muscles, mobilisation with movement techniques (Mulligan), stretching exercises, mobility exercises, progressive exercises for strengthening, postural stabilisation, sensorimotor exercises (kinaesthetic sense, balance and eye movement) and breathing exercises. Passive interventions such as manual therapy and physical agents (eg, electrotherapy and thermotherapy) were also included in this component. A passive intervention may be employed for pain relief and improvement of cervical mobility based on physiotherapists' clinical reasoning.

Other treatments

The proposed ‘other treatment component’ comprised multimodal therapy and physical activity.

The modified Delphi method

After receiving responses from people who signed and returned the consent form, an email was sent to the participants containing a link to the email hosted on LimeSurvey. All the participants' information such as age, gender, country of origin, country of current habitation/work, highest qualification, current occupation, professional background and working period in WAD was collected. Participants were invited to provide their level of agreement for each principle and component and to identify any missing principle/component. Additionally, an open question was provided in each section in order to explore any missing principles/components which may have been overlooked. Any additional underlying principles and treatment components, which were suggested by at least one participant, were added into the underlying principles and the treatment components of the ABPI in order to evaluate participants' agreement with the suggestion in the next round. Furthermore, an open question was provided in the last section of the questionnaire to invite any further general comments or suggestions from the participants. In each round, a reminder was sent to participants on the second and fourth week after the LimeSurvey link was sent.

Round 1

The purposes of round 1 were as follows:

To evaluate the level of agreement of the participants with the underlying principles identified from guidelines and recent trials involving the ABPI.

To explore if any underlying principles of the ABPI for acute WADII management were missing.

To evaluate the level of agreement of the participants with the proposed behavioural and physiotherapy components of the ABPI.

To explore if any behavioural or physiotherapy components of the ABPI were missing.

Feedback on round 1 was provided to the participants in the form of summary tables (table 1: participants' backgrounds, table 2: underlying principles and table 3: treatment components).

Table 1.

Participants' backgrounds

| Characteristics | No. of participants | Percentage of participants (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Highest qualification | ||

| Doctor of Philosophy | 10 | 31.25 |

| Master degree | 4 | 12.50 |

| Bachelor degree | 18 | 56.25 |

| Current occupation | ||

| Professor | 3 | 9.38 |

| Associated professor | 2 | 6.25 |

| Senior lecturer | 1 | 3.13 |

| Assistant professor | 0 | 0 |

| Lecturer | 2 | 6.25 |

| Researcher in university | 2 | 6.25 |

| Clinical practitioner in hospital | 1 | 3.13 |

| Clinical practitioner in private sector | 10 | 31.25 |

| Postgraduate musculoskeletal physiotherapy students | 11 | 34.38 |

| Professional background | ||

| Physiotherapy | 31 | 96.88 |

| Other: sociology and insurance medicine | 1 | 3.13 |

| Whiplash experiences (years) | ||

| <2 | 6 | 18.75 |

| 2–5 | 11 | 34.38 |

| 6–10 | 5 | 15.63 |

| 11–15 | 3 | 9.38 |

| 16–20 | 3 | 9.38 |

| >20 | 4 | 12.50 |

Table 2.

Results of rounds 1, 2 and 3 for underlying principles of the ABPI

| Underlying principles | Round 1 |

Round 2 |

Round 3 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | IQR (Q1, Q3) | % (no) of agreement | Median | IQR (Q1, Q3) | % (no) of agreement | Median | IQR (Q1, Q3) | % (no) of agreement | Rank | |

| Return to normal function as soon as possible | 5 | 0.75 (4.25, 5.00) | 100.00 | 5 | 0.00 (5.00, 5.00) | 100.00 | 5 | 0 (5, 5) | 100.00 | 1 |

| Return to normal movement as soon as possible | 5 | 1.00 (4.00, 5.00) | 96.88 | 5 | 1.00 (4.00, 5.00) | 100.00 | 5 | 1 (4, 5) | 100.00 | 5 |

| Pain management | 5 | 1.00 (4.00, 5.00) | 96.88 | 5 | 1.00 (4.00, 5.00) | 96.43 | 5 | 1 (4, 5) | 92.59 | 2 |

| Reduce post-traumatic stress | 4 | 1.00 (4.00, 5.00) | 81.25 | 4 | 1.00 (4.00, 5.00) | 85.71 | 4 | 1 (4, 5) | 77.78 | 8 |

| Reduce fear avoidance and anxiety | 5 | 1.00 (4.00, 5.00) | 93.75 | 5 | 1.00 (4.00, 5.00) | 96.43 | 5 | 1 (4, 5) | 96.30 | 4 |

| Increase confidence for exercises of the neck and shoulders | 5 | 1.00 (4.00, 5.00) | 93.75 | 5 | 1.00 (4.00, 5.00) | 96.43 | 5 | 1 (4, 5) | 96.30 | 7 |

| Prevent future recurrent symptoms | 4 | 2.00 (3.00, 5.00) | 71.88 | 4 | 1.50 (3.25, 4.75) | 75.00 | 4 | 2 (3,5)* | 74.07 | 11 |

| Encouragement of self-management | 5 | 1.00 (4.00, 5.00) | 96.88 | 5 | 0.00 (5.00, 5.00) | 96.43 | 5 | 0 (5, 5) | 100.00 | 3 |

| Return to work and social activities as soon as possible | 5 | 0.75 (4.25, 5.00) | 100.00 | 4 | 1.00 (4.00, 5.00) | 100.00 | 5 | 1 (4, 5) | 100.00 | 6 |

| Return to quality of life before preinjury | 4.5 | 1.00 (4.00, 5.00) | 100.00 | 5 | 1.00 (4.00, 5.00) | 100.00 | 4 | 1 (4, 5) | 85.19 | 10 |

| Facilitate personal motivation for healthy lifestyle | 4 | 1.00 (3.00, 4.00) | 71.88 | 4 | 1.00 (3.00, 4.00) | 75.00 | 4 | 0 (4, 4) | 77.78 | 12 |

| Other please detail | Identify and managing sleep deprivations (provided by n=1 participant) | 4 | 0.00 (4.00, 4.00) | 85.71 | 4 | 2 (3, 5)* | 74.07 | 9 | ||

5=very important, 4=important, 3=no opinion, 2=not important, 1=not at all important.

*Not meet consensus criteria.

ABPI, active behavioural physiotherapy intervention.

Table 3.

Results of rounds 1 and 2 for treatment components of the ABPI

| Treatment components | Round 1 |

Round 2 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | IQR (Q1, Q3) | % (no) of agreement | Median | IQR (Q1, Q3) | % (no) of agreement | |

| 1. Behavioural treatment components | ||||||

| Cognitive–behavioural therapy | 4 | 1.00 (3.00, 4.00) | 62.50 | 4 | 1.00 (4.00, 5.00) | 85.71 |

| Whiplash education | 5 | 1.00 (4.00, 5.00) | 93.75 | 5 | 1.00 (4.00, 5.00) | 96.43 |

| Advice to act as usual | 5 | 1.00 (4.00, 5.00) | 90.62 | 5 | 1.00 (4.00, 5.00) | 89.29 |

| Reassurance | 5 | 1.00 (4.00, 5.00) | 96.88 | 5 | 1.00 (4.00, 5.00) | 100.00 |

| Postural control and education | 4 | 0.75 (4.00, 4.75) | 87.50 | 4.5 | 1.00 (4.00, 5.00) | 85.71 |

| Relaxation techniques | 4 | 1.00 (3.00, 4.00) | 65.62 | 4 | 0.75 (3.25, 4.00) | 75.00 |

| Self-management | 5 | 0.75 (4.25, 5.00) | 96.88 | 5 | 0.00 (5.00, 5.00) | 100.00 |

| Other please detail | No other treatment components were provided by participants | Mental imagery (a cognitive technique) (provided by n=1 participant) | ||||

| 2. Physiotherapy treatment components | ||||||

| Exercise and mobilisation therapy | ||||||

| Mobilisation with movement techniques (Mulligan) | 3 | 2.00 (2.00, 4.00) | 40.62* | |||

| Active mobilisation exercises including cervical protraction–retraction | 4 | 1.75 (3.25, 5.00) | 75.00 | 4 | 1.00 (4.00, 5.00) | 85.71 |

| Stabilisation exercises including deep neck flexor muscles | 4 | 1.00 (4.00, 5.00) | 87.50 | 4 | 1.00 (4.00, 5.00) | 82.14 |

| Stretching exercises | 4 | 2.00 (2.00, 4.00) | 62.50 | 4 | 1.00 (3.00, 4.00) | 67.86 |

| Mobility exercises | 4 | 1.00 (4.00, 5.00) | 100.00 | 4 | 1.00 (4.00, 5.00) | 100.00 |

| Progressive exercises for strengthening | 4 | 1.75 (3.25, 5.00) | 75.00 | 4 | 0.00 (4.00, 4.00) | 85.71 |

| Postural stabilisation | 4 | 0.75 (4.00, 4.75) | 81.25 | 4 | 1.75 (3.25, 5.00) | 75.00 |

| Sensorimotor exercises (kinaesthetic sense, balance and eye movement) | 4 | 2.00 (3.00, 5.00) | 62.50 | 4 | 1.00 (3.00, 4.00) | 71.43 |

| Breathing exercises | 3.5 | 1.00 (3.00, 4.00) | 50.00 | 3† | 1.00 (3.00, 4.00) | 46.43† |

| Other please detail | Stabilisation exercises including deep neck extensor muscles (provided by n=2 participants) | 4 | 1.00 (4.00, 5.00) | 82.14 | ||

| Manual therapy | ||||||

| Joint mobilisation | 4 | 2.75 (2.25, 5.00) | 65.62 | 4 | 1.75 (3.00, 4.75) | 71.43 |

| Massage or soft tissue mobilisation/manipulation | 4 | 1.00 (3.00, 4.00) | 62.50 | 4 | 2.00 (3.00, 5.00) | 71.43 |

| Joint manipulation | 3 | 1.00 (2.00, 3.00)* | 21.88* | |||

| Other please detail |

|

4 | 1.00 (3.00, 4.00) | 67.86 | ||

|

3† | 2.00 (2.00, 4.00) | 28.57† | |||

| Physical agents | ||||||

| TENS | 2* | 2.00 (1.00, 3.00)* | 12.50* | |||

| PENS | 1* | 1.00 (1.00, 2.00)* | 0.00* | |||

| MENS | 1* | 1.00 (1.00, 2.00)* | 0.00* | |||

| Electrical stimulation | 1* | 1.75 (1.00, 2.75)* | 3.13* | |||

| Interferential current | 1* | 1.00 (1.00, 2.00)* | 0.00* | |||

| Diadynamic current | 1* | 1.00 (1.00, 2.00)* | 0.00* | |||

| High voltage galvanic current | 1* | 0.75 (1.00, 1.75)* | 0.00* | |||

| Electromagnetic therapy | 1* | 1.00 (1.00, 2.00)* | 0.00* | |||

| Laser therapy | 1* | 1.00 (1.00, 2.00)* | 0.00* | |||

| Ultrasound | 1* | 1.00 (1.00, 2.00)* | 6.25* | |||

| Shortwave diathermy | 1* | 0.75 (1.00, 1.75)* | 0.00* | |||

| Shock wave diathermy | 1* | 0.75 (1.00, 1.75)* | 0.00* | |||

| Infared right | 1* | 1.00 (1.00, 2.00)* | 0.00* | |||

| Microwave | 1* | 1.00 (1.00, 2.00)* | 0.00* | |||

| Cyrotherapy | 3.5 | 2.00 (2.00, 4.00) | 50.00 | 3† | 2.00 (2.00, 4.00) | 35.71† |

| Heat | 4 | 1.00 (3.00, 4.00) | 68.75 | 4 | 1.00 (3.00, 4.00) | 71.43 |

| Mechanical traction | 2* | 2.00 (1.00, 3.00)* | 12.50* | |||

| Other please detail | No other treatment components were provided by participants | |||||

| 3. Other | ||||||

| Multimodal therapy | 4 | 1.00 (3.00, 4.00) | 59.38 | 4 | 0.75 (3.25, 4.00) | 75.00 |

| Physical activity such as aerobic and fitness | 4 | 1.00 (4.00, 5.00) | 87.50 | 4 | 0.00 (4.00, 4.00) | 82.14 |

| Other please detail |

|

3† | 1.00 (2.00, 3.00)† | 14.29† | ||

|

2† | 1.00 (2.00, 3.00)† | 7.14† | |||

5=very important, 4=important, 3=no opinion, 2=not important, 1=not at all important.

*Not meet consensus criteria for round 1.

†Not meet consensus criteria for round 2.

ABPI, active behavioural physiotherapy intervention; MENS, microcurrent electrical nerve stimulation; PENS, percutaneous electrical nerve stimulation; TENS, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation.

Round 2

The purposes of round 2 were as follows:

To evaluate the level of agreement of the participants with the underlying principles identified from round 1 data analysis of the ABPI.

To explore if any underlying principles of the ABPI for acute WADII management were further missing.

To evaluate the level of agreement of the participants with the proposed behavioural and physiotherapy components identified from round 1 data analysis of the ABPI.

To explore if any important components of the ABPI were further missing.

Feedback on round 2 was provided to the participants in the form of summary tables (table 2: underlying principles and table 3: treatment components).

Round 3

The purposes of round 3 were as follows:

To evaluate the level of agreement of the participants with the underlying principles identified from round 2 data analysis of the ABPI.

To rank the importance of the underlying principles identified from round 2 data analysis of the ABPI.

To evaluate the level of agreement of the participants with the proposed behavioural and physiotherapy components identified from round 2 data analysis of the ABPI.

To evaluate the feasibility of the underlying principles and the proposed components identified from round 2 data analysis of the ABPI being delivered in clinical practice.

Feedback on round 3 was not provided to the participants. The objective of this round was to make further clarifications of the underlying principles and the components of the ABPI.23 Furthermore, the participants were asked to rank the underlying principles and suggest how to deliver the components of the ABPI in practice as a multicomponent intervention.

Data management

Individual feedback was anonymised to maintain the participants' privacy. The personal information of participants was kept safely from any third party. All data were securely stored in a password-protected computer during the study. Only members of the research team could access the information. After completing the study, all data will be kept securely for 10 years in the School of Sport, Exercise and Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Birmingham, UK, before being securely destroyed.

Data analysis

The five-point Likert scale is an ordinal scale.24 25 Descriptive statistics including median, IQR, quartile and percentage of agreement were used to assess consensus in each round. Consensus was defined as follows; progressing in each round to ensure strong resulting consensus at the final round.

Round 1: criteria of consensus

Median ≥3

Third quartile (Q3) ≥4

Percentage of agreement ≥50%

Round 2: criteria of consensus

Round 3: criteria of consensus

All quantitative data were analysed using IBM SPSS V.22. Qualitative data were extracted deductively (to identify themes) and inductively (to identify additional themes).28 29 The importance of the underlying principles was ranked using scoring procedures.

Results

Participants

Thirty-six invited potential participants (11 researchers, 13 UK private physiotherapists and 12 UK postgraduate musculoskeletal physiotherapy students) signed and returned the consent form (response rate=37%). For round 1, 32 participants across 8 countries (Australia, Finland, Greece, India, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and UK) returned the questionnaire (16 males/16 females, response rate=89%, mean age±SD=36.03±13.22 years). There were no missing data in round 1. The details of participants' backgrounds are presented in table 1. The qualifications and occupations of the participants were diverse. All but one participant had a background in physiotherapy. Most participants had experience of treating whiplash patients >2 years.

Underlying principles

The results of rounds 1, 2 and 3 for underlying principles are summarised in table 2.

In round 1, all underlying principles of the ABPI reached the consensus criteria. Furthermore, ‘identify and managing sleep deprivations’ was a new principle suggested.

In round 2, there were 28 participants (78% of the original respondents) with no missing data. All underlying principles in this round achieved the consensus criteria with no additional suggestions.

In round 3, there were 27 participants (75% of the original respondents) with no missing data. The agreement and the rank of the importance of the underlying principles are presented in table 2. ‘Prevent future recurrent symptoms’ and ‘identifying and managing sleep deprivations’ did not meet the consensus criteria with respect to the IQR. However, these underlying principles were included in the ABPI because their median and percentage of agreement were high.

Treatment components

The results of rounds 1 and 2 for the treatment components of the ABPI are presented in table 3. In round 1, the following treatment components did not achieve the consensus criteria and were removed in the round 2 questionnaire: mobilisation with movement techniques (Mulligan), joint manipulation, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, percutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, microcurrent electrical nerve stimulation, electrical stimulation, interferential current, diadynamic current, high-voltage galvanic current, electromagnetic therapy, laser therapy, ultrasound, shortwave diathermy, shock wave diathermy, infrared light, microwave and mechanical traction. However, stabilisation exercises including deep neck extensor muscles, neural mobilisation, muscle energy techniques, acupuncture and dry needling were suggested and added to treatment components in the round 2 questionnaire.

In round 2, breathing exercises, muscle energy techniques, cryotherapy, acupuncture and dry needling were removed for round 3 according to the consensus. Mental imagery (a cognitive technique) was proposed and added to the questionnaire in round 3.

Table 4 provides the results from round 3 for the treatment components. Relaxation techniques, mental imagery, active mobilisation exercises, stretching exercises, sensorimotor exercises, joint mobilisation, massage, neural mobilisation, heat and multimodal therapy did not meet the consensus criteria. However, active mobilisation exercises including cervical protraction–retraction and multimodal therapy were included in the ABPI due to the observed high median score and percentage of agreement.

Table 4.

Results of round 3 for treatment components of the ABPI

| Median | IQR (Q1, Q3) | % (no) of agreement | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Behavioural treatment components | |||

| Self-management | 5 | 0 (5, 5) | 100.00 |

| Advice to act as usual | 5 | 1 (4, 5) | 100.00 |

| Whiplash education | 5 | 1 (4, 5) | 92.59 |

| Reassurance | 5 | 1 (4, 5) | 92.59 |

| Cognitive–behavioural therapy | 4 | 1 (4, 5) | 81.48 |

| Postural control and education | 4 | 1 (4, 5) | 81.48 |

| Relaxation techniques | 4 | 1 (3, 4) | 55.56* |

| Mental imagery (a cognitive technique) | 3* | 0 (3,3) | 22.22* |

Applying these behavioural treatment components in practice for individual patients:

| |||

| 2. Physiotherapy treatment components | |||

| Exercise and mobilisation therapy | |||

| Stabilisation exercises including deep neck extensor muscles | 5 | 1 (4, 5) | 77.78 |

| Mobility exercises | 4 | 1 (4, 5) | 88.89 |

| Progressive exercises for strengthening | 4 | 1 (4, 5) | 81.48 |

| Postural stabilisation | 4 | 1 (4, 5) | 81.48 |

| Stabilisation exercises including deep neck flexor muscles | 4 | 1 (4, 5) | 81.48 |

| Active mobilisation exercises including cervical protraction-retraction | 4 | 2 (3, 5)* | 74.07 |

| Stretching exercises | 4 | 1 (3, 4) | 59.26* |

| Sensorimotor exercises (kinaesthetic sense, balance and eye movement) | 4 | 1 (3, 4) | 62.96* |

| Manual therapy | |||

| Joint mobilisation | 4 | 2 (3, 5) * | 62.96* |

| Massage or soft tissue mobilisation/manipulation | 4 | 1 (3, 4) | 55.56* |

| Neural mobilisation | 3* | 1 (3, 4) | 48.15* |

| Physical agents | |||

| Heat | 3* | 2 (2, 4) * | 44.44* |

Applying these physiotherapy treatment components in practice for individual patients

| |||

| 3. Other | |||

| Multimodal therapy | 4 | 2 (3, 5)* | 74.07 |

| Physical activity such as aerobic and fitness | 4 | 1 (3, 4) | 70.37 |

Applying these other possible treatment components in practice for individual patients

| |||

*Not meet consensus criteria for round 3.

Italic typeface indicates interventions that did not meet the consensus criteria and were excluded in the ABPI.

ABPI, active behavioural physiotherapy intervention; GP, general practitioner.

Discussion

This modified Delphi study explored the opinions of international research whiplash experts, UK private physiotherapists and UK postgraduate musculoskeletal physiotherapy students for acute WADII management. The response rate in the final round was 75% from consented respondents, which is quite high compared with previous studies.19 30 This study provided open questions in each section and the last section (for general comments or suggestions) in order to allow panellists to comment and express their views, to enable greater ecological validity of the results.31

In managing acute WADII, it is interesting to consider the following underlying principles: return to normal function as soon as possible, pain management, encouragement of self-management, reduce fear avoidance and anxiety, return to normal movement as soon as possible, return to work and social activities as soon as possible and increase confidence for exercises of the neck and shoulders which were rated highly and ranked 1–7 of the important underlying principles. These underlying principles can assist individual physiotherapists in setting goals to manage their patients. However, other underlying principles could be considered based on patients' particular problems.

Our findings suggest a range of behavioural and physiotherapy treatment components of the ABPI in managing patients with acute WADII. The current acute WAD guidelines generally suggest reassurance and staying active, pharmacotherapy, active and passive (low level of evidence) physiotherapy.32–34 However, the consensus reached in this study highlights a specified range of psychological (eg, education, reassurance and self-management) and active physiotherapy (eg, exercises for stability and mobility) that are potentially effective intervention components in managing patients with acute WADII. From the literature, WADII patients commonly faced physical (eg, pain and disability) and psychological (eg, fear of movement, anxiety and depression) problems.35–38 The findings of this study regarding suggested treatment components addressed physical and psychological problems and suggest that the development of a multicomponent ABPI may assist physiotherapists in managing their WAD patients. However, minimal information from participants regarding how to deliver the components of the ABPI in practice was provided, and in particular no underpinning psychological theory to inform the structure and nature of the intervention was provided.

Self-efficacy, as defined by Bandura,39 is “the belief in one's capabilities to organise and execute the courses of action required to manage” and realise success in a particular situation. In essence, self-efficacy is task-specific self-confidence and this psychological construct plays a key role in Bandura's social cognitive theory.40 41 In the rehabilitation context, self-efficacy judgements correlate with quality of life and general health status and functioning as reflected in psychological (eg, anxiety, depression and fear of movement) and physical (eg, pain and physical function) aspects.42 43 According to Bandura, there are four important sources of self-efficacy, namely mastery experiences/performance accomplishments (successfully performing a task and realising mastery), social persuasion (receiving verbal encouragement from valued and respected others), vicarious learning or social modelling (watching someone similar to oneself exert effort and successfully perform a task) and psychological and physical responses (emotional states, physical responses such as pain, anxiety) can impact self-efficacy levels. Three of the processes (mastery experiences/performance accomplishments, social persuasion, psychological and physical responses) will be used at each stage of rehabilitation.

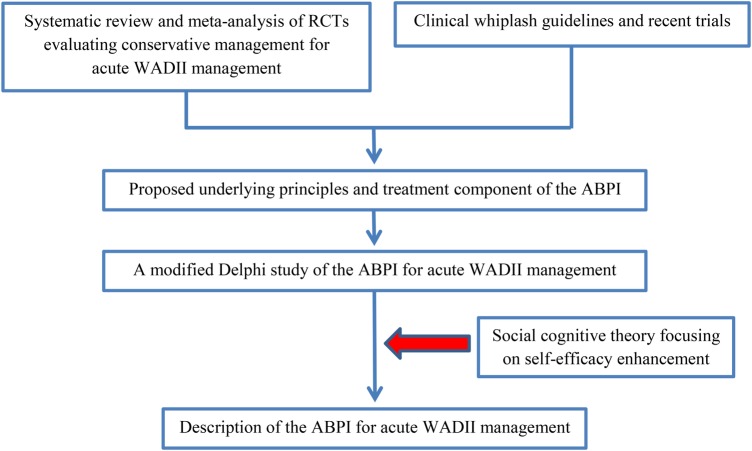

This process of underpinning the ABPI with a theory to inform structure and delivery further develops the ABPI as a complex intervention in line with the Medical Research Council Framework of Complex Interventions;44 using social cognitive theory39 as its theoretical foundation. The overarching aim of the ABPI will be to enhance patients' self-efficacy (focus of self-efficacy decided based on an individual patient's problems, eg, to reduce fear of movement) following their physiotherapy treatment. Figure 2 illustrates this enhanced process of the development of the ABPI.

Figure 2.

Diagram for the development of an ABPI. ABPI, active behavioural physiotherapy intervention; RCTs, randomised controlled trials; WADII, whiplash-associated disorder II.

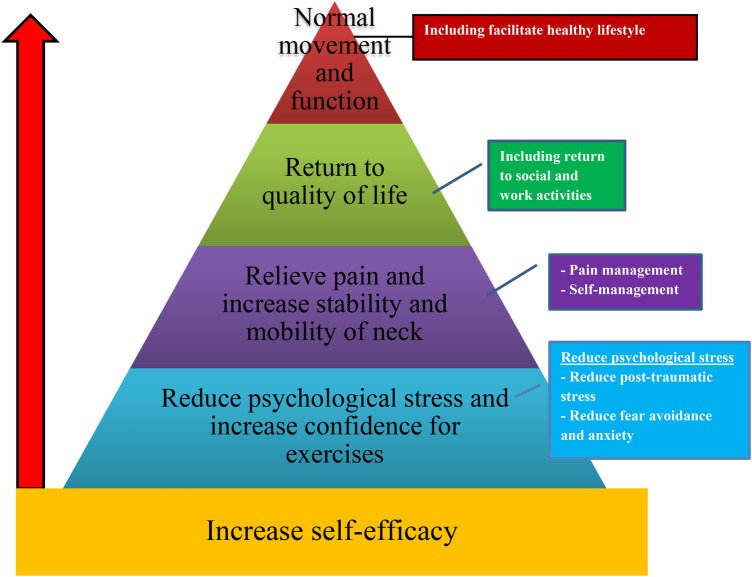

The concept of the ABPI (figure 3) is to guide physiotherapists in managing patients with acute WADII using the underlying principles of the ABPI resulting from this study coupled with an understanding of self-efficacy and its sources.39 All underlying principles were grouped and then designed in a potential sequence for the management in patients with acute WADII. More specifically, there were several main factors that should be identified and addressed as part of the intervention (eg, reduce psychological stress, increase confidence for doing the exercises, pain reduction, improvement in stability and mobility of neck, return to quality of life and return to social and work activities) to help WADII patients in reaching the final goal. It is like ‘climbing a mountain’, which is why the model was designed in a triangle shape. The final goal of the management is to have the patient return to normal movement and function as soon as possible which was ranked as the most important underlying principle by the experts. Full details of the ABPI are provided in ‘acute whiplash injury study (AWIS): a protocol for a cluster randomised pilot and feasibility trial of an ABPI in an insurance private setting’.45

Figure 3.

Concept of an active behavioural physiotherapy intervention.

Strengths

This study is the first to provide the principles and treatment components of an ABPI which were initially identified from our rigorous systematic review evaluating effectiveness of acute WADII management.13 The principles and treatment components were developed by a robust methodology using fixed choice and open questions presented in an online survey to increase reliability and validity of the study by critical judgements of international research and local clinical whiplash experts. Then, a theoretical perspective was applied to consolidate the emerging principles and components and suggest processes of behavioural change, developing the ABPI further as a complex intervention in line with the Medical Research Council Framework of Complex Interventions.44 In a subsequent exploratory trial, the ABPI will be evaluated in regard to its feasibility of implementation, acceptability of the developed intervention, retention and compliance.45 From the findings of this trial regarding intervention effects, it will be possible to estimate a sample size for an adequately powered RCT.

Limitations

The study had a low recruitment rate with 37% agreeing to participate from the sample of invited experts (36/97 potential participants). This was anticipated, and the aim to recruit n=30 participants was achieved. Although there were 40 eligible WAD researchers internationally, only 11 (27.5%) researchers consented to participate. Interestingly, the main reason for them declining to participate was that they work with chronic WAD patients (n=6). It was the same situation for recruiting postgraduate musculoskeletal physiotherapy students (12/44 respondents). Even though most of them worked in the NHS, a lot of them had never treated whiplash patients. From researchers and students who explained their reasons for not participating, there was therefore no obvious risk of bias owing to participation rate. In contrast and unsurprisingly, the recruitment rate in the private sector was high (13/13 respondents) as this is where most whiplash patients are treated in the UK. This narrow professional involvement could be considered a limitation but in the UK context, WADII patients are most commonly managed by physiotherapists.

It should also be noted that six of all participants had experience working with whiplash patients for <2 years.

To enhance convenience for the participants, this study involved the administration of an electronic questionnaire, leading to lack of interaction and discussion among panellists. However, the number of rounds provided within the Delphi method provided an opportunity for panellists to make further clarifications and in essence, see the findings based on the respondents from the total sample of participants. Using open question in increasing ecological validity may have less generalisability to the whole field of musculoskeletal practitioners.

Conclusions

Experts suggested and provided agreement regarding the underlying principles and treatment components of the ABPI for the management of acute WADII. Owing to lack of identification of any theory to underpin the ABPI and its delivery in physiotherapy practice, the ABPI was further developed using social cognitive theory and centred on self-efficacy enhancement as a result of the physiotherapy treatment. A pilot and feasibility trial is now required to evaluate procedures, feasibility and acceptability of the ABPI in managing acute WADII within physiotherapy clinics prior to the design of an adequately powered RCT.

Acknowledgments

The first author (TW) thank the Ministry of Science and Technology of Thailand under the Royal Thai Government and Naresuan University for the scholarship supporting his PhD studies and Physio 1st clinics network for allowing staff to participate in this study. The authors are also grateful to the University of Birmingham for providing the LimeSurvey and the sponsorship. Finally, appreciation is expressed to all participants who provided their invaluable time and useful opinions regarding acute WADII management to prevent acute WADII patients progressing to chronicity.

Footnotes

Contributors: TW was responsible for the development of the questionnaires, data management and analysis and drafting of the manuscript of the modified Delphi study. AR, JD and MSH reviewed and commented on the questionnaires, results and current and previous versions of this manuscript. Nicola Heneghan and Jonathan Price helped in recruiting postgraduate musculoskeletal physiotherapy students and UK private physiotherapists, respectively.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: University of Birmingham's Ethical Committee (ERN_14-1339).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Sterling M. Physiotherapy management of whiplash-associated disorders (WAD). J Physiother 2014;60:5–12. 10.1016/j.jphys.2013.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jull GA, Sterling M, Curatolo M et al. . Toward lessening the rate of transition of acute whiplash to a chronic disorder. Spine 2011;36(25 Suppl):S173–4. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31823883e6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jull G, Kenardy J, Hendrikz J et al. . Management of acute whiplash: a randomized controlled trial of multidisciplinary stratified treatments. Pain 2013;154:1798–806. 10.1016/j.pain.2013.05.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lamb SE, Gates S, Williams MA et al. . Emergency department treatments and physiotherapy for acute whiplash: a pragmatic, two-step, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2013;381:546–56. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61304-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Michaleff ZA, Maher CG, Lin CW et al. . Comprehensive physiotherapy exercise programme or advice for chronic whiplash (PROMISE): a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2014;384:133–41. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60457-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spitzer WO, Skovron ML, Salmi LR et al. . Scientific monograph of the Quebec Task Force on Whiplash-Associated Disorders: redefining “whiplash” and its management. Spine 1995;20(8 Suppl):1S–73S. 10.1097/00007632-199504151-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sterling M. A proposed new classification system for whiplash associated disorders—implications for assessment and management. Man Ther 2004;9:60–70. 10.1016/j.math.2004.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leth-Petersen S, Rotger GP. Long-term labour-market performance of whiplash claimants. J Health Econ 2009;28:996–1011. 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2009.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jennum P, Kjellberg J, Ibsen R et al. . Health, social, and economic consequences of neck injuries: a controlled national study evaluating societal effects on patients and their partners. Spine 2013;38:449–57. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182819203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eck JC, Hodges SD, Humphreys SC. Whiplash: a review of a commonly misunderstood injury. Am J Med 2001;110:651–6. 10.1016/S0002-9343(01)00680-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galasko CSB, Murray P, Stephenson W. Incidence of whiplash-associated disorder. B C Med J 2002;44:237–40. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mooney H. Insurance companies are reeling from the number of claims being made by people who say they have whiplash injuries 2012. February. http://www.csp.org.uk/frontline/article/what%E2%80%99s-driving-rise-whiplash-injuries (accessed Oct 2013).

- 13.Wiangkham T, Duda J, Haque S et al. . The effectiveness of conservative management for acute whiplash associated disorder (WAD) II: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. PLoS One 2015;10:e0133415 10.1371/journal.pone.0133415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murphy MK, Black NA, Lamping DL et al. . Consensus development methods, and their use in clinical guideline development. Health Technol Assess 1998;2:i––iv., 1–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reid N. Health care research by degrees. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 16.von der Gracht HA. Consensus measurement in Delphi studies: review and implications for future quality assurance. Technol Forecast Soc Change 2012;79:1525–36. 10.1016/j.techfore.2012.04.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rushton A, Moore A. International identification of research priorities for postgraduate theses in musculoskeletal physiotherapy using a modified Delphi technique. Man Ther 2010;15:142–8. 10.1016/j.math.2009.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rankin G, Rushton A, Olver P et al. . Chartered Society of Physiotherapy's identification of national research priorities for physiotherapy using a modified Delphi technique. Physiotherapy 2012;98:260–72. 10.1016/j.physio.2012.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rushton AB, Fawkes CA, Carnes D et al. . A modified Delphi consensus study to identify UK osteopathic profession research priorities. Man Ther 2014;19:445–52. 10.1016/j.math.2014.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dionne CE, Dunn KM, Croft PR et al. . A consensus approach toward the standardization of back pain definitions for use in prevalence studies. Spine 2008;33:95–103. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31815e7f94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fisher CG, DiPaola CP, Ryken TC et al. . A novel classification system for spinal instability in neoplastic disease: an evidence-based approach and expert consensus from the Spine Oncology Study Group. Spine 2010;35:E1221–9. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181e16ae2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schutt AC, Bullington WM, Judson MA. Pharmacotherapy for pulmonary sarcoidosis: a Delphi consensus study. Respir Med 2010;104:717–23. 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsu C-C, Sandford BA. The Delphi technique: making sense of consensus. Pract Assess Res Eval 2007;12:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Allen IE, Seaman CA. Likert scales and data analyses. Qual Prog 2007;40:64–5. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Norman G. Likert scales, levels of measurement and the “laws” of statistics. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2010;15:625–32. 10.1007/s10459-010-9222-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown AK, O'Connor PJ, Roberts TE et al. . Recommendations for musculoskeletal ultrasonography by rheumatologists: setting global standards for best practice by expert consensus. Arthritis Rheum 2005;53:83–92. 10.1002/art.20926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rayens MK, Hahn EJ. Building consensus using the policy Delphi method. Policy Polit Nurs Pract 2000;1:308–15. 10.1177/152715440000100409 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ayala GX, Elder JP. Qualitative methods to ensure acceptability of behavioral and social interventions to the target population. J Public Health Dent 2011;71(Suppl 1):S69–79. 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2011.00241.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bos C, Van der Lans IA, Van Rijnsoever FJ et al. . Understanding consumer acceptance of intervention strategies for healthy food choices: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2013;13:1073 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carnes D, Mullinger B, Underwood M. Defining adverse events in manual therapies: a modified Delphi consensus study. Man Ther 2010;15:2–6. 10.1016/j.math.2009.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McDonnell J, Meijler A, Kahan JP et al. . Panellist consistency in the assessment of medical appropriateness. Health Policy 1996;37:139–52. 10.1016/S0168-8510(96)90021-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jagnoor J, Cameron I, Harvey L et al. . Motor Accidents Authority: guidelines for the management of acute whiplash-associated disorders—for health professionals. 3rd edn Sydney: NSW Government, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 33.TRACsa. Clinical guidelines for best practice management of acute and chronic whiplash associated disorders: clinical resource guide. Adelaide: TRACsa: Trauma and Injury Rocovery, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moore A, Jackson A, Jordan J et al. . Clinical guidelines for the physiotherapy management of whiplash associated disorder. London: Chartered Society of Physiotherapy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sterling M, Jull G, Vicenzino B et al. . Physical and psychological factors predict outcome following whiplash injury. Pain 2005;114:141–8. 10.1016/j.pain.2004.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sterling M, Chadwick BJ. Psychologic processes in daily life with chronic whiplash: relations of posttraumatic stress symptoms and fear-of-pain to hourly pain and uptime. Clin J Pain 2010;26:573–82. 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181e5c25e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buitenhuis J, de Jong PJ. Fear avoidance and illness beliefs in post-traumatic neck pain. Spine 2011;36(25 Suppl):S238–43. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182388400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nijs J, Inghelbrecht E, Daenen L et al. . Long-term functioning following whiplash injury: the role of social support and personality traits. Clin Rheumatol 2011;30:927–35. 10.1007/s10067-011-1712-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev 1977;84:191 10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee W, Lee M-J, Bong M. Testing interest and self-efficacy as predictors of academic self-regulation and achievement. Contemp Educ Psychol 2014;39:86–99. 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2014.02.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schwarzer R, Antoniuk A, Gholami M. A brief intervention changing oral self-care, self-efficacy, and self-monitoring. Br J Health Psychol 2015;20:56–67. 10.1111/bjhp.12091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Börsbo B, Gerdle B, Peolsson M. Impact of the interaction between self-efficacy, symptoms and catastrophising on disability, quality of life and health in with chronic pain patients. Disabil Rehabil 2010;32:1387–96. 10.3109/09638280903419269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barlow J. Self-efficacy in the context of rehabilitation. International Encyclopedia of Rehabilitation, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S et al. . Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008;337:a1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wiangkham T, Duda J, Haque MS et al. . Acute whiplash injury study (AWIS): a protocol for a cluster randomised pilot and feasibility trial of an active behavioural physiotherapy intervention in an insurance private setting. BMJ Open 2016;6:e011336 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]