Abstract

Background

Secondary prevention is cost-effective for cardiovascular disease (CVD), but uptake is suboptimal. Understanding barriers and facilitators to adherence to secondary prevention for CVD at multiple health system levels may inform policy.

Objectives

To conduct a systematic review of barriers and facilitators to adherence/persistence to secondary CVD prevention medications at health system level.

Methods

Included studies reported effects of health system level factors on adherence/persistence to secondary prevention medications for CVD (coronary artery or cerebrovascular disease). Studies considered at least one of β blockers, statins, angiotensin–renin system blockers and aspirin. Relevant databases were searched from 1 January 1966 until 1 October 2015. Full texts were screened for inclusion by 2 independent reviewers.

Results

Of 2246 screened articles, 25 studies were included (12 trials, 11 cohort studies, 1 cross-sectional study and 1 case–control study) with 132 140 individuals overall (smallest n=30, largest n=63 301). 3 studies included upper middle-income countries, 1 included a low middle-income country and 21 (84%) included high-income countries (9 in the USA). Studies concerned established CVD (n=4), cerebrovascular disease (n=7) and coronary heart disease (n=14). Three studies considered persistence and adherence. Quantity and quality of evidence was limited for adherence, persistence and across drug classes. Studies were concerned with governance and delivery (n=19, including 4 trials of fixed-dose combination therapy, FDC), intellectual resources (n=1), human resources (n=1) and health system financing (n=4). Full prescription coverage, reduced copayments, FDC and counselling were facilitators associated with higher adherence.

Conclusions

High-quality evidence on health system barriers and facilitators to adherence to secondary prevention medications for CVD is lacking, especially for low-income settings. Full prescription coverage, reduced copayments, FDC and counselling may be effective in improving adherence and are priorities for further research.

Key questions.

What is already known about this subject?

Despite proven cost-effectiveness of medications for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease, adherence is suboptimal.

What does this study add?

The barriers and facilitators to medication adherence at health system level are poorly characterised, particularly in low-income settings. Full prescription coverage, reduced copayments, fixed-dose combination (FDC) therapy and counselling are effective on the basis of existing data, but further research is needed.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

At health system level, finance mechanisms, FDC therapy and counselling should be prioritised in research and implementation to promote medication adherence in individuals with cardiovascular disease.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading threat to global health, whether measured by mortality, morbidity or economic cost.1 The greatest burden of CVD is in low and middle-income countries, with crippling macroeconomic effects.1–4 Health policy focussing on CVD has become a priority to policymakers, scientists, health professionals and patients.5–7

Secondary prevention represents a crucial and cost-effective component of the response due to the high absolute risk of recurrent cardiovascular events in individuals with established CVD.8 Above and beyond effective lifestyle interventions (smoking cessation, physical activity and appropriate diet), there is high-quality evidence that drug therapy with aspirin, statins, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) or angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs) and β blockers is effective in reducing morbidity and mortality from CVD in individuals with pre-existing CVD.9 Although these medications are off-patent and should be available at low cost, uptake is suboptimal.10 The problem is heightened in the poorest settings, but there are still significant gaps even in affluent countries.11 12

Obstacles to evidence-based secondary CVD prevention are context-specific, and differences in healthcare systems between countries of varying incomes are important contributors to differences in health outcomes.10 For example, the Population Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study demonstrated higher CVD mortality in low-income countries than in high-income countries, despite a lower risk factor burden in the former.13 However, there has not been comprehensive evaluation of barriers and facilitators to medication adherence for CVD secondary prevention at multiple health system levels and in diverse financial and sociocultural settings, which would inform health policy. The objective of this systematic review was therefore to identify health system features, programmes or strategies which act as barriers or facilitators to adherence to evidence-supported medications for CVD secondary prevention.

Methods

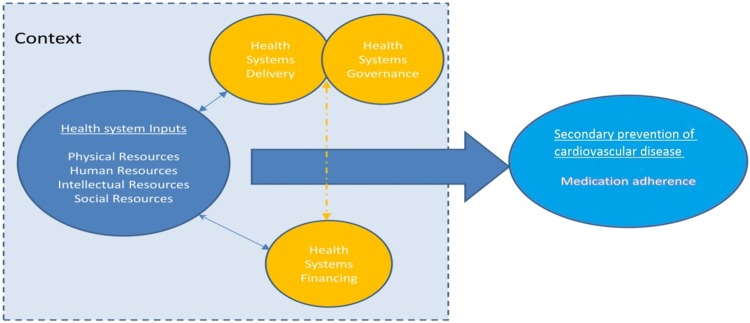

A protocol for this study has been published (PROSPERO 2015: CRD42015019079). We used an established framework14 to illustrate the health system and its elements (figure 1). This conceptual framework consists of health system ‘inputs’(which include physical, human, intellectual and social resources) plus components and characteristics of delivery, governance and financing.14

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of health systems conceptual framework (from Maimaris et al14 with permission from PLoS).

Inclusion criteria

We included quantitative and qualitative studies reporting associations of local, national, regional or international health system level factors, interventions, policies or programmes with adherence to medications for the secondary prevention of CVD (coronary artery or cerebrovascular disease) until 1 October 2015 with no language restrictions. Included studies had analyses of barriers and facilitators to adherence or persistence to at least one of β blockers, statins, angiotensin–renin system blockers and aspirin. Any outcome measures of adherence (“the extent to which a patient acts in accordance with the prescribed interval and dose of a dosing regimen”) or persistence (“the duration of time from initiation to discontinuation of therapy”)15 were considered. We excluded studies reporting prescription and usage alone.

Search strategy

Our search included MEDLINE, EMbase, Cochrane Library, Psychinfo, Health Systems Evidence, Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC), Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature (LILACS), Africa-Wide Information and Google Scholar. We also searched conference proceedings and reference lists of relevant research articles. We also consulted experts in health policy regarding access to medicines. Our search terms and actual strategy are further detailed in the online supplementary appendix.

openhrt-2016-000438supp_appendix.pdf (486.1KB, pdf)

Study selection

Each title and/or abstract identified by the search strategy was independently reviewed for potential eligibility by two investigators (from AB, MM, KCQ, LN, MS, VP, JPW, JRFN). Full texts were obtained and further screened for inclusion by two reviewers. Disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer.

Data extraction

Prior to data extraction, a validation exercise was conducted to ensure consistency with respect to data extracted from five articles. Data were extracted from each study on study design, setting, methods and outcomes; health system domains investigated, health system barriers or facilitators. Data were extracted according to a ‘health system framework’:14 (1) health systems delivery; (2) health systems governance; (3) health systems financing; (4) health systems inputs: physical, human, intellectual and social resources and (5) outcomes for secondary prevention medications of CVD: adherence and persistence. Two reviewers (AB and JPW) checked consistency of inclusion criteria and data extraction across all included studies. At the data extraction stage, there was disagreement in 1/25 studies (4.0%), which was resolved by discussion between AB and JPW.

Assessment of the risk of bias

Included studies were independently assessed for risk of bias by two reviewers using a framework previously used for observational study designs in similar systematic reviews: selection bias, information bias (differential misclassification and non-differential misclassification) and confounding.14 Risk of bias was assessed as either low, unclear or high for each domain and overall. The Cochrane tool for reporting of bias was used for clinical trials (see online supplementary appendix 2). Disagreements in classification of bias and data extraction were resolved by a third reviewer (AB or JPW). Publication bias was assessed by funnel plot analysis. Conflicts of interest were not assessed.

Data synthesis and analysis

Studies were categorised according to health system domain and setting. ORs were recorded, if reported, as “OR, 95% confidence interval; p value”. Where possible, OR or RR was calculated from available data, if not reported. Reporting complied with standards in ‘Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses’ (PRISMA).16 Meta-analysis was not possible due to heterogeneity of included studies across multiple domains, including study populations, study designs, varying definitions of exposures and outcomes and analytical strategies.

Results

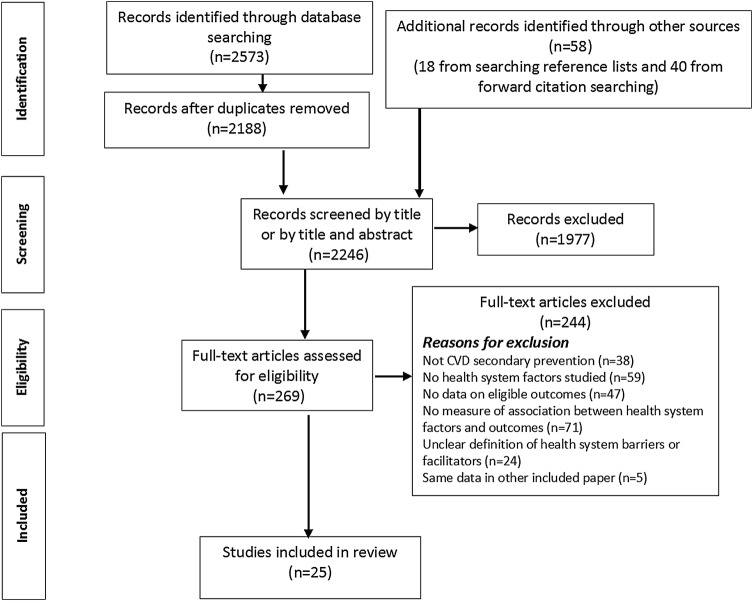

Figure 2 shows the PRISMA flow chart. A total 2246 articles were screened by title and abstract. Full texts of 269 of the 2246 articles were assessed for eligibility. Twenty-five quantitative and no qualitative studies met eligibility criteria for this review. Table 1 shows characteristics of included studies by domains of the conceptual framework described by Maimaris et al.14 Full details are in table 2. Online supplementary appendix tables 1a–c summarise included studies by adherence, persistence and drug class, respectively. Tables 3 and 4 show risk of bias assessment for included trials and observational studies, respectively.

Figure 2.

PRISMA flow chart. CVD, cardiovascular disease. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Table 1.

Health system arrangements investigated by included studies, classified by health system domain

| Health system framework domain | Health system factor being investigated | Number of studies | Number of studies and study designs | Setting of studies (countries) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Governance and delivery | Physician-led education | 1 | RCT (1) | UK (1)21 |

| Nurse-led education | 3 | RCT (2) | Denmark (1),22 UK (1)23 | |

| Cohort (1) | USA/Canada (1)39 | |||

| Pharmacy-led education | 2 | RCT (1) | USA (1)17 | |

| Non-randomised trial (1) | Germany (1)29 | |||

| Comprehensive education programme | 2 | RCT (1) | Turkey (1)24 | |

| Cohort (1) | France (1)36 | |||

| Hospital-level quality improvement | 4 | RCT (1) | USA (1)19 | |

| Cohort (2) | USA (1)30 Canada (1)31 | |||

| Case–control (1) | USA (1)41 | |||

| Routine place of care | 1 | Cohort (1) | Sweden (1)32 | |

| Generic versus branded drugs | 1 | Cohort (1) | USA (1)37 | |

| Complexity of treatment regimen | 1 | Cross-sectional (1) | Argentina/Brazil/Italy/Paraguay/Spain (1)25 | |

| FDC | 4 | RCT (4) | India/Europe (1),20 Australia/New Zealand (1),26 New Zealand (1),28 Argentina/Brazil/Italy/Paraguay/Spain (1)25 | |

| All governance and delivery studies | 19 | RCT (10), non-randomised trial (1), cohort (6), cross-sectional (1), case–control (1) | USA (5), Canada (1), USA/Canada (1), UK(2), Germany (1), Sweden (1), Turkey (1), France (1), Denmark (1), India/Europe (1), Australia/New Zealand (1), New Zealand (1), Argentina/Brazil/Italy/Paraguay/Spain (2) | |

| Human resources | Undergraduate training of physicians | 1 | Cohort (1) | Canada (1)18 |

| All human resources studies | 1 | Cohort (1) | Canada (1) | |

| Intellectual resources | Education of physicians | 1 | Cohort (1) | Israel (1)33 |

| All intellectual resources studies | 1 | Cohort (1) | Israel (1) | |

| Health system financing | Copayments for medical care | 2 | Cohort (2) | USA (1),35 Austria (1)34 |

| Insurance and prescription cost assistance | 2 | Cohort (1) | USA (1)38 | |

| RCT (1) | USA (1)27 | |||

| All financing studies | 4 | RCT (1), cohort (3) | USA (3), Austria (1) | |

| Physical resources | All physical resources studies | 0 | ||

| Social resources | All social resources studies | 0 |

Italics denote the total number of studies under a particular health system domain. RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Table 2.

Summary of findings of studies examining the associations of barriers/facilitators and adherence/persistence

| Barriers/facilitators | Study (author, year, setting) | Context | Study design | Sample size | Study details | Outcome | Relevant findings (95% CIs given where available and in italics when p<0.05) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient counselling | O'Carroll, 2013 (UK)21 | First stroke/TIA | RCT | 62 | Intervention=physician-led counselling sessions aimed at increasing adherence | Adherence to antihypertensive medication at 3 months Electronic pill count and self-report |

Intervention versus control: by electronic pill count, percentage of doses taken on schedule—96.8% vs 87.4%, mean difference 9.8%, 95% CI 0.2 to 16.2; p=0.048 Self-report highly correlated with electronic pill count |

| Hornnes, 2011 (Denmark)22 | Acute stroke/TIA | RCT | 349 | Intervention=four home visits by a nurse with individually tailored counselling on a healthy lifestyle | Adherence to antihypertensive therapy at 1 year Self-report |

Intervention versus control: 98% vs 99%, OR 0.88, 95% CI 0.54 to 1.44; p=0.50 | |

| Maron, 2010 (USA and Canada)39 | Stable CHD | Prospective cohort | 2287 | Nurse-led case management nested in the Clinical Outcomes Utilizing Revascularization and Aggressive Drug Evaluation (COURAGE) Trial. CVD drugs provided at no cost | Adherence and persistence to 4D at 5 years Self-report |

Persistence increased from baseline to 5 years as follows: antiplatelets 87% to 96%, (OR 3.58, 95% CI 2.48 to 5.18); β blockers 69% to 85% (OR 2.54, 2.06 to 3.15); ARBs 46% to 72% (OR 3.02, 2.53 to 3.60), statins 64% to 93% (OR 7.51, 5.67 to 9.94), 4D 28% to 53% (OR 2.90, 95% CI 2.44 to 3.43) (all p<0.001). Adherence was 97% at 6 months and 95% at 5 years |

|

| McManus, 2009 (UK)23 | Stroke in hospital | RCT | 102 | Intervention=3 months nurse-led health counselling with written and verbal information on lifestyle, and check of medication concordance | Adherence and persistence to 4D at 3 years Self-report |

Persistence: 95% vs 89%, OR 3.00, 0.57 to 15.7 (p=0.19) for antiplatelets 97% vs 95%, OR 1.02, 0.55 to 1.91 (p=0.95) for antihypertensives 88% vs 89%, OR 1.03, 0.25 to 4.14 (p=0.97) for statins Adherence to 4D: 78% vs 92%, OR 0.30, 0.07 to 1.24 (p=0.10) |

|

| Faulkner, 2000 (USA)17 | CABG | RCT | 30 | Intervention=weekly pharmacist-led telephone contact for 12 weeks | Adherence to lovastatin at 1 year and 2 years Prescription fill rate |

Intervention versus control: 67% vs 33%; p<0.05 at 1 year and 60% vs 27%; p<0.05 at 2 years (χ2 test reported) At 1 year, OR 4.00, 0.88 to 18.26; p=0.07, and at 2 years, OR 4.13, 0.88 to 19.27; p=0.07 |

|

| Hohmann, 2009 (Germany)29 | Ischaemic stroke/TIA in hospital | Non-randomised, controlled intervention trial | 255 | Intervention=hospital pharmacist counselling before discharge and plan for outpatient care plus counselling by community pharmacists | Persistence to aspirin and clopidogrel at 1 year Self-reported and GP-reported |

Intervention: 38.7% vs 32.7%, OR 1.30, 0.73 to 2.31; p=0.37 for aspirin and 26.7% and 30.1%, OR 0.85, 0.46 to 1.57; p=0.60 for clopidogrel | |

| Lafitte, 2009 (France)36 | ACS in hospital | Prospective cohort | 660 | 3 months after discharge for ACS, consecutive patients were invited to join a comprehensive risk factor management programme | Persistence to 4D at 20 months (mean follow-up) Self-report |

At follow-up and baseline, respectively (no control group reported): 86% vs 98% for β blocker or a calcium antagonist, 88% vs 94% for statin, 96% vs 100% for antiplatelet, 62% vs 82% for ACEI/ARB, 76% vs 92% for 4D | |

| Yilmaz, 2005 (Turkey)24 | Secondary prevention in hospital | RCT | 202 | Intervention=counselling regarding efficacy, pharmacokinetic profile, and side effects of ongoing statins | Persistence to statin therapy at 15 months (median follow-up) Self-report |

62.7% vs 46%; OR=1.98, 1.13 to 3.47; p=0.017 | |

| Hospital quality improvement programmes | Bushnell, 2011 (USA)30 | Ischaemic stroke/TIA in hospital | Retrospective cohort | 2457 | Guideline implementation in the Adherence eValuation After Ischemic stroke–Longitudinal (AVAIL) Registry in a sample of hospitals participating in the Get With The Guidelines—Stroke program | Persistence and adherence to 4D at 1 year Self-report |

Persistence and adherence associated with: number of medications prescribed at discharge (OR=1.08, 1.04 to 1.11; p<0.001 per 1 decrease); and follow-up appointment with GP (OR=1.72, 1.12 to 2.52; p=.0.006) |

| Jackevicius, 2008 (Canada)31 | AMI in hospital | Retrospective cohort | 4591 | Quality improvement of care in the Enhanced Feedback for Effective Cardiac Treatment (EFFECT) study registry in Ontario | Adherence to 4D at 120 days Prescription fill rate |

Predischarge medication counselling: OR 1.61, 1.26 to 2.04; p=0.0001 Cardiologist (vs GP) as doctor responsible for patient's care: OR 1.80, 1.34 to 2.43; p=0.0001. Teaching versus other hospital: OR 1.35,0.93 to 1.97; p=0.11 |

|

| Johnston, 2010 (USA)19 | Ischaemic stroke in hospital | RCT | 3361 | Intervention: assistance in the development and implementation of standardised stroke discharge orders | Adherence to statin at 6 months Prescription fill rate |

Intervention versus non-intervention hospitals, At hospital level: OR, 1.26; 0.70 to 2.30; p=0.36. At individual level: OR, 1.29; 1.04 to 1.60; p=0.02 |

|

| Khanderia, 2005 (USA)40 | CABG in hospital | Retrospective case–control | 403 | A physician education protocol to implement statin in all patients admitted for CABG | Persistence to statins at 6 months Self-report |

Intervention versus control: 67% vs 58%, OR 1.49, 0.88 to 2.55; p=0.14 | |

| Site of care and home circumstances of patients | Glader, 2010 (Sweden)32 | Acute stroke in hospital | Prospective cohort | 21 077 | A 1-year cohort (September 2005–August 2006) from the Swedish Stroke Register | Persistence with 4D at 1 year Prescription fill rate |

Institutional living correlated with persistence for all drug classes (p=0.001). Stroke unit care was associated with persistence for statins (p=0.007). Support by next-of-kin associated with persistence for antihypertensives (p=0.001) |

| Generic versus branded drugs | O'Brien, 2015 (USA)37 | NSTEMI in hospital | Retrospective cohort | 1421 | NSTEMI patients ≥65 years old discharged on a statin in 2006 from USA hospitals | Adherence to statins at 1 year Prescription refill rate |

Generic versus brand users: 86.0% (IQR=42.6–97.2%) vs 84.1% (IQR=53.4–97.0%)), (p=0.97) |

| Complexity of treatment regimen | Castellano, 2014 (Argentina, Brazil, Italy, Paraguay and Spain)25 | Aged >40 years with AMI in last 2 years | Cross-sectional study | 2118 | In a single visit, data was gathered to estimate prescription, adherence and barriers to adherence for aspirin, ACEIs, β blockers and statins | Adherence to 4D Self-report |

Non-adherence was associated with age <50 years (OR 1.50, 95% CI 1.08 to 2.09; p=0.015), depression (OR 1.07, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.09; p<0.001), being on a complex medication regimen (OR 1.42, 95% CI 1.00 to 2.02: p=0.047) and lower level of social support (OR 0.94 0.92 to 0.96; p<0.001) |

| FDC | Thom, 2013 (India, Europe)20 | High CV risk | RCT | 1698 | Intervention=FDC (containing either: 75 mg aspirin, 40 mg simvastatin, 10 mg lisinopril, and 50 mg atenolol or 75 mg aspirin, 40 mg simvastatin, 10 mg lisinopril and 12.5 mg hydrochlorothiazide) | Adherence to 4D at 15 months Self-report |

FDC versus separate medications: RR 1.29, 95% CI 1.22 to 1.36; p<0.0001 |

| FDC | Castellano, 2014 (Argentina, Brazil, Italy, Paraguay and Spain)25 | Aged >40 years with AMI within last 2 years. | RCT | 695 | Intervention=FDC (containing aspirin 100 mg, simvastatin 40 mg and ramipril 2.5, 5 or 10 mg) | Adherence at 9 months Self-report and pill count |

FDC versus separate medications: RR 1.24, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.47; p=0.009 |

| Selak, 2014 (New Zealand)28 | High CV risk | RCT | 233 | Intervention=FDC (with two versions available: aspirin 75 mg, simvastatin 40 mg and lisinopril 10 mg with either atenolol 50 mg or hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg) | Adherence to 4D at 12 months Self-report |

FDC versus separate medications: RR 1.50, 95% CI 1.25 to 1.82; p<0001 | |

| Patel, 2015 (Australia, New Zealand)26 | High CV risk | RCT | 381 | Intervention=FDC (containing aspirin 75 mg, simvastatin 40 mg, lisinopril 10 mg and either atenolol 50 mg or hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg) | Adherence to 4D at 18 months (median follow-up) Self-report |

FDC versus separate medications: RR 1.26, 95% CI 1.08 to 1.48; p<0001 | |

| Physician education/training | Ko, 2005 (Canada)18 | AMI aged ≥65 years in hospital | Retrospective cohort | 63 301 | Evaluation on whether care by International medical graduates (IMGs) is a determinant of poor persistence and worse outcomes after AMI versus care by Canadian medical graduates (CMGs) | Persistence to 4D at 90 days Prescription refill |

Adjusted OR(Canadian/IMG): aspirin 1.00 95% CI (0.94 to 1.06); BB 1.01 (0.94 to 1.08); ACEI 1.07 (1.01 to 1.14); statins 1.10 (1.01 to 1.20) |

| Harats, 2005 (Israel)33 | CHD in hospital | Cross-sectional and prospective Cohort | 2994 | Brief educational sessions with physicians to review National guidelines to ascertain physician's awareness | Persistence to statins at 8 weeks Self-report |

Intervention versus control: 57% vs 45%. (p<0.001) | |

| Copayments for medical care | Winkelmayer, 2007 (Austria)34 | AMI in hospital | Retrospective cohort | 4105 | The association between copayments and outpatient use of β blockers, statins, and ACEI/ARB in Austrian MI patients | Adherence at 120 days Prescription refill rate |

Adherence (waived copayments versus copayment): OR 1.35; 95% CI 1.10 to 1.67 for ACEI/ARB, OR 1.09; 0.89 to 1.35) for β blocker and OR 1.09;0.89 to 1.34 for statin |

| Ye, 2007 (USA)35 | CHD and hospital-initiated statin | Retrospective cohort | 5548 | Databases containing inpatient admission, outpatient, enrollment and pharmacy claims from 1999 to 2003 to study associations with copayments | Adherence to statins at 1 year Prescription refill rate |

Adherence (copayment ≥US$20 vs copayment <US$10): OR 0.42; 95% CI 0.36 to 0.49 | |

| Insurance and prescription cost assistance | Choudhry, 2011 (USA)27 | AMI in hospital | RCT | 5855 | Intervention=full prescription coverage by insurance-plan sponsor | Adherence to 4D at 394 days (median follow-up) Prescription refill rate |

Full-coverage versus usual coverage: OR 1.41, 95% CI 1.18 to 1.56; p<0.001 for 4D and p<001 for all individual drug classes |

| Mathews, 2015 (USA)38 | ACS in hospital | Prospective cohort | 7955 | Within the Treatment with Adenosine Diphosphate Receptor Inhibitors: Longitudinal Assessment of Treatment Patterns and Events after Acute Coronary Syndrome (TRANSLATE-ACS) study | Persistence to 4D at 6 months Self-report |

Non-persistence less likely with private insurance (OR 0.85, 95% CI 0.76 to 0.95), prescription cost assistance (OR 0.63, 0.54 to 0.75), and clinic follow-up arranged predischarge (OR 0.89, 0.80 to 0.99) |

4D, secondary prevention drugs for CVD, namely, antiplatelets, β blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin-receptor blockers and statins; ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; ACS, acute coronary syndrome; ARB, angiotensin-receptor blocker; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CHD, coronary heart disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; FDC, fixed-dose combination therapy; GP, general practitioner; NSTEMI, non ST-elevation myocardial infarction; RCT, randomised controlled intervention trial; RR, relative risk; TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

Table 3.

Risk of bias of included studies (trials)

| Study (author, year, setting) | Context | Study design | Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Risk of bias assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O'Carroll, 2013 (UK)21 | First stroke/TIA | RCT | + | + | - | - | + | + | High risk of bias: performance and detection |

| Hornnes, 2011 (Denmark)22 | Acute stroke/TIA | RCT | + | + | − | + | + | + | High risk of bias: performance |

| McManus, 2009 (UK)23 | Stroke in hospital | RCT | + | + | + | + | + | + | Low risk of bias |

| Faulkner, 2000 (USA)17 | CABG | RCT | + | − | − | − | + | + | High risk of bias: selection, performance and detection |

| Hohmann, 2009 (Germany)29 | Ischaemic stroke/TIA in hospital | Non-randomised controlled intervention trial | − | − | − | − | + | + | High risk of bias: selection, performance and detection |

| Yilmaz, 2005 (Turkey)24 | Secondary prevention in hospital | RCT | ? | − | − | − | + | + | High risk of bias: selection, performance and detection |

| Johnston, 2010 (USA)19 | Ischaemic stroke in hospital | RCT | + | + | − | − | + | + | High risk of bias: performance and detection |

| Thom, 2013 (India, Europe)20 | High CV risk | RCT | + | + | ? | ? | + | + | Unclear risk of bias: performance and detection |

| Castellano, 2014 (Argentina, Brazil, Italy, Paraguay and Spain)25 | Aged >40 years with AMI within last 2 years | RCT | + | + | ? | ? | + | + | Unclear risk of bias: performance and detection |

| Selak 2014 (New Zealand)28 | High CV risk | RCT | + | + | + | + | + | + | Low risk of bias |

| Patel, 2015 (Australia, New Zealand)26 | High CV risk | RCT | + | + | ? | ? | + | + | Unclear risk of bias: performance and detection |

| Choudhry, 2011 (USA)27 | AMI in hospital | RCT | + | + | ? | ? | + | + | Unclear risk of bias: performance and detection |

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CHD, coronary heart disease; CV, cardiovascular; CVD, cardiovascular disease; RCT, randomised controlled intervention trial; TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

Table 4.

Risk of bias of included observational studies

| Study (author, year, setting) | Context | Study design | Bias |

Risk of bias assessment | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | DM | ND | C | ||||

| Maron, 2010 (USA and Canada)39 | Stable CHD | Prospective cohort | Low | Low | Low | High | High risk of confounding |

| Lafitte, 2009 (France)36 | ACS in hospital | Prospective cohort | High | High | High | High | High risk of bias |

| Bushnell, 2011 (USA)30 | Ischaemic stroke/TIA in hospital | Retrospective cohort | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low risk of bias |

| Jackevicius, 2008 (Canada)31 | AMI in hospital | Retrospective cohort | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low risk of bias |

| Khanderia, 2005 (USA)40 | CABG in hospital | Retrospective case–control | High | Low | Low | High | High risk of bias |

| Glader, 2010 (Sweden)32 | Acute stroke in hospital | Prospective cohort | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low risk of bias |

| O'Brien, 2015 (USA)37 | NSTEMI in hospital | Retrospective cohort | Low | Low | Low | High | Low risk of bias, but high risk of confounding |

| Castellano, 2014 (Argentina, Brazil, Italy, Paraguay and Spain)25 | Aged >40 years with AMI within last 2 years | Cross-sectional study | High | Low | Low | High | High risk of bias—selection bias and confounding |

| Ko, 2005 (Canada)18 | AMI aged ≥65 years in hospital | Retrospective cohort | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low risk of bias but unclear risk of confounding |

| Harats, 2005 (Israel)33 | CHD in hospital | Cross-sectional then prospective cohort | Low | High | Low | High | High risk of bias due to differential misclassification and confounding |

| Winkelmayer, 2007 (Austria)34 | AMI in hospital | Retrospective cohort | Low | Low | Low | High | Low risk of bias but high risk of confounding |

| Ye, 2007 (USA)35 | CHD and initiated statin in hospital | Retrospective cohort | Low | Low | Low | High | Low risk of bias but high risk of confounding |

| Mathews, 2015 (USA)38 | ACS in hospital | Prospective cohort | Low | Low | Low | High | Low risk of bias but high risk of confounding |

Bias: S, selection; DM, differential misclassification; ND, non-differential misclassification; C, confounding. AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CHD, coronary heart disease; NSTEMI, non-ST elevation myocardial infarction; ACS, acute coronary syndrome; TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

Included study characteristics

In total, there were 132 140 individuals in the 25 studies, with the smallest study of n=3017 and the largest study of n=63301.18 Of the 25 included studies, 11 were randomised controlled trials (RCTs);17 19–28 1 was a non-randomised trial,29 11 were cohort studies,18 30–39 1 was cross-sectional25 and 1 was case–control.40 Other than 3 studies including upper middle-income countries24 25 and one including a low middle-income country,20 21 of the 25 studies (84%) were conducted in countries classified as high-income countries, 9 of which were in the USA.17 19 27 30 35 37–40 Studies included individuals with cerebrovascular disease (n=7),19 21–23 29 30 32 established CVD or an estimated 5-year CVD risk of ≥15% (n=4)20 24 26 28 and coronary heart disease (from stable CHD, to acute myocardial infarction (AMI), to coronary artery bypass graft (CABG)) (n=14).17 18 25 27 31 33–40

Thirteen studies included aspirin, β blocker, ACEI/ARB, and statin.18 20 23 25–28 30–32 36 38 39 Two studies investigated antihypertensive medication, including β blockers and ACEI/ARB,21 22 and seven studies included only statins.17 19 24 33 35 37 40 One study focused on antiplatelet drugs including aspirin.29 One study investigated β blockers, statins and ACEI/ARB34 and one considered aspirin, ACEI and statin25 (see online supplementary appendix table 2c).

In 16 studies, indirect measures of adherence were employed: prescription refill rates (medication possession ratio (MPR),27 35 proportion of days covered (PDC)37 and other measures),17 19 31 34 electronic pill bottle count,21 manual pill count25 and self-report.20 22 23 25 26 28 39 Persistence was measured in 11 studies, by self-report23 24 29 30 33 36 38–40 or prescription refill.18 32 Three studies considered persistence and adherence.23 30 39

Nineteen of 25 included studies were concerned with governance and delivery (table 1).17 19–26 28–32 36 37 39 40 Only one study, based in Canada, considered human resource implications on adherence to medication in a retrospective cohort design.18 Only one study considered intellectual resources (impact of physician education on medication adherence) in patients admitted with CHD in Israel.33 Health financing was considered in four studies in the USA27 35 38 and Austria,34 respectively. No studies examined the role of physical or social resources in medication adherence.

Quality of included studies

Only 2 of the 12 included trials were deemed to have low risk of bias,23 28 and 2 had an unclear degree of bias.20 25 Remaining trials had high risk of bias in one or several domains, most commonly due to lack of blinding of participants, personnel or outcomes (table 3). Three included observational studies had low risk of bias in all domains30–32 (table 4). Although meta-analysis was not undertaken, funnel plot asymmetry suggests possible publication bias (see online supplementary appendix figure 1).

Barriers

Complexity of treatment regimen

A cross-sectional study of individuals with myocardial infarction (MI) in the last 2 years in South America/Europe showed that taking more than 10 pills (p=0.047) and a complex regimen (eg, taking medications other than orally) (p=0.017) were associated with self-reported non-adherence. However, only a complex regimen was independently predictive of non-adherence (OR 1.42, 1.00 to 2.02; p=0.047).25

Copayments for medical care

Two retrospective cohort studies investigated the impact of copayments on adherence. Both studies had low risk of bias but high risk of confounding. Among 4105 patients with acute MI in Austria,34 those with waived copayments had higher persistence at 120 days for ACEI/ARB than those with copayments (OR 1.35, 95% CI 1.10 to 1.67), but β blocker (OR 1.09, 0.89 to 1.35) or statin use (OR 1.09, 0.89 to 1.34) did not differ between these groups. The second US study of CHD patients35 found that compared with copayment <US$10, copayment ≥US$20 was associated with lower persistence at 1 year for statins (OR 0.42; 0.36 to 0.49, p<0.001).

Insurance and prescription cost assistance

A US-based prospective cohort study of 7955 MI patients in 216 hospitals showed that non-persistence to secondary prevention medications was less likely with private insurance (OR 0.85, 95% CI 0.76 to 0.95) and prescription cost assistance (OR 0.63, 95% CI 0.54 to 0.75).38 A US-based RCT included 5855 individuals post-MI, randomised to full or usual prescription coverage.27 Full adherence was higher with full prescription coverage for all medication classes (OR 1.41, 1.18 to 1.67; p<0.001). Increased adherence to all three medications for the patient subgroup undergoing CABG was found, post hoc (OR 1.67, 95% CI 1.04 to 2.67; p=0.03).41

Facilitators

Patient counselling

Patient counselling was the most investigated facilitator of adherence/persistence (table 2). Only one study investigated impact of physician-led counselling following first stroke/transient ischaemic attack (TIA). This UK RCT included 62 individuals, with high risk of bias overall21 (table 3). At 3 months, adherence to antihypertensive medication was higher in the intervention group for doses taken on schedule (ie, mean difference, 9.8%; 95% CI (0.2 to 16.2); p=0.048).

Three studies considered nurse-led interventions in a total of 2738 individuals in Denmark, the USA/Canada and the UK, respectively,22 23 39 with high risk of bias in the Danish study and high risk of confounding in the American study (table 3). The Danish study randomised stroke/TIA patients to four home visits with nurse-led counselling, finding no difference in self-reported adherence at 1 year between intervention and control groups (98% vs 99%, respectively, OR 0.88, 95% CI 0.54 to 1.44; p=0.50).22 The North American study assigned nurse case managers to patients with stable CHD over a 5-year period, nested within a trial of percutaneous coronary intervention and optimal medical therapy versus optimal medical therapy alone.39 Persistence increased from baseline to 5 years across all drug categories, including all four drugs together (28% to 53%, OR 2.90, 95% CI 2.44 to 3.43; p<0.001). Self-reported adherence was not different between groups (97% at 6 months and 95% at 5 years, respectively). Lack of a control group limited study findings. In the UK-based RCT,23 patients who had stroke were randomised to nurse-led counselling sessions for 3 months. At 3 years, persistence and adherence were not different between groups (table 2).

Two studies investigated pharmacist-led counselling of patients: one RCT in the USA17 and one non-randomised trial in Germany.29 The US trial included 30 patients following CABG, randomised to weekly pharmacist telephone calls for 3 months or usual care. Adherence to statins was higher in the intervention group versus the control group at 1 year (71% vs 47%; p<0.05) and at 2 years (63% vs 39%) as measured by prescription refill, using the χ2 test. However, the effect was not statistically significant using ORs at 1 year (OR 4.00, 0.88 to 18.26; p=0.07) or 2 years (OR 4.13, 0.88 to 19.27; p=0.07). In the German trial, a hospital pharmacist delivered predischarge counselling to 255 stroke/TIA patients was compared with usual care. At 1 year, persistence was 38.7% vs 32.7%, OR 1.30, 0.73 to 2.31; p=0.37) for aspirin and 30.1% and 26.7% (p=0.60) for clopidogrel, in intervention versus control groups, respectively.

Two studies reported on the delivery of comprehensive health counselling in hospital-based patients.24 36 In a secondary prevention population of 202 individuals already on statins, a Turkish RCT24 found that comprehensive counselling was associated with increased adherence compared with usual care (62.7% vs 46%; OR=1.98; p=0.017) after a median follow-up of 15 months. Bias due to contamination was likely as patients were already taking statins. In France, a prospective cohort study without the control group invited 660 patients 3 months after acute coronary syndrome for comprehensive risk factor management with a cardiologist.36 Persistence was 86% vs 98% for β blocker/calcium antagonist, 88% vs 94% for cholesterol-lowering medication, 96% vs 100% for antiplatelet, 62% vs 82% for ACEI/ARB and 76% vs 92% for antiplatelet, β blocker and cholesterol-lowering medications combined at follow-up (mean 20 months) and baseline, respectively (all p<0.0001). This study had high risk of bias across the domains of differential misclassification, non-differential misclassification and confounding.

Hospital-level quality improvement

In this section, studies at the level of the hospital or a whole health system were considered. All four studies of hospital-level quality improvement were conducted in North America (three in the USA,19 30 40 one in Canada)31 with one RCT, two cohort studies and one case–control study (table 1). The case–control study and RCT had high risk of bias (tables 3 and 4). The RCT found that hospital-level assistance in the development and implementation of standardised stroke discharge orders was not associated with improved adherence over 12 months at the hospital level (57.3% vs 62.9%; OR 1.26, 95% CI 0.70 to 2.30; p=0.36), although there was improvement in adherence to statins at the individual level (OR 1.29, 1.04 to 1.60; p=0.02).19

One retrospective cohort study in acute MI patients in Canada31 showed that predischarge medication counselling (76.0% vs 64.8%; OR 1.61, 1.26 to 2.04; p=0.0001) and having a cardiologist (vs general practitioner) responsible for patient care were associated with adherence at 120 days postdischarge (34.5% vs 25.4%; OR 1.80, 1.34 to 2.43; p=0.0001), with no association with treatment at a teaching hospital (14.8% vs 11.8%; OR 1.35, 0.93 to 1.97; p=0.11). In a retrospective cohort study of stroke/TIA patients in the USA,30 12-month persistence with secondary prevention medications was associated with fewer medications (OR=1.04, 1.02 to 1.06, p<0.001 per one medication decrease); in-patient rehabilitation (13.4% vs 21.6%; OR=0.57, 0.43 to 0.76, p<0.001); primary care follow-up (92.1% vs 88.4%; OR=1.47, 1.05 to 2.07, p=.0.027) and neurology follow-up (43.3% vs 35.0%; OR=1.20, 1.03 to 1.41, p=0.023). Fewer medications (OR=1.08, 1.04 to 1.11, p<0.001 per 1 decrease) and primary care follow-up (OR=1.72, 1.12 to 2.52, p=0.006) were associated with persistence and adherence. A retrospective case–control study of CABG patients found that a physician education protocol was not associated with improved adherence to statins at 6 months.40

Site of care and home circumstances of patients

A Swedish prospective cohort study of patients who had stroke32 found that institutional living was correlated with persistence of all secondary prevention medications (p=0.001). Stroke unit care was associated with persistence for statins (p=0.007), and next-of-kin support was associated with persistence for antihypertensives (p=0.001).

Generic versus branded medication prescription

A US retrospective, hospital-based cohort study of individuals post-NSTEMI (non-ST elevation myocardial infarction) investigated 1-year statin adherence by prescription of generic versus branded medications.37 Although patient copayment amounts were higher for brand versus generic statins (median=US$25 vs US$5, p<0.001), there was no statistically significant difference in adherence over 1 year (71.5% vs 68.9%, unadjusted OR 1.15, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.37; p=0.97).

Fixed-dose combination therapy

Four RCTs examined fixed-dose combination therapy (FDC).20 25 26 28 One RCT in Europe and India in 1698 individuals with established CVD demonstrated that FDC (either aspirin/simvastatin/lisinopril/atenolol or hydrochlorothiazide) was associated with higher self-reported adherence than routine therapy (RR 1.29, 95% CI 1.22 to 1.36; p<0.0001).20 In 695 individuals in Argentina, Brazil, Italy, Paraguay and Spain, FDC (containing aspirin/simvastatin/ramipril) was compared with the three drugs given separately in individuals with MI in the last 2 years.25 Adherence (by self-report and pill count) was higher with FDC (RR 1.24, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.47; p=0.009). A trial in Australia/New Zealand compared FDC (containing aspirin/simvastatin/lisinopril/atenolol or hydrochlorothiazide) with usual care in 381 individuals with established CVD. Self-reported adherence was higher with FDC (RR 1.49; 95% CI 1.30 to 1.72; p<0.0001).26 A further trial in New Zealand compared FDC (containing aspirin/simvastatin/lisinopril/atenolol or hydrochlorothiazide) with usual care in 233 individuals with established CVD.28 Self-reported adherence was greater with FDC (RR 1.75, 95% CI 1.52 to 2.03, p<0.001). Of the four trials, only the New Zealand RCT had low risk of bias with the other three having unclear risk of performance and detection biases (table 3).

Physician education/training

Among 63 301 acute MI patients, there was no significant difference in medication persistence at 90 days between patients treated by non-Canadian versus Canadian graduates for aspirin (OR 1.00, 0.94 to 1.06) or β blocker (OR 1.01, 0.94 to 1.08). There was increased persistence in the non-Canadian medical graduate-treated group for ACEI (OR 1.07, 1.01 to 1.14) and statins (OR 1.10, 1.01 to 1.20), compared with patients treated by Canadian medical graduates.18 The relevance of these findings is reduced by the low ORs, a plausible mechanism for differential effect on different drugs and the unclear risk of confounding. In a hospital-based study of CHD patients in Israel, an educational programme for physicians increased self-reported persistence to statins at 8 weeks follow-up (57% vs 45% at follow-up; p<0.001). However, there was high risk of differential misclassification bias and confounding.

Persistence and adherence

Adherence was assessed across studies from 3 months to 5 years (see online supplementary appendix table 1a). The three studies with follow-up ≥2 years did not show increased adherence.17 23 39 FDC consistently increased adherence across four RCTs with follow-up at between 9 and 18 months.20 25 26 28 Copayments, insurance and prescription coverage were all associated with increased adherence from 120 days to 1 year.27 34 35

Two RCTs23 24 and one non-randomised trial29 had persistence outcomes, and only one RCT showed a positive impact of counselling on statin persistence at 15 months median follow-up24 (see online supplementary table 1b). The only trial considering persistence and adherence did not show effect on these outcomes.23 Nurse-led case management was associated with increased persistence at 5 years but not increased adherence.39

Different medication classes

Of the studies considering all four classes of secondary prevention medications, FDC and prescription coverage were supported by RCT evidence.20 26–28 The two RCTs of counselling on antihypertensive therapy had conflicting findings.21 22 Overall, there were insufficient numbers of studies considering individual classes of medications and lack of consistency of findings within the existing studies to suggest varying effects of interventions across different classes of medications.

Discussion

The World Heart Federation's ‘25 by 25’ strategy to tackle the CVD epidemic and specifically its recent roadmap for secondary prevention give context to our four key findings.12 First, at health systems level, there is lack of high-quality evidence on barriers and facilitators (especially from low and low-middle income countries) to adherence and persistence for the most well-established therapies available for secondary prevention of CVD. The only barriers with available data were complexity of treatment regimen and health financing. Several potential facilitators have been considered but not in a coordinated manner for adherence and persistence, or different classes of drugs. Second, FDC therapy is associated with increased adherence. Third, reduced copayments and full prescription coverage were associated with increased adherence and persistence. Finally, counselling of patients whether by doctor, nurse or pharmacist can result in improved adherence to secondary prevention CVD medications.

There is high-quality evidence to support use of aspirin, ACEIs/ARBs, β blockers and statins in secondary prevention of CVD.9 42 However, a recent analysis of Cochrane reviews and RCTs in non-communicable diseases (including CVD) showed that almost 90% of trials and over 80% of participants were from high-income countries,43 and our analysis further highlights the sparse data for policymakers to make evidence-based changes to improve adherence to secondary prevention medications for CVD, particularly in low-income settings. The overall quality of evidence is low by objective criteria,44 due to lack of directness of evidence, heterogeneity across studies and only 12 (48%) of the 25 included studies being RCTs. There were no studies in low-income countries and only one study in an upper middle-income country, and two studies included a lower middle-income country.20 24 Moreover, there were neither quantitative studies regarding physical resources and social resources nor qualitative studies of adherence to secondary CVD prevention medications. As well as limited study numbers, heterogeneity in study design, study populations, study quality, health system arrangements and outcomes make meta-analysis and synthesis of the available data extremely challenging. Given the lack of large-scale and generalisable data to support changes in health systems to improve adherence to medications for CVD, policymakers can take advantage of context-specific information, including quantitative data. We were unable to find any qualitative studies meeting our inclusion criteria, but this particular study design may be informative in understanding local context for patients, healthcare providers and policymakers.

The imbalance between efficacy research (eg, pharmacologic trials with ‘hard’ clinical outcomes) and policy-oriented implementation research (eg, adherence) is well documented in CVD and other diseases.45–47 The World Heart Federation's Roadmap has emphasised the “‘treatment effectiveness cascade’ from the cardiovascular event to the long-term adherence with priority interventions”.12 This systematic review illustrates that, particularly in low-income settings, the understanding of health system barriers and facilitators is poor from a research perspective, and that practical research and pragmatic solutions are urgently required, if the World Heart Federation's goals of reducing premature CVD mortality by at least 25% by 2025 are to be fulfilled.

Poor adherence to prescribed therapy has been estimated to account for at least 9% of CVD events in Europe alone,48 and optimal adherence is associated with better outcomes in CVD.49 Importantly, FDC therapy has been shown to improve adherence in other diseases including hypertension50 and HIV/AIDS.51 FDC therapy may improve adherence in CVD secondary prevention on the basis of four trials,20 25 26 28 but the results of several other trials are awaited and there is still uncertainty whether FDC therapy influences long-term outcomes.25 52 There are concerns regarding the exact combination and dose of medications in FDC therapy, as shown by variations in combinations used in the trials included in our review, but this strategy may standardise supply and use of the component medications,53 leading to calls for its inclusion in the WHO essential medicines list.54

The secondary prevention medications investigated in this review are off-patent and likely to be the most widely available medications for treatment of CVD. However, we show that lower or no copayment was still associated with higher adherence to therapy in CVD, as illustrated by previous analyses.55 56 These findings echo the conclusions of prior analyses of health system financing in other disease areas,57 suggesting as with FDC therapy, that in the field of adherence to CVD drug therapy, there is scope for research, practice and policy to cross disease boundaries, especially in low-income countries. Universal healthcare coverage has been emphasised in the sustainable development goals,58 offering opportunities and challenges to embed full prescription coverage for secondary prevention for CVD in cross-sectoral approaches, which research and global health player must embrace.

Global shortage of health workers is a threat to provision of healthcare including CVD prevention.59 The finding that counselling of patients, regardless of the profession of the health worker, can result in improved adherence to secondary prevention CVD medications has significance in the context of international debate about universal health coverage and task shifting of health workers. Unlike other disease areas, the implementation of task-shifting strategies for CVD is lacking in an evidence base in low-income settings,60 and this should be a focus of future research in secondary CVD prevention and improvement strategies for medication adherence.

Limitations

This study, like any systematic review, was limited by inclusion criteria, and we restricted our study to secondary prevention medications for CVD. The initiation and use of medications was not studied, only studies of adherence and persistence were included and therefore not all barriers and facilitators to appropriate medication use were investigated in this analysis. Only published literature was considered. We were able to include only 25 studies in our systematic review as already discussed. The studies could not be weighted by relative relevance of each of these results as they are context limited. However, the interventions recommended by this review are unlikely to be dependent on context. Meta-analysis was not possible due to heterogeneity in several respects. We did not assess conflict of interest. Conclusions with respect to particular barriers and facilitators, drug class and persistence versus adherence were limited by the number of studies available. Generalisability of findings is questionable, suggesting that a common methodology for studies of medication adherence (and persistence) in CVD and other diseases is required, as well as urgent need for research in low-income settings.

Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review of health system influences on adherence to evidence-based secondary prevention therapies in CVD. Lack of generalisable, high-quality evidence to inform policy to improve adherence highlights the pressing need for research, particularly in low-income countries. Full prescription coverage and reduced copayments, FDC therapy and patient counselling are supported by existing literature as strategies to improve adherence and are priorities for further research before implementation. Standardised definitions of and approaches to adherence and persistence are also required in consensus guidelines for management of CVD.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the help and support of the World Heart Federation Emerging Leaders Programme and particularly Mark Huffman and Darwin Labarthe who commented on earlier drafts of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Amitava Banerjee at @amibanerjee1

Contributors: All coauthors contributed to the idea and methodology of the systematic review, as well as the search, study selection and data extraction. AB conducted the initial analyses and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All coauthors contributed to interpretation of data and the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: World Heart Federation Emerging Leaders Programme.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Any requests for data sharing should be made to the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Mensah GA, Moran AE, Roth GA et al. . The global burden of cardiovascular diseases, 1990–2010. Glob Heart 2014;9:183–4. 10.1016/j.gheart.2014.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cook C, Cole G, Asaria P et al. . The annual global economic burden of heart failure. Int J Cardiol 2014;171:368–76. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.12.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muka T, Imo D, Jaspers L et al. . The global impact of non-communicable diseases on healthcare spending and national income: a systematic review. Eur J Epidemiol 2015;30:251–77. 10.1007/s10654-014-9984-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kankeu HT, Saksena P, Xu K et al. . The financial burden from non-communicable diseases in low- and middle-income countries: a literature review. Health Res Policy Syst 2013;11:31 10.1186/1478-4505-11-31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beaglehole R, Bonita R, Lancet NCD Action Group. Tackling NCDs: a different approach is needed. Lancet 2012;379:1873; author reply-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maher A, Sridhar D. Political priority in the global fight against non-communicable diseases. J Glob Health 2012;2:020403 10.7189/jogh.02.020403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joshi R, Jan S, Wu Y et al. . Global inequalities in access to cardiovascular health care: our greatest challenge. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52:1817–25. 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.08.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fuster V. Global burden of cardiovascular disease: time to implement feasible strategies and to monitor results. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;64:520–2. 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.06.1151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wald NJ, Law MR. A strategy to reduce cardiovascular disease by more than 80%. BMJ 2003;326:1419 10.1136/bmj.326.7404.1419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yusuf S, Islam S, Chow CK et al. . Use of secondary prevention drugs for cardiovascular disease in the community in high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries (the PURE Study): a prospective epidemiological survey. Lancet 2011;378:1231–43. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61215-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kotseva K, Wood D, De Bacquer D et al. . EUROASPIRE IV: a European Society of Cardiology survey on the lifestyle, risk factor and therapeutic management of coronary patients from 24 European countries. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2016;23:636–48 10.1177/2047487315569401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perel P, Avezum A, Huffman M et al. . Reducing premature cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in people with atherosclerotic vascular disease: the world heart federation roadmap for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Glob Heart 2015;10:99–110. 10.1016/j.gheart.2015.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yusuf S, Rangarajan S, Teo K et al. . Cardiovascular risk and events in 17 low-, middle-, and high-income countries. N Engl J Med 2014;371:818–27. 10.1056/NEJMoa1311890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maimaris W, Paty J, Perel P et al. . The influence of health systems on hypertension awareness, treatment, and control: a systematic literature review. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001490 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cramer JA, Roy A, Burrell A et al. . Medication compliance and persistence: terminology and definitions. Value Health 2008;11:44–7. 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00213.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J et al. . The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009;339:b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Faulkner MA, Wadibia EC, Lucas BD et al. . Impact of pharmacy counseling on compliance and effectiveness of combination lipid-lowering therapy in patients undergoing coronary artery revascularization: a randomized, controlled trial. Pharmacotherapy 2000;20:410–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ko DT, Austin PC, Chan BT et al. . Quality of care of international and Canadian medical graduates in acute myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:458–63. 10.1001/archinte.165.4.458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnston SC, Sidney S, Hills NK et al. . Standardized discharge orders after stroke: results of the quality improvement in stroke prevention (QUISP) cluster randomized trial. Ann Neurol 2010;67:579–89. 10.1002/ana.22019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thom S, Poulter N, Field J et al. . Effects of a fixed-dose combination strategy on adherence and risk factors in patients with or at high risk of CVD: the UMPIRE randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2013;310:918–29. 10.1001/jama.2013.277064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Carroll RE, Chambers JA, Dennis M et al. . Improving adherence to medication in stroke survivors: a pilot randomised controlled trial. Ann Behav Med 2013;46:358–68. 10.1007/s12160-013-9515-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hornnes N, Larsen K, Boysen G. Blood pressure 1 year after stroke: the need to optimize secondary prevention. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2011;20:16–23. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2009.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McManus JA, Craig A, McAlpine C et al. . Does behaviour modification affect post-stroke risk factor control? Three-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil 2009;23:99–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yilmaz MB, Pinar M, Naharci I et al. . Being well-informed about statin is associated with continuous adherence and reaching targets. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 2005;19:437–40. 10.1007/s10557-005-5202-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Castellano JM, Sanz G, Peñalvo JL et al. . A polypill strategy to improve adherence: results from the FOCUS project. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;64:2071–82. 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.08.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patel A, Cass A, Peiris D et al. . Kanyini Guidelines Adherence with the Polypill (Kanyini GAP) Collaboration. A pragmatic randomized trial of a polypill-based strategy to improve use of indicated preventive treatments in people at high cardiovascular disease risk. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2015;22:920–30. 10.1177/2047487314530382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choudhry NK, Avorn J, Glynn RJ et al. . Full coverage for preventive medications after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2011;365:2088–97. 10.1056/NEJMsa1107913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Selak V, Elley CR, Bullen C et al. . Effect of fixed dose combination treatment on adherence and risk factor control among patients at high risk of cardiovascular disease: randomised controlled trial in primary care. BMJ 2014;348:g3318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hohmann C, Klotz JM, Radziwill R et al. . Pharmaceutical care for patients with ischemic stroke: improving the patients quality of life. Pharm World Sci 2009;31:550–8. 10.1007/s11096-009-9315-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bushnell CD, Olson DM, Zhao X et al. . Secondary preventive medication persistence and adherence 1 year after stroke. Neurology 2011;77:1182–90. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31822f0423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jackevicius CA, Li P, Tu JV. Prevalence, predictors, and outcomes of primary nonadherence after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 2008;117:1028–36. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.706820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glader EL, Sjölander M, Eriksson M et al. . Persistent use of secondary preventive drugs declines rapidly during the first 2 years after stroke. Stroke 2010;41:397–401. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.566950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harats D, Leibovitz E, Maislos M et al. . Cardiovascular risk assessment and treatment to target low density lipoprotein levels in hospitalized ischemic heart disease patients: results of the HOLEM study. Isr Med Assoc J 2005;7:355–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Winkelmayer WC, Bucsics AE, Schautzer A et al. . Use of recommended medications after myocardial infarction in Austria. Eur J Epidemiol 2008;23:153–62. 10.1007/s10654-007-9212-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ye X, Gross CR, Schommer J et al. . Association between copayment and adherence to statin treatment initiated after coronary heart disease hospitalization: a longitudinal, retrospective, cohort study. Clin Ther 2007;29:2748–57. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2007.12.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lafitte M, Pradeau V, Leroux L et al. . Efficacy over time of a short overall atherosclerosis management programme on the reduction of cardiovascular risk in patients after an acute coronary syndrome. Arch Cardiovasc Dis 2009;102:51–8. 10.1016/j.acvd.2008.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O'Brien EC McCoy LA, Thomas L et al. . Patient adherence to generic versus brand statin therapy after acute myocardial infarction: insights from the Can Rapid Stratification of Unstable Angina Patients Suppress Adverse Outcomes with Early Implementation of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Guidelines Registry. Am Heart J 2015;170:55–61. 10.1016/j.ahj.2015.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mathews R, Wang TY, Honeycutt E et al. . TRANSLATE-ACS Study Investigators. Persistence with secondary prevention medications after acute myocardial infarction: insights from the TRANSLATE-ACS study. Am Heart J 2015;170:62–9. 10.1016/j.ahj.2015.03.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maron DJ, Boden WE, O'Rourke RA et al. . Intensive multifactorial intervention for stable coronary artery disease: optimal medical therapy in the COURAGE (Clinical Outcomes Utilizing Revascularization and Aggressive Drug Evaluation) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:1348–58. 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.10.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khanderia U, Townsend KA, Eagle K et al. . Statin initiation following coronary artery bypass grafting: outcome of a hospital discharge protocol. Chest 2005;127:455–63. 10.1378/chest.127.2.455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kulik A, Desai NR, Shrank WH et al. . Full prescription coverage versus usual prescription coverage after coronary artery bypass graft surgery: analysis from the post-myocardial infarction Free Rx Event and Economic Evaluation (FREEE) randomized trial. Circulation 2013;128:S219–25. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wiley B, Fuster V. The concept of the polypill in the prevention of cardiovascular disease. Ann Glob Health 2014;80:24–34. 10.1016/j.aogh.2013.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heneghan C, Blacklock C, Perera R et al. . Evidence for non-communicable diseases: analysis of Cochrane reviews and randomised trials by World Bank classification. BMJ Open 2013;3:pii:e003298 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA et al. . Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2004;328:1490 10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Amsterdam EA, Laslett L, Diercks D et al. . Reducing the knowledge-practice gap in the management of patients with cardiovascular disease. Prev Cardiol 2002;5:12–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rebello TJ, Marques A, Gureje O et al. . Innovative strategies for closing the mental health treatment gap globally. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2014;27:308–14. 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sturke R, Harmston C, Simonds RJ et al. . A multi-disciplinary approach to implementation science: the NIH-PEPFAR PMTCT implementation science alliance. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014;67(Suppl 2):S163–7. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chowdhury R, Khan H, Heydon E et al. . Adherence to cardiovascular therapy: a meta-analysis of prevalence and clinical consequences. Eur Heart J 2013;34:2940–8. 10.1093/eurheartj/eht295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ho PM, Bryson CL, Rumsfeld JS. Medication adherence: its importance in cardiovascular outcomes. Circulation 2009;119:3028–35. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.768986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gupta AK, Arshad S, Poulter NR. Compliance, safety, and effectiveness of fixed-dose combinations of antihypertensive agents: a meta-analysis. Hypertension 2010;55:399–407. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.139816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ramjan R, Calmy A, Vitoria M et al. . Systematic review and meta-analysis: patient and programme impact of fixed-dose combination antiretroviral therapy. Trop Med Int Health 2014;19:501–13. 10.1111/tmi.12297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.de Cates AN, Farr MR, Wright N et al. . Fixed-dose combination therapy for the prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;4:CD009868 10.1002/14651858.CD009868.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yusuf S, Attaran A, Bosch J et al. . Combination pharmacotherapy to prevent cardiovascular disease: present status and challenges. Eur Heart J 2014;35:353–64. 10.1093/eurheartj/eht407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huffman MD, Yusuf S. Polypills: essential medicines for cardiovascular disease secondary prevention? J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:1368–70. 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.08.1665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lemstra M, Blackburn D, Crawley A et al. . Proportion and risk indicators of nonadherence to statin therapy: a meta-analysis. Can J Cardiol 2012;28:574–80. 10.1016/j.cjca.2012.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sanfélix-Gimeno G, Peiró S, Ferreros I et al. . Adherence to evidence-based therapies after acute coronary syndrome: a retrospective population-based cohort study linking hospital, outpatient, and pharmacy health information systems in Valencia, Spain. J Manag Care Pharm 2013;19:247–57. 10.18553/jmcp.2013.19.3.247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Boyer S, Clerc I, Bonono CR et al. . Non-adherence to antiretroviral treatment and unplanned treatment interruption among people living with HIV/AIDS in Cameroon: Individual and healthcare supply-related factors. Soc Sci Med 2011;72:1383–92. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.02.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schmidt H, Gostin LO, Emanuel EJ. Public health, universal health coverage, and sustainable development goals: can they coexist? Lancet 2015;386:928–30. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60244-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tsolekile LP, Abrahams-Gessel S, Puoane T. Healthcare professional shortage and task-shifting to prevent cardiovascular disease: implications for low- and middle-income countries. Curr Cardiol Rep 2015;17:115 10.1007/s11886-015-0672-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ogedegbe G, Gyamfi J, Plange-Rhule J et al. . Task shifting interventions for cardiovascular risk reduction in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005983 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

openhrt-2016-000438supp_appendix.pdf (486.1KB, pdf)