Abstract

A 55-year-old man was working in a trench when the wall collapsed in on him, pinning him to the wall. On arrival in the emergency department the patient began reporting of right-sided headache. Neurological examination revealed left-sided reduced sensation with weakness. Whole-body CT scan showed right-sided flail chest and bilateral haemothorax as well as loss of flow and thinning of the distal right internal carotid artery (ICA) and loss of grey white matter differentiation in keeping with traumatic ICA dissection with a right middle cerebral artery (MCA) infarct. He was started on aspirin 300 mg once daily. 3 days postadmission the patient experienced worsening of vision and expressive dysphasia. CT angiogram showed bilateral ICA dissections extending from C2 to the skull base. The patient was managed conservatively in the stroke unit for infarction and was discharged home for follow-up in stroke clinic.

Background

Carotid artery dissection (CAD) is relatively rare, with an incidence between 2.5 and 3 per 100 000/year.1 2 While only 4% of these dissections are secondary to traumatic injury, traumatic dissections account for 10–25% of ischaemic cerebral events in younger patients.3–6

Traumatic internal carotid artery (ICA) dissections are often overlooked life-threatening injuries.7 Only 10% of patients with traumatic ICA dissections display immediate symptoms. Therefore, the diagnosis is often delayed due to missed initial symptoms and distracting injuries. Moreover, treatment may prove difficult when combined with other traumatic injuries.6 Bilateral ICA dissection secondary to blunt trauma is extremely rare, and exact data on its incidence do not exist in the literature.

Case presentation

A 55-year-old Caucasian male was working in a trench when the wall of clay and soil collapsed in on him, pinning him to the wall below the level of the clavicles. He was extracted by his colleagues within 2 min and was sitting up and talking when the ambulance crew arrived at the scene. His Glasgow Coma Scale was 15 until arrival in the emergency department (ED), at which point it dropped to 14 (E3). He reported of right-sided chest pain and a chest X-ray revealed multiple bilateral rib fractures and right-sided pneumothorax. The patient subsequently began reporting of right-sided headache with numbness down his left side; neurological examination revealed left-sided reduced sensation with weakness (0/5).

A whole-body trauma CT scan (head, neck, chest, abdomen and pelvis) was ordered which showed a small right apical pneumothorax, a moderate haemothorax and multiple right-sided rib fractures. The fractures involved the right posterior 1st–3rd and 6–11th and right anterior 2nd–8th ribs, resulting in radiological flail chest and pulmonary contusions were seen in the right base. There were also undisplaced fractures of the left 1st, 6–7th ribs with a small left haemothorax. Contrast was added for the CT scan head and cervical spine (C-spine), due to suspicion of cerebral ischaemia secondary to a traumatic dissection, which revealed loss of flow and thinning of the distal right ICA at the skull base and loss of grey white matter differentiation in keeping with traumatic ICA dissection with a right middle cerebral artery (MCA) infarct (figure 1).

Figure 1.

CT scan brain with contrast showing loss of grey white matter differentiation within the right frontal lobe and right insula suggestive of a hyperacute infarct.

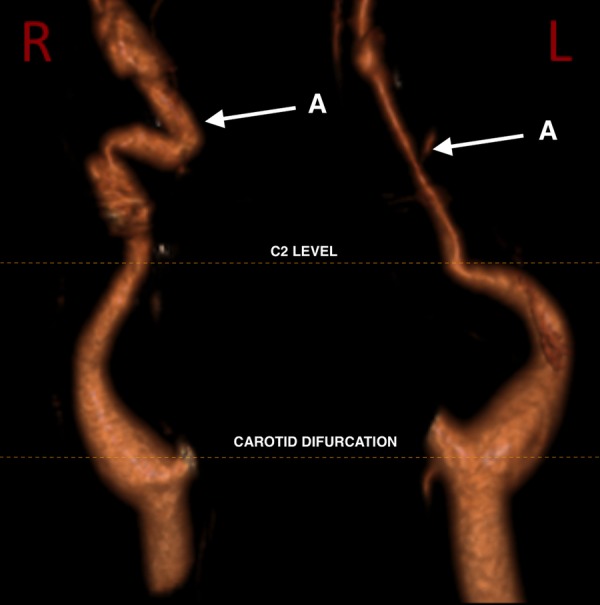

Results of the scan were discussed with neuroradiologists who advised that the thrombus was too distal in the M2 branches for interventional treatment to be considered. The stroke team recommended treating with 300 mg aspirin once daily for 14 days in accordance with the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines for the management of acute stroke;8 this was also discussed with the cardiothoracic surgeons in light of the existing haemothorax. Three days postadmission the patient experienced worsening of vision and expressive dysphasia. Carotid artery Doppler showed low velocity, high resistance flow in the left extracranial ICA and CT angiogram (figure 2) showed bilateral ICA dissections extending from C2 to skull base with luminal narrowing maximal at skull base (90% stenosis on the right and >95% stenosis on the left using North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial (NASCET) criteria). CT scan head showed no radiographic evidence of left-sided ischaemia. However, angiography demonstrated small posterior communicating arteries bilaterally, with the potential for inadequate collateral perfusion of any compromised anterior circulation territory.

Figure 2.

Volume-rendered CT angiogram showing bilateral ICA dissections extending from C2 to skull base with distal stenosis (A).

Treatment

The patient was managed conservatively in the stroke unit for infarction, and chest injury was managed with patient controlled analgesia and a chest drain. He was reviewed throughout admission by the speech and language and occupational health teams with regards to his neurological rehabilitation and made good progress. He was discharged home on prophylactic clopidogrel 75 mg once daily in line with NICE guidelines for the long-term management of stroke and followed up as an outpatient in the stroke clinic.8

Outcome and follow-up

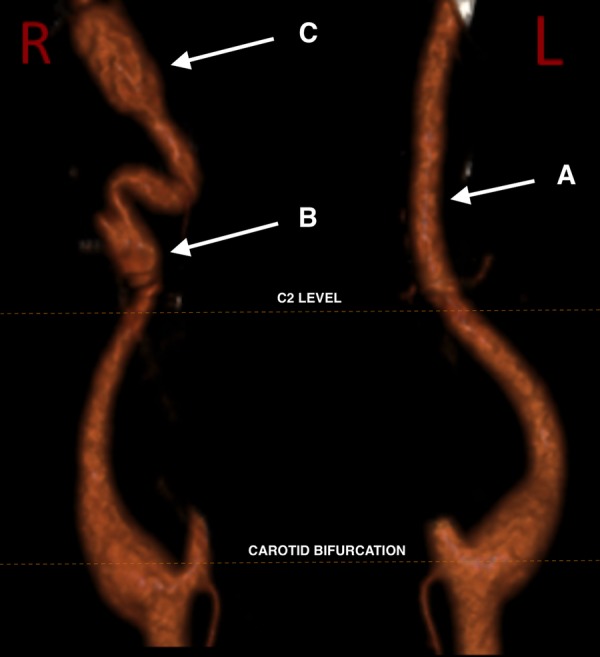

The patient was reviewed in stroke clinic 2 months postdischarge with some residual, but improving, altered sensation on the left arm. CT angiogram (figure 3) showed complete remodelling of the left cervical ICA with normal appearance. However, there was persistent tortuosity of the right cervical ICA with a shallow dissecting aneurysm at the C1/2 level and a larger, saccular dissecting aneurysm at the skull base. The larger dissecting aneurysm was resulting in a significant degree of stenosis at the level of the distal aneurysm outflow.

Figure 3.

Volume-rendered CT angiogram demonstrating complete remodelling on the left (A) but persisting irregularity on the right with a shallow dissecting aneurysm at the C1/2 level (B) and a larger, saccular dissecting aneurysm at the skull base (C).

Discussion

CAD occurs when a tear in the tunica intima of the vessel wall allows blood to dissect through to the tunica media under arterial pressure, separating the intima from the media and adventitia. A subintimal dissection may result in a propagating intramural haematoma with elongated luminal stenosis. Subadventitial dissection of the artery may result in aneurysmal dilation. Rarely, there is haematoma with no communication between false and true lumens, suggesting that in some cases, haematoma is the primary event with secondary dissection of the vessel wall.9 Most cases present with both stenotic and aneurysmal segments.10 11 If severe, these haematomas may completely or almost entirely occlude the lumen presenting as an angiographic ‘string sign’. Intracranial arteries are lacking an external elastic lamina and have a thinner adventitia, making them more prone to subadventitial dissection and subarachnoid haemorrhage. This most commonly occurs in intracranial vertebral artery dissection.9 These dissections may occur following traumatic injury or spontaneously, with no recognised aetiology.

Traumatic ICA dissections are often overlooked life-threatening injuries.7 The diagnosis of ICA dissection is often delayed due to distracting injuries or missed initial symptoms and treatment may prove difficult when combined with other traumatic injuries at risk of bleeding.6 Bilateral ICA dissection secondary to blunt trauma is extremely rare and exact data on its incidence do not exist in the literature.

Presentation

As in this case, typical presentation of ICA dissection is with headache and symptoms of cerebral ischaemia, most often in the MCA territory.12 Headaches occur in two-thirds of patients and usually occur gradually, but may be sudden and severe.13–16

Horner's syndrome in ICA dissection may occur from stripping of the vasa nervorum or interruption of the perivascular autonomic fibres and is typically partial, including meiosis and ptosis only, since facial sweat glands are innervated by sympathetic fibres surrounding the external carotid artery.17 18 Cranial nerve injuries occur in more than 10% of patients, with the hypoglossal nerve most frequently affected due to its anatomical association with the carotid vessels.4 19 Only 10% of patients with traumatic ICA dissections display immediate symptoms.6

Pathophysiology

Traumatic ICA dissection can be caused by violent movements of the head and neck such as attacks of coughing, sneezing or sudden deceleration. Dissections may also occur secondary to significant trauma, such as blunt trauma to the head and neck, direct arterial injury or intraluminal instrumentation.20 Vasocompression between the C-spine and mandible during a hyperflexion trauma, frequently seen in motor vehicle accidents during a sudden loss of speed, can lead to ICA dissection.7 21 A case of bilateral traumatic ICA dissection has recently been described in this context, suggesting that these mechanisms of trauma also have the potential to cause bilateral vessel injury.22 Traumatic dissections in the head and neck region are more likely to occur in mobile segments of vessels, and most frequently occur below the skull base.23 24

Diagnosis

MRI combined with MR angiography (MRA) is the gold standard for diagnosis because in addition to luminal diameter and flow, thrombus in the vessel wall can also be detected. MRI/MRA can simultaneously provide additional information about concomitant soft tissue injury and acute infarction but use in critically injured patients is limited by availability and contraindications such as pacemakers and lengthy scanning time.21 25

CT combined with CT angiography is much more widely available, which can be incorporated into trauma or stroke protocol and studies have shown sensitivity that is comparable to MRI with MRA.21 Helical CT scanning can collect large amounts of data with speed and can evaluate the entire extracranial arterial system. Despite limitations with vessel wall assessment, variations in vessel diameter, luminal diameter and intraluminal thrombus can be assessed.

Duplex ultrasonography has been used in the diagnosis of ICA dissections; however, in addition to being largely operator dependent, there are numerous restrictions to its use. First, stenosis of over 50% is required to support a diagnosis of dissection on ultrasound,26 and stenosis is not pathognomonic of dissection.27 In addition, most CADs are located distally to the carotid bifurcation, an area not well visualised by ultrasound.27 The utility of ultrasound in the emergency setting is in screening for those patients who require more diagnostic imaging, and as an additional method for evaluating the progress of a dissection.21 28 29

Treatment

A significant proportion of ICA dissections will resolve without intervention; the aims of treatment are therefore to reduce the incidence and degree of neurological deficit and to restore cerebral circulation.4 30

Multiple methods have been used in the treatment of cerebrovascular dissections including symptomatic treatment, observation, antiplatelet therapy, anticoagulant therapy, endovascular management (stenting, stent-assisted endovascular thrombolysis, stent-assisted thrombectomy) and surgery (microsurgical vessel sutures, extracranial/intracranial bypass, thromboendarterectomy).21 28 There is, however, no good evidence highlighting the effectiveness of these therapies for ICA dissections or comparing any method with the other.

Once blood is exposed to the subintimal arterial wall, intrinsic clotting factors are activated resulting in intraluminal thrombus and thromboembolic phenomenon.4 While some cerebral ischaemic symptoms are a result of poor poststenotic perfusion, most are secondary to embolic events.7 21 31 Therefore, management of ICA dissection focuses on minimising these events through anticoagulant or antiplatelet treatment for at least 3 months postdissection.32 Swift implementation of therapy reduces the likelihood of embolic events originating from the dissection.

Whether antiplatelet or anticoagulation agents are superior in the management of ICA dissection remains unclear.33–35 Anticoagulation is widely advocated, and often used.17 36 37 However, there is no reliable evidence from randomised trials for the efficacy of this treatment, nor trials comparing anticoagulation with antiplatelet therapy.4 38 Therapy is often chosen based on the type of lesion and physician preference.

Surgical intervention is both difficult and risky in the acute phase of dissection, and therefore does not comprise part of the first-line therapy.21 39 Intravascular stents have been used with some success in patients with dissecting aneurysms and stenosis.40 However, there is no good evidence for stenting, and further randomised trials with high levels of incidence are needed to evaluate this therapeutic option.7 28 If this intervention is shown to be effective, it may have considerable impact on the management of ICA dissection.

In all events, when ICA dissection exists alongside other traumatic injuries at high risk of severe bleeding, as in this case, the timing and method of treatment should be made with an interdisciplinary approach.

Outcome

A total of 85–90% of ICA dissections will improve or resolve clinically, or on imaging, following effective management.31 Headache improves in 95% of patients.41 Dissections recur in <10% of patients within a month and following this, they recur at a rate of 1% per year.42 Mortality is predominantly <5%.31

Conclusion

The aetiology of our patient's bilateral ICA dissection remains unclear. We assume that the trauma that occurred when the patient was pinned against the wall of the trench caused the patients C-spine to be subject to distraction/flexion or distraction/extension forces that may have caused the traumatic dissection of the ICA. These are forces similar to those experienced during high-speed MVAs, a mechanism of injury recently reported to cause bilateral traumatic ICA dissection, lending further support to this hypothesis. The earlier CT angiogram (figure 2) shows aneurysmal dilation of the extracranial right ICA, which is temporally earlier than one would expect if the aetiology is considered to be related to trauma. While a spontaneous bilateral ICA dissection is unlikely, we must consider the possibility of an underlying pathology causing the vessels to be more prone to dissection in the context of trauma.

This case highlights the importance of considering ICA dissection in patients who present with headache and symptoms of cerebral ischaemia with a history of trauma. Accurate diagnosis can be made with appropriate imaging modalities. Timely diagnosis followed by antiplatelet therapy may reduce the likelihood of neurological sequelae associated with ICA dissection. In our patient with other traumatic injuries at risk of bleeding, the time to start the antiplatelet therapy was considered in the context of a multidisciplinary approach (trauma surgeons, vascular surgeons, neuroradiologists). Conservative, non-surgical management with antiplatelet therapy can yield results equivalent to surgical intervention when dissections involving segments of ICA extending into the intracranial portion of the artery makes direct surgery or stenting hazardous.

Learning points.

Internal carotid artery (ICA) dissection should be considered in all patients who present with headache as well as symptoms of cerebral ischaemia with a history of trauma.

CT angiography of the neck region should be included in the initial CT trauma scan.

Sites of haemorrhage should be addressed quickly, and antiplatelet or anticoagulative therapy should be initiated as soon as possible.

Prompt diagnosis followed by antiplatelet therapy can yield results equivalent to surgical intervention when dissections involving segments of ICA extending into the intracranial portion of the artery makes direct surgery or stenting hazardous.

An interdisciplinary approach to treatment including trauma surgeons and neuroradiologists is crucial.

Randomised controlled trials are needed to accurately compare methods of treatment for ICA dissections in the acute setting.

Footnotes

Contributors: JMJ and JN were involved in the acquisition of key clinical information, drafting of the manuscript, revisions and final approval. RW was involved in the acquisition of key clinical information, revision of the manuscript and final approval. TH was involved in the acquisition of patient images, revision of the manuscript and final approval.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Giroud M, Fayolle H, André N et al. . Incidence of internal carotid artery dissection in the community of Dijon. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1994;57:1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schievink WI, Mokri B, Whisnant JP. Internal carotid artery dissection in a community. Rochester, Minnesota, 1987–1992. Stroke 1993;24:1678–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mokri B, Sundt TM Jr, Houser OW. Spontaneous internal carotid dissection, hemicrania, and Horner's syndrome. Arch Neurol 1979;36:677–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schievink WI. Spontaneous dissection of the carotid and vertebral arteries. N Engl J Med 2001;344:898–906. 10.1056/NEJM200103223441206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leys D, Bandu L, Hénon H et al. . Clinical outcome in 287 consecutive young adults (15 to 45 years) with ischemic stroke. Neurology 2002;59:26–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marschner-Preuth N, Warnecke T, Niederstadt TU et al. . Juvenile stroke: cervical artery dissection in a patient after a polytrauma. Case Rep Neurol 2013;5:21–5. 10.1159/000347001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lenz M, Bula-Sternberg J, Koch T et al. . [Traumatic dissection of the internal carotid artery following whiplash injury. Diagnostic workup and therapy of an often overlooked but potentially dangerous additional vascular lesion]. Unfallchirurg 2012;115:369–76. 10.1007/s00113-011-2130-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions. Stroke: national clinical guideline for diagnosis and initial management of acute stroke and transient ischaemic attack (TIA). London, UK: Royal College of Physicians, 2008. [PubMed]

- 9.Biller J, Sacco RL, Albuquerque FC et al. , American Heart Association Stroke Council. Cervical arterial dissections and association with cervical manipulative therapy: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American heart association/American stroke association. Stroke 2014;45:3155–74. 10.1161/STR.0000000000000016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stein DM, Boswell S, Sliker CW et al. . Blunt cerebrovascular injuries: does treatment always matter? J Trauma 2009;66:132–43; discussion 143–4 10.1097/TA.0b013e318142d146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schievink WI, Piepgras DG, McCaffrey TV et al. . Surgical treatment of extracranial internal carotid artery dissecting aneurysms. Neurosurgery 1994;35:809–15; discussion 815–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baumgartner RW, Bogousslavsky J. Clinical manifestations of carotid dissection. Front Neurol Neurosci 2005;20:70–6. 10.1159/000088151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fassett DR, Dailey AT, Vaccaro AR. Vertebral artery injuries associated with cervical spine injuries: a review of the literature. J Spinal Disord Tech 2008;21:252–8. 10.1097/BSD.0b013e3180cab162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silbert PL, Mokri B, Schievink WI. Headache and neck pain in spontaneous internal carotid and vertebral artery dissections. Neurology 1995;45:1517–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saeed AB, Shuaib A, Al-Sulaiti G et al. . Vertebral artery dissection: warning symptoms, clinical features and prognosis in 26 patients. Can J Neurol Sci J 2000;27:292–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thanvi B, Munshi SK, Dawson SL et al. . Carotid and vertebral artery dissection syndromes. Postgrad Med J 2005;81:383–8. 10.1136/pgmj.2003.016774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hart RG, Easton JD. Dissections of cervical and cerebral arteries. Neurol Clin 1983;1:155–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baumgartner RW, Arnold M, Baumgartner I et al. . Carotid dissection with and without ischemic events: local symptoms and cerebral artery findings. Neurology 2001;57:827–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mokri B, Silbert PL, Schievink WI et al. . Cranial nerve palsy in spontaneous dissection of the extracranial internal carotid artery. Neurology 1996;46:356–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Redekop GJ. Extracranial carotid and vertebral artery dissection: a review. Can J Neurol Sci 2008;35:146–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jansen G, Popp J, Dietrich U et al. . [Traumatic dissection of the carotid artery: challenges for diagnostics and therapy illustrated by a case example]. Anaesthesist 2013;62:817–23. 10.1007/s00101-013-2243-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crönlein M, Sandmann GH, Beirer M et al. . Traumatic bilateral carotid artery dissection following severe blunt trauma: a case report on the difficulties in diagnosis and therapy of an often overlooked life-threatening injury. Eur J Med Res 2015;20:62 10.1186/s40001-015-0153-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Downer J, Nadarajah M, Briggs E et al. . The location of origin of spontaneous extracranial internal carotid artery dissection is adjacent to the skull base. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol 2014;58:408–14. 10.1111/1754-9485.12170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okada Y, Shima T, Nishida M et al. . Traumatic dissection of the common carotid artery after blunt injury to the neck. Surg Neurol 1999;51:513–19. Discussion 519–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vertinsky AT, Schwartz NE, Fischbein NJ et al. . Comparison of multidetector CT angiography and MR imaging of cervical artery dissection. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2008;29:1753–60. 10.3174/ajnr.A1189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sturzenegger M. Ultrasound findings in spontaneous carotid artery dissection. The value of duplex sonography. Arch Neurol 1991;48:1057–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kasner SE, Hankins LL, Bratina P et al. . Magnetic resonance angiography demonstrates vascular healing of carotid and vertebral artery dissections. Stroke 1997;28:1993–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mohan IV. Current optimal assessment and management of carotid and vertebral spontaneous and traumatic dissection. Angiology 2014;65:274–83. 10.1177/0003319712475154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tahmasebpour HR, Buckley AR, Cooperberg PL et al. . Sonographic examination of the carotid arteries. Radiographics 2005;25:1561–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Flis CM, Jäger HR, Sidhu PS. Carotid and vertebral artery dissections: clinical aspects, imaging features and endovascular treatment. Eur Radiol 2007;17:820–34. 10.1007/s00330-006-0346-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mokri B. Spontaneous dissections of internal carotid arteries. Neurologist 1997;3:104–19. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Caplan L. Nonatherosclerotic ischemia. In: Caplan LR, ed. Stroke: a clinical approach. 2nd edn. Newton, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1993:299–305. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lyrer P, Engelter S. Antithrombotic drugs for carotid artery dissection. Stroke 2004;35:613–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lyrer PA. Extracranial arterial dissection: anticoagulation is the treatment of choice: against. Stroke 2005;36:2042–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Norris JW. Extracranial arterial dissection: anticoagulation is the treatment of choice: for. Stroke 2005;36:2041–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cimini N, D'Andrea P, Gentile M et al. . Cervical artery dissection: a 5-year prospective study in the Belluno district. Eur Neurol 2004;52:207–10. 10.1159/000082037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Menon RK, Markus HS, Norris JW. Results of a UK questionnaire of diagnosis and treatment in cervical artery dissection. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2008;79:612 10.1136/jnnp.2007.127639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leys D, Lucas C, Gobert M et al. . Cervical artery dissections. Eur Neurol 1997;37:3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rao AS, Makaroun MS, Marone LK et al. . Long-term outcomes of internal carotid artery dissection. J Vasc Surg 2011;54:370–4; discussion 375 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.02.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marks MP, Dake MD, Steinberg GK et al. . Stent placement for arterial and venous cerebrovascular disease: preliminary experience. Radiology 1994;191:441–6. 10.1148/radiology.191.2.8153318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mokri B, Sundt TM, Houser OW et al. . Spontaneous dissection of the cervical internal carotid artery. Ann Neurol 1986;19:126–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schievink WI, Mokri B, O'Fallon WM. Recurrent spontaneous cervical-artery dissection. N Engl J Med 1994;330:393–7. 10.1056/NEJM199402103300604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]