Abstract

Introduction

We are undertaking a randomised controlled trial (fAmily led rehabiliTaTion aftEr stroke in INDia, ATTEND) evaluating training a family carer to enable maximal rehabilitation of patients with stroke-related disability; as a potentially affordable, culturally acceptable and effective intervention for use in India. A process evaluation is needed to understand how and why this complex intervention may be effective, and to capture important barriers and facilitators to its implementation. We describe the protocol for our process evaluation to encourage the development of in-process evaluation methodology and transparency in reporting.

Methods and analysis

The realist and RE-AIM (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation and Maintenance) frameworks informed the design. Mixed methods include semistructured interviews with health providers, patients and their carers, analysis of quantitative process data describing fidelity and dose of intervention, observations of trial set up and implementation, and the analysis of the cost data from the patients and their families perspective and programme budgets. These qualitative and quantitative data will be analysed iteratively prior to knowing the quantitative outcomes of the trial, and then triangulated with the results from the primary outcome evaluation.

Ethics and dissemination

The process evaluation has received ethical approval for all sites in India. In low-income and middle-income countries, the available human capital can form an approach to reducing the evidence practice gap, compared with the high cost alternatives available in established market economies. This process evaluation will provide insights into how such a programme can be implemented in practice and brought to scale. Through local stakeholder engagement and dissemination of findings globally we hope to build on patient-centred, cost-effective and sustainable models of stroke rehabilitation.

Trial registration number

CTRI/2013/04/003557.

Keywords: QUALITATIVE RESEARCH, REHABILITATION MEDICINE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A strength of our study protocol includes the use of implementation theories, quantitative and qualitative research methods and our iterative approach to analysis.

Consideration of costs to the patient is vital to assess whether a programme would be affordable outside a trial setting, which is often inadequately reported in trials. The design of this process evaluation allowing the triangulation of within-trial cost data and qualitative data will add to the limited current evidence regarding the socioeconomic burden of stroke to patients and their families in India.

Limitations to our current approach include the overlap between the trial coordinating team and the process evaluation team. While a strength of this approach is that the team members have an in-depth knowledge of the trial and its implementation, a challenge for the process evaluation is for team members to be aware of their own biases in the conduct of the interviews for positive findings towards the trial.

Our sampling approach for the interviews has been designed to maximise variation which should increase our understanding of the differing contextual factors. Pragmatically this is only a small sample (about 100 participants) of a 1200 patient trial. However, this is a large sample for qualitative research, and other data sources such as observations, administratively collected data and relevant policies would be reviewed to provide additional context.

Introduction

With a rapidly rising global burden of disease attributed to non-communicable diseases, access to high-quality evidence-based healthcare is essential. Complex interventions, defined as interventions with multiple interacting components, are frequently deployed in an attempt to address health system deficiencies experienced by patients and providers.1 Process evaluations, which are typically carried out for trials of complex interventions, can help explain for whom, how and why the intervention had a particular impact.2 Such evaluations address the question ‘Is this intervention acceptable, effective and feasible (for me or) for this population?’3 Gaining a clear understanding of the causal mechanisms of complex interventions is vital in being able to scale up or deliver an effective intervention in other settings.

This is especially relevant for the randomised controlled trial known as the fAmily led rehabiliTaTion aftEr stroke in INDia (ATTEND), which is being conducted at 14 hospitals in India—across populations with differing languages, cultures and health systems.4–6 The annual incidence of stroke in India is estimated to be 152–262 cases per 100 000 population, with prevalence of 0.47–0.54%.7 This means that there is a significant burden on society due to stroke disability with limited stroke units isolated to urban areas and limited rehabilitation services.8 Table 1 highlights some socioeconomic health indicators and available stroke incidence data in different states where our sites are based.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic health indicators across the participating ATTEND sites

| City/state of participating sites | Life expectancy at birth (2002–2006)* (years) | Poverty level (2004–2005)* (%) | Per capita health expenditure (in Rs)* | Age-standardised incidence rate for stroke† (from population stroke epidemiology studies) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ludhiana, Punjab | 69.4 | 8.4 | 1359 | Not available |

| New Delhi, Delhi | Not available | Not available | Not available | Not available |

| Kochi and Trivandrum, Kerala | 74 | 15 | 2950 | 135/100 000 person-years |

| Guntur, Andhra Pradesh | 64.4 | 15.8 | 1061 | Not available |

| Chennai and Vellore, Tamil Nadu | 66.2 | 22.5 | 1256 | Not available |

| Kolkata, West Bengal | 64.9 | 24.7 | 1259 | 145/100 000 person-years |

| Tezpur, Assam | Not available | 19.7 | 774 | Not available |

| Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh | 64.4 | 15.8 | 1061 | Not available |

| Bangalore, Karnataka | 65.3 | 25 | 830 | Not available |

| INDIA | 63.5 | 27.5 | 1201 | 119–145 per 100 000 person-years |

*Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Annual report to the People on Health. December 2011.

†Pandian J, Suhan P. Stroke Epidemiology and stroke care services in India. J Stroke 2013;15(3):128–134.

ATTEND, fAmily led rehabiliTaTion aftEr stroke in INDia.

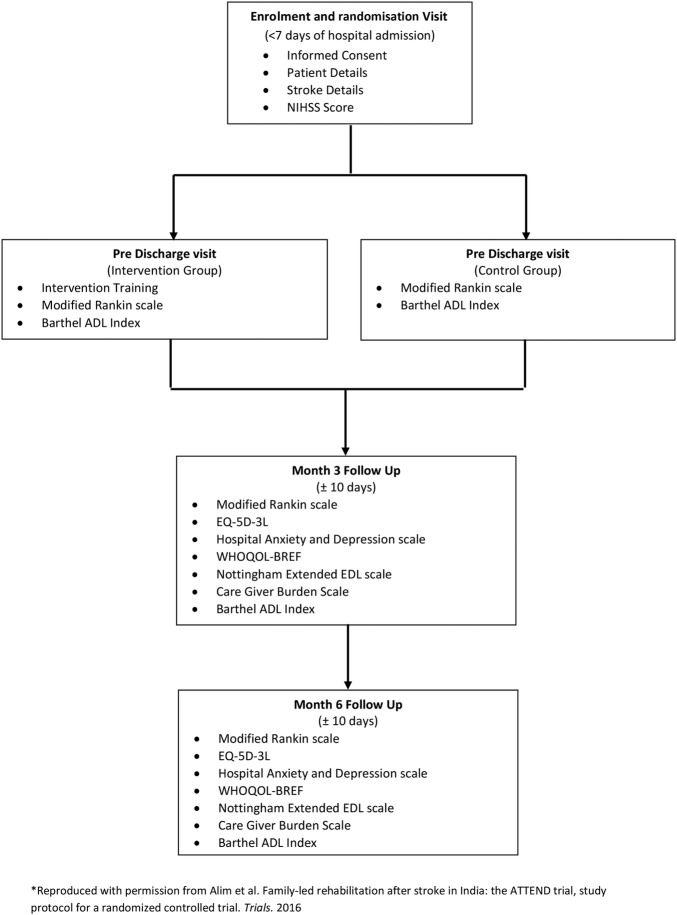

The ATTEND intervention has multiple interacting components. We developed an evidence-based rehabilitation intervention package consisting of providing information on stroke, identification and management of low mood, importance of repeated practice of specific activities, task-oriented training, early supported discharge planning and joint goal setting with the patient and nominated family. Physiotherapists employed for the trial are trained in this evidence-based rehabilitation intervention package.6 These physiotherapists (known as stroke coordinators in the trial) provide support to the patient and family within the hospital and in subsequent home visits, with the aim of training a nominated carer and in enabling optimal rehabilitation of the patient. As such, a careful consideration of the contextual patient factors, such as health literacy, access to care and financial considerations, is needed.9–11 The context of each patient can have an impact on the behaviour of the carer and the patient, which will affect patient improvement in disability and dependence outcomes as measured by the modified Rankin scale (mRS) and other outcome measures (see figure 1).6 Thus, the process evaluation could help explore reasons for any variations in trial effectiveness, and address questions about the generalisability of this intervention across different settings. A deeper appreciation of the needs of patients poststroke and their families will be valuable for health system and policy reform in India.4

Figure 1.

The ATTEND RCT flow chart. This highlights the outcome measures used and the study visits. ADL, activities of daily living; ATTEND, fAmily led rehabiliTaTion aftEr stroke in INDia; EQ-5D-3L, EuroQol 5-Dimensional, 3 Levels; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; RCT, randomised controlled trial; WHOQOL-BREF, WHO Quality of Life (Brief).

A key role of our process evaluation would be to inform how the intervention can be implemented into practice and policy, if proven effective. It is well recognised that the generation of good quality evidence does not always translate into improved patient health outcomes.12 Financial barriers, such as high out of pocket costs for diagnostic imaging or provision of treatment, are possible reasons for an intervention not being delivered once shown to be efficacious in a trial.13–16 Such costs are likely to frame the financial incentives of different players within the system and explain behaviour that is potentially at odds with the idealised operation of an intervention. Understanding these cost barriers can inform how remuneration and payment systems may be shaped to facilitate implementation beyond a trial setting.14 Incorporating an assessment of stakeholders' perceptions of how an intervention can be practically funded, delivered and scaled up is crucial.

Process evaluations can also add to the literature of how collaborations between stakeholders (ie, health providers, academics, policymakers, patients, carers) may facilitate research translation.17 Understanding how and why an international collaboration of stroke experts came together to design and implement a feasible, locally adapted large-scale trial in India would also be helpful for future research. Lessons learnt from this trial, which is funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia, with capacity building objectives in India, would be valuable in informing future international collaborative research.

The UK Medical Research Council (MRC) recommends publishing a protocol for a process evaluation so as to promote development of methodology and transparency in the reporting of the findings. In this protocol, we outline our aims, methods and study design. The core aims of this process evaluation are: (1) to explore if the ATTEND trial was delivered as intended (eg, fidelity and dose); (2) to understand whether, how and why the intervention had an impact, through exploring providers', patients' and carers' perspectives of their usual care and of the intervention; (3) and to explore if the results are likely to be generalisable, scalable and sustainable through exploring stakeholders' (hospital stroke unit staff, providers, patients and carers) experiences of the intervention and its perceived impact. This would include an evaluation of costs from the societal perspective, including the health system and also for the patients and families. Finally, (4) we aim to explore implementation barriers and facilitators of a complex intervention by an international collaboration.

Methods and analysis

Theoretical frameworks informing this process evaluation

Two theoretical frameworks with emphasis on translating evidence in the real-world setting were used to inform our methods.

The first was the RE-AIM (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation and Maintenance) framework. It has been used by researchers in the development, evaluation and dissemination of research, using qualitative and quantitative methods.18 The framework's five domains highlight the need to look into the proportion and representativeness of the participants involved in the intervention, the impact of the intervention, the fidelity of trial implementation and at how a programme may be institutionalised into organisational practice after the conclusion of the trial. Thus, pending ATTEND's results, and resources permitting, there may be scope for a post-trial evaluation to explore how and why there were changes in practice and policy.19

The second framework that informed our methods was the Realist framework (Context, Mechanism, Outcomes).20 It has been successfully used in process evaluations as a theoretical basis for identifying potential causal mechanisms for how an intervention works for whom, under what contexts and therefore fosters uptake of research-based knowledge into practice.21 22 Given the complexity of the ATTEND trial from contextual macrolevel factors, such as different socioeconomic demographics, cultural differences, health system funding structures at each state, to microlevel factors such as literacy of patients and carers; the realist framework would be valuable in framing our analysis in understanding the mechanism within the ‘black box’ of the intervention.23

Our process evaluation framework and the hypothesised causal mechanisms of ATTEND

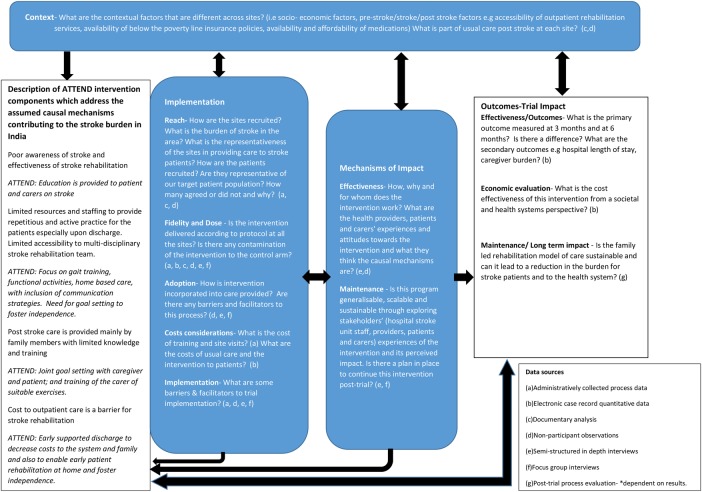

The framework (figure 2) highlights the key questions for the process evaluation, incorporating the above theories and our work plan. We have briefly outlined our hypothesised causal mechanisms of ATTEND's complex intervention within the framework as per the MRC's guidance on process evaluations.19 The framework is divided into sections of context, implementation of the trial, mechanisms of the trial and outcomes of the trial with the final objective of reducing the burden of stroke through a sustainable model of care.

Figure 2.

The ATTEND process evaluation framework. The process evaluation components are highlighted in blue boxes—exploring contextual factors, the implementation of the ATTEND trial, mechanisms of impact from the intervention. Questions informed by the RE-AIM and Realist framework fit within these components. These components are informed by the causal assumptions of ATTEND intervention and will inform the interpretation of the primary and secondary outcomes. ATTEND, fAmily led rehabiliTaTion aftEr stroke in INDia; RE-AIM, Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation and Maintenance.

Mixed methods used to address the aims of the process evaluation

To explore if the trial was delivered as intended (eg, fidelity and dose)

This will be achieved through an analysis of the administratively collected process data (eg, competency measures, frequency of training), electronic case record file, quantitative data and activity logs (eg, the measurement of the total time spent per patient in both arms of the trial with the usual care physiotherapist, the number of meetings and time spent with each family caregiver by the stroke coordinator during their inpatient stay and after discharge). If the analysis provides any evidence of variation between the active and control groups in terms of amount of time spent on different tasks, we will investigate and provide further training if required.

- To understand whether, how and why the intervention had an impact through exploring the providers', patients' and carers' perspectives of usual care and of the intervention

- Non-participant observations of all the sites to understand the contextual factors at each site, which may help explain variations in outcomes. Our observation template has been adapted from a process evaluation of a similar intervention24 and includes issues on trial set up, trial implementation and impact. See online supplementary additional file 1 for a copy of the template.

- Semistructured in-depth interviews will be conducted with patients, carers, stroke coordinators and the stroke unit staff of hospitals to understand their perspectives of the causal mechanisms of the intervention and to seek their suggestions on how the intervention could be scaled up or rolled out. Methods for our qualitative interviews have been described as per the consolidated criteria for qualitative research:25

- Research team and reflexivity: The research team is multidisciplinary and comprises of the trial's chief investigators, the clinical trial coordinating staff and research fellows from India, UK and Australia. The team has background in medicine, physiotherapy, health economics, pharmaceutical trials and public health; with varied experience in qualitative research. In particular, three of the team members (HL, MA and SJ) have training in qualitative methods. HL who coordinated the team, organised face-to-face qualitative workshops to train the rest of the team prior to the conduct of interviews and will take a leading role in analyses. A team of six people will conduct the interviews. The team members, who are part of the clinical trial management team, have a good understanding of the trial and are known to the principal investigators, stroke coordinators and blinded assessors but will not have established relationships with the patients and their carers.

Semistructured interview guidelines based on our study objectives have been developed and pilot tested. The key areas covered include overall views of the health and socioeconomic impact of stroke on patients and families, stroke management in India, acceptability of the family-led rehabilitation intervention, the general healthcare experience of patients and their families and translation of the intervention into practice and policy. Early findings will be discussed with the study team, and minor changes made to the interview guidelines if needed. (See online supplementary additional files 2–4 for the interview guidelines for the health provider, carer and patient, respectively.)

Study design: Sampling: Participants for the interviews will be recruited using maximum variation purposive sampling. Variables to be considered for patients and carers are: usual care versus intervention arm, primary outcome (as measured by the mRS at 6 months), gender and the region of India they are from. Variables to be considered for stroke unit providers: healthcare roles (ie, neurologists, physiotherapists, nurses and the stroke coordinators), private versus public government hospitals and the region of India the hospitals are located.

A list of patients and caregivers who match our sampling criteria will be generated. They will be contacted by the local site staff (either the stroke coordinator or the ‘blinded assessor’) and where relevant, reasons for not participating will be elicited. They will be formally consented by the interviewer face-to-face. Interviews with carers and patients will be conducted either individually or with both together either at the participant's home or at the hospital. These interviews will be conducted in local languages and the services of an interpreter may be required. The benefits of interviewing the patient and carer separately would be to gather perspectives which otherwise may not be shared should the other be present. Healthcare providers will be invited to participate in interviews either by a letter or in person by the clinical coordinating team during their site visits, and conducted in English. Written informed consent (see online supplementary additional file 5 for a copy of the form) will be obtained from all interviewed participants. As per qualitative research methods,26 analysis is iterative and thus the interviewer will carry out preliminary thematic data analysis at the end of each interview and discuss any highlights with the rest of the interview team. For example, the findings from the pilot interviews were discussed during the qualitative workshop, in order for the team of interviewers to explore emerging themes in subsequent interviews. It is estimated that at least five sites would be sampled, with 3–4 health providers and about 4–6 patient/carer dyads interviewed from each site. According to the sampling matrix, we will interview equal numbers from both usual care versus intervention arm, and also include sampling for gender. For example, at each site, two usual care dyads and two intervention group dyads will be invited to participate.

In addition, some of the stroke coordinators and the independent assessors at the other sites will be interviewed. That is, an estimated 80–100 interviews will be conducted though the final numbers will be determined by saturation of themes and resources permitting. Interviews will be conducted face-to-face, audio recorded and professionally translated and transcribed verbatim. These will be uploaded into a software program NVivo V.9 (QSR International, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia) to assist with data management.

- To explore if the results are generalisable, scalable and sustainable through exploring health providers', patients' and carers' experiences of the intervention and its perceived impact. This will include an evaluation of costs from the societal perspective including the health system, and for patients and their families. (note this is separate to the formal cost-effectiveness study which has been set out in the original trial protocol)6

- One of the key domains in the semistructured interviews will be exploring participants' perspectives of what they expect post-trial in relation to this intervention. The findings related to these questions will address this aim.

- Cost components of the intervention which will be relevant to implementation outside a trial setting will be considered. This will be extracted from the programme budget and trial contracts and includes, for example, costs of employment of a physiotherapist to implement the intervention, travel costs of the home visits and costs of any educational material required as part of the intervention. Relevant questions asked by the blinded assessor at the 3-month and 6-month follow-up visits include loss of family income (eg, number of hours of work taken off) due to carer's additional responsibility and medical costs. (Participants are encouraged to keep receipts of related medical costs.)

bmjopen-2016-012027supp1.pdf (189KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-012027supp2.pdf (431.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-012027supp3.pdf (317.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-012027supp4.pdf (317.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-012027supp5.pdf (296KB, pdf)

4 To explore implementation barriers and facilitators of a complex intervention by an international collaboration.

A research fellow not involved in the implementation of the trial will conduct focus group interviews and semistructured interviews with members of the clinical trial coordinating team and also with the trial investigators in regards to perceived barriers and facilitators to trial implementation. Findings from these interviews in addition to relevant findings from the interviews with the health providers, patients and carers will inform lessons learnt from this trial for future research collaborations.

Analysis plan for the process evaluation

Thematic analysis will be used for the qualitative analysis to code closely to the data and establish themes within the subheadings of the process evaluation framework (figure 2).26 Constant iterative comparison between sources, for example, patient, carer and health provider will be carried out in order to identify common, as well as distinctive, themes.26 Contextual information from observations, other process data and costs to patients and families will be used to triangulate the emerging themes.27 The quantitative process data will help inform fidelity and the time logs of the stroke coordinator will provide descriptive data on dose. Fidelity data will be reviewed at six monthly intervals.

The process evaluation framework (figure 2) will aid in the analysis by triangulating the process's quantitative data with the relevant qualitative data addressing the questions within its subheadings.27 For example, under the heading ‘implementation—fidelity and dose’, a specific question would be whether usual care is provided equally in both arms of the intervention, and thus the quantitative process data would be the time spent by the usual care physiotherapist and should be almost equivalent in both arms documented in the logs (or not), and the qualitative data would include, for example, the usual care physiotherapists' responses as to whether they did treat all the patients equally, or the neurologist's description of what happens to the study participants.

Other forms of triangulation to increase the reliability of our results include the sampling of different perspectives, that is, patient, carer, neurologists and stroke coordinators and also through the triangulation of different analysts in the team who bring their own cultural backgrounds, academic experience (eg, rehabilitation medicine, pharmacy, physiotherapy) and knowledge about different aspects of the trial into the analysis.26

In line with the MRC guidelines, the process evaluation data should be analysed prior to knowing the trial outcomes, first to remove bias, though there is a role for post hoc exploration of reasons for trial outcomes.2 First, we will analyse our process evaluation data iteratively on an ongoing basis. If there are any process issues which would impact on trial integrity that need to be addressed, these will be fed back through the usual management communication channels.28

The framework serves as a template to consolidate the findings, and will be a dynamic structure with changes to be made if required. This means that our understanding of the causal mechanisms of the intervention may change with the iterative analysis of the process evaluation data.

There will also be a post hoc examination of the process evaluation findings, in light of the main results of the trial.29 For example, in our experience, our assumption is that early supported discharge, as part of the intervention, will decrease costs to the system and family, enable early patient rehabilitation which may improve patient recovery (primary outcome) and result in shorter hospital stays in the intervention arm. However, in piloting our observation template at one site, we discovered that there was shortage of beds such that at that government hospital patients were discharged at the earliest possibility, for example, when they were medically stable. This may perhaps be different to developed country settings, such as UK, and ultimately may explain potential divergences in the findings of this study to that of a recent meta-analyses of rehabilitation trials (which showed positive results of early supported discharge).30 31 A major consideration in the process evaluation therefore may be regarding the length of stay in hospital. The examination of such secondary outcomes and contextual findings from the process evaluation is an example of how we could gain a deeper understanding of the assumed causal mechanisms of the ATTEND intervention (as depicted in the logic model in the overall process evaluation framework). Such insights will help inform the final logic model of how the intervention truly impacted the trial effectiveness outcomes, and inform the generalisability of the intervention.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics

Ethical approval for the trial and process evaluation has been obtained from Research Integrity, the Human Research Ethics Committee at the University of Sydney and at each local site. See online supplementary additional file 6 for the details of ethic committees at the local sites.

bmjopen-2016-012027supp6.pdf (177.6KB, pdf)

The ethical implications of this scope of research include the considerations of NHMRC ethical guidelines such as research merit and integrity, beneficence and respect in relation to qualitative methods.32

Dissemination

Our process evaluation aims to complement a robust blinded outcome evaluation of the trial end points and inform our stakeholders how, for whom and why this model of family led rehabilitation could have an impact. This is especially relevant for India which is in ‘epidemiological transition’ with a diverse sociodemographic profile, and an increasing burden from non-communicable diseases which could result in greater health inequity.4 16 A stated aim in India's key national strategy for non-communicable diseases is to increase access to healthcare to 80% with costs not being a key barrier. Strategies such as the family-led rehabilitation programme, which marshal family and community resources in the care of patients with chronic conditions will, by financial necessity, play a greater role in the future. In low-income and middle-income countries, the available human capital can form one approach to reducing the evidence practice gap, compared with the high cost alternatives available in established market economies. This process evaluation will provide insights into how such a programme can be implemented in practice and brought to scale.

The Indian Institute of Public Health has been allocated resources for the dissemination of results through the engagement of local policymakers and health practitioners. Apart from stakeholder engagement, dissemination of our findings globally will be accomplished through publishing our results in relevant journals and conferences to build on the literature in providing affordable, holistic and accessible stroke rehabilitation models of care.

We describe our protocol to encourage development in process evaluation methodology, transparency in reporting and to build on this emerging area of health services research which is much needed in addressing the complicated global health needs through sustainable, patient-centred and evidence-based complex interventions.

Trial status

In regards to the ATTEND trial, the first patient was randomised on 13 January 2014 and the recruitment surpassed the sample size of 1200 in January 2016. The ATTEND process evaluation, started in March 2015 with the observational visits of the sites and the fidelity and dose quantitative data have been reviewed in six monthly intervals since March 2015, pilot interviews were conducted with health providers in July 2015 and completion of the patient, carer and health provider interviews is expected by May 2016, with ongoing preliminary and iterative analysis.

Footnotes

Contributors: JDP suggested the original ATTEND trial idea and the steering committee (RL, GVSM, PKM, PL, LAH, MLH, MW, AF, BRS, CSA and SJ) designed the trial with a process evaluation in mind. HL developed this process evaluation protocol with extensive and significant contribution from the trial management team which includes MA, CF, DBCG, SJV, DKT, AS and RKR. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Funding: This study is funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (Project grant no APP1045391). PKM is a recipient of an Intermediate Career Fellowship of Wellcome Trust-Department of Biotechnology India Alliance. MLH is a recipient of a National Heart Foundation Future Leader Fellowship, Level 2 (100034, 2014–2017). SJ is the recipient of an NHMRC Senior Research Fellowship. CSA holds an NHMRC Senior Principal Research Fellowship. HL is the recipient of a NHMRC APP1114897 scholarship to undertake her doctorate.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Research Integrity, the Human Research Ethics Committee at the University of Sydney.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.World Health Organisation. The World Health Report- Research for Universal Health Coverage, 2013.

- 2.Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M et al. . Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2015;350:h1258 10.1136/bmj.h1258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonell C, Oakley A, Hargreaves J et al. . Assessment of generalisability in trials of health interventions: suggested framework and systematic review. BMJ 2006;333:346–9. 10.1136/bmj.333.7563.346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pandian JD, Sudhan P. Stroke epidemiology and stroke care services in India. J Stroke 2013;15:128–34. 10.5853/jos.2013.15.3.128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pandian JD, Felix C, Kaur P et al. . FAmily-Led RehabiliTaTion aftEr Stroke in INDia: the ATTEND pilot study. Int J Stroke 2015;10:609–14. 10.1111/ijs.12475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alim M, Lindley R, Felix C et al. . Family-led rehabilitation after stroke in India: the ATTEND trial, study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2016;17:13 10.1186/s13063-015-1129-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wasay M, Khatri IA, Kaul S. Stroke in South Asian countries. Nat Rev Neurol 2014;10:135–43. 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Langhorne P, Bernhardt J, Kwakkel G. Stroke rehabilitation. Lancet 2011;377:1693–702. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60325-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pandian JD, Kalra G, Jaison A et al. . Factors delaying admission to a hospital-based stroke unit in India. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2006;15:81–7. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2006.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pandian JD, Jaison A, Deepak SS et al. . Public awareness of warning symptoms, risk factors, and treatment of stroke in northwest India. Stroke 2005;36:644–8. 10.1161/01.STR.0000154876.08468.a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pandian JD, Kalra G, Jaison A et al. . Knowledge of stroke among stroke patients and their relatives in Northwest India. Neurology India 2006;54:152–6; discussion 6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tugwell P, Robinson V, Grimshaw J et al. . Systematic reviews and knowledge translation. Bull World Health Organ 2006;84:643–51. 10.2471/BLT.05.026658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tetroe JM, Graham ID, Foy R et al. . Health research funding agencies’ support and promotion of knowledge translation: an international study. Milbank Q 2008;86:125–55. 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2007.00515.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cordero C, Delino R, Jeyaseelan L et al. . Funding agencies in low- and middle-income countries: support for knowledge translation. Bull World Health Organ 2008;86:524–34. 10.2471/BLT.07.040386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evans DB, Edejer TT, Adam T et al. . Methods to assess the costs and health effects of interventions for improving health in developing countries. BMJ 2005;331:1137–40. 10.1136/bmj.331.7525.1137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pandian JD, Srikanth V, Read SJ et al. . Poverty and stroke in India: a time to act. Stroke 2007;38:3063–9. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.496869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harvey G, Marshall RJ, Jordan Z et al. . Exploring the hidden barriers in knowledge translation: a case study within an academic community. Qual Health Res 2015;25:1506–17. 10.1177/1049732315580300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaglio B, Phillips SM, Heurtin-Roberts S et al. . How pragmatic is it? Lessons learned using PRECIS and RE-AIM for determining pragmatic characteristics of research. Implement Sci 2014;9:96 10.1186/s13012-014-0096-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moore G, Audrey S, Barker M et al. . Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. London: MRC Population Health Science Research Network, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pawson R, Tilley N. Realistic evaluation. Sage, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rycroft-Malone J, Fontenla M, Bick D et al. . A realistic evaluation: the case of protocol-based care. Implement Sci 2010;5:38 10.1186/1748-5908-5-38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rycroft-Malone J, Wilkinson JE, Burton CR et al. . Implementing health research through academic and clinical partnerships: a realistic evaluation of the Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC). Implement Sci 2011;6:74 10.1186/1748-5908-6-74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoffmann TC, Walker M. TIDieR-ing up’ the reporting of interventions in stroke research: the importance of knowing what is in the ‘black box’. World Stroke Organisation, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clarke DJ, Hawkins R, Sadler E et al. . Introducing structured caregiver training in stroke care: findings from the TRACS process evaluation study. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004473 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Healthc 2007;19:349–57. 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patton MQ. Qualitative research & evaluation methods. 3rd edn SAGE Publications, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang W, Creswell J. The use of “mixing” procedure of mixed methods in health services research. Med Care 2013;51:e51–7. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31824642fd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Cathain A, Goode J, Drabble SJ et al. . Getting added value from using qualitative research with randomized controlled trials: a qualitative interview study. Trials 2014;15:215 10.1186/1745-6215-15-215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lewin S, Glenton C, Oxman AD. Use of qualitative methods alongside randomised controlled trials of complex healthcare interventions: methodological study. BMJ 2009;339:b3496 10.1136/bmj.b3496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fearon P, Langhorne P, Early Supported Discharge T. Services for reducing duration of hospital care for acute stroke patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;(9):CD000443 10.1002/14651858.CD000443.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Langhorne P, Taylor G, Murray G et al. . Early supported discharge services for stroke patients: a meta-analysis of individual patients’ data. Lancet 2005;365:501–6. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17868-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.National Health Medical Research Council. Ethical considerations specific to qualitative methods. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/book/chapter-3-1-qualitative-methods

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-012027supp1.pdf (189KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-012027supp2.pdf (431.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-012027supp3.pdf (317.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-012027supp4.pdf (317.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-012027supp5.pdf (296KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-012027supp6.pdf (177.6KB, pdf)