Abstract

Alphaproteobacteria of the metabolically versatile Roseobacter group (Rhodobacteraceae) are abundant in marine ecosystems and represent dominant primary colonizers of submerged surfaces. Motility and attachment are the prerequisite for the characteristic ‘swim-or-stick' lifestyle of many representatives such as Phaeobacter inhibens DSM 17395. It has recently been shown that plasmid curing of its 65-kb RepA-I-type replicon with >20 genes for exopolysaccharide biosynthesis including a rhamnose operon results in nearly complete loss of motility and biofilm formation. The current study is based on the assumption that homologous biofilm plasmids are widely distributed. We analyzed 33 roseobacters that represent the phylogenetic diversity of this lineage and documented attachment as well as swimming motility for 60% of the strains. All strong biofilm formers were also motile, which is in agreement with the proposed mechanism of surface attachment. We established transposon mutants for the four genes of the rhamnose operon from P. inhibens and proved its crucial role in biofilm formation. In the Roseobacter group, two-thirds of the predicted biofilm plasmids represent the RepA-I type and their physiological role was experimentally validated via plasmid curing for four additional strains. Horizontal transfer of these replicons was documented by a comparison of the RepA-I phylogeny with the species tree. A gene content analysis of 35 RepA-I plasmids revealed a core set of genes, including the rhamnose operon and a specific ABC transporter for polysaccharide export. Taken together, our data show that RepA-I-type biofilm plasmids are essential for the sessile mode of life in the majority of cultivated roseobacters.

The alphaproteobacterial Roseobacter group is a global player in marine ecosystems with an important role for carbon and sulfur cycling (Wagner-Döbler and Biebl, 2006; Moran et al., 2007). Its abundance typically ranges between 3 and 5% of bacterial cells in the open ocean, accounts for up to 10% in marine sediments and can reach 36% in nutrient-rich costal habitats (Giebel et al., 2009; Lenk et al., 2012; Luo and Moran, 2014). Roseobacters are dominant primary colonizers of submerged surfaces (Dang and Lovell, 2002), suggesting that attachment is central to the ecology of this lineage (Slightom and Buchan, 2009). Many representatives live in close association with kelp, sea lettuce and microalgae (Miller et al., 2004; Thole et al., 2012; Wichard, 2015), and it has been shown that flagellar motility is important for the tight interaction of the bacterium with its eukaryotic host (Miller and Belas, 2006). The mutualistic relationship of Dinoroseobacter shibae and dinoflagellates, which bases on the biosynthesis of essential vitamins by the bacterium and the provision of organic nutrients by the microalga, is exemplified in the ‘hitchhiker's guide to life in the sea' (Wagner-Döbler et al., 2010). However, senescent algal blooms may turn the bacterial symbiont into an opportunistic pathogen (Wang et al., 2014) that synthesizes strong anti-algal tropone derivatives, so-called roseobacticides (Seyedsayamdost et al., 2011a, b). This ecological flexibility is characteristic for roseobacters and correlates with a reversible transition from an attached to a planktonic lifestyle (D'Alvise et al., 2014) triggered by intracellular signals or extracellular inducers (Zan et al., 2012; Sule and Belas, 2013). Genome sequencing of >70 strains revealed a puzzling spectrum of various metabolic capacities such as the aerobic anoxygenic photosynthesis, the reduction of nitrogen and the degradation of different aromatics, whose scattered distribution indicates that horizontal gene transfer is a particularly dominant evolutionary force in this marine bacterial lineage (Newton et al., 2010).

The extent of horizontal gene transfer in the Roseobacter group has not been systematically investigated, but the exceptional wealth of plasmids led to the prediction that conjugational transfer of extrachromosomal replicons (ECRs) is crucial for the rapid adaptation to novel niches and thus for their ecological success (Petersen et al., 2013). In accordance with their metabolic flexibility, roseobacters exhibit a versatile genome architecture, ranging from a single chromosome in Planktomarina temperata (Voget et al., 2015), over one large additional ECR in Ruegeria pomeroyi (Moran et al., 2004), up to a dozen coexisting ECRs in Marinovum algicola (Pradella et al., 2010). The prerequisite for the stable maintenance of different low-copy-number plasmids within the same bacterial cell are compatible replication systems that typically comprise a replicase and a conserved parAB partitioning module (Petersen, 2011). Rhodobacteraceae contain four different plasmid types designated RepA, RepB, RepABC and DnaA-like according to their non-homologous replicases. The crucial replicase gene is the sole reliable genetic marker for plasmid classification and the respective phylogenies allow in silico predictions about their compatibility. Accordingly, at least four compatibility groups of RepA-type plasmids could be identified in Rhodobacteraceae that were named RepA-I, -II, -III and -IV (Petersen et al., 2011). The relevance of plasmids in the Roseobacter group is exemplified by the indispensability of D. shibae replicons for anaerobic growth and survival under starvation (Ebert et al., 2013; Soora et al., 2015), the extrachromosomal localization of the complete photosynthesis gene cluster in Roseobacter litoralis and Sulfitobacter guttiformis (Pradella et al., 2004; Kalhoefer et al., 2011; Petersen et al., 2012) as well as the plasmid-encoded pathway for the synthesis of the antibiotic tropodithietic acid in several Ruegeria and Phaeobacter isolates (Geng et al., 2008; Thole et al., 2012).

Plasmid curing experiments in Phaeobacter inhibens DSM 17395 recently showed that two physiological capacities of paramount importance for the Roseobacter group, that is, biofilm formation and swimming motility, essentially depend on the presence of a 65-kb RepA-I-type replicon containing a rhamnose operon (Frank et al., 2015a). More than 20 genes for the production of exopolysaccharides, including a rhamnose operon, are located on this small RepA-I plasmid (Thole et al., 2012). The comparison of the curing mutant with the wild type showed that the biofilm plasmid is required for attachment on polystyrene as well as glass surfaces and that it is also essential for the colonization of micro- and macroalgae (Frank et al., 2015a). Similar results have been obtained for the homologous 52-kb RepA-I plasmid of the distantly related species M. algicola DG898 that also harbors the characteristic rhamnose operon (Frank et al., 2015b). The four genes of this operon are required for the synthesis of dTDP-l-rhamnose, which is a key component of surface polysaccharides (Giraud and Naismith, 2000), and single-gene knockouts caused loss of biofilm formation in rhizobia, beta- and gammaproteobacteria (Rahim et al., 2000; Broughton et al., 2006; Balsanelli et al., 2010). Interestingly, the biofilm plasmid curing mutants of P. inhibens DSM 17395 and M. algicola DG898 also lost the capacity for swimming motility (Frank et al. 2015b). Bruhn et al. (2007) showed the correlation between attachment ability and motility for different Roseobacter species and a quorum sensing-dependent regulation is documented for Ruegeria sp. KLH11 (Zan et al., 2012). The specific interdependence of both phenotypic traits was validated by a reciprocal experiment. Plasmid curing of the 143-kb DnaA-like I type replicon of M. algicola DG898, which contains a complete flagellar gene cluster (FGC) encoding most proteins for the formation of a functional flagellum, resulted in an immotile bacterium that also lost its ability for biofilm formation (Frank et al., 2015b). Phylogenomic analyses in this study revealed the presence of three different FGCs in the Roseobacter group that were designated fla1, fla2 and fla3 according to their abundance and evolutionary origin. The type-1 FGC, which is essential for swimming motility in P. inhibens DSM 17395, represents the most common and archetypal flagellum of roseobacters that moreover co-evolves with its bacterial host. Phylogenetic subtrees of the less abundant type-2 and type-3 FGCs are incongruent with the species tree, and their occasional localization on extrachromosomal elements—exemplified by fla2 on the 143-kb plasmid of M. algicola DG898 (see above)—is best explained by horizontal transfer via conjugation. In an analysis of the 27 genomes available at that time, Slightom and Buchan (2009) showed that key traits essential for surface colonization, that is, flagella, chemotaxis, fimbrial pili, type II and IV secretion systems, quorum sensing, non-ribosomal peptide synthases and polyketide synthases are often correlated; however, the specific role of flagella for surface colonization in roseobacters has yet to be elucidated.

The sessile life stage was suggested to be a common and ecologically important trait in the Roseobacter group (for example, Porsby et al., 2008; Slightom and Buchan, 2009; Geng and Belas, 2010; D'Alvise et al., 2014), but investigations were so far only based on genome comparisons or limited to selected isolates. The current study was based on the working hypothesis that RepA-I-type plasmids with a rhamnose operon are crucial determinants of the ‘swim-or-stick' lifestyle in Rhodobacteraceae. The study is based on 67 sequenced genomes that were selected to cover the complete phylogenetic range of the Roseobacter group (Newton et al., 2010), of which 33 strains were investigated experimentally. Because of the intimate relationship between biofilm formation and swimming motility, both traits were systematically analyzed. Comparative genome analyses of roseobacters showed that two-thirds of the rhamnose operons are located on putative biofilm plasmids and that 70% of them represent RepA-I-type replicons. The phylogenomic analysis, which is based on more than 220 000 amino-acid positions, served as a reference tree to retrace the evolution of RepA-I-type plasmids, and moreover it allowed the detection of horizontal transfers. The functional role of RepA-I biofilm plasmids was confirmed by curing experiments in four other Roseobacter species and was narrowed down to the four rhamnose genes by single-gene knockouts in P. inhibens DSM 17395. Finally, a core set of conserved genes was identified on these biofilm plasmids.

Materials and methods

Biofilm formation assay

We analyzed biofilm formation of 33 Roseobacter strains that are deposited at the German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures (DSMZ; Braunschweig, Germany) via a crystal violet (CV) assay according to the protocol of O'Toole and Kolter (1998). The cells were grown at 28 °C in Erlenmeyer flasks with bacto marine broth (MB; DSMZ medium 514) to the exponential phase under vigorous shaking. A measure of 100 μl of the culture was transferred to 96-well flat bottom polystyrene cell culture plates (Corning, New York, NY, USA; Costar 3370) and incubated for 24 h without shaking. Planktonic cells were removed, and all wells were washed twice with 200 μl of H2O. Further details of our standardized CV assay are described in Frank et al. (2015a). Three biological and eight technical replicates of each experiment were established.

Motility tests

We investigated the motility of the 33 Roseobacter strains on 0.3% (w/v) soft agar MB plates, which represents a simple method to determine flagellar swimming motility (Rashid and Kornberg, 2000). The plates were point-inoculated with 3 μl of a culture grown in MB medium and incubated for 3–6 days at 28 °C. For statistical analyses, the diameter of the swimming zone of the P. inhibens DSM 17395 wild type and the mutants was measured trifold, that is, vertically, with an angle of 45° and horizontally, in order to average growth differences.

Statistical analyses of attachment assay and motility data

Primary data achieved from the attachment assay were analyzed with the statistical analysis software R, version 3.0.2. (R Development Core Team, 2014), using helper methods from the multcomp (Hothorn et al., 2008) and the opm package (Vaas et al., 2013), and visualized with box plots. As the variance of the data in the biofilm assay increased together with the measured values of CV staining, the data were log-transformed before model building and k-means clustering (with the optimal number of clusters determined using the Calinski–Harabasz criterion). The resulting number of four clusters represented no, weak, intermediate and strong biofilm formation. The median OD600 ranged from 0.101 for MB medium as a negative control to 1.188 for Phaeobacter gallaeciensis. According to the optimal k-means partitioning, weak biofilm formation was defined for bacterial strains that displayed an OD600 above 0.187, which represents roughly two times the negative control. Intermediate biofilm formation ranges between OD600 0.396 and 0.721, whereas strong biofilm formers exhibit an OD600 of >0.721.

The statistical significance of the differences in biofilm formation and swimming motility was inferred using a log-linear model in conjunction with a Tukey-type (all-against-all) contrast as implemented in the multcomp package. The plots of these multiple comparisons visualize significances of differences using 95% confidence intervals. Accordingly, we also tested whether the capacity of biofilm formation and swimming motility differs significantly between the 65-kb plasmid curing mutant and the transposon mutants of the rhamnose operon.

Genetic techniques and plasmid curing

The RepA-I plasmid replication module of P. inhibens DSM 17395 was amplified with the primers P584 and P585 (P584: 5′-AGCATGTCGAACGCCTTGAGA-3′, P585: 5′-GCTGTTGACGGAATGGAATGA-3′), and cloned into the AleI site of a modified pBluescript II SK(+) vector, which contained an additional tetracycline (Tc) resistance gene. Control sequencing of the 4692-bp amplificate revealed the absence of any PCR errors. Cloning of the RepA-I module of D. shibae into a modified pBluescript II SK(+) vector with a gentamicin (Gm) cassette is described in Frank et al (2015a).

Preparation of electrocompetent cells from P. inhibens DSM 17395, P. inhibens DSM 24588 (2.10), P. gallaeciensis DSM 26640T (=CIP105210T=BS107T), Pseudophaeobacter arcticus DSM 23566T and Marinovum algicola DSM 10251T (FF3) as well as plasmid curing with the RepA-I constructs was conducted as previously described (Petersen et al., 2011, 2013; Frank et al., 2015a). The Gm-vector was used for plasmid curing of all strains except P. arcticus, whose RepA-I plasmid was cured with the Tc-vector.

Transposon mutagenesis and arbitrary PCR

Transposon mutagenesis in P. inhibens DSM 17395 was performed with the EZ-Tn5 <R6Kγori/KAN-2>Tnp Transposome kit of Epicentre (Madison, WI, USA). Cultivation of individual transposon mutants was performed in MB medium with 120 μg ml−1 kanamycin. Total DNA was isolated with the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit of Qiagen (Hilden, Germany) and the insertion sites of 4000 transposon mutants were determined via arbitrary PCR as previously described (O'Toole and Kolter, 1998).

Phylogenetic analyses

The amino-acid alignments of the plasmid replicase RepA-I and four concatenated proteins of the bacterial flagellum (FliF, FlgI, FlgH and FlhA) obtained with ClustalW (Thompson et al., 1997) were manually refined using the ED option of the MUST program package (Philippe, 1993). Gblocks was used to eliminate both highly variable and/or ambiguous portions of the alignments (Talavera and Castresana, 2007). We used the neighbor-joining algorithm with gamma-corrected distance (Petersen et al., 2011) and performed 1000 bootstrap replicates using the NJBOOT-option of MUST (Philippe, 1993).

Phylogenomic analyses

The genome sequences of 67 organisms of the Roseobacter group (Supplementary Table 2) were phylogenetically investigated using the DSMZ phylogenomics pipeline as previously described (Spring et al., 2010; Abt et al., 2012) using NCBI BLAST (Altschul et al., 1997), OrthoMCL (Li et al., 2003), MUSCLE (Edgar, 2004), RASCAL (Thompson et al., 2003) and GBLOCKS (Talavera and Castresana, 2007). Briefly, clusters of orthologs were generated using OrthoMCL, inparalogs were removed, the remaining sequences were aligned with MUSCLE and filtered with RASCAL and GBLOCKS, and those alignments containing all 67 taxa (one sequence per genome) were concatenated to form the core-genes matrix. Maximum likelihood and maximum-parsimony trees were inferred from the core-genes matrix with RAxML (Stamatakis, 2006) and PAUP* (Swofford, 2002), respectively, as previously described (Spring et al., 2010; Abt et al., 2012). The core-genes matrix contained 643 genes and 223 802 characters. The LG model of amino-acid evolution was selected (Le and Gascuel, 2008) in conjunction with the CAT approximation of rate heterogeneity (Stamatakis, 2006) and empirical amino-acid frequencies. The resulting tree had a log likelihood of −7 723 275.58. The best maximum-parsimony tree found had a length of 1 407 318 steps (not counting uninformative characters).

Results and Discussion

Biofilm formation in completely sequenced roseobacters

In the current study, we analyzed the attachment of 33 completely sequenced Roseobacter strains with a standardized CV assay (Supplementary Figure 1), which reliably monitors the capacity of biofilm formation (Frank et al., 2015a). More than half of the tested strains formed biofilms (19/33) and 30% including P. inhibens DSM 17395, P. gallaeciensis, Silicibacter sp. TM1040 and Loktanella hongkongensis produced strong biofilms. All six strains that contain the superoperon for aerobic anoxygenic photosynthesis (Roseobacter litoralis, R. denitrificans, Salipiger mucosus, Roseibacterium elongatum, Loktanella vestfoldensis R-9477 and Dinoroseobacter shibae; Wagner-Döbler and Biebl, 2006) are incapable of biofilm formation under the conditions used in our assay, and this observation is in agreement with a photoheterotrophic planktonic lifestyle. The sampling site and provenience of bacterial strains have been expected to correlate with their attachment capacities as exemplified by the stickiness of L. hongkongensis and P. inhibens 2.10 that were isolated from a 7-day-old marine biofilm and the surface of the green alga Ulva lactuca, respectively (Lau et al., 2004; Thole et al., 2012; Table 1). However, it has previously been shown that R. litoralis Och 149, which was isolated from seaweed (Shiba, 1991), does not form biofilms under the tested conditions (Bruhn et al., 2007; Supplementary Figure 1). It is well known that phenotypic traits get occasionally lost in laboratory cultures via the accumulation of mutations, but the closely related species R. denitrificans Och 114 is also incapable of biofilm formation (Supplementary Figure 1). Moreover, the current study documents that Loktanella vestfoldensis R-9477 and Leisingera caerulea are lacking the ability of biofilm formation even though these strains were obtained from a microbial mat and a biofilm on a stainless steel electrode, respectively (Table 1). The isolation place of a Roseobacter strain hence does not allow for a reliable prediction of its capability for biofilm formation as assayed in the current study. This trait must be investigated individually, even if the bacterium was isolated from a biofilm. Nevertheless, the capacity of biofilm formation in the Roseobacter group might be largely underestimated by standardized CV assays. In natural habitats, biofilms represent complex assemblies of various bacteria, and microbe–microbe interactions are supposed to affect the ability of their formation and dispersal (McDougald et al., 2011).

Table 1. Attachment ability and motility of completely sequenced bacteria of the Roseobacter group analyzed in this study.

| Bacterial strain | Collection ID | Isolated from: |

Attachment |

Motility |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isoa | BFb | OD600b | Motb | Lit | Fla | ||||

| 01 | Phaeobacter inhibens | DSM 17395 | Unknown (Galicia, Spain) | U | +++ | 0.941 | + | +c | 1 |

| 02 | Phaeobacter inhibens T5 | DSM 16374T | Water sample | F | +++ | 1.019 | + | + | 1 |

| 03 | Phaeobacter inhibens 2.10 | DSM 24588 | Surface of Ulva lactuca (green alga) | A | +++ | 0.810 | + | ND | 1 |

| 04 | Phaeobacter gallaeciensis BS107 | DSM 26640T | Larval cultures of Pecten maximus (scallop) | F | +++ | 1.188 | + | + | 1 |

| 05 | Leisingera daeponensis TF-218 | DSM 23529T | Tidal flat sediment | F | + | 0.239 | + | ND | 1 |

| 06 | Leisingera caerulea 13 | DSM 24564T | Marine biofilm on stainless steel electrode | A | − | 0.139 | + | + | 1 and 2 |

| 07 | Leisingera aquimarina R-26159 | DSM 24565T | Marine biofilm on stainless steel electrode | A | ++ | 0.460 | + | + | 1 |

| 08 | Leisingera methylohalidivorans MB2 | DSM 14336T | Seawater collected from a tide pool | F | − | 0.108 | + | ND | 1 |

| 09 | Pseudophaeobacter arcticus 20188 | DSM 23566T | Marine sediment | F | ++ | 0.678 | + | ND | 1 |

| 10 | Silicibacter sp. TM1040 | — | Pfiesteria piscicida (dinoflagellate) | A | +++ | 1.007 | + | +d | 1 |

| 11 | Ruegeria pomeroyi DSS-3 | DSM 15171T | Seawater | F | − | 0.104 | − | + | 1 |

| 12 | Dongicola xiamenensis Y-2 | DSM 18339T | Surface seawater | F | − | 0.117 | + | − | 2 |

| 13 | Sedimentitalea nanhaiensis NH52F | DSM 24252T | Sediment | F | − | 0.143 | + | ND | 1 |

| 14 | Roseobacter litoralis Och 149 | DSM 6996T | Seaweed | A | − | 0.152 | − | + | 1 |

| 15 | Roseobacter denitrificans Och 114 | DSM 7001T | Seawater | F | − | 0.128 | − | + | 1 |

| 16 | Oceanibulbus indolifex HEL-45 | DSM 14862T | Seawater | F | − | 0.112 | + | − | 2 |

| 17 | Sulfitobacter sp. EE-36 | DSM 11700 | Salt marsh | F | +++ | 0.814 | + | ND | 2 |

| 18 | Roseovarius mucosus DFL 24 | DSM 17069T | Alexandrium ostenfeldii (dinoflagellate) | A | − | 0.127 | − | − | 1 and 3 |

| 19 | Roseovarius nubinhibens ISM | DSM 15170T | Seawater | F | − | 0.125 | − | + | − |

| 20 | Sediminimonas qiaohouensis YIM B024 | DSM 21189T | Ancient salt sediment from of a salt mine | F | + | 0.377 | − | − | − |

| 21 | Oceanicola batsensis | DSM 15984T | Seawater | F | +++ | 1.016 | + | − | 2 |

| 22 | Sagittula stellata EE-37 | DSM 11524T | Seawater | F | ++ | 0.523 | − | ND | 1 |

| 23 | Pelagibaca bermudensis HTCC2601 | DSM 26914T | Seawater | F | +++ | 0.962 | + | − | 1 and 2 |

| 24 | Salipiger mucosus A3 | DSM 16094T | Saline soil bordering a saltern | F | − | 0.127 | − | − | 1 and 2 |

| 25 | Marinovum algicola FF3 | DSM 10251T | Prorocentrum lima (dinoflagellate) | A | +++ | 0.908 | + | + | 1 and 2 |

| 26 | Marinovum algicola DG898 | DSM 27768 | Gymnodinium catenatum (dinoflagellate) | A | +++ | 0.733 | + | +e | 1 and 2 |

| 27 | Loktanella hongkongensis | DSM 17492T | 7-day-old marine biofilm | A | +++ | 1.093 | + | − | 2 |

| 28 | Wenxinia marina HY34 | DSM 24838T | Marine sediment | F | ++ | 0.640 | − | − | − |

| 29 | Oceanicola granulosus | DSM 15982T | Seawater | F | ++ | 0.469 | + | − | 1 and 2 |

| 30 | Loktanella vestfoldensis R-9477 | DSM 16212T | Microbial mat | A | − | 0.132 | − | − | − |

| 31 | Roseibacterium elongatum Och 323 | DSM 19469T | Sand at Monkey Mia | F | − | 0.124 | − | − | 1 |

| 32 | Dinoroseobacter shibae DFL 12 | DSM 16493T | Prorocentrum lima (dinoflagellate) | A | − | 0.118 | − | + | 1 |

| 33 | Litoreibacter arenae GA2-M15 | DSM 19593T | Sea sand | F | + | 0.329 | − | + | 1 |

| 34 | Phaeobacter inhibens Δ65 kb | DSM 17395 | Unknown (Galicia, Spain) | U | − | 0.139 | − | 1 | |

| 35 | Phaeobacter inhibens 2.10 Δ70 kb | DSM 24588 | Surface of Ulva lactuca (green alga) | A | − | 0.124 | − | 1 | |

| 36 | Phaeobacter gallaeciensis BS107 Δ69 kb | DSM 26640T | Larval cultures of Pecten maximus (scallop) | F | − | 0.113 | − | 1 | |

| 37 | Pseudophaeobacter arcticus 20188 Δ92 kb | DSM 23566T | Marine sediment | F | + | 0.191 | − | 1 | |

| 38 | Marinovum algicola FF3 Δ50 kb | DSM 10251T | Prorocentrum lima (dinoflagellate) | A | − | 0.102 | − | 1 and 2 | |

| 39 | Marinovum algicola DG898 Δ52 kb | DSM 27768 | Gymnodinium catenatum (dinoflagellate) | A | − | 0.118 | − | 1 and 2 | |

Abbreviations: A, attachment (isolate is associated with microalgae, surface or material mats); BF, biofilm formation; F, free living (isolate from seawater, sand or sediments); Fla, flagella gene cluster (fla1, fla2, fla3); Iso, isolate; Lit, literature (type strain description); Mot, motility; ND, not determined; OD600, experimental median (Figure 1); U, unknown.

References.

Current study.

Motility in completely sequenced roseobacters

We studied swimming motility of all 33 strains to validate our prediction that motility is generally required for biofilm formation in roseobacters. The genes for the formation of a flagellum are present in all but four of the completely sequenced Roseobacter strains investigated in the current study (Table 1). Motility was previously reported for 14 of these strains, but it could not be observed in 12 others. The observed immotility of Roseovarius nubinhibens ISM is contradictory to the species description (Supplementary Figure 2; González et al., 2003), but in agreement with the absence of flagellar genes in its draft genome (Table 1). The individual capacity of roseobacters differs largely as exemplified by the brownish representative P. inhibens DSM 16374T (T5), which swims fast and covers the complete Petri dish after 3 days of incubation, and the pink strain D. shibae DSM 16493T (DFL 12) that is immotile under the given test conditions (Supplementary Figure 2). Motility was experimentally shown for 20 of the 33 tested strains, and all but one Roseobacter showed the expected swimming zone. Only Dongicola xiamenensis exhibits a locally restricted movement on the agar plate resulting in a characteristic dendritic morphology that is typical for swarming motility (Supplementary Figure 2), even if sliding or twitching can not be excluded. Swarming, which is supposed to be advantageous for the effective colonization of surface niches (Partridge and Harshey, 2013), has not been reported for roseobacters so far. The characteristic swimming behavior of D. xiamensis hence exemplifies the physiological versatility of this group of marine alphaproteobacteria.

Our experimental setup allowed us to compare the swimming motility of 33 different Roseobacter strains, but it is not suitable to exclude motility per se. The 12 observed differences between the current study and the literature (Table 1) may hence simply result from a different methodology to determine motility. Nevertheless, in the current study, we could—in agreement with our prediction—largely validate the former observations that those roseobacters, which are capable to form biofilms are also motile (Bruhn et al., 2007; Frank et al., 2015a, b), whereas evidence for swimming motility does in turn not allow conclusions about biofilm formation. The four immotile exceptions Sediminimonas qiaohouensis, Sagittula stellata, Wenxinia marina and Litoreibacter arenae form only weak (+) or intermediate (++) biofilms (Table 1), thus indicating that their mode of surface attachment may be different from the typical biphasic ‘swim-or-stick' lifestyle reported for roseobacters (Belas et al., 2009; D'Alvise et al., 2014).

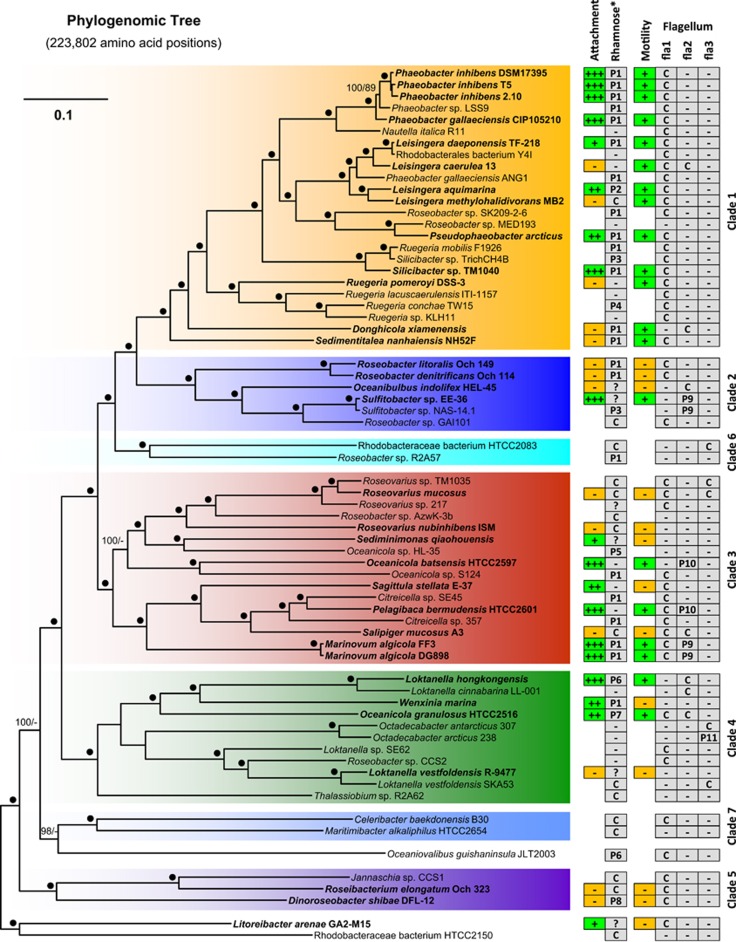

Organismal reference tree

A comprehensive phylogenomic analysis of 67 roseobacters that served as an organismal reference tree is presented in Figure 1. It contains, highlighted in boldface, all 33 strains that were physiologically characterized in the current study, and thus allowed to determine their evolutionary relationship and their representativeness. Most genomes represent type strains that cover the entire phylogenetic depth of this marine lineage, which was already cultivated. The tree is based on an amino acid supermatrix with 223 802 positions from the 643 genes of the core genome. Our analysis resolves the relationships of many closely related genera with maximal statistical support and the topology is largely in agreement with the maximum-likelihood tree based on 32 Roseobacter genomes and 70 universal single-copy genes of Newton et al. (2010). The sole exception is the position of ‘Rhodobacteraceae bacterium HTCC2083' that was in the previous study the most basal representative of clade 2 (moderate bootstrap support) and now constitutes together with Roseobacter sp. R2A57 the novel clade 6 branching as the sister group of clade 1 and 2. The larger set of genomes and the ninefold higher number of analyzed genes correlates obviously with a better resolution, revealed by an increased statistical support. The 33 strains that were used for biofilm and motility assays represent roughly half of the sequenced genomes of the Roseobacter group and reflect the phylogenetic diversity of this lineage (Figure 1). The underlying reason is the targeted selection of DSMZ strains for genome sequencing in the ‘Genomic Encyclopedia of Bacteria and Archaea' project that was initiated to fill the deepest gaps in the prokaryotic phylogeny based on 16S ribosomal DNA analyses (Wu et al., 2009).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree of the maximum-likelihood (ML) analysis of 67 sequenced Roseobacter genomes based on 223 802 amino-acid positions representing 643 genes of the core genome. The color code and numbering of the different clades refer to the phylogenetic tree of Newton et al. (2010). Strains that were used for attachment and motility assays are shown in bold. The branch lengths are proportional to the inferred number of substitutions per site. Statistical support for internal nodes of the ML tree was determined with rapid bootstrapping and the bootstopping criterion. For maximum parsimony (MP), 1000 replicates with 10 rounds of heuristic search per replicate were computed. Support values >60% are shown (ML, left; MP, right). ‘●', 100% bootstrap support ML and MP; ‘+++, ++, +', attachment and motility according to Table 1; ‘−', lacking ability of biofilm formation, motility (Table 1) or the absence of the rhamnose operon/flagellar gene cluster in the genome; ‘C', chromosomal localization; ‘P1–P11', plasmid localization (P1=RepA-I-type plasmid; P2=RepB-I, P3=RepABC-8, P4=DnaA-like II, P5=RepA-IV, P6=RepA*, P7=RepABC-3, P8=RepABC-1, P9=DnaA-like I, P10=RepABC-3, P11=RepB-III; Petersen et al., 2009; Petersen et al., 2011; Supplementary Table 1]); ‘?' localization unknown.

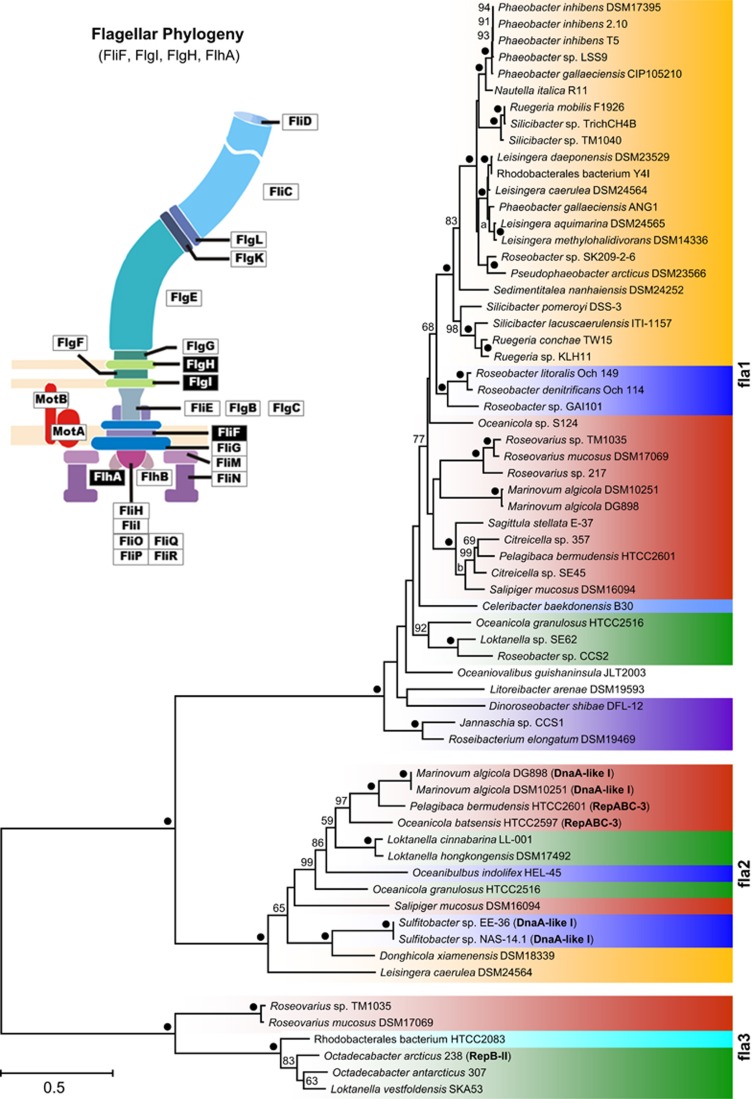

Distribution of flagellar systems in roseobacters

We investigated the distribution of the three different FGCs from all 67 Roseobacter genomes and correlated their presence with the capacity of swimming motility. The flagellar phylogeny in Figure 2 shows three maximal supported subtrees that represent the recently described flagellum superoperons fla1, fla2 and fla3 of Rhodobacteraceae (Frank et al., 2015b). Fla1 encodes the most abundant flagellum type 1 and its branching pattern largely reflects the organismic evolution of roseobacters especially in clade 1 (Figures 1 and 2). The two other flagellar systems occur sporadically and their localization on DnaA-like I, RepABC-3- and RepB-II-type plasmids is indicative of horizontal transfer (Frank et al., 2015b). The presence of a solitary type-1 or type-2 FGC is sufficient for swimming motility as exemplified by P. inhibens DSM 17395 and Loktanella hongkongensis, respectively (Figures 1 and 2; Supplementary Figure 2). Motility of strains with a sole fla3 superoperon was not tested in the current study and the two Octadecabacter type strains were described as nonmotile (Gosink et al., 1997). However, a type-3 FGC encodes the well-characterized single subpolar flagellum of Rhodobacter sphaeroides that is required for swimming (Poggio et al., 2007 (fla3 flagellum; described as ‘fla1'); Frank et al. 2015b). These findings document that Rhodobacteraceae can use in principle each of the three flagellar systems for swimming motility, but our experiments also showed that even bacteria with two FGCs such as Salipiger mucosus (fla1 and fla2) or Roseovarius mucosus (fla1 and fla3) are immotile under the conditions that were used in this study (Supplementary Figure 1; Martínez-Cánovas et al., 2004; Biebl et al., 2005). Nevertheless, it is unlikely that their conserved flagellar systems are not functional. Former studies on Alphaproteobacteria with two FGCs showed that R. sphaeroides WS8N requires a compensatory mutation to expresses its second type-1 flagellum under the tested conditions (Poggio et al., 2007 ('fla2'); Vega-Baray et al., 2015), whereas Rhodospirillum centenum (synonym Rhodocista centenaria; Rhodospirillaceae) contains a single constitutively expressed polar flagellum as well as numerous lateral flagella that are only found when cells are grown in highly viscous medium (McClain et al., 2002). Accordingly, and in agreement with our in silico analyses, we conclude that the capacity of (roseo-) bacterial motility in the natural environment is largely underestimated under standardized test conditions in the laboratory.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic maximum-likelihood tree based on the four concatenated flagellar proteins (FliF, FlgI, FlgH and FlhA; see schematic flagellum) from 64 Rhodobacteraceae using 1375 amino-acid positions. Three distinct subtrees correspond to the recently described flagella superoperons fla1, fla2 and fla3 (Frank et al., 2015b). Plasmid replication type of extrachromosomal flagellar gene clusters are highlighted in bold (DnaA-like-I, RepABC-3 and RepB-II). The color code corresponds to those of the phylogenomic tree (Figure 1). ‘●', 100% bootstrap support.

General relevance of biofilm plasmids in Rhodobacteraceae

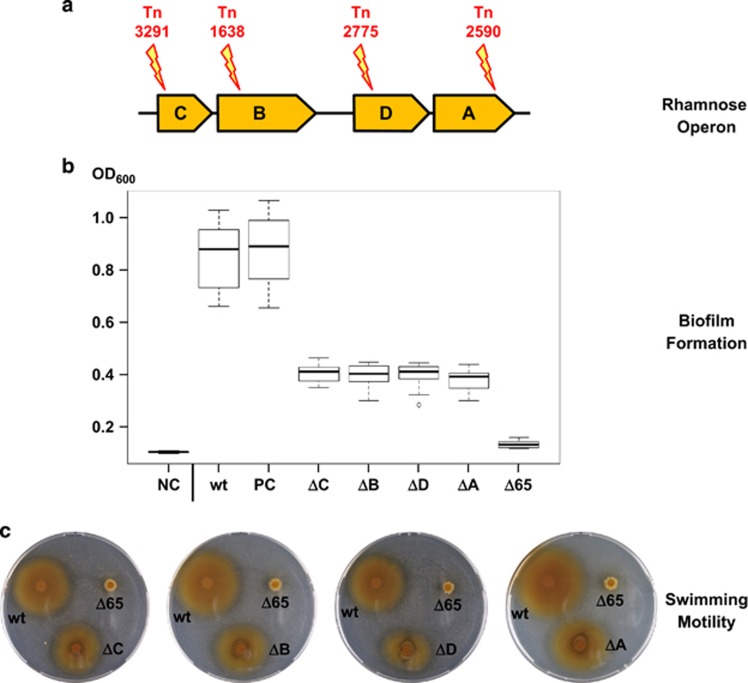

Functional role of the rhamnose operon in P. inhibens DSM 17395

We have recently shown that the 65-kb RepA-I-type replicon of P. inhibens DSM 17395 is indispensable for biofilm formation and also required for swimming motility and it is therefore referred to as biofilm plasmid (Frank et al., 2015a). RepA-I plasmids are widespread among the Roseobacter group (Figure 1) and it has previously been proposed that the characteristic rhamnose operon is crucial for biofilm formation (Frank et al., 2015a, b). To test this hypothesis, we seached in our transposon library of P. inhibens DSM 17395 for insertional knockout mutants of the rhamnose operon and could identify one mutant for each of the four genes (rmlA: Tn_2590, rmlB: Tn_1638, rmlC: Tn_3291 and rmlD: Tn_2775; Figure 3a; Supplementary Material 1a). The standardized CV assay revealed a significant loss of surface attachment for all four transposon mutants (Figure 3b; Supplementary Material 1b), thus substantiating the prediction that l-rhamnose is of central importance for biofilm formation of P. inhibens DSM 17395. Comparable results have been reported for other alpha-, beta- and gammaproteobacteria (Rahim et al., 2000; Broughton et al., 2006; Balsanelli et al., 2010), which reflects the pivotal role of this sugar component for stable adhesion to surfaces. However, the individual knockouts of rhamnose genes in P. inhibens DSM 17395 diminished the attachment capacity by only an average of 78%, whereas the Δ65-kb curing mutant showed a reduction of 96% (Figure 3b; Frank et al., 2015a). We tested the insertion sites of our transposon mutants (Supplementary Material 1a) and can hence exclude that additional non-tagged plasmids (heterogeneous population) or residual wild-type cells account for the residual surface attachment. l-Rhamnose is supposed to mediate cellular cross-linking in P. inhibens DSM 17395, but our results clearly indicate that additional genes of the 65-kb plasmid or genes that are controlled by this ECR are required for the formation of a functional biofilm. This prediction is supported by the observation that all four rhamnose knockouts are still motile, in contrast to the curing mutant of the 65-kb biofilm plasmid (Figure 3c). However, their motility is slightly but significantly reduced (Supplementary Material 1c), which might reflect the missing incorporation of l-rhamnose into the flagellin glycan as previously proposed for Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA01 (Lindhout et al., 2009). The remaining 4% attachment of the Δ65-kb curing mutant probably reflects the basal adhesion capacity that is required for the ‘swim-to-stick' transition. The importance of the initial surface contact might have even been underestimated due to the lack of swimming motility of the Δ65-kb mutant, but its molecular basis has yet to be determined.

Figure 3.

(a) Localization of transposon (Tn) mutants in the four genes of the rhamnose operon located on the 65-kb plasmid of Phaeobacter inhibens DSM 17395 (rmlC, rmlB, rmlD and rmlA). (b) Box plot of biofilm formation of the rhamnose transposon mutants monitored by crystal violet assays of three biological and eight technical replicates. The P. inhibens wild type (wt) and the transposon mutant Tn_4121 (inserted in the non-coding region between PGA1_c16400 and PGA1_c16410; position 1 701 875; plus strand) served as a positive control (PC). Mean OD600 of MB medium (negative control (NC); 0.100), wt (0.877), PC (Tn_4121; 0.888), ΔrmlC (0.409), Δ rmlB (0.402), Δ rmlD (0.410), Δ rmlA (0.391) and Δ65 kb (0.128). (c) Motility assay on 0.3% agar for the detection of swimming motility. Plates were incubated for 3 days at 28 °C. ΔC, ΔB, ΔD and ΔA, Tn-mutants of the rhamnose operon; Δ65, P. inhibens DSM 17395 curing mutant lacking the 65-kb plasmid.

Rhamnose operons, attachment and biofilm plasmids

We compared the physiological results of our attachment experiments with the presence of rhamnose operons and used the phylogenomic tree as an evolutionary backbone (Figure 1). The comparative survey shows that attachment of roseobacters, as measured by the standardized CV assay, does not strictly correlate with the phylogenetic affiliation of the tested stains. Clade 1 contains strong biofilm formers such as P. inhibens and P. gallaeciensis, but the capacity for biofilm formation is lacking in five representatives. The planktonic lifestyle of L. caerulea and Ruegeria pomeroyi (no attachment; Supplementary Figure 2) correlates with the absence of a rhamnose operon (Figure 1), and it is also in agreement with the curing experiment and transposon mutagenesis in P. inhibens DSM 17395 (Frank et al., 2015a; Figure 3). However, the presence of a rhamnose operon is in turn not sufficient for attachment as shown, for example, for Sedimentitalea nanhaiensis and Roseobacter litoralis. l-Rhamnose, which is required for lipopolysaccharide and O-antigen formation (Broughton et al., 2006), is just one ‘biobrick' for the formation of biofilms, and the complex mechanism as a whole is only poorly understood. An unexpected observation is the absence of rhamnose operons in the draft genomes of Oceanicola batsensis, Sagittula stellata and Pelagibaca bermudensis despite their proven ability to form biofilms. These three representatives, which are all located in clade 3 of our phylogenomic tree, may have developed a rhamnose-independent mechanism for surface attachment.

Irrespective of the exceptions reported above, our experiments clearly showed that curing of whole RepA-I-type biofilm plasmids with rhamnose operons resulted in a nearly complete loss of biofilm formation (Frank et al., 2015a, b; see also below). It is conspicuous that the rhamnose operon is located on extrachromosomal elements in more than two-thirds of the completely sequenced Roseobacter strains (31/46; Figure 1). Even more surprising is the observation that rhamnose operons are present on at least 10 different plasmid types all representing independent compatibility groups (Figure 1; Petersen, 2011). With 22 plasmids, RepA-I replicons represent the by far most abundant type, but we also detected three RepABC-type plasmids belonging to compatibility groups 1, 3 and 8, two additional RepA-type plasmids (RepA-IV and RepA*) as well as RepB-I and DnaA-like-II replicons. The 118-kb RepB-III plasmid of Sulfitobacter guttiformis (Petersen et al., 2012) and the RepABC-2 replicon of Ruegeria mobilis 45A6 (IMG-scaffold: ruegeria_c36) represent the ninth and tenth plasmid type with a rhamnose operon (Supplementary Table 1). Such a patchy distribution of a functional unit on different plasmids and the chromosome is in agreement with the important role of extrachromosomal elements in the Roseobacter group. It is indicative of massive intracellular recombination events between different replicons (Supplementary Material 2) and moreover proposes plasmid-borne horizontal transfer of the rhamnose operon.

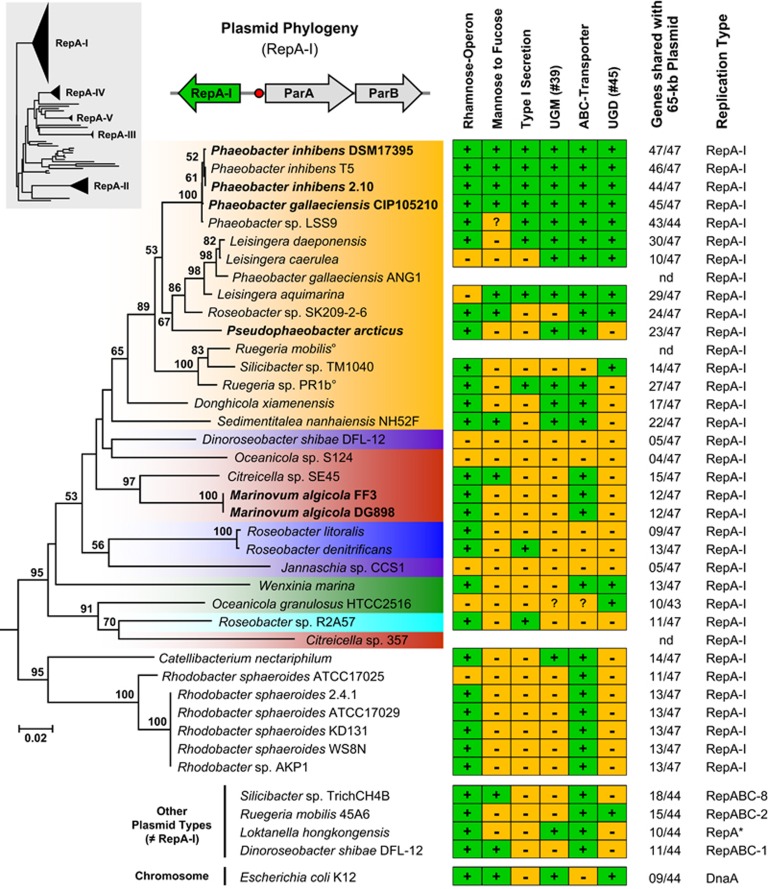

Distribution and evolution of RepA-I plasmids in Rhodobacteraceae

The frequent occurrence of RepA-I plasmids with rhamnose operons offered the opportunity to investigate the distribution of this replicon type in the context of organismic evolution. Our comprehensive phylogenetic analysis documented that RepA-type plasmids are present in different bacterial lineages including Sphingomonadales, Nitrosomonadales and planctomycetes, but it also showed that the RepA-I subtree represents the dominant compatibility group in Rhodobacteraceae (Supplementary Figure 3; Petersen, 2011). The comparison of the RepA-I phylogeny with the species tree (Figures 1 and 4; same color code) revealed that RepA-I plasmids are present in 28 of 67 completely sequenced roseobacters, but they are only sporadically found in six of the seven phylogenomic subgroups (clades 2–7). The distribution of many RepA-I sequences is incompatible with the organismic evolution as documented by the two Citreicella strains (compare Figures 1 and 4; clade 3, red color). In the species tree, both strains group together with Pelagibaca bermudensis (clade 3; 100% bootstrap proportion (BP)), but in the RepA-I analysis Citreicella sp. SE45 groups solidly with Marinovum algicola (clade 3; 97% BP), whereas Citreicella sp. 357 is part of a well-supported subtree together with Roseobacter sp. R2A57 (clade 6; 70% BP) and Oceanicola granulosus (clade 4; 91% BP), thus providing a clear-cut example of horizontal gene transfer.

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic neighbor-joining tree based on gamma-corrected distances of RepA-I-type plasmid replication initiator proteins from 35 Rhodobacteraceae sequences using 300 amino-acid positions. The color code corresponds to those of the phylogenomic tree (Figure 1). Strains of the current study whose RepA-I biofilm plasmid was cured are shown in bold. The topology of a comprehensive reference phylogeny containing all RepA-type proteins from the Roseobacter group is shown in the gray box (Supplementary Figure 3). The three genes represent a typical RepA-I-type plasmid replication module containing the replicase (repA-I), the parAB partitioning operon and the origin of replication (red circle). The matrix shows the presence and absence of central genes involved in polysaccharide metabolism using the biofilm plasmid of Phaeobacter inhibens DSM 17395 as a reference (Supplementary Table 1). UGM, UDP-galactopyranose mutase (EC 5.4.99.9); UGD, UDP-glucose 6-dehydrogenase (EC 1.1.1.22); °, genome not sequenced; *, compatibility group not determined.

A striking contrast is provided by the dominant orange colored subtree of RepA-I sequences belonging to clade 1 (Figure 4), because its topology is largely congruent with those of the species tree (Figure 1). The sporadic absence of rhamnose operons, for example, in Nautella italica R11, ‘Rhodobacterales bacterium Y41' and Roseobacter sp. MED193 correlates with the absence of RepA-I plasmids and may be the consequence of natural plasmid loss. It is likely that at least the common ancestor of the well-supported uppermost subtree, which ranges from P. inhibens DSM 17395 to Silicibacter sp. TM1040 (100% BP, Figure 1), already contained a RepA-I plasmid. Moreover, a comprehensive comparison of RepA-I replicons that is based on TBLASTN analyses with all 47 annotated proteins of the P. inhibens DSM 17395 biofilm plasmid revealed a considerable degree of positional conservation (Supplementary Table 1; see also below). Those replicons that also contain the rhamnose operon share between 11 and 46 orthologous genes with the reference plasmid (Figure 4), which probably reflects the vertical evolution of functional biofilm plasmids within the genera Phaeobacter, Pseudophaeobacter, Leisingera and Silicibacter/Ruegeria.

Curing of RepA-I-type biofilm plasmids

Plasmid curing in P. inhibens DSM 17395 and M. algicola DG898 exemplified the essential role of RepA-I-type plasmids for biofilm formation and motility (Frank et al., 2015a, b). The widely spread distribution of orthologous replicons with a rhamnose operon indicates that biofilm plasmids are abundant among Rhodobacteraceae irrespective of occasional genetic rearrangements and loss of attachment (Figure 1; Supplementary Table 1). To test this prediction, we performed curing experiments with four additional strains from the Roseobacter group whose ability of biofilm formation was experimentally proven (Supplementary Figure 1). We successfully cured the RepA-I plasmids from a second P. inhibens strain (DSM 24588 [2.10]), its sister species P. gallaeciensis (DSM 26640T=CIP105210T [BS107T]), P. arcticus DSM 23566T and the M. algicola type strain (DSM 10251T [FF3T]). The standardized attachment assay showed a largely diminished capacity to stick to surfaces for the four newly established curing mutants, which is comparable to those of the references P. inhibens DSM 17395 and M. algicola DG898 (Supplementary Figure 4). Moreover, all curing mutants lost their ability for swimming motility. The current survey provides independent evidence for the intrinsic correlation between biofilm formation and motility, and it validates the conclusions of two former studies (Frank et al., 2015a, b). Finally, the experimental data of in total six RepA-I-type replicons with rhamnose operons strongly support our in silico predictions about the great importance of biofilm plasmids for Rhodobacteraceae.

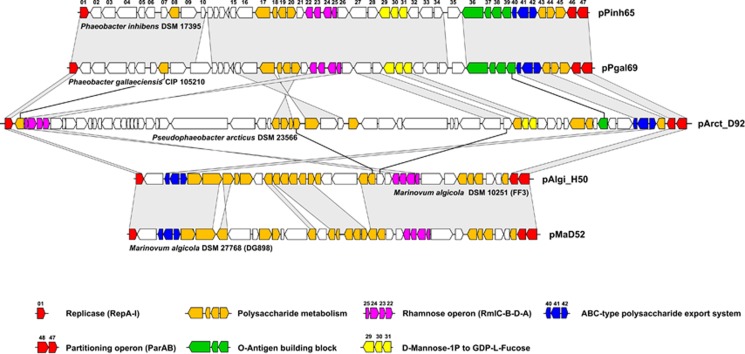

Composition of biofilm plasmids

We compared the 47 genes of the archetypical biofilm plasmid of P. inhibens DSM 17395 (#01–#47) with all available RepA-I-type replicons via TBLASTN searches to identify common traits that are, in addition to the presence of the rhamnose operon, shared by these extrachromosomal elements. Functional clustering could be documented for several other genes that might be crucial for biofilm formation (Supplementary Table 1) and a summary of this distribution is shown in the presence and absence matrix of Figure 4. The function of three clusters/genes that are conspicuously shared with the 40-kb rfb gene cluster of E. coli K12 is described in the Supplementary Material 3. The comprehensive comparison of >30 RepA-I-type replicons allowed us to identify an exopolysaccharide export system (ABC transporter; #40, #41 and #42) that is found on all six experimentally tested biofilm plasmids (Figures 4 and 5; Supplementary Table 1). Its prevalence among roseobacters suggests a central role for biofilm formation, a prediction that is in agreement with the well-known function of highly conserved ABC transporters for the export of cell surface glycoconjugates (Cuthbertson et al., 2010). Altogether, seven different groups of glyco-ABC transporters have been identified based on phylogenetic analyses of their ATPase (Cuthbertson et al., 2010), and the respective gene of P. inhibens DSM 17395 (#40) belongs to the distinct group F lacking the typical C-terminal extension. The orthologous ABC transporter from E. coli K1 has initially been identified based on the observation that mutants accumulated capsular polysaccharides within the cytoplasm (Pavelka et al., 1991, 1994).

Figure 5.

Comparison of different biofilm plasmids from the Roseobacter group. Homology between the replicons is indicated by vertical gray-shaded areas and black lines. Consecutive numbering of genes based on the reference plasmid pPinh65 (Supplementary Table 1). The color code of the genes is explained in the legend.

Taken together, curing of the 65-kb RepA-I-type plasmid of P. inhibens DSM 17395 resulted in the loss of two dozen genes for polysaccharide biosynthesis, transfer and export (Supplementary Table 1), and accordingly the capacity to form biofilms (Supplementary Figure 4). Functional analyses of several orthologs from rhizobia and E. coli (see above) documented their crucial role for attachment thus reflecting the complexity of this process. The comparison of different biofilm plasmids revealed that many genes involved in polysaccharide formation are widely distributed (Figures 4 and 5; Supplementary Table 1). The universal presence of the rhamnose operon and of the ABC exporter of capsular polysaccharides indicates their central function for the formation of a functional biofilm. Our comparative analyses also showed that the biofilm plasmids accumulated an individual set of genes involved in polysaccharide metabolism that probably reflect the evolutionary fine tuning of the host cell's stickiness according to the ecological requirements.

Conclusion

In the current study, we revealed the wide distribution of RepA-I-type biofilm plasmids among Rhodobacteraceae. The presence of >20 genes for polysaccharide metabolism exemplifies a functional specialization of extrachromosomal elements that has recently also been reported for Roseobacter plasmids containing the photosynthesis or FGC (Kalhoefer et al., 2011; Petersen et al., 2012; Frank et al., 2015b). The accumulation of different operons for related metabolic functions on the same plasmid facilitates horizontal transfers en bloc. The distribution of the rhamnose operon on at least 10 different plasmid types (Figure 1; Supplementary Table 1) reflects the flexible genome organization of roseobacters, and it is suggestive of a considerable frequency of genetic exchange. Moreover, the RepA-I-based plasmid phylogeny is incongruent with the species tree (Figures 1 and 4) and this contradiction is probably the consequence of horizontal transfers. We predict that even such a complex metabolic trait such as the capacity of biofilm formation can be horizontally transferred via biofilm plasmids between roseobacters, thereby providing the perspective of rapid adaptations to novel ecological niches.

Acknowledgments

We thank Claire Ellebrandt for excellent technical assistance, Robert Belas for providing us the strain Silicibacter sp. TM1040 and Torsten Thomas for the permission to use the draft genome of Phaeobacter sp. LSS9 for our phylogenomic analysis. The sequence data of Phaeobacter sp. LSS9, Roseobacter sp. R2A57 and Loktanella sp. SE62 were produced by the US Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute (http://www.jgi.doe.gov/) in collaboration with the user community. We would like to thank three anonymous reviewers for their very helpful comments on the manuscript and Irene Wagner-Döbler for her outstanding intellectual input. This work including two PhD stipends for OF and PB as well as the position of VM was supported by the Transregional Collaborative Research Center ‘Roseobacter' (Transregio TRR 51) of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on The ISME Journal website (http://www.nature.com/ismej)

Supplementary Material

References

- Abt B, Han C, Scheuner C, Lu M, Lapidus A, Nolan M et al. (2012). Complete genome sequence of the termite hindgut bacterium Spirochaeta coccoides type strain (SPN1T), reclassification in the genus Sphaerochaeta as Sphaerochaeta coccoides comb. nov. and emendations of the family Spirochaetaceae and the genus Sphaerochaeta. Stand Genomic Sci 6: 194–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W et al. (1997). Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res 25: 3389–3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsanelli E, Serrato RV, de Baura VA, Sassaki G, Yates MG, Rigo LU et al. (2010). Herbaspirillum seropedicae rfbB and rfbC genes are required for maize colonization. Environ Microbiol 12: 2233–2244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belas R, Horikawa E, Aizawa S, Suvanasuthi R. (2009). Genetic determinants of Silicibacter sp. TM1040 motility. J Bacteriol 191: 4502–4512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biebl H, Allgaier M, Lünsdorf H, Pukall R, Tindall BJ, Wagner-Döbler I. (2005). Roseovarius mucosus sp. nov., a member of the Roseobacter clade with trace amounts of bacteriochlorophyll a. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 55: 2377–2383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broughton WJ, Hanin M, Relic B, Kopciñska J, Golinowski W, Simsek S et al. (2006). Flavonoid-inducible modifications to rhamnan O antigens are necessary for Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234-legume symbioses. J Bacteriol 188: 3654–3663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruhn JB, Gram L, Belas R. (2007). Production of antibacterial compounds and biofilm formation by Roseobacter species are influenced by culture conditions. Appl Environ Microbiol 73: 442–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuthbertson L, Kos V, Whitfield C. (2010). ABC transporters involved in export of cell surface glycoconjugates. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 74: 341–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Alvise PW, Magdenoska O, Melchiorsen J, Nielsen KF, Gram L. (2014). Biofilm formation and antibiotic production in Ruegeria mobilis are influenced by intracellular concentrations of cyclic dimeric guanosinmonophosphate. Environ Microbiol 16: 1252–1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang H, Lovell CR. (2002). Numerical dominance and phylotype diversity of marine Rhodobacter species during early colonization of submerged surfaces in coastal marine waters as determined by 16S ribosomal DNA sequence analysis and fluorescence in situ hybridization. Appl Environ Microbiol 68: 496–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert M, Laaß S, Burghartz M, Petersen J, Koßmehl S, Wöhlbrand L et al. (2013). Transposon mutagenesis identified chromosomal and plasmid encoded genes essential for the adaptation of the marine bacterium Dinoroseobacter shibae to anaerobic conditions. J Bacteriol 195: 4769–4777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. (2004). MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res 32: 1792–1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank O, Michael V, Päuker O, Boedeker C, Jogler C, Rohde M et al. (2015. a). Plasmid curing and the loss of grip—The 65-kb replicon of Phaeobacter inhibens DSM 17395 is required for biofilm formation, motility and the colonization of marine algae. Syst Appl Microbiol 38: 120–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank O, Göker M, Pradella S, Petersen J. (2015. b). Ocean's twelve: Flagellar and biofilm chromids in the multipartite genome of Marinovum algicola DG898 exemplify functional compartmentalization. Environ Microbiol 17: 4019–4034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng H, Bruhn JB, Nielsen KF, Gram L, Belas R. (2008). Genetic dissection of tropodithietic acid biosynthesis by marine roseobacters. Appl Environ Microbiol 74: 1535–1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng H, Belas R. (2010). Molecular mechanisms underlying roseobacter-phytoplankton symbioses. Curr Opin Biotechnol 21: 332–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giebel HA, Brinkhoff T, Zwisler W, Selje N, Simon M. (2009). Distribution of Roseobacter RCA and SAR11 lineages and distinct bacterial communities from the subtropics to the Southern Ocean. Environ Microbiol 11: 2164–2178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraud MF, Naismith JH. (2000). The rhamnose pathway. Curr Opin Struct Biol 10: 687–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González JM, Covert JS, Whitman WB, Henriksen JR, Mayer F, Scharf B et al. (2003). Silicibacter pomeroyi sp. nov. and Roseovarius nubinhibens sp. nov., dimethylsulfoniopropionate-demethylating bacteria from marine environments. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 53: 1261–1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosink JJ, Herwig RP, Staley JT. (1997). Octadecabacter arcticus gen. nov., sp. nov., and O. antarcticus, sp. nov., nonpigmented, psychrophilic gas vacuolated bacteria from polar sea ice and water. Syst Appl Microbiol 20: 356–365. [Google Scholar]

- Hothorn T, Bretz F, Westfall P. (2008). Simultaneous inference in general parametric models. Biom J 50: 346–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalhoefer D, Thole S, Voget S, Lehmann R, Liesegang H, Wollher A et al. (2011). Comparative genome analysis and genome-guided physiological analysis of Roseobacter litoralis. BMC Genomics 12: 324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau SC, Tsoi MM, Li X, Plakhotnikova I, Wu M, Wong PK et al. (2004). Loktanella hongkongensis sp. nov., a novel member of the alpha-Proteobacteria originating from marine biofilms in Hong Kong waters. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 54: 2281–2284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le SQ, Gascuel O. (2008). An improved general amino acid replacement matrix. Mol Biol Evol 25: 1307–1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenk S, Moraru C, Hahnke S, Arnds J, Richter M, Kube M et al. (2012). Roseobacter clade bacteria are abundant in coastal sediments and encode a novel combination of sulfur oxidation genes. ISME J 6: 2178–2187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Stoeckert CJ Jr, Roos DS. (2003). OrthoMCL: identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome Res 13: 2178–2189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindhout T, Lau PC, Brewer D, Lam JS. (2009). Truncation in the core oligosaccharide of lipopolysaccharide affects flagella-mediated motility in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 via modulation of cell surface attachment. Microbiology 155: 3449–3460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo H, Moran MA. (2014). Evolutionary ecology of the marine roseobacter clade. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 78: 573–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDougald D, Rice SA, Barraud N, Steinberg PD, Kjelleberg S. (2011). Should we stay or should we go: mechanisms and ecological consequences for biofilm dispersal. Nat Rev Microbiol 10: 39–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Cánovas MJ, Quesada E, Martínez-Checa F, del Moral A, Béjar V. (2004). Salipiger mucescens gen. nov., sp. nov., a moderately halophilic, exopolysaccharide-producing bacterium isolated from hypersaline soil, belonging to the alpha-Proteobacteria. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 54: 1735–1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClain J, Rollo DR, Rushing BG, Bauer CE. (2002). Rhodospirillum centenum utilizes separate motor and switch components to control lateral and polar flagellum rotation. J Bacteriol 184: 2429–2438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller TR, Hnilicka K, Dziedzic A, Desplats P, Belas R. (2004). Chemotaxis of Silicibacter sp. strain TM1040 toward dinoflagellate products. Appl Environ Microbiol 70: 4692–4701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller TR, Belas R. (2006). Motility is involved in Silicibacter sp. TM1040 interaction with dinoflagellates. Environ Microbiol 8: 1648–1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran MA, Buchan A, González JM, Heidelberg JF, Whitman WB, Kiene RP et al. (2004). Genome sequence of Silicibacter pomeroyi reveals adaptations to the marine environment. Nature 432: 910–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran MA, Belas R, Schell MA, González JM, Sun F, Sun S et al. (2007). Ecological genomics of marine Roseobacters. Appl Environ Microbiol 73: 4559–4569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton RJ, Griffin LE, Bowles KM, Meile C, Gifford S, Givens CE et al. (2010). Genome characteristics of a generalist marine bacterial lineage. ISME J 4: 784–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Toole GA, Kolter R. (1998). Initiation of biofilm formation in Pseudomonas fluorescens WCS365 proceeds via multiple, convergent signalling pathways: a genetic analysis. Mol Microbiol 28: 449–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partridge JD, Harshey RM. (2013). Swarming: flexible roaming plans. J Bacteriol 195: 909–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavelka MS Jr, Wright LF, Silver RP. (1991). Identification of two genes, kpsM and kpsT, in region 3 of the polysialic acid gene cluster of Escherichia coli K1. J Bacteriol 173: 4603–4610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavelka MS Jr, Hayes SF, Silver RP. (1994). Characterization of KpsT, the ATP-binding component of the ABC-transporter involved with the export of capsular polysialic acid in Escherichia coli K1. J Biol Chem 269: 20149–20158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen J. (2011). Phylogeny and compatibility: plasmid classification in the genomics era. Arch Microbiol 193: 313–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen J, Brinkmann H, Pradella S. (2009). Diversity and evolution of repABC type plasmids in Rhodobacterales. Environ Microbiol 11: 2627–2638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen J, Brinkmann H, Berger M, Brinkhoff T, Päuker O, Pradella S. (2011). Origin and evolution of a novel DnaA-like plasmid replication type in Rhodobacterales. Mol Biol Evol 28: 1229–1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen J, Brinkmann H, Bunk B, Michael V, Päuker O, Pradella S. (2012). Think pink: photosynthesis, plasmids and the Roseobacter clade. Environ Microbiol. 14: 2661–2672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen J, Frank O, Göker M, Pradella S. (2013). Extrachromosomal, extraordinary and essential-the plasmids of the Roseobacter clade. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 97: 2805–2815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippe H. (1993). MUST, a computer package of Management Utilities for Sequences and Trees. Nucleic Acids Res 21: 5264–5272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poggio S, Abreu-Goodger C, Fabela S, Osorio A, Dreyfus G, Vinuesa P et al. (2007). A complete set of flagellar genes acquired by horizontal transfer coexists with the endogenous flagellar system in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J Bacteriol 189: 3208–3216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porsby CH, Nielsen KF, Gram L. (2008). Phaeobacter and Ruegeria species of the Roseobacter clade colonize separate niches in a Danish Turbot (Scophthalmus maximus-rearing farm and antagonize Vibrio anguillarum under different growth conditions. Appl Environ Microbiol 74: 7356–7364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradella S, Allgaier M, Hoch C, Päuker O, Stackebrandt E, Wagner-Döbler I. (2004). Genome organization and localization of the pufLM genes of the photosynthesis reaction center in phylogenetically diverse marine Alphaproteobacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 70: 3360–3369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradella S, Päuker O, Petersen J. (2010). Genome organization of the marine Roseobacter clade member Marinovum algicola. Arch Microbiol 192: 115–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahim R, Burrows LL, Monteiro MA, Perry MB, Lam JS. (2000). Involvement of the rml locus in core oligosaccharide and O polysaccharide assembly in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology 146: 2803–2814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rashid MH, Kornberg A. (2000). Inorganic polyphosphate is needed for swimming, swarming, and twitching motilities of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 4885–4590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. (2014) R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

- Seyedsayamdost MR, Case RJ, Kolter R, Clardy J. (2011. a). The Jekyll-and-Hyde chemistry of Phaeobacter gallaeciensis. Nat Chem 3: 331–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seyedsayamdost MR, Carr G, Kolter R, Clardy J. (2011. b). Roseobacticides: small molecule modulators of an algal-bacterial symbiosis. J Am Chem Soc 133: 18343–18349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiba T. (1991). Roseobacter litoralis gen. nov., sp. nov., and Roseobacter denitrificans sp. nov., aerobic pink-pigmented bacteria which contain bacteriochlorophyll a. Syst Appl Microbiol 14: 140–145. [Google Scholar]

- Slightom RN, Buchan A. (2009). Surface colonization by marine roseobacters: integrating genotype and phenotype. Appl Environ Microbiol 75: 6027–6037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soora M, Tomasch J, Wang H, Michael V, Petersen J, Engelen B et al. (2015). Oxidative stress and starvation in Dinoroseobacter shibae: the role of extrachromosomal elements. Front Microbiol 6: 233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spring S, Scheuner C, Lapidus A, Lucas S, Glavina Del Rio T, Tice H et al. (2010). The genome sequence of Methanohalophilus mahii SLPT reveals differences in the energy metabolism among members of the Methanosarcinaceae inhabiting freshwater and saline environments. Archaea 2010: 690737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A. (2006). RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics 22: 2688–2690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sule P, Belas R. (2013). A novel inducer of Roseobacter motility is also a disruptor of algal symbiosis. J Bacteriol 195: 637–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swofford DL. (2002) PAUP*: Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (*and Other Methods), Version 4.0 b10. Sinauer Associates: Sunderland. [Google Scholar]

- Talavera G, Castresana J. (2007). Improvement of phylogenies after removing divergent and ambiguously aligned blocks from protein sequence alignments. Syst Biol 56: 564–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. (1997). The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res 25: 4876–4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Thierry JCC, Poch O. (2003). RASCAL: rapid scanning and correction of multiple sequence alignments. Bioinformatics 19: 1155–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thole S, Kalhoefer D, Voget S, Berger M, Engelhardt T, Liesegang H et al. (2012). Phaeobacter gallaeciensis genomes from globally opposite locations reveal high similarity of adaptation to surface life. ISME J 6: 2229–2244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaas LAI, Sikorski J, Hofner B, Buddruhs N, Fiebig A, Klenk HP et al. (2013). opm: An R package for analysing OmniLog® Phenotype MicroArray Data. Bioinformatics 29: 1823–1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega-Baray B, Domenzain C, Rivera A, Alfaro-López R, Gómez-César E, Poggio S et al. (2015). The flagellar set Fla2 in Rhodobacter sphaeroides is controlled by the CckA pathway and is repressed by organic acids and the expression of Fla1. J Bacteriol 197: 833–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voget S, Wemheuer B, Brinkhoff T, Vollmers J, Dietrich S, Giebel HA et al. (2015). Adaptation of an abundant Roseobacter RCA organism to pelagic systems revealed by genomic and transcriptomic analyses. ISME J 9: 371–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner-Döbler I, Biebl H. (2006). Environmental biology of the marine Roseobacter lineage. Annu Rev Microbiol 60: 255–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner-Döbler I, Ballhausen B, Berger M, Brinkhoff T, Buchholz I, Bunk B et al. (2010). The complete genome sequence of the algal symbiont Dinoroseobacter shibae: a hitchhiker's guide to life in the sea. ISME J 4: 61–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Tomasch J, Jarek M, Wagner-Döbler I. (2014). A dual-species co-cultivation system to study the interactions between Roseobacters and dinoflagellates. Front Microbiol 5: 311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichard T. (2015). Exploring bacteria-induced growth and morphogenesis in the green macroalga order Ulvales (Chlorophyta). Front Plant Sci 6: 86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D, Hugenholtz P, Mavromatis K, Pukall R, Dalin E, Ivanova NN et al. (2009). A phylogeny-driven genomic encyclopaedia of Bacteria and Archaea. Nature 462: 1056–1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zan J, Cicirelli EM, Mohamed NM, Sibhatu H, Kroll S, Choi O et al. (2012). A complex LuxR-LuxI type quorum sensing network in a roseobacterial marine sponge symbiont activates flagellar motility and inhibits biofilm formation. Mol Microbiol 85: 916–933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.