Abstract

The South Asian (SA) population has been underrepresented in research linking discrimination with health indicators; studies that focus on the unique cultural and psychosocial experiences of different SA subgroups are needed. The purpose of this study was to examine associations between self-reported discrimination and mental health among Asian Indians (AIs), and whether traditional cultural beliefs (believing that South Asian cultural traditions should be practiced in the US), coping style, and social support moderated these relationships. Asian Indians (N = 733) had been recruited from community-based sampling frames for the Mediators of Atherosclerosis in South Asians Living in America (MASALA) study were included in this analysis. Multiple linear regression analyses were employed to evaluate relationships between discrimination and depressive symptoms, anger, and anxiety. Participants (men = 54%) were on average 55 years of age and had high levels of English proficiency, education, and income. Higher reports of discrimination were significantly associated with higher depressive symptoms, B = .27 (.05) p < .001, anger, B = .08 (.01), p < .001, and anxiety, B = .10 (.01), p < .001. Associations between discrimination and anger, B = −.005 (.002), p = .02, were weakest among those with stronger cultural beliefs. The link between discrimination and anxiety was attenuated by an active coping style, B = −.05 (.03), p = .04. In sum, self-reported discrimination appeared to adversely impact the mental health of AIs. Discrimination may be better coped with by having strong traditional cultural beliefs and actively managing experiences of discrimination.

Numerous reports document how exposure to discrimination has health harming effects among ethnic minority groups in the United States (Gee, Ro, Shariff-Marco, & Chae, 2009; Krieger & Sidney, 1996; Paradies, 2006). Specifically, self-reported experiences of discrimination have been linked with anxiety, depression, hypertension, mortality, and obesity among Latinos and African Americans (Barnes et al., 2008; Brondolo, Rieppi, Kelly, & Gerinet, 2003; Finch & Vega, 2003; Krieger & Sidney, 1996). However, few studies have examined how discrimination influences the health of diverse Asian American groups, in particular, the health of South Asians (SAs) in the United States (Gee et al., 2009; Paradies, 2006). Studies in which South Asian (SA) groups are aggregated with other Asian American groups demonstrate strong correlations between discrimination and poorer mental and physical health, including increased psychological distress, anxiety, and cardiovascular conditions (Gee et al., 2009; Hahm, Ozonoff, Gaumond, & Sue, 2010; Lam, 2007; Tummala-Narra, Alegria, & Chen, 2012). However, the majority of studies on discrimination and health among Asian Americans aggregate diverse SA subgroups (Gee, Spencer, Chen, & Takeuchi, 2007; Gee, Ro, Gavin, & Takeuchi, 2008; Hahm et al., 2010). Despite rapid growth of the SA population in the United States, little is known about the effect self-reported discrimination may have on their health, signifying a critical gap in discrimination and ethnic minority health studies.

South Asians in the United States

There are 3.4 million SAs living in the United States, the vast majority of which emigrated from India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh (United States Census Bureau, 2010). The majority of the SAs living in the United States are Asian Indian (AI; 2,843,391). States most densely populated with SAs are: California, New York, New Jersey, Texas, and Illinois (US Census Bureau, 2010). Notably, the SA community is extremely diverse, as several languages are spoken and myriad faiths and spiritualities are practiced (South Asian American Leaders of Tomorrow, 2012).

Exposure to discrimination among South Asians

South Asians have endured an unfortunate long-standing legacy of discrimination through the implementation of anti-immigration laws, experiences of violent hate crimes, and chronic insults in everyday society (Chan, 1991; Chen, 2000; Hess, 1974; New York City Commission on Human Rights, 2003). Specifically, in the United States v. Bhagat Singh trial of 1923, the Supreme Court revoked and denied citizenship to SAs because they were not “white” (Hess, 1974). In more recent times, self-proclaimed “dotbusters” terrorized and attacked several SAs in Jersey City, New Jersey, between 1987 and 1988 (Chen, 2000; Gutierrez, 1996). Since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, many SAs reported concerns over racial profiling and there have been reports of increasing violence, harassment, and scrutiny (Chandrasekhart, 2003; South Asian American Leaders of Tomorrow, 2001; 2012). Although there are little data on self-reported discrimination among SAs, over half of SAs in two epidemiological surveys (55.5% California Health Interview Survey, N = 413; 50.6% National Latino and Asian American Survey, N = 170) reported experiencing discrimination or unfair treatment (Alegria, & Takeuchi, 2009; California Health Interview Survey, 2003).

Given the history of reports of discrimination among SAs, the model minority myth may be a surprising, ideological form of discrimination against SAs. Since the 1960s, the model minority myth has suggested that SAs are an ideal ethnic minority group, as many have achieved educational and economic success (Kwon & Au, 2010). However, the myth has failed to recognize the health and social problems faced by SAs (South Asian American Leaders of Tomorrow, 2001). In sum, SAs have endured a history of exposure to discrimination in the US yet it is unclear how such discrimination may impact the health of SAs. Thus, associations between self-reported discrimination and mental health indicators among SAs warrant scientific investigation.

Conceptual Framework Linking Self-reported Discrimination and Health

Self-reported discrimination is commonly conceptualized as a chronic stressor that triggers physiological health responses such as excess cortisol secretion and hypothalamic– pituitary–adrenal axis dysregulation (McEwen, 2004; Williams & Mohammed, 2009). Several studies have posited that stress theory underlies links between discrimination and poorer health (Hahm et al., 2010; Liang, et al., 2007; Yoshihama, Bybee, & Blazevski, 2012). However, given the ubiquitous and diffuse nature of discrimination, interpreting discriminatory acts as stressful, or the cognitive appraisal of specific discriminatory events, may not always be clear or possible (Williams & Mohammed, 2009). Regardless of the extent to which discrimination is perceived by the individual, Hobfoll’s (2001) conservation of resources (COR) theory alternatively posits that discrimination-related stress may have a lesser impact on individuals who are able to utilize support systems and have significant psychosocial resources. These resources may be religious involvement, organizational involvement with those who have shared interests, positive feelings about one’s self, and loyalty of friends/family (Hobfoll, 2001). Conversely, for those with weak or nonexistent resource systems, discrimination-related stress may be more likely to adversely impact their health.

The COR theory may be especially salient for SAs, given that their identities, traditional cultural beliefs, personal values, and psychosocial resources are often rooted within the context of their wider SA community (Das & Kemp, 1997; Frey & Roysircar, 2006). For many SAs, familial and ethnic community support are major resources that enable managing acculturation-related challenges (Das & Kemp, 1997). Therefore, SAs with strong familial and community resources may have additional resources that can buffer the effects of discrimination-related stress. Conversely, if familial or community resources are not available to SAs, discrimination-related stress may be more readily encountered or difficult to manage. Therefore, COR theory is relevant to SAs, in that the absence or presence of their personal, social, or ethnic community resources may provide the differential in which discrimination-related stress is managed.

Potential Moderators Based on Conservation of Resources Theory

The extent to which SAs have social support, hold traditional cultural beliefs, and cope with discriminatory experiences can be considered specific personal, social, and community resources that may influence how SAs encounter or manage experiences of discrimination (Hobfoll, 2001). For example, if one has the resource of social support it may be easier to manage discrimination-related stress. However, it is unclear to what extent social support, traditional cultural beliefs, and coping style may exacerbate or attenuate pathways between self-reported discrimination and mental health indicators among SAs (Mossakowski, 2003; Tummala-Narra et al., 2012; Yip, Gee, & Takeuchi, 2008; Yoo & Lee, 2005).

Findings are mixed in terms of whether adherence to traditional cultural beliefs versus adoption of mainstream cultural beliefs influences links between self-reported discrimination and health among Asian Americans (Gee, 2002). Notably, concepts such as ethnic identity and acculturation share significant conceptual overlap and are measured in various ways throughout health studies (Berry, 1979; Gee et al., 2009; Yoo & Lee, 2008). Therefore it is difficult to draw conclusions based upon how adherence to specific cultural beliefs influences discrimination and health pathways. However, ethnic identity, which has been defined as the degree to which one values and identifies with a particular ethnic group (Yoo & Lee, 2008), has been studied as a moderator in several discrimination and Asian American health studies (Mossakowski, 2003; Yip et al., 2008; Yoo & Lee, 2008). In studies of with Filipinos (Mossakowski, 2003) and diverse Asian American groups (Yoo & Lee, 2008), a stronger ethnic identity was a protective factor in the pathway between discrimination and mental health. In contrast, Yoo and Lee (2008) demonstrated that ethnic identity exacerbated the relationship between discrimination and mental health among Asian Americans. In a study by Yip and colleagues (2008), ethnic identity exacerbated the relationship between discrimination and psychological distress for Asian Americans in their 30s and for those over 51 years of age. However, in the same study, ethnic identity was a protective factor on the discrimination and psychological distress pathway for those in their 40s. However, to our knowledge, no published studies have examined the manner in which traditional cultural beliefs may influence links between discrimination and health among SAs.

Social support

A wide body of literature has shown that social support can be an extremely beneficial resource in the management of life stressors (Uchino, Cacioppo, & Kiecolt-Glaser, 1996). However, social support as a potentially protective factor in pathways between self-reported discrimination and health is understudied and unclear. Gee et al. (2006) demonstrated that social or emotional forms of support did not moderate relationships between discrimination and several health conditions among Asian Americans in Honolulu and San Francisco. However, social support, in the form of talking to friends and family, attenuated a link between discrimination and engaging in unprotected sex among gay Asian Pacific Islander men (Yoshikawa, Wilson, Chae, & Cheng, 2004). In the one known discrimination, health, and moderation study among SAs (N = 169), social support was a protective factor in the association between discrimination and depression (Tummala-Narra et al., 2012).

Coping style

Employing an active, problem-oriented coping style may mitigate discrimination-related stress and health pathways (Beasley, Thompson, & Davidson, 2003). In a study of Koreans in Ontario, Canada (N = 180), the link between discrimination and psychological distress was less robust when participants personally confronted the offender or reported their experiences of discrimination to authorities thereby coping in an active, problem-solving manner (Noh & Kaspar, 2003). Additionally, Krieger and Sidney (1996) demonstrated that African American women who internalized discrimination had higher blood pressure levels compared with women who addressed the discriminatory experiences.

With the exception of Tummala-Narra et al.’s 2012 study demonstrating the protective effects of social support on self-reported discrimination and mental health pathways, it is not clear how potentially protective psychosocial resources (Hobfoll, 2001), such as having strong traditional cultural beliefs and an active coping style, may influence discrimination and mental health pathways for SAs. Evaluating the psychosocial factors that moderate pathways between discrimination and mental health may provide important information on how to interrupt such noxious links.

Purpose and Hypotheses

The purpose of this cross-sectional study was to address the gap in understanding of associations between self-reported discrimination and mental health and potential moderators of these pathways among the largest SA group in the United States: Asian Indian (AI) immigrants. Specifically, this study examined relationships between reports of discrimination and three mental health indicators (depressive symptoms, anger, and anxiety) and evaluated whether traditional cultural beliefs, coping style, and social support moderated these relationships. We hypothesized there would (1) be positive relationships between reports of discrimination and all three mental health indicators. Next, we hypothesized that (2a) having stronger traditional cultural beliefs (2b) increased social support (as found in Tummala-Narra et al.’s 2102 study), and (2c) utilizing an active coping style in response to discriminatory experiences would be protective factors in pathways between reports of discrimination and poorer mental health indicators.

Method

Participants

The AI cohort of the Mediators of Atherosclerosis in South Asians Living in America (MASALA) baseline 2010–2013 study was included in the current study analyses. The primary aim of the MASALA study was to determine risk factors (sociocultural, behavioral, and biologic) for subclinical atherosclerosis and compare the prevalence with four other U.S. race/ethnic groups in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. The MASALA study included SAs (N = 906), the majority of which were AIs, and recruited from community-based sampling frames from the San Francisco Bay Area and greater Chicago area between October 2010 and March 2013. Study methods have been detailed in a previous report (Kanaya et al., 2013). Given the richness of psychosocial data collected in the MASALA baseline survey, the current study focused on exploring links between discrimination and mental health among AIs born in India (N = 757). Foreign-born AIs were isolated for analyses, as their perceptions of discrimination are likely to differ from AIs born in the United States and SA Bangladeshi and Pakistani groups in the MASALA study (Gee et al., 2007). The institutional review boards at Northwestern University and the University of California, San Francisco approved the MASALA study.

Data for the current study reflect baseline examination eligibility criteria for the MASALA study, which were individuals who had at least three grandparents of SA origin, those who identified as SA, were able to speak or read English, Hindi, or Urdu, and who were free of cardiovascular disease at baseline. The age criteria for participants were defined as 40-84 years because the MASALA study aimed to determine the risk factors for subclinical atherosclerosis in South Asians and compare the prevalence with racial/ethnic groups in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis, which had similar age groups. Other exclusion criteria are detailed elsewhere (Kanaya et al., 2013).

Measures

Main variables

Self-reported Discrimination

The Everyday Discrimination Scale (EDS) has been rigorously tested for reliability and validity with Asian American adults (Gee et al., 2006; Gee et al., 2007; Mossakowski, 2003). The EDS includes nine items and evokes self-reported frequency responses of unfair, chronic, and routine experiences of discrimination. Examples of question items are: (1) Have you ever been treated with less respect than other people; and (2) Have you received poorer services than others in restaurants or stores? (Williams, Yu, Jackson, & Anderson, 1997). As per Williams and Mohammed (2009), participants choose from the following response options after each of the nine questions: almost every day, at least once a week, a few times a month, a few times a year, less than once a year, or never. The EDS does not include a question asking participants if they attributed experiencing discrimination to race, having an accent, or other personal characteristics. Therefore, the non-attributional approach likely captures a wider range of discrimination experiences without subjecting participants to the difficult cognitive task of answering “why” they have experienced discrimination (Williams & Mohammed, 2009). The following point system is used to code responses: almost every day = 6, at least once a week = 5, a few times a month = 4, a few times a year = 3, less than once a year = 2, never = 1. With nine items on the EDS, the lowest possible total score is nine and the highest possible score is 54, which indicates the maximum amount of discrimination experienced. A Cronbach’s alpha of .87 was produced for the EDS among AIs in the study.

Mental health indicators

Mental health indicators measured in the study were depressive symptoms, anger, and anxiety. All mental health indicators were coded into low to high scales, such that lower scores reflected fewer symptoms or better mental health and higher scores represent more symptoms or worse mental health.

Depressive symptoms

The 20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CES-D) depressive symptoms index (0–60 point range) was analyzed as a continuous measure (Radloff, 1977). Depressive symptoms such as restlessness, feeling lonely, and having crying spells were assessed. Participants were provided with four response options ranging from experiencing such symptoms “rarely or none of the time” to “most of the time.” The Cronbach’s alpha for AIs in the study was .65.

Speilberger Trait Anger and Anxiety scales

The Spielberger Trait Anger Scale (10 items; 10–40 point range) evaluates feelings of anger through questions related to temper, being “hot headed,” or “flying off the handle” (Spielberger, 1980). The Spielberger Trait Anxiety Scale (10 items; 10–40 point range) likewise evaluates feelings of anxiety based on questions such as “I feel nervous and restless” and had a Cronbach’s alpha of .51 (Spielberger, 1980). There were four response options for the anxiety and anger scales ranging from “almost never” to “almost always.” The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .81.

Moderator variables

Measuring traditional cultural beliefs

The degree to which SAs in the United States hold traditional cultural beliefs and practices and maintain close cultural ties with one’s ethnic community have been considered key aspects of acculturation (Kanaya et al., 2014). Researchers of the MASALA Study utilized prior qualitative studies with AIs to develop a traditional cultural beliefs scale. This 7-item traditional cultural beliefs assessed to what extent participants believed the following behaviors should be practiced in America: (1) religious ceremonies or rituals, (2) consuming South Asians sweets during ceremonies, (3) the spiritual practice of fasting, (4) a joint family living structure, (5) arranged marriage practices, (6) consuming traditional ethnic foods, and (7) using traditional spices for health purposes (Kanaya et al., 2014). The scale included 5 response options ranging from absolute agreement to not agreeing at all with the 7 items. Scores had a possible range of 0–28, with lower scores reflecting stronger cultural beliefs and higher scores reflecting weaker cultural beliefs. Kanaya et al. (2014) reported a Cronbach’s alpha of .83 for MASALA participants. For the AI cohort in the current study, a reliability of .81 was established.

Social support

Social support was measured using a 6-item, continuous low social support (0) to high social support (24) scale, which included questions such as “Is there someone available to give you good advice about a problem?” (ENRICHD Investigators, 2000). There were 4 response options ranging from experiencing items on the social support questionnaire “none of the time” to “all of the time.” This measure had a Cronbach’s alpha of .88 among AIs in this study.

Coping style

After answering discrimination-related questions on the EDS participants were then asked whether they actively or passively coped with discrimination potentially experienced. This binary coping measure evaluated if participants (1) accepted unfair treatment (discrimination) as a fact of life or (2) tried to do something about it. The active/passive coping question has been included in several studies where the EDS has been utilized (Krieger & Sidney, 1996; Paradies, 2006).

Covariates

The following variables were binary measures: sex (men or women), education (those with less than a bachelor’s degree versus those with a bachelor’s degree or higher), working outside the home versus working inside the home, site (Chicago versus San Francisco), antidepressant medication (yes/no), hypertension (yes and those treated to goal/no), and marital status (married/living with partner versus not married/living with partner). Household income divided into three categories (low: <$39,000/year; medium: $40,000–$74,999; and high >$75,000) was used as the reference variable in analyses. Age and years in the United States were coded as interval variables. An English language proficiency scale included three items: (1) the ability to speak, (2) read hospital materials, and (3) learn about their medical condition. A continuous measure was derived from responses reflecting low English language proficiency = 0 to high English language proficiency = 12. Most participants had insurance (92%) and reported a religious affiliation (73% Hindu); given their limited distribution, these variables were not included in analyses.

Results

Statistical Approach

To justify multivariable analyses, Pearson correlations were calculated across the main predictors, moderator variables, and covariates. Sequential multiple linear regression and moderation analyses were used to evaluate relationships between discrimination and mental health indicators and moderating factors. All mental health indicators were positively skewed and were log-transformed. The 24 participants with missing income data were excluded from analyses; a final sample size of 733 AIs were included in all statistical analyses.

To test the main effects of self-reported discrimination in relationship to mental health, three mental health indictors (depressive symptoms, anger, and anxiety) were tested as outcome variables in three separate models. In each of the three models, variables considered to have potentially the most significant impact on mental health outcomes were entered first. Self-reported discrimination was entered last in all models to determine the unique effect of discrimination on mental health indicators above and beyond the effect of control variables on mental health indicators. Control variables sharing potential conceptual overlap (demographics/medications, social support/acculturation-related factors) were entered in a step-by-step fashion in the regression models: (1) age, sex, education, work status, site, income, antidepressant medication, and hypertension; (2) years in the United States, marital status, social support, traditional cultural beliefs, and English language proficiency; (3) discrimination. A dummy coding scheme was used include the categorically coded income variable with high income (>$75,000) as the reference group.

Interaction terms were then created by centering continuous moderators and multiplying each potential moderator (traditional cultural beliefs, social support, and active/passive coping) by the centered predictor variable, self-reported discrimination. These three interaction terms were analyzed separately in a one-step regression including all the covariates for significant discrimination and mental health analyses. For example, in the regression evaluating coping style as a potential moderator traditional cultural beliefs and social support were included as covariates. For significant interactions involving continuously scaled moderators, simple slopes testing was required.

Participant demographics

Participants (men = 54%) were on average 55 years of age (range: 40-83 years) and had high levels of English proficiency, education, and income. On average, participants had lived 27 (SD = 11) years in the US. There were 349 women (n = 143 Chicago; n = 206 San Francisco) and 408 men (n = 196 Chicago; n = 212 San Francisco) in the study.

Chi - square tests of independence indicated significant relationships between gender and study site and income and study site. There were slightly more men MASALA participants from the Chicago site (58% versus 51% men from the San Francisco site). In the San Francisco site slightly more women (49%) participated in comparison to the Chicago site (42%). However the gender and study site analysis was marginally significant: X2(1, N = 757) = 3.797, p = .05 Additionally, the AI cohort in San Francisco tended to have higher income levels than AIs in Chicago X2(1, N = 757) = 13.342, p < .001. There were no statistically significant differences at the p = .05 level when analyzing differences in other demographic factors (marital status, education, years in US) according to study site.

Preliminary data and analyses

Self-reported discrimination scores

Total discrimination scores were divided by 6 to reflect an average value of 1.66 (SD = .66) on a 1 (no discrimination) to 6 (maximum discrimination). Therefore, participants experienced lower levels of discrimination, or various discriminatory events roughly less than once a year. Mental health indicator scores were all positively skewed: depressive symptoms, Mdn = 6 (IQR = 7); M = 7.47 (SD = 7.00), anger, Mdn = 15 (IQR = 5); M = 15.94 (SD = 3.83), and anxiety, Mdn = 15 (IQR = 5); M = 15.97 (SD = 4.38).

Pearson’s bivariate correlations revealed that discrimination was associated with age, r = −.08, p = .02, and several main and moderator variables as reflected in Table 2: anger, r = .27, p < .001; anxiety, r = .35, p < .001; depressive symptoms, r = .39, p < .001; and social support, r = −.35, p < .001. Correlations did not exceed the .70 level; therefore, multicollinearity was not a major concern.

Table 2.

Pearson’s Correlations between Main Variables and Moderators (N = 757)

| Variable | Discrimination | Age | Depressive Symptoms |

Anxiety | Anger | Traditional Cultural Beliefs |

Social Support |

Years in US |

||

| M | SD | r | r | r | r | r | r | r | r | |

| Discrimination | 1.66 | .66 | 1 | |||||||

| Age | 55.54 | 9.42 | .08* | 1 | ||||||

| Depressive Symptoms |

7.47 | 7.01 | .39** | .07 | 1 | |||||

| Anxiety | 15.97 | 4.38 | .35** | .01 | .67** | 1 | ||||

| Anger | 15.94 | 3.83 | .27** | −.12* | .37** | .39** | 1 | |||

| Traditional Cultural Beliefs |

14.19 | 6.19 | −.05 | −.01 | −.12** | −.09* | −.11** | 1 | ||

| Social Support | 19.03 | 4.83 | −.35** | −.04 | −.47** | −.33** | −.19 | −.02 | 1 | |

| Years in US | 27.25 | 10.80 | .02 | .52** | .04 | .02 | −.10** | .22** | −.05 | 1 |

Note:

p < .05.

p < .01.

Main analyses

Self-reported discrimination and mental health

In sequential multiple linear regression models, higher reports of discrimination were significantly associated with higher depressive symptoms, B = .27 (.05) p < .001; anger, B = .08 (.01), p < .001, and anxiety, B = .10 (.01), p < .001. Table 3 presents the third and final step of all main effects. Consistent with the first hypothesis of the study, for every unit increase in self-reported discrimination, there was a 27% increase in depressive symptoms, an 8% increase in anger, and a 10% increase in anxiety after accounting for demographic, acculturation-related, and social support factors.

Table 3.

Sequential Regression Analyses for Relationships between Discrimination and Mental Health Indicators (N = 733)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Outcome | Depressive symptoms | Anger | Anxiety | ||||||

| Variable | B | SE B | β | B | SE(B) | β | B | SE B | β |

| Step 1 | |||||||||

| Age | .002 | .004 | .022 | −.002* | .001 | −.093 | −.002 | .001 | −.085 |

| Sex | .13* | .064 | .076 | .031 | .018 | .068 | .031 | .019 | .060 |

| Education | −.24 | .13 | −.066 | .068 | .036 | .071 | −.005 | .039 | −.004 |

| Occupation | −.073 | .073 | −.038 | −.005 | .020 | −.010 | −.055* | .022 | −.094 |

| Study site | −.049 | .059 | −.028 | .006 | .016 | .014 | .004 | .018 | .008 |

| Antidepressant medication |

0.51* | .21 | .084 | .20** | .059 | .12 | .190 | .064 | .101 |

| Hypertension | −.004 | .066 | −.002 | .038* | .018 | .079 | .021 | .020 | .038 |

| Income >$40k | .16 | .10 | .061 | .008 | .028 | .011 | .042 | .030 | .052 |

| Income $40k-$75k | .34** | .093 | .14 | .030 | .026 | .044 | .089** | .028 | .11 |

| Step 2 | |||||||||

| Social Support | −.051** | .006 | −.29 | −.005* | .002 | −.102 | −.011** | .002 | −.20 |

| Marital Status | −.15 | .12 | −.045 | .010 | .032 | .012 | −.052 | .035 | −.054 |

| English proficiency |

−.008 | .012 | −.021 | −.007* | .003 | −.069 | −.002 | .004 | −.019 |

| Traditional Cultural Beliefs |

−.012** | .005 | −.086 | −.003 | .001 | −.070 | −.003 | .002 | −.068 |

| Years lived in US | .003 | .003 | .037 | −.001 | .001 | −.056 | .001 | .001 | .045 |

| Step 3 | |||||||||

| Discrimination | .27** | .05 | .21 | .08** | .01 | .23 | .10** | .01 | .27 |

|

| |||||||||

| R2 | .27 | .14 | .23 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| F for change in R2 | F (15, 643) =15.84** | F (15, 708) = 7.88** | F (15, 708) = 13.66** | ||||||

Note:

p < .05.

p < .01.; These data represent the third and final step of the main effects models.

Traditional cultural beliefs, social support, and coping style as moderators

Table 4 presents significant moderators of pathways between self-reported discrimination and mental health indicators. Traditional cultural beliefs moderated the association between discrimination and anger (interaction term: B = −.005 [.002] p = .02). Traditional cultural beliefs did not moderate relationships between discrimination and depressive symptoms or discrimination and anxiety (all p values > .05).

Table 4.

Moderation Analyses for Relationships between Discrimination and Anger and Discrimination and Anxiety (N = 733)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Outcome | Anger | Anxiety | ||||

| Variable | B | SE B | β | B | SE B | B |

| Age | −.002* | .001 | −.10 | −.003* | .001 | −.094 |

| Sex | .030 | .018 | .065 | .037* | .019 | .071 |

| Education | .063 | .036 | .066 | .010 | .039 | .009 |

| Occupation | −.003 | .020 | −.006 | −.046* | .022 | −.077 |

| Study site | .009 | .016 | .019 | .006 | .018 | .012 |

| Antidepressant medication |

.17* | .06 | .11 | .20* | .064 | .11 |

| Hypertension | .035* | .018 | .075 | .017 | .020 | .031 |

| Income >$40k | .009 | .028 | .013 | .036 | .030 | .044 |

| Income $40k-$75k | .024 | .025 | .035 | .093* | .028 | .12 |

| Social Support | −.005* | .002 | −.10 | −.010** | .002 | −.19 |

| Marital Status | .013 | .032 | .015 | −.056 | .035 | −.057 |

| English proficiency | −.006 | .003 | −.062 | −.002 | .004 | −.017 |

| Years lived in US | −.001 | .001 | −.055 | .001 | .001 | .051 |

| Traditional Cultural Beliefs |

−.003 | .002 | −.064 | |||

| Discrimination_C | .078* | .013 | .23 | .13** | .019 | .33 |

| Traditional Cultural Beliefs_C |

−.003* | .001 | −.079 | |||

|

Discrimination_C_X_

Traditional Cultural Beliefs_C |

−.005* | .002 | −.080 | |||

| Active/Passive Coping | −.057* | .018 | −.11 | |||

|

Discrimination_C _X_

Active Coping |

−.054* | .026 | −.10 | |||

|

| ||||||

| R2 | .14 | .22 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| F for change in R2 | F (16,731)=7.52** | F (17, 722)=13.09** | ||||

Note:

p < .05.

p < .01.; These data represent two separate one-step linear regression models.

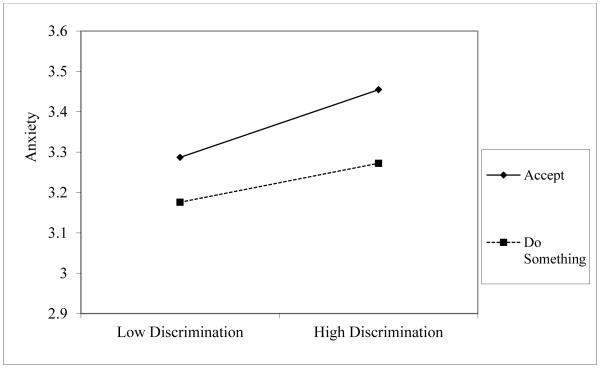

Coping style moderated the association between discrimination and anxiety, B = −.05 (.03), p = .04. Coping style did not moderate pathways between discrimination and depressive symptoms or discrimination and anger (all p values > .05).

The association between discrimination and anxiety was modified by whether active coping (participants did something about discrimination experienced) or passive coping (participants accepted discrimination as a fact of life) was utilized, B = −.05 (.03), p = .04. Coping style did not moderate pathways between discrimination and depressive symptoms or discrimination and anger (all p values > .05).

Social support did not moderate relationships between discrimination and the three mental health indicators (depressive symptoms, anger, and anxiety), as all interaction terms exceeded the p = .05 level. Additionally, sex did not moderate relationships between discrimination and mental health indicators (all p values > .05).

Simple slopes testing and directional impact of moderators

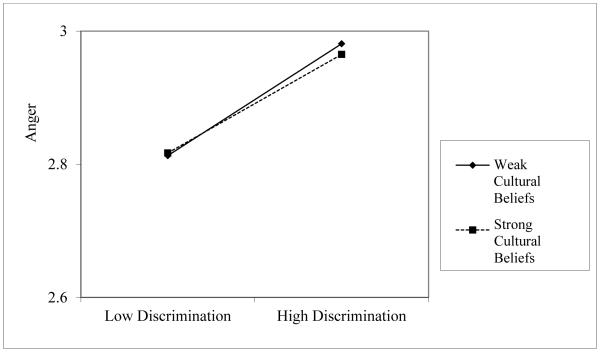

To perform simple slopes testing for the direction in which traditional cultural beliefs moderated the self-reported discrimination and anger pathway, two new variables were created. The “strong cultural beliefs” variable was created by shifting the traditional cultural beliefs scores one standard deviation (SD) below the mean and the “weak cultural beliefs” variable was created by shifting traditional cultural beliefs scores one SD above the mean given the reverse coding scheme. Then, two interaction terms were created (discrimination X strong cultural beliefs; discrimination X weak cultural beliefs) and included in two separate single-step regression models to test for moderation effects on the discrimination and anger pathway by strong versus weak traditional cultural beliefs.

As demonstrated in Figure 1, the pathway between discrimination and anger pathway was less harmful for those who had stronger cultural beliefs, B = .05 (.02), p = .01, in comparison to those who had weaker cultural beliefs, B = .11 (.02), p < .001. For those who actively coped with discrimination, the pathway between discrimination and anxiety was buffered, B = −.05 (.03), p = .04. Conversely, for those who passively coped with discrimination, the link between discrimination and anxiety was exacerbated, B = .05 (.03), p = .04 as presented in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Simple slopes analysis of traditional cultural beliefs moderating discrimination and anger pathway

Figure 2.

Simple slopes analysis of coping style moderating discrimination and anxiety pathway

Discussion

Despite having high educational and economic resources and relatively low levels of reported discrimination and mental distress, reports of discrimination appeared to adversely impact the mental health of AIs in this study. The first study hypothesis was confirmed, in that self-reported discrimination was positively related to depressive symptoms, anger, and anxiety when controlling for several demographic, acculturation-related, and social support-related factors. Our second hypothesis was partially supported, in that associations between self-reported discrimination and mental health were moderated by (2a) traditional cultural beliefs and (2c) coping style in the expected directions. Contrary to our hypothesis (2b), social support did not moderate associations between discrimination and mental health in this study.

Significance of cultural beliefs as a moderator

Although statistically significant, the simple slope beta for traditional cultural beliefs on the discrimination and anger pathway was notably small in value. In addition, the graphic depiction (Figure 1) of traditional cultural beliefs as a moderator demonstrate at best a minor difference between high and low levels on the discrimination and anger pathway. Therefore, the clinical significance of having strong versus weak traditional cultural beliefs on the pathway between discrimination and anger appears to be marginal in this study.

Although we temper findings based on the question of clinical significance, there may have been a protective effect for participants who had stronger traditional cultural beliefs in comparison to those who had weaker traditional cultural beliefs on the discrimination and anger pathway. Although ethnic identity is a different construct, the Mossakowski (2003) and Yoo & Lee (2008) studies demonstrated that a stronger ethnic identity was protective of discrimination and health pathways. Similarly, we hypothesized that having stronger traditional cultural beliefs, was a potential marker of a stronger group affiliation with the SA community, and would protect one from discrimination-related stress and its link with mental health. Thus, our findings suggest that perhaps those with stronger cultural beliefs may have additional resources or support systems (Hobfoll, 2001) that facilitate coping with discrimination-related stress. Alternatively, AIs who perhaps abandon or reject traditional SA cultural beliefs may become distanced from protective resources as they adopt the beliefs of mainstream US society. In sum, having stronger traditional cultural beliefs could potentially provide a support or coping structure that buffers experiences of discrimination.

Another explanation for current study findings may be that immigrants who have stronger traditional cultural beliefs may not perceive discriminatory behaviors when directed towards them. Conversely, AIs who have weaker traditional cultural beliefs may be more enmeshed in American society and therefore may perceive more discrimination. Finch, Kolody, & Vega’s 2000 study found that Latinos who had higher levels of acculturation (greater amount of time lived in the US, higher English language proficiency and educational status) reported higher levels of discrimination. Perhaps increasing involvement in US society and less affiliation with ones’ cultural beliefs lends to increased perceptions of discrimination. However, further discrimination, mental health, and moderation analyses among SAs are needed.

Lack of support for social support as moderator

In opposition to our hypothesis (2b), social support did not attenuate relationships between discrimination and mental health indicators. This finding was surprising, given the wide body of literature outlining the stress-buffering benefits of social support. However, our social support measure focused on general forms of support (feeling listened to, getting help when needed) and perhaps more specific types of support are needed. For example, Tummala-Narra et al. (2012) demonstrated that family support buffered discrimination and health pathways among SAs. In addition, scores from the social support measure in the current study were skewed reflecting high levels of social support. Therefore, the social support measure may not have a high enough degree of variability to detect a moderating effect. Therefore, to detect social support moderation effects in future studies, measurements that evaluate specific types and quality of support, as well as measures demonstrating an evenly distributed range of scores among respondents, may be needed.

Coping style as buffer

The second hypothesis (2c) was confirmed in that an active coping style buffered the relationship between discrimination and anxiety. These findings are consistent with previous studies (Krieger & Sidney, 1996; Noh & Kaspar, 2003). Therefore, active coping, such as talking about or reporting discrimination to authorities, may be health protective ways to manage experiences of discrimination.

Limitations, Strengths, and Implications

Study findings are limited by a cross-sectional study design and reverse causation issues. It may be the case that those who are afflicted with mental health problems perceive they are being treated unfairly or discriminated against more often. Generalizability of the study is limited to AIs who have high socioeconomic statuses, have lived in the United States for many years, and live in the Chicago and San Francisco areas. Two of the continuous measures fell slightly below a .7 α level as recommended by Tabachnick and Fidell (2007); the Spielberger Trait Anxiety Scale (α = .51) and the CES-D scale (α = .65). This is a recognized weakness in the study. The small effect sizes in the moderation analyses suggest further research is needed in evaluating potential moderators of discrimination and mental health pathways.

A major limitation of the current study is based on the assumption that those with stronger traditional cultural beliefs are not simultaneously developing strong beliefs and affiliations with mainstream American culture (Berry, 1979). According to Berry (1979), it is highly possible that Asian Indians who have strong traditional cultural beliefs may also strongly affiliate with dominant cultural beliefs in US society. Therefore, our conceptualization of traditional cultural beliefs is a significant limitation and likely oversimplifies complex acculturation-related processes (Berry, 1979). Improved measures of acculturation-related concepts in self-reported discrimination and health studies among SAs are needed.

Although there were several limiting factors in the current study, a notable strength of the study was that it is the first to examine self-reported discrimination, health, and moderating factors in a large AI cohort while using multidimensional and relatively reliable measures. Importantly, the current study disaggregated AIs as a unique SA group for analysis. Further, studies that have disaggregated Asian American subgroups for analyses had smaller sample sizes (Lam, 2007; Lee, 2005; Tummala-Narra, 2012). Findings of this study support that self-reported discrimination is related to several indicators of poorer mental health (depressive symptoms, anger, and anxiety) among AIs. Further, there may be ways to attenuate these links through perhaps maintaining traditional cultural beliefs, or stronger affiliations with the SA community, and active coping.

Additional research is needed to explore longitudinal effects of discrimination and mental health AIs over time. Future researchers may seek to identify robust coping moderators that have protective health effects on discrimination and mental health pathways among AIs. Lastly, clinicians and health professionals may acknowledge self-reported discrimination as potentially harmful to the mental health of AIs and can offer cultural sensitive care to AIs who may experience discrimination as a stressor (Frey & Roysircar, 2006).

Table 1.

Demographics of Sample (n=757*)

| Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 40-55 | 397 | 52.4 |

| 56-70 | 303 | 40.0 |

| 71-83 | 68 | 9.0 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 349 | 46.1 |

| Male | 408 | 53.9 |

| Education | ||

| Bachelor’s or higher | 711 | 93.9 |

| Less than Bachelor’s | 46 | 6.1 |

| Income per year | ||

| <$39,999 | 84 | 11.1 |

| $40,000-$74,999 | 93 | 12.3 |

| $75,000-$99,999 | 72 | 9.5 |

| >$100,000 | 484 | 63.9 |

| Study site | ||

| Chicago | 339 | 44.8 |

| San Francisco | 418 | 55.2 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married | 697 | 92.1 |

| Unmarried | 60 | 7.9 |

| Years in US | ||

| 3-17 | 155 | 20.5 |

| 18-32 | 348 | 46.0 |

| 33-46 | 235 | 31.0 |

| 47-58 | 19 | 2.5 |

Note: N = 733 for income variable

Acknowledgments

The MASALA study was supported by the NIH grant The MASALA study was supported by the NIH grant #1RO1 HL093009. Data collection at UCSF was also supported by NIH/NCRR USCF-CTSI Grant Number UL1RR024131. This research was also funded by The National, Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number T32HL069771. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Health.

We would like to acknowledge Peter John De Chavez of Northwestern University’s Department of Preventive Medicine and Carlos Salas of the University of Illinois at Chicago for their contribution of statistical consultation.

Contributor Information

Sarah B. Nadimpalli, Northwestern University’s Department of Preventive Medicine (work performed here).

Alka M. Kanaya, Northwestern Departments of Preventive Medicine and General Internal Medicine.

Thomas W. McDade, Northwestern University, Department of Anthropology.

Namratha R. Kandula, University of California at San Francisco; The Division of General Internal Medicine.

References

- Alegria M, Takeuchi D. National Latino and Asian American Study (NLAAS), 2002-2003. 2009 Retrieved from http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/ICPSR/studies/00191.

- Barnes LL, Mendes de Leon CF, Lewis TT, Bienias JL, Wilson RS, Evans DA. Perceived discrimination and mortality in a population-based study of older adults. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98:1241–1247. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.114397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beasley M, Thompson T, Davidson J. Resilience in response to life stress: the effects of coping style and cognitive hardiness. Personality and Individual Differences. 2003;34:77–95. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. Research in multicultural societies: Implications of cross-cultural methods. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 1979;10:415–434. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. Acculturation: Living successfully in two cultures. 2005;29:697–712. [Google Scholar]

- California Health Interview Survey. UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; Los Angeles, CA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Chan S. Asian Americans: An interpretive history. 1st Twayne Publishing; Boston, MA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekhart CA. Flying while brown: Federal civil rights remedies to post-9/11 airline racial profiling of South Asians. Asian Law Journal. 2003;10:215–252. [Google Scholar]

- Chen TY. Hate violence as border patrol: An Asian American theory of hate violence. Asian Law Journal. 2000;7:69. [Google Scholar]

- Das AK, Kemp SF. Between two worlds: Counseling South Asian Americans. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development. 1997;25:23–33. [Google Scholar]

- ENRICHD Investigators Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease Patients (ENRICHD): Study design and methods. American Heart Journal. 2000;139:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(00)90301-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch B, Kolody B, Vega W. Perceived discrimination and depression among Mexican-origin adults in California. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2000;41:295–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch BK, Vega WA. Acculturation stress, social support, and self-rated health among Latinos in California. Journal of Immigrant Health. 2003;5:109–117. doi: 10.1023/a:1023987717921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey LL, Roysircar G. South Asian and East Asian international students’ perceived prejudice, acculturation, and frequency of help resource utilization. Multicultural Counseling and Development. 2006;34:208–222. [Google Scholar]

- Gee GC. A multilevel analysis of the relationship between institutional and individual racial discrimination and health status. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:615–623. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.4.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee G, Chen J, Spencer M, See S, Kuester O, Tran D, Takeuchi D. Social support as a buffer for perceived unfair treatment among Filipino Americans: Differences between San Francisco and Honolulu. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:677–684. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.060442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee GC, Spencer MS, Chen J, Takeuchi D. A nationwide study of discrimination and chronic health conditions among Asian Americans. The American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:1275–1282. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.091827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee GC, Ro A, Gavin A, Takeuchi DT. Disentangling the effects of racial and weight discrimination on body mass index and obesity among Asian Americans. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98:493–500. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.114025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee GC, Ro A, Shariff-Marco S, Chae D. Racial discrimination and health among Asian Americans: Evidence, assessment, and directions for future research. Epidemiological Review. 2009;31:130–151. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxp009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez E. The “dotbuster” attacks: Hate crime against Asian Indians in Jersey City, New Jersey. Middle States Geographer. 1996:30–38. [Google Scholar]

- Hahm CH, Ozonoff A, Gaumond J, Sue S. Perceived discrimination and health indicators: A gender comparison among Asian-Americans nationwide. Women's Health Issues. 2010;20:350–358. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess GR. The forgotten Asian Americans: The East Indian community in the United States. Pacific Historical Review. 1974;43:576–596. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE. The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. International Association for Applied Psychology. 2001;50:337–421. [Google Scholar]

- Kanaya AM, Kandula N, Herrington D, Budoff MJ, Hulley S, Vittinghoff E, Liu K. Mediators of Atherosclerosis in South Asians Living in America (MASALA) Study: Objectives, methods, and cohort description. Clinical Cardiology. 2013;36:713–720. doi: 10.1002/clc.22219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanaya AM, Ewing SK, Vittinghoff E, Herrington D, Tegeler C, Mills C, Kandula NR. Acculturation and subclinical atherosclerosis among U.S. South Asians: Findings from the MASALA study. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Research in Cardiology. 2014;1:1–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N, Sidney S. Racial discrimination and blood pressure: The CARDIA study of young black and white adults. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86:1370–1378. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.10.1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon H, Au W. Model minority myth. In: Chen EW, Yoo GJ, editors. Encyclopedia of Asian American issues today. ABC-CLIO, LLC; Santa Barbara, CA: 2010. pp. 221–230. [Google Scholar]

- LaFromboise T, Coleman HLK, Gerton J. Psychological impact of biculturalism: Evidence and theory. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114:395–412. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.3.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam BT. Impact of perceived racial discrimination and collective self-esteem on psychological distress among Vietnamese-American college students: Sense of coherence as mediator. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2007;77:370–376. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.77.3.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landrine H, Klonoff EA. The Schedule of Racist Events: a measure of racial discrimination and a study of its negative physical and mental health consequences. Journal of Black Psychology. 1996;22:144–168. [Google Scholar]

- Lee R. Resilience against discrimination: Ethnic identity and other-group orientation as protective factors for Korean Americans. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2005;52:36–44. [Google Scholar]

- Liang CTH, Alvarez AN, Juang LP, Liang MX. The role of coping in the relationship between perceived racism and racism-related stress for Asian Americans: Gender differences. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2007;54:132–141. [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS. Protection and damage from acute and chronic stress, allostasis, and allostatic load overload and relevance to the pathophysiology of psychiatric disorders. Annals of the New York Academy of Science. 2004;1032:1–7. doi: 10.1196/annals.1314.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossakowski KN. Coping with perceived discrimination: Does ethnic identity protect mental health? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003;44:318–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noh S, Kaspar V. Perceived discrimination and depression: Moderating effects of coping, acculturation, and ethnic support. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:232–238. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradies Y. A systematic review of empirical research on self-reported racism and health. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2006;35:888–901. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measure. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- South Asian American Leaders of Tomorrow American backlash: Terrorists bring war home in more ways than one. 2001 Retrieved from http://www.saalt.org/attachments/1/American%20Backlash%20report.pdf.

- South Asian American Leaders of Tomorrow Demographic characteristics of South Asians in the United States: Emphasis on poverty, gender, language ability, and immigration status. 2012 Retrieved from http://saalt.electricembers.net/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/Demographic-Characteristics-of-SA-in-US-20001.pdf.

- Spielberger CD. Preliminary Manual for the State-Trait Anger Scale (STAS) Consulting Psychologists Press, Inc; Palo Alto, CA: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 5th Allyn and Bacon; New York, NY: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tummala-Narra P, Alegria M, Chen C. Perceived discrimination, acculturative stress, and depression among South Asians: Mixed findings. Asian American Journal of Psychology. 2012;3:3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Uchino BN, Cacioppo JT, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. The relationship between social support and physiological processes: A review with emphasis on underlying mechanisms and implications for health. Psychological Bulletin. 1996;119:488–531. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.119.3.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau Population groups summary file 1. 2010 Retrieved from http://2010.census.gov/news/press-kits/summary-file-1.html.

- Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson JS, Anderson NB. Racial differences in physical and mental health: Socio-economic status, stress, and discrimination. Journal of Health Psychology. 1997;2:335–351. doi: 10.1177/135910539700200305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: evidence and needed research. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;32:20–47. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip T, Gee GC, Takeuchi DT. Racial discrimination and psychological distress: The impact of ethnic identity and age among immigrant and United States-born Asian adults. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:787–800. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.3.787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo HC, Lee RM. Ethnic identity and approach-type coping as moderators of the racial discrimination/well-being relation in Asian Americans. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2005;52:497–506. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo HC, Lee RM. Does ethnic identity buffer or exacerbate the effects of frequent racial discrimination on situational well-being of Asian Americans? Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2008;55:63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo HC, Gee GC, Takeuchi D. Discrimination and health among Asian American immigrants: Disentangling racial from language discrimination. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;68:726–732. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshihama M, Bybee D, Blazevski J. Day-to-day discrimination and health among Asian Indians: A population-based study of Gujarati men and women in Metropolitan Detroit. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2012:471–483. doi: 10.1007/s10865-011-9375-z. doi:10.1007/s10865-011-9375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa H, Wilson PAD, Chae DH, Cheng F. Do family and friendship networks protect against the influence of discrimination on mental health and HIV risk among Asian and Pacific Islander gay men? AIDS Education and Prevention. 2004;16:84–100. doi: 10.1521/aeap.16.1.84.27719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]