Abstract

Objective: The impact of providing nursing staff access to data collected through a medication dose tracking technology (MDTT) web portal was investigated.

Methods: A quasi-experimental, nonrandomized, pre-post intervention study was conducted in the Cardiothoracic Intensive Care Unit (CTICU) at Duke University Hospital. The change in the number of medication requests per dispense routed to the pharmacy electronic health record (EHR) in-basket was analyzed pre and post web portal access. Other endpoints included the number of MDTT web portal queries per day by nursing staff, change in nursing satisfaction survey scores, and technician time associated with processing medication requests pre and post web portal access. The pre web portal access phase of the study occurred from June 1, 2014 to August 31, 2014. The post web portal access phase occurred from October 1, 2014 to December 31, 2014.

Results: An 11.4% decrease in the number of medication requests per dispense was exhibited between the pre and post web portal access phases of the study (0.0579 vs 0.0513, respectively; p < .001). Pre and post surveys showed a significant improvement in nurses' satisfaction regarding access to information on the location of medications (p = .009). Additionally, CTICU nursing staff utilized the MDTT web portal for 3.21 queries per day from October 1, 2014 to December 31, 2014.

Conclusion: Providing nurses access to data collected via an MDTT decreased the number of communications between nursing and pharmacy staff regarding medication availability and led to statistically significant improvements in nursing satisfaction for certain aspects of the medication distribution process.

Keywords: dose tracking, medication systems, missing doses, nurses, pharmacists, quality assurance, technology

Medication dose tracking technology (MDTT), which allows for identification of medication location subsequent to dispensing, has been utilized to improve pharmacy delivery processes and performance.1 PharmTrac.PD (Plus Delta Technologies, Durham, NC) is one example of MDTT. This mobile tool offers barcode-enabled medication tracking and collects data via a web-based portal viewable by authorized staff members.1

Duke University Hospital (DUH) utilizes the Epic electronic health record (EHR) (Epic Corporation, Madison, WI). This EHR allows for the use of an in-basket message queue for communication among nurses, pharmacists, pharmacy technicians, and other health care professionals. In-basket messaging provides nursing staff with the ability to send typewritten messages to pharmacy staff through the EHR and is the primary method of communication regarding medication requests at DUH. Medication requests are directed to a dedicated pharmacy technician message queue for review and follow-up. Pharmacy staff respond to a high volume of nurse-generated messages on a daily basis, with a mean of 526 in-basket medication requests per day for June 2014. During the same time period, approximately 60% of in-basket medication requests at DUH were due to missing medications. Missing medications are a major nursing dissatisfier, and they often result in costly redispenses, increased waste, consumption of human resources, and adverse events related to delays in medication delivery.1,2 In response to this, DUH implemented an MDTT. Prior to implementation of this technology, DUH was limited in its ability to determine the location of a medication in the distributive process. Pharmacists and technicians now generate data by scanning intravenous preparations and oral syringes at multiple locations from pick-up to delivery.1

Published evidence regarding MDTT is limited to the area of medication distribution process improvement.3,4 One published report described the use of MDTT in a large academic medical center to identify areas of delay in its processes.3 They were able to make targeted adjustments resulting in a reduction in mean medication turnaround time from 74 to 66 minutes.3 In contrast, the objectives of our study included the following: to investigate whether nursing access to MDTT impacts the frequency of nursing communications to pharmacy staff related to missing doses, to quantify pharmacy labor costs associated with processing of technician in-basket medication requests, and to evaluate changes in nursing satisfaction. This study seeks to fill a void in the current literature by evaluating the impact of providing nurses with access to an MDTT web portal.

METHODS

Subjects

This was a quasi-experimental, nonrandomized, pre-post intervention study at DUH, a 957-bed academic, quaternary, acute care medical center.5 Nursing units eligible to receive the intervention were identified based on volume of in-basket messages during the pre web portal access phase. Patient care areas with the highest volume of in-basket messages generated and high utilization of intravenous preparations or oral syringes were preferred. The emergency department was excluded due to the disproportionately high volume of STAT medications dispensed to this area. Based on these criteria, the DUH Cardiothoracic Intensive Care Unit (CTICU) was selected. This unit was the greatest generator of in-basket medication request volume at DUH during the pre web portal access phase of the study. This study was granted exempt status by the DUH institutional review board.

Procedures

Prior to study initiation, an extensive PubMed search was performed to identify literature concerning MDTT and other similar technologies. The CTICU was subsequently identified to receive the study intervention. The pre web portal access phase of the study occurred from June 1, 2014 to August 31, 2014. MDTT web portal access for nurses was provided on September 23, 2014. This allowed nursing staff to gain comfort with the system before initiation of the postaccess study period, which occurred from October 1, 2014 to December 31, 2014. Before MDTT web portal access was granted to the CTICU nursing staff, orientation and training to the system was given during mandatory, scheduled staff meetings. Staff meetings also provided an opportunity to encourage MDTT web portal utilization and survey participation. Attendee sign-in was employed to track the number of orientees. Additionally, 3 nurse super users were identified to receive advanced training for peer support within the CTICU. Training brochures were provided to nurses at access go-live. Brochures contained information about gaining access for the first time, determining the location of a medication, and contact information for MDTT support. MDTT support was provided by the primary study investigator through a 24/7 on-call pager.

A primary endpoint selected to measure the overall impact was the number of medication requests per dispense routed to the pharmacy in-basket pre and post implementation of MDTT web portal access. The number of medication requests were normalized to the total number of dispenses to the CTICU to account for expected seasonal changes in hospital volumes.6 Secondary endpoints included the change in nursing satisfaction survey scores pre and post web portal access, number of MDTT queries per day by nursing staff, and technician time associated with processing of medication requests pre and post web portal access.

Nursing satisfaction due to MDTT access was measured through pre and post web portal access surveys. The preaccess survey occurred in early September 2014, and the postaccess survey was distributed in January 2015. Postaccess survey respondents were required to have participated in the preaccess survey to allow for paired statistical analysis.

Data Collection

Primary endpoint data, the number of medication requests per dispense routed to the pharmacy inbasket pre and post implementation of MDTT web portal access, were collected utilizing EHR reporting. Nursing satisfaction survey scores were analyzed through a modified version of the validated Medication Administration System-Nurses Assessment of Satisfaction (MAS-NAS) scale.7,8 The 12 modified MAS-NAS items were scored on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = somewhat disagree, 4 = somewhat agree, 5 = agree, 6 = strongly agree).

Survey data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools.9 REDCap compiled de-identified survey responses for pre and post web portal access allowing for paired sample statistical analysis. The total number of queries per day by nursing staff was collected through MDTT web portal reporting. Finally, technician time associated with processing of medication requests pre and post web portal access was determined by analyzing time from in-basket message creation to a status change of “done,” indicating completion of the request. Change in processing time was then translated to pharmacy cost savings according to the US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, mean pay rate for hospital pharmacy technicians.10

Statistical Tests

The primary analysis of medication requests per dispense pre and post MDTT web portal access was assessed using a z-test of proportions. Descriptive statistics were tabulated for analysis of the mean number of MDTT web portal queries per day and median time associated with processing of medication requests by pharmacy technicians.

Analysis of pre and post modified MAS-NAS survey responses enabled us to understand the utility of MDTT web portal access for nursing staff. Summary statistics, which include response rate, mean and standard deviation, were used to describe satisfaction scale scores. A Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare responses between the pre and post MDTT web portal survey responses. Significance of statistical tests in our study were examined using α = 0.05. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

The CTICU at DUH was responsible for a total of 3,529 medication requests, or 38.4 medication requests per day, during the pre web portal access phase of the study. Orientation to the MDTT and web portal occurred during the CTICU nursing staff meetings in August 2014, whereby a total of 96 nurses were oriented during 12 scheduled meetings. Subsequently, 166 registered nurses were granted access to the MDTT web portal for the postaccess phase of the study.

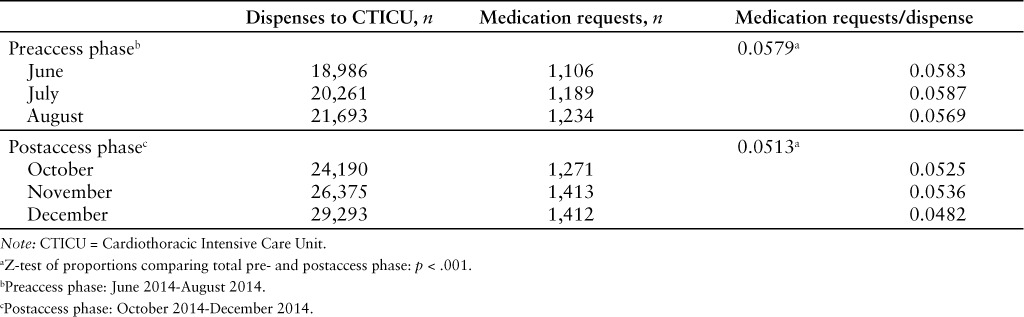

Primary endpoint results are represented in Table 1. The number of medication requests per dispense to the CTICU for the pre web portal access and post web portal access phases were 0.0579 and 0.0513, respectively (p < .001). This was a statistically significant decrease of 11.4%, resulting in an avoidance of 527 in-basket medication requests during the post MDTT web portal access phase.

Table 1.

Primary outcome of number of medication requests per dispense pre and post web portal access

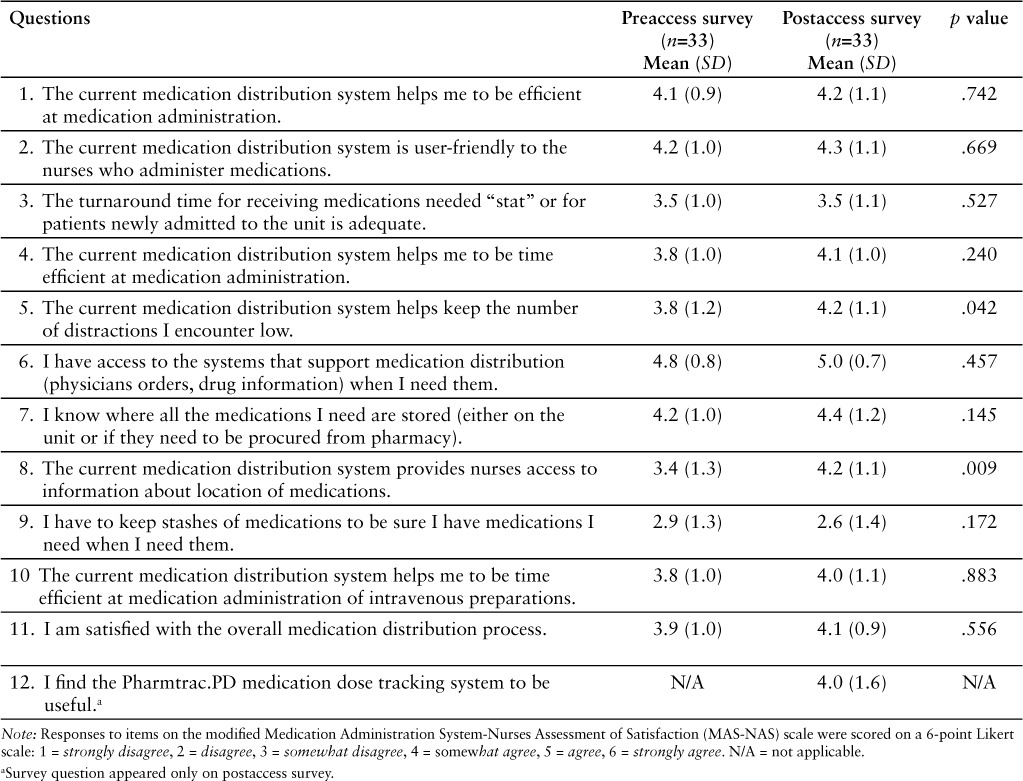

Results of the modified MAS-NAS survey for pre and post MDTT web portal access are represented in Table 2. A total of 166 nurses were provided MDTT web portal access with 59 (35%) respondents to the preaccess survey. These respondents were then eligible to participate in the post web portal access survey. Results of the post web portal access survey represent 33 respondents or a response rate of 56%. Statistically significant improvement in nurses' satisfaction exists for 2 of the 11 pre-post MAS-NAS survey items. Nurses' satisfaction regarding access to information about location of medications increased after they received access to the MDTT web portal (pre = 4.1 and post = 4.4; p = .009). Nurses also experienced increased satisfaction with the number of distractions in the medication distribution system after receiving MDTT web portal access (pre = 3.8 and post = 4.2; p = .042). The remaining 9 pre-post survey questions showed increased or stable nurse satisfaction; however, for these items, the intervention did not result in statistically significant differences between the pre- and postaccess phases. Item 12 was present only in the postaccess survey and measured nurses' satisfaction with the MDTT system's usefulness. The response to this item showed a mean value of 4 (SD = 1.6), signifying nurses “somewhat agree” that the system is useful overall.

Table 2.

Modified MAS-NAS survey results

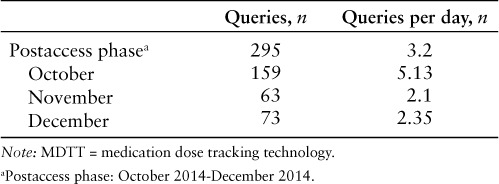

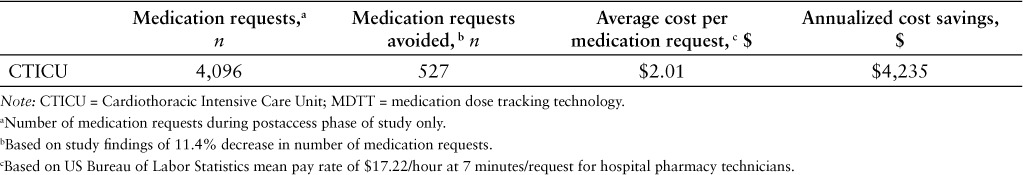

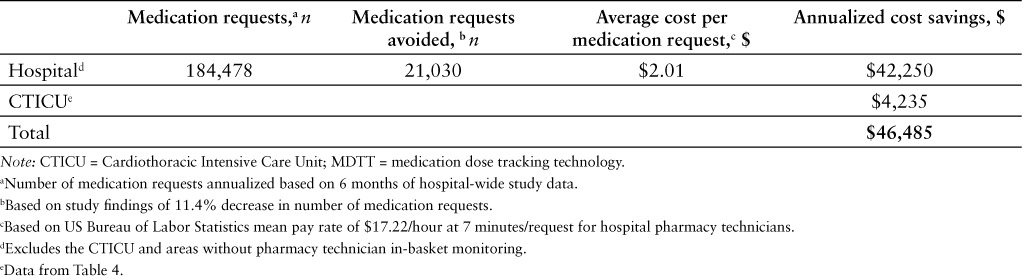

During the postaccess study period, 295 queries, or 3.2 queries per day, were performed by 68 unique CTICU nursing staff members (Table 3). The processing time of in-basket medication requests by pharmacy technicians was measured throughout the pre and post MDTT web portal access phases of the study and resulted in a median time of 7 minutes per medication request. After applying a mean pay rate of $17.22 per hour for hospital pharmacy technicians, the resultant cost of processing a medication request by pharmacy technician resource time was calculated to be $2.01 per request.10 Pharmacy cost savings estimates are represented in Tables 4 and 5. Total pharmacy cost savings during the post web portal access phase due to pharmacy technician resource time was $1,059, with a potential annualized savings of $4,235 for the CTICU alone. Furthermore, we applied the results of this study to calculate pharmacy cost savings if hospital-wide nursing access to the MDTT web portal were provided, indicating a potential savings of $46,485 per year.

Table 3.

Nursing utilization of the MDTT web portal

Table 4.

Pharmacy cost savings associated with CTICU nursing access to the MDTT web portal during postaccess phase

Table 5.

Potential annualized pharmacy cost savings associated with hospital - wide nursing access to the MDTT web portal

DISCUSSION

The findings from this study suggest that nurses' access to an MDTT web portal leads to a significant decrease in the frequency of communications received by pharmacy staff. MDTT web portal access also led to moderate improvements in nursing satisfaction, as measured by modified MAS-NAS pre-and postaccess surveys. Two survey items reached the level of statistically significant improvement in satisfaction. These survey items were the following: “The current medication distribution system helps keep the number of distractions I encounter low,” and “The current medication distribution system provides nurses access to information about location of medications.” CTICU nurses utilized the MDTT web portal multiple times each day, and cost savings due to a decrease in pharmacy technician processing time of medication requests were apparent. Based on study findings, pharmacy cost savings could be much greater if the same results were able to be realized hospital-wide.

The decrease in frequency of in-basket medication requests is a key indicator of the impact of MDTT web portal access on nursing practice. By providing access to the MDTT web portal, nursing staff were empowered to determine the location of their patients' intravenous and oral syringe doses. Study investigators set an a priori goal decrease of 10% in the frequency of medication requests per dispense. This decrease was achieved in the current study. It is also important to note that the number of in-basket medication requests is normalized to the number of doses dispensed to the CTICU. This allowed study investigators to account for seasonal changes in drug volume, with the assumption that an increased number of dispenses would lead to an increased number of medication requests. Additionally, modified MAS-NAS survey results and participation were positive. The pre modified MAS-NAS survey was distributed subsequent to staff meeting training and orientation, but prior to nurses receiving individual access to the MDTT web portal. This timeline was followed in order to increase overall survey participation, while also minimizing bias for survey respondents. Nearly all survey items showed improvements between the pre and post responses. The 2 survey items that achieved statistically significant improvements offer confirmatory evidence regarding the ability of the MDTT system to streamline the medication distribution process and to provide increased transparency regarding the location of medications. Overall, nurses offered positive responses regarding the usefulness of the MDTT system. Frequency of use, and the number of unique users, was lower than expected. Study investigators believe this to be multifactorial. It is speculated that overall satisfaction and use of the system could have been improved if the MDTT system were more accessible within the EHR. At the time of the study, the MDTT web portal link was not located at a convenient location within the EHR. Instead, nurses had to locate the web portal shortcut manually within their computer Start Menus. There was also a high amount of CTICU nursing staff turnover during the postaccess study period, making awareness of the MDTT system difficult to maintain. Pharmacy cost savings associated with nursing access to the MDTT web portal during the postaccess study period were evident; however, the potential pharmacy cost savings for institution-wide implementation of MDTT web portal access could be even higher. Cost savings were calculated utilizing the median processing time per in-basket medication request by pharmacy technicians. The median, instead of mean, was used to censor for outliers in processing time. It is also important to note that cost savings as calculated in the current study do not include other expenses such as drug cost or nurse or pharmacist time associated with medication requests. Implementation cost due to expansion of MDTT web portal access to all nurses was not included in the current evaluation, as there are no incremental expenses associated with providing access to additional users. Due to the aforementioned factors, it is expected that the true savings associated with MDTT would be much greater.

The results of our study correspond with the positive impact evidenced by MDTT in other publications. One publication used MDTT to improve medication distribution turnaround time.3 Utilizing MDTT, the investigators were able to capture a higher volume of location and time points, allowing for more thorough analysis into potential hindrances along the medication distribution process.3 The result of MDTT implementation and subsequent workflow changes led to a decrease in the mean turnaround time from 74 to 66 minutes for the study site's central pharmacy.3 The same study site had not implemented nursing access to the MDTT web portal at the time of publication; however, it was reported that plans were in place to allow for future access.3 In contrast, our study accomplished the goal of allowing nursing access to the MDTT web portal and provides detailed analysis regarding its impact. Survey data in our study were collected utilizing a modified version of the validated MAS-NAS scale.7 Other studies have successfully assessed nursing satisfaction with changes in the medication distribution process through standard and modified versions of the MAS-NAS survey.8,11 A study assessing nursing satisfaction after the addition of medication cabinets in patients' rooms used a similar method to our study through the introduction of survey items during the postimplementation phase only.8 Although pre and post analysis could not occur, this method allowed the authors to fully assess the impact of changes made in the medication distribution process.8

Providing MDTT web portal access allowed nurses to gain a better understanding of the location of their medications without the need to contact pharmacy staff. Although not an endpoint in the current study, this more efficient process could lead to an increase in medication availability and subsequent decrease in medication delays. Likewise, a decrease in communications with pharmacy staff has a positive impact on overall interruptions and distractions encountered in the preparation and dispensation of medications. This is particularly important because previously published studies have directly linked interruptions and distractions with medication dispensing errors.12,13

There are several limitations to our study. Results relied heavily on participation by the nursing staff in the CTICU. This patient care area experienced a high volume of turnover during the post web portal access phase, which could have negatively impacted frequency of use of the system. The high volume of turnover also resulted in many new nurses gaining access to the system without completing the initial training and orientation offered during required staff meetings. Fortunately, additional methods were provided to overcome this limitation, including training brochures and peer super user support. Additionally, the primary endpoint of the study was normalized to the total number of medications dispensed to the CTICU during the study period.

Although not a definite limitation of the study, it should be recognized that normalizing to total number of dispenses assumes the presence of a linear relationship between the number of medications dispensed and volume of in-basket medication requests. Certain potentially important endpoints were not measured in the current study. The impact of MDTT web portal access on medication delays or the number of redispensed medications was not analyzed. Pharmacy staff satisfaction was not assessed, and investigators did not include medication expense or nurse or pharmacist salaries in projections of potential cost savings. Furthermore, the CTICU was responsible for generating the highest volume of in-basket messages at DUH during the pre web portal access phase of the study; therefore, extrapolating study results has the potential to overestimate the hospital-wide benefit of MDTT. Similarly, the current MDTT system at DUH only tracks intravenous and oral syringe preparations. Patient care areas with lower volumes of these preparation types may not experience the same level of benefit as evidenced in our study.

CONCLUSION

The results of this study suggest that providing nurses access to an MDTT web portal decreased the number of communications regarding location of medications between nursing and pharmacy staff and led to statistically significant improvements in nursing satisfaction for certain aspects of the medication distribution process. Our study represents the first publication concerning the impact of MDTT web portal access on nursing practice. Further research should consider evaluating the impact of MDTT on volume of redispensed medications, satisfaction of pharmacy staff, and reduction in adverse events related to medication delays.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Duke University Hospital CTICU nursing leadership, Mary Lindsay, RN, MSN, and Kelly Kester, RN, BSN, for extensive collaboration throughout the study. Support with survey design and administration was provided by nurse research scientist, Julie Aucoin, DNS, RN. Additionally, statistical support was provided by Maragatha Kuchibhatla, PhD. At the time of writing, Dr. Peek was a PGY2 in Health-System Pharmacy Administration at Duke University Hospital. The study was funded by the Duke University Hospital Department of Pharmacy. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

*Coordinator, 340B Administration and Revenue Management, Duke University Hospital, Durham, North Carolina.

†Associate Chief Pharmacy Officer, Inpatient Operations, Duke University Hospital, Durham, North Carolina.

‡Manager, Unit Dose Distribution, Department of Pharmacy, Duke University Hospital, Durham, North Carolina.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chou J, Peaty N, Strickland JM. Measuring, evaluating, and improving medication distribution process and performance metrics in an inpatient pharmacy: The value of medication tracking, on-time delivery, and pharmacy analytics. http://www.plusdeltatech.com/d/PharmTrac%20Performance%20Monitoring%20White%20Paper%202013%203.1.2013.pdf. Accessed August 5, 2014.

- 2.Agency for Health Care Research and Quality Medication turnaround time in the inpatient setting. AHRQ Publication No: 09-0045. 2009.

- 3.Calabrese SV, Williams JP. Implementation of a web-based medication tracking system in a large academic medical center. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2012;69:1651–1658. doi: 10.2146/ajhp110527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lochbihler K, Williams J. Implementing dose tracking technology. Pharm Purchasing Products. 2011;8(7):1. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harris AD, McGregor JC, Perencevich EN et al. The use and interpretation of quasi-experimental studies in medical informatics. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2006;13:16–23. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fullerton KJ, Crawford VL. The winter bed crisis – quantifying seasonal effects on hospital bed usage. Q J Med. 1999;92:199–206. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/92.4.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hurley AC, Lancaster D, Hayes J et al. The medication administration system-nurses assessment of satisfaction (MAS-NAS) scale. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2006;38(3):298–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2006.00117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arinal MF, Cohn T, Avila-Quintana C. Evaluating the impact of medication cabinets in patients' rooms on a medical-surgical telemetry unit. Medsurg Nurs. 2014;23(2):77–83. 119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.United States Bureau of Labor Statistics Occupational employment and wages [Internet] 29-2052 Pharmacy Technicians; May 2014. http://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes292052.htm.

- 11.Fowler SB, Sohler P, Zarillo DF. Bar-code technology for medication administration: Medication errors and nurse satisfaction. Medsurg Nurs. 2009;18(2):103–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flynn EA, Barker KN, Gibson JT et al. Impact of interruptions and distractions on dispensing errors in an ambulatory care pharmacy. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1999;56:1319–1325. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/56.13.1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beso A, Franklin BD, Barber N. The frequency and potential causes of dispensing errors in a hospital pharmacy. Pharm World Sci. 2005;27(3):182–190. doi: 10.1007/s11096-004-2270-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]