Abstract

Objective

Belimumab (Benlysta) is a human monoclonal antibody that inhibits soluble B-lymphocyte stimulator and was approved by the FDA for treatment of adults with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). This study evaluates the use and efficacy of belimumab in academic SLE practices.

Methods

Invitations to participate and complete a one-page questionnaire for each patient prescribed belimumab were sent to 16 physicians experienced in SLE Phase III clinical trials. The outcome was defined as the physician’s impression of improvement in the initial manifestation(s) being treated without worsening in other organ systems.

Results

Of 195 patients treated with belimumab at 10 academic centers, 96% were on background medications for SLE at initiation of belimumab, with 74% on corticosteroids. The main indications for initiation of belimumab were arthritis, rash, and/or worsening serologic activity, with 30% of patients unable to taper corticosteroids. Of the 120 patients on belimumab for at least 6 months, 51% responded clinically and 67% had ≥25% improvement in laboratory values. While numbers are limited, black patients showed improvement at 6 months. In a subset of 39 patients with childhood-onset SLE, 65% responded favorably at 6 months, and 35% discontinued corticosteroids.

Conclusion

Our data demonstrate favorable clinical and laboratory outcomes in patients with SLE at 6 months across all racial and ethnic groups, with similar improvement seen among patients with childhood-onset SLE.

Keywords: belimumab, lupus treatment, childhood-onset lupus

INTRODUCTION

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic, multi-system, autoimmune disease of unknown etiology with a heterogeneous range of clinical and serological manifestations. Adding to the complexity of SLE is the unpredictability of flares, or periods of increased inflammatory disease activity, as well as the accrual of organ damage (1, 2). “Standard of care” therapy for SLE includes antimalarials, corticosteroids, immunosuppressives, and cytotoxic agents. These treatments often result in undesired long-term adverse effects and organ damage that are unavoidable due to the essential role of these medications in SLE treatment.

Although the etiology of SLE remains largely unknown, an increased understanding of its immunopathogenesis, in particular, B cell-specific mechanisms, has allowed for a focus on targeted immunotherapy. This led to the development and testing of belimumab (Benlysta®) for SLE and subsequent approval in 2011 by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of adults with active SLE (3). Belimumab is a fully-human, recombinant inhibitor of soluble B lymphocyte stimulator (BLyS) and neutralizes a key cytokine that plays a major role in B cell differentiation, proliferation, and survival (4–6). Two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multi-center Phase III trials (BLISS-52 and BLISS-76) demonstrated improvement in disease activity in patients treated with belimumab and standard of care SLE therapy compared to those treated with placebo and standard therapy alone (7, 8).

Since the initial belimumab clinical trials, the post-approval clinical experience of patients receiving belimumab at 10mg/kg/dose every 4 weeks along with standard SLE therapy as well as the practice patterns of academic physicians in clinical settings has received increased attention. In addition, the data are scarce on the use of belimumab in patients with childhood-onset SLE. Childhood-onset is diagnosed prior to the patient’s 18th birthday and accounts for up to 20% of all SLE patients (9). When compared to adult-onset SLE, childhood-onset SLE has increased disease activity, morbidity, and mortality, often requiring earlier and more aggressive treatment with immunosuppressive medications for disease control (10–16).

Due to the multitude of challenging characteristics of successful trials, including identifying meaningful outcomes and appropriate patient populations, post-marketing observational studies are often useful in providing supplementary information to trials. The objective of this multi-center study was to analyze the experience with belimumab in academic clinical practices.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design

This is a prospective, multicenter, observational study conducted in 10 large academic SLE clinical practices, 9 of whom were in the United States. Approvals to conduct this study were obtained from the Institutional Review Boards of the respective institutions. Sixteen adult rheumatologists experienced in Phase III SLE clinical trials were invited to participate, 10 of whom accepted the invitation and completed repeat assessments of SLE patients treated with belimumab as part of their standard of care. Assessments consisted of a single-page questionnaire per patient completed every three months. All investigators who agreed to participate were located in countries where belimumab has received regulatory agency approval (United States and Sweden).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All patients were required to have a diagnosis of SLE, have met at least 4 of 11 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) or Systemic Lupus International Collaborative Clinics (SLICC) classification criteria (17, 18), and have started treatment with belimumab after approval by regulatory agencies. Exclusion criteria included patients who had previously participated in the belimumab clinical trials, and those who met fewer than 4 ACR classification criteria. We also excluded patients from this study who had severe renal or neuropsychiatric involvement.

Questionnaire

The single-page questionnaire included basic demographic information (e.g., age, sex, race/ethnicity), SLE data (including disease duration, year of diagnosis, serologies, clinical manifestation(s) of lupus, and concomitant medications), and belimumab information (including start date, clinical response, laboratory response, side effects, and reasons for discontinuation of belimumab). The questionnaires were completed every three months by the treating physician to capture long-term clinical patterns of belimumab.

Outcomes

All investigators adhered to the guidelines for 50% improvement as defined by the Responder Index for Lupus Erythematosus (RIFLE) and British Isles Lupus Assessment Group (BILAG), including clinical improvement and at least intent to decrease therapy (19, 20) without worsening in any organ systems. This was further defined as the treating physician’s impression of a ≥50% improvement in the initial manifestation(s) being treated and the ability to taper existing steroid dose by at least 25% of the initial dose for those patients who were on steroids at initiation of belimumab. Anti-dsDNA positivity was defined as having an anti-dsDNA level above the normal range at the local laboratory; similarly, low complement was defined as having a C3 and/or C4 level below the normal range at the local laboratory. Laboratory response was defined as a ≥25% improvement in the levels of C3, C4, and/or a 25% decrease in anti-dsDNA antibody levels. Responders were those patients who achieved the outcome measures as defined above; non-responders were those who did not. Moreover, to be classified as a responder, there could be no worsening in other organ systems.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to evaluate the baseline characteristics of enrolled patients using Graphpad Prism 6 (La Jolla, CA). Every three months, clinical and laboratory response data were evaluated using t-tests and chi-square tests where appropriate.

RESULTS

Demographics

A total of 195 SLE patients treated with belimumab were enrolled, most of whom were female (Table 1), with 29% black and 11% Hispanic. The average disease duration at initiation of belimumab was 11.9 ± 8.1 years among the 151 patients with data regarding the date of diagnosis available. Four patients were anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) negative.

Table 1.

All lupus patients: Baseline demographics, concomitant medications, and clinical manifestations driving treatment with belimumab.

| Baseline, n = 195 | |

|---|---|

| Female (%) | 82 |

| Mean age at diagnosis (range) | 40.7 ± 13.7 years (4 to 65 years) |

| Disease duration at initiation of belimumab (n=151) | 11.9 ± 8.1 years |

| Age at initiation of belimumab (range) | 41.8 ± 12.7 years (15 to 73 years) |

| Race | % |

| Caucasian | 61 |

| Black | 29 |

| Asian | 6 |

| Other | 2 |

| Ethnicity | % |

| Hispanic/Latino | 6 |

| Clinical Manifestations | % |

| Arthritis | 67 |

| Rash | 44 |

| Constitutional | 25 |

| Inability to Taper Steroids | 30 |

| Renal | 11 |

| Neuropsychiatric lupus | 9 |

| More than two manifestations | 67 |

| Laboratory Manifestations | % |

| Hematologic | 15 |

| Hypocomplementemia | 53 |

| Elevated anti-dsDNA antibodies | 37 |

| Concomitant Medications | % |

| Antimalarials | 73 |

| Prednisone | 74 |

| Mean dose prednisone equivalent | 12.2mg/day (range 5 to 50mg/day) |

| Immunosuppressive Agents | 48 |

| Mycophenolate | 34 |

| Azathioprine | 21 |

| Methotrexate | 11 |

| Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor | 6 |

| No SLE Medications | 7 |

Abbreviations: anti-dsDNA, anti-double stranded DNA; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus

Concomitant Medications

Of 195 patients, 7 adult-onset SLE patients were not taking any background SLE medications at the time of belimumab initiation (Table 1), while 73% were on antimalarials, and 74% were on corticosteroids. Of those on corticosteroids at initiation of belimumab, the mean daily prednisone equivalent dose was 12.2mg/day (range 5 to 50mg/day). The majority of patients (66%) were on immunosuppressive medications, with 21% on azathioprine and 34% on mycophenolate mofetil. No patients were concurrently receiving cyclophosphamide or rituximab.

Clinical Manifestations

At initiation of belimumab, the breakdown of clinical manifestations requiring treatment is detailed in Table 1. The main clinical manifestations driving treatment were musculoskeletal and mucocutaneous. Proteinuria was present in 11% of patients at the time of initiation of belimumab.

Belimumab was used off-label in 7 patients who were not on any background SLE medications at the time of initiation, though 4 were on daily oral corticosteroids. The clinical manifestations driving treatment were rash, arthritis and serositis. One patient was started on belimumab for constitutional symptoms.

Fifteen patients were on anti-malarial treatment alone at the time of initiation of belimumab. The main clinical manifestations driving treatment were rash, arthritis and serositis. Four patients had hematological abnormalities, and two patients had constitutional symptoms.

Response to belimumab

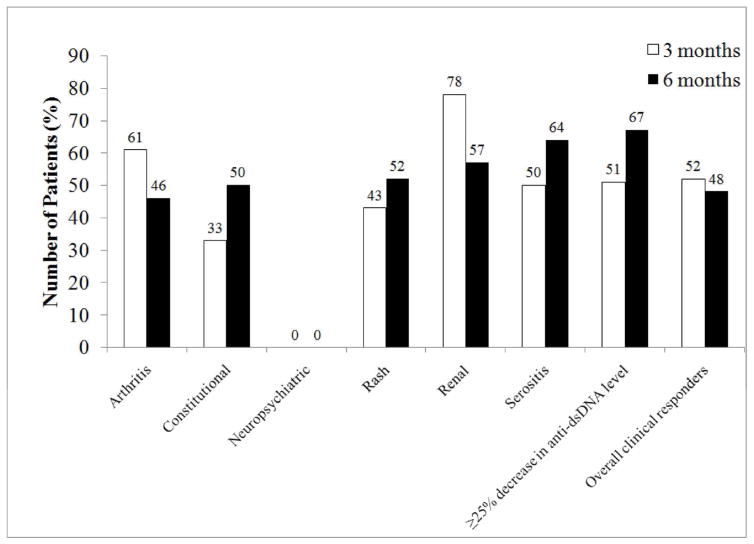

At three months of belimumab treatment, 52% of patients clinically responded to belimumab with improvement in the clinical manifestations driving initiation of belimumab (Figure 1). At 3 months, 61% of patients started on belimumab for arthritis, 43% of patients with rash, and 78% of patients with renal manifestations responded to therapy. At six months, data on 120 patients were available for analysis and showed 51% with clinical response. Responders included 46% of patients with arthritis, 52% of patients with rash, and 57% of patients with renal manifestations. The mean daily prednisone equivalent dose of corticosteroids decreased to 9.3mg/day at 6 months from 12.2mg/day at baseline (p=NS).

Figure 1.

Response to belimumab in all patients with lupus at 3 and 6 months after initiation of belimumab. Data were available on 158 patients at 3 months and 120 patients at 6 months of treatment. Clinical response was defined as the treating physician’s impression of ≥50% improvement in the initial manifestation(s) being treated and no worsening in other organ systems. Improvement in serology included at least 25% decrease in anti-dsDNA level from baseline.

At 3 months after initiation of belimumab, 68 of 103 patients (66%) had at least a 25% increase in C3 values, and 35 of 72 patients (48%) had a 25% decrease in anti-dsDNA values (Figure 1). This was maintained at 6 months, with 67% of patients demonstrating at least 25% decrease in anti-dsDNA values. No significant differences were found in either clinical or laboratory response rates in patients on different background immunosuppressive medications (data not shown).

Elderly Patients

Four patients were over 65 years of age at the time of initiation of belimumab therapy, and it was initiated off-label. The clinical manifestations driving treatment were arthritis in all patients and serositis in 2 patients. All patients were on daily oral prednisone at the time of initiation of therapy with a range of 3 to 11mg/day. Only one patient was on another immunosuppressive (mycophenolate mofetil), and no patients were on hydroxychloroquine. Two patients had elevated levels of anti-dsDNA antibodies, but no patients had hypocomplementemia. At 6 months, only one patient responded to therapy with resolution of arthritis and serositis and all patients remained on the same baseline dose of prednisone.

Black Patients

Data on blacks, although limited, show a similar pattern of improvement. Of 57 black patients, 4 were on no background medications at the start of belimumab. There were 17 patients on corticosteroids. The major clinical manifestations for initiation of belimumab were arthritis, inability to taper steroids, and rash. When compared to the non-black patients in the cohort, black patients showed a higher clinical response rate to belimumab at 3 months (82% vs 45%, p=0.0001). Data were available for 21 black patients on belimumab for 6 months; 67% responded to belimumab.

Lupus Nephritis Patients

Twelve patients in the cohort had a history of lupus nephritis and proteinuria ≥1000mg/24 hours at the time of initiation of belimumab. Follow-up data were available on 6 of these patients; 3 patients had ≥ 50% improvement in proteinuria after initiation of belimumab.

Childhood-onset SLE

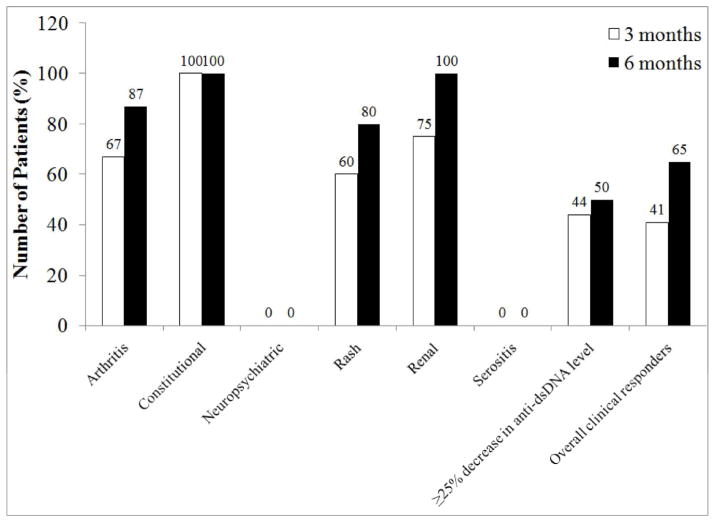

A subset of 39 patients treated with belimumab were diagnosed with SLE prior to their 18th birthday, most of whom were female (Table 2), with a mean disease duration of 12±8 years at initiation of belimumab. Four patients were under 18 years of age at the time of initiation of belimumab therapy, and it was initiated off-label. All childhood-onset SLE patients were on background medications at the start of belimumab, including 82% on corticosteroids with a mean daily prednisone equivalent dose of 17mg, compared to 72% of adult-onset SLE patients on corticosteroids with a mean daily dose of 11mg (p<0.01). The main clinical manifestations treated in childhood-onset SLE patients were the inability to taper corticosteroids, musculoskeletal, and mucocutaneous. In the 4 patients under 18 years of age who were treated off-label, the clinical manifestations driving decision to treat were rash in 2 patients, thrombocytopenia in 1, and inability to taper steroids in all four patients. Clinical improvement was detected at as early as 3 months after initiation of therapy in 41% of childhood-onset SLE patients. At six months of treatment with belimumab, 65% of childhood-onset SLE patients had clinically responded compared to 45% of adult-onset SLE patients (p=NS) (Figure 2). In addition, 18% of childhood-onset SLE patients on belimumab had at least 25% improvement in C3 levels and 44% had at least 25% decrease in anti-dsDNA values, three months after starting belimumab (p=0.0001), and this was maintained at 6 months.

Table 2.

Childhood-onset vs adult-onset lupus patients: Baseline demographics, concomitant medications, and clinical manifestations driving treatment with belimumab.

| Baseline | ||

|---|---|---|

| Childhood-onset SLE (n=39) | Adult-onset SLE (n=156) | |

| Women (%) | 90 | 92.3 |

| Mean age at diagnosis | 14 ± 4 years | 33 ± 12 years |

| Disease duration at initiation of belimumab | 12 ± 8 years | 11 ± 7 years |

| Age at initiation of belimumab | 27 ± 7 years * | 45 ± 11 years * |

| Race | % | |

| Caucasian | 46 | 65 |

| Black | 48 | 25 |

| Asian | 6 | 6 |

| Other | 0 | 4 |

| Ethnicity | % | % |

| Hispanic/Latino | 12 | 4 |

| Clinical Manifestations | % | % |

| Arthritis | 46 | 70 |

| Rash | 36 | 45 |

| Constitutional | 13 | 27 |

| Inability to Taper Steroids | 82 | 28 |

| Renal | 15 | 11 |

| Neuropsychiatric lupus | 0 | 10 |

| Laboratory Manifestations | % | % |

| Hematologic | 5 | 12 |

| Hypocomplementemia | 59% | 52% |

| Elevated anti-dsDNA antibodies | 84% | 29% |

| Concomitant Medications | % | % |

| Antimalarials | 92 | 68 |

| Prednisone | 82 * | 72 |

| Mean dose prednisone equivalent | 17mg/day * | 11mg/day |

| Immunosuppressive Agents | 72 | 53 |

| Mycophenolate | 49 | 33 |

| Azathioprine | 23 | 20 |

| Methotrexate | 0 | 14 |

| Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor | 8 | 4 |

| No SLE Medications | 0 | 4 |

Figure 2.

Response to belimumab in patients with childhood-onset lupus at 3 and 6 months after initiation of belimumab. Data were available on 35 patients at 3 months and 26 patients at 6 months of treatment. Clinical response was defined as the treating physician’s impression of ≥50% improvement in the initial manifestation(s) being treated and no worsening in other organ systems. Improvement in serology included at least 25% decrease in anti-dsDNA level from baseline.

Moreover, six months after initiation of belimumab, the mean prednisone equivalent dose decreased from 17mg/day in childhood-onset SLE patients to 11mg/day. Steroids were discontinued in 35% of childhood-onset SLE patients 6 months after belimumab initiation, as compared with 11% of adult-onset SLE patients (p=0.002).

Safety

Data on adverse events and discontinuation of belimumab are presented in Table 3. No deaths were reported and 32 patients (16%) discontinued belimumab after an average of approximately nine months across all sites. The most common adverse effects and reasons for discontinuation of therapy were infection and lack of response to belimumab. The most serious infection was Group A Streptococcal bacteremia that occurred in one patient during the time she was on treatment with belimumab. She had also had an elective cervical lymph node biopsy performed 5 days prior to development of bacteremia. The lack of response to belimumab included patients who demonstrated no improvement and/or worsening clinical manifestations of disease while on belimumab, or developed new organ system involvement, as judged by the treating physicians.

Table 3.

Adverse events and reason(s) for discontinuation of belimumab.

| Reasons for Discontinuation | |

| Development/worsening neuropsychiatric lupus | 6 |

| Severe disease flares | 4 (renal, arthritis) |

| Myocardial Infarction | 1 |

| Loss of Insurance | 2 |

| Infection | 7 {most severe: pneumonia, Group A streptococcus bacteremia, axillary MRSA*} |

| Infusion Reaction | 3 |

| Elective Surgery | 1 |

| Patient Choice | 2 |

| No Clinical Response | 6 |

| Total (out of 195) | 32 (16%) |

Note:

Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus

Of note, 4 patients developed features of neuropsychiatric lupus (NPSLE) while on belimumab (one with stroke, one with psychosis, one with severe depression, and one with new-onset seizures), and 2 patients who had existing NPSLE experienced worsening of disease while on belimumab (one with worsening depression, the other without specifics reported). There were also 3 patients who developed or experienced worsening of lupus nephritis over a year after initiation of therapy.

A total of 9 black patients discontinued belimumab, 2 due to exacerbation of renal disease, 2 due to development of or worsening neuropsychiatric disease, 1 due to arthritis flare, 1 due to worsening myositis. Discontinuation reasons not related to lupus included 1 infusion reaction, 1 who lost her insurance, and 1 who self-discontinued.

DISCUSSION

Belimumab is the first FDA-approved drug for the treatment of SLE in several decades and marks a breakthrough in drug development in SLE (21). This study evaluates the efficacy and safety of belimumab in 10 large academic clinical practices, and is the first report of the efficacy and safety of belimumab in childhood-onset SLE.

Post-hoc analyses of the phase II belimumab trial data resulted in the development of a novel SLE responder index, which served as a primary endpoint in the phase III program (22); however, the stringency of this index precludes its practical use in routine clinical settings. Therefore, the definition of clinical response used in this study is a simplified version of the SRI; clinical response in this study was constructed around the treating physician’s subjective assessment of at least 50% improvement clinical manifestations, similar to the SLEDAI SRI-50 (23, 24). Our data suggest that clinical improvement in response to belimumab may be detected as early as 3 months after initiation of therapy, and 51% of patients show a response at 6 months. Improvements in complement and dsDNA antibody levels were seen as early as 3 months after initiation of belimumab therapy and continued through the 6-month follow-up.

Since the results of the phase III trials, post-marketing analyses have consistently demonstrated arthritis and mucocutaneous disease as common indications for the initiation of belimumab therapy (25). Interestingly, less than 5% of the cohort as a whole were on treatment with methotrexate prior to initiation of belimumab. Our data in a subset of patients with childhood-onset SLE demonstrate similar trends; however, our data also show that over 80% of childhood-onset SLE patients were started on belimumab due to an inability to taper existing steroids for treatment of lupus. Childhood-onset SLE patients may respond in as quickly as 3 months after initiation of belimumab (41%) and a greater proportion responded to belimumab (65%) than adult-onset SLE patients (45%) at 6 months (p=NS). The ability to taper and often discontinue corticosteroids in childhood-onset SLE patients while on treatment with belimumab may, in part, reflect a degree of non-compliance to oral immunosuppressive medications in these patients.

Despite the small sample sizes in this study, serologically positive SLE patients responded favorably to treatment with belimumab plus standard of care therapy. This is consistent with the phase III belimumab trials (7, 8, 26). Moreover, given the higher prevalence of SLE in black patients (27, 28), it is of interest to note that 67% of a subset of black patients responded to belimumab therapy at 6 months. Subset analyses in phase III trials yielded lower response rates of black patients receiving belimumab versus those receiving placebo. Our data demonstrate a better clinical response rate in blacks that is significantly higher than those of other racial or ethnic subsets. Thus, results from clinical trials currently underway focusing on black patients would be of utmost importance to individually tailor therapy.

Further studies in a larger population and for a longer time period will also be of benefit to examine long-term outcomes and delineate adverse events. Ginzler et al (29) recently noted that there was a reduced risk of SLE flare and continued improvement in clinical and laboratory markers 7 years after initiation of belimumab therapy. Studies in patients with lupus nephritis and/or NPSLE would also help define the role for belimumab and describe the target population for optimal response. Although NPSLE patients have been excluded from trials to date, there are ongoing trials using belimumab for patients with lupus nephritis which will provide more definitive answers.

Although data are limited, belimumab appears to be well-tolerated; 16% of patients experienced an adverse event. This is a much lower rate of occurrence than reported by Wallace et al (30) in a post-hoc analysis of the phase III trials. In the phase III trials, 6% of patients developed depression, and 0.1% had suicidal ideation on belimumab therapy. In our cohort, there were 6 patients who developed or had an exacerbation of existing NPSLE; belimumab was discontinued in all these patients. Wallace et al (30) also noted a small percentage of renal disease flare in patients on belimumab therapy. In addition, Dooley et al (31) demonstrated in a post-hoc analysis of the phase III trial patients that of the 267 patients with renal disease at the time of initiation of belimumab therapy, those on baseline immunosuppressive medications or with serologic activity at baseline had greater renal improvement on belimumab than those with placebo. They also note that renal flares and reduction of renal symptomatology such as proteinuria and serologic activity appeared to occur more frequently in patients on belimumab but was not statistically significant when compared with placebo. Our data show that three patients developed or had an exacerbation of lupus nephritis; all were childhood-onset SLE patients. However, in these patients, non-compliance with background standard-of-care lupus immunosuppressive medications may have also played a role in worsening lupus nephritis.

Moreover, given that we defined the lack of response to be no improvement and/or worsening disease in any involved organ system, and/or development of disease in another previously uninvolved organ system, it is possible that the inclusion of these patients in calculating our response rate may reflect a lower rate of response than could be expected. Other limitations include the short time of follow-up (6 months) in this study, and the lack of comparison to a control group. This may have led us to overstate the efficacy of belimumab in our population.

In summary, this study further substantiates the safety and efficacy of belimumab in the treatment of SLE. The higher clinical response rate among black patients, with comparable safety, is reassuring and should help alleviate concerns regarding the use of belimumab in this racial group. Overall, belimumab appears to be well-tolerated; however, caution is advised with its use in SLE patients with active NPSLE and/or renal disease until more data are available. Moreover, our data suggest a larger role for belimumab as a corticosteroid-sparing agent in childhood-onset SLE given that 35% of patients were able to discontinue steroid treatment after the addition of belimumab to standard-of-care lupus treatments. The results of the clinical trials currently underway in pediatric SLE patients (under 18 years of age) will be of interest in demonstrating the efficacy and safety of belimumab in this population.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients for their participation in this study.

Footnotes

Disclosures and funding: This work was supported by an investigator-initiated award to the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus International Collaborating Clinics from Glaxo-Smith-Kline. Joyce S Hui-Yuen is the recipient of a T32 Medical Genetics training grant from the National Institutes of Health. Anca D Askanase is a consultant for Glaxo Smith Kline (< $10,000 in the past 12 months), and Michelle Petri has consulted for Glaxo Smith Kline in the past.

References

- 1.Askanase A, Shum K, Mitnick H. Systemic lupus erythematosus: an overview. Soc Work Health Care. 2012;51:576–86. doi: 10.1080/00981389.2012.683369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xiong W, Lahita RG. Pragmatic approaches to therapy for systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2014;10:97–107. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2013.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parodis I, Axelsson M, Gunnarsson I. Belimumab for systemic lupus erythematosus: a practice-based view. Lupus. 2013;22:372–80. doi: 10.1177/0961203313476154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cancro MP, D’Cruz DP, Khamashta MA. The role of B lymphocyte stimulator (BLyS) in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1066–73. doi: 10.1172/JCI38010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang J, Roschke V, Baker KP, Wang Z, Alarcon GS, Fessler BJ, et al. Cutting edge: a role for B lymphocyte stimulator in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol. 2001;166:6–10. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petri M, Stohl W, Chatham W, McCune WJ, Chevrier M, Ryel J, et al. Association of plasma B lymphocyte stimulator levels and disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:2453–9. doi: 10.1002/art.23678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Navarra SV, Guzman RM, Gallacher AE, Hall S, Levy RA, Jimenez RE, et al. Efficacy and safety of belimumab in patients with active systemic lupus erythematosus: a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2011;377:721–31. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61354-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Furie R, Petri M, Zamani O, Cervera R, Wallace DJ, Tegzova D, et al. A phase III, randomized, placebo-controlled study of belimumab, a monoclonal antibody that inhibits B lymphocyte stimulator, in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:3918–30. doi: 10.1002/art.30613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mina R, Brunner HI. Pediatric lupus--are there differences in presentation, genetics, response to therapy, and damage accrual compared with adult lupus? Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2010;36:53–80. vii–viii. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Font J, Cervera R, Espinosa G, Pallares L, Ramos-Casals M, Jimenez S, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) in childhood: analysis of clinical and immunological findings in 34 patients and comparison with SLE characteristics in adults. Ann Rheum Dis. 1998;57:456–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.57.8.456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brunner HI, Gladman DD, Ibanez D, Urowitz MD, Silverman ED. Difference in disease features between childhood-onset and adult-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:556–62. doi: 10.1002/art.23204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hersh AO, von Scheven E, Yazdany J, Panopalis P, Trupin L, Julian L, et al. Differences in long-term disease activity and treatment of adult patients with childhood- and adult-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:13–20. doi: 10.1002/art.24091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramirez Gomez LA, Uribe Uribe O, Osio Uribe O, Grisales Romero H, Cardiel MH, Wojdyla D, et al. Childhood systemic lupus erythematosus in Latin America. The GLADEL experience in 230 children. Lupus. 2008;17:596–604. doi: 10.1177/0961203307088006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tucker LB, Menon S, Schaller JG, Isenberg DA. Adult- and childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus: a comparison of onset, clinical features, serology, and outcome. Br J Rheumatol. 1995;34:866–72. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/34.9.866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tucker LB, Uribe AG, Fernandez M, Vila LM, McGwin G, Apte M, et al. Adolescent onset of lupus results in more aggressive disease and worse outcomes: results of a nested matched case-control study within LUMINA, a multiethnic US cohort (LUMINA LVII) Lupus. 2008;17:314–22. doi: 10.1177/0961203307087875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hui-Yuen JS, Imundo LF, Avitabile C, Kahn PJ, Eichenfield AH, Levy DM. Early versus later onset childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus: Clinical features, treatment and outcome. Lupus. 2011;20:952–9. doi: 10.1177/0961203311403022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1725. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petri M, Orbai AM, Alarcon GS, Gordon C, Merrill JT, Fortin PR, et al. Derivation and validation of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:2677–86. doi: 10.1002/art.34473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petri MBS, Buyon J, Davis J, Ginzler E, Kalunian K, et al. RIFLE: Responder Index for Lupus Erythematosus [abstract] Arthritis Rheum Suppl. 2000;43 (Suppl 9):S244. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yee CS, Farewell V, Isenberg DA, Griffiths B, Teh LS, Bruce IN, et al. The BILAG-2004 index is sensitive to change for assessment of SLE disease activity. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48:691–5. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mosca M, van Vollenhoven R. New drugs in systemic lupus erythematosus: when to start and when to stop. Clin Exp Rheumatol Suppl. 2013;31 (Suppl 78):S82–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Furie RA, Petri MA, Wallace DJ, Ginzler EM, Merrill JT, Stohl W, et al. Novel evidence-based systemic lupus erythematosus responder index. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:1143–51. doi: 10.1002/art.24698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Touma Z, Gladman DD, Ibanez D, Urowitz MB. Development and initial validation of the systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index 2000 responder index 50. J Rheumatol. 2011;38:275–84. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.100724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Touma Z, Gladman DD, Ibanez D, Taghavi-Zadeh S, Urowitz MB. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index 2000 Responder Index-50 enhances the ability of SLE Responder Index to identify responders in clinical trials. J Rheumatol. 2011;38:2395–9. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.110550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Askanase AD, Yazdany J, Molta CT. Post-marketing experiences with belimumab in the treatment of SLE patients. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2014;40:507–17. viii. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Vollenhoven RF, Petri MA, Cervera R, Roth DA, Ji BN, Kleoudis CS, et al. Belimumab in the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus: high disease activity predictors of response. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:1343–9. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chakravarty EF, Bush TM, Manzi S, Clarke AE, Ward MM. Prevalence of adult systemic lupus erythematosus in California and Pennsylvania in 2000: estimates obtained using hospitalization data. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:2092–4. doi: 10.1002/art.22641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pineles D, Valente A, Warren B, Peterson MG, Lehman TJ, Moorthy LN. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of pediatric onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2011;20:1187–92. doi: 10.1177/0961203311412096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ginzler EM, Wallace DJ, Merrill JT, Furie RA, Stohl W, Chatham WW, et al. Disease control and safety of belimumab plus standard therapy over 7 years in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2014;41:300–9. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.121368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wallace DJ, Navarra S, Petri MA, Gallacher A, Thomas M, Furie R, et al. Safety profile of belimumab: pooled data from placebo-controlled phase 2 and 3 studies in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2013;22:144–54. doi: 10.1177/0961203312469259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dooley MA, Houssiau F, Aranow C, D’Cruz DP, Askanase A, Roth DA, et al. Effect of belimumab treatment on renal outcomes: Results from the phase III belimumab clinical trials in patients with SLE. Lupus. 2013;22:63–72. doi: 10.1177/0961203312465781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]