Abstract

As cancer survivors live longer, fertility and reproductive health become important health concerns. Like other secondary effects of cancer treatment, these anticipated health risks should be addressed before the initiation of cancer treatment. While existing and emerging technologies may prevent or reduce risk of infertility (e.g., sperm, oocyte, embryo, or tissue banking), the lack of a trained workforce knowledgeable about oncology and reproductive health poses a barrier to care. The allied health professional (AHP) is a target of opportunity because of the direct and sustained patient relationships. Thus, developing tailored educational programs for nurses, social workers, psychologists, and physician assistants is an urgent unmet need toward field building. In this report, we outline results from a pilot study evaluating AHP perceptions of an oncology and reproductive health curriculum originally developed for nurses and adapted to meet the needs of several other AHP groups.

Keywords: : fertility, oncofertility, psychosocial, quality of life, survivorship, supportive care

Introduction

In 2013, the ASCO published updated clinical practice guidelines for fertility preservation (FP) in patients of reproductive age with cancer.1 Importantly, the new guidelines extend the responsibility for discussion and referral for FP beyond the medical oncologist to explicitly include other physician specialties and allied healthcare professionals (AHPs) in the oncology care setting. This recommendation supports the widely adopted multidisciplinary approach used in many cancer care settings.2,3 Given that some members of the oncology care team may see patients even earlier in the diagnosis and treatment process than the medical oncologist, these guidelines may empower other team members to view fertility communications with patients and/or reproductive specialists on behalf of their patients within their professional role.

AHPs plays an important role in the care of adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancer patients. While oncologists treat the disease, it is often the AHP who provides the psychosocial care that facilitates quality of life outcomes across multiple domains. Allied health professionals involved in the care of AYA include, but are not limited to, social workers, genetic counselors, psychologists, child life specialists, and physician assistants. Each AHP has a unique function in the care of the AYA patient, but all are likely to assist with the provision of health education and information related to quality of life and decision making.4 Training AHPs may also enhance oncofertility service and ease the communication burden for oncologists, while not dissolving them completely of the responsibility, by allowing them to start the initial discussion and then pass the baton to the AHP for in-depth conversations about this topic.

Despite revised ASCO guidelines suggesting the important role of AHP, there has been limited attention toward training these professionals for this role. Moreover, informal discussions at the annual oncofertility meeting indicate a great desire for expanded training as well as concern that they are currently not equipped with the knowledge needed to assist patients with fertility decisions in the cancer setting (personal observation of the author team).5 Given this documented level of interest by AHPs and knowing that their current oncofertility knowledge is limited, we propose that more formal training in this area is warranted and would support the intent of the new ASCO guidelines.1 To fulfill this role, AHP would need a sufficient knowledge base that would include knowledge about the potential damage to reproductive capacity from chemotherapy, radiation, or surgery; FP options and post-treatment parenthood options; the unique contraception needs of those on and off treatment; the role of reproductive capacity in self- and body image; perceived sexuality; and romantic partnering. A general knowledge regarding these elements of the discussion with an oncofertility patient, parent, or partner may empower the AYA in an otherwise discouraging setting, enable better patient decisions, and ensure that oncology time is focused on patient cancer care.

While the ASCO guidance regarding discussions with patients is clear, educational materials across the oncofertility professional spectrum are sparse. Several programs, such as Cancer Survivorship Training (CST), ASCO: Focus Under Forty, and LIVESTRONG: Fertility Training for Healthcare Professionals, feature content specifically on fertility and preservation, but few programs focus specifically on all aspects of reproductive health. However, the newly developed Educating Nurses About Reproductive Issues in Cancer Health (ENRICH) program is a validated and effective skill-building curriculum targeting oncology nurses that focuses on all aspects of reproductive health.6 As a first step toward modifying the current program for AHPs, we conducted a pilot study to assess the relevance of ENRICH content to AHPs.

Methods

Overview of ENRICH training program

ENRICH is a web-based training program that includes psychosocial, biological, clinical, and skill-building modules to help oncology nurses communicate timely and relevant information regarding reproductive health to their AYA patients. Over 8 weeks, nurses complete a series of six content modules and two skill-building modules comprising narrated PowerPoint presentations delivered by national experts, readings from the course textbook,7 case studies, and hands-on learning assignments focused on interviewing an adoption agency8 and a local reproductive endocrinologist infertility specialist.

The beginning sequence of the modules primarily focuses on infertility and FP options, including (1) an overview of reproductive health in AYAs, (2) male reproductive health and cancer, (3) female reproductive health and cancer, and (4) reproductive health concerns for pediatric cancer patients. Two modules covered other reproductive issues: (5) alternative family-building options and (6) sexual health. The last two modules focus on skill building, specifically, how to talk about infertility and FP options, including (7) demonstrations with a nurse specialist modeling these discussions about fertility and FP with standardized patients and (8) practical applications in which a fertility navigator presents strategies to overcome institutional, systematic, and financial barriers to FP. Additionally, ethical, legal, and psychosocial considerations attendant to FP were infused throughout all modules.

Adaptation of program for AHP

The pilot study was conducted using a multipronged approach, which included an AHP expert panel review, a cohort of AHP learners, and feedback from the ENRICH research team.

AHP expert panel review

We sought one expert from each of the AHP professions (other than nurses) that our team identified as having the capacity and likelihood to address reproductive health issues for AYA patients. These included a genetic counselor, a physician assistant, a child life specialist, a psychologist, and a social worker. Each expert was selected based on his or her professional training, having a clinical and/or research focus on AYA oncology, and having an active role in his or her professional organization(s).

Each was asked to review the ENRICH curriculum, assess appropriateness for his or her profession, and suggest how to better tailor the curriculum for his or her profession. Each week, for 8 weeks, reviewers were sent module review materials, which consisted of a case study, textbook readings, a PowerPoint-narrated lecture, and a module-specific survey. A five-question survey was delivered via email to reviewers upon completion of each module, each week. The module-specific survey contained four Likert scale questions and one open-ended question. After the review of all modules, a teleconference was convened to discuss overall feedback and suggestions.

Pilot AHP cohort

Learners were recruited by email to professional organizations, such as the Association of Oncology Social Workers, the American Psychosocial Oncology Society, the Intercultural Cancer Council, and the Child Life Council. Applicants were reviewed, scored, and selected by members of the ENRICH applicant review committee. Each trainee was offered a certificate of completion and a $100 stipend upon completion of all course requirements.

A total of 12 applicants were offered the opportunity to participate in the training program. This included social workers (n = 6), physician assistants (n = 1), and child life specialists (n = 5) to assess the feasibility of the adapted curriculum for their profession. A 14-item pretest was administered before the first module of the course and a posttest after the sixth module to assess knowledge gained. Additionally, a brief survey, which consisted of three Likert scale questions and one open-ended question to assess learner satisfaction and perceptions, was completed by learners after completion of each module. Another measure of satisfaction was an overall program evaluation, which was posted to the training platform and contained yes/no, Likert scale, and open-ended questions.

ENRICH expert panel feedback

Each year, the ENRICH team holds a meeting of all affiliated consultants, faculty, and expert panel members to review course content, evaluation results, and recruitment strategies. In 2015, we added a discussion of the AHP pilot cohort data. All data were presented to and reviewed by our expert panel.

Results

AHP expert panel review

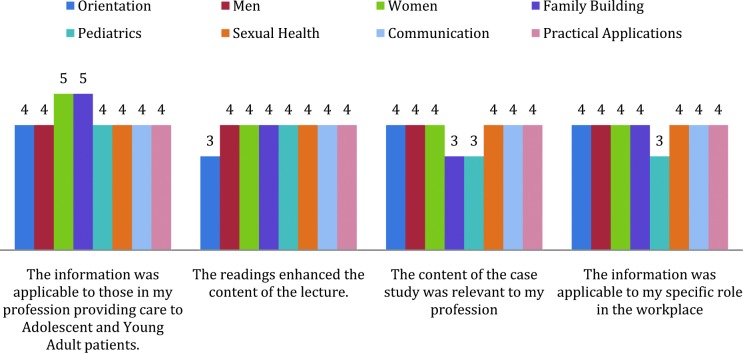

The module-specific survey contained four Likert scale questions and one open-ended question. Each of the five experts rated each module a 3 or higher (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, and 5 = strongly agree) in dictating the information was applicable to their specific profession, the case studies were relevant to their roles in the workplace, and that the readings enhanced the lecture content (Fig. 1). Additionally, the five experts rated all modules a 4 or higher reporting that the course information was applicable to their profession providing care to AYA patients.

FIG. 1.

Expert panel module-specific ratings (n = 6). Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/jayao

Suggestions from the teleconference included creating a glossary of terms and definitions for nonnurse professionals, offering continuing education credits for each AHP, and creating a skill demonstration video tailored for each profession parallel to the clinical nurse specialist demonstration video in ENRICH. The panel unanimously agreed that the modification of ENRICH for the purpose of training AHPs in reproductive health would be a tremendous asset to learners' professional growth and would improve the quality of care for AYA patients.

Pilot AHP cohort

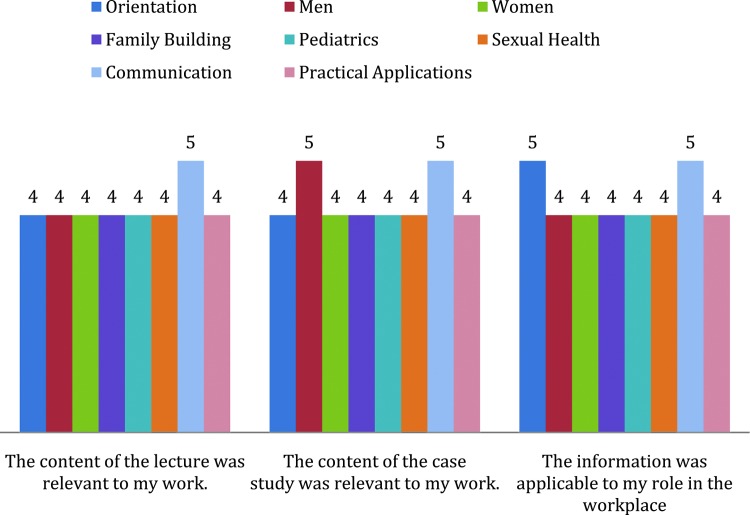

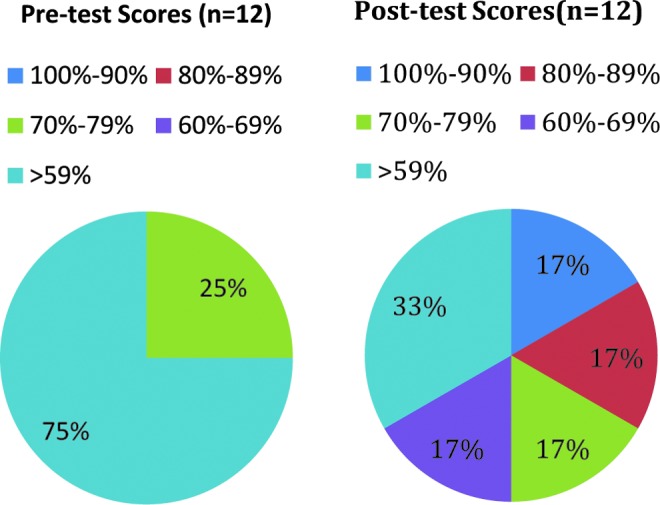

Eleven of the 12 learners completed the entire course, a 91.6% completion rate. At baseline, 25% (n = 3) of the learners scored in the 70%–79% correct range and 75% (n = 8) scored below 59%. Postcourse, the majority of learners increased their score by 17% scoring in the 90%–100% range (Fig. 2). On average, AHP learners rated each module at a 4 or higher (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, and 5 = strongly agree), indicating the information was applicable to their role in the workplace and the content of the case study and the recorded lectures were relevant to their work (Fig. 3). Of the 11 learners who completed the course, 90% (n = 10) indicated they learned a great deal from the training program and 100% (n = 11) reported a perceived increase in patient care confidence as a result of participation. Additionally, 100% (n = 11) reported they would recommend the course to others in their profession.

FIG. 2.

Pilot cohort pre-/posttest results (n = 12). Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/jayao

FIG. 3.

Pilot cohort module-specific ratings (n = 12). Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/jayao

ENRICH expert panel feedback

Based on the results reported to the ENRICH expert panel and the following discussion, it was determined that adapting the curriculum for AHPs was a feasible opportunity and that the training program should continue to train nurses and expand to physician assistants, social workers, and psychologists. It was determined that child life specialists' interactions with patients were not the most appropriate time to facilitate discussion about reproductive health topics and that many worked more in younger pediatric rather than AYA oncology populations. Thus, we elected not to include this AHP group in our proposed training. Additionally, the panel indicated that genetic counselors may not be an appropriate audience for the program because of the times and context of their patient interaction. Although we did not recruit a psychologist for the pilot group either, the expert panel felt strongly the content was appropriate for a clinical psychologist, and with broader recruitment efforts, there would be high demand for the training.

Discussion

Few prior studies have objectively measured oncology AHP knowledge about key aspects of reproductive health for AYA cancer patients; of those available, the majority are focused on infertility and FP and do not include other aspects or reproductive health.9,10 Our findings should also be considered in light of limitations as baseline involvement in FP discussions was not assessed. While research is available regarding oncologists' and nurses' knowledge of reproductive health topics, limited knowledge is available specific to AHPs. A single-institution study by Goodwin et al. of 30 pediatric oncology providers (n = 14 nurses) reported that only about half were aware of gender-specific infertility risks or experimental FP options for females, such as ovarian tissue cryopreservation.11

While there are no studies to our knowledge specific to physician assistants and their role in addressing reproductive health issues for AYA, the Guidelines for Ethical Conduct for the Physician Assistant Profession briefly discusses the physician assistant role in reproductive health decision making in general, stating that physician assistants have an ethical obligation to provide balanced and unbiased clinical information about reproductive healthcare and must ensure that all patients have a right to access the full range of reproductive healthcare services.12

Our prior research with social workers suggests that this topic is not consistently discussed with patients, despite social workers being in an optimal position to facilitate discussions and referrals between the oncologist, reproductive endocrinologists, and patients. Factors that influenced the discussion of FP between social workers and patients included limited knowledge, perceived comfort/efficacy, and barriers, such as cost and urgency to start treatment.13

There is far less known specifically about psychologists and their role in addressing reproductive health issues with AYA patients. However, a recent overview of psychological counseling for female patients for issues, including distress in patients undergoing treatment, choice of FP strategy in the face of an uncertain relationship future, decision making about third-party reproduction (expectations about pregnancy and miscarriage and ethical issues related to treatment, including the creation, cryopreservation, and disposition of embryos/oocytes), and decisional regret in those who declined FP, clearly demonstrates that psychologists working with AYA patients have a significant role in addressing reproductive health concerns.14

Importantly, The Oncofertility Consortium and the LIVESTRONG Young Adult Alliance have clearly recognized each of these AHPs as having a key role in the care of AYA patients.15,16 As such, oncofertility care topics should be incorporated into the curriculum for AHPs at both undergraduate and postgraduate levels to ensure that oncofertility care becomes the standard practice. Additionally, multidisciplinary colleagues have the need to be skilled in the area of reproductive health to provide support to patients who experience fertility-related psychosocial distress during treatment or into survivorship as reproductive health concerns may arise.

Our pilot study suggests that AHPs have interest in and would benefit from expanded training in discussing reproductive health issues with AYA oncology patients. We are currently adapting the curriculum to reflect results from the pilot study and expert panel review suggestions. Future research will also explore the creation of a team plan for management and other multidisciplinary team members of oncofertility and assess the feasibility of these teams in various practice settings. Additionally, there is need to train AHP in the fertility care setting. Future research will examine existing training for these professionals and identify if modifications or expansions are needed. Another area of future research will examine patient and cancer clinician satisfaction with receiving oncofertility information/support from members of the AHP and nursing team.

Acknowledgment

This project is funded by the National Cancer Institute R25 Training Grant No. 5R25CA142519. The authors would like to thank the ENRICH Working Group.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Loren AW, et al. Fertility preservation for patients with cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(19):2500–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fennell ML, et al. The organization of multidisciplinary care teams: modeling internal and external influences on cancer care quality. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2010;2010(40):72–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ueno NT, et al. ABC conceptual model of effective multidisciplinary cancer care. Nature reviews. Clin Oncol. 2010;7(9):544–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McElwaine KM, Freund M, Campbell EM, et al. Patient education: clinician assessment, advice and referral for multiple health risk behaviors: Prevalence and predictors of delivery by primary health care nurses and allied health professionals. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;9(4):193–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Oncofertility Consortium. The Oncofertility Consortium, 2016. Accessed December28, 2015 from: http://oncofertility.northwestern.edu/

- 6.Vadaparampil ST, Hutchins NM, Quinn GP. Reproductive health in the adolescent and young adult cancer patient: an innovative training program for oncology nurses. J Cancer Educ. 2013;28(1):197–208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quinn GP, Vadaparampil S. Reproductive health and cancer in adolescents and young adults. New York: Springer, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quinn GP, Zebrack BJ, Sehovic I, et al. Adoption and cancer survivors: findings from a learning activity for oncology nurses. Cancer. 2015;121(17):2993–3000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waimey KE, Duncan FE, Su HI, Smith K, et al. Future directions in oncofertility and fertility preservation: A report from the 2011 Oncofertility Consortium Conference. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2013;2(1):25–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goetsch AL, Wicklund C, Clayman ML, Woodruff TK. Reproductive endocrinologists' utilization of genetic counselors for oncofertility and preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) treatment of BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. J Genet Couns. 2015. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodwin T, et al. Attitudes and practices of pediatric oncology providers regarding fertility issues. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48(1):80–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zimmerman RK, et al. Predictors of pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccination among patients at three inner-city neighborhood health centers. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2005;3(3):149–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.King L, et al. Oncology social workers' perceptions of barriers to discussing fertility preservation with cancer patients. Soc Work Health Care. 2008;47(4):479–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lawson AK, et al. Psychological counseling of female fertility preservation patients. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2015;33(4):333–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The Oncofertilty Consortium. Your Healthcare Team. 2015. Accessed December28, 2015 from: http://oncofertility.northwestern.edu/your-health-care-team

- 16.Hayes-Lattin B, Mathews-Bradshaw B, Siegel S. Adolescent and young adult oncology training for health professionals: a position statement. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(32):4858–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]