Version Changes

Revised. Amendments from Version 2

We have amended the manuscript as suggested by the reviewer. Specifically:

The Abstract and Introduction no longer state that the requirements of the SB approach, time and memory, need to scale quadratically with the number of genomes.

We have modified the Discussion to further emphasize that DAB is similar to SB methods which extend existing groups into new genomes.

We have also rephrased the reviewers’ comment regarding the extensive use of DAB to define domain families, as we think it might further clarify the text.

The sentence “Our aim was to investigate whether using HMMs instead of sequence similarity would yield similar results” has been modified as suggested, to: “Our aim was to investigate whether using domain architectures instead of sequence similarity alone would yield similar results.”

Abstract

A functional comparative genome analysis is essential to understand the mechanisms underlying bacterial evolution and adaptation. Detection of functional orthologs using standard global sequence similarity methods faces several problems; the need for defining arbitrary acceptance thresholds for similarity and alignment length, lateral gene acquisition and the high computational cost for finding bi-directional best matches at a large scale. We investigated the use of protein domain architectures for large scale functional comparative analysis as an alternative method. The performance of both approaches was assessed through functional comparison of 446 bacterial genomes sampled at different taxonomic levels. We show that protein domain architectures provide a fast and efficient alternative to methods based on sequence similarity to identify groups of functionally equivalent proteins within and across taxonomic boundaries, and it is suitable for large scale comparative analysis. Running both methods in parallel pinpoints potential functional adaptations that may add to bacterial fitness.

Keywords: Bacterial genomics, Bacterial functionome, Orthology, Horizontal gene transfer, clustering, semantic annotation

Introduction

Comparative analysis of genome sequences has been pivotal to unravel mechanisms shaping bacterial evolution like gene duplication, loss and acquisition 1, 2, and helped in shedding light on pathogenesis and genotype-phenotype associations 3, 4.

Comparative analysis relies on the identification of sets of orthologous and paralogous genes and subsequent transfer of function to the encoding proteins. Technically orthologs are defined as best bi-directional hits (BBH) obtained via pairwise sequence comparison among multiple species and thus exploits sequence similarity for functional grouping. Sequence similarity-based (SB) methods present a number of shortcomings. First, a generalized minimal alignment length and similarity cut-off need to be arbitrarily selected for all, which may hamper proper functional grouping. Second, sequence and function might differ across evolutionary scales. Protein sequences change faster than protein structure and proteins with same function but with low sequence similarity have been identified 5, 6. SB methods may fail to group them hampering a functional comparison. This limitation becomes even more critical when comparing either phylogenetically distant genomes or gene sequences that were acquired with horizontal gene transfer events. Recent technological advancements are resulting in thousands of organisms and billions of proteins being sequenced 7 which increases the need of methods able to perform comparisons at the larger scales.

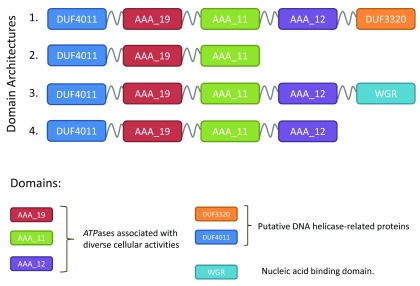

To overcome these bottlenecks, protein domains have been suggested as an alternative for defining groups of functionally equivalent proteins 8– 10 and have been used to perform comparative analyses of Escherichia coli 9, Pseudomonas 10, Streptococcus 11 and for protein functional annotation 12, 13. A protein domain architecture describes the arrangement of domains contained in a protein and is exemplified in Figure 1. As protein domains capture key structural and functional features, protein domain architectures may be considered to be better proxies to describe functional equivalence than a global sequence similarity 14. The concept of using the domain architecture to precisely describe the extent of functional equivalence is exemplified in Figure 2. Moreover, once the probabilistic domain models have been defined, mining large sets of individual genome sequences for their occurrences is a considerably less demanding computational task than an exploration of all possible bi-directional hits between them 15, 16.

Figure 1. Domain architecture as a formal description of functional equivalence.

Although the proteins obviously share a common core, four distinct domain architectures involving six protein domains were observed in (1) Enterobacteriaceae, (2) H. pylori, (3) Pseudomonas and (4) Cyanobacteria.

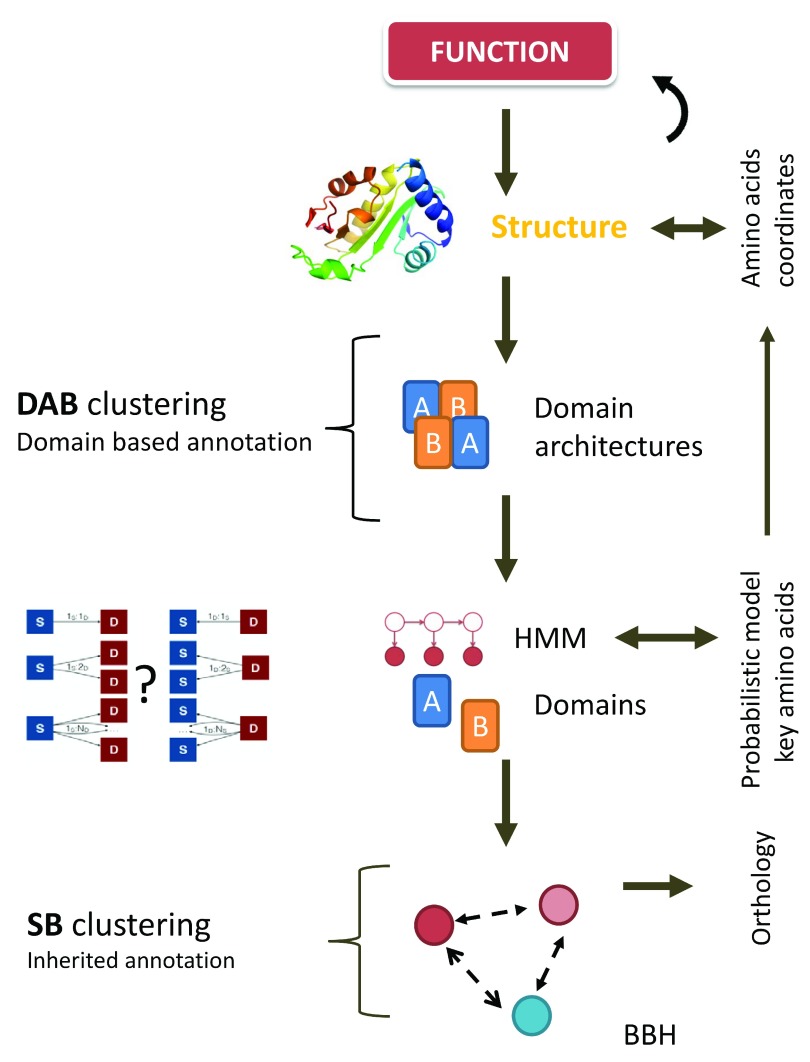

Figure 2. Relationship between Domain Architecture Based (DAB) and Sequence Similarity based (SB) clustering with respect to functional annotation.

Domains are probabilistic models of amino acids coordinates obtained by hidden Markov modeling (HMM) built from (structure based) multiple sequence alignments. Domain architectures are linear combinations of these domains representing the functional potential of a given protein sequence and constitute the input for DAB clustering. SB-orthology clusters inherit functional annotations via best bi-directional hits above a predefined sequence similarity cut-off score.

Domain architectures have been shown to be preserved at large phylogenetic distances both in prokaryotes and eukaryotes 17, 18. This lead to the use of protein domain architectures to classify and identify evolutionarily related proteins and to detect homologs even across evolutionarily distant species 19– 22. Structural information encoded in domain architectures has also been deployed to accelerate sequence search methods and to provide better homology detection. Examples are CDART 23 which finds homologous proteins across significant evolutionary distances using domain profiles rather than direct sequence similarity, or DeltaBlast 24 where a database of pre-constructed position-specific score matrix is queried before searching a protein-sequence database. Considering protein domain content, order, recurrence and position has been shown to increase the accuracy of protein function prediction 25 and has led to the development of tools for protein functional annotation, such as UniProt-DAAC 26 which uses domain architecture comparison and classification for the automatic functional annotation of large protein sets. The systematic assessment and use of domain architectures is enabled by databases containing protein domain information such as UniProt 27, Pfam 28, TIGRFAMs 29, InterPro 30, SMART 31 and PROSITE 32, that also provide graphical view of domain architectures.

Building on these observations we aim at exploring the potential of domain architecture-based (DAB) methods for large scale functional comparative analysis by comparing functionally equivalent sets of proteins, defined using domain architectures, with standard clusters of orthogonal proteins obtained with SB methods. We compared the SB and DAB approach by analysing i) the retrieved number of singletons ( i.e. clusters containing only one protein) and ii) the characteristics of the inferred pan- and core-genome size considering a selection of bacterial genomes (both gram positive and negative) sampled at different taxonomic levels (species, genus, family, order and phylum). We show that the DAB approach provides a fast and efficient alternative to SB methods to identify groups of functionally equivalent/related proteins for comparative genome analysis and that the functional pan-genome is more closed in comparison to the sequence based pan-genome. DAB approaches can complement standardly applied sequence similarity methods and can pinpoint potential functional adaptations.

Methods

Genome sequence retrieval

Bacterial species were chosen on the basis of the availability of fully sequenced genomes in the public domain: two species ( Listeria monocytogenes and Helicobacter pylori), three genera ( Streptococcus, Pseudomonas, Bacillus), one family (Enterobacteriaceae), one order (Corynebacteriales), and one phylum (Cyanobacteria) were selected. For each, 60 genome sequences were considered, except for L. monocytogenes for which only 26 complete genome sequences were available. Maximal diversity among genome sequences was ensured by sampling divergent species (when possible) at each taxonomic level. Genome sequences were retrieved from the European Nucleotide Archive database ( www.ebi.ac.uk/ena). A full list of genomes analyzed is available in the Data availability section.

De novo genome annotation

To avoid bias due to different algorithms used for the annotation of the original deposited genome sequences, all genomes were de novo re-annotated using the SAPP framework (1.0.0) 10. In particular, the FASTA2RDF, GeneCaller (implementing Prodigal (2.6.2) 33) and InterPro (implementing interproscan-5.17-56.0) 34) modules were used to handle, re-annotate the genome sequences and store the results in the RDF data model. This resulted in 446 annotated genomes (7 × 60 genomes + 1 × 26 genomes). For each annotation step the provenance information (E-value cut off, score, originating tool or database) was stored together with annotation information in a graph database (RDF-model) and can be reproduced through the SAPP framework ( http://semantics.systemsbiology.nl).

Retrieval of domain architecture

The positions (start and end on the protein sequence) of domains having Pfam 28, TIGRFAMs 29 and InterPro 30 identifiers were extracted through SPARQL querying of the graph database and domain architectures were retrieved for each protein individually. InterPro aggregates protein domain signatures from different databases. Here no pruning for redundancies has been done. Identification of domains was done using the intrinsic InterPro cut-off that represents in each case the e-values and the scoring systems of the member databases 30. The domain starting position was used to assess relative position in the case of overlapping domains; alphabetic ordering was used to order domains with the same starting position or when the distance between the starting position of overlapping domains was < 3 amino acids.

Labels indicating N-C terminal order of identified domains were assigned to each protein using the starting position of the domains: the same labels were assigned to proteins sharing the same domain architecture.

Sequence similarity based clustering

To make a direct comparison possible only protein sequences containing at least one protein domain signature were considered for analysis. BBH were obtained using Blastp (2.2.28+) with an E-value cutoff of 10 −5 and -max_target_seqs of 10 5. OrthaGogue (1.0.3) 35 combined with MCL (14-137) 36 was used to identify protein clusters on the base of sequence similarity.

Domain architecture based clustering

Domain architecture based clusters were built by clustering proteins with the same labels using bash terminal commands (sort, awk). The number of proteins sharing a given domain architecture in each genome was stored in a 446 × 21054 (genomes × domain architectures) matrix; from this a binarized presence-absence matrix was obtained and used solely for principal component analysis.

Heaps’ law fitting and pan-genome openness assessment

A Heaps’ law model was fit to the abundance matrices using 5 × 10 3 random genome ordering permutations and the micropan R package 37.

Software

SAPP, a Semantic Annotation Pipeline with Provenance which stores results in a graph database 10, used for genome handling and annotation, is available at http://semantics.systemsbiology.nl. Matrix manipulations and multivariate analysis were performed using the R software (3.2.2).

Results

SB and DAB approaches were compared by considering eight sets of genome sequences sampled at different taxonomic levels, from species to order, preserving phylogenetic diversity (see Table 1). Each set contained 60 genome sequences, except for Listeria monocytogenes for which only 26 complete genomes were publicly available. To facilitate the comparison between DAB and SB clusters only protein sequences that contained at least one domain were considered. On average, 85% of the protein sequences contain at least one domain from the InterPro database (see Table 1). Values range from 77±4% for Cyanobacteria to 91 ± 4% for Enterobacteriaceae (which include E. coli). Since the overall results were the same for gram negative and gram positive bacteria, we will show and comment only on results for the latter. Results obtained for gram negative bacteria are shown in the Data availability section.

Table 1. Comparison between DAB and SB clustering.

DAB has been performed using HMM from Pfam (29.0) and InterPro (interproscan-5.17-56.0). Fraction refers to the fraction of proteins with at least one (InterPro or Pfam) protein domain. Core- and pan- indicate the sizes of the core- and pan- genomes (based on the sample) and singletons refers to the number of clusters with only one protein.

| Fraction | DAB | Pfam | DAB | InterPro | SB | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taxon | Name | InterPro | Pfam | Core- | Pan- | Singletons | Core- | Pan- | Singletons | Core- | Pan- | Singletons |

| Species | H. pylori | 0,82 ± 0,01 | 0,81 ± 0,01 | 724 | 1334 | 142 | 534 | 2888 | 853 | 1036 | 1503 | 295 |

| Species | L. monocytogenes | 0,89 ± 0,01 | 0,88 ± 0,02 | 1333 | 2142 | 309 | 1414 | 3415 | 847 | 2294 | 2937 | 746 |

| Genus | Bacillus | 0,87 ± 0,03 | 0,85 ± 0,03 | 792 | 5984 | 1474 | 342 | 16349 | 6745 | 885 | 9903 | 5505 |

| Genus | Pseudomonas | 0,88 ± 0,02 | 0,87 ± 0,02 | 1113 | 6572 | 1554 | 646 | 19387 | 7444 | 1453 | 12204 | 4838 |

| Genus | Streptococcus | 0,87 ± 0,02 | 0,85 ± 0,02 | 535 | 3435 | 845 | 244 | 8265 | 3276 | 716 | 4468 | 2116 |

| Family | Enterobacteriaceae | 0,91 ± 0,04 | 0,90 ± 0,05 | 146 | 6690 | 1664 | 20 | 19590 | 8173 | 197 | 10899 | 6715 |

| Order | Corynebacteriales | 0,83 ± 0,05 | 0,80 ± 0,06 | 475 | 6022 | 1719 | 130 | 22558 | 10554 | 605 | 12632 | 9087 |

| Phylum | Cyanobacteria | 0,77 ± 0,04 | 0,74 ± 0,05 | 400 | 9752 | 4428 | 120 | 27421 | 16140 | 511 | 10575 | 11154 |

Cluster formation based on sequence similarity

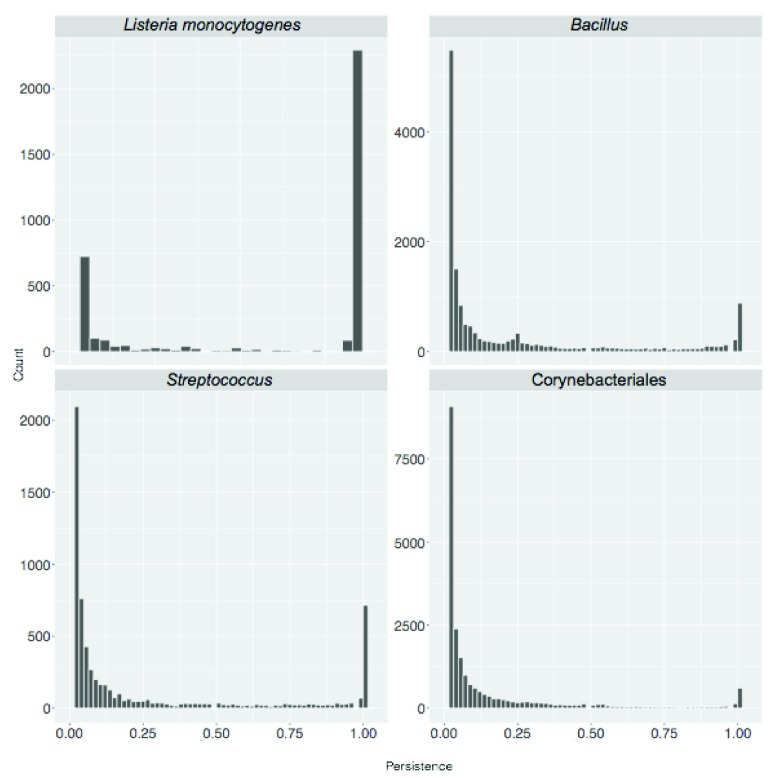

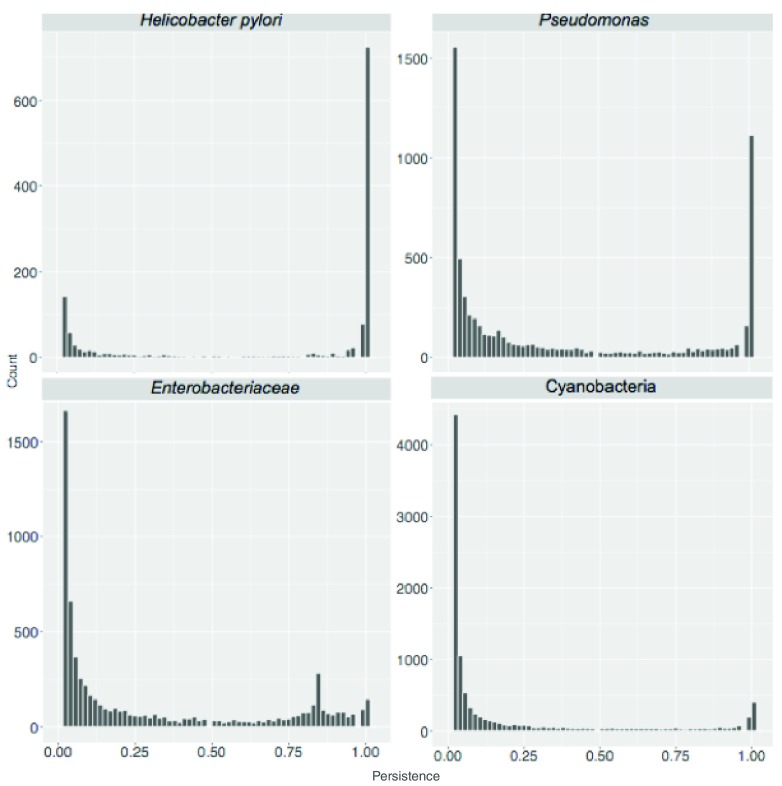

A standard BBH workflow was used to obtain SB protein clusters for the eight sets. We started by calculating the total number of clusters, corresponding to the pan-genome size, as shown in Table 1. Then we considered protein cluster persistence, that is the number of genomes where at least one member of the cluster is present, divided by the total number of genomes considered. Results are shown in Figure 3.

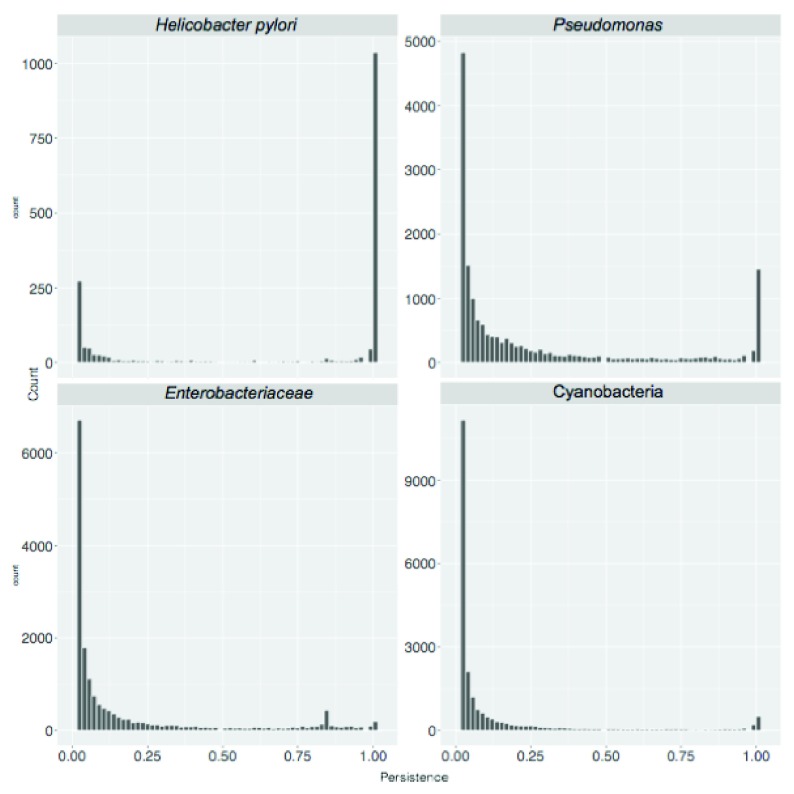

Figure 3. Persistence of sequence similarity based (SB) clusters.

Cluster persistence is defined as the relative number of genomes with at least one protein assigned to the cluster. The frequency of SB clusters according to their persistence is shown.

The ratio between the size of the core-genome (clusters with persistence of 1, i.e. present in all genomes) and the number of singletons decreased with evolutionary distance (see Table 1). It ranged from 3.51 and 3.07 at species level ( H. pylori and L. monocytogenes respectively) to 0.05 and 0.06 when considering members of the same order (Corynebacteriales) and phylum (Cyanobacteria) respectively. A similar pattern is observed when directly comparing the sizes of the pan- and core- genomes of the sampled genomes. Within the gram negative bacteria this ratio ranges from 0.69 for members of the same species ( H. pylori) to 0.05 for members of the same phylum (Cyanobacteria) with intermediate values (0.12) for sequences from the same genus ( Pseudomonas).

Cluster formation based on domain architectures

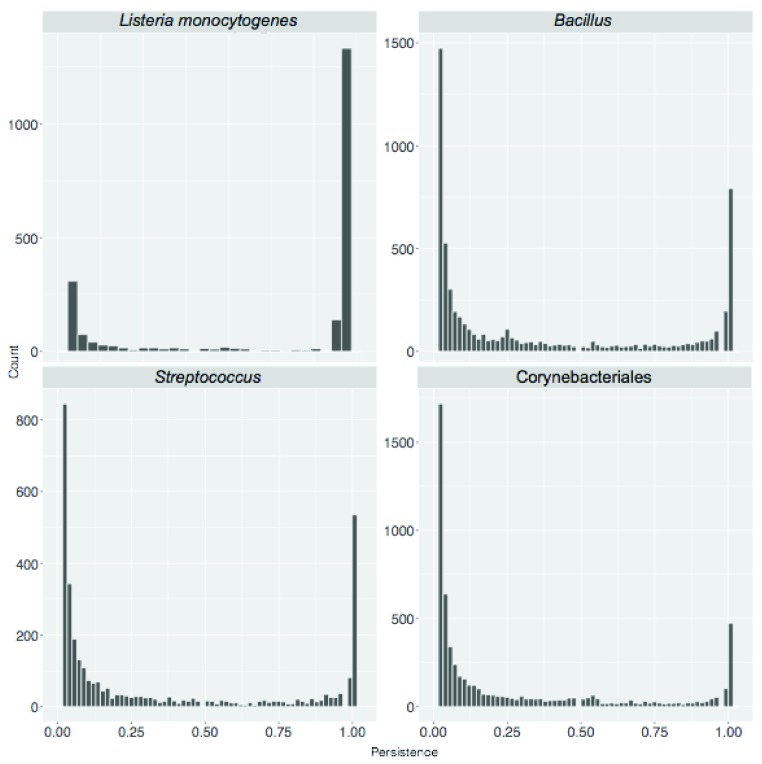

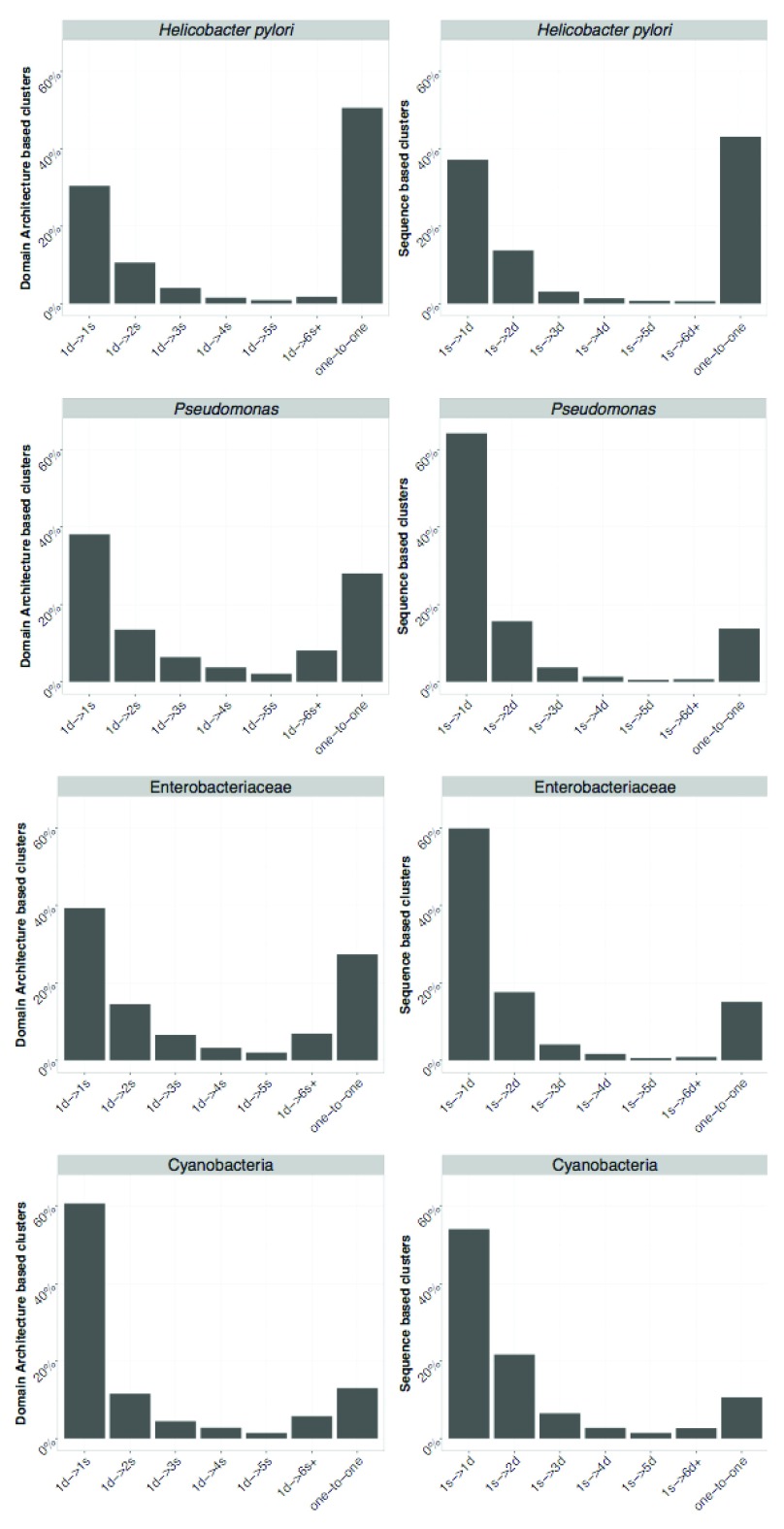

Domain architectures directly rely on the definition of protein domain models: those were retrieved from Pfam, InterPro and TIGRFAMs databases. However, TIGRFAMs results were not further considered because of a lower coverage. As shown in Table 1, as expected partly overlapping results were obtained when different domain databases were used. The number of singletons was larger when using InterPro rather than Pfam and for the latter we also observed larger core-genome size. These discrepancies can be due to the fact InterPro aggregates different resources (including Pfam and TIGRFAMs) and domain signatures arising from different databases are integrated with different identifiers in InterPro. In light of this we focused on results obtained using Pfam whose current release (30.0) contains hidden Markov models for over 16300 domain families. Size and persistence of groups of functionally equivalent proteins obtained using Pfam domains are presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Persistence of domain architecture based (DAB) clusters.

The frequency of DAB clusters according to their persistence is shown.

Similar to what has been observed in the SB case we observed a decrease of the ratio between the size of the core genome and the number of singletons when higher taxonomic levels are considered. For organisms of the same species ( H. pylori and L. monocytogenes) the ratio was 5.09 and 4.30, respectively, while for member of the same order (Corynebacteriales) and phylum (Cyanobacteria) it was 0.55 and 0.009 respectively. Similarly, also the ratio between the size of the core- and pan-genome decreases as higher taxonomic levels are considered, ranging from 0.54 for H. pylori to 0.04 for Cyanobacteria.

Comparison of DAB and SB clusters

We compared the clusters obtained using both approaches and the proteins assigned to them. The number of one-to-one relationships (indicating a complete agreement) between SB and DAB clusters is indicated in Table 2 and ranges from 648 (for H. pylori) to 1680 (in Pseudomonas) corresponding to 50% and 25% of the pan-genome. This indicates that results of SB and DAB clustering tend to be more similar when working at closer phylogenetic distances. However, more complicated cases occur when proteins in a single SB cluster are assigned to various DAB clusters including singletons and vice versa. An overview of the possible mismatches between SB and DAB clusters is in Figure 5. The observed frequency of the different types of cluster mismatches are given in Figure 6. We observed that single domain architectures predominated the one-to-one clusters as shown in Table 3.

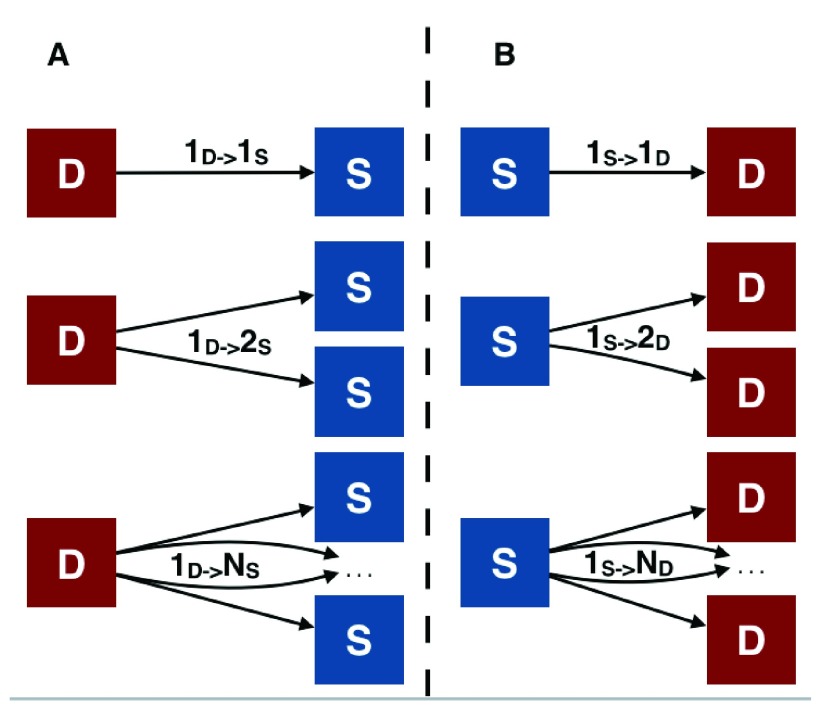

Figure 5. Summary of possible mismatches between DAB and SB clusters.

Mismatches of SB and DAB derived clusters (marked by S and D respectively) can occur in two directions. Panel A: possible cases of mismatch when counting the number of SB clusters the sequences in a DAB cluster are assigned to. 1 d → 1 s denotes that all sequences from the D cluster are assigned to the same S cluster. 1 d → Ns denotes that sequences in a single D cluster are assigned to N distinct S clusters with N ≥ 1. Similarly, (panel B) 1 s → Nd denotes that sequences in a single S cluster are assigned to N distinct D clusters with N ≥ 1.

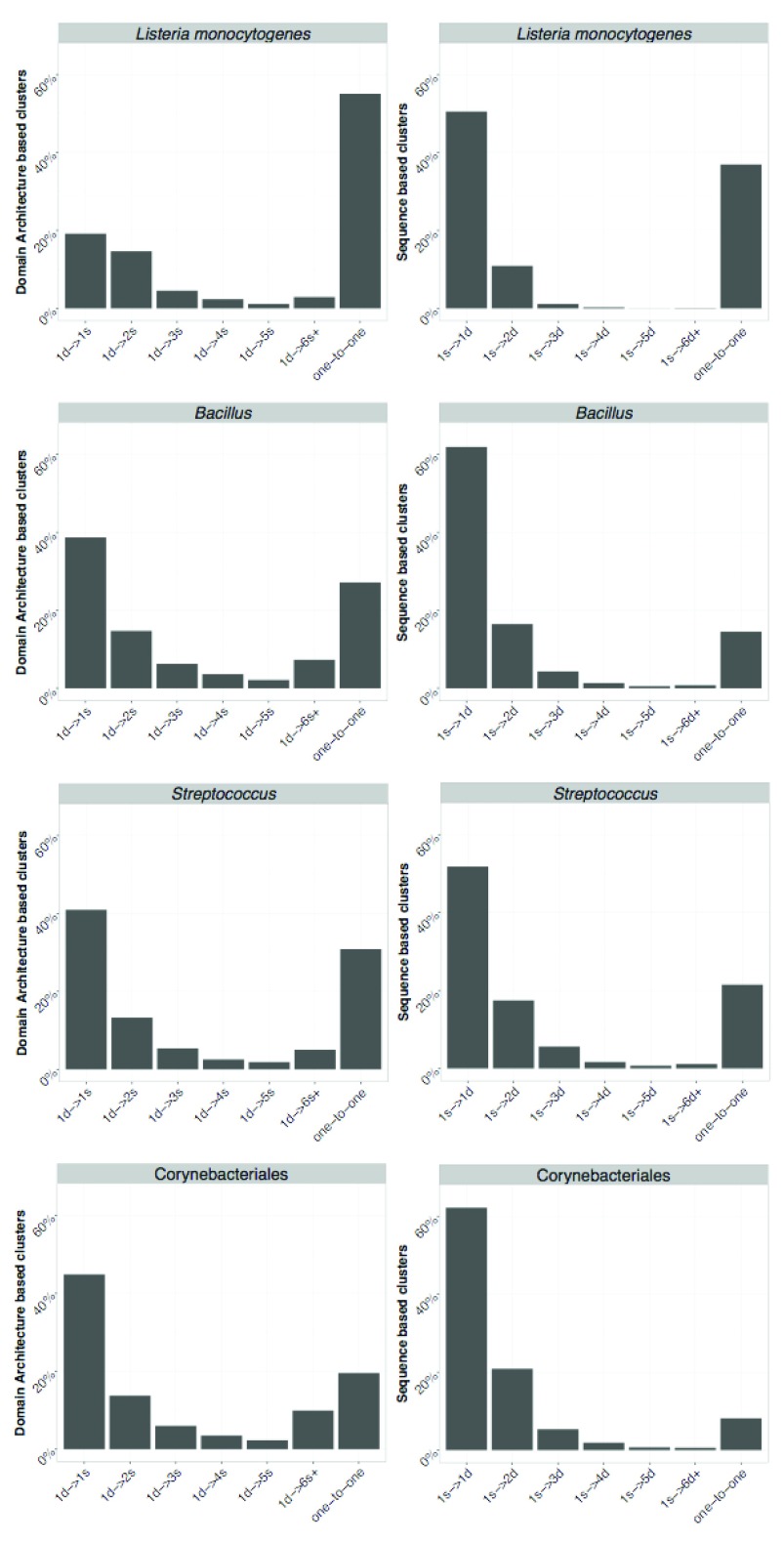

Figure 6. Comparison between DAB and SB clusters.

On the left DAB is used as a reference and each bar represents the relative frequency of one DAB cluster containing sequences assigned to {1, 2, ... , 5} and 6 or more SB clusters and one-to-one represents the relative frequency of identical cluster. Similarly, on the right SB is used as a reference. Axis labels follow notation in Figure 5.

Table 2. Number of identical clusters found with SB and DAB.

| Group | Clusters |

|---|---|

| H. pylori | 648 |

| L. monocytogenes | 1085 |

| Bacillus | 1439 |

| Pseudomonas | 1680 |

| Streptococcus | 961 |

| Enterobacteriaceae | 1649 |

| Corynebacteriales | 1034 |

| Cyanobacteria | 1127 |

For L. monocytogenes we found 378 1 d → 1 s DAB cluster mismatches, ( Figure 5, panel A, top case) meaning that in those cases sequences in a DAB cluster are a subset of the sequences in the corresponding SB cluster. This lower number of sequences in the DAB cluster could be due to, for instance an insertion or expansion of a domain, leading to SB clustered sequences with partly overlapping but distinct domain architectures as is depicted in Figure 1. Similarly, there are 399 1s → 1d clusters. Each of these cases represent a sequence cluster where all the sequences share the same domain architecture, but other sequences exist with the same architecture that have not been included in the cluster due to a too low similarity score. The low similarity between sequences with the same domain architecture could be due to a horizontal acquisition of the gene or to a fast protein evolution at the sequence level. Genes acquired from high phylogenetic distances could greatly vary in sequence while presenting the same domain architecture.

Table 3. Composition in terms of domains (#domains) of domain architectures found within identical (one-to-one) SB and DAB clusters.

| #Domains | H. pylori | L. monocytogenes | Bacillus | Pseudomonas | Streptococcus | Enterobacteriaceae | Cyanobacteria | Corynebacteriales |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 463 | 768 | 1119 | 1185 | 734 | 1312 | 867 | 772 |

| 2 | 133 | 207 | 229 | 333 | 164 | 246 | 182 | 192 |

| 3 | 40 | 76 | 65 | 107 | 43 | 64 | 57 | 45 |

| 4 | 8 | 23 | 18 | 37 | 13 | 15 | 14 | 16 |

| 5 | 3 | 9 | 3 | 10 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 5 |

| 6 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| 7 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Proteins contained in a single DAB cluster but assigned to multiple SB clusters contain mostly ABC transporters-like (PF00005) or Major Facilitator Superfamily (MFS, PF07690) domains. This is not surprising considering that such generic functions are usually associated with a high sequence diversity. Conversely, ABC transporters are found in multiple DAB clusters. However, many of them are grouped into a single SB cluster with ATPase domain containing proteins (1 s → Nd case).

We observed distinct architectures with one of two very similar domains, the GDSL-like Lipase/Acylhydrolase and the GDSL-like Lipase/Acylhydrolase family domain (PF00657 and PF13472 respectively) and those architectures were often seen clustered using a SB approach. However, architectures containing both domains were also identified, pointing to a degree of functional difference as a result of convergent or divergent evolution. Still, the corresponding sequences remain similar enough as to be indistinguishable when a SB approach is used. For SB clustering we also observed the case of identical protein sequences not clustered together, probably because of the tie breaking implementation when BBH are scored.

In all cases we found the size of both the pan- and the core-genome to be larger when a SB approach is used to identify gene clusters and SB approaches lead to a larger number of singletons than DAB ones. This indicates that DAB clusters are assigned to several SB clusters, many of them consisting of just one protein.

When going from species to phylum level, the ratio between the number of DAB and SB singletons changes from 0.48 and 0.41 (for H. pylori and L. monocytogenes respectively) to 0.19 and 0.40 when considering organisms of a higher taxonomic level (Corynebacteriales and Cyanobacteria respectively).

We investigated the predicted size of the pan-genome upon addition of new sequences. Heaps’ law regression can be used to estimate whether the pan-genome is open or closed 38 through the fitting of the decay parameter α; α < 1 indicates openness of the pan-genome (indicating that possibly many clusters remain to be identified within the considered set of sequences), while α > 1 indicates a closed one; the α values are given in Table 4. In all cases the pan-genome is predicted to be open; however, α values obtained using DAB clusters ( α DAB) are systematically closer to one than the α SB obtained with the standard sequence similarity approach.

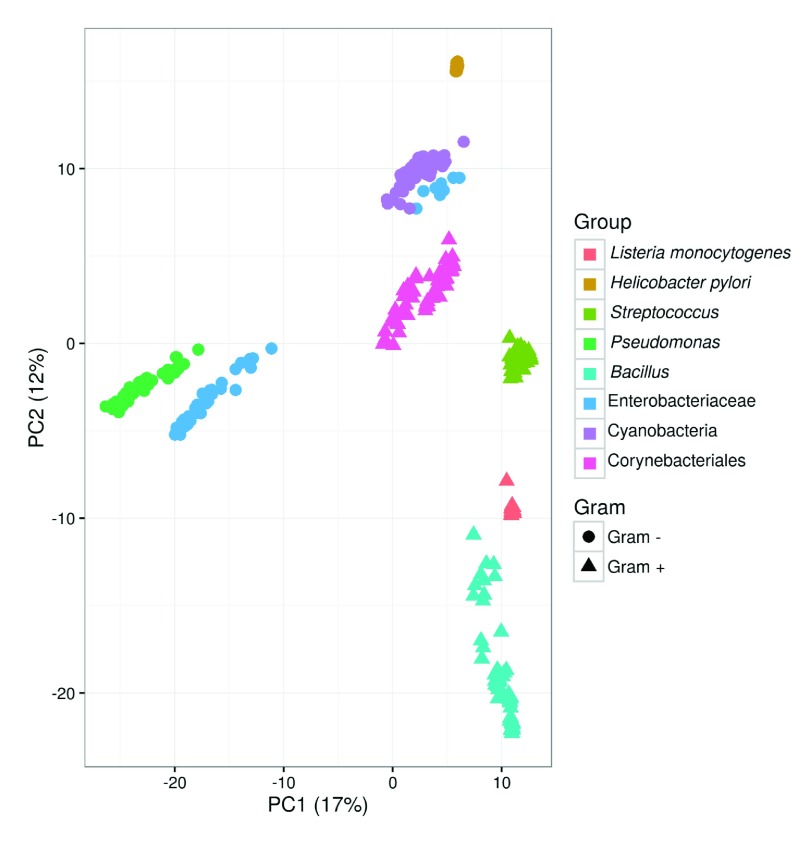

The α DAB value retrieved for L. monocytogenes is strikingly low. Heaps law regression relies on the selected genomes providing a uniform sampling of selected taxon, here species. Analysis of the domain content of the selected genomes shows a divergent behaviour of strain LA111 (genome id GCA_000382925-1). This behaviour is clear in Figure 7, where GCA_000382925-1 appears as an outlier of the L. monocytogenes group. Removal of these outlier leads to α DAB = 1.04 and α SB = 0.64, which emphasizes the need for uniform sampling prior to Heaps regression analysis.

Figure 7. Large scale functional comparison of species.

Principal component analysis of functional similarities of 446 genomes based on the presence/absence of domain architectures on the corresponding genomes. The variance explained by the first two components is indicated on axes labels.

Table 4. Decay parameter α of the Heaps regression model using DAB and SB clustering.

| α DAB | α SB | |

|---|---|---|

| H. pylori | 0.95 | 0.42 |

| L. monocytogenes | 0.77 (1.04 *) | 0.50 (0.64 *) |

| Bacillus | 0.93 | 0.59 |

| Pseudomonas | 0.94 | 0.61 |

| Streptococcus | 0.87 | 0.72 |

| Enterobacteriaceae | 0.99 | 0.74 |

| Cyanobacteria | 0.64 | 0.58 |

| Corynebacteriales | 0.88 | 0.52 |

α < 1 indicates an open pan-genome.

*Values obtained upon removal of sequence GCA_000382925-1

DAB comparison across multiple taxa

DAB clusters can be labelled by their domain architecture and since this is a formal description of functional equivalence, results of independently obtained analyses can be combined. Figure 7 shows the results of a principal component analysis of the combined DAB clusters for selected genomes from eight taxa. The first two components account for a relatively low explained variance (29%) still grouping of genomes from the same taxa is apparent. High functional similarity among genomes of the same species ( H. pylori and L. monocytogenes) is reflected by the compact clustering, while phylogenetically more distant genomes appear scattered in the functional space defined by the principal components.

Discussion

We have shown that domain architecture-based methods can be used as an effective approach to identify clusters of functionally equivalent proteins, leading to results similar to those obtained by classical methods based on sequence similarity.

To assess whether DAB results were consistent with those of SB methods we chosen OrthaGogue as a representative of the latter class. Several tools such as COGNITOR 39 and MultiPARANOID 40 are available that implement different algorithm solutions to identify homologous sequences; however, despite different implementations, they all rely on sequence similarity as a proxy for functional equivalence. Here we considered SB methods as a golden standard for functional comparative genomics, especially when organisms within close evolutionary proximity are considered. Our aim was to investigate whether using domain architectures instead of sequence similarity alone would yield similar results, thereby justifying their use for large scale functional genome comparisons. Regarding domain architectures, we have explored different alternatives, as we have seen that the chosen database or set of reference domains plays a critical role; for example, the low coverage of TIGRFAM prevents the obtaining of reasonable clusters. The DAB approach takes advantage of the large computational effort that has already been devoted to the identification and definition of protein domains in dedicated databases such as Pfam. Protein domain models are built using large scale sequence comparisons which is an extremely computationally intensive task. However, once the domain models are defined, mining a sequence for domain occurrences is much less demanding task. Indeed, the task with the higher computational load (the definition of the domains) is performed only once and results can be stored and re-used for further analysis. This provides an effective scalable approach for large scale functional comparisons which by and large is independent of phylogenetic distances between species.

The chosen set of domain models and the database used as a reference greatly impact the results. InterPro aggregates protein domain signatures from different databases, which leads to redundancy of the domain models. This redundancy causes overlaps between the entries and an increase of the granularity of the clusters retrieved: this can bias downwards the size of the pan-genome and upwards the size of the core- genome, as shown in Table 1. In InterPro this redundancy is taken into account by implementing a hierarchy of protein families and domains. The entries at the top of these hierarchies correspond to broad families or domains that share higher level structure and/or function; the entries at the bottom correspond to specific functional subfamilies or structural /functional subclasses of domains 30. Using Inter-Pro for DAB clustering would require taking into account the hierarchy of protein families and domains: however, this would pose challenges of its own and would require discrimination of the functional equivalence of different signatures within the same hierarchy.

Another source of redundancy are functionally equivalent domains from distantly related sequences. Pfam represents this through related families, termed clans, where relationships may be defined by similarity of sequence, structure or profile-HMM. Clans might contain functionally equivalent domains, however it is not clear whether this is always the case as the criteria for clan definition includes functional similarity but not functional equivalence 41.

Members of a clan have diverging sequences and very often SB approaches would recognize the evolutionary distance between the sequences and group them in different clusters. If we were to assume that members of a clan are functionally equivalent and collect them in the same DA cluster, we will have a higher number of cases where a single DA cluster is split in multiple sequence clusters 1d→Ns. Also there would be higher number of cases of sequence clusters with the same DA but no exactly matching the DA clusters (1s→1d cases).

In many cases a one-to-one correspondence could be established between DAB and SB clusters indicating that often the sequence can be used as a proxy for function. At first this may seem a trivial result but it has a profound implication: domain model databases (in this case Pfam) contain enough information, encoded by known domain models, to represent the quasi totality of biological function encoded in the bacterial sequences analyzed here. However, it is important to stress that the comparisons have been performed considering sequences with known domains, representing currently around 85% of the genome coding content, a number that will only increase in the future.

A significant advantage of the DAB method over the SB method is that the domain architecture captured within a cluster can be used as a formal description of the function. Currently, more than 20% of all separable domains in the Pfam database, are so-called domains of unknown function (DUFs). Despite this, in bacterial species they are often essential 42. With the DAB method they are formally included and often semantically linked to one or more domains of known function.

The starting position of the domains was used to generate labels indicating N-C terminal order of identified domains. The labels were used only for clustering as proteins sharing the same labels were assigned to the same clusters. Choosing instead the mid-point or the C-terminal position could affect the labeling but not the obtained clusters.

A content-wise formal labeling of DAB clusters makes a seamless integration of multiple independently performed DAB analysis possible. This allows for a comparison of potential functionomes across taxonomic boundaries, as presented in Figure 7, while new genomes can be added at a computational cost O( n), with n the number of genomes to be analyzed. SB methods that create orthologous groups require more memory and time as they come at an O( n 2) computational cost. Other SB approaches, such as COGNITOR, reduce the computational costs to O( n) by using pre-computed databases. In this respect, the DAB approach is similar to the approach implemented in COGNITOR, by searching against existing databases of domains architectures. In this way the DAB approach leverages the extensive amount of work already put into defining domain families.

The bimodal shape of the distributions presented in Figure 3 and Figure 4 indicates the relative role of horizontal gene transfer and vertical descent when shaping bacterial genomes: the first peak accounts for sequences (or functions) only present in a small number of genome sequences which have been a likely acquired by horizontal gene transfer. The second peak accounts for high persistence genetic regions representing genes (or functions) belonging to the taxon core which have been likely acquired by vertical descent.

A measure of the impact of vertical descent and horizontal gene transfer is provided by the ratio between the core- and pan- genome sizes. The number of singletons provides a measure of the number of genes horizontally acquired from species outside the considered group.

Two of the most prominent differences between the two approaches are the number of retrieved singletons and the core- to pan-genome size ratio. Multiple members of the same taxon might acquire the same function through horizontal gene transfer 43. This is likely to occur given that they would have similar physiological characteristics, hence they would tend to occupy a similar niche or, at least, more similar than when comparing species from different taxa. As the origin of the horizontally acquired genes may vary for each organism, an SB approach will correctly recognize the heterologous origin of the corresponding sequences and those will be assigned to singletons. However, the probabilistic hidden Markov models used for domain recognition are better at recognizing the functional similarity of the considered sequences and clusters them together.

Another indication of the relative impact of horizontal and vertical gene acquisition events is provided by the openness or closedness of the genome. Values for the decay parameter α in Table 3 indicate a relatively large impact of horizontal gene transfer. Within the considered taxa we observed α DAB > α SB, meaning that the sequence diversity is larger than the functional diversity: upon addition of new genomes to the sample the rate of addition of new sequence clusters appears higher than the rate of addition of new functions.

Limitations of DAB approaches

We have shown that domain architecture-based methods can be used as an effective approach to identify clusters of functionally equivalent proteins, leading to results similar to those obtained by classical methods based on sequence similarity. However, whether DAB methods are more accurate than SB methods to assess functional equivalence will require further analysis. In this light, results of functional conservation for both approaches could be compared in terms of GO similarity and/or EC number 44, 45. Partial domain hits might arise as a result of alignment, annotation and sequence assembly artefacts. To reduce the number of partial domain hits additional pruning could be implemented to distinguish these cases. However, this is an open problem that requires caution as it could influence the functional capacity of an organism and clustering approaches using DA.

The performance of DAB methods may be sub-optimal when dealing with newly sequenced genomes that are not yet well-characterized enough to have all of their domains present in domain databases, since DAB methods will be unable to handle unknown architectural types. Around 15% of the genome coding content corresponds to sequences with no identified protein domains. DAB approaches can be complemented with SB methods to consider these sequences or even protein sequences with low domain coverage, possible indicating the location of protein domains yet to be identified. Since DAB methods rely on the constant upgrading of public resources like UniProt and Pfam databases, an initial assessment of domain coverage appears as a sine qua non condition for application of these methods. DAB approaches could be used to assess the consistency of existing orthologous groups in terms of their domain architectures, at least when domain architectures are expected to be completely known in advance (for instance in the case of micro-evolutionary variations within a species where mutational events may disrupt a protein’s function). For other purposes, such as the discovery of a new phyla of cellular life that contains radically different domain architectures, global similarity methods may be preferred 45.

Conclusions

As protein domain databases have evolved to the point where DAB and SB approaches produce similar results in closely related organisms, the DAB approach provides a fast and efficient alternative to SB methods to identify groups of functionally equivalent/related proteins for comparative genome analysis. The lower computational cost of DAB approaches makes them the better choice for large scale comparisons involving hundreds of genomes.

Highly redundant databases, such as InterPro, are best suited for domain based protein annotation, but are not effective for DAB clustering if the goal is to identify clusters of functionally equivalent proteins. To enable DAB approaches for highly structured databases, such as Inter-Pro, the hierarchy of protein families and domains within has to be explicitly considered. Currently Pfam is for this task a better alternative.

Differences between DAB and SB approaches increase when the goal is to study bacterial groups spanning wider evolutionary distances. The functional pan-genome is more closed in comparison to the sequence based pan-genome. Both methods have a distinct approach towards horizontally transferred genes, and the DAB approach has the potential to detect functional equivalence even when sequence similarities are low.

Complementing the standardly applied sequence similarity methods with a DAB approach pinpoints potential functional protein adaptations that may add to the overall fitness.

Data availability

The data referenced by this article are under copyright with the following copyright statement: Copyright: © 2017 Koehorst JJ et al.

Data associated with the article are available under the terms of the Creative Commons Zero "No rights reserved" data waiver (CC0 1.0 Public domain dedication). http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/

List of genomes used for the analysis at different phylogenetic levels. The genomes are grouped per taxonomic lineage used in this study.

Bacillus

GCA_000523045 Bacillus subtilis BEST7003

GCA_000782835 Bacillus subtilis

GCA_000832885 Bacillus thuringiensis str. Al Hakam

GCA_000473245 Bacillus infantis NRRL B-14911

GCA_000832585 Bacillus anthracis

GCA_000590455 Bacillus pumilus

GCA_000831065 Bacillus bombysepticus

GCA_000833275 Bacillus anthracis str. Turkey32

GCA_000952895 Bacillus sp.

GCA_000259365 Bacillus sp. JS

GCA_000143605 Bacillus cereus biovar anthracis str. CI

GCA_000186745 Bacillus subtilis BSn5

GCA_000987825 Bacillus methylotrophicus

GCA_000706725 Bacillus lehensis G1

GCA_000815145 Bacillus sp. Pc3

GCA_000496285 Bacillus toyonensis BCT-7112

GCA_000742855 Bacillus mycoides

GCA_000169195 Bacillus coagulans 36D1

GCA_000835145 Bacillus amyloliquefaciens KHG19

GCA_000321395 Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis str. BSP1

GCA_000009045 Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis str. 168

GCA_000293765 Bacillus subtilis QB928

GCA_000025805 Bacillus megaterium DSM 319

GCA_000747345 Bacillus sp. X1(2014)

GCA_000833005 Bacillus amyloliquefaciens

GCA_000408885 Bacillus paralicheniformis ATCC 9945a

GCA_000742895 Bacillus anthracis str. Vollum

GCA_000829195 Bacillus sp. OxB-1

GCA_000800825 Bacillus sp. WP8

GCA_000706705 Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis str. OH 131.1

GCA_000338735 Bacillus subtilis XF-1

GCA_000832445 Bacillus anthracis

GCA_000747335 Bacillus anthracis

GCA_000008505 Bacillus thuringiensis serovar konkukian str. 97-27

GCA_000195515 Bacillus amyloliquefaciens TA208

GCA_000209795 Bacillus subtilis subsp. natto BEST195

GCA_000017425 Bacillus cytotoxicus NVH 391-98

GCA_000877815 Bacillus sp. YP1

GCA_000177235 Bacillus cellulosilyticus DSM 2522

GCA_000344745 Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis 6051-HGW

GCA_000227485 Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis str. RO-NN-1

GCA_000494835 Bacillus amyloliquefaciens CC178

GCA_000011145 Bacillus halodurans C-125

GCA_000724485 Bacillus methanolicus MGA3

GCA_000018825 Bacillus weihenstephanensis KBAB4

GCA_000005825 Bacillus pseudofirmus OF4

GCA_000017885 Bacillus pumilus SAFR-032

GCA_000583065 Bacillus methylotrophicus Trigo-Cor1448

GCA_000349795 Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis str. BAB-1

GCA_000306745 Bacillus thuringiensis Bt407

GCA_000011645 Bacillus licheniformis DSM 13 = ATCC 14580

GCA_000497485 Bacillus subtilis PY79

GCA_000009825 Bacillus clausii KSM-K16

GCA_000227465 Bacillus subtilis subsp. spizizenii TU-B-10

GCA_000971925 Bacillus subtilis KCTC 1028

GCA_000972245 Bacillus endophyticus

GCA_000242895 Bacillus sp. 1NLA3E

GCA_000832485 Bacillus thuringiensis

GCA_000830075 Bacillus atrophaeus

GCA_000146565 Bacillus subtilis subsp. spizizenii str. W23

Corynebacteriales

GCA_000016005 Mycobacterium sp. JLS

GCA_000758405 Mycobacterium abscessus subsp. bolletii

GCA_000283295 Mycobacterium smegmatis str. MC2 155

GCA_001021045 Corynebacterium testudinoris

GCA_000341345 Corynebacterium halotolerans YIM 70093 = DSM 44683

GCA_000525655 Corynebacterium falsenii DSM 44353

GCA_000255195 Corynebacterium diphtheriae HC04

GCA_000523235 Nocardia nova SH22a

GCA_000026685 Mycobacterium leprae Br4923

GCA_000980815 Corynebacterium camporealensis

GCA_000328565 Mycobacterium sp. JS623

GCA_000015405 Mycobacterium sp. KMS

GCA_000987865 [Brevibacterium] flavum

GCA_001020985 Corynebacterium mustelae

GCA_001021065 Corynebacterium uterequi

GCA_000177535 Corynebacterium resistens DSM 45100

GCA_000011305 Corynebacterium efficiens YS-314

GCA_000835265 Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis

GCA_000739455 Corynebacterium imitans

GCA_000831265 Mycobacterium kansasii 662

GCA_000819445 Corynebacterium humireducens NBRC 106098 = DSM 45392

GCA_000770235 Mycobacterium avium subsp. avium

GCA_000980835 Corynebacterium kutscheri

GCA_000010225 Corynebacterium glutamicum R

GCA_000590555 Corynebacterium argentoratense DSM 44202

GCA_000247715 Gordonia polyisoprenivorans VH2

GCA_000416365 Mycobacterium sp. VKM Ac-1817D

GCA_000418365 Corynebacterium terpenotabidum Y-11

GCA_000092225 Tsukamurella paurometabola DSM 20162

GCA_000442645 Corynebacterium maris DSM 45190

GCA_000277125 Mycobacterium intracellulare ATCC 13950

GCA_000196695 Rhodococcus equi 103S

GCA_000828995 Mycobacterium tuberculosis str. Kurono

GCA_000006605 Corynebacterium jeikeium K411

GCA_000022905 Corynebacterium aurimucosum

GCA_001021025 Corynebacterium epidermidicanis

GCA_000010105 Rhodococcus erythropolis PR4

GCA_000092825 Segniliparus rotundus DSM 44985

GCA_000758245 Mycobacterium bovis

GCA_000184435 Mycobacterium gilvum Spyr1

GCA_000829075 Mycobacterium avium subsp. hominissuis TH135

GCA_000214175 Amycolicicoccus subflavus DQS3-9A1

GCA_000769635 Corynebacterium ulcerans

GCA_000626675 Corynebacterium glyciniphilum AJ 3170

GCA_001026945 Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis

GCA_000026445 Mycobacterium liflandii 128FXT

GCA_000013925 Mycobacterium ulcerans Agy99

GCA_000954115 Rhodococcus sp. B7740

GCA_000143885 Gordonia sp. KTR9

GCA_000014565 Rhodococcus jostii RHA1

GCA_000179395 Corynebacterium variabile DSM 44702

GCA_000732945 Corynebacterium atypicum

GCA_000723425 Mycobacterium marinum E11

GCA_000230895 Mycobacterium rhodesiae NBB3

GCA_000344785 Corynebacterium callunae DSM 20147

GCA_000010805 Rhodococcus opacus B4

GCA_000982715 Rhodococcus aetherivorans

GCA_000298095 Mycobacterium indicus pranii MTCC 9506

GCA_000833575 Corynebacterium singulare

GCA_000023145 Corynebacterium kroppenstedtii DSM 44385

Cyanobacteria

GCA_000317085 Synechococcus sp. PCC 7502

GCA_000011385 Gloeobacter violaceus PCC 7421

GCA_000014585 Synechococcus sp. CC9311

GCA_000012465 Prochlorococcus marinus str. NATL2A

GCA_000737535 Synechococcus sp. KORDI-100

GCA_000013205 Synechococcus sp. JA-3-3Ab

GCA_000021825 Cyanothece sp. PCC 7424

GCA_000063505 Synechococcus sp. WH 7803

GCA_000022045 Cyanothece sp. PCC 7425

GCA_000316575 Calothrix sp. PCC 7507

GCA_000316685 Synechococcus sp. PCC 6312

GCA_000012505 Synechococcus sp. CC9902

GCA_000317475 Oscillatoria nigro-viridis PCC 7112

GCA_000063525 Synechococcus sp. RCC307

GCA_000317695 Anabaena cylindrica PCC 7122

GCA_000014265 Trichodesmium erythraeum IMS101

GCA_000817325 Synechococcus sp. UTEX 2973

GCA_000737575 Synechococcus sp. KORDI-49

GCA_000317125 Chroococcidiopsis thermalis PCC 7203

GCA_000017845 Cyanothece sp. ATCC 51142

GCA_000020025 Nostoc punctiforme PCC 73102

GCA_000018105 Acaryochloris marina MBIC11017

GCA_000757865 Prochlorococcus sp. MIT 0801

GCA_000317045 Geitlerinema sp. PCC 7407

GCA_000012625 Synechococcus sp. CC9605

GCA_000737595 Synechococcus sp. KORDI-52

GCA_000317635 Halothece sp. PCC 7418

GCA_000025125 Candidatus Atelocyanobacterium thalassa isolate ALOHA

GCA_000010625 Microcystis aeruginosa NIES-843

GCA_000317065 Pseudanabaena sp. PCC 7367

GCA_000312705 Anabaena sp. 90

GCA_000316515 Cyanobium gracile PCC 6307

GCA_000316605 Leptolyngbya sp. PCC 7376

GCA_000317025 Pleurocapsa sp. PCC 7327

GCA_000009705 Nostoc sp. PCC 7120

GCA_000013225 Synechococcus sp. JA-2-3B’a(2–13)

GCA_000757845 Prochlorococcus sp. MIT 0604

GCA_000317515 Microcoleus sp. PCC 7113

GCA_000734895 Calothrix sp. 336/3

GCA_000007925 Prochlorococcus marinus subsp. marinus str. CCMP1375

GCA_000021805 Cyanothece sp. PCC 8801

GCA_000019485 Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002

GCA_000317655 Cyanobacterium stanieri PCC 7202

GCA_000316625 Nostoc sp. PCC 7107

GCA_000011465 Prochlorococcus marinus subsp. pastoris str. CCMP1986

GCA_000316665 Rivularia sp. PCC 7116

GCA_000317105 Oscillatoria acuminata PCC 6304

GCA_000317435 Calothrix sp. PCC 6303

GCA_000317555 Gloeocapsa sp. PCC 7428

GCA_000478825 Synechocystis sp. PCC 6714

GCA_000204075 Anabaena variabilis ATCC 29413

GCA_000317575 Stanieria cyanosphaera PCC 7437

GCA_000161795 Synechococcus sp. WH 8109

GCA_000011345 Thermosynechococcus elongatus BP-1

GCA_000317615 Dactylococcopsis salina PCC 8305

GCA_000284135 Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 substr. GT-I

GCA_000024045 Cyanothece sp. PCC 8802

GCA_000317495 Crinalium epipsammum PCC 9333

GCA_000317675 Cyanobacterium aponinum PCC 10605

GCA_000012525 Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942

Enterobacteriaceae

GCA_000259175 Providencia stuartii MRSN 2154

GCA_000214805 Serratia sp. AS13

GCA_000330865 Serratia marcescens FGI94

GCA_001010285 Photorhabdus temperata subsp. thracensis

GCA_000364725 Candidatus Moranella endobia PCVAL

GCA_000521525 Buchnera aphidicola str. USDA (Myzus persicae)

GCA_000517405 Candidatus Sodalis pierantonius str. SOPE

GCA_000012005 Shigella dysenteriae Sd197

GCA_000196475 Photorhabdus asymbiotica

GCA_000750295 Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Enteritidis

GCA_000007885 Yersinia pestis biovar Microtus str. 91001

GCA_000739495 Klebsiella pneumoniae

GCA_000252995 Salmonella bongori NCTC 12419

GCA_000270125 Pantoea ananatis AJ13355

GCA_000215745 Enterobacter aerogenes KCTC 2190

GCA_000092525 Shigella sonnei Ss046

GCA_000020865 Edwardsiella tarda EIB202

GCA_000023545 Dickeya dadantii Ech703

GCA_000238975 Serratia symbiotica str. ’Cinara cedri’

GCA_000975245 Serratia liquefaciens

GCA_000006645 Yersinia pestis KIM10+

GCA_000224675 Enterobacter asburiae LF7a

GCA_000007405 Shigella flexneri 2a str. 2457T

GCA_001022275 Citrobacter freundii

GCA_000963575 Klebsiella michiganensis

GCA_000504545 Cronobacter sakazakii CMCC 45402

GCA_000012025 Shigella boydii Sb227

GCA_000814125 Enterobacter cloacae

GCA_000987925 Yersinia enterocolitica

GCA_000011745 Candidatus Blochmannia pennsylvanicus str. BPEN

GCA_000255535 Rahnella aquatilis HX2

GCA_000952955 Escherichia coli

GCA_000695995 Serratia sp. FS14

GCA_000648515 Citrobacter freundii CFNIH1

GCA_001022295 Klebsiella oxytoca

GCA_000147055 Dickeya dadantii 3937

GCA_000348565 Edwardsiella piscicida C07-087

GCA_000742755 Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae

GCA_000027225 Xenorhabdus bovienii SS-2004

GCA_000247565 Wigglesworthia glossinidia endosymbiont of Glossina morsitans morsitans (Yale colony)

GCA_000828815 Candidatus Tachikawaea gelatinosa

GCA_000022805 Yersinia pestis D106004

GCA_001006005 Serratia fonticola

GCA_000018625 Salmonella enterica subsp. arizonae serovar 62:z4,z23:-

GCA_000478905 Candidatus Pantoea carbekii

GCA_000410515 Enterobacter sp. R4-368

GCA_000148935 Pantoea vagans C9-1

GCA_000444425 Proteus mirabilis BB2000

GCA_000747565 Serratia sp. SCBI

GCA_001022135 Kluyvera intermedia

GCA_000757825 Cedecea neteri

GCA_000294535 Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. carotovorum PCC21

GCA_000834375 Yersinia pseudotuberculosis YPIII

GCA_000043285 Candidatus Blochmannia floridanus

GCA_000093065 Candidatus Riesia pediculicola USDA

GCA_000834515 Yersinia intermedia

GCA_000759475 Pantoea rwandensis

GCA_000027065 Siccibacter turicensis z3032

GCA_000582515 Yersinia similis

GCA_000300455 Kosakonia sacchari SP1

Helicobacter pylori

GCA_000148855 Helicobacter pylori SJM180

GCA_000021165 Helicobacter pylori G27

GCA_000185245 Helicobacter pylori SouthAfrica7

GCA_000093185 Helicobacter pylori v225d

GCA_000277365 Helicobacter pylori Shi417

GCA_000498315 Helicobacter pylori BM012A

GCA_000270065 Helicobacter pylori F57

GCA_000392455 Helicobacter pylori UM032

GCA_000277385 Helicobacter pylori Shi169

GCA_000008525 Helicobacter pylori 26695

GCA_000270045 Helicobacter pylori F32

GCA_000148915 Helicobacter pylori Sat464

GCA_000185225 Helicobacter pylori Lithuania75

GCA_000600045 Helicobacter pylori oki102

GCA_000600205 Helicobacter pylori oki828

GCA_000192335 Helicobacter pylori 2018

GCA_000827025 Helicobacter pylori

GCA_000590775 Helicobacter pylori SouthAfrica20

GCA_000270025 Helicobacter pylori F30

GCA_000148665 Helicobacter pylori 908

GCA_000392515 Helicobacter pylori UM037

GCA_000392475 Helicobacter pylori UM299

GCA_000262655 Helicobacter pylori XZ274

GCA_000008785 Helicobacter pylori J99

GCA_000685745 Helicobacter pylori

GCA_000185205 Helicobacter pylori Gambia94/24

GCA_000826985 Helicobacter pylori 26695-1

GCA_000315955 Helicobacter pylori Aklavik117

GCA_000498335 Helicobacter pylori BM012S

GCA_000277405 Helicobacter pylori Shi112

GCA_000224535 Helicobacter pylori Puno120

GCA_000317875 Helicobacter pylori Aklavik86

GCA_000600185 Helicobacter pylori oki673

GCA_000196755 Helicobacter pylori B8

GCA_000439295 Helicobacter pylori UM298

GCA_000348885 Helicobacter pylori OK310

GCA_000307795 Helicobacter pylori 26695

GCA_000013245 Helicobacter pylori HPAG1

GCA_000392535 Helicobacter pylori UM066

GCA_000185185 Helicobacter pylori India7

GCA_000213135 Helicobacter pylori 83

GCA_000685705 Helicobacter pylori

GCA_000224575 Helicobacter pylori SNT49

GCA_000600085 Helicobacter pylori oki112

GCA_000023805 Helicobacter pylori 52

GCA_000348865 Helicobacter pylori OK113

GCA_000259235 Helicobacter pylori HUP-B14

GCA_000020245 Helicobacter pylori Shi470

GCA_000270005 Helicobacter pylori F16

GCA_000192315 Helicobacter pylori 2017

GCA_000685665 Helicobacter pylori

GCA_000600165 Helicobacter pylori oki422

GCA_000255955 Helicobacter pylori ELS37

GCA_000021465 Helicobacter pylori P12

GCA_000600145 Helicobacter pylori oki154

GCA_000224555 Helicobacter pylori Puno135

GCA_000011725 Helicobacter pylori 51

GCA_000148895 Helicobacter pylori Cuz20

GCA_000817025 Helicobacter pylori

GCA_000178935 Helicobacter pylori 35A

Listeria monocytogenes

GCA_000438745 Listeria monocytogenes

GCA_000438705 Listeria monocytogenes

GCA_001027125 Listeria monocytogenes

GCA_000438725 Listeria monocytogenes

GCA_000197755 Listeria monocytogenes

GCA_001027245 Listeria monocytogenes

GCA_001027085 Listeria monocytogenes

GCA_001005925 Listeria monocytogenes

GCA_000746625 Listeria monocytogenes

GCA_000382925 Listeria monocytogenes

GCA_000438665 Listeria monocytogenes

GCA_000800335 Listeria monocytogenes

GCA_001027165 Listeria monocytogenes

GCA_000438605 Listeria monocytogenes

GCA_000438585 Listeria monocytogenes

GCA_000808055 Listeria monocytogenes

GCA_000950775 Listeria monocytogenes

GCA_001027065 Listeria monocytogenes

GCA_000600015 Listeria monocytogenes

GCA_001027205 Listeria monocytogenes

GCA_000438685 Listeria monocytogenes

GCA_001005985 Listeria monocytogenes

GCA_000438625 Listeria monocytogenes

GCA_000681515 Listeria monocytogenes

GCA_000438645 Listeria monocytogenes

GCA_000210815 Listeria monocytogenes

Pseudomonas

GCA_000829885 Pseudomonas aeruginosa

GCA_000510285 Pseudomonas monteilii SB3078

GCA_000988485 Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae B301D

GCA_000013785 Pseudomonas stutzeri A1501

GCA_000759535 Pseudomonas cremoricolorata

GCA_000953455 Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes

GCA_000981825 Pseudomonas aeruginosa

GCA_000661915 Pseudomonas stutzeri

GCA_000508205 Pseudomonas sp. TKP

GCA_000014625 Pseudomonas aeruginosa UCBPP-PA14

GCA_000019445 Pseudomonas putida W619

GCA_000316175 Pseudomonas sp. UW4

GCA_000498975 Pseudomonas mosselii SJ10

GCA_000473745 Pseudomonas aeruginosa VRFPA04

GCA_000691565 Pseudomonas putida

GCA_000730425 Pseudomonas fluorescens

GCA_000007805 Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato str. DC3000

GCA_000349845 Pseudomonas denitrificans ATCC 13867

GCA_000026105 Pseudomonas entomophila L48

GCA_000689415 Pseudomonas knackmussii B13

GCA_000325725 Pseudomonas putida HB3267

GCA_000412695 Pseudomonas resinovorans NBRC 106553

GCA_000831585 Pseudomonas plecoglossicida

GCA_000756775 Pseudomonas sp. 20_BN

GCA_000590475 Pseudomonas stutzeri

GCA_000829255 Pseudomonas aeruginosa

GCA_000761155 Pseudomonas rhizosphaerae

GCA_001038645 Pseudomonas stutzeri

GCA_000264665 Pseudomonas putida ND6

GCA_000007565 Pseudomonas putida KT2440

GCA_000494915 Pseudomonas sp. VLB120

GCA_000226155 Pseudomonas aeruginosa M18

GCA_000213805 Pseudomonas fulva 12-X

GCA_000194805 Pseudomonas brassicacearum subsp. brassicacearum NFM421

GCA_000336465 Pseudomonas poae RE*1-1-14

GCA_000828695 Pseudomonas protegens Cab57

GCA_000800255 Pseudomonas parafulva

GCA_000257545 Pseudomonas mandelii JR-1

GCA_000012205 Pseudomonas savastanoi pv. phaseolicola 1448A

GCA_000816985 Pseudomonas aeruginosa

GCA_000746525 Pseudomonas alkylphenolia

GCA_000496605 Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA1

GCA_000204295 Pseudomonas mendocina NK-01

GCA_000829415 Pseudomonas sp. StFLB209

GCA_000012265 Pseudomonas protegens Pf-5

GCA_000412675 Pseudomonas putida NBRC 14164

GCA_000397205 Pseudomonas protegens CHA0

GCA_000648735 Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae ICMP 18884

GCA_000012245 Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae B728a

GCA_000761195 Pseudomonas chlororaphis subsp. aurantiaca

GCA_000818015 Pseudomonas balearica DSM 6083

GCA_000219605 Pseudomonas stutzeri ATCC 17588 = LMG 11199

GCA_000219705 Pseudomonas putida S16

GCA_000511325 Pseudomonas sp. FGI182

GCA_000508765 Pseudomonas aeruginosa LES431

GCA_000297075 Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes CECT 5344

GCA_000517305 Pseudomonas cichorii JBC1

GCA_000963835 Pseudomonas chlororaphis

GCA_000327065 Pseudomonas stutzeri RCH2

GCA_000271365 Pseudomonas aeruginosa DK2

Streptococcus

GCA_000211015 Streptococcus pneumoniae SPN034183

GCA_000210975 Streptococcus pneumoniae INV104

GCA_000203195 Streptococcus gallolyticus subsp. gallolyticus ATCC BAA-2069

GCA_001020185 Streptococcus pyogenes

GCA_000253155 Streptococcus oralis Uo5

GCA_000696505 Streptococcus equi subsp. zooepidemicus CY

GCA_000463355 Streptococcus intermedius B196

GCA_000698885 Streptococcus thermophilus ASCC 1275

GCA_000014205 Streptococcus sanguinis SK36

GCA_000007045 Streptococcus pneumoniae R6

GCA_000306805 Streptococcus intermedius JTH08

GCA_000196595 Streptococcus pneumoniae TCH8431/19A

GCA_000262145 Streptococcus parasanguinis FW213

GCA_001026925 Streptococcus agalactiae

GCA_000251085 Streptococcus pneumoniae ST556

GCA_000019025 Streptococcus pneumoniae Taiwan19F-14

GCA_000211055 Streptococcus pneumoniae SPN994039

GCA_000688775 Streptococcus sp. VT 162

GCA_000231905 Streptococcus suis D12

GCA_000026665 Streptococcus pneumoniae ATCC 700669

GCA_000283635 Streptococcus macedonicus ACA-DC 198

GCA_000014365 Streptococcus pneumoniae D39

GCA_000019265 Streptococcus pneumoniae Hungary19A-6

GCA_000299015 Streptococcus pneumoniae gamPNI0373

GCA_000019985 Streptococcus pneumoniae CGSP14

GCA_000463395 Streptococcus constellatus subsp. pharyngis C232

GCA_000187935 Streptococcus parauberis NCFD 2020

GCA_000253315 Streptococcus salivarius JIM8777

GCA_000427055 Streptococcus agalactiae ILRI112

GCA_000246835 Streptococcus infantarius subsp. infantarius CJ18

GCA_000427075 Streptococcus agalactiae ILRI005

GCA_000007465 Streptococcus mutans UA159

GCA_000831165 Streptococcus anginosus

GCA_000147095 Streptococcus pneumoniae 670-6B

GCA_000817005 Streptococcus pneumoniae

GCA_000180515 Streptococcus pneumoniae SPNA45

GCA_000441535 Streptococcus lutetiensis 033

GCA_000210955 Streptococcus pneumoniae OXC141

GCA_000009545 Streptococcus uberis 0140J

GCA_000648555 Streptococcus iniae

GCA_000027165 Streptococcus mitis B6

GCA_000018985 Streptococcus pneumoniae JJA

GCA_000270165 Streptococcus pasteurianus ATCC 43144

GCA_000479315 Streptococcus sp. I-P16

GCA_000478925 Streptococcus anginosus subsp. whileyi MAS624

GCA_000019825 Streptococcus pneumoniae G54

GCA_000017005 Streptococcus gordonii str. Challis substr. CH1

GCA_000479335 Streptococcus sp. I-G2

GCA_000385925 Streptococcus oligofermentans AS 1.3089

GCA_000210935 Streptococcus pneumoniae INV200

GCA_000211035 Streptococcus pneumoniae SPN994038

GCA_000221985 Streptococcus pseudopneumoniae IS7493

GCA_000006885 Streptococcus pneumoniae TIGR4

GCA_000018965 Streptococcus pneumoniae 70585

GCA_000348705 Streptococcus pneumoniae PCS8235

GCA_000210995 Streptococcus pneumoniae SPN034156

GCA_000231925 Streptococcus suis ST1

GCA_000019005 Streptococcus pneumoniae P1031

GCA_000188715 Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis ATCC 12394

GCA_000026585 Streptococcus equi subsp. equi 4047

Funding Statement

This work was partly supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (EmPowerPutida, Contract No. 635536, granted to Vitor A P Martins dos Santos).

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

[version 3; referees: 1 approved

Supplementary material

Figure S1. Persistence of Sequence Based (SB) clusters.

Cluster persistence is defined as the relative number of genomes with at least one protein assigned to the cluster. The plots show frequency of SB clusters according to their persistence. Publicly available and complete genome sequences assigned to each taxon were selected so that phylogenetic diversity within the taxon was preserved, as described in materials and methods. 60 distinct genome sequences were considered for each taxon shown.

Figure S2. Persistence of Domain Architecture Based (DAB) clusters.

The plots show frequency of DAB clusters according to their persistence.

Figure S3. Comparison between DAB and SB clusters.

On the left DAB is used as a reference and each bar represents the relative frequency of one DAB cluster containing sequences assigned to {1, 2, . . . , 5} and 6 or more SB clusters and one-to-one represents the relative frequency of identical cluster. Similarly, on the right SB is used as a reference. Axis labels follow notation in Figure 5

References

- 1. Puigbò P, Lobkovsky AE, Kristensen DM, et al. : Genomes in turmoil: quantification of genome dynamics in prokaryote supergenomes. BMC Biol. 2014;12(1):66. 10.1186/s12915-014-0066-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gogarten JP, Doolittle WF, Lawrence JG: Prokaryotic evolution in light of gene transfer. Mol Biol Evol. 2002;19(12):2226–2238. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dutilh BE, Backus L, Edwards RA, et al. : Explaining microbial phenotypes on a genomic scale: GWAS for microbes. Brief Funct Genomics. 2013;12(4):366–380. 10.1093/bfgp/elt008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pallen MJ, Wren BW: Bacterial pathogenomics. Nature. 2007;449(7164):835–842. 10.1038/nature06248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Joshi T, Xu D: Quantitative assessment of relationship between sequence similarity and function similarity. BMC Genomics. 2007;8(1):222. 10.1186/1471-2164-8-222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kuipers RK, Joosten HJ, Verwiel E, et al. : Correlated mutation analyses on super-family alignments reveal functionally important residues. Proteins. 2009;76(3):608–616. 10.1002/prot.22374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Goodwin S, McPherson JD, McCombie WR: Coming of age: ten years of next-generation sequencing technologies. Nat Rev Genet. 2016;17(6):333–351. 10.1038/nrg.2016.49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yang S, Doolittle RF, Bourne PE: Phylogeny determined by protein domain content. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(2):373–378. 10.1073/pnas.0408810102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Snipen LG, Ussery DW: A domain sequence approach to pangenomics: applications to Escherichia coli [version 2; referees: 2 approved]. F1000Res. 2013;1:19. 10.12688/f1000research.1-19.v2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Koehorst JJ: High throughput functional comparison of 432 genome sequences of pseudomonas using a semantic data framework. Sci Rep.(in press),2016. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Saccenti E, Nieuwenhuijse D, Koehorst JJ, et al. : Assessing the Metabolic Diversity of Streptococcus from a Protein Domain Point of View. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0137908. 10.1371/journal.pone.0137908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Addou S, Rentzsch R, Lee D, et al. : Domain-based and family-specific sequence identity thresholds increase the levels of reliable protein function transfer. J Mol Biol. 2009;387(2):416–430. 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.12.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Thakur S, Guttman DS: A De-Novo Genome Analysis Pipeline (DeNoGAP) for large-scale comparative prokaryotic genomics studies. BMC Bioinformatics. 2016;17(1):260. 10.1186/s12859-016-1142-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ponting CP, Russell RR: The natural history of protein domains. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2002;31:45–71. 10.1146/annurev.biophys.31.082901.134314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Eddy SR: Profile hidden Markov models. Bioinformatics. 1998;14(9):755–763. 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.9.755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Van Domselaar GH, Stothard P, Shrivastava S, et al. : BASys: a web server for automated bacterial genome annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(Web Server issue):W455–W459. 10.1093/nar/gki593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Koonin EV, Wolf YI, Karev GP: The structure of the protein universe and genome evolution. Nature. 2002;420(6912):218–223. 10.1038/nature01256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kummerfeld SK, Teichmann SA: Protein domain organisation: adding order. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10(1):39. 10.1186/1471-2105-10-39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Björklund AK, Ekman D, Light S, et al. : Domain rearrangements in protein evolution. J Mol Biol. 2005;353(4):911–923. 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.08.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fong JH, Geer LY, Panchenko AR, et al. : Modeling the evolution of protein domain architectures using maximum parsimony. J Mol Biol. 2007;366(1):307–315. 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.11.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Song N, Sedgewick RD, Durand D: Domain architecture comparison for multidomain homology identification. J Comput Biol. 2007;14(4):496–516. 10.1089/cmb.2007.A009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lee B, Lee D: Protein comparison at the domain architecture level. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10(Suppl 15):S5. 10.1186/1471-2105-10-S15-S5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Geer LY, Domrachev M, Lipman DJ, et al. : CDART: protein homology by domain architecture. Genome Res. 2002;12(10):1619–1623. 10.1101/gr.278202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Boratyn GM, Schäffer AA, Agarwala R, et al. : Domain enhanced lookup time accelerated BLAST. Biol Direct. 2012;7(1):12. 10.1186/1745-6150-7-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Messih MA, Chitale M, Bajic VB, et al. : Protein domain recurrence and order can enhance prediction of protein functions. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(18):i444–i450. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Doğan T, MacDougall A, Saidi R, et al. : UniProt-DAAC: domain architecture alignment and classification, a new method for automatic functional annotation in UniProtKB. Bioinformatics. 2016;32(15):2264–71. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. UniProt Consortium: UniProt: a hub for protein information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(Database issue):D204–D212. 10.1093/nar/gku989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Finn RD, Coggill P, Eberhardt RY, et al. : The Pfam protein families database: towards a more sustainable future. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(D1):D279–D285. 10.1093/nar/gkv1344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Haft DH, Selengut JD, White O: The TIGRFAMs database of protein families. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(1):371–373. 10.1093/nar/gkg128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mitchell A, Chang HY, Daugherty L, et al. : The InterPro protein families database: the classification resource after 15 years. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(Database issue):D213–D221. 10.1093/nar/gku1243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Letunic I, Doerks T, Bork P: SMART: recent updates, new developments and status in 2015. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(Database issue):D257–D260. 10.1093/nar/gku949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sigrist CJ, de Castro E, Cerutti L, et al. : New and continuing developments at PROSITE. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(Database issue):D344–7. 10.1093/nar/gks1067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hyatt D, Chen GL, Locascio PF, et al. : Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:119. 10.1186/1471-2105-11-119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jones P, Binns D, Chang HY, et al. : InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(9):1236–40. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ekseth OK, Kuiper M, Mironov V: orthAgogue: an agile tool for the rapid prediction of orthology relations. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(5):734–736. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. van Dongen SM: Graph clustering by flow simulation.PHD Thesis, University of Utrecht,2000. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 37. Snipen L, Liland KH: micropan: an R-package for microbial pan-genomics. BMC Bioinformatics. 2015;16(1):79. 10.1186/s12859-015-0517-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tettelin H, Masignani V, Cieslewicz MJ, et al. : Genome analysis of multiple pathogenic isolates of Streptococcus agalactiae: implications for the microbial "pan-genome". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(39):13950–13955. 10.1073/pnas.0506758102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kristensen DM, Kannan L, Coleman MK, et al. : A low-polynomial algorithm for assembling clusters of orthologous groups from intergenomic symmetric best matches. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(12):1481–1487. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Alexeyenko A, Tamas I, Liu G, et al. : Automatic clustering of orthologs and inparalogs shared by multiple proteomes. Bioinformatics. 2006;22(14):e9–e15. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Finn RD, Mistry J, Schuster-Böckler B, et al. : Pfam: clans, web tools and services. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(Database issue):D247–D251. 10.1093/nar/gkj149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Goodacre NF, Gerloff DL, Uetz P: Protein domains of unknown function are essential in bacteria. MBio. 2013;5(1):e00744–13. 10.1128/mBio.00744-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Soucy SM, Huang J, Gogarten JP: Horizontal gene transfer: building the web of life. Nat Rev Genet. 2015;16(8):472–482. 10.1038/nrg3962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Altenhoff AM, Dessimoz C: Phylogenetic and functional assessment of orthologs inference projects and methods. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009;5(1):e1000262. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kristensen DM: Referee report for: Protein domain architectures provide a fast, efficient and scalable alternative to sequence-based methods for comparative functional genomics [version 1; referees: 1 approved, 2 approved with reservations]. F1000Res. 2016;5:1987 10.5256/f1000research.10140.r15678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]