Abstract

Although expected, distinct gender-specific trajectories from early victimization to later offending have not been well explored. Consequently, this study assessed the association between child maltreatment (ages 0–11) and offending behavior within gender-specific models. Prospectively collected data, including official measures of maltreatment and offending, derived from the Chicago Longitudinal Study, a panel study of 1,539 low-income minority participants,

Multivariate probit analyses revealed that maltreatment significantly predicted delinquency for males but not females yet forged a significant relation to adult crime for both genders. Exploratory confirmatory and comparative analyses suggested that mechanisms linking maltreatment to adult crime primarily differed across gender. For males, childhood-era externalizing behavior and school commitment along with adolescent-era socioemotional skills, delinquency, and educational attainment fully explained the maltreatment-crime nexus. For females, childhood-era parent factors along with adolescent indicators of externalizing behavior, cognitive performance, mobility and educational attainment partially mediated the maltreatment-crime relation. Implications of results were explored.

Keywords: child maltreatment, juvenile delinquency, adult crime, gender, mediation

Introduction

Evidence from studies conducted over the past several decades consistently links child maltreatment (CM) to juvenile delinquency (e.g, Smith & Thornberry, 1995). A small number of studies published relatively recently also suggests that the criminogenic effects of CM extend into adulthood (e.g., English, Widom, & Brandford, 2001). It appears that the association between child maltreatment and adolescent or adult offending manifests for both males and females (Maxfield & Widom, 1996), although gender-specific analyses are rare (Herrera & McCloskey, 2001).

Select criminological theory, such as Howell’s, implies that pathways from CM (or child abuse and neglect) to offending may differ to some extent between males and females (Johansson & Kempf-Leonard, 2009). To wit, male CM victims may engage in crime partly as a result of negative peer affiliations, whereas maltreatment-related mental health problems may promote crime involvement particularly for female CM victims (e.g., Bender, 2010). The field, however, lacks an adequate body of knowledge to support or challenge these hypotheses.

Empirical insight into the similar or differential nature of the association between CM and offending behavior across gender helps to address unresolved questions and to test unsupported hypotheses in the field. It also yields important implications for intervention design and public policy. Accordingly, the current study investigates gender-specific models of the association between CM and offending behavior with the following research questions:

Does CM predict juvenile delinquency and adult crime in males and females?

What mechanisms mediate the CM-crime association within gender subgroups?

Do these gender-specific mediation models differ significantly?

Data derived from the Chicago Longitudinal Study (CLS), a prospective investigation of over 1,500 low-income, primarily African American (AA) participants representing a cohort of students who graduated from Chicago Public School kindergarten in 1986. Prospectively administered participant, parent, and teacher assessments along with ongoing administrative record searches produced multiple measures spanning child, adolescent, and early adult years.

Literature Review

Whether measured retrospectively among adolescent or adult offenders or prospectively among child cohorts, child abuse and neglect appears to increase the risk for offending behavior. A number of landmark studies have helped to establish a significant link between CM and juvenile delinquency (e.g., Smith & Thornberry, 1995; Widom, 1989). Extending investigations into adulthood, researchers have found that incarcerated adult offenders tend to report significantly higher rates of CM relative to non-offending adult samples (e.g. Lake, 1995; Weeks & Widom, 1998). Buttressing these results, several prospectively designed studies have shown that although the majority of CM victims avoid adult offending, CM significantly increases the risk for criminality (see English et al., 2001; Fagan, 2005; Maxfield & Widom, 1996). Furthermore, observed associations between CM and adolescent and/or adult offending appear consistent across racial/ethnic subgroups (English et al., 2001; Maxfield & Widom, 1996).

Theorists, empiricists, and practitioners alike have been motivated to understand the ways in which the CM-offending association varies across gender. Accounting for this interest at least in part are increases in female delinquency rates over the past few decades at a time when male offending is declining (Wolf, Graziano, & Hartney, 2009). These divergent trends have prompted scholars to consider the possibility that female and male offending may have unique etiologies.

Feminist theorists in particular assert that child victimization is an especially salient precursor of delinquency and crime for females (Daly & Chesney-Lind, 1988). It may be, in other words, a strain or life course event that increases the likelihood of offending primarily among females. To a limited extent, empirical evidence supports this claim. A number of studies, for example, revealed that significantly more female delinquents reported experiences of child abuse (physical, sexual, emotional) relative to male delinquents (e.g., Dembo, Williams, & Schmeidler, 1993; Belknap & Holsinger, 2006). Female adult offenders have also been shown to report a significantly greater likelihood of childhood victimization compared to adult male offenders (McClellan, Farabee, & Couch, 1997; Payne, Gainey, & Carey, 2007).

The potential, however, of males to under-report abuse experiences could bias these results (Lab, Feigenbaum, & De Silva, 2000). Prospectively designed studies tender conclusions that challenge these patterns of findings. To wit, English and colleagues (2001) found that CM, ages 0–11, increased the probability of lifetime arrest (juvenile or adult) for both genders.

While it is plausible that child victimization increases the risk for different types of offenses across gender (Maxfield & Widom, 1996; Widom & Ames, 1994), overall CM appears to introduce significant offending risk for both genders. According to Belknap and Holsinger (2006), theory ought to accommodate this finding and recognize the global role that early maltreatment fulfills in the development of offending trajectories. Additional prospective investigations into the criminogenic nature of CM within both male and female subsamples can help validate this perspective (see Fagan, 2005).

Moreover, investigations into the pathways that lead males and females from CM to criminality are needed to help illuminate poorly understood mechanisms of effect for both males and females (Bender, 2010). Theorists have posited gender-neutral and gender-specific pathways from early victimization to offending (see Giordano, Deines, & Cernkovich, 2006). However, few studies have assessed intervening processes with distinct male and female mediation models.

Hypothesized gender-neutral factors that might actualize CM’s criminogenic effects for both genders include individual, family, and school-related processes. At the individual level, externalizing behaviors (e.g., inattention, defiance, aggression) may generalize across gender to help potentiate CM’s effect on offending (Fagan, 2001). Results from Maschi, Morgen, Bradley, and Hatcher (2008) support the notion that child abuse and neglect predict externalizing behaviors in girls and boys.

Family processes may also help explain the association between CM and offending behavior for both genders. For instance, early studies relying on methods such as convenience sampling and non-standardized measurement of child maltreatment showed that positive family relationships could protect males against criminal behavior in the aftermath of CM (Kruttschnitt, Ward, & Scheble, 1987; McCord, 1983). Although the data from which these results emerged were male-specific, there is reason to believe the findings could apply to females (see Jaffee, Caspi, Moffitt, Polo-Tomas, & Taylor, 2007). Testing this assertion with more recently collected data and more rigorously designed methods is warranted.

In addition to family support, family or residential instability may help mediate the relation between child maltreatment and offending behavior. For example, using population-level data, Ryan and Testa (2005) found a significant relation between out-of-home placement and delinquency among both male and female CM victims. In a recently published study (DeGue & Widom, 2009), out-of-home placement alone did not mediate the CM-adult crime link. However, placement instability did enhance the risk for criminality among adults maltreated as children.

Regarding school-related variables, CM appears to impair school performance across gender (Leiter, 2007; Veltman & Brown, 2001); consequently, school disengagement has been hypothesized as a potential mediator of the CM-offending behavior association (Bender, 2010). Longstanding research suggests that positive school performance may protect maltreated girls against delinquent involvement more readily than maltreated boys (Zingraff, Lieter, Johnsen, & Myers, 1994). These results, however, have not been replicated.

Posited gender-specific mediators of the CM-offending link include peer-related factors for males along with mental health and substance abuse for females (Bender, 2010). Although peer factors typically characterize male delinquency patterns, evidence also implicates peer factors in general female delinquency (Gavazzi, Yarcheck, & Chesney-Lind, 2006; Silverman & Caldwell, 2008). Furthermore, victims of CM across gender are more socially isolated and less socially skilled than their non-maltreated counterparts (Bolger & Patterson, 2003; Dodge, Pettit, & Bates, 1994). Whether peer factors represent a gender-specific pathway from CM to crime for males but not females is ultimately unknown and subject to empirical testing.

While mental health issues manifest as a consequence of child maltreatment for both males and females (e.g., Horwitz, Widom, Mclaughlin, & White, 2001), female offenders report problems with mental health at a consistently higher rate than do male offenders (e.g., Teplin, Abram, McClelland, Dulcan, & Mericle, 2002). In turn, these problems may underlie offending behavior for women. For instance, a recent study by Postlethwaite, Barth, and Guo (2010) found that depression helped explain increases in self-reported delinquency over time for girls who had been reported and investigated for CM.

Substance abuse may also fulfill a unique role in the criminal trajectory of females maltreated as children. A number of researchers have described the overlapping relations between child victimization, substance use disorders, and criminality among women (e.g., Bloom, Owen, & Covington, 2004; Widom & White, 1997). Postlethwaite and colleagues (2010) have found, though, that substance use may contribute to delinquency among adolescent boys who were reported for CM.

In sum, our knowledge about the gender-specific pathways linking CM to offending behavior remains under-developed. Theory highlights important similarities and distinctions across gender. Associated hypotheses, however, require greater empirical substantiation.

Unique Contributions

Our study’s main-effect analyses address unresolved questions about CM’s role in predicting delinquency and crime for males and females. Additionally, our mediation analyses explore relatively unexamined mechanisms that link early victimization to later offending within gender-specific models. Moreover, the study defines offending behavior not only with a measure of delinquency but also with an indicator of adult crime, extending tests of CM’s criminogenic effects into adulthood, a rare yet illuminating approach (Degue & Widom, 2009).

Confidence in study results is enhanced with an advanced research design. To specify, data were collected prospectively over many years and across multiple sources. When participants reached age of majority, comparable CM and non-CM groups emerged within the dataset, providing the opportunity to examine maltreatment-related consequences within naturally-occurring sample subgroups. Although detecting consequences of CM can be difficult given the relatively low prevalence of child maltreatment (see Aos, Lieb, Mayfield, Miller, & Pennucci, 2004), the study’s sample size increases the ability to observe CM effects.

Finally, the study assesses a homogeneous sample of disadvantaged minority participants at risk for both CM and arrest (Sedlak & Broadhurst, 1996; English et al., 2001). Although limiting generalizability of results, these sample characteristics reflect population subgroups that are overrepresented in child welfare, juvenile justice, and criminal justice settings. Implications of study results are, therefore, highly relevant for intervention design and public policy.

Method

Study and Sample

The Chicago Longitudinal Study (CLS) is an ongoing panel investigation that follows 1,539 economically disadvantaged, minority individuals from birth through age 24. The original sample included all children who enrolled in the Chicago Child-Parent Center (CPC) preschool program, in 1983 or 1984, and completed a CPC kindergarten program in 1986 (n=989). The CPC program is an early childhood intervention that provides educational and family-support services to children residing in high-poverty areas. A matched comparison group consisted of children from low-income families who did not attend CPC preschool programs but did graduate from a full-day, public kindergarten in 1986 (n=550). One aim of the CLS is to evaluate, through a quasi-experimental cohort design, the long-term effects of the CPC program (Reynolds, 2000). A second aim, assessing the psychosocial development of study participants at risk for pervasive maladjustment, guides the current study. Consequently, child maltreatment represents the explanatory variable in this study.

Maltreated and non-maltreated groups emerged in the CLS dataset after review of official CM records in 1998, when study participants averaged 18 years of age. Official maltreatment records were obtained from juvenile court and child protective service records for all participants living in the Chicago area after age 10 (Reynolds & Robertson, 2003). Delinquency and adult crime data derived from official administrative records supplemented with self-reports for a small minority of cases. Cases for which we had valid CM and delinquency data (1,471) as well as valid CM and adult crime data (1,404) comprised our current study samples, reflecting a 95.6% and 91.2% rate of original sample recovery, respectively. The CLS has performed attrition analyses with these or similar study samples and found few significant differences between the study and attrition samples (see Mersky & Topitzes, 2010).

Data Collection

Since its inception, the CLS has collected extensive data on its participants. During initial stages of the project, data were collected from the Chicago Public Schools and other administrative sources. From kindergarten through the seventh grade, the CLS monitored study participants annually through child, parent, and/or teacher reports. Thereafter, the CLS collected additional survey and administrative data at multiple time points through early adulthood. Participant records housed within administrative data sources were identified and verified through social security number and birth date matching procedures.

Outcome Measures

Our two dichotomous outcome measures, juvenile delinquency and adult arrest conviction, indicated any juvenile arrest resulting in a petition to the juvenile court and any adult arrest resulting in a guilty verdict in adult court, respectively. Delinquency data originated from official juvenile court records of Cook County in Illinois, and Milwaukee and Dane counties in Wisconsin. The CLS accessed adult arrest records from county, state, and federal jurisdictions.

Mediator Measures

In concert with exploratory analysis strategies (explained in data analysis section below), identical sets of mediators were tested across male and female models. Measures that emerged as significant mediators in exploratory contexts, however, differed to some degree across gender. For instance, six measures emerged as significant mediators in both male and the female models, reflecting individual, family, peer, or school-related processes. However, only two of these measures were identical across gender-specific models while four were unique to each model.

Indicators of individual and peer adjustment in the male mediator model included troublemaking behavior, grades 3–6 and social-emotional skills, grades 6–7. Troublemaking behavior measured student self-reports on 4 items (“I get in trouble at school”, “I get in trouble at home”, “I follow class rules”, and “I fight at school”). Three item response options were presented in grades 3 and 4 (1=not much, 2=some, 3=a lot) and four in grades 5 and 6 (from 1=strongly agree to 4=strongly disagree). A total score per year was calculated by summing the scale ratings after reverse coding the item denoting obedient behavior. Summed scores were transformed into Z-scores and averaged across grades (Reynolds, Temple, & Ou, 2010).

The social-emotional skills measure aggregated two subscales of the Teacher-Child Rating Scale (T-CRS; Perkins & Hightower, 2002)—frustration tolerance and peer social skills—and reflected teachers’ ratings of how well students demonstrated social and emotional competence at school, from not well at all (1) to very well (5). Frustration tolerance consisted of five items connoting emotional equilibrium and interpersonal tolerance while peer social skills, also developed from five items, indicated friendliness, sociability and peer popularity. To arrive at a single variable, we summed the items from both subscales for each grade. The 10-items for each grade produced an alpha reliability coefficient of above .90, respectively. We averaged the summed scores across the two grades while relying on scores for either if only one existed.

One family-based indicator emerged in the male mediator model: parent expectations, grades 2–4. This measure indexed teacher reports of parents’ scholastic expectations for their child, from poor (1) to excellent (5). The alpha reliability coefficient for the three grades was .67

Two school-related indicators emerged in the male mediation model: school commitment, grade 5 and high school graduation. We created the school commitment measure from a 16-item scale administered at the end of grade 5. Students responded with answers ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (4) to items such as the following: I try hard in school; I like school; School is important. The reliability coefficient for the 16 items was .76.

The high school graduation measure occupied a second temporal block in the male mediation model. Data for this measure hailed from school administrative records supplemented with adult self-reports. Aside from high school graduation, juvenile delinquency (described above) constituted the remaining second block variable in the male mediator model.

For the female mediator model, two measures of individual adjustment appeared in the first block of mediator variables: acting out, grades 6–7 and reading achievement, grade 8. The acting out measure resulted from a 6-item T-CRS subscale indicating teachers’ ratings (1 to 5) of students’ disruptive, defiant or aggressive classroom behavior in grade 6 and grade 7. To create the study measure, items were summed within and averaged across years. The six items within each year produced alpha reliability coefficients exceeding .90. Our measure of reading achievement, an indicator of cognitive development in this study, reflected reading scores on the Iowa Test of Basic Skills, a widely-used instrument with sound properties of reliability and validity (Hieronymus, Lindquist, & Hoover, 1980). The reliability estimate for these test scores within the CLS sample equaled .92.

Family-related processes in the female mediation model included the following first block measures: parent expectations, grades 2–4; parent involvement, grades 4–6; and school mobility, grades 4–8. The alpha reliability coefficient for the three teacher-rated parent expectation items was equivalent for males and females (.67). We created the parent involvement measure by averaging annual teacher ratings, from poor (1) to excellent (5), of “parent’s participation in school activities.” The alpha reliability coefficient for the three items was .73. Our indicator of school mobility indexed the number of school moves a child experienced from grades 4 through 8. The CLS obtained these data via grade-by-grade analyses of school system records. We characterize this measure as a proxy of family instability, recognizing that it also may capture school-related processes. The second block in the female mediator model includes just one measure: high school graduation.

Explanatory Measure and Covariates

The child maltreatment measure combines data from two sources: petitions to Cook County Juvenile Court and Cook County referrals to the Illinois Department of Child Services (DCFS). From these records, we created a dichotomous explanatory variable denoting one or more substantiated reports of child maltreatment, ages 0–11. Participants were coded 1 if they had a verified report in at least one of the two data sources.

All multivariate analyses included a set of covariate measures created from multiple data sources including the Illinois Longitudinal Public Assistance Research Database, Chicago Public Schools, and parent surveys. CPC preschool participation served as a control variable (1=participation, 0=no participation) along with race/ethnicity (0=Hispanic, 1=African American). Two covariates accounted for early environmental risks: parent substance abuse, ages 0–5 and a 7-item risk index measured approximately at age 3. To create the former measure, we referenced retrospective self-reports from a young adult CLS participant survey (Mersky & Topitzes, 2010). For the risk index, we summed the following 7 dichotomous items: (a) mother ever a teen parent, (b) mother not employed, (c) mother did not complete high school, (d) four or more children in the household, (e) single-parent household, (f) high neighborhood poverty (≥40% below poverty level, 1980 Census), and (g) household AFDC receipt (Reynolds, 2000).

A measure of kindergarten word analysis reflected scores on a subtest of the Iowa Test of Basic Skills and indicated pre-reading skills. We modeled this measure as an exogenous covariate in study analyses to control for early developed abilities.

Missing Data

A number of mediator measures lacked valid data on select cases due to differential attrition across assessment time points. The percentage of missing data per measure was as follows: troublemaking behavior, 10.2%; socioemotional skills and acting out, 27.7%; reading achievement, 8.8%; parent expectations, 10.4%; school commitment, 16.0%; parent involvement, 17.3%; and school mobility, 10.2%. Using an expectation-maximization algorithm (Schafer, 1997), we estimated missing values with multiple imputation in LISREL. This strategy generates values for missing observations by drawing on known associations between the measure in question and other study variables (du Toit & du Toit, 2001).

Data Analysis

First, in multivariate probit regression analyses with the full CLS sample, we regressed our delinquency and crime indicators, respectively, on a predictor model that included gender, study covariates, and child maltreatment in order to establish a main-effect relation between CM and offending behavior. To answer research question 1, we disaggregated the CLS sample by gender and repeated these analyses. In follow-up probit analyses with the full sample, we assessed the impact of the interaction between gender and CM on juvenile delinquency and adult arrest conviction, respectively. Probit analysis uses a maximum likelihood estimator and has been shown to generate reliable parameters for large samples (Horowitz & Savin, 2001). Probit transforms results into marginal effect coefficients, indicating percentage-point change in outcomes corresponding to one-unit changes in predictors.

In response to research question 2, we again separated male and female subsamples, and explored potential mediators of the link between child maltreatment and adult arrest conviction. We tested the same set of mediators for both gender-specific models, selecting measures based on an ecological-transactional understanding of maltreatment’s consequences (Kim & Cicchetti, 2004). With exploratory hierarchical regression, we tested measures from individual, family, peer, and school domains to determine if these proposed mediators fulfilled three mediation criteria: (1) were significantly associated with the explanatory variable net of study covariates; (2) related significantly to ultimate or penultimate model outcomes net of study covariates and all other mediators that met criterion 1 (MacKinnon, Krull, & Lockwood, 2000); and (3) contributed to a reduction in magnitude of the original main-effect relation between CM and adult arrest conviction (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2002). We trimmed measures that failed to achieve all criteria. We first dropped measures that did not meet criterion 1. We subsequently removed measures that were non-significantly associated with the ultimate or penultimate outcomes in the adjusted model, i.e., criterion 2. Measures demonstrating the weakest, non-significant association with the outcome/s were dropped first during exploratory stage 2. After each measure was removed, we re-ran regression analyses. Order of removal did not affect the final outcome. Last, per criterion 3, we cut measures that contributed no mediating effect. This systematic process of variable pairing represents an “adaptive” approach to specifying mediator models and enhancing causal inference (MacKinnon, 2008).

To confirm our mediator models, we employed structural equation modeling (SEM) with LISREL software (Jöreskog & Sorbom, 1996). SEM in LISREL simultaneously estimates a set of equations, one for each intervening variable, via maximum likelihood (ML) based on PRELIS-generated correlation matrices. Updates to the LISREL program software facilitated use of ML with categorical data (Jöreskog, Sorbom, du Toit, & du Toit, 1999). Completely standardized regression coefficients were generated to represent the direct and indirect paths of effect. We covaried measures within the same mediator block, operations that were planned a priori, and represented latent variables with single indicators. To increase accuracy of results, we incorporated estimates of variable measurement errors and relied on test statistics of 2.00 and 2.50 to convey statistical significance (α levels of approximately .05 and .01, respectively). Below, we report two indicators of overall model fit: the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and adjusted goodness-of-fit index. RMSEA values below 0.05 and AGFI values above .90 indicate good fit (Byrne, 1998).

To address question 3, we conducted a two-group mediation analysis with LISREL, using a Chi-square difference test to evaluate whether the finalized male and female SEM models were statistically equivalent (null hypothesis). Two X2 statistics were generated reflecting how well the data fit the model specification when male and female mediation models were considered (1) invariant and (2) variant, respectively. Subtracting one X2 result from the other yielded a X2 difference statistic associated with the null hypothesis. Null hypotheses are rejected with a statistically significant (α<.05) X2 difference statistic (see Jöreskog, 2002). This particular analysis is only conducted with group models of identical structure; therefore, we ran this analysis twice. Initially, we tested equivalence of models using the mediator variable structure that represented the finalized male mediator model. We repeated the analysis by replacing the mediator variable structure with the finalized female version.

Results

Analyses related to question 1 revealed that child maltreatment significantly predicted juvenile delinquency in the full and male-only sample but not in the female-only sample. Over half or 51.3% of the male study participants who experienced substantiated CM, compared to 32.2% of males who did not have a verified CM history, went on to commit documented acts of delinquency, a statistically significant difference (p<.01) that represents a 59.3% increase in offending risk. Female youth who were maltreated as children incurred a higher adjusted rate of delinquent offending relative to non-maltreated female youth (7.7% vs. 5.7%), yet this difference was statistically non-significant. Follow-up analysis with the full CLS sample revealed that gender did not significantly moderate the relation between CM and delinquency.

Child maltreatment significantly predicted adult arrest conviction for the full CLS sample and for both male-only and female-only samples. Specifically, child maltreatment increased the adjusted likelihood for adult arrest conviction among males by 58.3% (from 37.9% to 60.0%, p<.01) and among females by 148.9% (from 4.7% to 11.7%, p<.05). Again, gender did not significantly moderate the link between CM and adult arrest conviction.

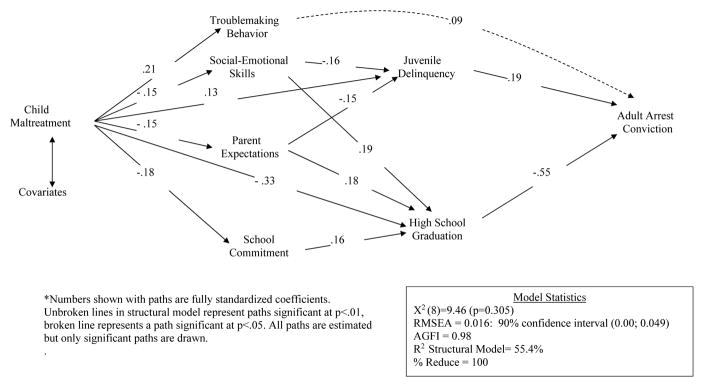

To address question 2, we explored mediators of the relation between child maltreatment and adult arrest conviction via hierarchical probit regression and arrived at the following solutions for the male mediator model. Significant first-block mediators included troublemaking behavior, social-emotional skills, parent expectations and school commitment. Juvenile delinquency and high school graduation emerged as second-block mediators. The estimated model fully mediated the original main-effect relation. We tested indicators of other domains such as motivational development, but they failed to meet predetermined mediation criteria.

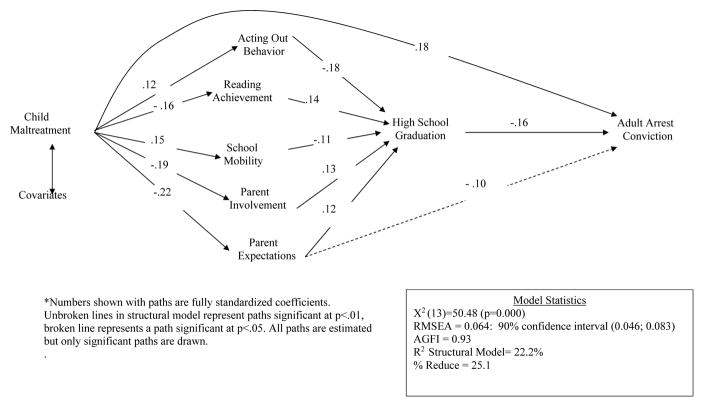

Parent expectation as a first block measure and high school graduation as a second block measure also surfaced as significant mediators in the female model. Other significant first block mediators for the female model included acting out, reading achievement, parent involvement, and school mobility. High school graduation was the only significant mediator in the second block. This final model only partially reduced the original main-effect relation. Other mediators were tested such as substance abuse and depression but did not produce significant effects.

SEM analysis results are depicted in Table 1 and Figures 1 and 2. Table 1 exhibits the PRELIS-generated correlation matrices from which the two gender-specific SEM models emerged. Results from SEM analysis with the male sample confirmed exploratory mediation tests. All six significant mediators from previous analysis contributed effects in the SEM model; moreover, the full model fully reduced the original main effect relation by a magnitude of 100% while eliminating a direct path from CM to adult arrest conviction. In this model, troublemaking behavior yielded direct mediation effects, while social-emotional skills and parent expectations provided indirect mediation through both delinquency and high school graduation; school commitment also contributed indirect mediation, but only through high school graduation. Juvenile delinquency offered direct mediation by virtue of a direct path from CM and a direct path to the outcome. Delinquency transmitted indirect mediation effects through its association with preceding mediators. Last, high school graduation provided direct and indirect mediation effects. The male mediation model fit the data well, given an RMSEA well below .05 and an AGFI well-above .90, and explained 55.4% of the outcome’s variance.

Table 1.

Correlation Matrices and Descriptive Statistics

| Variables | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | 13. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Race/ethnicity | 1.00 | .206 | −.064 | −.130 | .171 | .023 | .181 | −.106 | −.118 | −.006 | .156 | −.198 | .207 |

| 2. Risk index | .269 | 1.00 | .110 | .088 | −.153 | .212 | .204 | −.210 | −.260 | −.179 | .160 | −.397 | .197 |

| 3. Parent substance abuse, ages 0–5 | .128 | .002 | 1.00 | .052 | .068 | .294 | .051 | .121 | .179 | .056 | .078 | −.158 | .210 |

| 4. CPC preschool participation | .043 | −.016 | .353 | 1.00 | .232 | −.207 | −.056 | .149 | .118 | .097 | −.236 | .035 | −.094 |

| 5. Kindergarten word analysis | .050 | −.118 | .131 | .301 | 1.00 | −.148 | −.160 | .442 | .349 | .189 | −.109 | .127 | −.058 |

| 6. Child maltreatment, ages 0–11 | .184 | .171 | .202 | −.044 | −.012 | 1.00 | .164 | −.191 | −.206 | −.195 | .225 | −.243 | .311 |

| 7. Troublemaking bx, grades 3–6/ Acting out, grades 6–7 | .021 | .182 | .002 | −.096 | −.115 | .212 | 1.00 | −.284 | −.286 | −.282 | .101 | −.350 | .170 |

| 8. Social-emotional skills, grades 6–7/ Reading achievement, grade 8 | −.139 | −.185 | −.011 | .085 | .273 | −.172 | −.342 | 1.00 | .465 | .312 | −.187 | .312 | −.187 |

| 9. Parent expectations, grades 2–4 | −.178 | −.295 | .024 | .159 | .349 | −.202 | −.210 | .262 | 1.00 | .409 | −.155 | .320 | −.196 |

| 10. School commitment, grade 5/Parent involvement, grades 4–6 | .069 | −.055 | .065 | .164 | .192 | −.154 | −.398 | .233 | .261 | 1.00 | −.159 | .304 | −.140 |

| 11. Juvenile Delinquency/School mobility, grades 4–8 | .058 | .115 | .178 | −.136 | −.101 | .259 | .221 | −.247 | −.240 | −.210 | 1.00 | −.243 | .182 |

| 12. High school graduation | −.058 | −.243 | −.051 | .140 | .161 | −.421 | −.245 | .321 | .343 | .301 | −.619 | 1.00 | −.319 |

| 13. Adult arrest conviction | .021 | .198 | .115 | −.105 | −.132 | .303 | .270 | −.273 | −.287 | −.254 | .560 | −.691 | 1.00 |

| Note. The upper diagonal matrix represents correlations generated with the male subsample (n=688), and the lower diagonal matrix represents results derived with the female subsample (n=716). Correlations were estimated as pearson/polyserial/polychoric by PRELIS 2.80 with pairwise-present cases. In row headings with two variable names listed, the first is modeled as a mediator in analyses with the male subsample and the second is considered a mediator in analyses with the female subsample. | |||||||||||||

| Males | |||||||||||||

| Range | 0–1 | 0–7 | 0–1 | 0–1 | 19–99 | 0–1 | −1.72–2.95 | 10–50 | 1–5 | 30.29– 64.00 | 0–1 | 0–1 | 0–1 |

| Mean/Rate | 0.92 | 3.56 | 0.35 | 0.62 | 62.83 | 0.08 | 0.18 | 30.01 | 3.23 | 49.52 | 0.35 | 0.42 | 0.40 |

| Standard Deviation | 0.26 | 1.68 | 0.18 | 0.49 | 14.03 | 0.27 | 0.73 | 6.70 | 0.86 | 5.49 | 0.48 | 0.49 | 0.49 |

| Females | |||||||||||||

| Range | 0–1 | 0–7 | 0–1 | 0–1 | 26–99 | 0–1 | 6–30 | 82–212 | 1–5 | 1–5 | 0–4 | 0–1 | 0–1 |

| Mean/Rate | 0.94 | 3.61 | 0.34 | 0.68 | 64.86 | 0.10 | 10.72 | 148.82 | 2.65 | 3.49 | 0.88 | 0.63 | 0.06 |

| Standard Deviation | 0.24 | 1.69 | 0.18 | 0.47 | 12.46 | 0.30 | 5.13 | 19.97 | 0.98 | 0.87 | 0.91 | 0.48 | 0.24 |

Figure 1.

Structural equation model depicting mediating paths from child maltreatment to adult arrest conviction for males (n=688)*

Figure 2.

Structural equation model depicting mediating paths from child maltreatment to adult arrest conviction for females (n=716)

In the female model (Figure 2) all first-block mediators indirectly mediated CM’s crime effects via significant paths to high school graduation. In turn, high school graduation linked directly to the outcome. Additionally, parent expectations contributed direct mediation effects. This model did not fully explain the original main effect. Based on calculations of total and mediated effects, the model accounted for 25.1% of the CM-adult arrest conviction link; meanwhile, a significant direct path remained between CM and the outcome. The model explained 22.2% of the outcome’s variance and fit the data only moderately well, producing an RMSEA of .64 and an AGFI of .93.

Using the variable structure constituting the finalized male SEM model, we conducted an analysis of the invariance between male and female models.. Tests of the null (H0) and alternative hypotheses yielded X2 statistics of 662.64 (df=96, p<.000) and 255.05 (df=38, p<.000), respectively. H0, stating that the models are invariant, was rejected based on X2 difference of 407.59 (df=58, p<.000), supporting the conclusion that the empirical models are different. Subsequently, we replaced these measures with variables that comprised the final female model and repeated the analysis. Results yielded similar test statistics, indicating that the male and female models were significantly different.

Discussion

Results from question 1 demonstrated that CM was a significant predictor of delinquency for males in the CLS but not for females. Tempering this finding, however, was the discovery that gender did not significantly moderate the CM-delinquency link. These findings strengthen the hypothesis that maltreatment enhances delinquency risk, particularly among economically disadvantaged males (Bright & Johnson-Reid, 2008). The null finding for females contradicts results from several prospective studies that found child maltreatment significantly predicted delinquency among female subgroups (Bright & Johnson, 2008; English et al., 2001; Widom, 1989). Certain distinctions between our study and these other investigations regarding sample characteristics, measurement and design may help explain the divergent results.

When exploring the association between CM and adult offending behavior within gender subgroups, we found that CM significantly predicted adult arrest conviction for both males and females. Although the percent increase in adult offending associated with CM was greater for women than for men, no significant moderation effects for gender were found. While it may be true that CM plays a more prominent role in the commission of crime for women versus men and that perhaps a greater number of alternative factors contribute to adult criminality for men, it appears that we cannot dismiss the importance of CM as a potential contributor to male criminal trajectories. Theorists and policy-makers alike have been reluctant to portray male adult offenders as victims during any stage of the life course (Hooper, 2010), yet our findings and that of others call this perspective into question (e.g., Widom & Wilson, 2009).

The significant, adjusted relation between CM and adult crime among women, taken together with the finding that CM did not significantly predict official delinquency among girls, suggests that the criminogenic influences of child maltreatment may be somewhat delayed for females. Cernkovich, Lanctot, and Giordano (2008) reached a similar conclusion. A number of factors may account for this “lagged” effect. For example, female adolescents with a history of maltreatment in childhood may engage in antisocial behavior in part as a consequence of CM, but the severity of their behavior may not generate official delinquency petitions to juvenile court. Instead, their behavior may translate into school infractions and/or status offenses that do not ultimately result in deep end juvenile court proceedings. Furthermore, female survivors of CM may gravitate toward illegal behavior later in life as a function of dependent affiliations formed in adulthood with crime-involved men, Also, women who experienced the strain of CM may rely on drugs and alcohol to cope with symptoms of traumatic stress in adulthood, increasing the chances of committing drug-related crimes over time as traumatic symptoms and addictive behavior intensify (Fagan, 2001).

Results from research questions 2 and 3 revealed that the mediation models explaining mechanisms linking CM to adult crime for males and females differed with regard to mediating effects, model fit, and statistical comparability. Model structures also diverged, although the male and female mediator models shared two common mediator measures: parent expectations and high school graduation. That is, low parental expectations in childhood and poor high school graduate rates helped explain crime involvement among both male and female victims of child maltreatment. Other than these shared measures, however, the majority of significant mediators within each model differed across gender.

For instance, a childhood tendency toward troublemaking or externalizing behavior along with adolescent offending appeared to contribute to adult offending among male CM victims. In addition,, low school commitment in elementary school and impaired social and emotional skills in middle school propelled male victims of CM toward adult offending. These measures, along with parent expectations and high school graduation fully explained the CM-crime link. This suggests that for boys maltreated from the ages of 0–11 who are later convicted of adult crime criminal trajectories emanate from childhood and adolescent processes.

In contrast to the male model results, mediation analysis with the female subsample uncovered the following measures as female-specific individual-, family-, and school-based mediators: acting out behavior in grades 6–7, reading achievement in grade 8, school mobility in grades 4–8, parent involvement in grades 3–6, and parent expectations in grades 2–4. Unlike the male mediator model, the female model did not fully explain the CM-crime link. We suspect that unmeasured and untested adult and possibly adolescent experiences, if included, would have helped the model achieve full mediation. For instance, affiliations with crime-involved men may have helped explain CM’s link to adult crime for women (Chesney-Lind, Morash, & Stevens, 2008). Additionally, CM may have promoted internalizing adolescent behaviors among females, which in turn might contribute to later mental health problems and criminal involvement (Graves, 2007). We did not possess, however, a broad range of adult relationship indicators or adolescent internalizing measures. Omitted variable bias, therefore, arguably limited the explanatory power of our female mediator model.

Examining individual mediators across models indicates that, for males, childhood manifestations of externalizing behavior, measured in our model with troublemaking behavior, may represent a significant and direct catalyst of CM’s effects on adult crime. For females, externalizing behavior in adolescence may help potentiate the effects of CM, albeit indirectly. Acting out in middle school may not have surfaced as a significant mediator in our model for boys in part because it is a relatively normative issue with middle school males. For instance, boys in the CLS received acting out ratings from their middle school teachers the exceeded CLS girls’ ratings by .60 of a standard deviation. Therefore, acting out may not discriminate CM survivors from non-survivors as well among males as among females.

Our indicator of social and emotional development in middle school, consisting of peer social skills and frustration tolerance, mediated CM effects for boys but not for girls. Peer dynamics may be more important in the development of male offending compared to female offending (see Daigle, Cullen, & Wright, 2007; Steffensmeier & Allan, 1996). Our results suggest that CM may contribute to factors such as poor social skills, emotion dysregulation, and antisocial peer affiliations that tend to characterize male offending trajectories.

For boys, low school commitment in grade 5 contributed to the offending-related sequelae of CM, whereas for girls, low reading achievement in middle school conferred offending risk to CM survivors. This indicates that early disengagement from school for boys versus later performance declines for girls may actualize CM long-term influence on crime. Developmental researchers have noted that boys are more inclined to withdraw from the school process earlier than girls (Sax, 2001). Moreover, limited support exists for the finding that later school success prevents offending behavior more readily for girls versus boys (Daigle et al., 2007). It therefore may be the case that school-related outcomes of CM manifest at different developmental stages for boys and girls with implications for intervention design.

Parent expectations for boys appeared to fulfill a central role in our study’s male mediator model. These findings comport with prior evidence indicating that parent expectations may offer compensatory effects for disadvantaged males (Wood, Kaplan, & McLoyd, 2007). In addition to parent expectations, two family factors in childhood emerged as significant mechanisms in our mediator model for females: parent involvement in school, and school mobility. Given that our mobility measure may be a proxy for family instability, these findings indicate that family processes fulfill a vital role in the post-maltreatment pathway to offending for females, perhaps more so than for males (Tyler, Johnson, & Brownridge, 2008).

For males, high school graduation contributed substantial variance to the study mediation model. In fact, after identifying the total indirect effect of the mediator model as estimated in LISREL and calculating the proportion of this effect for which the various pathways accounted, we found that high school graduation was associated with the largest magnitude of effect among all model mediators. Juvenile delinquency produced the second largest mediating effect in the male model. This suggests that although the origins of adult offending for men maltreated as children can be traced to post-maltreatment childhood processes, success or failure in meeting developmental milestones of adolescence will strongly influence the development of criminality.

High school graduation, or lack thereof, also played a critical role in the progression from early victimization to later offending for females. In previous studies (e.g., Acoca, 2000), low educational attainment contributed significantly to the development of offending behavior in general for females and appears to also play a primary role in the emergence of offending behavior among female survivors of CM. It may, for instance, promote financial reliance on criminally-involved men along with fewer options for conventional earnings, conditions that correlate with crime (Reckdenwald & Parker, 2008). It is noteworthy that for girls in our sample delinquency did not mediate, even indirectly, the CM-crime association. This finding accords with previous research (Steffensmeier & Allan, 1996) and reinforces the interpretation that the criminogenic effects of CM tend to manifest in adulthood for females.

Limitations

Four primary study limitations condition the interpretation of our findings. First, we utilized official administrative data to measure CM. Although these data possess inherent strengths, limitations include underestimation of CM incidence rates which could result in a conservative estimate of the observed association between CM and offending (see Fagan, 2005). Second, because our sample was not selected on maltreatment status, we lacked the statistical power to purely disaggregate the maltreatment measure by CM subtype. Consequently, we could not test differential crime effects of these various forms of child maltreatment, a recommended strategy reflecting emerging knowledge of the distinct consequences associated with different forms of CM (Cicchetti, 2004). Third, we also did not distill the study outcome into various arrest conviction categories in order to assess, across gender, CM’s association with violent, property, drug, and other crime types. We have reason to believe these analyses would yield important gender distinctions (Schwartz & Steffensmeier. 2007); therefore, we proceeded under the assumption that adult criminal behavior manifests uniquely across gender and that our investigation would primarily uncover unique pathways from CM to crime. Last, several mediators lacked valid data on a number of cases. To replace missing data, we employed an inferential imputation strategy that produced variables with comparable properties as the original measures; however, confidence in mediation results is nonetheless affected.

Implications

Our results highlight two key themes: a) as it is for females, child maltreatment is also an important predictor of offending behavior for males, and b) the pathways from CM to adult offending are somewhat distinct between males and females. This suggests first that programming for both male and female offenders ought to incorporate a focus on maltreatment history via assessment and intervention strategies. Growing evidence identifies efficacious treatment models that target the effects of childhood trauma among adolescents or adults (e.g., Amaya-Jackson & DeRosa, 2007; Courtois, Ford, & Cloitre, 2009). Adaptations of such approaches to offender services are indicated but uncommon, particularly among programs delivered to males (Falshaw, 2005).

The mechanisms that link developmental trauma, such as CM, to offending may differ across gender. Bennett, Farrington, and Huesmann (2005) point out that males and females respond to trauma and stress differentially given distinct patterns of social cognition. These or related dynamics may result in gendered behavioral processes leading from CM to offending. Our mediation results offer some support for these claims and amplify calls for gender-specific offender treatment (Bloom et al., 2004).

For instance, it appears that male offenders who have been maltreated as children engage in processes within childhood and adolescence that ultimately culminate in adult offending. We found that troublemaking behavior and low school commitment in elementary school increased the risk of adult offending among maltreated boys in the CLS. These insights, along with the knowledge that low parent expectations for child’s school success in elementary grades contributed to later criminality among maltreated boys, could inform early school-based interventions. Such interventions might address behavioral management along with school satisfaction (e.g., PATHS curriculum; Kam, Greenberg, & Kusche, 2004). Also, male adolescents in the CLS who were maltreated as children had relatively impaired emotion regulation and peer social skills, which fueled school failure and delinquent involvement. These results illuminate treatment targets of services for male delinquents (see Ford, Chapman, Mack, & Pearson, 2006). The overall male mediation results also suggest that male adult offenders who have been maltreated might benefit from attention to CM history and to social-emotional skills, along with common remedial education programming.

Our findings showed that family-related processes helped to actualize the criminogenic effects of CM for females. Effective family systems treatment for female victims of CM may represent a promising early intervention to protect against criminal trajectories. Female youth who act out in middle school also are at-risk for later offending. Because this finding resembles previous results (Wall, Barth, & NSCAW Research Group, 2005), concern for adolescent girls who exhibit externalizing behavior in middle or high school is heightened. School-based interventions that address externalizing behavior and low reading achievement in middle school may help prevent crime-involvement among maltreated girls; however, our study indicates that other domains of functioning may need to be addressed to help maltreated girls avoid crime.

Most clearly, our mediation results support the integration of various services across youth-serving systems. To illustrate, mechanisms in our study that helped to transmit CM’s crime effects for males included socioemotional-, parent-and school-related factors that can be and often are addressed through mental health, child welfare, school, and/or juvenile justice services. For girls, externalizing behaviors, family factors, and school performance helped explain the progression from CM to adult crime, domains of functioning also targeted by the above-noted delivery systems. Rather than duplicating services across these systems and/or limiting service targets within each, we recommend a synergistic, cross-systems collaboration.

Several treatment models or systems-level interventions, such as multisystemic therapy and wraparound services, encourage this very integration of services for children who exhibit emotional and behavioral problems. These models show promise in reducing delinquency (Henggeler & Sheidow, 2003; Pullman et al., 2006) and have inspired interventions, such as trauma systems therapy (Saxe, Ellis, & Kaplow, 2007), that target multiple domains of functioning and numerous systems of care. Results from developmental research such as ours, findings from intervention research and trends in public funding all reinforce the need for coordination across youth-serving systems in order to enhance case outcomes and contain program costs (Wulczyn, Barth, Yuan, Harden, & Landsverk, 2005).

Acknowledgments

Chicago Longitudinal Study grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (No. R01HD34294-06) and the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation (No. 20030035) supported the research reported herein. The Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education provided additional support with a dissertation grant (No. R305C050055) administered through the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Biographies

James Topitzes, Social Work Department, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee; Joshua P. Mersky, Social Work Department, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee; Arthur J. Reynolds, Institute of Child Development, University of Minnesota-Twin Cities.

James Topitzes earned his doctorate in social welfare from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and currently serves as an assistant professor of social work at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. His primary research interests include consequences of child maltreatment, prevention of child maltreatment, social determinants of health, and innovative treatment approaches including mindfulness meditation to resolve trauma.

Joshua P. Mersky earned his doctorate in social welfare at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and also serves as an assistant professor of social work at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. His research focuses on the antecedents and pathways that lead to dysfunction and resilience among low-income, urban-dwelling youth. His work also considers how research can contribute to effective prevention and intervention services for children and youth.

Arthur J. Reynolds earned his doctorate in educational psychology from the University of Illinois at Chicago. He currently serves as professor of child development, University of Minnesota-Twin Cities, and directs the Chicago Longitudinal Study. He is interested in school and family influences on child development, prevention science, and the determinants of adult well-being. He also studies how developmental and evaluation research affect social policy.

Contributor Information

James Topitzes, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

Joshua P. Mersky, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

Arthur J. Reynolds, University of Minnesota-Twin Cities

References

- Aos S, Lieb R, Mayfield J, Miller M, Pennucci A. Benefits and costs of prevention and early intervention programs for youth. Olympia, WA: Washington State Institute for Public Policy; 2004. No. 04-07-3901. [Google Scholar]

- Acoca L. Legislate or incarcerate: Girls in the Florida and Duval County Juvenile Justice system. Jacksonville, FL: National Council on Crime and Delinquency; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Amaya-Jackson L, DeRosa R. Treatment considerations for clinicians in applying evidence-based practice to complex presentations in child trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2007;20:379–390. doi: 10.1002/jts.20266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belknap J, Holsinger K. The gendered nature of risk factors for delinquency. Feminist Criminology. 2006;1:48–71. [Google Scholar]

- Bender K. Why do some maltreated youth become juvenile offenders?: A call for further investigation and adaptation of youth services. Children and Youth Services Review. 2010;32:466–473. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett S, Farrington DP, Huesmann LR. Explaining gender differences in crime and violence: The importance of social cognitive skills. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2005;10:263–288. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom B, Owen B, Covington S. Women offenders and the gendered effects of public policy. Review of Policy Research. 2004;21:31–49. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger KE, Patterson CJ. Sequalea of child maltreatment: Vulnerability and resilience. In: Luthar SS, editor. Resilience and vulnerability: Adaptation in the context of childhood adversities. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2003. pp. 156–181. [Google Scholar]

- Bright CL, Johnson-Reid M. Onset of juvenile court involvement: Exploring gender-specific associations with maltreatment and poverty. Children and Youth Services Review. 2008;30:914–927. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2007.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM. Structural equation modelling with LISREL, PRELIS, and SIMPLIS: Basic concepts, applications and programming. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Cernkovich SA, Lanctôt N, Giordano PC. Predicting adolescent and adult antisocial behavior among adjudicated delinquent females. Crime & Delinquency. 2008;54:3–33. [Google Scholar]

- Chesney-Lind M, Morash M, Stevens T. Girls troubles, girls delinquency, and gender-responsive programming: A review. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology. 2008;41:162–189. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D. An odyssey of discovery: Lessons learned through three decades of research on child maltreatment. American Psychologist. 2004;59:731–741. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple regression/correlation: Analysis for the behavioral sciences. London: Psychology Press, Taylor & Francis Grp; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Courtois CA, Ford JD, Cloitre M. Best practices in psychotherapy for adults. In: Courtois CA, Ford JD, editors. Treating complex traumatic stress disorders: An evidence-based guide. New York: The Guilford Press; 2009. pp. 82–103. [Google Scholar]

- Daigle LE, Cullen FT, Wright JP. Gender differences in the predictors of juvenile delinquency: Assessing the generality–specificity debate. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice. 2007;5:254–286. [Google Scholar]

- Daly K, Chesney-Lind M. Feminism and Criminology. Justice Quarterly. 1988;5:497– 548. [Google Scholar]

- DeGue S, Widom CS. Does out-of-home placement mediate the relationship between child maltreatment and adult criminality? Child Maltreatment. 2009;14:344–355. doi: 10.1177/1077559509332264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dembo R, Williams L, Schmeidler J. Gender differences in mental health service needs among youths entering a juvenile detention center. Journal of Prison and Jail Health. 1993;12:73–101. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE. Socialization mediators of the relation between socioeconomic status and child conduct problems. Child Development. 1994;65:649–665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- du Toit M, du Toit S. Interactive LISREL: User’s guide. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International, Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- English D, Widom C, Brandford C. Childhood victimization and delinquency, adult criminality, and violent criminal behavior: A replication and extension. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice; 2001. NCJ 192291. [Google Scholar]

- Fagan AA. The gender cycle of violence: Comparing the effects of child abuse and neglect on criminal offending for males and females. Violence and Victims. 2001;16:457–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan AA. The relationship between adolescent physical abuse and criminal offending: Support for an enduring and generalized cycle of violence. Journal of Family Violence. 2005;20:279–290. [Google Scholar]

- Falshaw L. The link between a history of maltreatment and subsequent offending behaviour. Probation Journal. 2005;52:423–434. [Google Scholar]

- Ford JD, Chapman J, Mack M, Pearson G. Pathways from traumatic child victimization to delinquency: Implications for juvenile and permanency court proceedings and decisions. Juvenile and Family Court Journal, Winter. 2006;2006:13– 23. [Google Scholar]

- Gavazzi S, Yarcheck C, Chesney-Lind M. Global risk indicators and the role of gender in a juvenile detention sample. Criminal Justice & Behavior. 2006;33:597–612. [Google Scholar]

- Giordano PC, Deines JA, Cernkovich SA. In and out of crime: A life course perspective on girls’ delinquency. In: Heimer K, Kruttschnitt C, editors. Gender and crime: Patterns in victimization and offending. New York: University Press; 2006. pp. 17–40. [Google Scholar]

- Graves K. Not always sugar and spice: Expanding theoretical and functional explanations for why females aggress. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2007;12:131–140. [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Sheidow AJ. Conduct disorder and delinquency. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2003;29:505–522. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2003.tb01692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera VM, McCloskey LA. Gender differences in the risk of delinquency among youth exposed to family violence. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2001;25:1037–1051. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(01)00255-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hieronymus AN, Lindquist EF, Hoover HD. Iowa tests of basic skills: Primary battery. Chicago: Riverside; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper CA. Gender, child maltreatment, and young people’s offending. In: Featherstone B, Hooper CA, Scourfield J, Taylor J, editors. Gender and child welfare in society. Chichester, West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2010. pp. 61–94. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz JL, Savin NE. Binary response models: Logit, probits and semiparametrics. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2001;15:43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz AV, Widom CS, McLaughlin J, White HR. The impact of early childhood abuse and neglect on adult mental health: A prospective study. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2001;42:1184–1201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffee SR, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Polo-Tomas M, Taylor A. Individual, family, and neighborhood factors distinguish resilient from non-resilient maltreated children: A cumulative stressors model. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2007;31:231–253. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson P, Kempf-Leonard K. A gender-specific pathway to serious, violent, and chronic offending? Exploring Howell’s risk factors for serious delinquency. Crime & Delinquency. 2009;55:216–240. [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog KG. Structural equation modeling with ordinal variables using LISREL. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International, Inc; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog K, Sorbom D. LISREL 8: User’s reference guide. Chicago: Scientific Software International; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog K, Sorbom D, Du Toit S, Du Toit M. LISREL 8: New statistical features. Chicago: Scientific Software International, Inc; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kam C, Greenberg MT, Kusche CA. Sustained effects of the PATHS curriculum on the social and psychological adjustment of children in special education. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2004;12:66–78. [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Cicchetti D. A longitudinal study of child maltreatment, mother-child relationship quality and maladjustment: The role of self-esteem and social competence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32:341–354. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000030289.17006.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruttschnitt C, Ward D, Scheble MA. Abuse resistant youth: Some factors that may inhibit violent criminal behaviour. Social Forces. 1987;66:501–519. [Google Scholar]

- Lab DD, Feigenbaum JD, De Silva P. Mental health professionals’ attitudes and practices towards male childhood sexual abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2000;24:391– 409. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00152-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lake ES. Offenders’ experiences of violence: A comparison of male and female inmates as victims. Deviant Behavior: An Interdisciplinary Journal. 1995;16:269–290. [Google Scholar]

- Leiter J. School performance trajectories after the advent of reported maltreatment. Child and Youth Services Review. 2007;29:363–382. [Google Scholar]

- Maschi T, Morgen K, Bradley C, Hatcher S. Exploring gender differences on internalizing and externalizing behavior among maltreated youth: Implications for social work action. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. 2008;25:531–547. [Google Scholar]

- Maxfield MG, Widom CS. The cycle of violence: Revisited six years later. Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine. 1996;150:390–395. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170290056009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClellan D, Farabee D, Couch B. Early victimization, drug use, and criminality: A comparison of male and female prisoners. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 1997;24:455–76. [Google Scholar]

- McCord J. A forty year perspective on effects of child abuse and neglect. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1983;7:265–270. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(83)90003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Krull JL, Lockwood CM. Equivalence of the mediation, confounding, and suppression effect. Prevention Science. 2000;1:173–181. doi: 10.1023/a:1026595011371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mersky JP, Topitzes J. Comparing early adult outcomes of maltreated and non-maltreated children: A prospective longitudinal investigation. Children and Youth Services Review. 2010;32:1086–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2009.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne BK, Gainey RR, Carey CS. All in the family: Gender, family crimes, and later criminality. Women & Criminal Justice. 2007;16:73–89. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins PE, Hightower AD. T-CRS 2.1 teacher child rating scale: Examiner’s manual. Rochester, NY: Children’s Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Postlethwaite AW, Barth RP, Guo S. Gender variation in delinquent behavior changes of child welfare-involved youth. Children and Youth Services Review. 2010;32:318–324. [Google Scholar]

- Pullman MD, Kerbs J, Koroloff N, Veach-White E, Gaylor R, Sieler D. Juvenile offenders with mental health needs: Reducing recidivism using wraparound. Crime & Delinquency. 2006;52:375–397. [Google Scholar]

- Reckdenwald A, Parker KF. The influence of gender inequality and marginalization on types of female offending. Homicide Studies. 2008;14:208–226. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds AJ. Success in early intervention: The Chicago Child-Parent Centers. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds AJ, Robertson D. School-based early intervention and later child maltreatment in the Chicago Longitudinal Study. Child Development. 2003;74:3–26. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds AJ, Temple JA, Ou S. Preschool education, educational attainment, and crime prevention: Contributions of cognitive and non-cognitive skills. Children and Youth Services Review. 2010;32:1054–1063. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2009.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan JP, Testa MF. Child maltreatment and juvenile delinquency: Investigating the role of placement instability. Children and Youth Services Review. 2005;27:227–249. [Google Scholar]

- Sax L. Reclaiming kindergarten: Making kindergarten less harmful to boys. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2001;2:3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Saxe GN, Ellis BH, Kaplow JB. Collaborative treatment of traumatized children and teens: The trauma systems therapy approach. New York: Guilford Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL. Analysis of incomplete data. London: Chapman and Hall; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz J, Steffensmeier D. The nature of female offending: Patterns and explanation. In: Zaplin R, editor. Female offenders: Critical perspective and effective interventions. 2. New York: Jones & Bartlett; 2007. pp. 43–75. [Google Scholar]

- Sedlak AJ, Broadhurst DD. Third national incidence study of child abuse and neglect: Final report. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman JR, Caldwell RM. Peer relationships and violence among female juvenile offenders. An exploration of differences among four racial/ethnic populations. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2008;35:333–343. [Google Scholar]

- Smith C, Thornberry TP. The relationship between childhood maltreatment and adolescent involvement in delinquency. Criminology. 1995;33:451–477. [Google Scholar]

- Steffensmeier D, Allan E. Gender and crime: Towards a gendered theory of female offending. Annual Review of Sociology. 1996;22:459–487. [Google Scholar]

- Teplin LA, Abram KM, McClelland GM, Dulcan MK, Mericle AA. Psychiatric disorders in youth in juvenile detention. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:1133–1143. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.12.1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler KA, Johnson KA, Brownridge DA. A longitudinal study of the effects of child maltreatment on later outcomes among high-risk adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2008;37:506–521. [Google Scholar]

- Veltman MWM, Brown KD. Three decades of child maltreatment research. Trauma, Violence & Abuse. 2001;2:215–239. [Google Scholar]

- Wulczyn F, Barth RP, Yuan Y, Harden BJ, Landsverk J. The epidemiology of child maltreatment. In: Wulczyn F, Barth RP, Yuan Y, Harden BJ, Landsverk J, editors. Beyond common sense: Child welfare, child well-being, and the evidence for policy reform. New Brunswick, NJ: Aldine; 2005. pp. 59–90. [Google Scholar]

- Wall AE, Barth RP NSCAW Research Group. Aggressive and delinquent behavior of maltreated adolescents: Risk factors and gender differences. Stress, Trauma, and Crisis: An International Journal. 2005;8:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Weeks R, Widom CS. Self-reports of early childhood victimization among incarcerated adult male felons. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1998;13:346–361. [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS. Child abuse, neglect, and adult behavior: Research design and findings on criminality, violence, and child abuse. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1989;59:355–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1989.tb01671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CP, Ames MA. Criminal consequences of childhood sexual victimization. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1994;18:303–318. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(94)90033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, White H. Problem behaviors in abused and neglected children grown up: Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance abuse, crime, and violence. Criminal Behavior and Health. 1997;7:287–310. [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Wilson HW. How victims become offenders. In: Bottoms BL, Najdowski CJ, Goodman GS, editors. Children as victims, witnesses, and offenders: Psychological science and the law. New York: Guilford Press; 2009. pp. 250–274. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf AM, Graziano J, Hartney C. The provision and completion of gender- specific services for girls on probation: Variation by race and ethnicity. Delinquency & Crime. 2009;55:294–312. [Google Scholar]

- Wood D, Kaplan R, McLoyd VC. Gender differences in the educational expectations of urban, low-income African American youth: The role of parents and the school. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2007;36:417–427. [Google Scholar]

- Zingraff M, Leiter J, Johnsen M, Myers K. The mediating effect of good school performance on the maltreatment-delinquency relationship. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 1994;31:62–91. [Google Scholar]