Abstract

Congenital heart defects (CHDs) are the most common of all birth defects, yet molecular mechanism(s) underlying highly prevalent atrial septal defects (ASDs) and ventricular septal defects (VSDs) have remained elusive. We demonstrate the indispensability of “balanced” post-translational SUMO conjugation-deconjugation pathway for normal cardiac development. Both hetero- and homo-zygous SUMO-1 knockout mice exhibited ASDs and VSDs with high mortality rates, which were rescued by cardiac re-expression of the SUMO-1 transgene. Since SUMO-1 was also involved in cleft lip/palate in human patients, the above findings provided a powerful rationale to question whether SUMO-1 was mutated in babies born with cleft palates and ASDs. Sequence analysis of DNA from newborn screening blood spots revealed a single 16 bp substitution in the SUMO-1 regulatory promoter of a patient displaying both oral-facial clefts and ASDs. Diminished sumoylation activity whether by genetics, environmental toxins and/or pharmaceuticals may significantly contribute to susceptibility to the induction of congenital heart disease worldwide.

Normal cardiovascular development is a complex process that requires highly coordinated collaboration among a variety of transcription factors and signal transduction pathways. Congenital heart defects (CHDs) which are structural malformations that are present at birth, are the most common of all human birth defects, occurring in approximately 1% of all newborns (Wu and Child, 2004). The two most frequent CHDs are the atrial septal defects (ASDs) and ventricular septal defects (VSDs) (Hoffman and Kaplan, 2002), defined as the presence of a communication between the right and left atria, and the right and left ventricles, respectively. The occurrence of ASDs and/or VSDs can be either isolated, or associated with each other, or with other CHDs, such as Tetralogy of Fallot (Vaughan and Basson, 2000). Although a number of transcription factors, including GATA4, Nkx2.5, and Tbx5, as well as several signaling pathways, including Notch, Wnt, BMP, and Hedgehog have been reported to be involved in septogenesis (Baldini, 2005; Bruneau et al., 2001; Garg et al., 2003; Nie et al., 2008; Niessen and Karsan, 2008; Tanaka et al., 1999), chromosomal and Mendelian syndromes account for only 20% of septal defects (Bentham and Bhattacharya, 2008). Thus, the unifying molecular mechanism(s) accounting for the vast majority of ASDs and VSDs remains elusive.

The fact that SUMO (Small ubiquitin-like modifier) conjugation pathway components are abundant in the heart points to the possibility that the SUMO pathway may be implicated in cardiovascular development via modifying transcription factors indispensable for normal cardiovascular development (Golebiowski et al., 2003; Watanabe et al., 1996). Indeed, we and others identified several cardiac-enriched transcription factors GATA-4, Nkx2.5, serum response factor (SRF) and Myocardin as SUMO targets (Komatsu et al., 2004; Matsuzaki et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2008). Sumoylation is a post-translational protein modification in which a novel super family of ubiquitin-like proteins (SUMO1-3/Sentrin) is tethered to target proteins, affecting their biological activity (Johnson, 2004; Yeh et al., 2000). SUMO conjugation is accomplished via the following phases: maturation, activation, conjugation/ligation, and de-conjugation (Johnson, 2004; Wang, 2009). At least three functional SUMO protein isoforms have been identified in higher vertebrates (Johnson, 2004). Active SUMO-2 and -3 share over 95% similarity at amino acid level but exhibit only ~50% identity with SUMO-1. SUMO conjugation is accomplished after transfer of the SUMO protein to the unique conjugation enzyme (E2)-Ubc9; there upon Ubc9 can transfer SUMO protein directly to its substrates. In vivo SUMO conjugation and ligation can be modulated by a number of E3 ligases. Sumoylation is reversible by de-conjugation; SUMO proteins are de-conjugated from their conjugation state by Sentrin/SUMO-specific proteases (SENPs), a family of 6 members of which SENP1 and SENP2 can process all SUMO conjugates (Yeh, 2008).

Proteomic studies have shown that SUMO-1 and SUMO-2/3 can be conjugated to unique target subsets but also show some overlap in target specificity (Rosas-Acosta et al., 2005; Vertegaal et al., 2006; Vertegaal et al., 2004). Other studies have revealed differences in the behavior and dynamics of SUMO isoforms (Ayaydin and Dasso, 2004; Fu et al., 2005; Mukhopadhyay and Dasso, 2007; Saitoh and Hinchey, 2000; Tatham et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2008b); thus, suggestive of distinct functions for SUMO-1 compared with SUMO-2/3. However, there is still no clear understanding of which roles are unique for the SUMO isoforms and to what degree any redundancy exists between them. Sumoylation plays a critical role in many cellular processes, including cell cycle progression and chromatin remodeling. However, no role for decreased sumoylation in cardiovascular development has been reported.

Here, we demonstrate that hetero- and homozygous SUMO-1 knockout (KO) mice developed CHDs, ASDs and VSDs, coincident with the dysregulation of genes involved in cell proliferation. SUMO-1 may also play a role in the modulation of chromatin remodeling complexes, whereby inappropriate liver gene expression is suppressed in the developing heart. In addition, sequence analysis of DNA from newborn screening blood spots also revealed a single 16 bp substitution mutation in the SUMO-1 regulatory of a patient displaying both oral-facial clefts and ASDs. Thus, reduced sumoylation activity caused by genetics, environmental toxins, and/or by drugs may significantly contribute to the pervasiveness of congenital heart disease.

Materials and Methods

Generation of transgenic and knockout mice

The α-MHC-flag-SUMO-1 transgene was constructed using PCR-amplified flag-tagged SUMO-1 cloned between the 5.4 kbp mouse α-MHC promoter (provided by Dr. J. Robbins, University of Cincinnati) and the Simian virus 40 (SV40) polyadenylation sequence via SalI sites. The orientation of inserted transgene was confirmed by DNA sequencing. The constructs were microinjected into the pronucleus of fertilized eggs from FVB mice, which were crossed back to C57BL/6 mice for over three generations. Genomic DNA was isolated from tail biopsies performed on weaned animals (about 3-week old pups) and screened by PCR, followed by western blot and/or RT-PCR to verify the expression of the transgene in transgenic mouse hearts (SUMO-1-Tg). SUMO-1-Tg mice were born at Mendelian rate, viable and fertile. No any discernable phenotypes were observed in SUMO-1-Tg mice at one month age. SUMO-1 knockout mice, derived from gene-trapped embryonic stem cells with lacZ insertion (BayGenomics, Ca), were provided by Drs. Richard Maas at Harvard Medical University (designated as SUMO-1Gal/+) (Alkuraya et al., 2006) and Michael Kuehn at National Cancer Center (designated as SUMO-1+/− and SUMO-1−/−, respectively) (Zhang et al., 2008a). These SUMO-1-knockout mice were bred with C57/BL6 mice, and thus were analyzed on a mixed 129P2/OlaHsd and C57BL6/J background. Nkx2.5+/− mouse line were generated previously (Moses et al., 2001). The cross breeding among various knockout and/or transgenic mice was performed as needed. Animals were handled in accordance with institutional guidelines with IACUC approvals.

Plasmids, transfections and antibodies

Human SUMO-1 gene cis-regulatory element (-1454 bps from transcription initiation site of human SUMO-1) was cloned and fused into a luciferase reporter construct pGL3-basic from Promega (Madison, WI) at KpnI and XhoI sites, and subsequently two mutants, A-1239G and Mut-16, were generated using mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) and designated as Mut-16-Luc and A-1239G-Luc, respectively. Transfections were performed on 24 well/plate containing HL-1 cell line provided by Dr. William Claycomb at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center (White et al., 2004) using lipofectamine 2000 purchased from Invitrogen (Chicago, IL) based on the protocol provided by manufacturer. Cell extracts were purified for luciferase activity assays 48 hours post-transfection. Anti-SUMO-1 and anti-GAPDH antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-flag antibody (M2) was from Sigma (St. Louise, MO).

Whole-mount RNA in situ hybridization

In situ hybridization to detect SUMO-1 transcripts in the murine developing hearts was detailed previously (Wei et al., 2001). Briefly, embryos at specified developmental stages were collected and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C, followed by brief wash in diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated standard phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and dehydrated in serial methanol. The samples were then rehydrated in methanol/PBT series, bleach with 6%H2O2 one hour, and proteinase K (3µg/ml) treatment. Embryos were soaked in hybridization buffer for 2 hours at 65°C, and with digoxigenin RNA probe overnight at 65°C followed by block with 1% blocking reagent 2 hours and incubation with anti-digoxigenin-AP (1:2000) 6 hours incubation at room temperature. The color was developed by the solution containing 125 µg/ml BCIP and 250 µg/ml NBT in NTMT.

Western blot

Protein lysates purified from wild type and SUMO-1-Tg mouse hearts were subjected to gradient 4–12% NuPage SDS gel and transferred to PVDF membrane, which was subsequently probed with desired antibodies as indicated in figure legend. The protein bands were revealed by ECL plus (Buckinghamshire, UK).

Histopathology

Mouse neonatal hearts were dissected and fixed in 4% or 10% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for overnight, respectively. Sagittal sections of these hearts at 5 µm thickness were stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) according to standard protocols.

Microarray assay and reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

RNAs were extracted from wild type and SUMO-1 mutant mouse hearts via Trizol and subjected to microarray assays (OneArray Express) provided by Phalanx Biotech (Palo Alto, CA). RT-qPCR was also performed on the RNAs mentioned using specifically designed probes for the particular genes of our interest. 1 or 5 µg total RNAs were used for reverse transcription reaction using cloned reverse transcriptase purchased from Invitrogen (Chicago, IL), followed by quantitative PCR on machine MX3000 (Strategene). The sequences of oligos used in this study are available upon request.

Statistics

The unpaired Student’s t test, Chi-square test, or fisher’s exact test was applied to determine statistical significance between groups when applicable and shown in each Figure legend. P<0.05 was defined as significant and P<0.01 as very significant.

Results

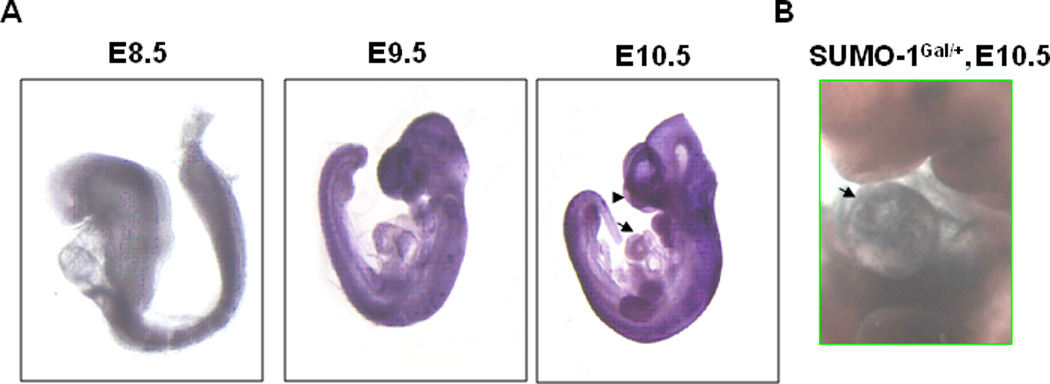

SUMO-1 transcripts were detected in the mouse developing hearts during embryogenesis

SUMO-1 transcripts appeared in the developing embryonic heart, by in situ hybridization assays performed using antisense against SUMO-1 mRNA on murine embryos at developmental stages, E8.5, E9.5, and E10.5 days. As shown in Fig. 1, SUMO-1 transcripts were detected virtually throughout the embryos with enhanced staining in the developing heart. Also, SUMO-1 transcripts were present in the craniofacial area (Fig. 1, arrow), consistent with the role of SUMO-1 in the development of craniofacial defects. Similarly, LacZ staining of the SUMO-1Gal/+ mouse was observed in embryonic heart at E10.5, shown in Fig. 1B.

Figure 1. SUMO-1 transcripts were detected in the developing hearts during mouse embryogenesis.

A. In situ hybridization was performed on mouse embryos at E8.5, E9.5, and E10.5 using antisense of SUMO-1 mRNA. Note that SUMO-1 transcripts were detected on the hearts and craniofacial region (arrow and arrowhead, respectively). B. LacZ staining truthfully revealed the endogenous SUMO-1 expression pattern in the heart. LacZ staining was performed on E10.5 of SUMO-1Gal/+ mouse embryo. The arrow indicated the positive staining in the heart.

SUMO-1 haploid and homozygous knockout mutant mice exhibited CHDs, ASD and VSDs

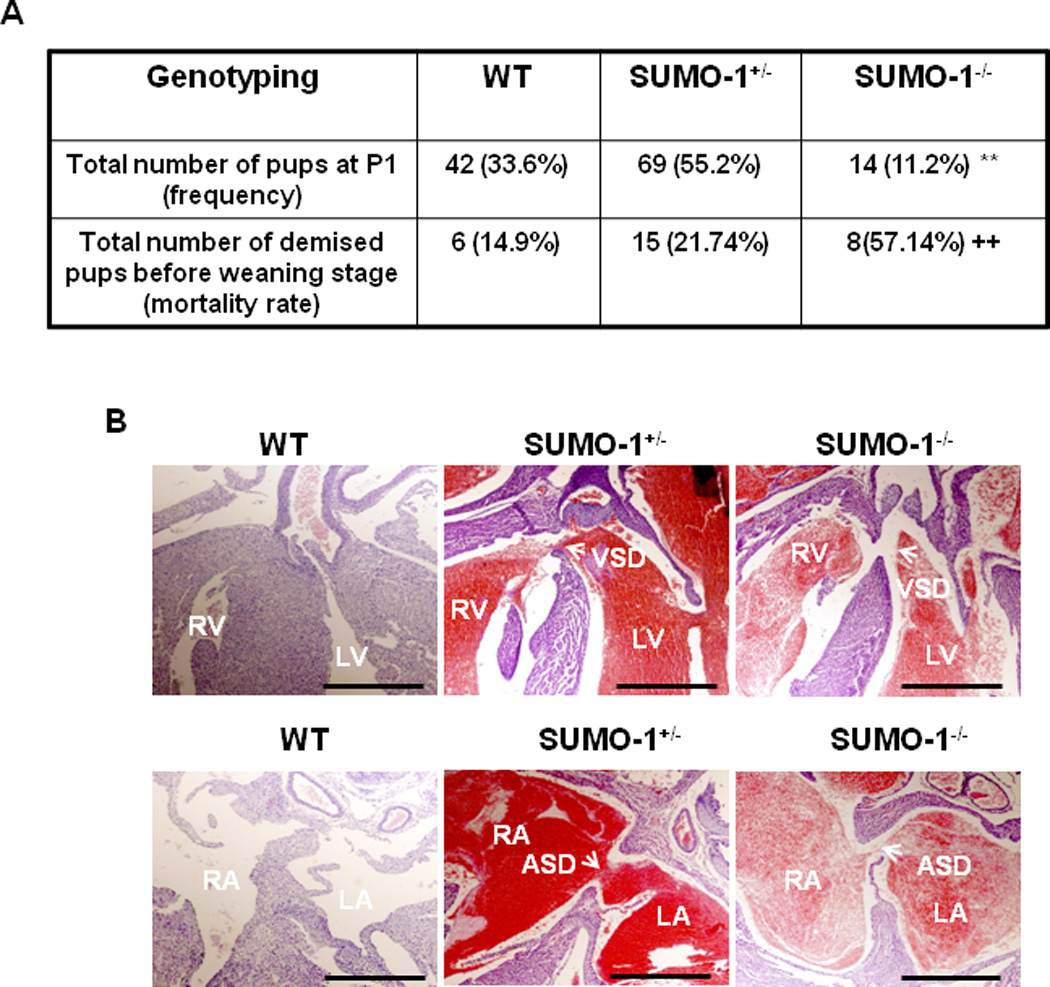

To uncover exclusive versus shared functions for SUMO isoforms, we tested SUMO-1 knockout mice provided by Dr. Michael Kuehn (Zhang et al., 2008a) on a mixed genetic background of 129P2/OlaHsd and C57BL6/J. We observed a reduced number of expected homozygous SUMO-1 new born mice (~14%, p<0.01) in comparison to the expected 25% Mendelian genetic rate (Fig. 2A), while the birth rate of SUMO-1+/− pups was equivalent to the expected rate of 50%. Also, SUMO-1−/− mice exhibited a high postnatal mortality rate of ~57% vs. ~22% for SUMO-1+/− and ~15% for wild type mice (p<0.01) (Fig. 2A). Histological examination of demised pups revealed CHDs including ASDs and/or VSDs in both SUMO-1 hetero- and homozygous mice Fig. 2B). Even though more than 50% of the new born SUMO-1−/− mice died immediately after birth, a subset of SUMO-1 null survivors showed growth retardation (data not shown). Incomplete phenotypic penetrance observed in the SUMO-1 null mice may indicate the effects of modifier gene(s) associated with mixed genetic backgrounds.

Figure 2. SUMO-1 mutant mice exhibited abnormal septogenesis.

A. P1 frequency of SUMO-1−/− mice was significantly lower than the expected Mendelian rate, and the mortality rate was higher compared with that of wild type (wt) mice. The data were compiled from 18 litters of totally 125 animals. **, p<0.01, Chi-square test was used; ++, p<0.01, Fisher’s exact test was used. B. Both prematurely demised hetero- and homozygous SUMO-1 mice showed ASD and/or VSD. Arrows indicated either an ASD or VSD, respectively. RV, right ventricle; LV, left ventricle; RA, right atrium; LA, left atrium; ASD, atrial septal defect; VSD, ventricular septal defect. Bar = 200 µm.

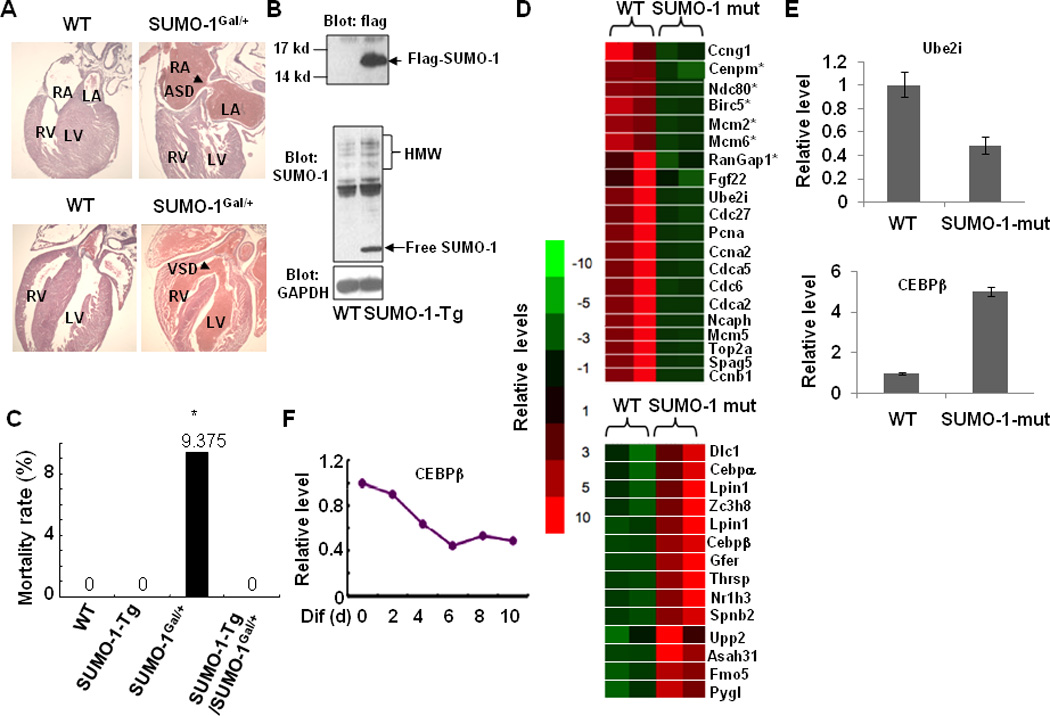

Similar cardiac phenotypes, ASD and VSD, were also observed in the heterozygous SUMO-1Gal/+ mice provided by Dr. Richard Maas (Alkuraya et al., 2006) (Fig. 3A). These SUMO-1 mutant mice were reported to display abnormal palatogenesis and to have immediate postnatal death (Alkuraya et al., 2006). To determine whether the high mortality rates observed in SUMO-1 mutant mice was due to the loss of SUMO-1 in cardiomyocytes, but not in the other tissues and or organs, we performed rescue experiments in which crosses were arranged between SUMO-1Gal/+ mice and SUMO-1-Tg mice. As shown in Fig. 3B, sumoylation assays revealed increased free SUMO-1 and SUMO-1 conjugates in SUMO-1-Tg mouse hearts, as expected. Also, SUMO-1-Tg mice did not exhibit any discernable cardiac phenotype(s) before the age of one month. The compound SUMO-1-Tg/SUMO-1Gal/+ mice presented significantly lower mortality rates in comparison with single SUMO-1Gal/+ mice (0% vs. 9.35% respectively, p<0.05). The reduced mortality rate in compound SUMO-1-Tg/SUMO-1Gal/+ mice corrected the high mortality rate rendered by SUMO-1 mutant mice. Given the fact that SUMO-1 conjugation regulates a variety of factors contributing to cardiogenesis (Wang and Schwartz, 2010), our findings suggest that SUMO-1 conjugation is critical for normal cardiac morphogenesis and highly likely dependent on the levels of SUMO-1. Reduced mortality due to rescue of the SUMO-1 null mice with the cardiac expressed SUMO-1 transgene (Fig. 3C) reinforces the concept that there is an optimal level of SUMO-1 for normal cardiac morphogenesis.

Figure 3. SUMO-1 mutants displayed cardiac dysgenesis.

A. SUMO-1Gal/+ mice exhibited ASDs/VSDs. Arrows indicated either an ASD or VSD, respectively. B. Generation of flag-tagged SUMO-1 Tg mice under control of cardiac α-MHC promoter (SUMO-1-Tg). Free flag-SUMO-1 (upper panel) and increased high molecular weight (HMW) conjugates of SUMO-1 (middle panel) were detected in SUMO-1-Tg mice. GAPDH (lower panel) served as a control. Western blots were performed on heart extracts from wild type and SUMO-1-Tg mice and labeled with indicated antibodies. C. Mortality rate of compound SUMO-1-Tg/SUMO-1Gal/+ mice was substantially decreased compared with that of single SUMO-1Gal/+ mice. The data were compiled from 17 litters with a total of 140 animals (wt, 30; SUMO-1-Tg, 32 SUMO-1Gal/+, 32; SUMO-1-Tg/SUMO-1Gal/+, 46). D. Down-regulated genes associated with cell proliferation (upper panel) and up-regulated liver-enriched genes (lower panel) in SUMO-1 mutant mouse hearts. Microarray assay on RNAs purified from SUMO-1 mutant and wild type mouse hearts were performed as described in the section of Materials and Methods. E. Verification of changes in several gene expressions shown in D by quantitative RT-PCR. F. Liver-enriched transcription factor C/EBPβ was suppressed in ES cells during EB formation.

SUMO-1 mutant mouse hearts exhibited dysregulation of genes critical for cell proliferation

Cell proliferation is an indispensable process for the completion of septation in the heart and sumoylation also plays a central role in mitotic chromosome structure, cell cycle progression, kinetochore function and cytokinesis (Ahuja et al., 2007; Dasso, 2008). For instance, SUMO modification of Topo II, enhanced by E3 ligase RanBP2 during mitosis, is required for proper localization to centromeres, which is essential for normal cell division (Dawlaty et al., 2008), and RanBP2-potentiated sumoylation of RanGAP1 is a prerequisite for k-fiber assembly in mitosis and when suppressed, causes miss-segregation of chromosomes (Arnaoutov et al., 2005). Transcription of RanGAP1 and DNA Topoisomerase II (TopoII), centrally important for cell division as SUMO substrates (Arnaoutov et al., 2005; Dawlaty et al., 2008), were down-regulated in the SUMO-1 mutant hearts (Fig. 3 D,E; upper panel). It is highly likely that the critical involvement of SUMO pathway in vertebrate cell proliferation may be responsible for defective cardiac septation in SUMO-1 knockout embryos.

Ecotopic expression of liver-enriched genes in SUMO-1 mutant mouse hearts

In SUMO-1 defective hearts, a number of liver-enriched transfactors, Cepbα and Cepbβ receptors, liver X receptor alpha (Nr1h3), Lpin1, growth factor, augmenter of liver regeneration (Gfer), thyroid hormone-inducible hepatic protein (Thrsp) genes were activated (Fig. 3D&E, lower panel). Expression of the liver restricted transcription factor C/EBPβ in embryonic stem cells repressed during embryoid body (EB) formation leading to beating cardiac myocytes may serve as an example of liver genes being silenced during heart cell differentiation (Fig. 3F). Informatics (EBI website CpG Plot program) revealed that 85% of the activated liver restricted genes including Cepbβ, harbor CpG islands that are potential sites for hypermethylation usually coupled with histone H3K27Me3 modification. Since SUMO-1 regulates a number of chromatin remodeling factors, such as the methyltransferase Ezh2 (Riising et al., 2008), and Pc2, a critical component of PCR1 that recognizes H3K27Me3, which is itself a SUMO E3 ligase and a likely target for sumoylation (Kagey et al., 2003). It appears that SUMO-1 may modulate the activity of chromatin remodeling complexes and subsequently inhibiting inappropriate gene activity, such as liver-enriched gene expression in the heart. Also, some of liver-enriched genes, such as CEBPβ, was shown involved in regulating cardiomyocyte proliferation (Bostrom et al., 2010).

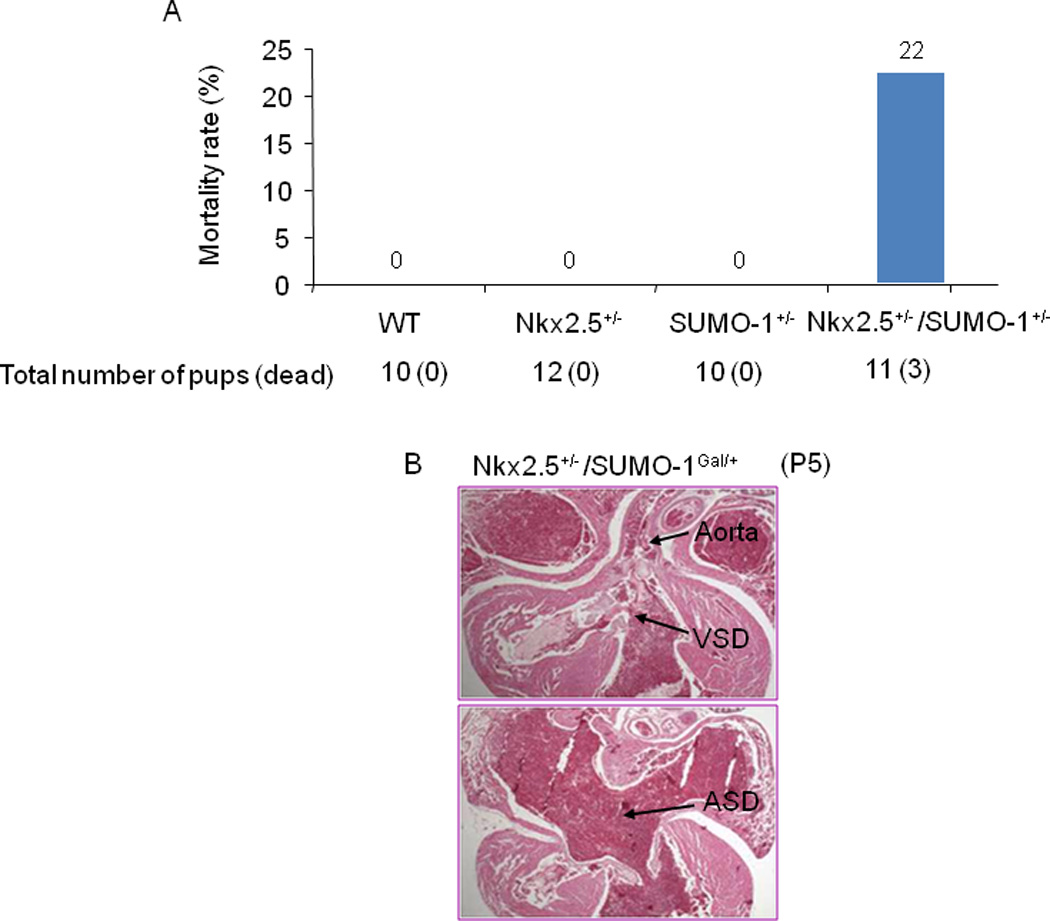

Potential genetic interaction between Nkx2.5 and SUMO-1

Nkx2.5, a cardiac specific homeodomain transcription factor and a SUMO substrate (Wang et al., 2008), plays a critical for normal cardiac morphogenesis. Since SUMO-1 knockout mice developed CHDs similar to those observed in patients whose Nkx2.5 gene was mutated, we asked if there was a functional interaction between Nkx2.5 and SUMO-1. The compound Nkx2.5+/−:SUMO-1Gal/+ mice were obtained via crossbreeding heterozygous Nkx2.5 and SUMO-1 mouse lines and subsequently analyzed. Fig. 4A shows a higher mortality rate in the compound Nkx2.5+/−:SUMO-1Gal/+ mouse group than any other genotypic group, although no statistical significance was reached due to the small sample size. The autopsy of these pups revealed the presence of severe ASDs and/or VSDs (Fig. 4B). This finding suggests a potential genetic inter-relationship between Nkx2.5 and the SUMO conjugation pathway.

Figure 4. Potential genetic interaction between Nkx2.5 and SUMO-1 genes.

A. Compound Nkx2.5+/−/SUMO-1Gal/+ mice exhibited higher mortality rates compared with those of single Nkx2.5+/− and SUMO-1Gal/+ mice. Total number (dead) of animals for analysis was shown. B. Histology of dead compound Nkx2.5+/−/SUMO-1Gal/+ mice revealed severe ASD/VSD. Representative data were shown.

Identification of mutations within the upstream promoter region of SUMO-1 gene in human patients with both cleft lip and ASDs

Given the findings that in human patients the deletion of the SUMO-1 gene was associated with an increased prevalence of oral-facial defects, and that defective sumoylation in murine fetuses caused ASDs and VSDs, we asked if SUMO-1 was mutated in human infants born with cleft palates and/or ASDs. We analyzed the genomic sequence of the human SUMO-1 gene in a cohort of newborns who were diagnosed with both atrial septal defects (ASD) and oro-facial clefts among live born (within 1 year after birth), and fetal deaths (≥20 weeks gestation) delivered to women residing in most California counties. Medical geneticists using detailed diagnostic information from medical records determined case eligibility. Each case was confirmed by review of echocardiography, cardiac catheterization, surgery, or autopsy records. Oro-facial clefts cases included infants with cleft palate only (CP) or with cleft lip with or without cleft palate (CLP), confirmed by surgery or autopsy. We analyzed the genomic sequence of human SUMO-1 gene in 87 cases and 100 controls from this California population. As represented in Fig. 5A, a A->G transition (designated as A-1239G) located 1239 bp upstream of the transcription start site was present in four independent cases (4.6%), but was not found in any of the controls (Fig. 5B, left panel). In addition, a 16 base substitution between 677 and 793 bp upstream of the transcription start site (designated as Mut-16) was present in one case (1.1%), but not in any controls (Fig. 5B, right panel). We feel that the 16 base substitutions between 677 and 793 bp upstream of the transcription start site (designated as Mut-16) is likely to be significant. However, the number of controls sequenced falls short of 3000 control sequences to conclude whether the nucleotide substitutions are one of many other SNPs, yet.

Figure 5. Sequence analysis of DNA from newborn screening blood spots revealed potential SUMO-1 regulatory promoter mutations in infants displaying both oral-facial clefts and ASDs.

A. Schematic representation of the locations of mutations relative to the transcription initiation site in the human SUMO-1 gene cis-regulatory region. B. Sequencing graphic revealing mutations in two different human SUMO-1 promoter regions with indicated positive/total number of patients. The observed DNA sequence variants were not detected in a total of 100 control samples. C. Luciferase reporter activity assays revealed ~95% and ~60% decrease in the activity of of mut-16 and A-1239G SUMO-1 promoter respectively, compared with that of wild type promoter. Data were obtained from four independent assays in HL-1 cell line, each carried out in duplicate. Student’s t test was used for statistical significance analysis. *P<0.05; **, P<0.001, compared with wt group.

To further evaluate the biological consequence of these mutations on SUMO-1 promoter activity, wild type (wt) human SUMO-1 promoter region (-1454 bps from transcription initiation site of human SUMO-1) was cloned and fused into a luciferase reporter construct pGL3-basic, and subsequently two mutants, A-1239G and Mut-16, were generated and designated as Mut-16-Luc and A-1239G-Luc, respectively. The assays of activity of wt promoter and its two mutants were performed via traditional transfection using transfection reagents in HL-1 cells, which is the only cardiogenic cell line that mimics the properties of differentiated cardiomyocytes (Claycomb et al., 1998; White et al., 2004). While A-1239G mutation decreased the activity of SUMO-1 promoter by ~60% (p<0.05), mut-16 only exhibited ~5% of the wild type promoter activity (p<0.001), (Fig. 5C); thus de facto reducing the balance of sumoylated target proteins potentially contributing to abnormal heart and craniofacial development.

Discussion

We showed that reduced levels of SUMO-1 led to premature death and CHDs—ASD and VSD in murine models, indicating an essential threshold level of SUMO-1 for normal cardiac structural development. Our findings were consistent with the previous report of immediate postnatal demise of SUMO-1 mutant mice (Alkuraya et al., 2006), but at the time was contrary to other two observations which stated no discernable phenotype(s) in SUMO-1 KO mice (Evdokimov et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2008a). The exact mechanisms underlying the phenotypic discrepancy of SUMO-1 KO mice is not well understood, but it is very likely that genetic modifiers associated with various mouse strains may play a role (Bentham and Bhattacharya, 2008; Biben et al., 2000; Winston et al., 2010). The successful rescue of SUMO-1 mutant mice by re-expressed SUMO-1 in cardiomyocytes indicates the importance of cell autonomous function of SUMO-1 in the high premature death rate and in the development of cardiac structural phenotypes. Although the underlying mechanisms governing the cardiac defects associated with SUMO-1 deficiency is currently unclear, defective cardiomyocyte proliferation may play a significant role. Furthermore, ectopic expression of some of the liver-enriched genes may also contribute to the cardiomyocyte propagation, as evidenced by the recent findings implicating the CEBPβ in cardiac growth (Bostrom et al., 2010).

SUMO conjugation contributes to normal cardiac morphogenesis through maximizing the activity of cardiac muscle-enriched factors via SUMO modification. A functional interaction between Nkx2.5 and SUMO-1 was supported by our observation of the significantly higher mortality of compound Nkx2.5+/−:SUMO-1Gal/+ mice compared with single mutant mice. We showed that sumoylation of two cardiogenic transcription factors Nkx2.5 and SRF enhanced their formation of more stable complexes further achieved by the presence of SUMO-1/PIAS1 (Wang et al., 2008). Our findings indicate that SUMO may modulate Nkx2.5 function via stimulation of complex protein-protein interaction. Thus, Nkx2.5 function appears to be modulated at least partially via sumoylation-induced changes in Nkx2.5-harboring complex formation. Reversible SUMO conjugation and deconjugation regulate the activities of cardiogenic transcription factors controlling cardiac morphogenesis and development. For example, mice with knockdowns of sumoylation pathway components, such as Ubc9, died at an early embryonic postimplantation stage (Nacerddine et al., 2005). More recently, Ubc9 was shown to be required for myotube formation in C2C12 cells and pharyngeal muscle development in Caenorhabditis elegans (Riquelme et al., 2006; Roy Chowdhuri et al., 2006); thus, implicating the sumoylation pathway in muscle development. We demonstrated that SUMO modification of GATA4 elicited cardiac muscle-specific gene expression (Wang et al., 2004), and myocardin sumoylation by SUMO-1/PIAS1 showed induced cardiogenic gene expression (Wang et al., 2007). Given the facts that transcription factors such as Nkx2.5, myocardin, SRF, and GATA4 are all SUMO targeted and physically interact with each other, and that all of them are crucial for heart development (Huang et al., 2009; Niu et al., 2008; Oka et al., 2006; Tanaka et al., 1999), taken together, these studies implicate the SUMO-1 conjugation pathway as having a role in cardiac development via altering the activities of cardiac enriched transcription factors.

Epigenetic regulation is essential for gene activation/silencing. A number of chromatin remodeling factors have been identified as SUMO conjugation substrates (David et al., 2002; Kirsh et al., 2002; Ling et al., 2004). In particular is Ezh2, a Histone 3 methyltransferase, which is also SUMO modified (Riising et al., 2008). Pc2, a critical component of polycomb repressive complex 1 (PRC1) that recognizes H3K27Me3, is also a SUMO E3 ligase and, by itself, is also a target for sumoylation (Kagey et al., 2003). Thus, the SUMO pathway governs transcription activation/silencing via modulating the activity of chromatin remodeling factors/complexes which is essential for cell fate determination. Recently, the murine SENP2 gene knockout caused defects in the embryonic heart and reduced the expression of Gata4 and Gata6 (Kang et al., 2010), which are essential for cardiac development (Liang et al., 2001; Zhao et al., 2008). SENP2 regulates transcription of Gata4 and Gata6, mainly through alteration of occupancy of Pc2/CBX4, a PRC1 subunit, on their promoters. Pc2/CBX4 is shown as a target of SENP2 in vivo. In SENP2 null embryos, sumoylated Pc2/CBX4 accumulates and Pc2/CBX4 occupancy on the promoters of target genes is markedly increased, leading to repression of Gata4 and Gata6 transcription (Kang et al., 2010). Thus, it is likely that altered sumoylation states in the heart, during either embryonic cardiac development or the maintenance of postnatal heart function, will promote abnormal gene expression leading to cardiac structural malformation and/or dysfunction of chromatin remodeling, such as observed here for the appearance of inappropriate liver-enriched genes in the hearts of SUMO-1 knockout mice. Whether and how the dysregulated liver-enriched genes contribute to the cardiac malformations warrants further investigation.

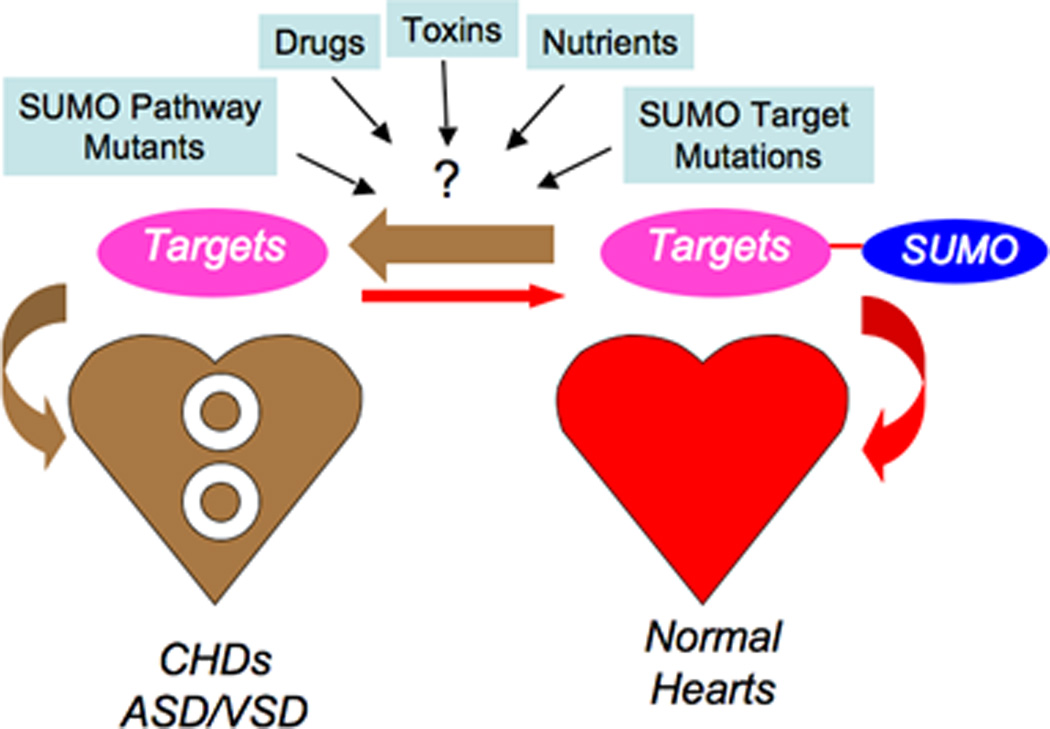

We have demonstrated that balanced sumoylation and de-sumoylation is required for normal cardiac development as modeled in Fig.6. These dynamic processes demand precise cooperation among a number of distinct signaling pathways and cardiac enriched factors. Our findings support the novel concept that a defective SUMO pathway as exemplified by our SUMO-1-KO mice, may contribute to the high prevalence of congenital cardiac defects. Reduction of SUMO-1 by half was sufficient to elicit in ASD/VSDs in SUMO-1 haploid-insufficient mice. Thus, SUMO conjugation pathway contributes to normal cardiac morphogenesis by maximizing the activity of cardiac muscle–enriched factors via SUMO modification for activation of cardiogenic genes, as well as repression of non-cardiogenic tissue activity. The association of the SUMO conjugation pathway with cardiac gene regulation is a relatively new area and the importance of the SUMO pathway for the development and maintenance of a normal cardiovascular system is just beginning to emerge. Hypothetically, genetic mutations of the individual SUMO conjugation pathway components and even the cardiac SUMO targets may generate similar CHD phenotypes accounting for the exceedingly high number of congenital birth defects observed around the world. Also, another important issue is whether environmental toxins, metabolites, and pharmaceuticals that may alter sumoylation gene activity cause heart disease. Any perturbation of signaling components and gene activity of SUMO conjugation pathway are the unknown intangibles that could tilt the balance of the SUMO conjugation pathway and potentially lead to cardiac structural malformations.

Figure 6.

Model of sumoylation conjugation - deconjugation pathway is highly complex yet under balance to promote normal cardiac development. Reduction of SUMO-1 by half elicited ASD/VSDs as in SUMO-1 haploid-insufficient mice may underscore other genetic defects of the individual SUMO conjugation pathway components and even the cardiac transfactor targets causing similar CHD phenotypes. Environmental toxins, nutrients and drugs may adversely affect the expression of SUMO pathway components.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Richard Maas for providing SUMO-1Gal/+ mouse line, and thank Dr. William Claycomb for providing HL-1 cardiomyocyte cell line. We are grateful for the technical support from Mrs Ling Qian. This work was supported in part by grants from the Texas Advanced Research Program and American Heart Association (J.W.) and the National Institute of Health (RJS, RF, GS).J.W. is also supported by a P30 grant from the National Institutes of Health as a Newly Independent Investigator (NII).

References

- Ahuja P, Sdek P, MacLellan WR. Cardiac myocyte cell cycle control in development, disease, and regeneration. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:521–544. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00032.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkuraya FS, Saadi I, Lund JJ, Turbe-Doan A, Morton CC, Maas RL. SUMO1 haploinsufficiency leads to cleft lip and palate. Science. 2006;313:1751. doi: 10.1126/science.1128406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnaoutov A, Azuma Y, Ribbeck K, Joseph J, Boyarchuk Y, Karpova T, McNally J, Dasso M. Crm1 is a mitotic effector of Ran-GTP in somatic cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:626–632. doi: 10.1038/ncb1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayaydin F, Dasso M. Distinct in vivo dynamics of vertebrate SUMO paralogues. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:5208–5218. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-07-0589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldini A. Dissecting contiguous gene defects: TBX1. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2005;15:279–284. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentham J, Bhattacharya S. Genetic mechanisms controlling cardiovascular development. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1123:10–19. doi: 10.1196/annals.1420.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biben C, Weber R, Kesteven S, Stanley E, McDonald L, Elliott DA, Barnett L, Koentgen F, Robb L, Feneley M, et al. Cardiac septal and valvular dysmorphogenesis in mice heterozygous for mutations in the homeobox gene Nkx2-5. Circ Res. 2000;87:888–895. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.10.888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostrom P, Mann N, Wu J, Quintero PA, Plovie ER, Panakova D, Gupta RK, Xiao C, MacRae CA, Rosenzweig A, et al. C/EBPbeta controls exercise-induced cardiac growth and protects against pathological cardiac remodeling. Cell. 2010;143:1072–1083. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruneau BG, Nemer G, Schmitt JP, Charron F, Robitaille L, Caron S, Conner DA, Gessler M, Nemer M, Seidman CE, et al. A murine model of Holt-Oram syndrome defines roles of the T-box transcription factor Tbx5 in cardiogenesis and disease. Cell. 2001;106:709–721. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00493-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claycomb WC, Lanson NA, Jr, Stallworth BS, Egeland DB, Delcarpio JB, Bahinski A, Izzo NJ., Jr HL-1 cells: a cardiac muscle cell line that contracts and retains phenotypic characteristics of the adult cardiomyocyte. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:2979–2984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.2979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasso M. Emerging roles of the SUMO pathway in mitosis. Cell Div. 2008;3:5. doi: 10.1186/1747-1028-3-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David G, Neptune MA, DePinho RA. SUMO-1 modification of histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) modulates its biological activities. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:23658–23663. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203690200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawlaty MM, Malureanu L, Jeganathan KB, Kao E, Sustmann C, Tahk S, Shuai K, Grosschedl R, van Deursen JM. Resolution of sister centromeres requires RanBP2-mediated SUMOylation of topoisomerase IIalpha. Cell. 2008;133:103–115. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evdokimov E, Sharma P, Lockett SJ, Lualdi M, Kuehn MR. Loss of SUMO1 in mice affects RanGAP1 localization and formation of PML nuclear bodies, but is not lethal as it can be compensated by SUMO2 or SUMO3. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:4106–4113. doi: 10.1242/jcs.038570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu C, Ahmed K, Ding H, Ding X, Lan J, Yang Z, Miao Y, Zhu Y, Shi Y, Zhu J, et al. Stabilization of PML nuclear localization by conjugation and oligomerization of SUMO-3. Oncogene. 2005;24:5401–5413. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg V, Kathiriya IS, Barnes R, Schluterman MK, King IN, Butler CA, Rothrock CR, Eapen RS, Hirayama-Yamada K, Joo K, et al. GATA4 mutations cause human congenital heart defects and reveal an interaction with TBX5. Nature. 2003;424:443–447. doi: 10.1038/nature01827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golebiowski F, Szulc A, Sakowicz M, Szutowicz A, Pawelczyk T. Expression level of Ubc9 protein in rat tissues. Acta Biochim Pol. 2003;50:1065–1073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman JI, Kaplan S. The incidence of congenital heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:1890–1900. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01886-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Min Lu M, Cheng L, Yuan LJ, Zhu X, Stout AL, Chen M, Li J, Parmacek MS. Myocardin is required for cardiomyocyte survival and maintenance of heart function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:18734–18739. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910749106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson ES. Protein modification by sumo. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:355–382. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.074118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagey MH, Melhuish TA, Wotton D. The polycomb protein Pc2 is a SUMO E3. Cell. 2003;113:127–137. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00159-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang X, Qi Y, Zuo Y, Wang Q, Zou Y, Schwartz RJ, Cheng J, Yeh ET. SUMO-specific protease 2 is essential for suppression of polycomb group protein-mediated gene silencing during embryonic development. Mol Cell. 2010;38:191–201. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirsh O, Seeler JS, Pichler A, Gast A, Muller S, Miska E, Mathieu M, Harel-Bellan A, Kouzarides T, Melchior F, et al. The SUMO E3 ligase RanBP2 promotes modification of the HDAC4 deacetylase. Embo J. 2002;21:2682–2691. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.11.2682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu T, Mizusaki H, Mukai T, Ogawa H, Baba D, Shirakawa M, Hatakeyama S, Nakayama KI, Yamamoto H, Kikuchi A, et al. SUMO-1 Modification of the Synergy Control Motif of Ad4BP/SF-1 Regulates Synergistic Transcription between Ad4BP/SF-1 and Sox9. Mol Endocrinol. 2004 doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0173. XXX. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Q, De Windt LJ, Witt SA, Kimball TR, Markham BE, Molkentin JD. The transcription factors GATA4 and GATA6 regulate cardiomyocyte hypertrophy in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:30245–30253. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102174200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling Y, Sankpal UT, Robertson AK, McNally JG, Karpova T, Robertson KD. Modification of de novo DNA methyltransferase 3a (Dnmt3a) by SUMO-1 modulates its interaction with histone deacetylases (HDACs) and its capacity to repress transcription. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:598–610. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki K, Minami T, Tojo M, Honda Y, Uchimura Y, Saitoh H, Yasuda H, Nagahiro S, Saya H, Nakao M. Serum response factor is modulated by the SUMO-1 conjugation system. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;306:32–38. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00910-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moses KA, DeMayo F, Braun RM, Reecy JL, Schwartz RJ. Embryonic expression of an Nkx2-5/Cre gene using ROSA26 reporter mice. Genesis. 2001;31:176–180. doi: 10.1002/gene.10022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay D, Dasso M. Modification in reverse: the SUMO proteases. Trends Biochem Sci. 2007;32:286–295. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nacerddine K, Lehembre F, Bhaumik M, Artus J, Cohen-Tannoudji M, Babinet C, Pandolfi PP, Dejean A. The SUMO pathway is essential for nuclear integrity and chromosome segregation in mice. Dev Cell. 2005;9:769–779. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie X, Deng CX, Wang Q, Jiao K. Disruption of Smad4 in neural crest cells leads to mid-gestation death with pharyngeal arch, craniofacial and cardiac defects. Dev Biol. 2008;316:417–430. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niessen K, Karsan A. Notch signaling in cardiac development. Circ Res. 2008;102:1169–1181. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.174318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu Z, Iyer D, Conway SJ, Martin JF, Ivey K, Srivastava D, Nordheim A, Schwartz RJ. Serum response factor orchestrates nascent sarcomerogenesis and silences the biomineralization gene program in the heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:17824–17829. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805491105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oka T, Maillet M, Watt AJ, Schwartz RJ, Aronow BJ, Duncan SA, Molkentin JD. Cardiac-specific deletion of Gata4 reveals its requirement for hypertrophy, compensation, and myocyte viability. Circ Res. 2006;98:837–845. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000215985.18538.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riising EM, Boggio R, Chiocca S, Helin K, Pasini D. The polycomb repressive complex 2 is a potential target of SUMO modifications. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2704. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riquelme C, Barthel KK, Qin XF, Liu X. Ubc9 expression is essential for myotube formation in C2C12. Exp Cell Res. 2008;312:2132–2141. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosas-Acosta G, Russell WK, Deyrieux A, Russell DH, Wilson VG. A universal strategy for proteomic studies of SUMO and other ubiquitin-like modifiers. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4:56–72. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400149-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy Chowdhuri S, Crum T, Woollard A, Aslam S, Okkema PG. The T-box factor TBX-2 and the SUMO conjugating enzyme UBC-9 are required for ABa-derived pharyngeal muscle in C. elegans. Dev Biol. 2006;295:664–677. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitoh H, Hinchey J. Functional heterogeneity of small ubiquitin-related protein modifiers SUMO-1 versus SUMO-2/3. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:6252–6258. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.9.6252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka M, Chen Z, Bartunkova S, Yamasaki N, Izumo S. The cardiac homeobox gene Csx/Nkx2.5 lies genetically upstream of multiple genes essential for heart development. Development. 1999;126:1269–1280. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.6.1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatham MH, Kim S, Jaffray E, Song J, Chen Y, Hay RT. Unique binding interactions among Ubc9, SUMO and RanBP2 reveal a mechanism for SUMO paralog selection. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:67–74. doi: 10.1038/nsmb878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan CJ, Basson CT. Molecular determinants of atrial and ventricular septal defects and patent ductus arteriosus. Am J Med Genet. 2000;97:304–309. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(200024)97:4<304::aid-ajmg1281>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vertegaal AC, Andersen JS, Ogg SC, Hay RT, Mann M, Lamond AI. Distinct and overlapping sets of SUMO-1 and SUMO-2 target proteins revealed by quantitative proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:2298–2310. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600212-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vertegaal AC, Ogg SC, Jaffray E, Rodriguez MS, Hay RT, Andersen JS, Mann M, Lamond AI. A proteomic study of SUMO-2 target proteins. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:33791–33798. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404201200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. SUMO conjugation and cardiovascular development. Front Biosci. 2009;14:1219–1229. doi: 10.2741/3304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Feng XH, Schwartz RJ. SUMO-1 modification activated GATA4-dependent cardiogenic gene activity. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:49091–49098. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407494200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Li A, Wang Z, Feng X, Olson EN, Schwartz RJ. Myocardin sumoylation transactivates cardiogenic genes in pluripotent 10T1/2 fibroblasts. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:622–632. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01160-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Schwartz RJ. Sumoylation and regulation of cardiac gene expression. Circ Res. 2010;107:19–29. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.220491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Zhang H, Iyer D, Feng XH, Schwartz RJ. Regulation of cardiac specific nkx2.5 gene activity by small ubiquitin-like modifier. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:23235–23243. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709748200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe TK, Fujiwara T, Kawai A, Shimizu F, Takami S, Hirano H, Okuno S, Ozaki K, Takeda S, Shimada Y, et al. Cloning, expression, and mapping of UBE2I, a novel gene encoding a human homologue of yeast ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes which are critical for regulating the cell cycle. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1996;72:86–89. doi: 10.1159/000134169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei L, Roberts W, Wang L, Yamada M, Zhang S, Zhao Z, Rivkees SA, Schwartz RJ, Imanaka-Yoshida K. Rho kinases play an obligatory role in vertebrate embryonic organogenesis. Development. 2001;128:2953–2962. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.15.2953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White SM, Constantin PE, Claycomb WC. Cardiac physiology at the cellular level: use of cultured HL-1 cardiomyocytes for studies of cardiac muscle cell structure and function. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H823–H829. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00986.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winston JB, Erlich JM, Green CA, Aluko A, Kaiser KA, Takematsu M, Barlow RS, Sureka AO, LaPage MJ, Janss LL, et al. Heterogeneity of genetic modifiers ensures normal cardiac development. Circulation. 2010;121:1313–1321. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.887687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu JC, Child JS. Common congenital heart disorders in adults. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2004;29:641–700. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh ET. SUMOylation and de-SUMOylation: Wrestling with life's processes. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:8223–8227. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800050200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh ET, Gong L, Kamitani T. Ubiquitin-like proteins: new wines in new bottles. Gene. 2000;248:1–14. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00139-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang FP, Mikkonen L, Toppari J, Palvimo JJ, Thesleff I, Janne OA. Sumo-1 function is dispensable in normal mouse development. Mol Cell Biol. 2008a;28:5381–5390. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00651-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XD, Goeres J, Zhang H, Yen TJ, Porter AC, Matunis MJ. SUMO-2/3 modification and binding regulate the association of CENP-E with kinetochores and progression through mitosis. Mol Cell. 2008b;29:729–741. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao R, Watt AJ, Battle MA, Li J, Bondow BJ, Duncan SA. Loss of both GATA4 and GATA6 blocks cardiac myocyte differentiation and results in acardia in mice. Dev Biol. 2008;317:614–619. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]