Abstract

Objective Our primary objective was to assess the difference in amino and fatty acid biomarkers throughout pregnancy in women with and without obesity. Interactions between biomarkers and obesity status for associations with maternal and fetal metabolic measures were secondarily analyzed.

Methods Overall 39 women (15 cases, 24 controls) were enrolled in this study during their 15- to 20-weeks' visit at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics. We analyzed 32 amino acid and acylcarnitine concentrations with tandem mass spectrometry for differences throughout pregnancy as well as among women with and without obesity (body mass index [BMI] ≥ 35, BMI < 25).

Results There were substantial changes in amino acids and acylcarnitine metabolites between the second and third trimesters (nonfasting state) of pregnancy that were significant after correcting for multiple testing (p < 0.002). Examining differences by maternal obesity, C8:1 (second trimester) and C2, C4-OH, C18:1 (third trimester) were higher in women with obesity compared with women without obesity. Several metabolites were marginally (0.002 < p < 0.05) correlated with birth weight, maternal glucose, and maternal weight gain stratified by obesity status and trimester.

Conclusions Understanding maternal metabolism throughout pregnancy and the influence of obesity is a critical step in identifying potential mechanisms that may contribute to adverse outcomes in pregnancies complicated by obesity.

Keywords: acylcarnitines, fatty acids, amino acids, maternal obesity, pregnancy, longitudinal

Obesity has reached pandemic proportions, with the worldwide prevalence nearly doubling since 1980.1 Individuals with obesity have been shown to be at an increased risk of developing chronic metabolic and cardiovascular diseases such as type-2 diabetes mellitus, coronary heart disease, and stroke.2 3 With the number of people affected growing at an exponential rate, much focus has been placed on understanding the biological mechanisms related to obesity and its associated comorbidities. Recent studies have identified differences in circulating metabolic biomarkers between individuals with and without obesity that could be targeted for clinical intervention.2 4 5 6

Obesity is of particular concern during pregnancy, when both the mother and developing fetus are at risk for complications. An estimated one-third of all pregnancies are complicated by obesity, and maternal obesity has been identified as one of the leading causes of the unprecedented increase in obstetrical mortality seen over the last decade.2 7 Women with obesity are at an increased risk of obstetric complications, including gestational diabetes mellitus, preeclampsia, and thromboembolic events.2 Diagnosis and intervention for gestational diabetes, a condition that often coexists with obesity, has been successful in reducing pregnancy complications and maternal mortality. However, intervention leading to a decreased risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes due to overweight and obesity in women without gestational diabetes has not yet been successfully introduced during pregnancy. Nutritional intervention can be successfully implemented before and continuing during pregnancy. While recent reports identify promising metabolic markers involved in obesity that may be targets of intervention, these studies were not performed in pregnant women where the maternal metabolome is a fusion of fetal and maternal metabolic outcomes.2 7

Many metabolic adaptations occur during pregnancy that are essential to ensure adequate growth and development of the fetus while meeting the increased energy demands on the mother.8 While specific metabolites such as glucose and lipids undergo striking changes beginning early in pregnancy, less is known about the changes that occur in the intermediate metabolites involved in glucose and lipid metabolic pathways and how obesity status may affect these changes.8 Understanding maternal metabolism throughout pregnancy and the influence of maternal obesity is a critical step in identifying potential pathways and mechanisms that may contribute to pregnancy complications and poor infant outcomes in pregnancies complicated by obesity.

Our primary objective was to assess the difference in amino and fatty acid biomarkers throughout pregnancy in women with and without obesity. Our secondary aims were to assess interactions between biomarkers and obesity status for associations with maternal glucose, maternal weight gain, and infant birth weight. We hypothesize that amino acid and fatty acid profiles will differ between trimesters among women with and without obesity. In addition, we speculate that the association between biomarkers and maternal and fetal metabolic measures will differ according to the obesity status.

Methods

Study Population

Women were enrolled in this study during their 15- to 20-weeks' visit to the Obstetrics Clinic at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics in Iowa City, IA. Enrollment occurred between March 2012 and August 2013. Women aged 18 to 45 who were between 15 and 20 weeks' of pregnancy with a singleton gestation and prepregnancy body mass index (BMI) of < 25 or ≥ 35 were eligible for this study. BMI categories were defined according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention standards.9 Exclusion criteria included type-1 diabetes, infectious diseases (human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B/C, and syphilis), autoimmune diseases and known metabolic disease or fetal anomaly. Additional exclusion criteria for subjects with BMI < 25 included type-2 diabetes, hypertension, thyroid disease, or other chronic illness. Because these conditions are closely associated with metabolic disease, women with obesity who were diagnosed with type-2 diabetes, hypertension, or gestational diabetes were included in the study sample. Study protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Iowa (IRB no.: 201112755). Overall, 42 women were eligible to participate in this study. Three women withdrew after the first visit and were not included in the final analyses. The final sample population included 39 women, 24 women without obesity (BMI: 18–25) and 15 women with obesity (BMI: ≥ 35).

Sample Collection and Preparation

At enrollment (15–20 weeks' of gestation) subjects completed a brief food questionnaire to indicate when and what they had eaten in the last 4 hours, an extra tube of blood was drawn along with their routine obstetrics laboratories and fresh blood was spotted on Whatman 903 filter paper card (GE Healthcare Ltd, Cardiff, UK), dried at room temperature then stored at −80°C. Prepregnancy BMI was calculated using weight and height measurements recorded by nurses in patient medical charts (all measurements were recorded before 15 weeks' of gestation). Information on age at delivery, race/ethnicity, gestational age, infant birth weight, maternal weight gain, and infant gender were abstracted from the patient medical charts by research team members. Maternal weight gain was calculated using weight measurements recorded by nurses in patient medical charts before 15 weeks' of gestation and at the time of delivery.

Glucose and Metabolite Measurements

Glucose was measured at each visit with the Accu-Check system (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Subjects identified as being eligible for study participation at the first study visit returned fasted for a follow-up visit 1 to 8 days later. Women who had not eaten within 4 hours of sample collection were considered fasted. A third blood sample was collected at the time of the subjects' oral glucose tolerance test which was performed between the 26th and 30th weeks' of pregnancy. Samples were prepared and handled at the State of Iowa Hygienic Laboratory according to the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines10 in a similar fashion as those reported previously for routine newborn screening.11

A total of 43 metabolites, including 11 amino acids, 31 acylcarnitines, and free carnitine, were measured using tandem mass spectrometry. Of these metabolites, 11 had low variability (standard deviation < 0.01) among subjects and were excluded from analysis (Table 1, Supplementary Material available in the online version only). Tandem mass spectrometry was performed with the Waters Quattro Micro triple quadrupole tandem mass spectrometer (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA), equipped with an electrospray ionization source operated in the positive ion mode.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS 9.3 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Demographic and clinical characteristics of our cohort were compared between women with and without obesity with Fisher exact tests for dichotomous or categorical exposures and Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney tests for continuous exposures. All metabolite values were natural log transformed to account for the nonnormality in their distribution. Metabolites that had noncontinuous distributions were categorized into quantiles that grouped observations as evenly as possible.

Measurements were compared between trimesters and between the fasted and nonfasted state for all women using a linear mixed-effects regression with maximum-likelihood estimation for continuous metabolites and an unstructured random effects covariance matrix. Mixed-effects cumulative logistic regression was used for categorical metabolites with an independent random effects correlation matrix. Measurements were compared between women with and without obesity, for each trimester using general linear regression for continuous metabolites and logistic regression for categorical metabolites.

The p values were adjusted for using the Bonferroni correction. Spearman rank correlation test was used to assess the correlation between each metabolite and maternal glucose levels, maternal weight gain, and infant birth weight in women with and without obesity separately. Because little variation in gestational age at birth was present in the study population (the vast majority of infants were born term), birth weight was not adjusted for gestational age. Maternal glucose, maternal weight gain, and infant birth weight were separately regressed on significant metabolites, obesity status, and the interaction between the metabolite and obesity. All analyses were performed stratified by trimester using the nonfasted samples.

Results

A total of 10 amino acids, 21 acylcarnitines, and free carnitine were examined in 39 women, 24 without obesity (BMI: 18–25) and 15 with obesity (BMI: ≥ 35). The majority of women in our study were non-Hispanic, white women with a term delivery of an infant of average birth weight (Table 1). None of the women without obesity in this study were diagnosed with type-2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, or gestational diabetes mellitus. Six women with obesity had existing hypertension and two had existing type-2 diabetes mellitus, none developed gestational diabetes mellitus. Nonfasted second- and third-trimester glucose measurements were marginally higher in women with obesity compared with women without obesity, while fasting glucose measurements were significantly higher in women with obesity. Weight gain during pregnancy was significantly higher for women without obesity compared with women with obesity.

Table 1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Study Population.

| Characteristics | Women without obesity (N = 24) | Women with obesity (N = 15) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at delivery, y | 31.1 ± 1.7 | 30.3 ± 4.9 | 0.85 |

| Prepregnancy BMI | 21.8 ± 1.9 | 42.9 ± 5.0 | < 0.01a |

| Race/ethnicityb | 0.44 | ||

| White | 22 (91.7) | 13 (86.7) | |

| Asian | 1 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Hispanic | 1 (4.2) | 2 (13.3) | |

| Gestational age second trimester, d | 128.0 ± 11.9 | 123.1 ± 12.5 | 0.19 |

| Gestational age second trimester (fasting), dc | 131.4 ± 11.9 | 126.9 ± 12.7 | 0.35 |

| Gestational age third trimester, d | 193.0 ± 5.5 | 192.9 ± 5.7 | 0.60 |

| Gestational age at delivery, d | 279.3 ± 6.2 | 270.7 ± 18.5 | 0.19 |

| Glucose second trimester | 83.6 ± 7.2 | 98.3 ± 24.4 | 0.02a |

| Glucose second trimester (fasting)a | 82.2 ± 10.5 | 98.9 ± 23.3 | < 0.01a |

| Glucose third trimester | 104.5 ± 17.7 | 124.7 ± 34.6 | 0.04a |

| Infant birth weight, g | 3,404.2 ± 335.1 | 3,358.1 ± 651.9 | 0.77 |

| Maternal weight gain, lb | 29.5 ± 11.5 | 20.7 ± 12.9 | 0.03a |

| Infant genderb | 0.51 | ||

| Male | 9 (37.5) | 8 (53.3) | |

| Female | 15 (62.5) | 7 (46.7) |

Abbreviations: ANOVA, analysis of variance; BMI, body mass index; SD, standard deviation.

Note: Mean ± SD and N (%) were calculated using untransformed variables. ANOVA was done using log transformed variables.

Statistically significant at α < 0.05.

Data are expressed as N (%). All other data are expressed as mean ± SD.

28 (n = 19 without obesity and n = 9 with obesity) women returned for a fasting visit.

Of the 39 participating women, 28 (72%) had eaten within 4 hours of the first visit and returned fasted for at least 4 hours 1 to 8 days later for the second visit. A few metabolites (C8, C10, C10:1,C12:1, and C14:1) differed in concentration by whether the sample was collected in the fasted or nonfasted state, accounting for the number of tests performed and adjusting for gestational age at the time of blood draw (p > 0.002) (Table 2, Supplementary Material available in the online version only). These metabolites were removed from further analyses.

There were substantial changes in amino acids and acylcarnitine metabolites between the second and third trimesters (nonfasted state) of pregnancy that were significant after correcting for multiple testing (p < 0.002) (Table 2). Specifically, levels of leucine, methionine, phenylalanine, tyrosine, valine, free carnitine, C2, C4, C5, C5-OH, C6, C12, C18, C18:1, and C18:2 were all markedly lower in the third trimester compared with the second trimester of pregnancy. Conversely, glutamate levels were found to be significantly higher in the third trimester compared with the second.

Table 2. Changes in metabolite measures from second to third trimester of pregnancy.

| Second trimesterc

N = 39 |

Third trimesterc

N = 39 |

Second vs. third trimester p Values |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| ALA | 159.39 ± 32.38 | 157.25 ± 29.69 | 0.80 |

| ARG | 6.56 ± 2.48 | 6.43 ± 3.08 | 0.50 |

| CIT | 12.29 ± 2.92 | 11.15 ± 2.47 | 0.01 |

| GLU | 75.91 ± 16.56 | 90.55 ± 21.02 | 1.2 × 10−4 a |

| LEU | 87.05 ± 23.38 | 66.78 ± 20.34 | 6.8 × 10−6 a |

| MET | 13.04 ± 3.59 | 11.19 ± 2.99 | 3.4 × 10−3 |

| ORN | 17.00 ± 3.69 | 17.95 ± 4.46 | 0.32 |

| PHE | 42.02 ± 9.09 | 36.67 ± 6.47 | 1.5 × 10−3 a |

| TYR | 35.36 ± 10.92 | 29.35 ± 7.72 | 7.9 × 10−4 a |

| VAL | 119.80 ± 27.21 | 93.18 ± 21.51 | 1.8 × 10−6 a |

| C0 | 13.61 ± 3.06 | 11.46 ± 2.18 | 2.8 × 10−6 a |

| C2 | 8.34 ± 1.79 | 7.58 ± 2.14 | 6.2 × 10−4 a |

| C3 | 1.14 ± 0.31 | 1.06 ± 0.37 | 0.03 |

| C4 | 0.18 ± 0.06 | 0.13 ± 0.04 | 5.2 × 10−7 a |

| C4-DC | 0.25 ± 0.10 | 0.23 ± 0.08 | 0.30 |

| C4-OHb | 0.02 | ||

| Q1 (= 0.03 μmol/L) | 6 (15.38) | 9 (23.08) | |

| Q2 (= 0.04 μmol/L) | 12 (30.77) | 16 (41.03) | |

| Q3 (= 0.05 μmol/L) | 12 (30.77) | 8 (20.51) | |

| Q4 (≥ 0.06 μmol/L) | 9 (23.08) | 6 (15.38) | |

| C5 | 0.07 ± 0.02 | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 1.2 × 10−3 a |

| C5-OH | 0.14 ± 0.06 | 0.12 ± 0.06 | 8.2 × 10−7 a |

| C6b | 2.8 × 10−4 a | ||

| Q1 (= 0.01 μmol/L) | 2 (5.13) | 8 (20.51) | |

| Q2 (= 0.02 μmol/L) | 8 (20.51) | 15 (38.46) | |

| Q3 (= 0.03 μmol/L) | 14 (35.90) | 11 (28.21) | |

| Q4 (≥ 0.04 μmol/L) | 15 (38.46) | 5 (12.82) | |

| C8:1 | 0.05 ± 0.02 | 0.04 ± 0.03 | 0.01 |

| C12b | 8.4 × 10−6 a | ||

| Q1 (≤ 0.02 μmol/L) | 6 (15.38) | 22 (56.41) | |

| Q2 (= 0.03 μmol/L) | 17 (43.59) | 13 (33.33) | |

| Q3 (= 0.04 μmol/L) | 9 (23.08) | 4 (10.26) | |

| Q4 (≥0.05 μmol/L) | 7 (17.95) | 0 (0) | |

| C14b | 0.36 | ||

| Q1 (≤ 0.05 μmol/L) | 7 (17.95) | 13 (33.33) | |

| Q2 (= 0.06 μmol/L) | 14 (35.90) | 9 (23.08) | |

| Q3 (= 0.07 μmol/L) | 8 (20.51) | 9 (23.08) | |

| Q4 (≥ 0.08 μmol/L) | 10 (25.64) | 8 (20.51) | |

| C16 | 0.63 ± 0.16 | 0.58 ± 0.15 | 0.03 |

| C16:1b | 0.14 | ||

| Q1 (≤ 0.02 μmol/L) | 7 (17.95) | 7 (17.95) | |

| Q2 (= 0.03 μmol/L) | 13 (33.33) | 19 (48.72) | |

| Q3 (= 0.04 μmol/L) | 9 (23.08 | 8 (20.51) | |

| Q4 (≥ 0.05 μmol/L) | 10 (25.64) | 5 (12.82) | |

| C18 | 0.36 ± 0.11 | 0.30 ± 0.07 | 1.6 × 10−6 a |

| C18:1 | 0.61 ± 0.15 | 0.50 ± 0.14 | 6.2 × 10−7 a |

| C18:2 | 0.22 ± 0.05 | 0.18 ± 0.05 | 4.8 × 10−6 a |

Abbreviation: ALA, alanine; ARG, arginine; CIT, citrulline; GLU, glutamic acid; LEU, leucine; MET, methionine; ORN, ornithine; PHE, phenylalanine; SD, standard deviation; TYR, tyrosine; VAL, valine.

Note: Mean ± SD were calculated using nontransformed variables. Linear (continuous metabolites) and cumulative logistic (categorical metabolites) mixed-effects regression was performed using log-transformed variables.

Statistically significant at α < 0.002.

Data are expressed as N (%). All other data are expressed as mean ± SD.

Metabolites were measured in μmol/L.

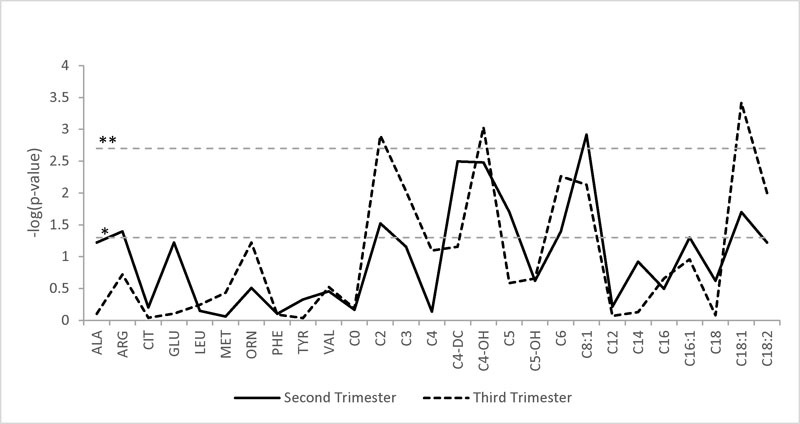

Examining differences by maternal obesity, C8:1 was found to be significantly higher in women with obesity compared with women without obesity for second trimester nonfasted women, after correcting for multiple testing (p < 0.002) (Fig. 1 and Table 3, Supplementary Material available in the online version only). A similar trend was observed in women in their third trimester, with women, with obesity showing significantly higher measurements for C2, C4:OH, and C18:1 than women without obesity, after correcting for multiple testing.

Fig. 1.

Differences in metabolite measurements by maternal obesity status. The X-axis is a list of all metabolites. The Y-axis is the −log10 of the p value from the regression analyses. The horizontal dashed lines represent the p-value cutoffs. *p value = 0.05; **p value = 2.00 × 10−3.

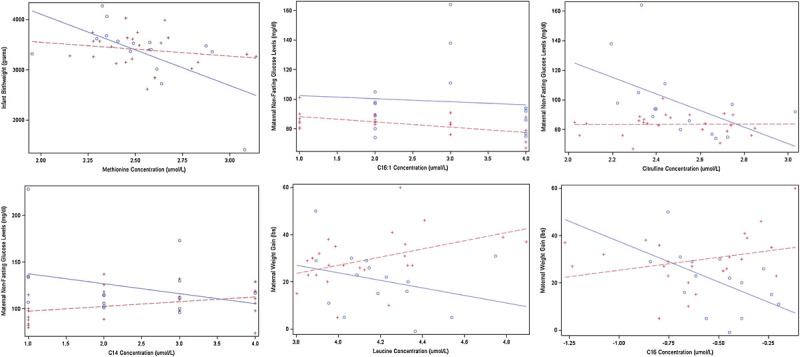

Several metabolites were marginally (0.002 < p < 0.05) correlated with birth weight, maternal glucose, and maternal weight gain stratified by obesity status and trimester (Tables 4–6, Supplementary Material available in the online version only); however, none met the correction for multiple testing thresholds (p < 0.002). Notably, a significant interaction between second-trimester methionine levels and obesity was associated with infant birth weight (Table 7, Supplementary Material available in the online version only and Fig. 2). Levels of methionine were associated with lower birth weight in both women with and without obesity, with the negative relationship being more pronounced in women with obesity (p = 0.04).

Fig. 2.

Significant interactions between obesity status and metabolites for birth weight, glucose, and maternal weight gain outcomes. Women with obesity are represented by the circles and solid lines. Women without obesity are represented by the plus signs and dashed lines.

Interactions between citrulline, C14, and C16:1 with obesity were significantly associated with maternal glucose levels (Table 7, Supplementary Material available in the online version only and Fig. 2). In the second trimester higher C16:1 levels were associated with significantly lower glucose levels for women without obesity (p = 4.6 × 10−6), while higher citrulline levels were associated with lower glucose levels in women with obesity but not women without obesity (p = 0.01). In the third trimester, higher C14 levels were associated with higher glucose levels for women without obesity and lower glucose levels for women with obesity (p = 0.02).

In assessing associations with maternal weight gain, interactions between leucine and C16 with obesity were found to have a significant relationship (Table 7, Supplementary Material available in the online version only and Fig. 2). In the third trimester, higher leucine levels were associated with increased maternal weight gain for women without obesity and decreased weight gain for women with obesity (p = 0.04). This effect was also observed for C16 (p = 0.01).

Discussion

Metabolic adaptations during pregnancy are necessary to ensure adequate nutrient supply for both the developing fetus and mother. This metabolic balance is well understood for lipid metabolism and glucose, through which clinical conditions, such as hyperlipidemia and gestational diabetes, can complicate pregnancy.8 Intermediates of glucose and lipid metabolism, including branched-chain amino acid metabolites and carnitine levels, have been reported to decline during pregnancy but little has been documented on specific amino acid and acylcarnitine species throughout pregnancy, particularly with respect to maternal obesity.8 12 We identified substantial changes in several amino acids and acylcarnitine metabolites from the second to third trimester in pregnancy, both supporting and expanding on the findings from previous studies.

Importantly, we noted the little difference between analyte measurements in the fasted or nonfasted state. While it is recognized that serum levels of amino acids and acylcarnitine measurements are sensitive to fasting,13 our data demonstrate that whole blood measurement collected as dried blood spots during routine obstetric care are relatively stable regardless of a fasting or nonfasting state. This suggests that screening amino acid and acylcarnitine levels using procedures similar to routine newborn screening may offer a cost-effective and efficient method for monitoring fatty acid and amino acid levels during pregnancy. Although future studies measuring metabolic levels after a longer duration of fasting (8–10 hours) may be ideal, the dietary needs of pregnant women limit the ability of researchers to impose such strict criteria.

We identified several acylcarnitine species that differed between women with and without obesity, particularly in the third trimester of pregnancy. Notably, women with obesity in our study had higher levels of C2, C4-OH, and C18:1 than women without obesity. This expounds on previous findings illustrating that the normal reduction in peripheral insulin sensitivity observed in late gestation is reduced in obese women, contributing to increased circulatory levels of metabolic fuels, including glucose, lipids, and amino acids.14 15

Although two prior studies have assessed the association between BMI and fatty acid concentration in pregnant women, the cross-sectional design of these studies restricted them from drawing conclusions about the directionality of the relationship.16 17 In addition, to being able to assess changes in metabolite levels across pregnancy trimesters, we were able to more broadly assess differences between specific acylcarnitine species (such as short, medium, and long-chain acylcarnitines) in pregnant women with and without obesity, which has, to our knowledge, not previously been performed.

An increase in long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids has been seen in women with pregnancy-induced hypertension compared with normotensive women, with the difference occurring later in pregnancy.18 We found increased C18:1 level in women with obesity in both the second and third trimester with a more marked difference in the third trimester. Higher baseline blood pressure and hypertension are comorbidities of obesity; in fact, 40% of the women with obesity in our study had existing hypertension. Because fetal circulation is compromised in hypertensive women, overcompensation of fatty acids can occur to ensure an adequate supply of nutrients is provided to the fetus.19 While, due to sample size, we could not tease apart the effects of hypertension from those of obesity, this mechanism could be a plausible explanation for the higher levels of long-chain acylcarnitines in the women with obesity in our study.

Several metabolites were marginally correlated with birth weight, maternal glucose, and maternal weight gain stratified by obesity status and trimester. For example, a significant interaction between second-trimester methionine levels and obesity was associated with infant birth weight. These results are consistent with recent studies that found that increased maternal serum homocysteine levels, a metabolite of methionine, were associated with low birth weight.20 21 22 23 24 We found that higher levels of maternal methionine were associated with lower birth weight in women with obesity but not in women without obesity.

The relationship between several metabolites and maternal metabolic measures (i.e., glucose levels and weight gain) were also found to differ by obesity status. Both increased prepregnancy BMI and increased gestational weight gain, regardless of prepregnancy BMI have been associated with dyslipidemia and insulin resistance during pregnancy through the accumulation of visceral fat.15 16 Normal circulatory increases in metabolic fuels, such as glucose, amino acids, and free fatty acids, are often exaggerated as a consequence of obesity-impaired insulin resistance.15 In line with previous research, we saw increased glucose levels among women with obesity in both the second trimester, fasting and nonfasting states, and third trimesters and decreased maternal weight gain among women with obesity compared with women without obesity. The relationship between several metabolites and maternal weight gain and glucose levels differed significantly depending on maternal obesity status. This indicates that the effect of maternal glucose levels and weight gain on metabolic disruption during pregnancy may not be acting independent of prepregnancy BMI.

While our findings add considerable knowledge to the present state of research on this topic, we acknowledge that there are limitations to our study findings. With a small sample size, we may have been underpowered to detect several important associations. For example, branched chain amino acids have been suggested as markers that differentiate subjects with and without obesity,7 but in our pregnant population, we did not detect these differences. In addition, due to a relatively homogenous population of non-Hispanic white women from a single hospital clinic, the generalizability of our findings may be hindered. The exclusion criteria were altered for cases, allowing women with obesity with type-2 diabetes, hypertension, thyroid disease, or other chronic diseases to be included in the sample population, which could induce a selection bias. However, these conditions are common comorbidities of obesity and are difficult to disentangle particularly during pregnancy when the maternal metabolome is in constant flux.

In light of our preliminary findings, further investigation into the impact of obesity on maternal metabolism is warranted. Large longitudinal metabolic profiling studies are needed to evaluate the influence of maternal metabolism such as amino acids and acylcarnitines on pregnancy (weight gain, pregnancy complications) and neonatal birth outcomes (birth weight, gestational age). In addition, further investigation of the microbiome during pregnancy and the impact on fatty acid metabolism in relationship to obesity will be important for identifying other potential targets for intervention including pro- or antibiotics.

Acknowledgments

We express our thanks to Stanton Berberich and Michael Ramirez at the State of Iowa Hygienic Laboratory for their experience in sample management and amino acid and acylcarnitine measurements. We would also like to thank Jeffrey C Murray for his significant input on the design and implementation of this project. Research reported in this publication was supported in part by funds from the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Iowa and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under award number R00HD065786. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Obesity and Overweight Geneva, Switzerland. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/. Accessed 2015

- 2.Oberbach A, Blüher M, Wirth H. et al. Combined proteomic and metabolomic profiling of serum reveals association of the complement system with obesity and identifies novel markers of body fat mass changes. J Proteome Res. 2011;10(10):4769–4788. doi: 10.1021/pr2005555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Gaal L F, Mertens I L, De Block C E. Mechanisms linking obesity with cardiovascular disease. Nature. 2006;444(7121):875–880. doi: 10.1038/nature05487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park S, Sadanala K C, Kim E K. A Metabolomic Approach to Understanding the Metabolic Link between Obesity and Diabetes. Mol Cells. 2015;38(7):587–596. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2015.0126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.He Q, Ren P, Kong X. et al. Comparison of serum metabolite compositions between obese and lean growing pigs using an NMR-based metabonomic approach. J Nutr Biochem. 2012;23(2):133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams R, Lenz E M, Wilson A J. et al. A multi-analytical platform approach to the metabonomic analysis of plasma from normal and Zucker (fa/fa) obese rats. Mol Biosyst. 2006;2(3–4):174–183. doi: 10.1039/b516356k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Newgard C B, An J, Bain J R. et al. A branched-chain amino acid-related metabolic signature that differentiates obese and lean humans and contributes to insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 2009;9(4):311–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hadden D R, McLaughlin C. Normal and abnormal maternal metabolism during pregnancy. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009;14(2):66–71. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: About adult BMI. In: Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/adult_bmi/. Accessed 2015

- 10.Mei J V, Alexander J R, Adam B W, Hannon W H. Use of filter paper for the collection and analysis of human whole blood specimens. J Nutr. 2001;131(5):1631S–1636S. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.5.1631S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ryckman K K, Berberich S L, Shchelochkov O A, Cook D E, Murray J C. Clinical and environmental influences on metabolic biomarkers collected for newborn screening. Clin Biochem. 2013;46(1–2):133–138. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2012.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Metzger B E, Unger R H, Freinkel N. Carbohydrate metabolism in pregnancy. XIV. Relationships between circulating glucagon, insulin, glucose and amino acids in response to a “mixed meal” in late pregnancy. Metabolism. 1977;26(2):151–156. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(77)90050-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thompson D K, Sloane R, Bain J R. et al. Daily Variation of Serum Acylcarnitines and Amino Acids. Metabolomics. 2012;8(4):556–565. doi: 10.1007/s11306-011-0345-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Endo S, Maeda K, Suto M. et al. Differences in insulin sensitivity in pregnant women with overweight and gestational diabetes mellitus. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2006;22(6):343–349. doi: 10.1080/09513590600724836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nelson S M, Matthews P, Poston L. Maternal metabolism and obesity: modifiable determinants of pregnancy outcome. Hum Reprod Update. 2010;16(3):255–275. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmp050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vidakovic A J, Jaddoe V W, Gishti O. et al. Body mass index, gestational weight gain and fatty acid concentrations during pregnancy: the Generation R Study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2015;30(11):1175–1185. doi: 10.1007/s10654-015-0106-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tomedi L E, Chang C C, Newby P K. et al. Pre-pregnancy obesity and maternal nutritional biomarker status during pregnancy: a factor analysis. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16(8):1414–1418. doi: 10.1017/S1368980013000736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al M D, van Houwelingen A C, Badart-Smook A, Hasaart T H, Roumen F J, Hornstra G. The essential fatty acid status of mother and child in pregnancy-induced hypertension: a prospective longitudinal study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;172(5):1605–1614. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)90505-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al M D van Houwelingen A C Hornstra G Long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids, pregnancy, and pregnancy outcome Am J Clin Nutr 200071(1, Suppl)285S–291S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller A L. The methionine-homocysteine cycle and its effects on cognitive diseases. Altern Med Rev. 2003;8(1):7–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mascarenhas M, Habeebullah S, Sridhar M G. Revisiting the role of first trimester homocysteine as an index of maternal and fetal outcome. J Pregnancy. 2014;2014:123024. doi: 10.1155/2014/123024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Refsum H Nurk E Smith A D et al. The Hordaland Homocysteine Study: a community-based study of homocysteine, its determinants, and associations with disease J Nutr 2006136(6, Suppl)1731S–1740S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murphy M M, Scott J M, Arija V, Molloy A M, Fernandez-Ballart J D. Maternal homocysteine before conception and throughout pregnancy predicts fetal homocysteine and birth weight. Clin Chem. 2004;50(8):1406–1412. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2004.032904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fryer A A, Emes R D, Ismail K M. et al. Quantitative, high-resolution epigenetic profiling of CpG loci identifies associations with cord blood plasma homocysteine and birth weight in humans. Epigenetics. 2011;6(1):86–94. doi: 10.4161/epi.6.1.13392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.