Abstract

Neuroimaging-based single subject prediction of brain disorders has gained increasing attention in recent years. Using a variety of neuroimaging modalities such as structural, functional and diffusion MRI, along with machine learning techniques, hundreds of studies have been carried out for accurate classification of patients with heterogeneous mental and neurodegenerative disorders such as schizophrenia and Alzheimer's disease. More than 500 studies have been published during the past quarter century on single subject prediction focused on a multiple brain disorders. In the first part of this study, we provide a survey of more than 200 reports in this field with a focus on schizophrenia, mild cognitive impairment (MCI), Alzheimer's disease (AD), depressive disorders, autism spectrum disease (ASD) and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Detailed information about those studies such as sample size, type and number of extracted features and reported accuracy are summarized and discussed. To our knowledge, this is by far the most comprehensive review of neuroimaging-based single subject prediction of brain disorders. In the second part, we present our opinion on major pitfalls of those studies from a machine learning point of view. Common biases are discussed and suggestions are provided. Moreover, emerging trends such as decentralized data sharing, multimodal brain imaging, differential diagnosis, disease subtype classification and deep learning are also discussed. Based on this survey, there are extensive evidences showing the great potential of neuroimaging data for single subject prediction of various disorders. However, the main bottleneck of this exciting field is still the limited sample size, which could be potentially addressed by modern data sharing models such as the ones discussed in this paper. Emerging big data technologies and advanced data-intensive machine learning methodologies such as deep learning have coincided with an increasing need for accurate, robust and generalizable single subject prediction of brain disorders during an exciting time. In this report, we survey the past and offer some opinions regarding the road ahead.

Keywords: Neuroimaging, Machine Learning, Classification, Brain Disorders, Prediction

1. Introduction

Neuroimaging has opened up an exciting non-invasive window into the human brain over the past few decades. This interdisciplinary field has attracted scientists from areas such as medicine, engineering, mathematics, physics, statistics, computer science, and psychology (Epstein et al., 2001). Imaging modalities such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and magnetoencephalography (MEG) along with more traditional methods such as electroencephalography (EEG) have made it possible to noninvasively study various aspects of the human brain with unprecedented accuracy. MRI-related techniques such as structural MRI (sMRI), functional MRI (fMRI) and diffusion MRI (dMRI) have the benefit of providing localized spatial information about the brain structure and function as well as functional and structural connectivity. These techniques have provided new insight into the human brain and have brought hope to researchers trying to unravel the secrets of one of the most complex systems in the universe, the human brain.

Structural MRI has made it possible to visualize the brain at high spatial resolution (one cubic millimeter or less) (Liang and Lauterbur, 2000). SMRI high resolution images of the brain are ideal for studying various brain structures and also for detecting physical abnormalities, lesions and damages. DMRI is an imaging technique for visualization of anatomical connections between different brain regions (Le Bihan et al., 2001; Merboldt et al., 1985). Functional MRI measures brain activity by detecting changes in the blood oxygenation (DeYoe et al., 1994; Ogawa et al., 1990). FMRI makes it possible to study functional regions and networks of the brain as well as temporal associations among them.

Unfortunately, brain disorders are major health problems in US and the rest of the world that not only impair lives of millions of people but also impose huge financial burdens on societies (DiLuca and Olesen, 2014; Ernst and Hay, 1994; Rice, 1999). Moreover, there are no clinical tests to identify many brain disorders such as schizophrenia. One of the major hopes underlying the advanced neuroimaging tools mentioned above is to provide new understanding of brain disorders such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), Alzheimer's disease (AD), major depressive disorders, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Brain disorder research aims at understanding the impact of each disease on the brain's function and structure from the cellular to system level, as well as the pathogenesis of these complex disorders. As a result, thousands of studies have been published on different aspects of brain disorders to show aberrations of some features (structural or functional) in a patient group usually in comparison with a healthy cohort (Jack et al., 1997; Jafri et al., 2008; Lorenzetti et al., 2009; McAlonan et al., 2005). While these studies are valuable in terms of finding relevant disease biomarkers, they are not sufficient for direct clinical diagnostic/prognostic adoption. The main reason is that many of these findings are statistically significant at the group level, but the individual discrimination ability of the proposed biomarkers is not typically evaluated. Since classification provides information for each individual subject, it is considered a much harder task than reporting group differences.

In recent years, there has been a growing trend in designing neuroimaging-based prognostic/diagnostic tools. As a result, there have been a lot of efforts using neuroimaging tools to automatically discriminate patients with brain disorders from healthy control or from each other (Klöppel et al., 2012). Many of these studies have reported promising prediction performances with the claim that complex diseases can be diagnosed robustly, accurately and rapidly in a automatic fashion. However, until now, these tools have not been integrated into the clinical realm. We believe the main reason for this is that many of the studies of this nature, despite the promising results on a specific research dataset, are not designed to generalize to other datasets, specifically the clinical ones.

The purpose of this study is two-fold. First, we reviewed a large number of MRI-based brain disorder diagnostic/prognostic studies in schizophrenia, ASD, ADHD, depressive disorder, MCI and Alzheimer's disease. These studies are compared in a number of key aspects such as type of features, classifier and reported accuracies. Next, we formed our opinion on the issues associated with how machine learning is applied in neuroimaging and have suggested solutions that might address these pitfalls. Considering the immense potential of neuroimaging tools for clinical adoption, careful implementation and interpretation of machine learning in neuroimaging is crucial. Machine learning is a relatively new domain for many neuroimaging researchers coming from other fields and therefore pitfalls are unfortunately not rare. We attempt to identify and emphasize some common mistakes that result in these shortcomings and biases. At the end, we discuss emerging trends in neuroimaging such as data sharing, multimodal brain imaging and differential diagnosis.

1.1 Group Difference vs. Classification

As pointed out in the introduction, many brain disorder studies have shown abnormality in the average sense in one or more brain features in a patient cohort in comparison with a healthy group using statistical tests. The success of such methodology is usually measured by the means of p-values. On the other hand, the goal of single subject prediction is to automatically classify each subject into one of the groups in the study (e.g., healthy vs. patient). The success of classification studies is usually measured by accuracy.

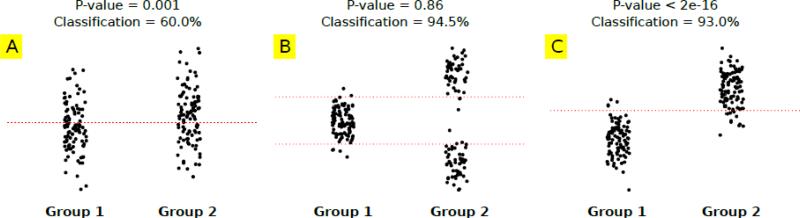

These two problems are very different in essence as they try to address varying research questions. In general, showing group differences is much easier compared to single subject prediction. To better illustrate the difference between these types of analysis, we show an example in Figure 1. Suppose there are two groups each with 100 samples (subjects) and we have measurements of one brain feature for each subject. Figure 1A shows a case where the mean of two groups is different as measured by a two-sample t-test. The difference is statistically significant (p-value=0.001). However, if one tries to classify subjects based on a threshold on this brain feature (the dotted red line placed between the mean of two groups), a weak classification rate of 60.0% will be achieved. The reason for this is the range of values for that specific feature is highly overlapping for the two groups. So, a highly significant group difference does not necessarily translate into a strong classification result. But the opposite is also true, as high classification based on a feature doesn't necessarily mean that group-level mean differences exist. Figure 1B shows a case where the two-sample t-test on the two groups is not significant (p-value= 0.86) but the classification based on two thresholds (red dotted lines placed between each mode of group 2 and mean of group 1) is very strong (94.5%). In this case, the abnormality is bidirectional, which does not cause significant mean differences but makes it possible to separate the groups with two thresholds (dotted lines). Interestingly, bidirectional abnormalities are observed in neuroimaging studies (Mohammad R. Arbabshirani and Calhoun, 2011; Calhoun et al., 2006b). Figure 1C shows a case where strong group differences and successful classification go hand in hand. The abnormality is one-directional and the mean difference is very significant (p-value<2e-16). The mean of two groups is so far apart that the values of most of the samples of the two groups do not overlap. Therefore, a strong classification rate of 93.5% is achieved (based on one threshold).

Figure 1.

Comparison of group difference analysis and classification in three different scenarios using toy data. Group difference is analyzed by two-sample t-tests and classification is performed by simple thresholding (red dotted lines). Each group/class has 100 samples. A: Significant group difference (p-value<0.001) but poor classification (60.0%). B: Insignificant group difference (p-value=0.865) but high classification accuracy (94.5%). C: Significant group difference (p-value<2e-16) and high classification accuracy (93.0%). Significant group difference doesn't necessarily cause high classification and vice versa.

The main purpose of example in Figure 1 is to show that group level analysis and classification are two different methods for different problems. We will return to this example later for criticism of selecting features based on p-value.

2. Survey of MRI-based Single-Subject Prediction of Brain Disorders

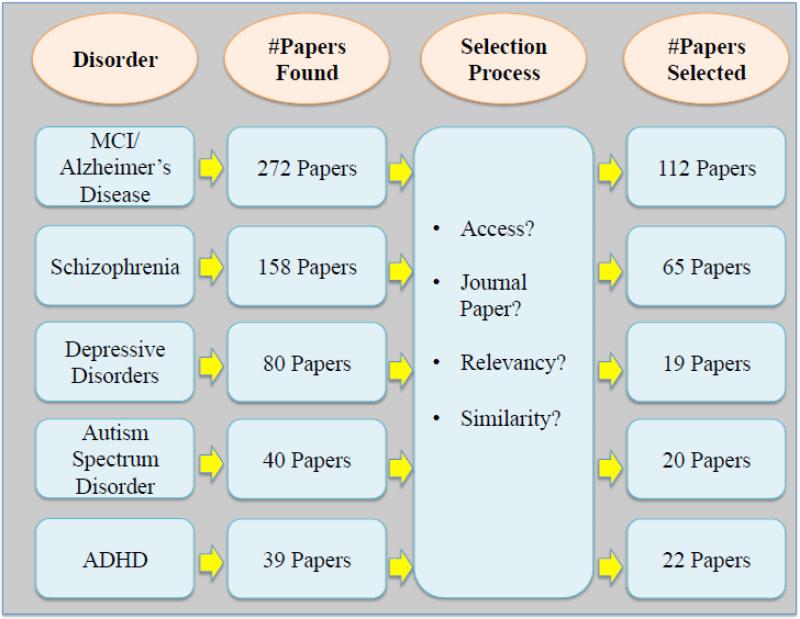

Based on a search on Pubmed from 1990 to 20151, more than 500 papers on MRI-based single subject prediction of brain disorders were found. Figure 2 summarizes the paper selection procedure for this study. More than 200 papers were eventually selected for this survey (112 AD/MCI, 63 schizophrenia, 19 depressive disorders, 20 ASD and 22 ADHD papers).

Figure 2.

The literature review procedure, the inclusion criteria and the number of surveyed studies for each modality.

We limited our search to journal papers in English published up to December 2015. In a few instances, the full paper was not found and therefore those studies were excluded from this survey. Also, in cases of very similar papers from the same authors, only one was selected. Key aspects of each study such as modality, machine learning method, sample size and type features were investigated. A list of all abbreviations used in the tables and the manuscript itself is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Glossary

| Abbreviation | Full Term |

|---|---|

| AAL | Automated anatomical Labeling |

| ABIDE | Autism brain imaging data exchange |

| AD | Alzheimer's disease |

| ADAS | Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale |

| ADHD | Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder |

| ADHD-C | ADHD Combined |

| ADHD-HI | Hyperactive/impulsive ADHD |

| ADHD-IA | Inattentive ADHD |

| ADNI | Alzheimer's disease neuroimaging initiative |

| ADOS | Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule |

| AG | Angular Gyrus |

| ALFF | Amplitude of low frequency fluctuations |

| aMCI | amnestic MCI |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| AOD | Auditory Oddball |

| ASD | Autism Spectrum Disease |

| AUC | Area under curve |

| AX-CPT | AX version of continuous performance task |

| BOLD | Blood-Oxygen Level Dependent |

| BP | Bipolar Disorder |

| CFT | Complex Figure Test |

| cMCI | MCI converter |

| CN | Cognitively normal |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal fluid |

| DA | Axial Diffusion |

| DAT | Dementia of the Alzheimer's Type |

| DLPFC | Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex |

| DMN | Default-Mode network |

| dMRI | Diffusion Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| DR | Radial Diffusion |

| DRS | Dementia Rating Scale |

| EC | Elderly Controls |

| EEG | Electroencephalography |

| ELM | Extreme Learning Machines |

| EMCI | Early MCI |

| ERC | Entorhinal Cortex |

| FA | Fractional anisotropy |

| FALLF | Fractional Amplitude of low frequency fluctuations |

| FBIRN | Functional Biomedical Informatics Research Network |

| FC | Functional Connectivity |

| FDG | Fluorodeoxyglucose |

| FDG-PET | Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography |

| FFT | Fast Fourier Transform |

| fMRI | Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| FNC | Functional Network Connectivity |

| FTD | Frontotemporal Dementia |

| GLM | General Linear Modeling |

| GM | Gray matter |

| GMD | Gray Matter Density |

| HC | Healthy controls |

| ICA | Independent Component Analyses |

| ITG | Inferior Temporal Gyrus |

| jICA | Joint Independent Component Analysis |

| LBD | Lewy body dementia |

| LDA | Linear Discriminant Analysis |

| LDDMM | Large Deformation Diffeomorphic Metric Mapping |

| LLD | Late-life Depression |

| LLE | Locally linear embedding |

| LMCI | Late MCI |

| MA | Mean anisotropy |

| mCCA | Multi-set Canonical Correlation Analysis |

| MCI | Mild Cognitive Impairement |

| MCIC | Multi-site Clinical Imaging Consortium |

| MD | Mean Diffusitivity |

| md-aMCI | Multiple Domains MCI |

| MDD | Major Depressive Disorder |

| MEG | Magnetoencephalography |

| MLSP | Machine Learning for Signal Processing |

| mMLDA | Modified Maximum Uncertainty Linear Discriminant Analysis |

| MMSE | Mini Mental State Examination |

| MPFC | Medial Prefrontal Cortex |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| MRMR | Minimum Redundancy Maximum Relevancy |

| MRS | Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy |

| MTL | Medial Temporal Lobe |

| MTR | Magnetization Transfer Ratio |

| MVPA | Multi voxel pattern analysis |

| N/A | No Answer |

| ncMCI | MCI non-converter |

| NDD | Non-refractory Depressive Disorder |

| NMF | Non-negative Matrix Factorization |

| OCD | Obsessive Compulsive Disorder |

| ODVBA | Optimally-Discriminative Voxel-Based Analysis |

| orPLS | Ordinary Partial Least Square |

| PANSS | Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| PCC | Posterior Cingulate Cortex |

| Probability Distribution Functuion | |

| PET | Positron Emission Tomography |

| pMCI | Progressive MCI |

| PPI | Psychophysiological Interaction |

| QDA | Quadratic Discriminant Analysis |

| RAVENS | Regional analysis of brain volumes in normalized space |

| RBF | Radial basis function |

| RDD | Refractory Depressive Disorder |

| ReHo | Regional Homogeneity |

| RMD | Remitted MDD |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| ROI | Region of interest |

| rsfMRI | Resting-state fMRI |

| RSN | Resting-state Networks |

| RVM | Relevance Vector Machine |

| RVoxM | Relevance Voxel Machine |

| RVR | Relevance Vector Regression |

| sACC | Subgenual Anterior Cingulate Cortex |

| SBM | Surface based morphometry |

| sd-aMCI | Single Domain amnestic MCI |

| sd-fMCI | Single Domain frontal MCI |

| SIFT | Scale-invariant Feature Transform |

| sMCI | Stable MCI |

| sMRI | Structural Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| SN | Salience Network |

| SNP | Single Nucleotide Polymorphism |

| SSD | Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders |

| StD | Late-Life Subthreshold Depression |

| SUVr | Standard Uptake Value Ratio |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| SVM-FoBa | Support Vector Machine with a Forward-Backward search strategy |

| SVM-RFE | Support vector machine with recursive feature elimination |

| SZ | Schizophrenia |

| SZA | Schizoaffective |

| TD | Typically Developing |

| TDC | Typically Developing Children |

| uMCI | Unknown MCI |

| VaD | Vascular Dementia |

| VBM | Voxel-based Morphometry |

| VMHC | Voxel-mirrored Homotopic Correlations |

| VOI | Volume of Interest |

| WM | White matter |

| WMD | White Matter Density |

| WMT | Working Memory Task |

2.1 Mild Cognitive Impairment/Alzheimer's Disease

MCI entails cognitive decline more than what is expected for an individual's age and education level, but not to the extent that it interferes notably with activities of daily life (Albert et al., 2011). Unfortunately, more than 50% of the MCI patients progress to dementia within 5 years (Gauthier et al., 2006). So, it is considered a prodromal phase to dementia especially the AD type (Gauthier et al., 2006). The heterogeneous etiology of MCI includes degenerative diseases (AD, fronto-temporal lobe degeneration, dementia with Lewy bodies) as well as vascular and psychiatric disorders (Petersen and Negash, 2008). AD is the most common neurodegenerative disorder, which is increasingly prevalent among adults aged 65 years and older. AD is characterized by the progressive impairment of neurons and their connections, which result in decline and loss of cognitive functions. In 2007, it was estimated that more than 26 million people suffer from AD worldwide (Brookmeyer et al., 2007). In 2001 it was predicted that AD will triple in prevalence by 2050 (Hebert et al., 2001). The detection of AD is based on clinical examinations and an evaluation of the patient's perception and behavior. Considering the prevalence and severity of MCI/AD, the largest number of neuroimaging-based, automatic prediction/classification publications has been devoted to these conditions. Table 2 summarizes the 112 studies that we reviewed in this survey.

Table 2.

Summary of 112 MRI-based AD/MCI classification studies. Overall classification accuracy of sMCI (cMCI) from pMCI (ncMCI) is indicated by MCI-CONV if applicable.

| Modality | Disorder | Features | # Features | Classifier | Number of Subjects | Overall Accuracy | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dMRI | AD | FA | 1210 | SVM | HC=25, AD=20, Total=45 |

100% | (Graña et al., 2011) |

| dMRI and sMRI | AD | FA and MD from dMRI and GMD and WMD from sMRI |

26,000 FA, 128,000 MD, 41,000 WMD and 181,000 GMD |

SVM | HC=143, AD=137, Total=280 |

63.6-91.1% | (Dyrba et al., 2013) |

| rsfMRI | AD | Averaged voxel intensities of selected resting-state networks |

4 | Multivariate ROC | HC=16, AD=15, Total=31 |

100% | (Wu et al., 2013) |

| rsfMRI | AD | Graph measures based on FC analysis among ROIs |

454 | SVM | HC=20, AD=20, Total=40 |

100% | (Khazaee et al., 2015) |

| sMRI | AD | Eigen brains of key slices | 10 | SVM | NC=98, AD=28, Total=126 |

92.3% | (Zhang et al., 2015) |

| sMRI | AD | ODVBA of RAVENs maps | N/A | SVM | HC=50, AD=50, Total=100 |

90% | (Zhang and Davatzikos, 2011) |

| sMRI | AD | Hippocampus shape measures using LDDMM and PCA |

20 Principal componen ts (3-4 selected by the classifier) |

Logistic Regression | HC=26, DAT=18, Total=44 |

81.1-84.6% | (Wang et al., 2007) |

| sMRI | AD | GM, WM, and CSF tissue densities along with age, gender and genotype |

237-240 | SVM | HC=190, AD=190, Total=380 |

85.6-89.3% | (Vemuri et al., 2008) |

| sMRI | AD | Cortical thickness measures along mesh vertices |

82000 mesh vertices |

RVoxM | HC= 150, Ad=150, Total=300 |

93.0% (AUC) |

(Sabuncu and Van Leemput, 2012) |

| sMRI | AD | Whole brain and hippocampus VBM measures |

N/A | SVM | EC=31, AD=31, Total=62 |

74-79% | (Polat et al., 2012) |

| sMRI | AD | Volumetric measures | 45 | SVM | HC=20, AD=14, Total=34 |

88.2% | (Oliveira et al., 2010) |

| sMRI | AD | Hippocampus morphometric measures | 9 | LDA | HC=57, AD=38, Semantic dementia=6, Total=101 |

77% | (Miller et al., 2009) |

| sMRI | AD | GM Maps | 10-45 | SVM, ELM, Self- adaptive Resource Allocation Network |

HC=30, AD=30, Total=60 |

97.1-99.7% | (Mahanand et al., 2012) |

| sMRI | AD | GM distribution of ROIs | 90 | SVM | EC=22, AD=16, Total=38 |

94.5% | (Magnin et al., 2009) |

| sMRI | AD | Surface-based measures of hippocampus | N/A | SVM | HC=20, AD=19, Total=39 |

84.6-94.9% | (Li et al., 2007) |

| sMRI | AD | Cortical thickness | N/A | LDA, QDA and Logistic regression |

HC=17, AD=19, Total=36 |

90-100% | (Lerch et al., 2008) |

| sMRI | AD | Cortical thickness data and hippocampus shape |

N/A | LDA | NC=84, AD=33, Total=117 |

87.5% | (Lee et al., 2014) |

| sMRI | AD | GM Probability Maps | Variable | Linear program boosting of voxel- wise weak classifiers with spatial constraints |

Total=183 | 82.0% (AUC) |

(Hinrichs et al., 2009) |

| sMRI | AD | WM and GM voxels selected by SVM-RFE | Variable | SVM | HC=185, AD=185, Total=370 |

94.3-95.1% | (Hidalgo-Muñoz et al., 2014) |

| sMRI | AD | Volumes of hippocampus–amygdala formation |

1 | Thresholding | HC=28, AD=27, Total=55 |

89-96% (Sensitivity) |

(Hampel et al., 2002) |

| sMRI | AD | Linear measurements of several structures | 12 | Linear Discriminant Analysis |

HC=31, AD=46, Total=77 |

81-87% (Sensitivity) |

(Frisoni et al., 1996) |

| sMRI | AD | Texture Features | 260 | Linear Discriminant Function |

HC=40, AD=24, Total=66 |

91% | (Freeborough and Fox, 1998) |

| sMRI | AD | Percentage of brain volume changes | 3 | SVM | NC=30, AD=30, Total=60 |

91.7% | (Farzan et al., 2015) |

| sMRI | AD | GM, WM and CSF volumes and size of hippocampus |

5 | SVM, MLP, and J48 decision tree |

NC=48, AD=37, Total=85 |

93.7% | (Farhan et al., 2014) |

| sMRI | AD | Brain volume, temporal lobe matter and CSF volume |

4 | Discriminant Analysis |

HC=29, DAT=31, Total=60 |

100% | (DeCarli et al., 1995) |

| sMRI | AD | Several voxel-based and cortical thickness- based schemes |

Variable | Regularized SVM | CN=162, AD=137, Total= 299 |

83-91% | (Cuingnet et al., 2013) |

| sMRI | AD | Atrophic patterns of hippocampus and entorhinal cortex |

N/A | QDA | HC=50, AD=50, Total=100 |

93% | (Coupé et al., 2012) |

| sMRI | AD | SIFT Features | 133 | Ensemble of SVMs | HC1=66, AD1=20, HC2=98, AD2=28, Total=212 |

70-87% | (Chen et al., 2014) |

| sMRI | AD | PDF of VOI based on VBM | 100 | SVM | HC=130, AD-130, Total- 260 |

86% | (Beheshti and Demirel, 2015) |

| sMRI | AD | Generative-Discriminative Basis vectors based on RAVEN maps |

30-50 | Logistic Model Trees |

HC=63, AD=54, Total=117 |

87-89% | (Batmanghelich et al., 2012) |

| sMRI | AD | Cortical thickness and volumetric measures | N/A | SVM | HC=25, AD=29, Total=54 |

90.9% (AUC) | (Arimura et al., 2008) |

| sMRI | AD | GM maps based on VBM | 384,065 | SVM | HC=137, AD=108, MCI=203, Total=448 |

63.7-80.3% | (Adaszewski et al., 2013) |

| sMRI | AD | Gray Matter Probability Maps | 2E6 | SVM | HC=226, AD=91, Total=417 |

87% | (Abdulkadir et al., 2011) |

| sMRI and dMRI | AD | FA and GM volumes | 142 | SVM | NC=15, AD=21, Total=36 |

94.3% | (Li et al., 2014b) |

| sMRI and PET | AD | Volumes of interest | 12 | SVM | HC1=28, AD1=28, HC2=13, AD2=21, Total=90 |

86-100% | (Dukart et al., 2013) |

|

sMRI and rsfMRI |

AD | GM Volume from sMRI and ALFF, RcHo and FC from rsfMRI |

Variable | Maximum uncertainty LDA and second level |

HC=22, AD=16, Total=38 |

89.5% | (Z. Dai et al., 2012) |

|

sMRI, rsfMRI and dMRI |

AD | GM volume from sMRI, fiber tract integrity from dMRI and graph-theoretical measures form fMRI |

N/A | SVM | HC=25, AD=28, Total=53 |

74-85% (AUC) |

(Dyrba et al., 2015) |

|

fMRI (confrontation naming task) |

AD (Low and high risk) |

Fractional signal changes ROI | 50 | LDA+orPLS | Low AD Risk HC=11, High AD Risk HC= 13, Total=24 |

83.3% | (Andersen et al., 2012) |

| dMRI | AD/BP | FA Maps | 1500- 14000 |

SVM | HC=25, BP=12, AD=20 | 100% | (Bergouignan et al., 2011) |

| rsfMRI | AD/FTD | ROI-based difference between DMN and SN map |

22 | LDA | HC=12, AD=12, FTD=12, Total=36 |

92% | (Zhou et al., 2010) |

| sMRI | AD/FTD | GM Maps | N/A | SVM | HC=91, AD=85, FTD=19, Total=195 |

87-96% | (Klöppel et al., 2008) |

| sMRI | AD/FTD | GM volume an thickness and complexity estimates |

N/A | LDA | CN=23 AD=24, FTD=19, Total=66 |

81-96% | (Young et al., 2009) |

| sMRI | AD/FTD | Morphometric measures of selected ROIs | 2 | Discriminant Analysis |

EC=12, AD=17, FTD=16, Total=45 |

91% | (Kaufer et al., 1997) |

| dMRI | AD/MCI | FA and MD Values | 12-1080 | SVM | EC=50, AD=37, MCI=113, Total=200 |

68.3-84.9% | (Nir et al., 2015) |

| rsfMRI | AD/MCI | FC among selected AAL regions | 3403 | Bayesian Gaussian process logistic regression |

HC=39,aMCI=50, AD=27, Total=116 |

75-90% | (Challis et al., 2015) |

| sMRI | AD/MCI | 3D hippocampal shape morphology | N/A | SVM | HC=88, MCI=103, AD=71, Total=262 |

MCI-CONV: 80% |

(Costafreda et al., 2011a) |

| sMRI | AD/MCI | GM, WM and CSF volumetric measures and ventricle shape |

18 | Particle swarm optimization SVM |

HC=17, AD=17, MCI=18, Total=52 |

88.9-94.1% | (Yang et al., 2013) |

| sMRI | AD/MCI | Coefficient of ICA on normalized brain images |

N/A | SVM | HC1=316, AD1=98, Total1=416, HC2=200, AD2=200, MCI=400, Total2=800, |

67.5-99% | (Yang et al., 2011) |

| sMRI | AD/MCI | Hippocampal volume, tensor-based morphometry, cortical thickness and Manifold-based learning features |

112-114 | LDA and SVM | HC=231, AD=198, sMCI=238, pMCI=167, Total=834 |

84.0-89.0% MCI- CONV:68.0 % |

(Wolz et al., 2011) |

| sMRI | AD/MCI | ROI-based and correlative features based on cortical and cerebral thickness and WM volumes |

N/A | Multi-kernel SVM | NC=200, AD=198, ncMCI=111, cMCI=89, Total=598 |

79.2-97.4% MCI- CONV:75.1 % |

(Wee et al., 2013) |

| sMRI | AD/MCI | Intensity patches of selected ROIs around hippocampus |

130-150 Patches |

SVM (in multiple instance-Graph Framework) |

CN=231, AD=198, ncMCI=238, cMCI=167, Total=834 |

82.9-89% -MCI- CONV:70% |

(Tong et al., 2014) |

| sMRI | AD/MCI | Diffeomorphometry patterns of subcortical and ventricular structures |

14 | LDA | HC=210, AD=175, cMCI=135, ncMCI=87, Total=607 |

MCI- CONV:77.0 % |

(Tang et al., 2015) |

| sMRI | AD/MCI | Hippocampus, amygdala, and ventricle shape measures |

N/A | LDA | HC=210, AD=175, MCI=369, Total=754 |

86% | (Tang et al., 2014) |

| sMRI | AD/MCI | Whole brain GM and WM maps | 34-127 | SVM | HC=162, AD=137, ncMCI=134, cMCI=76, Total=509 |

72-76%, MCI- CONV:66.0 % |

(Salvatore et al., 2015b) |

| sMRI | AD/MCI | GM Maps | 6000 | SVM | HC=189, AD=144, ncMCI=166, cMCI=136, Total=635 |

80.0% - MCI- CONV:70.7 % |

(Retico et al., 2015) |

| sMRI | AD/MCI | Hippocampal surface deformation measures | 19 | LDA | HC=26, DAT=18, DAT- Converters=9, Total=53 |

77.0-87.0% | (Qiu et al., 2008) |

| sMRI | AD/MCI | GM and WM maps | Variable | SVM, Bayes statistic and voting feature intervals |

HC=18, AD=32, MCI=24, Total=74 |

92%-MCI- CONV:75.0 % |

(Plant et al., 2010) |

| sMRI | AD/MCI | Volumes of the hippocampus and ERC | 2-4 | Discriminant Function Analysis |

HC=59, AD=48, MCI=65, Total=172 |

65.9-90.7% | (Pennanen et al., 2004) |

| sMRI | AD/MCI | GM Density of ROIs | 37 | SVM | ncMCI=38, cMCI=39, Total=77 |

77.7% (MCI Conversion) |

(Ota et al., 2014) |

| sMRI | AD/MCI | Hippocampal volumetric measures | 5 | LDA | HC=53, AD=18, MCI=20, Total=91 |

73.7-77.5% | (Mueller et al., 2010) |

| sMRI | AD/MCI | GM density values and cognitive measures | 309 | Low density separation semi- supervised classifier |

NC=231, AD=200, sMCI=100, pMCI=164, uMCI=130, Total=825 |

MCI-CONV: 76.6-90.0% (AUC) |

(Moradi et al., 2015) |

| sMRI | AD/MCI | Data-driven ROI GM from different templates |

1500 from each template |

SVM | NC=128, AD=97, sMCI=117, pMCI=117, Total=459 |

91.6%, MCI- CONV: 72.4% |

(Min et al., 2014) |

| sMRI | AD/MCI | Longitudinal volumetric MR imaging measures |

N/A | QDA | HC=203 AD=164, MCI=317, Total=684 |

85% | (McEvoy et al., 2011) |

| sMRI | AD/MCI | Volumetric and cortical thickness measures | N/A | LDA | HC=139, AD=84, MCI=175, Total=398 |

89-92% | (McEvoy et al., 2009) |

| sMRI | AD/MCI | GM maps | N/A | Ensemble of SVMs | NC=229, AD=198, MCI=225, Total=652 |

85.3-92.0% | (M. Liu et al., 2014) |

| sMRI | AD/MCI | GM maps registered to multiple templates | 1500 for each template |

Ensemble of SVMs | NC=128, AD=97, sMCI=117, pMCI=117, Total=459 |

93.8% MCI- CONV:80.9 % |

(Liu et al., 2015) |

| sMRI | AD/MCI | Volume and cortical thickness values of ROIs |

162 Original features reduced by LLE |

Logistic regression, SVM and LDA |

CN=137, sMCI=93, cMCI=97, AD=86, Total=413 |

51-89% MCI-CONV: 68% |

(Liu et al., 2013) |

| sMRI | AD/MCI | Surface connectivity and center of mass markers |

N/A | LDA | NC=170, AD=114, MCI=240, Total=524 |

76.6-87.7% (AUC) |

(Lillemark et al., 2014) |

| sMRI | AD/MCI | Proposed local binary pattern features | N/A | SVM | NC=142, AD=80, MCI=141, Total=363 |

61.5-82.8% | (Li et al., 2014a) |

| sMRI | AD/MCI | Cortical thickness measures, cortex thinning dynamics and network features based on longitudinal thickness changes of different ROIs |

262 | SVM | NC=40, sMCI=36, pMCI=39, AD=37, Total=152 |

81.7-96.1% MCI- CONV:80.3 % |

(Li et al., 2012) |

| sMRI | AD/MCI | Hurst's exponents at different scales | N/A | SVM | HC=11, AD=11, MCI=11, Total=33 |

97.1-97.5% | (Lahmiri and Boukadoum, 2014) |

| sMRI | AD/MCI | Volumetric Measures | 120 (115 brain features) |

LDA | CN=125, AD=55, HMCI=114, LMCI=91, Total=385 |

90.8-94.5% | (Goryawala et al., 2015) |

| sMRI | AD/MCI | Spherical harmonics of hippocampi | 2646 | SVM | HC=25, AD=23, aMCI=23, Total=71 |

83-94% | (Gerardin et al., 2009) |

| sMRI | AD/MCI | Three schemes: voxel-based features, cortical thickness features and hippocampus-based features |

Variable | SVM | CN=162, AD=137,cMCI=76, ncMCI=134, Total=509 |

81-95% (for AD vs CN) |

(Cuingnet et al., 2011) |

| sMRI | AD/MCI | Volume, thickness and surface area of selected ROIs |

7 MRI, 2 CSF and 14 neuropsyc hological features |

SVM | HC=111, cMCI=56, ncMCI=111, AD=96, Total=350 |

MCI-CONV: 67.1% |

(Cui et al., 2011) |

| sMRI | AD/MCI | Hippocampus and parahippocampal gyrus GM maps |

11,031 | SVM | HC=188, MCI=260, AD=131 |

70-85% MCI-CONV: 65% |

(Chu et al., 2012) |

| sMRI | AD/MCI | Intensity and texture of selected VOIs in MTL |

>100,000 | Ensemble of SVMs | HC=189, ncMCI=166, cMCI=136, AD=144 |

65-94% MCI- CONV:74.0 % (AUC) |

(Chincarini et al., 2011) |

| sMRI | AD/MCI | GM Map | 50,000- 750,000 |

SVM, Regularized logistic Regression, Linear Regression Classifier |

HC=205, MCI=351, AD= 171, Total= 727 |

80-90% | (Casanova et al., 2012) |

| sMRI | AD/MCI | Volumetric measures of amygdala, hippocampus, and parahippocampal gyrus |

N/A | Discriminant function analysis |

NEC=20, MCI=21, AD=39, Total=60 |

80.5-88.1% | (Bottino et al., 2002) |

| sMRI | AD/MCI | Hippocampal volume and CSF Aβ, t-tau and p-tau levels, and ApoE4 stratification |

N/A | SVM | NC=111, AD=95, MCI=182 |

64-78% | (Apostolova et al., 2014) |

| sMRI | AD/MCI | Cortical thickness and volumetric measures | 57 | SVM | HC=110, AD=116 MCI=119, Total=345 |

88.1% | (Aguilar et al., 2013) |

| sMRI and dMRI | AD/MCI | Network topology, tractography connectivity and flow-based measures |

N/A | SVM | NC=50, AD=38, EMCI=74, LMCI=38, Total=200 |

59.2-78.2% | (Prasad et al., 2015) |

| sMRI and dMRI | AD/MCI | Disease-specific spatial filters | N/A | LDA | NC=22, AD=19, MCI=22, Total=63 |

9.3.0% (AUC) MCI Conversion |

(Oishi et al., 2011) |

| sMRI and dMRI | AD/MCI | Cortical thickness, subcortical volume and white matter integrity |

2-5 | SVM | SMI=27, AD=27, MCI=138 Total=72 |

70.5-96.3% | (Jung et al., 2015) |

| sMRI and PET | AD/MCI | Volumes of GM tissue of seleeted ROIs | 93 | Domain Transfer SVM |

NC=52, AD=51, cMCI=43, ncMCI=56, Total=202 |

MCI-CONV: 79.4% |

(B. Cheng et al., 2015) |

| sMRI and PET | AD/MCI | Functional and structural connectivity measures using sparse inverse covariance estimation |

84 | SVM | HC=68, AD=70, MCI=111, Total=249 |

84-92% | (Ortiz et al., 2015) |

| sMRI and PET | AD/MCI | GM volume of ROIs from sMRI and average intensity of ROIs from PET |

186 (original number of features) |

Multi-kernel SVM | NC=52, AD=51, MCI=99, Total=202 |

78.8-94.8% | (F. Liu et al., 2014) |

| sMRI, FDG-PET | AD/MCI | ROI-based GM, volumes from sMRI and average intensity from PET |

186 | Multi-kernel SVM | NC=52, AD=51, ncMCI=56, cMCI=43, Total=202 |

80.3-95.9%, MCI- CONV:69.8 % |

(Zu et al., 2015) |

|

sMRI, FDG- PET |

AD/MCI | Cortical and volumetric measures and surface based FDG uptakes |

24 | Partial least square LDA |

NC=85, AD=71, MCI=163, Total=319 |

76.5-90.1% | (Yun et al., 2015) |

|

sMRI, FDG- PET |

AD/MCI | GM and WM maps from sMRI and FDG- PET images |

Variable | Multi Kernel Learning |

HC=66, AD=48, MCI=119, Total=233 |

87.6% | (Hinrichs et al., 2011) |

|

sMRI, FDG- PET and Florbetapir PET |

AD/MCI | Mean volume of GM, SUVr value of FDG- PFT and SUVr value of florbetapir PET for selected ROIs |

90 per modalitiy |

Weighted multi- modality sparse representation- based classification |

NC=117, AD=113, sMCI=83, pMCT=27, Total=340 |

74.5-94.8%, MCI- CONV:77.8 % |

(Xu et al., 2015) |

|

sMRI, FDG- PET, and CSF |

AD/MCI | ROI-based GM, WM and CSF volumes from sMRI and average intensity from PET |

189 | SVM | HC=52, AD=51, ncMCI=56, cMCI=43, Total=202 |

76.4-93.2%, MCI- CONV=81.2 % |

(Zhang et al., 2011) |

|

sMRI, FDG- PET, and CSF data |

AD/MCI | Volume of GM from sMRI and average intensity from PET of selected ROIs along with CSF measures |

189 | Graph-guided multi-task learning |

NC=52, AD=50, MCI=97, Total=199 |

80.0-92.6% | (Yu et al., 2015) |

|

sMRI, FDG- PET, CSF, and APOE genotype |

AD/MCI | ROI-based GMD maps, mean activity from PET |

20 ROIs | Gaussian Process Classifier |

HC=73, AD=63, ncMCI=96, cMCI=47, Total=279 |

MCI- CONV:74.1 % |

(Young et al., 2013) |

| sMRI, PET | AD/MCI | Volume of GM from sMRI and average intensity from PET of selected ROIs |

186 | Multi-task Linear Programming Discriminant |

sMCI=226, pMCI=167, Total=393 |

MCI-CONV: 67.2% |

(Yu et al., 2014) |

| sMRI, PET | AD/MCI | GM density relative cerebral metabolic rate for glucose of ROIs |

168-172 | SVM | ncMCI=40, cMCI=40, Total=80 |

MCI-CONV: 74.8-75.0 % (AUC) |

(Ota et al., 2015) |

|

sMRI, PET, CSF and SNP |

AD/MCI | GM volume and average intensity of ROIs along with CSF and SNP features |

93(sMRI, 93(PET), 3 (CSF) and 5677 (SNP) |

SVM | HC=47, AD=49, MCI=93, Total=189 |

71.0-94.8% | (Zhang et al., 2014) |

| sMRI | AD/MCI/Diment ia |

GM and WM maps | N/A | SVM | HC=604, AD=483, FTD=51, LBD=27, ncMCI=290, cMCI=128, Total=1583 |

73-97% (AUC) MCI- CONV:73.0 % (AUC) |

(Klöppel et al., 2015) |

| dMRI, sMRI | AD/VaD | Transcallosal prefrontal FA and Fazckas score |

4 | LDA | HC=22, AD=16, VaD=13, Total=51 |

87.5% | (Zarci et al., 2009) |

| sMRI | Dementia | Hippocampal head and body volumetric measures |

4 | LDA | HC=17, Questionable Deminetia=12, Mild Dimential=10, Total=39 |

76.9% | (Wolf et al., 2001) |

| dMRI | MCI | Clustering coefficient of WM connectivity maps based on fiber count, FA, MD and principal diffusivities |

3 (Most selected ROIs) |

SVM | HC=17, MCI=10, Total=27 |

88.9% | (Wee et al., 2011) |

| dMRI | MCI | FA, DA, DR and MD | 500 | SVM | EC=40, MCI=33, Total=73 |

93.0% | (O'Dwyer et al., 2012) |

| dMRI | MCI | FA and the volume of fiber pathways from selected region |

100-4500 | SVM | NC=45, MCI=39, Total=84 |

100% | (Lee et al., 2013) |

| dMRI | MCI | FA maps | 1000 | SVM | sd-aMCI=18, sd- fMCI=13, ad-aMCI=35, Total=66 |

97% | (Haller et al., 2013) |

| dMRI | MCI | FA, longitudinal, radial, and mean diffusivity features |

N/A | SVM | HC=35, MCI=67, Total=102 |

91.4-97.5% | (Haller et al., 2010) |

| rsfMRI | MCI | local connectivity and global topological properties |

450 | Multiple Kernel Learning |

HC=25, MCI=12, Total=37 |

91.9% | (Jie et al., 2014) |

| rsfMRI | MCI | N/A | 465 | N/A | HC=21, MCI=29, Total=60 |

95.6% | (Beltrachini et al., 2015) |

| sMRI | MCI | Graph properties based on inter-regional co variation of cortical thickness |

Variable | Multiple Kernel Learning |

NC=42,sd-aMCI=38, md- aMCI=32, Total=112 |

56.0-62.0% | (Raamana et al., 2014) |

| sMRI | MCI | Volume, mean T1, MTR and T2* for selected ROIs |

7 ROIs | SVM | HC=77, MCI=42, Total=119 |

75% | (Granziera et al., 2015) |

| sMRI and dMRI | MCI | Subcortical volumetric measures and FA values |

68 | SVM | HC=204, aMCI=79, Total=283 |

71.1% | (Cui et al., 2012) |

|

sMRI, FDG- PET, CSF and Genetics |

MCI | ROI-based volumetric measures from sMRI, voxel-wise intensity measures from PET along with CSF and genetic features |

>1E5 | Random Forest | NC=35, AD=37, sMCI=41, pMCI=34, Total=147 |

74.6-89.0%, MCI- CONV:58.0 % |

(Gray et al., 2013) |

| sMRI, PET | MCI | ROI-based GM, WM and CSF volumes from sMRI and average intensity from PET |

93 ROIs | Multiple Kernel Learning |

ncMCI=50, cMCI=38, Total=88 |

78.4% | (Zhang and Shen, 2012b) |

2.2 Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is among the most prevalent mental disorders and affects about one percent of the population worldwide (Bhugra, 2005). This devastating, chronic heterogeneous disease is usually characterized by disintegration in perception of reality, cognitive problems, and a chronic course with lasting impairment (Heinrichs and Zakzanis, 1998). Considering the absence of standard clinical test for schizophrenia, there is a growing interest in automatic diagnosis of schizophrenia based on neuroimaging features. We surveyed 65 papers, which are tabulated in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of 65 MRI-based schizophrenia classification studies.

| Modality | Disorder | Features | # Features | Classifier | Number of Subjects | Overall Accuracy | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dMRI | Schizophrenia | Discriminant PCA of FA Maps | 60 | Fisher's Linear Discriminant |

HC=45, SZ=45 Total=90 |

80% | (Caprihan et al., 2008) |

| dMRI | Schizophrenia | FA Maps | 13 | LDA | HC=24, SZ=34 Total=58 |

75% | (Caan et al., 2006) |

| dMRI | Schizophrenia | Voxels of FA and MA maps reduced by PCA |

11-13 | LDA | HC=50, SZ=50 Total=100 |

96% | (Ardekani et al., 2011) |

|

fMRI (Sensorimotor, AOD, Working Memory tasks) |

Schizophrenia | Mean activation of the largest activation cluster |

1 | Majority vote of 3 decision stumps |

HC=15, SZ=13 Total=28 |

96% | (Honorio et al., 2012) |

|

fMRI (AOD/Sternberg /Sensorimotor tasks) |

Schizophrenia | ICA Spatial Maps | 10:14 | Projection Pursuit | HC=91, SZ=57 Total=138 |

80-90% | (Demirci et al., 2008a) |

|

fMRI (AX-CPT task) |

Schizophrenia (first-episode) |

Voxels of left DLPFC in the contrast map | N/A | LDA | HC=51, SZ=51 Total=102 |

62% | (Yoon et al., 2012) |

|

fMRI- (Monetary Incentive Delay task) |

Schizophrenia | MVPA of task activation pattern (best result for right palladium) |

N/A | Searchlight SVM | HC=44, SZ=44 Total=88 |

93% | (Koch et al., 2015) |

|

fMRI (Sensorimotor task) + SNP |

Schizophrenia | Sparse representation based variable selection |

200 | Sparse representation based classifier |

HC=116, SZ=92 Total=208 |

77% | (Cao et al., 2013) |

|

fMRI (Verbal Fluency task) |

Schizophrenia/bipolar | Thresholded voxels in activation map by ANOVA tests |

N/A | SVM | HC=40, SZ=32, BP=40 Total=104 |

92% | (Costafreda et al., 2011b) |

|

fMRI (Visual task) |

Schizophrenia | Selected active voxels from the contrast map |

346 | Multi voxel pattern analysis (MVPA) |

HC=15, SZ=19 Total=34 |

59-72% | (Yoon et al., 2008) |

|

fMRI (WMT task) |

Schizophrenia with and without OCD |

MVPA on GLM contrast values | 33 | SVM | HC=20, SZ (with OCD)=16, SZ (without OCD)=17, Total=53 |

75-91% | (Bleich-Cohen et al., 2014) |

|

fMRI (AOD task) |

Schizophrenia | ICA Spatial Maps of magnitude and phase data |

135-243 | Multiple kernel learning |

HC=21, SZ=31 Total=52 |

85% | (Castro et al., 2014) |

|

fMRI (AOD task) |

Schizophrenia | ICA (temporal and DMN network) and GLM spatial maps parcellated into AAL atlas |

116 | Recursive composite kernels |

HC=54, SZ=52 Total=106 |

95% | (Castro et al., 2011) |

|

fMRI (AOD task) |

Schizophrenia/bipolar | Distance to mean image for each group build using ICA Spatial Maps (DMN and temporal Lobe) |

3 | Minimum Distance | HC=26, SZ=21, BP=14 Total=61 |

83-95% | (Calhoun et al., 2008) |

|

fMRI (AOD task) |

Schizophrenia/bipolar | ICA Spatial Maps (DMN and temporal Lobe) |

10 | Bayesian Generalized Softmax Perceptron |

HC=25, SZ=21, BP=14 Total=60 |

82-90% (AUC) |

(Arribas et al., 2010) |

|

fMRI (AOD task) and rsfMRI |

Schizophrenia | Kernel PCA on ICA spatial maps | 53 | Fisher's Linear Discriminant |

HC=28, SZ=28 Total=56 |

93-98% | (Du et al., 2012) |

|

fMRI (AOD task) and rsfMRI |

Schizophrenia | FNC scores derived from ICA- based multi- network fusion template for functional normalization |

3 and 100 | LDA and shaplet based classifier |

HC=28, SZ=27 Total=55 |

72% | (Çetin et al., 2015) |

|

fMRI (AOD task) and SNP |

Schizophrenia | Three types of features: selected voxels in fMRI activation map, selected SNPs and ICA components |

261 voxels + 150 SNPs |

Majority voting among 3 SVMs |

HC=20, SZ=20 Total=40 |

87% | (Yang et al., 2010) |

| rsfMRI | Schizophrenia | Functional connectivity among 116 regions in AAL atlas reduced by PCA |

333 | SVM | HC=25, SZ=24, Sibling HC=22 Total=71 |

62% | (Yu et al., 2013b) |

| rsfMRI | Schizophrenia/ MDD |

FC among ROIs | 6670 | SVM | HC=38, SZ=32, MDD=19, Total=89 |

80.9% | (Yu et al., 2013a) |

| rsfMRI | Schizophrenia | Functional connectivity among 347 nodes placed as a grid in the entire brain |

3000 | Fused Lasso, GraphNet |

HC=74, SZ=71 Total=145 |

91% | (Watanabe et al., 2014) |

| rsfMRI | Schizophrenia | fALFF values of the left ITG | N/A | SVM | HC=46, Unaffected Sibling of SCZ patients=46, Total=92 |

75% | (W. Guo et al., 2014) |

| rsfMRI | Schizophrenia | FCamong 90 ROIs | 1096 | Random Forest | HC=18, SZ=18 Total=36 |

75% | (Venkataraman et al., 2012) |

| rsfMRI | Schizophrenia | FC among 90 regions in WFU atlas reduced by PCA |

550 | SVM | HC=22, SZ=22 Total=44 |

93% | (Tang et al., 2012) |

| rsfMRI | Schizophrenia | Functional connectivity (based on extended maximized mutual information) among 116 AAL regions |

6670 | SVM | HC=32, SZ=32 Total=64 |

83% | (Su et al., 2013) |

| rsfMRI | Schizophrenia | Dimension-reduced FC (local linear embedding) among AAL ROIs |

12 | C-Means Clustering |

HC=20, SZ=32 Total=52 |

86% | (Shen et al., 2010) |

| rsfMRI | Schizophrenia | Functional connectivity among 116 regions in AAL atlas |

6670 | Deep Neural Network |

HC=50, SZ=50 Total=100 |

86% | (Kim et al., 2015) |

| rsfMRI | Schizophrenia | Functional connectivity based on ICA decomposition |

46 | Regularized Linear Discriminant classifier |

HC=196, SZ=71 Total=267 |

75-84% | (Kaufmann et al., 2015) |

| rsfMRI | SZ | Graph Measures of Functional connectivity | N/A | SVM | HC=29, SZ=19, Total=48 | 80.0% | (H. Cheng et al., 2015) |

| rsfMRI | Schizophrenia | Local and global Complex network measures |

216 | SVM | HC=10, SZ=8 Total=18 |

100% | (Fekete et al., 2013) |

| rsfMRI | Schizophrenia | Functional connectivity patterns | 6-7 variable |

Ensemble of SVM classifiers |

HC=31, SZ=31 Total=62 |

85-87% | (Fan et al., 2011) |

| rsfMRI | Schizophrenia | Pearson correlation features derived from Regional Homogeneity, ALFF, FALF and Voxel-Mirrored Homotopic Connectivity |

100 | Ensemble of extreme learning machines |

HC=74, SZ=72 Total=146 |

80-91% | (Chyzhyk et al., 2015) |

| rsfMRI | Schizophrenia | Size of connected components in graphs build from correlation among time-courses for 90 AAL regions |

N/A | SVM | HC=29, SZ=29 Total=58 |

75% | (Bassett et al., 2012) |

| rsfMRI | Schizophrenia | Functional network connectivity among 9 ICA time-courses |

45 | SVM (best results) | HC=28, SZ=28 Total=56 |

96% | (Arbabshirani et al., 2013) |

| rsfMRI | Schizophrenia | MVPA based on whole brain thalamic connectivity map |

N/A | SVM | HC=90, SZ=90, Total=180 |

73.9% | (Anticevic et al., 2014) |

| rsfMRI | Schizophrenia | Graph metrics based on FNC computed from ICA |

13 | SVM | HC=74, SZ=72 Total=146 |

65% | (Anderson and Cohen, 2013) |

| sMRI | Schizophrenia | Voxels from five regions based on optimally discriminative voxel-based morphometry |

N/A | SVM | HC=79, SZ=69 Total=148 |

71% | (Zhang and Davatzikos, 2013) |

| sMRI | Schizophrenia (First episode) |

Whole brain volumetric measurements based on RAVENS |

69 | SVM | HC=62, SZ=62 Total=124 |

73% | (Zanetti et al., 2013) |

| sMRI | Schizophrenia (first-episode) |

Volume and mean cortical thickness of selected ROIs |

2.5 | Discriminant Function Analysis |

HC=40, SZ=52 Total=92 |

80% | (Takayanagi et al., 2011) |

| sMRI | Schizophrenia and psychosis |

Cortical GMD | 129 | Sparse multinomial logistic regression classifier |

HC=36, SZ=36 Total=72 |

86% | (Sun et al., 2009) |

| sMRI | Schizophrenia/bipolar | Voxel-wise GM Maps | N/A | SVM | HC1=66, HC2 = 43, SZ1=66, SZ2=46, BP1=66, BP2=47, Total1=198, Total2=136 |

67-90% | (Schnack et al., 2014) |

| sMRI | Schizophrenia | Texture and volumetric measures | N/A | LDA | HC=24, SZ=27, Total=51 | 65.0-72.7% | (Radulescu et al., 2014) |

| sMRI | Schizophrenia | Clinical, neuropsychological, biochemical and volumetric measures |

1050 | SVM | HC=42, SSD=36, Non- SSD=45, Total=123 |

81.0-99.0% | (Pina-Camacho et al., 2015) |

| sMRI | Schizophrenia/bipolar | Volume of 23 ROIs along with 22 neuropsychological test scores |

45 | LDA | HC=8, SZ=10, BP=10 Total=28 |

96% | (Pardo et al., 2006) |

| sMRI | Schizophrenia | GM and CSF volumetric measures of ROIs | 4 | LDA | HC=105, HC2=23, SZ1=38, SZ2=23, Total=189 |

70-76% | (Ota et al., 2012) |

| sMRI | Schizophrenia | Gray matter densities based on voxel-based morphometry of top 10% voxels |

15,700 | SVM | HC1=111, HC2=122, SZ1=128, SZ2=155 Total1=239, Total2=277 |

71% | (Nieuwenhuis et al., 2012) |

| sMRI | Schizophrenia | Volume of several ROIs in the brain | 7 | LDA | HC=47, SZ=57 Total=104 |

78-86% | (Nakamura et al., 2004) |

| sMRI | Schizophrenia/ Mood Disorder |

GM maps of Regional Analysis of brain Volumes in Normalized Space (RAVENS) |

170 | SVM-RFE | Mood Disorder=104, SZ=158 Total=262 |

76% | (Koutsouleris et al., 2015) |

| sMRI | Schizophrenia | The mean expression of Eigen image derived from voxel-based morphometry |

1 | Simple Thresholding |

HC=46, SZ=46 Total=92 |

80-90% | (Kawasaki et al., 2007) |

| sMRI | Schizophrenia (first-episode) |

Whole brain voxel intensity values | N/A(probably thousands) |

maximum- uncertainty LDA |

HC=39, SZ=39 Total=78 |

72% | (Kasparek et al., 2011) |

| sMRI | Recent onset Schizophrenia |

Volumetric measurements of 95 ROIs | 5 | LDA | HC=47, SZ=28 Total=75 |

72% | (Karageorgiou et al., 2011) |

| sMRI | Schizophrenia | MR intensities, gray matter densities and deformation based morphometry |

96 per feature category |

Combination of mMLDA, centroid method, and the average linkage |

HC=49, SZ=49 | 81.6% | (Janousova et al., 2015) |

| sMRI | Schizophrenia | GM and WM maps | N/A | SVM | HC=20, SZ=19, Total=39 | 66.6-77% | (Iwabuchi et al., 2013) |

| sMRI | Schizophrenia (identifying subtypes) |

Multi-edge graphs build from Structural connectivity networks with 78 ROIs |

N/A | Spectral Clustering | HC=29, SZ=23 Total=52 |

78% | (Ingalhalikar et al., 2012) |

| sMRI | Schizophrenia (Childhood onset) |

Cortical Thickness | 74 | Random Forrest | HC=99, SZ=98 Total=197 |

74% | (Greenstein et al., 2012) |

| sMRI | Schizophrenia (cognitive deficit and cognitive spared) |

Whole brain voxel-based morphometry | N/A | SVM | HC=163, SZ=208, SZA=41, Total=412 |

56-72% | (Gould et al., 2014) |

| sMRI | Schizophrenia | Volumetric measurements based on deformation-based morphometry |

39/44 | SVM | HC1=38, HC2=41, SZ1=23, SZ2=46 Total1=61, Total2=87 |

91% | (Fan et al., 2007) |

| sMRI | Schizophrenia | Volumetric measures of all WM, GM and CSF |

69 | SVM-RFE | HC=38, SZ=23 Total=61 |

92% | (Fan et al., 2005) |

| sMRI | Schizophrenia | Whole brain volumetric measurements | N/A | Nonlinear Classifier (not specified) |

HC=79, SZ=69 Total=148 |

81% | (Davatzikos et al., 2005) |

| sMRI | Schizophrenia | Hippocampal and thalamic shape eigenvectors |

25 | Discriminant Function Analysis |

HC=65, SZ=52 Total=117 |

79% | (Csernansky et al., 2004) |

| sMRI | Schizophrenia | Visual words extracted from DLPFC by SIFT and clustered by k-means |

30 | SVM with local kernel |

HC=54, SZ=54 Total=108 |

66-75% | (Castellani et al., 2012) |

| sMRI | Schizophrenia | Surface morpholical Measures | N/A | Semi-supervised (Hierarchical Clustering) |

HC=40, SZ=65, Total=105 |

94.0% | (Bansal et al., 2012) |

| sMRI and dMRI | Schizophrenia/ MDD |

Volume and FA of Insula, thalamus, ACC, Ventricles and corpus callosum |

31 | LDA | MDD=25, SZ=25 Total=50 |

72-88% | (Ota et al., 2013) |

| sMRI, rsfMRI and dMRI | Schizophrenia | Gray matter densities from structural, FA from DTI and ALFF from fMRI |

1863 | SVM | HC=28, SZ=35 Total=63 |

79% | (Sui et al., 2013b) |

2.3 Depressive Disorders

Major depressive disorder (MDD) or unipolar depression characterized by a pervasive low mood, self-esteem and lack of interest in enjoyable activities is a common mental illness affecting adolescents. The lifetime prevalence of MDD is approximately 15–20% (Kessler et al., 2003; Lewinsohn et al., 1986). It is estimated that by the year 2020, depression will account for 15% of the disease burden in the world ranking second after heart disease (Kessler et al., 1994). We reviewed 19 studies that used neuroimaging for automatic diagnose MDD. Those studies are listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Summary of 19 MRI-based depressive disorder classification studies.

| Modality | Disorder | Features | # Features | Classifier | Number of Subjects | Overall Accuracy | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dMRI | MDD | Whole-brain anatomical connectivity patterns |

50 | SVM | HC=26, MDD=22, Total=48 |

91.7% | (Fang et al., 2012) |

|

fMRI (facial affect recognition task) |

MDD | Brain activation maps and ROI-averaged activation features |

N/A | One-class SVM | HC=19, Depressed=19, Total=38 |

63-65.5% (estimated) |

(Mourão-Miranda et al., 2011) |

|

fMRI (gender discrimination and emotional tasks) |

MDD | Sparse network-based features of FC | 9316 | SVM | HC=19, MDD=19, Total=38 |

78.9-85.0% | (Rosa et al., 2015) |

|

fMRI (social concept task) |

MDD | GM maps of PPI analysis | N/A | Maximum Entropy LDA |

HC=21, MDD=25, Total=46 |

78.1% (AUC) |

(Sato et al., 2015) |

|

fMRI (verbal fluency task) |

MDD | Voxel-wise contrast map | 14055 | Regularized Logistic Regression, SVM (best performance) |

HC=31, MDD=31, Total=62 |

90.0-95.0% | (Shimizu et al., 2015) |

| rsfMRI | MDD | FC maps of sACC | N/A | Label Generation Maximum Marging Clustering |

HC=29, MDD=24, Total=53 |

92.5% | (Zeng et al., 2014) |

| rsfMRI | MDI) | Hurst components of resting-state networks | 12 | SVM | HC=20, MDD=20, Total=40 |

90% | (Wei et al., 2013) |

| rsfMRI | MDD | Netowrk-based measures based on FC among ROIs |

2-25 | SVM | HC=22, MDD=21, Total=43 |

99% | (Lord et al., 2012) |

| rsfMRI | MDD | FC among AA1 regions | 31 | SVM | HC=37 MDD=39, Total=76 |

76.6% | (Cao et al., 2014) |

| rsfMRI | First-onset Depressive Disorder |

Graph-theory Measures | 30 | ANN | HC=27, first-onset depression=36, Total=63 |

90.5% | (H. Guo et al., 2014) |

| rsfMRI | Subthreshold Depression |

ReHo features of ROIs | 8 ROIs | Fisher stepwise discriminant analysis |

NC=19, StD=19, Total=37 |

91.9% | (Ma et al., 2013) |

| sMRI | MDD/BP | GM, WM and ventricles volumetric maps (RAVENS) |

53-99 | SVM | HC1=33, HC2=38, MDD=19, BP=23, Total=113 |

54.6-66.1% | (Serpa et al., 2014) |

| sMRI | MDD/BP | Gray matter volumes of Caudate and Ventral Diencephalon |

4 | SVM | HC=61, BP=40, MDD=57, RMD=35, Total=193 |

59.5-62.7% | (Sacchet et al., 2015) |

| sMRI | MDD/BP | Volumetric measurements | 5 | Discriminant function analysis |

HC=22, MDD=32, BP=14, Total=68 |

81.0% | (MacMaster et al., 2014) |

| sMRI | MDD/BP | Cortical thickness and surface area | 18 | SVM | HC=29, MDD=19, BP=16 |

74.3% | (Fung et al., 2015) |

| sMRI | MDD | Feature-based morphometric measures of GM maps |

N/A | SVM and RVM | HC=32, MDD=30, Total=62 |

90.3% | (Mwangi et al., 2012) |

| sMRI | MDD | GM and WM densities | N/A | SVM | HC=42, RDD=23, NDD=23, Total=88 |

58.7-84.6% | (Gong et al., 2011) |

| sMRI | MDD | Cortical thickness of several ROIs | 68 | SVM | HC=15, MDD=18, Total=33 |

70% | (Foland-Ross et al., 2015) |

| sMRI, rsfMRI and dMRI | LLD | Variety of features from each modality | 13 Feature Sets |

Alternating Decision Trees |

EC=35, LLD=33, Total=68 |

87.3% | (Patel et al., 2015) |

2.4 Autism Spectrum Disorder

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a serious neurodevelopmental condition characterized by impaired social communication, deficits in social–emotional reciprocity, deficits in nonverbal communicative behaviors used for social interaction and stereotypic behavior (Association and others, 2003). Although the causation of autism is still largely unknown, it has been suggested that genetic, developmental, and environmental factors could be involved alone or in combination as possible causal or predisposing effects toward developing autism (Minshew and Payton, 1988; Wing, 1997). ASD has an estimated prevalence of 1:68 in the U.S. (Baio, 2012). We surveyed 20 papers in automatic diagnosis of ASD using MRI-based features. Those studies are listed in Table 5.

Table 5.

Summary of 20 MRI-based ASD classification studies.

| Modality | Disorder | Features | # Features | Classifier | Number of Subjects | Overall Accuracy | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dMRI | ASD | FA and MD of selected ROIs | 18 | SVM | TDC=30, ASD=45, Total=75 |

80% | (Ingalhalikar et al., 2011) |

|

fMRI (social interaction task) |

ASD | Activation of selected voxels processed by factor analysis |

4 factors | Gaussian Naïve Bayes |

HC=17, TDC=17, Total=34 |

97% | (Just et al., 2014) |

|

fMRI (two language tasks and a Theory- of-Mind task) |

ASD | AG, MPFC and PCC based FC maps | N/A | Logistic Regression | TD=14, ASD=13, Total=27 |

96.0% | (Murdaugh et al., 2012) |

|

fMRI-Task and DMRI |

ASD | Causal connectivity weights, FC values and FA values |

19 | SVM | TDC=15, ASD=15, Total=30 |

95.9% | (Deshpande et al., 2013) |

| rsfMRI | ASD | ICA components of rsfMRI | 10 components |

Logistic Regression | TDC=20, ASD=20, Total=40 |

78.0% | (Uddin et al., 2013) |

| rsfMRI | ASD | FC among ROIs | Variable | Logistic Regression and SVM (best results) |

TD1=59, TD2=89 ASD1=59, ASD2=89, Total=296 |

76.7% | (Plitt et al., 2015) |

| rsfMRI | ASD | FC among 90 ROIs | 4005 | Probabilistic Neural Network |

TDC=328, ASD=312, Total=640 |

90% | (Iidaka, 2015) |

| rsfMRI | ASD | Functional Connectivity among 220 ROIs | 24090 | Random Forest | TDC=126, ASD=126, Total=252 |

91% | (Chen et al., 2015) |

| rsfMRI | ASD | FC among ROIs | 26,393,745 | Threshodling | TD=40, ASD=40, Total=80 |

79.0% | (Anderson et al., 2011) |

| sMRI | ASD | Thickness and volumetric of ROIs along with interregional features |

N/A | Multi-kernel SVM | HC=59, ASD=58, Total=117 |

96.3% | (Wee et al., 2014) |

| sMRI | ASD | Voxel-wise GM and WM maps | N/A | SVM | TD=24, ASD=24, Total=48 |

92.0% | (Uddin et al., 2011) |

| sMRI | ASD | GM volume map | N/A | SVM | HC=40, ASD=52, ASD- Sib=40 |

80.0-85.0% | (Segovia et al., 2014) |

| sMRI | ASD | Regional thickness measurements extracted from SBM |

7 | Logistic model trees |

HC=16, ASD=22, Total=38 |

87% | (Jiao et al., 2010) |

| sMRI | ASD | Morphometric features of selected ROIs | 314 | SVM | HC=20, ASD=21, Total=41 |

74% (AUC) | (Gori et al., 2015) |

| sMRI | ASD | GM and WM maps | >10,000 | SVM | HC=22, ASD=22, Total=44 |

77% | (Ecker et al., 2010b) |

| sMRI | ASD | Volumetric and geometric features of selected cortical locations |

5 features from each ROI |

SVM | HC=20, ASD=20, Total- 40 |

85% | (Ecker et al., 2010a) |

| sMRI | ASD | Gray maps from VBM-DARTEL | 200 | SVM | TDC=38, ASD=30, Total = 76 |

80.0% (AUC) |

(Calderoni et al., 2012) |

| sMRI | ASD | Volumetric measures and cerebellar vermis area |

9 | Discriminant Function Analysis |

TDC=15, ASD=52, Total=67 |

92.3-95.8% | (Akshoomoff et al., 2004) |

|

sMRI, dMRI and MRS |

ASD | Cortical thickness, FA and neurochemical concentration |

3 | Decision Tree | TD=18, ASD=19, Total=37 |

91.9% | (Libero et al., 2015) |

| sMRI, rsfMRI | ASD | Volume of selected subcortical regions, fALFF, number of voxels and Z-values of selected regions and global VMHC voxel number |

22 | Random Tree Classifier |

TDC=153, ASD=127, Total=280 |

70.0% | (Zhou et al., 2014) |

2.5 Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is one of the most commonly found functional disorders affecting children. Approximately 3–10% of school aged children are diagnosed with ADHD (Biederman, 2005; Dey et al., 2012). Currently, no biological-based measure exists to detect ADHD and instead behavioral symptoms are investigated to identify it. Despite all the research efforts, the root cause of ADHD is still unknown. In 2011, a global competition called ADHD-200 was held in order to use neuroimaging as well as phonotypic measures to automatically detect ADHD (Consortium and others, 2012). Most of the studies reviewed in this survey were responses to that challenge. The main characteristics of those studies are tabulated in Table 6.

Table 6.

Summary of 22 MRI-based ADHD classification studies.

| Modality | Disorder | Features | # Features | Classifier | Number of Subjects | Overall Accuracy | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

fMRI (Stop Task) |

ADHD | Whole brain GLM coefficient map | 21,658 | Gaussian Process Classifier |

HC=30, ADHD=30, Total=60 |

77% | (Hart et al., 2014a) |

|

fMRI (Six Tasks) |

ADHD | Network measures based on FC values | N/A | SVM | ADHD-IA=13, ADHD- C=21, Total=34 |

91.2% | (Park et al., 2015) |

|

fMRI (temporal discrimination task) |

ADHD | Brain Activation Map | N/A | Gaussian Process | HC=20. ADHD=20, Total=40 |

75.0% | (Hart et al., 2014b) |

| rsfMRI | ADHD | ReHo Maps | N/A | PCA-based Fisher discriminative analysis |

HC=12, ADHD=12, Total=24 |

85.0% | (Zhu et al., 2008) |

| rsfMRI | ADHD | ReHo Maps | 6500 | SVM | HC=23, ADHD=23, Total=46 |

80.0% | (Wang et al., 2013) |

| rsfMRI | ADHD | FFT and different varation of PCA on the BOLD signals along with phenotypic measures |

About 7,000 |

SVM | HC=429, ADHD-I=98, ADHD-C=141, Total=668 |

68.86-76% | (Sidhu et al., 2012) |

| rsfMRI | ADHD | ReHO, ALLFand RSN | 400 for each feature type |

Logistic Regression (best performance) |

HC=546, ADHD- IA=122, ADHD-HI=12, ADHD-C=249, Total=929 |

54% ADHD Subtype: 67% |

(Sato et al., 2012) |

| rsfMRI | ADHD | Graph based features based on FC | 150 | SVM-based MVPA | TDC=455, ADHD-I=80, ADHD-C=112 Total=647 |

63.4-82.7% | (Fair et al., 2012) |

| rsfMRI | ADHD | Graph-based measures compressed by Multi-Dimensional Scaling |

2 | SVM | HC=307, ADHD=180, Total=487 |

73.5% | (Dey et al., 2014) |

| rsfMRI | ADHD | Directional connectivity measures | 200 | Artificial Neural Network |

TDC=744, ADHD=433, Total=1177 |

90% | (Deshpande et al., 2015) |

| sMRI | ADHD/Dyslexia | Morphometric measures of ROIs | 6 | Discriminant Function Analysis |

HC=10, ADHD=10, Dyslexia=10, Total=30 |

60.0-87%% | (Semrud-Clikeman et al., 1996) |

| sMRI | ADHD | Cortical thickness measures | 340 | ELM | HC=55, ADHD=55, Total=110 |

90.2% | (Peng et al., 2013) |

| sMRI | ADHD | Voxel-wise GM Volumetric Measures | N/A | Gaussian Process Classifier |

HC=19, ASD=19, ADHD=20 |

68.2-85.2% | (Lim et al., 2013) |

| sMRI | ADHD | WM maps | N/A | SVM | HC=34, ADHD=34, Total=68 |

93% | (Johnston et al., 2014) |

| sMRI | ADHD | Caudate nucleus volumetric measures | N/A | Adaboost and SVM | HC=39 AHDH=39, Total=78 |

72.5% | (Igual et al., 2012) |

| sMRI | ADHD | Texture features based on isotropic local binary patterns on three orthogonal planes |

117- 33630 |

SVM | HC=226, ADHD=210, Total=436 |

69.9% | (Chang et al., 2012) |

| sMRI | ADHD | Surface morphometric measures | N/A | Semi-supervised (Hierarchical Clustering) |

HC=42, ADHD=41, Total=83 |

91.0% | (Bansal et al., 2012) |

|

sMRI + rsfMRI +Phenotypic data |

ADHD | Curvature index, folding index, Gaussian curvature, gray matter volume, mean curvature, surface area, thickness average, and thickness standard deviation along with functional connectivity measures and phenotypic data |

20 | NMF + Decision Tree |

TD=472, ADHD=276, Total=748 |

66.8% | (Anderson et al., 2014) |

| sMRI + rsfMRI | ADHD | Various anatomical, network and non- imaging measures |

5-6000 | SVM | TDC=491, ADHD=285, Total=776 |

80.0% (AUC) |

(Bohland et al., 2012) |

|

sMRI and fMRI- Task(Flanker/NoGo) |

ADHD | Whole brain GLM coefficients and GM maps from VBM |

N/A | SVM | HC=18, ADHD=18, Total=36 |

61.1-77.8% | (Iannaccone et al., 2015) |

| sMRI and rsfMRI | ADHD | Cortical thickness and GM maps from sMRI and ReHo and FC from rsfMRI |

N/A | SVM and Multi- Kernel Learning |

TCD=402, ADHD=222, Total=624 |

61.5% | (D. Dai et al., 2012) |

|

sMRI and rsfMRI |

ADHD | Morphological measures, FC, power spectra and graph measures |

Variable (>100) |

Multiple SVM | TD=491, ADHD=285, Total=776 |

55% | (Colby et al., 2012) |

2.6 Analysis of the Survey

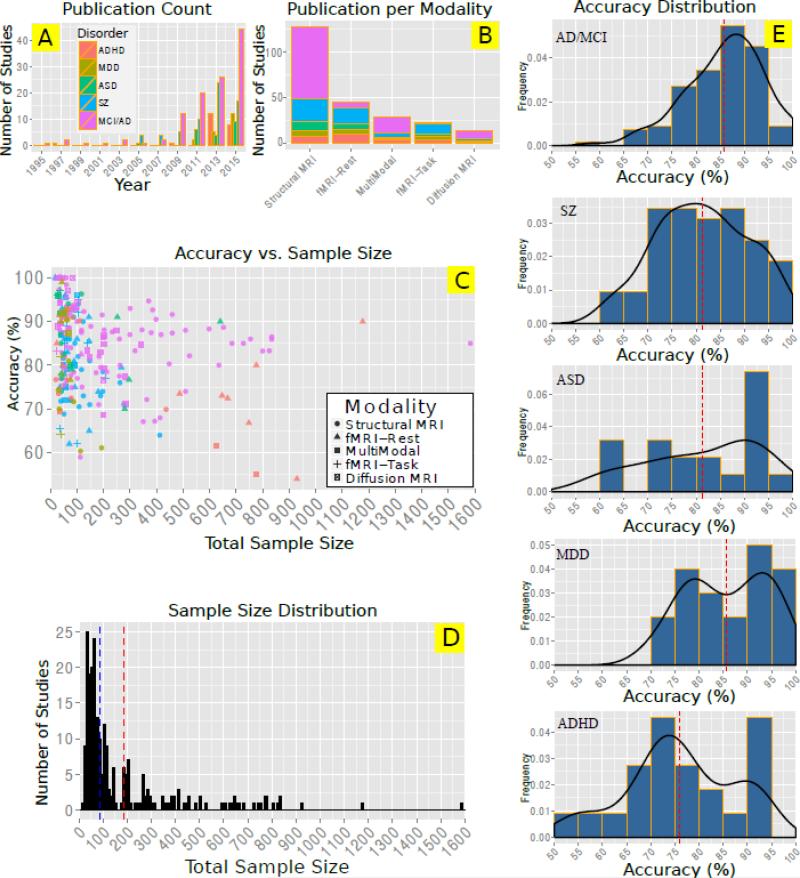

In Figure 3 we illustrate a couple of key aspects of this survey. Figure 3A shows the number of papers published in each year for each disease type. The number of studies has been growing significantly since 2007. There is a peak for ADHD studies in 2012-2013 mainly due to ADHD-200 competition (Consortium and others, 2012) which attracted many scientists. The total number of studies for each modality and each disorder is illustrated in Figure 3B. It is clear that structural MRI is the most popular modality especially for MCI/AD studies thanks to Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) dataset. Combined rest and task fMRI studies are most popular for ADHD and schizophrenia studies. Surprisingly, multimodal studies are more common compared to either task fMRI or diffusion MRI studies. Figure 3C shows the overall accuracy against the total sample size used in the studies. Interestingly, almost all studies that reported very high accuracies, had sample sizes smaller than 100. The reported overall accuracy decreases with sample size in most of disorders such as schizophrenia and ADHD. This pattern raises a serious concern regarding generalizability of many of those studies with small sample sizes. Figure 3D shows the sample size distribution. The dashed lines represent mean (red) and median (blue) sizes, which are 186 and 88 respectively. Finally Figure 3E illustrate the distribution of reported accuracy for each disorder. On average (red dashed lines) MCI/AD and ADHD studies reported the highest and lowest accuracies respectively.

Figure 3.

Visual summary of Table 2-6. A: Total number of papers for two-year intervals for each modality. The inset legend shows the color code for each disorder. This legend also applies to figures in part B and C. B: Number of publications per modality for each disorder C: Scatter plot of overall reported accuracy versus the total sample size. D: Histogram of number of samples used in the surveyed studies. Vertical dashed lines show mean (red) and median (blue) sample size among all studies, which are 186 and 88 respectively. E: Disorder specific histograms of reported accuracies of all surveyed papers. Red dashed line indicates the mean accuracy. Black curves represent the estimated distribution of overall accuracy based on kernel density estimation.

Based on Tables 2-6, the most common extracted features in the surveyed studies are volume and cortical thickness from structural MRI, the activation maps and functional connectivity among ROIs or ICA components from fMRI data and fractional anisotropy from dMRI data. Most common feature reduction methods (not reported in the tables) were based on PCA or univariate statistical tests.

In terms of classification methods, support vector machine (SVM) was by far the most popular method. Different flavors of SVM such as linear, non-linear with different kernel, SVM with recursive feature elimination, SVM with L1 regularization and SVM with L1 and L2 regularization (elastic net) have been used for classification of various disorders. Linear discriminant analysis (under different names) and logistic regression were also popular classification methods among the surveyed studies.

2.7. Predicting Continuous Measures

Most of the studies surveyed above, conducted the diagnosis of a disorder (i.e., assigning a categorical label to each subject) using classification techniques. Pattern regression considers the problem of estimating continuous rather than categorical variables, which can be more challenging as compared to classification. Clinically, pattern regression can be used to estimate the disease stage and progression. Therefore, there is a growing interest in estimating continuous variables such as cognitive scores for brain disorders using neuroimaging measurements. We didn't survey those papers, but we will point out to some of those studies in this section.

Wang et al. proposed a general methodology for estimating continuous clinical variables from high-dimensional imaging data (Wang et al., 2010). Sato et al. used interregional cortical thickness measurements to estimate Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) score in ASD patients (Sato et al., 2013). Stonnington et al. used relevance vector regression (RVR) to predict number of cognitive scores such as Dementia Rating Scale (DRS) and Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale (ADAS) based on structural MRI measures (Stonnington et al., 2010). Tognin et al used RVR to predict Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) scores of subjects at high risk of psychosis based on gray matter volume and cortical thickness measurements (Tognin et al., 2013). Yue et al. showed relationship between functional connectivity and neuropsychological assessment scores such as Rey–Osterrieth Complex Figure Test (CFT) in amnestic MCI patients (Yue et al., 2015). Zahng et al. used MRI, PET and CSF data to predict Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) and ADAS scores in MCI and AD patients (Zhang and Shen, 2012a).

2.8 Detecting/characterizing at Risk Healthy Subjects

The majority of studies surveyed above tried to automatically diagnose one or more disorders in patients. However, detecting or characterizing healthy individuals who are at high risk of brain disorders could potentially delay or prevent future symptoms. There has been a lot of such studies using genetics information but detecting or characterizing at risk subjects based on neuroimaging data is rare. Mourão-Miranda et al. used functional MRI to detect subjects at high risk of mood disorders (Mourão-Miranda et al., 2012). Guo et al. characterized activity of default-mode network in unaffected siblings of schizophrenia patients using resting-state functional data (W. Guo et al., 2014). In another study, Fan et al. studied structural endophenotypes in unaffected family members of schizophrenia patients using machine learning methods (Fan et al., 2008a).

3. Common Machine-learning Pitfalls in Neuroimaging

In this section, common pitfalls among the surveyed papers are discussed.

3.1 Feature Selection Bias

Most of the papers we surveyed consisted of two consecutive parts: group difference analysis and classification. Usually, statistical tests such as t-tests are used to show group differences on a set of extracted features in the first part of the study, which is followed by a classification approach to assess the discrimination ability of those features on a single subject basis. Unfortunately, it is not rare to see that the results of first part (group differences) are used to select features for the classification part. In general, any use of test samples in any part of the training (such as feature extraction, feature selection and classifier training) poses a bias. Selecting features for classification based on the results of group tests that were conducted on the whole dataset is a form of double dipping and therefore leads to a biased (inflated) result (Bishop, 2006; Demirci et al., 2008b).

This form of feature selection also has another major problem. The significance of group statistical tests, which are the basis of feature selection in some of the studies, is mostly based on p-values. However, the relationship between p-value and discrimination power is not straightforward. Figure 1 shows the p-value of a two-sample t-test as well as overall accuracy based on one or two thresholds in three different scenarios. It is seen that low p-value doesn't necessary mean a strong feature (Figure 1A) and high p-value doesn't mean a weak feature (Figure 1B). However, if the abnormality is one-directional, then a very low p-value might translate to high classification accuracy (Figure 1C). So, by discarding features just based on the result of statistical tests sensitive to group mean, valuable discriminatory information could be lost.

Instead of feature selection based on univariate group-level statistical tests, more common filtering and wrapper methods should be used (Blum and Langley, 1997; Hall and Smith, 1998; Kohavi and John, 1997). Filtering methods assign scores to each feature from which a number of top ones can be selected. A good filtering method should be sensitive to the discriminative power of the features. Most of these methods are univariate and therefore each feature is treated independently from other features. Filtering methods have the advantage of low computational cost, but their main drawback is ignoring the relationship among features.

Wrapper methods, on the other hand, consider selection of a set of feature as a search problem. Different combinations are evaluated and finally the best set of features is selected. A popular wrapper method is the recursive feature elimination (RFE) algorithm (Guyon et al., 2002). Wrapper methods are computationally much more expensive than filtering methods, but can result in superior performance by considering interaction among features.

There are methods that aim at combining both filtering and wrapper methods. Minimum-redundancy maximum relevancy (mRMR) is one the methods popular for genetic feature selection. MRMR tries to select features with maximum mutual information with class labels while minimizing the mutual information among those features (G. Brown et al., 2012)

Finally, there are embedded feature selection methods (Guyon and Elisseeff, 2003). These methods combine classification and feature selection into one unified step. Embedded methods learn the features that contribute the most to the accuracy of the model during the training phase. One of the common categories of the embedded methods is using regularization to enforce the learning algorithm to find more parsimonious models with lower complexity and therefore with fewer parameters. A post training analysis of the model coefficients, determines the selected features. Examples of regularization algorithms used in embedded feature selection methods are LASSO, elastic net and ridge regression (Hastie et al., 2004; Ng, 2004; Park and Hastie, 2007; Zou and Hastie, 2005).

3.2 Overfitting

Overfitting happens when a model describes noise in the data rather than the underlying pattern of interest. Overfitting results in very good performance on the observed data and very poor performance on unseen data. Using models that are very complex or have many parameters on datasets with small number of samples and large number of features are more susceptible to overfitting. Neuroimaging datasets have limited number of samples and millions voxels per sample. Based on Figure 3D, the majority of surveyed studies built predictive models based on a very small number of subjects. It is evident from Figure 3C that overall reported accuracy decreases with sample size in our survey. Therefore, it is plausible that many surveyed studies suffer from overfitting problem. It should be noted that by definition, overfitted models work well on the training data and poor on the test data. However, if the process of training and testing is repeated (by varying the model parameters) until a desirable performance on the test data is achieved, the model will likely overfit both the train and test datasets. Cross validation and regularization are common methods to control overfitting. As mentioned earlier, more complex models have a greater chance of overfitting the data. For example, non-linear SVM is more powerful compared to linear SVM but has many more parameters and therefore is also potentially more capable of explaining noise in the data. As discussed in the previous section, proper feature selection can also help to avoiding overfitting.

3.3 Reporting Classification Results