Abstract

TP53 gene deletion is associated with poor outcomes in multiple myeloma (MM). We report the outcomes of patients with MM with and without TP53 deletion who underwent immunomodulatory drug (IMiD) and/or proteasome inhibitor (PI) induction followed by autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant (auto-HCT). We identified 34 patients with MM and TP53 deletion who underwent IMiD and/or PI induction followed by auto-HCT at our institution during 2008-2014. We compared their outcomes with those of control patients (n=111) with MM without TP53 deletion. Median age at auto-HCT was 59 years in the TP53-deletion group and 58 years in the control group (P=0.4). Twenty-one patients (62%) with TP53 deletion and 69 controls (62%) achieved at least partial remission before auto-HCT (P=0.97). Twenty-three patients (68%) with TP53 deletion and 47 controls (42%) had relapsed disease at auto-HCT (P=0.01). Median progression-free survival was 8 months for patients with TP53 deletion and 28 months for controls (P<0.001). Median overall survival was 21 months for patients with TP53 deletion and 56 months for controls (P<0.001). On multivariate analysis of both groups, TP53 deletion (hazard ratio 3.4, 95% confidence interval 1.9-5.8, P<0.001) and relapsed disease at auto-HCT (hazard ratio 2.0, 95% confidence interval 1.2-3.4, P=0.008) were associated with a higher risk of earlier progression. In MM patients treated with PI and/or IMiD drugs, and auto-HCT, TP53 deletion and relapsed disease at the time of auto-HCT are independent predictors of progression. Novel approaches should be evaluated in this high-risk population.

Keywords: High risk multiple myeloma, autologous stem cell transplantation, TP53 gene deletion, deletion chromosome 17

Introduction

The TP53 gene is a well-characterized tumor suppressor that transcriptionally regulates cell cycle progression and apoptosis and is mapped to 17p13.[1] Deletion of TP53 gene can be detected by conventional cytogenetics (deletion of 17p) or by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). In multiple myeloma, 17p deletion is a clinical indicator of very poor prognosis.[2-5] TP53 deletion in multiple myeloma is rare at diagnosis, occurring at rates from 2% to 11% in different studies.[4, 6] However, the incidence of TP53 deletion increases as the disease advances, occurring in up to half of patients with advanced-stage disease,[5, 7] which suggests that TP53 deletion plays an essential role in disease progression.[4, 5, 8] Indeed, clonal evolution studies using FISH indicate that TP53 deletion in multiple myeloma occurs most commonly in subclones.[9] Patients with multiple myeloma and TP53 deletion generally have an aggressive disease course, with a higher prevalence of extramedullary disease and hypercalcemia and shorter overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS).[3-5, 10] Subgroup analyses from several randomized trials in multiple myeloma have shown poor outcomes in patients with 17p deletion, even after treatment with immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs), proteasome inhibitors (PIs), and autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant (auto-HCT).[4, 11-13] The optimal treatment strategy for this high-risk group remains unknown.

In this study, we evaluated clinical outcomes in patients with multiple myeloma and TP53 deletion, identified by FISH studies, who received PIs and/or IMiDs and auto-HCT at our institution. We then evaluated the association between various factors, including TP53 deletion, and risk of disease progression.

Methods

Patients and Study Design

We queried our departmental database to identify consecutive patients with multiple myeloma with a TP53 deletion who underwent auto-HCT at our institution from January 2008 through December 2014. We used an electronic algorithm to identify a matched control group of multiple myeloma patients, from our departmental database, who did not have TP53 deletion and underwent auto-HCT during the same period. The controls were matched to the TP53 deletion cases by age and response to the last therapy before auto-HCT. The ratio of cases to controls used was 3:1. The primary endpoints of this study were 2-year PFS rate and 2-year OS rate. The secondary endpoint was the best response after auto-HCT.

TP53 Deletion

TP53 deletion was determined by FISH analysis of bone marrow aspirates. FISH for each case was performed with the protocol employed in the Clinical Cytogenetics Laboratory at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center using the LSI TP53 Spectrum Orange probe from Abbott Molecular Inc. This probe contains DNA sequences specific to the TP53 gene, mapped to the 17p13.1 region of chromosome 17, and can detect TP53 gene deletions. The cutoff to define a positive test for TP53 gene deletion with this probe with a 95% (P<0.05) confidence limit was 6.2%.[14]

Response and Outcome Definitions

Post-transplant response was assessed at day 100 after auto-HCT. Response and progression were assessed according to the International Myeloma Working Group uniform response criteria.[15] Toxicity was graded using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 4.0. Neutrophil engraftment was defined as the first of 3 consecutive days with an absolute neutrophil count of more than 0.5 × 109/L. Platelet engraftment was defined as the first of 7 consecutive days with a platelet count of more than 20,000 /μL without a platelet transfusion.

Statistical Analysis

Time to event was assessed from the day of auto-HCT. OS and PFS were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method. The incidence of disease progression was estimated with death in the absence of disease considered a competing risk. For OS, death from any cause was considered an event, while for PFS, death or progression was considered an event.[16] Pearson χ2 and Fisher exact tests were used to compare differences between categorical variables, and the rank-sum test was used to compare the distribution of continuous variables. Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was used to compare the OS and PFS rates between the TP53-deletion and control groups and to evaluate predictors of disease progression on univariate and multivariate analysis. Analyses were performed using STATA software (2009; StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Patient Characteristics

Patient and disease characteristics are summarized in Table 1. We identified 34 patients with multiple myeloma with TP53 deletion, who were categorized as the TP53 group, and 111 matched patients with multiple myeloma without TP53 deletion, who were categorized as the control group. Twenty-one patients (62%) in the TP53 group and 69 patients (62%) in the control group had achieved at least a partial response to their last therapy before auto-HCT. Of note, 23 patients (68%) in the TP53 group, in contrast to 47 patients (42%) in the control group, had experienced relapse before auto-HCT. Therapies used for pre-transplant induction and post-transplant maintenance are summarized in table 1. Most patients in both groups received a PI-containing regimen before auto-HCT (TP53: 32 patients [94%], control: 91 patients [82%], P = 0.08). There was no difference between the groups in pre-transplant IMiD exposure (TP53: 24 patients [71%], control: 84 patients [76%], P = 0.55) or the use of post-transplant maintenance therapy (TP53: 19 patients [56%], control: 70 patients [63%], P = 0.4). Among the 15 patients (44%) who did not receive maintenance therapy in the TP53 group, the reasons were: early disease progression (n = 10), low blood counts (n = 2), early death (n = 1), patient refusal (n = 1), and allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant immediately after the auto-HCT (n = 1).

Table 1.

Transplant outcomes

|

TP53 deletion group |

Control group |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 34) | (n = 111) | ||

| Outcome | |||

| Median follow-up duration, mo (range) | 16 (1.5-69) | 25 (0.9-78) | |

| Response, no. (%) | |||

| Overall response (PR/VGPR/CR) | 28 (82) | 103 (92) | 0.07 |

| sCR | 2 (6) | 24 (22) | |

| CR and near CR | 8 (24) | 19 (17) | |

| VGPR | 11 (32) | 35 (32) | |

| PR | 7 (21) | 25 (23) | |

| Stable disease | 4 (12) | 4 (4) | |

| Progressive disease | 2 (6) | 4 (4) | |

| Transplant-related deaths at 100 days, no. | 1 | 0 | 0.05 |

| Grade 3-4 toxic effects, no. (%) | 0.8 | ||

| Infection | 20 (59) | 62 (56) | |

| Hypotension | 5 (15) | 7 (6) | |

| Pulmonary toxic effects | 0 | 5 (5) | |

| Elevation of liver enzymes | 2 (6) | 3 (3) | |

| Gastrointestinal effects | 2 (6) | 5 (5) | |

| Renal impairment | 1 (3) | 3 (3) | |

| Median OS, mo | 21 | 56 | |

| Two-year OS rate, % (95% CI) | 43 (20-63) | 87 (78-93) | <0.001 |

| Median PFS, mo | 8 | 28 | |

| Two-year PFS rate, % (95% CI) | 14 (3-32) | 55 (43-64) | <0.001 |

| Cause of death, no. (%) | 15 (44) | 29 (26) | |

| Disease progression | 14 (41) | 27 (24) | |

| Toxic effects | 1 (3) | 0 | |

| Secondary malignancy | 0 | 1 (1) | |

| Prior malignancy (prostate cancer) | 0 | 1 (1) |

PR: partial response; VGPR: very good partial response; CR: complete response; sCR: stringent complete response; SD: stable disease; PD: progressive disease.

Engraftment and Toxicity

The median number of CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells infused was 4.32 × 106/kg of body weight for the TP53 group and 4.37 × 106/kg of body weight for the control group. All patients in the control group and 33 (97%) patients in the TP53 group. One patient in the TP53 group failed to engraft and subsequently died owing to the graft failure and disease progression. The median times to neutrophil and platelet engraftment were 11 days for both groups. CTCAE grade 3-4 adverse events were observed in 22 patients (65%) in the TP53 group and 69 patients (62%) in the control group (Table 1S). Infections were the most common grade 3-4 adverse events (TP53: 20 patients [59%], control: 62 patients [56%]). This was followed by hypotension (TP53: five patients [15%], control: seven patients [6%]). One patient in the TP53 group died of congestive heart failure 85 days post-transplant, and no patients in the control group died of transplant-related complications during the first 100 days post-transplant.

Response After Auto-HCT

Post-transplant responses are shown in Table 1S. The overall response rate at 100 days post-transplant (partial response, very good partial response, complete response, or stringent complete response) was 82% in the TP53 group and 92% in the control group. Fifteen patients (44%) in the TP53 group and 65 patients (59%) in the control group had an upgrade in their response post-transplant compared to the last response pre-transplant. Two patients (9%) in the TP53 group and four patients (4%) in the control group had evidence of progressive disease at day 100 post-transplant.

Among the patients who received maintenance therapy post-transplant (TP53: 19 patients, control: 70 patients), seven patients (39%) in the TP53 group and 26 patients (37%) in the control group had an upgrade in their response after maintenance therapy compared to their response at day 100 post-transplant.

Survival

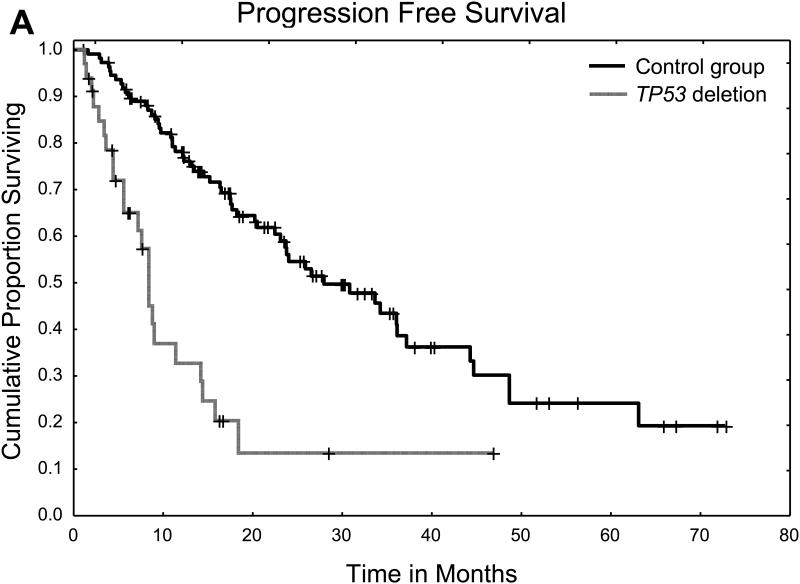

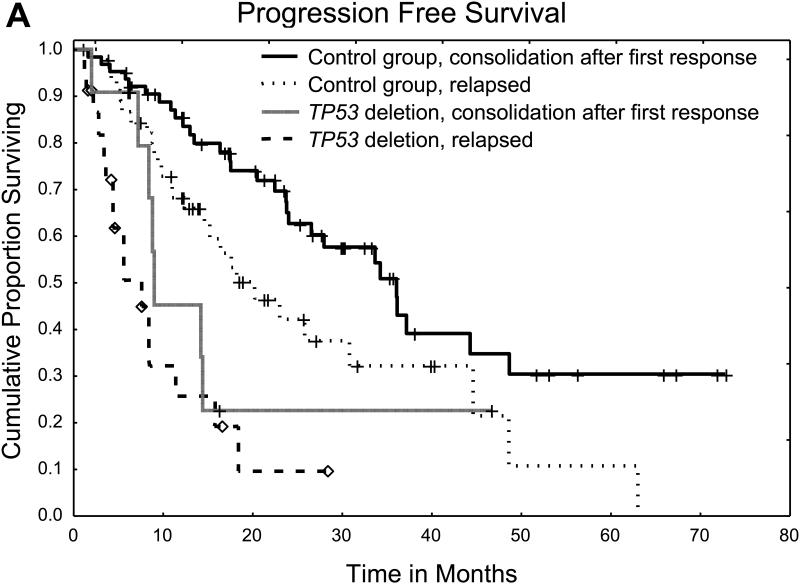

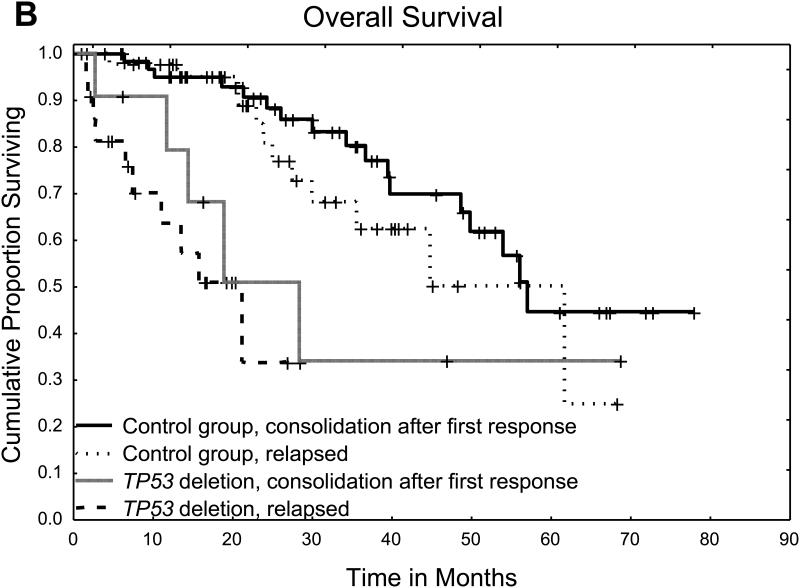

The median follow-up in surviving patients was 16 months (range 1.5-69 months) in the TP53 group and 25 months (range 0.9-78 months) in the control group. The median PFS time was 8 months in the TP53 group and 28 months in the control group, and the 2-year PFS rate was 14% in the TP53 group and 55% in the control group (P < 0.001) (Figure 1A). The median OS time was 21 months in the TP53 group and 56 months in the control group, and the 2-year OS rate was 43% in the TP53 group and 87% in the control group (P < 0.001) (Figure 1B). The causes of death are summarized in Table 1S. The most common cause of death in both groups was disease progression.

Figure 1.

A. Progression free survival for patients with TP53 deletion and controls

B. Overall survival for patients with TP53 deletion and controls

Risk of Progression Among Patients with TP53 Deletion

In the TP53 group, on univariate analysis, no factors were significantly associated with a higher risk of disease progression, including age, response before auto-HCT, time from diagnosis to auto-HCT, International Staging System stage, conditioning regimen, cytogenetic features, and prior exposure to PIs or IMiDs. There was a trend toward higher rates of disease progression in patients with TP53 deletion who had relapsed disease at the time of auto-HCT; however, this trend was not statistically significant (Table 2S).

Univariate and Multivariate Analysis of Risk of Progression in Both Groups

We then assessed the independent effects of TP53 deletion and other factors on the risk of disease progression in the combined cohort of patients with TP53 deletion and controls (Table 2). On univariate analysis, the presence of TP53 deletion and relapsed disease at the time of auto-HCT were the only factors associated with a significantly higher risk of disease progression. These two factors remained significantly associated with disease progression risk on multivariate analysis and were also associated with shorter PFS and OS (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of risk of progression at 2 years among patients with TP53 deletion and controls (n = 145)

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Hazard | 95% CI | P | Hazard | 95% CI | P | |

| Factor | ratio | value | ratio | value | ||

|

TP53 deletion (ref: absence of TP53

deletion) |

3.8 | 2.2-6.7 |

<0.00

1 |

3.4 | 1.9-5.8 | <0.001 |

| Age above 60 years (ref: ≤60 years) | 0.9 | 0.5-1.5 | 0.7 | |||

| Time from diagnosis to auto-HCT of less than 1 year (ref: >1 year) |

1.6 | 0.98-2.7 | 0.06 | |||

| Relapsed disease at time of transplant (ref: other) |

2.3 | 1.4-3.9 | 0.001 | 2.0 | 1.2-3.4 | 0.008 |

| Less than PR as last response before transplant (ref: other) |

1.1 | 0.6-1.8 | 0.8 | |||

| Conditioning regimen (melphalan vs. others) |

0.9 | 0.5-1.5 | 0.7 | |||

Ref: reference; CI: confidence interval; PR: partial response.

Figure 2.

A. Progression free survival for patients with TP53 deletion and controls according to disease status at time of transplant

B. Overall survival for patients with TP53 deletion and controls according to disease status at time of transplant

Discussion

The presence of TP53 deletion in patients with multiple myeloma is associated with a poor prognosis, [17-21] and the optimal management of these high-risk cases remains controversial.[2] In this study, we retrospectively analyzed the clinical outcomes and response to therapy in patients with multiple myeloma and TP53 deletion, identified by FISH studies, who received PI- and/or IMiD-containing induction followed by auto-HCT. We compared these patients’ clinical outcomes with those of a matched control group of patients with multiple myeloma without TP53 deletion. Although both groups received induction therapy with PIs and/or IMiDs followed by auto-HCT and in most cases maintenance therapy and despite similar overall response rates following auto-HCT and similar toxic effects, the TP53 group had significantly worse survival outcomes. This difference was due primarily to a higher risk of progression in the TP53 group (median PFS 8 months in the TP53 group vs. 28 months in the control group). Indeed, the most common cause of death in the TP53 group was disease progression, with only one patient dying of transplant-related complications.

We then sought to identify risk factors within the TP53 group that could affect the risk of progression. On univariate analysis of the TP53 group alone, the only factor associated, although not significantly, with a higher risk of progression was having relapsed disease at the time of the transplant. Age, International Staging System stage, response to last therapy before auto-HCT, and a pre-transplant induction containing a combination of PI and IMiD did not significantly affect the risk of disease progression in this group. This result was confirmed on multivariate analysis of both groups, in which the presence of TP53 deletion and having relapsed disease at the time of the transplant were the only independent risk factors associated with a higher risk of disease progression. Moreover, patients with TP53 deletion who had relapsed disease at the time of the transplant had worse outcomes than those who received the transplant as consolidation after initial induction, highlighting the worse outcomes in patients who develop TP53 deletion later in their disease course than in those who TP53 deletion found at the time of initial diagnosis. Overall, patients with TP53 deletion early or late in their disease course had worse outcomes than their control group counterparts.

The ability of novel drugs followed by auto-HCT and maintenance therapy to overcome the negative effects of high-risk cytogenetic features in multiple myeloma remains debatable.[2] The HOVON-65/GMMG-HD4 trial suggested that the adverse impact of 17p deletion could be reduced by incorporating bortezomib in both pre-transplant induction and post-transplant maintenance therapy.(12) Similarly, the Italian Group for Hematologic Diseases in Adults (GIMEMA) suggested that pre-transplant bortezomib, thalidomide, and dexamethasone (VTD) induction could overcome the poor prognostic impact of high-risk cytogenetic features, including 17p deletion.[13] Also, the Myeloma Institute at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences reported that Total Therapy 3, which incorporated VTD in induction, consolidation, and maintenance, overcame the adverse impact of TP53 deletion.[22] However, other studies failed to show the benefit of novel agents and auto-HCT in patients with 17p deletion. A phase III trial by the Spanish Myeloma Group (PETHEMA-GEM), in contrast to the GIMEMA study, found that VTD was unable to overcome the poor prognostic impact of 17p deletion in high-risk multiple myeloma.[11] Likewise, the Intergroupe Francophone du Myélome (IFM) trial IFM-2005-01, which reported on the use of bortezomib plus dexamethasone versus vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone (VAD) induction followed by auto-HCT, did not show improvement in PFS or OS in a subgroup of patients with 17p deletion receiving the bortezomib-based induction regimen (4-year OS 50% in patient with 17p deletion vs. 79% in patients without 17p deletion).[17] In our retrospective analysis, although all patients had prior exposure to a PI and/or an IMiD, the PFS and OS rates were significantly lower in the TP53 group whether the TP53 deletion was detected at diagnosis or at relapse.

These results clearly demonstrate that there is significant room for improvement in the transplant management of multiple myeloma with TP53 deletion. Although post-transplant maintenance, as described by the Hemato-oncology Foundation for Adults in the Netherlands (HOVON) group, may help abrogate the risk associated with TP53 deletion, other transplant-specific approaches may improve outcomes further. Improved CR rates post-transplant are associated with an improved 5-year OS rate of up to 80% at 5 years.[23] Additionally, the depth of response in patients with TP53 deletion may be more significant than in intermediate- or standard-risk disease. One study by Haessler et al. demonstrated improved OS in a small number of patients whose disease had 17p deletion who attained a CR after receiving a tandem auto-transplant, although this benefit was not seen in the low-risk group.[24] The Bologna 96 study demonstrated higher CR rates in patients with multiple myeloma who received tandem auto-transplants than in those who received single auto-transplants (33% with single vs. 47% with tandem, P = 0.008), making tandem auto-SCT a promising approach for the treatment of high-risk disease where a CR may be beneficial.[25] While cytogenetic features were not evaluated in this study, its results led to the creation of a phase III randomized trial, CTN 0702, comparing tandem transplants versus single transplants versus single transplants followed by lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (RVD) consolidation. All patients received lenalidomide maintenance. This protocol has closed to accrual, and the results may inform whether tandem auto-HCT may be beneficial in a subgroup of patients.

Our study reported here has weaknesses inherent to a retrospective analysis, including patient heterogeneity and selection bias. However, we tried to overcome these limitations by using a matched control arm of patients who were treated during the same time period. Even with this matching, the proportion of patients with relapsed disease was higher in the TP53 group than in the control group, which may have adversely affected the outcomes in the TP53 group.

A number of treatment approaches are being explored for patients with multiple myeloma with TP53 deletion. Some centers recommend intense up-front combination therapy (e.g., lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (RVD) followed by up-front auto-HCT to maximize CR rates, and then by PI-based maintenance therapy to maintain the response.[26] Allogeneic HCT, although controversial, is being explored in clinical trials.[27, 28] Currently, the Bone and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network is conducting a multicenter phase II study (BMT CTN 1302, or NCT02440464) investigating the utility of frontline allogeneic HCT in patients with multiple myeloma with high-risk cytogenetics. Additionally, novel conditioning regimens, such as the busulfan and melphalan regimen, currently under investigation at MD Anderson Cancer Center, may improve CR rates and other outcomes in patients with high-risk multiple myeloma. Other emerging approaches include the use of monoclonal antibodies such as elotuzumab and daratumumab that have shown responses in patients with 17p deletion.[29, 30] Cellular therapy directed against clonal plasma cells is another promising approach.[31, 32] Finally, novel approaches of targeting intracellular pathways, such as MDM2 in patients with 17p deletion, are also being explored.[33]

In conclusion, we found that patients with TP53 deletion continue to have poor outcomes with the current approach of PI-based induction followed by auto-HCT and that TP53 deletion and relapsed disease at the time of auto-HCT are each associated with a higher risk of progression. Novel treatments are needed for these high-risk cases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center is supported in part by the National Institutes of Health through Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA016672 and used Cancer Center Support Grant shared resources. This project was part of the Myeloma Moon Shots Program to understand the biology and outcome of high-risk myeloma.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to declare.

Author Contributions

S.G. and M.Q. designed the study, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript; S.S., G.R. and R.D. prepared the data; R.S. performed the statistical analysis; G.L, J.E.B., N.S., Q.B., K.P., F.B., S.P., C.H., U.P., J.J.S., E.E.M., R.Z.O., R.C. reviewed and interpreted the data, and edited the manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Levine AJ. p53, the cellular gatekeeper for growth and division. Cell. 1997;88:323–331. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81871-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fonseca R, Bergsagel PL, Drach J, et al. International Myeloma Working Group molecular classification of multiple myeloma: spotlight review. Leukemia. 2009;23:2210–2221. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fonseca R, Blood E, Rue M, et al. Clinical and biologic implications of recurrent genomic aberrations in myeloma. Blood. 2003;101:4569–4575. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-10-3017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Avet-Loiseau H, Attal M, Moreau P, et al. Genetic abnormalities and survival in multiple myeloma: the experience of the Intergroupe Francophone du Myelome. Blood. 2007;109:3489–3495. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-040410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drach J, Ackermann J, Fritz E, et al. Presence of a p53 gene deletion in patients with multiple myeloma predicts for short survival after conventional-dose chemotherapy. Blood. 1998;92:802–809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chng WJ, Price-Troska T, Gonzalez-Paz N, et al. Clinical significance of TP53 mutation in myeloma. Leukemia. 2007;21:582–584. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neri A, Baldini L, Trecca D, et al. p53 gene mutations in multiple myeloma are associated with advanced forms of malignancy. Blood. 1993;81:128–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang H, Qi C, Yi QL, et al. p53 gene deletion detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization is an adverse prognostic factor for patients with multiple myeloma following autologous stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2005;105:358–360. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cremer FW, Bila J, Buck I, et al. Delineation of distinct subgroups of multiple myeloma and a model for clonal evolution based on interphase cytogenetics. Genes, chromosomes & cancer. 2005;44:194–203. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tiedemann RE, Gonzalez-Paz N, Kyle RA, et al. Genetic aberrations and survival in plasma cell leukemia. Leukemia. 2008;22:1044–1052. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosinol L, Oriol A, Teruel AI, et al. Superiority of bortezomib, thalidomide, and dexamethasone (VTD) as induction pretransplantation therapy in multiple myeloma: a randomized phase 3 PETHEMA/GEM study. Blood. 2012;120:1589–1596. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-02-408922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sonneveld P, Schmidt-Wolf IG, van der Holt B, et al. Bortezomib induction and maintenance treatment in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: results of the randomized phase III HOVON-65/ GMMG-HD4 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2946–2955. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.6820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cavo M, Tacchetti P, Patriarca F, et al. Bortezomib with thalidomide plus dexamethasone compared with thalidomide plus dexamethasone as induction therapy before, and consolidation therapy after, double autologous stem-cell transplantation in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: a randomised phase 3 study. Lancet. 2010;376:2075–2085. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61424-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu G, Muddasani R, Orlowski RZ, et al. Plasma cell enrichment enhances detection of high-risk cytogenomic abnormalities by fluorescence in situ hybridization and improves risk stratification of patients with plasma cell neoplasms. Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine. 2013;137:625–631. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2012-0209-OA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Durie BG, Harousseau JL, Miguel JS, et al. International uniform response criteria for multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2006;20:1467–1473. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dinse GE, Lagakos SW. Nonparametric estimation of lifetime and disease onset distributions from incomplete observations. Biometrics. 1982;38:921–932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Avet-Loiseau H, Leleu X, Roussel M, et al. Bortezomib plus dexamethasone induction improves outcome of patients with t(4;14) myeloma but not outcome of patients with del(17p) J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4630–4634. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.3945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dimopoulos MA, Kastritis E, Christoulas D, et al. Treatment of patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma with lenalidomide and dexamethasone with or without bortezomib: prospective evaluation of the impact of cytogenetic abnormalities and of previous therapies. Leukemia. 2010;24:1769–1778. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smetana J, Berankova K, Zaoralova R, et al. Gain(1)(q21) is an unfavorable genetic prognostic factor for patients with relapsed multiple myeloma treated with thalidomide but not for those treated with bortezomib. Clinical lymphoma, myeloma & leukemia. 2013;13:123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2012.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neben K, Lokhorst HM, Jauch A, et al. Administration of bortezomib before and after autologous stem cell transplantation improves outcome in multiple myeloma patients with deletion 17p. Blood. 2012;119:940–948. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-379164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moreau P, Cavo M, Sonneveld P, et al. Combination of international scoring system 3, high lactate dehydrogenase, and t(4;14) and/or del(17p) identifies patients with multiple myeloma (MM) treated with front-line autologous stem-cell transplantation at high risk of early MM progression-related death. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2173–2180. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.0329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shaughnessy JD, Zhou Y, Haessler J, et al. TP53 deletion is not an adverse feature in multiple myeloma treated with total therapy 3. British journal of haematology. 2009;147:347–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07864.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kapoor P, Kumar SK, Dispenzieri A, et al. Importance of achieving stringent complete response after autologous stem-cell transplantation in multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:4529–4535. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.0086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haessler J, Shaughnessy JD, Jr., Zhan F, et al. Benefit of complete response in multiple myeloma limited to high-risk subgroup identified by gene expression profiling. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2007;13:7073–7079. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cavo M, Tosi P, Zamagni E, et al. Prospective, randomized study of single compared with double autologous stem-cell transplantation for multiple myeloma: Bologna 96 clinical study. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2434–2441. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.2509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lonial S, Boise LH, Kaufman J. How I treat high risk myeloma. Blood. 2015 doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-06-653261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosinol L, Perez-Simon JA, Sureda A, et al. A prospective PETHEMA study of tandem autologous transplantation versus autograft followed by reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic transplantation in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Blood. 2008;112:3591–3593. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-141598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bruno B, Rotta M, Patriarca F, et al. A comparison of allografting with autografting for newly diagnosed myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1110–1120. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lonial S, Dimopoulos M, Palumbo A, et al. Elotuzumab Therapy for Relapsed or Refractory Multiple Myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2015 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1505654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lokhorst HM, Plesner T, Laubach JP, et al. Targeting CD38 with Daratumumab Monotherapy in Multiple Myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1207–1219. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garfall AL, Maus MV, Hwang WT, et al. Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells against CD19 for Multiple Myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1040–1047. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rapoport AP, Stadtmauer EA, Binder-Scholl GK, et al. NY-ESO-1-specific TCR-engineered T cells mediate sustained antigen-specific antitumor effects in myeloma. Nat Med. 2015;21:914–921. doi: 10.1038/nm.3910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gu D, Wang S, Kuiatse I, et al. Inhibition of the MDM2 E3 Ligase induces apoptosis and autophagy in wild-type and mutant p53 models of multiple myeloma, and acts synergistically with ABT-737. PloS one. 2014;9:e103015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.