Abstract

Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi, or Chinese skullcap, has been widely used as a medicinal plant in China for thousands of years, where the preparation from its roots is called Huang-Qin. It has been applied in the treatment of diarrhea, dysentery, hypertension, hemorrhaging, insomnia, inflammation and respiratory infections. Flavones such as baicalin, wogonoside and their aglycones baicalein wogonin are the major bioactive compounds extracted from the root of S. baicalensis. These flavones have been reported to have various pharmacological functions, including anti-cancer, hepatoprotection, antibacterial and antiviral, antioxidant, anticonvulsant and neuroprotective effects. In this review, we focus on clinical applications and the pharmacological properties of the medicinal plant and the flavones extracted from it. We also describe biotechnological and metabolic methods that have been used to elucidate the biosynthetic pathways of the bioactive compounds in Scutellaria.

Keywords: Scutellaria baicalensis, Flavonoids, Anti-cancer, Metabolic biology, Medicinal plants

摘要

黄芩是一种常用的药用植物, 中国人对它的使用了已有数千年历史。黄芩根的制备物, 为常用的中药材, 在中国传统医学中用来治疗腹泻、痢疾、高血压、出血、 失眠、炎症和呼吸道感染。黄芩根中主要的活性物质为黄酮物质黄芩苷, 汉黄芩苷及 苷元黄芩素, 汉黄芩素。药理学研究显示这些黄酮物质具有多种药物学活性, 包括抗 癌, 保肝、抗菌、抗病毒、抗氧化、抗惊厥和神经系统保护作用。在本综述里面, 我 们集中介绍了黄芩的临床应用及药物学活性。我们也介绍了用于研究黄芩中活性物质 代谢途径的生物技术及代谢生物学方法。

Introduction

Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi is a species of flowering plant in the Lamiaceae family (Fig. 1a). It is indigenous to several East Asian countries and the Russian Federation and has been cultivated in many European countries [1, 2]. Chinese people have used the dried root of this medicinal plant for more than 2000 years as a traditional medicine known as Huang-Qin (Fig. 1b) and it is now listed officially in the Chinese Pharmacopoeia. The dried root of Huang-Qin is often prepared by decoction (boiling) or as tinctures [3]. Huang (黄) means yellow. Qin (芩) is equivalent to Jin (菳), and means golden herb, as explained in Shuowen Jiezi, an early 2nd-century Chinese dictionary from the Han Dynasty [4, 5]. Huang-Qin was first recorded in Shennong Bencaojing (The Classic of Herbal Medicine), written between about 200 and 250 AD, for treatment of bitter, cold, lung and liver problems [6]. The most authoritative book on traditional Chinese medicine, Bencao Gangmu (Compendium of Materia Medica) which was first published in 1593, reported that Scutellaria baicalensis (Fig. 1c) had been used in the treatment of diarrhea, dysentery, hypertension, hemorrhaging, insomnia, inflammation and respiratory infections. Its author, Li Shizhen, reported successful self-administration to treat a severe lung infection when he was 20 years old [4].

Fig. 1.

(Color online) The medicinal plant Scutellaria baicalensis, known as Huang-Qin. a Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi plant. b The dried root of S. baicalensis used in traditional Chinese medicine. c A hand-drawn figure of S. baicalensis in Bencao Gangmu (Compendium of Materia Medica) by Li Shizhen

Clinical applications

Scutellaria baicalensis has been used as a medicine in several East Asian countries for more than 2000 years. Clinical data for this herb are accumulating and Huang-Qin alone has been reported to be useful for treating colds and bacterial pneumonia [7, 8].

In many Eastern countries, Huang-Qin is prescribed as a part of a multi-herb formulation. Huang-Qin is an important ingredient of Xiaochai Hutang (Chinese) or Sho-saiko-to (SST, Japanese) preparations, first described in Shanghan Lun (On Cold Damage), written by Zhang Zhongjing around 200 AD [9]. This formulation was described as having ‘worked effectively in some instances where conventional Western therapies failed or proved to be insufficient to provide a palliative cure’ by Xue and Roy in 2003 [10] and was subsequently taken up by the alternative medicine community in the USA [11]. A study of the effects of SST on hepatitis was reported by a Japanese group in 1994 [12]. Ninety-eight hepatitis patients were treated with SST and followed up for 5 years. Liver function was improved in 78 % of the hepatitis B patients and in 67 % patients with non-A non-B type hepatitis, with significantly reduced serum levels of aminotransferase AST, ALT, and rGTP [12]. SST is also effective in hepatitis C patients. Eighty hepatitis C patients who were interferon-resistant were treated with SST combined with a common unspecified medicine or the common medicine alone. These patients were studied for 7 years during which time, 5 patients on the SST treatment achieved fully normalized enzyme functions. Liver enzyme normalization was observed in only one control patient. Conversely, 5 control patients (common medicine alone) progressed to liver cancer compared to just one on the SST combination therapy [13].

Lung Fufang, another traditional prescription using Huang-Qin, can prolong the survival rate of patients with primary bronchial pulmonary squamous cell carcinoma [14], and it has a similar effect on NSCLC (non-small-cell lung cancer) patients. Elderly people suffering from NSCLC and treated with Lung Fufang Prescription showed improved indices for the clinical syndrome and improved quality of life compared to the control group who were treated with normal chemotherapy plus a TCM (Traditional Chinese Medicine) placebo [15]. Huang-Qin is also a major ingredient of Fuzheng anti-cancer prescription, which has been used in combination with chemotherapy and shown to have improved outcomes on NSCLC in middle and late stage patients, compared to conventional chemotherapy alone [16].

Pharmacology of Huang-Qin

Antitumor effects

Many studies have shown that S. baicalensis extract is cytotoxic to a broad range of cancer cells from humans, including brain tumor cells [17], prostate cancer cells [18] and HNSCC (head and neck squamous cell carcinoma) cell lines [19]. Aqueous extracts of S. baicalensis roots induced apoptosis and therefore suppressed growth of lymphoma and myeloma cell lines, by changing the expression levels of Bcl genes, increasing cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27 (KIP1) activity and decreasing expression of the c-myc oncogene [20]. Similarly, S. baicalensis extracts were selectively toxic to several human lung cancer cell lines, but not to normal human lung fibroblasts. Increases in p53 and Bax protein activities may be responsible for these effects [21].

The flavones baicalin, wogonoside and their aglycones baicalein and wogonin are the major bioactives in Scutellaria roots and the major bioactive constituents responsible for anti-cancer effects of Huang-Qin [22–24]. Baicalin inhibits growth of lymphoma and myeloma cells [20]. Wogonoside has anticancer effects on acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cell lines and on primary patient-derived AML cells. It increases significantly the transcription of phospholipid scramblase 1 (PLSCR1), a regulator of the cell cycle and differentiation-related genes [25]. Baicalin, baicalein and wogonin have similar effects as S. baicalensis extracts against lung cancer cells [21]. The anti-cancer activities of the Scutellaria-derived flavones have been mainly ascribed to their ROS scavenging ability, attenuation of NF-κB activity, cell cycle gene expression, COX-2 gene expression and prevention of viral infections [22, 26, 27].

In a high-throughput screen of over 4000 compounds to detect genotoxic compounds using a quantitative cell-based assay, Fox et al. [28] identified 22 antioxidants, including baicalein. Treatment of dividing cells with baicalein induced DNA damage and resulted in cell death. Despite this genotoxic effect, baicalein did not induce mutations, a major problem of conventional anticancer drugs, suggesting that baicalein and related flavones are strong candidates for improved chemotherapeutic agents [28].

Hepatoprotection

Scutellaria baicalensis is the main component in the herbal remedy SST used for liver problems such as hepatitis, hepatic fibrosis and carcinoma [11, 29, 30]. Yang-Gan-Wan (YGW) is another prescription containing baicalin, which has long been known for its protective effects on the liver [31, 32]. This herbal prescription prevents and reverses activation of hepatic stellate cells, (HSC; the major pathogenic cell type in fibrogenesis) by epigenetic derepression of PPARγ (Peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor γ), so preventing liver fibrosis. Baicalin is a major active phytocompound in Yang-Gan-Wan (YGW) and suppresses the expression and signaling by canonical Wnts, which are involved in epigenetic repression of PPARγ [33].

Several studies have suggested that S. baicalensis can effectively inhibit fibrosis and lipid peroxidation in rat liver [34–36]. Consumption of the roots and shoots of S. baicalensis inhibits mutagenisis caused by the aflatoxin-B1 mycotoxin in rat liver cells [35]. The anti-fibrosis activity of S. baicalensis root extracts may be due to enhanced phosphorylation of the cAMP response element binding protein as proposed by Tan et al. [37], although extracts of Scutellaria baicalensis roots also arrest the cell cycle, activate the caspase system and activate ERK-p53 pathways resulting in apoptosis of HSC-T6 cells to prevent hepatic fibrosis [38].

Antibacterial and antiviral activities

Amongst 46 herb and spice extracts, S. baicalensis extracts have shown substantial antibacterial effects against Bacillus cereus, Escherichia coli, Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella anatum and Staphylococcus aureus [39]. Aqueous extracts of S. baicalensis roots have antimycotic properties against Aspergillus fumigatus, Candida albicans, Geotrichumcandidum and Rhodotorula rubra [40]. Baicalin, isolated from S. baicalensis, has been applied as a natural antibacterial agent against foodborne pathogens such as Salmonella and Staphylococcus spp. in homemade mayonnaise [41]. Extracts of S. baicalensis can also enhance the antimicrobial activity of several antibiotics such as ciprofloxacin, ceftriaxone, gentamicin and penicillin G, against Staphylococcus aureus [42].

Xiaochai Hutang or Sho-saiko-to (SST) is effective against hepatitis, and a reduction of viral load has been observed in some patients treated with SST [11], indicating an antiviral function of Scutellaria extracts [43]. Scutellaria root extracts can inhibit the replication of HCV-RNA significantly [44].

Baicalin has very good anti-HIV-1 activity as a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor [45]. Moreover, baicalin can prevent the entry of HIV-1 into animal cells by perturbing the interaction between HIV-1 Env and HIV-1 co-receptors on the cell surface [46]. Baicalin has been adopted as one of the popular lead natural products for preventing HIV infection [47]. Differences in the inhibitory activities of baicalein and baicalin against HIV-1 reverse transcriptase have been evaluated by Zhao et al. [48]. They found that baicalein has four times stronger inhibitory activity on HIV-1 reverse transcriptase than baicalin. However, baicalin can be deglycosylated to form baicalein in the human body [48].

Aqueous extracts of S. baicalensis elicit significant inhibition (91.1 %) of HIV-1 protease activity at concentrations of 200 µg/ml [49]. Early in 1989, Ono et al. [50] reported baicalein could effectively inhibit reverse transcriptase activity of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV); 2 μg/mL baicalein inhibiting 90 % of the activity of HIV reverse transcriptases [50]. Baicalein is also an inhibitor of HIV-1 integrase, an essential enzyme in the life cycle of the virus, by binding to the hydrophobic region of the HIV-1 integrase catalytic core domain to induce a conformational change [51]. These effects of baicalein and baicalin on HIV have attracted considerable attention [52].

Other effects

In addition to the effects described above, preparations of S. baicalensis can also work as antioxidants, ROS scavengers [53, 54] and anticonvulsants [55]. Recently, the neuroprotective effects of S. baicalensis and its component flavones, have been studied using both in vitro and in vivo models of neurodegenerative diseases. Results suggest that this medicinal plant may have promising applications in neuroprotection [56, 57].

Biotechnology to enhance S. baicalensis synthesis

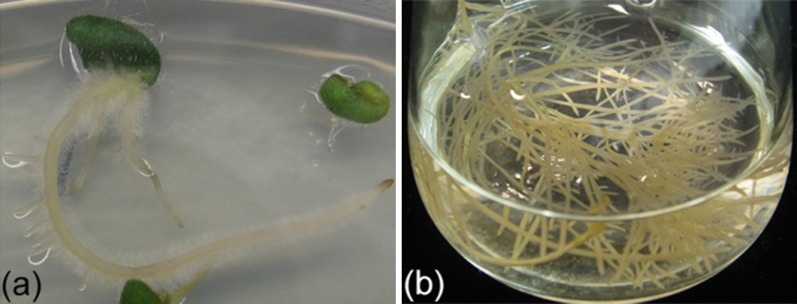

Given their established bioactivity, the possibility to enhance production of the flavones in this plant or alternatively produce them in common vegetables or fruits is attractive [58, 59]. Understanding the regulation of production of bioactive flavones (baicalein, baibalin, wogonin and wogonoside) and their biosynthesis in S. baicalensis, and developing strategies to enhance their production are important objectives. However, like other members of the mint family, stable genetic transformation and regeneration of this plant are very difficult. Agrobacterium rhizogenes-mediated production of hairy roots of S. baicalensis has proved to be effective in this recalcitrant species [60, 61] (Fig. 2). Hairy roots can be induced from either leaf or cotyledon explants [62, 63] in an A. rhizogenes strain-dependant manner. Among the four strains (A4GUS, R1000 LBA 9402 and ATCC11325) tested by Tiwari et al.(2008), the A4 stain produced the most hairy roots, with an efficiency of 42.6 % [60]. Supplementation of acetosyringone during co-cultivation of plant tissue and A. rhizogenes enhanced the transformation efficiency further [64]. Hairy root cultures of S. baicalensis have a similar metabolite pattern to natural roots and the major flavones can be enhanced by treatment of cultures with methyl jasmonate [65–67]. Over-expression of PAL or CHI in hairy roots of Scutellaria leads to enhanced levels of root-specific flavones [63, 68] (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

(Color online) Production of hairy root cultures of Scutellaria baicalensis. a Hairy roots induced by infection of a cotyledonary explant of S. baicalensis by Agrobacterium rhizogenes. b Liquid culture of Scutellaria hairy roots

Table 1.

Composition of multi-herb formulations containing S. baicalensis

| Name | Compositions | References |

|---|---|---|

| Xiaochai Hutang | Scutellaria baicalensis, Bupleurum falcatum, Pinellia ternate, Panax ginseng, Glycyrrhiza uralensis, Zingiber officinale, Ziziphus jujuba | [9, 11] |

| Lung fufang | Panax ginseng, Astragalus membranaceus, Lycium barbarum, Glossy privet fruit (Ligustrum lucidum), Sichuan fritillary bulb (Fritillaria cirrhosa), Radix Ophiopogonis (Ophiopogon japonicus), Platycodon grandiflorum, Scutellaria baicalensis, Lily bulb (Lilium brownii), Curcuma zedoary, pseudo-ginseng (Panax notoginseng), Oldenlandia diffusa | [14, 15] |

| Fuzheng anti-cancer prescription | Astragalus membranaceus, American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius), Citrus reticulate, Pinellia ternate, Scutellaria baicalensis, Poria cocos, Atractylodes Lancea, Schisandra chinensis, Oldenlandia diffusa, Adenophora stricta, Salvia miltiorrhiza | [16] |

Next-generation sequencing technologies have been employed to screen for candidate genes that may be responsible for biosynthesis of the flavones, and several structural genes including 6-hydroxylase, 8-O-methyltransferase, 7-O-glucuronosyltransferases have been suggested to be involved in their biosynthesis [69]. Yuan et al. [70, 71] also screened RNA-sequencing databases and found that several MYB genes may be responsible for regulation of production of its flavonoids.

Flavonoid metabolism

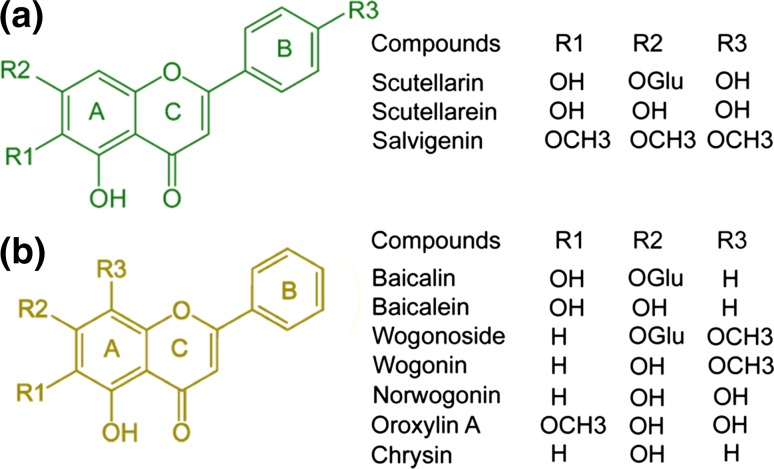

Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi produces various natural products including amino acids, essential oils, flavonoids, phenylethanoids, and sterols. More than 30 types of flavones can be found in its roots (Fig. 3), including baicalin, baicalein, chrysin, oroxylin A, oroxylin A 7-O-glucuronide, wogonin and wogonoside [72, 73]. Baicalin, baicalein, wogonin, and wogonoside are the major bioactive compounds extracted from S. baicalensis Georgi [74–76].

Fig. 3.

(Color online) Major flavones in Scutellaria baicalensis. a Flavones produced from naringenin. b Root-specific 4′-deoxyflavones, originating from pinocembrin

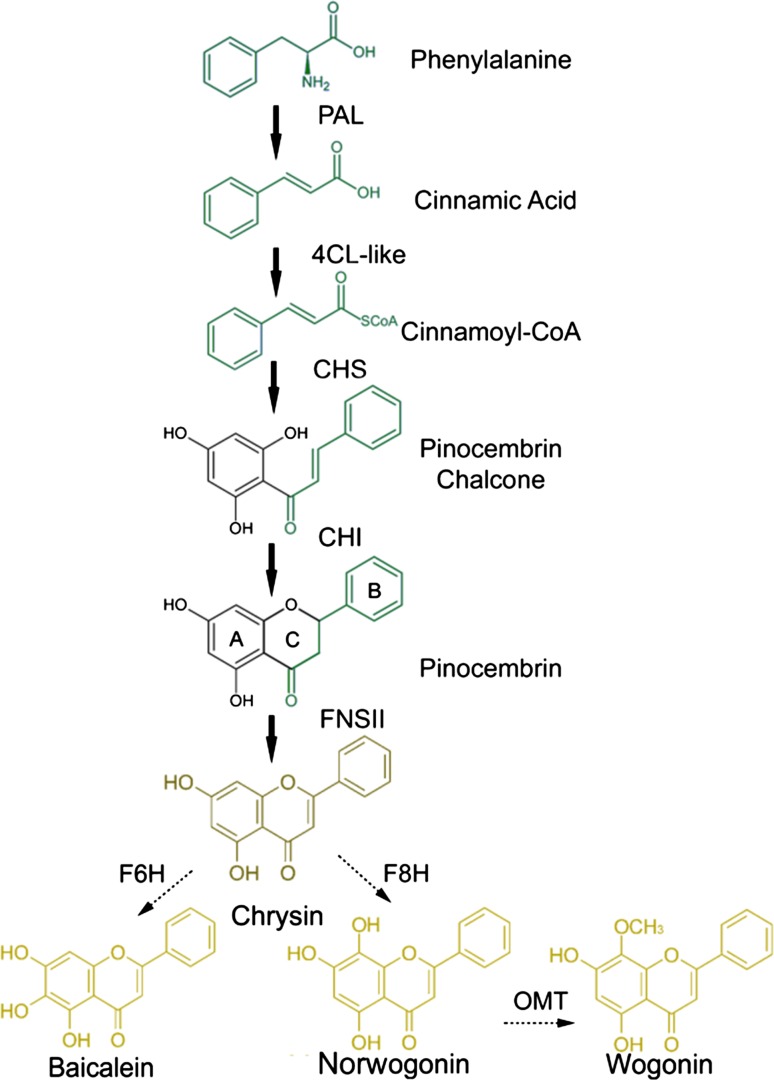

Flavones are present in aerial tissues of many flowering plants, with roles in co-pigmentation of flowers (they make anthoyanin pigments appear bluer) and in protection against UV irradiation [77, 78]. Flavones are synthesized by the flavonoid pathway, which is part of phenylpropanoid metabolism [79, 80]. Naringenin is a central intermediate in normal flavone biosynthesis [81] exemplified by the production of the flavones, scutellarin and scutellarein, derived from naringenin in the aerial parts (leaves and flowers) of Scutellaria baicalensis. Scutellarein and scutellarin are synthesised from phenylalanine by general phenyl propanoid metabolism; phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL), cinnamoyl 4 hydroxylase (C4H) and p-coumaroyl CoA ligase (4CL) followed by chalcone synthase (CHS) and chalcone isomerase (CHI) to form naringenin [82]. A flavone synthase (FNSII-1) then oxidises naringenin to form apigenin, which may be further hydroxylated, methylated and glycosylated to form scutellarein and scutellarin (Fig. 3a). Scutellaria roots however accumulate large amounts of specialized root-specific flavones (RSFs), lacking a 4′-OH group on their B-rings (Fig. 3b) [83]. These RSFs, which include baicalein and wogonin, and their glycosides, are not synthesized from naringenin, but by an alternative pathway where cinnamic-acid is recruited by a specially-evolved cimmamoyl-CoA ligase (SbCLL-7) to form cinnamoyl CoA which is then condensed with malonyl CoA by a specialised isoform of chalcone synthase (SbCHS-2) to form a chalcone, which is then isomerized by the same chalcone isomerase (CHI) that acts in scutellarin biosynthesis, to form pinocembrin, a flavanone without a 4′-OH group. Pinocembrin is converted by a specialised isoform of flavone synthase (FNSII-2), to form chrysin, which serves as the founding 4′ deoxyflavone which may be decorated further by 6/8-flavone hydroxylases, 8-O-methyl-transferases and glycosyltransferases to produce the different RSFs produced in the roots of S. baicalensis [64, 84] (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

(Color online) The proposed biosynthetic pathway for production of root-specific flavones of Scutellaria

The evolution of this specialised pathway for 4′ deoxyflavone biosynthesis occurred relatively recently, following the divergence of the Laminaceae [64] and may have been facilitated by the recruitment of a CoA ligase activity from a gene encoding an enzyme of fatty acid metabolism, that is specific for cinnamate. Effective competition for cinnamate in the face of high level expression of C4H may have paved the way for effective production of 4′- deoxyflavones in roots of S. baicalensis. Production of 4′- deoxyRSFs in roots is induced by methyl jasmonate treatment, suggesting that RSFs are made as part of a defence mechanism or for plant–microbe signalling [85, 86]. Understanding the regulation of this newly-evolved pathway may facilitate engineering of biosynthesis of these important bioactive metabolites. Their roles in defence in Scutellaria may also underpin some of their uses in traditional medicine, for example as anti-microbials.

The bioactive compounds baicalein, wogonin and their glysosides can be found in many species from the genus Scutellaria other than S. baicalensis [87]. As in traditional Chinese medicine, the roots of S. amoena and S.likiangensis have been used commonly as alternatives to S. baicalensis. To date, 4′-deoxyflavones have been found only in Oroxylum indicum vent [88] and Plantago major L. outside the genus Scutellaria but in the order Lamiales [89]. 4′-Deoxyflavones have also been reported in Anodendron affine and Cephalocereus senilis outside the order Lamiales [90, 91]. The evolution of metabolic pathways determining the taxa-specific distribution of these 4′-deoxyflavones is fascinating, and we suspect that convergent evolution has most likely influenced the development of metabolic pathways responsible for producing these specialised bioactive flavones in widely diverged plant species [92, 93].

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by CAS/JIC and Centre of Excellence for Plant and Microbial Sciences (CEPAMS) joint foundation. QZ and CM were supported by the Institute Strategic Program Understanding and Exploiting Plant and Microbial Secondary Metabolism (BB/J004596/1) from the BBSRC to JIC. QZ and XYC were also supported by the Special Fund for Shanghai Landscaping Administration Bureau Program (F132424, F112418 and G152421).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

SPECIAL TOPIC: Plant Second Metabolites for Human Health

References

- 1.Shang XF, He XR, He XY, et al. The genus Scutellaria an ethnopharmacological and phytochemical review. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010;128:279–313. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bocho áková H, et al. Main flavonoids in the root of Scutellaria baicalensis cultivated in Europe and their comparative antiradical properties. Phytotherapy Res. 2003;17:640–644. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jian H, Min Y, Man X, et al. Characterization of flavonoids in the traditional Chinese herbal medicine-Huang Qin by liquid chromatography coupled with electrospray ionization mass spectrometery. J Chromatogr B. 2007;848:355–362. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.10.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li S (1593 and republished in 2012). In: Compendium of materia medica (Bencao Gangmu). Huaxia Press, pp 543–546 (In Chinese)

- 5.Xu S (Around 200 AD and republished in 1978) Shuowen Jiezi (Explaining graphs and analyzing characters). Zhonghua Book Company, p 19 (In Chinese)

- 6.Ma JX (2013) Explanatory notes to Shennong Bencaojing People’s Medical Publising House, Beijing, 3:140

- 7.Huang ZH, Xu ZQ. Single huang-qin for treatment of bacterial pneumonia. Shizhen Tradit Med Res. 1992;3:106–107. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chu WM. Single Huang-qin was used for treatment of cold during pregnancy. Nei Mong J Tradit Chin Med. 2010;29:15. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang Z (Around 200 AD and republished in 1974). In: Shanghan Lun (On cold damage). People’s Medical Publishing House, Beijing, p 27

- 10.Xue TH, Roy R. Studying traditional Chinese medicine. Science. 2003;300:740–741. doi: 10.1126/science.300.5620.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wen J. Sho-saiko-to, a clinically documented herbal preperation for treating chronic liver disease. HerbalGram. 2007;59:34–43. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamamoto H, Miki S, Deguchi H. Five year follow up study of Sho-saiko-to (Xiao-Chai-Hu-Tang) administration in patients with chronic hepatitis. J Nissei Hosp. 1994;23:144–149. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gibo Y, Nakamura Y, Takahashi N. Clinical study of Sho saiko to therapy for Japanese patients with chronic hepatitis C. Prog Med. 1994;14:217–219. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pan MQ, Li YH, Liu JA, Tan YX. Reports for 80 patients with bronchial lung squamous carcinoma (Mid or Late Stage) treated Lung FuFang and chemotherapy. J Tradit Chin Med Pharm. 1990;5:19–21. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pan MQ, Li YH, Jiang YL. Clinical observation of old people NSCLC (mid or late stage) treated by Lung Fu Fang combined with chemotherapy. Shanxi Tradit Chin Med. 2000;31:389–390. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duan X, Jia CF, Duan M. Treatmenf of non-small-cell lung cancer by FuZheng anti-cancer prescription combined with chemotherapy. Shanxi Tradit Chin Med. 2014;35:311–312. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scheck AC, Perry K, Hank NC, et al. Anticancer activity of extracts derived from the mature roots of Scutellaria baicalensis on human malignant brain tumor cells. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2006;6:27. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-6-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ye F, Jiang SQ, Volshonok H, et al. Molecular mechanism of anti-prostate cancer activity of Scutellaria baicalensis extract. Nutr Cancer. 2007;57:100–110. doi: 10.1080/01635580701268352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang DY, Wu J, Ye F, et al. Inhibition of cancer cell proliferation and prostaglandin E2 synthesis by Scutellaria baicalensis. Cancer Res. 2003;63:4037–4043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumagai T, Muller CI, Desmond JC, et al. Scutellaria baicalensis, a herbal medicine: anti-proliferative and apoptotic activity against acute lymphocytic leukemia, lymphoma and myeloma cell lines. Leuk Res. 2007;31:523–530. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2006.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gao J, Morgan WA, et al. The ethanol extract of Scutellaria baicalensis and the active compounds induce cell cycle arrest and apoptosis including upregulation of p53 and Bax in human lung cancer cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2011;254:221–228. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2011.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li-Weber M. New therapeutic aspects of flavones: the anticancer properties of Scutellaria and its main active constituents Wogonin, Baicalein and Baicalin. Cancer Treat Rev. 2009;35:57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wo D, Lamer-Zarawska E, Matkowski A. Antimutagenic and antiradical properties of flavones from the roots of Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi. Food. 2004;48:9–12. doi: 10.1002/food.200200230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chou CC, Pan SL, Teng CM, et al. Pharmacological evaluation of several major ingredients of Chinese herbal medicines in human hepatoma Hep3B cells. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2003;19:403–412. doi: 10.1016/S0928-0987(03)00144-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen Y, Hui H, Yang H, et al. Wogonoside induces cell cycle arrest and differentiation by affecting expression and subcellular localization of PLSCR1 in AML cells. Blood. 2013;121:3682–3691. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-11-466219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim DH, Kim HK, Park S, et al. Short-term feeding of baicalin inhibits age-associated NF-κB activation. Mech Ageing Dev. 2006;127:719–725. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krakauer T, Li BQ, Young HA. The flavonoid baicalin inhibits superantigen-induced inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. FEBS Lett. 2001;500:52–55. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(01)02584-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fox JT, Sakamuru S, Huang RL, et al. High-throughput genotoxicity assay identifies antioxidants as inducers of DNA damage response and cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:5423–5428. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114278109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shimizu I, Ma YR, Mizobuchi Y, et al. Effects of Sho-saiko-to, a Japanese herbal medicine, on hepatic fibrosis in rats. Hepatology. 1999;29:149–160. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohta Y, Nishida K, Sasaki E, et al. Comparative study of oral and parenteral administration of Sho-saiko-to (Xiao-Chaihu-Tang) extract on d-galactosamine-induced liver injury in rats. Am J Chin Med. 2012;25:333–342. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X97000378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang MD, Deng QG, Chen S, et al. Hepatoprotective mechanisms of Yan-gan-wan. Hepatol Res: Off J Jpn Soc Hepatol. 2005;32:202–212. doi: 10.1016/j.hepres.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang M, Chen K, Shih JC. Yang-Gan-Wan protects mice against experimental liver damage. Am J Chin Med. 2000;28:155–162. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X00000209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang MD, Chiang YM, Higashiyama R, et al. Rosmarinic acid and baicalin epigenetically derepress peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor gamma in hepatic stellate cells for their antifibrotic effect. Hepatology. 2012;55:1271–1281. doi: 10.1002/hep.24792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen HJ, Liang TM, Lee IJ, et al. Effect of Scutellaria baicalensis on hepatic stellate cells. Planta Med. 2014;80:817. [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Boer JG, Quiney B, Walter PB, et al. Protection against aflatoxin-B1-induced liver mutagenesis by Scutellaria baicalensis. Mutat Res. 2005;578:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim SJ, Moon YJ, Lee SM. Protective effects of baicalin against ischemia/reperfusion injury in rat liver. J Nat Prod. 2010;73:2003–2008. doi: 10.1021/np100389z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tan Y, Lv ZP, Bai XC, et al. Traditional Chinese medicine Bao Gan Ning increase phosphorylation of CREB in liver fibrosis in vivo and in vitro. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006;105:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pan TL, Wang PW, Leu YL, et al. Inhibitory effects of Scutellaria baicalensis extract on hepatic stellate cells through inducing G2/M cell cycle arrest and activating ERK-dependent apoptosis via Bax and caspase pathway (vol 139, pg 829, 2012) J Ethnopharmacol. 2015;168:381. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shan B, Cai YZ, Brooks JD, et al. The in vitro antibacterial activity of dietary spice and medicinal herb extracts. Int J Food Microbiol. 2007;117:112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blaszczyk T, Krzyzanowska J, Lamer-Zarawska E. Screening for antimycotic properties of 56 traditional Chinese drugs. Phytotherapy Res: PTR. 2000;14(3):210–212. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1573(200005)14:3<210::AID-PTR591>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bruzewicz S, Malicki A, Oszmianski J, et al. Baicalin, added as the only preservative, improves the microbiological quality of homemade mayonnaise. Pak J Nutr. 2006;15:30–33. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang ZC, Wang BC, Yang XS. The synergistic activity of antibiotics combined with eight traditional Chinese medicines against two different strains of Staphylococcus aureus. Colloids and Surf B Biointerf. 2005;41:79–81. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2004.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guo Q, Zhao L, You Q, et al. Anti-hepatitis B virus activity of wogonin in vitro and in vivo. Antivir Res. 2007;74:16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tang ZM, Peng M, Zhan CJ. Screening 20 Chinese herbs often used for clearing heat and dissipating toxin with nude mice model of hepatitis C viral infection. Chin J Integr Tradit West Med. 2003;23:447–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kitamura K, Honda M, Yoshizaki H, et al. Baicalin, an inhibitor of HIV-1 production in vitro. Antivir Res. 1998;37:131–140. doi: 10.1016/S0166-3542(97)00069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li BQ, Fu T, Yao DY, et al. Flavonoid baicalin inhibits HIV-1 infection at the level of viral entry. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;276:534–538. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.De Clercq E. Current lead natural products for the chemotherapy of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Med Res Rev. 2000;20:323–349. doi: 10.1002/1098-1128(200009)20:5<323::AID-MED1>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhao J, Zhang Z, Chen H, et al. Synthesis of baicalin derivatives and evaluation of their anti-human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1) activity. Acta pharmaceutica Sinica. 1998;33:22–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lam TL, Lam ML, Au TK, et al. A comparison of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 protease inhibition activities by the aqueous and methanol extracts of Chinese medicinal herbs. Life Sci. 2000;67:2889–2896. doi: 10.1016/S0024-3205(00)00864-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ono K, Nakane H, Fukushima M, et al. Inhibition of reverse transcriptase activity by a flavonoid compound, 5,6,7-trihydroxyflavone. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;160:982–987. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(89)80097-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ahn HC, Lee SY, Kim JW, et al. Binding aspects of baicalein to HIV-1 integrase. Mol Cells. 2001;12:127–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu JA, Attele AS, Zhang L, et al. Anti-HIV activity of medicinal herbs: usage and potential development. Am J Chin Med. 2012;29:69–81. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X01000083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schinella GR, Tournier HA, Prieto JM. Antioxidant activity of anti-inflammatory plant extracts. Life Sci. 2002;70:1023–1033. doi: 10.1016/S0024-3205(01)01482-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gao Z, Huang K, Yang X. Free radical scavenging and antioxidant activities of flavonoids extracted from the radix of Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1472:643–650. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4165(99)00152-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang HH, Liao JF, Chen CF. Anticonvulsant effect of water extract of Scutellariae radix in mice. J Ethnopharmacol. 2000;73:185–190. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(00)00300-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gaire BP, Moon SK, Kim H. Scutellaria baicalensis in stroke management: nature’s blessing in traditional eastern medicine. Chin J Integr Med. 2014;20:712–720. doi: 10.1007/s11655-014-1347-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shang Y, Cheng J, Qi J, et al. Scutellaria flavonoid reduced memory dysfunction and neuronal injury caused by permanent global ischemia in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2005;82(1):67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2005.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang Y, Butelli E, Alseekh S, et al. Multi-level engineering facilitates the production of phenylpropanoid compounds in tomato. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8635. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang Y, Butelli E, Martin C. Engineering anthocyanin biosynthesis in plants. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2014;19:81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2014.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tiwari RK, Trivedi M, Guang ZC. Agrobacterium rhizogenes mediated transformation of Scutellaria baicalensis and production of flavonoids in hairy roots. Biol Plant. 2008;52:26–35. doi: 10.1007/s10535-008-0004-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Joshee N, Parajuli P, Medina-Bolivar F, et al. Scutellaria biotechnology: achievements and future prospects. Bull Univ Agric Sci Vet. 2010;1:1843–5394. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nishikawa K, Ishimaru K. Flavonoids in root cultures of Scutellaria baicalensis. J Plant Physiol. 1997;151(5):633–636. doi: 10.1016/S0176-1617(97)80241-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Park NI, Xu H, Li XH. Enhancement of flavone levels through overexpression of chalcone isomerase in hairy root cultures of Scutellaria baicalensis. Funct Integr Genomics. 2011;11:491–496. doi: 10.1007/s10142-011-0229-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhao Q, Zhang Y, Wang G, et al. A specialized flavone biosynthetic pathway has evolved in the medicinal plant, Scutellaria baicalensis. Sci Adv. 2016;2:e1501780. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1501780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kuzovkina IN, Guseva AV, Alterman IE, Karnachuk RA. Flavonoid production in transformed Scutellaria baicalensis roots and ways of its regulation. Russ J Plant Physiol. 2001;48:448–452. doi: 10.1023/A:1016739010716. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kuzovkina IN, Guseva AV, Kovacs D, Szoke E, Vdovitchenko MY. Flavones in genetically transformed Scutellaria baicalensis roots and induction of their synthesis by elicitation with methyl jasmonate. Russ J Plant Physiol. 2005;52:77–82. doi: 10.1007/s11183-005-0012-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Howie JA, Avendano S, Tolkamp BJ. Flavonoid production in transformed root cultures of Scutellaria baicalensis. J Plant Physiol. 2000;156:121–125. doi: 10.1016/S0176-1617(00)80282-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Park NI, Xu H, Li X, et al. Overexpression of phenylalanine ammonia-lyase improves flavones production in transgenic hairy root cultures of Scutellaria baicalensis. Process Biochem. 2012;47:2575–2580. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2012.09.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Liu J, Hou J, Jiang C, et al. Deep Sequencing of the Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi transcriptome reveals flavonoid biosynthetic profiling and organ-specific gene expression. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0136397. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Qi L, Jian Y, Yuan Y, Huang L, Ping C. Overexpression of two R2R3-MYB genes from Scutellaria baicalensis induces phenylpropanoid accumulation and enhances oxidative stress resistance in transgenic tobacco. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2015;94:235–243. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2015.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yuan Y, Qi L, Yang J, et al. A Scutellaria baicalensis R2R3-MYB gene, SbMYB8, regulates flavonoid biosynthesis and improves drought stress tolerance in transgenic tobacco. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2014;120:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li HB, Jiang Y, Chen F. Separation methods used for Scutellaria baicalensis active components. J Chromatogr B: Anal Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2005;812:277–290. doi: 10.1016/S1570-0232(04)00545-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yu Z, Hirotani M, Yoshikawa T, et al. Flavonoids and phenylethanoids from hairy root cultures of Scutellaria baicalensis. Solid State Nucl Magn Reson. 1998;13:488–492. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Makino T, Hishida A, Goda Y, Mizukami H. Comparison of the major flavonoid content of S. baicalensis, S. lateriflora, and their commercial products. J Nat Med. 2008;62:294–299. doi: 10.1007/s11418-008-0230-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Choi J, Conrad CC, Malakowsky CA, et al. Flavones from Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi attenuate apoptosis and protein oxidation in neuronal cell lines. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1571:201–210. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4165(02)00217-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dong HK, Su JJ, Son KH, et al. The ameliorating effect of oroxylin A on scopolamine-induced memory impairment in mice. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2007;87:536–546. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Williams CA, Grayer RJ. Anthocyanins and other flavonoids. Nat Prod Rep. 2004;21:539–573. doi: 10.1039/b311404j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Koes R, Verweij WF. Flavonoids: a colorful model for the regulation and evolution of biochemical pathways. Trends Plant Sci. 2005;10:236–242. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Noel JP, Austin MB, Bomati EK. Structure-function relationships in plant phenylpropanoid biosynthesis. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2005;8:249–253. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2005.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yang L, Yang C, Li C, et al. Recent advances in biosynthesis of bioactive compounds in traditional Chinese medicinal plants. Sci Bull. 2016;61:3–17. doi: 10.1007/s11434-015-0929-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Martens S, Mithofer A. Flavones and flavone synthases. Phytochemistry. 2005;66:2399–2407. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2005.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lepiniec L, Debeaujon I, Routaboul JM, et al. Genetics and biochemistry of seed flavonoids. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2006;57:405–430. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Islam MN, Downey F, Ng CKY. Comparative analysis of bioactive phytochemicals from Scutellaria baicalensis, Scutellaria lateriflora, Scutellaria racemosa, Scutellaria tomentosa and Scutellaria wrightii by LC-DAD-MS. Metabolomics. 2011;7:446–453. doi: 10.1007/s11306-010-0269-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hirotani M, Kuroda R, Suzuki H, et al. Cloning and expression of UDP-glucose: flavonoid 7- O -glucosyltransferase from hairy root cultures of Scutellaria baicalensis. Planta. 2000;210:1006–1013. doi: 10.1007/PL00008158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yang G, Guo LP, et al. Selectivity infection of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in medicinal plants. Chin J Inform Tradit Chin Med. 2012;19:53–55. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Guo HJ, Wang W, et al. Effects of host plants on growth and development of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in Rhizospere of Scutellaria baicalensis. J Henan Agric Sci. 2011;40:98–2439. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Parajuli P, Joshee N, Rimando AM, Mittall S, Yadav AK. In vitro antitumor mechanisms of various Scutellaria extracts and constituent flavonoids. Planta Med. 2009;75:41–48. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1088364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chen LJ, Games DE, Jones J. Isolation and identification of four flavonoid constituents from the seeds of Oroxylum indicum by high-speed counter-current chromatography. J Chromatogr A. 2003;988:95–105. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9673(02)01954-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Samuelsen AB. The traditional uses, chemical constituents and biological activities of Plantago major L. A review. J Ethnopharmacol. 2000;71:1–21. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(00)00212-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tai MC, Tsang SY, Chang LYF, et al. Therapeutic potential of wogonin: a naturally occurring flavonoid. CNS Drug Rev. 2005;11:141–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3458.2005.tb00266.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Liu Q, Markham KR, Pare PW, et al. Flavonoids from elicitor-treated cell-suspension cultures of Cephalocereus senilis. Phytochemistry. 1993;32:925–928. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(93)85230-O. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Pichersky E, Lewinsohn E. Convergent evolution in plant specialized metabolism. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2011;62:549–566. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042110-103814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Moghe G, Last RL. Something old, something new: conserved enzymes and the evolution of novelty in plant specialized metabolism. Plant Physiol. 2015;169:1512–1523. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.00994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]