Abstract

The vascular endothelium plays an essential role in the control of the blood flow. Pharmacological agents like quinone (menadione) at various doses modulate this process in a variety of ways. In this study, Q7, a 2-phenylamino-1,4-naphthoquinone derivative, significantly increased oxidative stress and induced vascular dysfunction at concentrations that were not cytotoxic to endothelial or vascular smooth muscle cells. Q7 reduced nitric oxide (NO) levels and endothelial vasodilation to acetylcholine in rat aorta. It also blunted the calcium release from intracellular stores by increasing the phenylephrine-induced vasoconstriction when CaCl2 was added to a calcium-free medium but did not affect the influx of calcium from extracellular space. Q7 increased the vasoconstriction to BaCl2 (10−3 M), an inward rectifying K+ channels blocker, and blocked the vasodilation to KCl (10−2 M) in aortic rings precontracted with BaCl2. This was recovered with sodium nitroprusside (10−8 M), a NO donor. In conclusion, Q7 induced vasoconstriction was through a modulation of cellular mechanisms involving calcium fluxes through K+ channels, and oxidative stress induced endothelium damage. These findings contribute to the characterization of new quinone derivatives with low cytotoxicity able to pharmacologically modulate vasodilation.

1. Introduction

A functional vascular endothelium could have major clinical implications in pathologies such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and cancer [1, 2]. Previous studies have shown that the treatment with quinone-related compounds (i.e., 1,4-naphthoquinone derivatives) can impair [3, 4] or improve vascular functions [5]. The underlying mechanism(s) of quinone on vascular functions are still not fully understood. For instance, the observed decreased relaxation and increased contraction of blood vessels induced by menadione was partly explained by inhibition of NO pathway via the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). The hypotension and vasorelaxation effects of naphthoquinone-oxime were suggested to be due to activation of soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC), K+ channels, and via NO pathway [6].

Quinones are widely distributed molecules in nature, and they are found as endogenous compounds of biological importance (i.e., coenzyme Q in mitochondrial electron chain; vitamin K2 in blood coagulation) in humans. Numerous therapeutic drugs, in particular antitumor compounds, are quinone-bearing molecules including anthracyclines (doxorubicin, mitoxanthrone, and daunarubicin), benzoquinones (mitomycin C, geldanamycin), orthonaphthoquinones like β-lapachone, and several synthetic compounds which are currently under clinical trials using 1,4-naphthoquinone as pharmacophore group [6–9]. They are reported to cause cytotoxic effects through varied mechanisms such as DNA intercalation, reductive alkylation of biomolecules, and ROS formation through a redox-cycling reaction [10–12]. Regarding this latter mechanism, quinone reduction by 1 or 2 electrons from NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase leads to a semiquinone free radical which is oxidized back to the former quinone in the presence of molecular oxygen, while oxygen is reduced to superoxide anion [13]. This redox-cycling leads to the formation of other ROS, such as hydrogen peroxide and hydroxyl radicals [14, 15]. Based on this redox-cycling property, several quinones have been used as therapeutic agents against several diseases and pathologies [16–18]. As such they induced cell death by either apoptosis or necrosis, inhibiting cancer cells growth [19–21]. They also activated a senescence program leading to cell cycle arrest [22, 23].

Our observations were that one arylamino-naphthoquinone derivative, namely, Q7 [2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)amino-1,4-naphthoquinone], was able to provoke a drop in ATP cell content and inhibit cancer cell proliferation [24]. This inhibition induced cancer cells senescence [10], reduction of DNA damage, and inhibition of in vivo tumor growth [11]. It also leads to an inhibition of in vivo tumor progression by triggering apoptosis, cell cycle arrest, suppression of HIF-1, and uncoupling glycolytic metabolism [25]. All these effects have been attributed to its ability to generate ROS through quinone redox-cycling. Meanwhile, it has been reported that some naphthoquinone derivatives are potent inhibitors of endothelium-dependent vasodilation via an inhibition of endothelial NOS, possibly by interacting with the reductase domain of the enzyme [4, 26]. Indeed, it has been reported that oxidative stress enhances vascular reactivity, most likely by increasing the formation of ROS and decreasing the availability of nitric oxide [27, 28].

Based on these facts and due to the critical role of vascular functions in different pathologies, we have explored new biological activities of Q7 as to be used beyond the context of cancer, especially as it interferes with oxidative stress and vascular function (reactivity and endothelium), an integral complex involved in the survival or death of these cancerous cells.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) were isolated by collagenase 0.25 mg/mL, Collagenase Type II from Clostridium histolyticum (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany) digestion from umbilical cords obtained at birth from pregnancies and cultured (37°C, 5% CO2) in 1% gelatin-coated petri dishes up to passage 2 in medium 199 (M199; Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) containing 5 mmol/L D-glucose, 10% new born bovine serum, 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 3.2 mmol/L L-glutamine, and 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin (primary culture medium). A7r5 cells, a vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) line originally derived from embryonic rat aorta, were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). They were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Invitrogen, NY, USA, Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 10% FBS and 2 × 10−3 M pyruvate. Prior to experiments, 80–90% confluent A7r5 cells were serum-starved.

2.2. MTS Reduction Assay

Briefly, cells (50–60% confluence) were seeded in 96-well plates. Cells were incubated at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2/95% air mixture. HUVECs and A7r5 vascular smooth cell line were incubated in the absence or in the presence of Q7 (10−7 M, 10−6 M, 10−5 M, and 10−4 M) for 48 h, and cytotoxicity was determined using the MTS [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium] reduction assay. Cell Titer 96® AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay, Promega, WI, USA. Cyclophosphamide (10−4 M) was used as negative control and 10−5 M epirubicin (anthracycline drug used for chemotherapy) as positive control. The MTS and Q7 were dissolved in vehicle (DMSO) at final concentration less than 0.1%. All the assays were performed in quintupled and in 3 independent experiments. The cytotoxicity was calculated in accordance with the formula: cytotoxicity (%) = (1 − (absorbance sample/absorbance control)) × 100. The absorbance of sample was determined in the absence (vehicle; control) or in the presence of Q7. The absorbance was measured with a microplate reader (Infinite 200 PRO; Tecan, Switzerland) at 490 nm.

2.3. Animals

Male and female Sprague–Dawley rats (4-5 weeks of age, 120–180 g) from the breeding colony at the Antofagasta University were used for this study. All rats were housed in a temperature-controlled, light-cycled (08:00–20:00 hours) room with ad libitum access to drinking water and standard rat chow (Champion, Santiago). The assays were conducted according to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication revised 2013), and the local animal research committee approved the experimental procedure used in the present study.

2.4. Isolation of Aortic Rings

Rats were sacrificed through cervical dislocation. The thoracic aorta was quickly excised and placed in cold (4°C) physiological Krebs-Ringer bicarbonate buffer (KRB) containing (×10−3 M) 4.2 KCl, 1.19 KH2PO4, 120 NaCl, 25 Na2HCO3, 1.2 MgSO4, 1.3 CaCl2, and 5 D-glucose (pH 7.4). Rings (3–5 mm and 2–4 mg) were prepared after connective tissue was cleaned out from the aorta, taking special care to avoid endothelial damage. Aortic rings were equilibrated for 40 min at 37°C by constant bubbling with 95% O2 and 5% CO2.

2.5. Vascular Reactivity Experiments

Aortic rings of native animals were incubated (30 min) and perfused acutely with Q7 (10−6 M and 10−5 M) in the organ bath. The aortic rings from the same animal were studied in duplicate, using different vasoactive substances (phenylephrine [PE], acetylcholine [ACh], sodium nitroprusside [SNP], KCl). The rings were mounted on two 25-gauge stainless steel wires; the lower one was attached to a stationary glass rod and the upper one was attached to an isometric transducer (Radnoti, Monrovia, California). The transducer was connected to a PowerLab 8/35 (Colorado Springs CO) for continuous recording of vascular tension using the LabChart 8 computer program (ADS Instruments).

After the equilibration period, the aortic rings were stabilized by 2 successive near-maximum contractions with KCl (6 × 10−2 M) for 10 min. The passive tension on aorta was 1.0 g, which was determined to be the resting tension for obtaining maximum active tension induced by 6 × 10−2 M KCl. Ten min after contraction with phenylephrine (PE; 10−6 M), cumulative concentrations of acetylcholine (ACh) were added to the medium (10−8 to 10−5 M). Similar protocols were repeated with SNP (10−8 to 10−6 M). To study the role of extracellular calcium, experiments were performed with a calcium-free KRB containing (×10−3 M) 1.0 EGTA, 4.2 KCl, 1.19 KH2PO4, 125 NaCl, 25 Na2HCO3, 1.2 MgSO4, and 5 D-glucose (pH 7.4). The aortic rings were preincubated in a KRB with calcium for 30 min; then the KRB was changed with KRB without calcium for 5 min before PE (10−6 M) was added. Five min after contraction with PE (10−6 M), cumulative concentrations of CaCl2 (0.1 to 1.0 × 10−3 M) were added to the medium. In other experiments the contraction was induced by 10−3 M BaCl2 for 10 min and then relaxed with 10−2 M KCl. BaCl2 is used because it increases vasoconstriction by blocking of inward rectifying K+ channels [29–31], thus depolarizing the plasma membrane.

2.6. Lipid Peroxidation

Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) were measured in rat aorta homogenates. Samples of homogenates (500 μL; 10 ± 1.4 mg protein/mL) were incubated with vehicle and Q7 (10−6–10−4 M) for 30 min and then centrifuged at 3000 ×g for 20 min at 4°C. A 100 μL aliquot of the supernatant was mixed with 200 μL of 10% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and 4% butylated hydroxytoluene. The mixture was then centrifuged and 140 μL of supernatant (in duplicate) was mixed with thiobarbituric acid (0.67%) and heated for 1 h at 95°C. After cooling to room temperature, 280 μL of butanol-pyridine (15 : 1) was added. After centrifugation (3000 ×g, 20 min) the absorbance was measured at 532 nm.

2.7. Nitrite/Nitrate Assay

The production of NO by a segment of the rat aorta (in native rats) was measured by nitrite accumulation using the Griess reaction method [32]. Aortic rings were incubated in KRB constantly bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 for 40 min at 37°C. KRB containing (×10−3 M) 4.2 KCl, 1.19 KH2PO4, 120 NaCl, 25 Na2HCO3, 1.2 MgSO4, 1.3 CaCl2, and 5 D-glucose (pH 7.4). Aortic rings were incubated at 37°C for 30 min with saline, ACh (10−5 M) or the combination of ACh (10−5 M) and Q7 (10−5 M) or ACh (10−5 M) plus Nw-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME; 10−4 M). At the end of incubation, samples were collected and nitrate reduction was carried out with Zn dust for 30 min at room temperature. Total nitrites in each sample were determined by the addition of 1% sulfanilamide, followed by 0.1% N-(1-naphthyl) ethylenediamine (NED) in 5% phosphoric acid. The absorbance was measured with a microplate reader (Infinite 200 PRO; Tecan, Switzerland) at 550 nm. Nitrite concentration was expressed as μM/mg tissue and calculated from a standard curve with sodium nitrite.

2.8. L-Citrulline Assay

NOS activity was determined by incubation of HUVECs with 10−4 M L-arginine and 9 × 10−6 Ci/mL L-[3H]arginine (30 minutes, 37°C) in the absence or presence of 10−4 M L-NAME (a NOS inhibitor). In addition, 10−5 M Q7 was used. HUVECs were incubated in HEPES buffer containing (×10−3 M) 50 HEPES, 100 NaCl, 5 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, and 1 MgCl2 (pH 7.4). The fraction of L-[3H]citrulline formation inhibited by L-NAME was considered NOS activity [33]. Digested cells (95% formic acid) were passed through an ion-exchange resin Dowex-50W 5 (50X8-200) and L-[3H]citrulline was determined in H2O eluate as described [34]. NOS activity was calculated by subtracting L-NAME-insensitive L-citrulline from the total L-citrulline.

2.9. Determination of Intracellular Calcium in Culture Cell

A7r5 cells were cultured in 35 mm culture dish for confocal microscopy (ibidi, Germany). The cells were washed with Krebs with calcium containing (×10−3 M) 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, and 5.6 glucose, pH 7.4. Then, they were loaded with 10−5 M Fluo-3-AM for 25 min at 37°C and then were again washed with Krebs without calcium containing (×10−3 M) 145 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES-Na, and 5.6 glucose, pH 7.4. In Krebs free-calcium 5 × 10−5 M BAPTA-AM was used. The cells were preincubated in Krebs without calcium for 5 min before PE (10−6 M) was added, and then 10−3 M of CaCl2 was added to the medium. The intensity of Ca2+ fluorescence was measured with a laser scanning confocal microscope (Leica TCS SP8, Concord, ON, Canada) and fluorescence was recorded every 5 seconds. Analysis involved determination of pixels assigned to each cell using Image J software. The average pixel value allocated to each cell was obtained with excitation at 506 nm and corrected for background.

2.10. Chemicals

The following drugs were used in this study: L-phenylephrine hydrochloride (PE; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Mo), acetylcholine chloride (ACh; Sigma-Aldrich, Munich, Germany), sodium nitroprusside (SNP; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), barium chloride dihydrate (BaCl2; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), sulfanilamide (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), N-(1-naphthyl)ethylenediamine (NED; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), tetramethoxypropane (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Mo), thiobarbituric acid (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), butylated hydroxytoluene (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), Nw-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and BAPTA-AM (Invitrogen, USA). Drugs were dissolved in distilled deionized water. The solutions in Krebs-Ringer bicarbonate (KRB) were freshly prepared before each experiment. Figure 1 shows chemical structure of 2-[(4-hydroxyphenyl)amino]-1,4-naphthoquinone (Q7; 265.07 g/mol); it was synthesized by amination of 1,4-naphthoquinone with 4-hydroxyphenylamine, under aerobic conditions, using CeCl3·7H2O as the Lewis acid catalyst as previously reported [35].

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of 2-[(4-hydroxyphenyl)amino]-1,4-naphthoquinone (Q7).

2.11. Statistical Analysis

Values are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean; n denotes the number of animals studied. One- or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was carried out to detect significant differences, followed by Bonferroni post-tests to compare all groups. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

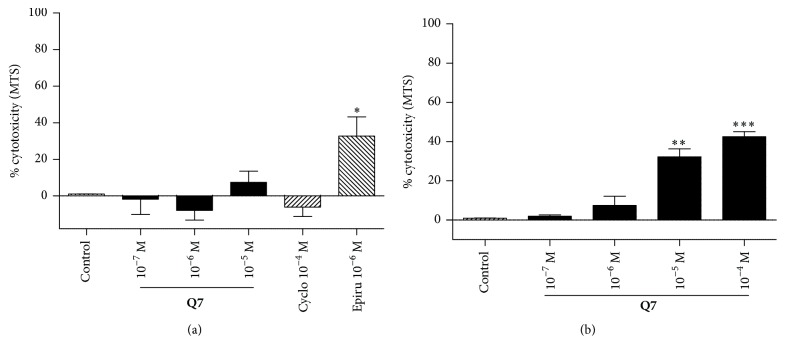

3.1. Cytotoxicity of Q7 on Vascular Endothelial Cell Line and Vascular Smooth Muscle

Because oxidative stress is associated with cell death, the effect of Q7 on the viability of HUVEC and the vascular smooth muscle cell line A7r5 was assessed (Figure 2). After 48 h of incubation, the cytotoxicity in presence of 10−5 M Q7 did not significantly increase in endothelial cells (1.00 ± 0.05% in control versus 7.39 ± 6.14% with 10−5 M Q7) and increased significantly in vascular smooth muscle cells (0.97 ± 0.03% in control versus 32.20 ± 4.04% with 10−5 M Q7; p < 0.01). As expected, no significant cytotoxicity was observed with the chemotherapy cyclophosphamide (10−4 M), which is activated only after metabolism in the liver and thus is inactive in cell culture.

Figure 2.

Q7 does not induce cell death. The results show that Q7 cytotoxicity was low or negligible on a vascular endothelial cell or vascular smooth muscle cell line, respectively. Q7 cytoxicity was determined by MTS assay. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) (a) and A7r5 vascular smooth cell line (b) were incubated in the absence or in the presence of Q7 (10−7 to 10−4 M) for 48 h. Cyclophosphamide (Cyclo; 10−4 M) was used as negative control and epirubicin (Epirub; 10−5 M) as positive control. The cells were seeded at 50% density. Data are the average ± SEM of 4 independent experiments; ∗ p < 0.05; ∗∗ p; ∗∗∗ p < 0.001 versus control.

3.2. Q7 Induces Oxidative Stress in Rat Aorta and Decreases Endothelial NO Production in Rat Aorta

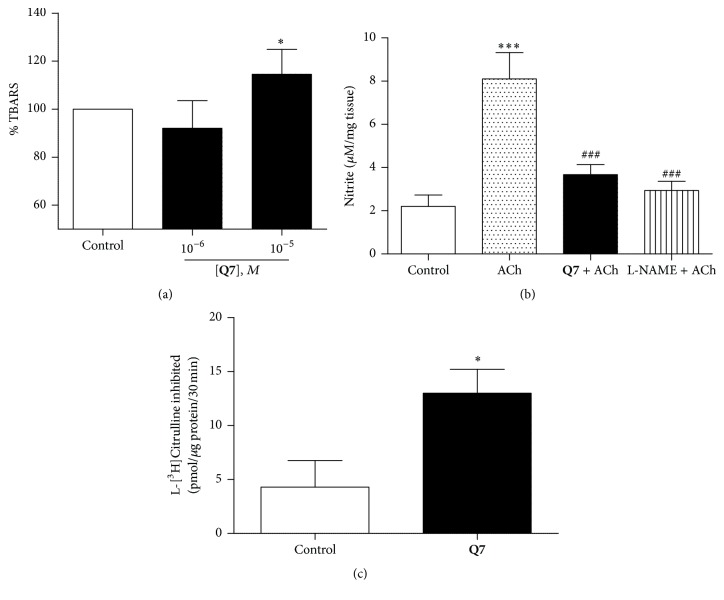

We conducted experiments to evaluate oxidative stress revealed by Q7-mediated lipid oxidation in rat aorta tissue. TBARS assay was used as an index of lipid peroxidation. As shown in Figure 3(a), Q7 (10−5 M) increased the formation of TBARS by 114 ± 5% as compared to control (vehicle).

Figure 3.

Q7 produces oxidation of lipids and decreases endothelial NO. Depicting oxidative stress revealed by Q7-mediated lipid oxidation and a change of endothelial NO release in rat aorta tissue. The rat aorta homogenate determination of TBARS in presence of Q7 (10−6 and 10−5 M) was measured as % with respect to control (a). Significant differences were found between 10−5 M Q7 versus control or 10−6 M of Q7 (∗ p < 0.05). The production of NO by a segment of the rat aorta was measured by the accumulation of nitrite using Griess reaction method (b): the aortic rings were incubated with vehicle (control), 10−5 M ACh, 10−5 M Q7 plus 10−5 M ACh, and 10−5 M ACh plus 10−4 M L-NAME. Data are the average ± SEM of 5 independent experiments. ∗∗∗ p < 0.001 versus control; ### p < 0.001 versus ACh; effect of Q7 on eNOS activity and production of endothelial NO (c). The production of NO was determined indirectly by the formation of L-citrulline in the reaction catalyzed by eNOS in HUVEC. The results are mean standard error of the mean. Asterisk indicates statistically significant differences compared to the control (∗ p < 0.05; n = 3).

To unravel the modulatory effects on mechanisms involved in vasodilation, NO formation in rat aorta was assessed by measuring the production of nitrites using the Griess reaction. The aortic rings were incubated with vehicle, ACh (10−5 M), and Q7 (10−5 M) + ACh (10−5 M) for 30 min. Figure 3(b) shows that the preincubation with Q7 significantly decreased the formation of endothelial NO (8.1 ± 1.2 nitrite μM/mg tissue with ACh versus 3.7 ± 0.5 nitrite μM/mg tissue with Q7 + ACh, p < 0.01). The preincubation with L-NAME also decreased significantly the production of nitrites (2.9 ± 0.4 nitrite μM/mg tissue with L-NAME + ACh, p < 0.01).

We measured eNOS activity in presence of Q7 by the formation of L-citrulline in the reaction catalyzed by eNOS in HUVEC (Figure 3(c)). The concentration of L-citrulline formed is directly proportional to the NO concentration formed and eNOS activity. We showed that Q7 (10−5 M) increased the concentration of L-citrulline in HUVEC (4.29 ± 2.46 pmol/μg protein control, 12.99 ± 2.22 pmol/μg protein with 10−5 M Q7; p < 0.05).

To test whether decreased or increased NO might have an effect on vasodilation, we tested the modulatory effect of Q7 on ACh-induced vasodilation and PE-induced vasoconstriction (Figures 4 and 5).

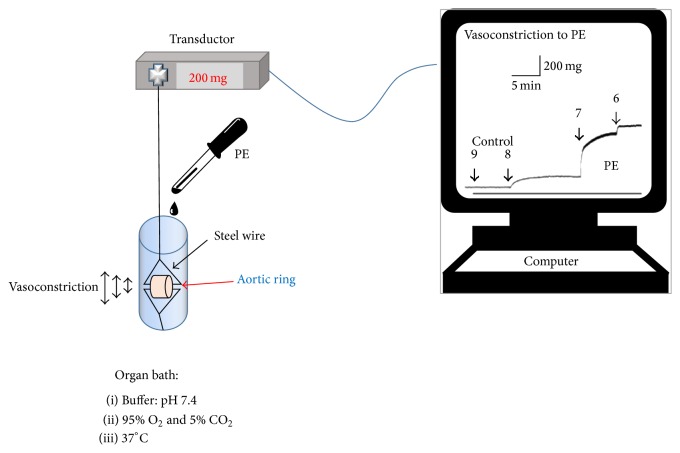

Figure 4.

Vascular reactivity experimental setup. Aortic ring was mounted on two steel wires; the upper one was attached to an isometric transducer. An equilibration period and stabilization with KCl were allowed, and the tissue was washed two times with fresh KRB. Then, we performed the protocol of the experiment; we added different concentrations of PE, which caused vasoconstriction of aortic ring. To finish, data were registered in the computer. The increase of the trace of the screen indicates vasoconstriction to PE, while the decrease of the trace indicates vasodilatation of the aortic ring.

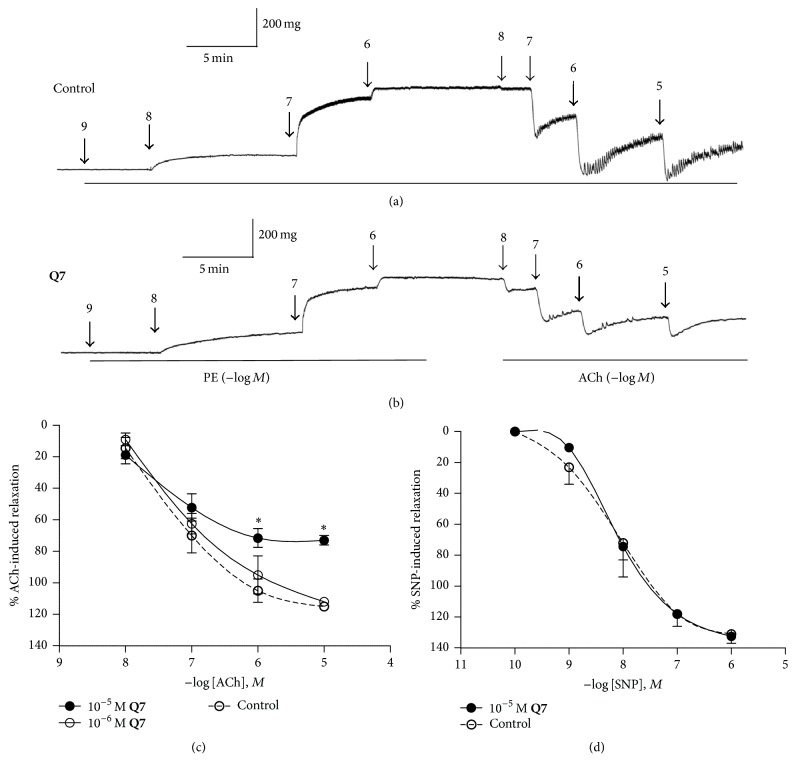

Figure 5.

Q7 impairs ACh-induced vasodilation in an NO-dependent mechanism. Original trace showing the time course of the concentration–response curves to PE (10−9–10−6 M) and ACh (10−8–10−5 M) in intact aortic rings of rats: control (a) and in the presence of 10−5 M Q7 for 30 min (b). After an equilibration period and before PE, the aortic rings were stabilized by two successive near-maximal contractions with 6 × 10−2 M KCl. ACh-response curves in endothelium-intact rat aorta in the presence or absence (control) of Q7 (10−6 M, 10−5 M) (c). Arteries were preconstricted with 10−6 M PE. SNP-response curves in rat aorta in the presence or absence (control) of 10−5 M Q7 (d). Data are the average ± SEM of 4-5 independent experiments. ∗ p < 0.05 versus control.

3.3. Endothelial Vasodilation of Rat Aortic Rings Induced by ACh Is Impaired by Q7

To confirm that Q7 impairs endothelial dependent vasodilation via a NO pathway, further experiments were conducted in PE (10−6 M) precontracted aortas and doses of either ACh (10−8–10−5 M; Figures 5(a)–5(c)) or SNP (10−10–10−6 M; Figure 5(d)) were increased. As shown in Figures 5(b) and 5(c), preincubation for 30 min with Q7 (10−5 M) results in a significant decrease of ACh-mediated vasodilation of intact aortic rings: 115 ± 2% control versus 73 ± 3% with 10−5 M Q7 (10−5 M ACh; p < 0.05). This finding suggests that Q7 decreases the endothelial nitric oxide, ACh-induced, which agrees with decreased production of nitrites observed in previous experiments. Nevertheless, by applying the same experimental protocol and using a NO-donor compound, namely, SNP, a vasodilation of 100% was observed even in the presence of 10−5 M Q7 (Figure 5(d)). This indicates that the reduction of vasodilation can be overcome by NO; therefore, Q7 only impairs the endothelial response and there was no response of vascular smooth muscle.

In the next experiments, we studied if the decreased vasodilation should be accompanied by reduced intracellular calcium in precontracted aorta with PE.

3.4. Effect of Q7 on the Calcium Homeostasis in A7r5 Cells

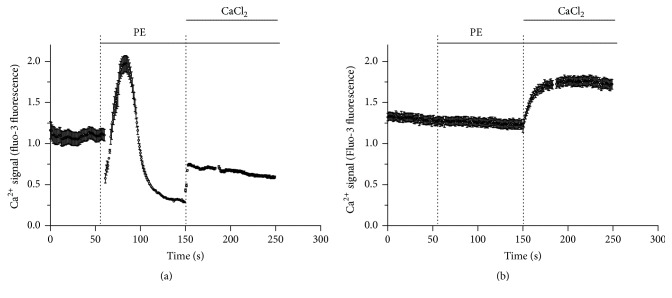

To investigate if the contractile response of PE in presence of Q7 could be modulated by calcium released from intracellular stores, further experiments were conducted with PE in A7r5 cells in a calcium-free medium. Figure 6 shows that this situation, 10−5 M Q7, drastically blunted the release of calcium from intracellular stores in response to 10−6 M PE, but it however, did not blunt the increase of intracellular calcium when 1 mM CaCl2 was added to extracellular space.

Figure 6.

Quinone effect on intracellular Ca2+ levels in A7r5 cells. Q7 blunted the release of calcium from intracellular stores, but not the influx of calcium from extracellular space. Representative plots of relative changes in Ca2+ signal (fluo-3 fluorescence) over time on A7r5 cells in calcium-free medium with 10−6 M phenylephrine (PE) in absence of Q7 (control) (a) or presence of 10−5 M Q7 (b). Data are the average ± SEM (n = 3).

In order to gain insight into potential role of Q7 on vascular reactivity, we repeat a similar protocol in response to PE in aortic rings.

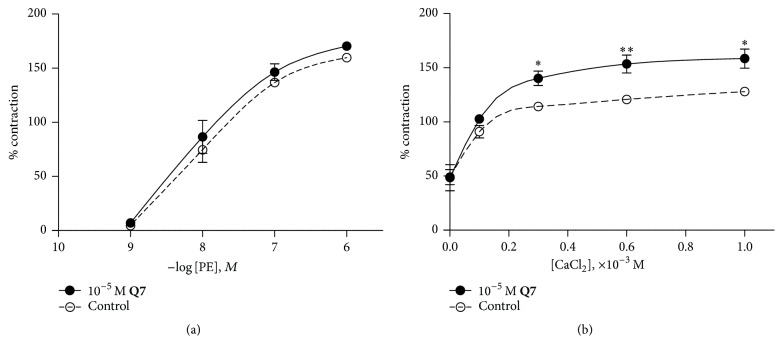

3.5. Effect of Q7 on Aortic Rings Vasoconstriction Induced by PE

The effect of Q7 preincubation on the contractility response to PE was explored. As shown in Figure 7(a), Q7 at 10−5 M did not potentiate the contractile effect induced by PE when tested in the presence of normal KRB (1.3 × 10−3 M extracellular calcium). However, Q7 enhanced the contractile response to PE when calcium was added to extracellular space in a calcium-free medium. No change in the basal tension of aortic rings was observed by Q7 per se. We investigated if the contraction induced by PE in presence of Q7 could be modulated by calcium inflow from the extracellular space. Thus, we added increasing concentrations of CaCl2 to a calcium-free medium. Figure 7(b) shows that in the presence of 10−3 M CaCl2, Q7 (10−5 M) significantly increased the contractile response to PE (10−6 M) from 128 ± 1% control to 158 ± 9% (p < 0.05). Percentages were determined with respect to submaximal contraction with 6 × 10−2 M KCl. This data suggests that Q7 increased calcium influx thus enhancing PE-induced vasoconstriction.

Figure 7.

Q7 increases PE-dependent vasoconstriction in a Ca2+-dependent manner. PE-response curves in endothelium-intact rat aorta in the presence or absence (control) of 10−5 M Q7 (a). The vascular tissue was preincubated in a KRB buffer without calcium for 10 min before 10−6 M PE was added; and then, the CaCl2 (0.1, 0.3, 0.6, and 1.0 × 10−3 M) was added to the bath (b). Data are the average ± SEM of 4-5 independent experiments. ∗ p < 0.05 and ∗∗ p < 0.01 versus control.

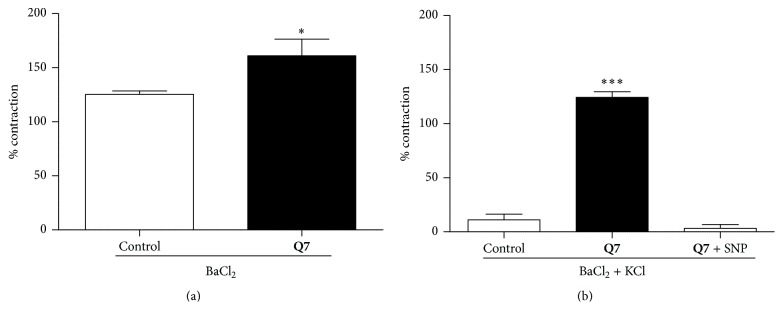

3.6. Role of Potassium Channels in the Vascular Response to Q7 in Rat Aortic Rings

The putative role of potassium channels on vascular contractile response was further studied. For this purpose, BaCl2 was used, as it increases vasoconstriction by blocking voltage-dependent Ca2+-sensitive K+ channels. Figure 8(a) shows that preincubation with Q7 significantly enhanced the contractile response to BaCl2 (10−3 M): 125 ± 3% control versus 161 ± 15% with 10−5 M Q7 (p < 0.05). Interestingly, low concentrations of KCl caused repolarization and decreased the vasoconstriction, but, in the presence of Q7, 10−2 M KCl did not decrease the vasoconstriction provoked by BaCl2. Only when a NO donor (10−8 M SNP) was added to the preparation, the aortic rings were able to recover 100% of its vasodilation, reaching values similar to control conditions (Figure 8(b)). These data suggest that potassium channels are required for the modulatory effect of Q7 on vascular contractile response and in consequence, the compound might affect the membrane potential.

Figure 8.

Acute effect of Q7 on potassium channels in rat aorta. Q7 significantly decreases the vascular contractile response involved potassium channels. The contraction with 10−3 M BaCl2 (a) and effect of 10−2 M KCl (b) in rat aorta precontracted with 10−3 M BaCl2 are shown. Open bar (control, vehicle), black bar (10−5 M Q7), and striped bar (10−5 M Q7 + 10−8 M SNP). Percentages of contraction with BaCl2 were determined with respect to submaximal contraction with 6 × 10−2 M KCl (a), and the percentages of contraction in presence of 10−2 M KCl were determined with respect to maximal contraction with 10−3 M BaCl2 (b). Data are the average ± SEM of 4-5 independent experiments. ∗ p < 0.05 and ∗∗∗ p < 0.001 versus control.

4. Discussion

The modulation of blood flow through the vascular endothelium influences the progression of several pathologies [36, 37]. Although studies have shown that quinone related compounds can impair vasodilation by endothelial dysfunction [3, 4, 38], the effect of quinones on endothelial function at low concentrations is not well characterized.

We found that noncytotoxic doses of Q7 induces oxidative stress and reduces the formation of endothelial NO in rat aorta, thus decreasing endothelial NO-dependent vasodilation. Our findings are consistent with a probable mechanism in which oxidative stress and decrease of NO may partially block potassium channels, thus depolarizing the cell membrane leading in consequence to the opening of calcium channels, increased calcium influx, and thus increasing calcium-dependent vasoconstriction.

Herein, we show that Q7 cytotoxicity after 48 h on vascular endothelial cell was negligible and on vascular smooth muscle cell was low. Considering that the incubation time in experiments conducted to determine vascular reactivity and oxidative stress in rat aortic rings lasted 30 min, it appears unlikely that such effects are the consequence of Q7 cytotoxicity.

In the present study, we observed that Q7 significantly increased lipid peroxidation in rat aorta homogenates, as shown by the enhanced TBARS formation. This finding was attributed to the capacity of Q7 to produce oxidative stress by increasing of ROS. In previous studies, we showed that TBARS increased in calf-thymus DNA treated with Q7 or juglone [39]. Free radicals can attack DNA at C4 of deoxyribose generating products as propenal, which react with 2-thiobarbituric acid and produce the TBARS formation [40]. In both T24 and MCF-7 cells, we found that Q7 provoked elevated levels of intracellular ROS [23, 25, 35, 39].

Oxidative stress produced by Q7 is mainly due to ROS generation through a redox-cycling mechanism as described for other quinones [12]. This might affect critically NO levels in the rat aorta. Q7 increased the formation of L-citrulline in HUVEC, compatible with increased NO generation and eNOS activity [41]. This paradoxical result can be explained in part because the ROS produced by redox-cycling of Q7 react rapidly with generated NO, leading to a reduction of its level [38]. Quinones (i.e., doxorubicin, menadione) increase the generation of ROS (anion superoxide) leading to scavenging of NO, in agreement with previously described results [42–44]. In fact, we now found that Q7 significantly reduced the ACh-mediated NO formation.

Accordingly, ACh-mediated endothelial vasodilation was significantly reduced by Q7, but it was recovered when a NO donor (SNP) was added into intact rat aorta preparations. Therefore, endothelial dysfunction caused by Q7 may be explained by a decrease in the bioavailability of endothelial NO.

Oxidative stress is associated with disruption of intracellular calcium homoeostasis [45]. In fact, Q7 blunted the release of calcium from intracellular stores in response to PE on vascular smooth muscle cell (A7r5 cells) in a free-calcium medium. Similar results we observed in cardiac fibroblasts preincubated with Q7 in a free-calcium medium in presence of angiotensin II (data not shown). These findings suggest that oxidative stress induced by Q7 blocked the release of intracellular calcium or caused calcium leakage from intracellular stores to extracellular space. This is in agreement with the inhibitory effect of quinone-related compounds (menadione) on the release of calcium from intracellular stores [46], by inhibition of sarcoplasmic calcium ATPase [47]. It is possible that the endoplasmic reticulum emptying of calcium by Q7 enhanced the contractile response to PE of aortic rings when calcium was provided extracellularly. We found that Q7 did not decrease the influx of calcium from extracellular space.

We have obtained preliminary data suggesting that Q7 may also inhibit potassium channels in neurons. Our results show an increase in action potential firing that is accompanied by increased input resistance (data no shown), an effect that could be mediated by blockade of hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide gated (HCN) channels, that carry the Ih current [48]. However, more experiments are needed to confirm the participation of different ion channels in this.

To study a putative role of potassium channels in NO-dependent vasodilation, we use BaCl2. Barium blocks inward rectifying potassium channels such as ATP-sensitive K+ channels at submillimolar concentrations [49, 50] and voltage-dependent Ca2+-sensitive K+ channels at millimolar concentrations [29, 30]. The result of the blockage of potassium channels by barium induced contraction in aortic rings. In the presence of Q7, the addition of KCl (10−2 M) was unable to provoke a total vasodilation in rat aorta preconstricted with BaCl2 (10−3 M), an effect which was however obtained at 100% by adding SNP (10−8 M). The increase of KCl over 2 × 10−2 M caused repolarization and vasodilation, because the membrane potential moves towards the new K+ equilibrium potential, and voltage-dependent Ca2+-sensitive K+ channels are again opened [29, 41, 51]. These findings may be explained by previous studies, showing that juglone (5-hydroxy-1,4-naphthoquinone) partially blocks voltage-dependent potassium channels, causing depolarization of the membrane [52].

These results agree with the idea that vasodilation induced by endothelial NO is due, at least in part, to a repolarization of the plasma membrane by opening voltage-dependent Ca2+-sensitive K+ channels [53–55] and closing of L-type Ca2+ channels [56], decreasing in this way the calcium influx [57, 58].

In conclusion, oxidative stress induced by Q7 decreases endothelial vasodilation, a process likely accompanied by decreased NO bioavailability and partial downstream blockade of potassium channels and membrane depolarization, followed by enhanced influx of calcium [59]. These findings could have interesting and potential clinical effects for a number of pathologies such as inflammatory disorders, diabetic blindness, age-related muscular degeneration, psoriasis, cardiovascular and autoimmune diseases, and cancer [60].

Acknowledgments

Financial support by the Universidad Arturo Prat (VRIIP0198-14 to Javier Palacios) is gratefully acknowledged. This research was funded in part by Comision Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnologia (CONICYT), Chile, FONDECYT 1100376 to Jaime A. Valderrama, FONDECYT 1140970 to Gareth I. Owen, FONDECYT 1150377 to Luis Sobrevia, FONDECYT 11150083 to Fabián Pardo, BMRC 13CTI-21526-P6, CORFO 13IDL3, CONICYT/FONDAP 15130011, and IMII P09/016-F. The authors thank Dr. Chukwuemeka R. Nwokocha (Department of Basic Medical Sciences Physiology Section, Faculty of Medical Sciences, University of the West Indies, Jamaica) for his helpful comments on the manuscript. The authors are grateful to Dr. Patricia Siqués and Dr. Julio Brito from Institute of Health Studies, Universidad Arturo Prat, for assistance with animals care.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Sato Y. Novel link between inhibition of angiogenesis and tolerance to vascular stress. Journal of Atherosclerosis and Thrombosis. 2015;22(4):327–334. doi: 10.5551/jat.28902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goveia J., Stapor P., Carmeliet P. Principles of targeting endothelial cell metabolism to treat angiogenesis and endothelial cell dysfunction in disease. EMBO Molecular Medicine. 2014;6(9):1105–1120. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201404156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee J. Y., Lee M. Y., Chung S. M., Chung J. H. Menadione-induced vascular endothelial dysfunction and its possible significance. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 1999;161(2):140–145. doi: 10.1006/taap.1999.8795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ryu C.-K., Shin K.-H., Seo J.-H., Kim H.-J. 6-Arylamino-5,8-quinazolinediones as potent inhibitors of endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2002;37(1):77–82. doi: 10.1016/s0223-5234(01)01290-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dantas B. P. V., Ribeiro T. P., Assis V. L., et al. Vasorelaxation induced by a new naphthoquinone-oxime is mediated by NO-sGC-cGMP pathway. Molecules. 2014;19(7):9773–9785. doi: 10.3390/molecules19079773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kovacic P., Somanathan R. Recent developments in the mechanism of anticancer agents based on electron transfer, reactive oxygen species and oxidative stress. Anti-Cancer Agents in Medicinal Chemistry. 2011;11(7):658–668. doi: 10.2174/187152011796817691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tandon V. K., Kumar S. Recent development on naphthoquinone derivatives and their therapeutic applications as anticancer agents. Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Patents. 2013;23(9):1087–1108. doi: 10.1517/13543776.2013.798303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Castro S. L., Emery F. S., da Silva Júnior E. N. Synthesis of quinoidal molecules: strategies towards bioactive compounds with an emphasis on lapachones. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2013;69:678–700. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.07.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malik E. M., Müller C. E. Anthraquinones as pharmacological tools and drugs. Medicinal Research Reviews. 2016;36(4):705–748. doi: 10.1002/med.21391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Brien P. J. Molecular mechanisms of quinone cytotoxicity. Chemico-Biological Interactions. 1991;80(1):1–41. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(91)90029-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bolton J. L., Trush M. A., Penning T. M., Dryhurst G., Monks T. J. Role of quinones in toxicology. Chemical Research in Toxicology. 2000;13(3):135–160. doi: 10.1021/tx9902082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shang Y., Chen C., Li Y., Zhao J., Zhu T. Hydroxyl radical generation mechanism during the redox cycling process of 1,4-naphthoquinone. Environmental Science & Technology. 2012;46(5):2935–2942. doi: 10.1021/es203032v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilson I., Wardman P., Lin T.-S., Sartorelli A. C. One-electron reduction of 2- and 6-methyl-1,4-naphthoquinone bioreductive alkylating agents. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 1986;29(8):1381–1384. doi: 10.1021/jm00158a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sato S., Iwaizumi M., Handa K., Tamura Y. Electron spin resonance study on the mode of generation of free radicals of daunomycin, adriamycin, and carboquone in NAD(P)H-microsome system. Gann. 1977;68(5):603–608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bachur N. R., Gordon S. L., Gee M. V. A general mechanism for microsomal activation of quinone anticancer agents to free radicals. Cancer Research. 1978;38(6):1745–1750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prescott B. Potential antimalarial agents. Derivatives of 2-chloro-1,4-naphthoquinone. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 1968;12(1):181–182. doi: 10.1021/jm00301a053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oeriu I. Relation between the chemical structure and antitubercular activity of various alpha-napththoquinone derivatives. Biokhimiia. 1963;28:380–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hodnett E. M., Wongwiechintana C., Dunn W. J., III, Marrs P. Substituted 1,4-naphthoquinones vs. the ascitic sarcoma 180 of mice. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 1983;26(4):570–574. doi: 10.1021/jm00358a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park E. J., Min K.-J., Lee T.-J., Yoo Y. H., Kim Y.-S., Kwon T. K. β-Lapachone induces programmed necrosis through the RIP1-PARP-AIF-dependent pathway in human hepatocellular carcinoma SK-Hep1 cells. Cell Death and Disease. 2014;5(5) doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.202.e1231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Calderon P. B., Cadrobbi J., Marques C., et al. Potential therapeutic application of the association of vitamins C and K3 in cancer treatment. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2002;9(24):2271–2285. doi: 10.2174/0929867023368674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Awasthi B. P., Kathuria M., Pant G., Kumari N., Mitra K. Plumbagin, a plant-derived naphthoquinone metabolite induces mitochondria mediated apoptosis-like cell death in Leishmania donovani: an ultrastructural and physiological study. Apoptosis. 2016;21(8):941–953. doi: 10.1007/s10495-016-1259-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim S.-J., Kim J. M., Shim S. H., Chang H. I. Shikonin induces cell cycle arrest in human gastric cancer (AGS) by early growth response 1 (Egr1)-mediated p21 gene expression. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2014;151(3):1064–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.11.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Felipe K. B., Benites J., Glorieux C., et al. Antiproliferative effects of phenylaminonaphthoquinones are increased by ascorbate and associated with the appearance of a senescent phenotype in human bladder cancer cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2013;433(4):573–578. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Silver R. F., Holmes H. L. Synthesis of some 1,4-naphthoquinones and reactions relating to their use in the study of bacterial growth inhibition. Canadian Journal of Chemistry. 1968;46(11):1859–1864. doi: 10.1139/v68-309. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ourique F., Kviecinski M. R., Zirbel G., et al. In vivo inhibition of tumor progression by 5 hydroxy-1,4-naphthoquinone (juglone) and 2-(4-hydroxyanilino)-1,4-naphthoquinone (Q7) in combination with ascorbate. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2016;477(4):640–646. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.06.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee J.-A., Jung S.-H., Bae M. K., et al. Pharmacological effects of novel quinone compounds, 6-(fluorinated- phenyl)amino-5,8-quinolinediones, on inhibition of drug-induced relaxation of rat aorta and their putative action mechanism. General Pharmacology. 2000;34(1):33–42. doi: 10.1016/S0306-3623(00)00044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Montezano A. C., Touyz R. M. Reactive oxygen species, vascular noxs, and hypertension: focus on translational and clinical research. Antioxidants and Redox Signaling. 2014;20(1):164–182. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marques V. B., Nascimento T. B., Ribeiro R. F., et al. Chronic iron overload in rats increases vascular reactivity by increasing oxidative stress and reducing nitric oxide bioavailability. Life Sciences. 2015;143:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2015.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang Y. BaCl2- and 4-aminopyridine-evoked phasic contractions in the rat vas deferens. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1995;115(5):845–851. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb15010.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rudy B. Diversity and ubiquity of K channels. Neuroscience. 1988;25(3):729–749. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(88)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ko E. A., Han J., Jung I. D., Park W. S. Physiological roles of K+ channels in vascular smooth muscle cells. Journal of Smooth Muscle Research. 2008;44(2):65–81. doi: 10.1540/jsmr.44.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.den Hartog G. J. M., Boots A. W., Haenen G. R. M. M., van der Vijgh W. J. F., Bast A. Lack of inhibition of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in the isolated rat aorta by doxorubicin. Toxicology in Vitro. 2003;17(2):165–167. doi: 10.1016/s0887-2333(03)00007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mann G. E., Yudilevich D. L., Sobrevia L. Regulation of amino acid and glucose transporters in endothelial and smooth muscle cells. Physiological Reviews. 2003;83(1):183–252. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00022.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.González M., Gallardo V., Rodríguez N., et al. Insulin-stimulated L-arginine transport requires SLC7A1 gene expression and is associated with human umbilical vein relaxation. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2011;226(11):2916–2924. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Benites J., Valderrama J. A., Bettega K., Pedrosa R. C., Calderon P. B., Verrax J. Biological evaluation of donor-acceptor aminonaphthoquinones as antitumor agents. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2010;45(12):6052–6057. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ross R. The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis: a perspective for the 1990s. Nature. 1993;362(6423):801–809. doi: 10.1038/362801a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cecchettini A., Rocchiccioli S., Boccardi C., Citti L. Vascular smooth-muscle-cell activation. proteomics point of view. International Review of Cell and Molecular Biology. 2011;288:43–99. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-386041-5.00002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kang J.-J., Lee P.-J., Chen Y.-J., et al. Naphthazarin and methylnaphthazarin cause vascular dysfunction by impairment of endothelium-derived nitric oxide and increased superoxide anion generation. Toxicology in Vitro. 2006;20(1):43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ourique F., Kviecinski M. R., Felipe K. B., et al. DNA damage and inhibition of akt pathway in MCF-7 cells and ehrlich tumor in mice treated with 1,4-naphthoquinones in combination with ascorbate. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 2015;2015:10. doi: 10.1155/2015/495305.495305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jiang Q., Xiao N., Shi P., Zhu Y., Guo Z. Design of artificial metallonucleases with oxidative mechanism. Coordination Chemistry Reviews. 2007;251(15-16):1951–1972. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.02.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cifuentes F., Palacios J., Nwokocha C. R. Synchronization in the heart rate and the vasomotion in rat aorta: effect of arsenic trioxide. Cardiovascular Toxicology. 2016;16(1):79–88. doi: 10.1007/s12012-015-9312-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vásquez-Vivar J., Martasek P., Hogg N., Masters B. S. S., Pritchard K. A., Jr., Kalyanaraman B. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase-dependent superoxide generation from adriamycin. Biochemistry. 1997;36(38):11293–11297. doi: 10.1021/bi971475e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bae O.-N., Lim K.-M., Han J.-Y., et al. U-shaped dose response in vasomotor tone: a mixed result of heterogenic response of multiple cells to xenobiotics. Toxicological Sciences. 2008;103(1):181–190. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gerassimou C., Kotanidou A., Zhou Z., Simoes D. D. C., Roussos C., Papapetropoulos A. Regulation of the expression of soluble guanylyl cyclase by reactive oxygen species. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2007;150(8):1084–1091. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ermak G., Davies K. J. Calcium and oxidative stress: from cell signaling to cell death. Molecular Immunology. 2002;38(10):713–721. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(01)00108-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dejeans N., Tajeddine N., Beck R., et al. Endoplasmic reticulum calcium release potentiates the ER stress and cell death caused by an oxidative stress in MCF-7 cells. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2010;79(9):1221–1230. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Di Monte D., Bellomo G., Thor H., Nicotera P., Orrenius S. Menadione-induced cytotoxicity is associated with protein thiol oxidation and alteration in intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 1984;235(2):343–350. doi: 10.1016/s0344-0338(85)80151-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Williams S. B., Hablitz J. J. Differential modulation of repetitive firing and synchronous network activity in neocortical interneurons by inhibition of A-type K+ channels and Ih. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience. 2015;9, article 89 doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Quast U. Do the K+ channel openers relax smooth muscle by opening K+ channels? Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 1993;14(9):332–337. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(93)90006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Standen N. B., Quayle J. M., Davies N. W., Brayden J. E., Huang Y., Nelson M. T. Hyperpolarizing vasodilators activate ATP-sensitive K+ channels in arterial smooth muscle. Science. 1989;245(4914):177–180. doi: 10.1126/science.2501869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dora K. A., Ings N. T., Garland C. J. KCa channel blockers reveal hyperpolarization and relaxation to K+ in rat isolated mesenteric artery. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2002;283(2):H606–H614. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01016.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Varga Z., Bene L., Pieri C., Damjanovich S., Gáspár R. The effect of juglone on the membrane potential and whole-cell K+ currents of human lymphocytes. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1996;218(3):828–832. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Archer S. L., Huang J. M. C., Hampl V., Nelson D. P., Shultz P. J., Weir E. K. Nitric oxide and cGMP cause vasorelaxation by activation of a charybdotoxin-sensitive K channel by cGMP-dependent protein kinase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1994;91(16):7583–7587. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Murphy M. E., Brayden J. E. Nitric oxide hyperpolarizes rabbit mesenteric arteries via ATP-sensitive potassium channels. The Journal of Physiology. 1995;486(1):47–58. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhao Y. J., Wang J., Rubin L. J., Yuan X. J. Inhibition of K(V) and K(Ca) channels antagonizes NO-induced relaxation in pulmonary artery. American Journal of Physiology. 1997;272(2, part 2):H904–H912. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.2.H904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ruiz-Velasco V., Zhong J., Hume J. R., Keef K. D. Modulation of Ca2+ channels by cyclic nucleotide cross activation of opposing protein kinases in rabbit portal vein. Circulation Research. 1998;82(5):557–565. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.82.5.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Barnes P. J., Liu S. F. Regulation of pulmonary vascular tone. Pharmacological Reviews. 1995;47(1):87–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Khan S. A., Higdon N. R., Meisheri K. D. Coronary vasorelaxation by nitroglycerin: involvement of plasmalemmal calcium-activated K+ channels and intracellular Ca++ stores. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1998;284(3):838–846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gerasimenko J. V., Gerasimenko O. V., Palejwala A., Tepikin A. V., Petersen O. H., Watson A. J. M. Menadione-induced apoptosis: roles of cytosolic Ca2+ elevations and the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Journal of Cell Science. 2002;115(3):485–497. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.3.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Aranda E., Owen G. I. A semi-quantitative assay to screen for angiogenic compounds and compounds with angiogenic potential using the EA.hy926 endothelial cell line. Biological Research. 2009;42(3):377–389. doi: 10.4067/S0716-97602009000300012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]