Abstract

Background

Metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) patients receiving first-line sunitinib typically survive >2 yr, with chronic treatment sometimes extending to ≥6 yr.

Objective

To analyze long-term safety with sunitinib in mRCC patients.

Design, setting, and participants

Data were pooled from 5739 patients in nine trials, comprising seven phase II studies, a phase III study, and an expanded-access trial in various treatment settings (e.g. cytokine refractory or treatment-naïve).

Outcome measurements and statistical analysis

Interval and cumulative time-period analyses evaluated the incidence of treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) for up to 6 yr, in the overall population and in those with long-term (≥2 yr) sunitinib treatment.

Results and limitations

Among long-term patients (n=807), most TRAEs occurred initially in the first year and then decreased in frequency; TRAEs following this pattern included decreased appetite, diarrhea, dysgeusia, dyspepsia, fatigue, hypertension, mucosal inflammation, nausea, and stomatitis. However, hypothyroidism increased by interval analysis from 6% at 0–<6 mo to 42% at 5–<6 yr and by cumulative analysis from 14% at 0–<1 yr to 36% over 6 yr. Grade 3/4 TRAEs in long-term patients peaked during the first year and then steadily decreased. The overall population displayed only minor differences from long-term patients, with no clinically significant differences between grade ≥3 TRAE profiles (<5% difference in incidence rates at all intervals). Limitations included retrospective design, assessment variability, lack of pharmacokinetic data, and absence of baseline characteristics for long-term patients.

Conclusions

Prolonged sunitinib was not associated with new types or increased severity of TRAEs. Except hypothyroidism, toxicity was not cumulative.

Patient summary

More than 800 mRCC patients received sunitinib for between 2 and 6 yr without experiencing new or more severe treatment-related toxicity. Clinicians may be able to prescribe chronic sunitinib treatment for as long as patients continue to derive clinical benefit, without untoward additional risk.

Keywords: Long-term safety, Renal cell carcinoma, Sunitinib, Toxicity, Treatment-related adverse events

1. Introduction

Sunitinib malate (SUTENT) is an orally administered multitargeted receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) [1] that is approved globally for the treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC). Patients treated with first-line sunitinib typically survive for more than 2 yr; for example, in two phase 3 trials, first-line sunitinib therapy resulted in a median overall survival of 26.4 and 29.3 mo [2,3]. Subgroup analyses indicate that some patients (eg, those with favorable risk factors) can survive much longer [4,5], and reported treatment durations have exceeded 6 yr [6].

Chronic sunitinib treatment in patients with mRCC, potentially spanning many years, raises questions about its long-term safety. An early analysis of short- versus long-term sunitinib use (defined as <6 mo vs ≥6 mo) using preliminary data from an expanded-access trial in patients with mRCC found that despite an expected comparative increase in the overall incidence of treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs), serious toxicity was not cumulative and no new or unexpected long-term toxicities occurred [7].

Here we report a further study of long-term safety for sunitinib using pooled data from 5739 patients with mRCC enrolled in nine prospective clinical trials, including 807 patients treated for ≥2 yr. Two types of analysis are conducted: an interval analysis to investigate toxicities that may occur early, late, or at random times; and a cumulative analysis to uncover toxicities that may not have been previously disclosed (eg, similar to chemotherapy-induced neurotoxicity with long-term treatment) [8].

2. Patients and methods

2.1. Study design and dosing regimen

Safety data were pooled from nine prospective clinical trials of sunitinib in patients with mRCC, as well as from three rollover studies in which patients continued treatment, all of which were part of the Pfizer-sponsored clinical development program for sunitinib in advanced RCC (with no relevant studies excluded). The nine trials consisted of three phase 2 studies in cytokine-refractory patients (NCT00054886, NCT00077974, and NCT00137423) [9–11]; a phase 2 study in bevacizumab-refractory patients (NCT00089648) [12]; a phase 2 study of treatment-naïve and cytokine-refractory Japanese patients (NCT00254540) [13,14]; two phase 2 studies of treatment-naïve patients (NCT00338884 and NCT00267748) [15,16]; a pivotal phase 3 study of treatment-naïve patients who received either sunitinib or interferon-α (NCT00098657 and NCT00083889) [2,17]; and an expanded-access trial (NCT00130897) [18,19]. Common characteristics of the analysis population were age ≥18 yr (or aged ≥20 yr in one study [14]) with histologically confirmed metastatic RCC and adequate organ function [9–12,14–18]. With the exception of the expanded-access trial, which aimed to include a broader population [18], other eligibility criteria required patients to have Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status 0 or 1 [9–12,14,15,17] or Karnofsky performance status ≥70 [16] and no brain metastases.

All patients received oral sunitinib at either 50 mg/d on a 4/2 schedule (4 wk on treatment, 2 wk off treatment) in repeated 6-wk cycles or 37.5 mg/d on a continuous dosing schedule [9–12,14–18]. In most of the trials, adverse events were graded using version 3.0 of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events [2,10–12,14–16,18]. In one early trial, however, version 2.0 of the NCI Common Toxicity Criteria was used [9].

The studies were approved by the institutional review board or independent ethics committee of each participating center and were run in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice guidelines and applicable local regulatory requirements and laws.

2.2. Analytical methods

Two TRAE analyses were performed, one in patients who had been on sunitinib for ≥2 yr and another for all patients. The first analysis was an interval analysis in which the TRAE incidence was evaluated over the first 6 mo and then over successive 1-yr intervals as follows: 0–<6 mo, 0–<1 yr, 1–<2 yr, 2–<3 yr, 3–<4 yr, 4–<5 yr, and 5–<6 yr. Each adverse event was counted only once per interval but could be counted in more than one interval if it persisted. The second analysis was a cumulative analysis in which the cumulative TRAE incidence was evaluated in each of the following successive cumulative intervals, each defined from the start of treatment plus an additional 1 yr: 0–<1 yr, 0–<2 yr, 0–<3 yr, 0–<4 yr, 0–<5 yr, and 0–<6 yr. No safety data after 6 yr were available for analysis. Both analyses reviewed the incidence of any-grade, of grade 3–4, and of grade 5 TRAEs separately.

3. Results

3.1. Patients

At the data cutoff (October 2013), 5739 patients with mRCC had received treatment, of whom 807 (14%) received sunitinib for ≥2 yr (long-term patients). A total of 365 patients (6%) received sunitinib for ≥3 yr, 168 patients (3%) for ≥4 yr, and 77 patients (1%) for ≥5 yr.

Overall, the majority of patients were male (56–82% of patients across the nine trials from which data were pooled for this analysis), 89% had good or moderate performance status (ECOG 0 or 1, or Karnofsky ≥80), 90% had tumors of clear cell histology (or with a clear cell component), and 60% had received prior cytokine therapy (Supplementary Table 1). Some 6% of patients (all enrolled in the expanded-access trial) had brain metastases.

3.2. TRAEs in long-term patients

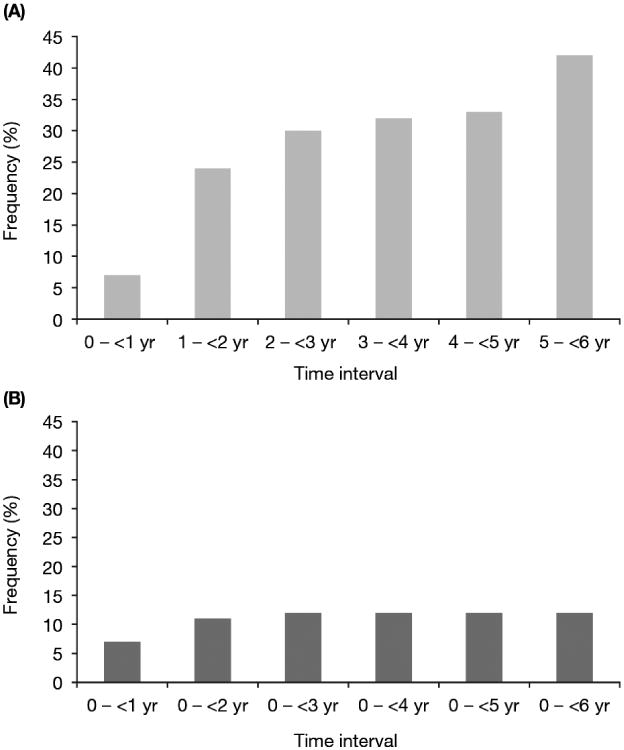

Among long-term patients, most TRAEs occurred initially in the first 6 mo-1 yr and then were stable or decreased in frequency over time in the interval analysis (Table 1). The notable exception to this pattern was hypothyroidism, which gradually increased from 6% at 0–<6 mo to 42% at 5–<6 yr, indicating that new cases were occurring. Cumulative analysis (Table 2), revealed that hypothyroidism increased from 14% at 0–<1 yr to 36% over the 6-yr period evaluated, a more than 2.5-fold cumulative increase, which was approximately double the increase in incidence over time of that of the other most common TRAEs (Table 2).

Table 1. Most common a any-grade treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma receiving long-term sunitinib according to interval analysis.

| Any-grade TRAE | Patients, n (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| 0–<6 mo (N = 807) |

0–<1 yr (N = 807) |

1–<2 yr (N = 807) |

2–<3 yr (N = 807) |

3–<4 yr (N = 365) |

4–<5 yr (N = 168) |

5–<6 yr (N = 77) |

|

| Any | 785 (97) | 796 (99) | 783 (97) | 767 (95) | 340 (93) | 157 (93) | 72 (94) |

| Diarrhea | 411 (51) | 533 (66) | 481 (60) | 378 (47) | 153 (42) | 65 (39) | 29 (38) |

| Fatigue | 386 (48) | 433 (54) | 359 (44) | 317 (39) | 130 (36) | 56 (33) | 25 (32) |

| Dysgeusia | 257 (32) | 281 (35) | 170 (21) | 113 (14) | 40 (11) | 15 (9) | 8 (10) |

| Stomatitis | 261 (32) | 288 (36) | 156 (19) | 86 (11) | 25 (7) | 17 (10) | 12 (16) |

| Nausea | 245 (30) | 302 (37) | 195 (24) | 147 (18) | 53 (15) | 26 (15) | 10 (13) |

| Hand–foot syndrome | 242 (30) | 320 (40) | 311 (39) | 251 (31) | 106 (29) | 52 (31) | 22 (29) |

| Hypertension | 222 (28) | 276 (34) | 230 (29) | 204 (25) | 94 (26) | 46 (27) | 23 (30) |

| Decreased appetite | 214 (27) | 262 (32) | 167 (21) | 113 (14) | 34 (9) | 17 (10) | 7 (9) |

| Dyspepsia | 220 (27) | 264 (33) | 182 (23) | 136 (17) | 59 (16) | 27 (16) | 16 (21) |

| Mucosal inflammation | 220 (27) | 248 (31) | 152 (19) | 100 (12) | 40 (11) | 22 (13) | 8 (10) |

| Rash | 152 (19) | 206 (26) | 121 (15) | 77 (10) | 22 (6) | 15 (9) | 5 (6) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 149 (18) | 184 (23) | 84 (10) | 47 (6) | 18 (5) | 3 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Vomiting | 141 (17) | 175 (22) | 109 (14) | 72 (9) | 20 (5) | 14 (8) | 3 (4) |

| Hair color changes | 125 (15) | 156 (19) | 142 (18) | 135 (17) | 62 (17) | 29 (17) | 11 (14) |

| Asthenia | 110 (14) | 136 (17) | 109 (14) | 76 (9) | 30 (8) | 11 (7) | 5 (6) |

| Neutropenia | 110 (14) | 142 (18) | 118 (15) | 70 (9) | 37 (10) | 12 (7) | 4 (5) |

| Skin discoloration | 102 (13) | 127 (16) | 84 (10) | 59 (7) | 29 (8) | 12 (7) | 4 (5) |

| Epistaxis | 94 (12) | 130 (16) | 82 (10) | 50 (6) | 18 (5) | 5 (3) | 2 (3) |

| Pain in extremity | 91 (11) | 141 (17) | 115 (14) | 85 (11) | 34 (9) | 16 (10) | 4 (5) |

| Hypothyroidism | 46 (6) | 110 (14) | 231 (29) | 241 (30) | 118 (32) | 55 (33) | 32 (42) |

Occurring in at least 15% of patients in at least one time interval.

Table 2. Most common a any-grade treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma receiving long-term sunitinib according to cumulative analysis (N = 807).

| Any-grade TRAE | Patients, n (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| 0–<1 yr | 0–<2 yr | 0–<3 yr | 0–<4 yr | 0–<5 yr | 0–<6 yr | |

| Any | 796 (99) | 800 (99) | 801 (99) | 803 (99) | 803 (99) | 803 (99) |

| Diarrhea | 533 (66) | 606 (75) | 629 (78) | 633 (78) | 634 (79) | 634 (79) |

| Fatigue | 433 (54) | 478 (59) | 492 (61) | 495 (61) | 495 (61) | 495 (61) |

| Hand–foot syndrome | 320 (40) | 385 (48) | 405 (50) | 414 (51) | 418 (52) | 418 (52) |

| Nausea | 302 (37) | 337 (42) | 353 (44) | 361 (45) | 366 (45) | 368 (46) |

| Hypertension | 276 (34) | 337 (42) | 356 (44) | 359 (44) | 361 (45) | 361 (45) |

| Decreased appetite | 262 (32) | 308 (38) | 315 (39) | 317 (39) | 323 (40) | 324 (40) |

| Stomatitis | 288 (36) | 310 (38) | 316 (39) | 318 (39) | 319 (40) | 320 (40) |

| Dysgeusia | 281 (35) | 303 (38) | 312 (39) | 313 (39) | 314 (39) | 314 (39) |

| Dyspepsia | 264 (33) | 303 (38) | 314 (39) | 317 (39) | 317 (39) | 318 (39) |

| Mucosal inflammation | 248 (31) | 280 (35) | 296 (37) | 300 (37) | 300 (37) | 300 (37) |

| Hypothyroidism | 110 (14) | 240 (30) | 273 (34) | 281 (35) | 286 (35) | 287 (36) |

| Rash | 206 (26) | 236 (29) | 249 (31) | 251 (31) | 253 (31) | 253 (31) |

| Vomiting | 175 (22) | 215 (27) | 231 (29) | 235 (29) | 239 (30) | 239 (30) |

| Pain in extremity | 141 (17) | 178 (22) | 198 (25) | 203 (25) | 204 (25) | 204 (25) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 184 (23) | 194 (24) | 201 (25) | 205 (25) | 205 (25) | 205 (25) |

| Neutropenia | 142 (18) | 180 (22) | 191 (24) | 197 (24) | 197 (24) | 197 (24) |

| Asthenia | 136 (17) | 160 (20) | 171 (21) | 174 (22) | 175 (22) | 176 (22) |

| Epistaxis | 130 (16) | 169 (21) | 178 (22) | 180 (22) | 181 (22) | 181 (22) |

| Anemia | 84 (10) | 133 (16) | 162 (20) | 168 (21) | 169 (21) | 170 (21) |

| Hair color changes | 156 (19) | 168 (21) | 170 (21) | 173 (21) | 173 (21) | 173 (21) |

| Constipation | 119 (15) | 149 (18) | 156 (19) | 159 (20) | 159 (20) | 160 (20) |

| Headache | 116 (14) | 142 (18) | 156 (19) | 156 (19) | 158 (20) | 159 (20) |

| Dry skin | 105 (13) | 133 (16) | 147 (18) | 151 (19) | 151 (19) | 151 (19) |

| Skin discoloration | 127 (16) | 143 (18) | 146 (18) | 147 (18) | 147 (18) | 147 (18) |

| Edema peripheral | 61 (8) | 110 (14) | 129 (16) | 132 (16) | 136 (17) | 136 (17) |

| Abdominal pain | 79 (10) | 114 (14) | 125 (15) | 125 (15) | 125 (15) | 125 (15) |

Occurringin at least 15% of patients.

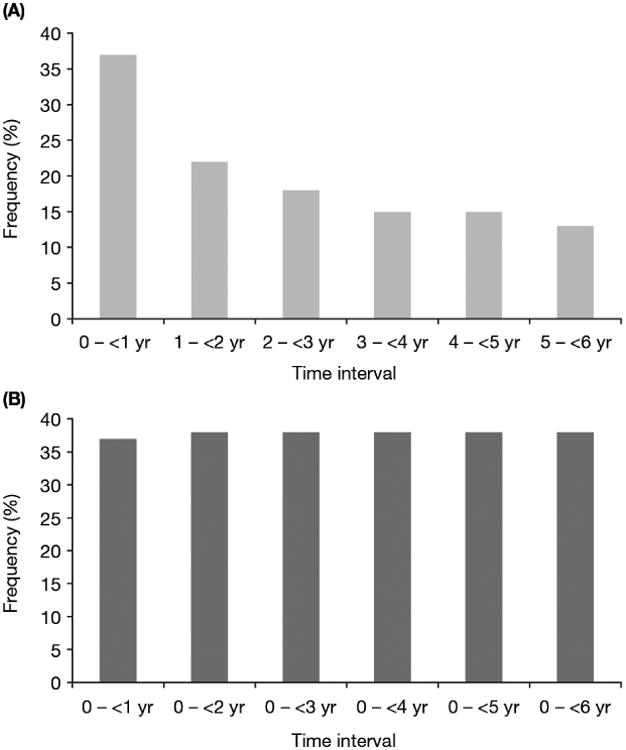

Common TRAEs that decreased in frequency after the first year in the interval analysis of long-term patients included decreased appetite, diarrhea, dysgeusia, dyspepsia, fatigue, hypertension, mucosal inflammation, nausea, and stomatitis. Decreases were fairly steady, but tended to plateau after the first 2–3 yr (eg, dysgeusia, hand-foot syndrome, mucosal inflammation, and nausea). The incidence of hypertension decreased from 34% in the first year to 29% in the second year of treatment and then remained relatively stable in frequency.

According to the interval analysis, the occurrence of grade 3/4 TRAEs in long-term patients peaked during the first year at 52%, decreased to 36% the next year, and steadily decreased thereafter (Supplementary Table 2). The most common grade 3/4 TRAEs during the first year were hand-foot syndrome (9%), hypertension (8%), fatigue (7%), thrombocytopenia (6%), neutropenia (6%), and diarrhea (5%), all of which steadily decreased or remained stable thereafter in the interval analysis. Cumulative analysis revealed that the frequency of these grade 3/4 TRAEs increased from 9% to 13%, 8% to 12%, 7% to 11%, 6% to 7%, 6% to 9%, and 5% to 11%, respectively, over the 6-yr period evaluated (Supplementary Table 3); in addition, grade 3/4 anemia increased from 1% to 4% over this cumulative analysis period.

3.3. TRAEs in all patients

There were minor differences in TRAE patterns between long-term patients and all patients in the interval analyses (Tables 1 and 3, any grade; Supplementary Tables 2 and 4, grade 3/4). For example, anemia did not occur with sufficient frequency (in at least 15%) in long-term patients during any interval, whereas skin discoloration occurred in more than 15% of long-term patients during the first year, but did not reach this frequency in the overall population. However, cumulative analyses showed that new TRAE occurrences reached a plateau in both groups (Tables 2 and 4, any grade), with no clinically significant differences between the TRAE grade ≥3 profiles of either group (<5% absolute difference in overall incidence rates at all times according to interval analysis [Supplementary Tables 2 and 4], with similar differences in individual incidence rates according to cumulative analysis [Supplementary Tables 3 and 5]).

Table 3. Most common a any-grade treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) in all patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma according to interval analysis.

| Any-grade TRAE | Patients, n (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| 0–<6 mo (N = 5739) |

0–<1 yr (N = 5739) |

1–<2 yr (N = 1982) |

2–<3 yr (N = 807) |

3–<4 yr (N = 365) |

4–<5 yr (N = 168) |

5–<6 yr (N = 77) |

|

| Any | 5449 (95) | 5472 (95) | 1905 (96) | 767 (95) | 340 (93) | 157 (93) | 72 (94) |

| Diarrhea | 2342 (41) | 2692 (47) | 942 (48) | 378 (47) | 153 (42) | 65 (39) | 29 (38) |

| Fatigue | 2193 (38) | 2383 (42) | 796 (40) | 317 (39) | 130 (36) | 56 (33) | 25 (32) |

| Nausea | 1905 (33) | 2101 (37) | 438 (22) | 147 (18) | 53 (15) | 26 (15) | 10 (13) |

| Decreased appetite | 1566 (27) | 1770 (31) | 400 (20) | 113 (14) | 34 (9) | 17 (10) | 7 (9) |

| Dysgeusia | 1504 (26) | 1579 (28) | 411 (21) | 113 (14) | 40 (11) | 15 (9) | 8 (10) |

| Stomatitis | 1486 (26) | 1585 (28) | 313 (16) | 86 (11) | 25 (7) | 17 (10) | 12 (16) |

| Mucosal inflammation | 1455 (25) | 1566 (27) | 355 (18) | 100 (12) | 40 (11) | 22 (13) | 8 (10) |

| Vomiting | 1307 (23) | 1494 (26) | 256 (13) | 72 (9) | 20 (5) | 14 (8) | 3 (4) |

| Hypertension | 1195 (21) | 1349 (24) | 464 (23) | 204 (25) | 94 (26) | 46 (27) | 23 (30) |

| Hand–foot syndrome | 1228 (21) | 1487 (26) | 664 (34) | 251 (31) | 106 (29) | 52 (31) | 22 (29) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 1072 (19) | 1184 (21) | 226 (11) | 47 (6) | 18 (5) | 3 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Asthenia | 1011 (18) | 1130 (20) | 316 (16) | 76 (9) | 30 (8) | 11 (7) | 5 (6) |

| Dyspepsia | 989 (17) | 1109 (19) | 362 (18) | 136 (17) | 59 (16) | 27 (16) | 16 (21) |

| Rash | 850 (15) | 982 (17) | 246 (12) | 77 (10) | 22 (6) | 15 (9) | 5 (6) |

| Neutropenia | 705 (12) | 816 (14) | 309 (16) | 70 (9) | 37 (10) | 12 (7) | 4 (5) |

| Anemia | 643 (11) | 797 (14) | 317 (16) | 102 (13) | 36 (10) | 15 (9) | 8 (10) |

| Hair color changes | 578 (10) | 657 (11) | 322 (16) | 135 (17) | 62 (17) | 29 (17) | 11 (14) |

| Hypothyroidism | 166 (3) | 392 (7) | 482 (24) | 241 (30) | 118 (32) | 55 (33) | 32 (42) |

Occurring in at least 15% of patients in any one interval.

Table 4. Most common a any-grade treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) in all patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma according to cumulative analysis (N = 5739).

| Any-grade TRAE | Patients, n (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| 0–<1 yr | 0–<2 yr | 0–<3 yr | 0–<4 yr | 0–<5 yr | 0–<6 yr | |

| Any | 5472 (95) | 5484 (96) | 5485 (96) | 5487 (96) | 5487 (96) | 5487 (96) |

| Diarrhea | 2692 (47) | 2821 (49) | 2844 (50) | 2848 (50) | 2849 (50) | 2849 (50) |

| Fatigue | 2383 (42) | 2470 (43) | 2484 (43) | 2487 (43) | 2487 (43) | 2487 (43) |

| Nausea | 2101 (37) | 2177 (38) | 2193 (38) | 2201 (38) | 2206 (38) | 2208 (38) |

| Decreased appetite | 1770 (31) | 1854 (32) | 1861 (32) | 1863 (32) | 1869 (33) | 1870 (33) |

| Mucosal inflammation | 1566 (27) | 1620 (28) | 1636 (29) | 1640 (29) | 1640 (29) | 1640 (29) |

| Stomatitis | 1585 (28) | 1634 (28) | 1640 (29) | 1642 (29) | 1643 (29) | 1644 (29) |

| Dysgeusia | 1579 (28) | 1623 (28) | 1632 (28) | 1633 (28) | 1634 (28) | 1634 (28) |

| Hand-foot syndrome | 1487 (26) | 1597 (28) | 1617 (28) | 1626 (28) | 1630 (28) | 1630 (28) |

| Vomiting | 1494 (26) | 1583 (28) | 1599 (28) | 1603 (28) | 1607 (28) | 1607 (28) |

| Hypertension | 1349 (24) | 1448 (25) | 1467 (26) | 1470 (26) | 1472 (26) | 1472 (26) |

| Asthenia | 1130 (20) | 1185 (21) | 1196 (21) | 1199 (21) | 1200 (21) | 1201 (21) |

| Dyspepsia | 1109 (19) | 1177 (21) | 1188 (21) | 1191 (21) | 1191 (21) | 1192 (21) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 1184 (21) | 1216 (21) | 1223 (21) | 1227 (21) | 1227 (21) | 1227 (21) |

| Rash | 982 (17) | 1047 (18) | 1060 (18) | 1062 (19) | 1064 (19) | 1064 (19) |

| Anemia | 797 (14) | 915 (16) | 945 (16) | 951 (17) | 952 (17) | 953 (17) |

| Neutropenia | 816 (14) | 891 (16) | 902 (16) | 908 (16) | 908 (16) | 908 (16) |

Occurring in at least 15% of patients.

Interval analysis for all patients (Table 3) revealed that, as in long-term patients, hypothyroidism notably increased in frequency between the first and last intervals (Fig. 1). Other TRAEs substantially decreased over time, including asthenia, decreased appetite, dysgeusia, mucosal inflammation, nausea (Fig. 2A; interval analysis), thrombocytopenia, and vomiting. Most cardiovascular TRAEs occurred during the first year (Supplementary Tables 6 and 7). Hypertension, the most common cardiovascular event, was observed in 24% of all patients during this period (Table 3); otherwise, most cardiovascular TRAEs occurred in <1% of patients during the first year. Grade 5 TRAEs occurred in 1% of all patients, primarily during the first 6 mo of treatment (Supplementary Table 4).

Fig. 1.

Incidence of treatment-related hypothyroidism in all patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma receiving sunitinib according to (A) interval analysis and (B) cumulative analysis.

Fig. 2.

Incidence of treatment-related nausea in all patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma receiving sunitinib according to (A) interval analysis and (B) cumulative analysis.

4. Discussion

The development of oral targeted agents has fundamentally changed the treatment landscape in mRCC over the last 10 yr. However, long-term safety for chronic use of these agents, which have been accepted as the standard of care, has not been established. With more than 800 patients with mRCC (14%) treated for 2–6 yr and 77 patients (1%) treated for ≥5 yr, the present analysis of long-term sunitinib use is the largest published to date. Although the number of patients receiving sunitinib beyond 3 yr remains relatively small (n = 365), the results suggest that prolonged sunitinib treatment in patients with mRCC is not associated with new TRAE types or increased TRAE severity. These findings are consistent with an earlier analysis that included only 189 long-term patients (patients treated for ≥2 yr) [20].

While the majority of TRAEs appeared within the 6 mo to 1 yr of treatment and then stabilized or (more typically) declined in frequency, according to the interval analysis (remaining stable or increasing by cumulative analysis), hypothyroidism appeared to be a cumulative and delayed toxicity. Sunitinib-related hypothyroidism is well documented [21], although the exact molecular mechanisms causing it are unknown (and the general prevalence of non–treatment-related hypothyroidism in long-term survivors with mRCC is unknown). One of the most plausible theories is that sunitinib induces capillary regression in the thyroid gland via inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor and platelet-derived growth factor receptors [22,23], and affects T4/T3 metabolism [23]. Our observation that the onset of hypothyroidism is often delayed supports previously published recommendations to monitor patients for this toxicity throughout sunitinib treatment by measuring thyroid-stimulating hormone on the first day of every cycle of treatment [24]. Severe hypothyroidism is infrequent and can usually be corrected by thyroid hormone replacement therapy. Detection and subsequent management of hypothyroidism are also important for controlling associated symptoms such as fatigue.

In this pooled analysis, most cardiovascular TRAEs were rare, but developed during the first year of treatment; hypertension was the most common. Cardiotoxicity is a recognized risk of TKI therapy, including sunitinib therapy [25]. In a phase 3 trial, 13% of patients randomized to sunitinib had a decline in left ventricular ejection fraction compared with 3% of those in the interferon-α arm [2], with grade 3 reductions reported in 3% and 1% of patients, respectively. Some retrospective analyses have reported relatively high levels of cardiovascular dysfunction and heart failure during sunitinib treatment [26,27], but the final analysis of the sunitinib expanded-access program showed that rates of cardiac failure and congestive cardiac failure were low (<1%) among more than 4500 treated patients [19]. The demonstration by the present analysis that sunitinib-associated cardiovascular toxicity is not cumulative is clinically important, particularly for an indication for which substantial numbers of patients received chronic treatment lasting several years. The sole objective of our analysis was to examine the important question of long-term safety of sunitinib treatment in patients with mRCC, and it did not allow identification of prognostic factors for long-term survival or of TRAEs as potential predictors of long-term treatment with sunitinib. A recent analysis of pooled data from 1059 patients with mRCC treated with sunitinib found that independent prognostic factors for long-term survival (defined as ≥30 mo) were ethnic origin, baseline bone metastases, and baseline corrected calcium level [4]. Other retrospective analyses have suggested that a number of TRAEs may be linked to response to sunitinib, including hypertension, hypothyroidism, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and skin toxicity [28–30]. The present extensive set of pooled data offers ample scope for further, more powerful analyses to investigate both prognostic and predictive factors associated with long-term treatment and response to sunitinib.

Despite such a large comprehensive database, the following are specific limitations of this study in addition to the usual issues associated with a retrospective analysis. Variability in toxicity assessment across multiple studies and time periods may have impacted consistent adverse-event reporting (eg, investigator assessment of treatment relatedness, which depends on medical judgment), although use of a standardized reporting system in each study may have minimized this impact. Lack of pharmacokinetic data prohibits assessment of the impact of drug exposure. The small proportion of patients who received treatment for ≥5 yr (n = 77) may limit conclusions about toxicity at this upper extreme of long-term treatment. Finally, the absence of information regarding the baseline characteristics of long-term patients precludes investigation of prognostic factors that may have influenced who remained on treatment.

In summary, our study shows that 807 patients with mRCC have been treated with sunitinib for between 2 and 6 yr without experiencing new or more severe treatment-related toxicity compared with the overall treated population. It therefore seems that clinicians can prescribe chronic treatment with sunitinib in this population for as long as patients continue to derive clinical benefit without untoward additional risk. The questions of whether this is the optimum strategy in terms of patient outcomes and whether certain subpopulations would survive as long with potentially better quality of life by discontinuing or switching treatment, or by having treatment “holidays,” remain unanswered.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1. Baseline patient characteristics

Supplementary Table 2. Most commona grade 3/4 treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) in mRCC patients receiving long-term sunitinib, by interval analysis

Supplementary Table 3. Most commona grade 3/4 treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) in mRCC patients receiving long-term sunitinib, by cumulative analysis (N=807)

Supplementary Table 4. Most commona grade 3/4 treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) in all mRCC patients, by interval analysis

Supplementary Table 5. Most commona grade 3/4 treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) in all mRCC patients, by cumulative analysis (N=5739)

Supplementary Table 6. Key any-grade cardiovascular treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) in all mRCC patients, by interval analysis

Supplementary Table 7. Key any-grade cardiovascular treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) in all mRCC patients, by cumulative analysis (N=5739)

Acknowledgments

Funding/support and role of the sponsor: These analyses were designed, funded, and conducted by Pfizer (New York, NY, USA). The nine prospective clinical trials and three rollover studies of sunitinib from which safety data were collected for these analyses were sponsored by Pfizer. The sponsor played a role in study design and conduct and in data collection, management, and analysis.

Footnotes

Author contributions: Camillo Porta had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Porta, Hariharan, Charles, Yang.

Acquisition of data: Porta, Gore, Rini, Escudier, Motzer.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Porta, Gore, Rini, Escudier, Hariharan, Charles, Yang, DeAnnuntis, Motzer.

Drafting of the manuscript: Porta, Gore, Rini, Escudier, Hariharan, Charles, Yang, DeAnnuntis, Motzer.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Porta, Gore, Rini, Escudier, Hariharan, Charles, Yang, DeAnnuntis, Motzer.

Statistical analysis: Yang.

Obtaining funding: Hariharan, Charles.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Yang.

Supervision: Hariharan, Charles.

Other: None.

Financial disclosures: Camillo Porta certifies that all conflicts of interest, including specific financial interests and relationships and affiliations relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript (eg, employment/affiliation, grants or funding, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, royalties, or patents filed, received, or pending), are the following: Camillo Porta has received consultancy fees from Pfizer, Bayer Schering Pharma, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Boehringer-Ingelheim, and AVEO/Astellas; honoraria from Pfizer, Bayer Schering Pharma, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, and Astellas; and research funding from Pfizer, Bayer Schering Pharma, and Novartis. Martin E. Gore has received consultancy fees from Pfizer and Astellas and honoraria from Roche, Pfizer, Novartis, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. Brian I. Rini has received research funding and consulting fees from Pfizer. Bernard Escudier has received consultancy fees from Bayer, Pfizer, and Novartis; and honoraria from Bayer, Roche, Pfizer, Genentech, Novartis, and AVEO. Subramanian Hariharan, Liqiang Yang, and Liza DeAnnuntis are full-time employees of Pfizer and hold Pfizer stock. Lorna P. Charles was an employee of Pfizer when these analyses were conducted. Robert J. Motzer has received research funding and consultant fees from Pfizer and has been compensated for expert testimony by Pfizer.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Chow LQ, Eckhardt SG. Sunitinib: from rational design to clinical efficacy. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:884–96. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.3602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, et al. Overall survival and updated results for sunitinib compared with interferon alfa in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3584–90. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Cella D, et al. Pazopanib versus sunitinib in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:722–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1303989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, Bukowski R, et al. Prognostic factors for survival in 1059 patients treated with sunitinib for metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:2470–7. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, McCann L, Deen K, Choueiri TK. Overall survival in renal-cell carcinoma with pazopanib versus sunitinib. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1769–70. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1400731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Molina AM, Jia X, Feldman DR, et al. Long-term response to sunitinib therapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2013;11:297–302. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Porta C, Szczylik C, Bracarda S, et al. Short- and long-term safety with sunitinib in an expanded access trial in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(15 Suppl):5114. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grisold W, Cavaletti G, Windebank AJ. Peripheral neuropathies from chemotherapeutics and targeted agents: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Neuro Oncol. 2012;14(Suppl 4):iv45–54. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nos203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Motzer RJ, Michaelson MD, Redman BG, et al. Activity of SU11248, a multitargeted inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor and platelet-derived growth factor receptor, in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:16–24. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.2574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Motzer RJ, Rini BI, Bukowski RM, et al. Sunitinib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. JAMA. 2006;295:2516–24. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.21.2516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Escudier B, Roigas J, Gillessen S, et al. Phase II study of sunitinib administered in a continuous once-daily dosing regimen in patients with cytokine-refractory metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4068–75. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.5476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rini BI, Michaelson MD, Rosenberg JE, et al. Antitumor activity and biomarker analysis of sunitinib in patients with bevacizumab-refractory metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3743–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.5416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tomita Y, Shinohara N, Yuasa T, et al. Overall survival and updated results from a phase II study of sunitinib in Japanese patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2010;40:1166–72. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyq146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uemura H, Shinohara N, Yuasa T, et al. A phase II study of sunitinib in Japanese patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: insights into the treatment, efficacy and safety. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2010;40:194–202. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyp146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barrios CH, Hernandez-Barajas D, Brown MP, et al. Phase II trial of continuous once-daily dosing of sunitinib as first-line treatment in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2012;118:1252–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Olsen MR, et al. Randomized phase II trial of sunitinib on an intermittent versus continuous dosing schedule as first-line therapy for advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1371–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.4133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, et al. Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:115–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gore ME, Szczylik C, Porta C, et al. Safety and efficacy of sunitinib for metastatic renal-cell carcinoma: an expanded-access trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:757–63. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70162-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gore ME, Bukowski R, Porta C, et al. Sunitinib global expanded-access trial in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: final results. Presented at the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) 2012 congress. www.poster-submission.com/cdrom/download_poster/33/22224/820.

- 20.Porta C, Gore ME, Rini BI, et al. Long-term safety with sunitinib in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Presented at the European Cancer Congress; September 27–October 1, 2013; Amsterdam, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bianchi L, Rossi L, Tomao F, Papa A, Zoratto F, Tomao S. Thyroid dysfunction and tyrosine kinase inhibitors in renal cell carcinoma. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2013;20:R233–45. doi: 10.1530/ERC-13-0201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Makita N, Miyakawa M, Fujita T, Iiri T. Sunitinib induces hypothyroidism with a markedly reduced vascularity. Thyroid. 2010;20:323–6. doi: 10.1089/thy.2009.0414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kappers MH, van Esch JH, Smedts FM, et al. Sunitinib-induced hypothyroidism is due to induction of type 3 deiodinase activity and thyroidal capillary regression. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:3087–94. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eisen T, Sternberg CN, Robert C, et al. Targeted therapies for renal cell carcinoma: review of adverse event management strategies. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:93–113. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mellor HR, Bell AR, Valentin JP, Roberts RR. Cardiotoxicity associated with targeting kinase pathways in cancer. Toxicol Sci. 2011;120:14–32. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfq378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chu TF, Rupnick MA, Kerkela R, et al. Cardiotoxicity associated with tyrosine kinase inhibitor sunitinib. Lancet. 2007;370:2011–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61865-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Di Lorenzo G, Autorino R, Bruni G, et al. Cardiovascular toxicity following sunitinib therapy in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a multicenter analysis. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1535–42. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poprach A, Pavlik T, Melichar B, et al. on behalf of the Czech Renal Cancer Cooperative Group. Skin toxicity and efficacy of sunitinib and sorafenib in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a national registry-based study. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:3137–43. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kust D, Prpić M, Murgić J, et al. Hypothyroidism as a predictive clinical marker of better treatment response to sunitinib therapy. Anticancer Res. 2014;34:3177–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rautiola J, Donskov F, Peltola K, Joensuu H, Bono P. Sunitinib-induced hypertension, neutropenia and thrombocytopenia as predictors of good prognosis in metastatic renal cell carcinoma patients. BJU Int. doi: 10.1111/bju.12940. In press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/bju.12940. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1. Baseline patient characteristics

Supplementary Table 2. Most commona grade 3/4 treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) in mRCC patients receiving long-term sunitinib, by interval analysis

Supplementary Table 3. Most commona grade 3/4 treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) in mRCC patients receiving long-term sunitinib, by cumulative analysis (N=807)

Supplementary Table 4. Most commona grade 3/4 treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) in all mRCC patients, by interval analysis

Supplementary Table 5. Most commona grade 3/4 treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) in all mRCC patients, by cumulative analysis (N=5739)

Supplementary Table 6. Key any-grade cardiovascular treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) in all mRCC patients, by interval analysis

Supplementary Table 7. Key any-grade cardiovascular treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) in all mRCC patients, by cumulative analysis (N=5739)