Abstract

Background

Myopia (near‐sightedness or short‐sightedness) is a condition in which the refractive power of the eye is greater than required. The most frequent complaint of people with myopia is blurred distance vision, which can be eliminated by conventional optical aids such as spectacles or contact lenses, or by refractive surgery procedures such as photorefractive keratectomy (PRK) and laser epithelial keratomileusis (LASEK). PRK uses laser to remove the corneal stroma. Similar to PRK, LASEK first creates an epithelial flap and then replaces it after ablating the corneal stroma. The relative benefits and harms of LASEK and PRK, as shown in different trials, warrant a systematic review.

Objectives

The objective of this review is to compare LASEK versus PRK for correction of myopia by evaluating their efficacy and safety in terms of postoperative uncorrected visual acuity, residual refractive error, and associated complications.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL (which contains the Cochrane Eyes and Vision group Trials Register) (2015 Issue 12), Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid MEDLINE In‐Process and Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE Daily, Ovid OLDMEDLINE (January 1946 to December 2015), EMBASE (January 1980 to December 2015), Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences (LILACS) (January 1982 to December 2015), the ISRCTN registry (www.isrctn.com/editAdvancedSearch), ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov) and the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (www.who.int/ictrp/search/en). We did not use any date or language restrictions in the electronic searches for trials. We last searched the electronic databases on 15 December 2015. We used the Science Citation Index and searched the reference lists of the included trials to identify relevant trials for this review.

Selection criteria

We included in this review randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing LASEK versus PRK for correction of myopia. Trial participants were 18 years of age or older and had no co‐existing ocular or systemic diseases that might affect refractive status or wound healing.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently screened all reports and assessed the risk of bias of trials included in this review. We extracted data and summarized findings using risk ratios and mean differences. We used a random‐effects model when we identified at least three trials, and we used a fixed‐effect model when we found fewer than three trials.

Main results

We included 11 RCTs with a total of 428 participants 18 years of age or older with low to moderate myopia. These trials were conducted in the Czech Republic, Brazil, Italy, Iran, China, Korea, Mexico, Turkey, USA, and UK. Investigators of 10 out of 11 trials randomly assigned one eye of each participant to be treated with LASEK and the other with PRK, but did not perform paired‐eye (matched) analysis. Because of differences in outcome measures and follow‐up times among the included trials, few trials contributed data for many of the outcomes we analyzed for this review. Overall, we judged RCTs to be at unclear risk of bias due to poor reporting; however, because of imprecision, inconsistency, and potential reporting bias, we graded the quality of the evidence from very low to moderate for outcomes assessed in this review.

The proportion of eyes with uncorrected visual acuity of 20/20 or better at 12‐month follow‐up was comparable in LASEK and PRK groups (risk ratio (RR) 0.98, 95% confidence interval (95% CI) 0.92 to 1.05). Although the 95% CI suggests little to no difference in effect between groups, we judged the quality of the evidence to be low because only one trial reported this outcome (102 eyes). At 12 months post treatment, data from two trials suggest no difference or a possibly small effect in favor of PRK over LASEK for the proportion of eyes achieving ± 0.50 D of target refraction (RR 0.93, 95% CI 00.84 to 1.03; 152 eyes; low‐quality evidence). At 12 months post treatment, one trial reported that one of 51 eyes in the LASEK group lost one line or more best‐spectacle corrected visual acuity compared with none of 51 eyes in the PRK group (RR 3.00, 95% CI 0.13 to 71.96; very low‐quality evidence).

Three trials reported adverse outcomes at 12 months of follow‐up or longer. At 12 months post treatment, three trials reported corneal haze score; however, data were insufficient and were inconsistent among the trials, precluding meta‐analysis. One trial reported little or no difference in corneal haze scores between groups; another trial reported that corneal haze scores were lower in the LASEK group than in the PRK group; and one trial did not report analyzable data to estimate a treatment effect. At 24 months post treatment, one trial reported a lower, but clinically unimportant, difference in corneal haze score for LASEK compared with PRK (MD ‐0.22, 95% CI ‐0.30 to ‐0.14; 184 eyes; low‐quality evidence).

Authors' conclusions

Uncertainty surrounds differences in efficacy, accuracy, safety, and adverse effects between LASEK and PRK for eyes with low to moderate myopia. Future trials comparing LASEK versus PRK should follow reporting standards and follow correct analysis. Trial investigators should expand enrollment criteria to include participants with high myopia and should evaluate visual acuity, refraction, epithelial healing time, pain scores, and adverse events.

Plain language summary

Two different surgical procedures for people who are near‐sighted

Research question How does laser‐assisted subepithelial keratectomy compare with photorefractive keratectomy for eyes with myopia?

Background Myopia (short‐sightedness or near‐sightedness) is a condition whereby people cannot see distant objects clearly. The prevalence of myopia is increasing worldwide, especially in some Asian areas. Spectacles and contact lenses are commonly used for correction of this condition. Surgical procedures such as laser‐assisted subepithelial keratectomy (LASEK) and photorefractive keratectomy (PRK) also can be used for correction of myopia. In both procedures, a laser is used to remove corneal tissue (front of the eye); these procedures have been performed in human eyes for nearly 30 years.

Study characteristics We identified 11 trials that enrolled 428 adult participants. These trials were conducted in various countries, including the Czech Republic, Brazil, Italy, Iran, China, Korea, Mexico, Turkey, USA, and UK. Ten out of 11 trials used a paired‐eye design, in which one eye of each participant received LASEK and the other eye received PRK. The remaining trial included one eye of six participants and both eyes of 15 participants. Most participants included in the trials had low to moderate myopia. The evidence is current as of 15 December 2015.

Key results Because these trials reported different outcomes at different time points, it is difficult to compare the effectiveness of LASEK versus PRK across trials. We assessed our primary outcomes 12 months after the surgeries were performed. Available data were insufficient to clarify whether LASEK performed better than PRK with respect to correcting visual acuity to 20/20 or better, achieving within 0.50 diopters of target refraction, or preventing loss of corrected visual acuity. Data were insufficient for assessment of whether differences between procedures in adverse outcomes occurred at 12 months after the surgeries. At 24 months post treatment, one trial reported that eyes treated LASEK with may have better corneal haze scores than those treated with PRK, but that the difference may not be noticeable.

Quality of the evidence Available data were insufficient for investigation of whether LASEK or PRK is better at correcting near‐sightedness. We judged the evidence for most outcomes as very low to moderate quality because of variation in reporting and differences in effects among trials.

Summary of findings

for the main comparison.

| Laser epithelial keratomileusis (LASEK) compared with photorefractive keratectomy (PRK) for myopia | ||||||

|

Population: adult participants (≥ 18 years) with myopia Settings: surgical procedure Intervention: LASEK Comparison: PRK | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of eyes** (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| PRK | LASEK | |||||

| UCVA of 20/20 or better at 12 months post treatment | 980 per 1000 | 961 per 1000 (902 to 1000) | RR 0.98 (0.92 to 1.05) | 102 (1 trial ) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa | RR < 1 favors PRK |

|

Within ± 0.50 D of target refraction at 12 months post treatment |

934 per 1000 | 869 per 1000 (785 to 962) | RR 0.93 (0.84 to 1.03) | 152 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb,c | RR < 1 favors PRK |

| Loss of 1 or more lines of BSCVA at 12 months post treatment | See comment | See comment |

RR 3.00 (0.13 to 71.96) |

102 (1 trial) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,c | No event in the PRK group compared with one event in the LASEK group observed; RR > 1 favors PRK |

| Mean spherical equivalent at 12 months post treatment | Mean spherical equivalent ranged across control groups from ‐0.27 to 0.17 D | Mean spherical equivalent in intervention group was 0.06 D higher (0.02 lower to 0.14 higher) | 386 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderateb | ||

|

Adverse outcomes ‐ corneal haze score at 12 months (grade 1.0 ‐ more prominent haze that does not interfere with visibility of fine iris details; grade 2.0 ‐ mild obscuration of iris details; grade 3.0 ‐ moderate obscuration of iris and lens; and grade 4.0 ‐ completely opaque stroma in the area of ablation) |

See comment | See comment | 284 eyes (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb,c,d | The 3 included studies showed inconsistent results, so no pooled analysis was done. One study showed little or no difference in corneal haze score between LASEK and PRK, one study reported that corneal haze scores were lower in the LASEK group than in the PRK group, and one study did not report analyzable data for the PRK group, so we could not estimate the treatment effect for this trial. | |

|

Adverse outcomes ‐ glare and halo scores at 3 months (grade 0 ‐ none; grade 1 ‐ very low; grade 2 ‐ low; grade 3 ‐ moderate; grade 4 ‐ high; and grade 5 ‐ very high) |

See comment | See comment | 64 eyes (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,c | Only 1 included study reported these adverse effects; below are the reported estimates For glare score: MD ‐0.04, 95% CI ‐0.61 to 0.53 For halo score: MD ‐0.09, 95% CI ‐0.72 to 0.54 |

|

| *The basis for the assumed risk is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI) **Both eyes of participants were included for all studies (i.e. all studies used a paired‐eye design in which 1 eye received PRK and the fellow eye received LASEK) BSCVA: best spectacle‐corrected visual acuity; CI: confidence interval; D: diopters; LASEK: laser epithelial keratomileusis;MD: mean difference; PRK: photorefractive keratectomy; RR: risk ratio; UCVA: uncorrected visual acuity | ||||||

| GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate | ||||||

Assumed control risk (ACR) is calculated using this algorithm; in the control group (total number of events/total number of eyes) × 100 = ACR

aDowngraded for potential reporting bias (‐2): core outcome reported by only 1 study. bDowngraded for potential reporting bias (‐1): outcome reported by three or fewer of the 11 included studies. cDowngraded for imprecision (‐1): wide confidence intervals or confidence intervals that do not rule out small effect differences. dDowngraded for inconsistency (‐1): effect estimates in different directions. See comments for details

Background

Description of the condition

Myopia is a condition in which the refractive power of the eye is greater than is required. In people with myopia, light rays from distant objects focus anterior to the retina as a result of mismatched components of the refractive system, for example, longer axial length of the eyeball or greater power of the dioptric media. Based on the diopter (D), myopia can be divided into three levels: low myopia (0.00 to ‐3.00 D), moderate myopia (‐3.00 to ‐6.00 D), and high myopia (over ‐6.00 D).

The prevalence of myopia varies across ethnic groups and countries. Myopia affects approximately 25% of Caucasians 40 years of age or older (Kempen 2004) and up to 80% of Asians in some areas, such as Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore, and mainland China (He 2009; Lam 2004; Lin 2004; Wong 2000). The most frequent complaint of people with myopia is blurred vision, which can be diagnosed easily through refraction by an optometrist or physician, and can be eliminated by optical aids (such as spectacles or contact lenses) or refractive surgery procedures. Refractive correction methods, such as laser surgeries including photorefractive keratectomy (PRK), laser‐assisted in situ keratomileusis (LASIK), and laser epithelial keratomileusis (LASEK), can drastically improve eyesight so that the quality of life of patients with myopia can be improved. However, optimal indications for these procedures remain controversial because of the limitations of current evidence.

Description of the intervention

Spectacles and contact lenses are the modalities used most often for correction of blurred vision due to myopia. However, not all users find them easy to wear or maintain, or both, and several limitations and complications have been reported among wearers (Foulks 2006). Surgical treatment, another option, aims to overcome the limitations of spectacles and contact lenses. Surgical procedures that involve operating on the cornea with a laser are known as excimer laser refractive surgery and include two main procedure groups: LASIK and surface treatments (PRK and LASEK).

In PRK, the first surface treatment, the ultraviolet beam generated by an argon fluoride (ArF) excimer laser, is irradiated to the corneal stroma after removal of epithelium to change the curvature of the cornea and to correct myopia; a contact lens may then be used. This method was investigated in human eyes in the 1980s and therefore was the first method of corneal surface ablation used for correction of myopia (Goodman 1989; Munnerlyn 1988). Over subsequent decades, the procedure and the laser technology used have been improved substantially.

LASIK, the next important method of excimer laser refractive surgery to be developed, rapidly became the dominant refractive procedure, eclipsing PRK by offering the advantages of faster visual recovery, reduced postoperative pain, and less stromal haze. In LASIK, a microkeratome (or femtosecond laser) is used to raise a corneal flap; the flap is replaced after laser ablation (Pallikaris 1990).

LASEK, as a modification of PRK, was introduced in 1999 by Camelin (Camelin 1999). In LASEK, an epithelial flap is first created by dilute ethanol and then is replaced after the corneal stroma is ablated by the laser. The corneal epithelium is left intact; therefore, LASEK is expected to offer the advantages of both LASIK and PRK (Taneri 2004).

How the intervention might work

Excimer laser refractive surgery has became popular over the past 20 years. As the first excimer laser procedure, PRK has proved predictable, effective, and safe for the treatment of patients with low to moderate myopia (Gartry 1992; Seiler 1991), and it was granted US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval before LASIK was approved. However, LASIK is currently the dominant refractive procedure performed for correction of myopia (Shortt 2012). Reasons for the rapid shift from PRK to LASIK include mainly faster visual recovery and fewer perceived complications, including a lower incidence of stromal haze and less postoperative pain and discomfort with the LASIK method, in which the central epithelium is left intact (El‐Maghraby 1999; Rosman 2010; Shortt 2012; Sugar 2002).

LASEK is a surface ablation procedure that has different characteristics from LASIK. LASIK offers the advantages of less pain and quicker visual recovery and is a better option for correction of high myopia (Shortt 2012). LASEK is less invasive because a thinner epithelial flap is created (Pallikaris 2001), which may reduce the risk of corneal ectasia (a condition in which the cornea is thinner and internal pressure within the eyeball can cause expansion or distention of the cornea) and the flap‐ or interface‐related complications of LASIK (Seiler 1998). LASEK can be considered as an alternative for myopic patients with thin corneas (Hashemi 2004b; O'Keefe 2010). Researchers found no significant differences in postoperative visual outcomes and complication rates between LASIK and LASEK (Kirwan 2009). In addition, LASEK has been proved to induce fewer high‐order aberrations compared with LASIK and thus may be used better in customized ablation (Dastjerdi 2002; Kirwan 2009). However, evidence reported by randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing these procedures is scarce.

LASEK and PRK are the surface treatments most commonly used for correction of myopia (Taneri 2011). In many previous studies, LASEK was shown to offer some advantages over PRK, such as less postoperative pain, less postoperative stromal haze formation, and faster visual recovery due to replacement of the epithelial flap, which prevents a large postoperative epithelial defect (Autrata 2003; Azar 2001; Lee 2001; O'Keefe 2010; Saleh 2003; Yee 2004; Zhao 2010) or significant decrease in endothelial cell counts (Burka 2008). However, the thinner flap used in LASEK introduces potential risk of postoperative displacement, which may induce greater pain. In addition, the risk of stromal haze formation may not be lower with LASEK than with PRK. Many studies have failed to show advantages of LASEK over PRK (Bower 2007; Cui 2008; Hashemi 2004a; Higgins 2011; Lee 2005; O'Doherty 2007; Pirouzian 2004; Pirouzian 2006). Some trials have even shown conflicting results for postoperative pain when comparing PRK with LASEK (Ghadhfan 2007; Ghanem 2008; Ghirlando 2007; Saleh 2003).

Why it is important to do this review

Rapid advancement in the technology of refractive surgery for myopia has led to the emergence of new methods, but their real advantages over previous techniques have not been fully identified. Previously published Cochrane reviews have not address this review's objectives. Other Cochrane reviews have investigated interventions to slow progression of myopia in children (Walline 2011; Wei 2011), compared LASIK with PRK for myopia (Shortt 2012), and laser photocoagulation for choroidal neovascularization in pathologic myopia (Virgili 2005). Also, a Cochrane protocol comparing LASIK with LASEK for myopia has been published and the systematic review is underway (Kuryan 2014). Inconsistencies among the different techniques and their relative benefits and harms, as shown in different studies, warrant a systematic review. The finding by this review of differences in efficacy and safety when PRK was compared with LASEK will be useful for healthcare professionals and will allow them to make informed decisions about the most effective surface treatment for correcting various levels of myopia.

Objectives

The objective of this review is to compare LASEK versus PRK for correction of myopia by evaluating their efficacy and safety in terms of postoperative uncorrected visual acuity, residual refractive error, and associated complications.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included in this review only randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Types of participants

We included participants 18 years of age or older undergoing LASEK or PRK for any degree of myopia and up to 3 D of astigmatism. We excluded participants who had significant co‐existing ocular or systematic diseases that may affect refractive status or wound healing, or who had a history of previous ocular surgeries.

Types of interventions

We included trials in which LASEK was compared with PRK for correction of myopia.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Proportion of eyes with uncorrected visual acuity (UCVA) of 20/20 or better at 12 months post treatment.

Proportion of eyes within ± 0.50 D of target refraction at 12 months post treatment.

Proportion of eyes that lost one or more lines of best spectacle‐corrected visual acuity (BSCVA) at six months post treatment or longer.

Secondary outcomes

Postoperative mean spherical equivalent at one week and at one, three, six, and 12 months post treatment.

Proportion of eyes with UCVA of 20/20 or better at one week and one, three, and six months post treatment.

Proportion of eyes within ± 0.50 D of target refraction at one week and one, three, and six months post treatment.

Epithelial healing time.

Postoperative pain scores at one, two, three and seven or more days.

Adverse outcomes

Corneal haze score at one, three, and six months post treatment or longer.

Glare and halo scores at one, three, and six months or longer post treatment.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched CENTRAL (which contains the Cochrane Eyes and Vision group Trials Register) (2015 Issue 12), Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid MEDLINE In‐Process and Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE Daily, Ovid OLDMEDLINE (January 1946 to December 2015), EMBASE (January 1980 to December 2015), Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences (LILACS) (January 1982 to December 2015), the ISRCTN registry (www.isrctn.com/editAdvancedSearch), ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov) and the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (www.who.int/ictrp/search/en). We did not use any date or language restrictions in the electronic searches for trials. We last searched the electronic databases on 15 December 2015.

See Appendices for details of search strategies for CENTRAL (Appendix 1), MEDLINE (Appendix 2), EMBASE (Appendix 3), LILACS (Appendix 4), ISRCTN (Appendix 5), ClinicalTrials.gov (Appendix 6), and the ICTRP (Appendix 7).

Searching other resources

We used the Science Citation Index to find reports that cited the trials included in this review. We searched the reference lists of included trials to identify additional relevant trials. We did not contact pharmaceutical companies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Three review authors (SML, HAL, SYL) independently screened the titles and abstracts of all reports identified by electronic and manual searches and obtained full‐text copies of potentially relevant trials. Four review authors (SML, HAL, SYL, JH) independently assessed the full‐text articles according to definitions provided in the Criteria for considering studies for this review section. We assessed only trials that met these criteria for methodological quality. If eligibility was unclear because insufficient information was provided in the report, we contacted the trial investigators to ask for additional information. Review authors were unmasked to trial authors, institutions, and trial results during the assessment. We resolved disagreements by carrying on discussions or by seeking the opinion of a third review author (XXP). We provided reasons for exclusion of excluded studies in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Data extraction and management

Our research team, consisting of experts from ophthalmology, clinical epidemiology, and evidence‐based medicine, developed a standard data extraction form. This form included the following items.

Method: duration, randomization technique, allocation concealment method, masking (participants, provider, outcome assessors), methods of analyzing outcomes, country, setting.

Participants: sampling (random/convenience), numbers in comparison groups, age, sex, similarity of groups at baseline, withdrawals/losses to follow‐up (reason), subgroups.

Interventions: interventions (details of procedure), comparison interventions (details of procedures), co‐medications (dose, route, duration).

Outcomes: outcomes specified above, other outcomes assessed, other events, times of assessment, length of follow‐up.

Notes: general information such as publication status, title, authors, source, contact address, language of publication, year of publication, funding sources.

Two review authors independently entered the data into Epidata 3.1 using the double‐data entry facility to verify the data. We first transferred the data from Epidata to Excel and then copied the data to Revman 5 (software developed by Cochrane; RevMan 2014) for analysis. We resolved differences in data extraction or entry by reaching consensus and referring back to the original article.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (SML, JH) independently assessed the methodological quality of included trials according to Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We graded each trial for each above mentioned item as we assessed the risk of bias of included trials using the following set parameters and graded them as "Low risk," "High risk," or "Unclear risk."

Selection bias: We considered a randomization procedure "Low risk" if it involved a computer random number generator, a random number table, coin tossing, throwing dice, or shuffling cards or envelopes. We considered non‐random approaches such as sequence generated by alternation, case record number, date of birth, date (or day) of admission, day of week, availability of the intervention, preference of participants, judgment of the clinician, or laboratory tests to be "High risk" and excluded these studies. If information about the sequence generation process was not sufficient, we considered this "Unclear risk."

Selection bias: We considered allocation concealment "Low risk" if it involved centralized or pharmacy‐controlled randomization, serially administered prenumbered or coded identical containers, or allocation by locked on‐site computers or opaque, sealed envelopes. We considered an open random allocation schedule or other explicitly unconcealed procedures for allocation to be "High risk." If the method of concealment was not described or was not described in sufficient detail, we considered this to show "Unclear risk."

Performance bias: We considered successful masking (blinding) of participants and study personnel, or no masking or incomplete masking, for which review authors judged that the outcome was not influenced to be "Low risk." We considered unsuccessful masking or no masking that influenced the outcome measurement to be "High risk." We considered insufficient information for judgment to indicate "Unclear risk."

Attrition bias: We examined the completeness of outcome data for each main outcome, rates of follow‐up, and reasons for loss to follow‐up. We considered no missing outcome data or missing data that did not influence the true estimate as "Low risk"; otherwise we assigned it "High risk." We considered insufficient information for judgment to indicate "Unclear risk."

Reporting bias: We examined whether the trial reported selective outcomes. If a trial reported all prespecified outcomes described in the protocol or clinical trial register record, we judged it "Low risk"; otherwise, we assigned it "High risk." When the trial protocol or clinical trial register record was not available for comparison, we assigned it "Unclear risk."

Other potential bias: We examined the source of funding and conflicts of interest. If a trial reported no conflict of interest, we assigned it "Low risk"; otherwise, it was "High risk." We considered insufficient information for judgment to indicate "Unclear risk." We did not state in the protocol that we were going to assess "other potential bias" (see Differences between protocol and review).

We contacted trial authors for clarification of any aspect graded as "Unclear risk." If trial authors did not respond within eight weeks, we graded the trial on the basis of available information. We resolved discrepancies by discussion or by consultation with a third party.

Measures of treatment effect

We calculated the risk ratio (RR) for outcome measures reported as dichotomous data (target refraction, UCVA, BSCVA, etc.). We used standard mean deviation (SMD) for assessment of pain scores because different scales were used in the trials included in this review. If more trials were included in the future, measures were continued, and the same scale was used across trials, we would calculate mean differences (MDs).

Unit of analysis issues

All included trials used a paired‐eye design, except one trial (Rooij 2003). Rooij 2003 used a parallel‐group design, but enrolled both eyes of some participants and did not report whether both eyes of all or some participants were allocated to the same intervention group. None of the trials used the correct analysis to account for the intra‐person correlations for individual outcomes. We analyzed data by using each eye as the individual unit of analysis and discussed the limitations associated with this method.

Dealing with missing data

When data were missing in a trial report, we contacted the original trial investigators for clarification and further information. If we did not receive a response within eight weeks, we used imputation methods to determine missing standard deviations (SDs), as described in Chapter 16 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We did not use the software Get Data Graph Digitizer 2.24 (http://getdata‐graph‐digitizer.com) to estimate data that were only illustrated in figures, as this was not needed.

We assessed the number of participants excluded or lost to follow‐up in both treatment arms for all trials. We did not impute missing participant data for the purposes of this review. We address in the Discussion section the potential impact of missing data on study findings.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed clinical and methodological heterogeneity by comparing study methods, participant characteristics, and outcome measures across studies. When no substantial clinical or methodological heterogeneity was identified, we combined study data and assessed statistical heterogeneity by using the I2 statistic and examining forest plots. We considered an I2 value of 50% or greater and poor overlap of individual trial confidence intervals to indicate substantial statistical heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We did not investigate publication bias by using funnel plots because no meta‐analysis included 10 or more trials. We assessed potential selective outcome reporting as part of the 'Risk of bias' assessment for individual trials.

Data synthesis

If we noted statistical heterogeneity, we first checked the data entered into RevMan for errors. If the data were correct and we noted inconsistency in the direction of effects, we did not incorporate the data into the meta‐analysis. We were not able to explore sources of heterogeneity by performing subgroup analyses, as sufficient data were not available. We used the random‐effects model when the analysis included three or more trials, and the fixed‐effect model when fewer than three trials were included in a meta‐analysis.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We were not able to perform subgroup analysis based on the type of laser platform used, as insufficient trials were included in each meta‐analysis. Subgroup analysis for the range of myopia corrected was not possible, as only participants with low to moderate myopia were included in these trials.

Sensitivity analysis

When we extracted data for pain scores, we noted that one trial did not report the SD for pain scores (Pirouzian 2004). We therefore used the average of other trials to approximate the SDs for this trial. We performed sensitivity analysis by excluding the trial with imputed data.

Summary of findings

We provided a 'Summary of findings' table that includes assumed risk and corresponding risk for relevant outcomes based on risk across control groups in the included trials. We graded the overall quality of evidence for each outcome by using the GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) classification (www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). We assessed the quality of evidence for each outcome as "high," "moderate," "low," or "very low" in accordance with the following criteria as described in Chapter 12 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Schünemann 2011).

High risk of bias among included trials.

Indirectness of evidence.

Unexplained heterogeneity or inconsistency of results.

Imprecision of results (i.e. wide confidence intervals or confidence intervals that do not rule out possible effects).

High probability of reporting bias.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

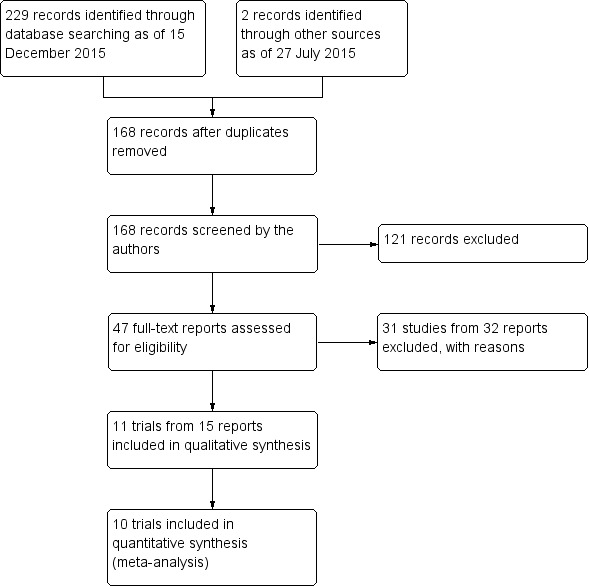

An electronic search of the databases as of 15 December 2015 yielded a total of 229 records (Figure 1). On 27 July 2015, we searched the Science of Citation Index, which yielded two additional records. We removed 63 duplicate records, leaving 168 unique records to be screened. We retrieved and assessed 47 potentially relevant full‐text reports. We excluded from this review 31 studies (from 32 reports) and included 11 trials (from 15 reports). One included trial was available only as a conference abstract report (Rooij 2003).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Type of participants

We included 11 trials that enrolled a total of 428 adult participants with low to moderate myopia (Autrata 2003; Eliacik 2015; Ghanem 2008; Ghirlando 2007; Hashemi 2004a; He 2004; Lee 2001; Litwak 2002; Pirouzian 2004; Rooij 2003; Saleh 2003). Each trial included between 14 and 92 participants. These trials were conducted in the Czech Republic, Brazil, Italy, Iran, China, Korea, Mexico, Turkey, USA, and UK. Preoperative refraction of participants ranged from ‐2.04 to ‐4.90 D in the LASEK group, and from ‐2.27 to ‐4.78 D in the PRK group. Ten of 11 trials included both eyes of each participant and followed a paired‐eye design, while one trial included one or two eyes per participant and followed a parallel‐group design. Study periods spanned from April 1999 to October 2005 and included follow‐up between 48 hours and 24 months.

Type of interventions

Six types of excimer laser were used among the 11 trials. Five trials used Nidek EC‐5000 (Autrata 2003; Hashemi 2004a; He 2004; Litwak 2002; Saleh 2003), one trial used MEL 70 G‐scan (Ghanem 2008), one trial used InPro Laser (Ghirlando 2007), one trial used Keratome II excimer laser (Lee 2001), two trials used VISX Star 3 (Eliacik 2015; Pirouzian 2004), and one trial used the Keratocor 217 floating spot excimer laser (Rooij 2003). Treatment zones also varied among trials. All participants underwent LASEK in one eye and PRK in the other eye, except in Ghanem 2008, which used butterfly LASEK instead of conventional LASEK. In Butterfly LASEK, the epithelium is dissected to create two symmetric epithelial flaps as compared with one epithelial flap in conventional LASEK.

Type of outcomes

Data from Rooij 2003 were published only as an abstract and reported none of the outcomes assessed in this review. Each of the remaining 10 trials reported at least one outcome included in this review.

Visual acuity outcomes

Six trials reported the proportion of eyes in each group with UCVA of 20/20 or better for at least one follow‐up time point (Eliacik 2015; Ghanem 2008; Ghirlando 2007; Hashemi 2004a; He 2004; Lee 2001). One trial reported the proportion of eyes in each group that lost one or more lines of BSCVA at 12 months (Ghanem 2008).

Refraction outcomes

Four trials reported the proportion of eyes in each group within ± 0.50 D of target refraction for at least one follow‐up time point (Eliacik 2015; Ghanem 2008; Ghirlando 2007; Hashemi 2004a).

Spherical equivalent outcomes

Seven trials reported the mean spherical equivalent in each group for at least one follow‐up time point (Autrata 2003; Eliacik 2015; Ghanem 2008; Ghirlando 2007; Hashemi 2004a; He 2004; Lee 2001).

Epithelial healing time

Six trials reported data for epithelial healing time within one week post treatment (Autrata 2003; Eliacik 2015; Ghirlando 2007; Hashemi 2004a; Lee 2001; Litwak 2002).

Pain score outcomes

Five trials reported data for pain scores up to three days post treatment (Autrata 2003; Ghanem 2008; Hashemi 2004a; Pirouzian 2004; Saleh 2003).

Adverse outcomes

Five trials reported postoperative corneal haze scores (Autrata 2003; Ghanem 2008; Ghirlando 2007; He 2004; Lee 2001), and one trial reported postoperative glare and halo scores (Hashemi 2004a).

Excluded studies

We excluded 31 studies after review of full‐text reports: 17 studies were not RCTs, four studies included participants not eligible for the review, and 10 studies did not compare LASEK versus PRK. We provided detailed reasons for exclusion of each trial in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Risk of bias in included studies

We have shown in Figure 2 summarized risk of bias assessments for the included trials.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Random sequence generation

Three of the 11 included trials used an adequate method of randomization, including drawing of lots (Ghanem 2008) and block randomization (Hashemi 2004a; Pirouzian 2004). The remaining eight trials did not describe the method of randomization used, and we judged these trials to be at unclear risk of bias.

Allocation concealment

Two of the 11 included trials used adequate methods to conceal the treatment allocation, including drawing of lots (Ghanem 2008) and sealed envelopes (Saleh 2003) to assign treatment groups. We judged the remaining nine trials to be at unclear risk of bias as the authors did not describe how treatment allocation was concealed.

Masking (performance bias and detection bias)

Performance bias

We judged two of the 11 included trials to be at low risk of bias, as participants were adequately masked to the treatment given to each eye (Ghanem 2008; Pirouzian 2004). Lee 2001 did not mask participants because this was incompatible with the explanation of procedures given to participants to obtain informed consent, and we judged the trial to be at high risk of bias. Eight trials did not clearly describe how participants were masked, and we judged them to be at unclear risk of bias (Autrata 2003; Eliacik 2015; Ghirlando 2007; Hashemi 2004a; He 2004; Litwak 2002; Rooij 2003; Saleh 2003).

Detection bias

We judged four of the 11 included trials to be at low risk of bias, as outcome assessors were adequately masked (Ghanem 2008; Hashemi 2004a; Pirouzian 2004; Saleh 2003). Lee 2001 did not mask the outcome assessors, and we judged this trial to be at high risk of bias. Six of 11 trials did not clearly describe whether outcome assessors were masked. Therefore we judged them to be at unclear risk of bias (Autrata 2003; Eliacik 2015; Ghirlando 2007; He 2004; Litwak 2002; Rooij 2003)

Incomplete outcome data

We graded eight of the 11 included trials at low risk of bias as the quantity of incomplete outcome data was minimal (Eliacik 2015; Ghanem 2008; Ghirlando 2007; He 2004; Lee 2001; Litwak 2002; Pirouzian 2004; Saleh 2003). We graded Autrata 2003 and Hashemi 2004a at high risk of bias for two different reasons. While Autrata 2003 excluded only 8% of participants, all excluded participants had received LASEK treatment and had epithelial flap disintegration, which might be associated with the review outcomes. Hashemi 2004a excluded a large portion of participants (23.8%) as they were lost to follow‐up at three months. Rooij 2003 did not report the quantity of missing data, and we graded this trial at unclear risk of bias.

Selective reporting

We judged all trials to be at unclear risk of bias because none of the trial investigators reported a protocol or trial register record. Therefore, we were unable to compare the reported outcomes with the protocol or trial register record.

Other potential sources of bias

We graded seven of 11 trials at low risk of bias because they were not industry funded and reported no conflicts of interest. The remaining four trials did not report their source of funding and revealed no conflicts of interest. Therefore we graded these trials at unclear risk of bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Rooij 2003 published data only as an abstract and reported none of the review outcomes; therefore, we did not include data from Rooij 2003 in any of our analyses. No trial reported a power calculation with target sample size, except for Hashemi 2004a, which reported a power calculation but did not reveal the target sample size. Thus, caution must be taken in interpreting the results, as the number of participants may be inadequate to show differences between treatment groups for many outcomes. Overall, we graded most trials at unclear risk of bias. However, as the result of imprecision, inconsistency, and potential reporting bias, we graded the quality of the evidence from very low to moderate.

Primary outcomes

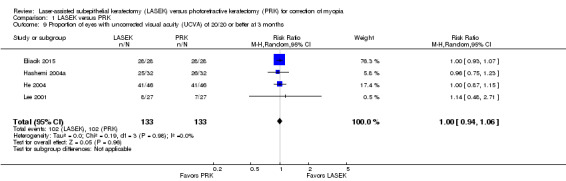

Proportion of eyes with UCVA of 20/20 or better

At 12 months post treatment, one trial assessed this outcome (Ghanem 2008). In the butterfly LASEK group, 49 of 51 eyes had UCVA of 20/20 or better at 12‐month follow‐up compared with 50 of 51 eyes in the PRK group (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.05). Although the CI suggests little to no effect difference between groups, we judged the quality of the evidence to be low because we downgraded for two levels of potential reporting bias (‐2).

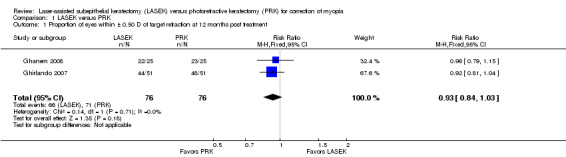

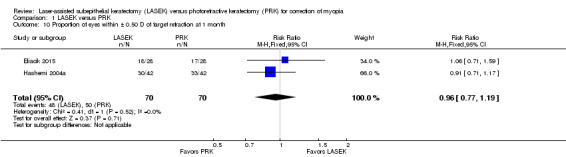

Proportion of eyes within ± 0.50 D of target refraction

At 12 months post treatment, two trials assessed this outcome (Ghanem 2008; Ghirlando 2007). Effect size and interval suggest no difference or possibly a small effect in favor of PRK over LASEK (RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.03; Analysis 1.1). We judged the quality of the evidence as low as the result of imprecision (‐1) and potential reporting bias (‐1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 LASEK versus PRK, Outcome 1 Proportion of eyes within ± 0.50 D of target refraction at 12 months post treatment.

Proportion of eyes that lost one or more lines of BSCVA

At 12 months post treatment, one trial reported this outcome (Ghanem 2008). One of 51 eyes in the butterfly LASEK group lost one or more lines of BSCVA compared with none of the 51 eyes in the PRK group (RR 3.00, 95% CI 0.13 to 71.96). We judged the quality of the evidence as very low because we downgraded for two levels of potential reporting bias (‐2) and imprecision (‐1).

No trial reported this outcome at six months post treatment or at other follow‐up time points.

Secondary outcomes

Postoperative mean spherical equivalent

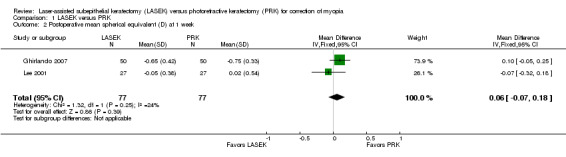

At one week post treatment, two trials with 154 eyes reported this outcome (Ghirlando 2007; Lee 2001). We pooled the data using a fixed‐effect model, as fewer than three trials were identified and little statistical heterogeneity was indicated (I2 = 24%). On the basis of these two trials, the mean difference in mean spherical equivalent between LASEK and PRK is within ± 0.50 D (MD 0.06 D, 95% CI ‐0.07 to 0.18; Analysis 1.2). We judged the quality of the evidence as moderate as the result of potential reporting bias (‐1).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 LASEK versus PRK, Outcome 2 Postoperative mean spherical equivalent (D) at 1 week.

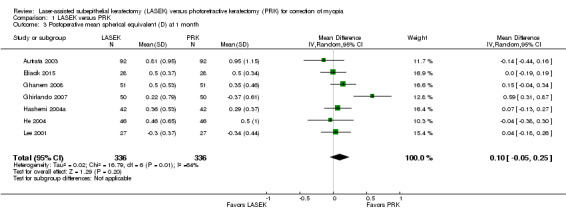

At one month post treatment, seven trials reported this outcome for 672 eyes (Autrata 2003; Eliacik 2015; Ghanem 2008; Ghirlando 2007; Hashemi 2004a; He 2004; Lee 2001). Although substantial statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 64%) was indicated, we pooled the data using a random‐effects model, as confidence intervals from all but one trial showed a high degree of overlap. The mean difference when LASEK was compared with PRK was very small and suggests no clinically meaningful difference (MD 0.10 D, 95% CI ‐0.05 to 0.25; Analysis 1.3). We judged the quality of the evidence as moderate as the result of inconsistency (‐1).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 LASEK versus PRK, Outcome 3 Postoperative mean spherical equivalent (D) at 1 month.

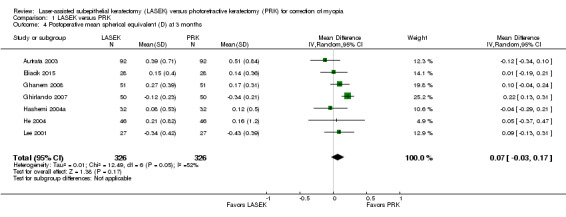

At three months post treatment, seven trials reported this outcome for 652 eyes (Autrata 2003; Eliacik 2015; Ghanem 2008; Ghirlando 2007; Hashemi 2004a; He 2004; Lee 2001). Although moderate statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 52%) was indicated, we pooled the data using a random‐effects model, as confidence intervals from all but one trial showed a high degree of overlap. The mean difference when LASEK was compared with PRK was very small and suggests no clinically meaningful difference (MD 0.07 D, 95% CI ‐0.03 to 0.17; Analysis 1.4). We judged the quality of the evidence to be moderate as the result of inconsistency (‐1).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 LASEK versus PRK, Outcome 4 Postoperative mean spherical equivalent (D) at 3 months.

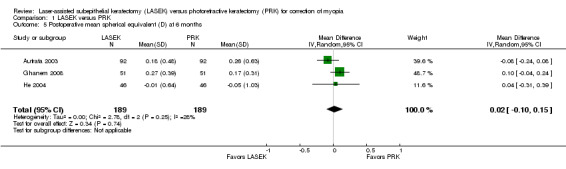

At six months post treatment, three trials reported this outcome for 378 eyes (Autrata 2003; Ghanem 2008; He 2004). Minimal statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 28%) was indicated and no clinically meaningful difference was found when LASEK was compared with PRK (MD 0.02 D, 95% CI ‐0.10 to 0.15; Analysis 1.5). We judged the quality of the evidence to be moderate as the result of potential reporting bias (‐1).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 LASEK versus PRK, Outcome 5 Postoperative mean spherical equivalent (D) at 6 months.

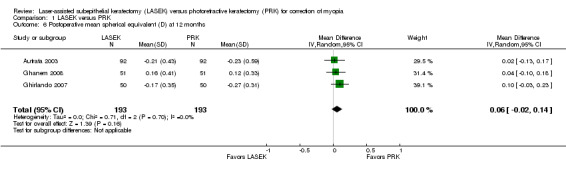

At 12 months post treatment, data for this outcome were available from three trials (Autrata 2003; Ghanem 2008; Ghirlando 2007). No statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 0%) was indicated and no clinically meaningful differences were found when LASEK was compared with PRK (MD 0.06 D, 95% CI ‐0.02 to 0.14; Analysis 1.6). We judged the quality of the evidence to be moderate as the result of potential reporting bias (‐1).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 LASEK versus PRK, Outcome 6 Postoperative mean spherical equivalent (D) at 12 months.

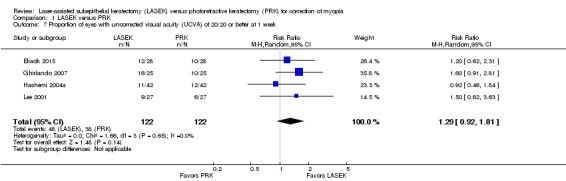

Proportion of eyes with UCVA of 20/20 or better

At one week post treatment, four trials reported this outcome for 244 eyes (Eliacik 2015; Ghirlando 2007; Hashemi 2004a; Lee 2001). Effects were consistent, as indicated by the I2 value (0%) and suggest no difference between groups or that LASEK may result in more eyes with UCVA of 20/20 or better at one week compared with PRK (RR 1.29, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.81; Analysis 1.7). We judged the quality of the evidence to be moderate as the result of imprecision (‐1).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 LASEK versus PRK, Outcome 7 Proportion of eyes with uncorrected visual acuity (UCVA) of 20/20 or better at 1 week.

At one month post treatment, five trials reported this outcome for 336 eyes (Eliacik 2015; Ghirlando 2007; Hashemi 2004a; He 2004; Lee 2001). Effects were consistent, as indicated by the I2 value (16%) and suggest that LASEK and PRK may be comparable with respect to this outcome, or may possibly favor PRK (RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.08; Analysis 1.8). We judged the quality of the evidence to be moderate as the result of imprecision (‐1).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 LASEK versus PRK, Outcome 8 Proportion of eyes with uncorrected visual acuity (UCVA) of 20/20 or better at 1 month.

At three months post treatment, four trials reported this outcome for 266 eyes (Eliacik 2015; Hashemi 2004a; He 2004; Lee 2001). Effects were consistent, as indicated by the I2 value (0%) and suggest no differences between groups (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.06; Analysis 1.9). We judged the quality of the evidence to be moderate as the result of imprecision (‐1).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 LASEK versus PRK, Outcome 9 Proportion of eyes with uncorrected visual acuity (UCVA) of 20/20 or better at 3 months.

At six months post treatment, only one trial reported this outcome (He 2004). In the LASEK group, 40 of 46 eyes had UCVA of 20/20 or better compared with 36 of 46 eyes in the PRK group (RR 1.11, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.34). We judged the quality of the evidence to be very low as the result of potential reporting bias (‐2) and imprecision (‐1).

Proportion of eyes within ± 0.50 D of target refraction

None of the included trials reported this outcome at one week or six months post treatment.

At one month post treatment, two trials reported this outcome for 140 eyes (Eliacik 2015; Hashemi 2004a). Confidence intervals for these trials overlapped, and the I2 value was 0%. The effect estimate when LASEK was compared with PRK was imprecise; this indicates uncertainty about difference between treatments for this outcome (RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.19; Analysis 1.10). We judged the quality of the evidence to be low as a result of this imprecision (‐1) and potential reporting bias (‐1).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 LASEK versus PRK, Outcome 10 Proportion of eyes within ± 0.50 D of target refraction at 1 month.

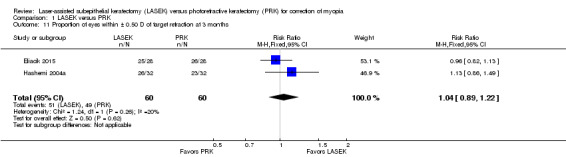

At three months post treatment, the same two trials reported this outcome for 120 eyes (Eliacik 2015; Hashemi 2004a). The effect estimate when LASEK was compared with PRK was imprecise; this indicates uncertainty about differences between treatments for this outcome (RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.22; Analysis 1.11). We judged the quality of the evidence to be low as a result of this imprecision (‐1) and potential reporting bias (‐1).

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 LASEK versus PRK, Outcome 11 Proportion of eyes within ± 0.50 D of target refraction at 3 months.

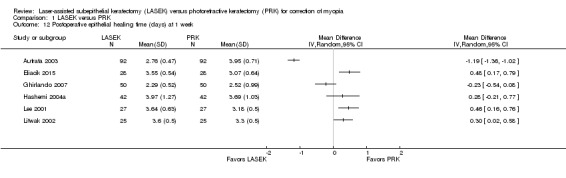

Postoperative epithelial healing time

Six trials reported data for epithelial healing time within one week post treatment (Autrata 2003; Eliacik 2015; Ghirlando 2007; Hashemi 2004a; Lee 2001; Litwak 2002). We did not combine these data in the meta‐analysis, as the direction of effects was inconsistent and statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 97%) among trials was considerable. Five trials showed that the difference in epithelial healing time between LASEK and PRK groups was less than one day; however, one trial reported that epithelial healing time may be up to one day shorter in the LASEK group than in the PRK group (MD ‐1.19 days, 95% CI ‐1.36 to ‐1.02, 92 participants; Analysis 1.12). We judged the quality of the evidence to be low as a result of imprecision (‐1) and inconsistency (‐1).

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 LASEK versus PRK, Outcome 12 Postoperative epithelial healing time (days) at 1 week.

Postoperative pain score

We did not combine data for pain scores at any time point, as statistical heterogeneity among trials was considerable. Five trials reported pain scores at any time point and used different scales to assess pain. For all scales, a lower score represented less pain and a higher score represented more pain. None of the included trials reported this outcome at seven days or longer post treatment.

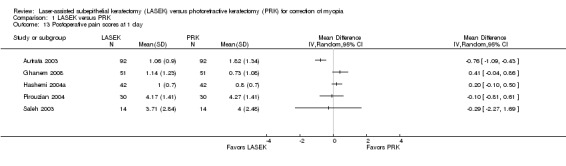

At one day post treatment, statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 83%) among five trials reporting this outcome was considerable and directions of effect from individual trials were inconsistent (Analysis 1.13). Four of five trials showed little or no difference between LASEK and PRK (Ghanem 2008; Hashemi 2004a; Pirouzian 2004; Saleh 2003). One trial reported lower pain scores in the LASEK group than in the PRK group on a scale of 0 to 3 (Autrata 2003). We judged the quality of the evidence to be low as a result of imprecision (‐1) and inconsistency (‐1).

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 LASEK versus PRK, Outcome 13 Postoperative pain scores at 1 day.

At two days post treatment, statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 79%) among four trials was considerable and directions of effect from individual trials were inconsistent (Analysis 1.14). Three of four trials showed little or no difference between LASEK and PRK (Ghanem 2008; Pirouzian 2004; Saleh 2003). One trial reported lower pain scores in the LASEK group than in the PRK group on a scale of 0 to 3 (Autrata 2003). We judged the quality of the evidence to be low as the result of imprecision (‐1) and inconsistency (‐1).

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 LASEK versus PRK, Outcome 14 Postoperative pain scores at 2 days.

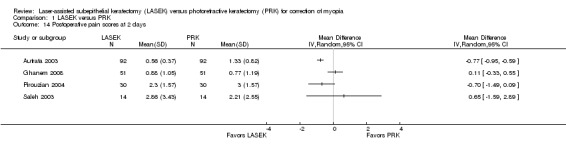

At three days post treatment, statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 73%) among three trials was substantial and directions of effect from individual trials were inconsistent (Analysis 1.15). Two of three trials showed little or no difference between LASEK and PRK (Ghanem 2008; Pirouzian 2004). One trial reported lower pain scores in the LASEK group than in the PRK group on a scale of 0 to 3 (Autrata 2003). We judged the quality of the evidence to be very low as a result of imprecision (‐1), inconsistency (‐1), and potential reporting bias (‐1).

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 LASEK versus PRK, Outcome 15 Postoperative pain scores at 3 days.

Adverse outcomes

Postoperative corneal haze score

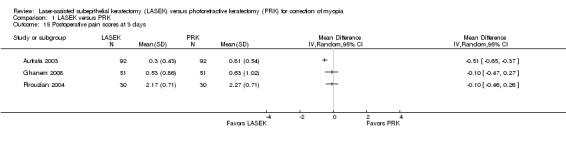

We did not combine data in meta‐analysis, as the direction of effects from each trial was inconsistent and showed substantial statistical heterogeneity (I2 > 50%). Each trial that reported this outcome showed a very small difference between LASEK and PRK in corneal haze scores at one, three, and six months.

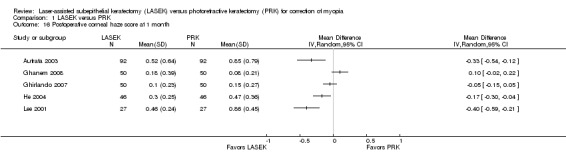

At one month post treatment, five trials reported this outcome (Analysis 1.16). Two trials reported little or no difference in postoperative corneal haze scores between LASEK and PRK (Ghanem 2008; Ghirlando 2007), and three trials reported lower postoperative corneal haze scores in the LASEK group than in the PRK group (Autrata 2003; He 2004; Lee 2001). However, absolute differences for all trials were within 1 point, suggesting no clinically important difference between groups. We judged the quality of the evidence to be moderate as the result of inconsistency (‐1).

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 LASEK versus PRK, Outcome 16 Postoperative corneal haze score at 1 month.

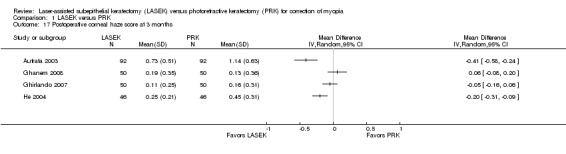

At three months post treatment, four trials reported this outcome (Analysis 1.17). Two trials reported little or no difference in postoperative corneal haze scores between LASEK and PRK (Ghanem 2008; Ghirlando 2007), and two trials reported lower postoperative corneal haze scores in the LASEK group than in the PRK group (Autrata 2003; He 2004). However, absolute differences for all trials were within 1 point, suggesting no clinically important difference between groups. We judged the quality of the evidence to be moderate as the result of inconsistency (‐1).

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1 LASEK versus PRK, Outcome 17 Postoperative corneal haze score at 3 months.

At six months post treatment, four trials reported this outcome (Analysis 1.18). Two trials reported little or no difference in postoperative corneal haze scores between LASEK and PRK (Ghanem 2008; Ghirlando 2007), and two trials reported lower postoperative corneal haze scores in the LASEK group than in the PRK group (Autrata 2003; He 2004). However, absolute differences for all trials were within 1 point, suggesting no clinically important difference between groups. We judged the quality of the evidence to be moderate as the result of inconsistency (‐1).

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1 LASEK versus PRK, Outcome 18 Postoperative corneal haze score at 6 months.

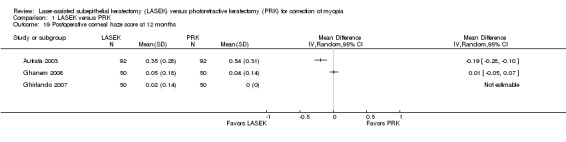

At 12 months post treatment, three trials reported this outcome (Analysis 1.19). Ghanem 2008 showed little or no difference in corneal haze score, and Autrata 2003 reported that corneal haze scores were lower in the LASEK group than in the PRK group. Ghirlando 2007 did not report analyzable data for the PRK group, so we could not estimate the treatment effect for this trial. We judged the quality of the evidence to be very low as the result of imprecision (‐1), inconsistency (‐1), and potential reporting bias (‐1).

1.19. Analysis.

Comparison 1 LASEK versus PRK, Outcome 19 Postoperative corneal haze score at 12 months.

At 24 months post treatment, only Autrata 2003 reported this outcome. The mean corneal haze score of 0.21 (SD 0.24) for 92 eyes in the LASEK group and 0.43 (SD 0.29) for 92 eyes in the PRK group suggests a smaller but clinically unimportant difference in score for LASEK compared with PRK (MD ‐0.22, 95% CI ‐0.30 to ‐0.14). We judged the quality of the evidence to be low as we downgraded two levels for potential reporting bias (‐2).

Postoperative glare and halo scores

Only one trial reported data for postoperative glare and halo scores (Hashemi 2004a).

At one month post treatment, differences in glare scores (MD ‐0.17, 95% CI ‐0.63 to 0.29, 42 eyes in each group) and halo scores (MD ‐0.09, 95% CI ‐0.66 to 0.48, 42 eyes in each group) between LASEK and PRK were uncertain. We judged the quality of the evidence to be very low for these outcomes as we downgraded for imprecision (‐1) and two levels for potential reporting bias (‐2).

At three months post treatment, differences in glare scores (MD ‐0.04, 95% CI ‐0.61 to 0.53, 32 eyes in each group) and halo scores (MD ‐0.09, 95% CI ‐0.72 to 0.54, 32 eyes in each group) between LASEK and PRK were uncertain. We judged the quality of the evidence to be very low for these outcomes as we downgraded for imprecision (‐1) and two levels for potential reporting bias (‐2).

Discussion

Summary of main results

In this review of 11 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that enrolled 428 participants with low to moderate myopia, we found uncertainty as to differences in efficacy, accuracy, and adverse effects between laser epithelial keratomileusis (LASEK) and photorefractive keratectomy (PRK). We found no reports comparing LASEK versus PRK in participants with high myopia. Ten of 11 trials used a paired‐eye design, while one trial used parallel‐group design. PRK was performed by mechanical removal of the epithelial layer and the central Bowman layer of cornea. LASEK, however, was performed with dilute alcohol and with the epithelial layer intact.

Only one trial reported postoperative uncorrected visual acuity (UCVA) of 20/20 or better at 12 months (Ghanem 2008). This trial did not show evidence of a difference between the two procedures for this outcome. Up to four other trials reported this outcome at other time points (one week, one month, three months, and six months) and found no evidence of a treatment difference with respect to UCVA of 20/20 or better.

The treatment effect for accuracy outcomes was uncertain when LASEK was compared with PRK (postoperative mean spherical equivalent and proportion with refraction within ± 0.5 diopter (D)); however, confidence intervals for all time points suggest that if a difference does exist, it is likely to be small and clinically unimportant.

As for safety outcomes, only one trial reported the proportion that lost one or more lines of best spectacle‐corrected visual acuity (BSCVA) post treatment (Ghanem 2008). As a result of the small number of events (one of 102 eyes), the effect of LASEK versus PRK is uncertain. Four of five trials found that the difference in postoperative epithelial healing time was within one day for LASEK versus PRK; the fifth trial reporting this outcome found that epithelial healing time may be up to one day shorter in the LASEK group than in the PRK group (Autrata 2003). With respect to pain scores, four trials found little to no difference between the two procedures; one trial reported lower pain scores in the LASEK group than in the PRK group up to three days post treatment. Data on adverse events such as corneal haze, glare, and halo were sparsely reported, and available data were not adequately powered to detect treatment differences.

Overall, available data are not satisfactory to allow conclusions about which procedure is better than the other.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Ten of the 11 included trials reported no missing outcome data; one trial reported loss to follow‐up for 23.8% of participants (Hashemi 2004a). Except for Ghanem 2008, which compared butterfly LASEK versus PRK, all other trials compared LASEK and PRK in each group. All trials included in this review enrolled participants with low to moderate myopia. It is unclear whether these results can be applied to people with high myopia. As new surface ablation methods to treat high‐order aberrations come into practice, such as wavefront‐guided or wavefront‐optimized refractive surgery (Ambrosio 2003; Claringbold 2002; Rouweyha 2002), conventional PRK and LASEK procedures may fall from use. However, future application of new wavefront technology on surface ablation could benefit from a better understanding of the interaction between epithelium and ablated stroma and clinical (visual acuity and refraction) and patient‐important outcomes (pain scores and adverse outcomes).

Quality of the evidence

In general, we graded the quality of the evidence from very low to moderate. Although trials had mostly unclear risk of bias, we downgraded for imprecision (wide confidence intervals or confidence intervals that did not rule out a small effect), inconsistency, and potential reporting bias (few trials reporting an outcome that was expected to have been assessed). Although we included 11 trials, no meta‐analysis included eight or more trials, and most analyses included less than half of included trials. As data were insufficient, we were not able to perform subgroup analysis and sensitivity analysis, as described in our protocol.

None of the trials used the correct analysis for a paired‐eye design. Because most participants included in this review had both eyes included, the correct paired (matched) analysis would have adjusted for the intra‐person correlation and used the participant, rather than eyes, as the unit of analysis. By not using the appropriate unit of analysis, the precision of the estimates and, therefore, the confidence intervals may not reflect accurately what they should be if a paired analysis had been done.

Potential biases in the review process

We followed standard Cochrane procedures to minimize bias in the review process. All trials used a paired‐eye design; however, none implemented the correct analysis for this design. Therefore, we analyzed data as reported using eyes as the unit of analysis. Analyzing eyes rather than individuals may affect the precision and confidence intervals of estimates.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

This review showed that comparative effectiveness of LASEK versus PRK in treating low to moderate myopic eyes is uncertain, which was consistent with the findings of other reviews (Cui 2008; Zhao 2010). As for eyes with high myopia, Ghadhfan 2007 reported that transepithelial PRK (T‐PRK) was more likely to achieve a higher percentage of eyes with UCVA of 20/30 or better than LASEK, and a slightly higher percentage of UCVA of 20/20 or better (64.9% vs 47.8%, respectively). However, at present, we have found no RCT comparing LASEK versus PRK in eyes with high myopia.

One factor that is involved in the mechanism of corneal haze, and possibly wound healing, is elevated transforming growth factor (TGF)‐β1 level after the operation. Lee 2001 reported that LASEK induced less TGF‐β1 production in tear fluid than PRK. However, no subsequent studies were found to support this finding, and we did not analyze TGF‐β1 levels in this review. Most trials included in this review observed corneal haze scores less than 1.0; this is clinically insignificant and is not thought to affect visual acuity at high contrast, but it may potentially affect low‐contrast vision by increasing high‐order aberrations. Therefore, more studies are needed to clarify the biochemical and histopathological causes of wound healing response and its effects on low‐contrast vision and high‐order aberrations.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Current evidence suggests uncertainty as to differences in efficacy, accuracy, and adverse effects between LASEK and PRK in treatment of eyes with low to moderate myopia. Meta‐analysis for most outcomes was not performed because available data were sparse and results among trials were inconsistent. More evidence is needed to assess whether treatment differences between LASEK and PRK.

Implications for research.

Future trials should follow reporting standards and be rigorously designed and appropriately analyzed. Future trial investigators need to report the trial registry number (given all trials should be registered prospectively), and clearly describe their methods, including how the random sequence was generated, allocation was concealed, whether participants and outcome assessors were masked, declare conflicts of interest, and disclose sources of funding. A protocol containing the listed information should be made available.

Future trials should focus on clinical and patient‐important uncertainties. Future research could be expanded to include other outcomes, such as the mechanism of corneal haze, outcomes at low contrast, and the possibility of applying customized ablation methods. A standardized framework for outcome measures and follow‐up intervals would be beneficial for comparison of outcomes across trials.

Lastly, trials should investigate the comparative effectiveness of LASEK versus PRK in patients with high myopia. The current evidence is limited to participants with low to moderate myopia.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the original review team that started this protocol: Reza Yousefi‐Nooraie, Hassan Hashemi, Hamid Foudazi, Mahammad Miraftab, and Farhad Rezvan.

We acknowledge Iris Gordon, Cochrane Eyes and Vision (CEV) Trials Search Co‐ordinator, for creating and executing electronic searches for this review.

We thank Marie Diener‐West, Colm McAlinden, and George Settas for comments to earlier versions of this review.

We thank Alex Shortt and Gerry Clare, the CEV Contact Editors for this review, for comments provided, and Anupa Shah, Managing Editor for CEV, for assistance provided throughout the review process.

We thank Jennifer Evans and Kristina Lindsley for comments and methodological support provided during the review process.

Appendices

Appendix 1. CENTRAL search strategy

#1 MeSH descriptor Myopia #2 myop* #3 sight* AND (short or near*) #4 (#1 OR #2 OR #3) #5 MeSH descriptor Photorefractive Keratectomy #6 keratectom* #7 PRK #8 (#5 OR #6 OR #7) #9 MeSH descriptor Keratectomy, Subepithelial, Laser‐Assisted #10 laser NEAR/2 assisted subepithelial keratectom* #11 laser subepithelial keratomileusis #12 LASEK #13 (#9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12) #14 (#4 AND #8 AND #13)

Appendix 2. MEDLINE (Ovid) search strategy

1. randomized controlled trial.pt. 2. (randomized or randomised).ab,ti. 3. placebo.ab,ti. 4. dt.fs. 5. randomly.ab,ti. 6. trial.ab,ti. 7. groups.ab,ti. 8. or/1‐7 9. exp animals/ 10. exp humans/ 11. 9 not (9 and 10) 12. 8 not 11 13. exp myopia/ 14. myop$.tw. 15. ((short or near) adj3 sight$).tw. 16. or/13‐15 17. exp photorefractive keratectomy/ 18. keratectom$.tw. 19. PRK.tw. 20. or/17‐19 21. exp keratectomy,subepithelial,laser assisted/ 22. (laser adj2 assisted subepithelial keratectom$).tw. 23. laser subepithelial keratomileusis.tw. 24. LASEK.tw. 25. or/21‐24 26. 20 and 25 27. 16 and 26 28. 12 and 27

The search filter for trials at the beginning of the MEDLINE strategy is from the published paper by Glanville (Glanville 2006).

Appendix 3. EMBASE (Ovid) search strategy

1. exp randomized controlled trial/ 2. exp randomization/ 3. exp double blind procedure/ 4. exp single blind procedure/ 5. random$.tw. 6. or/1‐5 7. (animal or animal experiment).sh. 8. human.sh. 9. 7 and 8 10. 7 not 9 11. 6 not 10 12. exp clinical trial/ 13. (clin$ adj3 trial$).tw. 14. ((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj3 (blind$ or mask$)).tw. 15. exp placebo/ 16. placebo$.tw. 17. random$.tw. 18. exp experimental design/ 19. exp crossover procedure/ 20. exp control group/ 21. exp latin square design/ 22. or/12‐21 23. 22 not 10 24. 23 not 11 25. exp comparative study/ 26. exp evaluation/ 27. exp prospective study/ 28. (control$ or prospectiv$ or volunteer$).tw. 29. or/25‐28 30. 29 not 10 31. 30 not (11 or 23) 32. 11 or 24 or 31 33. exp myopia/ 34. exp high myopia/ 35. exp degenerative myopia/ 36. myop$.tw. 37. ((short or near) adj3 sight$).tw. 38. or/33‐35 39. exp photorefractive keratectomy/ 40. keratectom$.tw. 41. PRK.tw. 42. or/39‐41 43. keratomileusis/ 44. (laser adj2 assisted subepithelial keratectom$).tw. 45. laser subepithelial keratomileusis.tw. 46. LASEK.tw. 47. or/43‐45 48. 42 and 47 49. 38 and 48 50. 32 and 49

Appendix 4. LILACS search strategy

keratectom$ or PRK and keratomileusis or LASEK and myopia

Appendix 5. ISRCTN search strategy

PRK and LASEK

Appendix 6. ClinicalTrials.gov search strategy

PRK AND LASEK

Appendix 7. ICTRP search strategy

PRK AND LASEK

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. LASEK versus PRK.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Proportion of eyes within ± 0.50 D of target refraction at 12 months post treatment | 2 | 152 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.84, 1.03] |

| 2 Postoperative mean spherical equivalent (D) at 1 week | 2 | 154 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.06 [‐0.07, 0.18] |

| 3 Postoperative mean spherical equivalent (D) at 1 month | 7 | 672 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.10 [‐0.05, 0.25] |

| 4 Postoperative mean spherical equivalent (D) at 3 months | 7 | 652 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.07 [‐0.03, 0.17] |

| 5 Postoperative mean spherical equivalent (D) at 6 months | 3 | 378 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.02 [‐0.10, 0.15] |

| 6 Postoperative mean spherical equivalent (D) at 12 months | 3 | 386 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.06 [‐0.02, 0.14] |

| 7 Proportion of eyes with uncorrected visual acuity (UCVA) of 20/20 or better at 1 week | 4 | 244 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.29 [0.92, 1.81] |

| 8 Proportion of eyes with uncorrected visual acuity (UCVA) of 20/20 or better at 1 month | 5 | 336 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.84, 1.08] |

| 9 Proportion of eyes with uncorrected visual acuity (UCVA) of 20/20 or better at 3 months | 4 | 266 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.94, 1.06] |

| 10 Proportion of eyes within ± 0.50 D of target refraction at 1 month | 2 | 140 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.77, 1.19] |

| 11 Proportion of eyes within ± 0.50 D of target refraction at 3 months | 2 | 120 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.04 [0.89, 1.22] |

| 12 Postoperative epithelial healing time (days) at 1 week | 6 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 13 Postoperative pain scores at 1 day | 5 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 14 Postoperative pain scores at 2 days | 4 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 15 Postoperative pain scores at 3 days | 3 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 16 Postoperative corneal haze score at 1 month | 5 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 17 Postoperative corneal haze score at 3 months | 4 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 18 Postoperative corneal haze score at 6 months | 4 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 19 Postoperative corneal haze score at 12 months | 3 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Autrata 2003.

| Methods |

Study design: paired‐eye randomized controlled trial Number randomly assigned: 200 eyes of 100 participants Exclusions after randomization: 16 eyes of 8 participants Number analyzed: 184 eyes of 92 participants Unit of analysis: eye Losses to follow‐up: none Handling of missing data: eyes with missing data excluded from analysis Power calculation: not reported Study design issues: correct paired (matched) analysis not reported |

|

| Participants |

Country: Czech Republic Overall mean age (SD): 27.4 years; SD not reported Age range: 18 to 39 years Gender: not reported Inclusion criteria: age ≥ 18 years; spherical equivalent of 4.65 diopters (D) (range 1.75 to 7.50 D); best spectacle‐corrected visual acuity (BSCVA) of 20/40 or better in all eyes; stable refractions for ≥ 12 months; discontinued use of soft contact lenses for ≥ 14 days before the examination Exclusion criteria: participants with diabetes mellitus, connective tissue disease, corneal disease, cataract, glaucoma, and retinal disease Preoperative mean spherical equivalent: ‐4.90 D in LASEK group and ‐4.78 D in PRK group |

|

| Interventions |

Intervention 1: LASEK Intervention 2: PRK Laser: Nidek EC‐5000 excimer laser Length of follow‐up: Planned: not reported Actual: 24 months |

|

| Outcomes | Primary and secondary outcomes were not distinguished Outcomes reported: refraction; uncorrected visual acuity and best spectacle‐corrected visual acuity; spherical equivalent; epithelial healing time; corneal haze scores; pain score; adverse events Intervals at which outcomes assessed: 1 week and 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 months; except pain score (4‐point scale) at 1, 2, and 3 days |

|

| Notes |

Trial registration: not reported Funding sources: University Hospital Brno, Brno, Czech Republic Disclosures of interest: "neither author has a financial or proprietary interest in any product mentioned" Study period: April 1999 to February 2000 Subgroup analyses: none reported We did not contact trial investigators |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "The first eye treated and the surgical method in the first eye were randomized." However, no detailed information on randomization was provided |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Full text did not provide detailed information on how treatments were allocated to participants. Participants received both treatments; therefore, selection into the study was not affected by knowledge of which eye was going to get which treatment, as both treatments were included |

| Masking of participants and personel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Participants signed an approval that they would not know the technique assigned for them in each eye. Masking of study personnel was not reported |

| Masking of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | Reasons for exclusion were associated with the treatment group; "Eight of 100 LASEK eyes (8%) [were] converted to PRK because the epithelial flap disintegrated and [were] excluded for the comparative study" |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No clinical trial registration reported and the protocol was not available for comparison |

| Other bias | Low risk | "Neither author has a financial or proprietary interest in any product mentioned" |

Eliacik 2015.

| Methods |

Study design: paired‐eye randomized controlled trial Number randomly assigned: 56 eyes of 28 participants Exclusions after randomization: none Number analyzed: 56 eyes of 28 patients Unit of analysis: eye Losses to follow‐up: none Handling of missing data: no missing data Power calculation: not reported Study design issues: correct paired (matched) analysis not reported |

|

| Participants |

Country: Turkey Overall mean age (SD): 26.39 (4.99) years Age range: 18 to 34 years Gender (%): 16 men (57.1%) and 12 women (42.9%) Inclusion criteria: "at least 18 years old, and had spherical equivalent manifest refraction between ‐1.00 and ‐5.00 diopters (D), and astigmatism less than ‐2.00 D, stable refraction at least 12 months before surgery, and a minimum follow‐up of 3 months. No one had signs of keratoconus, uncontrolled glaucoma, untreated retinal abnormalities, or previous intraocular or corneal surgery" Exclusion criteria: "older than 40 years, diabetes, and history of herpetic keratitis, and previous intraocular or corneal surgery, pregnancy, nursing, collagen vascular diseases, or dry eye" Preoperative mean spherical equivalent: ‐2.59 D in LASEK group and ‐2.64 D in PRK group |

|

| Interventions |

Intervention 1: LASEK Intervention 2: PRK Laser: VISX Star S4 excimer laser Length of follow‐up: Planned: not reported Actual: 3 months |

|

| Outcomes | Primary and secondary outcomes were not distinguished Outcomes reported: epithelial healing time, haze, discomfort score, refraction, UVCA, BSCVA Intervals at which outcomes assessed: 1, 2 3, 4, 5, and 10 days, 1 and 3 months |

|

| Notes |

Trial registration: not reported Funding sources: "the work was not supported or funded by any drug company" Disclosures of interest: "authors have no conflicts of interest" Study period: March 2014 and May 2014 Subgroup analyses: none reported We did not contact trial investigators |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | It was not clearly described how the random sequence was generated. "This was a prospective, randomized, single‐center study." "Contralateral eyes in each patient were subject to random allocation through which PRK surgery was carried out on one eye, and LASEK was carried out for the other eye of same patient by the same surgeon" |